Chapter 8: The Allies Close In

Just as the Allies prepared to close on Buna the turning point came in the struggle for the southern Solomons. In the naval battle of Guadalcanal (12–15 November), Admiral Halsey’s forces virtually wiped out an eleven-ship enemy convoy, carrying almost all the reserves the Japanese had available for action in the South and Southwest Pacific. After this catastrophic setback, the Japanese gave up trying to reinforce their troops on Guadalcanal, contenting themselves with desperate attempts to keep them supplied so as to prolong resistance as long as possible. With the island sealed off, Marine Corps troops, reinforced by Army troops (who were arriving on the scene in increasing numbers to replace the marines), could proceed uninterruptedly with the task of destroying the large Japanese garrison left on the island.1 The battle for Guadalcanal had entered an advanced phase just as that for Buna began.

Mounting the Attack

The Scene of Operations

The scene of operations was the Buna–Gona coastal plain, commonly referred to as the Buna area. (Map V) Lying between the sea and the foothills of the Owen Stanley Range, the region is quite flat. In the Buna strips area the elevation is about three feet. At Soputa, some six and one-half miles inland, it is only a few feet higher. The terrain consisted mainly of jungle and swamp. The jungles, mostly inland, were a tangle of trees, vines, and creepers, and dense, almost impenetrable undergrowth. The swamps, filled with a frenzied growth of mangrove, nipa, and sago trees, were often shoulder-deep, and sometimes over a man’s head.

Scattered through the region were groves of coconut palms, areas of bush and scrub, and patches of kunai grass. The coconut palms, some of them 125 feet high, were to be found principally along the coast at such points as Cape Endaiadere, Buna Mission, Giruwa, Cape Killerton, and Gona, but there were also a few groves inland, surrounded in the main by swamp. Generally the bush and scrub were heavily overgrown, and the undergrowth was almost as impenetrable as that in the jungle. The kunai grass, shoulder-high, and with knife-sharp edges, grew in thick clumps, varying in size from small patches that covered a few square feet to the Dobodura grass plains that extended over an area several miles square.

The rainy season had begun and the Girua River, which divided the area in two,

was in flood. After losing itself in a broad swampy delta stretching from Sanananda Point to Buna Village, the Girua emptied into the sea through several channels. One of these, Entrance Creek, opened into the lagoon between Buna Village and Buna Mission. Between Entrance Creek and Simemi Creek to the east was an immense swamp. This swamp, formed when the overflow from the river had backed up into the low-lying ground just south of Buna Mission, reached as far inland as Simemi and Ango. It was believed to be impassable, and its effect was to cut the area east of the river in two, making the transfer of troops from one part to the other a slow and difficult process.2

Because of the swamp, there were only three good routes of approach to the Japanese positions east of the river. The first led from Soputa and Ango Corner along the western edge of the swamp to a track junction three quarters of a mile south of Buna Mission which was to become known to the troops as the Triangle. From this junction, one trail led to Buna Village and the other to Buna Mission. A second route of approach was from Dobodura and Simemi along the eastern end of the swamp and along the northern edge of the Old Strip to Buna Mission. A third approach lay along the coastal track from Cape Sudest to Cape Endaiadere, where the trail back-tracked diagonally through Duropa Plantation to the New Strip, and ran thence to Buna Mission.

The situation was the same on the western side of the river. There were only two good approaches to the Japanese beachhead positions in that area, and both of them lay through swamp. One was the trail that ran to Gona via Amboga Crossing and Jumbora; the other was the main trail to Sanananda via Popondetta and Soputa. In addition, several branch trails forked from the Soputa–Sanananda track to Cape Killerton, where they joined the coastal trail to Sanananda, Sanananda Point, and Giruwa.

In the hot and muggy climate of the Buna–Gona area the humidity averages 85 percent, and the daily temperature, 96° F. The area was literally a pesthole. Malaria, dengue fever, scrub typhus, bacillary and amoebic dysentery were endemic there, as were the lesser ills—jungle rot, dhobie itch, athlete’s foot, and ringworm.3 Unless the campaign came to a quick end, disease would inevitably take heavy toll of the troops.

The Plan of Attack

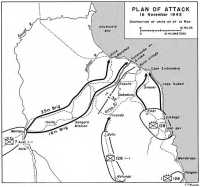

New Guinea Force published the over-all plan of attack on 14 November. The orders provided that the 7th Australian Division and the 32nd U.S. Division would destroy the enemy in the area bounded by the Kumusi River, Cape Sudest, and Holnicote Bay. The boundary between the two divisions was to be a line running from the mouth of the Girua River to Hihonda, thence southwesterly along a stream halfway between Inonda and Popondetta. The 7th Division was to operate on the left of the boundary, the 32nd Division on the right. The 21st Brigade, now to serve its second

Map 7: Plan of Attack, 16 November 1942

tour of duty in the campaign, was to be flown in from Port Moresby and go into 7th Division reserve near Wairopi. (Map 7)

The troops were to begin moving forward on 16 November, the 32nd Division against Buna, and the 7th Division against Gona and Sanananda. Units on either side of the interdivisional boundary were to take particular care not to uncover their inward flank. Each division was to be prepared to strike across the boundary against the enemy’s flank or rear should the opportunity offer. The 32nd Division, in addition to carrying on its combat role, was to establish a landing strip at Dobodura, secure and hold the crossing of the Girua River near Soputa, and provide for the security of the right flank from enemy sea-borne attack.4

The LILLIPUT Plan

Hopeful of an early victory, New Guinea Force issued a plan for defense of the Buna area the next day. Under LILLIPUT (as the plan was called) the 32nd Division would become responsible for Buna’s defense as soon as the area was cleared of the enemy. To assist the division in the discharge of that responsibility, Australian artillery, antiaircraft, and air-warning units were to be sent forward to Buna at the earliest possible moment and come under its command. The first echelon of LILLIPUT, including several K.P.M. ships, had already been called forward and was due to arrive at Milne Bay from Australia on 18 November.5

General Blamey had asked General MacArthur for a few destroyers to protect the LILLIPUT ships as they passed through the area beyond Cape Nelson and while they were unloading at Buna, but Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender, who had succeeded Admiral Leary as Commander of the Allied Naval Forces in September, had voiced strong objections to sending destroyers into the “treacherous” waters off Buna. In a letter to General MacArthur, he made his position clear. The entire area between Cape Nelson and Buna, he wrote, was so filled with reefs that there was virtually no “sea room” in which destroyers could maneuver. The Japanese, using the northern approach route from Gasmata, a small island off the south coast of New Britain, did not have this difficulty, for there were deep-water areas suitable for the maneuvering of cruisers and destroyers all the way between it and Buna. To put a “minor surface force” in the Buna area would serve no useful purpose in the face of the much heavier forces the enemy could easily send in from Rabaul. General Blamey could have one or two shallow-draft antisubmarine vessels for the escort of the LILLIPUT ships, but no destroyers; the latter were not to be used for escort duty north of Milne Bay.6

Since Admiral Carpender had objections also to sending submarines into the Buna area,7 it became clear that the only help the Allied forces closing in on Buna could expect from the fleet was a few small patrol boats. The air force, in addition to bearing its close support and supply responsibilities, would have to carry almost the entire burden of protecting Allied supply movements northward of Milne Bay, and of beating back enemy attempts to reinforce the beachhead.

The Forces Move Up

On 15 November General Harding issued the divisional plan of attack. In Field Order Number One of that date, he ordered one battalion of the 128th Infantry to march along the coast via Embogo and Cape Sudest to take Cape Endaiadere. A second battalion was to move on the Buna airfield via Simemi. The remaining battalion, which would be in division reserve, was to proceed to the Dobodura grass plains area and

Simemi Village, along the route of Company M, 128th Infantry, on its way to an advanced position

prepare a landing strip for transports. Each battalion was to have an engineer platoon and a body of native carriers attached. H Hour for Warren Force was set at 0600, 16 November. The 126th Infantry (less the elements of the 1st Battalion arriving at Pongani) would close on Inonda. It would move from Inonda on Buna by a route to be specified later.8

While Colonel Tomlinson’s force would have to be supplied by airdropping until the field at Dobodura was in operation, Warren Task Force was, as far as possible, to be supplied by sea. There was to be a deep-water harbor at Oro Bay. Col. John J. Carew, the Divisional Engineer, having investigated the harbor area and reported favorably on the project.9 Its completion, and the completion ultimately of an access road from it to Dobodura, would make it

Lt. Col. Herbert A. Smith leading troops across a river on the way to Embogo

possible for large ships to anchor there and would also make possible the development of Dobodura into a major air base, not only for fighters and transports, but also for all types of bombers.

General MacNider’s troops were given an extra ration of rice before they left their lines of departure on 16 November. Colonel Tomlinson’s headquarters, the 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry, and Major Boerem’s detachment (which according to plan was to be reunited with the rest of the 1st Battalion at Dobodura as soon as possible) pushed off from Natunga to Bofu. The 2nd Battalion, already at Bofu, began moving on Inonda.10

Early on 16 November, just as the Americans marched out to the attack, the Australians completed the crossing of the Kumusi River. Leaving an engineer detachment to clear an airstrip on the east bank of the river, the 25th Brigade began marching on Gona, and the 16th Brigade, on

General MacNider (center, facing forward) mapping plans to take Buna

Sanananda. Advance Headquarters, 7th Division, crossed the river on the 16th just behind the 16th Brigade, and Captain Medendorp, whose Wairopi Patrol had had a light brush with the enemy at Asisi a few miles south of Wairopi a week before, reported to General Vasey the same day.11

The attack was on, but the condition of many of the attacking troops left a great deal to be desired. The 16th and 25th Brigades, which had chased the enemy nearly all the way across the Owen Stanleys, had been in continuous action under the most arduous conditions for almost two months. They had lost many men, and those that remained were very tired. The 21st Brigade, General Vasey’s reserve, though rested and regrouped, was far below strength.12 Only the untried Americans, numbering at the

time just under 7,000 men,13 could be considered fresh troops, and many of them because of sickness and exhausting marches were far from their physical peak.

The 32nd Division on the Eve of Combat

Training and Equipment

Troops in the opening engagements of every war are often found to be ill prepared to wage the kind of war they actually have to fight. This was the case with the 32nd Division when its leading elements marched out to meet the enemy in mid-November 1942. Not only were the troops inadequately trained, equipped, and supported for the task in hand, but many of the difficulties they were to meet at Buna had been neither foreseen nor provided for.

The division, whose insignia is a Red Arrow with a crosspiece on the shaft, was a former Michigan and Wisconsin National Guard unit. It had a record of outstanding service in World War I, having fought with great distinction on the Aisne-Marne, the Oise-Aisne, and in the Meuse-Argonne drive. The division was inducted into the federal service on 15 October 1940 as a square division. The following April some 8,000 Michigan and Wisconsin selectees were added to its strength. After participating in the Louisiana maneuvers, the division was triangularized into the 126th, 127th, and 128th Infantry Regiments. The 120th, 121st, 126th, and 129th Field Artillery Battalions were assigned as divisional artillery. The 121st Field Artillery Battalion was equipped with 155-mm. howitzers. The other battalions, which had trained with World War I 75’s, received 105’s just before embarkation.14

The 32nd Division had expected to fight in the European theater and, in late December 1941, had actually been earmarked for operations there. General Harding joined it in Louisiana in early February 1942. In late February the division was sent to Fort Devens, Massachusetts, and instructed to prepare for immediate movement to Northern Ireland. Ordered at the last moment to the Pacific, the division took on more than 3,000 replacements at San Francisco and reached Adelaide, Australia, on 14 May. Training had scarcely got under way when the division was again ordered to move—this time to Brisbane. The move was completed in mid-August, and training had just got into its stride again at Camp Cable, the division’s camp near Brisbane, when the first troops started moving to New Guinea.

These moves served the division ill. Not only was it difficult to harden the men because they were so much in transit, but the weeks spent in moving, in making each successive camp livable, and in providing it with bayonet courses, rifle range, infiltration courses, and similar installations before infantry training could begin cut heavily into the division’s training time. This was a serious matter since the division had arrived in Australia only partially trained, and many

of its officers, new to the division, had not yet had time to know their men.

There was another difficulty. Like the 41st Division, the 32nd was part of the garrison of Australia. The main emphasis in its training had been on the defense of Australia, a type of training from which the troops had little new to learn for it repeated the training that they had received at home. What they really needed—training in jungle combat—they got very little of.15

General Richardson, Commanding General, VII Corps, then on a mission in the Pacific for General Marshall, inspected the troops in early July and reported that as far as their training was concerned they were “still in the elementary stages” and would not be ready for combat “by some few months.” General Eichelberger reached Australia in early September and found the division still not ready for combat. He rated its state of training as “barely satisfactory” and told General MacArthur it needed further hardening as well as a vast amount of training, especially in jungle warfare.16

As quickly as he could, Eichelberger instituted a stepped-up training and hardening program, but the 126th and 128th Infantry Regiments had already moved out to New Guinea before the new program could go into effect. Thus when the two regiments entered combat they were not in top physical condition, had received very little training in scouting, night patrolling, or jungle warfare, and had been fired over in their training either very briefly or not at all.17

Looking back at it all, General Harding had this to say of the training of the division before it entered combat:

I have no quarrel with the general thesis that the 32nd was by no means adequately trained for combat—particularly jungle combat. A Third Army (Krueger) training inspection team gave it a thoroughgoing inspection about a month before I joined it and found it deficient on many counts. I got a copy of this report from Krueger and it was plenty bad. ...

On the other hand I found the division well disciplined, well behaved, and well-grounded in certain elements of training. ... My estimate of training when I took over is that it was about on a par with other National Guard divisions at that time.

Unfortunately we had no opportunity to work through a systematic program for correcting deficiencies. From February when I took over until November when we went into battle we were always getting ready to move, on the move, or getting settled after a move. No sooner would we get a systematic training program started than orders for a move came along to interrupt it. As you know, you just can’t formulate and get set up for a realistic training program in a couple of days. As a matter of fact, realistic training for modern war requires an enormously elaborate installation of training aids, courses, etc. without which really good training can’t be complete. Such installations were out of the question

for us, although we managed to set up a few simplified modifications of the real thing which would have served fairly well, had we ever had time to run more than a fraction of the command through them.18

Although the troops had much of the standard equipment of the day, not all of it was to prove suitable for the area in which they were to fight. Much of their radio equipment, for instance, had already failed to function, and they did not have the carbine which would have been an ideal weapon in the tangled, overgrown beachhead area. Although the carbine was available elsewhere, it was to be months before the first carbines reached the Southwest Pacific Area and were distributed among the troops.19

The troops had none of the specialized clothing and equipment which later became routine for jungle operations. Their clothing—dyed to aid concealment in the jungle—was already causing them great discomfort. Not only did the dye run, but its residuum stopped up the cloth and made it nonporous. The garments, as a result, became unbearable in the extreme tropical heat and caused hideous jungle ulcers to appear on the bodies of nearly all the troops wearing them.20

Though they were about to enter a jungle area overgrown with vines and creepers and teeming with noxious insects, the men were critically short of machetes, and had no insect repellants. Nor had anyone thought to issue them small waterproof boxes or pouches for the protection of their personal effects and medical supplies from the extreme heat and wet. Cigarettes and matches became sodden and unusable, and quinine pills, vitamin pills, and salt tablets,—then usually issued in bulk a few days’ supply at a time—began to disintegrate almost as soon as the men put them in their pockets or packs, and the same thing sometimes happened to the water chlorination tablets.21

Various expedients had been adopted to lighten the weight each man would have to carry in the jungle. The marching troops were equipped as far as possible with Thompson submachine guns, and the heavier weapons, including most of the 81-mm. mortars, were put aside to be sent forward later by boat. Medical and communications equipment were stripped to the bare essentials, and field ranges and accompanying heavy mess equipment were left behind at Port Moresby.22

The medical units were using gas stoves, kerosene burners, and even canned heat to sterilize their instruments and provide the casualties with hot food and drink, but the front-line troops had none of these things. Without their normal mess equipment, they no choice but to use tin containers of all kinds to heat up their rations, prepare their coffee (when they had coffee), and wash their mess gear. Since it rained almost continually and there was very little dry fuel available, it was usually impossible to heat

water sufficiently to sterilize the tins and mess gear from which the troops ate—an open invitation to the same type of diarrhea and dysentery that had already overtaken the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, in its march over the mountains.23

Artillery and Engineer Support

As the troops marched out for the attack, there was a widespread belief at higher headquarters that the mortars, direct air support, and the few Australian pieces already available in the area would be enough to clear the way for the infantry.24 Even this represented better support than that advocated by General Kenney, who, in a letter to Lt. Gen. H. H. Arnold on 24 October, told the latter that neither tanks nor heavy artillery had any place in jungle warfare. “The artillery in this theater,” he added, “flies.”25

Neither General Harding nor his artillery commander, Brig. Gen. Albert W. Waldron, believed that the infantry could get along very well without the artillery. Strongly supported by Harding, Waldron kept asking that the divisional artillery be brought forward. General MacArthur’s headquarters did not have the means either to bring all the artillery forward or to keep it supplied when it got there. Not being at all sure that artillery could be used effectively or even be manhandled in the swampy terrain of the beachhead, GHQ was cool to the proposal.

In the end, by dint of great persistence, and with the help of the Australian artillery commander, Brig. L. E. S. Barker, who thought as he did on the subject, Waldron got a few pieces of artillery—not his own, and not as much as he would have liked, but better than no artillery at all.26

If the division’s artillery support—two 3.7-inch howitzers and the promise of a four-gun section of 25-pounders which had yet to arrive at the front—was scanty, its engineer support was even scantier. Almost half of General Horii’s original force had either been combat engineers or Army and Navy construction troops. Yet, General Harding, with the rainy season at hand, and every possibility that roads, bridges, and airfields would have to be built in the combat zone, had only a few platoons of the 114th Engineer Battalion attached to his two combat teams. And these engineer troops reached the front almost empty handed. They had no axes, shovels, or picks, no assault boats, very little rope, and not a single piece of block and tackle. The theory was that all these things would come up by boat with the heavy equipment. In practice, however, the failure to have their tools accompany them meant that the engineer troops could do only the simplest pioneer work at a time when their very highest skills were needed.27

The Condition of the Troops

Medical supplies at the front were critically short as the troops marched out for the attack. Bismuth preparations for the treatment of gastrointestinal disturbances were almost unprocurable, and there was not

107th Medical Battalion corpsmen at Ward’s Drome near Port Moresby awaiting a flight to Pongani

enough quinine sulphate, the malaria suppressive in use at the time, for regular distribution to the troops. There was no atabrine, and none was to be received throughout the campaign.28

General Harding had arranged to have his medical supplies go forward by boat, only to find at the last minute that the boats were busy carrying other things. He did what he could in the emergency. Getting in touch immediately with General Whitehead, Harding explained to him that the medical supply situation was “snafu” and asked him to fly in the most urgently needed items “to take care of things until we can get the boat supply inaugurated.”29

Most of the troops had gone hungry; some had nearly starved during the approach march, and food was still in short supply. Rations had accumulated in the rearward dumps between Wanigela and the front, but there was only a few days’ supply at the front itself. It was assumed that this

deficiency and other supply shortages would be made good as the attack progressed.30

Except for the latest arrivals (the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 126th Infantry) the troops presented anything but a soldierly appearance. Their uniforms were stained and tattered, few had underwear or socks, and their shoes in most cases were either worn out or in the process of disintegration. Most were bearded and unkempt, virtually all were hungry, and some were already showing unmistakable signs of sickness and exhaustion.31

The 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, and the troops who had marched with it across the mountains had been severely affected by the ordeal. The 128th Infantry, whose name for Pongani was “Fever Ridge,” was not in much better condition. As the commander of the 2nd Battalion recalls the matter, the trouble was that the men had been on short rations since mid-October; that they had made some extremely exhausting marches through the jungle “on a diet of one-third of a C-ration and a couple of spoonfuls of rice a day”; and that many of them already had “fever, dysentery, and jungle rot.”32 General Eichelberger put the whole matter in a sentence when he wrote that, even before the 32nd Division had its baptism of fire, the troops were covered with jungle ulcers and “riddled with malaria, dengue fever, and tropical dysentery.”33 Sickness and exhaustion had already claimed many victims; they would claim many more as the fighting progressed.

The Division’s Estimate of Enemy Strength

For all their hunger, their exhaustion, and their sickness, the troops were cocky and overconfident about the task that lay ahead. They had been told and they believed that Buna was a “push over,” and neither they nor their commanders saw any reason why it should not be theirs in a few days. No one—either at Port Moresby or at the front—believed that there would be any difficulty in taking Buna. Natives (who as was soon to become evident had no conception of numbers) had spied out the land and come back with reports that there were very few Japanese in the area. The air corps, similarly, had been reporting for more than a month that there were no Japanese to be seen at the beachhead and that there was no evidence that it was fortified or that the enemy had serious intentions of defending it.34

As these reports of enemy weakness poured in, the 32nd Division began to think in terms of a quick and easy conquest of Buna. “I think it is quite possible,” wrote General Harding on 14 October, “that the Japanese may have pulled out some of their Buna forces. ...” “We might find [Buna] easy pickings,” he added, “with only a shell of sacrifice troops left behind to defend it.” By 20 October General Harding felt that there was “a fair chance that we will have

Buna by the first of November.” At the end of the month, he wrote that all information to date was to the effect that Japanese forces in the Buna–Gona area were relatively light and asked how GHQ would look upon November 5 as a suitable date for D Day. “Things look pretty favorable right now,” he said, “for a quick conquest of Buna.”35

A Ground Forces observer, Col. H. F. Handy, noted that, as November opened, many in the 32nd Division felt “that Buna could be had by walking in and taking over.”36 Another Ground Forces observer, Col. Harry Knight, noted that “the lid really blew off, when the order was received on 3 November that American troops were not to move forward from Mendaropu and Bofu until further instructed. The reason for the order was, of course, to gain time in which to stockpile supplies for the impending advance, but the division, restive and eager to be “up and at ‘em” did not see it that way.

... Opinions were freely expressed by officers of all ranks ... [Colonel Knight recalls] that the only reason for the order was a political one. GHQ was afraid to turn the Americans loose and let them capture Buna because it would be a blow to the prestige of the Australians who had fought the long hard battle all through the Owen Stanley Mountains, and who therefore should be the ones to capture Buna. The belief was prevalent that the Japanese had no intention of holding Buna; that he had no troops there; that he was delaying the Australians with a small force so as to evacuate as many as possible; that he no longer wanted the airfield there; ... that no Zeros had been seen in that area for a month; and that the Air Corps had prevented any reinforcements from coming in ... and could prevent any future landing . ...37

On 6 November Maj. W. D. Hawkins, General Harding’s G-2, noted that both ground and air reconnaissance reports indicated that Buna, Simemi, and Sanananda each held perhaps 200–300 Japanese with only “a small number” of enemy troops at Gona. He went on to guess that the enemy was already reconciled to the loss of Buna and probably intended to evacuate it entirely. Major Hawkins thought the Japanese would be most likely to try evacuating their forces by way of the Mambare River so as to be able to take them off at the river’s mouth. They would do this, he suggested, in order to avoid a “Dunkirk” at Buna, since Buna was an open beach from which embarkation by boats and barges would lay the evacuees open to heavy air attack.38

These optimistic views on the possibilities of an early Japanese withdrawal did not agree with General Willoughby’s estimates of the situation. Willoughby estimated enemy strength on 10 November as two depleted regiments, a battalion of mountain artillery, and “normal” reinforcing and service elements—about 4,000 men in all. He thought that an enemy withdrawal from Buna was improbable, at least until the issue was decided at Guadalcanal. It was known, he said, that General Horii’s orders were definitely to hold Buna until operations in the Solomons were successfully completed. These orders, the Japanese hope of success in the Solomons, and what was known of the character and mentality of the Japanese commanders involved made it highly unlikely, General Willoughby thought, that there would be “a withdrawal at this time.”

By 14 November General Willoughby began to have doubts that the enemy had two regiments at Buna. He thought that the

mauling taken by the Japanese at Oivi and Gorari had left them with about “one depleted regiment and auxiliary units” and that these, pending the outcome of the Solomons operation, were capable only of fighting a delaying action. It was therefore likely, General Willoughby suggested, that there would be close perimeter defense of the airfield and beachhead at Buna, followed by a general withdrawal, if the Japanese effort in the Solomons failed. That the enemy would attempt further reinforcement of the Buna area he thought improbable “in view of the conditions in the Solomons, and the logistic difficulties and risks which are involved.”39

General Vasey’s estimate of the enemy’s strength based on prisoner of war interrogations was, as of 14 November, 1,500 to 2,000 men40—roughly the same figure that General Willoughby seems to have had in mind in his revised estimate of the same day. General Harding, who had Vasey’s estimate, but had probably had no chance as yet to see Willoughby’s, was more optimistic than either. Relying principally on information supplied by the natives, his G-2 had estimated that the “Buna area was garrisoned by not more than a battalion with purely defensive intentions.”41 Harding accepted this estimate, and the intelligence annex in his first field order of the campaign read as follows:

The original enemy force based at Buna is estimated as one combat team with two extra infantry battalions attached. This force has been withdrawing steadily along the Kokoda Trail for the past six weeks. Heavy losses and evacuation of the sick have reduced them to an estimated three battalions, two of which made a stand in the Kokoda-Wairopi area, with the third occupying Buna and guarding the line of communications. Casualties in the two battalions in the Wairopi area have reduced them to approximately 350 men, who, it is believed, are retiring northward along the Kumusi River Valley. ...42

By the time the story got to the men it was to the effect that there were not over two squads of Japanese in Buna Village and that other enemy positions were probably as weakly held. Told by their officers that the operation would be an easy one, and that only a small and pitiful remnant of the enemy force which had fought in the Owen Stanleys remained to be dealt with, the troops were sure that they could take Buna in a couple of days, and that about all that remained to be done there was to mop up.43

This was a sad miscalculation. The Japanese were present in much greater strength than the 32nd Division supposed, and superbly prepared defensive positions stood in its way, as well as in the way of the 7th Division which was to attack farther to the west.

The Enemy Position

The Japanese Line

The Japanese had established a series of strong defensive positions along an eleven mile front extending from Gona on their

extreme right to Cape Endaiadere on their extreme left. The enemy line enclosed a relatively narrow strip along the foreshore. It varied from a few hundred yards to a few miles in depth and covered an area of about sixteen square miles. (Map VI)

The Japanese defense was built around three main positions. One was at Gona, another was along the Sanananda track, and the third was in the Buna area from Girua River to Cape Endaiadere. Each was an independent position, but their inward flanks were well guarded, and lateral communications between them, except where the coastal track had flooded, were good. Gona, a sandy trail junction covering the Army anchorage at Basabua, was well fortified, though its proximity to the sea made impossible defense in any depth. There were strong and well-designed defenses along the Sanananda track and at the junction of the several branch trails leading from it to Cape Killerton. On the other side of the Girua River equally formidable defenses covered the Buna Village, Buna Mission, and Buna Strip areas.

The main Japanese base was at Giruwa. The largest supply dumps and the 67th Line of Communications Hospital were located there. On this front the main Japanese defensive position was about three and one-half miles south of Sanananda Point, where a track to Cape Killerton joined the main track from Soputa to Sanananda Point. A lightly wooded area just forward of the track junction, and the sandy and relatively dry junction itself, bristled with bunkers, blockhouses, trenches, and other defensive positions. Beginning a couple of miles to the south, several forward outposts commanded the trail. About half a mile to the rear of the junction, where another trail branched from the main track to Cape Killerton, there was a second heavily fortified position, and beyond it, a third. These positions were on dry ground—usually the only dry ground in the area. They were flanked by sago swamp, ankle to waist deep, and could be taken only by storm with maximum disadvantage to the attackers.44

East of the Girua River, the Japanese line was even stronger because it presented a continuous front and could not be easily flanked. The line began at the mouth of the Girua River. Continuing southeastward, it cut through a coconut grove and then turned southward to the trail junction where the Soputa-Buna track forks to Buna Village on the one hand and to Buna Mission on the other. Sweeping north, the line enclosed the Triangle, as the fork was called, and then turned eastward from that narrow salient to the grassy area known as the Government Gardens. From the Gardens, it led south and then east through the main swamp to the grassy area at the lower or southern edge of the Old Strip. It looped around the strip and, continuing southward, enclosed the bridge between the strips. Then making a right-angled turn to the New Strip and following the southern edge of the strip to within a few hundred yards of the sea, it cut sharply northeast, emerging on the sea at a point about 750 yards below Cape Endaiadere.45

Because the three-foot water table in the

area ruled out the possibility of deep trenches and dugouts, the region was studded instead with hundreds of coconut log bunkers, most of them mutually supporting and organized in depth. In general, they were of two types: heavily reinforced bunkers located in more or less open terrain, and smaller, less heavily reinforced bunkers built where the terrain was overgrown with trees and vegetation that offered the defenders a measure of protection against air bombardment or artillery fire.

There were a few variations. Now and then where the terrain particularly favored them, the Japanese had large, squat, earth-covered blockhouses, each capable of holding twenty or thirty men. In addition, they had a few concrete and steel pillboxes behind the New Strip.

Except for these variations, which were on the whole rare, the standard Japanese bunker in the area was of heavy coconut log and followed a common pattern. The base was a shallow trench, perhaps two feet deep. It was six to eight feet long and a few feet wide for the smaller bunkers, and up to thirty feet long and ten feet wide for the larger ones. Heavy coconut logs, about a foot thick, were used for both columns and crossbeams. The logs were cut to give the bunkers an interior height of from four to five feet, depending on the foliage and terrain. The crossbeams forming the ceiling were laid laterally to the trench. They usually overlapped the uprights and were covered by several courses of logs, and often by plates of sheet steel up to a quarter of an inch thick. The walls were revetted with steel rails, I-beams, sheet iron, log pilings, and forty-gallon steel oil drums filled with sand.

As soon as the framework was up, the entire structure was covered with earth, rocks, and short chunks of log. Coconuts and strips of grass matting were incorporated into the earth fill to assist in cushioning the pressures set up by high explosive, and the whole structure was planted with fast-growing vegetation. The result could scarcely have been improved upon. The bunkers, which were usually only about seven or eight feet above ground, merged perfectly with their surroundings and afforded excellent concealment.

As a further aid to concealment, firing slits were usually so small as to be nearly invisible from the front. In some cases (as when the bunkers were intended merely as protection from artillery and air bombardment) there were no slits at all. Entrance to the bunkers was from the rear, and sometimes there was more than one entrance. The entrances were placed so that they could be covered by fire from adjacent bunkers, and they were usually angled to protect the occupants from hand grenades. The bunkers either opened directly onto fire trenches or were connected with them by shallow crawl tunnels. This arrangement permitted the Japanese to move quickly from fire trench to bunker and back again without fear of detection by troops only a few yards away.

These formidable field fortifications were cleverly disposed throughout the Buna position. Bunker and trench systems, within the Triangle, in the Government Gardens, along Entrance Creek, and in the Coconut Grove on the other side of the creek, protected the inland approaches to Buna Village and to Buna Mission, and the approaches, in turn, were honeycombed with enemy emplacements. The main swamp protected the southern edge of the Old Strip, and bunkers, fire trenches, and barbed wire covered its northern edge. The

Coconut log bunker with fire trench entrance in the Buna Village area

bridge between the strips had bunkers and gun emplacements both at front and rear, and the bridge area could be swept by fire from both strips. There were bunkers, fire trenches, and breastworks behind the New Strip and in the Duropa Plantation, and fire in defense of the strip could also be laid down from the bridge area, from the Old Strips and from the Y-shaped dispersal bays at its eastern end. The airstrips afforded the Japanese cleared fields of fire and made it possible for them to lay down bands of fire on troops who sought to flank the New Strip by crossing the bridge between the strips, or who tried advancing along its northern edge.46

The Japanese line at Buna was, in its way,

Interior of coconut log bunker reinforced with sand-filled oil drums near Duropa Plantation

a masterpiece. It forced the 32nd Division to attack the enemy where he was strongest—in the Triangle, along the trail leading to the bridge between the strips; along the northern edge of the strip; and frontally in the Duropa Plantation. By canalizing the Allied attack into these narrow, well-defended fronts, the Japanese who had short, interior lines of communication, and could shift troops from front to front by truck and landing craft, were in a position to exploit their available strength to the maximum, no matter what its numerical inferiority to that of the Allies.

The Garrison

Shortly after contact was lost with General Horii, Colonel Yokoyama, commanding officer of the 15th Independent Engineers, took charge of all Japanese forces west of the river. Captain Yasuda, as the senior naval officer present, took command of those east of it.47

On 16 November, the day the Allies marched out for the attack, the Japanese garrison in the beachhead area was a jumble of broken Army and Navy units. Though riddled by battle casualties and disease, it still numbered approximately five and a half thousand effectives.48 Army units included the remnants of the 144th Infantry, of the 15th Independent Engineers, the 3rd Battalion, 41st Infantry, the divisional cavalry detachment, and the 47th Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion. In addition, a few field artillery batteries had been left to guard the beachhead along with a number of rear echelon units that had never been in combat. There were about 500 Yokosuka 5th and Sasebo 5th special naval landing troops in the area, and perhaps twice that number of naval laborers from the 14th and 15th Naval Pioneer Units.49

The Condition of the Enemy Troops

The Japanese were in a bad way. In the long retreat from Ioribaiwa (and especially at Oivi and Gorari) and in the crossing of the Kumusi, they had lost irreplaceable weapons and supplies. Their most critical shortages were in small arms, food, and medical supplies—items that Lt. Col. Yoshinobu Tomita, the detachment supply officer, had for some time been doling out with a careful hand.

All the weapons that could be scraped together were either in the front lines or stacked where they would be readily available when the front-line troops needed them. Except for troops immediately in reserve, most of the men to the rear had no weapons. Worried by the situation, Colonel Yokoyama issued orders for all troops without arms to tie bayonets to poles. If they had no bayonets, they were to carry wooden spears. These “weapons” were to be carried at all times; even the patients in the hospital were to have them at their bedsides.50

The troops had been on short rations for a long time, and the ration was progressively decreased. To eke it out, the few horses that were left were being gradually butchered for food.

There was a great deal of sickness. Nearly all the troops being admitted to the hospital for wounds and disease were found to be suffering as well from exhaustion and general debility. There had been serious outbreaks of malaria in the ranks, and a large proportion of the men had dysentery of an aggravated kind.

Things were at their worst at the base hospital at Giruwa. There was very little medicine, and not enough food to promote

the recovery of the patients. Water had seeped into the wards, and the seepage, the extreme humidity, and heavy rains had caused clothes, bedding, and medical equipment to mold, rot, or rust away. As November opened, the medical staff had reported that food and medicine were so short as “to militate absolutely against the recovery of the patients,” and the situation, instead of improving, had become progressively worse.51 Toward the end of the month, a Japanese soldier was to write in his diary: “The patients in the hospital have become living statues. There is nothing to eat. Without food they have become horribly emaciated. Their appearance does not bear thinking upon.”52

Despite these difficulties, the position of the Japanese was by no means hopeless. They had good stocks of ammunition, a strong defensive position, and enough men and weapons to hold it for a long time. What was more, they had every reason to expect that Rabaul would quickly reinforce and resupply them. Their orders were to hold, and, with a little help from Rabaul, they were prepared to do so indefinitely.

Enemy Dispositions

Colonel Yokoyama sent some 800 troops to Gona—a key position since it covered the all-important anchorage at Basabua. This force included an Army road-building unit of about 600 men, the troops of a divisional water-purification and decontamination unit, and some walking wounded. The commander of the road-building unit, Maj. Tsume Yamamoto, was put in charge of the defense.53

Colonel Yokoyama himself took over the defense of the vital Sanananda–Giruwa area. He ordered some 1,800 men—headquarters and one company of the 3rd Battalion, 41st Infantry, the main body of the 1st Battalion, 144th Infantry, a portion of the 15th Independent Engineers, a 700-man contingent of Formosan naval laborers, and some walking wounded—to front-line positions at the main junction of the Sanananda and Cape Killerton trails. The salient, known to the Japanese as South Giruwa, was divided into northern, central, and southwestern sectors, and put under command of Colonel Tsukamoto. In reserve at the second trail junction a half-mile to the north, Colonel Yokoyama stationed a second company of the 3rd Battalion, 41st Infantry, a mountain gun battery, about 300 men of the 15th Independent Engineers, and a portion of the antiaircraft battalion. Colonel Yokoyama moved his headquarters to Sanananda at the head of the trail and there stationed a second mountain artillery battery, the cavalry troop, the rest of the 41st Infantry, and most of the naval construction troops in the Giruwa area.

At Buna, Captain Yasuda had under his command the naval landing troops, an element of the 15th Independent Engineers, a section of the antiaircraft battalion, about 450 naval laborers, and a few hundred Army service troops. He had some 75-mm. naval guns, a number of 13-mm. guns, several 37-mm. pompoms, and half a dozen

3-inch antiaircraft guns. The engineers, the antiaircraft troops, and the service troops were assigned to the defense of the plantation, the New Strip, and the bridge between the strips. The Yokosuka 5th and Sasebo 5th troops, as well as the naval laborers, were deployed in Buna Village, Buna Mission, the Coconut Grove, and the Triangle.54

Reinforcements were quickly forthcoming. Tokyo had realized for some time that, despite the emphasis on retaking Guadalcanal, troops would also have to be sent to the Buna–Gona area if the beachhead was to be held. The troops immediately available for the purpose were several hundred 144th Infantry replacements who had just reached Rabaul from Japan and the 3rd Battalion, 229th Infantry, a 38th Division unit whose two sister battalions were on Guadalcanal. The 229th Infantry had had combat experience in China, Hong Kong, and Java and was rated an excellent combat unit.

The battalion under its commander, Maj. Hiaichi Kemmotsu, together with 300 144th Infantry replacements and the new commander of the 144th Infantry, Col. Hiroshi Yamamoto, was ordered to Basabua on 16 November and arrived there by destroyer the following evening. There were about 1,000 men in the convoy, and their arrival brought effective enemy strength at the beachhead to some 6,500 men, not including troops that might be released from the hospital later on and sent to the front.

The incoming troops were transferred to Giruwa by barge and then sent on to the Cape Endaiadere–Duropa Plantation–Buna Strips area. Colonel Yokoyama took command of that area, and Captain Yasuda of the area west of it as far as the Girua River.

The picture at Buna had changed. The Japanese there now had more than 2,500 troops to man the defenses on that side of the river—almost half of them newly equipped and fresh from Rabaul.55

The Situation at Rabaul

On 16 November, the day that Colonel Yamamoto was ordered to Buna, a new area command was established to control operations in New Guinea and the Solomons. The new command, the 8th Area Army, under Lt. Gen. Hitoshi Imamura, was to have under it two armies—the 17th Army under General Hyakutake, which was to operate exclusively in the Solomons, and the 18th Army, under Lt. Gen. Hatazo Adachi, which was to operate in New Guinea. General Adachi arrived at Rabaul on 25 November and assumed command of the 18th Army the same day. His first task was to retrieve the situation in Papua—a very difficult assignment as he was soon to discover.56