Chapter 12: The Fighting West of the Girua

The 900 men of Colonel Yazawa’s 41st Infantry force, which had extricated itself from Oivi on 10 November and fled northward with General Horii along the west bank of the Kumusi River, reached the river’s mouth twelve miles north of Gona toward the end of the month. While trying to cross the turbulent Kumusi on a raft, General Horii and his chief of staff were drowned at Pinga, west of Gona. (See Map IV.) Otherwise the force was intact. Since Yazawa was in no position to fight his way down the coast, Colonel Yokoyama undertook to bring his force back into the battle area by sea. On 28 November Yokoyama sent all the landing craft he had to the mouth of the Kumusi. The craft picked up as much of Yazawa’s force as they had space for, but most of the 1st Battalion, 41st Infantry, was left behind. The boats were attacked on the way by Allied aircraft and several were sunk, but Yazawa and perhaps 500 of his force reached Giruwa early on 29 November, a welcome reinforcement for the hard-pressed beachhead garrison.1

Operations in the Gona Area

Fresh Japanese Troops Reach the Kumusi

Rabaul, meanwhile, was making every effort to reinforce the beachhead. On 22 November a fresh 18th Army unit, the 21st Independent Mixed Brigade, principally the 170th Infantry Reinforced, arrived at Rabaul from Indochina under command of Maj. Gen. Tsuyuo Yamagata. The brigade, a former Indochina garrison unit without previous combat experience, was immediately put on orders for Basabua but, because of the brightness of the moon, was held over at Rabaul for the better part of a week. The first echelon, totaling 800 men and consisting of General Yamagata, his staff, the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry, and a portion of the 1st Battalion, 38th Mountain Artillery, finally left Rabaul on the night of 28–29 November in four destroyers which made for Basabua via the northern route. Apparently thinking that the favorable moon and the speed and maneuverability of the destroyers would see them through, General Adachi (who had reached Rabaul only three days before) failed to provide the movement with air cover. This was a mistake, as he was to discover early the next morning when Allied bombers hit the destroyers in Vitiaz Strait and damaged them

so heavily that they were forced to return to Rabaul.

By then the second echelon of Yamagata’s Force, totaling about 800 men, was loaded and ready to go in four other destroyers. It consisted of the 3rd Battalion, 170th Infantry, less one company, and attached troops, including a complete headquarters communications unit. To save time, General Yamagata and his headquarters attached themselves to the 3rd Battalion, and the convoy left Rabaul late on 30 November, taking the southern route through St. George’s Channel.

This time it had a strong fighter plane escort, mostly naval Zeros. About forty miles southeast of Gasmata, the ships were attacked by six B-17’s, but the bombers were successfully intercepted by seventeen to twenty Zeros. Further attacks closer to Buna, first by four B-17’s and then by six B-25’s, were also intercepted, and the ships managed to reach the anchorage at Basabua safely before daybreak on 2 December. They did not remain long. Before they could even begin to unload, a heavy concentration of Allied aircraft struck at them and forced them to flee the anchorage. The ships moved north and began landing the troops by barge near the mouth of the Kumusi. Dropping flares because it was still dark, Allied planes dived in to disrupt the landing. They bombed and strafed ships and landing craft, but about 500 of the troops aboard and a large part of their supplies managed to reach shore. There they were joined by the 41st Infantry troops whom Colonel Yazawa had been forced to leave behind a few days before.2

Although General Yamagata was ashore and had a sizable force at his disposal, his troubles had only begun. With the Australians between him and Gona, his problem was no mean one. It was how to get his men south where they would be of use in the defense of the beachhead.

The Fall of Gona3

The fighting at Gona had meanwhile entered its final stages, though the Australians were to suffer very heavy losses before they cleared the Japanese out of their burrows in the mission area. The 2/14 and 2/27 Battalions, the first units of the 21st Brigade to reach the Gona area, were committed to action there on the afternoon of 28 November. A patrol of the 2/14 Battalion was sent to investigate a small creek on the beach half a mile east of the mission, from which it was planned that the battalion would attack the next morning. (See photo, page 148.) The patrol reported the area clear of the enemy, and the battalion at once began moving into position. When it broke out at dusk on the coast 200 yards east of the creek, it ran into a hornet’s nest of opposition. From a network of concealed and well prepared positions the Japanese hit the battalion hard, inflicting thirty-two casualties on the Australians before they could disengage.

The next day, after an air strike on known enemy positions east of the mission, the 2/27 Battalion under its commander, Lt. Col. Geoffrey D. Cooper, moved into position west of the creek. Swinging wide through bush and swamp, the 2/14th, Lt. Col. Hugh B. Challen, commanding, debouched onto

the beach several hundred yards east of the creek. The 2/27th was to attack westward along the beach, and the 2/14th, in addition to clearing out any remaining opposition east of the creek, was to send a detachment eastward to deny the enemy the anchorage at Basabua.

The 2/27th was slow in moving forward. When it finally attacked, it met very heavy opposition from hidden enemy positions and in short order suffered fifty-five casualties. The 2/14 Battalion, moving west to clear out the enemy east of the creek, encountered the same kind of opposition and sustained thirty-eight casualties. The pattern was familiar. Heavy losses had thus far characterized every attack on Gona, and the 21st Brigade’s first attack on the place was no exception. Although the brigade had not gone into action until the 28th, it had already lost 138 men and gained little more than a favorable line of departure from which to mount further attacks.

On 30 November, the 2/27th continued its attack westward and again met strong opposition from the hidden enemy. This time it lost forty-five men. The 2/14th, meeting lighter opposition, lost only eleven men and finished clearing the enemy out of his positions east of the creek. The Australians now held most of the beach between Basabua on the right and Gona on the left, but Gona itself was still firmly in Japanese hands.

That evening, Brigadier Dougherty drew up the plan for another attack the next day, 1 December, which would include part of Lt. Col. Albert E. Caro’s newly arrived 2/16 Battalion. The plan provided that the 2/27 Battalion, with a company of the 2/16th on its left, would attack straight east in the morning. At a designated point, the 3 Infantry Battalion, coming up from the headquarters area to the south, would move in on the left and join with the AIF in the reduction of Gona, which lay immediately to the Australian left front.

About 0200 the next morning the Japanese at Giruwa made a last attempt to reinforce Gona. Loaded with 200 41st Infantry troops, who had come in from the mouth of the Kumusi the night before, three barges tried to land about 600 yards east of Gona, but patrols of the 2/27 Battalion drove them off. The barges returned to Giruwa, their mission a failure.4

Shortly after the Japanese landing craft had been driven off, the day’s attack on Gona began. At 0545 artillery and mortars opened up on the enemy, and at 0600 the troops attacked with bayonets fixed. The attack on the beach started off well, but the 3 Battalion mistook its rendezvous point and did not move far enough north. As a result, it failed to link up, as planned, with the company of the 2/16 Battalion on the 2/27th’s left.

Everything went wrong after that. Swinging southwest to cover the front along which the 3 Battalion was to have attacked, the company of the 2/16th on the left and part of a company of the 2/27th on its right, broke into the village that morning, but the Japanese, who were there in strength, promptly drove the Australians out. Casualties were heavy: the company of the 2/16th alone lost fifty-eight killed, wounded, and missing in the abortive attack.

On 3 December, Lt. Col. R. Honner’s 39 Battalion, leading Brigadier Porter’s 30th Brigade, reached the front, rested and rehabilitated after its grueling experience in the Owen Stanleys’ in July and August.

General Vasey had planned to send the battalion to Sanananda, but the 21st Brigade’s losses—430 killed, wounded, and missing, in the five days that it had been in action—left him no choice but to give it to Brigadier Dougherty. Ordering the rest of the 30th Brigade to Sanananda, Vasey assigned the battalion to Dougherty for action in the Gona area.

Next day, the 25th Brigade, which had been relieved by the 21st Brigade on 30 November, was further relieved, along with its attached 3 Infantry Battalion, of its supporting role in the Gona area. The troops, who had long since earned the respite, received their orders to return to Port Moresby on 5 December and at once began moving to the rear. Their part in the campaign was over.

On the 6th, Brigadier Dougherty launched still another attack on Gona. The remaining troops of the 2/16 and 2/27 Battalions, now organized as a composite battalion, jumped off from their positions east of the mission and attacked straight west along the beach. The 39 Battalion, following a now-familiar tactic, moved up from the south and attacked northwest, hoping to reduce the village. The result was the same as before: heavy casualties and only a slight improvement in the Australian position.

Yet for all their losses, the Australians were doing much better than they thought. The Japanese had taken a terrific pounding. They were utterly worn out and there were only a few hundred of them left. The time had come for the knockout blow.

It was delivered on 8 December. At 1245, after a fifteen-minute artillery and mortar preparation, the 39 Battalion attacked Gona from the southeast. It broke into the village without great difficulty and began systematically clearing the enemy out. Exactly an hour later, the composite 2/16–2/27 Battalion, which had been supporting the 39 Battalion’s attack with fire, moved forward—the troops of the 2/27th along the beach, and those of the 2/16th from a start line a few hundred yards south of it. By evening the militia and the AIF had a pincers on the mission, and only a small corridor 200 yards wide separated them.

Acting on Colonel Yokoyama’s orders, Major Yamamoto, still leading the defense, tried to make his way by stealth to Giruwa that night with as much of his force as he could muster—about 100 men. The attempt failed, and the Japanese were cut down in the darkness by the Bren guns of the Australians.

The end came next day. Early on 9 December patrols of the 2/16, 2/27, and 39 Battalions moved into the mission area to mop up. It was a grim business with much hand-to-hand fighting, but the last enemy positions were overrun by 1630 that afternoon. The Australians found a little food and ammunition and took sixteen prisoners, ten of them stretcher cases.

The Japanese at Gona had fought with such single-minded ferocity that they had not even taken time to bury their dead. Instead, they had fired over the corpses and used them to stand on or to prop up their redoubts. Toward the end, the living had been driven to put on gas masks, so great was the stench from the dead.

The stench was indeed so appalling that it had nauseated the Australians. When the fighting was over and the victors were able to examine the Japanese positions, they wondered how human beings could have endured such conditions and gone on living. An Australian journalist who was with the troops describes the scene thus:–

... Rotting bodies, sometimes weeks old, formed part of the fortifications. The living fired over the bodies of the dead, slept side by side with them. In one trench was a Japanese who had not been able to stand the strain. His rifle was still pointed at his head, his big toe was on the trigger, and the top of his head was blown off. ... Everywhere, pervading everything, was the stench of putrescent flesh.5

The Australians buried 638 Japanese dead at Gona, but they themselves had lost more than 750 killed, wounded, and missing. Nor did capture of the village mean the end of fighting in the Gona area. General Yamagata had moved his force from the mouth of the Kumusi to the east bank of the Amboga River, a small stream whose mouth was about two miles northwest of Gona. His hope apparently was to find a weak spot on the Australian left flank and cut his way through to Gona. Australian patrols began clashing with Yamagata’s force on 4 December, the day it crossed the Amboga. The clashes increased in violence, and on 9 December, the day that Gona fell, Brigadier Dougherty ordered the 39 Battalion westward to deal with the enemy.6

General Oda Gets Through

General Adachi meanwhile had not relaxed his efforts to reinforce the beachhead. Early on 7 December, a second landing force of about 800 men—the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry, the remaining company of the 3rd Battalion, 170th Infantry, the regimental gun company, and a heavy machine gun company—left Rabaul in six destroyers. Covered by approximately twenty Zero fighter planes—the convoy took the southern route through St. George’s Channel. A Fifth Air Force B-24 on armed reconnaissance spotted the ships at 1020 the next morning, just as they were leaving the channel for the open sea. The B-24 attacked immediately and scored a hit on one of the destroyers. It was not fatal, and the six ships moved steadily onward to their destination. Late that afternoon, despite strong fighter interception, they were attacked by nine B-17’s which hit them in successive waves. Three of the destroyers were set afire, and seven of the fighters were shot out of the sky without the loss of a single B-17. By 1625 the Japanese had had enough. With dead and wounded aboard, and fires raging on three of the six destroyers, they reversed course and limped home to Rabaul. The air force had successfully turned back the second attempt of the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry, to reach the beachhead.7

General Yamagata’s position had now become very precarious. His troops were being bombed relentlessly from the air, and the Australians were taking increasingly heavy toll of them. Rather than retreat, he ordered his remaining troops to throw up a defensive line in the Napapo–Danawatu area, a few miles northwest of Gona. There they were to hold, awaiting the arrival of reinforcements.8

The reinforcements were not long in coming. The 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry,

which had been forced to return to Rabaul on 8 December, was ordered forward again on the 12th for the third time. In five destroyers, the force of about 800 men left Rabaul under command of Maj. Gen. Kensaku Oda, new commander of the South Seas Detachment, succeeding General Horii. General Oda’s orders were to report to General Yamagata, his senior in rank, for further instructions.

Fortunately for Oda and the troops of Yamagata’s brigade, the weather turned bad. Protected by poor visibility, the Japanese this time used a northern route which led past Madang and through Vitiaz Strait and got through safely. An attempt was made to bomb the ships on 13 December when they were glimpsed fleetingly off Madang, but it was unsuccessful. The weather continued bad, and the destroyers managed to reach the mouth of the Mambare River about thirty miles north of the mouth of the Kumusi at 0200 on the 14th without being detected by the air force. The ships came prepared for a quick getaway. Their decks were loaded down with waterproofed cases of supplies lashed to drums or buoys, and they had brought along plenty of landing craft. Unloading operations began at once. The troops made for shore in the landing barges, and the supplies were pushed overboard into the sea to be washed ashore by the tide.

The air force reached the scene at 0600. By that time unloading was virtually complete. The destroyers had already pulled out of the area, and efforts to bomb them were unsuccessful. However, some of the supplies and a few of the landing barges were still offshore, and the air force lost no time in bringing them as well as the landing beaches under attack. The Japanese lost some barges, men, and supplies, but their losses were on the whole small.9 Thanks to the weather the Japanese could congratulate themselves on an unusually successful run. They were some forty miles north of the beachhead, but they had their launches with them and could hope to reach it by coastwise infiltration.

Though the Japanese had everything ashore and under cover, neither they nor their supplies were beyond Allied reach. Unknown to them, an Australian coast watcher, Lt. Lyndon C. Noakes, AIF, had his camp on a ridge about two miles from the mouth of the Mambare. Discovering the landing almost as soon as it was made, Noakes scouted the Japanese encampment, fixed the position of the tents and supply dumps in relation to a sandy beach easily seen from the air, and then had his radio operator send out a signal giving the exact position of the Japanese camp and dump area. Early the next morning the air force came over and scored hits on the Japanese supply dumps and destroyed several of General Oda’s precious launches. As soon as the bombers left, the Japanese tried shifting remaining supplies to what they apparently thought would be a more secure place, but to no avail. They reckoned without Noakes, who at once reported the shift to the air force. Bombers came over again the next morning and blew up more of General Oda’s supplies and sank more of his launches, repeating the process every time the Japanese tried moving their supplies to a new place.

Oda was delayed several days at the mouth of the Mambare. Critically short of landing craft, he finally managed to move forward to the Amboga with only a portion

of the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry. Hugging the coast, and moving only at night, he and the battalion’s advance echelon reached the mouth of the Amboga on 18 December and at once reported to General Yamagata,10 whose headquarters, previously at Napapo, about three miles northwest of Gona, was now at Danawatu about five miles northwest of it.

By this time the 2/14 Battalion, after leaving a portion of its strength to outpost the Basabua anchorage, had moved west to the Amboga River area and joined the 39 Battalion in operations against General Yamagata’s force in that area. The fighting had been extremely costly to the Japanese. By mid-month they had lost so many men that when General Oda reported to him on the 18th, Yamagata immediately ordered into the line around Danawatu all the troops that Oda had brought with him. Oda himself he ordered to Giruwa with instructions to take command upon his arrival there. Oda and his staff reached Giruwa safely by launch on 21 December, and the general at once took command in place of Colonel Yokoyama.11

As commander at Giruwa Colonel Yokoyama had concerned himself, since the Allies had marched out on the beachhead, chiefly with operations along the Soputa-Sanananda track, and General Oda at once moved his headquarters forward to Sanananda to take personal charge of them.

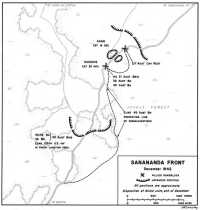

The Sanananda Front

The Roadblock Garrison Holds Its Own

Establishment of the roadblock on 30 November by units of the Baetcke force under Captain Shirley had cut off the Japanese forward units at the junction of the Killerton trail and the Soputa-Sanananda track, the only notable gain since operations against the enemy positions in the track junction began. Shirley’s men, however, had their difficulties. The garrison (Company I, the Antitank Company, a machine gun section of Company M, and a communications detachment of 3rd Battalion headquarters) was itself in a precarious position. Not only was its supply line exposed and vulnerable, but the troops manning the position were subject to continuous attack from almost every direction by enemy forces who outnumbered them several times over. (Map 11.) Situated in a comparatively open space in the midst of a swampy jungle, the roadblock was a position not easy to defend. It was only a few feet higher than the surrounding swamp and lacked natural cover except for a few small trees and a profusion of broad-leaved vines. Tall jungle trees, 25 to 100 feet high, standing over dense undergrowth, surrounded it and afforded the enemy every advantage in sniping or mounting surprise attacks.

The men had dug themselves in as soon as the roadblock was secured. The two machine gun squads of Company M took up their position at the northern end and southern ends of the perimeter. Company I moved into position west of the road, and the Antitank Company dug in east of it. Two 60-mm. mortars were emplaced

Map 11: Sanananda Front December 1942

inside Company I’s perimeter west of the road.

The night the roadblock was established, the Antitank Company repulsed a heavy attack from the northeast and Company I, one from the northwest. Next morning Captain Keast and a strong patrol including Lieutenant Daniels, the Australian forward observer who had done such effective work for Major Zeeff on the right, tried a probing attack just off the southwest end of the perimeter. They ran into a well-laid enemy ambush. Keast and Daniels were killed and nine others were wounded. As quickly as

they could, the men pulled back into the perimeter, the 1st Sergeant of Company I, Alfred R. Wentzloff, and five men of the company successfully covering their retreat by fire. Beginning in the late afternoon of 1 December and continuing till after midnight, at least five separate counterattacks hit the roadblock troops from the southwest, north, northwest, and northeast. All were thrown back with only small casualties to the garrison.12

During this action Major Baetcke, the task force commander, and the rest of his force, Company K and the Cannon Company, were in position in the 3rd Battalion area, west of the roadblock. Originally they had planned to move into the roadblock as soon as it was established. They were to make their move, however, only if Major Boerem’s frontal attack on 30 November succeeded in piercing the Japanese positions in the track junction, and if Boerem was able, in consequence, to reach the roadblock. Boerem’s attack had failed, but the proposal was made on 1 December to send Company K and the Cannon Company into the roadblock anyway. It was argued that Companies I and K and the Cannon and Antitank Companies combined might be able to attack the Japanese rear successfully before the enemy could stabilize his defenses in the area. Major Baetcke finally discarded the plan as too risky. To put it into execution might cause the troops in the roadblock to lose all communication with the rear and could very easily result in the destruction of the entire force. Baetcke’s feeling therefore was that he had to keep Company K and the Cannon Company in position west of the roadblock to supply it and guard its tenuous line of communications.

Supplies came up from the rear on 1 December, and the following morning Major Baetcke sent out the first ammunition and ration party, under command of Captain Huggins, S-3 of the 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry. It had to fight its way into the perimeter but reached it safely about 1100. Shortly afterward, the Japanese launched a heavy counterattack and succeeded in nibbling off fifty yards from the northeast end of the perimeter. Captain Shirley was killed at 1240 and Captain Huggins took over command of the roadblock, which for the following month was to bear his name.13

The Japanese attacked the roadblock repeatedly that day and the next but were repulsed. Major Boerem’s troops could not cut their way through to the roadblock, and Major Zeeff had to be recalled. Action on the track had crystallized into a fight to maintain the roadblock, a situation that scarcely required the presence of a regimental headquarters. Thus on 3 December, when General Eichelberger requested the transfer to the other side of the river of

Colonel Tomlinson and his headquarters, General Herring had no difficulty acceding to the request, even though he had specifically denied a similar request from General Harding a few days before. The transfer was made the next day, 4 December. Tomlinson reached Dobodura by air early that morning, and Captain Boice, his S-2, Captain Dixon, his S-3, and sixty enlisted men of Headquarters Company, under command of 1st Lt. Charles W. Swank, crossed the Girua on foot early the same day. Major Baetcke thereupon assumed command of the remaining American troops west of the Girua, and Major Zeeff became Baetcke’s executive officer.14

Brigadier Boyd ordered a new attack for 5 December. The plan of action provided that Major Baetcke from his position west of the roadblock would strike the Japanese right rear north of the junction, while Major Boerem attacked their left-front positions south of it. Baetcke would use the eighty men of Company K, and Boerem, the 220 men of Companies C and L. Company L had been assigned to Boerem upon Zeeff’s recall from operations on the right.

At 0715 on the 5th, all the Allied guns and mortars on the front opened up. Fifteen minutes later the troops jumped off for the attack. Leaving the Cannon Company in position under Captain Medendorp, Major Baetcke pushed straight south with his eighty-man force. Advancing through a heavy field of kunai grass which made it impossible to see more than a few feet ahead, Major Baetcke’s force covered about 300 yards before it was halted by heavy machine gun and mortar fire. Major Boerem, with his 220 men, did not do as well. Running into very heavy opposition, he gained less than 100 yards before his attack was also stopped. Losses were heavy. Baetcke and Boerem between them lost ninety men that day out of the 300 engaged—two killed, sixty-three wounded, and twenty-five missing.15 It was clear that Colonel Tsukamoto’s troops were firmly entrenched and that rooting them out would be no easy task.

At the roadblock the garrison had been heavily engaged. The Japanese had thrust from several directions on 3 December and had repeated the performance the next day. Captain Huggins was wounded on the 5th, the day that the attack put on by Majors Baetcke and Boerem had failed, but remained in command for lack of someone else to take his place.

The enemy had tried to infiltrate Company K’s position west of the roadblock on the 4th and laid a skillful ambush about 300 yards out of the roadblock on the 5th. When Lieutenant Dal Ponte tried to lead a sixty-man ration and ammunition party into the block that morning, the hidden Japanese tried to entrap him. Although Dal Ponte’s party consisted mainly of cooks, clerks, and mortarmen, each carrying a forty-pound load, the men gave a good account of themselves. Not only did the ambush fail, but the heavily burdened troops turned the tables on the enemy and at one point almost broke through to the roadblock. After fighting all day and suffering a half-dozen casualties including two killed, the troops were finally forced to withdraw when the Japanese,

strongly reinforced, seemed about to envelope them.16

Another attempt to get rations and ammunition through to the roadblock on 6 December also failed. By this time the roadblock garrison was down to its last day’s rations, and it would soon be out of ammunition. There was nothing for it but to try again.

Malaria was meanwhile claiming more American victims. Losses due to fever had been few at first, but by the end of the first week in December 20 percent of the command had contracted it, and the percentage was rising. On 7 December Major Baetcke and Zeeff both came down with malaria and had to be evacuated. Major Boerem took command of the entire force, which now numbered fewer than 800 men. The 30th Brigade under Brigadier Porter relieved the 16th Brigade that day, and Boerem came under Porter’s command.

One of Porter’s first acts was to relieve Companies C, D, and L in the front lines near the track junction, and to replace them with his 49 and 55/53 Battalions. Satisfied that none of the Americans could be spared, Porter would go no further. He did not accede to a request by Boerem that the American troops be withdrawn to the rear for rest and reorganization, nor did he authorize the return to the 32nd Division of some 350 of them, though this had been promised to General Eichelberger some days before by New Guinea Force. Instead he ordered all of Major Boerem’s troops, except those in the roadblock and west of the roadblock, to take up supporting positions immediately to the rear of the 49 and 55/53 Battalions. On the same day he had the two Australian battalions attack frontally toward the road junction in an attempt to break through the roadblock.17

The 49 Battalion, Lt. Col. O. A. Kessels commanding, jumped off at 0945 on 7 December after a careful artillery and mortar preparation. By 1400 it was stopped completely with a loss of ninety-nine killed, wounded, and missing. Brigadier Porter then ordered the 55/53 Battalion to pass through the position held by Colonel Kessels’ battalion and to resume the attack. The 55/53rd, Lt. Col. D. J. H. Lovell commanding, attacked at 1515 with even worse results. Cut down by enemy crossfire, the leading companies of the battalion lost 130 killed, wounded, and missing by the end of the day and gained virtually no ground whatever.

In a few hours of fighting Brigadier Porter had lost 229 men (more men than Major Boerem had had to attack with on 5 December, two days before) and had completely failed to dislodge the enemy. Colonel Tsukamoto’s defense was still potent, and it was to be twelve days before the Australians, who now embarked on “a policy of patrolling and edging forward wherever possible,” were to try a major attack again.18

Nor had things gone well in the roadblock area. A further attempt to break through to the block early that morning was a failure, and the supply party returned in the evening with its supplies undelivered. The Japanese were blocking the trail, in strength, the men reported, and they had not been able to get through.

Lieutenant Dal Ponte at once volunteered to take the supplies through. Taking command of the same force that had failed to get through the day before, he moved out early the next morning. About 300 yards from the roadblock, at nearly the same spot where the Japanese had held up Dal Ponte three days before, the supply party was halted and pinned down by machine gun fire from hidden enemy positions on either side of the trail. Dal Ponte knew what to do. Deliberately exposing himself to draw fire, he located first one enemy position and then the other and personally led infiltrating parties which either silenced the enemy or caused him to withdraw. Though repeatedly attacked the rest of the way, the supply party successfully fought its way into the roadblock and Dal Ponte immediately took command of the garrison. Huggins, who had been carrying on despite his wounds, was evacuated to the rear that night when the supply party returned to the position held by Company K and the Cannon Company to the west of the block.19

After arriving at the rear with the supply party, Captain Huggins gave a discouraging report on conditions in the roadblock. He described it as about 200 yards square, with the command post and aid station near the center, “all in elliptical pattern.” Fevers were raging, he said, and food, ammunition, and medical supplies were running low. The men had to live in holes, and the disposal of wastes presented a difficult problem. Of the 225 men left in the garrison, he thought that perhaps 125 were in condition to fight.20

As Dal Ponte was to recall the matter:

... water was procured from a hole dug about 3 feet deep, ... chlorinated for drinking by administering individual tablets. Another source of water supply was that which the men would catch in their pouches from the downpour during the previous night. ... The disposal of wastes and the burying of dead had to be accomplished within [the] area. ... Rations were very meager because the ration parties concentrated on ammunition. ... Chocolate bars, bully beef, and instant coffee were the main items of food when provided. ... The weather was almost without [exception] rain at night and boiling hot sun during the day. ... The men were able to get hot coffee by using canned heat that they had saved from previous ration issues or by an expedient consisting of sand and the gasoline taken from the captured trucks.21

On 10 December, with communications again out, a second ration party led by 1st Lt. Zina Carter was able to get through to the roadblock. Lieutenant Carter brought back a message from Lieutenant Dal Ponte that fevers, foot ailments, and ringworm were increasing daily, and that while the spirit of the men was good they were worn out and desperately needed relief.

Life at the roadblock was hard. Although the troops were hungry, feverish, and in need of sleep, they were on an almost perpetual alert. Crouched low in their muddy foxholes, their feet going bad, they repelled attack after attack. Sometimes the Japanese got so close to their slit trenches that the troops were able to grab them by the ankles and pull them in. Several Japanese officers were caught and killed in this way.22

Deep in the swamp to the west Company K and the Cannon Company were little better off than the troops in the roadblock. On 30 November, the day the block was established, the journal of Company K noted: “We have been living in holes for the last six days. Between mosquitoes, Japs, heat, bad water, and short rations, it has sure been hell on the men.” Four days later, the entry was: “In position, but the men are getting weaker from lack of food and the hot sun is baking hell out of them.” It rained the following two nights, and, as the journal put it: “Did we ever get wet.” But, “Hell,” it continued, “we’ve been wet ever since we got to New Guinea.” By 9 December, things were definitely worse. “What is left of the company,” the journal noted, “is a pretty sick bunch of boys. It rained again last night, men all wet, and sleeping in mud and water.” A day later, on the 10th, things looked up a bit. The troops had something to be happy about: they received hot coffee. The entry for the day reads: “The men haven’t washed for a month, or had any dry clothing, but we did get some canned heat and a hot cup of coffee. Sure helps a lot. Boy, was it wonderful.”23

Communications between the supply base to the west and the troops in the roadblock were poor. The radios in use, the SCR-195 and SCR-288, proved very unreliable. Not only did the Japanese frequently cut the wire laid to the roadblock, but they apparently made a practice of tapping it frequently. Extreme care was therefore observed in telephone conversations. As an additional precaution, frequent use was made of Dutch, a language familiar to many Michigan troops whose forebears had come from the Netherlands.

The condition of the troops south of the track junction was no less bad. Despite double doses of quinine, man after man of Companies C, D, and L was coming down with malaria. More than a quarter of the command had fallen ill or had been evacuated with fever, and the percentage was climbing steadily. Casualty figures had assumed the aspect of a nightmare. By 10 December Boerem had but 635 men fit for duty. Two days later he had only 551, and each day saw the effective strength of his command shrink still further.

On 12 December, after several attempts the day before had failed to reach the roadblock, Major Boerem asked Brigadier Porter to relieve the garrison as well as Company K and the Cannon Company, but without success. Heavy rain and fierce enemy opposition defeated all attempts to supply the roadblock on the 13th. All efforts to establish radio or telephone contact with the garrison that day also failed; even runners were unable to get through.24

Things went better on the 14th. A party of fifty-five men fought its way into the roadblock early that morning with rations, ammunition, and medical supplies. It broke through just in time, for the garrison was low on food and was about to run out of ammunition.25

Unable to get anywhere with Brigadier Porter in the matter of the relief of his troops, Major Boerem saw General Vasey early on the 14th. As the detachment journal notes: “No doubt the Major emerged a bit victorious, for there was a gleam of accomplishment in his eye upon his return to the C. P.” That same afternoon, Company K and the Cannon Company packed up and moved to the rear for a well-earned rest. Their place was taken by Australian troops.26

The Relief of the Dal Ponte Force

The relief of the troops in the Huggins Block was to take longer. On 15 December the 2/7 Australian Cavalry Regiment began arriving at Soputa. Three hundred and fifty men, the regiment’s advance element, fought their way into the roadblock at 1530 on the 18th. Led by their commander, Lt. Col. Edgar P. Logan, the cavalrymen dug themselves in at once beside Lieutenant Dal Ponte’s troops. The 49 Battalion, operating southeast of the roadblock, was held up nearly all day, and the 36 and 55/53 Battalions, attacking frontally, made only negligible progress.

Colonel Logan’s instructions were to attack northward the next morning, the 19th, in concert with attacks on the track junction by the 30th Brigade. The Dal Ponte force would be relieved as soon as the 39 Battalion, which had been mopping up east of the Amboga River, could reach the Soputa-Sanananda track.

Action flared up everywhere on the front on the 19th. Early in the morning, while the 2/16 and 2/27 Battalions began relieving the 39 Battalion in the Napapo-Danawatu area, the main body of the cavalry unit moved out of the roadblock and attacked north. The 30th Brigade, joined by the newly arrived 36 Battalion, Lt. Col. O. C. Isaachsen commanding, mounted an all-out attack on the Japanese positions in the track junction. The 36 and 55/53 Battalions attacked frontally, the 49 Battalion attacked east of the track, and Major Boerem’s troops executed a holding attack by fire.27

Cutting to the left around heavy Japanese opposition immediately northeast of Huggins, the cavalry troops advanced several hundred yards and held their gains. The 36 and 55/53 Battalions breached several Japanese positions in the track junction area, and the 49 Battalion pushed forward to a point just outside the roadblock. A strong attack on Huggins was repulsed, and the 2/7 Cavalry pocketed and mopped up a Japanese force 300 yards northeast of the roadblock. There the cavalrymen set up a new perimeter, which they named Kano. In

the day’s fighting, they lost their commander, Colonel Logan, who was killed in action.

Some progress was registered on 20 and 21 December. The 36th and 55/53 Battalions reduced several more enemy pockets in front of the track junction. The 49 Battalion, which by this time had fought its way into Huggins, began policing a supply route to it from the southeast. The 2/7 Cavalry consolidated at Kano and probed toward Sanananda.

On 22 December Brigadier Dougherty, 21st Brigade Headquarters, and the 39 Battalion reached Soputa from Gona. They moved directly to the roadblock, where Brigadier Dougherty set up his headquarters. Dougherty took over command of the 49 Battalion, of the 2/7 Cavalry, and of the American troops in the roadblock the same day. Brigadier Porter, who was to mop up the remaining enemy pockets in the track junction area, was left in command of the 36 Battalion, the 55/53 Battalion, and the remaining elements of Major Boerem’s command.

At 1500 that day Brigadier Dougherty assigned to the 49 Battalion the role of protecting the line of communications from the southeast (which being over better terrain than that from the southwest was the supply route used thereafter). He ordered the 2/7 Cavalry to continue its attacks northward, and the 39 Battalion to relieve the garrison and hold the roadblock.28

The relief was effected that afternoon. At 1750, after checking with Major Boerem, Lieutenant Dal Ponte assembled his command and marched it out of the roadblock. After twenty-two days of continuous fighting against heavy odds, the 126th Infantry troops in the roadblock had finally been relieved. They were dazed, sick, and exhausted, and their feet were in such bad shape that they could scarcely use them. Their spirit, nevertheless, was high,29 for their defense of the roadblock had been superb.

Stalemate on the Sanananda Front

For the Australian units now in the roadblock area, things went little better than before. It was discovered that the Japanese had a very strong defensive position between Huggins and Kano, and an even stronger position north of Kano. Brigadier Dougherty was able to make only slight and very costly progress in his attacks to the northward. Nor did Brigadier Porter’s mopping-up operations in the track junction area go much better. Though a portion of their outer line had been breached, Colonel Tsukamoto’s troops, with equally strong defenses to the rear, continued to fight with the same ferocity that had characterized the defenders of Gona. There was a difference, however: most of the Japanese at Gona had been service and construction troops with little combat experience; those defending the track junction were battle-tested infantry

troops, probably as good as any the Japanese Army had.

Rooting out the enemy continued to be a slow and costly business. The 30th Brigade attacked west of the track, with the 55/53 Battalion on the left and the 36 Battalion, less one company, on the right. Major Boerem attacked east of the brigade with the company of the 36 Battalion on his right. The American front-line troops, then under command of Captain Wildey of Company M, made slow progress in their sector, and the Australians on either side of them did little better in theirs.30

Tsukamoto’s troops were by no means passive in their defense. On 24 December, American troops on the right-hand side of the track cleared out an enemy trench and machine gun position with hand grenades.31 To hold it, however, they had to beat off repeated Japanese counterattacks. On the night of 28–29 December forty Japanese, armed with light machine guns, rifles, and explosive charges, infiltrated the Allied rear and blew up a 25-pounder. Thirteen Japanese were killed and one was taken prisoner, but the enemy had traded blow for blow.32

The Japanese struck again on the night of 30–31 December. A Japanese raiding party succeeded in infiltrating the headquarters perimeter of the Australian company on the American right. Surprise was complete. The company commander and several others were killed, but only a few of the Japanese were accounted for. The rest got away safely in the dark.33

Hacking a way through the Japanese defenses, which were in depth for a distance of at least three-quarters of a mile, continued to be grueling work, in which progress was measured in terms of a few yards, and the capture of a single enemy pillbox or trench was a significant gain. The story was the same in Brigadier Dougherty’s area as in Brigadier Porter’s. Fighting was bitter, and progress slow. Except for minor gains, the entire front was at a stalemate.

The Plight of the American Troops

The conditions under which the troops lived were almost indescribably bad. Colonel Boerem, then Major Boerem, recalls them in these words:

Fighting for weeks ... with the prevailing wind in our faces continually carrying the stink of rotting bodies to us [raised] a difficult morale problem ... Most of my time was spent going from one soldier to another in an endeavor to raise morale. After taking one position, one hundred and sixty (160) Australian

Boatload of rations is brought up the Girua River, December 1942 (Collapsible assault boat)

and American dead were counted in all stages of decomposition. We made no attempt to count the Japs.

Boerem did his best to rest the men but was able to relieve “only one or two at a time to go to the rear, bathe in the river, get some clean clothes and return.” Food consisted principally of the C ration “put up in Australia with mutton substituted for the beef component.” The only supplement was bully beef and D ration bars of hard, concentrated chocolate—a diet, Boerem observes gravely, no one could stomach for very long.34

To add to his other troubles, Boerem was beginning to experience the greatest difficulty in finding enough troops to man the American part of the line. On Christmas Day he had only a little more than 400 men left in condition to fight. A few days later he had less than 300, and the number was constantly shrinking. To provide troops for the front and to guard the Australian artillery and headquarters perimeter, it became necessary to institute a round-robin system of relief whereby the available troops were rotated between the front line, the headquarters perimeter, and the artillery guard. The time came when, despite the most rigorous screening to catch all possible

troops for front-line duty, there were not enough men left with whom to attack.

By the year’s end, even the seemingly indestructible Major Boerem was worn out and needed to be spelled off. General Eichelberger sent Maj. Francis L. Irwin to replace him. Boerem nevertheless stayed on with the troops at the front for more than a week longer. There was little left of the American force when Major Irwin arrived. On 31 December, the day he took command, effective American strength west of the Girua River was little more than a company, and the situation in the American sector was grim indeed.

Captain Wildey in command on the front line had been wounded on 26 December. He had been succeeded by 1st Lt. John J. Filarski, 1st Battalion S-4, who had been Lieutenant Dal Ponte’s executive in the roadblock. When Filarski was evacuated on 29 December, totally exhausted, Dal Ponte took command of a force that consisted in all of seventy-eight men from ten different companies. All that the troops could do was to hold their lines and support the Australians on right and left by fire.35 “Our tactics during this period,” Dal Ponte recalls, “consisted primarily of holding our sector, pinpointing targets of opportunity, delivering mortar and artillery fire on these targets, and patrolling the flanks and rear of our position ... ”36 There were not enough men left to do more.

On 10 December, three days after Major Boerem took over from Major Baetcke, the effective American strength west of the Girua was 635; on 13 December it was 547. By 19 December Boerem had 510 effectives; by Christmas Eve the number had gone down to 417. On New Year’s Day, the day after Major Irwin took command, the Americans had suffered 979 casualties—73 killed, 234 wounded, 84 missing, and 588 evacuated sick—and there were only 244 men left in condition to fight.

Companies K and L had entered the battle on 22 November at full strength; on Christmas Day they were down to sixty-one and thirty-six men respectively. A week later Company K had twenty-eight men left, Company L had seventeen, and the other companies had suffered proportionately.37

The condition of the effectives is well expressed in the informal journal kept by Company K. The entry for Christmas Day noted that the men were sick and feverish, and that the situation was getting worse all the time. Three days later, it read: “The men are getting sicker. Their nerves are cracking. They are praying for relief. [They] must have it soon.”38 But it was to be some time before the men could be relieved. Brigadier Porter had no troops with which to replace them. Until he did, they would have to remain where they were, despite their steadily worsening physical condition.

The Japanese Reinforce the Beachhead

The Enemy Situation

Attacking northward from Huggins and Kano, Brigadier Dougherty continued to find the going exceedingly difficult. His troops were at grips with the Japanese intermediate defense line, a line seemingly as strong as that on which Brigadier Porter was working lower down on the track. This line, which had come under (Genera] Oda’s command upon his arrival at Giruwa on 21 December, included a forward and a rear position. The forward position was at the junction of the Sanananda track and the subsidiary trail leading to Cape Killerton. It consisted of two independent perimeters, one on either side of the track. The rear position cut across the track and the trail 500 yards farther to the northeast and was about 1,500 yards long. Its main defenses consisted of three interconnected perimeters straddling the east-west stretch of the track—two north of it and one south.

Oda commanded a sizable force: the troops of the 41st Infantry who had come in from the Kumusi with Colonel Yazawa; the remainder of the 144th Infantry replacements who had arrived from Rabaul on 23 November; approximately 300 men of the 15th Independent Engineer Regiment; the remaining strength of the 47th Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion; a battery of the 55th Mountain Artillery; and a number of walking wounded. His troops were not only strongly entrenched in bunkers, but they could also be reinforced at will from troops in reserve at Sanananda and Giruwa.39 Theoretically at least, Oda was in as favorable a position to hold the second line of defense as Colonel Tsukamoto had been to hold the first.

Fortunately for the Allies, the enemy supply situation was desperate. The Japanese, especially Colonel Tsukamoto’s troops in the track junction, were short of food, weapons, grenades, and all types of ammunition. Colonel Tsukamoto’s troops had to depend on the dribbles of food that could be supplied them via the Killerton trail, and they were on the verge of starvation. General Oda’s troops were not much better off. They were down to a handful of rice a day and were eating roots, grass, crabs, snakes, or whatever else they could find in the area that was edible.40

The hospital at Giruwa was a scene of unmitigated horror. There was no medicine and no food. The wards were under water; most of the medical personnel were dead and those who remained were themselves patients.41

On 11 December, Colonel Yokoyama tried to give Rabaul some intimation of how bad conditions really were. The picture was so black that General Adachi’s operations officer, Lt. Col. Shigeru Sugiyama, replied that he doubted that things had really reached such a pass. “It is hard to believe,”

Sugiyama wrote, “that the situation is as difficult as stated.”42

Rabaul was probably more worried about the situation at the beachhead than it cared to admit. It had planned to establish a major supply base at the mouth of the Mambare River, with a secondary base at the mouth of the Kumusi. Submarines would bring in the supplies from Rabaul to the base in Mambare Bay where they would be unloaded. Later, they would be reloaded on large cargo-carrying landing craft, and the landing craft traveling at night would bring them forward by stages to Giruwa.

The plan, well-conceived and carefully worked out, had already broken down. For no sooner would the submarines bring in supplies than Lieutenant Noakes, the coast watcher in the area, would find out where they were stored and radio the information to Port Moresby. A few hours later, the air force would reach the scene, blow up the enemy dumps, and usually account for some of the landing craft as well.43

To add to the enemy’s difficulties, a U. S. motor torpedo boat squadron, Task Force 50.1, based at Tufi since 20 December, was ranging the coast west of Gona to intercept Japanese coastwise shipping. On Christmas Eve, the squadron sank the I-18, a 344-foot, 3,180-ton submarine just off the mouth of the Mambare. Later the same night, it destroyed two large Japanese barges filled with troops, fifteen or twenty miles east of Mambare Bay. The troops were part of the rear echelon of the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry, which had finally received sufficient landing craft to get it through to the Amboga River area. This was the only mishap the troops were to suffer in transit. The rest of them reached their destination safely that night and reported to General Yamagata.44

Yamagata is Ordered Forward

General Adachi had apparently decided to hold the rest of the 170th Infantry at Rabaul until the supply situation at the beachhead had clarified itself. On 26 December he ordered Yamagata to get his troops to Giruwa immediately. Yamagata complied at once by ordering a 430-man advance echelon to the beachhead the following day. The echelon, which included elements of the 1st Battalion, 170 Infantry, the 1st Battalion, 41st Infantry, the brigade engineer unit, the regimental gun company, and the regimental signal unit, began leaving for Giruwa that night by barge. The movement went so smoothly, and was so well-executed, that all the troops got through without being detected by either the Air Force, Task Force 50.1, or the Australian patrols operating along the coast.

General Yamagata himself arrived at Giruwa on 29 December with part of the 3rd Battalion, 170th Infantry. Only a rear guard made up of elements of the

1st Battalion, 170 Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 170th Infantry, remained in the Amboga River area, with the mission of engaging the Australians as long as possible. The rest of Yamagata’s troops reached Giruwa by the 31st. The 21st Brigade, which was mopping up along the banks of the Amboga, knew nothing of the move. Between 700 and 800 men had successfully reached Giruwa,45 the last reinforcements the Japanese were to receive.