Chapter 15: Urbana Force Closes on the Mission

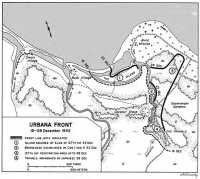

On 16 December, in compliance with orders of Advance New Guinea Force, Colonel Tomlinson, then in command of Urbana Force, ordered a platoon of Company F, 126th Infantry, led by Lieutenant Schwartz to Tarakena, a point about one mile northwest of Siwori Village. The move was taken to prevent the Japanese in the Giruwa area from reinforcing their hard-pressed brethren east of the river. Buna Force issued orders the next day for the capture of the island and Triangle. The island was to be taken on 18 December, the day of the tank attack on the Warren front; the Triangle, one day later. An element of the 127th Infantry would take the island; what was left of the 126th Infantry, the Triangle.1 (Map 14)

The Search for an Axis of Attack

The Situation: 18 December

Capture of Buna Village had narrowed down the ground still held by the Japanese on the Urbana front, but the main objective, Buna Mission, was still in Japanese hands, and seemingly as hard to get at as ever. The problem was to find a practicable axis of attack, and this the projected operations were designed to provide. Seizure of the island would not only make it possible to bring the mission under close-in fire but might supply a jumping-off point for a direct attack upon it from the south. The Triangle, in turn, would furnish an excellent line of departure for an advance through Government Gardens to the sea, a necessary preliminary to an attack on the mission from the southeast.

The fresh 127th Infantry would be available in its entirety for these operations. The 3rd Battalion was already in the line and had been for several days. After consolidating at Ango, the 2nd Battalion had just begun moving to the front. Companies E and F were on their way there, and Headquarters Company and Companies G and H were moving forward. The 1st Battalion was still being flown in and would come forward as soon as its air movement was completed.

With the 127th Infantry moving up steadily, Colonel Tomlinson reshuffled his line. Company I, 127th Infantry, took the place of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, in the area between the island and the Coconut Grove. The battalion, less the mortar platoon of Company H, which remained behind, was ordered to Simemi for a well-earned rest. The 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, took over in the Coconut Grove and moved troops into position above and

Map 14: Urbana Front 18–28 December 1942

below the Triangle. Companies E and F, 127th Infantry, meanwhile reached the front and went into reserve. A mixed platoon of the 126th Infantry under 1st Lt. Alfred Kirchenbauer began moving to Siwori Village to replace the 128th Infantry troops there, and the Schwartz patrol of 15 men started out for Tarakena.2

The First Try at the Island

On 17 December Colonel Tomlinson gave Company L, 127th Infantry, orders to take the island the next morning. This was to be no easy task, for the footbridge to the island had been destroyed and the creek was a tidal stream, unfordable even at low tide. The troops had no bridge-building equipment, and the distance from one bank to the other was too great to be bridged by felling trees. One alternative remained: to have

swimmers drag a cable across the stream. This expedient worked, and two platoons and a light machine gun section of the company, commanded by Capt. Roy F. Wentland, got across just before noon on 18 December.

The two platoons, joined shortly thereafter by a third, moved cautiously forward along the eastern half of the island without meeting any opposition. However, when they started moving toward the bridge that connected the island with the mission, they ran into very heavy fire from concealed enemy positions. In the fire fight that followed, five men, including Captain Wentland, were killed and six were wounded. The heavy enemy fire continued, and the troops, under the impression that they were heavily outnumbered, pulled back to the mainland that night, leaving the island still in enemy hands.3

The 126th Infantry Attacks the Triangle

The attack on the island had failed. The attack on the Triangle was next. This narrow, jungle-covered tongue of land set in the midst of a swamp, and covering the only good track to Buna Mission, was in effect a natural fortress. Improving upon nature, the Japanese had hidden bunkers and fire trenches on either arm of the Triangle and in the track junction itself. To try to storm the junction from the south meant taking prohibitive losses. To try taking it from the north by advancing into its mouth by way of the bridge over Entrance Creek was likely to be almost as costly. There was no room for maneuver in the narrow and confined area east of the bridge, and no way to take the track junction from the south except by advancing through interlocking bands of fire.

The plan of assault, profiting from the experience gained in an abortive attack on the place by Companies E and G, 128th Infantry, on 17 December, called for two companies of the 126th Infantry to attack across the bridge from the Coconut Grove, and a third company to block the position from the south. The jump-off would be preceded by an air strike on the mission and a preparation on the Triangle itself by Colonel McCreary’s seventeen 81-mm. mortars, which were in battery about 300 yards south of the bridge to the island. Since the Triangle was narrow and inaccessible, neither air nor artillery would be used in direct support of the troops lest they be hit by friendly fire.

Some 100 men from Companies E and G, plus the attached weapons crews of Company H, were to mount the attack. They crossed the bridge over Entrance Creek and moved into the bridgehead area at the mouth of the Triangle at 2200, 18 December. Shortly thereafter, the thirty-six men of Company F, the holding force, went into position in the area below the track junction.4

Beginning at 0650 the following morning, nine B-25’s dropped 100-pound and 500 pound demolitions on the mission. They were followed at 0715 by thirteen A-20’s which bombed and strafed the coastal track between the mission and Giropa Point. The

A-20’s dropped 475 twenty-pound parachute and cluster fragmentation bombs and fired more than 21,000 rounds of .30-caliber and .50-caliber ammunition during the attack. They probably did the enemy a great deal of damage, but their accuracy left much to be desired. A stick of four bombs was dropped within fifty yards of a bivouac area occupied by the 127th Infantry, and a chaplain visiting the troops at Buna Village was hit by bullets meant for the Japanese at Giropa Point.5

At 0730 Colonel McCreary’s mortars, which were so disposed that they could drop their shells on any point in the Triangle, began firing their preparation. Fifteen minutes later Companies E and G attacked straight south under cover of a rolling mortar barrage. The barrage did the attacking troops little good. They were stopped by enemy crossfire just after they left the line of departure. In the forefront of the attack, Captain Boice did everything he could to get things moving again, but the crossfire proved impenetrable. Every attempt by the troops to slip through it only added to the toll of casualties. At 0945 Boice was mortally wounded by mortar fire and died shortly afterward. He was succeeded as battalion commander by Capt. John J. Sullivan, who had just come up from the rear with a handful of replacements.6

On General Eichelberger’s orders the mortars laid down a concentration of white phosphorous smoke in the Triangle at 1415, and the attack was resumed. The troops gained a few yards with the help of the smoke, but were again stopped by enemy crossfire. At 1600 a third attack was mounted. This time the mortars fired a 700 round preparation—some forty rounds per mortar—but the result was the same; the men found it impossible to break through the murderous enemy crossfire. When night fell and the utterly spent troops dug in, they had lost forty killed and wounded out of the 107 men who had begun the attack.7

Obviously in no condition to continue the attack, the two companies were relieved early the following morning by Company E, 127th Infantry, and went into reserve with the rest of the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry. Except for Company F, which continued for the time being at the tip of the Triangle, the troops in the Siwori Village–Tarakena area, the whole battalion, now 240 men all told, was in reserve. The main burden of operations henceforward would be on the 127th Infantry.8

The 127th Infantry Takes over the Attack

The attack on the Japanese positions in the Triangle was resumed on 20 December. The plan was prepared the night before. Since it provided for an artillery preparation,

safeguards were taken to ensure that the artillery did not hit the attacking troops. Company E, 127th Infantry, which was to deliver the blow was ordered into the Coconut Grove at daybreak. Its instructions were to remain there under cover until ordered across the creek, over which a second footbridge had been built a short distance from the first. Company F, 126th Infantry, still in place below the Triangle, was ordered to pull back about 300 yards in order to permit the artillery to use the track junction as its registration point.

After registering on the junction, the Manning battery of 25-pounders and the 105-mm. howitzer, both using smoke, were to fire on the enemy positions in the track junction for five minutes at the rate of two rounds per gun per minute. A second five minute preparation was to follow at a somewhat faster rate. As soon as the registration was over and the first five-minute preparation began, Company E, covered by smoke from the artillery and the mortars, would dash across the two bridges, form up on the east bank of the stream at a position south of the original crossing, and wait out the artillery fire there. When the artillery fire ceased, the mortars, firing a salvo every minute, were to place a concentration of forty rounds of white phosphorus on the target. When the first smoke shell from the mortars went down, Company E was to rush forward, get within close range of the bunkers under cover of the smoke, and clear out the enemy with hand grenades.9

The artillery registered in at 0845. As soon as it began firing its first preparation, the troops dashed across the creek “in a cloud of smoke.” Though General Eichelberger confessed to General Sutherland that night that he had been very much worried that some of them might be hit, “as this is very thick country and our troops are in close to the junction,” not a man was hit by the artillery. Just as everything seemed to be going well, some “trigger-happy” machine gunners on the west bank of the creek, to the rear of the line of departure, spoiled everything by opening fire prematurely. This unauthorized firing from the rear threw the inexperienced troops along the line of departure into great confusion. When the troops finally attacked at 1000, they found the enemy alert and ready for them. In an hour and a half of action Company E was unable to get within even grenade distance of the enemy.10

The attack was called off at 1130. Capt. James L. Alford, the company commander, thereupon proposed a new attempt. Alford’s proposal was that a reinforced platoon, led by 1st Lt. Paul Whittaker, with 2nd Lt. Donald W. Feury as second-in-command, infiltrate the low-lying area in the center of the Triangle with the help of fire from the rest of the company. When the platoon was as close as it could get to the enemy bunkers, it would charge and clean them out with hand grenades. Colonel Tomlinson sanctioned the plan, but General Eichelberger, who was present, vetoed it immediately as reckless and likely only to cause useless casualties. On Captain Alford’s assurance that the two lieutenants and the men who were to make the attack were confident of its success, the general let the attack proceed.11

127th Regimental Headquarters command post. Colonel Grose, seated, studies plans for the next attack

General Eichelberger’s original misgivings were quickly justified. With S.Sgt. John F. Rehak, Jr., leading the way, the platoon managed to get within grenade distance of the bunkers and charged. The Japanese had meanwhile pulled out of the bunkers apparently in anticipation of just such a move. They caught the platoon with enfilading fire and nearly wiped it out with a few bursts of their automatic weapons. Seven men, including Lieutenant Feury, Lieutenant Whittaker, and Sergeant Rehak, were killed, and twenty were wounded. The two attacks had gained nothing, and they had cost Company E thirty-nine casualties—better than 40 percent of its strength—in its first day of combat.12

Colonel Tomlinson called off the attack at 1335, and a badly rattled Company E spent the next few hours getting its dead and wounded out of the Triangle—a perilous business because the Japanese, taking full advantage of the situation, were laying down heavy fire on the rescue parties. When the

job was done, the company, less outposts in the mouth of the Triangle, withdrew to the Coconut Grove where the men were made as comfortable as the circumstances would permit.13

At 1410 Colonel Tomlinson, who was physically exhausted, suggested to Colonel Grose that he take over command of Urbana Force inasmuch as the 127th Infantry now made up the great bulk of the troops in the line. Grose’s reply was that it was not within his authority to assume command. He told Tomlinson that he could take over only if ordered to do so by General Eichelberger. At 1522 Tomlinson called Eichelberger and asked to be relieved of command of Urbana Force. Realizing that Tomlinson had been under strain for too long a time, General Eichelberger relieved him at once and ordered Colonel Grose to take his place. Grose assumed command of Urbana Force at 1700, and all elements of the 127th Infantry not already there were immediately ordered to the front.14

The Attack Moves North

The Plan To Bypass the Triangle

It had become perfectly clear by this time that the reduction of the Triangle would be an extremely difficult task. Not only did the troops have no room to maneuver, but the enemy’s fire permitted not a single man to get through alive. It became a question therefore of whether it might not be wiser to break off the fight and try to find a better line of departure elsewhere for the projected drive across the gardens to the coast.15

General Eichelberger had made such a suggestion to General Herring on 19 December. Herring saw the point and authorized Eichelberger to bypass the Triangle if the next day’s attack upon it also failed.16

When the attempt on the 20th did fail, General Eichelberger began immediately to plan for a new axis of attack across the gardens. As he explained the situation to General Sutherland that night: “General Herring is very anxious for me to take the track junction, and I am most willing, but the enemy is ... strong there and is able to reinforce his position at will. I am going to pour in artillery on him ... and I am going to continue that tomorrow morning. Then I am going to find a weak spot across Government Gardens.”17

The next morning General Eichelberger ordered Company E, 127th Infantry, to contain the Triangle from the north and Company F, 126th Infantry, to continue blocking it from the south. He then tried a ruse to lead the Japanese into believing that another infantry attack on the Triangle was imminent. To that end, the program of artillery and mortar fire executed the day before was repeated exactly. There were the same five-minute intervals of artillery fire and the same salvos of smoke from the mortars.

Company E dashed across the bridge at exactly the same time and in exactly the same way as the day before, and, as the first smoke shell went down, the men fixed bayonets as if to attack, and cheered loudly for two minutes. The Japanese had pulled out of their bunkers as usual and were in their trenches braced for the expected infantry charge. This time, however, there was no attack. Instead, the infantrymen held their positions and the artillery and mortars poured everything they had into the smoke enveloped track junction.18

General Eichelberger reported that evening that he was sure he had killed a large number of the enemy with his “phony attack of artillery and smoke followed by the fixing of bayonets and a cheer.” But he had to admit that despite all the artillery and mortar fire that had been laid down on the Japanese positions in the Triangle, and the heavy losses that had been sustained in trying to take it, “our attempts to get the road junction have all failed.”19 The failure to take the Triangle was no great setback since General Eichelberger had already decided upon a more promising axis of attack across Entrance Creek in the area north of the Coconut Grove and the Triangle.

The Crossing of Entrance Creek

Where to establish the initial bridgehead on the other side of the creek was the problem. After studying available maps, General Eichelberger concluded that the best place for it lay in a fringe of woods just off the northwest end of the gardens where there seemed to be better cover and less enemy fire than elsewhere. He therefore issued orders late on the night of 20–21 December that the bridgehead be established there the next day.20

Colonel Grose chose Companies I and K for the task and early the next morning began to make his dispositions for the crossing. He ordered Company L to move from its position below the island to the right of Company I, which was already deployed in the area immediately north of the Coconut Grove. Company K, which had previously been to the rear of Company I, was ordered to go in on Company L’s left and to extend along the west bank of the creek almost to its mouth. The move brought Company K directly across the creek from the prescribed bridgehead area and in position to cross.21

From the beginning it was recognized that Company K’s crossing would be more difficult than Company I’s. The swift tidal stream that had to be crossed was less than twenty-five yards wide in Company I’s sector, and the engineers had only that morning finished building a small footbridge there improvised from a few saplings and a captured enemy boat anchored in the center of the stream. In Company K’s sector, on the other hand, the creek was at least fifty yards wide at the point of crossing and seven or eight feet deep. Colonel Grose went down to Company K’s sector to look things over and did not like what he saw. Thinking that there was a possibility that Company K, crossing in Company I’s sector, might be

able to work its way under the bank to the bridgehead area and establish itself there, he telephoned General Eichelberger and asked for more time. In the heat of the moment, he apparently failed to make clear to the general the reason for his request. In any event, Grose recalls, Eichelberger was impatient of any suggestion for postponement. He refused to give him more time, and Grose at once called in Capt. Alfred E. Meyer, the Company K commander, and ordered him to proceed with the crossing.22

At 1600 that afternoon Meyer sent troops into the creek to see if it could be forded. Not only could they find no crossing, they were nearly “blown out of the water” by enemy fire from the other side of the stream. Greatly perturbed at being ordered to make what he considered a suicidal crossing, Meyer pleaded with Grose to let him cross over the bridge in Company I’s area. If that permission was impossible to grant, Meyer requested that he be allowed to cross at night with the aid of ropes, pontons, or whatever equipment was available. Colonel Grose, who had already asked for more time without being able to get it, told Meyer that he was to start crossing immediately even if the men had to swim across.23

Captain Meyer went back to his company and made several attempts to get men across in daylight, but the enemy fire from the other side of the creek proved too heavy. By nightfall the company finally located a heavy rope, and the attempts to cross were renewed.

Unbidden, 1st Lt. Edward M. Greene, Jr., picked up one end of the rope, and with several enlisted men started swimming for the opposite shore. Greene was killed almost instantly by enemy fire, and his body was swept away by the current. A few minutes later one of the enlisted men lost his hold on the rope and was swept away. One of the swimmers finally got the rope across the river, and the rest of the night was spent in getting the heavily weighted troops over in the face of the continuing enemy fire. By about 0200 forty-seven men were on the other side of the creek, and when daylight came the total was seventy-five. Company K suffered fifty-four casualties that night—six killed or drowned in the crossing, and eight killed and forty wounded in the fighting at the bridgehead area.

Early on the morning of 22 December, while Company K engaged the enemy frontally in the bridgehead area and Company M’s heavy weapons covered it with fire from the west bank, Company I, under Capt. Michael F. Ustruck, crossed on the footbridge. Finding, as Colonel Grose had surmised, that there was a safe and easy approach to the bridgehead under the bank, the company went into position on Company K’s right by 1235 without losing a man.24

Bodies of troops of Company K who had been drowned in the crossing on the night of 21–22 December were to be seen the next day bobbing in the stream,25 but the crossing

had been accomplished, and there was a strong bridgehead on the other side of the creek. It had been a difficult and frustrating operation. As General Eichelberger put it two days later, “When we put K Company across an unfordable stream in the dark against heavy fire the other night we did something that would be a Leavenworth nightmare.”26

The Subsidiary Operations

The Situation on the Left Flank

While these operations were progressing, there had been a flurry of activity on the left flank. On 18 and 19 December the Schwartz patrol had clashed with enemy patrols west of Siwori Village. On 20 December, upon the insistence of General Herring that the left flank be better secured, Schwartz was reinforced with another twenty men of the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, which was in reserve at the time below Buna Village. Schwartz’s force, now numbering thirty-five, began moving on its objective, Tarakena, a small village on the west bank of Konombi Creek, about a mile northwest of Siwori Village.

The men reached Tarakena early on 20 December, only to be thrown out of the place by a superior Japanese force. Col. Frank S. Bowen, Jr., G-3, Buna Force, immediately ordered forward another mixed unit of thirty-two men from the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry. Schwartz got the reinforcements late in the afternoon and moved on Tarakena at dusk with his sixty-seven men to stage, as he said, “a heckling party” for the enemy’s benefit.27

The patrol succeeded in retaking a corner of the village during the night, but the enemy, much stronger than had been anticipated, counterattacked and forced it back across the creek. The patrol suffered fifteen casualties during the encounter, including Schwartz who was wounded. Command of the patrol fell to 1st Lt. James R. Griffith. He was wounded the same afternoon, and 1st Lt. Louis A. Chagnon of Headquarters Company, 127th Infantry, took over, bringing with him members of Headquarters Company and the Service Company. Since he was obviously outnumbered, Chagnon took up a defensive position a few hundred yards southeast of Tarakena and awaited the enemy’s next move.28

The Capture of the Island

By 22 December the engineers, meeting no enemy interference, had repaired the south bridge between the mainland and the island. That afternoon, as soon as the bridge was down, a patrol of Company L, 127th Infantry, moved over it and crossed the island without opposition. As the men approached the north bridge between the island and the mission, they began receiving heavy fire. Two platoons of Company F

Footbridge over entrance creek to Musita Island

and a machine gun section of Company M, under Lt. Col. Benjamin R. Farrar, then serving as S-3 of the 127th Infantry, moved in to meet the situation. By 1115 the next morning, the last Japanese to be found on the island had been overcome, and Company F, its work done, pulled back to the mainland.

Company H thereupon moved onto the island, bringing with it, in addition to its heavy weapons, a 37-mm. gun “with plenty of canister.” A platoon of Company E, 127th Infantry, on the village spit (the small peninsula east of Buna Village) also had a 37-mm. gun firing canister. From their separate points of vantage the two units began bringing down close-in harassing fire on the mission and continued to do so day and night.29

Now that the island had fallen, General Eichelberger had a new axis of advance for an attack on the mission. All that remained was to get troops across the north bridge between the island and the mission and to establish a beachhead on the opposite shore. “Maybe I can get a toehold there,” General Eichelberger mused in a letter to General Sutherland. “It might prove easier,” he

added, “than where I now plan to go across.”30

The Corridor to the Coast

The Attack in the Gardens

On the evening of 23 December, with the bridgehead at the northwest end of Government Gardens firmly secured, General Eichelberger ordered Colonel Grose to attack in an easterly direction across the gardens the following morning. Grose had five companies of the 127th Infantry for the attack. The plan called for the 3rd Battalion rifle units to launch the attack, supported by the heavy weapons crews of Company M disposed along Entrance Creek to the rear of the line of departure, with some of the men in trees. Company G would be in reserve and would go into action upon orders from Colonel Grose.

There would be no direct air support because the troops were too close to the enemy. The artillery at Ango and Colonel McCreary’s massed mortars south of the island were to lay down a heavy preparation before the troops jumped off, and were to follow it with a rolling barrage when the advance got under way. The troops on the island and on the village spit would make a maximum effort to saturate the mission with fire, in order to deceive the enemy as to the direction of the attack and to prevent the reinforcement of his positions in the gardens.31

The troops on the island and on the village spit laid down heavy fire on the mission during the night, as did the 25-pounders and the 105-mm. howitzer at Ango. The Japanese, in turn, kept the bridgehead under continual harassment, using mountain guns, heavy mortars, and antiaircraft guns depressed for flat-trajectory fire. All along the line of departure the companies remained on the alert throughout the night, but the Japanese made no move either to counterattack or to infiltrate the American lines.

At dawn of 24 December Company G crossed the creek, and the heavy weapons crew of Company M took up supporting positions along the bank of the stream. Company L replaced Company I on the left, Company I extended to the right, and Company K, shaken by its experience of the night before, went into reserve. Shortly thereafter, the two assault companies, I and L, each reinforced by weapons crews of Company M, moved into position along the line of departure. At 0600 the artillery and mortars began firing their preparation, and Company H on the island opened up on the mission with all its weapons. Covered by the rolling barrage, the troops jumped off fifteen minutes later on a 400-yard front.32

The drive across the gardens to the sea had about 800 yards to go. Neglected and overgrown with thick clumps of shoulder-high kunai grass, the gardens extended for some 400 yards to a swamp about 100 yards wide. On the other side of the swamp, looking out on the sea, was a coconut plantation, about 300 yards across, through which ran

the coastal track between Buna Mission and Giropa Point.

Captain Yasuda had the area well prepared for defense and could cover nearly every foot of it with both observed and unobserved fire. The track through the gardens was covered by bunkers, and on either side of it, echeloned in depth to the rear and hidden by the kunai grass, were numerous individual foxholes and firing pits, most of them with overhead cover. In the surrounding swamp, north and east of the gardens, were strong bunker positions, and even stronger fortifications were to be found in the plantation and along the shore.33

For an attacking force, the gardens would have presented great difficulties even had there been no bunkers. One who was there recalls the situation in these words:

There was very little cover on the eastward side of Entrance Creek which forced troops to be heavily bunched during the staging period of an attack. The gardens themselves were very flat, covered by a substantial growth of Kunai grass, and accordingly provided excellent cover for the Japanese as well as a good field of fire. The surrounding swamp areas were infested with snipers in trees. All of which made operations across the Government Gardens a very difficult maneuver.34

As the two companies left the line of departure and began moving through the kunai grass they were met by heavy fire and both were held up. The fire was particularly heavy on Company I’s front. The company cleaned out an isolated enemy bunker just forward of the line of departure, but its attempts to infiltrate and knock out a main Japanese strong point immediately to the rear met with no success whatever. Making full use of the many hidden positions at their disposal, the Japanese successfully countered the unit’s every attempt to move forward.35

The fighting was bitter and at close quarters. While the company was pinned down in front of the strongpoint, its 1st sergeant, Elmer J. Burr, saw an enemy grenade strike close to Captain Ustruck, who was out in front with his men. The sergeant threw himself on the grenade and smothered the explosion with his body. Burr was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor—the first man to receive the award during the campaign.36

Though Colonel Grose had a temporary forward CP close to the line of departure—so close in fact that Colonel Farrar was wounded that morning by small arms fire while in the CP area—he could not see why Company I was not moving forward. Maj. Harold M. Hootman, the regimental S-4, who was in the CP with him, asked permission to go to Company I and try to find out what was happening. Grose recalls that he was “a bit flabbergasted” at the request, “because it seemed to be the desire of so many to find a good reason for going to the rear,” but he gave Hootman permission to go and asked him to report his findings to him when he got back. That was the last time he saw the man alive. Hootman’s body

Japanese-built bridge to Buna Mission over Entrance Creek

was later recovered, rifle in hand, not far from a Japanese bunker under circumstances which suggested that he fell while trying to take it singlehanded.37

Hootman had scarcely left the CP when news came back that Company I had suffered heavy casualties and become disorganized. Colonel Grose finally went out to the company himself and what he saw confirmed the news. He ordered the unit to the rear to reorganize and, at 0950, sent in Company G in its place. Within the hour, Company G reported that the enemy had been cleared out of a three-bunker strongpoint which had previously held up the advance. Despite this promising start, Company G did not get much farther that day. Setting up his command post in the most forward of the captured bunkers, the company commander, Capt. William H. Dames, continued with the task of rooting the enemy out of his remaining bunker positions. Under an unusually aggressive commander, the fresh company cut through to the track and straddled it but, try as it

would, could not move forward immediately because of the intense fire from the enemy’s hidden bunker positions.38

The real disappointment of the day, however, came on the far left, where Company L was to have made the main penetration. Under 1st Lt. Marcelles P. Fahres, Captain Wentland’s successor, Company L was given all the aid that was available. The automatic weapons of Company M along Entrance Creek fired heavily in its support, as did the massed 81-mm. mortars south of the island, first under Colonel McCreary, and when McCreary was wounded that day, under Col. Horace Harding, General Eichelberger’s artillery officer who was acting as division artillery commander. Nevertheless, the company, after making small initial gains, did not move forward.39

Aware of the situation, Colonel Grose at 1028 ordered a platoon of twenty men from Company A to cross over to the mission from the island by way of the north bridge and hold there as long as possible. The Japanese were so busy in the gardens that the troops actually got across the bridge, which though rickety was still standing. Unopposed at first, the platoon was soon set upon by the Japanese, who killed eight of its members and forced the rest back across the bridge.40

The diversion appears to have succeeded better than was at first realized. Captain Yasuda’s troops by this time were spread thin, and he was apparently forced to transfer troops from the strongpoint at the northwest end of the gardens to the mission in order to meet the new threat there. Feeling the pressure upon it ease, Company L’s left platoon, under 2nd Lts. Fred W. Matz and Charles A. Middendorf, began pushing ahead. Meeting little opposition, the platoon started racing forward alone through the tall grass, unnoticed by the rest of the company. The company commander did not see the men go and did not miss them until some time later. Within a short while, the platoon was through the gardens and on the outskirts of the Coconut Plantation. There the men ran into two well-manned enemy

bunkers which stood directly in the way of their advance. Sgt. Kenneth E. Gruennert, in the lead, undertook to knock them out. Covered by fire from the rest of the platoon, he crawled forward alone against the first bunker and killed everyone in it by throwing grenades through one of its firing slits. Although severely wounded in the shoulder while doing so, Gruennert refused to return to the rear. He bandaged the wound himself and moved out against the second bunker. Hurling his grenades with great precision despite his bad shoulder, Gruennert forced the enemy out of the second bunker as well but was himself shot down by an enemy sniper. Gruennert was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor—the second to be conferred on a 127th Infantry soldier for the day’s action.41

Completely out of touch with its company and the rest of Urbana Force the platoon consolidated and pushed on. By noon it was within sight of the sea, and there its troubles really began. The Japanese started closing in, and the artillery at Ango, unaware that friendly troops were so far forward, shelled the area with great thoroughness, killing Lieutenant Middendorf and wounding Lieutenant Matz slightly.

One of the eight men left with Matz was badly wounded and unable to march. The lieutenant decided to stay with him and ordered the rest of the troops to withdraw. They got back safely to their own lines two days later after a difficult march, most of it through hip-deep swamp. Matz and the enlisted man, who would have died had the lieutenant not stayed with him, remained hidden behind the enemy lines until Urbana Force overran the area eight days later.42

Colonel Grose did not learn of the platoon’s break-through until just before noon when a runner got back with the news. He at once ordered Company I back into the line to the right of Company G and sent Company K to the far left with orders to go to the platoon’s assistance. The company attacked in the direction it was believed the platoon had followed. Captain Yasuda had meanwhile plugged the hole in his defenses, and it was only after heavy fighting that 1st Lt. Paul M. Krasne and eight men of the company finally broke through. They raced to the beach, found no trace of the Matz patrol, and promptly withdrew lest they be cut off.

Seeing that the line did not move, Colonel Grose ordered Company F to attack on Company L’s right at 1511. The result was the same. The line remained where it was and by evening was no more than 150 yards from the line of departure.43

Colonel Grose asked General Eichelberger for time to reorganize but the request was refused, and he was ordered

instead to resume the attack early Christmas morning. Eichelberger, who had been at the front all day, taking an active part in the conduct of operations, reported the refusal to General MacArthur the next day, adding in words charged with emotion, that seeing the attack fail had been the “all time low” of his life.44

The Attack on Christmas Day

Colonel Grose now had eight companies of the 127th Infantry at the front—A, C, F, G, I, K, L, and M. His plan was to have Companies A and F attack on the far left and push through to the coast. Companies K and L, in the center of the line, would push forward in their sector in concert with the companies on the left. Companies I and G would concentrate on reducing the bunkers that covered the trail through the gardens and would be aided in that endeavor by a diversionary attack in the afternoon on the Japanese positions in the Triangle. Company C would be in reserve.

Companies A and F were to launch their attack on the far left without mortar or artillery preparation of any kind. Instead, there would first be the pretense of a full scale attack on the mission from the island, in the hope that the enemy would weaken his dispositions in the gardens in order to meet the new threat. As soon as it became evident that the enemy had swallowed the bait, Companies A and F would suddenly attack in the gardens. It was hoped that the enemy would be taken completely by surprise by this maneuver.45

On Christmas morning, the mortars and artillery in a thunderous barrage gave the mission a thorough working over, and Company H, on the island, made a great show of being about to attack the mission across the north bridge, a makeshift structure that miraculously still stood. At 1135, while the commotion on the island was at its height, Companies A and F attacked across the gardens without preparation of any kind. The ruse worked. Company A (less two platoons which had not yet arrived) was held up, but Company F, which had found it impossible to move forward the day before, found the going relatively easy. Led by Capt. Byron B. Bradford, the company cut its way through the gardens and the swamp and reached the Coconut Plantation by 1345. Obviously caught off base, the Japanese rallied, surrounded the company, and began a counterattack. After beating off the attack with very heavy losses to itself, the company established an all-around perimeter in a triangular cluster of shell holes just outside the plantation. The position was about 200 yards west of the track junction, about 250 from the sea, and 600 from the mission.

An advance detachment of Company A, under its commanding officer, Capt. Horace N. Harger, broke through to F’s position at 1620, but its weapons platoon was ambushed and destroyed by the enemy just as it was on the point of going through. The rest of Company A reached the front late in the afternoon but was unable to get through. As night fell, its leading elements and those of Companies K and L were at least 350

yards from the beleaguered companies near the coast.46

The diversionary attack on the enemy bunker positions in the Triangle to help Companies G and I on the right was mounted late in the afternoon. A platoon of Company E was to advance into the mouth of the Triangle and engage the enemy with fire while a platoon of Company C, with the support of heavy weapons crews of Company D, launched the main effort from the south. Although the attack, led by Capt. James W. Workman, commanding officer of Company C, was carefully planned and prepared, it failed, as had all previous efforts to take this position. The attack was finally called off toward evening after Captain Workman was killed while charging an enemy bunker at the head of his troops.47

For all its cost, the diversion had done little to ease the pressure on Companies G and I. After fighting hard all day, the two units had made only slight gains. The enemy bunkers were too well defended and too cleverly concealed. Captain Dames and Lieutenant Fahres tried digging saps toward them, but at the end of the day, the enemy bunkers still stood, seemingly as impregnable as ever.48

Urbana Force had not been able to make contact with Companies A and F since morning because their radios were wet and would not work. Three men of Headquarters Company, 127th Infantry—Pvt. Gordon W. Eoff, Pfc. William Balza, and Sgt. William Fale—distinguished themselves while attempting to get telephone wire forward, but all efforts to regain communications with the two companies that day failed.49

Establishing the Corridor

Late in the afternoon Colonel Grose redisposed his command, in accordance with his practice of rotating “the units so that they could get out of the lines and have a few days’ rest.” Pulling Companies I and K out of the line, he ordered Company C (less one platoon, which was holding the area below the Triangle) in on the far left. Company I returned to the other side of the creek, Company K went into reserve, and Company L, extending itself to the right, tied in on Company G’s left.50

Company C’s instructions for 26 December were to break through to the companies near the coast, and link up with them to form a corridor from Entrance Creek to the sea. Maj. Edmund R. Schroeder, commander of the 1st Battalion, who reported to Colonel Grose that evening, would take personal charge of the attack.51

Things went somewhat better on the 26th. Assisted by Company I, Company G knocked out several bunkers on the right along the trail during the morning and began working on those that remained. On the far left, however, the enemy was still resisting stubbornly, and Company C made no progress all morning.

The Japanese were obviously reinforcing their positions north of the gardens directly from the mission. To discourage this activity, the artillery put down a ten-minute concentration on the southwest corner of the mission at noon that day. Major Schroeder ordered an element of Company C, split into patrols, into the swamp north of the gardens to deal with the Japanese there. The rest of the company, joined during the afternoon by Company B, commanded by 1st Lt. John B. Lewis, continued to attack frontally.52

The attack made little progress, and it became apparent during the early afternoon that Company C was not going to break through. Colonel Grose ordered Colonel Bradley, now chief of staff of the 32nd Division, to go to the beleaguered companies and bring back a report on their condition. Bradley, who at Grose’s request was also acting as executive officer of the 127th Infantry, was to be accompanied by Major Schroeder, 1st Lt. Robert P. McCampbell, S-2 of the 2nd Battalion, and a platoon of Company C, led by 1st Lt. Ted C. Johnson. The patrol set out at once, carrying with it wire, ammunition, and food. After some sharp skirmishing with the enemy the patrol reached its destination at 1745 that afternoon.53

The two companies were in very bad condition when the patrol reached them. Major McCampbell, or Lieutenant McCampbell as he then was, recalls the matter in these words:–

The condition of the companies on our arrival was deplorable. The dead had not been buried. Wounded, bunched together, had been given only a modicum of care, and the troops were demoralized. Major Schroeder did a wonderful job of reorganizing the position and helping the wounded. The dead were covered with earth ... the entire tactical position of the companies were reorganized and [they were] placed in a strong defensive position. ...54

That evening Colonel Bradley, accompanied by a small patrol, returned from the perimeter with a complete report. Major Schroeder and Lieutenant McCampbell

remained behind to continue with the reorganization of the troops.55

The attack was resumed early on 27 December, with Colonel Bradley, on Colonel Grose’s orders, in command of Companies B and C and the detachment of Company A. Company C and the detachment of Captain Harger’s company were held up by the bunkers north of the gardens, but Company B on their right made good progress all day. A grass fire set in the gardens by the enemy during the afternoon caused only slight interruption in its advance. By 1700 Lieutenant Lewis had moved through to Schroeder’s position with his entire company.56

By the morning of 28 December Major Schroeder had the forward perimeter well organized for action. The telephone was operating without interruption, ammunition and food were going through, the walking wounded had been successfully evacuated to the rear, and the troops were being organized for attack.57

Early that morning Colonel Grose ordered Company L out of the line to rest and clean up. He expected the break-through to the beleaguered companies to come momentarily. This expectation was quickly realized. Just before noon Company C on the left and Company G on the right broke through to the position held by Companies F and B and the detachment of Company A. The rest of Company A moved in soon after and the result was a broad corridor from Entrance Creek to the Coconut Plantation. Major Schroeder reported the establishment of the corridor the minute Companies C and G got through and, with a flourish characteristic of the man, asked Colonel Grose over the telephone, “Do you need any help in the rear areas?”58

It was obvious that the Japanese could not hope to hold the Triangle once they lost control of the gardens for the position was now outflanked and cut off. No one knew this better than the Japanese commander, Captain Yasuda, who had apparently lost no time in ordering it evacuated. When a volunteer party of Company E, 127th Infantry, led by Sgt. Charles E. Wagner, with Pfc. James G. Greene as his second-in-command, pushed its way cautiously into the Triangle that evening, it found that the Japanese had pulled out of the area some time before and that the fourteen bunkers

General Eichelberger and members of his staff look over newly taken ground in the Triangle area

and innumerable trenches making up the position were empty.59

There was every indication that the Japanese had left their positions in the Triangle in a great hurry. Pieces of equipment and quantities of small arms ammunition were strewn about in the bunkers and fire trenches, and two 20-mm., gas operated, cart-mounted antiaircraft guns, together with large quantities of antiaircraft ammunition, had been left behind. The entire area was pockmarked with shell holes, and there was mute evidence that some of the enemy had not long ago been caught in the open by Allied artillery fire.60

In evacuating the Triangle the Japanese had given up an immensely strong position that Urbana Force, despite many costly attempts, had found it impossible to take. Going over the ground a day later, General Eichelberger reported to General Sutherland: “I walked along there and found it terrifically strong. It is a mass of bunkers and

entrenchments surrounded by swamp. It is easy to see how they held us off so long.”61

By the evening of the 28th Urbana Force was able to use the trail through the gardens as far as the Coconut Grove and also controlled the track junction along the coast. Major Schroeder’s force was deep in the Coconut Plantation, and Company B, its forward element, was only 120 yards from the sea.62 The corridor from Entrance Creek to the coast had finally been established. Split off from Giropa Point, the mission now lay open to assault.