Chapter 16: The Fall of Buna

With Warren Force poised to attack Giropa Point, and Urbana Force moving to envelop Buna Mission along the newly established corridor from Entrance Creek to the coast, the reduction of the enemy positions on the Buna side of the Girua River was finally at hand. This was to be no easy task. The enemy at Buna was heavily outnumbered and almost completely surrounded, but he was fighting with the utmost ferocity and was to be cleared out of his remaining positions at Buna only after some of the bitterest fighting of the campaign.

The Advance to Giropa Point

The Abortive Attack of 29 December

Warren Force had completed the reduction of the Old Strip on the 28th. Just before midnight of the same day the 2/12 Battalion, thirty officers and 570 other ranks under Lt. Col. A. S. W. Arnold, reached Oro Bay from Goodenough Island by corvette. The battalion and its gear were landed safely during the night, and the troops who were to begin moving forward to the front the next day went into bivouac in the brigade area near Boreo.1

Brigadier Wootten devoted the next morning to regrouping and reorganization. Company A, 2/10 Battalion, moved to the left flank and took up a position on the right of Company C, 2/10 Battalion, which continued on the far left as the main assault company. Companies B and D, 2/10 Battalion, continued as before on the far right, with D on the outside and B on D’s left flank. Companies C and A, 128th Infantry, and Company C, 126th Infantry, with Company A, 126th Infantry, in support, were in the center of the line. Company B, 126th Infantry, Company B, 128th Infantry, and a composite company of the 2/9 Battalion were in reserve. Four tanks in position at the bridge between the strips were ready to go, and seven others, which had just reached Boreo from Oro Bay, were in reserve, as was the 2/12 Battalion, which began moving to the front that morning.2

At 1235 Wootten gave verbal orders for an attack on the area between Giropa Point and the mouth of Simemi Creek. The attack, which was to be in a northeasterly direction toward the coast, was to be mounted after 1400 with the four available tanks. Company C, 2/10 Battalion, was to follow the tanks and in general make the main

effort, but the companies on its right were to take advantage of every opportunity to advance provided they did not unnecessarily expose their flanks.3

Colonel Dobbs fixed zero hour at 1600. The tanks were delayed, and the attack did not get under way until 1715, following an artillery preparation with smoke. In an effort apparently to make up for lost time, the tanks moved at high speed and came in obliquely across the line of departure. Without waiting for the slower-moving infantry to close in behind them, they moved north without moderating their speed. The infantry as a result had to attack independently of the tanks, and the tanks, far in front of the infantry, had to move on the enemy bunkers without infantry support.

As the tanks hit the first line of bunkers, the Japanese, with no Allied infantry at hand to stop them, pulled back to their second bunker line. When the tanks finally discovered what had happened and began working on the second line, the Japanese filtered back into the first line, in plenty of time to stop the foot soldiers who had meanwhile managed to fight their way into the grove. At 1845 the attack had to be called off. The tanks by that time had expended all their ammunition, and the infantrymen were met by such intense fire from hidden enemy bunker positions that they had to pull back to the edge of the Coconut Plantation and consolidate.4

The 2/12 Battalion is Committed

The fresh 2/12 Battalion reached the front that night, 29 December. Early the following morning Brigadier Wootten ordered it to take over on the left in place of the 2/10 Battalion, which had seen a great deal of action and needed rest. The day was devoted to regrouping and reorganization. Colonel Arnold went forward to reconnoiter the front his battalion was to take over. Major Beaver’s 126th Infantry troops, who were also in need of rest, exchanged places with Colonel MacNab’s battalion, the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, which after a week of rest in the Cape Endaiadere area was again ready to attack.

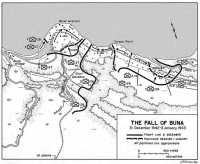

The redisposition of the troops was completed next day. By evening of 31 December the battalions were in place: the 2/12 Battalion on the left, the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry in the center, and the 2/10 Battalion on the right. The 2/12 Battalion and the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, were on an 1,100-yard east-west front and faced the coast. The 2/10 Battalion, with a holding mission, was drawn up across the head of the strip on a 500-yard front at right angles to them, its left tied in on the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, and its right on Simemi Creek. Major Clarkson’s 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, was on the 2/12 Battalion’s left rear; Company A, 2/9 Battalion, was in reserve.5 (Map 15)

Map 15: The Fall of Buna 31 December 1942–2 January 1943

At 1535 Brigadier Wootten issued a carefully drawn plan for the reduction the next day of Giropa Point and the area between it and the Old Strip. The attack would be supported by the mortars of the 2/10 Battalion, the 25-pounders of the Manning and Hall Troops, and the 4.5-inch howitzers of the Stokes Troop. Of the eleven tanks of X Squadron, 2/6 Armored Regiment, nine would be committed to the attack: six immediately, and the remaining three as they were needed.

The operation was to be in two phases. In Phase One the 2/12 Battalion and the tanks, with the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, as left-flank guard, were to attack in a northeasterly direction, break through to the coast, and turn southeast, thereby completing the enemy’s encirclement. In Phase Two, the 2/12 Battalion was to herd the encircled Japanese toward the companies advancing on the right and, with their help, destroy them.6

That night, while the troops snatched what rest they could before the next day’s attack, the K.P.M. ship Bath and the

Australian freighter Comara came into Oro Bay with 350 and 500 tons of cargo, respectively, unloaded, and departed before daybreak. The arrival of the Bath and the Comara marked a logistical milestone in the campaign. Since the night of 11–12 December, when the Karsik made the first pioneering trip to Oro Bay, six freighters making nine individual trips had brought in roughly 4,000 tons of cargo. This was more than three times the 1,252 tons that the Air Force had flown in to the 32nd Division during the same period, and 1,550 more than the 2,450 tons that it was to fly in for the 32nd Division’s use during the entire period that the division was in combat. Between the freighters and the luggers, an average of 200 tons of cargo was now coming into Oro Bay daily and had been since 20 December.7 Supply at Buna, in short, had ceased to be a problem just as the fight for the place was coming to an end.

The Attack on New Year’s Day

After a heavy artillery and mortar preparation, the troops on the right and left moved out for the attack at 0800, New Year’s Day. On the left, Companies A and D, 2/12 Battalion, and the six tanks cut northeast through the plantation toward the coast. The 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, followed them. Facing north, Companies I, K, and L, 128th Infantry, moved on the dispersal bays off the northwest end from below (south), and the 2/10 Battalion, facing west, remained in position on the Old Strip.

Without tanks to support it, the attack by the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, went slowly. The Japanese in the dispersal bays were well entrenched and fighting hard. On the left, the attack made excellent progress from the start. Closely followed by the infantry, the tanks made short work of the enemy defenses in the Giropa Plantation. The leading tank reached the coastal track below Giropa Point at 0830. A half-hour later all the tanks and most of the infantry had reached the coast. The 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, moved forward, mopping up pockets of enemy resistance that the Australians had overlooked or bypassed. Company A, 2/12 Battalion, with Company D immediately behind it, anchored its left flank on Giropa Creek, just west of Giropa Point, and began to consolidate on a 400-yard front along the shore. Companies B and C, 2/12 Battalion, which had been operating to the rear of Companies A and D, began moving eastward and southeastward with the tanks to complete the second phase of the attack.

Against the stiffest kind of opposition, the tanks and the Australian infantry following them moved steadily forward. By evening Companies C and D had cleared out the beach as far as the mouth of Simemi Creek. The 2/12 Battalion lost 62 killed, 128 wounded, and one missing in the day’s fighting, but the Japanese on the Warren front were finished. All that remained was to deliver the coup de grâce.8

Firing a 60-mm. mortar into the enemy lines at Buna Mission

The Australians had pressed into use that day for the first time a blast bomb of their own invention consisting essentially of a Mills bomb screwed into a two-pound can of ammonal explosive. As Colonel MacNab recalls, it was used in the following manner: “A tank would knock a corner off the enemy bunker, and while this hole was ‘buttoned up’ by automatic or rifle fire, a volunteer would creep up to the side of the bunker, heave in the bomb, and duck. The explosion would rock the bunker and stupefy the Japanese inside. Then a can of Jap aviation gasoline would be tossed in, ignited by tracers, and the bunker would be burned out.”9

The end came the next morning. Major Clarkson’s 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, finished clearing out the last pocket of enemy resistance on the left; details of the 2/9 and 2/10 Battalions finally cleaned out the enemy emplacements on the island at the mouth of Simemi Creek; and Companies C and B, 2/12 Battalion, the 3rd Battalion,

128th Infantry, and eight tanks attacked the Japanese in the dispersal bays. The 2/10 Battalion, with Allied fire coming in its direction, stayed down out of harm’s way.10

The attacks by Colonel Arnold and Colonel MacNab, the one attacking from the west and the other from the south, were soon over. As the fire slackened, the officers and men of the 2/10 Battalion rose out of their holes in the Old Strip area and watched the last Japanese positions being overrun.11

This was the last organized attack delivered by Warren Force. After taking Giropa Point and the area immediately to the eastward, the troops had little left to do but mop up. Orders were issued that day to the 2/12 Battalion and the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, to begin moving westward toward Buna Mission in the morning. The orders were revoked a few hours later, when it was found that contact had been made with Urbana Force, and that that force was already proceeding with the envelopment of Buna Mission.12

The Capture of Buna Mission

The Failure To Cross the North Bridge

At 1330, 28 December, while Urbana Force was tidying up its corridor from Entrance Creek to the coast and preparing to move forward to the sea, General Eichelberger, accompanied by General Sutherland, Colonel Bowen, Colonel Rogers, and Colonel Harding, arrived at Colonel Grose’s CP from Buna Force headquarters. Asked for a report on the situation, Grose gave Eichelberger a resume of how things stood. Among other things, Grose told Eichelberger that he had just taken the 3rd Battalion out of the line for a much-needed rest. At 1428, without discussing the matter further with Grose, Eichelberger ordered that the 3rd Battalion, split into two elements, launch an immediate attack on Buna Mission. One element was to advance on the mission from the island by way of the north bridge; the other element, starting from the southern side of the island, was to move upon it in five Australian assault boats which had reached the front the day before.

Eichelberger and Grose had discussed this plan and several others some days before, but had never worked out the details. Grose recalls that he was so startled by the sudden order to commit the tired battalion to such an attack that it took him a few

minutes to organize the maneuvers in his mind.13

Aside from the weariness of his troops, there was another even greater difficulty. The enemy had a line of bunkers just off the northern end of the bridge, and the bridge itself, a narrow, makeshift structure forty feet long and a couple of feet wide, had a fifteen-foot gap at its northern end—the result of a recent Allied artillery hit.14

As soon as I had my thoughts collected [Grose recalls], I called for volunteers among the officers present to do certain things. Colonel Bowen volunteered to get the engineers and collect the necessary timbers to fix the bridge, Colonel Rogers to reconnoiter the position on the island and see that the troops were conducted thereto, and Colonel Harding to coordinate and control the mortar and artillery fire. I ordered Captain Stephen Hewitt, my S-2, to make the reconnaissance of the route the boats were to take ... and Captain Leonard E. Garret, my S-3, to arrange for and coordinate the fires of Company H from the island and the troops on the finger, both of which were to fire on the mission preceding the attack.15

Colonel Grose quickly worked out the details of the plan. The attack was to open with fifteen minutes of artillery and mortar fire on the mission and the bunkers facing the bridge. Guided by directions given them by Captain Hewitt as a result of his reconnaissance, forty men of Company K in the five assault boats were to round the eastern end of the island just as the preparatory fire began lifting. They were to land east of the bridge and establish a bridgehead. Supported by fire from Company H on the island and from a platoon of Company E at the tip of the village finger, they were to engage the enemy with fire, thereby masking the bridge and permitting the planks required to make it usable to be laid in safety. As soon as the planks were down, the rest of Company K would dash across the bridge in single file, and would be followed by Company I and Company L, in that order. When all three companies were across, they would attack north in concert with Major Schroeder’s force on the coast, which would attack from the southeast.16

The preliminary tasks were completed in short order. Captain Hewitt, who had gone out in one of the assault boats, returned with the results of his reconnaissance. Six enlisted men volunteered to lay in place the three heavy timbers that would span the gap at the northern end of the bridge. Commanding the assault boats, 1st Lt. Clarence Riggs of the 3rd Battalion’s Ammunition and Pioneer Platoon quickly moved them into position in some heavy foliage off the southern side of the island. The rest of the 3rd Battalion, guided by Colonel Rogers, began moving forward to the bridge area from the center of the island. Having been told only a little while before that they were to be given a rest, the troops of the battalion were slow in moving forward, and Colonel Rogers was unable to get them into position south of the bridge until the first salvo of the artillery preparation hit the mission.

The time was 1720. As the first artillery salvo went down, the boats pushed off from

their hidden position. The troops had been misdirected by Captain Hewitt, however. Instead of going around the island and landing on the east side of Entrance Creek, they tried to land on the mission finger. The platoon of Company E on the village finger mistook them for the enemy and opened fire on them, as did the Japanese. Lieutenant Riggs’ boat, in the lead, swamped and sank. Although Riggs could not swim, he somehow reached shore and managed to stop the firing from the village finger, but it was too late: most of the boats had already been sunk in the shallows. Fortunately no one was killed or drowned.17

Things had also miscarried at the bridge. The six men to volunteer—Pvts. Arthur Melanson and Earl Mittelberger, T/5’s Charles H. Gray and Bart McDonough of Company A, 114th Engineer Battalion, and Pvts. Elmer R. Hangarten and Edward G. Squires of Company H—had advanced across the bridge, two men to a timber. Amid heavy fire from the opposite shore, they dropped the three timbers in place, and all except Mittelberger, who was killed on the bridge, lived to tell the tale. As soon as the timbers were in place, Company K started crossing. Scarcely had the first two men reached the northern end of the bridge, when the newly laid planks fell into the stream because of the weakness of the pilings at the other end of the bridge. The two men, one of them wounded and neither able to swim, hid under the bank on the other side of the stream, only their heads showing. They were rescued the following night by 1st Lt. William H. Bragg, Jr., commanding officer of the mortar platoon of Company H, and three enlisted men of the company, who swam across the creek to save them.18

The New Plan

On the night of 28–29 December ammunition and pioneer troops of the 127th Infantry finished digging a 2½-foot-deep trench across the northwest end of the gardens. The trench, which they had begun the night before, was the idea of Capt. W. A. Larson, Major Hootman’s successor as regimental S-4. Early on 29 December it went into use as a route by which supplies were brought forward and the wounded were carried back. It was an immediate success and proved as useful in the transfer of troops as in evacuation and supply.19

Later the same morning the original Urbana Force—the 2nd Battalion, 126th

Infantry, and the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry—went back into the line. The 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, less the troops at Tarakena and Siwori Village, took up a holding position at the southeast end of the Government Gardens, and the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, moved into the Triangle to take over its defense. Just after the two battalions began moving forward from their rest areas, Company B, 127th Infantry, from its position along the coast southeast of the mission, pushed forward to the sea and established a 200-foot frontage along the shore.20

Major Schroeder’s line now extended from Entrance Creek to the sea, but the troops on the island were still held up by fire from the northern end of the bridge. An apparent solution to the problem was found that night. Just before midnight a patrol of Company H, 127th Infantry, under 1st Lt. Allan W. Simms, waded across from the village sandspit to the spit projecting from the mission. The patrol remained on the mission side of the creek for half an hour, without receiving any fire or finding any Japanese in the area. On the basis of this evidence of enemy weakness, a new plan to envelop the mission was drawn on 30 December.

Under the new plan, Company E, 127th Infantry, and Company F, 128th Infantry, the 127th Infantry troops leading, would cross the shallows between the village and the mission. Company E was to tum right and establish a bridgehead. Company F crossing behind it would move northeast along the coast directly on the mission as soon as Company E had knocked out the bunkers and the bridge was repaired. Company H, 127th Infantry, and Company G, 128th Infantry, would cross over from the island, tie in on Company F’s right along the coast, and attack. Major Schroeder’s 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, reinforced by elements of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, would meanwhile be moving on the mission from the southeast. The result would be a double envelopment of the mission with separate columns converging upon it simultaneously from the front and from both flanks. This final, multi-pronged attack was to open at dawn the following morning, 31 December.21

The Attack of 31 December

Preparations for the attacks from the village spit were completed in good time on the 30th. Early in the morning, while Company G, 127th Infantry, under Captain Dames, moved into the Coconut Grove for a well-earned rest, Company F, 128th Infantry, under Capt. Jefferson R. Cronk, went into bivouac at Buna Village, and was joined there by Company E, 127th Infantry (less the platoon on the finger). Company E, low in morale after its heavy losses in the Triangle, was under the command of Lieutenant Bragg of Company H, who had volunteered to lead it in the attack across the shallows.22

Major Schroeder had meanwhile been attacking toward the mission. The Japanese were still holding strongly along the coast, and he made little progress. There was no cause for concern, however, for Schroeder’s position was secure. Facing Buna Mission,

the line was held by Companies F, A, K, and L. Elements of Company M and Company B in platoon strength were in place in the gardens on both sides of the corridor; Companies C and I were in the center of the corridor; Company D was to the east of it facing Giropa Point.23 It was clear that the enemy for all his tenacity would not be able to hold on the coast when the attacks from the village and the island got under way.

At 0430 the following morning, while it was still dark, Company E, 127th Infantry, and Company F, 128th Infantry, started moving in single file across the shallows between the finger and the mission. Company E was in the lead, with Lieutenant Bragg at the head of the column. The plan was to launch a surprise attack on the enemy positions opposite the bridge at daybreak. The men were under orders to make as little noise as possible and had been warned not to fire their weapons until told to do so. Company E gained the spit on the mission side without alerting the enemy, turned right, and began to move inland. Just as the leading elements of the company reached the spit, some of the men to the rear, unable to resist the temptation, threw grenades into a couple of landing barges that were stranded on the beach. At once the whole area broke into an uproar, the beach lit up with flares, and the troops were assailed with hand grenades, rifle grenades, and automatic weapons.24

The Japanese reaction threw the troops into a panic. Their plight became even worse when Lieutenant Bragg, who in General Eichelberger’s words was to have been “the spark plug of the whole affair,” was shot in the legs during the first few moments of the firing and, in the confusion of the moment, was reported missing.25

Colonel Grose waited on the village spit to hear news of the attack. He had a man with sound-powered telephone and a roll of wire following the action and reporting on its progress. The first information Grose heard on the phone was that the lieutenant who had taken command when Bragg fell was “running to the rear,” and that there were others with him.

I told the man [Colonel Grose recalls] to stop them and send them back. He replied that he couldn’t because they were already past him. Then the man said, ‘The whole company is following them.’ So I placed myself on the trail over which I knew they would have to come, and, pistol in hand, I stopped the lieutenant and all those following him. I directed the lieutenant to return and he said he couldn’t. I then asked him if he knew what that meant and he said he did. The first sergeant was wounded, and I therefore let him proceed to the dressing station. I designated a sergeant nearby to take the men back and he did so. I then sent the lieutenant to the rear in arrest and under guard.26

Although Company E, in its flight, passed through Company F, 128th Infantry, which had been moving forward immediately to its rear, Captain Cronk’s company was not affected by Company E’s disorganization. Cronk himself, Colonel Grose recalls, was as calm and collected as if he were on the drill

field. The 128th Infantry troops moved forward steadily and, by the time they were finally joined by Company E, had established a strong position on the spit and were holding their own. On Colonel Grose’s orders Captain Cronk took command of Company E, and the two companies began attacking toward the bunkers in the area north of the bridge. They met stiff resistance, and, in a full day’s fighting, Cronk could report only a small advance, though he hoped to do better the next day.27

The steadiness under fire of Captain Cronk’s company had saved the day. General Eichelberger finally had his long-sought toe hold on the mission, and Captain Yasuda’s troops, under attack for the first time from two directions, faced annihilation.

Yasuda had received some rations and ammunition by submarine on the night of the 25th and continued to fight stoutly for the mission with his remaining troops.28 The fighting was particularly bitter along the coast southeast of the mission and in the swamp north of the gardens, where elements of Company C were still busy cleaning out pockets of enemy resistance. Although Companies E, F, and H, 126th Infantry, under Captain Sullivan, advanced 300 yards in the area east of the right fork of the Triangle, thus completing the capture of the gardens, the day’s gains along the coast and in the swamp north of the gardens were disappointing.29

The enemy was resisting fanatically, but he was obviously nearing the end of his powers. For several days artillery overs from the Warren front had been troubling the troops on the Urbana front, and the troops on the Warren front were, in turn, receiving fire that could have come only from Urbana Force. Not only were the two forces moving closer together, but a patrol of the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, had made contact that morning with a patrol of Warren Force at the southwest end of the gardens.30

Since Warren Force was to mount its final attack on Giropa Point in the morning, Company B, 127th Infantry, was ordered to attack eastward the next day to link up with Warren Force and assist it in the cleanup. General Eichelberger wrote to General Sutherland that night that he hoped the attack would “go through in fine shape.” “If it did,” he added, “it will then be just a matter of cleaning up Buna Mission.”31

General Eichelberger described the situation “as it is at present” in these words:

On the right, the Australians with their tanks have moved up to the mouth of Simemi Creek, [and] the entire area of the two strips is in our hands. Martin’s men have extended to the left from the Old Strip for several hundred yards so that the forces of the Urbana and Warren fronts are now only about 600 yards apart. On the left, we have established a corridor between Giropa Point and Buna Mission, and have moved enough men in there to make it hold. The famous “Triangle” which held us up so long, was finally taken, and our men also occupy the island south of Buna Village. Today, we are moving on Buna Mission from both directions, and I sincerely hope we will be able to knock it off.

After noting that there had hitherto been many disappointments in the campaign, he went on to say, “Little by little we are getting those devils penned in and perhaps we shall be able to finish them shortly.”32

Colonel Yazawa’s Mission

At Rabaul, meanwhile, the impending collapse at Buna was causing 18th Army headquarters the deepest concern. On 26 December General Adachi ordered General Yamagata (whose headquarters, it will be recalled, was then at Danawatu, north of Gona) to move all his troops by sea to Giruwa. He was to use them first to rescue the Buna garrison. If the rescue failed, he was to divert them to the defense of Giruwa and hold it to the last. Two days later, Adachi ordered Buna evacuated. Its defenders were to fight their way to Giruwa with the help of a special force which would be under command of Colonel Yazawa, who was to proceed to Buna Mission from Giruwa by way of the beach and attack the American left flank. After cutting his way through to the beleaguered Japanese Army and Navy troops holding the mission, he was to withdraw with them to Giruwa.33

It was a desperate plan, but not necessarily an impracticable one. The Japanese must have known from clashing with Lieutenant Chagnon’s fifty-two men near Tarakena that the American flank covering Buna was virtually undefended. They may have thought, therefore, that Colonel Yazawa’s raiding party might still save the defenders of Buna Mission—only about two miles from Tarakena by beach—by launching a sudden surprise attack, advancing swiftly, and making a quick withdrawal.

General Yamagata lost no time in complying with General Adachi’s orders. On 27 December he ordered 430 men from Danawatu to Giruwa, with orders to report to Colonel Yazawa. Yazawa, who had led his regiment across the Owen Stanleys and back, was perhaps the most experienced and resourceful commander the Japanese had at Giruwa. The fact that he was detailed to the task of rescuing the Buna garrison was an indication of the importance Rabaul attached to his mission.

General Yamagata arrived at Giruwa on 29 December and, two days later, gave Colonel Yazawa his orders. The rescue operation, the orders read, was to be directly under Yamagata’s command. It was to be undertaken as soon as a suitable concentration of forces reached Giruwa from Danawatu.34 The move came too late. Even as

Yazawa began assembling troops for the thrust eastward, the fall of Buna Mission was imminent, and most of its defenders had only a few hours to live.

The Envelopment

On New Year’s day, while Warren Force and its tanks were reducing Giropa Point, Urbana Force launched what it hoped would be the final assault on Buna Mission. Early in the morning, while Company B attacked eastward toward Giropa Point, the artillery and mortars laid down a heavy barrage on the mission and the rest of Urbana Force struck at the Japanese line around the mission. Captain Cronk attacked from the mission spit, and Major Schroeder’s troops, pivoting on Entrance Creek, moved on the mission from the southeast. Some Company B men could already see the tanks on Giropa Point, but the unit was still held up by very strong enemy resistance. Company F, 128th Infantry, left alone on the spit when Colonel Grose withdrew Company E, 127th Infantry for reorganization, also found itself unable to move forward. In the swamp Company C, supported on the right by Company M, moved forward 150 yards, and the remaining companies to the right of M—F, A, and L, with I and D immediately to the rear—made some progress.

The enemy had thus far fought with the greatest tenacity, but evidence of his disintegration was not lacking. On the evening of 1 January while Colonel Smith of the 2nd Battalion, 128th Infantry, and Major Clarkson of the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, established a joint Urbana Force-Warren Force outpost in the no man’s land between their two fronts, Japanese troops were sighted for the first time trying to swim from the mission—an unmistakable sign that the mission’s defense was on the point of collapse.35

Urbana Force made careful preparations for the next day’s attack. The main effort was to be along the coast. It was to be spearheaded by two relatively rested units, Company G, 127th Infantry, and Company G, 128th Infantry, which had gone into reserve when the troops on the mission spit failed to knock out the bunkers facing the north bridge. Company H, 127th Infantry, would cross over from the island as soon as either Company F, 128th Infantry, advancing from the mission spit, or Company C, 127th Infantry, moving up through the swamp north of the gardens, took over the area north of the bridge and made repair of the bridge possible.36

The Japanese continued their desperate attempts to escape. Just before dawn of the next day, Saturday, twenty enemy soldiers carrying heavy packs and led by a lieutenant made a break for the beached landing barges on the mission spit. They had three machine guns with them and their packs were loaded with food, medicine, and personal effects, as if for a quick getaway. Captain Cronk’s company turned its machine guns and rifles on them and cut them down to a man. At daylight, observers all the way from Buna Village to Tarakena caught sight of large numbers of Japanese in the water. Some

were swimming, others were clinging to boxes, rafts, and logs; still others were trying to escape in small boats. Artillery and machine gun fire was immediately laid down on the troops in the water, and, at 1000, the air force began systematically strafing them with B-25’s, P-39’s, and Wirraways.37

The two top Japanese commanders at Buna had chosen to die at their posts. Realizing that the end was near, Captain Yasuda and Colonel Yamamoto met at a central point the same day, Saturday, and killed themselves in the traditional Japanese fashion by cutting open their bellies.38

Despite the fact that the mission was already partly evacuated, there were still enough Japanese left in the mission and along its approaches to give Urbana Force (in General Eichelberger’s phrase) “the darndest fight” all day.39 At 1000, just as the attack was about to open, Major Schroeder, who was in a forward observation post at the time, was struck and mortally wounded by a Japanese bullet which penetrated his skull. Capt. Donald F. Runnoe, a member of Schroeder’s staff, at once took over command of Schroeder’s battalion, and Colonel Grose came up and took personal charge of the coastal drive.40

A heavy artillery barrage and white phosphorous smoke shells hit the enemy before the troops finally jumped off at 1015. Captain Cronk’s company on the spit attacked southeast. Company C in the swamp, with Company M still on its right, attacked toward the north bridge between the island and the mission. The two G Companies—Company G, 128th Infantry, and Company G, 127th Infantry, with the latter unit under Captain Dames leading—passed through the lines of Companies I, L, and M and advanced through the Coconut Plantation to attack the mission from the southeast. The attack went smoothly from the first. The phosphorous shells set fire to the grass and trees at several points in the mission area and, in one instance, exposed a whole line of enemy bunkers to Allied fire. Attempts by the Japanese to flee these exposed positions were met by machine gun fire from the troops on the island and on the mission spit. As the phosphorous shells exploded in trees, they also set afire several of the huts in the mission. When enemy troops in dugouts beneath the burning huts tried to escape, they ran into bursts of Allied fire which killed most of them.

The remaining Japanese continued their dogged last-ditch resistance and had to be rooted out of each dugout and bunker by grenade, machine gun, and submachine gun fire. Company C, 127th Infantry, on the left, and Company G, 127th Infantry, on the right, made excellent progress, but Company F, 128th Infantry, on the mission spit was held up, as was Company B, 127th Infantry, which had meanwhile resumed its attack to the eastward.41

37-mm. antitank gun in position to fire at the enemy in Buna Mission

At 1400 Company C was in sight of the bunkers covering the north bridge. An hour and a half later Company G, 127th Infantry, reached the point of the mission with Company G, 128th Infantry, hard on its heels. Only scattered rifle fire met the troops, and they quickly took their first prisoners—a dozen Chinese laborers, naked except for breechcloths.

Ten minutes later Company C came up, followed by Company M, and in a few more minutes Companies I, L, and A reached the scene. The engineers had meanwhile been repairing the north bridge. By 1620 Company H was across it, thus finally completing the envelopment.

The mission was overrun by 1632. The remaining enemy troops in the area were either flushed out of their hiding places and killed, or entombed in them. By 1700 the fighting was over except in a few pockets of resistance near the beach. There a handful of Japanese held out stubbornly and were left to be dealt with the next day.

The mission was a scene of utter desolation. All through the area the ground was pitted with shell holes. The trees were broken and bedraggled. Abandoned

weapons and derelict landing craft littered the beach, and Japanese dead were everywhere.42

In its attack toward Giropa Point, Company B had been held up by a line of enemy bunkers in the road junction near the coast, which had been bypassed in the coastal advance. As soon as he could, General Eichelberger pulled Company C out of the mission area and sent it to the assistance of Company B. The two companies launched a concerted attack late that afternoon, cleared out the bunkers, and by 1930 had made contact with the 2/12 Battalion. With the 2/10 Battalion and the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 128th Infantry, the 2/12th had finished clearing out the area between Giropa Point and the west bank of Simemi Creek earlier in the day.43 After more than six weeks of fighting, the Buna area in its entirety was finally in Allied hands.

The End at Buna

Cleaning Out the Pockets

Mopping up of isolated pockets of resistance on both Warren and Urbana fronts continued for several days until the last of the enemy troops were accounted for. An observer describes the scene on 3 January, a Sunday, as follows:

[By] Sunday, the ... front from the shattered palms of Buna Village to Cape Endaiadere was almost peaceful. It was possible to walk its entire length and hear only a few scattered shots and occasional bursts of mortar fire. In the ... swamp ... a few Japanese snipers still held out, in a patch of jungle ... a bunker or two still resisted, but great stretches of the front were scenes of quiet desolation. ... The only considerable fighting during the day occurred in the jungle area southwest of Giropa Point, where a small group of laborers, estimated as high as a hundred, fled when the point was captured. Their intention perhaps was to try to escape through the swamps and jungles, and scatter into the interior. ...

Americans and Australians however drew a line around them from all sides and made contact along the beach between Buna Mission and Giropa Point, and methodically mopped up the enemy pocket.

Americans quelled the last resistance to Buna Mission by Sunday noon in a little thicket on the beach where a few Japanese held out in bunkers. Routed from the bunkers, some scurried behind a wrecked barge on the beach and continued to fire. They were finally killed by a high explosive charge that blew the barge and the Japanese to bits.

By noon, the Americans had counted roughly 150 Japanese dead in the Buna Mission area.

Small squads finished the job of eliminating the last fighting Japanese. Some Americans [went swimming in] the sea. Some washed out their clothing for the first time in weeks, some simply slept the deep sleep of exhaustion, curled up under shell-shattered trees or in sandy foxholes. By Tuesday, the only Japanese left in the area extending from Buna Village through Cape Endaiadere were roving groups and individuals ... who were hiding out in jungle and sago swamp, and who by now had become desperately hungry. These Japanese were trying to keep under cover during the day [to prowl] at night through moonless blackness in American-Australian lines seeking something to eat.44

Some 190 Japanese were finally buried at Buna Mission, and 300 at Giropa Point.

32nd Division troops examine booty after taking Buna Mission

Fifty prisoners were taken. Warren Force took twenty-one horribly emaciated Koreans and one Japanese soldier. Urbana Force took twenty-eight prisoners, mainly Chinese and Koreans. Of the few Japanese among them most were captured near Siwori Village and Tarakena when they were caught naked and unarmed as they swam in from the sea.45

Booty was heavy on both fronts. On the Warren front it included, in addition to the three-inch naval guns and the pompoms, rifles, machine guns, radio equipment, several 37-mm. guns, two 75-mm. mountain guns on wheels, nine unserviceable trucks, some of American make, and a number of smashed fighter aircraft, two of them Zero-type planes that were found on the Old Strip and looked as if they could be repaired. Booty taken by Urbana Force, besides the weapons taken in the Triangle and several antiaircraft guns captured in the Government Gardens, included a 75-mm. gun and miscellaneous items of equipment. Hardly

Emaciated prisoners being led to the rear area for questioning

any food or ammunition was found on either front.46

The Congratulatory Messages

By 3 January it was obvious that all organized resistance on the Buna side of the Girua River was over. In a special memorandum issued at noon that day, General Eichelberger told American troops who had taken part in the fighting that they had had their baptism of fire and were now veterans. The lessons they had learned at Buna, he added, would serve to reduce losses in the future and bring further victories.47

Later that day General Blamey sent a message of congratulations to Brigadier Wootten and the troops serving under him on the successful conclusion of the fighting on the Warren Front. Their operations, he said, had been marked “by the greatest thoroughness in planning,” by “constant

General Blamey touring the battle area with General Eichelberger

steadiness in control,” and by “valor and determination in execution.”48

General Herring in turn, issued a special order of the day in which he expressed to Australians and Americans alike his appreciation of “their magnificent and prolonged effort.” He dwelt on the strength of the enemy’s defenses, his tenacious resistance, the hardships that the men had borne, and the fortitude with which they had borne them. He complimented all concerned on their steadfastness and determination and said, “You have done a job of which both our countries should indeed be proud.”49

General Marshall sent General MacArthur his congratulations the next day. MacArthur thanked Marshall for his congratulatory message, and added, “However unwarranted it may be, the impression prevailed that this area’s efforts were belittled and disparaged at home, and despite all my efforts to the contrary the effect was

depressing. Your tributes have had a tonic effect.”50

Buna’s Cost

Battle Losses

There were 1,400 Japanese buried at Buna—500 west of Giropa Point and 900 east of it.51 On the Allied side, 620 were killed, 2,065 wounded, and 132 missing. The 32nd Division sustained 1,954 of these casualties—353 killed, 1,508 wounded, and 93 missing;52 the 18th Brigade had 863 casualties—267 killed, 557 wounded, and 39 missing.53

The total casualties were thus 2,817 killed, wounded, and missing—a figure considerably in excess of the 2,200 men the Japanese were estimated to have had at Buna when the 32nd Division launched its first attacks upon them there.54

Losses Due to Sickness and Disease

The troops had been plagued unceasingly by all manner of chiggers, mites, and insects, exposed to debilitating tropical infections, fevers, and diseases, and forced most of the time to eat cold and inadequate rations, sleep in water-filled foxholes, and go for days on end without being dry. Their gaunt and haggard faces, knobby knees and elbows that poked through ragged uniforms attested to what the men had been through.55

Some of the hazards that faced them were revealed vividly in a letter written on 10 January by Maj. E. Mansfield Gunn, a medical officer on General Eichelberger’s staff:

... Be sure to rinse the dyed jungle equipment over and over again in cold water, otherwise it will ruin everything [and] make everything stink. ... Furthermore, we are not sure [the dye] is not absorbed by the body, and then excreted in the urine, because some of the urine would indicate [that was the case]. ... Tablets for individual chlorination of water in the canteen would be of the greatest value for all; two pairs of shoes are definitely needed [because] everything dries very slowly. A chigger repellent for each individual is needed for there are millions of the little fellows.

[There] is a growing incidence of scrub typhus here. ... The inoculations we all received were designed to prevent the European typhus, and hence there is nothing to do but hope. There are some tremendous rats in the area, and no doubt the fleas on same are carrying the infection from the dead Japanese to our soldiers. One medical officer just died of the disease and another one is in very poor shape today. There has been an awful lot of work to do with these units, and under existing travel conditions, it is the toughest situation any of us have ever been in. ... Sickness of all sorts, particularly of the various tropical

fevers is on the increase also, so I expect that almost everyone in the division will come out of here either wounded or sick. I do not intend to paint a depressing picture, but that is the truth as things stand today. The figures will be appalling to you when you see them.56

As late as mid-January Colonel Warmenhoven, then the division surgeon, was urging that all troops be compelled to take quinine daily, but the difficulty was that the medicine was still in short supply. He cited the case of a battalion in the 128th Infantry that had gone for several days entirely without it. Warmenhoven found also that the drinking water was often polluted and sometimes insufficiently chlorinated. There were now field ranges at most of the jeepheads, and some of the men had canned heat and primus stoves, but the division surgeon nevertheless noted that rations were still inadequate and that the troops were still eating them cold most of the time.57

The cost of sickness and disease at Buna was to reach staggering proportions. In a check of the health of the 32nd Division undertaken shortly after the Buna mop-up was completed, the temperature of 675 soldiers, representing a cross section of the division’s three combat teams, was taken. Colonel Warmenhoven reported that “53 percent of this group of soldiers were running a temperature ranging between 99 degrees to 104.6 degrees. ... In order of prevalence, the cause of the rise in temperature is due to the following: Malaria, Exhaustive States, Gastro-Enteritis, Dengue Fever, Acute Upper Respiratory Infection, and Typhus (scrub).” The average normal sick-call rate of a command, the colonel pointed out, was 3.8 percent of its strength. The sick-call rate of the 32nd Division was 24 percent, and going higher. Some 2,952 men (more than three quarters of them from Buna where the division had made its primary effort) were already hospitalized because of disease and fever, and fifty to one hundred were being evacuated from Buna to Port Moresby daily for the same cause.58

The Situation to the Westward

Colonel Yazawa Scatters the Tarakena Patrol

Ordered on 31 December to rescue the troops at Buna Mission, Colonel Yazawa had been unable to leave Giruwa until the evening of 2 January and then with only 250 men, most of them from the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry.59 Shortly after he left Giruwa he learned that Buna Mission had already fallen. His energies thereafter were devoted to picking up as many of the survivors as possible. The success of his rescue mission required that the spit off Tarakena (on which many of the swimmers were landing, after hiding out during the day from Allied planes and patrols) be in Japanese

hands. Ordering a careful reconnaissance of Lieutenant Chagnon’s position, he attacked it at dusk on 4 January with the bulk of his force.60

Lieutenant Chagnon had been reinforced that afternoon by twenty-one men of Company E, 126th Infantry. When attacked, he had under his command seventy-three soldiers from seven different companies—including men from the Headquarters and Service Companies of the 127th Infantry—a 60-mm. mortar, and three light machine guns. The force was short of ammunition and grenades, and the attack came as a complete surprise. Hit from the front, rear, and left, Chagnon’s men fought as best they could until all their ammunition was gone and they had no recourse but to swim for it. The lieutenant, who retrieved one of the machine guns under fire and continued operating it until it jammed, was the last man out. Members of Chagnon’s patrol kept straggling into Siwori Village all that night. By the following day all but four had come in—a small loss in view of the fact that Yazawa’s attack had been made in overwhelming strength.61

Having cleared Chagnon’s position on the spit and mainland, Yazawa proceeded with his rescue work. He was soon able to report that he had picked up some 190 survivors of the Buna garrison. Most of them had swum from the mission and had had the good sense to keep out of sight during the day.62

Colonel Grose meanwhile had not been idle. By the early morning of 5 January he had part of Company F, 127th Infantry, across Siwori Creek. The crossing was unopposed. The men quickly re-established themselves on the other side of the creek and began moving northwestward.63

The Stalemate at Sanananda

Buna had fallen, and the bridgehead across Siwori Creek had been re-established. The campaign, however, was far from over. West of the Girua River on the Sanananda front things were at a stalemate, and had been for some time. In his order of the day of 3 January General Herring had told the troops that the battle for Buna was “but a step on the way.” They still had, he said, the difficult job ahead of them of cleaning the enemy out of the Sanananda area, a job that would “not be any easier than Buna.”64

It was a timely reminder. As Col. Leslie M. Skerry, General Eichelberger’s G-1, put the matter: “While we were engaged in the Buna area, we did not have much opportunity to think about what was going on elsewhere. But after getting rid of the Japanese here, we awoke to the fact that there was another most difficult situation existing in the Sanananda area next door.” There,

Weary soldier sleeps after the battle is over

Skerry noted, “a state of semi-siege has been going on ... with little progress being made.”65

With the 127th Infantry in position to move on Tarakena, and the 18th Brigade, the tanks, and most of the guns in use at Buna available for use on the other side of the river, the time had come to move on the enemy’s Sanananda-Giruwa position in force.