Chapter 17: Clearing the Track Junction

The offensive on the Sanananda front had indeed bogged down. By the end of December the Allies had established roadblocks at Huggins and Kano, and made the first breaches in the formidable enemy perimeter which covered the track junction south of Huggins. These, however, were only interim victories. The Japanese were still fighting desperately in the track junction area south of Huggins; they were well entrenched in the area between Huggins and Kano; and they were holding strong positions north of Kano. The tactical situation, especially on the Motor Transport or M. T. Road, as the Soputa–Sanananda track was sometimes known, was to say the least unusual. As one observer, in describing it, remarked, “At first glance, the situation map was simply startling. Along the M. T. Road Red and Blue alternated like beads on a string.”1 The task was to squeeze out the Red—a supremely difficult task in the existing terrain.

General Herring Calls a Conference

The Arrival of the 163rd Infantry

There were actually three fronts on the western side of the river at this time. The first was south of the track junction; the second was in the roadblock area at Huggins and Kano; the third was in the Napapo–Amboga River area north of Gona. Brigadier Porter of the 30th Brigade, in charge of track junction operations, had under his command the 36 and 55/53 Battalions and what was left of the 126th Infantry troops fighting west of the river, then about 200 men. Brigadier Dougherty with his 21st Brigade headquarters was operating from the two roadblocks and had under his command the 39 and 49 Battalions and the 2/7 Cavalry Regiment. His battalions, the 2/14th, 2/16th, and 2/27th, normally a part of the 21st Brigade, were mopping up in the Amboga River area.

These battalions of the 21st Brigade had suffered extremely heavy casualties in this, their second tour of duty during the campaign. By late December they were down to less than company strength. The 2/27 Battalion, for instance, numbered 55 men and the 2/16 Battalion was down to 89. It was clear that if the brigade was to fight again it would have to be relieved quickly.2

Relief was already on the way. As planned by General Herring, a fresh headquarters, that of the 14th Brigade at Port Moresby, was to take over in the Gona area, and the 163rd Infantry Regiment of the 41st

Infantry Division in the roadblock area.3 The arrival at the front of the 163rd Infantry would release troops for action in the Gona area, make possible the immediate relief of the 21st Brigade’s battalions, and permit intensification of the attack both north and south of Huggins.

The 163rd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, consisting of the 163rd Infantry Regiment and 550 attached divisional troops, less artillery, arrived at Port Moresby on 27 December, 3,820 strong, under Col. Jens A. Doe.4 Though it looked for a time as if the regiment might be sent to the Urbana front, the final decision was to have it proceed, as General Herring had planned, to Sanananda rather than Buna.

On 27 December, the very day the 163rd Infantry reached Port Moresby, General MacArthur had conveyed orders to General Blamey (through General Sutherland who was then visiting the front) that the regiment was to be sent to Buna to help in the reduction of Buna Mission, rather than as previously planned to the Sanananda front. General Blamey immediately protested this change of plan. He pointed out that General Eichelberger had sufficient troops to take Buna. He insisted that it was imperative that the 21st Brigade be relieved immediately, if it was to continue as a fighting force, and expressed his regret that General MacArthur had taken it upon himself to interfere in the matter. Blamey wrote that while he did not “for one moment question the right of the Commander-in-Chief to give such orders as he may think fit,” he nevertheless gave it as his belief that nothing could be “more contrary to sound principles of command than that the Commander-in-Chief ... should [personally] take over the direction of a portion of the battle.”5 General MacArthur apparently saw the point, and General Herring’s decision to use the 163rd Infantry on the Sanananda front was permitted to stand.

The 163rd Infantry, the unit which had engendered this high-level contention, was by this time well-trained, and the men, fresh, ably led, and in superb physical condition,

were ready for combat.6 It was at once arranged that they would be flown to the front, the 1st Battalion leading. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, which were to come in later, would follow in that order.

Early on 30 December the 1st Battalion and regimental headquarters were flown over the mountains, part to Dobodura and the rest to Popondetta. Lt. Col. Charles R. Dawley, Colonel Doe’s executive officer, who was with the echelon that landed at Dobodura, immediately reported to Advance New Guinea Force, General Herring’s headquarters, at Dobodura. Shortly thereafter Colonel Doe flew in from Popondetta, and he and Dawley had a conference with General Herring, Maj. Gen. F. H. Berryman, General Blamey’s chief of staff, and General Vasey, who had meanwhile come in from Soputa. During the course of the conference, Doe and Dawley were told that the 163rd Infantry would fight west of the Girua—the first direct intimation they had had of what the regiment’s role would be. They then went with Berryman and Vasey to see General Eichelberger.7

The four officers reached Eichelberger’s headquarters about 1030, and were offered tea. General Eichelberger seemed to be under the impression that he was to get the 163rd Infantry for action on his side of the river, and this, as General Doe recalls, is what followed: “While tea was being prepared, General Eichelberger explained the situation to us and told me he would take me up front after lunch to show me where the 163rd Infantry was to go. Generals Vasey and Berryman sat silent, and when they did not speak up, I told General Eichelberger I had been informed the 163rd was to go to the Sanananda front.” “Plainly surprised,” it was now General Eichelberger’s turn to remain silent.8

When tea was over, Doe and Dawley went on to 7th Division headquarters at Soputa with General Vasey. Vasey went over the situation with them and told them that they were to take over in the roadblock area as soon as possible. On 31 December, while the 1st Battalion assembled at Soputa, General Vasey, Colonel Doe, and the regimental staff went forward to Huggins and reconnoitered the area. On 1 January, while Doe and Dawley were busy establishing a supply base for the regiment, the commander of the 1st Battalion, Lt. Col. Harold M. Lindstrom, and his staff went forward to Huggins and made arrangements to relieve Brigadier Dougherty’s forces. On 2 January, the day that Buna Mission fell, the 1st Battalion took over at Huggins and Kano, and Colonel Doe took command of the area from Brigadier Dougherty the next day.9 (Map 16)

General Vasey at once reshuffled his command. He ordered the 39 Battalion, which had been holding the roadblock, the 49 Battalion, which had been guarding the supply trail, and the 2/7 Cavalry Regiment, which had been operating from Kano, to replace the 36 and 55/53 Battalions south of the

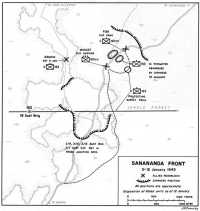

Map 16: Sanananda Front, 3–12 January 1943

track junction. Upon their relief, the latter two battalions would move to Gona, where they would relieve the depleted battalions of the 21st Brigade, and come under command of 14th Brigade headquarters which had then just reached the Gona area. The relief of what was left of the 126th Infantry would be accomplished as soon as the 18th Brigade could be redeployed from Buna to the Sanananda side of the river.10

General Herring, Commander, Advanced New Guinea Force (left), and General Eichelberger

The Conference of 4 January

General Herring had ordered on 29 December that, when Buna fell, the 18th Brigade and the bulk of the guns and tanks in use east of the river be redeployed to the Sanananda front.11 On 2 January, with all organized resistance at Buna at an end, he ordered that two troops of 25-pounder artillery previously in use at Buna be assigned to the Sanananda front. The next day he ordered a portion of the tanks to Soputa. On 4 January Herring met at his headquarters with General Eichelberger, General Berryman, General Vasey, and Brigadier Wootten, to work out a final, comprehensive plan for the reduction of the enemy positions west of the river.12

Although the conferees had met to devise a plan to destroy the enemy, they discovered that they had very little knowledge of his strength and dispositions, especially those north of Kano. It was supposed that he had plenty of weapons and ammunition but was short of food; his strength, however, was anyone’s guess. In describing the conference several days later General Eichelberger wrote, “We decided that we did not know whether there were one thousand Japs at Sanananda or five thousand.”13

Despite the lack of any definite knowledge about the enemy’s strength, the Allied commanders, acting on the assumption that there were still several thousand Japanese effectives in the area, quickly agreed upon a basic plan of action. As soon as the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 163rd Infantry, and 800 replacements for the 18th Brigade reached the front, the 18th Brigade, the 163rd Infantry, and the 127th Infantry would launch a double envelopment of the enemy’s Sanananda-Giruwa position. The first two units, under command of General Vasey, would move on Sanananda by way of the Cape Killerton trail and the M.T. Road respectively. The 127th Infantry would complete the envelopment by moving on Sanananda by way of Tarakena and Giruwa.

The main attack was to follow a number of essential preliminary operations. These would begin with the capture of Tarakena

by the 127th Infantry and the clearing of the area between Huggins and Kano by the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry. The 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, meanwhile, would capture a position astride the Cape Killerton trail, just west of Huggins. Then the 18th Brigade would clear out all enemy opposition south of Huggins. As soon as these preliminaries were completed, the general advance would begin, with the 127th Infantry attacking westward along the coastal track, and the 163rd Infantry and the 18th Brigade, northward, along the M.T. Road and the Cape Killerton trail.14

The 18th Brigade Reaches Soputa

The first elements of the 18th Brigade—brigade headquarters and the 2/9 Battalion—reached Soputa on 5 January, as did one troop (four tanks) of B Squadron, 2/6 Australian Armored Regiment. The tanks left Buna just in time, for extremely heavy rains had made the road net between the Old Strip, Dobodura, and Soputa impassable to vehicular traffic, and no more tanks or artillery were able to get through for days. The 2/10 Battalion arrived at Soputa on the 6th, and the 2/12 Battalion joined it a day later. The rest of the tanks and the two 25-pounder troops, which had been assigned to General Vasey upon the fall of Buna, had to remain where they were on the eastern side of the river because of the wretched state of the roads.

The weather had not only cost General Vasey the use of most of the tanks allotted to his front, but it had also made it impossible for him to make the best use of the additional artillery he had gained as a result of the fall of Buna. Because of the close quarters at which the battle was being fought, the two batteries in question, the Manning and Hall Troops, had no choice but to fire obliquely across the front, and to take special precautions not to hit friendly troops.15 The guns were useful, but they would have been much more useful had it been possible to get them across the river.

The weather had done General Vasey another disservice by temporarily dislocating the flow of supply. The rains were so heavy and the tracks so muddy that even jeeps could not use them. To compound the difficulties, the “all-weather” airstrips at Dobodura and Popondetta became so mired that they remained unserviceable for days. Fortunately for the Allied offensive effort, there was already enough material stockpiled at the front to tide the troops over until the weather changed.16

By 7 January the 18th Brigade troops from the other side of the river were all at Soputa. General Vasey ordered Brigadier Wootten to take command of the 2/7 Cavalry and to relieve Brigadier Porter’s remaining troops—the 39 and 49 Battalions and the remnants of the 126th Infantry. The orders provided that the 39 and 49 Battalions would go into divisional reserve near Soputa; that the 21st Brigade, whose shrunken battalions had by this time come in from Gona, would be returned forthwith to Port Moresby; and that the remaining

Sanananda Point. M. T. Road, lower left, joins the coastal Cape Killerton trail. Note enemy barges along the coast. (Photograph taken in October 1942)

126th Infantry troops, under command of Major Irwin, would be returned to their regiment at Buna as quickly as possible.17

The Relief of the 126th Infantry

The relief of the 126th Infantry troops was completed by the early afternoon of 9 January, and Major Boerem, who had been acting as Major Irwin’s executive officer, returned to Buna the same day to prepare for their reception.18 The Australians were not unmindful of the gallantry with which the American troops had fought, and of the heavy losses that they had sustained. On the 8th, Brigadier Porter issued orders adjuring them and his other troops to “march out in as soldierly a manner as possible, ... in keeping with the pride and quality of their past service.”19 In a letter which he gave to Major Boerem to deliver to General Eichelberger, Porter wrote:

I am taking the opportunity offered by Major Boerem’s return to you to express my appreciation of what the men of your division

who have been under my command have done to assist our efforts on the Sanananda Road.

By now it is realized that greater difficulties presented themselves here than were foreseen, and the men of your division probably bore most of them. ... Your men are worthy comrades and stout hearts. I trust that they will have the opportunity to rebuild their depleted ranks in the very near future. With their present fund of experience they will rebuild into a formidable force. ...20

When the troops had gone into action during the third week of November, they were 1,400 strong. Sixty-five men of regimental headquarters had transferred to Buna in early December, and there had been no other transfers. On 9 January, the day of their relief, the troops numbered only 165 men, nearly all of them in such poor physical shape as to be scarcely able to walk.21

Three days later, with the fighting strength of the unit down to 158 men, the troops began marching to Buna. Major Irwin was at their head, with Captain Dal Ponte, as he now was, as his second-in-command. After reaching their bivouac at Simemi in the afternoon, the men shaved and cleaned up as best they could and were issued some sorely needed shelter halves and mosquito nets. Two days later, 14 January, General Eichelberger had a little ceremony of welcome for them.22 “I received the troops,” he recalls, “with band music, and with what might well be described as a martial welcome. Actually, it was, whatever face could be put upon it, a melancholy homecoming. Sickness, death, and wounds had taken an appalling toll. ... [The men] were so ragged and so pitiful when I greeted them my eyes were wet.”23

The Preliminary Operations

Tarakena and Konombi Creek

The general plan of operations formulated on 4 January at General Herring’s headquarters provided that, until the 163rd Infantry and the 18th Brigade were completely in place and ready to move on Sanananda, the enemy was to be deceived into thinking that the coastal drive on Tarakena and across Konombi Creek was “the main push.”24 (See Map IV) General Eichelberger laid his plans accordingly. Urbana Force, now principally the 127th Infantry

(with elements of the 126th and 128th Infantries in reserve), would mount the push westward; Warren Force, principally the 128th Infantry, would remain in place and occupy itself with the beach defense.

Colonel Yazawa’s scattering of the Chagnon patrol from its position near Tarakena on the evening of 4 January made it necessary for Colonel Grose to order forward a fresh force to retrieve the lost beachhead on the other side of Siwori Creek. Artillery fire was laid down on the area during the night to make it untenable for the Japanese until the troops got there. Early on the 5th, Company G, 127th Infantry, under command of Lieutenant McCampbell, crossed Siwori Creek, followed shortly afterward by Company F, under 1st Lt. James T. Coker. The crossing was slow, for the creek was broad and Colonel Grose had only two small boats (one a black rubber affair captured from the Japanese) with which to ferry the troops and their supplies across. The troops finished crossing by 0900 and began moving westward—Company G along the narrow, exposed coastal track and Company F, in the swamp, covering it from the left.

Colonel Yazawa’s troops, principally elements of the 1st Battalion, 170th Infantry, the so-called Nojiri Battalion, were still in the area. During the 5th and 6th they made several stubborn stands, retreating only when the Americans were on the point of overrunning their positions. By the 7th the two companies were within 500 yards of the village, and there the enemy again made a stand. Company E, under 1st Lt. Powell A. Fraser, meanwhile moved onto the sandspit with a 37-mm. gun, and began to enfilade the Japanese with canister. With this support the two companies again pushed the enemy back on the evening of the 7th. They captured five machine guns, including two lost by the Chagnon patrol.25

The next day Company G again moved forward. As before Company E was on the right supporting its advance by fire, and Company F in the swamp covered it from the left. The numerous enemy troops in the swamp and the swamp itself made it difficult for Company F to keep up.26 Spurred on by Lieutenant Coker, the company commander, and S. Sgt. Herman T. Shaw, in command of the leading platoon,27 the company drew abreast of Company G and kept its position there for the rest of the day.

At 1600 Company G attacked again. It reached the outskirts of Tarakena village within the hour and captured three enemy machine guns, an enemy mortar, and the remaining machine gun lost by the Chagnon patrol. Two fresh companies of the 1st Battalion, Companies C and A, ordered forward earlier in the day by Colonel Grose, had just come up, and reduction of the village was left to them. The two companies passed through Company G, Company C leading, and launched the attack that evening. The attack gained its objective quickly. Company C was inside the village

Collapsible assault boats being used by 127th Infantrymen to cross the Siwori Creek. Note guide rope across the creek

by 1830 and the fighting was over by 2130.28 Forty-two Japanese were killed, and a quantity of Japanese ordnance was captured. The 127th Infantry sustained nineteen casualties in the day’s fighting—two killed, sixteen wounded, and one missing.29

By this time the three companies that had launched the attack were much below strength. Company F had only 72 men left; Company A, 81; Company C, 89. Morale, however, was good. As General Eichelberger, who had gone forward to the sandspit that morning to see how things were going, reported to General MacArthur the next day, “Now that the men are living where the Japanese lived, they look entirely different. The swamp rats who lived in the water now have their place in the sun and I even heard some singing yesterday for the first time.”30

The village in hand, the next step was to cross Konombi Creek, a tidal stream about forty feet across. A suspension bridge over the creek was badly damaged, and attempts on 9 January to cross it were met by fire from hidden enemy emplacements on the opposite shore. Colonel Grose’s plan was therefore to flank the enemy positions by sending an element of Company C across the creek that night in the two available boats. The company commander, 1st Lt. Tally D. Fulmer, was put in charge of the crossing.

The troops embarked at 0240 on the 10th. The swift current started taking the boats out to sea, but the danger was perceived in time, and the men reached shore before any harm was done.

There was only one thing left to do: secure a guy wire to the opposite shore. Two volunteers, S. Sgt. Robert Thompson of Company C and Pfc. Jack K. Cunningham of Company E, swam across the creek in the dark and, just before daylight, had a wire in place on the other side. It broke when the leading boat caught on a sand bar, and the crossing had to be made in daylight.

In late afternoon Sergeant Thompson again swam the creek, followed this time by four volunteers from Company C—Pfc. Raymond Milby and Pvts. Raymond R. Judd, Marvin M. Petersen, and Lawrence F. Sprague. To cover the crossing, Lieutenant Fraser of Company E emplaced his mortars and his 37-mm. gun on the east bank of the creek. As the men began swimming across, armed only with pistols and hand grenades, Fraser and his weapons crews engaged the enemy on the opposite shore with fire. The enemy replied in kind, but Fraser and his men held their position along the river bank, and all five men got safely across the creek.

By 1740 the wire was in place, and Lieutenant Fulmer and a platoon of Company C began crossing. The boat made the trip safely, covered by fire from Lieutenant Fraser’s mortars and 37-mm. gun, which quickly reduced the enemy emplacements commanding the bridge. Thereafter the crossing went swiftly. Company C was across by 1755, followed closely by Company A. By evening the two companies, disposed in depth, held a 200-yard bridgehead on the other side of the creek.31

On the other side of the creek the advancing troops ran into terrain difficulties. No trails could be found branching southward from the coast, and the coast line, a narrow strip of sand bounded by a tidal swamp which came almost to the shore, was frequently under water at high tide.32 Since the enemy was present in the area in strength, it seemed to be the better part of wisdom to hold up the 127th Infantry advance until the concerted offensive on the Sanananda front got under way and eased the enemy pressure.

General Eichelberger explained the situation to General MacArthur on the 12th. “On their side of the Girua,” he wrote, “we have a fine bridgehead established across [Konombi] Creek, but now comes a section where the mangrove swamp comes down to the sea. At high tide the ocean is right in the swamp. ...” It would not be wise, he thought, for Grose to extend too far until

there had been “developments across the Girua.”33 The coastal advance, in short, would mark time until the 163rd Infantry and the 18th Brigade began driving directly on Sanananda.

The Attacks Between Musket and Kano

The scheduled operations on the M. T. Road preliminary to the concerted advance on Sanananda had meanwhile been proceeding. The 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry, and regimental headquarters took over complete responsibility for the roadblock area on 3 January. Colonel Doe, who had immediately given Huggins the regimental code name, Musket, had deployed Company C and a platoon of Company D at Kano. Regimental headquarters, battalion headquarters, Company B, and Company D, less the platoon at Kano, were in place at Musket. Company A (less one platoon at Moore, a perimeter about 400 yards east of Musket) covered the supply trail east of the M. T. Road.

By this time Musket (or Old Huggins as it was also known) was a well-developed position. It consisted essentially of an inner and outer perimeter, with rifle and automatic weapons squads in square or circular formation on the periphery of each perimeter, and field kitchens (which had finally come up) in the center. The squads, each with its own straddle trench and water seep, were spaced about fifteen yards apart. Within the inner perimeter were regimental and battalion headquarters, switchboard, aid station, ammunition dump, and the 81-mm. mortars. Between the two perimeters were company headquarters and forward dumps. The entire area was crisscrossed with trenches, and the scene, when newly arrived troops were moving into or through the position, put one observer in mind of “a crowded seal rock.”34

Upon taking over from the Australians, the troops had been troubled by fire from riflemen in the tall jungle trees that overlooked the perimeter. Though experienced intermittently throughout the entire twenty-four hours, the fire was particularly intense at mealtimes. The troops were also bothered at night by individual enemy riflemen or small patrols. These would harass the flanks and the southern end or rear of the perimeter with short bursts of rifle or automatic weapons fire. Colonel Doe lost no time in devising means to abate these nuisances. He established two-man sniper-observer posts in slit trenches along the forward edge of the perimeter, and in trees on the flanks and rear. Using ladders made of telephone wire with stout wooden rungs, the troops in the trees made it their business to fire systematically on all trees thought to harbor snipers, and were particularly active during such times as the Japanese were firing. As soon as the posts in the trees were established, small counter sniping patrols of two or three men, covered by the troops in the trees, began to pick off the Japanese tree marksmen from the ground. To stop Japanese sniping at night from the flanks and rear, the counter sniping patrols set out booby traps, consisting usually of two grenades tied to adjoining trees with the pins connected by a cord.

These measures got results quickly. The enemy marksmen were thinned out and forced back. Soon the only reminder that there were still tree snipers in the area was

Setting up a field switchboard

distant, ineffective fire, delivered as a rule only at mealtimes.35

With the perimeter more or less secure, Musket’s role became principally that of a regimental bivouac area, and stringent security measures were observed in the area, especially at night. The men took to their slit trenches at dusk and stayed in them till daylight. Movement through the area during the night was strictly forbidden, and front-line troops on the outer perimeter were under orders to use only hand grenades against suspicious noises or movements in order to avoid disclosing weapons positions to the enemy.

The delivery of supplies, haphazard in Captain Huggins’ and Lieutenant Dal Ponte’s time, had by now become a routine operation. Natives working in shifts brought the supplies forward to specified points behind the firing line and carried back the wounded. A water purification unit was installed, and the individual water seeps were filled in. Additional mortars and two 37-mm. guns, firing canister, were emplaced to advantage within the perimeter.

Pending the arrival of the rest of the regiment, the 1st Battalion gave the enemy line a thorough probing. It did not take long to

find that the Japanese had two strong perimeters between Musket and Kano, about 200 yards north of Musket and roughly the same distance south of Kano. The perimeters were abreast on either side of the road, with the one on the west about twice the size of the one on the east. Since the two positions were on relatively dry ground in a swampy jungle area, dominated like Musket by tall trees, they could be reached only from the track or through the swamp.

The 2nd Battalion, led by Maj. Walter R. Rankin, reached the front on the 7th. Colonel Doe disposed the battalion along the supply trail east of the M.T. Road and ordered the 1st Battalion to reduce the two enemy perimeters between Musket and Kano the next day. If the attack proved successful, the battalion would move into Kano, and Major Rankin’s battalion would take over at Musket.

The plan of attack called for Companies B and C to attack from either flank—Company B, the larger perimeter west of the road, and Company C, the smaller perimeter east of it. Company B would move out of Musket and, after circling west and north, hit the larger perimeter from the west; Company C, advancing from a position between Moore and Kano, was to hit the smaller perimeter east of the track from the northeast. The 25-pounders of Hanson Troop and the machine guns and mortars of the rest of the battalion would be available to support the attack.36

Just before noon on 8 January, the Hanson Troop put down a fifteen-minute concentration on both perimeters. The troop now had only shells with delayed fuse, and these, as General Doe recalls, “simply buried themselves in the muck or exploded under the ground surface.” Although the two companies were covered by all the mortars and machine guns the battalion could muster, neither attack was successful. Hanson Troop, firing from the southeast, could not lay down supporting fire for Company B’s flank attack. The result was that the company, forced to attack frontally, not only ran into fire from both perimeters, but also hit the larger perimeter at its strongest point. The company recoiled and was finally forced to dig in that night about thirty yards short of its objective.

Company C had even worse luck. It had rained heavily the day before, and the company, attacking in a southwesterly direction, ran into what had become, since the previous day, a waist-deep swamp. The troops tried to cut through the swamp under heavy fire, but the swamp was too deep and the fire too heavy. After losing one of its officers, 1st Lt. Harold R. Fisk, whose body could not immediately be recovered, the company returned to its original position at Kano, which it renamed Fisk a day or two later. Company B, in slit trenches forward of Musket which were waist-deep in water, was relieved that night by Company E. The next morning, after Company B’s troops had had some sleep and some hot food, they took over their former positions, and Company E rejoined its battalion, still in place along the supply trail.37

The Establishment of Rankin

On 7 January, with the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, and Brigadier Wootten’s

first 400 replacements at hand, General Vasey issued the divisional plan of attack. The attack would be in four stages. In Stage I, the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, would cut off the enemy in the track junction by getting astride the Killerton trail; in Stage II, the 18th Brigade, the 2/7 Cavalry, and the tanks would destroy the Japanese in the track junction, and clear out the area south of Musket; in Stage III, the 163rd Infantry would move on Sanananda Point by way of the M.T. Road, and the 18th Brigade would do so by first moving north along the Killerton trail and then turning east to complete the envelopment. Stage IV would be the mop-up.

Stage I, the blocking of the Killerton trail, would secure two main advantages. It would prevent the rapidly failing Japanese in the track junction from using it as an escape route, and would provide the 18th Brigade with a jumping-off point for its advance on Sanananda when it had completed clearing out the track junction.

Early on 9 January, after being briefed on its role by Colonel Doe, the 2nd Battalion, under its commander, Major Rankin, moved out from its position along the supply trail, passed through Musket, and began marching on the Killerton trail a half mile away. The march was in a southwesterly direction, and during its course telephone wire was paid out to maintain communications.

The first enemy opposition was encountered at 1030, just as the battalion was approaching a narrow, corridor-like, north-south clearing through which the Killerton trail ran. Major Rankin ordered a platoon of Company G to the edge of the jungle at the southern end of the corridor to act as cover for the battalion’s left flank. The platoon began receiving heavy rifle and mortar fire from a cluster of enemy positions enfilading the corridor from the south. Company headquarters, a second platoon, and half of the company’s weapons platoon crossed the clearing before heavy machine gun and rifle fire stopped further crossing. Under Capt. William C. Benson, the rest of the company finally advanced through the clearing and across the trail via a sap dug through the clearing. The main body of the company set up a perimeter on the west side of the trail, and the covering platoon remained in place to the east of it. There it was strongly engaged by the Japanese who were in position only a few yards away.

The rest of the battalion, under Capt. Paul G. Hollister, the battalion S-3, had meanwhile turned north. After following the edge of the jungle for about 250 yards, the troops crossed over and, against only light opposition, established themselves astride the trail. The new perimeter, which was almost due west of Musket, was named Rankin after the battalion commander.

The day’s operations had cost the 2nd Battalion four killed and seven wounded, and the battalion was to suffer other losses during the succeeding few days in maintaining its position,38 but the first stages of the divisional plan for the advance on Sanananda had been completed. The last possible escape route of Colonel Tsukamoto’s troops in the track junction was closed.

The 1st Battalion had meanwhile continued to attack the area between Musket and Fisk (Kano). On 10 January the 3rd Battalion, under Maj. Leonard A. Wing,

reached the front with Brigadier Wootten’s last 400 replacements. Cpl. Paul H. Knight, a member of the regimental Antitank Company, noticed that the enemy was not firing from the smaller perimeter east of the track. Reconnoitering the position on his own initiative, he discovered that the enemy had for some unaccountable reason abandoned it. Colonel Doe lost no time in exploiting the windfall. A platoon of Company A took over the position immediately, and it was joined there the next morning by the rest of the company. Company K took Company A’s place on the supply trail, and Companies I, L, and M moved forward to Musket to relieve Company B, which went into reserve.

The Japanese left behind considerable material when they evacuated the perimeter. Included were a water-cooled, .50-caliber machine gun, two mortars, some hand grenades, a quantity of small arms ammunition, and a cache of rifles. The enemy troops had obviously been very hungry when they abandoned the perimeter, and there was gruesome evidence that some of them had been reduced to cannibalism.39

The Attack on the Track Junction

Satisfied by this time that the tactical situation no longer required his presence, General MacArthur returned to Brisbane on 8 January,40 and General Blamey followed him there several days later. Upon General Blamey’s return to Australia, General Herring again became commander of New Guinea Force and returned to Port Moresby on 11 January. Two days later, General Eichelberger took command of all Australian and American troops at the front as Commander, Advance New Guinea Force, and General Berryman became his chief of staff.41

On the 11th, two days after the establishment of Rankin, Brigadier Wootten called a conference of his subordinate commanders to discuss his plan for the reduction next day of the area south of Musket. The discussion revealed that artillery would be of only limited usefulness because the Australian front line was by this time within fifty yards of the enemy. The main reliance therefore would have to be on armor even though, because of the marshy nature of the terrain, the tanks would have to attack straight up the M.T. Road.

As finally put down on paper the same day, the plan of attack called for the 2/9 Battalion to attack on the right and the 2/12

General MacArthur with General Kenney arriving in Australia from New Guinea, 8 January 1943

Battalion, its left flank anchored on the M.T. Road, to attack on the left. They were to be supported by the mortars of both battalions, brigaded together. Supported by a company of the 2/10 Battalion, the 2/9th would move off to the northeast, circle the enemy’s left flank, and try to come in behind the track junction. The main attack would be generally to the right of the M.T. Road. It would be launched by the 2/12 Battalion, a company of the 2/10 Battalion, and three of the four available tanks. The 2/7 Cavalry and the remaining two companies of the 2/10 Battalion would be in reserve to the left and rear of the 2/12 Battalion, ready to go in at a moment’s notice. The troops at Musket would lend direct support to the operations of the 2/9 Battalion on the right, and those at Rankin would aid operations generally by exerting pressure to the south on the enemy’s right rear.42

At 0800 the next morning, while the 163rd Infantry executed feints from Musket and Rankin, the two battalions of the 18th Brigade attacked the Japanese positions

covering the junction. After a heavy artillery concentration from south and east, principally on the enemy’s rear areas, the 2/9 Battalion moved off to the northeast on a two-company front, with Company K, 163rd Infantry, covering its right flank. The 2/12 Battalion, with one company and three tanks on the road, and two companies to the right of the road, moved off on the left. Preceded by the tanks, the company on the road attacked straight up the track, and the companies on the right, which were a short distance forward, attacked obliquely toward the road.

The tank attack miscarried. It had been assumed in drawing up the plan that the tanks would receive no antitank fire, since the Japanese had fired neither field guns nor antitank guns on this front since 23 December. The assumption was a mistake. Colonel Tsukamoto had not only mined the road but he also had some antitank shells that he apparently had been hoarding for just such an emergency. As the tanks advanced up the narrow road in column, a 3-inch antitank shell pierced the leading tank and destroyed its radio set. The troop commander, who was inside, got the tank off the road but was unable to warn the tanks behind him that they were facing short-range antitank fire. As a result, each of the other two tanks was hit as it came forward. The first tank bogged down when it left the road but managed finally to withdraw. The second tank went out of control when hit and, after careening wildly along the track, was finally knocked out by the Japanese. The third tank, though disabled by both antitank shells and land mines, was subsequently recovered.

Left without tank support, the 2/12 Battalion nonetheless fought on doggedly, killing a great many Japanese and reducing a number of enemy positions. The little ground that it gained, however, was mostly on the right side of the road. The 2/9 Battalion on the right flank met less opposition and gained more ground, but it still faced a number of unreduced enemy positions at the end of the day.43

Though the 18th Brigade had lost 142 men in the day’s fighting—34 killed, 66 wounded, and 51 missing (some of whom were later recovered)—the Japanese line, as far as could be ascertained, was intact. General Eichelberger reported the prevailing feeling to General MacArthur that night when he wrote: “The attack on that darned area was not successful. The advance went through where there were no Japanese and bogged down where the Japanese were.”44

The next morning, at General Vasey’s request, General Eichelberger flew across the river to see what could be done. He reported the situation to General Herring that night as follows:–

It had been my intention to move down to your old headquarters today but General Vasey after an attack yesterday wanted to discuss his plans so I decided to go over there instead. General Vasey, General Berryman and Brigadier Wootten are all agreed that any more all-out attacks on that Japanese area will be abortive. The best plan would seem to be to surround the area and cut off all supplies, accompanied by plenty of mortar fire and constant harassing. This seemed to me very slow work, but I realize that any other decision may result in tremendous loss of personnel without commensurate gains. For the immediate present, I have asked General Vasey to have a survey made to see if it is possible for troops to live in these swamps.

The Japanese naturally have settled on the only high sandy ground.45

The Allies had misread the situation. The attack of 12 January had succeeded better than they realized. There were still plenty of unreduced bunkers standing which appeared to be even stronger and better camouflaged than those at Buna,46 but the enemy had had enough. Surrounded, his supply line completely cut, Colonel Tsukamoto had already ordered his troops to begin evacuating the track junction area.47

Tokyo Decides To Withdraw

General Yamagata’s Position

Despite the fact that they were still fighting hard, and had up to this point succeeded in imposing a stalemate on the Sanananda front, the situation of the Japanese there was hopeless. They had worked hard to establish a base at the mouth of the Mambare to supply Giruwa, using submarines and high-speed launches, but the vigilance of the coast watchers and the air force had defeated the plan. The result for the Japanese was catastrophic. General Yamagata had some 5,000 troops at the beachhead (including the sick and wounded), but the men had almost nothing to eat and every Japanese in the area faced death by starvation.48

The food situation could not have been more critical. The standard daily issue of rice to Japanese troops at this time was about twenty-eight ounces. At the end of December the ration on the Sanananda front was ten ounces. It was down to two ounces by the first week in January. By 12 January there was no rice left for issue to the troops.49

The Japanese were not only starving, they were critically short of medicine and medical supplies. At the hospital at Giruwa there had been no medicine for over a month, the wards were under water, and nearly all the medical personnel were either dead or themselves patients. The troops were short of rifles, hand grenades, and rifle grenades, and mortar shells and rifle ammunition were being strictly rationed, since stocks of both had already begun to run out.50

Upon his arrival at Giruwa on 22 December General Oda had professed great optimism about the future. He told the troops that they would be reinforced in good time and assured them that, whatever else happened, the homeland would never let Giruwa fall.51 General Yamagata had been under no such illusions about the situation. In an operations order which he issued while still at the Amboga River, he wrote, “It appears we are now in the final stages.”52 He was right, and Tokyo by that time was of the same opinion.

The Orders of 4 and 13 January

Things had gone as badly for the Japanese on Guadalcanal. The main difficulty there as on the New Guinea front was supply. After preliminary discussion of the matter in late December, Imperial General

Headquarters decided on 4 January that, because of a critical lack of shipping and the virtual impossibility of supplying either Guadalcanal or Buna effectively, all thoughts of recapturing the one or holding the other would have to be abandoned. It gave orders therefore that the forces on Guadalcanal would evacuate the island gradually by night and take up defensive positions in the northern Solomons. The troops at Sanananda and Giruwa, in turn, would be evacuated to Lae and Salamaua after fresh troops from Rabaul reinforced the latter two points.53

The orders of 4 January were immediately transmitted to the 8th Area Army at Rabaul. Its commander, General Imamura, left the timing and the manner of withdrawal at Buna to General Adachi. A 51st Division unit, the 102nd Infantry, Reinforced, was already on board ship waiting to move to Lae, and General Adachi ordered it forward at once. The ships left Rabaul the next day and, despite determined attempts by the air force to stop them, reached Lae safely on the 7th.54

General Adachi Finally Orders the Withdrawal

Five days went by without orders from General Adachi. On 12 January, the day that the broken remnants of Colonel Tsukamoto’s troops began evacuating the track junction, General Oda, from his headquarters at Sanananda Village, sent the chief of staff of the 18th Army an urgent message.

Most of the men [Oda wrote] are stricken with dysentery. Those not ... in bed with illness are without food and too weak for hand-to-hand fighting. ... Starvation is taking many lives, and it is weakening our already extended lines. We are doomed. In several days, we are bound to meet the same fate that overtook Basabua and Buna. ... Our duty will have been accomplished if we fight and lay down our lives here on the field. However, [since] this would mean that our foothold in [eastern] New Guinea would be lost and the sacrifices of our fellow soldiers during the past six months will have been in vain ... [I] urge that reinforcements be landed near Gona at once.55

The next day General Adachi finally gave General Yamagata permission to begin evacuating Sanananda and Giruwa. According to a plan drawn by Adachi himself, the troops would withdraw to the mouths of the Kumusi and Mambare Rivers, and from there they would either march or be taken by sea to Lae and Salamaua. As many of the troops as possible would be evacuated in motor launches, but the rest would have to make their way westward to the Japanese-held area on the other side of Gona by slipping through the Allied lines. Evacuation by launch of the sick and wounded would begin at once and would continue nightly until those not in

condition to fight were completely evacuated. Because of the favorable moon, the attempt to reach the area west of Gona overland would begin on 25 January and be completed by the 29th.56 How Sanananda and Giruwa were to be held until the 25th in the desperate circumstances outlined by General Oda in his message of the 12th was not made clear.

The Clean-up South of Musket

After the supposed failure of the attack on 12 January, General Vasey, on General Eichelberger’s suggestion, ordered intensive patrolling of the entire track junction area. The 2/9 and 2/12 Battalions kept the Japanese positions to their front under steady pressure, and the 163rd Infantry at Musket sent patrols south to find out how far north the enemy positions in the junction extended, an endeavor which was to be richly rewarded.

On the 14th, shortly after daybreak, a 163rd Infantry patrol came upon a sick Japanese lying in some bushes just south of Musket. Taken prisoner and interrogated, the Japanese revealed that the orders of the 12th had called for the withdrawal of all able-bodied troops from the junction area. He had left with the rest, he told his captors, but had been too sick to keep up and had collapsed on the trail.57

That was all General Vasey needed to know. He immediately ordered the 18th Brigade to launch a general offensive and the 163rd Infantry to send all available troops southward to block off all possible escape routes along the M.T. Road and the Killerton trail. Company K, 163rd Infantry, which had been operating to the east of the road on the right flank of the 2/9 Battalion, was joined by Company B from Musket, and the two companies moved southward along the M.T. Road to meet the oncoming Australians. On the Killerton trail Companies E and G moved out of Rankin. Aided by Hanson Troop and the battalion’s mortars, the units led by Major Rankin, the battalion commander, reduced the three enemy perimeters on their southern flank. At least a hundred Japanese were killed in the attack, many of them apparently escapees from the track junction. Machine guns, rifles, and ammunition were the principal booty taken.58

The 18th Brigade, with the 2/7 Cavalry under its command, made short work of the Japanese who were still to be found in the track junction area. By early afternoon the Australian troops had swept completely through the area and had joined hands with the 163rd Infantry units on both the M.T. Road and the Killerton track. Enemy equipment taken by the Australians included a 3 inch antiaircraft gun, six grenade launchers, forty machine guns (including thirteen Brens), 120 rifles (thirty of them Australian 303’s), and a quantity of hand grenades, but their bag of the enemy was small—152 Japanese killed and six prisoners of war.59

It was clear by this time that the Australians had really won the victory two days before. The dramatic way in which the situation had changed on the 14th did not escape General Eichelberger. He wrote to General Sutherland the next day:

The day before yesterday I went over to Sanananda at General Vasey’s request, accompanied by Berryman. Wootten and all were certain it was impossible to take out the Japanese pocket by direct attack and recommended that we surround the area and hammer it to pieces as well as starve the Japanese out. The only decision I made was that the whole area be patrolled with a view to finding out the condition of the swamps, etc. These patrols ran into signs the Japanese were evacuating the pocket and an attack was ordered. As a result a lot of Japanese were killed and a lot of valuable material captured.

Today, all is optimism. Vasey, from pessimism, has changed 100% and he now feels the Japanese have gotten out. Berryman and I are not at all sure. ... Nevertheless the elimination of the pocket has improved the situation immeasurably.60

It had indeed. The way was clear at last for the general advance on Sanananda.