Chapter 18: The Final Offensive

With the clearing of the area south of Musket, the fighting on the Sanananda front entered its last phase. The Japanese were about to be enveloped by the 18th Brigade, the 163rd Infantry, and the 127th Infantry from the west, the south, and the east. The end could not be far off.

The Three-Way Push

The Preparations in General Vasey’s Area

On the evening of 14 January the mop up in the track junction was turned over to the 2/7 Cavalry and the 39 and 49 Battalions, and the 18th Brigade began moving to Rankin, the 2/10 Battalion leading. After spending the night in the area, the troops passed through Rankin and moved up to a coconut plantation a mile and a half north. One company of 2/12 Battalion thereupon moved to secure a track junction 500 yards east of the plantation, the 2/9 Battalion and the rest of the 2/12 Battalion went into bivouac in the plantation area, and the 2/10 Battalion and brigade headquarters moved a mile and a quarter farther north where they secured a track junction about 900 yards from the coast. Toward evening the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, took over the junction east of the plantation secured earlier by the 2/12 Battalion, and Company B of the 2/10 Battalion began moving east to occupy Killerton Village, about 1,000 yards south of Cape Killerton.1 (Map 17)

No opposition had been met during the day, and the brigade was now poised to move on Cape Killerton, Wye Point, and Sanananda. It could attack south to the M.T. Road from Killerton Village, and north to the coast from the village and the junction secured by the 2/10 Battalion. The 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, was also in position and was preparing to attack eastward toward the M.T. Road as the rest of the 163rd Infantry attacked northward from Fisk.2

The 163rd Infantry at Musket and Fisk also had progress to report at the end of the day. The alertness of Company A, which had been operating out of the captured perimeter between Musket and Fisk, was largely responsible for the day’s successes. At 0730 that morning a platoon of the company crossed the M.T. Road and sneaked into the large Japanese perimeter on the other side from the north without being detected by its defenders. Under the company commander, 1st Lt. Howard McKinney,

the rest of the company moved in at once and began to attack. The perimeter, about 300 yards long and 150 wide, consisted of a labyrinth of interconnected bunkers and fire trenches, and the enemy, though taken by surprise, resisted fiercely. Colonel Doe lost no time in ordering a platoon of Company C from Fisk to attack the perimeter from the east and Company B (which with Companies E, G, and K, had by this time completed its part in the mop-up south of Musket) to attack from the west. The encirclement was complete, but so strong was the Japanese bunker line and so desperate the Japanese defense that it quickly became apparent that the perimeter was not going to be reduced that day.3

Just before noon that day, 15 January, General Vasey came up to Colonel Doe’s command post to give him his instructions for an all-out attack the following morning on the Japanese line north of Fisk. The 2nd Battalion was already committed to the attack eastward from the coconut plantation to the M.T. Road, and Colonel Doe chose the 1st Battalion, by this time his most experienced unit, for the northward attack. The 3rd Battalion’s role would be to complete the reduction of the Japanese pocket between Musket and Fisk and to support the attack with its heavy weapons and those of the rest of the battalion massed in Musket.

The decision to use the 1st Battalion in the attack north of Fisk made it necessary for Colonel Doe to regroup. Company I took over from Company C at Moore and Fisk, and Companies K and L relieved Companies A and B and the platoon of Company C which had been working on the Japanese pocket between Musket and Fisk. For the first time since its arrival at the front, all of the 1st Battalion was under the direct control of Colonel Lindstrom, the battalion commander.4

The plan of attack was carefully drawn. Fifteen 81-mm. mortars from Musket, and the 25-pounders of the Manning and Hall Troops from the other side of the river would give support. The 2/6 Armored Regiment’s remaining two tanks would stand by southwest of Fisk to be used at Colonel Lindstrom’s discretion. After harassing artillery fire during the night and a fifteen minute preparation in the morning, the battalion would attack from the woods west of Fisk. It would envelop the enemy’s right flank and rear west of the road, effect a junction with the 2nd Battalion as it came in from the west, and move forward with it to the M.T. Road.5

The Situation on the Right

From its bridgehead on the west bank of Konombi Creek the 127th Infantry had meanwhile been patrolling toward Giruwa, which was now only a mile away. An advance under enemy fire along a track five or six feet wide over which the waves broke at high tide and inundated the mangrove swamp on the other side was no easy matter. But with the 18th Brigade and the 163rd Infantry in position for an all-out attack on 16 January the time had come for the 127th Infantry to begin moving forward again.

On 14 January General Eichelberger had put Colonel Howe, 32nd Division G-3, in

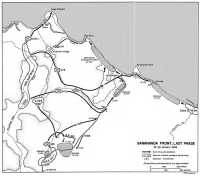

Map 17: Sanananda Front, Last Phase, 15–22 January 1943

command of Urbana Force. Colonel Grose returned to headquarters, and Boerem, now a lieutenant colonel, became Colonel Howe’s executive officer. The next day, General Eichelberger ordered Howe to begin moving on Giruwa in the morning.6

On the 15th, the day he assumed command, Howe ordered Company B to try moving up the coast. The artillery and the mortars gave the known enemy positions in the area a complete going over before the troops moved forward, but when the company was a few hundred yards out the Japanese opened up with a machine gun at almost point-blank range, killing two and wounding five. The artillery and the mortars thereupon went over the area even more carefully than before, and the company again tried to advance, only to have a second machine gun open up on it from a new position. A squad moved into the swamp to find the enemy guns and outflank them but ran into the fire of another machine gun. Another squad ordered in from another point on the track ran into such dense swamp growth that it was unable to hack its way through.

Describing the situation for Colonel Bradley over the phone that evening, Colonel Howe had this to say:–

This damn swamp up here consists of big mangrove trees, not small ones like they have in Australia, but great big ones. Their knees stick up in the air ... as much as six or eight feet above the ground, and where a big tree grows it is right on top of a clay knoll.

A man or possibly two men can ... dig in a little bit, but in no place do they have an adequate dug-in position. The rest of this area is swamp that stinks like hell. You step into it and go up to your knees. That’s the whole damn area, except for the narrow strip on the beach. I waded over the whole thing myself to make sure I saw it all. ... There is no place along that beach that would not be under water when the tide comes in. ...

To make matters worse, there seemed to be Japanese to the southward who could have got there from Sanananda only by a trail unknown to the 127th Infantry. Colonel Howe reported that one of his patrols (which the enemy tried unsuccessfully to ambush before it left the area) had discovered a whole series of Japanese defensive positions, a five-ton hoist, a small jetty, and a rubber boat along the bank of a branch stream running into Konombi Creek. In these circumstances, Howe wanted to know whether “the Old Man” still wanted “to go on with this thing.” “It will take a whole regiment,” he added, “if we do.”7

Late that night Colonel Bradley telephoned Colonel Howe that General Eichelberger was releasing the entire regiment to him except for Companies D, H, and M, the heavy weapons units, which would be left in the Buna Mission-Giropa Point area for beach defense. He told him further that, except for the remnant of the 126th Infantry which was in no circumstances to be touched, he could in an emergency count on the support of Colonel Martin’s troops as well.8

The forces for the envelopment of Sanananda were in place and the attack was ready to go. The weather, so long adverse, had finally turned favorable. The rains had stopped on the 13th, and for the first time in weeks the track was dry.9

The Troops Jump Off

The many-pronged attack was launched early on the morning of 16 January. On the left, from the track junction near the coast where he had his headquarters, Brigadier Wootten ordered Companies C and D, 2/10 Battalion, to push to the coast and turn east toward Cape Killerton and Wye Point. Company A, 2/10 Battalion, was to move east and south to a track junction a mile southeast of Killerton Village. From there it was to attack eastward toward the M.T. Road. The 2/9 and 2/12 Battalions were left for the time being in reserve.

On Colonel Doe’s front the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, pushed off toward the road from the junction east of the plantation and marched southeast to take the enemy troops north of Fisk in the rear. In the center the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry, attacked the left flank of the enemy line immediately to its front. The 3rd Battalion, operating to the rear of the 1st Battalion, continued to work

on the Japanese pocket between Musket and Fisk.

On Colonel Howe’s front the 127th Infantry moved south and west. Company I moved south to investigate the area where the chain hoist had been found the day before, and Companies A and B attacked west along the coastal track, Company A in the swamp covering Company B from the left.10

The Japanese Line Falls Apart

Companies C and D, 2/10 Battalion, reached the coast on the morning of the 16th without encountering any enemy troops. They met strong opposition, however, at a bridge over an unnamed creek just west of Cape Killerton. Brigadier Wootten thereupon ordered Company B (which had just reached Killerton Village after losing its way during the night and bivouacking a mile to the south) to advance from the village northeast to the coast. It was then to turn east and move on Wye Point. As it came out on the coast, the company ran into light opposition and scattered it. Moving east, it hit a strong line of Japanese bunkers on the beach just west of Wye Point and was held up there for the rest of the day. Company A, after a very difficult march through swamp, had meanwhile come out on the M.T. Road, about a mile south of Sanananda and a mile and a half north of the main Japanese defense line on the M.T. Road. Turning northeast toward Sanananda, it was stopped by a secondary Japanese defense line across the road.

Having now felt out the enemy, Brigadier Wootten knew what to do. The 39 Battalion was moving up from the south to cover his rearward communications, and he still had both the 2/9 and 2/12 Battalions in reserve in the plantation area. Leaving the three companies of the 2/10 Battalion on the coast to work on the opposition they had encountered near Cape Killerton and Wye Point, he ordered Colonel Arnold to move forward with his entire battalion to the M.T. Road. As soon as he reached it, he was to take Company A, 2/10 Battalion, under command and move directly on Sanananda.11

The 2/12 Battalion joined Company A on the M.T. Road the following afternoon, 17 January. Colonel Arnold attacked at once to the northeastward, but was stopped by heavy enemy opposition. The 2/10 Battalion, under Lt. Col. C. J. Geard, took both Cape Killerton and Wye Point that day. Past Wye Point it met strong opposition and was also stopped. To hasten a decision there and along the M.T. Road, Brigadier Wootten ordered the 2/9 Battalion to march cross-country from its bivouac in the plantation area to a large kunai strip about a mile and a half east. At one point this strip was only a few hundred yards from Sanananda Village. Brigadier Wootten reasoned that the Japanese, relying upon the unfavorable terrain which surrounded the strip, might not have taken the trouble to defend it. The 2/9 Battalion, under Colonel Cummings’ successor, Maj. W. N. Parry-Okeden, reached the strip that evening to find that Brigadier Wootten’s surmise had been correct. The strip was completely undefended, and all that separated the Australians from the village was a stretch of heavy swamp, no

worse than others they had already crossed.

After a difficult advance through the swamp, the battalion launched a surprise attack on Sanananda the following morning and took it by 1300. Leaving a platoon to hold Sanananda, the battalion commander ordered one company south to meet the 2/12 Battalion and pushed on eastward along the beach with the rest of his battalion. By evening the 2/9th had overrun Sanananda Point and reached the approaches to Giruwa Village. There the Japanese resistance stiffened, and advance came to a halt. Except for a 1,500-yard strip between Wye Point and Sanananda, the beach from Cape Killerton almost to the outskirts of Giruwa was in Australian hands.12

The attack of the 163rd Infantry had also gone well. Early on 16 January, after an all-night artillery harassment of the Japanese main line north of Fisk, the 1st Battalion began forming up for the attack on the west side of the road along the edge of a woods west of Fisk. Companies A and C, Lieutenant McKinney and Capt. Jack Van Duyn commanding, were abreast on an 800-yard front, and Company B (Capt. Robert M. Hamilton commanding) was immediately to the rear in battalion reserve. Company A was on the right, and its right flank was anchored on the road. Company C, on the left, extended beyond the Japanese right flank in order to get around it and come in on the Japanese rear.

The attack was well prepared. The artillery opened fire at 0845. The .30-caliber machine guns of Company D started spraying the woods and underbrush on both flanks of the battalion, while those of Company M, in place east of Fisk, began searching out the area to the south and southeast. At 0857 the fifteen 81-mm. mortars of companies D, H, and M opened up from Musket, and at 0859 the 60-mm. mortars of the 3rd Battalion, in battery south of Fisk, opened fire on the Japanese line. At 0900 the artillery and 81-mm. mortars ceased firing, and the troops moved forward. The direction was northeast, roughly parallel to the track.13

Fairly heavy fire came from the Japanese positions as the troops crawled out from the line of departure. A strongpoint on the right gave Company A a lot of trouble, especially when riflemen opened up from positions in the tall trees behind it. Light machine guns were brought up to clean out the snipers, and the crawling skirmishers advanced steadily. Company C on the left continued to move forward and around the enemy, but Company A ran into trouble as it neared the enemy strongpoint immediately to its front.

“The assault line [the company commander recalls] got within twenty yards of the Jap bunkers when it was definitely stopped by a combination of flat ground and at least four machine guns. The sun was blazing hot and the heat was terrific. The air in the small open space was dead still. The heat and nervous strain tore at everyone; two officers and eighteen men collapsed and were evacuated . . “14

Worse was in store. The troops used up all their machine gun ammunition. The Japanese tree snipers grew bolder, and it was impossible to use the mortars and artillery because the front line was too close to the Japanese positions. Colonel Lindstrom

ordered in a platoon from Company B, but it too was pinned down. By noon the situation was clearly hopeless, and Lindstrom gave the order to withdraw. There had been nine killed and seventeen wounded in the attack.15

Company C meanwhile had met only negligible opposition. Seeing that its attack was going through, Colonel Lindstrom had pushed in Company B. The two companies swept around the Japanese right flank and quickly established a perimeter 200 yards behind the Japanese line. The new position, to which the 1st Battalion moved as quickly as it could, was about 400 yards west of the road.16

The 2nd Battalion was now reaching the area with Companies F and G in the lead. Part of Company H had been left behind at trail junction east of the plantation to cover the battalion’s rear. Although the battalion had to cut its way through on a compass course when all traces of the trail it was following disappeared, it came out just south of the 1st Battalion. A patrol of Company B met it and guided it into the 1st Battalion perimeter. After a meal and a short rest, Major Rankin’s troops chopped their way east to a point on the M.T. Road about 1,000 yards behind the Japanese line, and there they made contact with the 2/12 Battalion.

Early that afternoon Companies K and L overcame the last enemy resistance in the pocket between Musket and Kano. The entire area south of Fisk was finally clear of the enemy.17

The 1st and 2nd Battalions were now north of Fisk and behind the main Japanese line. As a result, Colonel Doe was in a position to envelop the remaining enemy troops in the area from the front, flanks, and rear. He first attached Company K to the 1st Battalion to chop a supply trail from a new battalion supply point to the southwest of Fisk. Then, after seeing to it that the troops of the battalion had some rest and food, he proceeded to his task.

On 17 January patrols of Company B located the Japanese stronghold which had balked Company A the day before. The company left the 1st Battalion bivouac, moved southwest, and spent the night about 100 yards from the enemy position. In the morning the men attacked across a fifteen foot-wide, chest-high stream. In the face of heavy fire from a line of enemy bunkers on the other side of the stream, only one platoon was able to get across. The platoon knocked out one of the bunkers to its front, only to find itself up against a second line of bunkers immediately to the rear. Pinned down by heavy fire, it made no further progress that day. Patrols were sent to the left to look for an easier crossing. When they returned with a report that the double line of bunkers extended as far as the eye could see, Captain Hamilton, the company commander, ordered the company into bivouac for another try at the enemy position in the morning.

Companies A and K had moved out that morning to envelop the enemy position from the M.T. Road. While trying to reach the road, they ran into an enemy strongpoint in a road bend about 250 yards behind the Japanese line and were also halted. Company F, advancing southward along the M. T. Road from the 2nd Battalion bivouac, ran into Company K’s right flank as it began

approaching the road bend, and moved off to the left to make contact with the enemy positions on the east side of the road. The company soon encountered very strong enemy resistance and began working on it.18

The 163rd Infantry had accounted for more than 250 of the enemy since the 16th and was now in contact with the remaining Japanese positions in its area. All that remained for Colonel Doe to do was to surround and destroy them.

On Colonel Howe’s front gains on the 16th, the opening day of the advance, had been negligible. The area of the chain hoist was investigated and found to be deserted, but an attempt to move forward on Giruwa along the coastal track had made virtually no progress. Although the attack on the coastal track had been preceded by a rolling barrage of both artillery and mortar fire, the 127th Infantry had gained only a few yards in a full day’s fighting. Toward evening Companies F and G relieved Companies A and B, and plans were drawn for a stronger and better-supported attack in the morning.19

The next morning, 17 January, Companies I and K moved southward along the west bank of Konombi Creek to see whether there were Japanese beyond the place where the chain hoist had been found. Companies G and F, following the usual artillery and mortar barrage, attacked westward. Company G moved forward along the track, and Company F (as in the advance on Tarakena) covered it from the swamp on the left. The going was infinitely more difficult than on the other side of the river. The swamp was deeper and harder to cut through, and there was no spit from which enfilading fire could be put down on the enemy.

The advance did not go far that day. After Company G had gained a few yards and taken one machine gun, it was stopped by a second machine gun so cleverly sited that the troops were unable to flank it. Companies I and K, operating to the southward, had meanwhile run into an enemy outpost about fifty yards south of the chain hoist. They killed eleven ragged and horribly emaciated Japanese in the encounter.

The coastal attack was resumed on 18 January with Company G still on the right, and Company F, as before, on its left. Companies K and I were on Company F’s left rear, and an element of Company L was between K and F. The opposition had perceptibly weakened, and the two lead companies gained 300 yards that day.20 Although the fantastically difficult terrain in which the 127th Infantry was operating heavily favored the enemy, he was finally on the run on that flank too.

Finishing the Job

The Mop-up Begins

By 19 January operations had definitely entered the mop-up stage. The enemy was fighting to the death, and the opposition continued to be heavy, so heavy in fact, that the companies of the 2/10 Battalion on the coast west of Sanananda and of the 2/9 Battalion on the eastern outskirts of Giruwa were held up that day and the day

following.21 The 2/12 Battalion and the company of the 2/9 Battalion that had been working from south and north on the enemy position immediately south of Sanananda were more fortunate. They managed to make contact west of the road on the afternoon on the 19th, although the job was accomplished, as the historian of the 18th Brigade notes, “under the most miserable conditions, the troops ... never being out of the water and frequently remaining for hours in the water up to their waist.”22 There was still opposition in the area east of the road, and the next day was devoted to reducing it. At nightfall on 20 January the task was almost complete, and Brigadier Wootten had already ordered Colonel Arnold to move north as soon as the last organized enemy opposition in the area was overcome.23

Colonel Doe’s efforts to reduce the three remaining enemy pockets in his area were intensified on 19 January. The pockets—remnants of the Japanese main line on the M.T. Road immediately northeast of Fisk—were heavily engaged during the day. Company C moved in on the left of Company B at daybreak, and the two companies attacked the westernmost Japanese strongpoint north of the road. Company F, after advancing 250 yards since the day before, attacked the larger perimeter south of the road from the northeast. From the northwest Companies A and K continued their attack on the roadbend perimeter, a few hundred yards to the northeast of the first two.24

The plan for the reduction of the west perimeter called for Company B on the right to drive ahead from its shallow penetration of the day before and clear out the Japanese second line, while Company C on the left rolled up the first line. Preparations for the attack were thorough. The four rifle platoons and the 60-mm. mortars were linked up with sound-power telephones on a party line, and the two company commanders, Captain Hamilton of Company B and Captain Van Duyn of Company C, working closely together, took turns at the telephone and in the front lines.

As long as the stream still had to be crossed, the advantage was with the enemy. Enemy fire from the other side of the creek was again very heavy, and Company C, which attacked first, had a hard time crossing. At first, part of only one platoon, under the platoon leader, S. Sgt. John L. Mohl, managed to get across. Mohl, who had only nine men with him, moved out on the enemy bunkers at once with another enlisted man, Cpl. Wilbur H. Rummel. The two men, covered by fire from the other eight, knocked out six bunkers in quick succession, making it a comparatively easy matter for the rest of the company to cross.25 While the enemy was occupied with Company C, Company B was able to get across without undue trouble. It spent all afternoon working on the second bunker line. Just when its attack seemed on the point of going through, the Japanese pulled out of both the first and second lines into a third line immediately to the rear of the first two and once again blocked further advance.

.50-cal Browning machine gun, directed at Giruwa Point

It had turned dark by this time. Taking up a defensive bivouac in the middle of the Japanese position, the troops had their evening meal and prepared for further action in the morning.

East of the road Company F had also met heavy opposition during the morning. Finding a double line of log and dirt bunkers in its way, it called for the artillery and the 81-mm. mortars. The company commander, Capt. Conway M. Ellers, established an observation post about thirty yards from the Japanese bunker line and was joined there by Major Rankin and an Australian forward observer. The artillery and the 81-mm. mortars ranged in and at 1400 opened up on the bunkers. At 1530 the preparation ceased and the troops, who had been a short distance to the rear, attacked. They found that the artillery and mortars had done their work well. The bunkers, made of softwood logs and not so well constructed as at Buna, had been demolished, and most of the Japanese inside had been killed.

After advancing 150 yards past the Japanese bunker line, the company found itself wedged between two shoulder-deep streams with Japanese machine guns on front and flank. Five men were killed while trying to clear out one of the machine gun nests, and a flanking move by the support platoon along the bank of one of the streams failed. Because it was growing dark and the company

had nearly expended its ammunition, Major Rankin ordered Company E, Capt. James Buckland commanding, to relieve Company F. While the relief was in progress, the Japanese discovered what was going on and counterattacked, but fire from Buckland’s company drove them off.

The push of Companies A and K on the road-bend perimeter had been supported by a platoon of heavy machine guns on the right flank, and by their own light machine guns thrust out to the front. Everything went well until the advance masked the fire of the machine guns. Taking advantage of their opportunity, the Japanese counterattacked and halted the movement. From a wounded Japanese who crawled into the perimeter at dusk and gave himself up, the two company commanders, Lieutenant McKinney and 1st Lt. Allen Zimmerman, learned that they were approaching the main Japanese headquarters in the area, presumably that of Colonel Yokoyama.26

The next day, 20 January, while Companies B and C continued working on the desperately resisting Japanese in the west perimeter, and Companies A and K on those in the road bend, Company I moved up from the south and launched a strong attack on the south perimeter. Preceded by 250 rounds from the 25-pounders and 750 from the 81-mm. mortars at Musket, the attack had also the support of the machine guns of Company M at Fisk. The heavy weapons crews swept the trees and underbrush in the area thoroughly before the troops jumped off. Just as the company was about to move forward, a mortar shot killed its commander, Capt. Duncan V. Dupree, and its 1st sergeant, James W. Boland. Seconds later, enemy rifle fire killed one of the platoon leaders. The company faltered just long enough for the Japanese to leave their bunkers, get into firing position, and repulse the attack.27

The 163rd Infantry had taken heavy toll of the enemy during the preceding two days, but the latter, though encircled and cut off, were still holding their positions. It was obvious they would be unable to do so much longer.

The mop-up on the 127th Infantry’s front had gone well. At daybreak on 19 January Company E had started pushing up the beach with Company K on its left. To help Company K overcome continued heavy opposition in the swamp, a .50-caliber machine gun was brought up. It proved very effective against the hastily improvised enemy positions there. The 37-mm. gun which had played so notable a part in the taking of Tarakena was also brought up. Emplaced on the beach to cover Company E’s advance, it again proved extremely effective against the enemy.

The next morning Company F joined Company E along the beach, Company C moved in on the left, and Companies I and L began moving forward on the far left. There was little opposition now. Several enemy machine guns were captured, and a number of prisoners were taken, all of them suffering from dysentery and starvation. By 1630 in the afternoon the Americans were in sight of Giruwa and could see the Australians moving forward along the coastal track on the other side of the village.28

General Yamagata Gets Out in Time

By the 18th General Yamagata, with the Sanananda front collapsing about his ears,29 had seen enough to convince him that his troops could not wait until the 25th to abandon their positions and try to make their way westward through the Allied lines as General Adachi had ordered five days before. He therefore drew up orders at noon on the 18th which advanced the withdrawal five days: from 2000 hours, 25 January, to 2000 hours, 20 January. After slipping through the Allied lines, his troops were to assemble near Bakumbari, a point about seven miles north of Gona, where boats would be waiting to take them to safety. General Yamagata, his staff, and his headquarters would leave the area by motor launch on 19 January—X minus 1.30

Early on 19 January Yamagata handed the orders personally to General Oda, who was holding the western approaches to Giruwa, and one of his staff officers delivered them personally to Colonel Yazawa, who was in command of operations east of Giruwa. The orders were sealed, and the two commanders (apparently for morale reasons) were instructed not to open them until 1600. At 2130 Yamagata, his staff, a section of his headquarters, and 140 sick and wounded left for the mouth of the Kumusi in two large motor launches. Though bombed on the way, they arrived safely at their destination at 0230 the next morning.31

That night several Japanese motor boats tried to put in at Giruwa in order to take off all remaining communications equipment and as many as possible of the sick and wounded. Allied artillery drove them off. At the same time General Oda, Colonel Yazawa, and an unknown number of their troops abandoned their positions, east and west of Giruwa and took to the swamp, trying to escape toward Bakumbari as their orders bade them. Some got through, but Oda and Yazawa did not. Both were killed the same night when they apparently ran into Australian outposts that stood in the way.32

The End at Last

Along the M.T. Road immediately south of Sanananda, the 2/12 Battalion overcame the last vestiges of enemy opposition in the area. Relieved by the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, early on 21 January, Colonel Arnold moved north to take over the Sanananda Point-Giruwa area from the 2/9 Battalion. The relief was completed that afternoon, and the 2/9 Battalion moved out against the Japanese pocket west of Sanananda which had so long held back the 2/10 Battalion.

There was to be a three-way envelopment of the pocket. Two companies of the 2/10 Battalion would attack from the northwest, the 2/9 Battalion would attack from the southeast, and Company C of the 2/10 Battalion would attack from the top of the large kunai strip west of Sanananda, and take the Japanese in the center. The Australians moved out that afternoon. They met surprisingly little opposition, and only one man was wounded in the day’s fighting. At the end of the day a single enemy pocket remained. It was quickly reduced the next morning with the help of artillery fire from Hanson Troop. The three attacking forces made contact along the beach at 1315, a meeting that marked the end of organized resistance in the area. More than 200 Japanese had been killed in the two-day attack.33 The enemy position west of Sanananda had finally been reduced.

The reduction of Giruwa was also to prove an easy task. Companies E, C, and A, 127th Infantry, pushed forward along the coastal track early on 21 January with Company E leading. They found the terrain much better now; the track was broader, and there was less swamp. The enemy was no longer trying to hold, and only scattered rifle fire was met. At 1230 Company E, under Lieutenant Fraser, swept through Giruwa Village, meeting virtually no opposition. Forty-five minutes later Fraser and his company joined the Australians on the east bank of the Giruwa lagoon. Soon after, a patrol of Company E, exploring the area just east of Giruwa, came upon what was left of the 67th Line of Communications Hospital. The scene was a grisly one. Sick and wounded were scattered through the area, a large number of them in the last stages of starvation. There were many unburied dead, and what the patrol described as “several skeletons walking around.” There was evidence too that some of the enemy had been practicing cannibalism. Even in this extremity, the Japanese fought back. Twenty were killed in the hospital area resisting capture; sixty-nine others, too helpless to resist, were taken prisoner.

The Japanese tried to land boats at Giruwa during the night and were again driven off by the artillery. The fighting came to an end early the next morning when the troops mopped up the last resisting Japanese in the area. Giruwa, the main Japanese headquarters west of the river, had fallen after only token resistance.34

The heaviest fighting of all developed on the 163rd Infantry front where the bulk of the enemy troops still left at the beachhead were penned in. As at Giruwa and the pocket west of Sanananda, the climactic day was the 21st. Colonel Doe was in at the kill, personally directing operations from an exposed position in the front line.35 The attacks that morning went off well. At 1015, after Companies A and K pulled back 150 yards, the

artillery began firing on the last Japanese bunker line in the road-bend perimeter. When the artillery barrage ceased at 1030, the massed 81-mm. mortars at Musket supplemented by the machine guns, began firing on the position. Five minutes later, just as the last mortar salvo was fired, Companies A and K attacked. Covered by their own assault fire, they caught most of the Japanese still in their shelters or trying to get out of them. The Japanese were killed in droves, and the perimeter was quickly overrun. Company A on the right fanned out and lent some of its fire power to Companies B and C, which were still working on the west perimeter. Feeling the pressure ease, Companies B and C surged forward and quickly cleaned out the enemy position. All four companies thereupon moved south to the M.T. Road, where Companies B and K, the one wheeling right and the other left, joined forces and completed the mop-up. More than 500 enemy dead were counted at the end of the day, the largest single day’s destruction of the enemy since Gorari. The 163rd Infantry lost one killed and six wounded.

That same day, 1st Lt. John R. Jacobucci, S-2 of the 3rd Battalion, personally located the main enemy strongpoint in the east perimeter after several patrols failed to do so. The next morning at 1047, Companies I and L, 1st Lt. Loren E. O’Dell and Capt. Edward L. Reams commanding, attacked the perimeter from the south, concentrating on the strongpoint that Jacobucci had discovered. As before, the troops went in on the run behind the last mortar salvo and again caught the Japanese still in their holes or trying to leave them. The position was overrun by 1152, and the mop-up was completed by 1300 with the help of Company E, which had been at the northeast end of the perimeter supporting the attack by fire. This attack marked the end of all organized resistance on the M.T. Road. By evening the mop-up on either side of the road was complete.36 Giruwa and the Japanese pocket west of Sanananda had already been reduced some hours before. The 18th Brigade and the 127th and 163rd Infantry Regiments had suffered 828 casualties since being committed to the Sanananda front,37 but they had finished the job. The Papuan Campaign was over, six months to the day after it had begun.

The Victory at Sanananda

The Cost to the Enemy

The 18th Brigade, the 127th Infantry, and the 163rd Infantry at Sanananda, and the 14th Brigade at Gona, captured a great deal of enemy matériel, including rifles, machine guns, mortars, antitank guns, land mines, radio transmitters, signal equipment, medical supplies, tools of all kinds, and a dozen motor vehicles, some with U.S. Army markings. They buried 1,993 of the enemy,

Dobodura Airstrip. 41st Division troops arriving from Port Moresby, 4 February 1943

and took more than 200 prisoners, including 159 Japanese.38

The final count of enemy dead in General Vasey’s area since the beginning of operations was 2,537—959 of them killed at Gona and in the area west of Gona.39 The victory however, was not as complete as could be desired, for a great many of the enemy’s able-bodied troops escaped, leaving mostly sick and wounded behind. General Willoughby may have suspected as much when he wrote that the count of enemy dead at Sanananda could not be considered “a true count of effective enemy strength” since it

Dobodura Airstrip. 32nd Division troops departing for Port Moresby, 4 February 1943

included many “sick and wounded who were killed.”40

The Australians on the ground, especially at Gona, realized that Japanese troops in considerable numbers were slipping past them. Because of the thick and tangled jungle terrain, they were able to intercept only a portion of them. The Australians estimated at the time that about 700 Japanese had succeeded in getting through their lines,41 but the actual figure was far higher. A total of 1,190 enemy sick and wounded were evacuated by sea between 13 and 20 January, and by the end of the month about 1,000 able-bodied Japanese succeeded in filtering through the Allied lines and reaching safety on the other side of Gona.42

The Allied Cost

The cost of the victory had not been light. The Australian troops who fought on the Sanananda side of the river—the 2/7 Cavalry, and the 14th, 16th, 18th, 21st, 25th, and 30th Brigades—sustained some 2,700 casualties.43 The American units on this

front—the 127th Infantry, the 163rd Infantry, and the detachment of the 126th Infantry—suffered 798.44 The casualties incurred in clearing the 7th Division area were thus about 3,500, roughly 700 more than at Buna.

The 41st Division Takes Over

With the campaign at an end, the time had come to relieve the worn-out troops of the 7th and 32nd Divisions, some of whom had been in the area since early November. The 41st Division, whose remaining regiments had by this time begun reaching the front, was designated for the task, and the reliefs were effected as quickly as possible.

General Fuller took over operational control of all Allied troops in the Oro Bay-Gona area on 25 January, and General Eichelberger and the I Corps staff returned to Port Moresby the same day. Eichelberger was followed there a few days later by General Berryman and a nucleus of Advance New Guinea Force which had remained behind to assist General Fuller with the reliefs.

By prior arrangement the hard-hit 126th Infantry left the combat zone on the 22nd, and relief of the remaining troops was completed by the end of the month. As air space became available, the men were flown to Port Moresby and, after a short stay, were returned to Australia by sea.45

The victory in Papua had been crushing and decisive. By the end of January all that was left of the enemy troops who had fought there were broken remnants at the mouths of the Kumusi and Mambare Rivers, whom the air force had under constant attack and against whom the 41st Division was already moving.46

It was not the only victory. On 7 February, the Japanese finished evacuating Guadalcanal. Two days later the fighting on the island came to an end, as in Papua, exactly six months after it began.47 The Japanese had been defeated all along the line. The initiative both in New Guinea and in the Solomons was finally in Allied hands.