Chapter 5: CARTWHEEL Begins: The Southwest Pacific

On 30 June 1943—D Day for CARTWHEEL—Allied air, sea, and ground forces facing the Japanese from New Guinea to the Solomons were ready to attack. The Japanese were expecting the offensive but did not know just when or where it would come. And the Allies had determined to compound their uncertainty by launching not one, but three invasions—in New Georgia, at Woodlark and Kiriwina, and at Nassau Bay in New Guinea in preparation for the Markham Valley–Lae–Salamaua operations.

CHRONICLE

Plans and Preparations

Planning for the seizure of Woodlark and Kiriwina (designated Operation CHRONICLE) had started at General Krueger’s Sixth Army headquarters near Brisbane in early May. General MacArthur had directed Allied Air and Naval Forces to support ALAMO Force and had made Krueger responsible for the coordination of ground, air, and naval planning.1 Krueger, Kenney, Carpender, Barbey, and staff and liaison officers participated. Krueger’s authority to coordinate planning gave him a preeminent position; he was first among equals.

Planning had not proceeded far before a hitch developed. When Admiral Halsey suggested the seizure of Woodlark and Kiriwina he offered to provide part of the invasion force, an offer that had been cheerfully accepted. Thus in midmonth Generals Harmon and Twining and Vice Adm. Aubrey W. Fitch, who commanded all South Pacific aircraft, flew to Brisbane to discuss details of the transfer of forces to the Southwest Pacific. On the way over from Nouméa Harmon and Twining made an air reconnaissance of Woodlark, and on arriving at Brisbane offered their opinion that Woodlark would be of little use in providing air support for the South Pacific’s invasion of southern Bougainville. But Kenney, Carpender, Brig. Gen. Stephen J. Chamberlin, G-3 of GHQ, and Brig. Gen. Hugh J. Casey, the chief engineer of GHQ, explained how difficult it would be for Kenney’s aircraft to support that invasion without the additional airfield that Woodlark would provide. The South Pacific representatives

Map 5: Operation CHRONICLE Area, 30 June 1943

then agreed to go on with the operation, and the details whereby ground force units, a fighter squadron, naval construction units, and six motor torpedo boats would be transferred, and destroyer-transports (APDs) and tank landing ships (LSTs) would be lent to the Southwest Pacific, were arranged.2

The invasion of the two islands was the first real amphibious movement undertaken in MacArthur’s area. Planning was so thorough and comprehensive that the plans for movement of troops, supplies, and equipment in amphibious shipping became standing operating procedure for future invasions.

Kiriwina, a narrow, north-south island twenty-five miles long, lies within fighter and medium bomber range of Rabaul, Buin in southern Bougainville, and Lae, and 60 miles from the nearest Allied base at Goodenough Island in the D’Entrecasteaux group. From Rabaul to 44-mile-long Woodlark is 300 nautical miles, from Buin 225, from Lae 380, and from Goodenough 160. Neither island was occupied by the Japanese. (Map 5)

MacArthur had ordered Allied Naval Forces to support the ALAMO Force by carrying troops and supplies, destroying Japanese forces, and protecting the lines

Brig. Gen. Nathan F. Twining, left, Lt. Gen. Millard F. Harmon, and Col. Glen C. Jamison examining a map of the South Pacific area. Photograph taken October 1942

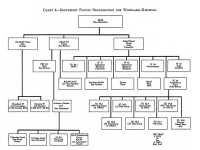

of communication. To carry out these orders Admiral Carpender organized several task forces of which the most important were Task Forces 74 and 76. (Chart 4) The first, commanded by Rear Adm. V. A. C. Crutchley, RN, and consisting of Australian and American cruisers and destroyers, was to destroy enemy ships in the Coral and Arafura Seas and be prepared to cooperate with South Pacific forces in the event of a major Japanese naval offensive. Task Force 76 was the Amphibious Force which had been organized in January 1943 under Admiral Barbey. Barbey’s ships—4 APDs, 4 APCs, 12 LSTs, 18 LCIs, and 18 LCTs with 10 destroyers, 8 subchasers, 4 minesweepers and 1 tug as escort—would transport and land the attacking troops. As ships at Kiriwina would be vulnerable to submarine attack, Barbey assigned 4 destroyers to cover Kiriwina until all defenses were in, and ordered PT boats to patrol at each island.3

Kenney’s orders directed Air Vice Marshal Bostock’s Royal Australian Air

Southwest Pacific Organization for Woodlark–Kiriwina

Force Command to protect the lines of communication along the east coast of Australia and to support the defense of forward bases, but assigned the support of the Woodlark–Kiriwina operation to the Fifth Air Force as a primary mission. The V Bomber Command, under Col. Roger M. Ramey, was to attempt the destruction of Japanese air power at Rabaul, using one heavy bomb group nightly from 25 through 30 June, weather permitting, and to attack Japanese ships, continue its reconnaissance missions, provide antisubmarine patrols during daylight within two hundred miles of the Allied bases in New Guinea, and render close support to the ground troops as needed. Since there were no Japanese on the islands support bombardment was not necessary. To Brig. Gen. Paul B. Wurtsmith’s V Fighter Command went the main burden of providing fighter escort and cover for convoys and landing operations from the airfields at Dobodura, Port Moresby, and Goodenough Island. Wurtsmith was also directed to be prepared to station fighters on Woodlark and Kiriwina once the airstrips were ready.

The 1st Air Task Force and No. 9 Operational Group of the RAAF, respectively commanded by Col. Frederic H. Smith and Air Commodore J. E. Hewitt, were ordered to destroy Japanese ships and aircraft threatening the operation, and to provide antisubmarine escort and reconnaissance. No fighter umbrella was provided for the convoys, a lack which the naval commanders protested vigorously but unsuccessfully. Fighter squadrons were maintained on ground alert at Dobodura, Milne Bay, and Goodenough Island, ready to fly if hostile aircraft attacked the shipping.4

The 112th Cavalry Regiment, Col. Julian W. Cunningham commanding, and the 158th Infantry, a separate regiment led by Col. J. Prugh Herndon, plus substantial supporting arms and services, had been allotted to the ALAMO Force. Krueger organized the troops that had come from the South Pacific—the 112th Cavalry (a dismounted two-squadron unit serving as infantry), the 134th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers), the 12th Marine Defense Battalion, plus quartermaster, port, ordnance, medical, and engineer units, a naval base unit and a construction battalion—into the Woodlark Task Force and ordered it to seize and defend Woodlark and build an airfield.5 The Kiriwina Task Force, under Herndon’s command, consisted of the 158th Infantry (less the 2nd Battalion),

the 148th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers), plus additional 155-mm. gun units and engineer, ordnance, medical, antiaircraft, and quartermaster troops. It was to capture and hold Kiriwina and construct an airdrome. The first echelon of the Woodlark Force would be carried on 6 APDs, 6 LCIs, and 6 LSTs, that of the Kiriwina Force on 2 APDs and 12 LCIs.6

Doctrine regarding unity of command and the passage of command from ground to naval officers on embarkation, and back to ground officers on landing, was not clearly set forth in the plans. For the relationship between naval and ground commanders, the principle of unity of command rather than cooperation seems to have been followed, but it would have been sounder to have prescribed the exact command relationships in the orders.

In contrast with the practice of the South Pacific Area, where naval doctrine prevailed, no air units were placed under naval or ground commanders. The ultimate authority common to air, naval, and ground units was GHQ itself. Air liaison and support parties, however, were set up at ALAMO Force headquarters and at Dobodura.

Krueger from the first had planned to establish ALAMO headquarters at Milne Bay. When reconnaissance showed that development of the bay into a satisfactory base would constitute a sizable operation, he and his staff pitched in to do the job.

Assembly of the invasion force was complicated by the fact that the Kiriwina Force was scattered from Port Moresby to Australia. (The Woodlark Force had come virtually intact from the South Pacific, and was, except for naval and air elements, concentrated at Townsville). Movement schedules were carefully worked out, and the first elements of the Kiriwina Force reached their staging area at Milne Bay in early June. It was soon apparent that assembly of the forces could not be completed before the third week in June. For this reason D Day for CHRONICLE, which would also be D Day for Nassau Bay and New Georgia, had been set for 30 June.7

On 20 June Krueger’s ALAMO headquarters opened at Milne Bay, and MacArthur and Barbey arrived shortly afterward. Within a few days all elements of Herndon’s Kiriwina Force reached the bay. Final training of this regimental combat team in loading and unloading landing craft and in beach organization was inhibited by the necessity for unloading ships and developing the base. On the other hand the 112th Cavalrymen at Townsville were able to make good use of the opportunity to train uninterruptedly. Barbey’s amphibious force, Task Force 76, was also able to train effectively, an activity that had begun in early May.8

At Townsville and Milne Bay, soldiers and sailors marked “loading slots” or

deck-plan layouts of LSTs and LCTs on the beaches with tape, then assembled loads in the slots to test the cargo space allotted against the cargo assigned. All units agreed the technique worked very well.

During the last days of June bad weather prevented the planned air attacks against Rabaul, but B-25s and A-20s made about seventy sorties against Lae and Salamaua. On 30 June the weather cleared and eight B-17s and three B-24s attacked Vunakanau airstrip at Rabaul. Bombing on this small scale, which was all the resources in the area would permit, continued for the next few days while the ground troops consolidated themselves at Woodlark and Kiriwina.9

The Advance Parties

In early May two small engineer reconnaissance parties headed by the Sixth Army’s deputy engineer had slipped ashore on Woodlark and Kiriwina to gather data on airfield sites, beach conditions, and defense positions.10 Their reports, coupled with the fact that there were no Japanese troops present, indicated that it would be advisable and possible to send in parties to prepare beaches and roads in advance of the main landings. Thus CHRONICLE was unusual among amphibious operations, for the shore party landed ahead of the assault troops.

At 0400, 21 June, the APDs Brooks and Humphreys left Townsville carrying almost two hundred men of the 112th Cavalry. They stopped at Milne Bay to pick up more men the next day, and at 1600 left Milne Bay at high speed to make the night run to Woodlark. The trip was timed to keep the ships within range of fighter cover until dusk on the outgoing trip, and after dawn on the return voyage. The APDs reached Woodlark without incident, and at 0032 of 23 June the advance party, under Maj. D. M. McMains, started landing at Guasopa Harbor in six LCP(R)s. Rough seas and high winds slowed the landings, which were not completed until 0400, when the APDs shoved off for Milne Bay.

The Australian coastwatcher had not been informed before the landing. When told that troops were coming ashore he formed his native guerrillas in skirmish line and got ready to fight. Fortunately before anything tragic happened he heard the invaders speaking the American variety of English and joined them.

The Brooks and Humphreys reached Milne Bay during daylight of 23 June and took aboard the 158th Regimental Combat Team’s shore party, a part of the 59th Combat Engineer Company and the 158th Infantry’s communication platoon, under command of Lt. Col. Floyd G. Powell. Departing Milne Bay at 1810,

four hours behind schedule, they reached Kiriwina at midnight.11 The island is almost entirely surrounded by a coral reef, with a five-mile-long channel winding through the reef to a 200-yard-wide beach at Losuia on the south coast of the main part of the island. Unloading of the APDs went very slowly as the LCP(R)s threaded their way through the channel. The tide was low, and the landing craft ran aground several times in the darkness. Admiral Barbey also blamed the 158th’s inadequate training for part of the delay. Daylight came before the ships were emptied; they departed with part of their loads still on board. Three nights later they returned to unload heavy communication and engineer equipment that had been left in their holds. This led Barbey to recommend that APDs carry no item of equipment that could not readily be carried by one man.

At Woodlark the advance party reconnoitered, established outposts and beach defenses, dug wells, blasted coral obstructions out of the channels, cleared trails and dispersal and bivouac areas, prepared six beaching points for LSTs, and installed signs, markers, and lights to mark channels and beaches for the main body, which would be landing in darkness to avoid Japanese air attacks. Similar efforts by the Kiriwina party were not as successful, partly because of the delay in landing engineer equipment. A good deal of effort was expended in building a coral causeway, 7 feet high and 300 yards long, across the reef on the north coast to permit a landing there. Natives aided in this work by lugging basketloads of coral.

The Japanese were unaware of, or indifferent to, the advance parties; they launched neither surface nor air attacks against them.

The Landings

About half the Woodlark Force—units of the 112th Cavalry, the 134th Field Artillery Battalion, and the 12th Marine Defense Battalion—left Townsville on 25 June aboard six LSTs, with one subchaser and two destroyers as escort. The voyage to the target was uneventful. Landing of the 2,600 troops began at 2100 of 30 June. Unloading of the LSTs at their beaching points was rapid. Cunningham’s force had borrowed extra trucks at Townsville to permit every item of equipment to be put aboard a truck which was driven aboard an LST at Townsville, then driven off at Woodlark. Emptied of their loads, the slow-moving LSTs cleared Woodlark before daylight.

Two APDs, carrying part of the Woodlark Force from Milne Bay, arrived shortly before 0100, 1 July, but encountered trouble in navigating the channel with the result that landing craft were not put into the water until 0230. The landing craft coxswains had trouble finding the right beach, but by 0600 the APDs were emptied and ready to leave. Some confusion had existed on the beach, but not enough to prevent its being cleared by the same time.

Additional echelons arrived in LCIs and LSTs on 1 July, and all these were unloaded quickly and easily. The LSTs took 310 instead of the 317 trucks,

Troops Disembarking from LCI at Kiriwina Island wade ashore, 30 June 1943

Cunningham explained, because one LST raised its bow ramp and closed its doors before all its trucks could be driven aboard.

On shore, defense positions were set up. Antiaircraft and coast artillery pieces of the 12th Defense Battalion were installed, and machine gun and 37-mm. beach positions were established. Cargo was moved inland, and work on the airfield began on 2 July.

Meanwhile Colonel Herndon’s Kiriwina Force had been landing, but without the smoothness that characterized operations at Woodlark. Shortly after dawn on 30 June, twelve LCIs, which with six escorting destroyers had sailed from Milne Bay the previous noon, began landing their 2,250 troops. Trouble accompanied the landing from the start. The LCIs had great difficulty getting through the narrow, reef-filled channel to RED Beach near Losuia. And the water shallowed near shore so much that they grounded 200-300 yards from the shoreline. The landing went slowly.12

Sunset of 30 June saw the arrival of twelve LCTs and seven LCMs which had left Milne Bay on 29 June and stopped overnight at Goodenough Island. Again there were problems. Heavy rains were falling. The tide was out. Only one LCT was able to cross a sandbar which blocked the approach to the jetty at Losuia. Other LCTs hung up on the bar and were forced to wait for the tide to float them off. The remainder made for RED Beach but grounded offshore with the result that much of the gear on board had to be hand-carried ashore. Some of the vehicles were driven ashore, but several drowned out in the salt water.

LCTs in subsequent echelons avoided some of the difficulties by landing on the north shore of Kiriwina where the coral causeway had been built. Here trucks could back right up onto the bow ramps of the LCTs, but several were damaged by sliding off the causeway.

In the absence of enemy interference Admiral Barbey approved a change in the original plan to move part of the supplies to Goodenough aboard LSTs, then transship them to LCTs for the trip to Kiriwina. After 12 July LSTs

Natives carrying luggage which had been deposited on the coral causeway, north shore of Kiriwina Island, 1 July 1943

sailed directly from Milne Bay to the north shore of Kiriwina.

Unloading on the north shore, while easier than at Losuia, complicated matters further for the troops ashore. Heavy equipment was landed some distance from the proposed airfield near Losuia. Building the necessary roads was slowed by heavy rains and lack of enough heavy engineer equipment.

Base Development

Meanwhile the construction program at Woodlark went forward. By 14 July the airfield was near enough completion to accommodate C-47s. One week later 5,200 feet of runway were surfaced with coral, and on 23 July the air garrison—the 67th Fighter Squadron which had served on Guadalcanal in the grim days of 1942—arrived for duty.

On Kiriwina heavy rains continued and added to the engineers’ troubles in building and maintaining roads. All construction equipment was used on the roads until about 10 July; during that time the airfield site was partly cleared with hand tools. General Krueger visited the island on 11 July and expressed his dissatisfaction with the progress of road and airfield construction. Three days later he placed Col. John T. Murray, formerly of the 41st Division, in command of the Kiriwina Task Force and returned Colonel Herndon to command of the 158th Infantry. Herndon had asked for more engineers and machinery. These arrived after Murray took command

Jeep and trailer leaving an LST anchored off north shore of Kiriwina Island, July 1943

and thereafter the work went faster. By D plus 20 the first airstrip, 1,500 feet long, was cleared, roughly graded, and ready for surfacing. By the month’s end the strip was 5,000 feet long and ready for coral. No. 79 Squadron of the RAAF flew in and began operations on 18 August.

Except for reconnaissance and two small bombing attacks against Woodlark, the enemy did not react to the invasions, so that Barbey was able to transport twenty echelons to Kiriwina and seven to Woodlark without losing a ship or a man. By mid-August transport of supplies and men to the two islands was no longer a tactical mission. U.S. Army Services of Supply was ready to relieve Barbey of logistical responsibility.

Thus the Southwest Pacific Area, using small forces, was able to secure two more airfields to further the Allies’ control over the Solomon Sea.

Nassau Bay

Plans and Preparations

The invasion of Nassau Bay was designed to ease the problem of supplying the troops that were to attack Salamaua and Lae. They could not be wholly supplied by ship, by landing craft, by airplane, or by land. The threat of Japanese air attacks in the restricted waters of Huon Gulf and Vitiaz Strait, coupled with the prevailing shortage of troop and cargo ships, rendered the use of large ships impractical if not impossible. The

Clearing airfield site with hand tools, Kiriwina Island, July 1943

shortage of landing craft and the distance limited the extent of any shore-to shore operations. The Australian troops operating out of Wau against Salamaua were still being supplied by air, and this placed a heavy burden on Southwest Pacific air transport and limited the number of ground troops that could be employed. In order to supplement air transport the Australians had begun their road from Edie Creek at the south end of the Bulolo Valley to the headwaters of the Lakekamu River on the southwest coast of the Papuan peninsula, but the tremendous difficulties inherent in pushing roads through New Guinea mountains slowed the Australians as they had the Japanese. It was clear that the opening of the Markham Valley–Huon Peninsula campaign would be delayed beyond August if it had to await completion of the mountain highway.13

The seizure of Nassau Bay offered a possibility of at least partially solving these problems, a possibility which fitted neatly into the pattern of plans already being prepared. Nassau Bay lies less than sixty miles from Lae, or within range of the landing craft of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade which GHQ expected to employ, and it is just a short distance down the Papuan coast from Salamaua. Troops of the 3rd Australian Division were operating inland from Nassau Bay at this time. Seizure of the bay by a shore-to-shore movement from Morobe, then held by the U.S. 162nd Infantry

of the 41st Division, would provide a means by which the Australians getting ready to attack Salamaua could be supplied by water to supplement the air drops, and would also provide a staging point for the shore-to-shore movement of an entire Australian division to a point east of Lae. Therefore GHQ and New Guinea Force headquarters decided to seize Nassau Bay on the same day that Woodlark, Kiriwina, and New Georgia were invaded. The troops seizing Nassau Bay would then join forces with 3rd Australian Division and press against Salamaua in order to keep the Japanese from deducing that the Allies were planning a major assault against Lae.14

General Blamey was supposed to assume personal command of the New Guinea Force for the Markham Valley–Huon Peninsula operations but the pressure of his duties kept him in Australia until August. Pending his arrival in New Guinea Lt. Gen. E. F. Herring of the Australian Army retained command of the New Guinea Force and operated under Blamey’s headquarters instead of GHQ as originally planned. Maj. Gen. Stanley G. Savige, General Officer Commanding the 3rd Australian Division, had tactical command of the operations against Salamaua. Troops of the U.S. 162nd Regimental Combat Team, which was assigned to Nassau Bay and subsequent operations against Salamaua, would come under General Savige’s control once they were ashore.

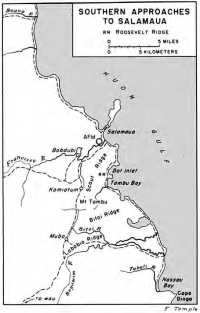

When the Australians had defeated the Japanese attempt to capture Wau, they pursued the retreating enemy out of the Bulolo Valley and down through the mountains to a point inland from Nassau Bay. In preparation for Nassau Bay and the attack on Salamaua, Savige ordered his division to push against Salamaua from the west and south. He directed the MacKechnie Force, essentially a battalion combat team of the 162nd Infantry, to make the initial landing at Nassau Bay and operate on the right (east) flank of his 17th Brigade. At the same time the 24th Australian Infantry Battalion would create a diversion by operating against the Japanese detachments in the Markham Valley and establishing an ambush on the Huon Gulf at the mouth of the Buang River, halfway between Lae and Salamaua. (Map 6)

From 20 through 23 June the Japanese counterattacked the 17th Brigade’s positions in the vicinity of Mubo and Lababia Ridge, a 3,000-foot eminence that is surrounded by the Bitoi and Buyawim Rivers and has a commanding view of Nassau Bay to the southeast, Bitoi Ridge to the north, and the Komiatum Track which served as the line of communications from Salamaua to the Japanese facing the Australians. The Japanese fought hard but failed to budge the 17th Brigade. Starting on 23 June they retired a short distance to the north. On 30 June Savige’s 15th Brigade was attacking Bobdubi and the 17th Brigade, facing north, was holding Mubo and Lababia Ridge.15

Map 6: Southern Approaches to Salamaua

The MacKechnie Force, designated to land at Nassau Bay on 30 June, consisted of the reinforced 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry. In command was Col. Archibald R. MacKechnie, commander of the 162nd. This regiment had arrived in New Guinea from Australia in February 1943. Organized in March, the MacKechnie Force moved by land marches and seaborne movements in landing craft and trawlers from the Buna–Sanananda area to Morobe, where it set up defensive positions to protect an advanced PT boat base. For Nassau Bay the force was augmented by American and Australian units.16

By late June the 3rd Battalion, 162nd, had relieved the MacKechnie Force of the mission of defending Morobe. Thirty days’ supply and ten units of fire had been assembled. The troops trained for the landing by boarding PT boats, then transferring at sea to LCVPs, and debarking on beaches from the landing craft. On the night of 28 June the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, 162nd, outposted the islands lying offshore between Nassau Bay and Mageri Point about ten miles north-northwest of Morobe, where the invasion was to be mounted, in order to install lights to guide the invasion flotilla. Colonel MacKechnie flew to the Bulolo Valley for a conference with General Savige, and at his request Savige dispatched one of his companies from Lababia Ridge to the mouth of the Bitoi River to divert Japanese attention from Nassau Bay. As

the landing was to be made in darkness, one platoon of this company was sent to the landing beach to set up lights to guide the landing craft. Company A, Papuan Infantry Battalion, of the MacKechnie Force, reconnoitered to Cape Dinga just south of Nassau Bay, and one of its scouts even sneaked into the enemy camp at Cape Dinga and spent the night with the Japanese. On the basis of the Papuan Infantry Battalion’s reports it was estimated 300-400 Japanese were in the vicinity of Nassau Bay, and about 75 more near the south arm of the Bitoi River.17

The Enemy

This estimate was somewhat exaggerated. Present at Cape Dinga were about a hundred men of the 102nd Infantry, 51st Division, and about fifty sailors of a naval guard unit.18 The Japanese were expecting an Allied landing to come in Huon Gulf rather than at Nassau Bay, and had made their dispositions accordingly.

General Adachi, commanding the 18th Army from his headquarters at Madang, had been carrying out the 8th Area Army commander’s orders to strengthen Wewak, Madang, Finschhafen, and especially Lae and Salamaua to protect Vitiaz Strait while preparing to attack Wau, Bena Bena, and Mount Hagen and infiltrate the Ramu and Sepik River Valleys. (See below, Map 12.) The Madang–Lae Highway was still under construction but had been pushed only to the Finisterre Range which parallels the north coast of the Huon Peninsula. The Japanese correctly estimated that the Allies planned to use the air base sites in the mountain valleys to support their advances along the coast. Therefore they planned the moves against Wau and against Bena Bena and Mount Hagen, two outposts that had been used since 1942. The 6th Air Division, based in the Wewak area, was ordered to attack these points daily.

In command at Lae was Maj. Gen. Ryoichi Shoge, infantry group commander of the 41st Division. His command at this time was largely transient, as the 18th Army was sending troops through Lae to strengthen Salamaua. Since the March disaster in the Bismarck Sea, some troops had been landed at Lae from submarines, forty men per boat; others came in barges and destroyers to Cape Gloucester from Rabaul, thence to Finschhafen by barge and overland or by barge to Lae. In April and May the 66th Infantry (less the 3rd Battalion), 51st Division, had been transferred to Salamaua from Lae, and elements of the 115th Infantry, the 14th Artillery Regiment, and the 51st Engineer Regiment, all of the 51st Division, staged through Lae for Salamaua. At Salamaua Lt. Gen. Hidemitsu Nakano, commander of the 51st Division, was directing operations.

The third infantry regiment of Nakano’s division, the 102nd, had made the January attack against Wau and had been almost continuously in action since that time.

By the end of June Nakano had six thousand men under his command. The Japanese defensive positions included the high ground inland from the shore—Mount Tambu, Komiatum, and Bobdubi.

Landing of the MacKechnie Force

As dusk fell at Morobe on 29 June three PT boats of the Seventh Fleet took aboard 210 men of the MacKechnie Force. A fourth PT, without passengers, escorted.19 At the same time twenty-nine LCVPs, two Japanese barges, and one LCM of the 532nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment took the other 770 men of the MacKechnie Force on board at Mageri Point. The landing craft were organized in three waves which departed Mageri at twenty-minute intervals. The night was dark, the sea heavy; rain was falling.

The first two waves rendezvoused with the two PT boats from Morobe which were to guide them to the target but the third missed and proceeded on the forty-mile run to Nassau Bay without a guide.

Thus far things had gone fairly well but the remainder of the night was full of troubles. The rain obscured the guide lights on the offshore islands. The escorting PT lost the convoy. The lead PT overshot Nassau Bay. Some of the landing craft of the first wave followed it, then lost time turning around and finding the convoy again.

The landing began, in rainy darkness, shortly after midnight. The Australian platoon on shore had lost its way and arrived at Nassau Bay in time to install only two instead of three lights. Thus the first two waves of landing craft intermingled and landed together on the same stretch of beach. And a ten- to twelve-foot surf, a rare occurrence at Nassau Bay, was pounding. It rammed the landing craft so far up on the beach that seventeen of them could not back off but promptly broached and filled with water, almost complete wrecks. The LCM, after unloading a bulldozer, was able to retract; it proceeded out to sea and got the troops off the lead PT boat, and then returned to the beach where it swamped.

There was no enemy opposition, nor any casualties. Japanese in an outpost at the beach had fled into the jungle, believing, prisoners reported later, that the bulldozer was a tank. Except for the landing craft, there were no serious losses of equipment, but most of the radios were damaged by salt water.

Seven hundred and seventy men were landed that night.20 The leader of the third wave, which arrived hours after the first two, realized that his craft were the only ones immediately available for resupply and decided not to land until the surf abated. He took the barge and the rest of the LCVPs, with B Company

on board, to shelter in a cove down the coast. When the storm subsided they returned to Nassau Bay but failed to make contact with the troops, who were beating off a Japanese attack. The wave returned to Mageri Point, then went back to Nassau Bay and landed on the afternoon of 2 July.

Once on shore A and C Companies, 162nd Infantry, established defense lines three hundred yards north and south, respectively, of the landing beach. The Australian platoon defended the west (inland) flank. There was no contact with the enemy that night. By daybreak of 30 June the beach was cleared of all ammunition, equipment, and supplies. Beach defenses, employing machine guns salvaged from the wrecked landing craft, were set up. Communication with higher headquarters was a problem. Most of the water-soaked radios would not work, and during the first few days Colonel MacKechnie was out of contact with New Guinea Force, 41st Division headquarters, and Morobe at one time or another. Nothing was heard from the Papuan Infantry Battalion elements on the other side of Cape Dinga for several days. All the SCRs 511 and 536, the small hand radios used for tactical communication within infantry battalions, had been soaked and were never usable during the subsequent operations against Salamaua.

After daylight of 30 June C Company marched south to the Tabali River just west of Cape Dinga. Company A started north from its night positions to clear the area as far as the south arm of the Bitoi River but soon ran into enemy mortar and machine gun fire (its first such experience) and halted. Patrols went out and reported the enemy as present in some strength. Then A Company, reinforced by a platoon of D Company, 216th Australian Infantry Battalion of the 17th Brigade, which had flashed the landing lights, attempted to strike the Japanese right (west) flank but was stopped. When the Australian platoon ran out of ammunition it was relieved by a detachment of engineers from the crews of the wrecked landing craft. Two of the C Company platoons came up from the south to join A Company. At 1500 the force started forward and by 1650 had brushed away scattered Japanese opposition to reach the south arm of the Bitoi River.

When General Adachi received word of the invasion his first thought was to destroy the MacKechnie Force before it had a chance to consolidate. But General Nakano persuaded him that it would be better to “delay the enemy advance in NASSAU from a distance” and to concentrate on the Australian threat at Bobdubi.21 So no more enemy troops were sent against MacKechnie. Meanwhile the Papuan Infantry Battalion troops began pressing against the rear of the Japanese detachment at Cape Dinga. This detachment began moving toward the American beachhead.

About 1630 the C Company platoon defending the left (south) flank reported that Japanese troops were crossing the Tabali River just south of its position, whereupon it was ordered to withdraw to the south flank of the landing beach proper to hold a line between the beach and a swamp which began a short

distance inland. Before the platoon could move, Japanese troops attacked its rear and flank. The platoon fought its way north, losing its commander and four enlisted men killed on the way.

While the platoon was withdrawing, Capt. Paul A. Cawlfield, MacKechnie Force S-3, organized a defense line at the beach using engineers, part of D Company, and men from force headquarters. At dusk the harassed platoon reached this line, and then the enemy struck in a series of attacks that lasted all night. Machine gun, mortar, and rifle fire and grenades hit the American positions, and small parties attempted to infiltrate. But the American units, in action for the first time, beat off the attackers who, except for scattered riflemen that were hunted down and killed, pulled out just before sunrise. The MacKechnie Force estimated that it had killed fifty Japanese. Its own casualties were eighteen killed, twenty-seven wounded. Colonel MacKechnie later asserted that in his opinion several of the American casualties were caused by American troops firing at each other in the excitement of the night action.

By 2 July, with the landing of B Company and other elements of the third wave, the Nassau Bay beachhead was considered secure. On that date the Americans made contact with the 17th Brigade, and the MacKechnie Force made ready to execute its missions in the northward drive against Salamaua.

Thus with the landings at Woodlark, Kiriwina, and Nassau Bay, General MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area inaugurated CARTWHEEL. Compared with the massive strokes of 1944 and 1945, the operations were small, but they gave invaluable amphibious experience to soldiers and sailors and they began a forward movement that was not halted until final victory.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Solomon Sea, Admiral Halsey’s South Pacific forces had executed their first CARTWHEEL missions by invading New Georgia.