Chapter 6: TOENAILS: The Landings in New Georgia

The South Pacific’s tactical and logistical planning for the invasion of New Georgia (TOENAILS, or Operation A) involved all the major echelons of the complex command that was Admiral Halsey’s. Halsey’s position was somewhat unusual. As he phrased it, the Joint Chiefs’ orders of 28 March “had the curious effect of giving me two ‘hats’ in the same echelon.”1 His immediate superior in the chain of command was Admiral Nimitz, who was responsible, subject to decisions by the Joint Chiefs, for supplying him with the means of war. For the strategic direction of the war in the Solomons MacArthur was Halsey’s superior.

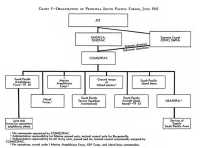

South Pacific Organization

Whereas MacArthur’s headquarters followed U.S. Army organization, Halsey’s followed that of the Navy.2 There were many more subordinates, such as island commanders, reporting directly to Halsey than reporting to MacArthur, and the South Pacific was never organized as simply as the Southwest Pacific. Halsey, by the device of not appointing a single tactical commander of all naval forces, retained personal control of them. There was a single commander of land-based aircraft, but there was never a single ground force commander with complete tactical authority. (Chart 5)

Naval forces, designated the Third Fleet in March 1943, came generally from the U.S. Navy and the Royal New Zealand Navy. Except for New Zealand ships, no warships were ever permanently assigned; as need arose Nimitz dispatched warships to the South Pacific. The South Pacific Amphibious Force (Task Force 32), on the other hand, was a permanent organization to which landing forces were attached for amphibious operations. In command was Rear Adm. Richmond K. Turner who had led the Amphibious Force in the invasion of Guadalcanal the year before.

Land-based air units from all Allied services in the South Pacific were under the operational control of the Commander, Aircraft, South Pacific, Admiral Fitch. Fitch’s command, Task Force 33, was made up of Royal New Zealand and U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps air units. Principal administrative organizations within Task Force 33 were General Twining’s Thirteenth Air Force and the

Organization of Principal South Pacific Forces, June 1943

Map 7: Landings in New Georgia, 21 June–5 July 1943

1st and 2nd Marine Air Wings. The most important tactical organization in Fitch’s force was the inter-service, international outfit known as Air Command, Solomons, that had grown out of the exigencies of the Guadalcanal Campaign.3 Fitch issued general directives which were executed under the tactical direction of the Commander, Aircraft, Solomons, who until 25 July 1943 was Rear Adm. Marc A. Mitscher.

There were two principal ground force commanders in early 1943. The first, General Harmon, an experienced airman who had served as Chief of Air Staff in Washington, was the commanding general of U.S. Army Forces in the South Pacific Area; his command embraced air as well as ground troops. His authority was largely administrative and logistical, but he also advised the area commander on tactical matters and Halsey throughout the period of active operations relied heavily on him. Under Harmon, in early 1943, were four infantry divisions, the Americal, 25th, 37th, and 43rd, as well as the Thirteenth Air Force. The Americal and 25th Divisions had fought in the Guadalcanal Campaign. The 43rd Division had seen no fighting but had received valuable experience when elements of the division took part in the invasion of the Russells. The 37th, which had gone out the year before to garrison the Fijis, was as yet untried. In addition to these divisions, which usually fought under the tactical command of the XIV Corps, there were, in Harmon’s command, the Army garrison troops in the island bases and a growing number, but never enough to satisfy the local commanders, of service units. By mid 1943 Harmon’s command embraced about 275,000 men.

The Marine Corps counterpart to Harmon’s command, as far as ground forces were concerned, was the I Marine Amphibious Corps. This organization, under Maj. Gen. Clayton B. Vogel, USMC, had administrative responsibility over all Marine Corps units, except ships’ detachments and certain air units, in the South Pacific—two Marine divisions, one raider regiment, six defense battalions, one parachute regiment, and service troops. The 1st Marine Division in the Southwest Pacific was nominally administered by the I Marine Amphibious Corps but drew its supplies from Southwest Pacific agencies.

The highest logistic agency, the Service Squadron, South Pacific Force, operated directly under Halsey. It controlled all ships, distributed all supplies locally procured, assigned shipping space, designated ports, and handled all naval procurement. An equally important logistic agency was the Army’s Services of Supply, South Pacific Area. In early 1943 under Maj. Gen. Robert G. Breene it was an expanding organization which was playing an important part in South Pacific affairs.

The organization of the South Pacific, as set forth on paper, seems complicated and unwieldy. Perhaps it could have functioned awkwardly, but the personalities and abilities of the senior commanders were such that they made it work. There is ample testimony in various reports to attest to the high regard in which the aggressive, forceful Halsey and his subordinates held one another, and

events showed that the South Pacific was able to plan and conduct offensive operations involving units from all Allied armed services with skill and success.

Preparations and Plans

Admiral Halsey and his officers had begun planning and preparing for New Georgia in January 1943, before the end of the Guadalcanal Campaign. This process, which involved air and naval bombardments, the assembly of supplies, and reconnaissance of the target area, as well as the preparation and issuance of operation plans and field orders, continued right up to D Day, 30 June.

The Target

In climate, topography, and development, the Solomons are much like New Guinea and the Bismarcks. Their interiors were virtually unexplored. They are hot, jungled, wet, swampy, mountainous, and unhealthful.4

New Georgia is the name for a large group in the central Solomons which includes Vella Lavella, Gizo, Kolombangara, New Georgia (the main island of the group), Rendova, and Vangunu, Simbo, Ganonnga, Wana Wana, Arundel, Bangga, Mbulo, Gatukai, Tetipari (or Montgomery), and a host of islets and reefs. (Map 7) From Vella Lavella to Gatukai, the cluster is 125 nautical miles in length. Several of the islands have symmetrical volcanic cones rising over 3,000 feet above sea level.

In addition to the multitude of small channels, narrows, and passages, navigable only by small craft, there are several large bodies of water in the group. The Slot, the channel sailed so frequently by the Japanese during the Guadalcanal Campaign, lies between New Georgia on one side and Choiseul and Santa Isabel on the other. Marovo Lagoon on New Georgia’s northeast side is one of the largest in the world. Vella Gulf separates Vella Lavella from Kolombangara, which is set off from New Georgia by Kula Gulf. Blanche Channel divides New Georgia from Rendova and Tetipari.

The island of New Georgia proper, the sixth largest in the Solomons, is about forty-five statute miles long on its northwest-southeast axis, and about thirty miles from southwest to northeast. It is mountainous in the interior, low but very rough in the vicinity of Munda Point.

New Georgia proper was difficult to get to by sea except in a few places. Reefs and a chain of barrier islands blocked much of the coast line, which in any event was frequently covered by mangrove swamps with tough aerial prop roots. The best deep-water approach was the Kula Gulf which boasted a few inlets, but Japanese warships and seacoast guns defended much of the shore line of the gulf. There were protected anchorages in the southeast part of the island at Wickham Anchorage, Viru Harbor, and Segi Point. Munda Point, the airfield site, was inaccessible to large vessels. East and west of the point visible islets and reefs, and also invisible ones, barred Roviana and Wana Wana lagoons to large ships. Rounding the lagoons like a crude fence on the seaward side is a tangled string of islands, rocks, and coral reefs—Roviana, Sasavele, Baraulu, and

others, some with names, some without. These all have cliffs facing the sea (south) and slope down to sea level on the lagoon side. The channels between the barrier islands were too shallow for ships. Nor could ships reach Munda Point from Kula Gulf and Hathorn Sound. Diamond Narrows, running from Kula Gulf to the lagoons, was deep but too narrow for large vessels.

Across Blanche Channel from Munda and her guardian islands lies mountainous Rendova, which could be reached from the Solomon Sea. Rendova Harbor, though by no means a port, offered an anchorage to ocean-going ships.

During the first months of 1943 coastwatchers covered the Solomons thoroughly. Buka Passage, between Bougainville and Buka, and Buin on southern Bougainville had been the sites of coastwatching stations for several months, and in October 1942 flying boats and submarines took watchers to Vella Lavella, Choiseul, and Santa Isabel.5

At Segi Point on New Georgia was Donald G. Kennedy, a New Zealander who was District Officer in the Protectorate Government. Like Resident Commissioner William S. Marchant, the Anglican Bishop of Melanesia, and various other officials and members of religious orders, Kennedy remained in the Solomons when the Japanese came.6 At Segi Point Kennedy organized a network of white and Melanesian watchers covering Kolombangara, Rendova, Vangunu, Santa Isabel, and Roviana. A Euronesian medical practitioner was posted on Santa Isabel. On Roviana Sgt. Harry Wickham of the British Solomon Islands Defense Force organized the natives to keep watch over Munda Point.

Kennedy raised a guerrilla band to protect his hideout at Segi Point, for the Japanese occasionally sent out punitive expeditions to hunt him down. The primary mission of the coastwatchers was watching, not fighting, but Kennedy and his band were strong enough to wipe out several patrols that came too close. On one occasion Kennedy and his men, aboard the ten-ton schooner Dadavata, saw a Japanese whaleboat systematically reconnoitering the islets in Marovo Lagoon. They attacked with rifles, rammed the whaleboat, sank it, and killed or drowned its company.7

In addition to gaining information from terrain studies, interrogation of former residents, and coastwatchers’ reports, South Pacific headquarters was able to augment its knowledge of New Georgia by a series of ground patrols. The first such expedition was directed by General Vogel. Four officers and eight enlisted men from each of the four battalions of the 1st Marine Raider Regiment assembled on Guadalcanal on 17 March, then sailed to Florida to board amphibian patrol planes (PBYs) which took them to Segi Point. After Kennedy furnished them with native scouts and bearers, patrols went out to reconnoiter Kolombangara, Viru Harbor, Munda Point, and other areas. Traveling overland and by canoe, they carefully examined

caves, anchorages, and passages. Their mission completed, all parties reassembled at Segi Point on 9 April.

The raiders’ reports indicated that troops in small craft could be taken through Onaiavisi Entrance to a 200 yard-long beach at Zanana, east of the Barike River. From there they could strike westward toward Munda.8 Before D Day, additional patrols from the invading forces went to New Georgia and stayed.

From November 1942 until D Day, Munda and Vila airfields were continuously subjected to air and naval bombardments. Vila, located in a swampy region, was practically never used by the enemy. From January until D Day, Allied cruisers and destroyers shelled Munda four times at night, Vila three times. The net result of the continuous air bombardment and the sporadic naval shelling was that the Japanese could not base planes permanently at Munda. It was used, and only occasionally, as a forward staging field.9

Logistic Preparations

On Halsey’s orders South Pacific agencies had begun assembling supplies and developing bases and anchorages for the invasion of New Georgia as early as January 1943. Admiral Turner, remembering his experiences in the Guadalcanal Campaign, suggested that supplies for the invasion be stockpiled on Guadalcanal, and in February movement of supplies to Guadalcanal (under the appropriate code name DRYGOODS) began. In spite of the fact that the port of Nouméa, New Caledonia, was jammed with ships waiting to be unloaded, in spite of the fact that port facilities at Guadalcanal were so poor, and in spite of a bad storm at Guadalcanal in May that destroyed all the floating quays, washed out bridges, and created general havoc, enough supplies for the invasion were ready on Guadalcanal by June. This was accomplished by Herculean labor at Nouméa, by routing some ships directly to Guadalcanal, and by selective discharge of cargo from other ships. The effects of the storm at Guadalcanal were alleviated by using the ungainly-looking 2½-ton, six-wheel amphibian truck (DUKW) to haul supplies from ships to inland dumps over open beaches. By June 54,274 tons of supplies, exclusive of organization equipment, maintenance supplies, and petroleum products discharged from tankers, had been put ashore. In addition many loaded vehicles, 13,085 tons of assorted gear, and 23,775 drums of fuel and lubricants were moved from Guadalcanal to the Russells in June. Bulk gasoline storage tanks with a capacity of nearly 80,000 barrels were available on Guadalcanal.10 Although

Nouméa and Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides were still the main South Pacific bases, Guadalcanal was ready to play an important role. The South Pacific commanders had insured that haphazard supply methods would not characterize TOENAILS.

Tactical Plans

Final plans and orders for TOENAILS were ready in June.11 Halsey had hoped to invade New Georgia in April, but could not move before the Southwest Pacific was ready to move into the Trobriands and Nassau Bay. The general concept of the operation was worked out by Admiral Halsey, a planning committee, and members of Halsey’s staff. The committee consisted of General Harmon, the Army commander; Admiral Fitch, the land-based air commander; Admiral Turner, the amphibious commander; and General Vogel of the I Marine Amphibious Corps. The principal staff officers concerned were Admiral Wilkinson; Captain Browning, Halsey’s chief of staff; and General Peck, Halsey’s war plans officer. By May agreement was reached on the general plan. It called for the simultaneous seizure of Rendova, Viru Harbor, Wickham Anchorage, and Segi Point. A fighter field would be built at Segi Point. After the initial landings small craft from Guadalcanal and the Russells would stage through Wickham Anchorage and Viru Harbor to build up Rendova’s garrison. Munda’s field would be harassed and neutralized by 155-mm. guns and 105-mm. howitzers emplaced on Rendova and the nearer barrier islands. These moves were preparatory to the full-scale assaults against Munda and Vila, and later against southern Bougainville.

Assigned to the operation were South Pacific aircraft, warships, the South Pacific Amphibious Force, and the heavily reinforced 43rd Division with its commander, Maj. Gen. John H. Hester, in command of the landing forces. The 37th Division, less elements, was in area reserve to be committed only on Halsey’s orders.

Final plans and tactical organization were complicated, as TOENAILS called for four separate simultaneous invasions (Rendova, Wickham Anchorage, Segi Point, and Viru Harbor) with the Rendova landing to be followed by two more on the same island.

Admiral Halsey’s basic plan, issued on 3 June, organized the task forces, prescribed their general missions, and directed Admiral Turner to coordinate the planning of the participating forces. Four task forces were assigned to the operation: Task Force 33, the Aircraft, South Pacific, under Admiral Fitch; Task Force 72, a group of Seventh Fleet submarines

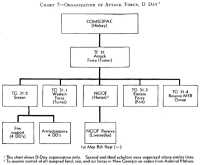

Organization of South Pacific Forces for TOENAILS

commanded by Capt. James F. Fife and now under Halsey’s operational control; Task Force 36, the naval covering force commanded, in effect, by Halsey himself; and Task Force 31, the attack force. (Chart 6)

Task Force 33, to which Halsey temporarily assigned planes from Carrier Division 22 (three escort carriers), was to provide defensive reconnaissance for New Georgia operations and the Southwest Pacific’s seizure of Woodlark and Kiriwina, and to cover the area northeast of the Solomons (Southwest Pacific planes were responsible for the Bismarcks). It was to destroy enemy units which threatened South and Southwest Pacific forces, especially Japanese planes operating from New Georgia and southern Bougainville. Fitch’s planes were also to provide fighter cover, direct air support, and liaison and spotting planes for the attack force. Starting D minus 5, Task Force 33 would attempt to isolate the battlefield by attacking the Japanese air bases at Munda, Ballale, Kahili, Kieta, and Vila, and by striking at surface vessels in the Bougainville and Munda areas. During daylight, fighters would cover ships and ground troops, and antisubmarine patrols would be maintained for convoys. Black Cats (PBYs) would cover all night movements. Striking forces at all times were to be prepared

to hit enemy surface ships. Beginning on D Day, eighteen dive bombers would remain on stand-by alert in the Russells. Medium bombers were to be prepared to support the ground troops. Finally, arrangements were made for air dropping supplies and equipment to the ground troops in New Georgia.

One innovation in the command of supporting planes had apparently arisen from Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift’s recommendations based on his experiences in invading Guadalcanal.12 Halsey directed that on take-off from Guadalcanal and Russells fields planes assigned to missions in the immediate area of operations would come under control of the local air commander (the Commander, New Georgia Air Force). Direction of fighters over Task Force 31 was to be conducted by a group aboard a destroyer until direction could be conducted ashore on Rendova. Similarly, bomber direction for direct air support would be handled aboard Turner’s flagship McCawley until bomber director groups could establish themselves ashore. In early June, Fitch issued orders concentrating most of his strength in the Guadalcanal area under Admiral Mitscher.13 Totals for aircraft involved were fairly impressive. On 30 June Fitch had on hand for the operation 533 planes, of which 213 fighters, 170 light bombers, and 72 heavy bombers were ready to fly.14

Task Force 36 included part of the 37th Division on Guadalcanal in area reserve, besides all Halsey’s naval strength except that assigned to the attack force. Naval units, including aircraft carriers (two CV’s and three CVEs), battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, would operate out of Nouméa, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides into the Coral and Solomon Seas to intercept and destroy any Japanese forces which ventured out. The reserve 37th Division forces were to be committed, on five days’ notice, on orders from Halsey.

Captain Fife’s submarines would at first conduct offensive reconnaissance from about latitude one degree north southward to the prevailing equatorial weather front. Once the Japanese were aware of the invasions, Fife’s boats were either to concentrate on locating enemy vessels or to withdraw south to cover Bougainville Strait and the waters between New Ireland and Buka. This reconnaissance would be in addition to patrols by Central Pacific submarines, which would keep watch over any Japanese surface forces approaching the South from the Central Pacific.

Admiral Turner’s attack force (Task Force 31) consisted of ships and landing craft from the South Pacific or III Amphibious Force (Task Force 32), plus the ground troops. These troops, designated the New Georgia Occupation Force, initially included the following units:

43rd Division

9th Marine Defense Battalion

1st Marine Raider Regiment (less two battalions)

136th Field Artillery Battalion (155mm. howitzers), 37th Division

Elements of the 70th Coast Artillery Battalion (Antiaircraft)

One and one-half naval construction battalions

Elements of the 1st Commando, Fiji Guerrillas15

Radar units

Naval base detachments

A boat pool

Creating the New Georgia Occupation Force, and attaching all ground troops to it (instead of attaching the supporting units to the 43rd Division), made another headquarters necessary, and threw a heavy burden on 43rd Division headquarters. General Hester commanded both force and division, and the 43rd Division staff was, in effect, split into two staffs. The 43rd Division’s staff section chiefs (the Assistant Chiefs of Staff, G-1, G-2, G-3, and G-4), as well as officers from Harmon’s headquarters, served on the Occupation Force staff sections, and their assistants directed the division’s staff sections. Brig. Gen. Harold R. Barker, 43rd Division artillery commander, commanded all Occupation Force artillery—field, seacoast, and antiaircraft.

From the start General Harmon was dubious about the effectiveness of this arrangement. He was “somewhat concerned that Hester did not have enough command and staff to properly conduct his operation in its augmented concept.”16 On 10 June, with Halsey’s concurrence, he therefore told Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, commanding the XIV Corps and the Guadalcanal Island Base, to keep himself informed regarding Hester’s plans in order to be prepared to take over if need be.17

The general plan of maneuver called for assault troops from Guadalcanal and the Russells to move to Rendova, Segi Point, Wickham Anchorage, and Viru Harbor on APDs, transports, cargo ships, minesweepers, and minelayers. Segi, Wickham, and Viru would be taken by small forces to secure the line of communications to Rendova while the main body of ground forces captured Rendova. Artillery on Rendova and the barrier islands was to bombard Munda, an activity in which ships’ gunfire would also be employed. On several days following D Day, slow vessels such as LSTs and LCTs would bring in more troops and supplies. They would travel at night and in daylight hours hide away, protected from Japanese planes by shore-based antiaircraft, in Wickham Anchorage and Viru Harbor. About D plus 4, when enough men and supplies would be on hand, landing craft were to ferry assault troops from Rendova across Roviana Lagoon to New Georgia to begin the march

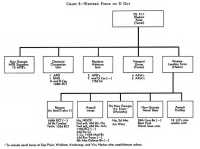

Organization of Attack Force, D Day

against Munda. Coupled with this advance would be the amphibious seizure of Enogai Inlet in the Kula Gulf to cut the Japanese reinforcement, supply, and evacuation trail between Munda and Enogai, and thus prevent the Japanese on Kolombangara from strengthening their compatriots on New Georgia. Once Munda and Enogai were secured, it was planned, Vila on Kolombangara would be seized and further advances up the Solomons chain would follow.

Turner organized his force into five groups. (Chart 7) The Western Force (Task Group 31.1), which Turner commanded in person, would seize Rendova and make subsequent assaults against Munda, Enogai, and Kolombangara. The Eastern Force, under Rear Adm. George H. Fort, was to take Segi, Viru, and Wickham. Task Group 31.2, consisting of eight destroyers, would cover the transports. No ships’ gunfire support was planned in advance, but all ships, including transports, were ordered to be ready to deliver supporting and counterbattery fire if necessary.

The New Georgia Occupation Force, under General Hester, included the Western Landing Force (under Hester),

which during the amphibious phase would function as part of Turner’s Western Force; the Eastern Landing Force (under Col. Daniel H. Hundley), which during the amphibious phase would be part of Fort’s Eastern Force; naval base forces for all points to be captured; the reserve under Col. Harry B. Liversedge, USMC; and two more whose designations are not self-explanatory—the New Georgia Air Force and the Assault Flotillas. (Charts 8 and 9)

The New Georgia Air Force, led by Brig. Gen. Francis P. Mulcahy, USMC, consisted initially of Headquarters, 2nd Marine Air Wing. In contrast with the system in the Southwest Pacific, this air headquarters was under the landing force commander. Mulcahy was to take over control of New Georgia air operations during the amphibious phase once that control was relinquished by Turner; he would take command of the planes from Guadalcanal and the Russells that would be supporting the attack, once they were airborne. He was eventually to command the air squadrons to be based at Munda and Segi Point. The Assault Flotillas consisted of landing craft to be used to ferry the assault troops from Rendova to New Georgia proper when the attack against Munda was ready to begin.

Two ground force units which Turner retained temporarily under his direct control were small forces designated to make covering landings. The Onaiavisi Occupation Unit, composed of A and B Companies, 169th Infantry, was to land from two APDs and one minesweeper on Sasavele and Baraulu Islands on either side of Onaiavisi Entrance to hold it until the day of the assault against the mainland through the entrance. The landing of the occupation unit was scheduled for 0330, 30 June. The Rendova Advance Unit, C and G Companies (each less one rifle platoon), was to land from two APDs on Rendova at 0540 to cover the landing of the main body of the Western Landing Force. The latter, about 6,300 strong, was to start landing on Rendova at 0640, 30 June.

Command over all air, sea, and ground forces in New Georgia would pass from Turner to Hester on orders from Halsey.

The presence of the DRYGOODS stockpiles on Guadalcanal greatly simplified logistical problems. Three Army units of fire and thirty days’ supplies were to be put ashore at Rendova, and five units of fire and thirty days’ supplies at Viru, Segi, and Wickham. Supply levels were to be built to a sixty-day level out of the DRYGOODS stocks. General Griswold was told to make the necessary quantities available to Turner. Turner was responsible for the actual movement of supplies to New Georgia.

Directions for unloading during the assault phase were simple and clear. Turner instructed all vessels to be ready for quick unloading. All ships were to square away before reaching the transport areas offshore, and if possible to work all hatches from both sides. Unloading parties included 150 men for each cargo ship and transport, 150 men per LST, 50 men per LCT, and 25 men per LCI. The shore party totaled 300 men. Once ashore, cargo was to be moved off the beaches and into inland dumps as fast as possible.

Secondary Landings

With tactical plans for TOENAILS largely ready by mid-June, the invasion

Western Force on D Day

Eastern Force on D Day

forces spent the rest of the month making final preparations—checking weapons and supplies, conducting rehearsals in the New Hebrides, and studying orders, maps, and photographs. South Pacific aircraft pounded Vila, Munda, and the Shortlands–Bougainville bases while Southwest Pacific planes continued their long-range strikes against Rabaul.

Segi Point

In the midst of these preparations, Admiral Turner received disquieting news about Segi Point, which was scheduled to furnish the Allies with an airfield. Coastwatcher Donald Kennedy reported on 20 June that the Japanese were moving against his hideout and that he was heading for the hills. He requested help.18

Kennedy’s report was correct. In early June a small Japanese force had gone to the southeast part of Vangunu to deal summarily with disaffected natives, and on 17 June half the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry, under a Major Nagahara or Hara had moved from Viru Harbor southeast toward Segi Point.

As loss of Segi Point prior to D Day would deprive the Allies of a potential air base, Turner, a man of fiery energy and quick decision, abruptly changed his plans. He had originally intended to land the heavily reinforced 1st Battalion, 103rd Infantry, at Segi on 30 June to build the fighter field and establish a small naval base. But on receipt of Kennedy’s call for aid, he hurriedly dispatched the handiest force available, the 4th Marine Raider Battalion (less N and Q Companies), from Guadalcanal in the fast destroyer-transports Dent and Waters to seize Segi and hold it. Ships and marines wasted no time. By 2030 of the same day—20 June—the ships were loaded and under way. Before dawn next morning they had safely worked their way through Panga Bay, though both vessels scraped bottom in the reef- and rock-filled waters. Kennedy, still safe, had lit bonfires on the beach and when the marines started ashore at 0550 he was there to meet them. There were no Japanese. The major and his men were still in the vicinity of Lambeti Village.

Next morning the APDs Schley and Crosby brought A and D Companies of the 103rd Infantry and an airfield survey section to Segi Point. Though alerted several times against enemy attack, the Segi garrison was undisturbed until 30 June, when a series of Japanese air attacks made things lively. Construction of the airfield began on 30 June. Using bulldozers and power shovels, and working under floodlights at night, the Seabees of the 20th Naval Construction Battalion had the strip ready for limited

Airfield at Segi Point, New Georgia

operations as a fighter staging field by 11 July.19

Wickham Anchorage

The force selected for the seizure of Wickham Anchorage by Vangunu Island was ready to sail from the Russells on 29 June. Commanded by Lt. Col. Lester E. Brown, the force included Colonel Brown’s 2nd Battalion, 103rd Infantry, reinforced, and N and P Companies, plus a headquarters detachment, of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion. Under Admiral Fort aboard the Trever, the convoy consisted of the destroyer-transports Schley and McKean, carrying marines, and seven LCIs which bore soldiers. The ships cast off shortly after 1800 and set course for Oleana Bay, about two and one-half miles west by south from Vura village.

Allied scouting parties had reported that the main Japanese concentration at Wickham Anchorage—one platoon of the 229th Infantry and a company of the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force—was near Vura, and had also reported that on the east shore of Oleana Bay a 500-yard-long strip of solid sand offered a good landing beach. It had therefore been decided to land the troops at Oleana Bay and then march overland and outflank the enemy positions from the west. There were two trails from Oleana Bay to Wickham Anchorage. One, which followed the shore line, was believed used by the Japanese, but a shorter one had been cut farther inland in April by Kennedy’s

men in order to get scouts into the Vura area. This trail was thought to be unknown to the Japanese, and troops following native guides could be expected to cover it in five or six hours.

Visibility was practically nonexistent for the Wickham-bound convoy on the night of 29-30 June. Rain, lashed by a stiff wind, fell throughout the night, and continued as the vessels threaded their cautious way through the shoals and reefs into Oleana Bay. At 0335, 30 June, the ships hove to. Shortly afterward the first wave of marines began to debark from the destroyer-transports into LCVPs, a task complicated by darkness, rain, high wind, and heavy seas. Two LCVPs were almost loaded when the APD commanders discovered they were lying off the west rather than the east shore of the bay. The marines reboarded the destroyer-transports which then moved a thousand yards eastward.

Again the marines loaded into LCVPs and started for the beach, which was obscured by rain and mist. Beach flares which had been set by members of the scouting party were invisible. Only the noise of the breakers indicated the direction of the shore. But things got worse. As the first wave of LCVPs blindly made their way shoreward, the LCIs broke into the formation and scattered it. Unable to re-form, or even to see anything, the LCVP coxswains proceeded on their own. The result was exactly what might be expected from a night landing in bad weather. The assault wave of marines landed in impressive disorganization. Six LCVPs smashed up in the heavy surf that boiled over coral reefs. Fortunately, the Japanese were not present to oppose the landing. There were no casualties.

The LCIs, landing in daylight, found the proper beach, and by 0720 the Army troops were ashore. More marines had begun landing at 0630 at the correct beach. With all landing operations concluded by 1000, the ships departed.

Three officers of the reconnaissance party had met the landing force and informed Colonel Brown that the Japanese main strength was at Kaeruka rather than Vura. Once the scattered troops had been collected, the overland advance began with a small column moving toward Vura along the coastal trail while the main column marched against Kaeruka over Kennedy’s trail. The marines and soldiers first met the enemy in early afternoon. Then ensued four days of fighting in the sodden jungles, with the Americans receiving support from dive bombers and warships, from their own heavy weapons, and from the 105-mm. howitzers of the 152nd Field Artillery Battalion on the beach at Oleana Bay. By the end of 3 July the Americans, having blasted the Japanese out of their entrenchments, were in complete possession of Wickham Anchorage. Many of the Japanese garrison had been killed; some escaped by barge, canoe, or on foot. In the seizure of this future staging point for landing craft, the marines lost twelve killed, twenty-one wounded. Army casualties are not listed.

Viru Harbor

When the Viru Occupation Force, the reinforced B Company, 103rd Infantry, on board three destroyer-transports, sailed into Viru Harbor before daylight on 30 June, lookouts vainly scanned the shore line for a white parachute flare. This was to have signaled that the

Men of 152nd Field Artillery Battalion firing a 105-mm. howitzer in support of Colonel Brown’s 2nd Battalion, 103rd infantry

marine raider companies that landed at Segi Point had moved against Viru from inland and seized positions flanking the harbor, for it had been agreed that attempting to land the infantry in frontal assault against the high cliffs surrounding the harbor would be too risky. But Lt. Col. Michael S. Currin, commanding the 4th Marine Raider Battalion, had warned that his overland march was going slowly and that he might not arrive and take the harbor by 30 June. Thus the destroyer-transports waited just outside the harbor, beyond range of a Japanese shore battery (Major Hara had left part of his battalion at Viru) and at noon went to Segi Point where with Turner’s approval the troops went ashore. The attack force commander agreed that in view of the delay B Company should follow the marine raiders in their overland march.

Currin’s men had begun the first leg of their twelve-mile advance from Segi Point to Viru Harbor in rubber boats on 27 June. They landed near Lambeti Plantation that night, and the next morning set out on their overland march. Skirmishes with the Japanese, coupled with the difficulty of walking through the jungle, slowed them down. They forded streams, knee-deep in mud and shoulder high in water. The leading elements of the column churned the trail into slippery ooze, so that the rear elements floundered and stumbled along. Thus

it was evening of 30 June before the marines reached Viru Harbor, which they took handily the next day by a double envelopment supported by dive bombers that knocked out the Japanese shore battery.20 On 4 July B Company, 103rd, which had come up from Segi Point, took over the defenses of Viru Harbor from the marines.

Thus were the operations of the Eastern Force conducted, separately from each other and separately from those of the Western Force, but under Admiral Turner’s general supervision in his capacity of attack force commander. They had provided one airfield and two staging bases. While important, they were undertaken only to support the seizure of Rendova by a substantial force, which was then to assault Munda and Vila.

Rendova

Admiral Turner’s ships that were assigned to Rendova arrived off Guadalcanal in the morning of 29 June.21 They had come up from Efate bearing the assault troops of the Western Landing Force’s first echelon. They weighed anchor late that afternoon and made an uneventful journey through the mist and rain to Blanche Channel between Rendova and New Georgia.

No enemy warships were there to oppose them. Their absence had been ensured by a group of cruisers, destroyers, and minelayers from Halsey’s Task Force 36 under Rear Adm. Aaron Stanton Merrill. Merrill’s ships, on the night of 29-30 June, had bombarded Munda and Vila, then ventured northwest to the Shortlands to shell enemy bases and lay mines. This action inflicted damage to the Japanese while placing a surface force in position to cover Turner’s landings. The bad weather canceled the air strikes against the Bougainville–Shortland bases, but Allied planes—dive and torpedo bombers—were able to hit Munda and Vila on 30 June.

The night of 29-30 June was short for the six-thousand-odd troops aboard Turner’s ships. Reveille sounded at 0200, more than four hours before the ships hove to off Renard Entrance, the channel leading to Rendova Harbor.

First landings were made by the Onaiavisi Occupation Unit—A and B Companies, 169th Infantry. These had come from the Russells in the destroyer-transport Ralph Talbot and the minesweeper Zane to land on Sasavele and Baraulu Islands before daylight in order to hold Onaiavisi Entrance against the day that the New Georgia Occupation Force made its water-borne movement against the mainland. Later in the morning B Company’s 2nd Platoon outposted Roviana Island and the next day wiped out a Japanese lookout station. These landings were not opposed. The Japanese had maintained observation posts on the barrier islands but had not fortified them. The only mishap in this phase of TOENAILS occurred early in the morning of 30 June, when the Zane ran on a reef while maneuvering in the badly charted waters in the rain. She was pulled free by the tug Rail in the afternoon.

The landing of the 172nd Infantry on

Ships moving toward Rendova, late afternoon, 29 June 1943

Rendova was somewhat disorderly. C and G Companies, guided by Maj. Martin Clemens and Lt. F. A. Rhoades, RAN, of the coastwatchers, and by native pilots, were to have landed from the destroyer-transports Dent and Waters on East and West Beaches of Rendova Harbor at 0540 to cover the main body of the 172nd Infantry when it came ashore.22 But again the weather played the Allies foul. The mist and rain obscured the Renard Entrance markers and the white signal light on Bau Island that the reconnaissance party, present on Rendova since 16 June, had set up. As a result the APDs first landed C and G Companies several miles away, then had to re-embark them and go to the proper place.

Meanwhile, the six transports took their stations north of Renard Entrance as the destroyers took screening positions to the east and west. By now the clouds had begun to clear away, and visibility improved. The troops gathered on the transport decks, and the first wave climbed into the landing craft at the rails, carrying their barracks bags with them. The order “All boats away, all troops away” was given aboard Turner’s flagship, the transport McCawley, as the sun rose at 0642. Four minutes later

Aboard the transport McCawley, Admiral Turner’s flagship, 29 June 1943. From left, Brig. Gen. Leonard F, Wing, Rear Adm. Theodore S. Wilkinson, Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner, and Maj. Gen. John H. Hester

Turner warned the first boats as they headed for shore, some three thousand yards to the south: “You are the first to land, you are the first to land—expect opposition.”23

As the landing craft moved shoreward the waves became disorganized. When the craft reached Renard Entrance between Bau and Kokorana Islands, there was confusion and milling about until they began going through the entrance two abreast toward the narrow East and West Beaches that fronted Lever Brothers’ 584-acre plantation.

As the first landing craft touched down about 0700, the troops sprang out and ran across the beaches into the cover of the jungle. C and G Companies reached Rendova Harbor about ten minutes after the troops from the transports, and they joined with the main body and moved inland toward the Japanese.24

The Japanese Rendova detachment—about 120 troops from the 229th Infantry and the Kure 6th Special Naval Landing Force—had been alerted early during the morning of 30 June. The alert proved to be a false alarm and they went back to sleep. The next alert—their first realization that they were being attacked—came when the American assault craft hit the beach. As it was too late for the Japanese to man their beach defense positions, they posted themselves in the coconut plantation about one hundred yards behind East Beach. Radiomen tried to warn Munda but could not get the message through. A lookout at Banieta Point fired four blue flares and signaled headquarters by blinker.

The Japanese could not hope to do more than harass the Americans. The special naval landing force commander, hit in the face by a burst from a BAR, was an early casualty. When about a dozen men were dead, the disorganized Japanese fell back into the jungle. They are reported to have lost some fifty or sixty men, while killing four Americans and wounding five, including Col. David M. N. Ross, the 172nd’s commander. By the end of the day the Americans had pushed inland one thousand yards. The 105-mm. howitzers of the 103rd Field Artillery Battalion were in position to cover Renard Entrance, the north coast of Rendova, and the barrier islands.

All troops except working parties on board ship were ashore within thirty minutes after the landing of the first wave. This number included General Harmon who went along to observe operations. In the absence of strong enemy resistance on Rendova, the chief problem that confronted the invaders was unloading supplies, getting them ashore, and moving them inland. Less than half an hour after they had been lowered into the water, the first landing craft returned to the ships for cargo. No landing waves were formed; each craft moved cargo ashore as soon as it was loaded by its mother ship.

The first real delay in unloading was caused by shallow water. Many tank lighters (LCMs) grounded on reefs in the harbor and lost time refloating and finding passages through deeper water. Many lighters, grounding about fifty feet offshore, had to lower their ramps in water while the troops waded ashore with cargo in their hands or on their shoulders. In consequence, disorderly stacks of gear began piling up near the shore line. The beachmaster attempted, with only partial success, to prevent this.

During most of the morning the Japanese did little. The Rendova garrison had not amounted to much; after the war the Japanese explained that the Munda and Rabaul commanders had not expected the Americans to land on the offshore islands. “Therefore,” a postwar report states, “the landing on RENDOVA Island completely baffled our forces.”25 When it became clear that the Americans were indeed landing on Rendova, 120-mm. and 140-mm. naval coast defense batteries at Munda and Baanga Island opened up on the ships, and they immediately replied with 5-inch fire. The destroyer Gwin was soon hit. She was the only casualty in the exchange of fire between ships and shore batteries that continued all day. But Turner and General Hester were operating very close

Men of 43rd Signal Company wading ashore from LCMs with signal equipment, 30 June 1943

to the Japanese air bases in southern Bougainville and the Shortlands, and these presented the greatest danger. Fortunately for the Americans, the Japanese were not prepared to counterattack at once.

The commanders at New Georgia were not the only Japanese surprised by the invasion. Those at Rabaul were taken equally unaware. They had, of course, known that some form of Allied activity was impending in late June. The move to help Kennedy, the increasing tempo of Allied air and naval action, and intercepted Allied radio traffic told them as much. So Admiral Kusaka gathered air attack forces together and sent them to the airfields around Buin. But after 26 June, when Allied movements seemed to slow down (Turner’s task force was then rehearsing in the New Hebrides), the Japanese command concluded that the Allies had been simply reinforcing Guadalcanal on a grand scale. Kusaka pulled his air units back to Rabaul. Thus it was that although a submarine had sighted Turner’s ships south of New Georgia about midnight, Kusaka, with sixty-six bombers, eighty-three fighters, and twenty reconnaissance seaplanes at his disposal, could do nothing about the invasion for several hours.

Turner, whose plans called for unloading to be completed by 1130, was first interrupted by a false air raid alarm at 0856. The ships stopped unloading and steamed around in Blanche Channel while the thirty-two fighter planes covering

the landing got ready to intercept. The reported enemy planes failed to appear, and unloading was resumed.

The first real enemy air attack, a sweep by twenty-seven fighters, came just after 1100. The Allied fighter cover shot most of them down before they could do any damage, but Turner’s schedule was further delayed by the necessity for going to general quarters and getting under way.

By about 1500 all but about fifty tons of gear had been unloaded. Turner ordered the transports and screening destroyers back to Guadalcanal and they speedily took their departure. Shortly afterward twenty-five Japanese bombers, escorted by twenty-four fighters, came down from Rabaul. The majority of the bombers were shot down, but one managed to put a torpedo into the flagship McCawley. At 1715 eight more bombers struck at the retiring task force but failed to score. That evening overeager American PT boats, mistaking the crippled McCawley for an enemy, put two more torpedoes into her sides and she sank in Blanche Channel, fortunately without loss of life.

Meanwhile the landing and handling of supplies on Rendova had been less than satisfactory. The invading forces had hoped to use Rendova Plantation to store supplies, although the preinvasion patrols had not been able to investigate it thoroughly because the Japanese were there. As the rain continued, the streams flooded, and the red clay of the plantation turned into mud. The mile-long prewar road that linked East and West Beaches served well early in the day, but soon heavy truck traffic ground it into a muddy mess. Seabee drivers of the 24th Naval Construction Battalion had to hook their truck cables to trees and winch their 2½-ton, 6x6 trucks along in order to haul supplies from the heaped beaches to the cover and safety of high ground farther inland. They cut hundreds of coconut logs into twelve-foot lengths and tried to corduroy the roadbed, but the mud seemed to be bottomless. One bulldozer sank almost out of sight. To add to the supply difficulties, many containers were inadequately marked and medical supplies became mixed among rations, fuel, and ammunition. The Rendova naval base force could not find all its radios, and little was known regarding the progress of operations at Wickham and Viru. The clutter and confusion caused by bogged trucks on the muddy roads and trails finally became so bad that the next day General Hester requested Turner to stop further shipments of trucks until the beachhead could be better organized.

Despite the confusion ashore and the loss of the McCawley, operations on 30 June were largely successful. Six thousand men of the 43rd Division, the 24th Naval Construction Battalion and other naval units, and the 9th Marine Defense Battalion had come ashore with weapons, rations, fuel, ammunition, construction equipment, and personal baggage. The Japanese had lost Rendova and several planes, and although they enthusiastically reported inflicting heavy damage to Turner’s ships, they admitted that, “due to tenacious interference by enemy fighter planes, a decisive blow could not be struck against the enemy landing convoy.” “The speedy disembarkation of

the enemy,” they felt, “was absolutely miraculous.”26

With the capture of the beachhead, General Hester dissolved the 172nd Regimental Combat Team and returned the field artillery, engineers, and medical and communications men to divisional control. The build-up of troops and supplies for the attack against Munda and Vila was ready to begin.

The second echelon of the Western Force came in on LSTs the next day. This echelon included the 155-mm. howitzers of the 192nd Field Artillery Battalion and the 155-mm. guns of A Battery, 9th Marine Defense Battalion. Succeeding reinforcements continued to arrive at Rendova, Segi Point, Viru, and Wickham through 5 July until virtually the entire New Georgia Occupation Force as then constituted was present in New Georgia, with the main body at Rendova.

The Japanese were unable to do anything to prevent these movements, and did little damage to the beachhead. Only Japanese aircraft made anything like a sustained effort. Storms and poor visibility continued to prevent Allied planes from striking at the Shortlands–Bougainville fields, although they were able to hit the Munda and Vila airfields as well as Bairoko. The Japanese reinforced their air strength at Rabaul and sent planes forward to southern Bougainville and the Shortlands. On 2 July Admiral Kusaka had under his command 11 fighters and 13 dive bombers from the carrier Ryuho, 11 land-based twin-engine bombers, 20 fighters, 2 reconnaissance planes, and a number of Army bombers that were temporarily assigned. The same day foul weather began closing in the rearward Allied bases. About noon the Commander, Aircraft, Solomons, from his post on Guadalcanal, ordered all Allied planes back. This left New Georgia without air cover. To make matters worse, the 9th Marine Defense Battalion’s SCR 602 (a search radar designed for immediate use on beachheads) broke down that morning, and the SCR 270 (a long-range radar designed for relatively permanent emplacement) was not yet set up.

Kusaka sent all his planes to New Georgia. They reached the Rendova area in the afternoon, circled behind the clouded 3,448-foot twin peaks of Rendova Peak, then pounced to the attack. Many soldiers saw the planes but thought they were American until fragmentation clusters dropped by the bombers began exploding among them. The Rendova beachhead, with its dense concentrations of men and matériel, was an excellent target. At least thirty men were killed and over two hundred were wounded. Many bombs struck the fuel dumps, the resulting fires caused fuel drums to explode, and these started more fires. Three 155-mm. guns of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion were damaged. Much of the equipment of the 125-bed clearing station set up by the 118th Medical Battalion was destroyed; for a time only emergency medical treatment could be rendered. The wounded had to wait at least twenty-four hours before they could receive full treatment at Guadalcanal.

That night nine Japanese destroyers and one light cruiser shelled Rendova but hit nothing except jungle. The Japanese,

it was clear, did not intend to land troops on Rendova, but they did not intend to allow the Americans to remain there unmolested. The air attacks, while serious, did not disrupt preparations for the next phase of TOENAILS.

The Move to Zanana

After the occupation of Rendova, the next tasks facing the invaders were the movement to the New Georgia mainland and the assault against Munda airfield. On 2 July Admiral Halsey, doubtless encouraged by the lack of effective Japanese opposition, directed Turner to proceed with plans for the move against Munda. To carry out these plans, Turner on 28 June had reorganized the Western Force into five units: the transport unit consisting of destroyer-transports and high-speed minesweepers; a destroyer screen; a fire support group, eventually consisting of three light cruisers and four destroyers; two tugs; and the Munda–Bairoko Occupation Force under General Hester.

The Munda–Bairoko Occupation Force was further divided into five components. The Northern Landing Group, under Colonel Liversedge, was to operate against Bairoko. The Southern Landing Group (the 43rd Division less the 1st Battalion of the 103rd Infantry, the 136th Field Artillery Battalion, the 9th Marine Defense Battalion less elements, and the South Pacific Scouts) under Brig. Gen. Leonard F. Wing, assistant commander of the 43rd Division, was to attack Munda. The New Georgia Air Force, the Assault Flotillas (twelve LCIs, four LCTs, and native canoes), and a naval base group comprised the remaining three components. The Southern Landing Group was to land at Zanana Beach about five air-line miles east of Munda and attack westward to capture Munda while the Northern Group landed at Rice Anchorage in the Kula Gulf and advanced southward to capture or destroy the enemy in the Bairoko–Enogai area, block all trails from there to Munda, and cut off the Japanese route of reinforcement, supply, and escape.27

The troops on Rendova had been making ready since 30 June, but some of their efforts were marked by less than complete success. Hester had ordered aggressive reconnaissance of the entire area east and north of Munda. Starting on the night of 30 June–1 July, patrols from the 172nd Infantry were to pass through Onaiavisi Entrance and Roviana Lagoon, land at Zanana, and begin reconnoitering, while Marine patrols pushed south from Rice Anchorage. The 43rd Division patrols were to operate from a base camp west of Zanana established on the afternoon of 30 June by Capt. E. C. D. Sherrer, assistant intelligence officer of the New Georgia Occupation Force.

At 2330, 30 June, despite a false rumor that Onaiavisi Entrance was impassable for small boats, patrols left Rendova on the eight-mile run to the mainland. The next morning regimental headquarters discovered that the patrols, unable to find the entrance in the dark, had landed on one of the barrier islands. The next evening the 1st Battalion, accompanied by Colonel Ross, shoved off for the mainland but could not find its way. Thus it was concluded that the move should

Truck towing a 155-mm. howitzer over muddy trail, Rendova, 7 July 1943

be made in daylight. Accordingly A Company, 169th Infantry, and the 1st Battalion, 172nd Infantry, moved out for Zanana on the afternoon of 2 July. Native guides in canoes marked the channel. Everything went well except that about 150 men returned to Rendova at 2330. Questioned about their startling reversal of course, they are reported to have stated that the coxswain of the leading craft had received a note dropped by a B-24 which ordered them to turn back.28 By the next morning, however, the entire 1st Battalion was on the mainland.

The build-up of supplies on Rendova continued to be difficult; the rain and mud partially thwarted the efforts of the 118th Engineer and the 24th Naval Construction Battalions to drain the flat areas. East Beach was finally abandoned. The Occupation Force supply officers, after examining the solid coral subsurfaces under the sandy loam of the barrier islands, began using the islands as staging points for supplies eventually intended for the mainland.

On the other hand, the artillery picture was bright. General Barker, the artillery commander, had never planned to make extensive use of Rendova for artillery positions, as the range from Rendova to Munda was too great for all weapons except 155-mm. guns. Such barrier islands as Bau, Kokorana, Sasavele, and Baraulu could well support artillery, and these islands, open on their

north shores, possessed natural fields of fire. The field artillery could cover the entire area from Zanana to Munda, and initially would be firing at right angles to the axis of infantry advance and parallel to the infantry front. This would enable the artillery to deliver extremely accurate supporting fire, since the dispersion in artillery fire is greater in range than in deflection. On the other hand, it would increase the difficulty of coordination between artillery and infantry, for each artillery unit would require exact information regarding not only the front line of the unit it was supporting, but also the front line of the unit’s neighbors. Three battalions of artillery were in place in time to cover the move of the 1st Battalion, 172nd Infantry, to Zanana, and by 6 July two battalions of 105-mm. howitzers (the 103rd and 169th), two battalions of 155-mm. howitzers (the 136th and 192nd), and two batteries of 155-mm. guns (9th Marine Defense Battalion) were in place, registered, and ready to fire in support of the infantry.

Antiaircraft managed to make a tremendous improvement over its performance of 2 July, and celebrated Independence Day in signal fashion when a close formation of sixteen unescorted enemy bombers flew over Rendova. This time radars were working, the warning had been given, and fire control men and gunners of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion’s 90-mm. and 40-mm. batteries were ready. The Japanese flew into a concentration of fire from these weapons, and twelve immediately plunged earthward in return for the expenditure of eighty-eight rounds. The fighter cover from the Russells knocked down the remaining four.

Meanwhile, at Zanana, the 1st Battalion, 172nd Infantry, established a perimeter of 400 yards’ radius, wired in and protected by machine guns, 37-mm. antitank guns, and antiaircraft guns. Here General Wing set up the 43rd Division command post, and to this perimeter came the remaining troops of the 172nd and 169th Infantry Regiments in echelons until 6 July when both regiments had been completely assembled. Ground reconnaissance by 43rd Division soldiers, marines, and coastwatchers, aided after 3 July by the 1st Company, South Pacific Scouts, under Capt. Charles W. H. Tripp of the New Zealand Army, was still being carried on. The advance westward was ready to begin.

Rice Anchorage

While 43rd Division troops were establishing themselves at Zanana, Colonel Liversedge’s Northern Landing Group was boarding ships at Guadalcanal and making ready to cut the Japanese communications north of Munda. The Northern Landing Group was originally to have landed on 4 July, but the delays in getting a foothold at Zanana forced Turner to postpone the landing, and all other operations, for twenty-four hours.

Because the Bairoko–Enogai area, the New Georgia terminus of the Japanese seaborne line of communications, was strongly held, and because preinvasion patrols had reported the Wharton River to be unfordable from the coast to a point about six thousand yards inland, Turner and Liversedge had decided to land at Rice Anchorage on the south bank of the river about six hundred yards

inland.29 Supervised by Capt. Clay A. Boyd, USMC, and Flight Officer J. A. Corrigan of the RAAF and the coastwatchers, native New Georgians cleared the landing beach and bivouac areas inland, and began hacking two trails from Rice Anchorage to Enogai to supplement the one track already in existence.

The organization of Liversedge’s Northern Landing Group was somewhat odd; the group consisted of three battalions from three different regiments. The 3rd Battalions of the 145th and 148th Infantry Regiments of the 37th Division and the 1st Raider Battalion, 1st Marine Raider Regiment, made up the force.30 And the force was lightly equipped. In order to permit rapid movement through the thick jungles and swamps of the area north of Munda, the troops took no artillery of any kind. Machine guns and mortars were their heaviest organic supporting weapons.

The battalions boarded the APDs, destroyers, and minesweepers at Guadalcanal on the afternoon of 4 July. The troops carried one unit of fire and rations for three days; five days’ rations and one unit of fire were stowed as cargo. Escorted by Rear Adm. Walden L. Ainsworth’s three light cruisers and nine destroyers, the speedy convoy started up the Slot at dusk. Shortly before midnight of a dark, rainy night, the ships rounded Visuvisu Point and entered Kula Gulf. Ainsworth bombarded Vila and then Bairoko Harbour with 6-inch and 5-inch shells, while the transport group headed for Rice Anchorage.

As the cruisers and destroyers were concluding their bombardment, the destroyer Ralph Talbot’s radar picked up two surface targets as they were leaving the gulf. These were two of three Japanese destroyers which had brought the first echelon of four thousand Japanese Army reinforcements down from the Shortland Islands.31 The Japanese ships had entered Kula at the same time as Ainsworth; warned by his bombardment, they were clearing out, but fired torpedoes at long range. One scored a fatal hit on the destroyer Strong. As two other destroyers were taking off her crew, four 140-mm. Japanese seacoast guns at Enogai opened fire, joined soon by the Bairoko batteries, but did no damage.32

Liversedge’s landing started about 0130, just after Ainsworth’s bombardment ceased. The APDs unloaded first, then destroyers, finally minesweepers. Each LCP(R) towed one ten-man rubber boat to shore. The way was marked by native canoes and shore beacons. The Japanese batteries harassed the troops but did not hit anything. There were no Japanese on the landing beach.

Nonetheless the landing was attended by troubles. A shallow bar obstructed the mouth of the Wharton River so effectively that many boats were grounded and later craft got over the bar only by coming in with lighter loads. The landing beach was too small to accommodate

more than four boats at once, and the river mouth was thus continually jammed with loaded boats waiting their turns at the beach. Also, about two hundred men of the 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry, were landed at Kobukobu Inlet, several hundred yards north of Rice Anchorage, a mishap which may have occurred because of the darkness of the night. Some days elapsed before the two hundred men made their way through the jungle to catch up with their battalion.

As dawn of 5 July was breaking, the volume of fire from the Enogai batteries against the ships was increasing, and it seemed unwise to risk this fire in daylight as well as to invite air attack. All but seventy-two troops and 2 percent of the cargo had been put ashore. Therefore, the convoy commander withdrew. Liversedge, with nearly all his three battalions ashore and under his control, made ready to move south.

Thus by 5 July TOENAILS was over. Throughout the complicated series of operations certain characteristics stood out. The weather had been consistently foul. The Japanese had not been able to resist effectively. The American performance, in spite of several instances of confusion, was very good, in that six landings in all had been carried out according to a complicated schedule that called for the most careful coordination of all forces. Clearly, Admiral Turner’s reputation as an amphibious commander was well founded.

The Americans had now established themselves in New Georgia. Viru Harbor and Wickham Anchorage were secure points on the line of communications. The airfield at Segi Point was nearing completion. And at Rice Anchorage and Zanana General Hester’s Munda–Bairoko Occupation Force was making ready to strike against Munda airfield.