Chapter 9: XIV Corps Offensive

The plan for the XIV Corps’ drive against Munda was completed shortly after Griswold took over.1 Col. Eugene W. Ridings, Griswold’s assistant chief of staff, G-3, flew to Koli Point to confer with General Harmon and Admiral Wilkinson on naval gunfire and air support. Ridings also asked for, and obtained, a better radio (SCR 193) for Liversedge, to improve communications between him and Griswold. Harmon stressed the importance of submitting a precise plan for air support to Admiral Mitscher. Dive bombers would naturally be the best for close work, while mediums and heavies should be used for area bombing, he asserted. Harmon agreed to send in more tanks at Griswold’s request.2

Plans

The American Plan

Naval support plans called for a seven destroyer bombardment of Lambeti Plantation shortly before the infantry’s advance. Comdr. Arleigh A. Burke, the destroyer division commander, came to Rendova on 23 July to view Roviana Lagoon and select visual check points. Air support for the offensive would include, besides the normal fighter cover, pattern bombing by multi-engine planes in front of the 43rd Division about halfway between Ilangana and Lambeti Plantation. Single-engine planes would strike at positions north and northeast of Munda field. Artillery spotting planes and liaison planes would be on station continuously.

Artillery support would be provided by Barker’s artillery from its island positions. Plans called for fairly standard employment of the field artillery, providing for direct and general support of the attack, massing of fires in each infantry’s zone of advance, counterbattery fire, and the defense of Rendova against seaborne and air attack. One 105-mm. howitzer battalion was assigned to direct support of each regiment, one 155-mm. howitzer battalion to general support of each division. Except for specific direct and general support missions, all artillery would operate as the corps artillery under Barker. The XIV Corps had neither organic artillery nor an artillery commander.3

Griswold’s field order, issued on 22

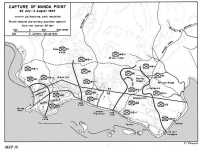

July, directed his corps to attack vigorously to seize Munda airfield and Bibilo Hill from its present positions which ran from Ilangana northwest for about three thousand yards. (Map 10) The 37th Division was to make the corps’ main effort. Beightler’s division was to attack to its front, envelop the enemy’s left (north) flank, seize Bibilo Hill, and drive the enemy into the sea. At the same time it would protect the corps’ right flank and rear. The 43rd Division was ordered to make its main effort on the right. Its objectives were Lambeti Plantation and the airfield. Liversedge’s force, depleted by the abortive attack on Bairoko, was to continue patrolling and give timely information regarding any Japanese move to send overland reinforcements to Munda. The 9th Defense Battalion’s Tank Platoon would assemble at Laiana under corps control. The 1st and 2nd Battalions, 169th Infantry, at Rendova, constituted the corps reserve.4

All units were ordered to exert unceasing pressure on the enemy. Isolated points of resistance were not to be allowed to halt the advance, but were to be bypassed, contained, and reduced later. Griswold ordered maximum use of infantry heavy weapons to supplement artillery. Roads would be pushed forward with all possible speed.

D Day was set for 25 July. The thirty minute naval bombardment was to start at 0610, the air bombing at 0635. The line of departure, running northwest from Ilangana, was practically identical with the American front lines except in the zone of the 161st Infantry where the existence of the Japanese strongpoint east of the line had been determined on 24 July.

The XIV Corps was thus attempting a frontal assault on a two-division front, with the hope of effecting an envelopment on the north. In the initial attack it would employ two three-battalion regiments (the 161st and the 172nd) and three two-battalion regiments (the 103rd, the 145th, and the 148th).

Enemy Positions and Plans

On 22 July the Japanese front line ran inland in a northwesterly direction for some 3,200 yards. This line was manned by the entire 229th Infantry, and at the month’s end the 2nd Battalion, 230th Infantry, was also assigned to it. In support were various mountain artillery, antitank, antiaircraft, and automatic weapons units.5 The positions were the same complex of camouflaged and mutually supporting pillboxes, trenches, and foxholes that had halted Hester in midmonth. The pillboxes started near the beach at Ilangana and ran over the hills in front of the 103rd, 172nd, 145th, and 161st Regiments.

Map 10: Capture of Munda Point, 22 July–4 August 1943

A particularly strong series lay on a tangled set of jungled hills: Shimizu Hill in front of the 172nd Infantry, and Horseshoe Hill (so named from its configuration) in front of the 145th and 161st Regiments. Horseshoe Hill lay northwest of Kelley Hill and west of Reincke Ridge. East of Horseshoe Hill lay the Japanese pocket discovered by the 161st. The pocket lay on a north-south ridge that was joined to Horseshoe Hill by a rough saddle. The pillbox line terminated at about the northern boundary of the 161st Infantry. When the 2nd Battalion, 230th Infantry, was committed it did not occupy carefully prepared positions. From the end of the pillboxes the line ran west to the beach, and this north flank does not seem to have been strongly held.

XIV Corps headquarters still estimated that four enemy battalions faced it; three at Munda and one at Bairoko. This was a fairly accurate estimate of strength on the enemy line, but Sasaki had an ace up his sleeve—the 13th Infantry. This regiment, which was not in full strength, was stationed on the American right flank about 4,900 yards west by north from Ilangana. Sasaki’s plans to use his ace were similar to his earlier plans. On the same day that Griswold issued his field order, Sasaki directed Colonel Tomonari to attack the American right flank in the vicinity of Horseshoe Hill on 23 July, then drive east along the Munda Trail. But the Americans struck before Tomonari made his move.

Ilangana and Shimizu Hill: The 43rd Division

In the 43rd Division’s zone, the offensive began as scheduled on the morning of 25 July. For once the weather was favorable. D Day dawned fair and clear, with visibility as good as could be expected in the jungle.

Naval gunfire, air, and artillery preparations went off as scheduled. Commander Burke’s seven destroyers had sailed up from Tulagi. At 0609 the two screening destroyers fired the first of four thousand 5-inch shells at Lambeti Plantation; these were followed by the main group at 0614. Visibility to seaward was good, but the morning haze still hung over Lambeti Plantation. Fifteen minutes later visibility had improved but now the target area was partly obscured by smoke and dust raised by the bombardment.6 Firing ceased at 0644.

From 0630 to 0700, 254 aircraft unloaded 500,800 pounds of fragmentation and high explosive bombs on their target area, a 1,500-by-250-yard strip beginning about 500 yards west of the 103rd Infantry’s front lines. No corps artillery concentrations were fired on 25 July, but the 43rd Division’s supporting artillery began before 0700 the first of more than 100 preparations that were fired

that day. The 103rd and 152nd Field Artillery Battalions fired more than 2,150 105-mm. howitzer shells; the 155-mm. howitzers of the 136th Field Artillery Battalion threw 1,182 rounds at the enemy.

With the din subsiding as the artillery shifted its fire to positions farther west, the infantrymen of the 43rd Division moved to the attack at 0700. In the 172nd Infantry’s zone the 2nd and 3rd Battalions on the left and right attacked westward against Shimizu Hill. But by 1000 they had run into the enemy pillbox line and halted. Colonel Ross then requested tanks, got some from the corps reserve, and attacked again. By 1430 three tanks were disabled, and the attack stalled. A little ground had been gained on the regimental left.

The 103rd Infantry, now commanded by Colonel Brown, attacked alongside the 172nd with little more success.7 The 3rd Battalion, on the left, pushed forward against machine gun and mortar fire, but immediately hit the Japanese line and stopped. The battalion attempted to move around the pillboxes but found that this maneuver took its men into other machine gun fire lanes.

The 2nd Battalion, 103rd, in the center of the 43rd’s zone, did better. It moved forward two or three hundred yards against light opposition. By 1040 E Company’s leading elements had advanced five hundred yards. The company kept moving until noon, when it had reached the beach near Terere. Here it set up a hasty defense position. But the companies on either flank had not been able to keep up, and the Japanese moved in behind E Company to cut the telephone line to battalion headquarters.

To exploit E Company’s breakthrough, General Hester took the 3rd Battalion, 169th Infantry, out of division reserve and ordered it to push through the same hole E Company had found. But the Japanese had obviously become aware of the gap, and as the 3rd Battalion marched to the line of departure it was enfiladed by fire from the south part of Shimizu Hill and from the pillboxes to the south. It halted. Five Marine tanks were then ordered to push over Shimizu Hill but could not get up the steep slopes. When three of them developed vapor lock all were pulled back to Laiana. In late afternoon the E Company commander decided to abandon his exposed, solitary position, and E Company came safely back through the Japanese line to the 2nd Battalion.

North of the 43rd Division the 37th Division had made scant progress.8 Thus the first day of General Griswold’s offensive found the XIV Corps held for little gain except in the center of the 43rd Division’s line.

The 43rd Division was weakened by almost a month’s combat, and its reduced strength was spread over a long, irregular, slanting front. It was obvious that combat efficiency would be increased by narrowing the front, and this could be done by advancing the left and straightening the line. Consequently Hester’s plan for 26 July called for the 172nd to stay in place while the 103rd Infantry attempted to advance the eight

hundred yards from Ilangana to Terere.

Strong combat patrols went out in the morning of 26 July to fix the location of the Japanese pillboxes as accurately as possible. After their return, the artillery began firing at 1115, one hour before the infantry was to attack. At 1145 the 103rd’s front was covered with smoke and under its cover the front-line companies withdrew a hundred yards. At noon the artillery put its fire on the Japanese positions directly in front. As the tanks were not quite ready at H Hour, 1215, the artillery kept firing for ten more minutes. It lifted fire one hundred yards at 1225, and the 103rd started forward. The tanks led the advance in the center; behind them was the infantry. Attached to the 103rd for the attack were 2nd Lt. James F. Olds, Jr., the acting corps chemical officer, and six volunteers from the 118th Engineer Battalion. Each carried a flame thrower, a weapon which the 43rd Division had brought to New Georgia but had not used up to now.9 Griswold, whose headquarters had conducted flame thrower schools on Guadalcanal, was aware of the weapon’s possibilities. That morning the six engineers had received one hour of training in the use of the M1A1 flame thrower.

The flame throwers went forward with the infantry, which halted about twenty yards in front of the pillbox line and covered it with small arms fire. Under cover of this fire the flame thrower operators, their faces camouflaged with dirt, crawled forward. Operating in teams of two and three, they sprayed flame over three barely visible pillboxes in front of the center of the 103rd’s line. Vegetation was instantly burned off. In sixty seconds the three pillboxes were knocked out and their four occupants were dead.10

Operations of the infantry, tanks, flame throwers, and supporting heavy weapons and artillery met with almost complete success. The 103rd Infantry encountered seventy-four pillboxes on a 600-yard front, but by midafternoon, spurred on by pressure from General Wing, it had reduced enemy resistance at Ilangana. From there it continued its advance through underbrush and vines and gained almost 800 yards. By 1700 the left flank rested on the coastal village of Kia. The 43rd Division’s line, formerly 1,700 yards long, was now much straighter by 300 yards.

From 28 through 31 July, the 43rd Division inched slowly forward, a few yards on the right flank and about five hundred yards along the coast. This was accomplished by “aggressive action and small unit maneuver, combined with constant artillery and mortar action [which] gradually forced the enemy back from his high ground defenses.”11 The 172nd ground its way over Shimizu Hill, the last real ridge between it and Munda airfield, and in doing so it helped unhinge the main Japanese defense system in its zone, just as the 103rd’s drive

through Ilangana had broken the enemy line on the left.12

Major Zimmer’s 1st Battalion, 169th Infantry, was brought over from Rendova on 29 July; the 3rd Battalion, now commanded by Maj. Ignatius M. Ramsey, was taken out of division reserve and the 169th (less the 2nd Battalion) was assigned a zone between the 172nd and the 103rd.13 As the month ended the 169th (less its 2nd Battalion in corps reserve) was in the process of extending to the northwest to pinch out the 172nd.

Command of the 43rd Division changed hands on 29 July when Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge, the tough, blunt commander of the Americal Division, came up from the Fijis to take over from Hester. This change was ordered by General Harmon who felt that Hester had exhausted himself. General Hodge had served as assistant commander of the 25th Division during the Guadalcanal Campaign, and thus had had more experience in jungle warfare than any other general then in New Georgia. Hodge, Harmon wrote, was the “best Div Comdr I have in area for this particular job.”14

The 43rd Division, having cracked through the Shimizu Hill–Ilangana positions, was in a favorable position to drive against Munda under its new commander, while the 37th Division on its right fought its way through the enemy positions in its hilly, jungled zone.

The Attack Against the Ridges: The 37th Division

The dawn of D Day, 25 July, found the 43rd Division committed to a general attack, but the 37th Division was forced to postpone its advance. General Beightler had issued a field order on 23 July calling for a general attack by his three regiments, to start at 0700, 25 July. The 145th, 161st, and 148th Infantry Regiments were to attack due west, toward Bibilo Hill, on the division’s left, center, and right, with the 145th maintaining contact with the 172nd Infantry on its left and the 148th Infantry covering the corps’ right flank and rear. But the discovery of the strong Japanese position east of the 161st Infantry’s line of departure altered the plans.

On 24 July Beightler ordered Colonel Holland not to advance his 145th Infantry, but to stay in place. He told Colonel Baxter to move the 148th Infantry only up to the line of departure. The two regiments would hold while part of the 161st contained the Japanese position and the rest of the regiment bypassed it and came up on a line with the 145th and 148th.

After Baxter received the commanding general’s orders, he suggested that his regiment could perhaps help the 161st reduce the pocket by making a limited advance. Baxter hoped to establish an observation post on high ground from which both Munda airfield and the pocket in front of the 161st could be

seen. Beightler assented to this request at 0910, 25 July. Patrols went out, and on their return the direct support artillery battalion laid a ten-minute preparation 400 yards in front of the line of departure while mortars covered the 400-yard gap. The 2nd Battalion, 148th, commanded by Lt. Col. Herbert Radcliffe, started forward, met no Japanese, and gained 500-600 yards.15 The 1st Battalion, Lt. Col. Vernor E. Hydaker commanding, moved up to the 2nd Battalion’s old positions.

Bartley Ridge and Horseshoe Hill

When I Company, 161st Infantry, had been unable to reduce the Japanese strongpoint on Bartley Ridge on 24 July, Colonel Dalton issued orders for its seizure on D Day.16 I Company was to contain the Japanese pocket by attacking to its front while the 1st Battalion and the rest of the 3rd Battalion executed a double envelopment.17 The 1st Battalion was to move around the Japanese left (north) flank while the 3rd Battalion went around the right, after which the two battalions would drive southward and northward for two hundred yards. Fifteen minutes of mortar fire would precede these moves. Beightler arranged for the 145th and 148th Regiments to support the 161st with heavy weapons fire. He also asked corps headquarters for tanks to help the 161st, but the 43rd Division had been given the tanks for the D-Day attack.

From positions near the Laiana Trail eight 81-mm. mortars opened fire at 0745, 25 July, in support of Dalton’s attack. Heavy weapons of the adjoining regiments attempted to deliver their supporting fires, but the denseness of the jungle prevented forward observers’ controlling the fire. The unobserved fire began obstructing rather than helping the 161st, and that part of the plan was abandoned.

The 3rd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. David H. Buchanan, was unable to gain. Shortly after 0800, when the attack began, I Company reported that its attack against the ridge strongpoint had stalled. A knob projecting east from Bartley Ridge and the heavy undergrowth provided enough cover and concealment to let the infantrymen reach the base of the ridge, but uphill from the knob, where the growth was thinner, all movement was halted by fire from the crest. The 161st Infantry had made plans to use flame throwers, and an operator carrying his sixty-five pounds of equipment made two laborious climbs and silenced an enemy machine gun, but many other Japanese positions remained in action. The main body of the 3rd Battalion, attempting to get around the south end of Bartley Ridge, was also halted.

The 1st Battalion was more successful. At 1035 its commander, Lt. Col. Slaftcho Katsarsky, radioed Dalton that he had found the north flank of the Japanese position on Bartley Ridge, and

that he was moving his battalion around it. Shortly afterward Beightler, Dalton, and staff officers conferred and decided that the 3rd Battalion should contain the strongpoint while the 1st Battalion pushed westward with orders to develop enemy positions but not to engage in full-scale combat. The 37th Division could not advance westward in force until Bartley Ridge had been cleared.

The 3rd Battalion established itself in containing positions north, east, and south of Bartley Ridge. E Company was released from reserve and sent into line on high ground just north of Bartley to secure the right flank in the 161st’s zone. The 1st Battalion advanced to a point about four hundred yards west of Bartley and halted on a small rise northeast of Horseshoe Hill. Tanks of the newly arrived 10th Marine Defense Battalion were to be committed to support the 37th Division the next day, and in the afternoon the tank commander made a personal reconnaissance of Colonel Buchanan’s zone in preparation for the attack.

Six light Marine tanks were to lead out in the attack at 0900, 26 July, after preparatory fire by machine guns and 81-mm. mortars. L and K Companies, in column, would move behind the tanks, which were supported by infantrymen armed with .30-caliber M1 rifles, .30 caliber Browning Automatic Rifles (BARs), and two flame throwers. Tank infantry communication was indirect. The tank radios formed a net within the Tank Platoon, and a 161st radio car maintained radio contact between the Tank Platoon commander and Colonel Buchanan.

When the tanks, with their hatches closed, got off the approach trail that had been bulldozed by members of the 65th Engineer Battalion, Colonel Buchanan directed the infantrymen to lead them forward. It was 0925 before the attack got started. In two lines of three vehicles each, the tanks lumbered over the littered undergrowth, steep slopes, and felled logs toward the southeast slope of Bartley Ridge. The Japanese quickly responded with fire from antitank and 70-mm. battalion guns, machine guns, and mortars.

The attack went well at first. About a dozen pillboxes were reported knocked out by 1110, and Buchanan ordered his men to occupy them to keep the Japanese from moving in again at night. Unfortunately, the tanks had encountered exactly the sort of difficulties that might be expected in tangled terrain with communications uncertain. In their lurches and frequent changes of direction they injured some of the accompanying foot troops. Poor visibility caused them to get into untenable positions from which they had to be extricated with consequent delays to the attack. During the morning a Japanese soldier stole out of the tangled brush and planted a magnetic mine that disabled one tank. A second tank was halted by a ruptured fuel line. The remaining four withdrew at 1110 to reorganize.

The flame thrower operators, carrying their bulky, heavy fuel tanks on their backs, were not properly protected by the riflemen and were soon killed.

In the course of the day’s fighting some fourteen pillboxes and a number of machine gun positions were knocked out, and the 3rd Battalion advanced about

two hundred yards up Bartley Ridge.18 But it met such heavy fire from Bartley and Horseshoe Hill that its position clearly could not be held. Attempts to pull out the disabled tanks were unsuccessful. The battalion withdrew to its previous positions. The attack had disclosed the existence of so many more positions that Dalton received Beightler’s permission to make a thorough reconnaissance before attacking again.

While the 161st was attacking Bartley Ridge on 25 and 26 July, Colonel Holland’s 145th Infantry stayed in its forward positions on Reincke Ridge and Kelley Hill. During this period it sent out patrols to the north and west to try to find the source of the 90-mm. mortar fire that had been hitting the regiment since 22 July. It received no artillery support at this time because its front line was considered too close to enemy targets for the artillery to fire without hitting American infantry. By the end of 26 July the 1st Battalion, 161st, had fought its way forward to come up on line north of the 145th, but near the regimental boundary the line sagged eastward in the shape of a great U. Colonel Parker’s 2nd Battalion, 145th, was occupying positions in rear of the 1st Battalion, 145th, commanded by Lt. Col. Richard D. Crooks.

General Beightler ordered Holland to commit his 2nd Battalion, in order to reduce the Japanese positions on Horseshoe Hill that had fired on the 3rd Battalion, 161st, during its 26 July attack against Bartley Ridge. Doubtless because troops of the 161st had not been able to get past the south end of Bartley, Colonel Parker’s battalion was to march northward right around the 3rd Battalion, 161st, push west around the north of the enemy positions on Bartley Ridge, then attack to the southwest. This maneuver would entail a march of about one and one-half miles to the assembly area.

Parker’s battalion moved out in the early morning of 27 July. It reached its assembly area on the north flank of Bartley Ridge without incident. After a preparation of one hundred rounds by the division artillery, which cleared some of the foliage, the battalion advanced to the attack in column of companies. “Having to fight every foot of the way,” it gained about three hundred yards before 1300, when E Company in the lead moved south off slopes of a ridge and started up a small knob projecting from Horseshoe Hill.19 As the company ascended the hill it was struck by fire from pillboxes. Among the first men killed was Capt. Gardner B. Wing, E Company’s commander, in whose honor the 145th christened the knob.

On the same day, while American mortars fired intermittently at Bartley Ridge, patrols from the 3rd Battalion, 161st Infantry, examined the Japanese lines to procure data for a preparation by the corps artillery. In the course of the reconnaissance Colonels Dalton and Buchanan observed enemy pillboxes on the right flank of the 1st Battalion, 145th

Infantry, and recommended that the attack be delayed until 29 July.20 General Beightler gave his assent. Dalton and Buchanan also decided to attack from the northwest instead of the southeast. Reconnaissance and pressure were to continue on the 28th.

On the morning of the 28th a ten-man patrol from I Company, led by Lt. Walter Tymniak, set out in a southerly direction toward the top of Bartley Ridge. To their surprise and satisfaction, the Americans met no fire, got safely to the top, and found several abandoned pillboxes. They occupied them, and I Company followed to the crest and began infiltrating the pillboxes. Not all were vacant, but the task of the attackers was eased as each pillbox was taken, for its fire could then no longer be used with that of its neighbors to make crossfire or interlocking bands of fire. Because the Japanese appeared to be evacuating and the American front was intermingled with the enemy front, the artillery preparation was called off. The 3rd Battalion continued its infiltration on 29 July. At the end of the day it was relieved by Maj. Francis P. Carberry’s 2nd Battalion and went into division reserve.

The 145th Infantry’s zone was shifted farther north on 30 July as part of a general shift in boundaries that General Griswold was making in order to widen the 43rd Division’s front. This move placed the southern half of Bartley Ridge within the 145th’s zone. Colonel Parker’s 2nd Battalion, 145th, had just completed its move around the 161st’s north flank, thence southwest against Horseshoe Hill. On 30 July it was attached to the 161st for the completion of the reduction of Bartley Ridge and Horseshoe Hill.

Carberry’s and Parker’s battalions pushed their attacks on 30 July. In contrast with Carberry’s battalion, which met little resistance, Parker’s men engaged in sharp fighting in the west. The Japanese who had evacuated the position facing Carberry had apparently moved into positions facing Parker. With grenade, rifle, machine gun, mortar, and flame thrower the two battalions fought all day and part of the next, until by midafternoon of 31 July the Japanese rear guards on Bartley Ridge were either dead or in flight, and the 2nd Battalion, 161st, had advanced west and was on a line with the 1st. Bartley Ridge had contained forty-six log and coral pillboxes and thirty-two other lighter positions. First attacked by a company, it fell only after seven days’ fighting by two battalions.

On Horseshoe Hill the Japanese resisted from their pillboxes and foxholes with equal skill and enthusiasm. The Americans used small arms, grenades, automatic weapons, mortars, flame throwers, and field artillery as they systematically reduced the enemy positions, almost pillbox by pillbox.21 On 1 August Parker’s battalion received orders to attack in late afternoon, obeyed, and took Horseshoe Hill without firing a shot or losing a man. The Japanese had gone.

Advance and Withdrawal of the 148th Infantry

On 1 August, the day on which the Americans completely occupied the ridge positions, the 148th Infantry returned eastward to the 37th Division’s lines after an advance which had taken it almost to Bibilo Hill. The 148th Infantry was the only regiment not confronted by prepared enemy positions, and it had made comparatively rapid progress from the first. When Colonel Baxter moved his regiment forward on 25 July, it went around the north flank of the Japanese defense line and met no resistance. However, none of the Americans then knew that the major part of the enemy 13th Infantry lay to the north of Baxter’s right flank. Patrols, accompanied by Fiji scouts, went out and reported the presence of a few Japanese to the west, none to the south. Generals Griswold and Beightler had emphasized the importance of maintaining lateral contact and Beightler had expressly directed that the 148th was to maintain contact with the 161st, and that all units were to inform their neighbors and the next higher unit of their locations. The 148th, however, was not able to make contact on its left with the 161st Infantry.

Baxter’s two-battalion regiment advanced regularly for the next three days. Colonel Radcliffe’s 2nd Battalion led on 26 and 27 July; on 28 July Colonel Hydaker’s 1st Battalion bypassed the 2nd and led the advance to a point somewhere east of Bibilo Hill.22 Patrols went out regularly and at no time reported the presence of a sizable body of the enemy. On 27 July Baxter reported that he had established “contact with Whiskers.” Colonel Dalton, the “guest artist” regimental commander of the attached 161st Infantry, sported a beard and was dubbed “Whiskers” and “Goatbeard” in the 37th Division’s telephone code. But the 148th’s front was almost a thousand yards west of Whiskers’ 1st Battalion, and the contact must have been tenuous. Next day G Company was ordered to move to the left to close a gap between the two regiments, but the gap stayed open.

During the move troops of the 117th Engineer Battalion labored to push a supply trail behind the advancing battalions. The rate of march was in part geared to the construction of the supply trail. As Baxter told Radcliffe over the telephone on 27 July, “I am advancing behind you as fast as bulldozer goes.”23 Next day, however, there occurred a disturbing event. A platoon from A Company, 117th Engineer Battalion, was using a bulldozer to build the trail somewhere north of Horseshoe Hill when it was ambushed by the enerny. Three engineers were killed and two were wounded before elements of the Antitank Company and of the 1st Battalion rescued the platoon and extricated the bulldozer.

Japanese movements during this period are obscure, but this and subsequent attacks were made by the 13th Infantry coming south at last in accordance with Sasaki’s orders.

The situation became more serious on 28 July, the day on which Baxter’s

aggressive movement took him almost to Bibilo Hill. At this time the regiment was spread thinly about fifteen hundred yards beyond the 161st; its front lay some twelve hundred yards west of the regimental ration dump and eighteen hundred yards from the point on the supply line “which could be said to be adequately secured by other division units.”24 There was still no contact with the 161st, and in the afternoon a group of the 13th Infantry fell upon the ration dump. From high ground commanding it the enemy fired with machine guns, rifles, and grenade discharges at men of the regimental Service Company. The Service Company soldiers took cover among ration and ammunition boxes and returned the fire. The dump, under command of Maj. Frank Hipp, 148th S-4, held out until relieved by two squads of the Antitank Company and one platoon from F Company. East of the dump, troops of the 13th Infantry also forced the 148th’s supply trucks to turn back. Baxter, stating “I now find my CP in the front line,” asked Beightler to use divisional units to guard the trail up to the dump.25

All the 148th’s troubles with the Japanese were in the rear areas. The westward push, which took the leading battalion as far as one of the Munda–Bairoko trails, had been practically unopposed. But early on the morning of 29 July General Beightler, unaware of the 13th’s position, telephoned Baxter to say that as the Japanese seemed to be moving from the southwest through the gap between the 148th and 161st Regiments, and around the 148th’s right, Baxter was to close up his battalions and consolidate his positions. At 0710 Beightler told Baxter to withdraw his battalions to the east, to establish contact with the 161st, and to protect his supply route. Baxter, who had sent patrols out in all directions early in the morning, at 0800 ordered one company of the 2nd Battalion to clear out the supply trail to the east. At 0941, with Japanese machine guns still dominating the supply trail, Beightler sent Baxter more orders similar to those of 0710, and also ordered forward a detachment of the 37th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop to help clear the east end of the supply trail. The telephone, so busy with conversations between Beightler and Baxter on 29 July, was then quiet for an hour.

Meanwhile Beightler had been conferring with Dalton, Holland, and members of the divisional general staff. As a result he had decided that the 161st should continue reducing Bartley Ridge, that the 145th should stay in place, and that the 148th would have to withdraw. So at 1055 Baxter ordered his regiment to turn around and pull back to the east. The 2nd Battalion, 148th, was to use at least one company to establish contact with the 161st while the rest of the battalion withdrew toward the ration dump. The 1st Battalion would move back to the 2nd Battalion’s positions. At 1150 Baxter reported the 2nd Battalion in contact with the 161st, and shortly afterward Beightler ordered Baxter to move the 1st Battalion farther east, putting it in position to deliver an attack the next morning against the rear of the Japanese holding up Dalton’s regiment. The division commander again

emphasized the necessity for maintaining firm contact with the 161st.26 At 1305, with the 148th moving east, Colonel Katsarsky reported that his 1st Battalion, 161st, had as yet no contact with the 148th. Beightler at once told Baxter that, as Japanese machine gunners were operating between the two regiments, the gap must be closed before dark. An hour later Baxter called Beightler to say that he was too far west to close with the 161st before dark. When Beightler ordered him to close up anyway, Baxter demurred. Asking his general to reconsider the order, he stated that he could almost, but not quite, close the gap. Beightler thereupon told Baxter to comply with his orders as far as was physically possible.

The 2nd Battalion had meanwhile been pushing east, except for F Company’s main body, which was advancing west toward the ration dump. Both bodies were encountering enemy resistance, and the day ended before the Japanese were cleared out. The Reconnaissance Troop cleared some Japanese from the eastern part of the supply trail, but at 1758 Baxter reported that the trail had been closed by raiding Japanese.

The 148th Infantry, in examining the personal effects of some of the dead Japanese, found that the men belonged to the 13th Infantry. Some of them had been carrying booty taken in the raids east of the Barike several days earlier. Colonel Baxter later estimated that the enemy harrying his regiment numbered no more than 250, operating “in multiple small light machine gun and mortar detachments and ... [moving] from position to position utilizing the jungle to its maximum advantage. You can well imagine what we could do with our M-1s, BARs and Machine Guns if all we had to do was dig in and wait for the Jap to come at us.”27

General Beightler, a National Guardsman most of his life, was an affable man, but he was far from satisfied with the outcome of the day’s action.28 At 1832 he radioed Baxter that General Griswold had ordered the 148th to establish contact with the 161st early the next morning and to protect the supply route. “Use an entire battalion to accomplish latter if necessary. At no time have you been in contact on your left although you have repeatedly assured me that this was accomplished ... Confirmation of thorough understanding of this order desired.” Baxter thereupon telephoned division headquarters and put his case before a staff officer. General Beightler’s criticism, he felt, was not justified. “Please attempt to explain to the General that I have had patrols in contact with the 161 and have documentary evidence to substantiate this. I have not, however, been able to maintain contact and close the gap by actual physical contact due to the fact that the 161st had been echeloned 600 to 800 yards to my left rear. I have been trying and will continue tomorrow

morning to establish this contact. It is a difficult problem as I have had Japs between my left flank and the 161st.”29

Rain and mud added to Baxter’s troubles on 30 July. Still harried by enemy machine guns and mortars, the 2nd Battalion pushed east and south toward the 161st as the 1st Battalion covered the left (north) flank. Elements of the 37th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, C Company, 117th Engineer Battalion, and the 3rd Battalion, 161st Infantry, pushed north to give additional protection to the division’s right (north) flank and to protect the east end of Baxter’s supply route. Baxter attempted to cut a new trail directly into the 161st’s lines, but Japanese rifle fire forced the bulldozer back. Some of the 148th’s advance elements sideslipped to the south and got through to the 161st that day, but the main body was still cut off.30 Some of the Japanese who were following the 148th attacked the 1st Battalion, 161st, but were halted. This action then settled down into a nocturnal fire fight.

The plight of the rest of the regiment was still serious. Water was running low. Part of the Reconnaissance Troop tried to take water forward to the 148th on 30 July. It was stopped by Japanese fire. But rain fell throughout the night of 30-31 July and the thirsty men were able to catch it in helmets and fill their canteens.

On 31 July Beightler suggested that Baxter destroy heavy equipment and break his regiment into small groups to slip northward through the jungle around the enemy. The 148th blew up all the supplies it could not carry but it had to fight its way along the trail. It had over a hundred wounded men and could not infiltrate through the jungle without abandoning them.

Toward the end of the day B Company, which had been trying to clear the Japanese north of the supply trail, was ordered to disengage and withdraw slightly for the night. One of B Company’s platoons, however, had come under fire from a Japanese machine gun about seventy-five yards to its front and found that it could not safely move. Pvt. Rodger Young, who had been wounded in the shoulder at the first attempt to withdraw, told his platoon leader that he could see the enemy gun and started forward. Although a burst from the gun wounded him again and damaged his rifle, he kept crawling forward until he was within a few yards of the enemy weapon. As a grenade left his hand he was killed by a burst that struck him in the head. But he had gotten his grenade away, and it killed the Japanese gun crew. His platoon was able to withdraw in safety. For his gallantry and self-sacrifice Young was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.31

Colonel Baxter’s radio fairly crackled the next morning, 1 August, with orders from General Beightler: “Time is precious, you must move.” “Get going.”

“Haste essential.”32 Thus urged on, Baxter ordered an assault by every man who could carry a rifle. He formed all his command—A, E, B, and G Companies—in a skirmish line with bayonets fixed, and assaulted by fire and movement at 0850. The attack succeeded. By 0930 the leading elements, ragged, weary, and muddy, reached Katsarsky’s area. The 148th was given fresh water and hot food, then passed into division reserve. As the men struggled in after their ordeal, all available ambulances, trucks, and jeeps were rushed up to transport the 128 wounded men to the 37th Division’s clearing station at Laiana.

Capture of the Airfield

The first day of August had broken bright and clear after a night of intermittent showers. It is likely that the spirits of the top commanders were also bright, for things were looking better. With Ilangana and Shimizu Hill reduced, the 43rd Division was in possession of the last piece of high ground between it and Munda airfield. Bartley Ridge had fallen; Horseshoe Hill was about to fall, and the 148th was completing its retirement.

General Griswold had issued no special orders for the day; the field order that had started the corps offensive was still in effect. In the 37th Division’s zone the most significant development was the return of Baxter’s men. The 145th Infantry was patrolling; the 161st was mopping up. In the 43rd Division’s area of responsibility, General Hodge had ordered an advance designed to bring his division up on line with the 145th Infantry.

The 103rd Infantry began its attack at 1100. E, G, and F Companies advanced in line behind patrols. Meeting practically no opposition, they gained ground rapidly and by 1500 were nearing Lambeti Plantation. The 2nd Battalion, 169th Infantry, then in process of pinching out the 172nd, attacked northwest across the front of the 172nd and established contact with the 145th Infantry. The 172nd completed a limited advance before going into division reserve. The 3rd Battalion, 169th, on the left of the 2nd, attacked in its zone and at 1500 was still advancing. For the first time since it had landed on New Georgia, the 43rd Division could announce that the going was easy.

The day before, Generals Hodge and Wing, accompanied by Colonel Ross, had visited the command and observation posts of the 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, from where they could see part of Munda airfield. They detected evidence of a Japanese withdrawal, which seemed to be covered by fire from the enemy still on Horseshoe Hill.

Thus at 1500, 1 August, with the 43rd Division still moving forward, General Griswold ordered all units to send out patrols immediately to discover whether the Japanese were withdrawing. “Smack Japs wherever found, even if late.”33 If the patrols found little resistance, a general advance would be undertaken in late afternoon. Colonel Ridings telephoned the orders to 37th Division headquarters, and within minutes patrols went out. They found no enemy. At 1624 Ridings called Beightler’s headquarters

again with orders to advance aggressively until solid resistance was met, in which case its location, strength, and composition were to be developed. The 148th Infantry was to have been placed in corps reserve with orders to protect the right flank, patrol vigorously to the north, northeast, and northwest, and cut the Munda–Bairoko trail if possible. Since the 27th Infantry of the 25th Division was arriving and moving into position on the 37th Division’s right flank, Beightler persuaded corps headquarters to let him use the 148th Infantry.34 Ridings required, however, that the 148th be given the mission of protecting the right flank because the 27th Infantry would not have enough strength for a day or two.

All went well for the rest of the day. The 103rd Infantry reached the outer taxiways of Munda airfield; the 169th pulled up just short of Bibilo Hill. The 37th Division’s regiments plunged forward past Horseshoe Hill, which was free of Japanese, and gained almost seven hundred yards.

The Japanese Withdrawal

The Japanese positions facing the XIV Corps had been formidable, and the Americans had been held in place for long periods. But the Americans had wrought more destruction than they knew. The cumulative effect of continuous air and artillery bombardment and constant infantry action had done tremendous damage to Japanese installations and caused large numbers of casualties. By late July most of the Japanese emplacements near Munda were in shambles. The front lines were crumbling. Rifle companies, 160-170 men strong at the outset, were starkly reduced. Some had only 20 men left at the end of July. The 229th Infantry numbered only 1,245 effectives. Major Hara, Captain Kojima, and many staff officers of the 229th had been killed by artillery fire. Hospitals were not adequate to care for the wounded and sick. The constant shelling and bombing prevented men from sleeping and caused many nervous disorders.

To compensate for the diminution of his regiment’s strength, Colonel Hirata ordered the soldiers of his 229th Infantry to kill ten Americans for each Japanese killed, and to fight until death.

Higher headquarters, however, took a less romantic view of the situation. On 29 July a staff officer from the 8th Fleet visited Sasaki’s headquarters and ordered him to withdraw to a line extending from Munda Point northeast about 3,800 yards inland. The positions facing the XIV Corps, and Munda airfield itself, were to be abandoned. Sasaki and his subordinates thought that it would be better to withdraw even farther, but the views of the 8th Fleet prevailed over those of the responsible men on the spot. The withdrawal, which was deduced by XIV Corps headquarters on 1 August, was accomplished promptly, and except for detachments at Munda and in the hills the main body of Sasaki’s troops was in its new position by the first day of August.

Jungle Techniques and Problems

The Americans did not yet know it, but the worst was over. All regiments began making steady progress each day

Munda Airfield

against light, though determined and skillful, opposition.35

By now all regiments, though depleted by battle casualties and disease, had become veterans. Pockets that once would have halted an entire battalion or even a regiment were now usually reduced with speed and skill. The flame thrower, receiving its most extensive use in the Pacific up to this time, was coming into its own as an offensive weapon. All regiments employed it against enemy positions, both in assault and in mopping up. The flame thrower did have several important disadvantages. The equipment was large and heavy, and required the operator to get very close to enemy positions, then expose his head and body in order to use his weapon. He needed to be protected by several riflemen. But even with its disadvantages, it was useful in destroying enemy positions.

Tanks, too, were of great value. General Griswold felt that, despite the difficulties inherent in operations over hilly jungle, the actions of the Tank Platoons

of the 9th and 10th Marine Defense Battalions had been successful. On 29 July, looking forward to fighting over easier terrain around Munda airfield, he asked General Harmon for more tanks. Corps headquarters, he also announced, was preparing to mount flame throwers on tanks.36 The operation ended before flame throwing tanks could be used, but the idea was successfully carried out in later campaigns.

The technique of reducing a pillbox, whether isolated or part of a defensive system, was now mastered. The official records unfortunately do not give much exact information on the reduction of specific pillboxes, but after the battle the 37th Division gave a valuable general description of the methods employed. The first essential was a complete reconnaissance to develop the position, intention, and strength of the enemy. This was quite difficult in the jungle. “To one unskilled in jungle fighting, it is inconceivable that well trained reconnaissance patrols in sufficient numbers cannot develop the situation in front of the advancing forces.”37 Because they could not see far enough, because they could not always get close enough, and because Japanese fire discipline was sometimes so good that a given position would not fire until actually attacked, reconnaissance patrols could not always develop positions. The next step was a reconnaissance in force by a reinforced platoon. This often uncovered a portion of the enemy position but not all of it. Usually the complete extent of a center of resistance was determined only by the attack.

The attack itself consisted of three parts: artillery preparation, 81-mm. mortar fire, and assault.

The artillery preparation had a three-fold effect. It improved visibility by clearing away brush and foliage. It destroyed or damaged enemy positions. And it killed, wounded, and demoralized enemy soldiers.

The 81-mm. mortars, using heavy shell that had a delay fuze, fired on observed positions and usually covered the area between the American infantry and the artillery’s targets. They frequently drove the Japanese soldiers out of their pillboxes into the open where they became targets for rifle and machine gun fire. The 60-mm. mortars, though more mobile than the 81-mm.’s, threw too light a shell to be very effective in these attacks. Their shells usually burst in the trees, but the 81-mm. heavy shells penetrated the treetops and often the tops of the pillboxes themselves before exploding.

The assault consisted of a holding attack by a company or platoon delivering assault fire to cover a close-in single or double envelopment. BARs, M1s, and grenades were used extensively, and flame throwers were employed whenever possible. Units of the 25th Division, which later drove northward from Munda to Zieta, encountered pillbox positions that were too shallow, and in country too dense, for artillery and mortars to be used without endangering the

Reducing an enemy pillbox with a flame thrower. Pillbox is along the beach near Munda Airfield

attacking infantry. Men of this division therefore advocated flame throwers, infantry cannon, and tanks for pillbox reduction.

These techniques, which simply represented the application of established tactical principles, were being applied well in early August, but several problems remained. Because the infantry units did not advance at the same rate, the front line became irregular and the supporting artillery was thus unable to capitalize on the advantages of firing at right angles to the axis of advance. All unit commanders were eager to employ artillery and mortar support to the utmost, but they frequently complained that neighboring units’ supporting artillery and mortar fires were falling in their areas and endangering their troops. They had a tendency to forget that the enemy also used artillery and mortars and, when receiving American artillery fire, frequently lobbed 90-mm. mortar shells into the American front lines to convince the American infantrymen that they were being fired on by their own artillery. In most cases the complaints were probably caused by Japanese rather than American fire.

Because maps were inaccurate and reconnaissance was inhibited by poor visibility, it was extremely difficult to determine the exact location of friendly units. In the 37th Division’s zone several artillery preparations were called off because

of uncertainty about the position of the 148th Infantry. Flares and smoke pots, and sometimes flame throwers, were used to mark flanks, but usually could not be seen by anyone not in the immediate vicinity. Griswold had ordered the front line battalions to mark their flanks daily with white panels twenty-five feet long by six feet wide. These were to be photographed from the air. Reconnaissance planes made daily photographic flights, but there were no clearings in the New Georgia jungle large enough to permit the panels to be spread out, and this effort failed. By plotting close-in defensive artillery fires, forward observers were able to provide some reliable information on the location of front lines. When the 37th Division rolled forward after 1 August, it estimated positions and distances on the basis of speedometer readings from locations that had been plotted by air photography and interpolated on maps.

The difficulties of scouting and patrolling naturally affected nearly every aspect of the operation. Because enemy positions could not be fixed in advance, the troops often attacked terrain rather than the enemy. This procedure resulted in slow advances and in a high expenditure of mortar ammunition on areas actually free of the enemy. And mortar ammunition supply was laborious; shells had to be hand-carried from trail-end to the mortar positions. Poor scouting caused battalions to advance on narrow fronts and thus be halted by small enemy positions. One regimental operations officer asserted that inadequate reconnaissance was due in part to the fact that “higher commanders” did not issue orders until the late afternoon preceding an attack. Thus battalions did not have time for full reconnaissance:

“Many times, units were committed in an area which had not been reconnoitered. This fact resulted in commanders having to make decisions concerning a zone of advance in which he knew little or nothing about the enemy positions. Enemy strong points encountered in this fashion often times resulted in hasty withdrawals which were costly both in men and weapons.”38

“Munda is yours”

The XIV Corps maintained the momentum of its advance against the enemy delaying forces. On 2, 3, 4, and 5 August the advance continued all across the corps’ front. The 103rd and 169th Infantry Regiments, which had gained the outer taxiways of the airfield on 1 August, kept going. The 3rd Battalion, 172nd, was committed on the 169th’s right on 4 August. In the more open terrain around the airstrip the troops were able to use 60-mm. mortars effectively, and their advance was consequently speeded. Kokengolo Hill, the rise in the center of the airfield where a Methodist mission had once stood, held up the advance temporarily. Bibilo Hill, whose fortifications included six 75-mm. antiaircraft guns that the Japanese had been using as dual-purpose weapons, was reduced in three days of action by elements of the 169th, 172nd, 145th, and 161st Regiments, supported by Marine tanks. The 148th Infantry, on the north flank, established blocks and ambushes on a north-south track

Light tanks M3 of the 9th Marine Defense Battalion supporting infantry action near the base of Bibilo Hill

that was presumed to be the Munda–Bairoko trail.

On 5 August, with Bibilo Hill cleared, the units of the 37th Division crossed the narrow strip of land between the hill and the water. This tactical success had one effect of great personal importance to the soldiers: many had their first bath in weeks.

In the 43rd Division’s zone on 5 August, the infantry, with tank and mortar support, killed or drove the last Japanese from the tunnels, bunkers, and pillboxes of Kokengolo Hill. Here were found caves stocked with rice, bales of clothing and blankets, and occupation currency. Crossing the western part of the runway, with its craters, grass, and wrecked Japanese planes, the infantrymen secured it in early afternoon. General Wing telephoned General Hodge from Bibilo Hill: “Munda is yours at 1410 today.”39 Griswold radioed the good news to Admiral Halsey: “... Our ground forces today wrested Munda from the Japs and present it to you ... as the sole owner. ...” Halsey responded with “a custody receipt for Munda. ... Keep ‘em dying.”40

The major objective was in Allied hands. The hardest part of the long New Georgia battle was over.