Chapter 10: After Munda

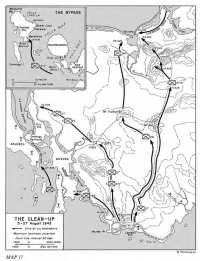

The hardest slugging was over, at least on New Georgia. But several tasks faced the troops. The airfield had to be put into shape at once and the remaining Japanese had to be cleaned out of New Georgia and several of the offshore islands. (Map 11)

The Airfield

Repair and enlargement of the battered airstrip began immediately after its capture.1 “... Munda airfield looked like a slash of white coral in a Doré drawing of hell. It lay like a dead thing, between the torn, coffee-colored hills of Bibilo and Kokengolo.”2 Seabees of the 73rd and 24th Naval Construction Battalions began the work of widening, resurfacing, and regrading the field. On 9 August additional naval construction battalions added their tools and men to the task. Power shovels dug coral out of Kokengolo Hill, and bulldozers, earthmovers, graders, and rollers spread and flattened it. Good coral was plentiful, as were men and tools, and the work moved rapidly forward. By 7 August the field, although rough, was suitable for emergency wheels-up landings.

Advance parties from General Mulcahy’s air headquarters moved from Rendova to Munda during the second week of August. On the 14th, the day after the first Allied plane landed, General Mulcahy flew from Rendova to Munda in his amphibian plane and opened Headquarters, Air Command, New Georgia, in a Japanese-dug tunnel in Kokengolo Hill.

Two Marine fighter squadrons (VMF 123 and VMF 124), with twelve Corsairs (F4U’s) each, arrived on the 14th and began operations at once. Together with the fighters based at Segi Point,

Map 11: The Cleanup, 5-27 August 1943

which were also under Mulcahy, they and other Allied squadrons covered the Allied landing at Vella Lavella on 15 August.3 There were some difficulties at first. Maintenance crews were inexperienced, there were not enough spare parts, the field was not complete, and taxiways and dispersal areas were small and in poor condition. Japanese naval guns, promptly nicknamed “Pistol Pete,” shelled the airfield from the nearby islet of Baanga intermittently from 16 through 19 August. But conditions quickly improved, and Pistol Pete, which had not done much damage, was captured by elements of the 43rd Division on 19 August.

As the field was enlarged, more planes and units continued to arrive. Operations intensified, and as the Japanese were cleared from the central Solomons Mulcahy’s planes began to strike targets in the northern Solomons. For this reason his command was removed from the New Georgia Occupation Force on 23 September and assigned as part of the Air Command, Solomons. Mulcahy’s fighters escorted bombers to the Bougainville bases, and Munda-based bombers soon began dropping loads there too.

Munda airfield, which by mid-October had a 6,000-foot coral-covered runway and thus was suitable for bombers, became the best and most-used airfield in the Solomons. The rotation of Navy, Marine Corps, and Army Air Forces commanders that was standard in the South Pacific had brought about the relief of Admiral Mitscher as Commander, Aircraft, Solomons, by General Twining, the Thirteenth Air Force commander. General Twining moved his headquarters on 20 October from Guadalcanal to Munda and made the most intensive possible use of the new base.

Reinforcements

Airfield development, though of primary importance, could be of only minor interest to the ground troops who had the dreary task of slogging northward from Bibilo Hill in an attempt to trap the retreating Japanese. The job had been assigned to the 27th and 161st Infantry Regiments, both operating under their parent command, the 25th Division.

Addition of the 27th Infantry to the New Georgia Occupation Force had come about because of General Griswold’s urgent requests for more men. During July the Western Force of Task Force 31 had carried fully 26,748 men to Rendova,4 but by the month’s end not that many men were available for combat. Many of the arrivals were service troops. Further, casualties and disease had weakened the infantry regiments. The three infantry regiments in the 37th Division (less the two battalions with Liversedge) had an authorized total strength of about 7,000 men. But the 161st Infantry, which entered the campaign below strength, was short 1,350 men. The two-battalion regiments were short too, so that the 37th Division’s rifle regiments had only 5,200 men. And the 43rd Division was in worse shape. With an authorized strength of 8,000 men, its three rifle regiments had but

Munda airfield in operation. C-47 transport taking off is evacuating wounded men

4,536 men. Griswold had asked Liversedge if he could release two infantry battalions for the Munda drive but Liversedge replied that would be possible only if Enogai and Rice Anchorage were abandoned. His raider battalions were then only 60 percent effective.5

On 28 July Griswold asked Harmon for replacements or for a regimental combat team less artillery. This request posed a grave problem for Harmon and Admiral Halsey. The injunction against committing major forces to New Georgia was still in effect; at least it was theoretically in effect, for in small island warfare, especially in 1943, 26,000 men constituted a major force. The only immediately available division was the 25th, and one of its regiments, the 161st, had been sent in fairly early. Further, Halsey and Harmon had planned to use the 25th for the invasion of the Buin–Faisi area of Bougainville.

Yet as long as the high command retained confidence in Griswold, there could be but one answer. As Harmon wrote to his chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Allison J. Barnett, “... we have to make this Munda–Bairoko business go—and as quickly as possible. It is the job ‘in hand’ and whatever we use we have to get it done before we go on to the next step.” One of the major difficulties,

according to Harmon, was the fact that the Americans had underestimated the job in hand. “Munda is a tough nut—much tougher in terrain, organization of the ground and determination of the Jap than we had thought. ... In both Guadalcanal and New Georgia we greatly underestimated the force require to do the job.”6 Thus Harmon alerted the 27th Infantry of the 25th Division for transfer to New Georgia and recommended to Halsey that the 25th Division be taken off the list for Bougainville.7 As soon as he received Halsey’s approval Harmon ordered up the 27th Infantry. On 29 July Col. Thomas D. Roberts of Harmon’s staff arrived at Griswold’s headquarters to announce the imminent arrival of the 27th Infantry and some replacements.

At this time the Japanese were still holding the Ilangana–Shimizu Hill–Horseshoe Hill–Bartley Ridge defense line, and no one was anticipating the rapid advances that characterized the first days of August. Thus on 30 July with Colonel Roberts’ concurrence Griswold asked for more 25th Division troops and Harmon promptly promised the 35th Infantry.

Advance elements of the 27th Infantry, and Headquarters, 25th Division, landed on the barrier island of Sasavele on 1 August, and in the next few days the regiment was moved to the right (north) flank of the Munda front to protect the XIV Corps’ right flank and rear.

The Cleanup

North to Bairoko

The Japanese withdrawal from Munda released a sizable body of American troops to attempt the cleanup of the Japanese between Munda and Dragons Peninsula. After the rapid advances began on 1 August the 27th Infantry, temporarily commanded by Lt. Col. George E. Bush, sent out patrols to the north before advancing to clear out the Japanese and make contact with Liversedge.8

Meanwhile General Griswold decided that mopping-up operations would have to include a drive from Bibilo Hill northwest to Zieta, a village on the west coast about four crow’s-flight miles northwest of Bibilo, to cut off the retreating Japanese. On 2 August the 37th Division had reported that Fijian patrols had cut the Munda–Bairoko trail but found no evidence of any Japanese traffic. Lt. Col. Demas L. Sears, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, 37th Division, offered the opinion that if the Japanese were evacuating New Georgia they were moving along the coast to Zieta rather than to Bairoko. This opinion was buttressed by reports from Colonel Griffith of the Raiders who radioed on 2 August that there had been no traffic in or out of Bairoko.

Next day, on orders from Griswold, the 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry, left Enogai on a cross-country trek toward Zieta, a trek that was halted short of there on 5 August by additional orders

4-ton truck stuck in the mud on a jeep trail, New Georgia

from Griswold. He had decided to use the two 25th Division regiments under General Collins, the commander who had led the division on Guadalcanal, to drive to Zieta and Bairoko.

From then until 25 August, the 25th Division units slogged painfully along the swampy jungle trails in pursuit of the elusive enemy. The Japanese occasionally established roadblocks, ambushes, and defenses in depth to delay the Americans, but the worst enemy was the jungle. The terrain was, if anything, worse than that encountered on the Munda front. The maps were incorrect, inexact, or both. For example, Mount Tirokiamba, a 1,500-foot eminence reported to lie about 9,000 yards northwest of Bibilo Hill, was found to be 4,500 yards south by west of its reported position. Mount Bao, thought to be 6,000 yards east-northeast of Bibilo Hill, was actually 2,500 yards farther on.

As the regiments advanced, bulldozers of the 65th Engineer Battalion attempted to build jeep trails behind them. But the rain fell regularly and the trails became morasses so deep that even the bulldozers foundered. General Collins ordered the trail building stopped in mid-August. Now supplies were carried by hand and on men’s backs to the front, and when these methods failed to provide enough food and ammunition the regiments were supplied from the air.

37th division troops carrying weapons and ammunition forward, 5 August 1943

The 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, trekked north on the Munda–Bairoko trail and made contact on 9 August with Liversedge. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 27th Infantry, after some sharp fighting took Zieta on 15 August, then pushed northwest to Piru Plantation. The plantation lay about seven and one-half airline miles northwest of Bibilo Hill, but the regiment’s advance on the ground required a 22-mile march. The 161st Infantry, following the 1st Battalion, 27th, moved up the trail and after mid-August began patrolling to the west short of Bairoko Harbour. On 25 August, after Griffith had reported two nights of busy enemy barge activity in and out of Bairoko Harbour, the Americans bloodlessly occupied its shores.

The Japanese Evacuation

But the main body of Japanese survivors had slipped out of Zieta and Bairoko. Traveling light, they had evaded the slower-moving, more heavily encumbered Americans. On 5 August General Sasaki had decided that he could defend New Georgia no longer. He therefore sent the 13th Infantry and most of the Bairoko-based special naval landing force units to Kolombangara, the 229th Infantry, the 3rd Battalion, 230th Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Infantry, to Baanga, a long narrow island

which lay across Lulu Channel from Zieta. These units, plus two 120-mm. naval guns, were ordered to defend Baanga, and the naval guns were to shell Munda airfield.

Sasaki’s headquarters, having moved out of Munda, was established on Baanga until 7 August, and the next day he moved to Kolombangara.

Baanga

The islet of Baanga, 6,500 yards long and some 4,000 yards west of Kindu Point on New Georgia, was captured to extend Allied control over Diamond Narrows and to stop the shelling of Munda by the two 120-mm. guns nicknamed “Pistol Pete” by the American troops.

Seizure of Baanga was entrusted to the 43rd Division, briefly commanded by General Barker after 10 August, when General Hodge returned to the Americal Division.9 Patrolling started on 11 August, but the Japanese on Baanga fought back hard, and the 169th Infantry, which Barker initially assigned to Baanga, gave a “shaky performance.”10 The 172nd Infantry (less one battalion) joined in, and the southern part of the island was secured by 21 August. The 43rd Division lost 52 men killed, 110 wounded, and 486 nonbattle casualties in this operation.

The Japanese, meanwhile, had decided to get off Baanga. General Sasaki had evolved a plan to use the 13th Infantry, then on Kolombangara, to attack New Georgia, and dispatched his naval liaison officer to 8th Fleet headquarters to arrange for air and fleet support. But he was to get none. Moreover, no more ground reinforcements were to be sent to New Georgia. The last attempted shipment consisted of two mixed battalions from the 6th and 38th Divisions, to be carried to Kolombangara on destroyers.11 But Comdr. Frederick Moosbrugger with six destroyers surprised the Japanese force in Vella Gulf on the night of 6-7 August and quickly sank three Japanese destroyers. The fourth enemy ship, which carried no troops, escaped. Moosbrugger’s force got off virtually scot free, while the Japanese lost over fifteen hundred soldiers and sailors as well as the ships. About three hundred survivors reached Vella Lavella.12 When Sasaki’s request reached the 8th Fleet, Vice Adm. Gunichi Mikawa, basing his decision on instructions from Imperial General Headquarters, ordered Sasaki to cancel his plan for attacking New Georgia and to concentrate the Baanga troops on Arundel to forestall further Allied advances. So the Japanese left on barges for Arundel, completing the movement by 22 August.

Vella Lavella: The Bypass

Meanwhile an Allied force had made a landing at Barakoma on Vella Lavella, which lay about thirty-five nautical miles northwest of Munda. This landing represented a major and completely successful departure from the original TOENAILS plan. The plan had called for the attack against Munda to be followed by

the seizure of Vila airfield on Kolombangara, but the Japanese were now correctly believed to be established on Kolombangara in considerable strength. Some estimates placed the enemy garrison at ten thousand, a little under the actual total. And Admiral Halsey did not want a repetition of the Munda campaign. As he later put it, “The undue length of the Munda operation and our heavy casualties made me wary of another slugging match, but I didn’t know how to avoid it.”13

There was a way to avoid a slugging match, and that way was to bypass Kolombangara completely and land instead on Vella Lavella. The advantages were obvious: the airfield at Vila was poorly drained and thus no good while Vella Lavella looked more promising. Also, Vella Lavella was correctly reported to contain few Japanese. Vella Lavella, north-westernmost island in the New Georgia group, lay less than a hundred miles from the Japanese bases in the Shortlands and southern Bougainville, but a landing there could be protected by American fighter planes based at Munda and Segi Point.

The technique of bypassing, which General MacArthur has characterized as “as old as warfare itself,” was well understood in the U.S. Army and Navy long before Vella Lavella, but successful bypassing requires a preponderance of strength that Allied forces had not hitherto possessed.14 The first instance of an amphibious bypass in the Pacific occurred in May 1943 when the Allied capture of Attu caused the Japanese to evacuate Kiska.

When members of Halsey’s staff proposed that South Pacific forces bypass Kolombangara and jump to Vella Lavella of the more euphonious name, the admiral was enthusiastic.15 On 11 July he radioed the proposal to Admirals Turner and Fitch. “Our natural route of approach from Munda to Bougainville,” he asserted, “lies south of Gizo and Vella Lavella Islands.” He asked them to consider whether it would be practicable to emplace artillery in the Munda–Enogai and Arundel areas to interdict Vila; cut the supply lines to Vila by artillery and surface craft, particularly PT boats; “by-pass Vila area and allow it to die on the vine”; and seize Vella Lavella and build a fighter field there. The decision on this plan would depend on the possibility of building a fighter field on Vella Lavella to give close fighter support for the invasion of Bougainville.16 Both Turner and Fitch liked the idea.

Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance was necessary first.

Allied knowledge of Vella Lavella was limited. Coastwatchers, plantation managers, and such members of the clergy as the Rev. A. W. E. Silvester, the New Zealand Methodist missionary bishop whose see included New Georgia and Vella Lavella, provided some information but not enough to form the basis for the selection of an airfield site or an invasion beach. Col. Frank L. Beadle, Harmon’s engineer, therefore took command of a reconnaissance party consisting of six Army, Navy, and Marine officers. Beadle was ordered to concentrate his reconnaissance in the coastal plain region of Barakoma and Biloa Mission on the southeast tip of Vella Lavella because it was closest to Munda, the natives were friendly, coastwatcher Lt. Henry Josselyn of the Australian Navy and Bishop Silvester were there, and the terrain seemed favorable. The Japanese had already surveyed the Barakoma area for a fighter strip.

Beadle’s party boarded a torpedo boat at Rendova on the night of 21-22 July and slipped through the darkness to land at Barakoma. Silvester, Josselyn, and two natives were on hand to meet the American officers. For six days Beadle’s party, the bishop, the coastwatcher, and several natives explored the southeast part of the island, and ventured up the west coast to Nyanga Plantation, about twelve crow’s-flight miles northwest of Barakoma. Returning to Rendova on 28 July, Beadle reported that the vicinity of Barakoma met all requirements, and that there were no Japanese on the southeast coast of the island. Beadle recommended that the landing be made on beaches extending some 750 yards south from the mouth of the Barakoma River, and suggested that an advance detachment be sent to Barakoma to mark beaches. These recommendations were accepted.

Admiral Wilkinson, Turner’s successor, chose an advance party of fourteen officers and enlisted men from the various units in the Vella Lavella invasion force and placed it under Capt. G. C. Kriner, USN, who was to command the Vella Lavella naval base. This group proceeded from Guadalcanal to Rendova, then prepared to change to PT boats for the run through the night of 12-13 August toward Barakoma. The work of the advance party was of a highly secret nature. If the Japanese became aware of its presence, they could kill or capture the men and certainly would deduce that an Allied invasion was imminent.

On 11 August coastwatcher Josselyn radioed Guadalcanal to report the presence of forty Japanese. (Japanese survivors of the Battle of Vella Gulf, 6-7 August, had landed on Vella Lavella.) His message indicated that pro-Allied natives had taken them prisoner. From Koli Point General Harmon radioed General Griswold to ask for more men to accompany the advance party and take the prisoners into custody. Accordingly one officer and twenty-five enlisted men from E and G Companies, 103rd Infantry, were detailed to go along.

The whole party left Rendova at 1730 on 12 August. En route Japanese planes bombed and strafed the four torpedo boats for two hours. One was hit and four men were wounded but the other three made it safely. During the hours of darkness they hove to off Barakoma. Rubber boats had been provided to get

the party from the torpedo boats to shore, but no one was able to inflate the rubber boats from the carbon dioxide containers that were provided. So natives paddled out in canoes and took the Americans ashore.

Meanwhile Josselyn had radioed Wilkinson again to the effect that there were 140 Japanese in the area; 40 at Biloa and 100 about five miles north of Barakoma. They were, he declared, under surveillance but were not prisoners. Once ashore Captain Kriner discovered there were many starving, ragged, poorly armed stragglers but no prisoners. He requested reinforcements, and in the early morning hours of 14 August seventy-two officers and enlisted men of F Company, 103rd Infantry, sailed for Barakoma in four torpedo boats. This time the rubber boats inflated properly and the men paddled ashore from three hundred yards off the beach.

The advance party with the secret mission of marking beaches and the combat party with the prisoner-catching mission set about their respective jobs. Beach marking proceeded in a satisfactory manner although the infantrymen in that party were not completely happy about the presence of the 103rd troops. They felt that the two missions were mutually exclusive and that the prisoner-catching mission destroyed all hope of secrecy. Only seven Japanese were captured.17 F Company, 103rd, held the beachhead at Barakoma against the arrival of the main invasion force.

Plans

Once Colonel Beadle had made his recommendations the various South Pacific headquarters began laying their plans. This task was fairly simple, for Admiral Halsey and his subordinates were now old hands at planning invasions. Actual launching of the invasion would have to await the capture and development of Munda airfield.

It was on 11 August that Halsey issued his orders. He organized his forces much as he had for the invasion of New Georgia. (Chart 10) The Northern Force (Task Force 31) under Admiral Wilkinson was to capture Vella Lavella, build an airfield, and establish a small naval base. Griswold’s New Georgia Occupation Force would meanwhile move into position on Arundel and shell Vila airfield on bypassed Kolombangara. New Georgia-based planes would cover and support the invasion. South Pacific Aircraft (Task Force 33) was to provide air support by striking at the Shortlands–Bougainville fields. As strikes against these areas were being carried out regularly, the intensified air operations would not necessarily alert the enemy. Three naval task forces of aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, and destroyers, and the submarines of Task Force 72, would be in position to protect and support Wilkinson. On Wilkinson’s recommendation, Halsey set 15 August as D Day.18

Admiral Wilkinson also issued his orders on 11 August. The Northern Force was organized into three invasion echelons (the main body and the second

Chart 10: South Pacific Organization for Vella Lavella Invasion

and third echelons) and the motor torpedo boat flotillas. (Chart 11) Under Wilkinson’s direct command, the main body consisted of three transport groups, the destroyer screen, and the northern landing force. Each transport group, screened by destroyers, was to move independently from Guadalcanal to Vella Lavella; departure from Guadalcanal would be so timed that each group would arrive off Barakoma just before it was scheduled to begin unloading. Three slow LSTs, each towing an LCM, would leave at 0300, 14 August, six LCIs at 0800, and seven fast APDs at 1600. The motor torpedo boat flotilla would cover the movement of the main body on D minus 1 by patrolling the waters east and west of Rendova, but would retire to Rendova early on D Day to be out of the way. Preliminary naval bombardment would in all probability not be necessary, but Wilkinson told off two destroyers to be prepared to support the landing if need be. Two fighter-director groups were put aboard two destroyers. Once unloaded, each transport group would steam for Guadalcanal. The second echelon, composed of three LSTs and three of the destroyers that would escort the main body, was to arrive at Barakoma on D plus 2, beach overnight, and return to Guadalcanal. The third echelon consisted of three destroyers and three LSTs from the main body. Wilkinson ordered it to arrive on D plus 5, beach throughout the night, and depart for Guadalcanal the next morning.19

The northern landing force, 5,888 men in all, consisted of the 35th Regimental Combat Team of the 25th Division;

Chart 11: Organization of Northern Force [TF 31], Vella Lavella

the 4th Marine Defense Battalion; the 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop; the 58th Naval Construction Battalion; and a naval base group.20 Command of the landing force was entrusted to Brig. Gen. Robert B. McClure, assistant commander of the 25th Division, who as a colonel had commanded the 35th Infantry during the Guadalcanal Campaign. General McClure would be under Wilkinson’s control until he was well established ashore. He would then come under General Griswold.

The Japanese on Vella Lavella (no garrison at all but only a group of stragglers) were estimated to total about 250, with 100 more on nearby Ganongga and 250 at Gizo. Wilkinson warned that enemy air strength in southern Bougainville, less than a hundred miles away, and at Rabaul was considerable, and that naval surface forces were based at both places.

To carry off such a stroke almost literally under the enemy’s aircraft would require, besides fighter cover, considerable speed in unloading. Wilkinson planned to unload the main body in twelve hours. Troops debarking from APDs were to go ashore in LCVPs, forty to a boat. At the beach ten of each forty would unload the boat while the thirty pushed inland. Once emptied, LCVPs were to return to their mother ships for the rest of the men and supplies. Sixty minutes were allotted for unloading the APDs and clearing the beach. The LCIs would then come in to the beach and drop their ramps. Passenger troops would debark via both ramps, ground their equipment, then reboard by the starboard ramps, pick up gear, and go ashore down the port ramps. One hour was allotted for the LCIs. Then the LSTs, bearing artillery, trucks, and bulldozers, would ground. Trucks were to be loaded in advance to help insure the prompt unloading of the LSTs.

The 35th Infantry, commanded by Col. Everett E. Brown, had been making ready for several days. It had been alerted for movement to Munda on 1 August, and on 9 August had received orders from Harmon’s headquarters to prepare for an invasion. The 1st and 2nd Battalions on Guadalcanal and the 3rd Battalion and the 64th Field Artillery Battalion in the Russells then began rehearsing landings. In the week preceding the invasion South Pacific Aircraft struck regularly at Kolombangara, Buin, Kahili, and Rekata Bay.

By 14 August the landing force and its supplies were stowed aboard ship, and all transport groups of the main body shoved off for Barakoma on schedule. Once on board, the men were informed of their destination. Japanese planes were reported over Guadalcanal, the Russells, and New Georgia, but Wilkinson’s ships had an uneventful voyage up the Slot and through Blanche Channel and Gizo Strait. The sea was calm, and a bright moon shone in the

clear night sky. Northwest of Rendova the LCIs overhauled the LSTs while the APDs passed both slower groups.

Seizure of Barakoma

As first light gave way to daylight in the morning of 15 August, the APDs carrying the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 35th Infantry arrived off Barakoma and hove to. General Mulcahy’s combat air patrol from Munda and Segi Point turned up on schedule at 0605. With part of the 103rd Infantry and the secret advance party already on shore and in possession of the landing beach, there was no need for support bombardment. The APDs swung landing craft into the water, troops of the 2nd Battalion climbed down the cargo nets and into the boats, and the first wave, with rifle companies abreast, departed. The 2nd Battalion hit the beach at 0624 and at once pushed south toward the coconut plantation around Biloa Mission, about four thousand yards from the beach. The 1st Battalion, having left the APDs at 0615, landed with companies abreast at 0630 and pushed northward across the waist-deep Barakoma River. Thus quickly unloaded, the APDs cleared the area and with four escorting destroyers proceeded toward Guadalcanal.

The twelve LCIs arrived on schedule and sailed in to the beach, but quickly found there was room for but eight at one time. Coral reefs a few yards from shore rendered the northern portion of the beach unusable. The remaining four LCIs had to stand by offshore awaiting their turn. The 3rd Battalion started unloading but had barely gotten started when enemy aircraft pounced at the invasion force.

This time the Japanese were not caught so completely asleep as they had been on 30 June. In early August Japanese radio intelligence reported a good deal of Allied radio traffic, and the commanders at Rabaul were aware that ships were again concentrating around Guadalcanal. They concluded that a new invasion was impending but failed to guess the target. At 0300 of the 15th a land-based bomber spotted part of Wilkinson’s force off Gatukai. Six dive bombers and forty-eight fighters were sent out on armed reconnaissance, and these found the Americans shortly before 0800. Mulcahy’s planes and ships’ antiaircraft guns promptly engaged them. The Japanese planes that broke through went for the destroyers, which steamed on evasive courses and escaped harm. The Japanese caused some casualties ashore by strafing, but did not attack the LSTs and LCIs. They ebulliently reported repulsing fifty Allied planes.

This attack, together with the limitations of the beach, delayed the unloading of the LCIs, which did not pull out until 0915.21 The three LSTs then beached and began discharging men and heavy cargo. Unloading continued all day.

The Japanese struck again at 1227; eleven bombers and forty-eight fighters came down from the north. Some attacked the LSTs but these “Large, Slow Targets” had mounted extra antiaircraft guns and brought down several Japanese planes.

At 1724, some thirty-six minutes before the LSTs departed, the enemy came again. Forty-five fighters and eight bombers

attacked without success. The Japanese pilots who flew against the Northern Force on that August day showed a talent for making unwarranted claims. A postwar account soberly admits the loss of seventeen planes, but claims the sinking of four large transports, one cruiser, and one destroyer. It states that twenty-nine Allied planes were shot down and that four large transports were damaged.22 The ships retiring from Vella Lavella were harried from the air almost all the way, fortunately without suffering damage.

D Day, a resounding success, had proceeded with the efficiency that characterized all Admiral Wilkinson’s operations. Landed were 4,600 troops (700 of whom were naval personnel) and 2,300 tons of gear including eight 90-mm. antiaircraft guns, fifteen days’ supplies, and three units of fire for all weapons except antiaircraft guns, for which one unit was landed. The 35th Regimental Combat Team established a perimeter defense. Field artillery was in position by 1700, and by 1530 the 4th Marine Defense Battalion had sixteen .50-caliber, eight 20-mm., and eight 40-mm. antiaircraft guns and two searchlights in place. The guns engaged the last flight of enemy planes. There were some problems, of course. The LSTs had been unloaded slowly, but supplies came ashore faster than the shore party could clear them off the beach. Boxes of equipment, ammunition, and rations were scattered about. The troops had brought their barracks bags and these lay rain-soaked in the mud. Unused field stoves stood in the way for several days.

The bypass to Vella Lavella was easier and cheaper than an assault on Kolombangara. Twelve men were killed and forty wounded by air bombing and strafing, but D Day saw no fighting on the ground.

There was never any real ground combat on Vella Lavella, because Japanese stragglers were mainly interested in escape rather than fighting. When it became known that Wilkinson was landing on Vella Lavella officers of the 8th Fleet and the 17th Army went into conference. They estimated, with an accuracy unusual for Japanese Intelligence, that the landing force was about a brigade in strength. With blithe sanguinity someone proposed sending a battalion to effect a counterlanding. General Imamura’s headquarters took a calmer view and pointed out that sending one battalion against a brigade would be “pouring water on a hot stone.”23 The 8th Area Army stated that two brigades would be needed to achieve success, but that not enough transports were available. In view of the general Japanese strategy of slow retreat in the central Solomons in order to build up the defenses of Bougainville and hold Rabaul, it was decided to send two rifle companies and one naval platoon to Horaniu at Kokolope Bay on the northeast corner of Vella Lavella to establish a barge staging base between the Shortlands and Kolombangara.

The real struggle for Vella Lavella took place in the air and on the sea. Japanese naval aircraft made a resolute effort to destroy the American ships bearing supplies and equipment to Vella.

Fighters and bombers delivered daylight attacks and seaplanes delivered a series of nocturnal harassing attacks that were all too familiar to Allied troops who served in the Solomons in 1942, 1943, and early 1944.

The combat air patrol from Mulcahy’s command made valiant efforts to keep the Japanese away during daylight, but as radar-equipped night-fighters did not reach the New Georgia area until late September shore- and ship-based antiaircraft provided the defense at night.24 For daylight cover Mulcahy had planned to maintain a 32-plane umbrella over Barakoma, but the limited operational facilities at Munda made this impossible at first. On 17 August only eight fighters could be sent up at once to guard Barakoma. To add to the difficulties, the weather over New Georgia was bad for a week, the fighter-director teams on Vella Lavella were new to their task, and one of the 4th Defense Battalion’s radars was hit by a bomb on 17 August.

The Northern Force’s second echelon, under Capt. William R. Cooke, having departed Guadalcanal on 16 August, beached at Barakoma at 1626 the next day. The fighter cover soon left for Munda and at 1850, and again at 1910, Japanese planes came over to bomb and strafe. General McClure ordered Cooke not to stay beached overnight but to put to sea. Escorted by three destroyers, the LSTs went down Gizo Strait where they received an air attack of two hours and seventeen minutes’ duration. The convoy sailed toward Rendova until 0143, then reversed and headed for Barakoma. One LST caught fire, probably as a result of a gasoline vapor explosion, and was abandoned without loss of life. The other two reached Barakoma, suffered another air attack, unloaded, and returned safely to Guadalcanal.

Capt. Grayson B. Carter led the third echelon to Vella Lavella. It was attacked by enemy planes in Gizo Strait at 0540 on 21 August; one destroyer was slightly damaged and two men were killed. Planes struck off and on all day at the beached LSTs, but men of the 58th Naval Construction Battalion showed such zeal in unloading that the LSTs were emptied by 1600. The next convoys, on 26 and 31 August, had less exciting trips. The weather had cleared and the air cover was more effective. During the first month they were there, the Americans on Vella Lavella received 108 enemy air attacks, but none caused much damage. In the period between 15 August and 3 September, the day on which Wilkinson relinquished control of the forces ashore, Task Force 31 carried 6,505 men and 8,626 tons of supplies and vehicles to Vella Lavella.

During that period General McClure’s troops had strengthened the defenses of Barakoma, established outposts and radar stations, and patrolled northward on both coasts. On 28 August a thirty-man patrol from the 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop that had accompanied radar specialists of the 4th Marine Defense Battalion in search of a new radar site reported considerable enemy activity at Kokolope Bay.

Capture of Horaniu

Having decided to establish the barge base at Horaniu, the Japanese sent the

Warship firing at Japanese destroyers near the coast of Vella Lavella, early morning 18 August

two Army companies and the naval platoon, 390 men in all, out of Erventa on 17 August. Four torpedo boats, 13 troop-carrying daihatsu barges,25 2 armored barges, 2 submarine chasers, 1 armored boat, 4 destroyers, and 1 naval air group from the Shortlands were involved. The destroyers were intercepted north of Vella Lavella in the early morning hours of 18 August. The daihatsus dispersed. The Americans sank the 2 submarine chasers, 2 motor torpedo boats, and 1 barge. The Japanese destroyers, two of which received light damage, broke off the action and headed for Rabaul.26 Harried by Allied planes, the daihatsus hunted for and found Horaniu, and the troops were ashore by nightfall on 19 August. About the same time, General Sasaki took alarm at the seizure of Barakoma and sent the 2nd Battalion, 45th Infantry, and one battery of the 6th Field Artillery Regiment from Kolombangara to defend Gizo.

When General McClure received the

report from the reconnaissance troop patrol on 28 August, he ordered Maj. Delbert Munson’s 1st Battalion to advance up the east coast and take the shore of Kokolope Bay for a radar site. To take the 1st Battalion’s place in the perimeter defense, McClure asked Griswold for a battalion from New Georgia. The 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, was selected.

On the morning of 30 August Major Munson dispatched A Company up the east coast ahead of his battalion, and next day, after the arrival of the 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, the main body of the 1st Battalion, 35th, started north. Josselyn and Bishop Silvester had provided native guides and the bishop gave Munson a letter instructing the natives to help the American soldiers haul supplies. C Company, 65th Engineer Battalion, was to build a supply road behind Munson.

By afternoon of 1 September A Company had reached the vicinity of Orete Cove, about fourteen miles northeast of Barakoma. The main body of the battalion was at Narowai, a village about seven thousand yards southwest of Orete Cove. The coastal track, which had been fairly good at first, narrowed to a trail that required the battalion to march in single file. Inland were the jungled mountains of the interior. Supply by hand-carry was impossible, and McClure and Colonel Brown, who had been informed that higher headquarters expected the Japanese to evacuate, decided to use landing craft to take supplies to Munson. On 2 September supplies arrived at Orete Cove along with seventeen Fiji scouts under Tripp, who had recently been promoted to major.

From that day until 14 September Munson’s battalion, supported by the 3rd Battalion, 35th, and C Battery, 64th Field Artillery Battalion, moved forward in a series of patrol actions and skirmishes.

Horaniu fell on 14 September. The Japanese did not seriously contest the advance. Instead they withdrew steadily, then moved overland to the northwest corner of the island.

Up to now troops of the United States had borne the brunt of ground combat in the Solomons, but Admiral Halsey had decided to give the 3rd New Zealand Division a chance to show its mettle. He had earlier moved the division from New Caledonia to Guadalcanal. On 18 September Maj. Gen. H. E. Barrowclough, general officer commanding the division, took over command of Vella Lavella from General McClure. On the same day the 14th New Zealand Brigade Group under Brigadier Leslie Potter landed and began the task of pursuing the retreating enemy.27 Battalion combat teams advanced up the east and west coasts, moving by land and by water in an attempt to pocket the enemy. But the Japanese eluded them and got safely off the island.

The Seabees had gone to work on the airfield at once. As at Munda, good coral was abundant. By the end of August they had surveyed and cleared a strip four thousand feet long by two hundred feet wide. They then began work on a control tower, operations shack, and fuel tanks.

The first plane to use the field landed on 24 September, and within two months after the invasion the field could accommodate almost a hundred aircraft.

The decision to bypass Kolombangara yielded this airfield in return for a low casualty rate. Of the Americans in the northern landing force, 19 men were killed by bombs, 7 died from enemy gunfire, and 108 were wounded. Thirty-two New Zealanders died, and 32 were wounded.

Final Operations

Arundel

About the time that Vella Lavella was being secured, General Griswold’s forces on New Georgia were carrying out their part of Admiral Halsey’s plan by seizing Arundel and by shelling Kolombangara to seal it off. The attack on Arundel, which is separated from the west coast of New Georgia by Hathorn Sound and Diamond Narrows, proved again that it was all too easy to underestimate the Japanese capacity for resolute defense. The 172nd Infantry invaded it on 27 August, but the Japanese fought so fiercely that the 27th Infantry, two battalions of the 169th Infantry, one company of the 103rd Infantry, B Company of the 82nd Chemical Battalion (4.2-inch mortars, in their South Pacific debut), the 43rd Reconnaissance Troop, and six Marine tanks had to be committed to keep the offensive going.

Resistance proved more intense than expected in part because the indefatigable Sasaki had not yet abandoned his hope of launching an offensive that would recapture Munda. On 8 September he sent the 3rd Battalion, 13th Infantry, from Kolombangara to strengthen his forces on Arundel, and five days later, when Allied air and naval forces had practically cut the supply lines between Bougainville and Kolombangara and his troops faced starvation, he decided to attack Munda or Bairoko via Arundel and seize the Americans’ food. He therefore dispatched Colonel Tomonari (who was slain in the ensuing fight) and the rest of the 13th Infantry to Arundel on 14 September.

Thus the battle for Arundel lasted until 21 September, and ended then, with the Americans in control, only because Sasaki ordered all his Arundel troops to withdraw to Kolombangara.

The Japanese Evacuation

Sasaki had ordered the evacuation of Arundel because Imperial General Headquarters had decided to abandon the New Georgia Islands completely. While the Americans were seizing Munda airfield, the Japanese naval authorities in the Southeast Area realized that their hold on the central Solomons was tenuous. But they resolved to maintain the line of communications to Kolombangara, so that Sasaki’s troops could hold out as long as possible. If Sasaki could not hold out, the next best thing would be a slow, fighting withdrawal to buy time to build up defenses for a final stand on Bougainville.

Such events in early August as the fall of Munda and the Japanese defeat in Vella Gulf on 6-7 August precipitated another argument between Japanese Army and Navy officers over the relative strategic merits of New Guinea and the Solomons. This argument was resolved in Tokyo by the Imperial General Headquarters which decided to give equal

14th New Zealand brigade group landing on Vella Lavella, 18 September 1943

priority to both areas. Tokyo sent orders to Rabaul on 13 August directing that the central Solomons hold out while Bougainville was strengthened, and that the central Solomons were to be abandoned in late September and early October. The decision to abandon New Georgia was not made known at once to General Sasaki.

Sasaki, with about twelve thousand men concentrated on Kolombangara, prepared elaborate defenses along the southern beaches and, as shown above, prepared plans for counterattacks. Finally on 15 September, after Sasaki had sent the 13th Infantry to Arundel, an 8th Fleet staff officer passed the word to get his troops out.

Southeastern Fleet, 8th Fleet, and Sasaki’s headquarters prepared the plans for the evacuation. A total of 12,435 men were to be moved. Eighteen torpedo boats, thirty-eight large landing craft, and seventy or eighty Army barges (daihatsus) were to be used.28 Destroyers were to screen the movement, aircraft would cover it, and cruisers at Rabaul would stand by in support.

The decision to use the daihatsus was logical, considering the destroyer losses in Vella Gulf and the success the nocturnal daihatsus had enjoyed. American

PT boat squadrons, four in all, had been operating nightly against the enemy barges in New Georgian waters since late July, and had sunk several, but only a small percentage of the total. Destroyers and planes had also operated against them without complete success. The Japanese put heavier armor and weapons on their barges for defense against torpedo boats, which in turn replaced their torpedoes—useless against the shallow draft barges—with 37-mm. antitank and 40-mm. antiaircraft guns. The barges were too evasive to be suitable targets for the destroyers’ 5-inch guns. Planes of all types, even heavy bombers, hunted them at sea, but the barges hid out in the daytime in carefully selected staging points. Those traveling by day covered themselves with palm trees and foliage so that from the air they resembled islets.

Sasaki ordered his troops off Gizo and Arundel; those on Arundel completed movement to Kolombangara by 21 September. The seaplane base at Rekata Bay on Santa Isabel and the outpost on Ganongga Island were also abandoned at this time. The evacuation of Kolombangara was carried out on the nights of 28-29 September, 1-2 October, and 2-3 October. Admiral Wilkinson had anticipated that the enemy might try to escape during this period, the dark of the moon. Starting 22 September American cruisers and destroyers made nightly reconnaissance of the Slot north of Vella Lavella, but when Japanese submarines became active the cruisers were withdrawn. The destroyers attempted to break up the evacuation but failed because enemy planes and destroyers interfered. The Japanese managed to get some 9,400 men, or some 3,600 less than they had evacuated from Guadalcanal in February, safely off the island. Most of them were sent to southern Bougainville. Twenty-nine landing craft and torpedo boats were sunk, one destroyer was damaged, and sixty-six men were killed.29

The final action in the New Georgia area was the Battle of Vella Lavella on the night of 6-7 October, when ten Japanese destroyers and twelve destroyer-transports and smaller craft came down to Vella Lavella to rescue the six hundred stranded men there. Facing odds of three to one, American destroyers engaged the Japanese warships northwest of Vella Lavella. One Japanese destroyer was sunk; one American destroyer was badly damaged and sank, and two more suffered damage. During the engagement the transports slipped in to Marquana Bay on northwest Vella Lavella and got the troops out safely.30 The last organized bodies of Japanese had left the New Georgia area.

When the 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry, landed at Ringi Cove on southern Kolombangara on the morning of 6 October, it found only forty-nine abandoned artillery pieces and some scattered Japanese who had been left behind.31 The long campaign—more than four months had elapsed since the Marines landed at Segi Point—was over.

Table 2: American casualties on New Georgia

| 25th Division | 37th Division | 43rd Division | Others | Total | |

| Killed in action and died of wounds | 141 | 220 | 538 | 196 | 1,094 |

| Wounded | 550 | 887 | 1,942 | 494 | 3,873 |

| Missing | 1 | 5 | 17 | 23 | |

| Accidental death | 2 | 2 | 4 |

Source: NGOF, Narrative Account of the Campaigns in the New Georgia Group, p. 29.

Conclusion

New Georgia had been lengthy and costly. Planned as a one-division affair, it had used up elements of four divisions. It would be months before the 25th and 43rd Divisions were ready to fight again. American casualties totaled 1,094 dead, 3,873 wounded. (Table 2) These figures do not tell the complete story, for they count only men killed or wounded by enemy fire. They do not include casualties resulting from disease or from combat fatigue or war neuroses. For example the 172nd Infantry reported 1,550 men wounded or sick; the 169th Infantry, up to 5 August, suffered 958 nonbattle casualties. The 103rd Infantry had 364 “shelled-shocked” and 83 nonbattle casualties.32

Japanese casualties are not known, but XIV Corps headquarters reported a count of enemy dead, exclusive of Vella Lavella, of 2,483.

The Allied soldiers, airmen, marines, and sailors who suffered death, wounds, or illness, and those who fought in the campaign without injury, had served their cause well. New Georgia was a success. The bypassing of Kolombangara, though overshadowed by later bypasses and clouded by the fact that the bypassed troops escaped, was a satisfactory demonstration of the technique; the seizure of Vella Lavella provided Halsey’s forces with a good airfield for a much lower price in blood than an assault on Kolombangara. The Allies swiftly built another airfield at Ondonga Peninsula on New Georgia. This gave them four—Munda, Barakoma, Ondonga, and Segi. The first three, the most used, brought all Bougainville within range of Allied fighters. When South Pacific forces invaded the island, they could pick an undefended place and frustrate the Japanese efforts to build up Bougainville’s defenses and delay the Allies in New Georgia.

The New Georgia operation is also significant as a truly joint operation, and it clearly illustrates the interdependence of air, sea, and ground forces in oceanic warfare. Victory was made possible only by the close coordination of air, sea, and ground operations. Air and sea forces fought hard and finally successfully to cut the enemy lines of communication while the ground troops clawed their way forward to seize objectives intended for use by the air and sea forces in the next advance. Unity of command, established

Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins talking to Maj. Charles W. Davis, Commanding Officer, 3rd Battalion, 27th Infantry (left), New Georgia, August 1943

from the very start, was continued throughout with obvious wholeheartedness by all responsible commanders.

No account of the operation should be brought to a close without praising the skill, tenacity, and valor of the heavily outnumbered Japanese who stood off nearly four Allied divisions in the course of the action, and then successfully evacuated 9,400 men to fight again. The obstinate General Sasaki, who disappears from these pages at this point, deserved his country’s gratitude for his gallant and able conduct of the defense.

![Chart 11: Organization of

Northern Force [TF 31], Vella Lavella](thu/img177.jpg)