Chapter 12: The Invasion of Bougainville

While MacArthur’s and Halsey’s troops were gaining the Trobriands, the Markham Valley, the Huon Peninsula, and the New Georgia group for the Allied cause, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and their subordinate committees in Washington had been making a series of decisions affecting the course of the war in the Pacific. These decisions related not so much to CARTWHEEL itself as to General MacArthur’s desire to make the main effort in the Pacific along the north coast of New Guinea into the Philippines. But, since they called for troops to support the offensives in Admiral Nimitz’ Central Pacific Area, they had an immediate impact upon CARTWHEEL, especially on the Bougainville invasion (Operation B of ELKTON III) and on MacArthur’s plans to seize Rabaul and Kavieng after CARTWHEEL.

The Decision To Bypass Rabaul

Once the Combined Chiefs at Casablanca had approved an advance through the Central Pacific, the Joint Chiefs put their subordinates to work preparing a general strategic plan for the defeat of Japan. An outline plan was submitted at the meeting of the Combined Chiefs in Washington, 12-15 May 1943. The Combined Chiefs approved the plan as a basis for further study.1

The plan, which governed in a general way the operations of Nimitz’ and MacArthur’s forces until the end of the war, aimed at securing the unconditional surrender of Japan by air and naval blockade of the Japanese homeland, by air bombardment, and, if necessary, by invasion. The American leaders agreed that naval control of the western Pacific might bring about surrender without invasion, and even without air bombardment. But if air bombardment, invasion, or both proved necessary, air and naval bases in the western Pacific would be required. Therefore, the United States forces were to fight their way westward across the Pacific along two axes of advance: a main effort through the Central Pacific and a subsidiary effort through the South and Southwest Pacific Areas.2 (See Map 1.)

The Washington commanders and

planners preferred the Central Pacific route for the main effort because it was shorter and more healthful than the South-Southwest Pacific route; it would require fewer ships, troops, and supplies; success would cut off Japan from her overseas empire; destruction of the Japanese fleet, which would probably come out fighting to oppose the advance, would enable naval forces to strike directly at Japan; and it would outflank and cut off the Japanese in the Southeast Area. The main effort should not be made through the South and Southwest Pacific Areas, it was argued, because a drive from New Guinea to the Philippines would be a frontal assault against large islands with positions closely arranged in depth for mutual support. The Central Pacific route, in contrast, permitted the continuously expanding U.S. Pacific Fleet to strike at small, vulnerable positions too widely separated for mutual support.

The Joint Chiefs decided on the two axes, rather than the Central Pacific alone, because the Japanese conquests in the first phase of the war had compelled the establishment of comparatively large Allied forces in the South and Southwest Pacific Areas; to shift all these to the Central Pacific would take too much time and too many ships, and would probably intensify the already strong and almost open disagreement between MacArthur and King over Pacific strategy. Further, the Joint Chiefs hoped to use the oil fields on the Vogelkop Peninsula.3 Twin drives, coordinated and timed for mutual support, would give the U.S. forces great strategic advantages, for the Japanese would never know where the next blow would fall.4

At Washington in May the Combined Chiefs, as they had at Casablanca, approved plans for seizure of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands as the opening phase of the Central Pacific advance. They also approved the existing plans for CARTWHEEL, which the Joint Chiefs estimated would be ended by April 1944.

Next month, the Joint Chiefs, concerned with the problem of coordinating Nimitz’ and MacArthur’s operations, asked MacArthur for specific information on organization of forces and dates for future operations and informed him that they were planning to start the Central Pacific drive in mid-November. They planned to use the 1st and 2nd Marine Divisions, then in the Southwest and South Pacific Areas, respectively, all the South Pacific’s assault transports and cargo ships (APAs and AKAs), and the major portion of naval forces from Halsey’s area.5

Faced with the possibility of a rival offensive, using divisions and ships that he had planned to employ, General MacArthur hurled back a vigorous reply. Arguing against the Central Pacific (he

called the prospective invasion of the Marshalls a “diversionary attack”), he set forth the virtues of advancing through New Guinea to the Philippines. Withdrawal of the two Marine divisions, he maintained, would prevent the ultimate assault against Rabaul. He concluded his message with the information on target dates and forces that the Joint Chiefs had requested.6 Two days later, 22 June, Admiral Halsey protested the proposed removal of the 2nd Marine Division and most of his ships.7

Although General MacArthur may not have known it at the time, his argument that transfer of the two divisions would jeopardize the Rabaul invasion was being vitiated. In 1942 there had been general agreement that Rabaul should be captured, but in June 1943 members of Washington planning committees held that a considerable economy of force would result if Rabaul was neutralized rather than captured.8 The Joint Strategic Survey Committee, in expressing itself in favor of giving the Central Pacific offensive priority over CARTWHEEL, also argued that the Allied drive northward against Rabaul was merely a reversal of the Japanese strategy of the year before and held “small promise of reasonable success in the near future.”9

On the other hand Admiral William D. Leahy, chief of staff to the President and senior member of the Joint Chiefs, was always a strong supporter of MacArthur’s views.10 He argued strongly against any curtailment of CARTWHEEL. Admiral King, however, was far from pleased (in June 1943) with the rate of “inch by inch” progress in the South and Southwest Pacific. He wanted to see Rabaul “cleaned up” so the Allies could “shoot for Luzon,” and seemed to imply that if CARTWHEEL did not move faster he would favor a curtailment.11

The immediate question on the transfer of the Marine divisions was compromised. The 1st Marine Division would remain in the Southwest Pacific. The 2nd Marine Division, heretofore slated for the invasion of Rabaul, was transferred from New Zealand to the Central Pacific, where it made its bloody, valorous assault on Tarawa in November 1943. Assured by King that the Central Pacific offensive would assist rather than curtail CARTWHEEL, Leahy withdrew his objections.12

By 21 July the arguments against capturing Rabaul had so impressed General Marshall that he radioed MacArthur to suggest that CARTWHEEL be followed by the seizure of Kavieng on New Ireland and Manus in the Admiralties, with the

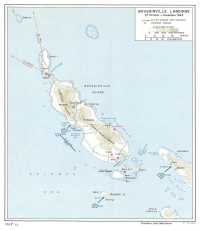

Map 15: Bougainville Landings, 27 October–1 November 1943

purpose of isolating Rabaul, and by the capture of Wewak. But MacArthur saw it otherwise. Marshall’s plan, he stated, involved too many hazards. Wewak, too strong for direct assault, should be isolated by seizing a base farther west. Rabaul would have to be captured rather than just neutralized, he insisted, because its strategic location and excellent harbor made it an ideal naval base with which to support an advance westward along New Guinea’s north coast.13

Marshall and King were not convinced. Thus the Combined Chiefs, meeting with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill in Quebec during August, received and approved the Joint Chiefs’ recommendation that Rabaul be neutralized, not captured. They further agreed that after CARTWHEEL MacArthur and Halsey should neutralize New Guinea as far west as Wewak, and should capture Manus and Kavieng to use as naval bases for supporting additional advances westward. Once these operations were concluded, MacArthur was to move west along the north coast of New Guinea to the Vogelkop Peninsula. Subsequently MacArthur was informed that his cherished ambition to return to the Philippines would be realized; Marshall radioed him that once the Vogelkop was reached, the Southwest Pacific’s next logical objective would be Mindanao.14

Papers containing the Combined Chiefs decisions were delivered to General MacArthur by Col. William L. Ritchie of the Operations Division, War Department General Staff, who reached GHQ on 17 September.15

From then on MacArthur did not raise the question of Rabaul with the Joint Chiefs; his radiograms dealt instead with broader questions relating to the Philippines and the relative importance of the Central and Southwest Pacific offensives.16 Although the evidence is not conclusive, the general course of events and certain opinions MacArthur gave during the planning for Bougainville seem to indicate that he knew of the decision to neutralize rather than capture Rabaul, or else had reached the same decision independently, some time before Colonel Ritchie reached the Southwest Pacific.

The General Plan

If ever a series of offensives was conducted according to plan, it was the extremely systematic Allied moves in the Pacific that started in 1943. At the time that Allied forces were fighting in New Guinea and New Georgia, the Joint Chiefs were considering the wisdom of neutralizing Rabaul, and General MacArthur and Admiral Halsey were preparing for the invasion of Bougainville.

ELKTON III had initially provided that the southern Bougainville area (Buin and Faisi) was to be invaded during the

fifth month after the beginning of CARTWHEEL, simultaneously with the conquest of New Georgia, and one month before the invasion of Cape Gloucester. (See Chart 2.) Admiral Halsey had altered the plan by managing to start his invasion of New Georgia on 30 June. In June General MacArthur, in ordering the Markham Valley–Huon Peninsula attack, directed Admiral Halsey to be ready to take southern Bougainville on orders from GHQ.17 At this time Admiral Halsey, planning in accordance with ELKTON III, intended to use the 3rd Marine Division and the 25th Division against southern Bougainville, the 2nd Marine and 3rd New Zealand Divisions against Rabaul.18 Before long, however, the 25th Division, sent into New Georgia, was too worn for further combat and the 2nd Marine Division was ordered to invade the Gilberts instead of Rabaul.19

Tactical planning for Bougainville began in the South Pacific in July when Halsey assigned the Commanding General, I Marine Amphibious Corps, to command the ground forces.(Map 15) His mission was the seizure of Buin, Kahili, and Tonolei Harbor on southern Bougainville and of the nearby islands in Bougainville Strait—the Shortlands, Faisi, and Ballale, where there were then an estimated twenty thousand Japanese soldiers and sailors.

Near the end of July Admiral Halsey suggested a change in plan to General MacArthur. It was based on two assumptions: first, that the objectives of the operation were denying the use of airfields and anchorage to the Japanese and securing airfields and anchorages for the Allies, as a step toward the capture of Rabaul; and second, that because terrain, strategic position, and Japanese dispositions indicated that southern Bougainville was extremely important to the Japanese, the operation would be a major one. With the difficulties of the then bogged-down New Georgia invasion and the success of the artillery on the offshore islands against Munda both obviously in mind, he suggested that he could save men, matériel, and time by avoiding the Bougainville mainland completely. He proposed to seize the Shortlands and Ballale, to emplace artillery on the former with the mission of interdicting Kahili, to build one or more airfields in the Shortlands, and to use the anchorages there that the Japanese 8th Fleet then employed regularly. MacArthur heartily approved the scheme.20

By early September, however, Admiral Halsey had decided on a further change

in plan. Several factors influenced his decision. The impressive and inexpensive success on Vella Lavella had demonstrated once more the validity of the old principle of striking soft spots, when possible, in preference to headlong assault against fixed positions. Further, reconnaissance had indicated that airdrome sites on the Shortlands were not very good. Landing in the Shortlands, which the Japanese were believed to be reinforcing, would entail heavy losses; poor beaches would impede the landing of heavy construction equipment and artillery for the neutralization of Kahili. It was also estimated that assaulting the Shortlands–Ballale–Faisi area would require two divisions, while two more would be needed to operate on southern Bougainville proper. As the South Pacific had but four divisions—the 37th and Americal Divisions of the U.S. Army, the 3rd Marine Division, and the 3rd New Zealand Division—that were considered fit to fight, no more advances would be possible for months.21

Looking for a method of neutralizing the southern Bougainville–Shortlands area without capturing it, a method that would retain enough troops for a major forward move later, Halsey acted on the advice of his principal subordinate commanders. He decided in favor of increased air effort from the New Georgia fields against southern Bougainville and Buka. Starting about 1 November, he proposed to capture the Treasury Islands and Choiseul Bay as airfield, radar, and PT base sites from which to “contain and strangle” southern Bougainville and the Shortlands. He proposed that after the mainland of Bougainville had been reconnoitered he and MacArthur could decide whether to advance from Choiseul to Kieta on the east coast or from the Treasuries to Empress Augusta Bay on the west if post-CARTWHEEL plans required the establishment of positions on the mainland of Bougainville.22

This plan was consistent with ELKTON III, and varied only slightly from the July schemes approved by MacArthur. But by now, MacArthur, perhaps aware of the decision to neutralize rather than capture Rabaul, and obviously anxious to hurry up CARTWHEEL and get started on the drive toward the Philippines, had changed his mind about the scope and nature of the operation. Thus when Halsey’s chief of staff, Rear Adm. Robert B. Carney, and his new war plans officer, Col. William E. Riley, USMC, presented the Treasuries–Choiseul plan to MacArthur at GHQ on 10 September, MacArthur was against it. With the successful airborne move to Nabzab in mind, he expressed his agreement with the principle of the bypass, but maintained that Halsey’s plan would make it impossible for South Pacific aircraft to hit at Rabaul effectively before 1 March

1944. He wanted Halsey’s aircraft established within fighter range of Rabaul in time to assist with the neutralization of Rabaul that would cover the Southwest Pacific’s invasion of Cape Gloucester. This would be necessary, MacArthur held, because Southwest Pacific air forces could not attack all the objectives (including Madang and Wewak) that would have to be neutralized in order to protect the invasions of Cape Gloucester and of Saidor, on the north coast of the Huon Peninsula. Southwest Pacific headquarters hoped to start Operation III (chiefly Cape Gloucester) shortly after 1 December; Cape Gloucester itself would probably be invaded between 25 December 1943 and 1 January 1944. Therefore it would be necessary for South Pacific forces to establish themselves on the mainland of Bougainville about 1 November. So important was the operation that MacArthur tacitly approved commitment of the major part of South Pacific ground forces.

Specifically, he proposed the following outline plan:–

15 October–1 November, Southwest Pacific air forces would make heavy attacks against Japanese aircraft, air installations, and shipping at Rabaul;

20–25 October, South Pacific forces would occupy the Treasuries and positions on northern Choiseul in order to establish radar positions and PT boat bases;

1 November, South Pacific forces would occupy Empress Augusta Bay on the west coast of Bougainville in order to establish airfields within fighter range of Rabaul;

1–6 November, the Southwest Pacific would continue air attacks on Rabaul and would assist in the neutralization of Buka;

25 December 1943–1 January 1944, Southwest Pacific forces would seize Cape Gloucester and Saidor in order to gain control of Vitiaz and Dampier Straits and to secure airdromes for the neutralization of Kavieng. During this period South Pacific forces would neutralize Rabaul.23

General MacArthur stressed the importance of a landing on the mainland at another meeting on 17 September attended by General Harmon and Colonel Riley. Asked if he preferred a landing on the east or the west coast of Bougainville, he put the decision entirely in Admiral Halsey’s hands.

And so on 22 September, Halsey issued warning orders which canceled all his earlier plans and assigned the units to constitute the invasion force. Admiral Wilkinson would lead it. The landing forces, under Wilkinson, were still to be under the commanding general of the I Marine Amphibious Corps. Halsey instructed Wilkinson and his units to be ready to carry out one of two plans: either they were to seize and hold the Treasury Islands and the airfield sites in the Empress Augusta Bay region on the west coast of Bougainville; or they were to seize the Treasuries and Choiseul Bay, build airfields, PT boat bases, and landing craft staging points, and in late December seize the Japanese

airfield at Tenekau on the east coast of Bougainville.24

Submarines took patrols to the east coast and to Empress Augusta Bay to gather data, and South Pacific intelligence officers interviewed missionaries, traders, planters, coastwatchers, and fliers who had been shot down over Bougainville. The east coast patrol, carried by the submarine Gato, delivered an unfavorable report. The west coast patrol, composed of marines, debarked from the submarine Guardfish about ten miles northwest of Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay. The marines were unable to examine Cape Torokina because it was occupied by the Japanese, but they took samples of soil similar to that at Torokina. When tested, it showed that Cape Torokina was suitable for airfields.

Between the sea and the mountains at Cape Torokina, which lay within fighter range of Munda, was a coastal plain of about seven square miles. It was lightly defended; Halsey estimated that there were about one thousand Japanese in the area. So forbidding were the surrounding mountains that the area was almost isolated from the strong Japanese garrisons in southern Bougainville. Halsey and his planners estimated that if Allied forces seized Torokina the Japanese would require three or four months to bring enough heavy equipment over the mountains to launch an effective counterattack. But there were disadvantages. The heavy surf in Empress Augusta Bay, which had no protected anchorages, would make landing operations difficult. No more than 65 miles separated the cape from all the Japanese air bases on Bougainville, and Rabaul was only 215 miles to the northwest.

Admiral Halsey calculated the chances and decided on Torokina. In his words: “The conception was bold and the probability of provoking a violent air-land-surface action was accepted and welcomed on the premise that the by-products of enemy destruction would, in themselves, greatly further the over-all Pacific plan. Enthusiasm for the plan was far from unanimous, even in the South Pacific, but, the decision having been made, all hands were told to ‘Get going.’”25

Halsey informed MacArthur of his decision on 1 October. Expressing his complete agreement, MacArthur promised maximum air support from the Southwest Pacific. The invasion would be launched on 1 November.26

Air Operations in October

The Fifth Air Force

By October the Fifth Air Force in the Southwest Pacific Area was well situated

to carry the fight against Rabaul.27 Nearly all its warplanes had been displaced to forward bases. Port Moresby, an outpost in 1942, was now a rear base. Dobodura was the main staging base for heavy bombers, and Nadzab was being readied as the main base for future operations. P-38s from New Guinea could stage through Kiriwina and escort the bombers all the way to Rabaul.

Rabaul was ripe for air attack. Transports, cargo ships, and smaller craft, together with some warships, crowded Simpson Harbor. Supply depots were fully stocked. Four all-weather airfields—Lakunai, Vunakanau, Rapopo, and Tobera—were in operation in and near Rabaul.28

Southwest Pacific aircraft had been harrying Rabaul with small raids since January 1942, but now the Allies were ready to attack this bastion on a large scale. General Kenney was ready for the first big attack on 12 October. All together, 349 planes took part: 87 heavy bombers, 114 B-25s, 12 Beaufighters, and 125 P-38s, plus some weather and photo reconnaissance planes—or, as he put it, “Everything that I owned that was in commission, and could fly that far.”29 B-25s and Beaufighters made sweeps over Vunakanau, Rapopo, and Tobera while the heavy bombers struck at shipping. The Allies lost four planes and estimated a great deal of damage to Japanese aircraft and ships. Their estimates were somewhat exaggerated, especially those on shipping damage, but some Japanese planes were destroyed. The Japanese, taken by surprise and unable to send up fighters to intercept, later reported that this and later raids in October were “a great obstacle to the execution of operations.”30

Bad weather over New Guinea halted Kenney’s operations against Rabaul for the next few days. The Japanese used the respite to send out attacks against Oro Bay on 15 and 17 October, and Finschhafen on 17 and 19 October. The Allied planes did not sit idle while Rabaul was inaccessible, but struck at Wewak on the 16th and again the next day.

Kenney planned and sent out another big raid against Rabaul on 18 October, but when the air armada was over the Solomon Sea the weather closed in. Fifty-four B-25s went on to Rabaul anyway. Kenney followed this attack with three successive daylight raids on 23, 24, and 25 October before the weather again imposed a delay, this time until the 29th, when B-24s and P-38s bombed Vunakanau.

The weather intervened again, so that it was not until 2 November, the day after South Pacific forces landed at

Bombing Rabaul. Japanese corvette off the coast of New Britain near Rabaul suffers a direct hit from a B-25

Vunakanau airfield is attacked by low-flying bombers dropping parachute bombs

Empress Augusta Bay, that Southwest Pacific aircraft again struck at Rabaul. On that day seventy-five B-25s escorted by P-38s attacked and ran into the fiercest opposition the Fifth Air Force encountered during World War II. A large number of carrier planes and pilots from the Combined Fleet at Truk had just been transferred to Rabaul, and they put up a stiff fight.

Although it is clear that these raids failed to wreak as much havoc at Rabaul as Kenney’s fliers claimed, it is also clear that they caused a good deal of damage to aircraft and prevented the Japanese planes at Rabaul from undertaking any purely offensive missions. In short, the Southwest Pacific’s air support for the Bougainville invasion, though not as devastating as was thought at the time, was effective.

Certainly American pilots, like the Japanese, and like soldiers and sailors on the ground and in ships, tended to exaggerate the damage they inflicted. But there were two important differences between American and Japanese claims. First, Japanese claims were wildly exaggerated whereas American claims were merely exaggerated. Second, Japanese commanders apparently took the claims seriously, so that nonexistent victories often served as the bases for decision. On the other hand American commanders, taking human frailty into account, evaluated and usually scaled down claims so that decisions were normally based on more realistic estimates of damage.

Air Command, Solomons

General Twining’s composite force, Air Command, Solomons, had been striking hard at the northern Solomons bases during the same period and for the same purpose—to knock out the Bougainville bases so that Wilkinson’s convoys could sail past in safety. Twining’s available air strength had been displaced forward to bases within range of south Bougainville targets. At the start of operations in October, Twining had 614 Army, Navy, Marine Corps, and Royal New Zealand Air Force planes. Of these, 264 fighters and 223 medium, dive, torpedo, and patrol bombers were at New Georgia and the Russells, and 127 heavy bombers and patrol planes were at Guadalcanal.

Ever since 1942 South Pacific planes had been battering at the Japanese bases at Kahili, the Shortlands, Ballale, Kieta, and Buka, and now the process was intensified in an effort to put them out of commission.31 Starting on 18 October, Twining—whose high professional qualifications were matched by a physical appearance so striking that he looked like Hollywood’s idea of a diplomat—drove his interservice, international force hard in a continuous series of high-level, low-level, dive, glide, and torpedo bombing attacks and fighter sweeps, all made with escorting fighters from the four air services in the command. The primary mission was accomplished. The hard-hit enemy showed skill and determination in keeping his airfields in repair, but these qualities were not enough. By 1 November all his Bougainville airfields had been knocked out of commission, and the continuous attacks kept them that way.

B-25s leaving Bougainville after an attack on airfields and supply areas

The Japanese

Of Admiral Kusaka’s 11th Air Fleet, a substantial portion was based at Rabaul in early October, the remainder in southern Bougainville. When Air Command, Solomons, intensified its operations, Kusaka withdrew his planes to Rabaul, and to avoid being completely destroyed by Kenney’s heavy raids he frequently pulled his planes back to Kavieng in New Ireland. Despite these attacks Kusaka was usually able to maintain about two hundred planes in operating condition at Rabaul throughout October.

Now Admiral Koga, like the late Yamamato, decided to use his carrier planes jointly with the land-based planes of Kusaka’s air fleet in an effort to improve the situation in the Southeast Area. As a result of the September decision to withdraw the main defensive perimeter, Koga developed a plan to cut the Allied lines of communication in the Southeast Area and so delay the Allies and buy time for the Japanese to build up the defenses along the main perimeter. This plan, called Operation RO, was to be executed by the operational carrier air groups of the Combined Fleet, transferred from Truk to Rabaul, and by the 11th Air Fleet. Vice Adm. Tokusaburo Ozawa, commander of the 3rd Fleet, and Kusaka would conduct the operation jointly from Rabaul. Koga decided on this course of action fully aware that his surface strength would be immobilized

while his carrier planes were at Rabaul.

He had planned to transfer the planes in mid-October, but delayed the move because he received a false report that the U.S. Pacific Fleet was out against the Marshalls. On 20 October, now aware that Nimitz’ forces were not moving against the Marshalls, Koga ordered the carrier planes dispatched. By the beginning of November, 173 carrier planes—82 fighters, 45 dive bombers, 40 torpedo bombers, and 6 patrol planes—had reached Rabaul to team with Kusaka’s 200. It was Ozawa’s carrier pilots who gave Kenney’s men such a hard fight on 2 November. Koga had first planned to deliver his main stroke against New Guinea but the increased tempo of Allied activity in the Solomons made him decide to strike in the Solomons.

Koga’s decision to execute Operation RO was to have far-reaching results, results that were the precise opposite of what he expected. The transfer of the carrier planes coincided with the South Pacific’s invasion of Bougainville.

Forces and Tactical Plans

The Allies

Bougainville, the largest of the Solomon Islands, is 125 miles long on its northwest-to-southeast axis, and 30 to 48 miles wide.32 Its mountainous spine comprises two ranges, the Emperor and the Crown Prince. Two active volcanoes, 10,000-foot Mount Balbi and 8,000-foot Mount Bagana, send continual clouds of steam and smoke into the skies. Mount Bagana, a stark and symmetrical cone, overlooks Empress Augusta Bay and is the most outstanding feature of the region’s dramatic beauty.

The mountain range ends toward the southern part of the island, and there, on the coastal plain near Buin, the Japanese had built the airfields of Kahili and Kara. On the western coast the mountains slope down through rugged foothills and flatten out into a narrow and swampy coastal plain that is cut by many small rivers. These silt-laden streams constantly build bars across their own mouths and thus frequently change their courses.

Good harbors in varying stages of development were to be found at Buka, Numa Numa, Tenekau, Tonolei, and in the islands off the south coast. Empress Augusta Bay, exposed as it was to the open sea, was a poor anchorage. The Japanese had airfields at Buka and Bonis on either side of Buka Passage, at Tenekau, Kieta, Kara, and Kahili on the mainland, and at Ballale near the Shortlands, and had seaplane anchorages and naval bases in the Shortlands. As on all the other islands, there were no real motor roads, only native trails near the coasts plus a few that led through the mountains.

The native population consisted of over forty thousand nominally Christian Melanesians, who were slightly darker in color than their fellows in the southern Solomons. Before the war about a hundred white missionaries, planters,

traders, and government officials had lived on the island. Some of the natives, it was known, were pro-Japanese and had aided the enemy in rooting out the coastwatchers earlier in the year.

Allied intelligence agencies estimated enemy strength at about 37,500 soldiers and 20,000 sailors, and correctly reported that the Army troops belonged to the 17th Army, commanded by General Hyakutake, who had been responsible for the direction of the Guadalcanal Campaign.33 Over 25,000 of Hyakutake’s men were thought to be in the Buin–Shortlands area, with an additional 5,000 on the east coast of Bougainville, 5,000 more at Buka and Bonis, and light forces at Empress Augusta Bay. Air reconnaissance enabled the Allies to keep a fairly accurate count of Japanese warships and planes in the New Guinea–Bismarcks–Solomons area.

Admiral Halsey, in preparing his attack, was not embarrassed by too many ships. Admiral Nimitz was getting ready to launch his great Central Pacific advance in November and had removed many of Halsey’s ships, leaving him but eight transports and four cargo ships, or enough shipping to carry one reinforced division in the assault. Because South Pacific commanders expected the Japanese to oppose the invasion with vigorous air attacks, they decided not to use the slow LSTs for the assault. The South Pacific had one carrier force, Task Force 38 under Rear Adm. Frederick C. Sherman, consisting of the 910-foot aircraft carrier Saratoga, the light carrier Princeton, two antiaircraft cruisers, and ten destroyers. Nimitz, in response to Halsey’s requests for additional cruiser-destroyer and carrier task forces, assured Halsey that Central Pacific forces would be within reach to assist if necessary, and agreed to send Halsey another carrier task force on or about 7 November.34

Halsey issued the basic orders for the operation on 12 October. He organized five task forces similar to those that had made up the New Georgia attack forces. They were: Task Force 31 (the attack force), under Admiral Wilkinson; Task Force 33 (South Pacific land-based aircraft), under Admiral Fitch; Sherman’s Task Force 38; the cruisers and destroyers of Admiral Merrill’s Task Force 39; and Captain Fife’s submarines in Task Force 72.

The submarines were to carry out offensive reconnaissance in the waters of the Bismarck Archipelago, and would be supplemented in their work by Central Pacific submarines operating out of Pearl Harbor. Merrill’s ships would support the invasion by operating against enemy surface ships and by bombarding Buka and the Shortlands. Halsey also planned to employ Sherman’s Task Force 38 in a raid against Buka and Bonis, which lay beyond effective fighter range of the New Georgia airfields. Task Force 33 was ordered to carry out its usual missions of reconnaissance, destruction of enemy ships and aircraft, and air cover and support of the invasion force. Air

Command, Solomons, which was part of Task Force 33, was making its intensive effort during October against the Japanese airfields in southern Bougainville and the outlying islands, so that these areas could safely be bypassed. Arrangements for local air support were the same as for New Georgia. The local air commander with the invasion force was designated, as a subordinate of Twining’s, Commander, Aircraft, Northern Solomons, and would take command of all support aircraft as they took off from their bases.

Admiral Wilkinson’s invasion force, Task Force 31, consisted of eight transports, four cargo ships, two destroyer squadrons, mine craft, almost all the South Pacific’s PT squadrons, and a large force of ground troops under the Commanding General, I Marine Amphibious Corps (IMAC).

The ground commander was General Vandegrift, USMC, an apple-cheeked, deceptively soft-spoken Virginia gentleman, who had won distinction by his conduct of operations on Guadalcanal from 7 August 1942 until December of that year. Vandegrift was at this time slated to become commandant of the Marine Corps in Washington, but was given the Bougainville command temporarily because Maj. Gen. Charles D. Barrett, who had replaced Vogel in command of the I Marine Amphibious Corps, had met accidental death in Nouméa. Halsey’s choice for the corps command fell upon Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, USMC, another hero of Guadalcanal, who was then in Washington as Director of Marine Corps Aviation. Vandegrift was to exercise the command until Geiger could arrive.

Ground forces assigned to the attack included the following: I Marine Amphibious Corps headquarters and corps troops; 3rd Marine Division; 37th Division; 8th Brigade Group, 3rd New Zealand Division; 3rd Marine Defense Battalion; 198th Coast Artillery Regiment (Antiaircraft); 2nd Provisional Marine Raider Battalion; 1st Marine Parachute Battalion; naval construction and communications units, and a boat pool.

In area reserve, to be committed on orders from Admiral Halsey, were the Americal Division in the Fijis; the 2nd Battalion, 54th Coast Artillery (Harbor Defense) Regiment at Espiritu Santo; and the 251st Coast Artillery (Antiaircraft) Regiment in the Fijis.

Naming D Day as 1 November, the date for the invasion of Empress Augusta Bay, Halsey ordered Task Force 31 to seize and hold the Treasury Islands on D minus 5 (27 October) and establish radar positions and a small naval base. Wilkinson’s main attack would be the seizure of Empress Augusta Bay on 1 November, which would be followed by the speedy construction of two airfields on sites to be determined by ground reconnaissance after the troops had landed. Task Force 31 was initially ordered to be ready to establish a PT base on northern Choiseul. This part of the plan was changed on the recommendation of Vandegrift, who argued that the Treasury landings might reveal to the Japanese the intention to invade Empress Augusta Bay. Halsey, Wilkinson, and Vandegrift decided instead to use the 2nd Marine Parachute Battalion in a twelve-day raid on Choiseul which they hoped would mislead the enemy into

Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift

believing that the real objective lay on Bougainville’s east coast.35

Halsey made Wilkinson, whose headquarters was then at Guadalcanal, responsible for coordination of all amphibious plans. Wilkinson was to command all elements of Task Force 31 until, at a time agreed upon by him and the ground commander, direction of all air, ground, and naval forces at Empress Augusta Bay would be transferred to the latter.

Wilkinson divided Task Force 31 into a northern force, which he commanded himself, for the main attack and a southern force, led by Admiral Fort, for the Choiseul raid and the seizure of the Treasuries. The assault echelon of the northern force, scheduled to land at Empress Augusta Bay on D Day, included destroyers, the transports and cargo ships, and Maj. Gen. Allen H. Turnage’s 3rd Marine Division, less one regimental combat team and plus supporting units. The Treasuries echelon of the southern force was made up of 8 APDs, 2 LSTs, 8 LCIs, 4 LCTs, 2 APCs, the 8th Brigade Group of the 3rd New Zealand Division, the 198th Coast Artillery, A Company of the 87th Naval Construction Battalion, and communications and naval base detachments. The parachute battalion would be transported by four APDs escorted by destroyers. The 37th Division, in corps reserve, would be picked up at Guadalcanal by the northern force transports and would start arriving at Bougainville soon after D Day to help hold the beachhead.

Guadalcanal and the Russells were to serve as the main staging and supply bases. However, the shortage of shipping led the I Marine Amphibious Corps to shorten the lines by establishing a supply base at Vella Lavella. Plans called for

the Vella depot to be stocked with a thirty-day supply of rations and petroleum products, but so strained was South Pacific shipping that only a ten-day supply had been stocked at Vella Lavella by 1 November.

During the last half of October the ground units completed their training and conducted final rehearsals. The 3rd Marine Division, part of which had served in Samoa in 1942 before joining the main body in New Zealand, had recently transferred from New Zealand to Guadalcanal. It completed its amphibious and jungle training there and rehearsed for Empress Augusta Bay in the New Hebrides from 16 to 20 October. The 37th Division, returned from New Georgia to Guadalcanal in September, likewise conducted amphibious and jungle training at Guadalcanal. The 3rd Marine Defense Battalion, which after serving in the Guadalcanal Campaign had been sent to New Zealand and from there back to Guadalcanal, rehearsed there. The 8th Brigade practiced landings at Efate en route to Guadalcanal from New Caledonia, and from 14 to 17 October rehearsed at Florida.

The Japanese

The Japanese fully expected Halsey to attack Bougainville and were busy preparing to meet the invasion. Imperial Headquarters’ orders in September had stressed the importance of Bougainville as an outpost for Rabaul, and General Imamura had instructed General Hyakutake to make ready. This the 17th Army commander did, acting in conjunction with the commander of the 8th Fleet. The Japanese planned to use air and surface strength to smash any Allied attempt at invasion before the assault troops could get off their transports. But if troops did succeed in getting ashore, the Japanese hoped to attack and destroy their beachheads.

Hyakutake’s army consisted mainly of the 6th Division, Lt. Gen. Masatane Kanda commanding. (This division had acquired an unsavory reputation for indiscipline by its sack of Nanking, China, in 1937). Also assigned were the 4th South Seas Garrison Unit (three infantry battalions and one field artillery battery), and field artillery, antiaircraft artillery, and service units. Imamura was sending four rifle battalions and one artillery battalion of the 17th Division from New Britain to northern Bougainville; these were due in November.36

Hyakutake, whose headquarters was on tiny Erventa Island near Tonolei Harbor, had disposed most of his strength to cover the Shortlands, Buin, and Tonolei Harbor, the rest to protect Kieta and Buka. Some 26,800 men—20,000 of the 17th Army and 6,800 of 8th Fleet headquarters and naval base forces—and an impressive number of guns ranging from machine guns to 140-mm. naval rifles were stationed in southern Bougainville and the islands. Over 4,000 men were at Kieta, and the arrival of the 17th Division units would bring the Buka Passage garrison to 6,000.37

The unpromising nature of the terrain on the west coast of Bougainville had convinced Hyakutake that the Allies would not attempt to land there. Consequently only a small detachment was stationed at Empress Augusta Bay. Hyakutake was aware that he would be outnumbered and outgunned in any battle, but like most of his fellow Japanese generals he placed great faith in the superior morale he believed his troops possessed.

“The battle plan is to resist the enemy’s material strength with perseverance, while at the same time displaying our spiritual strength and conducting raids and furious attacks against the enemy flanks and rear. On this basis we will secure the key to victory within the dead spaces produced in enemy strength, and, losing no opportunities, we will exploit successes and annihilate the enemy.”38 Pride goeth before destruction, and an haughty spirit before a fall.

Preliminary Landings

The Treasuries

The assault echelon of Admiral Fort’s southern force consisted of five transport groups: the advance transport group with 8 APDs and 3 escorting destroyers; the second with 8 LCI(L)s, 2 LCI(G)s,39 and 6 destroyers; the third with 2 LSTs, 2 destroyers, and 2 minesweepers; the fourth with 1 APC, 3 LCTs, and 2 PT boats; the fifth with 1 APC, 6 LCMs, and a rescue boat.40 These ships loaded troops and supplies at Guadalcanal, Rendova, and Vella Lavella and departed for the Treasuries on 26 October. Their departures were timed for the five groups to arrive in Blanche Harbor, which is between Mono and Stirling Islands, between 0520 and 0830, 27 October.41 All possible measures were taken to avoid detection, because the small forces had to get established in the Treasuries before the Japanese were able to send in reinforcements from their ample reserves in the nearby Shortlands. But detection was almost inevitable in an operation so close to enemy bases, and at 0420, 27 October, a reconnaissance seaplane sighted the ships near the Treasuries and reported their presence. Admiral Merrill’s task force, covering the operation some distance westward, was also discovered.

Heavy rain fell as the leading APDs arrived off the western entrance to Blanche Harbor. Low-hanging clouds obscured the jungled hills of Mono Island. As Blanche Harbor was too narrow

to permit ships to maneuver safely, the fire support destroyers and seven APDs remained west of the harbor. While the troops boarded the landing craft, destroyers opened fire on the landing beaches on Mono’s south shore, and the minesweepers checked Blanche Harbor. At the same time the APD McKean put a radar party ashore on Mono’s north coast.

Covered by the destroyers’ gunfire and accompanied by the LCI gunboats, the first wave of LCP(R)s, carrying elements of two battalions of the 8th Brigade, moved through the channel in the wet, misty half-light. There were only a handful of Japanese on Mono, some 225 men of the special naval landing forces. The naval bombardment drove most of the defenders out of their beach positions, and as the New Zealand infantry went ashore they drove out or killed the Japanese in the vicinity of the beach. However, enemy mortars and machine guns from hidden positions in the jungle fired on the landing beaches and on the LSTs of the fourth transport group, which beached at 0735. This fire caused some casualties, damaged some weapons and equipment, and delayed the unloading. But before noon the 8th Brigade troops captured two 75-mm. guns and one 90-mm. mortar and resistance to the landing ceased.

Stirling Island, which was not occupied by the enemy, was secured by a battalion during the morning. A total of 2,500 men—252 Americans of the 198th Coast Artillery and several detachments from other units, the rest New Zealanders—had been landed on the south shore of Mono. The radar detachment and accompanying combat troops that had landed on the north coast of Mono numbered 200.

Meanwhile the American destroyers were busy. In addition to providing fire support for the landings they escorted the unloaded transport groups back to Guadalcanal. Two picket destroyers with fighter director teams aboard were stationed east and west of the Treasuries to warn against enemy air attacks.

General Hyakutake had decided that the Treasury landings were a preliminary to a systematic operation, and that the Allies would build an airfield on the Treasuries, take Choiseul, and after intensified air and surface operations, would land three divisions on southern Bougainville in late November. He felt that they might possibly invade Buka. Warning that the recent decline in Japanese naval strength might cause the Allies to move faster, he stressed the importance of building up the south Bougainville defenses. In short, he believed just what the Allies hoped he would.

When Admiral Kusaka at Rabaul was notified of the Allied landing, he brought some planes forward from Kavieng and sent fighters and dive bombers against the Allies. Most of these were headed off by the New Georgia-based P-38s and P-40s that formed the southern force’s air cover, but some got through to damage the picket destroyer Cony and harass the retiring LSTs. The Japanese pilots reported that they had sunk two transports and two cruisers.

On shore, Brigadier R. A. Row of the New Zealand Army, the landing force commander, set up beach defenses. By 12 November his troops had killed or captured the enemy garrison which had

fled into the hills of Mono. Two hundred and five Japanese corpses were counted; 40 New Zealanders and 12 Americans had been killed, 145 New Zealanders and 29 Americans wounded.

Succeeding transport echelons, thirteen in all, brought in more troops and equipment from 1 November 1943 through 15 January 1944. During this period the boat pool, an advanced naval base, and radars were established; these supported the main operation at Empress Augusta Bay. Seabees of the U.S. Navy built a 5,600-foot-long airstrip on Stirling that was ready to receive fighter planes on Christmas Day.

The Choiseul Raid

Four of the APDs that had carried Brigadier Row’s troops to the Treasuries sailed to Vella Lavella on 27 October and there took aboard 725 men of Lt. Col. Victor H. Krulak’s 2nd Marine Parachute Battalion, plus fourteen days’ rations and two units of fire. Escorted by the destroyer Conway, the APDs steamed for the village of Voza on Choiseul, and that night landed the parachutists and their gear.

General Vandegrift had ordered Krulak so to conduct operations that the Japanese would believe a large force was present. Krulak therefore raided a barge staging point at Sagigai, some eight miles from Voza, and then sent strong combat patrols to the western part of Choiseul. But by 2 November the Japanese appeared to be concentrating at Sagigai with the obvious intention of destroying the 2nd Parachute Battalion. From eight hundred to one thousand enemy were reported to have moved into Sagigai from positions farther east, with more on the way. By now the Empress Augusta Bay landing had been safely executed, and Vandegrift ordered Krulak to withdraw. The battalion embarked on three LCIs in the early morning hours of 4 November. The raid cost 11 Marines dead, 14 wounded; 143 Japanese were estimated to have been slain.

Japanese sources do not indicate what estimates Imamura and Hyakutake placed on the operation. However, since Hyakutake expected that Choiseul would be invaded after the Treasuries and before southern Bougainville, it is not unlikely that Krulak’s diversion confirmed his belief that southern Bougainville was the main Allied objective.

Seizure of Empress Augusta Bay

Supporting Operations

In invading Empress Augusta Bay, Halsey’s forces were bypassing formidable enemy positions in southern Bougainville and the Shortlands, and placing themselves within close range of all the other Bougainville bases, as well as within fighter range of Rabaul—thus the strong air attacks by the Fifth Air Force and the Air Command, Solomons. In addition, Halsey had planned to make sure that the Japanese bases on Bougainville were in no condition to launch air attacks during the main landings on 1 November.42 Forces assigned to this

mission were the 2 carriers, 2 antiaircraft light cruisers, and 10 destroyers of Admiral Sherman’s Task Force 38 and the 4 light cruisers and 8 destroyers of Admiral Merrill’s Task Force 39.

Task Force 38 sortied from Espiritu Santo on 29 October, Task Force 39 from Purvis Bay on Florida Island on 31 October. Both were bound initially for Buka.

Merrill, sailing well south of the Russells and west of the Treasuries on his 537-mile voyage in pursuance of Halsey’s tight schedule, got there first. He arrived off Buka Passage at 0021, 1 November, and fired 300 6-inch and 2,400 5-inch shells at Buka and Bonis fields. Shore batteries replied but without effect. Merrill then retired at thirty knots toward the Shortland Islands. Enemy planes harassed the task force but the only damage they did was to the admiral’s typewriter. One fire started by the bombardment was visible from sixty miles away.

About four hours after the beginning of Merrill’s bombardment Task Force 38 reached a launching position some sixty-five miles southeast of Buka. This was the first time since the outbreak of the war in the Pacific that an Allied aircraft carrier had ventured within fighter range of Rabaul, and the first tactical employment of an Allied carrier in the South Pacific since the desperate battles of the Guadalcanal Campaign. In Admiral Sherman’s words:

“We on the carriers had begun to think we would never get any action. All the previous assignments had gone to the shore-based air. Admiral Halsey had told me that he had to hold us for use against the Japanese fleet in case it came down from Truk. ...”43

The weather was bad for carrier operations as the planes detailed for the first strike, a force made up of eighteen fighters, fifteen dive bombers, and eleven torpedo bombers, prepared to take off in the darkness. The sea was glassy and calm; occasional rain squalls fell. There was no breeze blowing over the flight decks, and the planes had to be catapulted into the air, a slow process that, coupled with the planes’ difficulties in forming up in the dark, delayed their arrival over Buka until daylight. Two torpedo bombers and one dive bomber hit the water upon take-off, doubtless because of the calm air. The rest of the planes dropped three 1,000-pound bombs on Buka’s runway and seventy-two 100 pound bombs on supply dumps and dispersal areas.

The next strike—fourteen fighters, twenty-one dive bombers, and eleven torpedo bombers—was launched at 0930 without casualties. These planes struck Buka again and bombed several small ships offshore. At dawn the next morning, 2 November, forty-four planes attacked Bonis, and at 1036 forty-one more repeated the attack. Then Sherman, under orders from Halsey, headed for the vicinity of Rennell, due south of Guadalcanal, to refuel. In two days of action Task Force 38, operating within sixty-five miles of Buka, estimated that it had destroyed about thirty Japanese planes and hit several small ships. More important, it had guaranteed that the Buka and Bonis runways could not be used for air attacks against Admiral Wilkinson’s

Maj. Gen. Allen H. Turnage (right) and Commodore Laurence F. Reifsnider aboard a transport before the landings on Bougainville

ships. The Americans lost seven men and eleven planes in combat and operational crashes.

Meanwhile Merrill’s ships had sped from Buka to the Shortlands in the early morning hours of 1 November to bombard Poporang, Ballale, Faisi, and smaller islands. Merrill had bombarded these before, on the night of 29-30 June, but in stormy darkness. Now the bombardment was in broad daylight; it started at 0631, seventeen minutes after sunrise. Japanese shore batteries replied with inaccurate fire. Only the destroyer Dyson was hit, and its casualties and damage were minor. His mission completed, Merrill headed south.

Approach to the Target

The last days of October found Wilkinson’s ships busy loading and rehearsing at Guadalcanal and the New Hebrides.44 Wilkinson had organized his eight

transport and four cargo ships of Task Force 31’s northern force into three transport divisions of four ships each. A reinforced regiment of marines was to be carried in each of two of the divisions, the reinforced 3rd Marine Defense Battalion in the third. The four transports of Division A, carrying 6,421 men of the 3rd Marines, reinforced, departed Espiritu Santo on 29 October and steamed for Koli Point on Guadalcanal. There Admiral Wilkinson and General Vandegrift boarded the George Clymer. General Turnage, 3rd Marine Division commander, and Commodore Laurence F. Reifsnider, the transport group commander, had come up from the New Hebrides rehearsal in the Hunter Liggett. Transport Division B, after the rehearsal, took the 6,103 men of the reinforced 9th Marines from the New Hebrides and in the late afternoon of 30 October joined with the four cargo ships of Transport Division C south of San Cristobal. Division C carried the reinforced 3rd Marine Defense Battalion, 1,400 men, and a good deal of heavy equipment.

All transport divisions, plus 11 destroyers, 4 destroyer-minesweepers, 4 small minesweepers, 7 minelayers, and 2 tugs, rendezvoused in the Solomon Sea west of Guadalcanal at 0740, 31 October. They sailed northwestward until 1800, then feinted toward the Shortlands, and after dark changed course again toward the northwest. During the night run to Empress Augusta Bay PB4Y4s (Navy Liberators), PV-1s (Vega Ventura night fighters), and PBYs (Black Cats) covered the ships. Enemy planes were out that night and made contact with the covering planes but apparently did not spot the ships, for none was attacked and Japanese higher headquarters received no warnings.

Empress Augusta Bay was imperfectly charted and the presence of several uncharted shoals was rightly suspected. Consequently Wilkinson delayed arrival at the transport area until daylight so that masthead navigation could be used to avoid the shoals.

The Landings

At 0432 of 1 November, Wilkinson’s ships changed course from northwest to northeast and approached Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay. Speed was reduced from fifteen to twelve knots. The minesweepers went out ahead to check the area. General quarters sounded on all ships at 0500, and forty-five minutes later the ships reached the transport area. The transport Crescent City struck a reef but suffered no damage.

Sunrise did not come until 0614, but the morning was bright and clear enough for the warships to begin a slow, deliberate bombardment of Cape Torokina at 0547. As each transport passed the cape it too fired with its 3-inch and antiaircraft guns. Wilkinson set H Hour for the landing at 0730. At 0645 the eight transports anchored in a line pointing north-northwest about three thousand yards from shore; the cargo ships formed a similar line about five hundred yards to seaward of the transports.

Wilkinson, sure that the Japanese would launch heavy air attacks, had come

Mount Bagana

so lightly loaded that four to five hours of unloading time would find his ships emptied. Vandegrift and Turnage, anticipating little opposition at the beach, had planned to speed unloading by sending more than seven thousand men ashore in the assault wave. They would land along beaches (eleven on the mainland and one on Puruata Island off Cape Torokina) with a total length of eight thousand yards.

The assault wave boarded landing craft at the ships’ rails. The winchmen quickly lowered the craft into the water; and the first wave formed rapidly and started for shore.

The scene was one to be remembered, with torpedo bombers roaring overhead, trim gray destroyers firing at the beaches, the two lines of transports and cargo ships swinging on their anchors, and the landing craft full of marines churning toward the enemy. This scene was laid against a natural backdrop of awesome beauty. The early morning tropical sun shone in a bright blue sky. A moderately heavy sea was running, so that at the shore a white line showed where the surf pounded on the black and gray beaches, which were fringed for most of their length by the forbidding green of the jungle. Behind were the rugged hills, and Mount Bagana, towering skyward, emitting perpetual clouds of smoke and steam, dominated the entire scene.

The destroyers continued firing until 0731, when thirty-one torpedo bombers from New Georgia bombed and strafed the shore line for five minutes. The first troops reached the beach at 0726, and in the next few minutes all the assault wave came ashore. There was no opposition except at Puruata Island and at Cape Torokina and its immediate vicinity. There the Japanese, though few in numbers, fought with skill and ferocity.

Cape Torokina was held by 270 Japanese soldiers of the 2nd Company, 1st Battalion, and of the Regimental Gun Company, 23rd Infantry. One platoon held Puruata. On Cape Torokina the enemy had built about eighteen log-and-sandbag pillboxes, each with two machine guns, mutually supporting, camouflaged, and arranged in depth. He had also emplaced a 75-mm. gun in an open-ended log-and-sand bunker to fire on landing craft nearing the beach.

Neither air bombardment nor naval gunfire had had any appreciable effect on these positions. Because air reconnaissance had shown that the enemy had built defense positions on Cape Torokina (a low, flat, sandy area covered with palm trees), it had been a target for naval bombardment. Two destroyers had fired at the cape from the south, but had done no damage. Exploding shells and bombs sent up smoke and dust that made observation difficult; some shells had burst prematurely in the palm trees. Poor gunnery was also a factor, for many shells were seen to hit the water.45

Thus when landing craft bearing the 3rd Marines neared the cape the 75-mm. gun and the machine guns opened fire. The men were forced to disembark under fire and to start fighting the moment they put foot to the ground. Casualties were lighter than might have been expected—78 men were killed and 104 wounded in the day’s action—but only after fierce fighting and much valor were the men of the 3rd Marines able to establish themselves ashore. The pillboxes were reduced by three-man fire teams: one BAR man and two riflemen with M1s, all three using grenades whenever possible. The gun position was taken by Sgt. Robert A. Owens of A Company, 3rd Marines, who rushed the position under cover of fire from four riflemen. He killed part of the Japanese crew and drove off the rest before he died of wounds received in his assault.46

By 1100 Cape Torokina was cleared. Most of its defenders were dead; the survivors retreated inland. Puruata Island was secured at about the same time, although some Japanese remained alive until the next day. Elsewhere the landing waves, though not opposed by the enemy, pushed inland slowly through dense jungle and a knee-deep swamp that ran two miles inland and backed most of the beach north and east of Cape Torokina. The swamp’s existence had not previously been suspected.

Air Attacks and Unloading

The Allied air forces of the South and Southwest Pacific Areas had performed mightily in their effort to neutralize the Japanese air bases at Rabaul, Bougainville, and the Shortlands, but they

3rd Marines landing on Cape Torokina

had not been able to neutralize Rabaul completely. In planning the invasion of Empress Augusta Bay, the South Pacific commanders were aware that the Japanese would probably counterattack from the air. General Twining had arranged for thirty-two New Georgia-based fighter planes of all types then in use in the South Pacific—Army Air Forces P-38s, New Zealand P-40s, and Marine F4U’s—to be overhead in the vicinity all day. These planes were vectored by a fighter director team aboard the destroyer Conway. Turning in an outstanding performance, they destroyed or drove off most of the planes that the Japanese sent against Wilkinson. But they could not keep them all away.

At 0718, as the last boats of the assault wave were leaving their transports, the destroyers’ radars picked up a flight of approaching enemy planes then fifty miles distant. The covering fighters kept most of the planes away, but a few, perhaps twelve, dive bombers broke through to attack the ships.

These bombers had come from Rabaul, where the enemy commanders were making haste to organize counterattacks. On 30 October Vice Adm. Sentaro Omori, commanding a heavy cruiser division, had brought a convoy into Simpson Harbor at Rabaul. Next morning a search plane reported an Allied convoy of three cruisers, ten destroyers, and thirty transports near Gatukai in the

New Georgia group. This was probably Merrill’s task force; it could not have been Wilkinson’s. On receiving this report Admiral Kusaka ordered the planes of his 11th Air Fleet to start attacks, and he and Koga, over the protests of the 8th Fleet commander, who warned of the dangers of sending surface ships south of New Britain, directed Omori to take his force and all the 8th Fleet ships out to attack. This Omori did, but he missed Merrill and returned to Rabaul on the morning of 1 November.

Then came the news of the landing at Empress Augusta Bay. General Hyakutake was still sure that the main Allied attack would be delivered against southern Bougainville, but General Imamura ordered him to destroy the forces that had landed. Imamura also arranged with Kusaka for a counterattacking force from the 17th Division, made up of the 2nd Battalion, 54th Infantry, and the 6th Company, 2nd Battalion, 53rd Infantry, to be transported to Empress Augusta Bay.47 It would be carried on 6 destroyer-transports and escorted by 2 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 6 destroyers, all under Omori.

Admirals Koga and Kusaka, just completing their preparations for Operation RO, also ordered out their planes. The weather had come to their assistance by halting the heavy raid General Kenney had planned for 1 November. Koga alerted the 12th Air Fleet for transfer from Japan to Rabaul. Kusaka sent out planes of his 11th Air Fleet. The carrier planes apparently did not take part on 1 November.

According to enemy accounts, Japanese planes delivered three separate attacks against Wilkinson on 1 November. The Japanese used a total of 16 dive bombers and 104 fighters, of which 19 were lost and 10 were damaged.48

When Wilkinson’s ships received warning at 0718, the transports and cargo ships weighed anchor and steamed for the open sea. They escaped harm, and the dive bombers were able to inflict only light damage to the destroyers. Two sailors were killed. The transports returned and resumed unloading at 0930, having lost two hours.

Another enemy attack at 1248 succeeded in breaking through the fighter cover. Warned again by radar, the transports, with the exception of the American Legion, which stuck on an uncharted shoal, fled. The Japanese attacked the moving ships instead of the Legion. No damage was done, but the ships lost two more hours of unloading time.49

The halts in unloading caused by air attacks, coupled with beach and terrain conditions that Admiral Halsey described as “worse than any we had previously encountered,” slowed the movement of supplies and equipment.50 Fully one third of the landing force—5,700 men in all—had been assigned to the shore party, but nature and the Japanese

LCVPs on the beach at Empress Augusta Bay damaged by the rough, driving surf

aircraft thwarted efforts to unload all the ships on D Day.

Even on quiet days the surf at Empress Augusta Bay was rough, and on 1 November a stiff breeze whipped it higher. The northernmost beaches were steep and narrow. The surf, and possibly the inexperience of some of the crews, took a heavy toll of landing craft. No less than sixty-four LCVPs and twenty-two LCMs broached on shore and were swamped by the driving surf. As surf conditions got worse, several beaches became completely unusable. Five ships were shifted to beaches farther south, with more delay and congestion at the southern beaches. It was during this move that the American Legion ran aground.

By 1730 the eight transports were empty and Wilkinson took them back to Guadalcanal. But the four cargo ships, which carried heavy guns and equipment, were still practically full. Vandegrift, who had had ample experience at Guadalcanal in being left stranded on a hostile shore while much of his equipment remained in the holds of departing ships, persuaded Wilkinson to allow the cargo ships to put out to sea for the night and return the next morning to unload.51 Most of the troops aboard went ashore in LCVPs before Commodore Reifsnider led the cargo ships out to sea. D Battery of the 3rd Defense Battalion, for example, its 90-mm. antiaircraft

guns, fire control equipment, and radars deep in the holds of the Alchiba, which had lost all its LCMs in the raging surf, went ashore as infantry and occupied a support position in the sector of the 9th Marines.

Except for the full holds of the cargo ships, D Day had been thoroughly successful. All the landing force, including General Turnage, Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Noble, corps deputy commander, Col. Gerald C. Thomas, the corps chief of staff, and several other officers, were ashore. General Vandegrift returned to Guadalcanal on the George Clymer, leaving Turnage in command at Cape Torokina. By the day’s end the division held a shallow beachhead from Torokina northward for about four thousand yards. Aside from unloading the cargo ships (a task that was expeditiously accomplished the next day), the main missions facing the amphibious and ground commanders and the troops were threefold: to bring in reinforcements; to organize a perimeter defense capable of beating off the inevitable Japanese counterattack; and to build the airfields that would put South Pacific fighter planes over Rabaul.