Chapter 14: Crossing the Straits

Plans and Preparations

By November 1943 CARTWHEEL was rolling along rapidly and smoothly. In just over five months Nassau Bay, Woodlark, Kiriwina, New Georgia, Vella Lavella, Salamaua, Nadzab, Lae, the Markham Valley, Finschhafen, the Treasuries, and Empress Augusta Bay had fallen to the Allies. At the newly won bases airfields were either in operation or under construction. Allied planes dominated the skies all the way to Rabaul, and Allied ships sailed the Solomon Sea and the Huon Gulf in comparative safety.

The capture of Finschhafen in Operation II was a step toward control of the straits between New Guinea and New Britain, a control that would help make possible the drive toward the Vogelkop Peninsula and the Philippines in 1944 and would be essential to any amphibious advance against Rabaul. The Southwest Pacific’s next move (Operation III of ELKTON III) was first planned by GHQ on the assumption that Rabaul would be captured. Looking eastward rather than westward from the Huon Peninsula, it aimed at the establishment of air forces at Cape Gloucester on western New Britain and of PT boat bases on the south coast of New Britain. (See Map 12.) These were to increase Allied control over Rabaul and over Kavieng and Manus in the Admiralties, and to provide bases on the north side of the straits to insure the safe passage of convoys.

Selecting Targets

GHQ’s orders for the operation, given the code name DEXTERITY, were published on 22 September.1 They directed General Krueger’s ALAMO Force, formerly the New Britain Force, supported by Allied Air and Allied Naval Forces, and by U.S. Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific, to seize Cape Gloucester by airborne and amphibious invasions and to neutralize the forward Japanese base at Gasmata on southern New Britain, to gain control over western New Britain as far east as the line Gasmata–Talasea, and to capture Vitu and Long Islands beyond the straits. General Blamey’s New Guinea Force would meanwhile continue its operations in the Huon Peninsula and the valleys. Gasmata was to be neutralized by troops who would land at nearby Lindenhafen Plantation, establish an emergency airfield, and advance on Gasmata in a shore-to-shore movement. The

plan directed Krueger to prepare to participate with South Pacific forces in the capture of Rabaul but this order was canceled on 10 November.2 Saidor was not specifically mentioned, although both MacArthur and Chamberlin had suggested it as a target earlier in the month.

D Day for the invasion of Cape Gloucester was initially set for 20 November but was postponed twice. The final date was 26 December.

This plan provoked a good deal of disagreement. The first to protest was General Kenney. With the decision to bypass Rabaul obviously in mind, he presented his objections to General MacArthur on 10 October. The original concept, he argued, called for an encircling ring of air bases, including Cape Gloucester, to be established around Rabaul in order to lay siege to it. But now that “faster action is contemplated” it would take too long to develop Gloucester into a useful air base. It would not be necessary to take either Gloucester or Lindenhafen, he told MacArthur: bases at Dobodura, Nadzab, and Kiriwina, plus the one at Finschhafen and perhaps a new one at Saidor, could provide support for invasions as far away as Kavieng.3 In speaking of faster action, Kenney apparently was referring to the long-range plan RENO III, which was then being prepared. It called for completion of the CARTWHEEL operations and then the move toward the Philippines, according to the following schedule: Hansa Bay, 1 February 1944; Kavieng (by the South Pacific), 1 March 1944; Admiralties, 1 March 1944; neutralization of Rabaul and perhaps, later, its occupation; Humboldt Bay and Arafura Sea, 1 June 1944; Geelvink Bay–Vogelkop Peninsula, 15 August–1 October, 1944; Halmahera, Amboina, the Palaus, 1 December 1944; Mindanao, 1 February 1945.

General Chamberlin, MacArthur’s G-3, observed that the air general’s plan differed from MacArthur’s present plans.4 There would be time, he asserted, to complete airdromes at Gloucester before undertaking the next operations. While he did not state that the Kavieng invasion could not be supported without Gloucester, he pointed out several advantages to be derived from the move to New Britain:

The Allies could better control Vitiaz Strait. (Here he reversed himself on the position he had taken on the point the month before.) Control from one side would be possible but it would be dangerous to leave the other side in Japanese hands.

Cape Gloucester would provide better support for the Kavieng and Admiralties attacks provided for in RENO III.

Cape Gloucester would provide better cover for convoys moving through Vitiaz Strait against the Admiralties. Even assuming the bypassing of Rabaul, Chamberlin concluded, a point on the south coast of New Britain would be needed to control Vitiaz Strait, neutralize

Gasmata, and provide an emergency airfield for planes attacking Rabaul.5

Admirals Carpender and Barbey also seem to have favored holding both sides of the straits, as did General Krueger. The admirals did not favor the seizure of Gasmata, because they felt it would mean a reckless exposure of ships to Rabaul-based aircraft.6

Kenney was informed that MacArthur’s plans, which encompassed the bypassing of Rabaul, required Cape Gloucester and Lindenhafen.7 But Kenney’s argument, coupled with the admirals’ and added to the facts that Gasmata was swampy and that the Japanese were known to be sending more troops there, did have some effect. One month later MacArthur canceled Gasmata operations and directed the ALAMO Force to seize Cape Gloucester and to establish control over adjacent islands and “minimum portions” of western New Britain with the purpose of protecting Cape Gloucester.8

The matter did not end there. It was finally settled by a conference at GHQ in Brisbane on 21 November attended by Kenney, Carpender, and Barbey. The naval commanders opposed Gasmata and are reported to have wanted a PT boat base elsewhere on New Britain’s south coast. Therefore Arawe, the name of a peninsula, a harbor, and an island west of Gasmata which had been listed as an objective in ELKTON III, was substituted for Gasmata with the intention of using it as a PT base and in the hope of diverting the enemy’s attention from Cape Gloucester. Arawe had a fair anchorage and there were only a few Japanese in the area. General Kenney assured his fellow commanders that he could give better air cover to Arawe than to Gasmata. Cape Gloucester remained the main objective.9 As the same ships had to be used for both invasions, the dates were staggered.

Setting Dates

The first dates selected, 14 November for Lindenhafen and 20 November for Cape Gloucester, proved impossible to meet and had to be postponed. The process of postponement and selection of new dates clearly illustrates some of the controlling factors in Southwest Pacific amphibious operations.

By 26 October Kenney, Sutherland, and Chamberlin realized that enough air cover would not be available to meet the first target dates. The Finschhafen airstrip would not be completed until about 5 December. Construction of the Lae–Nadzab road had fallen behind

schedule and it could not take heavy vehicles and machinery before 1 December; consequently the three airstrips in the lower Markham Valley would not be in shape to maintain air operations before 15 December. The VII Amphibious Force, which would carry the assault troops in DEXTERITY, could not be released from its responsibilities for supplying Lae and Finschhafen for some time. It was estimated that from 135,000 to 150,000 more tons of supplies would have to be sent to Lae, 60,000 to 70,000 more to Finschhafen, in order to support air operations. Shipments to Nadzab were slowed by the lack of enough men and docks at Lae, and movement of supplies to Finschhafen was slowed by the fact that until the airfield was finished the naval commanders would not risk sending heavy ships there.

Southwest Pacific invasions usually took place during the dark of the moon to help hide ships from nocturnal raiding planes. The last-quarter moon would come on 19 November, the first-quarter moon on 4 December. If the attack could not be mounted before 4 December it would have to be put off until after 19 December, the date of the next last quarter moon. But this was the period of the northwest monsoon, and the longer the Southwest Pacific waited for ideal moon conditions the rougher would be the surf at Cape Gloucester.

Chamberlin therefore recommended that DEXTERITY be put off until the earliest possible date in December, that the VII Amphibious Force keep on supplying Lae and Finschhafen a while longer, and that two engineer aviation battalions that were scheduled for Cape Gloucester be set to work at Lae and Finschhafen for the time being.10 MacArthur, accepting these recommendations, announced that he would delay the attack about fifteen days, and that the VII Amphibious Force would supply Lae and Finschhafen until about 20 November.11

This decision provoked the quiet, undramatic General Krueger to protest that the resulting schedule would be too tight. MacArthur’s order meant that Gloucester would have to be invaded on 4 December. The subsidiary operation would have to be accomplished on 28 November. Since there was no reserve shipping, any losses on 28 November would hamper the main landing. Further, the VII Amphibious Force, once relieved at Lae and Finschhafen, could not be expected to get to Milne Bay until 26 or 27 November. Thus there would hardly be time for rehearsals. Krueger, asking for more ships or for more time, suggested that the first operation take place on 2 December, Gloucester on the 26th.12 MacArthur agreed to another postponement and eventually set Z Day for Arawe at 15 December, D Day for Gloucester at 26 December.13

ALAMO Force Plans

Originally assigned to ALAMO Force for DEXTERITY were the 1st Marine Division; the 32nd Division; the 632nd Tank

Destroyer Battalion; the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, for Cape Gloucester only; and a number of quartermaster, medical, signal, engineer, and antiaircraft units. The 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions, then in Australia but soon to move to New Guinea, and the 503rd Parachute Infantry (which would be committed at Cape Gloucester) constituted GHQ’s reserve. The 1st Marine and 32nd Divisions moved from Australia to the forward area shortly before the invasions.14

As usual, MacArthur gave Krueger responsibility for coordinating the plans of supporting air and naval forces with those of the ALAMO Force. In contrast with the system of unity of command over all elements of an invasion force that prevailed in the South Pacific, the commander in chief specifically directed that Allied Air and Naval Forces would operate under GHQ through their respective commanders and exempted them from control by ALAMO or New Guinea Forces. However, if the Japanese attacked in any area the senior local commander was to control all Southwest Pacific forces in the threatened area.

General Krueger and the ALAMO Force staff had been planning for DEXTERITY since August.15 In the beginning ALAMO headquarters was at Milne Bay, where it had been established at the opening of the CARTWHEEL offensives. On 21 October Krueger moved it to Goodenough Island.16

During the planning period for DEXTERITY the Japanese were strengthening their garrisons in western New Britain in accordance with the orders issued by Imamura in September. Thus Allied estimates of Japanese strength in the area rose from 500 before September to 2,500 on the 26th. In December Krueger placed enemy strength at between 5,668 and 9,344, with the strongest concentration at Cape Gloucester. The 1st Marine Division, apparently deriving its information from the same sources as ALAMO Force, arrived at a higher figure—between 8,400 and 12,076.17

Little was known about the terrain of western New Britain, and Krueger ordered ground reconnaissance in addition to the extensive air photography that was undertaken by Allied Air Forces. Because PT boats were not allowed to operate off New Britain’s north coast no patrols were able to examine Borgen Bay, where the main Cape Gloucester landings were to take place. Marine patrols landed from PT boats and reconnoitered the area south of Cape Gloucester from 24 September through

21 December in a series of patrols. A group of ALAMO Scouts, an informal reconnaissance organization operating directly under General Krueger, reconnoitered Gasmata from 6 through 27 October. On the night of 9-10 December one American officer and five natives disembarked from a PT boat east of Arawe, scouted the area, and concluded there were only a few Japanese present.18

More information was obtained from aerial photography. Missions were flown almost daily so that ALAMO and subordinate headquarters could be kept informed of gun positions, beach defenses, bridges, and trails. The VII Amphibious Force used air photos as the basis for its hydrographic charts, and the 1st Marine Division used them to pick the landing beaches.19

Krueger’s first tactical plans, prepared in accordance with GHQ’s orders, had called for the heavily reinforced 126th Regimental Combat Team, under Brig. Gen. Clarence A. Martin, of the 32nd Division, to take Gasmata. Cape Gloucester was to have been captured by the BACKHANDER Task Force under Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, commander of the 1st Marine Division. The assault force was to have consisted of one regimental combat and one battalion landing team of Rupertus’ division, the 503rd Parachute Infantry Regiment, and the 12th Marine Defense Battalion. The marines were to have delivered an amphibious assault, coupled with a parachute jump by the 503rd.20 But this whole plan was drastically revised.

When on 22 November General MacArthur substituted Arawe for Gasmata, Krueger decided to use a smaller force than the 126th. He correctly believed Arawe to be weakly defended. For Arawe he formed the DIRECTOR Task Force under Brig. Gen. Julian W. Cunningham, who as a colonel had led the invasion of Woodlark. Its assault units included Col. Alexander M. Miller’s two squadron 112th Cavalry; the 148th Field Artillery Battalion; the 59th Engineer Company; Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 236th Antiaircraft Artillery (Searchlight) Battalion; and C and D Batteries, 470th Antiaircraft Artillery (Automatic Weapons) Battalion. In reserve was the 2nd Battalion, 158th Infantry. Supporting garrison units, to be moved to Arawe after 15 December (Z Day), consisted of several engineer, medical, ordnance, and other service detachments. All these units had been attached to the ALAMO Force for the invasion of the Trobriands in June, and were still occupying the islands.

The concept of the Cape Gloucester invasion was changed also; the parachute jump was canceled and the 503rd removed from the troop list. Several factors contributed to this change. General Krueger’s headquarters had never liked the idea. General Rupertus, too, had

opposed the parachute jump from the start. He pointed out that bad weather, which had prevented several air attacks against Rabaul, might interfere with the parachute jump and thus deprive him of a substantial part of his assault force.21 General Kenney’s headquarters, in December, added its opposition. First, although ALAMO Force orders did not specify exactly how the jump was to be accomplished, it was understood at Allied Air Forces headquarters that a piecemeal and therefore dangerous drop was planned. Second, it seemed that the jump would be under way about the time that Japanese planes might be expected to turn up. Asking if the jump was necessary, Kenney’s operations officer stated emphatically that the air commander wanted “no part” of it.22

General Rupertus’ headquarters had disliked the whole scheme of maneuver as prescribed by ALAMO headquarters, as well as the parachute jump. ALAMO’s first plans called for simultaneous, separated landings by two small forces, which were to converge on the airfield at Cape Gloucester in conjunction with the 503rd’s jump. But the 1st Marine Division, which had had ample experience with jungle warfare on Guadalcanal, felt that this plan was unsound because the rough and scarcely known terrain could easily delay either or both of the marching forces. Also, the Japanese could be expected to outnumber any one of the three landing forces. When Generals MacArthur and Krueger visited 1st Marine Division headquarters at Goodenough on 14 December, Col. Edwin A. Pollock, divisional operations officer, frankly expressed the marines’ objections to the parachute jump and the scheme of maneuver.

Krueger had included the parachute jump because MacArthur’s headquarters had assigned the 503rd Parachute Infantry to the operation, and he considered himself under orders to make his plans fit the forces assigned.23 MacArthur, Krueger, and Kenney now discussed the matter further. It developed that Dobodura would not support the mounting of the 503rd as well as all the planned bomber operations. To use the 503rd would require moving one heavy bomber group from Dobodura to Port Moresby, and bad weather over the Owen Stanleys might keep the bomber group out of action. The jump was canceled.

ALAMO Force further revised its tactical plans for taking Cape Gloucester to meet the 1st Marine Division’s objections. Final plans called for one regimental combat team to land on two beaches on the north coast of New Britain between Silimati Point in Borgen Bay and the airfield at Cape Gloucester, while a second (less a battalion landing team) landed immediately behind, passed through the first, and attacked toward Cape Gloucester to the airfields. One battalion landing team was to land near Tauali on the west coast of New Britain to block the coastal trail

and prevent reinforcement of the airdrome area from the south or retreat of the airdrome garrison to the south.

The assault units of Rupertus’ BACKHANDER Task Force were two regimental combat teams of the 1st Marine Division; the 12th Marine Defense Battalion less its 155-mm. gun group; detachments, including LCMs and LCVPs, of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade; and the 913th Engineer Aviation Battalion. The reserve, supporting, and garrison units included the remainder of the 1st Marine Division, the 155-mm. gun group of the 12th Defense Battalion, and a large number of engineer, medical, quartermaster, and malaria control units, chiefly of the Army.

The Arawe (DIRECTOR) forces were to mount the invasion at Goodenough, the Gloucester (BACKHANDER) forces through Oro Bay, Goodenough, and Milne Bay. In ALAMO reserve was the 32nd Division.24

Logistical plans called for the U.S. Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific Area, now commanded by Maj. Gen. James L. Frink, to establish and maintain at New Guinea bases sixty days’ supply of all types except chemical and Air Force.25 Thirty days’ of the last two classes were to be maintained. Frink’s command was to make building materials for ports and air bases available to the ALAMO Force by Z plus 5 and D plus 5, and was to furnish naval forces with supplies common to the Army and Navy pending establishment of the naval supply system, or in emergencies. The VII Amphibious Force would of course transport supplies to the beachheads until they were secured and Frink was ready to take over. Allied Air Forces was to transport supplies to the ground troops in emergencies.

All units in the task forces were to be stripped of equipment not needed for their combat missions. They would carry to Arawe and Cape Gloucester in the assault echelons thirty days’ supply and three units of fire, which would be built up by succeeding shipments to sixty days’ supply and six units of fire (ten for antiaircraft). Oro Bay was the main supply base, Milne Bay the secondary.26 Cape Cretin, near Finschhafen on the southeast corner of the Huon Peninsula, which the ALAMO Force was preparing as a supply point and staging base, was to serve for resupply.

Krueger, on receiving data on Allied Air Forces’ requirements, directed the BACKHANDER Task Force to build a small strip at Cape Gloucester for air supply at once, a 100-by-5,000-foot runway by D plus 10; a second 100-by-5,000-foot runway, capable of expansion to 6,000 feet, by D plus 30; and also overruns, parallel taxiways, roads, and airdrome facilities.27

The Enemy

When the Allies landed on Cape Gloucester General Imamura could not have been surprised. He had anticipated such a move some time before. In October the 8th Area Army staff had concluded that two lines of action were open to the Allies: capture of the New Britain side of the straits, invasion of Bougainville, and a direct assault upon Rabaul in February or March 1944; or the slower process of isolating Rabaul by seizing the Admiralties and Kavieng.28 Considering the first course the more likely, he decided to send more troops to western New Britain in addition to those he had sent under General Matsuda in September. He would have liked to reinforce the Admiralties and Kavieng but felt he could not spare any more troops from the defenses of Rabaul.

Imamura therefore ordered the 17th Division, less the battalions dispatched to Bougainville, to western New Britain. Reaching Rabaul from China between 4 October and 12 November, the 17th went by echelons to its new posts by naval vessel and small boat. The movement began in October but was still under way in mid-December.

The 17th Division commander was given operational control of the units already there, chiefly General Matsuda’s 65th Brigade and 4th Shipping Group at Cape Gloucester and 2nd Battalion, 228th Infantry, and two naval guard companies at Gasmata.29 Final plans organized the entire force into three commands. The first and largest, under Matsuda, consisted of the 65th Brigade (principally the 141st Infantry), the 4th Shipping Group, and a large number of field artillery, antiaircraft, automatic weapons, engineer, and communications units. Matsuda was charged with defense of the area from the emergency airstrip and barge staging point near Tuluvu around the coast to Cape Bushing on the south. Under Matsuda Maj. Masamitsu Komori, with most of the 1st Battalion, 81st Infantry, one company of the 54th Infantry, and engineers plus detachments, was assigned responsibility for defense of Arawe. Col. Shuhei Hirashima, commanding the 54th Infantry, less the 2nd Battalion, the 2nd Battalion, 228th Infantry, the 2nd Battalion, 23rd Field Artillery Regiment, and the naval guard companies, was to hold the airfield at Gasmata.30 The 17th Division established its command post at Gavuvu, east of the Willaumez Peninsula and a long distance from the scene of operations.

The air strength available to the Japanese for the forthcoming fight had been reduced, not only by the Allied air attacks against Rabaul, but also by orders from Tokyo. The 2nd Area Army was established in the Netherlands Indies on 1 December 1943, and the boundary between it and Imamura’s 8th Area Army was set at longitude 140° east. But the

B-25s over Wewak. Three damaged enemy planes are visible on the ground

7th Air Division was transferred out of the 4th Air Army and assigned to the 2nd Area Army.31 This transfer seriously reduced Imamura’s forces, but so far the 7th Air Division had not operated effectively. Its most outstanding exploit had been the loss of planes on the ground at Wewak.

Air Operations

With the new fields in the Markham Valley and at Finschhafen in operation, Allied Air Forces’ aerial preparations for DEXTERITY were the most extensive yet seen in the Southwest Pacific.32 They included, besides daily P-38 photographic missions, long-range search missions by PBYs of the Seventh Fleet’s Patrol Wing 10, RAAF Catalinas, and Fifth Air Force B-24s, and bombing and strafing.

Air attacks, which had been under way against New Britain since October, began on a large scale in late November. Cape Gloucester and Gasmata were the main targets. Arawe was avoided until 14 December in order to keep from warning the Japanese. During December Kenney’s planes attacked Gasmata or Gloucester, or both, nearly every day and sometimes twice a day. As General Whitehead said, Cape Gloucester was “tailor made” for air operations. The target area lay along the beach and was long and narrow.33 During December Kenney’s planes flew 1,845 sorties over Gloucester, dropped 3,926 tons of bombs, and fired 2,095,488 rounds of machine gun ammunition. The chief targets were Tuluvu airfield, antiaircraft guns, supply dumps, and the barge staging points. The airfield was knocked out of action early in the operation and stayed that way.

Preliminaries

Arawe

The 112th Cavalry, shipped aboard LSTs, reached Goodenough Island from Woodlark on 1 and 2 December.34 There General Cunningham gave Colonel Miller detailed orders for the landing of his regiment at Arawe on 15 December.

Arawe, which before the war had been a regular port of call for vessels of the

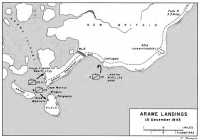

Map 17: Arawe Landings, 15 December 1943

Burns-Philp South Seas Company, had a harbor suitable for large vessels. There were several beaches that landing craft could use, of which the two best were House Fireman on the west coast of the boot-shaped Arawe peninsula and the village of Umtingalu on the mainland, seventeen hundred yards east of the peninsula’s base. The rest of the coast line consisted of stone cliffs about two hundred feet high, interspersed with low ground that was covered by mangrove swamp. Reefs fringed all the beaches, and it was clear that LCVPs could not get to the shore until detailed reconnaissance for passages was made. (Map 17) Therefore General Krueger arranged with Rupertus for one company of the 1st Marine Amphibian Tractor Battalion to be attached to the DIRECTOR Task Force to take the assault waves ashore. Krueger also attached part of the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, with 17 LCVPs, 9 LCMs, 2 rocket-firing

DUKWs, and 1 repair and salvage boat, to Task Force 76 for the landings.35

The 112th Cavalry stayed on Goodenough for ten days. During this period the troops received additional practice and training with all their weapons, including two new ones—the flame thrower and the 2.36-inch rocket launcher (bazooka). Before shoving off all men were informed of the general plan of attack and given aerial photographs and maps to study. The training period was topped by two landings. The first was intended to familiarize the troops with loading and unloading landing craft. The second was conducted under assumed combat conditions and involved the coordinated landing of all elements at proper intervals and their tactical deployment ashore. General Cunningham forcefully pointed out several major deficiencies. Units were not always under control of their commanders, intervals between landing waves were too long, and not all junior officers and noncommissioned officers knew their duties.

With Generals MacArthur and Krueger looking on, the DIRECTOR Task Force boarded the LSD Carter Hall, HMAS Westralia, and the APDs Sands and Humphreys on the afternoon of 13 December.36 At midnight the ships departed for Buna, where General Cunningham left the Carter Hall and joined Admiral Barbey aboard the destroyer Conyngham, the flagship. The voyage to the target, which included a feint toward Finschhafen, was uneventful except for seas rough enough to cause the passenger troops some discomfort. Admiral Crutchley’s cruisers and destroyers covered the move to the east while PT boats patrolled the straits to the westward.

The Landings

Barbey’s convoy sighted the south coast of New Britain shortly after 0300, 15 December, and the troop ships soon hove to in the transport area about five miles east of Arawe.37 By 0450 the Carter Hall had launched thirty-nine loaded amphibian tractors bearing the assault waves and the two rocket DUKWs out of her well deck.

Dawn was still one hour away when 150 men of A Troop, 112th, who had been aboard the APD Sands, started for the beach at Umtingalu in fifteen rubber boats. They had been ordered to make a surprise landing in darkness at H minus 1 hour and block the coastal trail that was the Japanese escape and reinforcement route to the east. About 0525, when the boats were nearing shore and in the moonlight were probably visible from the shore, they came under fire from machine guns, rifles, and a 25mm. dual purpose gun, which promptly sank all but three of the rubber boats.

The fire continued while the troops floundered in the water divesting themselves of their light combat packs and outer clothing. The destroyer Shaw then opened fire and quickly silenced the enemy.38 Small boats picked up the survivors of A Troop, who later landed without arms and almost naked at House Fireman Beach. Twelve men were killed, four missing, and seventeen wounded in this repulse.

B Troop fared better. Ordered to land at H minus 1 hour on the islet of Pilelo, across Pilelo passage from the peninsula, its men were to take the Japanese by surprise and silence a radio station that was reported at the village of Paligmete. They left the APD Humphreys on fifteen rubber boats at the same time that A Troop left the Sands.

B Troop had planned to surprise the enemy by landing at Paligmete village, but when the Japanese started firing on A Troop it was obvious that surprise was lost. B Troop landed at Wabmete, on the west of Pilelo, instead. Once ashore the cavalrymen started on foot for Winguru.

The leading platoon reached Winguru at 0615 and met fire from Japanese in two caves on the rising ground south of the village. Leaving one squad to contain these Japanese, B Troop pushed on to Paligmete, found neither Japanese nor radio, and returned to Winguru to mop up. Bazooka fire closed one cave but the other was faced with logs which proved impervious to rockets and machine guns. Finally a flame thrower team, covered by machine gun fire, edged to within fifteen yards of the cave and let loose a blast of flame. B Troop then moved in, tossed grenades, and the action was over. One American soldier had been killed. Seven dead enemy were found. The action ended about 1130.

Meanwhile the main landing at House Fireman Beach had been accomplished successfully if not flawlessly. The assault waves came from Lt. Col. Clyde E. Grant’s 2nd Squadron, 112th Cavalry, organized into five landing waves: ten LVT(A)(2)s (Buffaloes), carrying E and F Troops, in the first; eight LVT(1)s (Alligators) each in the second, third, and fourth waves; and five Alligators in the fifth. The waves were scheduled to land at five-minute intervals. H Hour was set for 0630, after the conclusion of the air and naval bombardments. One and a half hours were allowed for the amphibian tractors to proceed from the ships to the beach, a move which would take place in poor light. Since dawn came at 0624 and sunrise at 0646, the landing itself would take place in daylight.

But someone along the line had become confused. Once boated, the first wave started directly for the shore in the dark. Brig. Gen. William F. Heavey, commanding the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, who had come along as an observer aboard the landing wave control craft, SC 742, saw the boats dimly about 0500. When radio communication with the flagship unaccountably failed, the

subchaser’s captain and Heavey headed off the errant amphibian tractors. There was much confusion and milling about in the darkness, and it was 0600 or later before the tractors regained their formation.

Destroyers bombarded House Fireman Beach with 1,800 5-inch rounds from 0610 to 0625, whereupon B-25s took over. Three squadrons had been assigned to air alert over Arawe under control of an air liaison party aboard the Conyngham, and the first of these bombed and strafed the peninsula and the beach. Under ideal conditions the interval between the cessation or lifting of support bombardment and the landing of troops is only long enough to prevent the troops from being hit by their own support fire, but the lead wave of tractors had been slowed by the confusion and by a stiff current in Pilelo passage. It did not land until after 0700. On the way in, the wave met machine gun fire that was quickly silenced by 4.5-inch rockets from the control craft and the two rocket DUKWs on the flanks. Otherwise there was no opposition.

This was fortunate, because the succeeding waves in the Alligators, which were slower craft than the Buffaloes, had not been able to keep up. Twenty-five minutes elapsed before the second wave landed, ample time for a resolute defending force to have inflicted heavy casualties on the first wave. When another fifteen minutes had passed the last three waves came ashore practically together.39

The 2nd Squadron, once landed, reorganized, sent patrols to the toe of the peninsula, and pushed northwestward toward the base against slight opposition from scattered riflemen and rear guards. E Troop located twenty or more Japanese in caves in the cliff on the east side of the peninsula, killed several, and passed on. When others came out of their caves to snipe and harass, the 112th Cavalry Headquarters L Troop sent out a patrol which disposed of them.

Only two companies of Japanese soldiers had been in the area, and when the 2nd Squadron came ashore they retreated eastward. Major Komori and his force had not yet reached Arawe.

Meanwhile passages through the reefs had been found. The reserve 1st Squadron, under Maj. Harry E. Werner, had debarked from the Westralia while the Carter Hall was launching the tractors. Werner’s squadron came ashore about 0800 in the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade’s 2 LCMs and 17 LCVPs. An hour later Barbey’s second echelon, 5 LCTs carrying 150 tons of gear and 50 men per LCT, and 7 LCMs carrying 25 tons of gear per LCM, arrived from Cape Cretin and began unloading.

Operations at the beach were not smooth. The detachments forming the shore party had never worked together before, and although the beach was a good one it soon became congested. There was room for but two LCTs at one time; so unloading of beaching craft continued all day.

For DEXTERITY the admirals had won the air cover argument, and planes were assigned as combat air patrol over the

ships instead of standing by on ground alert. The first fighter cover, in the form of 8 P-38s, took station overhead at 0715. This cover was subsequently increased and was maintained all day but it was not able to prevent an air attack at 0900. The 11th Air Fleet at Rabaul had just received more planes and now totaled 50 bombers and 100 fighters. Both Kusaka’s fleet and the 6th Air Division sent out planes against Arawe. One flight of these, reported as consisting of 20 or 30 planes, eluded the P-38s and delivered the attack at 0900. The Westralia and Carter Hall, unloaded before dawn, had departed at 0500 to avoid air attack. The rest of Task Force 76, with the exception of craft actually at the beach and the flagship Conyngham, which remained to direct operations, sought the cover of clouds and rain squalls. The Japanese bombed and strafed the beached LCTs, the Conyngham, and the troops for about five minutes, scored no hits, and left with P-38s in pursuit.

By midafternoon the DIRECTOR Task Force controlled the entire peninsula. The 2nd Squadron had reached the base, and now began establishing a main line of resistance there. Over sixteen hundred men, five hundred from the attached units and the rest from the two squadrons of the 112th Cavalry, were ashore.

Operations, 16 December 1943-10 February 1944

During the next few days LCTs from Cape Cretin and APDs from Goodenough brought in heavy weapons, supplies, and more troops. There was no ground contact with the Japanese at Arawe, but in the air the enemy reacted with violence. Between 15 and 27 December naval planes delivered seven attacks against Arawe and against the 1st Marine Division at Cape Gloucester, and in about the same period the 6th Air Division attacked four times. LCTs at Arawe on 16 December suffered almost continuous air attack. Resupply convoys lost one coastal transport sunk and another damaged, plus one minesweeper and six LSTs damaged. Although General Cunningham’s force had no 90-mm. antiaircraft guns to keep bombing planes away, damage ashore was fortunately light. Cunningham expressed his urgent need for the 90-mm.’s, but none was available for Arawe. By late December, however, the 11th Air Fleet and the 6th Air Division had lost so many planes to Allied fighters over New Britain, to Southwest Pacific attacks against Wewak, and to the South Pacific’s raids on Rabaul that they were forced to stop daylight bombardment and confine their activities to the defense of Rabaul and Wewak. When Imamura asked Tokyo for more planes Imperial Headquarters responded by sending the 8th Air Brigade to Hollandia under the 2nd Area Army.

The Japanese had not yet given up at Arawe. When the 17th Division commander received word of Cunningham’s landing he ordered Major Komori, who was then proceeding by boat and overland march to Arawe from Rabaul, to make haste. He also ordered the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry, to move from Cape Bushing to Arawe and come under Komori’s command. Komori was

then to destroy the DIRECTOR Task Force.

The Americans soon became aware of the approaching Japanese. On 18 December two Japanese armed barges attacked a 112th Cavalry patrol on board two of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade’s LCVPs (which had remained under Cunningham at Arawe). The Japanese scored hits; the patrol abandoned the LCVPs and made its way east to Arawe on foot. Komori’s force reached the Pulie River east of Arawe on 20 December, advanced west, and on Christmas Day forced the 112th to abandon its observation posts and outposts east of Arawe.

Cunningham, correctly concluding that the Japanese were converging against him from two directions but erroneously concluding that Komori’s command was but the advance guard of a stronger force from Gasmata, asked Krueger for reinforcements. The ALAMO commander hastily dispatched G Company, 158th Infantry, by PT boat.

Komori, with the 1st Battalion, 81st Infantry, reached the area northwest of the main line of resistance on 26 December. Like the Americans, he had difficulty in getting any exact information on positions in the featureless, jungled terrain at the peninsula’s base. Several of his night probing attacks were repulsed by mortar fire, as were daytime attacks on 28 and 29 December. The second of these took the lives of most of his men, but the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry, arrived in the late afternoon of 29 December. Several small attacks in early January 1944 by the 112th were beaten off, but the cavalrymen established the fact that the Japanese were digging in about six hundred yards beyond their own perimeter. Komori had resolved to defend the prewar airstrip on the mainland east of the peninsula, which in any case the Allies did not want.40

On 6 January Cunningham reported to Krueger the existence of the Japanese positions. Cunningham’s forces now totaled almost 4,750 men and his short front line—seven hundred yards—was a strong position with fields of fire cut, barbed wire emplaced, and artillery and mortar data computed.41 The enemy positions he faced consisted largely of shallow trenches and foxholes and were practically invisible in the dense underbrush. There were only about 100 Japanese and half-a-dozen machine guns there, but lack of visibility and the fact that the Japanese moved their guns frequently made them almost impossible for artillery and mortars to hit. An assault would be further complicated by the fact that in the area there were no clearly defined terrain features which could serve to guide an attack and help it maintain its direction. Cunningham asked for tanks and more troops, and repeated his request for 90-mm. antiaircraft guns.

Krueger agreed that attacks by riflemen alone against Komori would result in a waste of lives and agreed to send

Alligator returning to beach on Arawe for more supplies, 18 December 1943

tanks as well as more troops. F Company, 158th Infantry, and B Company, 1st Tank Battalion, 1st Marine Division, reached Arawe from Cape Cretin on 10 and 12 January.

On the morning of 16 January attack and medium bombers struck at the Japanese positions, artillery and mortars shelled them, and the Marine light tanks, two companies of the 158th Infantry, and C Troop of the 112th Cavalry attacked. The tanks led, with infantrymen and cavalrymen following each tank. Direct communication between tanks and foot troops was successfully attained by a device which the tank company improvised; it installed an EE8 field telephone at the rear of each machine. The attack went well and carried forward for fifteen hundred yards. Next day B Troop and one tank platoon mopped up remaining pockets of resistance.

Thereafter Arawe was quiet. Casualties for all units in the DIRECTOR Task Force totaled 118 dead, 352 wounded, and 4 missing. Komori had actually withdrawn to defend the airstrip, and remained there until ordered to retreat to the east in February.

Ironically enough, no PT base was ever built at Arawe. Actually the final plans had never included any provision for one. Lt. Comdr. Morton C. Mumma, commanding Southwest Pacific PT’s, successfully insisted that he did not want and did not need a PT base there to patrol the straits or to attack Japanese barges, which seldom used the south coast anyway. Arawe never became an air base either. The only airstrip ever used was one for artillery liaison planes that engineers hastily cleared on 13 January.

Cape Gloucester

Meanwhile the main event at Cape Gloucester had gotten under way. Elements of the 1st Marine Division scheduled for the main assault landings east of Cape Gloucester conducted final rehearsals at Cape Sudest on 21 December.42

The heavily reinforced 7th Marines boarded ship at Oro Bay three days later and departed at 0600 on Christmas morning. En route ships carrying the reinforced 1st Marines (less one battalion landing team) from Cape Cretin joined up. The convoy then made its way peacefully through Vitiaz Strait, sailed between Rooke and Sakar Islands, and approached Cape Gloucester. The 2nd Battalion Landing Team, 1st Marines, embarked at Cape Cretin and steamed through Dampier Strait for Tauali.43 Admiral Crutchley’s Task Force 74—the American cruisers Phoenix and Nashville, HMAS Australia and HMAS Shropshire, and eight destroyers—escorted Task Force 76 while PT boats patrolled the northern and western entrances to the straits.

The Landings

In the dim light of 0600 on 26 December Crutchley’s ships opened their supporting bombardment on the landing beaches east of Cape Gloucester, a bombardment that continued for ninety minutes. Two new LCIs equipped with 4.5-inch rockets took station on the flanks as guide and fire support craft. After threading their way through a difficult channel, APDs, in the lead, lowered landing craft full of troops while behind them LCIs and LSTs awaited their turns at the beaches. (Map 17)

The 1st Air Task Force of the Fifth Air Force had prepared extensive plans for all-day air cover and support that involved a total of five fighter squadrons and fourteen attack, medium, and heavy bomber squadrons. The first support bombers arrived from Dobodura about 0700 and B-24s, B-25s, and A-20s bombed and strafed the beaches and the airdrome. B-25s dropped smoke bombs on Target Hill, the 450-foot ridge just west of Silimati Point that gave clear observation of the beaches and airfields. A-20s strafed the landing beaches until the leading wave of landing craft was five hundred yards from shore. At that time the naval gunfire was moved inland and to the flanks.

An errant breeze blew so much smoke from Target Hill that some of the leading waves of landing craft carrying the 7th Marines could not easily identify the beaches. There was no opposition at the proper beaches, where most of two battalions of the 7th landed, but a detachment which wandered three hundred yards too far west had a brisk fire fight on shore.

The 7th Marines found that the landing beaches were good but very shallow. And as the assault waves crossed the beaches they were brought up sharply by jungle so dense they had to start hacking to get inland. Immediately behind the beach was a narrow shelf of relatively

Early morning bombardment of landing beaches east of Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943

dry ground. Behind the shelf was a swamp which made anything like rapid movement or maneuver completely impossible. Men floundered through the mud, slipping into sinkholes up to their waists and even their armpits. And in the swamp giant trees, rotted by water and weakened by bombs and shells, toppled over easily. The first marine fatality on Cape Gloucester was caused by a falling tree.

The narrow beach and the swampy jungle behind it caused a good deal of congestion, especially when the LSTs began discharging their cargo. As expected, Japanese planes from Rabaul attacked the ships and the beach during the day, although their first attacks were directed against Arawe in the belief that the convoy had been intended as reinforcement for Cunningham. They sank one destroyer, seriously damaged two more, and scored hits on two others, as well as on two LSTs.

By the day’s end the 7th Marines held the beachhead area. The artillery battalions of the 11th Marines had landed and emplaced their howitzers. The 1st Marines had come ashore, passed through the 7th, and begun the advance west toward the airdrome. The regiment first attempted to advance with battalions echeloned to the left rear, but the swamp forced movement in a long column with a narrow front along the coastal trail.

Also on 26 December the reinforced

Map 18: Cape Gloucester Landings, 26-29 December 1943

2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, landed successfully at Tauali and D Company, 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, 2nd Engineer Special Brigade, landed on Long Island to prepare a radar station there.

The first night ashore at Gloucester was miserable, and it was the first of many more that were just as bad. Drenching rains characteristic of the northwest monsoon poured down in torrents; more trees fell. The Japanese in the airdrome area, estimating that only 2,500 men had come ashore, counterattacked the 7th Marines, but they failed, as did a heterogeneous group that later struck at the Tauali positions.

Capture of the Airfield

The 1st Marines started westward along the coastal trail toward the cape and the airfield at 0730, 27 December. The swamp still forced the regiment to advance in column of battalions, with the rear battalion echeloned as much as possible to the left rear. Each battalion marched in column of companies and sent small patrols into the swamp to protect its flanks. General Sherman tanks of A Company, 1st Tank Battalion, supported. By 1615, when it dug in for the night, the regiment had gained three miles, and had become aware of the existence of a large Japanese block about a thousand yards east of the airfield.

7th Marines landing on narrow beach, Cape Gloucester, 26 December 1943

Next day the 1st made deliberate preparations before attacking the block. The absence of Japanese resistance the day before had led to the conclusion that the enemy was concentrating his forces inside the block. The 1st Marines waited during the morning for more tanks to make their way up the trail, which by now was a veritable morass, and for artillery and aircraft to shell and bomb the block. The infantry and the tanks moved to the attack about noon and shortly ran into the block. This position was a strong point which originally had faced the sea for defense of the beach but which served alternately as a trail block. It consisted of camouflaged bunkers with many antitank and 75-mm. weapons. There was scarcely room for tanks and infantry to maneuver, but by the end of the afternoon the 1st Marines had reduced the block.

General Rupertus had been asking for his reserve, the reinforced 5th Marines, which had remained under Krueger’s control, and on the 28th Krueger released the regiment. Rupertus then decided to hold up the advance on the airfield until the 5th arrived. It came on 29 December, but confusion over orders caused part of the 5th to land just behind the 1st, the rest at the D-Day beaches. When the 5th had been reassembled the drive began again. The 1st Marines continued the coastal advance and, because the swampland on the left had given way to jungle, the 5th was able to make a wide southwesterly sweep. There was almost no resistance. By the day’s end most of the airdrome was in Allied hands and

the major objective of the campaign had been achieved.

The Japanese Withdrawal

This phase of the operation had gone rapidly and at the cost of comparatively few casualties. But the absence of Japanese opposition made it clear that a large body of the enemy must be elsewhere in the vicinity. Thus in the first two weeks of 1944 the 7th Marines and the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, under Brig. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, the assistant division commander, attacked southward to clear Borgen Bay. Here waged the bitterest fighting of the campaign as the 141st Infantry struggled to keep possession of the high ground.

Thereafter there was little combat. The marines patroled extensively in search of the enemy, who proved to be elusive. B Company, 1st Marines, landed on Rooke Island on 12 February but found it had been evacuated. Eventually elements of Rupertus’ division advanced by shore-to-shore movements as far east as Talasea without encountering any large numbers of Japanese.44

The enemy garrison at Cape Gloucester, especially Matsuda’s command, had been in poor physical condition before the invasion. The incessant air attacks against barge supply routes had forced it onto short rations, and malaria, dysentery, and fungus infections were rife.

The 17th Division commander, Lt. Gen. Yasushi Sakai, seems to have had little heart for a resolute defense, for he urged General Imamura to approve a retreat to the Willaumez Peninsula. Imamura at first refused, then assented in January. On 23 February he ordered Sakai’s entire command-- 17th Division, 65th Brigade, 4th Shipping Group, and all attached units—to retreat all the way back to Rabaul and help defend it.

Base Development

Repair of the wrecked airdrome began in early January with the arrival of the 913th Engineer Aviation Battalion. The work was complicated and slowed by jungle, rain, and swampy ground, and by nocturnal air raids that prevented night work for nearly two weeks. GHQ and the Fifth Air Force revised their requirements and directed construction of a 5,000-foot strip and a second, parallel strip 6,000 feet long. The 864th and 141st Engineer Aviation Battalions arrived later in January and turned to on the strips and on roads and airdrome installations. By the end of the month 4,200 feet of the first airstrip had been covered with pierced steel matting, but it was 18 March before the strip was completed. By then Rabaul, Kavieng, and the Admiralties had been neutralized or captured and GHQ was planning the first giant step of its advance to the Philippines, a step which took it far beyond range of fighter planes based at Cape Gloucester.45 The parallel 6,000-foot strip proved impossible to build and was never completed.

Cape Gloucester never became an important air base. It is clear that the Arawe and Cape Gloucester invasions were of less strategic importance than the other CARTWHEEL operations, and in the

light of hindsight were probably not essential to the reduction of Rabaul or the approach to the Philippines. Yet they were neither completely fruitless nor excessively high in casualties. The 1st Marine Division scored a striking tactical success at the cost of 310 killed, 1,083 wounded. And the Allied forces of the Southwest Pacific Area had, by means of these operations, broken out through the narrow straits.

Saidor

The first two DEXTERITY operations faced toward Rabaul, and as events later showed had much less effect on the course of the war than the other CARTWHEEL operations. But in December 1943 General MacArthur reversed his field and decided to exploit the tactical successes at Arawe and Cape Gloucester by moving west to seize Saidor, on the north coast of the Huon Peninsula. (See Map 12.) General Chamberlin had suggested Saidor in September, but it was 11 December before an outline plan was prepared.46

Saidor lay slightly northeast of Mounts Gladstone and Disraeli, which glower at each other from their 11,000-foot eminences. It had a prewar airstrip, and had been used as a barge staging point by the Japanese. Lying 110 nautical miles from Finschhafen, 52 from Madang, and 414 from Rabaul, it was well situated to support the advance westward toward the Vogelkop and the move northward against the Admiralties. In addition Allied seizure would cut the 18th Army in two, for that army’s main concentrations were at Madang–Wewak to the west, and at Sio–Gali to the east.

Preparations and Plans

The invasion of Saidor was not actually decided on until 17 December, two days after the invasion of Arawe and nine days before the invasion of Cape Gloucester. On that date General MacArthur ordered Krueger to prepare plans at once for an operation from Goodenough Island to seize Saidor and construct an advanced air and naval base there. Allied Air and Allied Naval Forces would support, and again MacArthur made Krueger responsible for coordination of planning by the ground forces and the commanders of close support air and naval forces. The New Guinea Force, whose troops were now advancing against Sio and patrolling in the Ramu Valley beyond Dumpu, would support by continuing the move against Sio and by vigorous demonstrations in the Ramu

Valley. U.S. Army Services of Supply was to haul supplies for the operation forward to Cape Cretin, where Krueger was to establish a temporary staging area and supply point pending the time that the U.S. Army Services of Supply base at Finschhafen began operating. Ground combat forces would come from the ALAMO reserve for Cape Gloucester, the U.S. 32nd Division which had fought in the Papuan campaign. In addition MacArthur assigned two engineer aviation battalions, an amphibian truck company, and an engineer boat and shore regiment.

Assignment of the mission to ALAMO Force instead of New Guinea Force represented a departure from the principle that New Guinea Force would command all operations in New Guinea. The change was probably made because nearly all trained Australian divisions were either committed to action or withdrawn for rest, and because it seemed clear that all the ALAMO reserve would not have to be committed to Arawe or Gloucester.

MacArthur gave Krueger and his air and naval colleagues little time to get ready. Actual initiation of the Saidor offensive, he announced, would depend on the progress of operations on Cape Gloucester, because landing craft for the former would have to come from the latter. It was expected, however, that D Day would be 2 January 1944, or shortly thereafter. Two days’ notice would be given.

GHQ’s first outline plan had envisaged a parachute assault to take Saidor, but that was decided against because there still were not enough forward airfields to support current bombing operations and a parachute assault at the same time. The attack would have to be made by ground troops.

For the attack Krueger organized the MICHAELMAS [Saidor] Task Force under command of General Martin, assistant commander of the 32nd Division, who had just reached Goodenough Island. Most combat troops of the task force came out of the force Krueger had originally organized for Gasmata. The rest were those assigned by General MacArthur. Martin’s force was built around the 126th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division, which included the 120th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm howitzers).47 At the time of assignment the 32nd Division units of the task force had just moved to Goodenough Island from Milne Bay. The rest of the force was scattered at such diverse points as Milne Bay, Kiriwina, and Lae.

Although time for planning and preparing was short, and the pressure of Admiral Barbey’s duties prevented him from conferring frequently with Krueger in person, the reports of the participating units bear witness to the fact that the experience and state of training of the commanders and troops were so high that things went smoothly.

General Martin hastily organized a headquarters for his task force, taking as the nucleus Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 126th Infantry. To

Rear Adm. Daniel E. Barbey, left, and Brig. Gen. Clarence A. Martin, center, observing landing operations at Saidor, 2 January 1944

this were added some officers from 32nd Division headquarters. Col. Charles D. Blanchard, task force G-3, came from ALAMO Force as did a complete engineer section. Col. J. Sladen Bradley, commander of the 126th, also served as deputy commander and chief of staff of the MICHAELMAS Task Force.

Plans began to take shape on 20 December at a conference in ALAMO headquarters at Goodenough Island. Present were Admiral Barbey; Maj. Gen. William H. Gill of the 32nd Division; General Heavey of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade; Brig. Gen. Edwin D. Patrick, ALAMO Force chief of staff; Col. Clyde D. Eddleman, G-3 of ALAMO Force; General Whitehead; General Martin; and Colonel Blanchard. Whitehead, Patrick, and Eddleman presented their ideas, as did Barbey, who was just about to leave for Cape Gloucester. Both Barbey and Martin felt that, as Saidor was known to be lightly held by the enemy, preliminary air bombardment on the beaches on D Day would be of less value than a surprise landing at an early hour in the day. This conference was followed by two other brief ones during the next ten days.

As there was neither time nor opportunity for ground reconnaissance of Saidor, the landing beaches were chosen from aerial photographs. Three beaches,

designated RED, WHITE, and BLUE from left (south) to right on the west shore of Dekays Bay just east of Saidor were selected. They were rough and stony but were chosen because they were close to the objective, because the beach gradient was steep enough to enable the troops to make a dry landing, because there was solid ground behind them, and because Dekays Bay could be expected to offer protection from the northwest monsoons prevailing at that time of year.

Formal orders were published in late December.48 Admiral Barbey organized his force generally as follows:–

| APDs: | ||

| RED Beach | 3 | |

| WHITE Beach | 2 | |

| BLUE Beach | 4 | |

| LCIs: | ||

| RED Beach | 6 | |

| WHITE Beach | 6 | |

| BLUE Beach | 4 | |

| Destroyers: | ||

| Escort | 4 | |

| Bombardment | 6 | |

| Cover | 5 | |

| Control and rocket vessels: | ||

| 2 LCIs and 2 SC’s | ||

| Supply Group: | ||

| 6 LSTs |

These ships would carry the assault troops from Goodenough and land them at Saidor on D Day. Six more LSTs would land additional troops and equipment on D plus 1, and LST shipments would continue to bring in troops and supplies from Goodenough and Cape Cretin for some time thereafter.

The assault waves of troops would land from the APDs in thirty-six LCP(R)s as follows: The 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry, was to land on RED Beach at H Hour with two companies abreast, while the 2nd Battalion, 126th, put one company on WHITE Beach and one company on BLUE; the 1st Battalion, 126th, would land from LCIs on WHITE Beach at H plus 30 minutes. All units would push inland and reconnoiter. Field and antiaircraft artillery were to land soon after the assault infantry. Forming the shore party would be A Company, 114th Engineer Battalion; the Antitank Company and part of the Cannon Company, 126th Infantry; and the Shore Battalion, 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. In all, seven thousand men and three thousand tons of gear were to be put ashore on D Day.

Plans for naval gunfire called for two destroyers to put 575 5-inch rounds of deep supporting fire at inland targets between H minus 20 minutes and H Hour. Four destroyers would fire 1,150 rounds at the beach from H minus 20 to H minus 3 minutes when the lead wave of landing craft would be nine hundred yards from shore. Fire from rocket-equipped LCIs would cover the landing craft during the last nine hundred yards. In accordance with Martin’s and Barbey’s desire for surprise, the air plans did not provide for a preliminary bombardment on D Day. Provisions were made, however, for bombers to strike at inland targets after H Hour, and for strafers and fighters to execute supporting missions on call.

H Hour was set for 0650, fifteen minutes before sunrise—the earliest possible minute that would allow adequate light for the earlier naval bombardment.

Weather could be expected to be either squally with rough surf or pleasant with smooth surf, and subject to sudden change from one extreme to the other.

Troops of General Martin’s task force, aside from the 32nd Division units, were arriving at Goodenough while the plans were being prepared. Some units arrived short of clothing and equipment, and these were supplied as well as possible.

Meanwhile General Krueger, concerned over the difficulties of supplying Arawe, Cape Gloucester, and Saidor simultaneously, argued in favor of postponing Saidor. But General MacArthur, Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, and others, promising to make sure that enough supplies arrived at Saidor, and unwilling to lose momentum, agreed that the operation would be valueless if postponed. Preparations went forward.49

Admiral Kinkaid, a cool, soft-spoken, bushy-eyebrowed product of many years in the U.S. Navy, had relieved Admiral Carpender as commander of Allied Naval Forces and of the Seventh Fleet in November. A classmate of Admiral Turner at the Naval Academy, he had already had ample experience in the Pacific, having commanded carrier task forces during the Guadalcanal Campaign and led the invasion of the Aleutians.

On 28 December General Patrick notified Martin that the Cape Gloucester operation was proceeding successfully, and that his task force would probably invade Saidor on 2 January, the estimated date. As the LSTs would have to sail from Goodenough on 31 December in order to reach Saidor on D Day, Martin concluded that loading would have to start on 30 December, for the task force assembly area on Goodenough lay eighteen miles from the embarkation point. He ordered his force to move to the embarkation point at once. Movement and loading continued night and day, usually in rain which turned the roads into mud. On 30 December Martin received word officially that D Day would definitely be 2 January.

APDs and LCIs took aboard only troops, individual equipment, and individual or squad weapons. Heavy equipment, vehicles, motor-drawn weapons, bulk supplies, and some troops went aboard the LSTs. Martin was forced to make a last-minute change in embarkation plans on 30 December when he found there would be nine APDs instead of the ten he had expected. The surplus infantrymen were ordered aboard an LCI, but since the units involved were then moving to the embarkation point some did not receive word of the change until they had reached the beach.

The difficulties were all overborne, and by 0830, 31 December, the six LSTs had departed Goodenough. Their slots at the beach were promptly taken by the six that were to bring heavy equipment to Saidor on D plus 1. The LCIs left Goodenough in midafternoon, and the fast APDs completed loading at 1700. There had not been opportunity for a dress rehearsal, but the LCP(R)s of the APDs practiced landing formations at Goodenough Bay.50

For the soldiers and sailors aboard the APDs New Year’s Eve passed quietly. Martin, the APD captains, Colonel Bradley, and the battalion commanders conferred aboard the destroyer Stringham and made minor last-minute changes in landing plans. Some of the ships showed moving pictures. At 0600 on New Year’s Day, 1944, the APDs sailed. They put in at Oro Bay en route, where they were joined by Admiral Barbey in his flagship, the destroyer Conyngham, to which General Martin transferred his command post afloat. During the ships’ approach to Saidor on 1 January, sixty B-24s and forty-eight B-25s hit the Japanese installations with 218 tons of demolition bombs.

Barbey’s final run through the straits to Saidor was unexciting. The early part of the night of 1-2 January was clear, with a quarter moon shining on the ships. After midnight the sky became overcast and rain fell.

Seizing Saidor

When the ships and landing craft hove to in Dekays Bay before sunrise of 2 January, heavy overcast and rain obscured the shore. Admiral Barbey postponed H Hour from 0650 to 0705 to provide more light for naval gunfire, loading and assembly of boats, and identification of beaches. There followed another delay of twenty minutes while LCP(R)s formed up. The destroyers and rocket LCIs fired the scheduled 1,725 5-inch shells and 624 4.5-inch rockets at the beaches and inland areas. Troops aboard ship, one thousand yards offshore, felt the concussion of the explosives.

The assault waves meanwhile had boated and assembled, and were churning toward RED, WHITE, and BLUE Beaches. First craft touched down at 0725, and during the next seventeen minutes the four waves of thirty-six LCP(R)s landed 1,440 troops. There was no opposition from the enemy. The sixteen LCIs, organized in three waves, grounded and put ashore more than 3,000 troops.

Each LST had towed an LCM of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade. The LSTs cast loose their tows on arrival offshore, and three LCMs sailed to the beaches with the last wave of small craft. Thirty minutes before the LSTs were scheduled to beach, an angledozer clanked out of each LCM and at once set to work grading landing points and beach exits to use in unloading the LSTs. When the six LSTs beached at about 0800, landing points and beach exits made of gravel and wire mesh were ready. This performance, plus the efficiency of the shore party, which Admiral Barbey praised highly, enabled cargo to come ashore in record time. Each LST rapidly unloaded three hundred tons of bulk supplies and two hundred tons of vehicles and equipment. By 1140 all LSTs had unloaded and retracted. The bad weather delayed the scheduled air bombing, but later in the morning B-24s, B-25s, and A-20s bombed the Saidor airstrip and the high ground inland.51

M10 Motor Carriage mounting 3-inch gun on a rough and stony beach near Saidor, 2 January 1944.

When they reached shore the rifle battalions began to push inland while the artillery established itself and the shore party moved supplies off the beach. Japanese resistance was limited to a few rifle shots. General Martin reported that only 15 enemy soldiers had been near the beaches at the time of the landing, and 11 of these were killed by the bombardments and by soldiers of the 126th. Saidor had a normal garrison of about 50, and on 2 January some 120-150 transients were present. All these promptly took to the hills. American casualties on D Day numbered 1 soldier killed and 5 wounded and 2 sailors drowned at BLUE Beach. Forces ashore numbered 6,779;52 6,602 Army ground troops, 129 from Army Air Forces units, and 48 sailors.

Admiral Crutchley’s task force had performed its usual mission of covering the invasion against Japanese warships from Rabaul, but none appeared. Thirty-nine fighters and twenty-four bombers of the 4th Air Army were based at Wewak but were unable to launch an attack until 1600. By then Barbey’s ships were well out to sea, Martin’s soldiers had dispersed their supplies, and little damage was done.

So ended the first day at Saidor. The speedy efficiency of Saidor operations, when compared, for example, with the Kiriwina invasion of the previous year, bears witness to the Southwest Pacific’s improvement in amphibious technique. Yet the fact that there are flaws in even

the best-executed operations was demonstrated the next morning. The MICHAELMAS Task Force expected six LSTs (each towing an engineer LCM) carrying the 121st Field Artillery Battalion and A and D Batteries, 743rd Coast Artillery Gun Battalion (Antiaircraft), to arrive at 0700, 3 January, which would be after daylight. When three vessels came dimly in view about a hundred yards from the north shore at 0510 and failed to identify themselves, the shore defenses opened fire. The vessels withdrew. After daylight they returned and were correctly identified as three of the six expected LSTs.

Thereafter shipments of troops and supplies on the LSTs were uneventful. The 808th Engineer Aviation Battalion arrived on 6 January; the larger part of the 128th Regimental Combat Team came in on 16 and 19 January in response to General Martin’s request for more troops; the 863rd Engineer Aviation Battalion was landed on 29 January. By 10 February, when General Krueger declared DEXTERITY over, and GHQ announced that U.S. Army Services of Supply, Southwest Pacific, would take over supplying Saidor, Arawe, and Gloucester on 1 March, the Saidor garrison numbered 14,979 in addition to a small naval detachment. Forty men had been killed, 111 wounded; 16 were missing.

Base Development

Construction missions assigned to the engineers included building or installing an airfield, roads, fuel storage tanks, docks, jetties, a PT boat base, and a hospital. Work on the airfield started promptly and in itself was not difficult, since the prewar field was in fair condition. The amphibian engineers unloaded ships and built roads, but continuous rainfall hindered their work and General Martin occasionally diverted the aviation engineers to assist the amphibians in their work. The Americans were assisted in all phases of construction work by native labor. A detachment of the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit consisting of one officer, several enlisted men, and eleven native policemen had landed on 2 January to supervise the employment of New Guinea natives. Seven days later 100 native workers came up from Lae, and by 10 February there were 13 policemen, 200 Lae natives, and 406 local workers at Saidor. C-47s landed on the airfield on D plus 9, and by 10 February it was almost ready to receive warplanes.

Junction With the Australians

In the days immediately following D Day General Martin disposed one battalion in defensive positions on each flank, with the third patrolling in the mountains between the flanks. There were some fourteen miles of coast line between the flanks which were held by the coast artillery, supported by other units.

The MICHAELMAS Task Force was hardly ashore when General Krueger warned that, as the Japanese troops in the vicinity of Sio were preparing to move west to Madang, an attack against Saidor was to be expected. These warnings were repeated on 7 and 9 January. General Martin asked for more troops on 10 January and General Krueger sent him the 1st and 3rd Battalion Combat Teams of the 128th Regimental Combat Team.

Meanwhile patrols went to the east, west, and south. There were occasional

brushes with scattered Japanese patrols, but no pitched battles. January ended without an attack. The Japanese were known to be advancing west, but they had not yet touched Saidor.

Almost from the very outset General Martin had urged an advance to the east to hem in the Japanese between his forces and the advancing Australians, but, partly because it apparently did not wish to commit additional troops, and partly because of garbles in the transmission of messages, ALAMO headquarters did not at once accede to Martin’s desires.53

Doubts regarding Japanese intentions were dispelled on 6 February when from a newly established observation post in the Finisterres. American soldiers saw large numbers of Japanese troops marching along an inland trail that ran south of Saidor through the mountains and foothills. It was concluded that the Japanese were bypassing Saidor.

The conclusion was correct. In late December General Adachi, concerned over the state of things to the east, had flown from Madang to 51st Division headquarters at Kiari. He received word of the American landing at Saidor just before he went overland to the 20th Division at Sio. Opinion at General Imamura’s Rabaul headquarters was divided over the best course of action. Some staff officers argued that the 20th and 51st Divisions should attack Saidor. Others counseled that they slip peacefully past Saidor over an inland route and proceed to Madang to join with the remainder of the 18th Army to defend Wewak. Abandoning the attempt to hold the shores of the straits, Imamura decided in favor of bypassing Saidor. He sent orders to that effect to Adachi at Sio.

Adachi placed General Nakano of the 51st Division in charge of the retreat and directed the 41st Division to move from Wewak to defend Madang. Adachi left Sio by submarine “in a troubled state of mind because he would again have to force the two divisions to go through difficulties.”54 He later ordered General Nakai to send eight companies out of the Ramu Valley to Bogadjim. They were to advance down to the coast to harass Saidor while Nakano’s force retreated.

Nakano, who first directed the 20th Division to retreat along the coast while the 51st Division and naval units moved inland, eventually decided to avoid enemy opposition by sending the whole force through the Finisterres.

The retreat began promptly. Sio was abandoned to the 9th Australian Division and the Japanese moved up the coast, then headed inland east of Saidor. The retreat to Madang, almost two hundred miles away by the coastal route, was another of the terrible Japanese marches in New Guinea. The troops struggled through jungles, across rivers, and over the awesome cliffs and mountains of the Finisterres. Fatigue, straggling, disease, and starvation characterized the retreat. “The men were no longer able to care for themselves and walked step after step looking ahead only a meter to see where

they were going.”55 The two divisions had totaled twenty thousand in December 1943; only ten thousand wearily entered Madang in mid-February.

Yet that the ten thousand made such a trip and that the Japanese could make such marches in retreat and in the advance are tribute and testimony to the patient fortitude and iron resolution of the Japanese soldier. They clearly illustrate that despite his baggy uniforms and bombastic phrases he was a formidable opponent.

After the fall of Sio the 5th Australian Division relieved the 9th and advanced up the coast. Its advance patrols made contact with those of the MICHAELMAS Task Force on the Yaut River about fourteen miles southeast of Saidor on 10 February 1944.

Because permission to move east was received too late, Martin could not block the Japanese in that direction. And the escape route to the south ran up and down such steep ravines and slopes that no heavy weapons could be carried there, and the Americans could not block that route either. General Martin decided to attack to the west. The move, executed by elements of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 126th Infantry, began at once.

General Gill and his staff reached Saidor on 18 February to assume command, and continued the westward move. By 24 February patrols of the 3rd Battalion, 126th, had reached Biliau at Cape Iris, about twelve land miles from Saidor. On 5 March the 126th Infantry (less the 2nd Battalion), the 121st Field Artillery Battalion, and B Battery, 120th Field Artillery Battalion, disembarked from engineer landing craft at Yalau Plantation, twenty miles farther on. By now the 7th Australian Division had broken out of the Ramu Valley and General Nakai was retreating toward Madang. Patrols of the 32nd U.S. and the 7th Australian Divisions made contact at Kul between the Sa and Karnbara Rivers, about eight miles beyond Yalau Plantation, on 21 March. The Australians went on to take Bogadjim on 13 April.

Meanwhile Imperial General Headquarters had transferred the 18th Army and the 4th Air Army out of the 8th Area Army and assigned them to control of the 2nd Area Army to pull Adachi’s troops out of Madang and west to Wewak, Aitape, and Hollandia. Adachi’s troops started west again, evacuating Madang just before the Australians entered from the east on 24 April.56 So the large-scale attack on Madang envisaged in ELKTON III never came off. Saidor proved to be an effective and economical substitute.

Securing of the major objectives of Operation II of CARTWHEEL was completed by the seizure of Saidor, and subsequent operations on the Huon Peninsula were anticlimactic strategically, however bitter and tragic they were for those who fought and died in them. The Saidor landing completed the seizure of the Markham–Ramu trough and the Huon Peninsula for the Allies and obtained one more airfield to support operations against the Admiralties and enemy bases to the west.

Strictly speaking, Saidor was the last invasion of the CARTWHEEL operations. With it General MacArthur fulfilled the provisions of the Joint Chiefs’ orders of 28 March 1943. But he and Admiral Halsey were not yet finished with the Japanese in the Southeast Area. By the end of 1943 Rabaul had not yet been completely neutralized, and before the approach to the Philippines could begin there remained a set of subsidiary, transitional operations to be accomplished. These, which the Joint Chiefs and MacArthur had discussed earlier in 1943, would complete the encirclement of Rabaul and would provide a naval base to substitute for Rabaul in the drive to the Philippines.