Chapter 16: Action in the Admiralties

The Decision

First Plans

By the time Halsey’s forces invaded the Green Islands, the Southwest Pacific’s plans for moves to the Admiralties and Hansa Bay, which had been started in November 1943, were well developed.1 On 13 February General MacArthur issued operations instructions to the South and Southwest Pacific Areas which called for these commands to gain control of the Bismarck Archipelago and to isolate Rabaul by seizing Manus and Kavieng about 1 April.2 To General Krueger’s ALAMO Force, supported by Allied Air and Allied Naval Forces, he assigned responsibility for the seizure of Seeadler Harbour and Manus, as well as Hansa Bay. Using naval construction battalions and Army service units furnished by Admiral Halsey, Krueger was to start building a major naval base at Seeadler Harbour and to develop the Japanese airfields at Lorengau on Manus and Momote Plantation on Los Negros. MacArthur also warned Krueger to make ready for the drive west along the New Guinea coast.

As in past and future operations, Krueger was responsible for the coordination of plans. But in these orders General MacArthur departed from the previous practice in his area and adopted principles similar to those prevailing in the South and Central Pacific areas. He specified that the amphibious (naval) commander would be in command of all assault forces, ships and troops but not aircraft, until the landing force was established ashore. Then the amphibious commander would pass the command to the landing force commander, who would become again responsible to his normal military superior—General Krueger in the case of units assigned to the ALAMO Force.3

The operations, as planned, differed from previous ones in another important respect. In one general area three separate naval forces would be operating: Halsey’s, Kinkaid’s, and the additional forces from Nimitz. Chamberlin therefore suggested that in the event of a major naval action command of these

forces be vested in Halsey, who would be the senior admiral present.4 This suggestion was accepted, although for some reason it was not followed in similar situations at Hollandia and Leyte.

Forces assigned to General Krueger for the Admiralties totaled 45,110 men. They included:–

| Forces | Number of Men |

| Southwest Pacific ground units | 25,974 |

| – 1st Cavalry Division | |

| – Antiaircraft and coast artillery units | |

| – 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment | |

| – 1st Marine Amphibian Tractor Battalion | |

| – Engineer, medical, ordnance, quartermaster, signal, and naval base units | |

| Air units: No. 73 Wing, RAAF | 2,488 |

| South Pacific naval construction units | 9,545 |

| South Pacific Army service units | 7,103 |

These were to be concentrated at Oro Bay and Cape Cretin. The 6th Division was designated as GHQ reserve.

Hansa Bay was supposed to be invaded on 26 April by the 24th and 32nd Divisions. There an air and light naval base would assist in the isolation of Rabaul and the Madang–Alexishafen area and would support operations westward.5

The Target: Enemy Dispositions

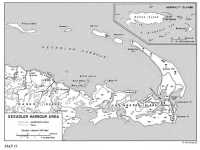

The Admiralties, lying 200 miles northeast of New Guinea, 260 miles west of Kavieng, and 200 miles northeast of Wewak, were admirably situated to assist in isolating Rabaul and in supporting the approach to the Philippines. They contained two airfields as well as a superb harbor. The Japanese had built and used the airfields but, possessing Rabaul, had never made extensive use of Seeadler. This harbor, formed by the horseshoe-shaped curvature of the two major islands, had a surveyed area 6 miles wide, 20 miles long, and 120 feet deep, ample for the fleets of World War II. Guarding the harbor entrance is a line of islets—Koruniat, Ndrilo, Hauwei, Pityilu, and others—which parallel Manus’ north coast.6 (Map 19)

Manus, the largest in the group, is separated from Los Negros by a narrow strait, Loniu Passage. Forty-nine miles from east to west and sixteen miles across, Manus is a heavily wooded island of volcanic origin. Mangrove swamps cover much of the shore line. A range of mountains, two thousand to three thousand feet in height, extends the east-west length. Many of the streams were navigable for small boats, and nearly all could be forded except when in spate. Principal overland routes consisted of four native tracks: three ran from the north coast over the high country; the fourth extended from Lorengau to the west part of Manus.

Los Negros, much smaller than Manus, is irregularly shaped and cut by several inlets. Papitalai Harbour, an extension of Seeadler Harbour, is separated from Hyane Harbour by a low spit only fifty yards across. Natives had built a skidway over the spit to drag their canoes from one harbor to the other.

Map 19: Seeadler Harbour Area

The center part of Los Negros, in the vicinity of Momote, is flat and fertile. The swampy region north of the skidway had some coconut plantations. West of Momote are three jungled hill masses about two hundred feet high.

The thirteen thousand natives (Melanesian with some Micronesian admixture) lived largely in Los Negros and eastern Manus. Coconut was the standard commercial crop. The natives, who sailed their large canoes with skill, also dived for trochus shell and pearls. The climate—hot and wet—is about the same as that of the rest of the region.

Japanese troops had landed at Lorengau in April 1942 and developed an airfield there. The next year they built a 5,000-foot strip at Momote and improved the Lorengau field. Toward the end of the year, as the Allies advanced to the Markham Valley, the Huon Peninsula, and Cape Gloucester, the Japanese began using the Admiralties’ fields as staging points for aircraft flying between Rabaul and Wewak and Hollandia.

Up to now the garrison had consisted of the 51st Transport Regiment, but when the Japanese decided to strengthen Kavieng they also decided to reinforce the Admiralties. Elements of the 14th Naval Base Force, the main body of which was stationed in New Ireland, were sent to Los Negros and Manus. On 9 December General Imamura directed Adachi to send one infantry regiment and an artillery battalion from New Guinea to be rehabilitated in the Palaus, from where they were to proceed to the Admiralties.7 The 66th Infantry reached the Palaus safely, but replacements and reinforcing units en route from Japan were lost to a U.S. submarine. Then Imamura organized an infantry and an artillery battalion in the Palaus out of other replacements. These set out for the Admiralties in January, but their ships were so harried by submarines that they turned back. Imamura therefore arranged with Kusaka for destroyers to carry the 2nd Battalion of the 1st Independent Mixed Regiment from Kavieng to the Admiralties. This movement was accomplished on 23-25 January, and at the month’s end the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry, was dispatched. Though it suffered air attack on the way, it arrived safely.

By 2 February the Japanese garrison consisted of the two infantry battalions, the 51st Transport Regiment, and several naval detachments. In command was Col. Yoshio Ezaki, who also led the 51st Transport Regiment. He disposed his main strength on Los Negros to defend Seeadler Harbour and Momote airfield against attack from the north. An Allied attack through Hyane Harbour was not expected because it was small, with so narrow an entrance that landing craft would come under fire as they passed through.

“Prepare for Immediate Reconnaissance in Force”

General Kenney’s Allied Air Forces had prepared elaborate plans for supporting the Admiralties invasion from Dobodura and Nadzab. During January and the first two weeks of February his planes bombed the Admiralties and Kavieng, and also continued their attacks against the Wewak airfields so as to keep them out of action and destroy the 4th

Air Army’s planes. By 6 February Momote and Lorengau airfields were unserviceable, and no planes were present. Antiaircraft fire had stopped completely, not because the guns were destroyed but because Colonel Ezaki, to conceal his positions from the Allies, had ordered his troops neither to fire nor to move about in daylight.

At this time Kenney and Whitehead were eagerly seeking methods by which the whole advance could be made to move more rapidly. Whitehead wanted to get the Admiralties out of the way soon, so that he would have time to concentrate against Wewak and Hollandia in the westward advance. Kenney, who had experience in New Guinea with quick seizures of airfields by light forces, had a scheme in mind for another such operation. Some time before 23 February he told Whitehead to hit Los Negros hard but not to crater the runway. Hoping to force the Japanese to evacuate Los Negros and retire to Manus, he ordered frequent low-altitude photo-reconnaissance missions.8

The Allies were not yet fully aware that Japanese air resistance in the Southeast Area was almost a thing of the past, and that they had won. They knew, however, that the enemy was weakening. The runways at Rabaul were usually cratered. On 21 February Allied intelligence reasoned that Japanese aircraft were “absconding” from Rabaul, probably to Truk and other bases in the Carolines.9 Further, five Seventh Fleet destroyers sank a Japanese transport about one hundred miles east of Lorengau during a sweep on 22-23 February. Survivors testified that they were part of a 400-man detachment of air force ground crews that was being transferred to bases farther north. Three of the destroyers then sank a Japanese destroyer and a cargo ship south of New Hanover, skirted the southwest coast of New Ireland, and steamed safely past Rabaul through Saint George’s Channel, which lies between New Britain and New Ireland, on the way back to base. The other two bombarded Kavieng. No Japanese aircraft opposed either group although these waters had formerly been dominated by Japanese air and surface forces.

On 23 February—shortly after the great Truk raid and the withdrawal of Japanese naval aircraft from the Southeast Area—Whitehead forwarded to Kenney a reconnaissance report from three B-25s that had just flown over Los Negros and Lorengau for ninety minutes. Although they flew as low as twenty feet, they were not fired on, saw no Japanese, no trucks, and no laundry hung out to dry. The airfields were pitted and overgrown with grass. The whole area looked “completely washed out.” Whitehead recommended that a ground reconnaissance party go in at once to check.10

When Kenney received this message he was at his headquarters in Brisbane. Concluding, with Whitehead, that “Los Negros was ripe for the plucking,” he hurried to MacArthur’s office and proposed to MacArthur, Kinkaid, and part of MacArthur’s staff that a few hundred troops carried on APDs seize Los Negros

and repair Momote airfield at once, rather than capture Seeadler Harbour, so that they could be reinforced and supplied by air if need be. This should be a reconnaissance in force. If resistance proved too strong the invaders could withdraw. A quick seizure of the Admiralties, Kenney argued, might make possible the bypassing of Kavieng and Hansa Bay.11

General Willoughby, in contrast with the airmen, was convinced that the Japanese garrison was fairly strong. His estimate for 25 February placed enemy strength at 4,050.12

MacArthur quickly decided in favor of the reconnaissance in force. Next day he radioed orders to Krueger, Whitehead, and Barbey to “prepare for immediate reconnaissance in force.” He directed Krueger and Barbey to send eight hundred men of the 1st Cavalry Division and other units aboard two APDs and one destroyer division from Oro Bay to Momote not later than 29 February. If successful the cavalrymen were to prepare the airfield for transport aircraft and hold their positions pending arrival of reinforcements.13

The Reconnaissance in Force

Preparations

With but five days between MacArthur’s radiogram and D Day there was little time to make ready. But in accordance with GHQ’s earlier orders, planning had begun in January when Krueger directed the 1st Cavalry Division to prepare terrain, logistical, and intelligence studies. Krueger, Whitehead, and Barbey had begun a series of planning conferences on 19 February.

Kinkaid’s and Barbey’s plans, issued on 26 February, provided for transporting and landing the reconnaissance force, then reinforcing it or withdrawing it if necessary. With the cruisers Nashville and Phoenix and four destroyers Rear Adm. Russell S. Berkey was to provide cover during the approach to the Admiralties and to deliver supporting gunfire against Los Negros, Lorengau, and Seeadler Harbour during the landings. The attack group, which Barbey placed under command of Rear Adm. William M. Fechteler, his deputy, consisted of eight destroyers and three APDs.14

The cruisers were added to the force because General MacArthur elected to accompany the expedition, and to invite Admiral Kinkaid to go with him, to judge from firsthand observation whether to evacuate or hold after the reconnaissance. The first plans had called for just one destroyer division and three APDs, but when Kinkaid learned of MacArthur’s decision he added two cruisers and four destroyers. This was necessary because a destroyer had neither accommodations nor communications equipment suitable for a man of MacArthur’s age and rank. A cruiser would serve better, but a single cruiser could not go to the Admiralties. Kinkaid’s policy forbade

sending only one ship of any type on a tactical mission. Therefore he sent two cruisers, and the two cruisers required four additional destroyers as escorts.15

The air plans prescribed the usual missions but necessarily compressed them into a few days. Bad weather limited the air effort on 26 February, but next day four B-25 squadrons attacked Momote and Lorengau while seven squadrons of B-24s attacked the Wewak fields and B-25s struck at Hansa Bay. Heavy attacks against the Admiralties and Hansa Bay followed on 28 February, and that night seven B-24s attacked Hollandia, far to the west.16

Krueger had originally planned to send a preinvasion reconnaissance party to the western tip of Manus, from where it was to patrol eastward for several weeks and radio reports to his headquarters. But the new orders caused him to cancel this plan in favor of a reconnaissance on Los Negros. More data on Hyane Harbour and Japanese dispositions there and at Momote would have been useful, for there was still no agreement on enemy strength in that region. Willoughby’s estimate of 4,050 conflicted sharply with that offered by Whitehead, who stated on 26 February that there were not more than 300 Japanese, mostly line of communications troops, on Los Negros and Manus.17 And the 1st Cavalry Division’s estimate placed Japanese strength at 4,900, despite an assertion in its field order that “Recent air reconnaissance ... results in no enemy action and no signs of enemy occupation.”18

Because Krueger did not wish to risk betraying Allied plans by sending a patrol to Hyane Harbour and Momote, he decided to send one to examine the region about one mile south of the harbor. Accordingly, at 0645, 27 February, a PBY delivered a six-man party of ALAMO Scouts to a point five hundred yards off Los Negros’ southeast shore under cover of air bombardment. The scouts took a rubber boat ashore, found a large bivouac area on southeastern Los Negros, and reported by radio that the area between the coast and Momote was “lousy with Japs.” But when this report reached GHQ Kenney discounted it. He pointed out, with reason, that twenty-five enemy “in the woods at night” might give that impression and that the patrol had examined not the airdrome but only a part of the south end of Los Negros.19

This patrol did provide more data on which to base plans for naval gunfire support. Kinkaid and Barbey decided that one cruiser and two destroyers should fire on the bivouac area while the other cruiser and two more destroyers fired at Lorengau and Seeadler Harbour and other destroyers supported the landing itself.

The 1st Cavalry Division, which was

to provide the landing force, was unique in the U.S. Army in World War II. Dismounted and serving as infantry, it was a square division of two brigades plus division artillery. Each brigade consisted of two cavalry regiments of about two thousand men each. Each regiment was composed of headquarters, service, and weapons troops, and two squadrons. The squadrons contained a headquarters troop, three rifle troops, and a weapons troop. The weapons troop, using the organization of the infantry heavy weapons company, had been added in 1943.20 Division artillery had a headquarters battery, two 75-mm. pack howitzer battalions, and two 105-mm. howitzer battalions.

MacArthur’s orders of 24 February specified that the landing force should number eight hundred men, including five hundred men of one squadron with additional artillery and service troops, but the next day he recommended that a slightly stronger force be used.21

On 26 February Krueger established the occupation force for the Admiralties as the BREWER Task Force. He placed it under Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division, and assigned to it the ground force units previously allotted by GHQ.

For the D-Day landing Krueger and Swift organized the BREWER reconnaissance force under Brig. Gen. William C. Chase, commander of the 1st Cavalry Brigade. It consisted of detachments from 1st Cavalry Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Troop; the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry; two 75-mm. howitzers of B Battery, 99th Field Artillery Battalion; the 673rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (.50-caliber machine guns); the 1st Platoon, B Troop, 1st Medical Squadron; the 30th Portable Surgical Hospital; air and naval liaison officers and a shore fire control party; and a detachment of the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit—or about a thousand men.

If the landing succeeded and the reconnaissance force stayed, the BREWER support force, under Col. Hugh T. Hoffman, was to land on D plus 2. Hoffman’s command embraced the remainder of the 5th Cavalry and the 99th Field Artillery Battalion, in addition to C Battery (90-mm.), 168th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion; A Battery (multiple .50 caliber mount), 211th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion; medical, engineer, and signal units from the 1st Cavalry Division; and E Company, Shore Battalion, 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. The 40th Naval Construction Battalion and detachments from other elements of the 4th Construction Brigade, all from the South Pacific, were to accompany the Support Force.

The remainder of the BREWER Task Force, including the rest of the 1st Cavalry Brigade and the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, was to follow if needed as soon as shipping became available. To shorten sailing time, Cape Cretin was to be used as a staging area for reinforcements.

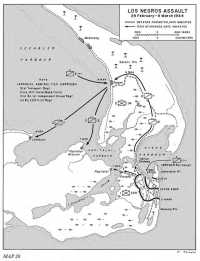

Hyane Harbour, scene of the initial

Map 20: Los Negros Assault, 29 February–9 March 1944

Aboard the cruiser Phoenix, 28 February 1944. Gunfire directed at Japanese heavy guns

Admiral Kinkaid and General MacArthur viewing the bombardment

landing, was indeed an unlikely place. Two small points of land about 750 yards apart flanked the entrance; from them the enemy could put cross fire against landing craft sailing through the narrow gap in the barrier reef. Much of the shore line inside the harbor was covered by mangroves, but on the south, 150 yards behind Momote airfield, a 1,200-yard sandy beach with three jetties offered passage to troops and vehicles. (Map 20)

With H Hour set for 0815 to give bombers time to deliver heavy strikes in support of the landing, the APDs were to anchor five thousand yards off Hyane Harbour. The destroyers carrying troops would enter the transport area to unload their passengers, then return to their fire support stations. Twelve LCP(R)s were to carry the reconnaissance force ashore. The first three waves of four craft each would go in at five-minute intervals, unload, return forty minutes later, and depart again in three waves five minutes apart until the troops were ashore.

To join the expedition, MacArthur and Kinkaid flew to Milne Bay and boarded the cruiser Phoenix in the afternoon of 27 February. The same afternoon at Oro Bay, where the 1st Cavalry Division had been unloading ships and receiving amphibious training, the BREWER reconnaissance force boarded Admiral Fechteler’s ships, 170 men per APD and about 57 men per destroyer. The ships departed Oro Bay in late afternoon and early evening of 28 February, rendezvoused with Berkey’s cruisers and destroyers early next morning just south of

Cape Cretin, and followed eleven miles behind Berkey through Vitiaz Strait and the Bismarck Sea. No enemy ship or plane made an appearance. The sea was calm, the sky heavily overcast, as the ships neared Hyane Harbour.

The Landings

Fechteler ordered his ships to deploy at 0723, 29 February. Cruisers and destroyers took their support stations and commenced firing at 0740. APDs in the transport area lowered landing craft which proceeded toward their line of departure 3,700 yards from the beach.

The heavy overcast and generally bad flying weather prevented all but a handful of Allied B-24s from reaching the Admiralties before H Hour. P-38s, B-25s, and smoke-laying reconnaissance planes arrived later, but before they could attack the overcast closed in so tightly that they could do nothing. “The Fifth Air Force had made its chief contribution in pointing out the opportunity.”22

The first sign of the Japanese came at H minus 20 minutes when the first wave of landing craft reached the line of departure. As it passed through the entrance, enemy 20-mm. machine guns on either side opened fire while heavier guns directed their fire against the Phoenix and the destroyers. The cruiser and the destroyer Mahan promptly silenced a gun on Southeast Point, and other vessels silenced the machine guns. According to Admiral Kinkaid this performance so thoroughly converted General MacArthur into a naval gunfire enthusiast that he became more royalist than the king, and thereafter Kinkaid frequently had to point out the limitations of naval gunfire to the general.23

Support plans called for naval gunfire to stop at 0755 (H minus 20 minutes) so that B-25s could bomb and strafe at low altitudes, but at 0755 no B-25s could be seen nor could any be reached by radio. The ships fired, therefore, until 0810, and then fired star shells as a signal that strafers could attack in safety. Soon afterward three B-25s bombed the gun positions at the entrance to the harbor.24

Thus supported by air and naval bombardment, the leading wave of landing craft, carrying G Troop, 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry, met little fire as it passed through the entrance and turned left (south) toward the beach. It touched down at 0817, whereupon an enemy machine gun crew on the beach scrambled back for cover. The first man ashore, 2nd Lt. Marvin J. Henshaw, led his platoon across the narrow beach to take a semicircular position on the edge of a coconut plantation. There were no American casualties, but several Japanese were killed as they hastily made off in the direction of the airstrip.

The Japanese resumed their positions at the harbor entrance when the naval shelling ceased and fired at the LCP(R)s as they returned to the APDs. The Mahan steamed to within a mile of shore and fired 20-mm. and 40-mm. guns at the southern point. She could not put fire on the point opposite because the LCP(R)s

First wave of landing craft unloading men of G Troop, 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry, 29 February 1944

were in the way. As the second wave started through the entrance so much enemy fire came from the skidway and from the northern point that it turned back. The destroyers Flusser and Drayton then put their fire on the north point while the Mahan pounded the southern. When the enemy fire ceased, the landing craft re-formed, went through the passage, fired their machine guns at the skidway, and landed 150 men of the second wave at H plus 8 minutes.

The second wave then passed through the first about a hundred yards inland. The third wave, which with the fourth received enemy fire on the way in, landed at H plus 30 minutes, pushed southwest, and established a line just short of the airstrip that included most of the eastern revetment area. So far, except for firing at the boats, the Japanese had not fought. At 0900 General Chase radioed Krueger that a line had been established three hundred yards inland, and “enemy situation undetermined.”25 By 0950 the squadron, commanded by Lt. Col. William E. Lobit, had overrun Momote airfield. The troopers found it covered with weeds, littered with rusty fuselages, and pitted with water-filled bomb craters.

While the beachhead was relatively peaceful, the landing craft continued to receive fire on the way in and out. The destroyers continued intermittent

2nd Lt. Marvin J. Henshaw receiving the congratulations of General MacArthur, who awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross, 29 February 1944

bombardment of the harbor entrance for about six hours. By the time the LCP(R)s of the third wave had returned to the APDs, four of the total twelve had been damaged by the enemy gunfire. Because the landing force probably could not be evacuated without the LCP(R)s (although emergency plans called for an APD to penetrate the harbor and evacuate the 2nd Squadron), the landing craft abandoned their schedule and entered the harbor only when the destroyers had forced the enemy to cease fire. A heavy rainstorm, which prevented the few Allied planes over the target from bombing, soon reduced visibility so much that the Japanese fire became ineffective.

The entire reconnaissance force was unloaded by 1250 (H plus 4 hours, 35 minutes). Caliber .50 antiaircraft guns and the two 75-mm. pack howitzers had been manhandled ashore. Two cavalrymen had been killed, three wounded. Five Japanese were reported slain. Two sailors of the landing craft crews were dead, three wounded.

“Remain Here”

By afternoon Lobit’s squadron had advanced over the entire airfield including the western dispersal area, an advance of thirteen hundred yards on the longest axis, without encountering any more Japanese. Patrols moved across the island to Porlaka and north to the skidway without seeing an enemy. But it was clear that the Japanese had not evacuated. Other patrols advancing to the south had found signs of recent occupancy, such as three kitchens and a warehouse full of rations, and a captured document indicated that some two hundred antiaircraft artillerymen were camped nearby.

General MacArthur and Admiral Kinkaid came ashore about 1600. MacArthur awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to Lieutenant Henshaw, inspected the lines, received reports, and made his decision. He directed General Chase “to remain here and hold the airstrip at any cost.”26 Having “ignored sniper fire ... wet, cold, and dirty

Digging a foxhole through coral rock near the airstrip, 29 February 1944

with mud up to the ears,” he and Kinkaid returned to the Phoenix, whence MacArthur radioed orders to send more troops, equipment, and supplies to the Admiralties at the earliest possible moment.27 The cruisers and most of the destroyers departed for New Guinea at 1729, leaving behind the destroyers Bush and Stockton to support the cavalrymen.

Chase and Lobit had obviously concluded that the larger estimate of enemy strength, rather than the airmen’s, was the right one. If all the Japanese they estimated to be on Los Negros should counterattack, the one thousand men of the reconnaissance force would find it very difficult to hold both the airfield and the dispersal area. An inland defense line, about three thousand yards long exclusive of the shore, would have been required to defend them. Because such a line could not safely be held by one thousand men, Chase decided to pull back east of the airstrip. He set up a line about fifteen hundred yards long which ran from the beach southward for about nine hundred yards, then swung sharply east to the sea. The troops did not occupy Jamandilai Point in their rear, but blocked its base that night and cleared it the next morning. The position selected on the edge of the strip provided a ready-made field of fire to the west.

In late afternoon the troopers organized their defenses. The beachhead was too small to permit the 75-mm. pack howitzers to cover the area immediately in front of the lines. Consequently the field artillerymen were turned into riflemen. The .50-caliber antiaircraft guns were set up on the front line. Outposts were established in the dispersal area on the other side of the airstrip. The soldiers found digging foxholes even more arduous than usual, for the soil was full of coral rock. The Americans’ defenses suffered from two weaknesses: the impossibility of field artillery support immediately in front of the line, and the lack of barbed wire.

To remedy the latter, Chase urgently requested Krueger to arrange for an airdrop of barbed wire and stakes, as well as mortar and small arms ammunition, on the north end of Momote drome as soon as possible.28

Careful preparations for defense were more than justified, because except for the air force ground crews the Japanese had not been evacuating either Los Negros or the island group. The larger intelligence estimates had been correct. And the Japanese, warned by American submarines that sent “frequently lengthy operational messages” from south of the Admiralties in late February, had been on the alert for an attack.29 Most of the Admiralty garrison was stationed on Los Negros, with the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry responsible for the defense of the airfield and Hyane Harbour. One battalion defended Lorengau. The Japanese, expecting attack through Seeadler Harbour, had let the Americans slip in through the back door, but now they planned to take action. When General Imamura found out about the invasion, he ordered Colonel Ezaki to attack with his entire strength.30 Ezaki did not immediately use the 2nd Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Regiment, but left it at Salami Plantation north of the skidway. He directed the 1st Battalion, 229th, commanded by a Captain Baba, to attack that night and “annihilate the enemy who have landed. This is not a delaying action. Be resolute to sacrifice your life for the Emperor and commit suicide in case capture is imminent.”31

As dusk fell Japanese riflemen and the American outposts began a fire fight, whereupon the outposts were recalled. Shortly afterward small groups of enemy began moving up against the 2nd Squadron’s line in a series of un-coordinated attacks. Relying chiefly on grenades, the enemy groups attacked in darkness. Some managed to infiltrate through the line and cut nearly all the telephone wires.

Baba’s battalion delivered its heaviest attack against the southern part of the perimeter. Some Japanese, using life preservers, swam in behind the American lines and landed. Another group broke through along the shore at the point of contact of the left (east) flank of E Troop and the right (south) flank of the field artillery unit, which was holding the beach. The Americans defended by staying in their foxholes and firing at every visible target and at everything that moved.

Two Japanese soldiers moved through the darkness and penetrated to the vicinity of General Chase’s command post. Before they could do any damage Maj. Julio Chiaramonte, force S-2, killed one and wounded the other with a submachine gun.

By daylight of 1 March most of the enemy attackers had withdrawn. During the morning the infiltrators who had hidden themselves were hunted down and killed. Seven Americans were dead, fifteen wounded, as compared with sixty-six enemy corpses within the perimeter.

So far the reconnaissance force had held its own. But because the support force would not arrive until the next day patrols pushed westward and northward to determine just what Japanese opposition was to be expected. After moving an average distance of four hundred yards they encountered the enemy in some strength. Clearly, another attack was probable.

Chase’s situation was improved during 1 March by the arrival of more ammunition. As the weather had cleared, three B-25s dropped supplies at 0830. Later in the day a B-17 of the 39th Troop Carrier Squadron made two supply runs, and four B-17s of the 375th Troop Carrier Group each dropped three tons of blood plasma, ammunition, mines, and grenades. The reconnaissance force received no barbed wire.32

Captured documents had indicated the location of many enemy defensive positions, and the patrols that went out in the morning brought back more data. By now the Americans knew that Los Negros’ south coast possessed prepared positions, and that the western dispersal area, Porlaka, and the coast of Hyane Harbour from the 2nd Squadron’s perimeter north to the skidway were fortified. In consequence the two supporting destroyers and the 75-mm. pack howitzers bombarded these areas. Starting at 1600 Fifth Air Force planes bombed the dispersal area, and at 1715, when antiaircraft guns near the south end of the airstrip fired on the planes, the Bush and Stockton pulled to within a thousand yards of the shore and shelled them. Several 4th Air Army fighter planes from Wewak appeared but failed in their effort to drive off the American planes. The air bombardment flushed a body of Japanese, estimated one hundred strong, from cover in the dispersal area. When these men rushed east across the strip in an effort to escape the bombs, most were cut down by the cavalrymen’s fire.

Otherwise enemy ground forces remained quiescent during most of the afternoon except for a seventeen-man patrol of officers and sergeants, led by Captain Baba, which had apparently infiltrated the lines on the previous night. Baba’s patrol came through heavy underbrush to within thirty-five yards of General Chase’s command post. When the Americans sighted the patrol, Chase and his executive officer, Col. Earl F. Thompson, directed the movements of Major Chiaramonte and four enlisted men who moved out to the attack. After Chiaramonte’s party had killed several Japanese, the others committed suicide with grenades and swords.

The Japanese varied their pattern by striking at the perimeter at 1700 instead of after dark in an attack that was weaker than the one of the night before. Daylight simplified the defenders’ task in repelling the attack, which ceased at 2000. Thereafter throughout the night small groups harried and infiltrated the lines. About fifty Japanese used life belts to cross the harbor entrance and attack the position at the base of Jamandilai. In the course of the action the field artillerymen fired three hundred 75-mm. rounds at the enemy and also killed 47 Japanese within the artillery positions with small arms fire. All together, 147 Japanese were killed within the perimeter during the two night battles.

Actually, the Japanese, though possessing numerical superiority, had never used their full strength and had not seriously threatened Chase’s force, which still held its lines intact on the morning of 2 March. Recklessness, coupled with the skill and tenacity of the cavalrymen, had cost the Japanese their best chance.

To the Shores of Seeadler Harbour

Seizure of Momote Airfield

Meanwhile, at Oro Bay and Cape Cretin Colonel Hoffman’s support force, numbering about 1,500 ground combat troops and 428 Seabees, had loaded aboard six LSTs and an equal number of 2nd Engineer Special Brigade LCMs that were towed by the LSTs. These vessels, escorted by Australian and American destroyers and two minesweepers under Capt. E. F. V. Dechaineux of the Australian Navy, made a quiet voyage and stood into Hyane Harbour shortly after 0900 on 2 March.

The two minesweepers and one destroyer steamed to the north of Los Negros in an attempt to force the 1,500 yard-wide entrance to Seeadler Harbour. They encountered such heavy fire from Japanese coastal guns on the guardian islands of Hauwei and Ndrilo that they retired. Captain Dechaineux then brought three more destroyers, which fired at the Japanese while the first three ships again unsuccessfully attempted to force the passage. Minesweeping would obviously have to await ships with heavier guns than those of destroyers and minesweepers.

The LSTs and LCMs made their way through the entrance to Hyane Harbour and beached, whereupon Japanese mortars and machine guns north of the skidway opened up. The landing craft replied with their machine guns, and at the same time B-25s attacked the Japanese positions.

In the midst of the din the combat troops walked ashore. Then bulldozers left the LSTs and began building ramps to get the other vehicles ashore. Unloading was finished by 1700, and the LSTs departed; the LCMs remained in Hyane Harbour.

Before the LSTs left for New Guinea Chase requested that the destroyers put fire in the northern point of land at Hyane Harbour. Four ships each fired fifty 5-inch rounds from close range, but when the LSTs started out of the harbor they met machine gun fire. They replied and made the open sea in safety. One destroyer and the two minesweepers took the LSTs to New Guinea while four destroyers stayed in the vicinity of the Admiralties to intercept any Japanese seaborne attacks.

Since Momote airfield was not yet in American hands, Chase assigned part of the 40th Construction Battalion to a defensive sector on the right (north) flank of the beachhead. The Seabees, meeting some rifle fire while moving into position, used their ditch-digger to scoop out a 300-yard-long trench.

As men, weapons, ammunition, supplies, and equipment came ashore during the day the beachhead became crowded. Chase decided to attack and enlarge his perimeter to include all the airfield, dispersal area, and revetments, and the roads immediately around the airfield. When Hoffman came ashore in the morning he was met by Colonel Thompson, who took him to Chase’s headquarters where the three officers completed plans for an attack by the 5th Cavalry that afternoon.

At 1415, B-25s, P-38s, and P-47s began bombing and strafing the west half of the airfield, the dispersal area, the skidway, and the northern part of Los Negros. This attack lasted until 1530.

The 1st and 2nd Squadrons of the 5th

Cavalry, on the left (south) and right respectively, had attacked at 1500. There was no opposition from the enemy; within the hour Hoffman’s regiment was in possession of the entire airfield and had begun to dig in along the line of the western and southern dispersal bays. The day’s sole casualties, two men killed and four wounded, were caused by three American bombs that fell on positions held by E Troop and antiaircraft artillerymen.

It was clear to the Americans that the Japanese garrison had not yet made its maximum effort, for papers found in the advance over the airfield indicated that Baba’s battalion was still south and west of the airfield. And earlier estimates had placed two thousand troops in the west half of Los Negros and Lorengau. Major Chiaramonte therefore warned the invasion force to expect attacks from the south, from Porlaka in the west, and southward from the skidway.33

The invading Americans carefully prepared their defense positions. The front lines, still without barbed wire, included nearly all the dispersal area. Two antiaircraft batteries and E Company, 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, were assigned to beach defense. Seabees established an inner defense line west and northwest of Chase’s command post. The three 75-mm. batteries of the 99th Field Artillery Battalion set up in revetments some five hundred yards behind the front in a semicircle with overlapping sectors of fire. Because it was next to impossible to prevent the Japanese from infiltrating the front lines, all units inside the perimeter prepared all-round local defenses.34

Ezaki Attacks Again

Colonel Ezaki now was preparing for a larger effort. He planned a coordinated attack, with the 2nd Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Regiment, driving south from Salami across the skidway, while one company, having moved from western Los Negros to Porlaka, struck eastward. Meanwhile, other detachments from the outlying islands and from inland regions of Manus were to concentrate at Lorengau. His forces were slow in concentrating, and Ezaki postponed the attack until the night of 3-4 March. As a result the 5th Cavalry was merely harassed in its new positions on the night of 2-3 March.

The Americans used the daylight hours to strengthen their defenses.35 Bulldozers cleared fields of fire in front of the cavalry squadrons’ lines. To keep infiltration to a minimum, each cavalry troop posted three rifle platoons in line with troop heavy weapons attached to each platoon. Japanese revetments were used as much as possible. Riflemen dug foxholes on the reverse slopes of the mounds, mines were laid in front, and the approaches to all positions were rigged with empty C-ration cans that

contained lumps of coral and were hung close to the ground so they would rattle when struck by a shoe. The 60-mm. mortars were situated to deliver close support fire directly in front of the cavalry squadrons, while the 81s were massed near the center of the perimeter in front of the field artillery to deliver deeper supporting fire. Most of the antiaircraft .50-caliber machine guns were returned to their normal missions, but since the main attacks were expected from the north and west the guns posted on the north end of Momote field facing the skidway remained at the front.

While the riflemen made ready, the artillery and the offshore destroyers fired at every evidence of the Japanese. They put concentrations on enemy groups north of the skidway. At 1600 field and antiaircraft artillery shot up several enemy barges that were observed behind overhanging vegetation on the north shore of Hyane Harbour.

After dusk Japanese patrols began probing the lines, and at 2100 a lone plane dropped eight bombs which cut the telephone wires between the 1st Squadron and the 5th Cavalry command post.

When the plane departed, flares and tracers heralded an attack by the remnants of the late Baba’s battalion against the southwest portion of the perimeter, held by the 1st Squadron under Lt. Col. Charles E. Brady. Mortar and machine gun fire supported the attack, but it was weak. American mortars and machine guns beat off the attackers, although some infiltrated the lines, concealed themselves, and had to be flushed out and killed after daylight.

The 2nd Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Regiment, delivered the main assault from the skidway, which was coupled with a drive east from Porlaka by other detachments. F Troop, which held the north-south portion of the line in the western dispersal area, and G Troop, defending the line from F Troop’s right flank to the beach, received the brunt of the attacks. E Troop suffered only harassing attacks and infiltration. By now the 2nd Squadron, having landed on 29 February, had had more than enough experience in repelling night attacks, but this one differed from earlier ones in which the enemy had moved quietly and concealed himself as much as possible. On this night the Japanese advanced in the open in frontal assault with a good deal of talking, shouting, and even singing. Artillery and mortars opened fire at once.

As they approached F and G Troops, the leading enemy waves hurled grenades, but they fell short of the cavalry lines. The Japanese pushed through the mine fields, taking casualties but not stopping, and drove into the interlocking bands of fire from the machine guns, which promptly cut them down. More kept coming; the cavalry lines held, but some Japanese managed to infiltrate and cut telephone lines. G Troop’s three platoons stayed down in their positions and fired or hurled grenades at all possible targets. Just before dawn some Japanese soldiers penetrated G Troop’s positions and Capt. Frank G. Mayfield organized a quick counterattack and drove them out. A few minutes later the Japanese assaulted again. This time, as two of Mayfield’s platoons had exhausted their machine gun ammunition, the Japanese

nearly succeeded in breaking through. But the Japanese were killed or driven off by a platoon of H Troop heavy machine guns under S/Sgt. Edwin C. Terry.

During these attacks Sgt. Troy A. McGill, of G Troop, was holding a revetment with his squad of eight men. When all but McGill and one other man had been killed or wounded, McGill ordered the other survivor to retire, fired his rifle until it jammed, then fought in front of his position with clubbed rifle until he was slain. McGill’s gallantry won him the Medal of Honor.36

The attacks had been delivered with frequency and resolution throughout the night, but there was little evidence of skill or coordination. For example, about an hour before daylight a column of soldiers advanced down the road from Porlaka, singing, the cavalrymen later reported, “Deep in the Heart of Texas.”37 Mines, machine guns, rifles, and grenades killed nearly all of them.

Reports of the night’s action also relate instances of Japanese shouting false commands in English and tapping telephone lines. One H Troop mortar section thought it heard an order to retreat and abandoned its position with the result that the 2nd Squadron lost its 81-mm. mortar support.

During the night the 99th Field Artillery Battalion fired almost continuously, as did all mortars except those that were abandoned. This fire was delivered in spite of harassing attacks from Japanese who had slipped through the front lines. Three field artillerymen were killed by infiltrators, and one antiaircraft crew abandoned its gun under pressure from the Japanese. Five Japanese, one with a grenade discharger, actually posted themselves on the roof of the dugout containing Colonel Lobit’s command post, but Capt. Bruce Merritt killed them from his nearby foxhole. The Seabees, in their secondary line behind G Troop, passed ammunition to the hard-pressed cavalrymen and toward dawn some moved up to help G Troop hold its line. Other Seabees met a group of Japanese attacking two antiaircraft gun positions and killed them.

By daylight of 4 March the Japanese had pulled back and the close fighting was over, but enemy mortars and field pieces hit the American positions until about 0730. The intensity of the night’s action is indicated by the fact that two of the machine guns in G Troop’s sector had fired a total of 8,770 rounds, and 168 enemy corpses lay directly to the troop’s front. There were no prisoners. Sixty-one Americans were killed, 244 wounded, of whom 9 dead and 38 wounded were Seabees. Ezaki had made his greatest offensive effort and failed. With more Americans due soon, the shattered Japanese units would be capable of defensive action only.

The Advance

On 1 March, meanwhile, at ALAMO headquarters on Cape Cretin General Krueger had completed plans for reinforcement of Chase’s men and for seizure

of the entire Admiralties group.38 Krueger ordered Swift to strengthen the reconnaissance force, seize Seeadler Harbour, extend control over the entire Admiralties, and start building airdromes and a naval base.39 On the 2nd, the day Hoffman’s support force landed, Krueger received an urgent request from Chase, who asked for his other regiment, the 12th Cavalry. Krueger, Swift, and Barbey then arranged to speed up the movement to the Admiralties and land the 12th Cavalry and other units on 6 March, the 2nd Cavalry Brigade on 9 March instead of on 9 and 16 March, as they had originally planned.40 They also arranged to rush the 2nd Squadron and the Weapons Troop, 7th Cavalry, and the 82nd Field Artillery Battalion on three APDs, to arrive on the morning of 4 March.41

General Krueger desired that Seeadler Harbour be opened up. Two factors, besides the obvious one that Allied forces were eventually to use the harbor as a major naval base, motivated him. Hyane Harbour and the initial beachhead were becoming too congested to receive the 2nd Brigade, but Salami Plantation on the west shore of the northwest peninsula of Los Negros offered a good landing place. Clearing the harbor would also make possible a shore-to-shore movement from Los Negros against Manus. Therefore air and naval bombardments of enemy positions on the northwest tip of Los Negros, and on the guardian islands of Koruniat, Ndrilo, and Hauwei were arranged.42 Krueger, on 3 March, ordered Swift to proceed to Los Negros at once, to survey the situation, and to take command ashore.

On the morning of 4 March, shortly after Ezaki’s attack subsided and after supporting Allied destroyers had shelled the skidway and the region to the north, the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry, and the 82nd Field Artillery Battalion (75-mm. pack howitzers) landed at Hyane Harbour. Chase decided to wait for more troops before attacking, and put the 2nd Squadron, 7th, under Lt. Col. Robert P. Kirk, in the line to replace the weary men of the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry. Except for minor harassing attacks, infiltrations, and a one-plane bombing attack, the night of 4-5 March was quiet.

General Swift, accompanied by the 1st Cavalry Division’s chief of staff, Col. Charles A. Sheldon, and the intelligence and operations officers, reached Hyane Harbour aboard the destroyer Bush on the morning of 5 March. He assumed command of the troops ashore at 1100, but since the Bush was busy executing fire support missions he stayed aboard

Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger (front seat) with Brig. Gen. William C. Chase and Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift on an inspection tour, Los Negros Island

until 1600 so as not to interrupt the firing.

Swift directed Chase’s reconnaissance force to clear the major part of Los Negros from Momote to the north and west, and to be prepared to extend over the entire island. He instructed the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, due to arrive on 9 March, to land at Salami Plantation, to be prepared to move to a point on Manus west of Lorengau, and to attack eastward against that airfield and secure the eastern half of Manus.43

To carry out the instructions for seizing all of Los Negros, the 2nd Squadron, 7th Cavalry, was ordered to attack north across the skidway on the afternoon of the 5th. Accordingly the 2nd Squadron, 5th, began relieving Colonel Kirk’s squadron in the perimeter late in the morning. At 1120, while the relief was being effected, the Japanese began a series of harassing attacks, followed after noon by a resolute attack from Porlaka and the skidway. The enemy soldiers who broke into the front lines were all killed while field artillery and mortars broke up the attacks. Twenty-five dead Japanese bodies were counted, but twelve cavalrymen were wounded and it was 1630 before the 2nd Squadron, 7th, was reorganized and ready to attack.

Once it had moved beyond the perimeter,

Kirk’s squadron found that the Japanese had mined the approaches to the skidway. The mines caused some casualties at first but thereafter were successfully detected and removed. The squadron advanced slowly past enemy corpses that littered the road, but by darkness had reached the skidway, where it halted for the night.

Kirk resumed his advance early on 6 March. Later in the morning the 12th Cavalry Regimental Combat Team, commanded by Col. John H. Stadler, Jr., came ashore. Transported to Hyane Harbour aboard four LSTs, the combat team, 2,837 men strong, consisted of the 12th Cavalry; the 271st Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers); three light tanks of the 603rd Tank Company; five LVTs of A Company, 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment; and engineer, medical, and signal troops.44 When it reached shore, the 12th Cavalry, accompanied by the tanks, began moving north across the skidway to join Kirk in the advance, while the 271st Field Artillery Battalion moved into position near the airstrip. The Japanese, obviously in retreat, offered only minor resistance. The advance was slowed chiefly by mud and trees they had felled across the roads and trails to Salami. Near the beach at Salami some Japanese in bunkers and buildings offered fight but were blasted out by tanks and 75mm. howitzers. By 1630 all three cavalry squadrons were established at Salami. The surviving Japanese had escaped by boat and canoe to the west. Thus by the day’s end the 1st Cavalry Brigade held the beachhead where the 2nd Brigade was to land.

Meanwhile air and naval surface forces had been at work on the Japanese positions guarding the entrance to Seeadler Harbour. Two days after the minesweepers were driven off, cruisers and destroyers of Admiral Crutchley’s Task Force 74 bombarded suspected enemy gun positions on orders from Admiral Kinkaid, and on 5 March they fired eighty 8-inch, three hundred 6 inch, and one hundred 5-inch rounds without meeting any return fire.45 Next morning, the lone destroyer Nicholson approached the harbor entrance to draw enemy fire. The Japanese opened up at 850 yards range, whereupon Task Force 74 and Allied bombers struck at the enemy positions thus disclosed. They were bombed again on 7 March by seven B-24s, and on 8 March by seventeen B-24s and eleven B-25s. Thereafter LCMs, destroyers, and other craft entered the harbor freely without encountering enemy fire.

From 6 through 8 March the 5th Cavalry extended its holdings around the airstrip. The 2nd Squadron took Porlaka on 6 March, then crossed Lemondrol Creek in canvas and rubber boats and amphibian tractors to seize Papitalai village on 7 March.

American control over Seeadler Harbour was furthered on 7 and 8 March by the seizure of two promontories northwest of Papitalai. The 2nd Squadron, 12th Cavalry, using amphibian tractors, shuttled from Salami to Papitalai Mission and captured it against

LSTs loaded with troops and equipment landing at Salami Plantation

sharp opposition. The 2nd Squadron, 7th, using LCMs, took Lombrum Plantation.

The 12th Cavalry and the tanks patrolled to the northwest tip of Los Negros to cover the 2nd Brigade’s landing, releasing, in the process, sixty-nine Sikh soldiers that the Japanese had been using as laborers.

On the morning of 9 March destroyers shelled Lorengau and minesweepers checked Seeadler Harbour. Then six LSTs and one cargo ship entered the harbor to land Brig. Gen. Verne D. Mudge’s 2nd Cavalry Brigade and attached units at Salami Plantation.46

Los Negros was now firmly in Allied hands. The next task facing the combat troops was the seizure of Lorengau.

Lorengau

Plans and Preparations

General Swift had assigned responsibility for capturing Manus to the 2nd Cavalry Brigade. General Mudge accordingly had his plans ready the day after his brigade landed at Salami Plantation.47 Not much was known about Japanese

strength on Manus, but reconnaissance had shown that Lorengau airdrome and Lorengau village east of it were fortified. As Lugos Mission was practically undefended, Mudge decided to land there—about 3,000 yards west of the airdrome. (Map 21) The beaches selected, YELLOW 1 and YELLOW 2, lay west and east of the Liei River. YELLOW 1, of coral sand, was 700 yards long, 14 to 26 yards wide, with swamps immediately behind it. YELLOW 2, 100 yards long, gave access to Number 3 Road which led along the coast to Lorengau.

Mudge assigned the assault to the 8th Cavalry, commanded by Col. William J. Bradley. It was to land in column of squadrons, the 1st Squadron in the lead. Troop A was to land in LVTs on YELLOW 2 east of the Liei, C Troop from LCVs on YELLOW 1 to the west. The 7th Cavalry, less the 2nd Squadron, would follow the 8th ashore. The 2nd Squadron, 7th, would constitute the brigade reserve. C Troop, 8th Engineer Squadron, was to land on YELLOW 1, improve the beaches, and bridge the Liei to connect the beaches. Once ashore the 8th Cavalry was to send the 1st Squadron east along Number 3 Road against Lorengau airfield while the other moved inland to Number 1 Road, and then moved east against Lorengau village to keep the Japanese from escaping inland to the jungled mountains where they would have a great defensive advantage.48

The cavalry generals arranged with naval officers and with Capt. George F. Frederick of the 12th Air Liaison Party for ample air and fleet support of the landing, in addition to support by field artillery. The islets north of Los Negros would provide positions from which field artillery could support the 2nd Brigade’s advance east by firing across its front at right angles to the axis of advance, as had been done in New Georgia during the advance on Munda airfield. Therefore plans were prepared for sending patrols to Hauwei, the Butjo Luo group, and Bear Point on Manus, just west of Loniu Passage, to determine enemy strength and look for artillery positions. D Day for Manus was first set for 13 March.

The island patrols, consisting of detachments from the 302nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop plus artillery officers, left Salami on 11 March. Bear Point, though not occupied by the enemy, had so poor a beach that artillery could not be landed. Butjo Mokau, the most northern of the Butjo Luo group, offered good artillery positions and bore no signs of enemy occupation. In late afternoon F Troop, 7th Cavalry, occupied both islands of the group.

The Hauwei patrol, a platoon strong, left Salami aboard an LCV and a PT boat and landed on the western part of Hauwei.49 After the patrol had moved a short distance inland, machine gun, mortar, and rifle fire struck it from the

Map 21: Lugos Mission to Lorengau, 15-18 March 1944

front and both sides. The patrol made a fighting withdrawal to the beach, supported by fire from the PT boat and the LCV. But by the time the cavalrymen made the beach, the PT, whose skipper had been wounded, had returned to its tender. Five men boarded the LCV, but the remainder were still embroiled with the enemy. Mortar shells and machine gun bullets wounded most of the men aboard the LCV, which struck a submerged coral reef two hundred yards from shore and sank, leaving the survivors floating in the water. When about six Japanese started to set up a machine gun on the beach, the cavalrymen still on shore shot them with submachine guns, then took to the water and joined the survivors from the LCV. After three hours in the water, the eighteen men, suffering from exposure to the sun and water, were picked up by a PT boat while a destroyer shelled Hauwei. An LCM later picked up one more man.

Six men of the reconnaissance troop and two artillerymen had been killed, three were missing, and every survivor was wounded as well as burned.50

A larger force was obviously needed for Hauwei, and the landing on Manus would have to be delayed if the artillery was to get into position in time to support the landing. Further, naval officers had already counseled delay in order to provide more time to clear the sea lanes to Lugos Mission.

Accordingly the 2nd Squadron (less F Troop), 7th Cavalry, was selected to seize Hauwei. Supporting its attack would be destroyers, rockets, 105-mm. fire from the 61st Field Artillery Battalion at Mokerang Plantation north of Salami, and P-40s of No. 77 Fighter Squadron, RAAF, which had reached Momote on 9 March. The squadron boarded LCMs at noon, 12 March, set out for Hauwei, and landed under cover of the supporting bombardment at 1400. The squadron later reported that “the covering fire was not accurate and most missiles fell short in the sea.”51

E Troop landed on the west shore under small arms fire while G Troop, debarking on the south, met machine gun fire. The Japanese had rigged trip wires to activate mines, but the soldiers detected and avoided them. Kirk’s squadron then drove inland against rifle fire and by 1500 held a north-south line across Hauwei about three hundred yards from the western tip and one thousand yards from the eastern end. By now the whole squadron was ashore, and H Troop’s 81-mm. mortars were ready to fire. E Troop continued its advance but G stayed in place. As contact broke between the two troops, Colonel Kirk pulled E Troop back and dug in for the night.

General Mudge arrived at 1600 and after receiving Kirk’s report ordered C Troop from Salami to Hauwei, and alerted one medium tank to move to Hauwei next day. C Troop arrived by LCM at 1800 and took up a support position. During the night Japanese on Pityilu fired 20-mm. guns at the 2nd Squadron but hit no one. The 61st Field Artillery Battalion put one thousand rounds of harassing fire on the enemy’s section of Hauwei.

Next morning, at 0900, the tank arrived and Kirk assigned his reconnaissance platoon as close support. The attack began at 1000 with C, E, and G Troops abreast from left (north) to right. On the right a bunker, manned by eight Japanese with two 7.7-mm. machine guns, grenade discharges, and rifles, withstood four direct mortar bursts and four 75-mm. shells before it crumbled. In the center E Troop enveloped a short trench equipped with machine guns, grenade dischargers, and rifles. With these positions reduced the troops moved rapidly. By noon the 2nd Squadron had covered the whole island. Eight Americans had been killed, forty-six were wounded. Forty-three dead Japanese, all sailors, were counted. Captured booty included two 5-inch naval guns and a range-finder. One gun had been hit by the earlier bombardments; the other was in firing condition.

That afternoon the 61st Field Artillery Battalion unloaded its 105-mm. howitzers from LCMs and next day set them up on the southwest side while the 271st Field Artillery Battalion emplaced its 105-mm. howitzers on the west. The 99th Field Artillery Battalion, meanwhile, had emplaced twelve 75-mm. pack howitzers and six 37-mm. antitank guns on Butjo Mokau on 13 March.

The Landing at Lugos

With the artillery now in position, embarkation of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade aboard twelve LCMs, seven LCVs, and one LST began shortly after 0400 on 15 March. The LST and the smaller craft proceeded separately to the rendezvous area off Lugos Mission and assembled about 0800.

The three supporting artillery battalions had begun firing intermittently at Lorengau village at 2100 the previous evening, and at 0830 they shifted their fire to Lugos Mission. Four destroyers lying offshore fired at the shore line between the Tingau River, west of Lugos, and Lorengau until 0900. At 0900 eighteen B-25s from Nadzab arrived overhead and from 0907 to 0925 put eighty-one 500-pound bombs and fired more than 44,000 machine gun bullets on the beaches. At 0925, when the bombers cleared the area, three engineer rocket boats covered the first wave’s landing.

The LST had previously disgorged seven LVTs, and six of them (the seventh was a rocket boat) bore A Troop toward Beach YELLOW 2 while LCVs carried C Troop toward YELLOW 1. When the craft were close to shore, a machine gun east of the beaches opened fire. LVTs, and engineer support craft, and two PT boats replied and the gun fell silent. LVTs and LCVs landed their troops without casualties, and almost exactly on schedule.52

The soldiers of A Troop left the LVTs and drove through Lugos Mission toward Number 3 Road. The few Japanese in the area, mostly sailors, did not offer determined resistance and were killed by A Troop and by later mop-up squads. C Troop, to the west, met no opposition as it advanced to a ridge some eight hundred yards inland where it established defenses to cover the landing of the 2nd Brigade.

Colonel Bradley had ordered the bulk of the 8th Cavalry to land at YELLOW 2 if it proved suitable for LCMs and LSTs, and succeeding waves landed so quickly that YELLOW 2 quickly became congested. The LST, which carried troops, weapons, and vehicles but no bulk cargo, was unloaded in forty-five minutes. It retracted to return to Salami for the 7th Cavalry.53 This regiment, commanded by Col. Glenn S. Finley, landed from the LST and LCMs in the afternoon and took over defense of the beachhead.

Meanwhile the 8th Cavalry had begun its two-squadron advance against Lorengau airdrome and Lorengau village over Roads 1 and 3.

The Advance East: The Airfield and the Village

During the day the 2nd Squadron, 8th, under Maj. Haskett L. Connor, made its way southward along a native track toward Number 1 Road. Tractors borrowed from the artillery towed supplies and ammunition. Japanese riflemen harassed the soldiers as they toiled slowly upward over a continuous succession of ridges. It was 1500 before F Troop, in the lead, reached Number 1 Road, where it ran into fire from three Japanese positions which covered the track’s junction with the road. Enemy mortars to the south added their fire, and Connor decided to dig in for the night. At his request the 61st Field Artillery Battalion silenced the enemy temporarily while the squadron established night defenses about six hundred yards from the road.

The next morning, 16 March, General Mudge and Colonel Bradley visited the squadron and observed its attack which, supported by one light and two medium tanks, overran the positions and enabled Connor’s squadron to move east along Number 1 Road. The tanks had been hauled through the jungle with the aid of a D-7 bulldozer which cut down grades, cleared undergrowth, and towed the tanks when they stuck. One tank and the bulldozer remained attached to the 2nd Squadron on its advance along the road. By late afternoon it had reached a position on the road about a thousand yards west-northwest of Lorengau village and eight hundred yards south of the airstrip.

The chief obstacle to the 2nd Squadron’s advance was terrain. The 1st Squadron (less C Troop) had had to fight its way along the coast on Number 3 Road. After landing on the morning of 15 March, the 1st, under Maj. Moyers S. Shore, had started east along the road behind A Troop. The road led through heavy rain forest interspersed with mangrove swamp on low ground. “The recent rains had softened the red clay until it assumed a glue-like consistence which made the footing difficult and slowed leading elements.”54

About one mile out of Lugos A Troop was halted by three pillboxes.55 With the beach on one side and mangrove swamp on the other, there was no space for maneuver. Without orders from the troop commander one squad attempted an unsupported frontal assault which failed. Major Shore then alerted B Troop to pass through A and assault upon completion of an artillery preparation. From Hauwei 105s of the 271st Field Artillery Battalion swept the enemy area with shells that burst as close as a hundred yards from the cavalrymen. B Troop attacked but was quickly halted.

Shore then asked for a tank, more artillery fire, and a strike by RAAF P-40s (armed with 500-pound bombs), which had been on station since before H Hour, and arranged for 81-mm. mortar support. “The combination of fire and bombs” turned the trick. They “plowed the position into a mass of craters,” and B Troop advanced past “the blasted

remains of the pillboxes and scattered parts of their tenacious occupants. ...”56

The three pillboxes had apparently constituted the airstrip’s western defenses, for when they crumbled the 1st Squadron moved freely down the road. By 1700 it had advanced out of the jungle and held a ridge among the palms overlooking the southwest corner of the airstrip. Two of the squadron had been killed, eleven wounded, in the course of the action. Forty Japanese were reported killed. During the night of 15-16 March Shore’s squadron, which C Troop rejoined at 1800 after its relief at the beachhead by the 7th Cavalry, received rifle fire from Japanese in a palm grove between the airfield and the sea.

Next morning, 16 March, Shore decided to hold up his attack while an A Troop platoon went north of the strip to clear out the enemy riflemen and C Troop moved along the south edge of the airdrome to reconnoiter enemy positions there. It was noon before the A Troop platoon accomplished its mission and the 1st Squadron could move.

Meanwhile C Troop, after advancing 200 yards over a series of rolling coconut studded ridges which lay at right angles to the axis of advance, was halted by machine gun fire from a ridge about 150 yards to its front. The troop commander, Capt. Winthrop B. Avery, emplaced the heavy machine guns and 81-mm. mortars which had been attached from the Weapons Troop and attempted a coordinated attack. One platoon was to make a frontal assault while a second platoon worked around the south flank. The frontal attack failed, but the flanking platoon, commanded by S/Sgt. Ervin M. Gauthreaux. literally gained the top of the enemy positions, threw grenades into two pillboxes, and flushed several Japanese.57

But at this point things went wrong. With the enemy threat removed from his left (north) flank, and aware that C Troop was held up, Shore decided to leave C Troop in place to hold the enemy while the remainder of A Troop followed its other platoon through the palms and squadron Headquarters Troop, B Troop, and elements of D Troop drove down the airdrome on C’s left. As B Troop advanced in the open it was struck by fire from the very positions that Gauthreaux’ platoon was straddling, whereupon it halted, withdrew, and as it carried its casualties back to safety returned the enemy’s fire. But the fire hit Gauthreaux’s platoon, and Avery was forced to order him off the Japanese positions.58

After four hundred 105-mm. rounds had pounded the enemy position, C Troop attacked frontally while B Troop completed its retirement. But the Japanese still remained in their positions on the ridge and broke up C Troop’s attack. By now all elements of the squadron had been committed and the Americans had advanced to about the center of the airstrip.

General Mudge arrived on the scene, inspected the squadron, reconnoitered the front, and decided to relieve the 1st Squadron, 8th, with the 7th Cavalry. During the relief, which was effected

Men of the 8th Cavalry moving a 38-mm. antitank gun to a firing position near Lorengau Village, 18 March 1944

about 1600, the 7th Cavalry lost five men killed and fifteen wounded.

With the previous day’s experience as a guide, General Mudge and Colonel Finley planned a coordinated attack for 17 March. The 7th Cavalry and the 2nd Squadron, 8th, were to take the remainder of the airstrip and push on over the Lorengau River to the village. The 1st Squadron, 7th, with squads from the 8th Engineer Squadron attached, was to seize the eastern end of the airdrome while the 2nd Squadron, 7th, moved south of the strip to make contact with the 2nd Squadron, 8th, and advance to the river on Number 1 Road.

During the night of 16-17 March destroyers and field artillery battalions shelled the Japanese positions, and in the early morning twenty-four 81-mm. mortars, two light tanks, and two 37-mm. antitank guns put their fire on the pillboxes. An 81-mm. mortar of D Troop, 8th, attached to the 7th Cavalry, demolished one pillbox and its .50-caliber and .30-caliber machine guns and crew of fifteen men with a direct hit. When the mortars ceased fire automatic weapons opened up, and the 1st Squadron, 7th, assaulted. “At 1033 when our troops came out of their fox-holes there were numerous cries of ‘Garry Owen’ as the 1st Squadron went into its first action against the Japanese.”59

There was little resistance, since the

supporting fires had “practically wiped out all enemy resistance except for necessary mopping up of a few bunkers still remaining intact.”60 The 1st Squadron, under Maj. James A. Godwin, quickly seized the ridge that had held up Shore’s squadron the day before, then encountered another ridge position slightly to the east. After artillery and mortars had pounded it, cavalrymen moved in and occupied it. Flame throwers destroyed the pillboxes that remained in action.

Meanwhile noon found the two inland squadrons in contact with each other. By 1300 all three squadrons were in contact and had resumed the eastward advance. Only a few scattered Japanese opposed the move from the airstrip to the river, but emplaced mines caused some casualties and slowed the advance, so that it was 1500 before the three squadrons pulled up on a ridge on the west bank that overlooked the village. It was too late in the day to attack Lorengau, which the Americans had reason to believe was strongly defended. The 7th Cavalry’s reconnaissance platoon had immediately crossed the river over the sandbar at its mouth, met fire from Japanese positions west of Lorengau, and withdrawn. Landing craft bringing in supplies received fire from the hills above the village. And, on the person of a Japanese officer who died defending the airdrome, the Americans had discovered maps of the defenses of Manus which showed that Lorengau and the road leading overland through the villages of Old Rossum and Rossum were fortified.

Lorengau lies in a cup-shaped valley surrounded by 400-foot-high hills. Most of the Japanese defenses faced seaward, although positions also covered the roads leading east, west, and south. As the Lorengau River was about sixty feet wide and ten to twenty feet deep in most places, the 2nd Brigade’s best approach route led over the alluvial sandbar at the mouth. The enemy had planted mines, controlled by a master switch in a pillbox on the hillside, on the stretch of beach between the sandbar and the hills. They had put foxholes and machine gun emplacements about a hundred yards inland from the shore, and had built about twelve pillboxes in the hills. The attackers would have to cross the river and the beach in full view of the enemy positions, but two factors favored an assault: repeated bombings and shellings had uncovered several Japanese positions so that they were visible, and the ridge taken in the 17 March attack provided good observation over Lorengau.

The 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry, was designated to make the attack with mortar and artillery support. At 1000, 18 March, the reconnaissance platoon led out in single file followed by E, F, and G Troops. The move was unexpectedly easy; only scattered machine gun fire was directed at the reconnaissance platoon, which quickly cleared the beach and the rifle pits. It cut the master cable leading to the mines. Later a dead Japanese was found in a small pillbox with the detonator switch clutched in his hand.

The rifle troops received fire and some casualties while crossing the river, but got over rapidly. On the east shore they

Crossing the Lorengau River over the sandbar at the mouth of the river, 18 March 1944

deployed and prepared to attack. E Troop was to assault the enemy center in Lorengau with F Troop echeloned to the right rear; G Troop was to take the hills beside the river. Artillery and 81-mm. mortars hit the enemy once more, and when their fire ceased 60-mm.’s and machine guns opened up, whereupon the cavalry troops assaulted the bunkers with grenade, submachine gun, rifle, and flame thrower. Again, it was unexpectedly easy, for the Japanese apparently retreated inland over Number 2 Road.61 Eighty-seven Japanese were killed defending Lorengau, while the 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry, captured it at a cost of seven wounded.

Fighting in the Admiralties was not yet over; it was 18 May before General Krueger officially terminated the operation. Los Negros was not cleared of the enemy until the end of March, and it took two squadrons, several tanks, P-40 strikes, and a good deal of artillery fire before the 2nd Brigade cleared Number 2 Road to Rossum on 25 March. But the capture of Lorengau airfield, following the seizure of Momote, placed in Allied hands the main strategic objectives of the operation. During the entire operation (including the seizure of more outlying islands in April) the 1st Cavalry Division lost 326 men killed, 1,189 wounded, and 4 missing. It reported burying 3,280 and capturing 75

Troop G, 8th Cavalry, near Number 1 Road on the west side of the Lorengau River, 18 March 1944

of the enemy, and General Krueger estimated that the Japanese had disposed of 1,100 more bodies.62

Base Development

Meanwhile several battalions of Seabees, plus Army engineer units, were building airfields and a naval base. MacArthur, Nimitz, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff had intended that the naval base be used by all Allied fleets serving in the Pacific. In February Nimitz proposed to Admiral King that Admiral Halsey, who furnished most of the service troops, be given responsibility, under Nimitz, for developing and controlling the base.63 Nimitz’ proposal was rejected by the Joint Chiefs but not before MacArthur became so irate that he ordered work on the Admiralties “restricted to facilities for ships under his direct command—the Seventh Fleet and British units.”64 Halsey, whom MacArthur vainly requested as his commander of Allied Naval Forces, made a hurried trip to Brisbane in early March and found that MacArthur “lumped me, Nimitz, King, and the whole Navy in a vicious conspiracy to pare away his authority.”65 Halsey was in a difficult position. MacArthur was very angry; he was Halsey’s superior, and was vastly senior

to him.66 And it is probably gratuitous to say MacArthur was formidable in argument. The scene, as Halsey records it, was lively, with MacArthur expressing himself strongly. “Unlike myself,” the Admiral wrote, “strong emotion did not make him profane. He did not need to be; profanity would have merely discolored his eloquence.” But the ram-jawed Halsey could also be formidable. Supported by Kinkaid and Carney, he asked the General to rescind his order: “... ‘if you stick to this order of yours, you’ll be hampering the war effort!’” Halsey went on to say that “the command of Manus didn’t matter a whit to me. What did matter was the quick construction of the base. Kenney or an Australian or an enlisted cavalryman could boss it for all I cared, as long as it was ready to handle the fleet when we moved up New Guinea and on toward the Philippines.” After long argument, General MacArthur agreed to cancel his order and the work went forward under Admiral Kinkaid’s direction.67