Chapter 7: Consolidating the Beachhead

Build-up of the Assault

In the initial landings on Butaritari a platoon of Company C, 102nd Engineers, was attached to each of the infantry battalion landing teams. One squad of each platoon was distributed over the first-wave boats of the assault companies and came ashore prepared to clear beach and underwater obstacles with Bangalore torpedoes. The remainder of the platoon of engineers landed with the reserve of the infantry battalion landing team.

Shore parties were furnished by the 152nd Engineers. Company A was attached to the 3rd Battalion Landing Team at Red Beach 2, Company B to the 1st Battalion Landing Team at Red Beach 1, and Company C to the 2nd Battalion Landing Team at Yellow Beach.

All three shore parties encountered unexpected difficulties. As the 27th Division’s engineer reported, “Red Beach was a beach in name only and afforded landing with difficulty for about six boats at flood tide.” At Red Beach 2, landings could be made only for about three hours before and after flood tide, and even then only with considerable difficulty. Since the tide was high at H Hour, troops and supplies could be landed there with relative ease for the first few hours, but as the tide approached the ebb, progress in unloading was slowed down. The lagoon off Yellow Beach was of course too shallow to float LCVPs or LCMs closer than 200 yards offshore, and up to noon of the second day of the operation the only supplies to reach this beach had to be transferred from landing craft to amphibian tractors at the reefs edge. By that time, sectional pontoons, brought along by naval vessels and set up on all beaches, projected far enough to seaward to permit all types of landing craft to debark their supplies directly without transferring them first to amphibian tractors. Also by then, King’s Wharf, including the seaplane runway, was sufficiently repaired to accommodate all the shore parties of the 152nd Engineers, which moved to the pier and organized two shifts to assist in unloading.1

The difficulties at Red Beaches clouded an otherwise successful landing. By the close of the first day’s action, only a small part of the supplies and equipment had been unloaded, and even some of the troops were still far from shore aboard small craft as night closed in. By evening of D Day, Leonard Wood had unloaded approximately 38 percent of her supplies and equipment and Calvert about 23 percent. Not all of this had reached shore, however. Some was still embarked in landing craft at nightfall. By 1800 all the transports had completed their unloading for the day and got under way for night cruising dispositions.2

Unloading supplies at King’s Wharf

Also among the first waves to land at all beaches were communications personnel carrying both radio and telephone equipment. These were provided by the Detachment, 27th Signal Company, the communications platoon of the 165th Regimental Combat Team, and three teams of the 75th Signal Company, each attached to a battalion landing team. Shortly after landing they were able to establish radio contact between the troops ashore and the division and regimental commanders still afloat. Uninterrupted radio contact between ship and shore, however, was at first difficult to maintain. Radio sets were wet from the brief rain squall that had occurred early in the morning and were further damaged by waves and spray breaking over the landing craft during the long wait between loading from the transports and landing at the beaches. Landing craft grounded on the reefs, and since all personnel had to wade ashore in water from waist to shoulder depth, radio and telephone equipment was further damaged. Some difficulty was also encountered in maintaining contact by wire run laterally along Red Beaches—amphibian tractors churning across the beach, for example, often tore up the wire. Wires strung from trees later in the day made communications more reliable.3

More serious was the fact that during the first day of landing no direct radio communication was established between the 1st and 3rd Battalion Landing Teams on Red Beaches and the 2nd Battalion Landing Team on Yellow Beach, although previous arrangements had been made for this by the allocation of an appropriate frequency and the assignment of necessary radio sets. Late in the day, it is true, occasional messenger service connected the 2nd Battalion Landing Team with the rest of the force on the west end of the island, but not until the morning of the second day of operations was full radio, wire, and messenger service established between Red and Yellow Beaches.4 In view of the fact that these two forces were approaching each other in a delicate maneuver that required precise timing and complete coordination, the absence of direct radio contact between them was a serious handicap.

Another defect in communications noted during the first days of the Makin operation was faulty communications procedures. Greenwich civil time and local time were used interchangeably in the date-time groups of messages and in the time specified in the contents of the messages. Authenticators were seldom used, although standard procedure required it. Many message centers were apparently under the impression that local time was zone plus-9½ (that is, Greenwich civil time plus 9½ hours) whereas it was actually zone plus-12, thus causing a 2½-hour error in their dispatches. None of this was fatal, but it did cause some avoidable confusion at headquarters.5

Most serious was the failure, or rather absence, of communications between tanks and the infantry units that they were supposed to support. The tanks attached to the 27th Division for this operation were equipped with radio sets that could not operate on either the infantry or artillery nets. From the outset this caused considerable confusion and was largely responsible for the poor infantry-tank coordination that characterized the fighting on Makin. The only sets in the division that could operate with the tanks were those of the 27th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop. Therefore, it was necessary to attach a radio team from that unit to each battalion landing team headquarters. In the lower echelons (rifle companies, platoons, and squads, and tank platoons and individual tanks) there was no communication agency capable of linking the components of the infantry-tank teams.6

In spite of these difficulties and defects in establishing and maintaining direct contact between lower echelons, communications between the task force commander (Admiral Turner) and the various units ashore and between the regimental and division commanders and the elements under them were reported generally satisfactory. This was provided in part by the air liaison parties, and the shore fire control parties, which were landed fairly early in the operation and were attached to each battalion landing team.7

Two shore fire control parties were assigned to each battalion. These landed

with their respective infantry battalions and were immediately able to furnish close supporting fires on call. On D Day one cruiser (Minneapolis) and two destroyers (Dewey and Phelps) were designated to deliver fires on request from these parties. However, no requests were received, either on that day or later in the operation. This failure to call upon naval guns can be explained in part by the relatively limited area lying between Yellow Beach and Red Beaches, an area apparently considered by troop commanders to be too restricted to risk calling on naval fire for support. In spite of the fact that the shore fire control parties were not called upon to perform the functions for which they were primarily intended, they did provide a valuable and sometimes the only communications liaison between ship and shore.8

To each battalion landing team was also attached an air liaison party whose function was to call for air strikes in support of ground troops at the request of the respective troop commanders. Air Liaison Party U-13, attached to the 3rd Battalion Landing Team, was in position ashore about 100 yards from the beach by 0910. The party attached to the 1st Battalion Landing Team (ALP U-11 ) reported in position at 1110. That attached to the 2nd Battalion Landing Team (ALP U-12) was held up off Yellow Beach by the air attack against the hulks, but was able to get ashore by 1258.9 As in the case of naval fire, no close air strikes were called for against land targets on D Day, but again the air liaison parties had reliable and consistent communications with the various headquarters afloat and in many instances, especially during the early hours after the landing, these groups and the shore fire control parties were the only sources of information available to higher echelons.10

One other important communications net was that established between the field artillery batteries and the division commander, once the latter got ashore. Although communications by wire between artillery units and infantry units was impossible to maintain because of the damage wrought by tanks and tractors, radio communications were deemed satisfactory. Also, the radios manned by artillery personnel often filled the gap created by the failure of communications between infantry units and command posts. It was rare that the division commander could not secure information from the front lines of any battalion landing team through the artillery communications setup.11

One result of these initial failures in communications ashore (contrasted with the comparatively superior ship-to-shore communications setup) was to delay moving the entire division headquarters from Leonard Wood until the second day of the

operation.12 In spite of these difficulties all other command posts were set up on the island before nightfall of the first day’s action. Colonel Conroy had left his ship as early as 0900, and by 1100 the regimental command post was set up ashore.13 Meanwhile, Colonel Hart, commanding the 3rd Battalion Landing Team, had opened his command post, as had Colonel Kelley of the 1st Battalion Landing Team.14 By 1800 General Smith was ashore, although his command post still remained afloat.15

First Night on Butaritari

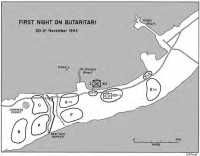

By the time action against the enemy had been closed in the late afternoon of 20 November, the first objectives of the invasion of Makin had in the main been accomplished. Except for the small pocket contained by Company C, the West Tank Barrier system had been reduced. Other secondary aims had also been realized. A solid holding line facing east had been established, and the likelihood of any substantial Japanese reinforcement of the West Tank Barrier reduced to a minimum. Beachheads had been secured on two shores and were in process of development. Artillery was ashore and had already fired a few missions in support of Company E’s advance eastward. All command posts were ashore except the division’s.

With the virtual reduction of the West Tank Barrier, the troops facing the main body of Japanese on the eastern part of the island automatically became the front-line units. The principal element in the east on the night of D Day was Company E, reinforced by one platoon of Company G and a part of Detachment Z of the 105th Infantry, one of the special landing groups.

The nearest American position behind the front-line elements was the medium tank park established by the 193rd Tank Battalion near the center of Yellow Beach. This was some 500 yards to the rear of Company E’s line. Tank crews either stayed in their vehicles or joined Company H and the Yellow Beach shore party in digging a perimeter defense. The command post of the 2nd Battalion was also located on Yellow Beach, adjacent to the perimeter established by the tank battalion.16

About five hundred yards farther to the west, dug in near the lagoon along the eastern edge of the West Tank Barrier system, was Company G, less the platoon that had joined Company E. Company F dug in directly south of Company G, in the same area. Beyond the tank trap, Company C set up its night position just east of the “pocket” that had caused so much trouble during the afternoon. The other three companies of the 1st Battalion were in position along the southern half of the west barrier system, bending back to the west along the ocean shore. The remainder of the 165th Regimental Combat Team was spread out over the island from the West Tank Barrier to Red Beaches. The 3rd Battalion had assembled just southwest of Rita Lake shortly after its relief and dug in there for the night. General Ralph Smith, after coming ashore at 1800, had ordered Colonel Hart to prepare his men for a movement to Kuma Island, northeast of Butaritari, at 0900 the next morning. Disturbing news from Tarawa prompted Admiral Turner to disapprove this projected move, however. The 3rd Battalion was to be maintained in readiness at Rita

Map 5: First Night on Butaritari, 20-21 November 1943

Lake for trans-shipment to Tarawa if it should be needed there.17

The 105th Field Artillery Battalion dug in for the night near its guns south of Ukiangong Village and was prepared, if called upon, to furnish night fires for the units farther to the east. Nearby was the second bivouac area of the 193rd Tank Battalion, occupied mainly by the amphibian tractors of the Red Beach special landing groups and by light tanks. Another platoon of light tanks was situated at Red Beach 2, where practically all the remaining troops ashore had assembled.18

As night closed in on the island, it appeared probable that the enemy would adopt one or more of three courses. He could defend his current positions in depth, withdraw to the eastern part of Butaritari and then cross over to Kuma Island, or counterattack in force.19

Actually, no major counterattacks were undertaken by the Japanese during the first night, nor was there any organized withdrawal eastward. Some successful attempts were made to bolster defenses along the eastern line and a few positions at the base of King’s Wharf were reoccupied and new machine gun emplacements

constructed facing the American lines. One machine gun was placed in the wrecked seaplane lying in the lagoon off of King’s Wharf, another at the base of King’s Wharf, and three more were set up in buildings in the area immediately southward.20

Also, a few efforts were made to work small patrols into the area of the West Tank Barrier system. Some of these were intercepted. One, of from twelve to sixteen men, tried to move around the left flank of Company E near the sandspit, but was stopped by rifle fire.21 In the sector assigned to Detachment Z, 105th Infantry, several enemy infiltrated American positions. Three were killed and two wounded by rifle fire and grenades.22 One twelve-man patrol did manage to slip along the ocean shore and reach a point between Companies A and B. Only twenty feet from Company A its members stopped to fire at Company B, which had been discovered to the front. When dawn came the enemy was revealed only a few yards away and the whole patrol was killed without trouble.23

The communications breakdown among units of the Japanese militated against any successful reinforcement of the West Tank Barrier system, for while patrols were attempting to infiltrate the system, survivors behind the American lines were trying to get out. For example, one ten-man group was killed by grenades and BAR fire as it tried to escape toward the ocean early in the morning.24

These instances constituted the only recorded cases of organized Japanese counter-activity during the first night after the landing on Butaritari, and there is no evidence that these various movements of small patrols were in any way coordinated. Other than that, the enemy’s countermeasures were limited to sniper fire from lone riflemen located within or close to the U.S. lines. This was kept up all night and was reportedly accompanied by a variety of ruses such as dropping lighted firecrackers to attract American fire and calling out messages in garbled English.25

One effect of these tactics was to precipitate a breakdown of fire discipline among the green and nervous American troops. “Trigger-happy” soldiers peppered away indiscriminately at unseen targets throughout the night, not only wasting ammunition but, more important, drawing frequent counter-fire. The worst example occurred just after daybreak when a man from the 152nd Engineers ran along the lagoon shore from the direction of On Chong’s Wharf toward the command post of the 2nd Battalion, shouting, “There’s a hundred and fifty Japs in the trees!” A wave of shooting hysteria swept the area. When the engineer admitted that he had seen no enemy but had merely heard firing, shouted orders to cease fire proved ineffectual. Direct commands to individuals were necessary. The harassing tactics of the enemy were to this extent effective.26

Final Mop-up at the West Tank Barrier and Yellow Beach

The first problem to be solved on the morning of the second day was the elimination of the enemy still left alive in or near the West Tank Barrier system. The

M3 Medium Tanks shell the hulks off On Chong’s Wharf

Japanese still held a small wedge-like pocket just northwest of the barrier and from that position could bring guns to bear on the east-west highway, which was now the main supply route from Red Beaches. Also, the approaches to Yellow Beach were not yet secure, and any attempts to bypass the pocket by bringing supplies through the lagoon would be handicapped by fire from the west. The two hulks on the reef near On Chong’s Wharf, which had been so heavily attacked from the air and sea on D Day, were once more believed to be occupied by the enemy.

As landing craft came into Yellow Beach early on the second morning, some of them “returned” fire against the hulks, aiming at the top decks of the ships. On shore, among the American troops in or near the West Tank Barrier clearing, intermittent bursts of machine gun fire were received for as long as two hours after dawn. These were probably “overs” directed at the hulks from the landing craft. At 0818, while landing craft stayed clear, the first of a long series of air strikes, which continued until 1630, began against the hulks.27 At 0920 several of the medium tanks went to the water’s edge and shelled the derelicts with their 75-mm. guns. They were reported to be overshooting by some 2,000 yards, their shells falling into the lagoon in the middle of the boat lanes. Whether from enemy or from friendly fire, the approach to Yellow Beach was so dangerous

for the landing craft that, as late as 1230 when the tide was beginning to ebb, about forty of them were still circling well out in the lagoon, afraid to come in.28

Finally, late in the afternoon, Captain Coates, commanding officer of Company C, was ordered to dispatch a detail to investigate the hulks. He ordered 2nd Lt. Everett W. McGinley to take sixteen men in two LVTs to board the two vessels and eliminate whatever he found there in the way of enemy positions. They found nothing. The top deck of each ship was so wrecked, twisted, and torn that in McGinley’s opinion no enemy could have fired from there without being in plain view. From the top deck there was a sheer drop to the bottom of the hulks without any intervening deck. Water, waist-high, covered the bottom. The only possible location for hidden Japanese was a two-foot ledge that ran around the interior walls of both hulks. Although he found no empty shells or weapons McGinley admitted that some might have been on the lagoon bottom hidden from view by the water.29

Whether or not the hulks had ever contained enemy positions remains doubtful. Lt. Col. William R. Durand, the official observer sent to Makin by General Richardson’s headquarters, had no doubts. On the question as to whether the hulk contained machine guns he reported, “I am certain that it did; not only because it interrupted landing operations and actually caused a few casualties but also because a captured overlay showed the positions.”30 The testimony was corroborated by all the officers and men of Company F who were interviewed on the subject. This was the company that dug in along the West Tank Barrier about 300 to 500 yards from the hulks. All claimed that on the second morning, for about an hour or more at intervals of every few minutes, direct fire from the hulks hit into the dirt right along their line of positions.31

On the other hand, in Colonel Kelley’s opinion, the belief that fire was being directed from the sunken vessels both against the lagoon and inland was a hallucination from beginning to end. It was his belief that the fire that observers thought to be coming from the hulks against landing craft as they came through the lagoon was actually coming from the shore. He also believed that fire later received by troops on shore from the direction of the lagoon came not from the hulks but from landing craft that were firing at the hulks and sending “overs” into the areas occupied by friendly troops. This conclusion was confirmed by Lt. Col. S. L. A. Marshall, the official historian assigned to the operation by the Historical Branch, G-2, War Department General Staff.32

With all this conflicting testimony, it is impossible for the historian to reach any final conclusion except to say that the weight of the evidence would seem to indicate that the hulks had been unoccupied by the enemy from the very beginning of the operation. In any case, it is certain that after the investigation conducted by Lieutenant McGinley, no more fire was heard from the hulks or the area near them.

Meanwhile, operations against the pocket west of the tank barrier had begun at 0800 under the direction of Major Mahoney, the 1st Battalion commander. He ordered S. Sgt. Emmanuel F. DeFabees to skirt the pocket with a patrol and enter it

from the right flank. The sergeant cut sharp right for fifty yards and then sought to force an entrance, his men crawling on their bellies. The patrol “found the fire too heavy.” It then went obliquely for seventy-five yards and was again turned back. By this time DeFabees was convinced that much of the fire was coming from friendly forces and the patrol was withdrawn. It was about this time that Company A was firing toward a supposed Japanese machine gun nest on the lagoon side of the island and Company F along the tank trap was receiving fire from the direction of the lagoon itself, which may or may not have been from American landing craft. In any case, there was considerable confusion on the part of all hands as to just what were the sources of fire against U.S. positions in the west of the West Tank Barrier.33

Thirty minutes after DeFabees had withdrawn his patrol, at 0840, Major Mahoney announced that Company C had cleared out the pocket and was reorganizing and extending to Company B.34 This announcement was slightly premature since the flank was not considered entirely secure until about noon.35

The liveliest action in the West Tank Barrier zone occurred in a coconut grove along the eastern edge of the barrier clearing, just north of the middle of the island. About 1030 a group of Japanese began firing rifles and light machine guns into the platoon of Company F that was mopping up along the former stronghold. Captain Leonard asked for three light tanks to come up and give him help. The tanks, after reporting, moved over to the highway, which skirted the northern edge of the clearing, so that their line of fire was toward the ocean. While the tanks were spraying the tree tops with machine gun fire and canister they were approached by a fourth towing fuel along the highway. After the latter’s tow cable snapped it also joined the other tanks in the attack.

The four tanks had been firing for about five minutes when a Navy bomber suddenly swung over them at a very low altitude and dropped a 2,000-pound fragmentation bomb about twenty-five feet from one of the tanks. 1st Lt. Edward J. Gallagher, the tank officer in charge, was killed, as were two enlisted men nearby. Several others were injured. By the time the tank crews had recovered from surprise and concussion, the Japanese were giving no further trouble.36

This episode at the tank trap closed the action at the West Tank Barrier. No further important difficulty was encountered with enemy stragglers in that zone. Attention could now be fully centered on the drive eastward to secure the remainder of the island.