Chapter 8: Makin Taken

The plan for the capture of Makin, though divided into three phases, was a continuing process that involved no major regroupings of forces. After the establishment of the beachheads on Butaritari the first objective had been the reduction of the West Tank Barrier, and this was followed by a drive to the east and pursuit of the enemy to outlying islands. The West Tank Barrier had been reduced during the first day’s action. The second day would see—in addition to the mopping up of the area around the West Tank Barrier and of the western end of Butaritari—the beginning of the drive to the east. The situation at Tarawa had prevented General Ralph Smith from moving the 3rd Battalion, 165th Infantry, to Kuma Island early on the morning of the second day, a move that would have eliminated much of the need for the third phase of the operation. He dispatched that morning, however, a small party under Maj. Jacob H. Herzog, assistant intelligence officer of the division, with orders to investigate Kuma for the presence of Japanese forces.1 Also, air observers were instructed to keep a close watch for any signs of a large enemy movement to the outlying islands.2 With these precautions, the main attention of the 165th Regimental Combat Team was centered during the second day on the drive to the eastern end of Butaritari.

The Main Action of the Second Day

The plan of attack for the second day provided that Company E and attached elements should immediately push eastward from positions of the night before while Company F should remain in reserve near Yellow Beach. General Smith’s order, sent out the previous evening, had set the jump-off hour at 0700, following an intense artillery preparation.3 Colonel McDonough, however, elected to defer the advance of the infantry until the medium tanks were ready, and these were delayed until enough fuel could be brought forward.4

During the interim aircraft pounded the area in front of the 2nd Battalion. At 0843 the air liaison party attached to McDonough’s battalion requested bombing and strafing of the zone ahead of Company E as far as the East Tank Barrier. This was complied with. As soon as McDonough had ascertained that the tanks would be fueled by 1045 he ordered the attack to

jump off at 1100. Meanwhile, at 1026 he radioed to his supporting aircraft that “tanks and troops are moving forward” and that all bombing and strafing should cease. Although this cancellation was acknowledged and confirmed, the air columns formed for the bombing runs kept coming in as originally ordered. Fortunately, Captain Ryan, Company E’s commander, exercised firm control over his troops and was able to hold back their advance until the air attacks had ceased. Thus the faulty air-ground coordination caused no damage beyond delaying the attack even longer.5

By 1110 the attack was at last in progress.6 Ten medium tanks had been refueled and had moved into position to support the troops,7 and Colonel McDonough chose to rely exclusively on these vehicles to support his infantry. Although both the forward observer and the liaison officer from the artillery battalion repeatedly suggested that fire be placed well in advance of the front line to soften up the enemy, the infantry commander declined it. He even refused to allow the forward observer to register the artillery battalion until after the day’s action had ceased.8 Although the 105-mm. pieces on Ukiangong Point fired a total of twenty-one missions early in the morning, not a single howitzer was fired after 0630.9

On the extreme left was Detachment Z of the 105th Infantry. Next to it came the 1st Platoon, Company G, which had reinforced the 3rd Platoon, Company E, throughout the night. In the center was the 1st Platoon and on the right the 2nd Platoon of Company E. All units moved forward in a skirmish line. Fifty yards to the rear, mopping up Japanese stragglers, was a second formation consisting of the 3rd Platoon, Company E, the 2nd and 3rd Platoons, Company G, and a detail of marines consisting of the 4th Platoon of the V Amphibious Reconnaissance Company.10

The line advanced steadily, though slowly, averaging about three yards a minute. 1st Sgt. Thomas E. Valentine of the front echelon of Company E described the opposition encountered:

On the second day we did not allow sniper fire to deter us. We had already found that the snipers were used more as a nuisance than an obstacle. They would fire, but we noted little effect by way of casualties. We learned that by taking careful cover and moving rapidly from one concealment to another we could minimize the sniper threat. Moreover, we knew that our reserves would get them if we did not. So we contented ourselves with firing at a tree when we thought a shot had come from it and we continued to move on.11

West of the tunnel that had been taken during the previous afternoon but subsequently relinquished, the enemy fell back again. In the next 200 yards, from the tunnel to the road crossing the island from the base of King’s Wharf, the stiffest resistance of the day was encountered.

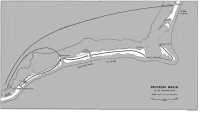

Map 6: Second Day’s Action, 21 November 1943

From an enemy seaplane beached on the reef, machine gun and rifle fire struck at the left flank and in toward the center of the line. To allay this nuisance, four of the medium tanks finally pumped enough shells from their primary weapons at close range to annihilate the eighteen occupants concealed in the plane’s body and wings.12 On the right an emplacement, intended mainly for defense against landings from the ocean, contained three dual-purpose 3-inch guns. Farther on, at the ocean end of the cross-island road, a twin-barreled, 13-mm. dual-purpose machine gun also covered part of the zone of advance.13

In the center, about thirty yards beyond the tunnel, there was a large underground

Japanese points of resistance: Beached Seaplane

Japanese points of resistance: Rifle Pits

shelter, and about thirty yards farther on, six rifle pits connected by a trench. Squarely across the King’s Wharf road, a little south of the middle of the island, was a longer trench with eleven rifle pits.14

Between noon and 1400 the advance passed through one of the most heavily defended areas on the island. On the lagoon shore at the base of King’s Wharf, along the east-west highway, and along King’s Wharf road were buildings and tons of fuel and ammunition used by Japanese aviation personnel. A group of hospital buildings was situated near the lagoon at the base of the wharf. Under coconut trees along the ocean shore at the right were four machine gun emplacements supported by ten rifle pits, the whole group being protected on the east and west flanks by double-apron wire running inland from the water across the ocean-shore road.15

One after another, all of these positions were overrun. On the left Detachment Z of the 105th Infantry moved steadily along the lagoon shore, wiping out trenches and emplacements with the help of one medium tank. Combat engineers using TNT blocks were also employed. By the close of the day the detachment unit had advanced from six to seven hundred yards east of King’s Wharf, suffering only six casualties.16 In the center and on the right of the line, Company E met with equal success. Moving slowly but steadily forward, by 1700 it had pushed some 1,000 yards east of Yellow Beach. Tank-infantry coordination was much improved over that of the previous day. Infantry troops pointed out enemy strong points to their supporting tanks, covered them as the tanks moved in for close-range fire, and mopped up the positions once the tanks had withdrawn or moved forward.17 Meanwhile, in the rear areas, Company A joined Company F at 1300 in the vicinity of the West Tank Barrier and proceeded to mop up stranded enemy riflemen in that area.18

The day’s advance had wrested from the Japanese their long-range radio receiving station, a heavily revetted, seventy-eight by thirty-three foot underground building at the south edge of a cleared rectangular area east of King’s Wharf. Other installations captured or destroyed left the main area of enemy military positions entirely in American hands.19 When action ceased about 1700, all Japanese resistance from Red Beaches to Stone Pier had been eliminated with the exception of a few isolated snipers.20 Total U.S. casualties for the day were even fewer than on the previous day—eighteen killed and fifteen seriously wounded.21 Still ahead lay the East Tank Barrier system, resembling that on the west and designed primarily to stop an assault from the east.

The job of continuing the next morning’s attack would not fall to McDonough’s battalion, which had carried the main burden of advance from Yellow Beach to Stone Pier. Shortly after the day’s fighting had ceased, the 2nd Battalion was ordered into reserve by General Ralph Smith. At the same time, Colonel Hart’s 3rd Battalion was ordered to relieve the 2nd, commencing at daylight on 22 November, and to attack eastward vigorously, commencing at 0800.

Hart was directed to employ, as the situation dictated, Companies A and C of the 193rd Tank Battalion, the 105th Field Artillery Battalion, and whatever naval gunfire and aerial support he required. This relief was approved by General Holland Smith, who had by that time come ashore and was with the division commander.22

The Second Night

As night closed down on the second day’s fighting on Butaritari, the supply situation was still unsatisfactory. Earlier in the afternoon Colonel Ferris, the 27th Division’s supply officer, had reconnoitered Yellow Beach and discovered that only amphibian tractors could negotiate the reef, that vehicles were being drowned out when they struck potholes created in the reef shelf by naval shells, and that pallets were being dunked as they were pulled off landing craft at the edge of the beach. Also, the beachhead itself was so cluttered with foxholes, tree trunks, and other obstacles that it was highly unsatisfactory as a point of supply. Meanwhile, Admiral Turner had ordered all ships excepting Pierce to unload on Yellow Beach, with the result that many landing craft that might otherwise have been unloaded on Red Beaches were tied up in the lagoon unable to dump their loads because of adverse hydrographic and beach conditions. Ferris consulted with Admiral Turner late in the afternoon on board the flagship Pennsylvania, and the admiral approved using Red Beaches as much as possible until conditions on Yellow Beach had improved. A request to permit night unloading was denied since Turner had already ordered his ships to put to sea during the hours of darkness.23

Ashore, Company A was ordered to relieve at 1630 the advanced elements of Company E and Company G on the front line. The latter withdrew to the lagoon shore west of Company A and dug in. A little later Company E retired to a line about 300 yards west of the Stone Pier road. In the center of the forward line Company A established its perimeter and to the north, along the lagoon shore, was Detachment Z, 105th Infantry.24

To the rear, Company B spread out to cover the West Tank Barrier. In an effort to prevent the indiscriminate firing that had characterized the previous night, orders were passed out to the troops to use hand grenades instead of rifles. About a hundred grenades in all were thrown from Company B’s perimeter during the night. Next morning five dead Japanese were found lying beyond the perimeter, all apparently killed by grenade fire. Then, just before the men withdrew from their foxholes, they killed two more Japanese by machine gun fire directed at surrounding tree tops.25

Early in the morning hours a sentry on the lagoon shore threw the troops in that area into a brief fright by reporting the approach of landing craft carrying Japanese reinforcements. “There are 200 Japs out there,” he claimed as he aroused Colonel Durand and Colonel McDonough in their foxholes. The two officers got up and reconnoitered the beach, talking in loud voices to avoid being shot by their own men. The boats proved to be American, and the “200 Japs” an illusion.26

The Third Day: Capture of the East Tank Barrier

Well before nightfall on the second day of fighting General Ralph Smith had requested permission to use the 3rd Battalion, 165th Regiment, which was still held in reserve against the possibility of being employed at Tarawa. Since the situation on that island had improved considerably during the day, his request was granted at 1705.27 The 27th Division commander immediately ordered Colonel Hart to leave his reserve area at daylight on the 22nd and move to the relief of the 2nd Battalion facing the East Tank Barrier system. At 0800 the 3rd Battalion, aided by light and medium tanks as well as artillery, naval gunfire, and carrier-based air support, was to attack vigorously to the east. All command posts were to be moved forward to a point near Yellow Beach where closer control could be exercised.28

In conjunction with the continuation of the drive eastward, an expedition under Major Herzog would set out in LVTs early in the morning for Kuma Island to intercept any Japanese who might seek refuge there. Another party was to attempt an amphibious encirclement, going through the lagoon to a point east of the front line and establishing there a strong barrier line across the narrowest part of the island to stop any Japanese fleeing eastward from the pressure of the 3rd Battalion.29 Meanwhile, harassing artillery fire was to be directed into the eastern end of the island from time to time.

Commencing at 0600, 22 November, the 3rd Battalion moved along the island highway in column of companies toward Yellow Beach. Elements of Company K led the column, followed by a platoon of tanks. Company I, the battalion’s antitank platoon, the headquarters and headquarters company, two platoons of Company M, medical units, and Company L followed in that order.30 As the column passed along Yellow Beach, approximately thirteen medium and light tanks and some engineer units fell in. Beyond King’s Wharf, Company K swung to the right as far as the ocean, while Company I filled the area at the left to the lagoon. Together they moved ahead in a skirmish line, all other elements being in reserve.31

At 0700 artillery on Ukiangong Point commenced shelling the East Tank Barrier, while Company A and Detachment Z, 105th Infantry, withdrew. From then until 0820 artillery fired a total of almost 900 rounds. The 3rd Battalion’s line moved swiftly ahead across the area taken on the previous afternoon but abandoned during the night. At 0820, as the artillery preparation was lifted, the tanks and infantry moved against the enemy. By 0915 the first 250 yards had been traversed with only light opposition, but resistance became more stubborn as the forces reached the road running south from Stone Pier.32

The first mission of the tanks was to shell the buildings ahead of them while the infantry grenaded surface installations and small shelters. The infantry-tank tactics that had been developed in the two preceding days for the reduction of large shelters were employed. As the infantry approached air raid shelters, tanks opened

up with their 75-mm. guns, knocking the shelters out as the infantry line continued on. Surface structures and smaller shelters were disposed of with hand grenades.33

At the ocean end of the Stone Pier road, and along the shore east of it, Company K came upon a series of rifle pits and machine gun nests with one 70-mm. howitzer position, all abandoned by the enemy.34 At 0945, as the barrier defenses came within range of the tanks, field artillery resumed its fire, first on the clearing and then to the east of it. After twenty-five minutes the shelling from Ukiangong Point ceased.35 The 105th Field Artillery Battalion then began moving forward to a new position closer to the front while tanks and troops entered the zone just shelled.36

With the 3rd Battalion’s attack moving steadily eastward, Colonel Hart, as previously planned, sent a special detachment to cut off the enemy from retreat to the eastern end of Butaritari. For this mission two reinforced platoons of Company A, which had only that morning been relieved from its position in the line, were sent with additional reinforcement of one section of light machine guns and one platoon of heavy machine guns from Company D. This detail, under command of Captain O’Brien, embarked at 1100 in six LVTs on a three-mile run across the lagoon to a point on the north shore well to the east of the East Tank Barrier. Around noon Captain O’Brien’s men landed without opposition and set up a line across the island. Ten natives encountered near the beach informed the captain that the remaining Japanese were fleeing eastward across the reef to Kuma.37

The longer U.S. amphibious move to Kuma Island was made by a detail under Major Bradt. This group, in ten LVTs, was guided to Kuma by Major Herzog, who had reconnoitered that island the day before. At 1400 nine of the amphtracks landed without opposition in the vicinity of Keuea, about a mile from the southwestern tip of the island. The enemy on Butaritari was now entirely cut off from retreat.38

Meanwhile, tanks and infantry were moving upon and through the East Tank Barrier. Although more heavily fortified than the West Tank Barrier, this strong defensive system offered no opposition whatever. The enemy had apparently abandoned the barrier during the night. Only a few dead Japanese were found, evidently killed by earlier bombardment, in the barrier system.39

The Advance Beyond the East Tank Barrier

After passing through the tank barrier system, troops of the 3rd Battalion did not pause, but pushed eastward. Tanks were operating 200 to 300 yards east of the barrier in the barracks area between the highway and the lagoon as early as 1042. Two hours later, while men from Company A were forming a line across the island neck, tanks had reached a clearing about 800 yards short of that line, and the two forces were in communication.40

Map 7: Securing Makin, 22-23 November 1943

Map merged onto previous page

It was believed that the Japanese remaining between these two forces would be trapped. In fact, no such event took place. By the time the 3rd Battalion had reached Company A’s barricade line at 1330, they had encountered no opposition. Either the enemy remnants had evaded discovery or had slipped east of the island’s neck before noon when Company A had landed from its LVTs. The only sign of life in that area occurred shortly after the junction of forces when about three hundred natives emerged to be taken under custody by the American soldiers and escorted outside of the line of advance. After a short rest the 3rd Battalion pressed forward again, while the Company A platoons and their attached units went to the rear.41

At this point General Ralph Smith, in pursuance of the original plans, assumed full command of the island forces at 1510.42 Shortly thereafter he was ordered to reembark the 1st and 2nd Battalions, all medium tanks, all except five light tanks, and all naval gunfire and air liaison parties the next morning (23 November).43

Beyond the narrow neck of the island where they had joined forces with the Company A detachment, the 3rd Battalion advanced some 9,100 yards, stopping about 1645. With Company I on the right, Company K on the left, and Company L in the rear, the battalion dug in for the night in perimeter defense.44

Ahead lay about 5,000 yards of Butaritari Island still unsecured by the attacking forces. The escape of any enemy that might remain in that area across the reef to Kuma was barred by Major Bradt’s detachment on that island. From his positions at the southwestern end of Kuma he could effectively cover any crossing and in fact did repulse two enemy attempts to land on Kuma during the night.45

The day’s activity had been easy, except for the heat and the tangled tropical growth through which the 3rd Battalion had had to advance. Enemy resistance in the area of the East Tank Barrier and eastward had been nominal. At the day’s end Admiral Turner announced the capture of Makin “though with minor resistance remaining” and congratulated General Ralph Smith and his troops. All that seemed to remain was to mop up a now thoroughly disorganized enemy trapped in the extreme northeastern tip of Butaritari.46

The Last Night

After a wearisome but generally unopposed day’s advance, the 3rd Battalion dug in in a series of separate company perimeters, stretching across the width of the island in a line of about 300 yards in length.47 At the north Company I covered the lagoon shore, the main highway, and about one half of the island’s width. In an oval clearing in the center of the island two small ponds intervened between Company I and Company K, which set up a perimeter covering the distance from there to the ocean shore. West of these two companies in a long, narrow oval running all the way across the island was Company L, facing west. Spaced along this entire position were the light machine guns of the various company weapons platoons, and

the heavy machine guns of Company M. The battalion antitank guns were placed at the point where the lines of defensive positions crossed the highway. One pair faced to the west along the road while the second pair faced to the east. The two antitank gun batteries were covered by heavy machine guns of the antitank platoon and a few riflemen. The men from Company M covered their own guns, while riflemen from the three rifle companies protected the remainder.

No very serious effort was made to establish a strong perimeter. No thorough reconnaissance of the ground just ahead was made, although about an hour and a half elapsed between the time the battalion began to dig in (1645) and sunset (1818) and another hour and a quarter remained before total darkness set in (1931).48 During the heat of the day’s activity most of the men had dropped their packs to the rear, including their entrenching tools. Foxholes were therefore shallower than usual. In some cases men did not even bother with them. Instead, they dragged coconut logs into place and built themselves barricades above ground. The truth is that very few, if any, of either officers or men entertained serious notions that there was much danger from the remnant of Japanese facing them. This opinion was most succinctly expressed by 1st Lt. Robert Wilson who later said, “Many of us had the idea there were no Japs left; when the firing began, I didn’t believe it was the real thing.”49

The first effort of the enemy to penetrate the perimeter occurred shortly after dark. Following close on the heels of a party of natives who had safely made their way into the American lines, a group of Japanese advanced close to the line, imitating baby cries as they came. The ruse was recognized by a member of the engineer detachment, who opened fire with his machine gun killing about ten Japanese. Thereafter until dawn, the night was broken by intermittent fire fights, infiltrations, and individual attacks on the American positions.

This was no organized counterattack or banzai charge such as occurred later on Saipan. Rather, it was a series of un-coordinated small unit, sometimes individual, fights. In an effort to unnerve the Americans, the Japanese periodically set up a tom-tom-like beating all over the front of the perimeter. Periodically, also, they would yell or sing, apparently under the influence of sake.50 They came on sometimes in groups and sometimes singly. A number of them filtered into the American lines, and their fire engaged the perimeter from both sides. The brunt of the attack fell on a few machine gun and heavy weapons positions that were covering the front from the right and left of the line. To the crews of these weapons the attack naturally appeared formidable indeed. Actually, although from three to four hundred men of the battalion were under Japanese mortar, machine gun, rifle, and grenade fire from time to time, the enemy onslaught broke and disintegrated around these relatively few positions held down by the heavy weapons and machine guns on the front. Those who were only slightly to the rear of the guns were in the position of uneasy onlookers, bound by the character of the defense to take relatively little hand in the repulse given the enemy.

When daylight finally came it was apparent that the night’s attack had been both less massive and less deadly than it had seemed while it was going on. Fifty-one enemy dead were counted in front of American guns, although more were later found east of these positions. Some or all of these may have been wounded during the night’s activity and dragged themselves away from the perimeter to die. American casualties for the night came to three killed and twenty-five wounded.51

A few of the enemy also had tried to escape from Butaritari over the reef to Kuma. At midnight about ten came upon the defense line set up by Major Bradt’s detail from the 105th Infantry and were either killed or wounded while making an effort to cross it. Unless some had previously escaped beyond Kuma to the other northern islets of the atoll, the last remnants of the original Japanese forces were destined to be pinched off on 23 November, D plus 3.52

Mop-Up

The sixty-odd Japanese killed during the night represented the bulk of the remaining enemy soldiers on Butaritari. All that was left to be secured was the eastern extremity of the island, including Tanimaiaki Village, and the few scattered enemy left here were mostly labor troops and airmen.

The American attack was launched at 0715 with Company I in the advance. As many men as possible rode on the five light and sixteen medium tanks that had been sent up earlier to spearhead the drive.

Behind them, Company K on the left and Company L on the right formed a skirmish line across the island. Still farther to the rear came the men of Company B from the 1st Battalion, as reserve support. With the left flank rode a special detail equipped with loudspeakers through which nisei interpreters were to broadcast appeals for surrender to whatever enemy troops might be left in Tanimaiaki Village. About 1015 it was discovered that some Japanese had moved across the rear of the advance unit and cut its wire. Colonel Marshall, who was in temporary command of the nisei detail, was ordered to return to the rear with a message requesting Colonel McDonough to get his support element forward. As his jeep started back from the front line it ran into an ambush that the Japanese had set up for about 300 yards along the road, somewhat more than a half a mile to the rear. At that point a support element making its way forward arrived on the scene and cleared out the ambush in a short, sharp fight. This was the last tactical encounter on Makin.53

By 1030 advanced elements of the 3rd Battalion had reached the tip of Butaritari, and organized resistance was declared to be over.54 Only a few Japanese had been encountered on the way and these had been quickly silenced. An hour later General Smith radioed to Admiral Turner, “Makin Taken! Recommend command pass to Commander Garrison Force.”55 Except for minor mopping-up activities, the operation was over.

At 1400 the 2nd Battalion under Colonel McDonough started to board Pierce from Red Beach 2.56 At 1630 Admiral Turner ordered General Smith to turn over command

of the island to the garrison force commander, Col. Clesen H. Tenney, the following day at 0800.57 From 1900 to 2120 that evening and again during the next morning, the 27th Division staff and the improvised staff of Colonel Tenney conferred. It was decided to leave on the island a considerable quantity of communications equipment already in operation, with the personnel to operate it. All the LVTs were left, and with them a Navy boat pool of nine officers and 1,943 enlisted men. Many of the trucks, bulldozers, and Jeeps were also to remain.58

During the morning Major Mahoney’s 1st Battalion went aboard Calvert, while other detachments embarked on other transports. At noon the special detail returned from Kuma and began to board Leonard Wood, following the headquarters staff.59 The 3rd Battalion under Colonel Hart was left behind to assist and protect the construction forces. Also remaining for the time being on the island were Battery C, 105th Field Artillery; one platoon of Company C, 193rd Tank Battalion; the LVT detachment from Headquarters Company, 193rd Tank Battalion; the Collecting Platoon and the Clearing Company and surgical team, 102nd Medical Battalion; Company C, 102nd Engineers; the 152nd Engineers; Batteries K and L, 93rd Coast Artillery (AA); Batteries A, B, C, and D, 98th Coast Artillery (AA); and the Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, 165th Infantry.60

The remainder of the troops that had fought on Butaritari were boated and ready to sail by noon of 24 November. A short delay caused by the report of nearby enemy planes held up the convoy until 1400, but at that time the ships finally shoved off for the more inviting shores of Oahu.61 The capture of Makin was history.

Profit and Loss

Reckoned in terms of the casualties sustained by the 27th Division, the seizure of Makin at first glance appears to have been cheap. Total battle casualties came to 218, of which 58 were killed in action and 8 died of wounds. Of the 152 wounded in action and the 35 who suffered nonbattle casualties, 57 were returned to duty while action was going on.62 At the end of the fighting, enemy casualties were estimated to come to 550 including 105 prisoners of war, all but one of whom were labor troops.63 Later mopping-up activities accounted for still more, and in the end the total enemy garrison, none of whom escaped, was either captured or killed. Thus, a total of about 300 combat troops and 500 laborers was accounted for at Makin.64

In view of the tremendous superiority of American ground forces to those of the enemy and the comparatively weak state of Japanese defenses, the ratio of American combat casualties to those of Japanese combat troops was remarkably high-about two to three. In other words, for every three Japanese fighters killed, two Americans were either killed or wounded. Thus the cost of taking Makin was not quite so low as it had first seemed.

Naval casualties incident to the capture of Butaritari were much higher than those of the ground forces. During the preliminary

naval bombardment on 20 November, the battleship Mississippi had a turret explosion resulting in the death of forty-three men and the wounding of nineteen others. More important was the sinking of the escort carrier Liscome Bay. On the morning of 24 November she was operating about twenty miles southwest of Butaritari in company with two other escort carriers, all under command of Rear Adm. Henry M. Mullinix, USN. At 0513 Liscome Bay was hit amidships by one or more torpedoes fired from an undetected enemy submarine. Her bombs and ammunition exploded and within twenty-three minutes she sank. Fifty-three officers, including Admiral Mullinix, and 591 enlisted men were lost and many others seriously wounded and burned.65

This sinking, occurring on D plus 4, gave point to an argument repeatedly put forth in naval circles that in amphibious operations time was of the essence, that ground operations prolonged beyond the time compelled by absolute necessity constituted an unacceptable risk to naval shipping and to the lives of naval personnel. Liscome Bay when torpedoed was standing by to furnish air cover for Admiral Turner’s attack force on its voyage back to Oahu. Had the capture of Makin been conducted more expeditiously, she would have departed the danger area before 24 November, the morning of the disaster.

General Holland Smith was later of the opinion that the capture of Makin was “infuriatingly slow.”66 Considering the size of the atoll, the nature of the enemy’s defenses, and the great superiority of force enjoyed by the attacking troops, his criticism seems justified. It is all the more so when to the cost of tardiness is added the loss of a valuable escort aircraft carrier with more than half the hands aboard.