Chapter 16: Kwajalein Island: The Third Day

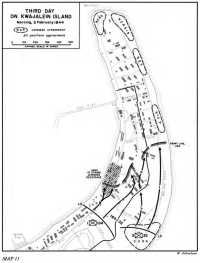

From the line of departure of 3 February to the northeastern extremity, Kwajalein Island curved and narrowed for about 2,000 yards.1 Halfway along the lagoon shore was Nob Pier, while on the ocean side the distance around the outside of the curve from Corn Strong Point to Nathan Road, which extends across the island from Nob Pier, was approximately 1,500 yards. The island was over 600 yards wide where the day’s advance was to start but narrowed to almost 300 yards at Nathan Road.

Nathan Road was the day’s first objective. At the left, between the lagoon and Will Road, the band of buildings that had begun near Center Pier continued unbroken. Another concentration of buildings lay in the middle of the island some 230 yards north of Nora Road, in a diamond-shaped area of approximately 250 by 350 yards. Here, according to a captured enemy map, were the headquarters, communications center, shops, and other installations of the Admiralty section, as distinguished from those related to the airfield. Except along its southeastern side, the area of these buildings had been cleared, and a loop of secondary road connected it with Will Road. The third aggregation of enemy buildings to be encountered in the area before Nathan Road was the southern section of the heavily built-up area that stretched to the end of the island. Buildings extended, within a grid of cross-island and north-south streets, from a wooded area some 500 yards south of Nathan Road to the northern highway loop. Halfway between Nora and Nathan Roads, among the southernmost buildings of this northern aggregation, was Noel Road, which also linked the two main island highways.

Photographic reconnaissance of the part of Kwajalein Island yet to be captured on 3 February had been limited by the heavy woods. Coastal installations stood out most clearly, and these appeared to be considerably stronger on the ocean side. South of Nathan Road two concentrations had been detected along the ocean shore. The first, organized around 300 yards of trench, lay parallel to the shore, 600 to 900 yards beyond Corn Strong Point, from which the right elements of the 32nd Infantry were to start. In the narrow area between the trench and the ocean, two covered artillery positions and five pillboxes were anticipated. Immediately beyond the trench the second concentration, designated as Nap Strong Point, consisted of nearly 400 yards of organized positions in which three heavy

Map 11: Third Day on Kwajalein Island, Morning, 3 February 1944

and five light machine gun emplacements had been observed and at least one pillbox was expected.

The Plan for 3 February

The two regiments faced, on what was expected to be the last day of attack, the island’s area of densest construction. Estimates of remaining Japanese fortified positions other than those along the shores had been made from information supplied by Japanese prisoners and the captured Marshalls natives but, although the latter had warned of reinforced concrete shelters among the other structures in the northern portion of the island, their actual number and strength was not anticipated.2

Progress on Kwajalein Island on 3 February required coordinated movement through strong defenses and heavy concentrations of enemy troops. The axis of advance would turn gradually from northeast to north, as the troops advanced along the narrowing curve of the island. Except for a brief loop to the east to bring all of the Admiralty area into the 184th Infantry’s zone, the regimental boundary continued along the middle of the island. To make the swing along the island’s curve while maintaining alignments of the two regimental fronts demanded greater rapidity of advance in the 32nd Infantry zone.

General Corlett’s plan for 3 February anticipated rapid occupation of the rest of the island. It called for a “vigorous attack,” beginning at 0715.3 At 0700 a ten-minute artillery preparation would begin in which the eighteen heavy regimental mortars would supplement the division artillery in hitting Kwajalein Island, while the naval gunfire was being directed on Burton Island.4 During this preparatory fire, the 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry, was to pass through the 2nd Battalion and jump off from the line of departure at 0715, Company A on the right, Company B on the left, and Company C in reserve. Each company was to have a detachment of the 13th Engineers, a platoon of heavy machine guns, and one 37-mm. antitank gun. The engineers were to prepare the charges to blow up enemy shelters. Each of the leading companies would be supported by four medium tanks, and in addition two light tanks would operate with Company A on the right.5

The 32nd Infantry’s attack was to be carried by the 3rd Battalion, Company I on the right along the ocean shore, Company K on the left between Wallace Road and the regimental boundary, and Company L mopping up behind Company K. One platoon of medium tanks and two light tanks were to support the assault, with a second platoon of mediums in reserve. A destroyer would furnish naval gunfire on call, and air support would continue as on the previous days. The 1st Battalion was to pass through the 2nd Battalion and follow in close support, covering any gaps in depth that might develop.6

The Attack of the 32nd Infantry

The execution of the plan began at 0705, with the ten-minute preparatory fire. The troops jumped off on schedule while the artillery continued to fire ahead of the troops in a creeping barrage. When the 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry, had come abreast of the 32nd Infantry, the latter moved forward across a hundred yards of

brush to a woods that had been under bombardment. No fire was received until the troops had pressed though the woods for another two hundred yards. Only ruins of a few structures were found there, but about 150 yards to the northwest was the corner of the Admiralty area, where a large concrete pillbox partly commanded the 32nd Infantry’s route of advance. Protected by the trees, most of Companies K and I passed beyond this installation, while Company K’s support platoon and two of the medium tanks turned left to attack it. Driven into the open by demolition charges and 75-mm. shells, the enemy occupants ran out one by one to seek shelter among nearby buildings. Lt. Col. John M. Finn, executive officer of the 32nd Infantry, and Capt. Sanford I. Wolff, observer from the 33rd Infantry Division, shot them as they ran. The Japanese buildings on the left flank could not be cleared unless Company K moved into the field of fire of Company A, 184th Infantry, which was just beginning to push along the southwestern edge of the Admiralty area. A local arrangement was therefore made by Colonel Finn and 1st Lt. Norvin E. Smith, commanding Company A. Company L, 32nd Infantry, with the support platoon of Company A, 184th Infantry, would mop up the building area by house-to-house action; the remainder of Company A would continue north, and in so doing protect Company K’s left flank. Company L would also maintain connection between the two battalions. The arrangement in effect modified the regimental boundary.7

Enemy positions in the 32nd Infantry’s zone were not only scattered but also such as to enable rapid movement without detailed search of all cover. The more thorough mopping up could be done by support elements. General Corlett ordered the 32nd Infantry to “keep smashing ahead.”8 The growing gap between the leading elements of the two regiments was, however, a cause of increasing concern to Colonel Finn. By shortly before noon the right wing had pushed through the first aggregation of defenses along the ocean shore and had reached Noel Road. The 32nd Infantry’s line bent southwest from that point to a point about two hundred yards north of the Admiralty area. The 184th Infantry’s lines extended from the southwestern edge of the Admiralty area southwest to the lagoon shore about a hundred yards from Nora Road.9 Between the two regiments there was a vertical gap including most of the Admiralty area. To care for this and any other strain on the lengthening gap between the two regiments, the 1st Battalion, 32nd Infantry, had been sent forward at 0900. Early in the afternoon Company B relieved Company L, which had been mopping up in the Admiralty area; Company L then moved north to fill in the vertical gap; Company C filled in south of Company L along the gap; and Company A, in reserve, stood ready to shift to the south of Company C should the gap become longer.10

Had the enemy defense been coordinated, the long spearhead on the eastern side of the island might have been struck effectively from the west, but actually the danger most apparent to the 32nd Infantry’s command was that of fire from the zone of the 184th. In fact, small arms fire from the 184th’s zone did fall from time to time east of the Admiralty area.11 As the 184th Infantry swung north, the line of fire could increase this risk.

The Morning Action in the 184th Infantry’s Zone

The division plan for 3 February had envisioned heavy opposition in front of the 32nd Infantry and very little of consequence facing the 184th. Within thirty minutes of the move northeastward, however, the 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry, had run into the first of the many surprises it was to encounter during the day.

The Early Phase of the Attack

After passing through the 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, and continuing into the area temporarily penetrated on the previous afternoon, the 1st Battalion had reached the line of departure at 0715 in accordance with orders.12 The advance was started without supporting tanks, which had failed to arrive because of a misunderstanding about their rendezvous with infantry guides.13 In the first 150 yards Company B, along the lagoon, and Company A, at the right, advanced through rubble and broken trees west of Nora Road without more than scattered rifle fire from Japanese riflemen and occasional light machine gun fire from pillboxes. Their momentum carried them on for another seventy-five yards with such rapidity that the prospects for swift advance seemed excellent. Company B cleaned out an air raid shelter with grenades and shot down fleeing Japanese wearing arm bands like those of the American troops. Both companies were advancing over ground that had been under American mortar fire just before the jump-off. At 0806 enemy opposition was reported to be weak.14

Then Company B looked ahead at a sight for which no warnings had prepared them. As far as could be seen along either side of Will Road—along the lagoon and in the Admiralty area—amid dust and smoke, lay the dense ruins of frame structures, the shattered walls of concrete buildings, some of them very large, and a confused tangle of trees and rubble. Interspersed among the wrecked buildings were several underground shelters with great earthen mounds above them, and concrete blockhouses, intact and active. At the nearer edge of this formidable barrier was a great, round blockhouse of reinforced concrete; fifty yards beyond the blockhouse, among the buildings, two huge shelters could be seen side by side. Thick, reinforced concrete, steel plates, logs, and a blanket of sand several feet thick had enabled them to withstand artillery fire without significant damage. Smaller bunkers at their right were part of the system of organized defensive positions that the men of Company B had to reduce. As the line approached the blockhouse, enemy fire strengthened.

The Split in Company B

Capt. Charles A. White, the Company B commander, had placed two rifle platoons in line at the start of the morning’s attack. The blockhouse was almost entirely in the zone of the 1st Platoon, on the right. Just to the east of the built-up position lay a long, open corridor where a building had once stood. All that remained was the concrete floor.15

The company had come up to the blockhouse

with no supporting weapons. Before any attack was made, it was decided to wait until the heavier pieces could be brought to bear. 1st Lt. Harold D. Klatt, commander of the 1st Platoon, upon receiving a 37-mm. antitank gun, the first heavy weapon to be brought up, moved it to the entrance of the blockhouse, and the crew fired several rounds into it. Nothing seemed to happen as a result of these shells, so the gun was withdrawn. While the 1st Platoon had been working on the position from the right, the 2nd Platoon, under 2nd Lt. Frank D. Kaplan, had meanwhile swung more to the left toward the lagoon, partly to pass the blockhouse and partly to follow the curve of the lagoon shore.

After his 1st Platoon had withdrawn its antitank gun, Lieutenant Klatt decided to bypass the position to the right and leave it for the tanks and reserve company to finish when they came up from the rear. To keep from being too badly mauled by the enemy still in the blockhouse, however, the platoon had to take maximum advantage of cover. Lieutenant Klatt ordered his men to move by bounds, swinging just to the right of the open corridor provided by the demolished building’s floor. Several things happened now almost simultaneously. In the course of moving forward the 1st Platoon broke up into small groups and thus became a whole series of more or less independent bodies, each engaged in some small mission; the Japanese in the blockhouse, seeing that they were about to be bypassed, evidently decided to make some attempt to get out and back to other positions in the rear; and Lieutenant Klatt discovered that he was actually lost in the piles of rubble and debris that littered the whole area. Although the men of Lieutenant Kaplan’s 2nd Platoon were not more than twenty yards away on a straight line, they could not be seen; nor could Lieutenant Klatt’s operator reach them on his radio.

The men of the 1st Platoon gave their full attention to their own situation. Their most immediate problem seemed to be the elimination of the Japanese who were trying to escape from the blockhouse. Wherever they could, the men took up firing positions and cut down the enemy, one by one, as they appeared at the entrances. Elsewhere, Japanese in trees, in numerous supporting pillboxes and shelters, and even under and behind the rubble piles, began a counter-fire on the little groups. Some of the platoon broke off fire at the blockhouse and began to search through the debris for the sources of the harassment. Others crouched in shell holes or behind the piles of rubble trying to find the enemy from the relatively protected vantage points. Meanwhile, medium tanks had at last moved up the road from the rear and approached the blockhouse. There they stopped and sat idly since neither Lieutenant Klatt nor any of his men could get to them to tell the crews what had to be done.

The truth is that it would probably have made little difference at this point whether the infantrymen could have reached the tanks. The improvised telephone sets that had been installed on the rear of the tanks for the Kwajalein operation were usually shorted out because their boxes were inadequately waterproofed. The only sure way for Klatt to have contacted a tank would have been to rap on its outside with a rifle butt. This would have entailed stopping the tank and opening its hatch while the infantry and tank commanders conferred. In a close-fire fight such as this, the danger to all parties concerned would have been too great to warrant the risk.16

Tank-infantry attack amid the rubble of the fortifications on Kwajalein. A 37-mm. antitank gun being brought into position

Infantrymen, supported by M4 tanks, prepare to attack

While the 1st Platoon had been working around the right of the big blockhouse, the 2nd Platoon had moved to the left and then halted to reorganize and wait for the 1st Platoon to re-establish contact. Ahead of his men, Lieutenant Kaplan could see nothing but debris. From the littered ground and from a small wharf that jutted out into the lagoon, rifle fire was being received in fairly heavy volume. To eliminate this, the platoon commander decided to call in artillery fire, but he asked the artillery forward observer to confine it, if possible, to the area between the lagoon and the road. He did not know exactly where the 1st Platoon was, but suspected it might be ahead of him. When the fire was finally brought in, some of it spilled across the road and began bursting within 20 to 25 yards of Lieutenant Klatt’s men. Klatt sensed that the bursts were from American artillery, and, as they appeared to be getting closer, he yelled for his men to pull back behind the blockhouse. In one case four men had just left a crater when the exact spot on which they had been lying was hit by a shell. The 1st Platoon reorganized and took up a position approximately on a line with the blockhouse.

The Second Attack

More than an hour had elapsed since the company first entered the area, and battalion headquarters was beginning to notice that there had been no advance in the Company B area. Headquarters called Captain White so frequently for information that the company commander finally left his command post to join Lieutenant Klatt in the debris ahead. Before he left for the front line he committed part of his 3rd Platoon along the lagoon shore where, according to an air observer, some Japanese were gathering for a counterattack.

Upon his arrival at the front lines, Captain White reorganized his whole line, bringing up machine guns to cover the gap between his two assault platoons and lining up the tanks for a coordinated drive against the numerous shelters that lay ahead. Because of the failure of previous tactics against these positions, the tanks were now to precede the infantry, moving slowly and firing all their weapons at targets of opportunity. The infantry, under cover of this fire, would move directly up to the shelters and throw in satchel charges.

Company B’s second attack began at approximately 0945. Two hours and a half had elapsed since the initial effort had begun, and no appreciable gains had been registered since the company had first reached the fortified area.

The new tactics proved unsatisfactory from the first. The fire from the tanks was directed at random and proved to be more dangerous to the infantry than the action of the enemy. When Captain White sought to coordinate the work of tanks and infantry, the problem of communications again became a major one. The phones on the rear of the vehicles would not work, and the company commander had to scramble up on the top of the turret and beat a tattoo with the butt of his weapon to get the attention of the men in the lead tank. By the time he had told the commander what he wanted, the whole platoon of tanks had become separated from the infantry, and each tank was proceeding on an independent mission. For the time being, the value of the tanks was lost to the infantry. Moreover, the two assault platoons, pushing through the rubble, had themselves once more become separated and all coordination between them was lost.

On the left, between the highway and

the lagoon, all of the 2nd Platoon and part of the 3rd were driving forward steadily. Each pile of debris was investigated, blown up with satchel charges, and then set afire. Working in small groups, the men on the left moved forward one hundred yards in an hour. Conditions were such that two details working less than ten yards apart did not know of each other’s presence. The high piles of splintered wood and smashed concrete, together with the dense smoke that now covered the area, isolated and split up the various actions. Japanese who fired from under the debris, sometimes at almost point-blank range, had to be routed out.

On the right, Lieutenant Klatt’s platoon had also separated into small groups to carry the fight to the shelters and piles of debris in its area. Captain White, after his episode with the tanks, tried to re-establish a solid company front and sent his runner to Lieutenant Klatt with orders to close the gap between himself and Lieutenant Kaplan. Klatt replied that this was impossible until the big blockhouse, now to his left rear, had been cleaned out. White, upon receiving this message, ordered his runner to take a detail from company headquarters and see if he could knock out the blockhouse. The runner, together with the company bugler and the mail orderly, moved up with two satchel charges and threw them inside. There was a terrific explosion, but there seemed to have been little damage done to the position. The company’s executive officer reported that there were many signs of Japanese still inside, and a platoon of Company C was brought forward to work on the position and keep it under surveillance. Enemy soldiers were still being killed there late in the evening as they tried to wriggle out and escape.

Captain White had followed the action at the blockhouse by again trying to get the two assault platoons of his company in direct contact. He moved up the road and found Lieutenant Kaplan. After failing once more to get satisfactory coordination in tank-infantry efforts, the company commander began the task of extending the 2nd Platoon’s right flank to meet Lieutenant Klatt’s left. Between Will Road and the point at which he judged the 1st Platoon’s right elements to be, there were three large shelter-type buildings, one close to the road and the other two well back from it. The latter were definitely concrete reinforced shelters, but the former could not be identified.

There appeared to be no enemy in any of these shelters, but to make sure a 37-mm. antitank gun was brought forward and placed on the road to bear on the nearest building. It fired several rounds of high explosive and canister, which completely wrecked the structure and set fire to it. Much to the chagrin of the whole company, the building was later found to contain virtually all the sake, beer, and candy that the Japanese had on the island. Only a few bottles of beer were saved.

Meanwhile, without the company commander’s knowledge, a small patrol of the 1st Platoon had reached the farthest inland of the two remaining shelters. Two of the men, Sgt. Melvin L. Higgins and Pvt. Arthur T. Contreras, after taking cover in a shell hole and surveying the two buildings, decided to throw satchel charges in the main entrance and see what would happen. By this time the company had used so many of the charges that it had exhausted the supply in the regimental dump. The company executive officer, however, had brought up several blocks of Composition C, a high explosive, and

members of the company were improvising satchel charges by tying the blocks together and putting them into gas mask carriers. Two of these improvised charges were now made up, and each of the two men ran twenty-five yards over to the entrance, threw one in, and ducked back to the cover of the shell hole. The explosion shook the building but caused no appreciable damage. Another charge was placed with the same apparent lack of effect. As he ran back for cover, however, Higgins noticed two Japanese machine guns between the left-hand building and the road. There seemed to be no enemy around these weapons, but almost directly behind them was a little trench, which made Higgins suspicious. Instead of running over to the guns, he went over to one of two medium tanks nearby, talked the crews into opening their hatches, and pointed out the machine guns. The tank lumbered toward the position. As it did so, a white flag began waving a short distance behind the guns. Nevertheless, the tank opened fire and a few moments later Sergeant Higgins crawled forward and found twelve dead enemy soldiers directly behind the guns in a camouflaged ditch, from which they could have fired at anyone curious enough to approach. The action of the tank had, it appeared, opened the way for a resumption of contact between the two platoons. Without either knowing of the other’s actions, Kaplan and Klatt each sent patrols to find the other. The group from the 1st Platoon consisted of only two men, S. Sgt. Roland H. Hartl and Pfc. Solteros E. Valenzuela. That from the 2nd Platoon was composed of ten men under the command of Sgt. Warren Kannely. Both groups were concerned with the shelter into which Higgins and Contreras had just thrown charges. Neither group knew of the other’s presence.

Sergeant Hartl’s group reached the building first. Hartl came up to the front entrance from the southeast side. The building was, therefore, interposed between himself and Kannely. Hartl and Valenzuela crept up to the entrance, looked in, and saw nothing. Hartl got to his feet, nonchalantly pulled the pin on an offensive grenade, and tossed it in the door. Then the two men sprinted out of sight from everyone around a big pile of rubbish, and Hartl stopped and took a long drink of water from his canteen.

At the moment Sergeant Hartl’s grenade exploded, Pfc. Harold S. Pratt was creeping up on the entrance from the opposite direction with another improvised satchel charge. He had not seen Hartl, nor had Hartl seen him. Only a moment after the grenade exploded, Pratt heaved his charge in the entrance, yelled “Fire in the hole” at the top of his voice, and ducked back toward the point where Sergeant Kannely and his patrol were hiding in shell holes, twenty yards away. At that moment several things happened quickly. The charge exploded. Japanese came streaming out of the shelter at two entrances, shooting rifles, brandishing bayonets, and throwing grenades as they rushed pell-mell toward Sergeant Kannely and his men. Sergeant Hartl dropped his canteen, and he and Valenzuela dove for the shell craters in which the 2nd Platoon’s patrol was hiding. Sergeant Higgins and his group on the opposite side took up fire on the screaming Japanese. For ten minutes the whole area was a melee of struggling men. Grenades were exploding and rifle bullets flying in all directions. One Japanese machine gun opened fire from beyond the shelters and enemy soldiers began taking up the fire from under heaps

A .30-caliber machine gun emplacement on Kwajalein

of wreckage and from trees nearby. The combined action of Kannely’s and Higgins’ groups soon killed all the Japanese who had come from the shelter, but in the process Kannely and two others of his group had been killed and several seriously wounded, including Valenzuela. The remainder were now under heavy fire from enemy machine guns and riflemen. Pratt crawled back to the road and asked Captain White, who was still standing near the wrecked and burning storage house, to send tanks, machine guns, and litter bearers into the area. He explained what had happened. The company commander immediately sent two tanks off the road toward the shelters. The tanks soon drove the Japanese out of their hiding places and silenced the machine guns, but in the process also fired on Sergeant Higgins’ group, which was still hiding on the opposite side of the shelters. Neither Higgins nor any of his men could see the tanks or the machine guns, but they could hear them; and the volume of fire meant only one thing to them, a Japanese counterattack. T. Sgt. Ernest Tognietti, the platoon sergeant, who had now come forward to join Higgins, ordered a withdrawal to a line of machine guns that Lieutenant Klatt had set up forty yards to the south of the shelters. Behind this defensive position, the platoon leader reorganized his platoon and ordered the men to hold.

In the 2nd Platoon area, meanwhile, Lieutenant Kaplan had still been trying to push his men forward on the lagoon side of the road beyond the sake storage house. Because of the debris he had not seen the action involving Sergeant Kannely’s patrol

and was unaware of the casualties incurred there. When the opposition of the Japanese became stronger along his immediate front, shortly after this incident, the platoon leader came back along the road to see Captain White and find out whether he could have more tank support. The company commander informed him of Kannely’s death and of the fact that only two of the ten men sent to the right of the road were left. He advised Kaplan to hold up his attack until the whole company front could be reorganized. It was now 1230. Before Company B could launch a third attack through the area, the whole attack plan for the 184th Infantry was changed.

Action of Company A

At Nora Road, Company A, 184th Infantry, had also found a totally unexpected group of buildings, pillboxes, and shelters through which it moved during sharp fighting.17 Enemy riflemen behind fallen trees and piles of debris kept up a heavy fire as six or more defended points were brought under control. When two medium tanks and one light tank, with one self-propelled 75-mm. howitzer, reported at 0830, they joined in the attack. The company’s progress was more rapid than that of Company B, past whose right wing it continued as far as the Admiralty area. The eight large structures and twelve or more smaller buildings of this area had been thoroughly bombed and shelled, but active blockhouses and shelters were scattered among them. To comb the enemy from the wreckage and clear out the shelters was certain to take a long time and perhaps more than one company’s strength. Company A suffered several casualties as it began the task, although resistance was less determined than that encountered by Company B.18 Company A pushed about a hundred yards beyond the Admiralty area before it was ordered to advance slowly rather than move too far beyond Company B. At its right, Company K, 32nd Infantry, continued to advance and took over a wider front. Company A’s right platoon was pulled back behind the left and Company K moved forward somewhat to the west of the established regimental boundary.19

The Revised Plan of Attack

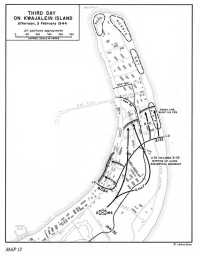

Company B, 184th Infantry, was faced with a situation that it could not handle alone. It could not move ahead, leaving mopping up to supporting units. The enemy was too numerous and too firmly established and the terrain continued to be so badly disrupted that coordinated action could not be maintained. Shortly before noon, the regiment produced a revised plan of attack. The 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, was to move through the right wing of the 1st Battalion and then swing left, taking over the entire regimental zone from a line a hundred yards southwest of Noel Road. The 1st Battalion was itself to swing left and shift the direction of its attack to a broad front parallel to the lagoon.20 This order was modified by a division order at 1225.21 The 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, was limited to a northern boundary that curved from Noel Road to the juncture of the lagoon and Nathan Road. The 32nd Infantry was to take over all the island north of that point, pinching

Map 12: Third Day on Kwajalein Island Afternoon, 3 February 1944

off the 184th’s zone there. The 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry, was to attack toward the lagoon but over a less extended front. By 1330, maneuvers to carry out the new plan of attack were in progress.

Execution of Attack in the 184th’s Zone

At the time when the revised plan of operations was adopted, the enemy was being engaged along an irregular front that extended from the Noel Road line on the ocean side to the northwestern edge of the Admiralty area, and thence westward to the lagoon at a point about a hundred yards north of Nora Road. The 32nd Infantry was three hundred yards nearer Nathan Road than the 184th, the right wing of which was in turn well ahead of its left and able to advance more freely. The 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, which had been mopping up in the rear, moved forward at once, only six hours after being relieved, with Company G at the right, Company F behind G, and Company E at the left.22 The battalion was to march along the eastern edge of the regimental zone to the area in which Company A was operating, to pass through or around Company A, and to swing northwest toward Nob Pier and the lagoon. It expected to reach the northern edge of Company A’s area at approximately 1430. Shortly after the 2nd Battalion moved off in the attack, Companies A and C were to turn west and approach the lagoon with the former on the right. Company B was to serve as the hinge, furnishing fire in front of Company C from the south until Company C itself masked B. Then Company B was to swing around to the lagoon beach.23

As the 2nd Battalion approached the Admiralty area about 1400, a conflagration among its ruined structures made movement through it impossible.24 Company E kept to the left of it; Company G, followed by Company F, went to the right, losing contact. Company E had expected to reach a line at least partly held by Company A. A guide was killed on the way forward, and the company moved uncertainly through the welter to what was thought to be its line of departure. Company A was not there; it had already been pulled back in order to reorganize for its new attack toward the lagoon. A gap between Company A and Company E thus developed directly northwest of the burning Admiralty area. Company G and Company F passed by Company A over ground well east of the regimental boundary, then turned northwest toward their line of departure. When Company G renewed contact with Company E, after at least half an hour, G had lost touch with the left-hand elements of the 32nd Infantry.25

Lt. Col. Carl H. Aulich and the forward echelon of the 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, command post came up to a tentative location northeast of the Admiralty area amid heavy rifle fire, smoke, and confusion. Attempts to coordinate the movements of the 2nd Battalion with those of Company A, with which it was to maintain contact on its left, proved inordinately difficult.26

About 1545 Company A was joined by two medium tanks and Company C by two mediums and two M-10 tank destroyers. The attack was mounted by 1605 on the western edge of the built-up Admiralty area along a three-hundred-yard front,

with Company A’s right wing somewhat south of Noel Road. Ten minutes later the advance toward the lagoon began. From the line of departure to Will Road, a distance of about seventy-five yards, movement was steady and opposition quickly overcome. Will Road was crossed shortly after 1630. The enemy was much more firmly established between the highway and the beach, in pillboxes, blockhouses, and strong shelters. Mortar fire on this area kept the enemy down until the tanks and infantry approached. The coordinated work of tanks, infantry, and demolition teams ran smoothly. At 1800 they were at the lagoon.27

Company C began to mask Company B’s fire about 1630, releasing the latter to re-form on Company C’s left wing, in the vicinity of Will and Nora Roads. Company A received a counterattack from about twenty of the enemy on its right flank, just as its advance was ending, but destroyed the attacking force. There was still no contact with Company E.28

Company E had started its attack before those of either Company G or the 1st Battalion. At 1440 it began moving northwest.29 Somewhat more than half an hour later Company E was reported to have crossed Noel Road, with Company G on its right. Two medium and two light tanks, taken over from the 1st Battalion, moved forward with each of the companies, and each had one squad of engineer troops with demolitions. Enemy rifle fire was heavy. The men broke up into small groups, proceeding unevenly in the general direction of Nob Pier. Between 1830 and 1900, Capt. Peter Blaettler, Company E’s commander, was seriously wounded.30 Control from the battalion command post had been lost—that element was hugging the ground to avoid sharp fire from enemy riflemen. Colonel Aulich had become separated from the main part of his battalion and was to remain so until the next morning. To all intents and purposes he had lost command of his unit.31

The 2nd Battalion’s attack was pushed along the eastern side of Will Road toward Nathan Road, but as sunset approached it became evident not only that Company E would not reach Nob Pier but also that across Will Road on the left flank there was an area with many strong enemy defense positions too powerful to be occupied in the forty-five minutes before dark.32

Action of the 32nd Infantry After Change of Plans

The 3rd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, with the support of Company C of the same regiment, pushed rapidly toward Nathan Road to execute its mission under the revised plan of attack, which became effective at 1330. On the extreme right wing, Company I achieved excellent coordination of infantry-engineer teams with medium tanks, and rapidly reduced Nap Strong Point, which proved to be only weakly defended. The company was reported at 1355 to have reached Nathan Road.33 Company K, in the inner zone, had much more difficulty. Its route lay through a maze of ruined buildings, debris, connecting trenches, and still active pillboxes, as well as shelters crowded with hiding enemy. The terrain and poor communications prevented tank-infantry cooperation, and while the tanks were reducing

enemy positions the infantry had to work near rather than with them.34 Company K was about two hundred yards to the left rear when Company I reportedly reached the road. Company L, in fulfillment of an understanding reached during the morning by the two leading battalions, was withdrawn from the Admiralty area to cover the gap on the left of the 3rd Battalion’s front when it was found that Company A, 184th Infantry, had pulled back for its new mission under the revised plan.35 Behind L, Company C, in support, received heavy rifle fire from the left, by which Capt. Charles W. Murphy, Jr., the company commander, was wounded.36 Company B and then Company A, 32nd Infantry, were both committed to mopping up the Admiralty area, from which they moved north toward Noel Road.37

As the reports sent back to regimental headquarters were persistently conflicting and confused, it proved impossible to coordinate company movements. Perhaps even more important was the battered and shattered condition of the terrain. The terrible pounding to which Kwajalein had been submitted by artillery and naval shells was not an unmixed blessing to the infantry. The difficulty of getting around the rubble and other physical impedimenta tended to diffuse units and keep their flanks dangling. In the middle of the island near Noel Road the conditions of battle and terrain made coordination almost out of question since enemy fire was being delivered against the advancing battalions from positions between them and even to their rear.38

Company I, 32nd Infantry, remained near Nathan Road, unable to advance until the line at the left came up. General Corlett came ashore and at 1640 held a telephone conference with his assistant division commander, General Ready, Colonel O’Sullivan of the 184th Infantry, and Colonel Logie of the 32nd Infantry. He was reassured concerning the progress of the attack.39 Thinking ahead to the remaining enemy blockhouses and other concrete positions that might still be in the northern portion beyond Nathan Road, General Corlett arranged for naval gunfire to be spotted. This fire, from a heavy cruiser, was to be controlled through the naval liaison officer with the 32nd Regiment, and it was to be delivered wherever the regiments desired. The regimental commanders later decided, however, that they were not yet in position to use this support. The main effort, they felt, had first to be the straightening of the line across the island.40

Between 1630 and 1730 Company K was moved up beside Company I by a maneuver that enabled Company I to furnish protection for its rear while it moved. Company L then advanced along the same route. As it moved, fire hit it from its left flank, possibly originating among friendly troops. The company did not complete its mission. It stopped for the night in the middle of the island between Noel and Nathan roads and its exact position was not accurately reported until next morning.41

Situation on the Night of 3 February

All planes had returned to their carriers by 1857. The 3rd of February had been a

quiet day for the planes over Kwajalein Island, where patrol and observation duty rather than air strikes had occupied them.42 Admiral Reeves’ carrier group, part of Task Force 58, departed during the evening for Majuro to refuel. One group of small escort carriers remained to furnish protection for the remainder of the battle for Kwajalein. The lagoon anchorages had filled steadily during the day. Transports carrying the reserve force, which it was clear would not be committed in this action, came into the lagoon from their previous station east of the atoll. All the transports of the attacking force were also at anchor. One group was so nearly unloaded that it could plan to depart for Funafuti early in the morning.43

The eight LSTs and three LCTs of the Kwajalein Island Defense Group, which arrived about noon on 2 February, had unloaded enough men and material to undertake the general defense of the western end of the island as far as Wilma Road. The group had brought ashore and emplaced its 40-mm. antiaircraft batteries on the western beaches.44

During the day, Green Beach 4, the westernmost portion of the lagoon shore, became the principal scene of shore party operations. Pontoon strips brought by LSTs were lashed together to form the first of two causeway piers there, and progress was well advanced toward the completion of a good road connection from the beach to the island’s highway system. All beach and shore parties were consolidated. One of the transport groups shifted its unloading operations from Carlos Island to Kwajalein Island. The hospital ship Relief anchored in the lagoon at noon and began to take aboard the casualties already in the sick bays of the transports and to receive others directly from the beaches.

Those on Kwajalein Island were carried directly from beach to ship in landing craft, thus avoiding the previous days’ delays caused by transferring the wounded from LVTs to boats at the edge of the reef. Heavy engineer equipment began to come ashore, although the main stream of such traffic was not to be released until the beachhead was better prepared.45

The advance along the axis of Kwajalein Island on 3 February had progressed about 1,000 yards. The hard fighting had been more costly than on either of the preceding days. Fifty-four were reported killed in action, and 255 wounded of which 60 were returned to duty.46 The enemy, however, had paid heavily in lives as well as in lost ground. The 32nd Infantry estimated that 300 had been killed on its side of the island, and the 184th estimated at least 800 and perhaps 1,000 in its zone. In the one huge blockhouse alone, 200 dead had been found, many of them evidently suicides.47

Neither of the regiments had reached Nathan Road in spite of optimistic reports to regimental headquarters. The 32nd Infantry was on one of the smaller streets among the cantonments, a road that paralleled Nathan Road about 150 yards south. At the extreme right of the eastern zone was Company I and at the left of the zone, Company L. Holding a line that folded back from Company L’s left flank as far as Carl Road were Companies B and A. Companies K and M were bent

Ponton Piers at GREEN Beach 4

back along the ocean shore. Company C, which had been supporting the 3rd Battalion during the afternoon, was to be placed across the zone behind the two forward companies despite some remaining uncertainty about its release for that mission by the 1st Battalion, which was expected to lead the assault next day, and even though no one knew exactly where Company L was located. In the last minutes of daylight, largely on the initiative of 1st Lt. Ramon Nelson, a platoon leader temporarily in command of Company C, that company started marching to its widely dispersed position while its other officers were still in conference with battalion and regimental commanders over the orders to move. Its elements were separated during the movement and its exact situation was not well understood at regimental headquarters until next morning.48 From Carl Road back to Wilma Road, the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, covered the regimental zone; and from Wilma Road to the end of the island, on order of General Ready, the division’s shore party provided defense of supply installations.

The 184th Infantry was about seventy yards farther south than the 32nd Infantry. The two leading companies, E and G, had pushed into an area between Will Road and buildings on the left of Company L, 32nd Infantry. West of the highway, as well as in front of the two companies at the north and in the uncleared buildings on the east, the enemy had control. A gap actually existed in the rear of Company E in a portion of the island over which no

contact with Company A had been established. Thus, the energetic push toward Nathan Road and Nob Pier had moved these companies into a salient. Heavy and light machine guns were set up to cover the areas at the left and front, but from the ruined structures on the right, rifle fire on Company G was heavy and incessant during the night, its accuracy improving with approaching daylight. The 3rd Battalion, 184th Infantry, held the sector from Nora Road to the western edge of Center Pier. Defense of the supply installations in the remaining portion of the island as far west as Red Beach 1 was the mission of the shore party and, in part, of the 184th Infantry’s Cannon Company.49

Eagerness to reach the Nob Pier line on 3 February had induced the leading elements of both regiments to advance with all possible speed, without paying full attention to local security. Night found them in positions in which they were intermingled with the enemy, sometimes at such close range that fighting was restrained for fear of damage to friendly troops. At many points along the front, and at several spots in the rear, flickering fires lighted up adjacent areas and silhouetted moving men.

Typical of the experiences all along the line on this evening were those that befell Company C, 32nd Infantry.50 This unit had begun moving into position across the rear of the 3rd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, at approximately 1930. It was then nearly dark. There had been little time to investigate the ground the company covered, but in the gathering dusk, three large Japanese shelters and one pyramidal tent were found in the defensive area. The men of Company C felt that Japanese were still hiding under the canvas and were reasonably certain that the shelters contained several enemy soldiers. The men were torn between two courses of action: clean out the enemy, or simply let them remain where they were until morning. Because the company radio was not working and no information could be passed on to neighboring units that Company C was actually moving in across the rear of the front line, the latter course was chosen. There was some fear that firing in the rear might be misinterpreted by the forward companies. Any pitched battle in the area would be almost certain to draw heavy American fire from the front and flanks.

Company C “bedded down” in the midst of the enemy. The darkness and uncertainty of its position prevented its digging in. Behind the men of Company C were 150 yards of ground filled with debris that had not been investigated or cleaned out. On the right, 150 yards away, Company K had placed its flank on the ocean shore and extended forward and inland in a great arc. On the left, its exact whereabouts unknown to Company C, was the 184th. To the rear, two great fires burned brightly, casting a red light over the whole area. At five-minute intervals flares and star shells from the mortar sections and ships drifted over the front, and sometimes directly over troops in the eastern zone. From 2000 to almost 0300 moonlight also faintly illuminated the area.

Whenever the illumination became unusually bright, enemy machine guns swept Company C’s area, and from time to time mortar shells and grenades landed among the men. American BARs, directed against scattered Japanese, threw bursts of

fire from the company’s rear. When fire became too heavy in certain parts of their area, elements of Company C tried to move to more favorable positions. Somewhere during these movements six men of the mortar section of the weapons platoon were killed, although their presence was not missed until next morning.

Japanese were in the areas south of the front line in greater numbers than on either of the preceding nights of the Kwajalein Island operation. They prowled in the forward area all night. Some incidents occurred as far to the rear as Corn Strong Point, more than a thousand yards from the 32nd Infantry’s advanced position.51 Japanese came out of shelters, screaming and yelling, throwing grenades, and charging at the men in foxholes. They fired rifles and threw grenades from buildings that offered places of advantage. In a pocket northeast of the Admiralty area, they greatly harassed the companies near them.

Attacks from the north and from the lagoon shore were also attempted by enemy troops at various times during the night. Just after sunset, a bugle could be heard sounding among the enemy shelters near the base of Nob Pier, and shortly afterward a headlong counterattack by screaming Japanese was made toward Company E and Company G, 184th Infantry. As the Japanese tried to cross Will Road, they were cut down to the last man.52 Five prospective attacks were broken up before they were actually in progress by barrages along the entire front from mortars and from the supporting batteries of artillery on Carlson Island.53

Just before 0400, nevertheless, heavy enemy mortar and dual-purpose gunfire, which struck Companies I and L, 32nd Infantry, was closely followed by a surprise attack by an unknown number of enemy. This effort was beaten off and no other was tried for an hour. Then a second organized attack came and was also repulsed by Companies I and L.54 Sometime after midnight, an effort by a group of the enemy to come ashore from the lagoon reef at a point opposite Company A, 184th Infantry, was foiled by automatic fire. Infiltration by individual Japanese was repeatedly stopped in the Company A area. In the morning twenty-seven enemy dead were found there.55 About 0530 an attack by from thirty to forty Japanese upon the front line of Company E, 184th Infantry, wilted under the bursts from the machine guns set up there.56 This attempt was the last of the night’s futile sorties by enemy groups. From various positions beyond Nathan Road, enemy machine gun, mortar, and artillery fire was directed into the forward area at irregular intervals during the night, sometimes coinciding so closely with the fire from Carlson Island that Japanese monitoring of the artillery radio was suspected.57

The 49th Field Artillery Battalion fired 1,492 rounds of ammunition on Kwajalein Island between 1800 and 0600, and the 47th Field Artillery Battalion fired 716.58 In position near Carl and Will Roads, the six 81-mm. mortars of the 3rd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, sent approximately 1,500 rounds into the enemy area after dark, and the 60-mm. mortars with the companies

were also active.59 Harassing fire ceased at 0600 as the artillery was made ready for the morning’s preparatory fire at 0700. The 49th Field Artillery Battalion, however, shelled the northern end of the island during that period in the last of several attempts to silence enemy guns.60

Thus as dawn broke on the morning of 4 February the men of the 32nd and 184th Regiments prepared to make their final drive to the northern tip of Kwajalein Island. The complete capture of the island was taking longer than had been expected. In spite of the excellence of both naval gunfire and land-based artillery, this northern sector of Kwajalein had proved still to contain a sizable number of Japanese well concealed among the damaged buildings and in underground shelters and pillboxes. Infantrymen, engineers, and tanks, working separately and in coordination, still had to feel their way cautiously among the remnants of the enemy’s defenses. Another hard day’s fighting remained ahead.