Chapter 19: The Seizure of Eniwetok Atoll

Plans and Preparations

The easy capture of Kwajalein Atoll provided the Central Pacific forces with an unexpected opportunity to advance their schedule of operations. Since the original directive of 20 July 1943, plans had been formulated by Admiral Nimitz, with the concurrence of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, for an expansion of the American offensive in the Central Pacific. These plans had contemplated the capture of Eniwetok Atoll, on or about 1 May 1944, in preparation for a possible seizure of Truk or other islands in the Carolines. A strike by the main elements of the Pacific Fleet against Truk had been tentatively scheduled for 24 March 1944, prior to the landings on Eniwetok and Truk.1 The 27th Infantry Division had been alerted on 13 January 1944 to prepare for the seizure of Eniwetok.2 Preparations for this new move were already in their preliminary stage when the landings in the Marshalls took place.

The possibility that the operations against Kwajalein might be concluded early enough to step up the advance against Eniwetok had been considered by Admiral Nimitz and other naval planners even before the Marshalls operation was launched. Admiral Spruance later recalled that before sailing for Kwajalein from Pearl Harbor he had received the first aerial photographs of Eniwetok indicating that the atoll was only lightly defended, but other indications were that the garrison was being reinforced by several thousand troops. He reported these findings to Nimitz and expressed the hope that immediately upon the conclusion of the Kwajalein-Majuro operation he might proceed to the capture of Eniwetok rather than send his fleet to the South Pacific for the attack against Kavieng, which the Joint Chiefs of Staff had scheduled for 1 April 1944.3

By 2 February it had become apparent that Kwajalein could be completely secured without the commitment of the reserve troops—the 22nd Marines and the 106th Infantry (less 2nd Battalion). Admiral Nimitz radioed Spruance asking his recommendation on proceeding immediately to the capture of Eniwetok, covering it with a carrier strike against Truk. After consulting with Admiral Turner and General Holland Smith at Kwajalein, Admiral Spruance recommended approval, and the decision to strike at Eniwetok was confirmed.4

On 3 February, Admiral Hill, who had commanded the brief assault on Majuro,

was flown by seaplane to Kwajalein. He proceeded at once to a series of conferences with Admirals Spruance and Turner, and from these conferences the basic plans for the invasion of Eniwetok were formulated.5

No operation that preceded or followed it in the Central Pacific had the same impromptu character that marked the seizure of Eniwetok. Formal planning may be said to have begun no earlier than 3 February and lasted until 15 February, the day on which the expedition sailed for Kwajalein lagoon. The invasion force was assembled in a seven-day period, beginning with the conclusion of the Kwajalein campaign and ending the moment the ships sailed into the open sea. While the expedition against Eniwetok was not exactly makeshift, it was, by previous standards, thrown together hurriedly without the meticulous preparation that characterized most large-scale amphibious operations.

The plan for the seizure of Eniwetok included the ambitious project of a full-scale carrier strike against Truk, which lay about 670 nautical miles southwest of Eniwetok Atoll. Truk had long been known to Americans as the “Gibraltar of the Pacific” and the “Japanese Pearl Harbor.” It possessed the best fleet anchorage in all the Japanese Mandated Islands and since July 1942 had been the base for the Combined Fleet, now under command of Admiral Koga. Also, Truk served as headquarters for the 6th Fleet (submarines) and was an important air base and staging point between Japan and the South Pacific.6

Admiral Mitscher’s fast carrier force (Task Force 58) was assigned the job of conducting a full-scale strike against Truk on 16 February, partly to cover the Eniwetok landing but, more important, to hit the Combined Fleet, which was thought to be still based there, as well as to damage the airfields and destroy any planes that might be found there. After completion of the move against the eastern Carolines, Mitscher’s task force was to proceed on northwest and strike at the Marianas, if feasible.7

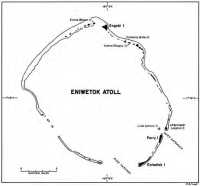

Eniwetok Atoll, the target assigned to Admiral Hill’s task group, lies 330 nautical miles northwest of Kwajalein.8 It is a typical Central Pacific coral atoll with a circular reef surrounding a lagoon, which at its widest point is seventeen miles from east to west and twenty-one miles from north to south. Some thirty small islands rise from the reef, most of them along the eastern half. The main islands, three in number, were Engebi in the north, Parry in the southeast, and Eniwetok in the south. There were, at the time of the invasion, only two deep-water passages into the lagoon. One, called Wide Passage, was located at the extreme southern end of the lagoon to the west of Eniwetok Island. The other was Deep Passage, lying between Parry and Japtan Islands.

When planning for the operation began, intelligence of the atoll was vague. One reconnaissance mission, flown from the Gilberts on 28 December, had managed to reach the atoll and take air photographs from an altitude of 20,000 feet. Other aerial photos, taken during the neutralization strikes that accompanied the Kwajalein landings, became available during the planning period, and additional photographs were dropped from planes onto the

Map 16: Eniwetok Atoll

ships of the invasion convoy while the vessels were en route to the target.9

Until early January, the best American intelligence sources indicated that there were only about 700 Japanese in the atoll, mostly concentrated on Engebi Island, which contained the only airstrip in the area. Late in January, however, it became apparent that the atoll might have been recently reinforced. From documents captured at Kwajalein, the presence of the Japanese 1st Amphibious Brigade in the Marshalls became known. American intelligence staffs at that time knew it as the 1st Mobile Shipborne Brigade and surmised from its designation that it might be stationed aboard ships so as to be transferred readily from one atoll to another. The brigade had been traced to Truk, thence eastward, but had been lost by American submarines

before its arrival at its ultimate destination. The ships had not been located during the invasion strikes. Captured documents from Kwajalein and a prisoner of war who had formerly been a member of the Kwajalein detachment of the brigade confirmed the planners’ fears that the main strength of the unit was at Eniwetok. This information, received during the first week of planning, caused the estimate of the Eniwetok Atoll garrison to be revised upward to 2,900-4,000 troops. Air photographs taken during the assault on Kwajalein indicated that most of the above-ground installations on Engebi showed a considerable increase in the foxhole and trench systems, but failed to disclose any indication of troops on Parry beyond the location of a few new foxholes. On Eniwetok Island, approximately fifty new foxholes were discovered as well as indications of small enemy forces near the southwest end of the island. On the basis of interpretations made from these later photographs, it was assumed that the main body of the Japanese garrison, whatever its strength, would be found on Engebi, and that Parry and Eniwetok Islands would be only lightly defended.10

Composition of the Force

The Eniwetok expedition was to be much smaller than the one that had just captured Kwajalein. In organizing it, Admiral Hill modeled his force after the Majuro Landing Force rather than adopt the more elaborate task force organization for Kwajalein. The force was known as the Eniwetok Expeditionary Group. Admiral Hill’s flagship was the attack transport Cambria, which had been converted to an amphibious headquarters ship by the addition of much additional radio equipment and other communications facilities. The troops with their supplies and equipment were to be lifted aboard five attack transports, one transport, two attack cargo ships, one cargo ship, one dock landing ship, two high-speed (destroyer) transports, and nine LSTs. This transport group, which also included six LCIs, was to be screened en route by ten destroyers. The naval fire support group, commanded by Rear Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorf, USN, contained three battleships, three heavy cruisers, and seven destroyers. Air support would be provided by an escort carrier group containing three escort carriers and three destroyers, and a fast carrier group (Task Group 58.4, detached from Admiral Mitscher’s carrier task force) containing one heavy carrier (CV), two light carriers (CVL), two heavy cruisers, one light antiaircraft cruiser (CL(AA)), and eight destroyers. Finally, a group of three mine sweepers was attached.11

The assault troops assigned to the expedition consisted mainly of the 106th Infantry Regiment, reinforced (less the 2nd Battalion), commanded by Col. Russell A. Ayers, USA, and the 22nd Marine Regimental Combat Team commanded by Col. John T. Walker, USMC. Both were joined under a temporary command echelon entitled Tactical Group One, V Amphibious Corps, commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, USMC. This command also included several other units that had been detached from the Kwajalein attack forces after completing their duties there. These included the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company, the Scout Company (Company D) of the 4th Marine Tank Division, Company A of the 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion (17 amphibian

Chart 3: Task organization of major commands for the attack on Eniwetok Atoll

tanks), the 708th Amphibian Tractor Battalion (less one LVT group) totaling 102 LVTs a provisional DUKW company of the 7th Infantry Division (30 DUKWs and 4 LVTs), and part of Demolition Team 1. The total landing force came to 7,997 men.12

Except for those units that had participated in the landings at Kwajalein, the assault troops assigned to Eniwetok lacked the intense training that usually preceded amphibious invasions in the Pacific. The 106th Regiment had received some amphibious training in the Hawaiian area in the early autumn of 1943 when it had been thought that the entire 27th Division would invade Nauru, but subsequent specialized training had been only sketchy because of the last-minute assignment of the unit to the reserve force for the Kwajalein operation.13 The 22nd Marines, stationed on Samoa since mid-1942, had only moved to the Hawaiian area in November of 1943, and its eleventh-hour training too was sketchy.14 Both units suffered from want of realistic amphibious rehearsals. About all they had been able to accomplish before sailing for Kwajalein were simple practices

in ship-to-shore movements. Not enough amphtracks were available and there were no DUKWs. During the operation itself most of the troops were landed in amphtracks for their first time. The Marine artillery battalion landed for its first time in DUKWs. The rehearsal held on the island of Maui had not permitted any appreciable advance inland, no combat firing, no infantry-tank team movement. In short, the troops destined for Eniwetok were greener than most going into actual amphibious combat for the first time.15

Tactical Plans

Initially, the target date recommended was 12 February, but was later changed to 15 February, and finally established for the 17th of that month.16 The assault was originally divided into four phases. Phase I was to take place on D Day, 17 February. Following the usual preliminary gunfire, aerial bombardment, and mine sweeping operations, the Reconnaissance Company, V Amphibious Corps, was to land initially on Camellia (Aitsu) and Canna (Rujoru) Islands southeast of Engebi. At the same time the scout company (Company D), 4th Marine Tank Battalion, was to land on Zinnia (Bogon) Island northwest of Engebi to prevent any escape of the enemy from Engebi in that direction. Once Camellia and Canna were secured, the 2nd Separate Pack Howitzer Battalion (Marine) with 75-mm. pack howitzers was to land on Camellia, and the 104th Field Artillery Battalion (Army) with 105-mm. howitzers was to land on Canna. The two battalions were then to prepare to support the next day’s attack on Engebi. Phase II was to commence on 18 February. The 22nd Marine Regiment was to land on the lagoon shore of Engebi with two battalions abreast and capture that island. One platoon of the 106th Infantry’s Cannon Company, consisting of two self-propelled 105-mm. guns, was to support the marines. The 106th Regimental Combat Team was to act as group reserve during this phase. During Phase III of the operation, Eniwetok and Parry Islands in the southern sector of the atoll were to be seized, the date depending upon the progress of the attack on Engebi. The 106th Infantry with the 2nd Separate Tank Company (Marine medium tanks) attached, was to land in column of battalions on Eniwetok Island and capture it. One battalion of the 22nd Marines was to be prepared to land in support if necessary, while the remaining marines were to occupy the other small islands in the northern sector of the atoll. It was presumed that Eniwetok Island would be only lightly defended, so the 106th was ordered to be prepared to land on Parry Island within two hours after the initial assault on Eniwetok. During Phase IV, the remainder of the islands in the atoll were to be occupied by troops of both the Marine and the Army regiments.17

Preliminary Air Operations

As the Eniwetok Expeditionary Group sailed from Kwajalein lagoon on 15 February, Marc Mitscher’s mighty flotilla of fast carriers was moving swiftly westward toward that most fearsome of all of Japan’s island bases in the Central Pacific—Truk. With three of its fast carrier groups (the fourth was detached to support the Eniwetok landings), Task Force 58 set sail from

Majuro on 19 February. Operating under the command of Admiral Spruance, who carried his flag aboard the new battleship New Jersey, Task Force 58 consisted of 5 heavy carriers, 4 light carriers, 6 battleships, 10 cruisers of various sizes, and 28 destroyers.18 After refueling at sea, Mitscher’s ships arrived off of Truk in the early morning of 17 February (Tokyo time) and launched their first fighter sweep of seventy planes, which attacked aircraft and airfields at dawn. The strike was eminently successful. A total destruction of 128 enemy planes (72 on the ground and 56 in the air) was credited to the U.S. naval pilots with the loss of only four American planes.19 Immediately after the fighter strike, eighteen torpedo bombers dropped fragmentary clusters on most of the airfields, rendering them temporarily unserviceable. Next day the main strike against shipping in the harbor was made. Naval planners had hoped to catch a sizable element of the Combined Fleet at Truk, where it had been sighted two weeks earlier by Marine reconnaissance planes. Unfortunately, Admiral Koga was alert to the impending danger and had set sail with most of his fleet for Palau before the U.S. carriers arrived. Nevertheless, the Japanese merchant marine suffered a severe blow as a result of the strikes. A total of about 200,000 tons of merchant shipping was destroyed in the harbor. Also, while the carrier planes were working over Truk itself, Admiral Spruance’s support ships were able to intercept and sink one light cruiser and one destroyer trying to escape from the area. A third Japanese destroyer got away.

Meanwhile, the fourth fast carrier group (Task Group 58.4), which had been attached to Admiral Hill’s command, proceeded directly against Eniwetok on 16 February, the day before the expeditionary force arrived. There, the planes destroyed all buildings of any consequence, rendered the airfield at Engebi temporarily useless, and demolished one of the two coastal defense guns on the northeast corner of that island. The airfield was pitted with bomb craters, and an estimated fourteen enemy aircraft were destroyed on the ground. In addition, last-minute aerial photographs were taken and delivered to Admiral Hill’s flagship, Cambria, at sea en route to the target.20

Japanese Defenses on Eniwetok Atoll

Although before the attack on Pearl Harbor the Japanese Navy had conducted extensive construction projects in the Marshall Islands, Eniwetok had been largely overlooked. Up to that time Japanese plans called for the atoll to be used only as a fuel storage depot, and on 5 September 1941, the 4th Fleet ordered 1,416,000 yen ($336,583.20) to be set aside for the construction of a fuel tank, feed pipe, and living quarters for the personnel to man the depot.21

Evidently, the first Japanese garrison on Eniwetok was a small detachment of six men sent from the 61st Guard Force at

Kwajalein to man a special lookout station.22 In November 1942 about three hundred construction workers landed at Engebi. The next month about five hundred workers of the 4th Fleet Construction Department were sent to Eniwetok to construct an airfield. The field was completed in June or July of 1943, whereupon the majority of the construction personnel were transferred to Kwajalein. Sometime between August and October 1943 a small naval garrison force, never totaling more than sixty-one men, arrived at the atoll to garrison Engebi and its air base. This garrison maintained three lookout stations, a branch naval post office, a battery of two 12-cm. guns, and two twin-mount 13-mm. machine guns. The tiny force was the only ground combat unit on Eniwetok Atoll before the arrival of the 1st Amphibious Brigade on 4 January 1944.23

Thus Eniwetok Atoll was left practically unprotected, with no major system of prepared defenses. The 1st Amphibious Brigade arrived less than a month and a half before the American landings and barely had time to dig in. The contrast between the Japanese capacities here and at Kwajalein are obvious. In the latter atoll the fortifications had taken years to construct. Some of the units at Kwajalein had been there since before Pearl Harbor and were certainly prepared to defend the base long before U.S. forces attacked it. At Eniwetok, over 2,500 troops were dumped on a lonely atoll almost barren of defenses only six weeks before the American landings.

The 1st Amphibious Brigade, which totaled 3,940 troops, may have originally been intended to serve as a mobile reserve force for the entire Marshalls area, to be based at Kwajalein and rushed to other threatened atolls. But when the brigade reached Truk on 27 December it was ordered to be parceled out to Wotje, Maloelap, Kwajalein, and Eniwetok to reinforce the garrisons on those atolls. The brigade left Truk on 30 December, reaching Eniwetok on 4 January. There, the Eniwetok detachment consisting of 2,586 troops was detached and the convoy left for Kwajalein and elsewhere.24

In addition to the 2,586 troops of the brigade, there were stationed on Eniwetok Atoll at the time of the attack almost a thousand other enemy personnel: civilian employees of the brigade; fifty-nine men of the 61st Guard Force Detachment, which had been there since October of 1943; air personnel that were in the process of being evacuated; a small survey party of about fifty men; Japanese and Korean construction workers; laborers hired by the Sankyu Transportation Company; and an unknown number of naval stragglers. This brought the total to about 3,500, but of this number only the brigade and the 61st Guard Force Detachment could be considered effective combat troops.25 Thus, in terms of numbers alone, Eniwetok housed more combat troops than Kwajalein, but this difference was more than offset by the comparative paucity of fortifications on Eniwetok Atoll.

Contrary to American expectations, the bulk of the enemy personnel at the time of the landings was located on Parry Island rather than on Engebi. Parry was the headquarters of Maj. Gen. Yoshimi Nishida, who commanded the brigade, and on

this island Nishida had stationed the brigade reserve and the Parry Island garrison, totaling 1,115 troops, with almost 250 other personnel. The troops had with them a total of thirty-six heavy grenade dischargers, thirty-six light machine guns, six heavy machine guns, ten 81-mm. mortars, three 20-mm. automatic guns, two mountain guns, one 20-mm. cannon, and three light tanks.

The defense plans for Parry were outlined in a brigade order dated 5 February 1944. About one half of the troops were disposed at the water’s edge, where they were to be grouped into strong points about 140 feet apart. The defense of the beaches was to be supported by mountain guns, 20-mm. automatic guns, and other weapons. The mountain guns and 20-mm.’s were to fire first. Light and heavy machine guns were to fire on landing craft before and after they reached the underwater obstacles. Next, mortars and grenade throwers were to deliver concentrated fire against the enemy at the beaches and were to cover the sectors between fortified areas and strong points. To facilitate the employment of artillery and heavy weapons, the order called for fields of fire to be cleared through coconut groves. The order gave quite explicit instructions for measures against tanks: “Destroy enemy tanks when they are stopped by obstacles by means of hollow charge antitank rifle grenades, close-in attack, land mines, water mines, and Molotov cocktails. Especially at night, have a part of the force attack them.”26

The order made it very clear that the brigade was not expected to survive an American assault once it had established a beachhead. Any troops remaining after the Americans had landed in force were to assemble in a central area. Then, the order continued, “... sick and wounded who cannot endure the battle will commit suicide. [Others] ... will reorganize, return to battle as a unit, and die fighting.”27

The Japanese were able to construct very few installations and gun positions above ground on Parry in the short time that the brigade was there. With very few exceptions, the defenses consisted of foxholes and trenches. These fell into two categories, the old and the new. The old foxholes and trenches were located on the ocean side, were well constructed, and often lined with rocks or coconut logs. Relying on their estimate of American amphibious tactics as demonstrated at Tarawa, the Japanese more recently had undertaken heavier defenses on the lagoon side. These were freshly and hastily constructed, and therefore much inferior. All entrenchments were well camouflaged, although the camouflage was superior on the ocean side. A typical strong point consisted of a spider-web pattern of entrenchments. In the center of the web was a large personnel shelter lined and covered with coconut logs. Strips of corrugated iron and a thick layer of sand were placed over the log roof. The center was surrounded by a circle of foxholes ten to fifteen feet apart, mostly roofed over with corrugated iron. These holes were connected with one another by narrow trenches or tunnels. The trenches and tunnels on the outer edge of the web were in turn joined by radial trenches and tunnels to the shelter or control foxhole in the center of the position. The entire web was extremely well camouflaged and very difficult to locate. Parry was honeycombed with positions of this sort.28

On neighboring Eniwetok Island were stationed 779 Japanese combat troops of the brigade plus 24 civilian employees and 5 naval personnel manning the lookout station. The island was commanded by Lt. Col. Masahiro Hashida, and the garrison originally possessed a total of two flame throwers, thirteen grenade dischargers, twelve light machine guns, two heavy machine guns, one 50-mm. mortar, eleven 81-mm. mortars, one 20-mm. automatic gun, three 20-mm. cannons, and three light tanks.29 The garrison was divided into five forces, three on the lagoon shore, one placed so as to cut off the narrow eastern neck of the island, and one to be held in reserve. The three lagoon shore forces were to place their weapons so as to obtain interlocking bands of fire over the surface of the lagoon. The force in the east was to protect the rear of the three lagoon shore forces from any American units landing on the northern tip of the island. The reserve force was placed to the rear of the forces on the lagoon shore, near the western tip of the island.30

As on Parry, the defenses consisted mostly of foxholes and trenches. Those on Eniwetok Island were better constructed and better camouflaged. After the capture of Kwajalein, the Japanese had begun construction of concrete pillboxes on the southwest tip of the island and had dug additional foxholes. Land mines were also found on Eniwetok.31

On Engebi, at the northern tip of the atoll, the garrison consisted of about 692 members of the 1st Amphibious Brigade plus 54 naval personnel of the 61st Guard Force Detachment and an additional 500 noncombat personnel. The garrison was commanded by Col. Toshio Yano. Its total weapon strength came to two flame throwers, thirteen grenade dispatchers, twelve light machine guns, four heavy machine guns, two 37-mm. guns, one 50-mm. mortar, eleven 81-mm. mortars, one 20-mm. automatic gun, two 20-mm. cannons, two mountain guns, three light tanks, and two 12-cm. coast defense guns.32

Colonel Yano on 10 February made a very accurate estimate of American intentions:–

The enemy will bomb this island either with carrier or land based planes and will bombard us from all sides with battleships and heavy cruisers. Directly following these bombardments, an amphibious force landing will be carried out.

It will be extremely difficult for the enemy to land here from the open sea because of the high waves and rugged reefs.

[Therefore] it is expected that they will ... enter the atoll and carry out landing operations from the lagoon ... making assaults on outlying islands, they will approach this island from all directions.33

Yano accordingly planned to concentrate his defensive system on the lagoon shore of this triangularly shaped island. The Japanese defenders were ordered to “... lure the enemy to the water’s edge and then annihilate him with withering fire and continuous attacks.” Most of the

prepared defenses and over half of the brigade detachment were concentrated at the center of the lagoon shore. The approach to this strong point was flanked by the fire of two 75-mm. mountain guns on the northwest corner and two 20-mm. machine cannon in the southern part of the concentration itself, as well as two 37-mm. guns emplaced on the southern tip. Frontal fire could be delivered by the 20-mm. automatic guns and the three tanks, each mounting 37-mm. guns.

Besides the main area of defense on the lagoon shore, three other strong points were established, one in each of the three apexes of the island triangle. The south corner contained the 2nd Rifle Company (less one rifle platoon) plus the 37-mm. gun platoon detached from Yano’s artillery company. The west corner was composed of the artillery company (less its 37-mm. gun platoon) plus the rifle platoon detached from the 2nd Rifle Company. In the north corner of the island was located the 61st Guard Detachment, manning the two 12-cm. coast defense guns.

Before the arrival of the 1st Amphibious Brigade, the defensive system had been predicated on an assault from the ocean, for it was on the ocean sides of the island that the better-prepared and older trenches and dugouts were found. Not until after the arrival of the brigade were hasty efforts made toward fully organizing a defensive system along the lagoon shore. While the lagoon foxholes and trenches were numerous, they were hurriedly and rather poorly constructed. Most of them were located about three hundred yards inland and parallel to the lagoon beach. Dugouts of coconut log and earthwork embankments as well as some concrete pillboxes were on Engebi. The concrete was less than one foot in thickness, not reinforced, and had a very low resistance to penetration and blast.34

The effectiveness of the Japanese defense of Eniwetok Atoll cannot, however, be estimated on the basis of Japanese plans, for by the time the first American troops landed on the atoll the enemy’s strength had been greatly reduced. Air strikes were successful in inflicting considerable damage on installations and weapons and in causing a large number of casualties. The raids reduced the ammunition supplies and food stores. The medical situation at Eniwetok was very poor in the first place, and the reduction of food rations lowered the health and energy of the Japanese to such an extent that many were physically incapable of carrying on their assigned duties. Moreover, the frequency of the raids resulted in constant interruption to the work schedule and forced the Japanese to work at odd hours, often at night. These factors, together with the speed of the American advance from Kwajalein to Eniwetok, meant that the Japanese were only partially prepared before the preinvasion bombardment. This bombardment had the further effect of causing more damage and casualties, and partially, though not completely, disrupting organized resistance.35

The Seizure of Engebi Island

The two sections of Admiral Hill’s Eniwetok Expeditionary Group arrived off the southeast coast of Eniwetok Atoll during the early morning of 17 February. The fire support ships separated for bombardment missions against Engebi, southwestern Eniwetok Island, and the islands flanking Deep Entrance, while the escort carrier group diverged to take station northeast of the atoll.36 Naval gunfire opened at 0659 without eliciting return fire from the enemy. At 0750 the ships halted their bombardment for air attacks against Engebi and Eniwetok. These were completed at 0825 and 0907, respectively, and the firing ships then resumed their bombardment. Meanwhile, at 0700 mine sweepers commenced sweeping a channel through Wide Passage. LSTs, though temporarily held up as the mine sweeper Sage swept a moored mine inside the lagoon, followed. Then the fire support ships and the main transport group steamed through Deep Passage, pouring 40-mm. automatic fire on Parry, Lilac (Jeroru), and Japtan Islands without response. Somewhat more than three hours later, the attack force reached its first stations in the northern part of the lagoon and preparations were begun for the initial landings on Canna and Camellia Islands, southeast of Engebi.

H Hour for the first landings was set at 1230, but unexpected delays developed. The sub-chaser, SC 1066, which was supposed to act as convoy guide, took station off the wrong island. The high-speed transport Kane sent her boats to the wrong LST, and the Marine artillery battery was delayed in getting boated and to the line of departure. As a result, the commanding officer of SC 1066 was relieved as was the commander of the Marine 2nd Separate Pack Howitzer Battalion.37

In spite of these contretemps, the first amphtracks, carrying troops of the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company and supported by two destroyers, made unopposed landings on Canna and Camellia Islands at 1318. Shortly before 1400 the landing troops reported that no enemy was present, and the 75-mm. pieces of the 2nd Separate Pack Howitzer Battalion and the 105-mm. howitzers of the 104th Field Artillery Battalion were taken ashore in DUKWs manned by the provisional DUKW company of the 7th Infantry Division. As at Kwajalein, some of the DUKWs carrying the 105-mm. pieces were fitted with special A-frames for use in unloading after landing. Guns, five units of fire, and gun crews were landed without difficulty. At 1602 all artillery had reached the beach and within half an hour was in position and prepared to register on Engebi. Registration was carried out without cessation of naval gunfire and was completed by 1902. About forty minutes later night harassing fires were commenced against Engebi. The mean range for the pack howitzer battalion was 6,900 yards and for the field artillery battalion, 8,100 yards. Fires throughout the night were executed at the rate of two rounds per gun per minute for five minutes every half hour.38

While the artillery was being emplaced, the naval underwater demolition unit reconnoitered the lagoon beaches off Engebi. As the battleships Colorado and Tennessee, destroyers Heermann and McCord, and one LCI(G) fired over their heads, the doughty

swimmers went as close as fifty yards from the shore. In spite of intermittent machine gun fire from the beaches, the team accomplished its mission without casualties. No underwater obstacles were discovered, and boat lanes and shoal spots were buoyed.

After securing Canna and Camellia, the Reconnaissance Company landed, against no opposition, on the three islands northwest of Camellia and on two small unnamed islands west of Canna. These landings were made to offer security to the artillery units against possible Japanese infiltration during the night. In addition, the scout company of the 4th Marine Tank Battalion was ordered to land on Zinnia (Bogon), just west of Engebi, to forestall the possibility of Japanese escaping from Engebi. This latter plan miscarried somewhat when some of the rubber boats carrying the scout company got lost in the dark and had to return to their mother ship, the APD Schley. The remainder, however, under the company commander, succeeded in landing at a point two islands below Zinnia and by 0315 worked their way northward to the proper island, which they found unoccupied.

Thus D-Day operations were carried through successfully in spite of some minor delays and errors in landing. No American casualties were sustained. The stage was set for the attack on Engebi.39

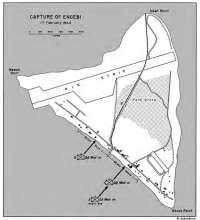

The plan for the main attack on 18 February called for an assault by the 22nd Marines against the lagoon shore of Engebi. W Hour was set at 0845. The two landing beaches extended 750 yards along the lagoon, with a finger pier as a dividing marker. The 1st Battalion, 22nd Marines, was to land on White Beach 1 on the right, the 2nd Battalion on Blue Beach 3 at the left. The two battalions were to be supported by medium tanks of the 2nd Separate Tank Company, and a platoon from the Cannon Company, 106th Infantry, with two 105-mm. self-propelled guns. The 3rd Marine Battalion was in regimental reserve while the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 106th Infantry, waited aboard ship, prepared to support the attack if necessary.

At 0655 Colorado and Louisville began shelling the northern and eastern part of the island. Tennessee and Pennsylvania moved at dawn to deliver close-range destructive fire against beach defenses from flanking positions on each side of the boat lanes. At 0720 two destroyers, Phelps and Hall, moved into position as direct support ships, but because of the smoke and dust rising from the island, Hall was unable to fire. Just before 0800 the naval guns ceased fire to allow a half-hour air strike to take place. This was completed ahead of schedule and naval fire was resumed at 0811 and increased steadily in intensity until just before the first troops landed. Shortly after the air strike was lifted, artillery on Canna and Camellia joined the naval guns and began to fire on the beaches at maximum rate until just after the first wave landed at 0844, whereupon the artillery barrage was lifted inland to the center of the island for another five minutes. Thereafter, because of the smallness of the island, very few call missions were fired.

As usual, LCI gunboats preceded the first wave firing rockets and 40-mm. guns. On each flank of the first wave were five

Map 17: Capture of Engebi 17 February 1944

armored amphibians; seven others were in V formation in the center. As the leading waves moved slowly from the line of departure, smoke and dust from the heavy bombardment swept out over the water obscuring the beaches from the crews and disguising the gradual divergence of the two assault battalions. The first waves of

Attack on Engebi

amphibian tractors tended to guide on LCIs operating to their flanks, and when the LCIs swung out from their direct approach to the beach and moved parallel to it, the leading LVTs tended to follow suit. Thus there was a gap between the two assault battalions by the time they reached the beach.

The armored amphibians moved quickly inland about a hundred yards, firing their 37-mm. guns at likely targets. Behind the first three waves of troops came the medium tank company, boated in LCMs. These landed on schedule with one unfortunate exception. One of the LCMs commenced to ship water because of a premature partial lowering of the bow ramp. In the tank this craft was carrying the crew was “buttoned up” and remained oblivious to frantic warnings as the craft filled up and sank in forty feet of water, five hundred yards from the shore. Only one man escaped as the tank sank to the bottom of the lagoon.40

Enemy opposition on the beach was at first light. Almost the only noteworthy resistance came from a few automatic guns on Skunk Point, the southeastern tip of the island. Company A on the right of the 1st Battalion found its right flank exposed and had to delay the attack until the aid of a tank platoon was obtained. On the left, the 2nd Battalion pushed forward rapidly, bypassing isolated points of resistance. These consisted chiefly of “spider-web” covered foxholes, similar to those that were to be encountered in greater number on Parry and Eniwetok Islands.

The 2nd Battalion overran the airfield quickly and within less than an hour tanks had pushed forward as far as the northern part of the island. By 0925 the troops were so far inland that the scheduled naval gunfire had to be called off. At 0955 the 3rd Battalion in reserve was landed and started the tedious job of ferreting the Japanese out of various tunnels and covered foxholes that had been bypassed by the assault battalions.

The only organized resistance occurred in the zone of the 1st Battalion in the area of Skunk Point. There, a large number of Japanese put up a stiff fight, but were slowly forced northward along the island’s eastern shore and eventually isolated and cut down. This took time, not only because of the stubbornness of the Japanese but also because of the heavy underbrush through which the marines had to move.

At 1450, about six hours after the initial landing, the island was declared secured. Mopping up continued, however, until the following afternoon. Meanwhile, before dark on 18 February the 3rd Battalion and the 2nd Separate Tank Company re-embarked for operations against Parry and Eniwetok. Total Marine casualties came to 85 killed and missing, and 521 wounded in action. In exchange, 1,276 of the enemy were killed and 16 prisoners of war taken.41

On the 18th and 19th of February the Scout and Reconnaissance Companies completed the search of all the smaller islands between Engebi and the major targets in southern Eniwetok Atoll.42

The Capture of Eniwetok Island

Before the arrival of the task force at Eniwetok, Phase III of the operation had been planned to include the capture of both Eniwetok and Parry Islands the day after Engebi was secured. Little was known about the defenses or garrisons of those two islands when this plan was drawn. It was hoped that information gathered at the targets would be sufficient to elaborate upon the original scheme of maneuver or to change it.

During the capture of Camellia and Canna Islands on 17 February, the V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company had captured several natives who said that a thousand Japanese soldiers were stationed on Parry and Eniwetok. Attempts to verify this information proved futile, and its reliability was doubted because the prisoners questioned seemed to have no very clear idea as to what the numbers given really meant. On 18 February Japanese documents and prisoners taken on Engebi indicated that Eniwetok Island was defended by 556 soldiers, and that Parry’s garrison came to 326, including General Nishida’s brigade headquarters.43

In view of this increase in the estimated strength of the enemy garrison on Eniwetok Island, Admiral Hill modified his orders. The original plan called for sending the 106th Infantry into Eniwetok in column of battalions, then two hours later withdrawing one battalion to support the 22nd Marines’ attack on Parry. The new order called for the two battalions of the 106th to land abreast on Yellow Beaches 1 and 2 on the lagoon shore of Eniwetok. Attached was the 2nd Separate Tank Battalion (Marine) and the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, in reserve.44 Immediately upon receipt of this change of orders,

Colonel Ayers, commanding the 106th Regimental Combat Team, called a meeting of the members of his staff and other interested officers aboard the transport Custer. There, he set forth in detail his new plan of operation. The 1st Battalion was ordered to land on the right on Yellow Beach 2 and was charged with making the main effort to the west to clear the lower end of the island. The 3rd Battalion was to land on Yellow Beach 1 and form a covering line just east of a road that bisected the island from the lagoon to the ocean shore. Only one company was to be employed for this maneuver, the purpose of which was to seal off the eastern end of the island against possible Japanese infiltration while the 1st Battalion was capturing the western end where most of the enemy defenses were presumed to be. The remainder of the 3rd Battalion was to stand in regimental reserve in readiness to assist the 1st Battalion if necessary. After the west end of the island was cleared, the 1st Battalion was then to pass through the 3rd Battalion and clean out the rest of the island.

The 3rd Battalion, whose primary job was merely to conduct a holding action, was instructed to take only the combat equipment necessary for temporary action on the island. Its orders were: “If rifle fire is drawn, don’t sit and take it if [you] ... can clean it out. But don’t try to take the rest of the island—limited movement only.”45 Two platoons of medium tanks were assigned the 1st Battalion, the third platoon to be in reserve. Light tanks were ordered to remain aboard ship.

The Assault

The scheduled time for the landing on Eniwetok was 0900, 18 February. At 0710 two cruisers and two destroyers took position on the flanks of the boat lanes and commenced to deliver fire on the landing beaches at close range. Half an hour later a third destroyer commenced delivering interdiction fire east of the landing beaches and in another thirty minutes a fourth destroyer took position off the ocean side of the island and commenced bombardment from there. The amount of naval fire placed on Eniwetok was considerably less than that for either of the other two main targets. Whereas a total of 1,179.7 tons of naval shells had been fired on Engebi and 944.4 tons were to be used on Parry, Eniwetok Island received only 204.6 tons altogether.46 Also, the attackers of Eniwetok were at a disadvantage since they did not have any preliminary artillery bombardment to support their landing.

Here as elsewhere in Eniwetok Atoll, the problem of delivering effective fire from naval ships differed from that in other parts of the Pacific. In former atoll operations, the main job for naval gunfire was to destroy heavy defenses, mostly above ground, such as pillboxes, blockhouses, and bomb shelters, all visible from the ships at close range. With a few exceptions on Engebi, this type of target was not in evidence at Eniwetok, the main defenses being covered foxholes and trench systems. Close-in direct fire could not be effectively delivered against these, because they were invisible from the ships and because at close range naval shells with their flat trajectory fire simply overshot the targets. A higher angle of fire was necessary, so Admiral Hill ordered his ships to increase their range once they had completed the destruction of all visible targets.47

Map 18: Capture of Eniwetok Island, 19-21 February 1944

At 0810 naval gunfire was checked for fifteen minutes to allow carrier planes to bomb and strafe the beaches. LCI gunboats followed with a last-minute rocket saturation of the landing area and then turned right to deliver a special rocket bombardment against the western end of the island. Meanwhile, six LSTs, each with seventeen LVTs aboard, had disembarked their contingents of assault troops at approximately 0730. There the amphtracks circled, awaiting the arrival of the medium tanks of the 2nd Separate Tank Company, which had been boated aboard LCMs the night before in the northern part of the atoll and were moving slowly through twenty-five miles of choppy water toward the line of departure off of Eniwetok Island. Fearful of a delay in the arrival of the tanks, Admiral Hill postponed H Hour fifteen minutes. It shortly became apparent that the LCMs would arrive on schedule, so at 0909 the first wave drew up on the line of departure.

On the left in the zone of the 3rd Battalion, Lt. Col. Harold I. Mizony, battalion commander, had Company L at the left and Company K on the right, with Company I following as reserve. Company L was to pivot on the pier on the left of Yellow Beach 1, turn left, and extend its line toward the ocean beaches. Company K was to open a corridor across the island behind it and then mop up in the rear of Company L’s right flank near the ocean shore. In the right zone, Lt. Col. Winslow Cornett had planned a somewhat similar deployment for his 1st Battalion landing on Yellow Beach 2. Company B was to push straight inland along the battalion

boundary until it had crossed the east-west trail about a third of the way across the island. Then it was to swing to the right until its left wing reached out to the ocean. Company A was to land on the right half of Yellow Beach 2, pivot to the right, tie in with Company B, and together the two would move west to the end of the island. Company C, in reserve, was to advance to just south of the trail and secure a perimeter there, establishing a point for the battalion command post.

At 0917, just two minutes after the scheduled H Hour, the first wave hit the beach.48 The landing plans went somewhat awry at the very outset. The island rose abruptly from the shore where a steep bluff eight or more feet high denied further progress to the LVTs. While some struggled to climb it, others remained on the beach or backed off, cluttering the landing area and tending to force later waves to come ashore beyond the assigned beach limits. Men dropped from LVTs onto the sand and obtained shelter behind the vehicles or the defilade next to the bluff, but enemy automatic and mortar fire caught some units and contributed to their disorganization. The enemy’s plan of defense required sturdy opposition to the landings themselves. Preparatory fire had left the Japanese still

Invasion of Eniwetok. Landing craft pass support warships as they fire on the beach defenses of the island.

able to resist from prepared positions directly inland from the beach and, in particular, from well-concealed positions that enfiladed parts of Yellow Beach 2.

Company B, on the left (east) of Yellow Beach 2, met difficulties at once. Its left and right flanks landed at the proper points, but the rest of the company was set ashore to the right and left of the designated positions. In front of the 3rd Platoon at the left was an enemy strong point that had not been neutralized by preparatory fire. It consisted of a spider-web network of firing pits and radiating trenches, artfully concealed by vegetation, from which automatic and rifle fire and grenades struck the troops on the shore. As the men pushed inland through the position, the Japanese struck them from the flank or rear and then shifted by underground passages to other hidden vantage points. The enemy had to be rooted out by tactics improvised on the spot.

2nd Lt. Ralph W. Hills and Pfc. William Hollowiak, caught within the strong point, at first merely lay on the ground shooting the enemy as they rose in their pits to fire toward the beach. Hollowiak found this method too slow. He got Hills to cover him while he crawled forward and fired into a hole, after which he would lift the covering frond and throw in a grenade. Then he in turn covered Hills while the 1st Platoon leader repeated the process. Hollowiak picked up a Japanese rifle and took ammunition from every dead Japanese and obtained grenades from all the wounded or dead Americans in his path. Scrambling forward in this fashion, the two men alone killed perhaps twenty of the enemy and knocked out seven or eight of the positions in fairly rapid sequence, thus neutralizing enough of the east side of the strong point so that Company K’s right wing could also press on toward the ocean.

1st Lt. Arthur Klein and one section of Company B’s weapons platoon were set ashore on the westernmost portion of the beach. They made their way with some difficulty along the shore through Company A before striking inland from that part of Yellow Beach 2 originally assigned to Company B. The section reached the road by crossing the right side of the enemy strong point from which, however, the Japanese were no longer resisting; they then waited for Company A to arrive. Klein moved eastward alone along the road until he came upon Lieutenant Hills and Private Hollowiak, leaving the rest of his group to await Company A. He joined the Company B main body, which cleared the last of the enemy positions in the defense system there with the aid of an amphibian tank and its 37-mm. gun. In the absence of the company commander, Klein took command and reorganized the elements of Company B along the road, with the exception of the group he had led ashore, starting them on the second phase of their mission. By 1145 the left flank, under Lieutenant Hills, had pushed across the island jointly with elements of Company K, had subdued another enemy defense position, and had captured five native prisoners. Contact between Lieutenant Hills’ detail and the remainder of Company B had been lost, however, during this advance. The right wing of Company B, about thirty men with rifles and carbines, was itself quickly divided into many small groups, separated by dense underbrush, and gaps also developed on both of its flanks.

Company A landed on the right (west) part of Yellow Beach 2 and struggled through a thick tangle of underbrush to the crest of the knoll on which it was to pivot to the west. Its right flank was

Machine Gun Squad Firing its .30-caliber water-cooled weapon on an enemy position

covered by a patrol of four men under S. Sgt. Joseph A. Jasinski. Although the main body of the company made no contact with the enemy until it turned, the patrol encountered the first of a series of dugout and trench defenses almost immediately. The company’s right flank also ran upon the eastern limits of these works shortly after it started inland but it was able to proceed well ahead of the hard-pressed patrol. Reinforcements, including two amphibian tanks with 37-mm. guns and some light tanks, were sent back, and the destruction of the enemy in these positions went forward rapidly. About 1330 the line from the lagoon inland was straightened.

Company C was expected to land behind Company B and to advance southward in the rear of Company B’s turning movement to the west, beyond the trail. 1st Lt. Robert T. Bates, company commander, brought part of his unit ashore in one long line on Yellow Beach 2 in the fifth and sixth waves. The beach was already badly congested. Four boatloads of Company C were accidently brought in west of Yellow Beach 2, beyond the point at which Lieutenant Klein’s section of Company B had landed. Three of the boats, a little apart from the others, were under heavy small arms fire for the last 150 yards; when the men in them started to rush across the beach, they were cut down by heavy fire from enemy machine guns. The machine guns were mounted on jutting points that permitted enfilade. Mortar fire also fell upon the attacking elements as some of the Americans sheltered behind their boats

threw grenades into the area beyond the sea wail. Out of fifty-three men in the three boats, twenty were killed, fifteen were wounded, and only eighteen escaped unhurt in a fight that lasted over four hours. They were saved from complete annihilation by the westward advance of Company A along the lagoon shore.

The 1st Platoon of Company C had proceeded from the left side of Yellow Beach 2 without mishap and took up a front-line position in one of the gaps in the Company B line. They were under the mistaken impression that Company B was actually ahead of them. Shortly before noon, the platoon engaged in a stiff fire fight with a number of Japanese entrenched in a position beyond the trail. It was joined on the right by the 2nd Platoon, Company B.

At noon, therefore, the front line of the 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry, was in the shape of an S, extending from the lagoon to the ocean. On the lagoon side, near the southwestern edge of Yellow Beach 2, the flank patrol of Company A was trying to work its way through an uninterrupted series of spider-web defenses. On the ocean side, a small detachment of Company B was digging in among the pits and trenches of an enemy position that they, with elements of Company K, had just captured. Between these two extremities, Company A extended from the lagoon to the trail, while Company C and Company B, intermingled, held a line running southerly through brush and palm grove, from trail to ocean. In the curving corridor crossing the island between the two battalions, Company K was then swinging to the eastward from the ocean side, having detached two squads to support Company B. A platoon of the 106th’s Cannon Company, with two 75-mm. guns, was also in Company B’s rear. Such was the situation when the Japanese launched a counterattack.

The Japanese Counterattack

The American plan of attack, to establish a line holding the enemy at the east while the western end of the island was swept clear for field artillery emplacements, inadvertently brought the assaulting forces inland through outposts of the main enemy defensive system. In the western end of the island, the Japanese construction that had been noted in reconnaissance photographs was in fact part of an elaborate system. Underground and surface positions, including concrete pillboxes, immobilized tanks, and wire barricades, had been prepared to resist landings on that corner of Eniwetok Island. To meet the American attack after it penetrated the island farther east, the enemy abandoned all but the most important of the positions and sent between 300 and 400 men to deliver a counterattack. Well out of sight, they moved east in the brush on the southern side of the road and when they came to the American line shortly after noon, struck it on both sides of the trail.

Detachments of the enemy hit in quick succession and with severe effect parts of the American line extending southward as far as the ocean shore from a point just north of the trail. At some points, the Japanese actually broke through before they were cut down. In the center, their assault was prefaced by a concentrated mortar barrage and pressed home with extremely heavy small arms fire. Company B’s line was temporarily broken but was re-formed under the determined leadership of Lieutenant Klein. The machine gunners of Companies B and D stood firm and finally stopped the enemy’s advance. From positions

about thirty yards west of their farthest progress, the Japanese then sent heavy automatic fire over the ground they had so recently assailed. The remnants of Company B, supported by elements of Company K and by machine guns, eventually wore the enemy down. At the extreme left of the American line, next to the ocean, a bitter five-minute hand-to-hand fight with knives and grenades checked one Japanese assault. A second charge was stopped by a supporting squad from Company K, aided by Sgt. William Toppin, a BAR man with Company I. By 1245 the counterattack had spent its force. The American line had been thinned but not broken.

Capture of Southwestern Portion of the Island

The American attack to the west was now resumed. Company A on the right wing made slow progress through the enemy positions near the lagoon, but the mingled elements of Companies C and B, even after being reorganized and supported by three Cannon Company guns, could not push through the line taken up by the enemy at the end of his counterattack. Although it steadily reduced the Japanese positions, the attacking force was unable to move forward.

At 1245 Colonel Ayers ordered the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, the reserve battalion, to land as soon as possible after 1330 to relieve the left half of the 1st Battalion line.49 It had become apparent that one battalion was not sufficient to clear the western portion of the island. The 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry, had already been ordered at 1205 to attack to the eastern end of the island,50 so the only alternative was to send in the Marines. The 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, commanded by Maj. Clair W. Shisler, USMC, was ashore by 1425, passed through the 1st Battalion about an hour later and by 1605 had established contact with Company A. The boundary line between the Marine and Army battalions was to run down the middle of the island.51

As the Marine battalion moved through the area south of the Japanese defensive positions that Lieutenant Klein’s small force had engaged for the preceding three hours, it quickly straightened the line. Movement accelerated after 1645.52

Following the relief of the 1st Battalion on the left side of the line, Company C took over part of Company A’s line on the right. Company B, after completing the reduction of a stubbornly defended pillbox near Yellow Beach 2, rested, reorganized, and eventually moved up to support the other two companies. About 1830 the swift movement of the marines on the left of the line had reached the last Japanese defensive position in the southwest corner of the island. As darkness approached, a gap existed between the Marine and 1st Battalion positions.

To deny to the enemy an opportunity for his customary aggressive night tactics, Colonel Ayers at 1850 ordered that the attack be pressed during the night.53 Colonel Cornett then ordered Company B to relieve Company A. During these last minutes of daylight, Company A decided to continue its advance, which brought it abruptly to the seashore before Company B had arrived. In the darkness, units of the three companies joined in an irregular perimeter near the beach on the western

Marines prepare to attack a Japanese defensive position. Note flame thrower, which was frequently used to rout the defenders from their dug-in positions.

corner of the lagoon shore. The Marines’ right flank rested on the battalion boundary more than a hundred yards from the 1st Battalion’s position. A gap existed through which the enemy could readily infiltrate. At 0910 a counterattack all along the Marines’ front was repulsed, but from a deep shelter that had been missed, or through the gap between battalions, one group of about thirty Japanese succeeded in striking the Marine battalion command post.54

On the morning of 20 February the action on the western end of the island was concluded with some heavy fighting. The 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, found one of the main enemy defenses, manned by a strong and determined force, at the southwestern corner of the island in its zone. A combined force of light and medium tanks, five guns from the Cannon Company, 106th Infantry, and a supporting rifle company from the 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry, joined the Marines in destroying the enemy during the day.55 The back of enemy resistance had been broken before the second night, and, except for small parties trying to infiltrate, no attacks upon the southern force were made during the night on Eniwetok Island. Early on the third morning the Marines and the tanks re-embarked in preparation for one more assault landing, that on Parry Island.

The 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry, besides sending Company A to support the Marine unit on 20 February, mopped up its zone. Next day, after the withdrawal of the Marines, the battalion ran a line across the island from the pier and mopped up to the western end. Company A, at the right, finished first and returned to the battalion area near the landing beach. Company B, in the center, reached the end of the island a little later and then went for a swim. Company C, on the ocean side, found twenty-two of the enemy in hiding and destroyed them in a fire fight that sent some bullets over the heads of Company B’s swimmers. Company B came out of the water, dressed, and rejoined the fight. The western end of Eniwetok Island was finally clear of Japanese. When the 3rd Battalion left on 22 February on the LSD Ashland to be in floating reserve for the Parry Island action, the 1st Battalion assumed responsibility for the eastern part of Eniwetok Island as well. One more mopping up of the whole island took place on the 22nd.56

Action of the 3rd Battalion

The 3rd Battalion, under Colonel Mizony, landed on Yellow Beach 1 simultaneously with the 1st Battalion at 0917 on 19 February. Company L was on the left, Company K on the right, Company I following in support. Beach conditions were quite similar to those on Yellow Beach 2. Enemy installations in the sandbank itself had been wrecked by the preparatory fire, but the damage to other covered defenses along the shore failed to neutralize them. When the assault squads of the first wave found themselves in the same sort of strong point as that holding up Company B on their right, they too had to investigate all holes. Supporting troops working over the same ground later found some of the enemy still there.

Company L, at the extreme left, readily made its way beyond the trail, but there its right wing was engaged by two pillboxes. One platoon then went on ahead to the ocean beach, arriving there at 1010. It swung left to take up the eastward-facing line, found a hole covered by a palm frond, and a grenade was dropped. Following the explosion, the sounds of a familiar Christian hymn came from within the hole. Further investigation revealed an old man, the natives’ chief, with six companions, and in another shelter nearby were twenty-six others. None had been hurt by the American fire. A sociable exchange of souvenirs and cigarettes ensued, after which the prisoners progressed to the beach.57 Company L’s line was established at the western edge of the area designated on the maps as a village. All the structures had been flattened except some concrete revetments. The enemy moved into position behind these barriers while the American line held a stationary position for over an hour, under a Japanese mortar barrage.

Company K’s progress to the ocean side was impeded first by the eastern edge of the enemy strong point on which Lieutenant Hills and Private Hollowiak were working, next by a thick tangle of underbrush beyond the trail, and finally by an especially difficult area along the ocean shore. A belt of bushes rising six to twelve feet high, growing densely in a fringe of from ten to thirty-five yards in width, paralleled that shore for most of its length. In it, the enemy had concealed firing positions from which they inflicted so much damage that the entire area had to be

combed painstakingly during the movement along the island. As Company K began to swing east, it started to work through this barrier. At the same time, some of its units were engaged in repelling the major counterattack from the west.

The attack to the east, which was begun at 1515, was undertaken by Company L on the left and by Company I on the right. The latter company passed through Company L’s right flank to take over that half of the line. Company K followed the advance as battalion reserve. After a fifteen minute air strike the attack began.58 Company L was able to sweep forward more rapidly than Company I because of the latter’s difficulties with the belt of brush along the ocean. Contact was maintained during the remainder of the day, and as night fell, Colonel Mizony pulled back Company L sufficiently to straighten the line. For the remainder of the drive along the island, the company on the right was designated as the base unit. Thus, the entire line was paced by the slow advance on the extreme right wing. Barrages from artillery and naval guns failed to solve the problem. Light tanks were brought forward to run up and down through the brush; the bushes bent over as they passed and rose back in place behind them. Sgt. William A. Forsyth of the 2nd Platoon, Company I, was sent to investigate after the tanks had run over one hidden Japanese position several times. He found what appeared to be a frond-covered hole, lifted the cover, and found two of the enemy grinning up at him. When all fire from this particular area had ceased, the whole platoon waded in and found the bodies of twenty-one Japanese.

One of the light tanks engaged in the task of reducing the enemy positions in the heavy foliage struck a land mine late in the afternoon while it was at the upper end of its run, some two hundred yards ahead of the infantry. Unable to move because of a lost track, the vehicle’s occupants remained unresponsive to every effort to communicate with them. A small patrol managed to reach the tank and banged on its side, but the occupants, sure that the noise came from Japanese, refused to unbutton. The patrol retired. Just before sunset the vehicle’s commander cautiously opened the turret, looked around and then crawled out to inspect the damage, leaving the turret open. As he reached the ground he was subjected to a fusillade of fire from several Japanese nearby and was forced to crawl, wounded, under the tank for protection. The enemy then came out of hiding and dropped a series of grenades and fired rifles into the open turret. Only two of the crew survived this attack, one of them the man lying underneath the vehicle. The 3rd Battalion had continued to advance after dark, following the orders issued by Colonel Ayers. The night was dark, but frequent illumination was furnished by mortar flares. Its progress was slow and brought it to the tank at 0200. The Japanese, using the vehicle as a fortress, put up a stubborn fight at that point. When they were finally driven off, they left over forty bodies behind them.

The line moved forward twenty-five yards farther, again ran into heavy enemy fire and, at 0430, dug in for the remainder of the night. Naval guns continued, at intervals, to illuminate the enemy area with star shells. When daylight came at 0700, both Company L and Company I renewed the attack. At 1030, after two hard fire fights with the enemy in the brush belt, Company I was relieved by Company K.

The line had reached the island’s slender waist. No strong organized resistance was met thereafter but the brush was beaten continuously and slowly. Artillery and naval gunfire furnished support and drove the enemy from a machine gun nest observed near the center of the island. At a tank ditch that crossed the island from shore to shore, the enemy left rather clearly marked channels through a field of improvised land mines, and the attack was not seriously delayed by the obstacle. Gunfire destroyed other mines ahead of the advance.59 Movement continued through thick smoke from brush fires in the center of the island, fires that detonated duds from the naval bombardment at considerable danger to American troops. During the second night, white phosphorus naval shells kept the eastern end of the island ablaze. Several casualties resulted from indiscriminate shooting and grenading in one of the company perimeters. Preceded by time fire to explode mines and harass the foe, the troops reached the tip of the island at 1630, 21 February.

Thus, in two and a half days Eniwetok Island was secured with a loss of 37 Americans killed and 94 wounded in action. Except for 23 prisoners taken, the total Japanese garrison of about 800 men was killed.60 The capture of the island had been much slower than planners had anticipated. This was in part due to the relatively small amount of preparatory bombardment (as compared with that placed on other islands in the atoll), in part to the heavy underbrush that covered most of the eastern end of the island, and in part to the cleverness with which the enemy had constructed and concealed his underground entrenchments. However, some of the responsibility for the delay must be laid to the extreme caution that the troops of the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry, displayed in their movement eastward.

Parry Island

The unexpected delay in the seizure of Eniwetok Island and the commitment of the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 106th Infantry in its reduction had caused a major change in plans for the seizure of Parry Island. Instead of a landing being made there on the same day as at Eniwetok Island, the initial invasion was postponed until the latter was secured.

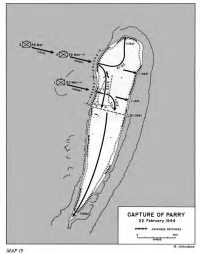

Plans and Preparations

The delay in attacking Parry Island permitted better preparation than had been possible for the assault on Eniwetok Island. The most striking contrast was in the volume of preliminary fire, for which ample incentive was found in the report of prisoners that the Japanese force there was larger than on the other islands, and in the evidence supplied by a captured map of the enemy’s prepared defenses.61 For three days bombs and naval and artillery shells pounded the target. Naval shells dropped on the target totaled 944.4 tons, considerably more than the weight delivered on Eniwetok Island; the weight of artillery shells came to 245 tons, and bombs added 99 tons more.62 The 104th Field Artillery Battalion had begun landing on Eniwetok Island late in the afternoon of 19 February and had completed its registration on Parry by noon the next day.63 The 2nd Separate

Parry Island under preliminary bombardment

Pack Howitzer Battalion had landed on Japtan Island before noon on 20 February and joined in the preparation.64

The extra time was also used to give the landing forces of the first few waves some rest on LSTs. The 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, was withdrawn accordingly from Eniwetok Island. Since the defense battalion had arrived at Engebi, the 1st and 2nd Battalion Landing Teams of the 22nd Marines were brought from there to southern Eniwetok in transports. To the main body of the landing troops, the two reconnaissance units that had completed the investigation of all the small islands were attached. The task group reserve was to consist of the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry, kept in readiness afloat, and a battalion consisting of five improvised rifle companies, each of a hundred men, drawn from the 10th Marine Defense Battalion shortly after its arrival on 21 February.65

The expedition was running low on ammunition and weapons. Naval and artillery shells were carefully apportioned. From all the ships, available grenades and demolition charges were gathered. To supplement them, 775 grenades and 1,500 percussion caps were flown in from Kwajalein while the attack was in progress. Other units surrendered BARs and rifles to equip the 22nd Marines.66

The regiment’s plan of attack was completed and approved during the afternoon of 21 February in time to be fully understood by the participants. At 0900 the following morning, the touchdown was to be

Map 19: Capture of Parry, 22 February 1944

made on about six hundred yards of sandy beach just north of the pier on the lagoon side. From right to left, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 22nd Marines, would go in abreast in the hard-worked LVTs and landing craft, and land between two areas developed as strong points by the defenders. The 3rd Battalion would be in regimental reserve. The amphibian tanks of the 708th Amphibian Tractor Battalion would, for the third time at Eniwetok Atoll, slightly precede the waves of assault troops on the flanks and in the center, to deliver cross fires against enemy resistance at the beach. Medium tanks were to land in the third wave in LCMs. After seizing the beachhead, tanks and infantry were to press forward to the ocean side of the island, which at this point was about five hundred yards eastward from the landing beaches. An artillery barrage across the island south of the pier would block reinforcement from the southern part of the island, while the two portions of the attacking force prepared for the next phase of the operation.67 The 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marines, at the left, was to clear the Japanese from the northern lobe of the island while the 1st Battalion would attack to the right and capture the southern portion.

The Seizure of Parry

The preliminary naval and air bombardment of Parry Island opened at dawn on 22 February. The battleships Tennessee and Pennsylvania took positions only 1,500 yards north of the landing area and not only mauled it with their big guns but also covered it with their 40-mm. automatic weapons batteries. From the other side of the boat lanes, the heavy cruisers Indianapolis and Louisville and the destroyer Hailey also fired. Smoke and dust blew out over the lagoon without masking the target for the battleships but with serious consequences for the other three warships and for the landing craft that started ashore at 0845. Three of the LCI(G)’s that approached through the haze with the first wave to fire rockets were hit by 5-inch shells from Hailey, killing thirteen and wounding forty-seven.68 Some LVTs landed outside the designated beaches, thus widening the front and making necessary the suspension of artillery fire in their vicinity. Other tractors crisscrossed or fell behind, so that the landing teams had difficulty in reorganizing on the beaches.

While the tractors made their fifteen minute run from the line of departure, two formations of planes bombed Parry in the last of 219 sorties made during the six days of action at Eniwetok Atoll. This time they only bombed the island, omitting strafing runs because of the type of defense trench systems on Parry Island.69

The first troops struck Green Beaches 2 and 3 at 0900, with a wave of tractors and one of LCMs carrying medium tanks directly behind them. Heavy machine gun and mortar fire greeted the marines at the water’s edge. As they tried to form an assault line, enfilading machine gun fire also struck them from a concealed position on the pier at the right. The machine guns were silenced by grenades and by shells from the amphibian tanks. Then the assault passed inland. Some of the enemy in trenches and foxholes in the dune line on the beach, men who had survived the bombardment, were overcome in hand-to-hand fighting. Most of the Japanese had either taken refuge in covered defense

systems farther inland or had been beyond the range of the main preparatory fire in positions along the ocean shore.70

Prepared defenses on Parry were much like those on Eniwetok Island.71 Foxholes, covered shelters, and gun emplacements, sometimes open but often covered, were organized into strong points fronting and flanking the most favorable landing beaches. They extended in depth as much as the size of the island would permit. Spider-web systems provided much the same difficulty as on Eniwetok Island. A large shelter would be excavated, then lined and roofed with heavy coconut logs. Corrugated iron sheets, sand, and palm fronds covered it. In a circle around this shelter, covered foxholes of varying depth were placed from ten to fifteen feet apart. Radial trenches and tunnels connected each of these holes with the central position, while peripheral tunnels connected them with each other. Often oil drums with the two ends removed, when placed end to end and covered with earth, served as tunnel passages. Foxholes were also dug at the bases of coconut palms, hidden by the roots. In addition to these covered positions, on Parry Island many open trenches had been prepared along the shore.

Marines found the best method of securing areas containing such defense systems to consist of three phases. Infantry-tank teams first pushed rapidly ahead to assigned objectives. Demolitions and flame thrower parties followed and cleared out each hole, trench, and shelter. Small teams of three or four men worked together in covering such operations, then mopped up the remaining Japanese in the position. Among the demolitions teams, the favorite weapon was a hand grenade taped to a block of explosive.

About 1000, shells from Japanese 77-mm. field pieces began to strike from the right flank among the leading units of the 1st Battalion, 22nd Marines. Neither an air strike nor naval gunfire could be directed on the source without danger to friendly troops and tanks, but the urgency of the request for such support finally prevailed. Five salvos from 5-inch naval guns, although damaging to our troops and tanks, did smash the enemy’s guns and break his resistance to the advance. Before 1010 the front line had pushed forward about three hundred yards inland from the beach. Additional forces were being committed or made ready. The 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marines, started ashore at 1001 to take position on the right half of what was to be the southward-moving line of attack. From Eniwetok Island, the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry, was preparing to move to Parry as reserve. The two reconnaissance companies joined the attack early in the afternoon, but the 106th Battalion was to remain afloat.72

At 1330 the 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marines, had reached the northern end of Parry and was mopping up while the other two battalions were in line abreast due east of the pier and about to begin their main attack to the south. A fifteen-minute barrage by field artillery from the adjacent islands and by naval guns on the enemy’s flanks had just been concluded. The southern force extended across the island, with the medium tanks about a hundred yards in front of them.73 Ahead of the tanks, the destroyer Hailey fired on call until it was hitting only the most southern target areas. As the attack jumped off, the troops pressed through thick underbrush and

continued over an area in which land mines had been strewn promiscuously. Overrunning a series of trench and foxhole defenses, they gathered speed until, at 1930, resistance ceased and the end of the island was in sight. At that time the island was reported secured. The two battalions dug in for the night, prepared to mop up in the morning.