Chapter 6: Capture of Aslito Airfield

Counterattack: Night of 15-16 June

Nightfall brought little hope of respite to the battle-weary marines on Saipan as they dug in on their narrow strip of beachhead with the Philippine Sea at their backs and a vengeful and still potent enemy lurking in the dark ahead. All had been alerted to the strong possibility of a night counterattack. Few doubted that it would come – the only questions being where, when, and in what force.

In fact, by midafternoon of the 15th the Japanese high command on Saipan had already issued orders to drive the Americans back into the sea before daylight next day. To Tokyo, 31st Army radioed optimistically, “The Army this evening will make a night attack with all its forces and expects to annihilate the enemy at one swoop.”1 To the troops, the order went out, “Each unit will consolidate strategically important points and will carry out counterattacks with reserve forces and tanks against the enemy landing units and will demolish the enemy during the night at the water’s edge.”2

First to feel the effects of these measures was the 6th Marines, 2nd Division, which held the left flank of the beachhead.3 About 2000, a large force of Japanese infantry, supported by tanks, bore down from the north along the coastal road.4 With flags flying, swords waving, and a bugle sounding the Japanese fell upon the marines’ outposts. Unhappily, the 2nd Marine Division had been able to land none of its 105-mm. howitzer battalions during the day so the regiment under attack had only one battalion of 75-mm. pack howitzers to support it. However, naval star shells fired from American destroyers lying close off the coast silhouetted the attackers as they approached, and the first attack was stopped by the withering fire of machine guns and rifles, assisted by naval 5-inch guns.

A second, though smaller counterattack developed in the same area around 0300 on the 16th. It, too, failed to penetrate the marines’ lines. Finally, just before daylight another organized force of infantry and tanks rolled down the road from Garapan. Again, the Japanese were repulsed, this time with the help of five American medium

tanks. By dawn the full measure of the enemy’s failure was revealed. About 700 Japanese lay dead just to the north of the 6th Marines flank.

In the zone of the 4th Marine Division, enemy countermeasures on the night of 15-16 June were less well organized and less powerful. Also, the 4th Division had all three of its 105-mm. howitzer battalions ashore by nightfall and was in a better position to resist.5 On the southern beaches, small groups of enemy soldiers, one shielded by a spearhead of civilians, hit once at 0330 and again an hour later. Both thrusts failed, with much of the credit for the successful defense going to a battalion of 105-mm. howitzers.

The most vulnerable spot in the 4th Marine Division’s zone of action, of course, lay on the exposed left flank, where the 23rd Marines had not yet tied in with the 2nd Division to the north. All through the night Japanese artillery fire swept the beaches in this area from one end to the other. From dusk to dawn small groups of the enemy managed to filter through frontline units only to be wiped out in the rear areas by either infantry or shore party personnel. Among the latter were the 311th Port Company and the 539th Port Company. These were attached to the 4th Marine Division and were the first Army units to be put ashore on Saipan. Finally, at 0530, about 200 Japanese launched an organized attack. Through the gap it came, apparently aimed at the pier at Charan Kanoa. It too was stopped. Only a few individual enemy soldiers reached the beaches, where they were disposed of by members of the shore parties.

One important factor that contributed to the marines’ success in warding off these early morning counterattacks was the bright illumination provided by the Navy. The battleship California, assisted by two destroyers, cruised off the west coast of Saipan all night firing star shells to light up danger spots from which surprise attacks might be launched. That they were highly successful was later confirmed by 31st Army headquarters itself, “The enemy is under cover of warships nearby the coast; as soon as the night attack units go forward, the enemy points out targets by using the large star shells which practically turn night into day. Thus the maneuvering of units is extremely difficult.”6

In spite of precarious holds on both the extreme flanks and the gap in the middle between the two divisions, the marines therefore succeeded in maintaining their positions and thwarting all major efforts to drive them back into the sea. Those few Japanese who managed to infiltrate behind the lines were wiped out without causing any considerable damage. The enemy plan of maneuver had relied in the main on repelling the American assault troops at the beach by counterattacks with artillery and tanks in support. As dawn broke on the morning of 16th June, the miscarriage of the Japanese first basic defense plan was more than evident.

Consolidating the Beachhead: 16 June

Daylight brought to the grateful marines hugging the beaches a respite at least from

the fearful dread of night counterattacks and infiltration. But immediate and pressing duties lay ahead. No more than a half of the designated beachhead (west of the O-1 line) was under their control. (See Map 4) Afetna Point had not been secured, which meant that a gap of about 800 yards lay between the two divisions. The tip of Agingan Point, the southwest extremity of the island, still remained in enemy hands. Finally, an unknown number of Japanese could be presumed to be still lurking behind the lines, ready to ambush the unwary and harass the attacking troops from the rear.

On the left (north) flank, the 6th Marines held fast and consolidated the positions won the day before. South of the 6th, the 8th Marines made rapid progress in its zone of action. Afetna Point offered little resistance, and the few Japanese left there after the previous night’s counterattack were quickly mopped up. By 0950 the right flank company of the 2nd Marine Division had reached Charan Kanoa pier and about two hours later established contact with the left flank of the 4th Marine Division.7

The heaviest fighting of the day took place in the zone of the 4th Marine Division, especially on its right flank. Orders called for the capture of all ground lying west of the O-1 line along Fina Susu ridge by nightfall, but the assault was held up until 1230 while lines were rearranged. On the division right, the 25th Marines encountered considerable opposition from machine guns, mountain guns, and the antiaircraft weapons guarding the western approaches to Aslito field. By the end of the day’s fighting the 25th had overrun Agingan Point and accounted for five machine guns, two mountain guns, and approximately sixty Japanese combatants. Meanwhile, the left and center regiments, the 23rd and 24th, moved abreast of the 25th Marines and by 1730, when the fighting was called off, the lines of the 4th Marine Division rested generally along the Fina Susu ridge line.8

On the same day, to the north of the main area of fighting, additional elements of infantry and artillery were being landed on the beaches controlled by the 2nd Marine Division. By 1000 of the 16th those men of the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, that had not come ashore on D Day were landed and took positions on the division left.9 Around 1600 the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, which had originally been scheduled to invade Magicienne Bay,10 was landed, minus its heavy weapons, on the 2nd Marine Division’s beaches. The heavy weapons were subsequently dropped by parachute from carrier torpedo planes, but because the planes flew at a low altitude the equipment was almost completely destroyed.11

At the same time that the remaining infantry elements of the 2nd Marine Division were being dispatched shoreward, the two 105-mm. battalions of the 10th Marines were also going into position in the area.12 About 1600 the 4th Battalion landed just north of Afetna Point and set up its batteries to support the 8th Marines, while an

hour later the 3rd Battalion came ashore on RED Beach 3 behind the 6th Marines.13

At 1515 on the 16th, General Harper, USA, commanding the XXIV Corps Artillery, left the flagship Cambria and an hour later arrived on BLUE Beach 2 just south of Charan Kanoa. There, he set up his command post about a hundred yards inland from the southern edge of BLUE Beach 2, and before dark advance parties of the 149th and 420th Field Artillery Groups, the 225th and 531st Field Artillery Battalions, and elements of his staff reported to him there. No corps artillery equipment came ashore on 16 June, and the advance elements spent an uneasy night dug-in in a partially destroyed enemy gasoline dump.14

Night of 16-17 June

General Saito’s failure to “drive the enemy back into the sea” the first night after the landing did not discourage him from making a second try. During the afternoon of the 16th he ordered the 136th Infantry Regiment and the 9th Tank Regiment to launch a coordinated attack at 1700 toward the radio station that now lay behind the lines of the 6th Marines. Another, though un-coordinated, attack was to be carried out by the Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force from the direction of Garapan.15

The scheduled hour came and passed, but the units assigned to the task were apparently too disorganized to carry it out on time. Meanwhile, the marines were able to prepare their night positions undisturbed except by artillery and mortar fire.

About 0330 the Japanese struck – chiefly against the 6th Marines. No less than thirty-seven Japanese tanks were involved, and perhaps a thousand infantrymen. They approached the American lines through a ravine that cut westward through the mountains toward the radio station. The tanks came in groups of four and five, each with a few riflemen aboard. Each group of riflemen carried at least one light machine gun. When they came within range, they were met by a furious barrage of fire from the marines’ artillery, machine guns, mortars, bazookas, and rifles. Within an hour, a good percentage of the tanks had been either destroyed or incapacitated. Although the escorting infantrymen kept up the fight until about 0700, their efforts were fruitless. By the end of the battle the Japanese had lost at least twenty-four and possibly more of their tanks and an uncounted number of infantrymen. Saito’s second counterattack was a total failure.

Change of Plans

The initial plan for the capture of the Marianas had set 18 June as the tentative date (W Day) for the landing on Guam, which was to constitute Phase II of the FORAGER operation. On the night of 15 June, after it appeared that the marines could hold their narrow beachhead on Saipan, Admiral Spruance confirmed this date, and preparations were set under way for an immediate invasion of Guam. But before daybreak of the 16th, Spruance received new information that caused him to reverse his own decision.

At 1900 on the evening of 15 June, the U.S. submarine Flying Fish sighted a Japanese task force of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and aircraft carriers making its way eastward through San Bernardino Strait in the central Philippines. Four hours later another submarine, Seahorse, reported another enemy task force about two hundred miles east of Leyte Gulf steaming in a northwesterly direction.16 It was clear that the Japanese Fleet was preparing to do battle and that the U.S. Fifth Fleet would be called upon to take the necessary countermeasures.

The next morning Admiral Spruance, in the light of these developments, postponed indefinitely the date for the invasion of Guam and joined Admiral Turner aboard Rocky Mount off the coast of Saipan. Together, Turner and Spruance decided that unloading should continue at Saipan through 17 June, that as many transports as possible would be retired during the night and that only those urgently required would be returned to the transport area on the morning of the 18th. The old battleships, cruisers, and destroyers of the Saipan bombardment group would cover Saipan from the westward, and Admiral Conolly’s force would be withdrawn well to the eastward out of any presumable danger from enemy naval attack. Certain cruiser and destroyer units heretofore attached to Admiral Turner’s Joint Expeditionary Force were to be detached and directed to join Admiral Mitscher, who would carry the brunt of the attack against the approaching enemy fleet. Patrol planes based in the Marshalls were to be dispatched forthwith and would prepare to make night radar searches as far as 600 miles west of Saipan. Finally, Admiral Mitscher was ordered to discontinue all support aircraft operations over Saipan and restrict his carrier air operations on 17 June to searches and morning and afternoon neutralization strikes on Guam and Rota. Thus were begun the preparations for the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

First Landings of the 27th Infantry Division

The imminence of a full-scale naval battle also demanded an immediate decision regarding the disposition of the troops of the 27th Division, which had been assigned to corps reserve. The division had sailed from Oahu in three separate transport divisions under command of Rear Adm. William H. P. Blandy and was scheduled to reach Saipan the day after the main landings. On 15 June, while still en route to the objective, the 106th Regimental Combat Team (RCT) was detached from the division and ordered to join Admiral Conolly’s Southern Attack Force as the reserve force for the Guam invasion, which at that time was still scheduled to take place on 18 June. Shortly before noon of the 16th, when the ships carrying the other two regiments were still about thirty miles from Saipan, General Ralph Smith, aboard the transport Fremont, was notified by radio that the division, less the 106th RCT, was to land as soon as practicable over the beaches held by the 4th Marine Division. The general himself was ordered to report to Cambria, flagship of Admiral Hill and headquarters of Brig. Gen. Graves B. Erskine,

USMC, chief of staff to Holland Smith.17

Aboard Cambria, General Ralph Smith received his orders to land his division artillery as soon as possible to support the 4th Marine Division. The 165th Regiment was to land immediately and move to the right flank of the 4th Marine Division, to which it would be attached. The 105th Regiment would follow. The 106th was to remain afloat as reserve for the Southern Landing Force for the Guam operation, which by now had been postponed indefinitely. As soon as the 105th Regiment and other elements of the division were ashore they were to unite with the 165th and relieve the 4th Marine Division on the right zone, which included Aslito airfield.

General Ralph Smith returned to his own flagship about 1930, where the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Ogden J. Ross, and the 165th Regiment commander, Col. Gerard W. Kelley, were anxiously awaiting him. Kelley had already instructed his executive officer, Lt. Col. Joseph T. Hart, to land the regimental combat team over BLUE Beach 1 immediately south of the Charan Kanoa pier. Ross and Kelley were then ordered to go ashore, establish contact with the 4th Marine Division, and to make whatever arrangements were practicable during the night.

The two officers, accompanied by a small advance group, left Fremont about 2100. The coxswain of their small boat lost his way, and, after much fumbling in the dark and many futile inquiries among other landing craft in the area, the party finally located a guide boat to steer them through the channel to BLUE Beach 2, where they waded ashore about 0130.

In spite of the darkness and confusion on the beach, they succeeded in locating the command post of the 23rd Marines about 300 yards south of the point where they had landed. General Ross raised 4th Marine Division headquarters by telephone and was informed that the 165th Regiment was expected to move to the right flank of the line and jump off at 0730. By this time it was 0330 and the Army troops were scattered along the beach over a three-mile area. General Ross and Colonel Kelley immediately set forth to locate the command post of the 4th Marine Division. There, Kelley was ordered by the division chief of staff to pass through the lines held by the 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines, and relieve on his left elements of the 25th Marines. Jump-off hour for the attack toward Aslito field was confirmed as being 0730.

Meanwhile, Colonel Kelley had established telephone contact with his executive officer, who reported that the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 165th Infantry had landed.18 After getting his orders, Kelley joined the two battalions and moved them south along the road running down the beach from Charan Kanoa. Just before dawn they took positions along the railroad embankment paralleling and east of the coastal highway and about 1,000 yards behind the line of departure. As the first

glimpses of light appeared in the eastern sky before them, they prepared to jump off in support of the 4th Marine Division.

During these same early morning hours, three of the 27th Division’s four artillery battalions were also moving toward shore. The 105th Field Artillery Battalion landed at BLUE Beach 1 at 0515 and by 1055 was in position and ready to fire in support of the 165th Regiment. The other two field artillery battalions (the 106th and the 249th) came ashore somewhat later but were registered and ready to fire by about the same time. The fourth battalion, the 104th Field Artillery Battalion, remained afloat and detached from division artillery.19

D Plus 2: 17 June

165th Infantry

The immediate objective assigned to the 165th Infantry, which was attached to the 4th Marine Division, was Aslito airfield and as much of the surrounding area as could be secured in a day’s fighting. Before that could be accomplished, the regiment would have to take the small village that lay on the boundary line between its two battalions, pass through a series of densely planted cane fields, and seize the ridge that ran in a southwesterly direction along most of the regimental front and that commanded the western approaches to the airfield. The ridge at its highest points was about 180 feet. The distance between the line of departure and the westernmost point of the airfield along the regiment’s line of advance was roughly 1,500 yards.

Colonel Kelley placed his 1st Battalion on the right, his 2nd on the left. Maj. James H. Mahoney, commanding the 1st Battalion, disposed B Company on the left, and A Company on the right just inshore of the southern coast of the island. Lt. Col. John F. McDonough put his E Company on the right and G Company on the left, tying in with the 25th Marines.20

The 1st Battalion crossed the line of departure at 0735, the 2nd about fifteen minutes later.21 Company A, on the right, immediately ran into a fire fight. Three Japanese pillboxes located just inland from the beach opened fire on the advancing troops and were not eliminated until an amphibian tank had been called in to assist and engineers were brought up to place shaped charges and scorch out the enemy inside with flame throwers.

Along the rest of the regimental line the troops ran into no difficulty until they approached the small settlement that lay on the boundary line between the two battalions. As B Company tried to skirt south of the village, it came under simultaneous fire from the direction of the village itself and from the ridge to the eastward. 1st Lt. Jose Gil, B Company’s commander, called for an air strike at 0955, but five minutes later canceled the request in favor of artillery fire from the 14th Marines.22

For the next two hours the whole line was more or less immobilized. It had become apparent that the ridge line in front was strongly held by the enemy. The ridge itself was covered by sparse undergrowth and the approaches to it were all across open cane fields. The cane offered some

Narrow-gauge railroad near Charan Kanoa. Infantrymen of the 1st and 2nd Battalions wait for the jump-off signal, 17 June

cover from enemy observation as long as the terrain was level, but entrenched as they were on the hill above these fields, the Japanese could follow every movement made by the Americans approaching below them.23

By noon Colonel Kelley had more troops available. The 3rd Battalion, part of which had remained aboard its transport while the other part spent the night offshore in small boats, was finally landed and assembled during the morning.24 Company I was ordered to report to the 1st Battalion commander to act as reserve in place of C Company, which was now to be committed to the support of Company B.

At 1150 the 1st Battalion moved off again in the attack with A Company on the right, B on the left, and C to the rear of B. At 1230 the 2nd Battalion jumped off following a fifteen-minute artillery preparation.25 Immediately, the 1st Battalion came under a concentration of mortar and machine gun fire from the high hill that marked the southern extremity of the ridge line. For the next hour and fifteen minutes this position was pounded by the field pieces of the 105th and 249th Field Artillery Battalions as well as by naval gunfire. At 1414 the attack was resumed.26

Soldiers watch destruction of a pillbox, the last of three that had slowed their advance toward Aslito airfield on 17 June

By 1535 Company A had gained the crest after losing three men killed and four wounded.27 About an hour later it was joined by two platoons of B Company, but the third platoon got involved in a fire fight in the cane fields below and failed to reach the summit during the rest of the day.28

Meanwhile, a gap had developed between Companies B and E, and the 1st Battalion commander ordered Capt. Paul Ryan to pull his C Company around to the left of B. Ryan was ordered to make a reconnaissance to determine whether he could move to the right behind A Company and up the ridge by the same route it had taken. Once on the ridge, it was supposed that he could move his company directly to the left and take position on the left of Company B. Ryan made the crest with about half of his second platoon, but the rest of his company failed to reach the objective.29

While Company A and most of Company B on top of the hill were digging in and Company C was attempting to reinforce them by various routes, the Japanese again struck. Starting about 1725, the enemy managed to work his way between B Company and the 2nd Battalion and commenced to pound the hill with mortars and dual-purpose guns from the southern tip

Reinforcements moving inland. Men of the 3rd Battalion, 165th Infantry, landed on 17 June and proceeded directly to assigned areas

of the airfield.30 After about half an hour of this, both Lieutenant Gil and Capt. Laurence J. O’Brien, commander of Company A, decided to move off the hill.31

Captain O’Brien moved over to his extreme left and ordered his platoons to withdraw by leapfrogging. The 3rd Platoon was to pull back behind the 2nd while the latter covered, and then the 2nd was to pull back below the ridge while the 1st covered. The 1st Platoon eventually withdrew down the hill while O’Brien himself covered its movement. The company commander was the last man down over the cliff.

Meanwhile, Captain Ryan, commanding Company C, decided to move off to the left to reinforce B Company and hold at least part of the hill if possible. His attitude was reflected by one of his men, Pfc. Cleve E. Senor: “I fought all day for this ridge,” Senor is reported to have said, “and by God I’ll help hold it.” Both Senor and Captain Ryan were killed in the attempt, and the C Company platoon joined Company A in its withdrawal to the beach.32

Captain O’Brien led most of the withdrawing battalion back along the southern beach for a distance of about 1,400 yards, then cut inland where he met guides from battalion headquarters. Shortly after 2000 he reached the command post with elements of all three companies and dug in for the night practically at the line of departure from which the companies had attacked in the morning. Except for scattered elements that remained dug in along the approaches to the ridge, progress in the 1st Battalion’s zone of action had been

nil.33 Casualties for the day’s fighting in the battalion were reported as 9 killed and 21 wounded.34

The 2nd Battalion had been more successful. After the 1230 jump-off, E Company, on the battalion right, was immediately hit by an enemy artillery barrage that killed three men and wounded four others. Except for the 1st Platoon, the whole company retired to the extreme west edge of the village that lay on the battalion boundary line and for the next hour reorganized its scattered elements and evacuated its wounded. The 1st Platoon, however, instead of withdrawing when the artillery barrage hit, rushed forward in an effort to take concealment in the heavy cane at the foot of the ridge line. From there it began to move on to the ridge itself, but after the leading squad was cut off by Japanese fire, the rest of the platoon halted.

Capt. Bernard E. Ryan, the company commander, had been with the forward elements of the 1st Platoon when his company was hit and was already in the cane field making a reconnaissance forward.35 With two of his men, he made his way through the cane and up to the top of the ridge. For thirty minutes they waited in vain for the rest of the platoon to come up, and when it finally appeared that they were isolated, Ryan decided to conduct a reconnaissance. For three hours this officer and his two men wandered around the hilltop observing the enemy from a distance sometimes of only thirty yards. He ordered one of his men, S. Sgt. Laurence I. Kemp, to carry the information gained back to the company executive officer. Kemp, equally fearful of friendly and enemy fire along the return route, solved his dilemma by tying a white handkerchief to the barrel of his rifle, executing a right shoulder arms, and marching safely down the hill in full view of both the enemy and his own troops.

Upon receiving Kemp’s information the battalion commander immediately requested reinforcements. Colonel Kelley released F Company, which was then moved into the line to the left of E. Both companies jumped off at 1610 behind a screen of heavy mortar, small arms, and automatic weapons fire.36 Within thirty minutes they reached the ridge line about two hundred yards west of Aslito field and began to dig in.37

On the extreme left of the battalion front, Capt. Paul J. Chasmar’s G Company met with little difficulty. By 1416, less than two hours after the jump-off, the company had reached the ridge line and commenced to dig in.38 Chasmar sent two patrols onto the airfield. They investigated the installations along the west side of the field and up to the south edge of the stretch without running into opposition. About 1530 temporary contact was established on the left with the 25th Marines, which had by this time penetrated into the building area north of the airfield proper.39

Thus, by the end of 17 June the 2nd Battalion had succeeded in pushing about

1,300 yards from the line of departure, was firmly dug in just two hundred yards short of Aslito airfield, and was in a good position to attack the field the following morning. In the day’s fighting the battalion had lost six killed and thirty-six wounded.40 It failed to attack the airfield on the 17th only because of regimental orders to the contrary. Colonel Kelley decided that in view of the difficulty encountered by his 1st Battalion on the right flank, it would be unwise for the 2nd Battalion to push forward any farther. From its positions on top of the ridge line commanding Aslito, the 2nd Battalion “had an excellent field of fire against any possible counterattack,” so the regimental commander ordered it to hold there for the night and to resume the attack against the airfield the next day.41

4th Marine Division

To the left of Colonel Kelley’s regiment the 25th Marines jumped off at approximately the same time in columns of battalions. Against light resistance the regiment pushed rapidly ahead to its O-2 line. Because of the marines’ more rapid progress, a gap developed between them and the 2nd Battalion, 165th Regiment, that was filled by two companies of marines. By midafternoon the companies had searched the building area north of the airfield proper and sent patrols onto the field itself. When Colonel Kelley’s determination not to attack the airfield until the 18th became known to the 25th Marines, its 3rd Battalion was shifted to the north side of the airfield, facing south, and as it dug in for the night there was no contact between the marines and the Army unit.42

In the center of the 4th Marine Division’s line, progress was more difficult. The 24th Marines jumped off on time about 0730. In spite of continuous fire from antiaircraft guns located east of the airfield, the right flank battalion reached the foot of the ridge line quickly and by noon commenced the ascent. By 1630 the battalion commander reported that his men were digging in on the O-2 line. In the center and to the left enemy resistance was even stronger, and after reaching the approaches to the ridge by late afternoon, the marines withdrew a full 600 yards before digging in for the night.43

To the 23rd Marines on the division’s left flank fell the hardest fighting in the 4th Marine Division zone for the 17th. On the right, the 2nd Battalion made fairly rapid progress against light opposition, but on the left, the 1st Battalion was not so fortunate. Having once cleared Fina Susu ridge, the marines started to advance across the open ground to the eastward but were quickly pinned down by heavy mortar and enfilade machine gun fire from their left front. After retiring to the ridge line to reorganize, the battalion pushed off again at 1500 after a ten-minute artillery fire. Again the attack was stopped. Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion on the right had been pushing steadily forward and contact was lost between the two battalions. Even more serious was the 600-yard gap on the left between the 23rd Marines and the right flank of the 2nd Marine Division. From this

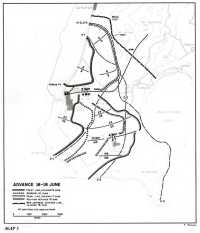

Map 5: Advance 16-18 June

area came most of the enemy fire, and the failure of the two Marine divisions to close this gap early in the day seriously endangered the flanks of both.

As night approached it became apparent that, with the advance of the 2nd Battalion

105th infantrymen wading in from the reef on 17 June

and the delay of the 1st, the right flank was extended and the left retarded so that it was impossible to close the gap with the units then on line. Consequently, the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines, was ordered to tie in the flanks of the two. Later, the 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines, was attached to the 23rd Regiment and under cover of darkness was moved into position to relieve the 3rd Battalion, 23rd Marines, tie in, and defend the gap between the two leading battalions. But between the two Marine divisions as they dug in for the night, the wide gap in the area around Lake Susupe still remained unclosed.44

2nd Marine Division

In the zone of the 2nd Marine Division, the day’s plan called for an attack by the 2nd and 6th Regimental Combat Teams to the northeast, while the 8th Marines, on the division right, was to drive due east toward the O-1 line.45 (Map 5.) The jump-off hour was originally scheduled for 0730 but was subsequently changed by General Holland Smith’s headquarters to 0930. Word of the change, however, failed to reach division headquarters in time, so the troops crossed the line of departure according to the original schedule, following a 90-minute intensive preparation by aerial bombardment, naval gunfire, and artillery shelling.

On the extreme right, the marines of the 2nd Division met with the same problems that were besetting the left flank of the 4th Division, and more besides. The 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, attached to the 8th Marines, had first to slosh its way

through the sniper-infested swamp that ran about 1,000 yards north of Lake Susupe.46 Directly east of the swamp was a coconut grove from which periodically came enemy mortar fire, described in the division action report as “bothersome.” Northeast of the coconut grove was a high hill on which the Japanese were entrenched in caves, and beyond this on a sharp nose was a series of heavily manned positions.

Throughout the day the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, was unable to seize the coconut grove and in fighting for it the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Guy E. Tannyhill, was wounded and had to be evacuated. By late afternoon the battalion, with the help of four tanks of the 2nd Marine Tank Battalion, succeeded in taking the hill to the north of the grove where it dug in for the night. Meanwhile, the other two assault battalions of the 8th Marines had reached their objective line with little difficulty and were tied in for the night with the 6th Marines on their left.

The 6th Marines had jumped off on schedule at 0730 and soon after 0900 had reached its objective line, encountering little resistance on the way. Further progress was held up because of the danger of overextending its lines as a result of the relatively slow progress of the 8th Marines on the right.

The 2nd Marines, on the division left, regulating its advance by that of the regiment to its right, moved forward at 0945 in a column of battalions. By 1020 the leading battalion had advanced four hundred yards against light resistance. By 1800 the regiment had reached its objective line, which was coincident with the Force Beachhead Line47 in its zone and lay only a thousand yards from the southern outskirts of the town of Garapan.

Landing Reinforcements

At 0605 on the 17th, Col. Leonard A. Bishop received orders to land his 105th Regimental Combat Team as soon as boats were available.48 By 0845 the 1st Battalion was loaded and headed for the beach; the other two followed during the morning.49 However, because of low tide and the heavy congestion in and around the Charan Kanoa channel, the troops had to be landed piecemeal. Not until late afternoon were all of the infantrymen ashore. That evening the 2nd Battalion was attached to the 4th Marine Division as reserve, and the 1st Battalion was attached to the 165th Infantry and moved to an assembly area just west of Aslito field. Also, the 27th Division Reconnaissance Troop landed and commenced to establish an observation post area running from Agingan Point about 1,500 yards along the southern shore. The rest of the 105th Regiment remained in bivouac in the area of YELLOW Beach 3 during the night.50

The slowness with which the 105th Regiment was landed brought one later embarrassment to that unit. In view of the bottleneck at the Charan Kanoa channel, orders were issued shortly after noon to stop unloading equipment through the channel until the congestion had been

cleared up.51 This caught most of the regiment’s organizational equipment still aboard the transport Cavalier. That night Cavalier, along with most of the other transports, retired eastward after an air raid warning. Meanwhile, the Japanese fleet was reported to be moving toward Saipan. In the light of these circumstances, Cavalier was ordered to stay out of the danger zone and did not return until 25 June to continue unloading.52 As General Ralph Smith later testified:

The 105th Infantry was thus placed under great handicap in operating as a regimental unit. It had very little communication equipment or personnel ashore, either radio or telephone. It had almost no staff facilities or blackout shelter such as regimental headquarters is compelled to use if orders arrive after dark.53

North of the 27th Division’s beaches other important elements were coming ashore on the 17th. General Holland Smith left Rocky Mount in midafternoon and at 1530 set up the Northern Troops and Landing Force command post at Charan Kanoa. General Harper, corps artillery commander, moved his command post to a point about 200 yards inland from YELLOW Beach 2, and advance parties of the 532nd Field Artillery Battalion got ashore.54

Night of 17-18 June

Compared to the first night on Saipan, that of the 17th was quiet for the American troops in their foxholes. Only in the zone of the 2nd Marine Division did the Japanese exert themselves. Around midnight, they attempted to breach the Marine lines near the boundary between the 6th and 8th Regiments. About fifteen or twenty Japanese overran two machine guns, but the attack was shortly stopped. For a brief time the enemy penetration destroyed contact between the two regiments, but the gap was quickly filled and the lines were restored.55

A more serious enemy threat occurred on the morning of the 18th in the form of an attempted counter-amphibious landing. A month before the American landings, 31st Army had established a force consisting of the 1st Battalion, 18th Infantry, to be held in readiness for amphibious attacks on either Saipan or Tinian in the event the Americans were able to establish a beachhead.56 About 0430 on the 18th this group sortied from Tanapag Harbor in thirty-five small boats to put the plan into effect. The Japanese failed. LCI gunboats intercepted the boats and, with the help of Marine artillery, destroyed most of the landing party and turned back the rest.57

This uninterrupted series of reverses sustained by the Japanese on Saipan merely reinforced their determination to hold the island at all costs. On the 17th the chief of the Army General Staff in Tokyo attempted to bolster the spirits of the defenders in a message to 31st Army headquarters: “Because the fate of the Japanese Empire depends on the result of your operation, inspire the spirit of the officers and men and to the very end continue to destroy the enemy gallantly and persistently;

thus alleviate the anxiety of our Emperor.”

To which the Chief of Staff, 31st Army, responded: “Have received your honorable Imperial words and we are grateful for boundless magnanimity of the Imperial favor. By becoming the bulwark of the Pacific with 10,000 deaths we hope to requite the Imperial favor.”58

D Plus 3: 18 June

27th Division

General Holland Smith’s orders for 18 June called for all three divisions under his command to seize the O-3 line within their respective zones of action. For the 4th Marine Division and the 27th Division this meant that the end of the day should see them resting on the eastern coast of Saipan from a point opposite Mount Nafutan up the shore line about 5,000 yards in a northerly direction to a point about one third up Magicienne Bay. From there the objective line for the 4th Marine Division bent back in a northwesterly direction to correspond with the advance of the 2nd Marine Division, which was not intended to cover so much territory. The boundary between the 4th Marine Division and the 27th Infantry Division ran eastward to Magicienne Bay, skirting Aslito field to the north. Army troops were to capture the field itself.59 (See Map II.)

For action on the 18th, the 27th Division had under its command only the 165th Regiment and the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 105th. The 2nd Battalion, 105th Regiment, remained in corps reserve in an area to the rear of the 4th Marine Division, and the 106th Infantry was still at sea. In spite of the fact that as early as 0758 the Marine division had notified General Ralph Smith that control of the 165th Regimental Combat Team was passing to Col. Kelley,60 the regimental commander remained uncertain as to his own exact status. He later reported:

I was unable to determine (by telephone conversation with Hq 4th Marine Div) whether I was still attached to the 4th Marine Division or had passed to the command of CG 27th Div. ... Shortly after this, Major General Ralph Smith visited my CP and advised me that I should receive notice of my release from the Marines and reversion to the 27th Division. I did receive notice from the 27th Division but never received such orders from 4th Marine Division Headquarters.61

This confusion, however, though indicative of poor liaison, was to have no significant effect on the action of the units involved.

Jump-off hour for the two Marine divisions was to be 1000; for the Army division it was 1200.62 The immediate concern of Colonel Kelley, however, was to recapture the ridge southwest of Aslito that his 1st Battalion had given up the previous day. Accordingly, at 0605, he ordered Maj. Dennis D. Claire to move the 3rd Battalion into the line on the right in order to launch a coordinated attack with the 1st Battalion at 0730.63 The 165th Infantry jumped off on schedule after a half-hour naval and artillery preparation along the whole front. The 1st and 3rd Battalions with four tanks preceding them stormed up the ridges while the 2nd Battalion

on the edge of the airfield held its lines until the other units on its right came abreast. A few minutes after 1000 the ridge that had caused so much trouble the preceding day was secured against very light opposition and with negligible casualties to the assaulting units.64

Meanwhile, at 0800, Colonel Kelley authorized his 2nd Battalion to cross Aslito airfield.65 Beginning about 0900, Captain Chasmar, commanding G Company, ordered his men across the airfield along the north side. Capt. Francis P. Leonard, in command of F Company, followed suit shortly after, although he kept his company echeloned to the right rear in order to keep physical contact with E Company, which in turn was in contact with the 1st Battalion. Chasmar reported that he had crossed the airfield at 1000. Sixteen minutes later, Aslito was announced as secured.66 That afternoon when General Ralph Smith arrived at the regimental command post the airfield was officially renamed Conroy Field in honor of Col. Gardiner J. Conroy, former regimental commander of the 165th, who had been killed at Makin.67 Later, it was renamed Iseley (sic) Field in honor of a naval aviator, Comdr. Robert H. Isely, who had been shot down over Saipan.68

Up until 1000 the troops that had overrun the airstrip had met no opposition. Only one Japanese was discovered on the whole installation, and he was found hiding between the double doors of the control tower. All of the Aslito garrison still alive had retired to Nafutan peninsula.69

Upon reaching the eastern end of the airstrip, Captain Chasmar stopped to build up his line because he had been having considerable trouble during the morning trying to cover his frontage. He had tried unsuccessfully to make contact with the marines on the left who were now veering off to the northeast and in his move across the airport had temporarily lost contact on the right with F Company. At the same time, F Company was itself developing large gaps between platoons. By 1100 the whole 2nd Battalion advance was stopped while the battalion commander waited for his companies to close up. For the next two hours the forward line remained stationary along the eastern boundary of the airfield. Unfortunately, the terrain in which G and F Companies had taken up positions was overlooked by the high ground of Nafutan ridge, and the men had hardly begun to dig in when they came under fire from dual-purpose guns located in that sector. The fire lasted for about two hours until friendly artillery was brought to bear on the Japanese positions, which were temporarily silenced.70

With the airfield secure in the hands of the 2nd Battalion, 165th Regiment, and the ridge west and southwest of it occupied by the 1st and 3rd Battalions, General Ralph Smith rearranged his units to launch the main attack at noon as ordered. Into his right flank he ordered the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 105th Regimental Combat Team, which had landed the day before and so far had seen no action on Saipan. On the extreme right the 3rd Battalion,

Aslito Field becomes Conroy Field. General Ralph Smith (left) congratulating Col. Gerard W. Kelley at ceremonies renaming the airfield following its capture. Brig. Gen. Ogden Ross, at right, looks on

105th, completed the relief of the 3rd Battalion, 165th, at 1245, three quarters of an hour late.71 The 3rd Battalion, 165th, then went into reserve. About the same time, the 1st Battalion, 105th, relieved the 1st Battalion, 165th. The latter was then shifted to the left flank of the division line to close the gap between the 4th Marine Division and the 2nd Battalion, 165th, which was occupying the airfield.72 From right to left, then, the new division line consisted of Companies L, I, C, and A, 105th Infantry, and Companies F, G, B, and C, 165th Infantry, with the remaining infantry companies in reserve in their respective battalion zones.

As the afternoon wore on it developed that, as on the previous day, progress on the extreme right of the division front was the slowest, and again the chief obstacle was terrain. In the area inland from the southern coast the ground was a series of jagged coral pinnacles that jutted up from the water’s edge to a height of about 90 feet. Between these peaks were a heavy undergrowth of vines, densely planted small trees, and high grass. Against these odds, but luckily not against the added encumbrance

of Japanese opposition, Company L on the extreme right advanced a mere 200 yards from the line of departure by nightfall, and I Company’s progress was only a little better.73 The situation on the left of the 105th Regimental line was somewhat more promising. In spite of artillery fire from Nafutan Point, Lt. Col. William J. O’Brien, 1st Battalion commander, succeeded by 1400 in pushing forward to a line running southwest from the southeast corner of the airfield.74

While the 105th Regiment was having more than a little difficulty getting started on the division right flank, the 165th on the left was faring better. By 1700 the entire regimental line had almost reached Magicienne Bay, having met only light opposition. The original intention had been to proceed on to the water’s edge, but the heavy undergrowth and coral outcroppings persuaded the regimental commander to pull back to the high ground west of the shore line for the night. About 1700 the commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, 25th Marines, who was on the right flank of the 4th Marine Division line, reported the imminence of a Japanese counterattack between the 24th and 25th Marines. In view of the necessity of the latter’s pulling north to pour in reinforcements against this threat, the lines of the 165th were shifted left about 600 yards to establish contact with the marines for the night.75

4th Marine Division

North of the 27th Division zone, the 4th Marine Division attacked toward the east coast with three regiments abreast: the 25th Marines on the right, 24th Marines in the center, and 23rd Marines on the left.76 The right half of the objective line for this day’s action was to be on the coast of Magicienne Bay, and from there it bent back to the northwest to meet the more slowly progressing 2nd Marine Division.

The 25th Marines jumped off on schedule at 1000. Opposition was light, and by 1330 the regiment had reached the beaches on Magicienne Bay well in advance of the 165th Infantry on its right. The occupation of these beaches on the east coast completed the initial drive of the division across Saipan. The island now, at this point at least, was cut in two. One battalion of the 25th Regiment was left behind to mop up the southern extremity of a heavily defended cliff line that had been bypassed by the 24th Marines on its left.

The latter regiment had had a little difficulty organizing its lines before the jump-off and consequently was delayed forty-five minutes in the attack. Nevertheless, in the face of “moderate to heavy” machine gun and rifle fire, it had succeeded by 1400 in pushing forward to a point only 300 yards west of Magicienne Bay. Then, about 1615, two Japanese tanks suddenly appeared in the zone of the 2nd Battalion, causing considerable anxiety and about fifteen American casualties before they were chased away by bazookas and artillery. By nightfall the elements of the 24th on the right had reached the O-3 line, part of which rested on the coast, and the unit was well tied in with the regiments on its right and left.

Examining an enemy gun. This Japanese Type 10 120-mm. gun was one of several captured when Aslito airfield was overrun

As was the case of the 165th Infantry, the 23rd Marines on the extreme left of the 4th Division line had to capture its line of departure before the scheduled jump-off hour. At 0730 the 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines (attached to the 23rd), passed through the 1st Battalion, 23rd, with orders to seize the line of departure before the main attack, which was scheduled for 0900. The battalion never made it – not that day at least. Intense mortar and enfilade machine gun fire from the left flank stopped the men after an advance of about 200 yards. On the right the 2nd Battalion, 23rd, made about the same gain before it too was pinned down. At 1300 the attack was resumed and after fierce fighting against stubborn Japanese resistance the troops advanced about 300 yards. By 1715 the regiment had established a line some 400 yards east of Lake Susupe. Progress on the left flank of the 4th Marine Division had been far less than anticipated. It was becoming apparent that the main line of Japanese resistance would be in the area north and east of Lake Susupe and not in the southern sector of the island.

2nd Marine Division

The left flank of the corps line remained almost stationary during the 18th. As the

2nd Marine Division’s commander explained it, “At this stage, the frontage occupied by the Division was such that its lines could not be further lengthened without dangerously thinning and overextending them.”77 The strong pocket of resistance encountered by the 4th Division near the division boundary line formed a hostile salient into the beachhead and forced both divisions to maintain abnormally long lines in the sector. The inability of the 4th Division to make substantial progress on its left flank in turn prevented the 2nd Division from risking further extension of its own lines.

Only the 8th Marines saw significant fighting on the 18th. The enemy-infested coconut grove on the regiment’s right that had proved so bothersome the previous day was assaulted and captured. Here, a large number of Japanese dead were found. Before the 18th the enemy had systematically removed its dead before the advance of the attacking forces, but by now, with the American beachhead firmly established and Aslito airfield overrun, Japanese commanders on Saipan had more urgent matters on their minds.78

The Japanese Situation

By the night of 18 June, the Japanese high command in Tokyo as well as its subordinates on Saipan were at last compelled to confess that the situation was critical. The island had been cut in two and the southern part, including the main airfield, was for all practical purposes in American hands. True, remnants of Japanese units, including most of the Aslito garrison, were still holed up on Nafutan peninsula and along the southern shore west of it, but they were cut off from the main body of troops and incapable of anything more serious than harassing attacks against the American lines. (See Map 5.)

In the face of unrelenting pressure from their attackers, the Japanese on the 18th began withdrawing to a defense line extending across the island in a southeasterly direction from a point just below Garapan via the south slopes of Mount Tapotchau to Magicienne Bay. To be more exact, the new “line of security” drawn up by 31st Army headquarters on the night of the 18th was to run from below Garapan east to White Cliff, then south to Hill 230 (meters) and southeast through Hill 286 (meters) to a point on Magicienne Bay about a mile west of the village of Laulau.79

The line roughly paralleled the O-4, or fourth phase line of the American attackers, and was the first of two last-ditch defense lines scratched across the island in a vain attempt to stabilize the battle during the retreat to the north. If the Americans could be brought to a standstill, the Japanese hoped to prolong the battle and eventually win out with the aid of reinforcements.

To Tokyo, 31st Army headquarters radioed its plans:–

Situation evening of 18 June: The Army is consolidating its battle lines and has decided to prepare for a showdown fight. It is concentrating the [ 43rd Division] in the area E of Tapotchau. The remaining units [two infantry battalions of the 135th Inf, about one composite battalion, and one naval unit], are concentrating in the area E of Garapan. This is the beginning of our showdown fight.80

In reply, Imperial General Headquarters ordered Maj. Gen. Keiji Iketa to hold on to the beaches still in his possession, wait for reinforcements over those beaches, and “hinder the establishment of enemy airfields.”81 Iketa reported that he would carry out these orders, that Aslito airfield would be neutralized by infiltration patrols “because our artillery is destroyed,” and that the Banaderu (Marpi Point) airfield would be repaired and defended “to the last.” “We vow,” he concluded, “that we will live up to expectations.”82 Stabilize the battle, keep beaches open for reinforcements, recover and preserve the use of the Marpi Point airfield, and deny to the Americans the use of Aslito – these four objectives were now the cornerstones of Japanese tactics on Saipan.

And from the Emperor himself came words of solemn warning and ominous prescience: “Although the front line officers are fighting splendidly, if Saipan is lost, air raids on Tokyo will take place often, therefore you absolutely must hold Saipan.”83

Five months later American B-29 bombers taking off from Saipan for Tokyo would confirm the Emperor’s worst fears.

Blank page