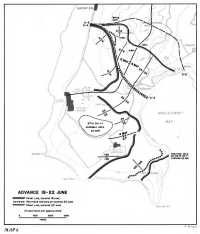

Map 6: Advance, 19-22 June

Chapter 9: The Fight for Central Saipan – I

Preparations for the Drive to the North

While elements of the 27th Division were slowly inching their way down Nafutan Point, the two Marine divisions prepared to launch the drive against the main line of Japanese defenses, which stretched across the waist of the island from just below Garapan to the northwest corner of Magicienne Bay.1 (Map 6.) The 2nd Marine Division in the north had little more to do than consolidate the lines it already held, send out patrols, and mop up small isolated pockets of enemy troops still lurking within its sector. The 4th Marine Division, before it could be in a position to attack, would have to reorient the direction of its drive from east to north and then push forward (northward) about a thousand yards to tie its left flank in with the right flank of the 2nd Division. When this was accomplished the two Marine divisions would be drawn up abreast on what was designated the O-4 line, which ran roughly parallel and a little to the south of the Japanese main line of defense.2

During the period in which the 4th Marine Division was pivoting to the left, the only serious fighting occurred around Hill 500, on 20 June. This 500-foot eminence just west of the village of Tsutsuuran had once been the site of the command post of Colonel Oka, commander of the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade, who had since left it for a safer location to the northward. Hill 500 fell within the zone of the 25th Marines, which attacked it in column of battalions.

Following an advance preparation of rockets, artillery, heavy weapons, and mortars, the lead battalion moved forward about 1030 under cover of smoke. By noon it had seized the hill, and it spent the rest of the day mopping up the network of caves that ran through the area. Altogether, the marines suffered forty-nine casualties and accounted for forty-four enemy dead. The hill had been well organized for defense but not strongly manned.3

That same day the 8th Marines, which constituted the 2nd Marine Division’s right (south) flank, made a forward advance against no opposition to tie in with the left flank of the 4th Division. There was little other activity in the 2nd Division’s zone of action.4 By nightfall of the 20th the marines rested securely on the designated O-4 line ready to jump off on order for the big drive northward. They spent June

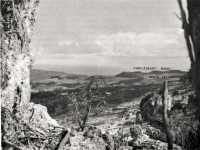

Hill 500. Marines in foreground await signal to advance on the hill

21st resting and sending out patrols. Men of the 4th Division moved as far as 1,500 yards to their front without meeting any organized enemy resistance.5

Landing the 106th Infantry

Before leaving Hawaii, the 106th Infantry Regiment had been assigned as reserve for the 27th Division with the probable mission of landing on Saipan. On arrival at Kwajalein, Col. Russell G. Ayers, the regimental commander, was informed that his unit would be attached to the Southern Landing Force, destined for Guam. The regiment was to land in the rear of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade and to capture Orote Peninsula on that island.6 On 16 June, however, because of the imminent engagement with the approaching Japanese fleet, Admiral Spruance indefinitely postponed the landing on Guam,7 and on the 18th the transports carrying the 106th Infantry were detached from Admiral Conolly’s Southern Attack Force and ordered to Saipan.8 On the evening of the 18th General Holland Smith requested that the 106th be landed “in order to maintain the continuity of the offensive,” but Admiral Turner was reluctant to comply because to do so would inevitably delay the Guam attack until another reserve force for that landing could be brought up from the Hawaiian area. Nevertheless, Smith continued to press his case, and at last Turner concurred

Marines on the crest of hill 500 mop up network of caves

and ordered the 106th Infantry to commence landing early on the morning of 20 June.9

The regiment landed on order and except for its attached artillery was assigned to Northern Troops and Landing Force reserve. Next day Colonel Ayers directed all of his units to initiate reconnaissance in the zones of action of both Marine divisions. In conducting this reconnaissance, one group from the Antitank Company was ambushed and suffered four casualties, the first to occur in the regiment.

The rest of the day the 1st Battalion patrolled Susupe swamp with the mission of clearing Japanese stragglers from the vicinity of corps headquarters and a nearby Marine hospital. For this purpose the battalion was attached to the 2nd Marine Division under whose control it remained until the morning of 23 June. During this period the battalion killed eighteen Japanese in the swamp and took two prisoners of war.10

Japanese Situation on the Eve of the Northern Attack

While the marines pivoted on the 2nd Marine Division’s left flank below Garapan, the Japanese too were pivoting on almost the same point. By the 19th they were in position along a new “line of security” that ran from below Garapan, east to White Cliff, south to Hill 230, and then southeast through Hill 286 to Magicienne Bay.11 General Saito disposed his troops in new sectors divided by Mount Tapotchau. On the extreme right (west) of the Japanese flank the town of Garapan was occupied

Japanese type 93 13.2-mm. machine gun. This dual-purpose gun was captured at Saipan

by naval units, chiefly the Yokosuka 1st Special Naval Landing Force. To their left, the 135th Infantry held the area between Garapan and the west slopes of Mount Tapotchau. The 118th Infantry, a straggler unit, was to hold the area southeast of Tapotchau and be prepared to check enemy landings from Magicienne Bay. Kagman Peninsula was to be held by those remnants of the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade that had not already been destroyed or isolated on Nafutan Point. The 9th Expeditionary Unit, another straggler force, was placed under command of the 47th Independent Mixed Brigade and assigned to defend the shore north of Kagman Peninsula. In general reserve was the 136th Infantry, which had been ordered to assemble at Chacha at sunset on the 19th. The 9th Tank Regiment had a dual mission – to cooperate with the 118th Regiment, and to check any advances along the coast or against the beaches of Magicienne Bay.12

Even this late in the campaign, the Japanese expected either a landing on Magicienne Bay or a tank attack up the bay coast. Their fear of American tanks was especially acute, as a report from 31st Army headquarters attests: “The changes in the battle up until today have been the results of naval gunfire and bombing but from now on the main thing will be to gain unfailing victory in antitank warfare. Our army has new ideas concerning this point and we hope this is not a miscalculation.”13

The stubborn determination of the Japanese to continue their resistance is all the more remarkable in view of their losses to date. As of 19 June approximately three and a half of the 43rd Division’s original eight battalions had been destroyed. Only one of five artillery battalions remained. The 47th Independent Mixed Brigade had been all but eliminated as an organized fighting unit. Two and a half battalions of infantry belonging to other units were destroyed, only one composite battalion remaining. Sixty percent of the 9th Tank Regiment was destroyed, as were most of the 7th and 11th Independent Engineers.14 On the eve of the American attack to the north the personnel losses of Japanese line units were reported to be not lower than 50 percent.15

In terms of artillery and tanks, the Japanese were just as badly off and as

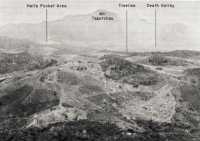

Japanese field of fire from Mt. Tapotchau

hopelessly outnumbered. All that remained to them on 20 June after six days of fighting were eleven 75-mm. field pieces, twenty-seven tanks, three operational antiaircraft guns, and nine machine cannon.16

But though the Japanese on Saipan were weak in manpower and short of weapons and equipment, they lacked nothing of the traditional spirit that had driven and was to drive so many of their countrymen to glorious if futile death on the battlefield. On the eve of the battle one tanker doubtless spoke for most of his compatriots when he inscribed in his diary:

The fierce attacks of the enemy only increase our hostility. Every man is waiting for the assault with all weapons for close quarters fighting in readiness. We are waiting with ‘Molotov cocktails’ and hand grenades ready for the word to rush forward recklessly into the enemy ranks with our swords in hands. The only thing that worries me is what will happen to Japan after we die.17

22 June: The Jump-off

General Holland Smith’s orders for 22 June called for an attack to the north by

the two Marine divisions in line abreast, the 2nd Division on the left, the 4th on the right. The jump-off hour was to be 0600, the objective line (O-5) to run through Laulau village on Kagman Peninsula on the right, Mount Tapotchau in the center, and a point on the west coast of the island about 1,000 yards south of Garapan on the left.18

In view of the fact that this northward push would automatically extend the lines of the two Marine divisions, especially as the 4th Division was required to spread eastward on Kagman Peninsula, the corps commander alerted the 27th Division to the fact that it might soon be committed to the northern line. The Army division, which was then in corps reserve, was ordered to reconnoiter routes to both of the Marine divisions’ zones of action. 27th Division Artillery was passed to the control of General Harper’s XXIV Corps Artillery to deliver close and deep support missions in advance of the marines. Altogether, the troops on the northern line would have eighteen battalions of artillery to support their drive on the morning of 22 June.19

On the right of the 4th Marine Division zone in the area inland from Magicienne Bay, the 24th Marines jumped off on schedule, made rapid progress against light opposition, and by 1330 reached an intermediate objective line that had been established by the division commander about 2,000 yards in front of its line of departure.20

To its left, the 25th Marines found the going more difficult. The regiment jumped off on schedule in column of battalions, and within half an hour the lead battalion was attacked by a force of Japanese troops accompanied by a tank. Ninety of the enemy were killed and the tank was destroyed. For the rest of the morning the regiment encountered light resistance, but just south of the intermediate objective line received severe machine gun fire, a situation that was aggravated by an exploding Japanese ammunition dump. This slowed progress so that by the day’s end the 25th Marines were still short of the day’s objective, although the regiment had made an advance of about 2,000 yards.21

Meanwhile, the 23rd Marines, which had been in division reserve, was committed between the two assault regiments shortly after noon. Fighting against light enemy resistance but over stubborn terrain, the 23rd Regiment, too, fell just short of reaching the day’s objective by the time it dug in for the night.22

The 2nd Marine Division had the more difficult task of gaining the approaches to Mount Tapotchau and of pushing to the top of Mount Tipo Pale. General Watson, the division commander, placed all three of his regiments in line abreast, the 8th, 6th, and 2nd Marines from right to left. As the official Marine Corps historian described the scene, “Looking to the north of the 6th and 8th Marines’ lines, a nightmare of sheer cliffs and precipitous hills could be observed, separated in crisscross fashion by deep gashes. ... Dense foliage which cloaked the region often limited visibility to a few feet.”23

Both assault battalions of the 8th Marines made fair progress against little

opposition during the morning even though their axis of attack was cut by deep ravines, cliffs, and transverse ridges. As they neared the top of the first ridge line, they lost contact, and about noon the reserve battalion had to be committed in the center. An hour later forward movement stopped as mortar fire began to fall heavily all along the line. Enemy machine guns located on a hill to the right in the zone of the 25th Marines commenced to lay enfilade fire along the right flank of the 8th Marines. The summit of Mount Tapotchau still lay about 1,200 yards (as the crow flies) ahead, but no further progress could be made that day, and the regiment dug in for the night.24

In the center the 6th Marines was initially held back by the slow progress of the division’s right flank. Shortly after noon the advance toward Tipo Pale got under way, only to come up against several pockets of Japanese machine guns, which stopped the lead elements on the slopes of the mountain. After a futile attempt to get at these positions by a flanking movement, the marines bypassed them altogether, and by 1400 the lead battalion had pushed to the top of Tipo Pale.25

The advance to the top of Tipo Pale marked the farthest and most significant progress in the zone of the 2nd Marine Division. This eminence was about 1,000 feet in height and lay about 1,200 yards southwest of Tapotchau’s summit.26 Its capture was essential to cover any approach to the western slope of Tapotchau.

No forward movement was made on the extreme left of the 2nd Division’s zone. The 2nd Marine Regimental Combat Team occupied the O-5 line south of Garapan for several days, and since the whole forward maneuver of the two divisions pivoted on this regiment it was forced to remain stationary until the other regiments pulled abreast.27

Meanwhile, preparations were proceeding apace to move the 27th Infantry Division into the main line of attack. On the evening of 21 June General Holland Smith had ordered the division to conduct reconnaissance to the north over the road net that led to the 2nd and 4th Marine Division areas.28 By late afternoon of the 22nd all three battalions of the 165th Infantry had completed the reconnaissance as ordered by Colonel Kelley.29 That evening Colonel Ayers took the commanders of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 106th Infantry, with him on a road reconnaissance and before dark had reached a point where his regiment would leave the road system and move cross country in the direction of the front held by the 4th Marine Division.30 About 1600 that afternoon General Ralph Smith visited the headquarters of General Erskine, chief of staff to General Holland Smith, where he first received definite information that his division would be fed into the Marine front line the following day. The plan was for the Army division to relieve the left flank elements of the 4th Marine Division so as to permit that

unit to move eastward to cover Kagman Peninsula. This would put the 27th Division in the center of a three division front and at the entrance to the valley that lay between Mount Tapotchau and its hill system on the left (west) and a series of hills and ridges on the right (east) that ran north from Magicienne Bay.31 Jump-off hour for the next morning was set at 1000.

As soon as this decision was reached, General Ralph Smith called Brig. Gen. Redmond F. Kernan, Jr., and ordered the division artillery to begin reconnaissance for positions from which to support the division attack next morning. Smith then left for his own command post where he met with Colonels Kelley and Ayers, commanders of the two regiments that would go into action next day. General Smith assigned Ayers’ 106th Infantry to the left of the division line and Kelley’s 165th to the right. Zones of approach to the line of departure were assigned to each of the regimental commanders, who in turn were to work out their routes of approach within their zones.

Ayers and Kelley returned to their own command posts shortly after 1800 and began briefing their battalion commanders.32 In the 106th Regiment the 3rd Battalion, under Lt. Col. Harold I. Mizony, was designated the assault battalion. It was to be followed in column by the 2nd, under Maj. Almerin C. O’Hara, and the 1st, under Lt. Col. Winslow Cornett.33 Colonel Kelley designated his 2nd Battalion, under Lt. Col. John F. McDonough, as the lead battalion during the approach. The 2nd was to be followed by the 1st, under Major Mahoney, and the 3rd, under Major Claire. Upon relieving the marines, the 165th was to take up the line with its 2nd Battalion on the left and its 1st on the right.34

Orders from division headquarters confirming these decisions were issued at 2100.35 The line of departure for the two Army regiments was to be the “line held by the 4th Marine Division within the [27th] Division zone of action.” Two and a half hours later General Holland Smith’s headquarters issued substantially the same order.36 In this case, the line of departure was designated as the “front lines at King Hour [1000],” which was essentially no different from that specified by Ralph Smith.

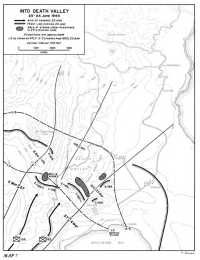

23 June: Into Death Valley

Promptly at 0530, just as day was breaking, both regiments began to move toward the front lines.37 (Map 7.) In the 106th Infantry zone Colonel Mizony’s 3rd Battalion led off with Company L in the lead, followed by K, then battalion headquarters, and finally I Company.38 Colonel McDonough’s 2nd Battalion, 165th, took the lead in that regiment. About 0620 the head of McDonough’s column cut into Mizony’s column just behind L Company, thus splitting the 3rd Battalion, 106th Infantry,

Map 7: into Death Valley, 23-24 June 1944

at that point.39 The two regimental commanders conferred but nothing could be done to unscramble the units until they reached a clearing that would permit the 165th to move eastward and the 106th to proceed north toward its assigned zone of action. At this point of divergence an officer control station was set up to sort out the vehicles and units of the two regiments and direct each to its proper destination. Altogether, this delayed Companies K and I, 106th Infantry, upwards of an hour, though Company K was due to move into the assault at the line of departure at 1000. Company L, 106th, on the other hand, was ahead of the traffic jam and was able to push on unhindered.40

The two assault battalions of the 165th Infantry relieved the 24th Marines at 1000 on schedule.41 Company L, 106th Infantry, completed the relief in its zone at 0930. Only Company K of the 106th was late, but its tardiness was to hold up the entire division attack. Not until 1055, or almost an hour after the scheduled jump-off time, was Company K in line, and not until then could the 3rd Battalion jump off in the attack.42

When the men of the 106th Infantry got into the line, they were surprised to discover that some of the marines whom they were to relieve had fallen back two or three hundred yards from positions held the day before.43 Company K of the 25th Marines had pulled back to its right rear on the previous evening to tie in the night defense.44 This caused some consternation at 106th headquarters because the regimental commander was under the mistaken impression that the line of departure for the morning’s attack was the forward line of the previous day’s advance as indicated on his overlay, rather than the “front lines at King Hour” as stated in the operation order. Actually, of course, this withdrawal on the part of the Marine company eased Colonel Ayers’ immediate problem by reducing the distance his already tardy troops would have to cover before reaching the line of departure. It did, however, create a gap between the 106th and the 165th on his right that would have to be covered before the two units could move forward abreast.

The positions the 27th Division was ordered to assault had, since 19 June, been held by the 118th Infantry Regiment, which as of that date was made responsible for the entire Japanese line of defense from the east slope of Mount Tapotchau to Magicienne Bay.45 The Japanese regiment had been torpedoed en route from Japan to Saipan less than three weeks earlier and had arrived on the island minus about 850 of its troops and almost completely stripped of its weapons and equipment.46 Total troop strength of the regiment on its arrival on Saipan was estimated to be about 2,600.47 The Japanese command had had neither time nor opportunity to re-equip the survivors and reorganize them into a first-class fighting unit. The degree of attrition suffered by the regiment since

the American invasion is unknown but it cannot have escaped damage from the terrible pounding from air, sea, and land to which the island had been subjected since 12 June.

Before the 27th Division was committed, the 136th Infantry Regiment, 43rd Division, which had previously been in reserve around Chacha village was ordered to move out to Hill 286 (meters), Hill 343 (meters), “and the hills E[ast] of there.”48 Hill 286 was in the zone of action of the 2nd Marine Division, but Hill 343, the “hills East,” and the valley in between were directly athwart the line of advance of the 27th Infantry Division.

Initially, the 136th had been one of the Saipan garrison’s best fighting forces, being at full strength and fully equipped at the time of the landing. However, the regiment had taken a frightful beating in the first days of the invasion. Manning the Central Sector facing RED and GREEN Beaches, it had borne the brunt of some of the hardest fighting on Saipan. Although not literally decimated, its combat strength had been severely weakened. Two men of the regiment who had been captured on 25 June testified that its 2nd Battalion had been depleted approximately 67 percent on the first day of the landing, that the remnants of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were combined as a single battalion, and that the total strength of the regiment was less than 1,000.49

But whatever losses in manpower and equipment the Japanese in this sector may have suffered, they still had one enormous advantage. That was terrain.

The soldiers of the 27th Division were soon to dub the area “Death Valley.”50 The “valley” is really a terracelike depression on the eastern slope of the sprawling mountain mass that fills most of central Saipan and culminates in the towering peak of Mount Tapotchau. The floor of the valley, less than 1,000 yards in width, is dominated along its entire length by the rugged slopes of Mount Tapotchau on the west and a series of hills, the highest about 150 feet above the valley floor, on the east. This eastern hill system was to be called “Purple Heart Ridge” by the soldiers who fought there. Death Valley, then, was a sort of trough into which the men of the 27th Division were to advance. The valley itself was almost devoid of cover except for a line of trees near the southern end and for three or four small groups of farm buildings surrounded by trees. The cliff on the left was for the most part bare, but above the cliff was wooded ground. The hills on the right were tree-covered. A narrow road – little more than a cowpath – ran up the valley a short distance then branched off, the left branch skirting the cliffs of Mount Tapotchau, the right heading toward the north face of Hill Able and then cutting to the east.

Obviously, this terrain was ideally suited for defense against any attack through the valley, and the Japanese made the most of

Mt. Tapotchau dominating Death Valley, where 27th Division troops fought from 28 through 30 June

it. In the words of Col. Albert K. Stebbins, Jr., 27th Division chief of staff:

The cliffs and hillsides were pocketed with small caves and large caves. The wooded area was rough, filled with boulders, and excellent for defensive operations. Bands of fire were laid by the enemy thru the underbrush and in such manner as to make it most difficult to discover their locations: Well-placed, hostile guns fired only when lines passed and striking our forces in the rear disrupted the attack.51

The Japanese had at their disposal all kinds of automatic weapons, light and heavy mortars, and some 75-mm. mountain guns. These were well concealed, usually in caves whose mouths were covered with brush. Troops approaching through the valley could get at the positions only by direct shots from tanks or self-propelled guns. It was impossible to reach them with artillery, at least during the initial stages of the attack, because the axis of the caves was at right angles to the line of fire of the artillery.

“Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them.” Not so much cannon perhaps, but enough other fire to make this seem to the men caught in the middle a true replica of Tennyson’s “Valley of Death.”

Tree line in Death Valley, where elements of the 2nd Battalion, 165th, were pinned down on 23 June

The units of the 27th Division lined up from right to left (east to west) as follows:

165-C: 1st Lt. Edward L. Cloyd, Jr.

165-A: Capt. Laurence J. O’Brien

165-G: Capt. Paul J. Chasmar

165-F: Capt. Francis P. Leonard

106-K: Capt. William T. Heminway

106-L: Capt. Charles N. Hallden

The regimental boundary line coincided with the road that ran through Death Valley.

On the division right the first obstacle to be overcome by the 1st Battalion, 165th, was Hill Love, lying roughly on the border line between Companies A and C. This eminence rose about 700 feet above sea level, was tree-covered, and was infested with Japanese. A patrol from A Company met heavy machine gun and rifle fire that killed the patrol leader and wounded one other man. It was then decided that the two companies would circle the hill and meet at its northern base. Company C on the right jumped off at 1015 and by 1400 had succeeded in working its way around the hill to the northern face. Here, the men were pinned down by heavy fire to their front and made no further advance. During the course of the afternoon the company suffered three men killed and fourteen wounded. A platoon of tanks from the 762nd Provisional Tank Battalion was brought forward in an effort to reduce the

Driven to concealment by the intensity of enemy fire in Death Valley on 23 June, 27th Division soldiers worked their way into a small wooded area

enemy positions. One of these, commanded by 1st Lt. Louis W. Fleck, was set on fire with a “Molotov Cocktail.” All the tankers but one were killed as they emerged from the turret.52 The men of Company C who witnessed the incident were helpless to avert it because by now marines had pushed ahead directly into their line of fire and the battalion commander had ordered them not to fire.

Meanwhile, Company A had also reached the northern face of Hill Love. It too could make no further progress. At 1630 the tanks withdrew for the night and the two companies dug in. Company B was brought in and completed the encirclement of the promontory by digging in on the south face.53

The 2nd Battalion, 165th Infantry, also had considerable trouble during the afternoon. After reaching the tree line that lay about 300 yards to their front, both of McDonough’s companies remained stationary for two hours, waiting for Company K, 106th Infantry, to work its way up on the left. General Ralph Smith finally ordered McDonough to advance without regard to

what was going on in the 106th area and instructed Colonel Kelley to commit his reserve if necessary.54 Regiment therefore ordered an attack for 1315.55 Company E was brought up and ordered to deploy one platoon on the regimental left to maintain contact with K Company of the 106th and the other on the right to maintain contact with the 1st Battalion, 165th.56

As soon as McDonough’s battalion moved out from the line of trees it was greeted by a hail of small arms, machine gun, and heavy weapons fire from the cliff line on its left. A similar concentration of fire from Purple Heart Ridge on the right soon followed and the advance platoons of Company F were badly hit in the cross fire. Under cover of a smoke screen laid down by the chemical battalion, the men eventually pulled back to the tree line from which they had started. Company G, witnessing the results of F Company’s advance also withdrew to the tree line and remained there for the rest of the day.57

In the zone of the 106th Infantry on the division left the action can be characterized as two separate battles since K and L Companies had no physical contact during most of the day. Company K on the right pushed off at 1055. Shortly thereafter the leading scout of the advance platoon was struck by machine gun fire. The rest of the company hit the ground and was immediately subjected to mortar fire. The company commander, Captain Heminway, ordered his men to move forward by infiltration. This movement began about 1300, and by 1500 the company had worked its way into a small wooded area that provided some cover against the enemy weapons. There it waited for L Company on its left to come up, and since the latter unit did not pull abreast until 1615 both decided to dig in there for the night.58

Company L had arrived on the line in sufficient time to push the attack at 1000 but had been held up by K Company’s tardiness in relieving the marines in its zone. On Captain Hallden’s left was the cliff of Mount Tapotchau and on his right a series of ravines. About 400 yards ahead, the cliff line receded to form a little cove in the mountain wall that the soldiers F dubbed “Hell’s Pocket.” In the midst of this cove was a lone rock that rose a hundred feet and was covered with ivy. Caves in the rock and in the cliff walls that surrounded it provided ideal spots for Japanese machine guns.59

Company L advanced about fifty yards from its line of departure, and Japanese mortar fire began to fall in the area. Hallden pushed his men on, moving along the base of the cliff, which formed the west wall of Hell’s Pocket. As the troops probed deeper into the pocket an enemy mortar shell set off a Japanese ammunition dump and the flying debris kept the men pinned down for over an hour. Self-propelled mounts were brought forward in an effort to knock out the cave positions of the Japanese but the vehicles were too exposed to fire from above to accomplish much. Finally, a platoon of medium tanks came in to support the infantry.60

By this time the gap between K and L Companies had grown wider so Hallden

shifted to the right rear out of Hell’s Pocket and by 1530 had re-established contact with Company K on the valley floor where both companies dug in for the night. Company I, which had been in reserve most of the afternoon, was brought up and dug in on the rear of this position.61 Progress for the day in the zone of the 106th was about 100 yards.

Throughout the day the 106th Regiment experienced considerable difficulty in maintaining contact with the 2nd Marine Division on its left. The corps order had stipulated that the burden of contact was from right to left.62 Responsibility for contact therefore rested with L Company, 106th, but the marines were moving along the top of the cliff at whose base the Army troops were located, and physical contact was impossible. As Company L moved to the right to tie in with Company K, even visual contact was lost. At 1703 division headquarters ordered Colonel Ayers to gain contact with the marines on his left “with sufficient force to maintain it,”63 and half an hour later Ayers ordered the 2nd Battalion, 106th, to cover the gap.64 On the theory that it would be easier to maintain contact between two companies of the Army division than between Marine and Army units, Company F was ordered to move to the top of the cliff and tie in with the marines while G Company moved forward to positions below the cliff and established contact on the left of L Company. This move was not completed until 1910, and both companies had to build up a defensive line under cover of darkness.65 Later that night, Company F’s 1st Platoon, which was hugging the cliff overlooking the edge of Hell’s Pocket, was attacked by a party of about fifteen Japanese who made their way through the perimeter before being discovered. In the intense hand-to-hand fight that ensued, bayonets, grenades, knives, and fists came into play. The Japanese killed two men of the platoon and wounded two others before being destroyed or routed.66

Progress in the zone of the 27th Division on 23 June had been disappointing, especially in the area assigned to the 106th Infantry. During the afternoon General Holland Smith expressed his alarm over the situation in a conversation with General Jarman, the island commander and the senior Army officer on Saipan. In General Jarman’s words:–

General Smith, CG of the V Phib Corps, called me to his quarters and indicated that he was very much concerned about the situation which he was presented with in regard to the 27th Div. He outlined to me the many things that had happened with respect to the failure of the 27th Div to advance. He indicated that this division had suffered scarcely no [sic] casualties and in his opinion he didn’t think they would fight. ... He stated that if it was not an Army division and there would be a great cry set up more or less of a political nature, he would immediately relieve the division commander and assign someone else.67

Next morning, General Holland Smith registered his displeasure in a stern dispatch to General Ralph Smith himself:–

COMMANDING GENERAL IS HIGHLY DISPLEASED WITH THE FAILURE OF THE 27th DIVISION ON JUNE TWENTY THIRD TO LAUNCH ITS ATTACK AS ORDERED AT KING HOUR AND THE LACK OF OFFENSIVE ACTION DISPLAYED BY THE DIVISION IN ITS FAILURE TO ADVANCE

AND SEIZE OBJECTIVE O-5 WHEN OPPOSED ONLY BY SMALL ARMS AND MORTAR FIRE X THE FAILURE OF THE 27th TO ADVANCE IN ITS ZONE OF ACTION RESULTED IN THE HALTING OF ATTACKS BY THE 4th AND 2nd MARINE DIVISIONS ON THE FLANKS OF THE 27th IN ORDER TO PREVENT DANGEROUS EXPOSURE OF THEIR INTERIOR FLANKS X IT IS DIRECTED THAT IMMEDIATE STEPS BE TAKEN TO CAUSE THE 27th DIVISION TO ADVANCE AND SEIZE OBJECTIVES AS ORDERED X.68

There can be no doubt of the truth of General Holland Smith’s charges that the 27th Division had been late in the jumpoff, that its advance had been slow, and that it had held up progress of the two Marine divisions on its flanks. It is apparent, however, that he underestimated the stubbornness of the Japanese defenses in the area by dismissing the opposition in the zone of the 27th Division as being “only by small arms and mortar fire.”

When subsequently queried on this point, Colonel Ayers, commanding officer of the 106th Infantry, was of the firm belief that if he had tried to advance rapidly across the open ground in front of him his regiment “would have disappeared.”69 General Ralph Smith agreed. He later testified that, after visiting the front lines shortly after noon, he was “satisfied that Col. Ayers was making every effort possible to advance in the valley, and considered that any further pushing of troops in that zone would only lead to increased casualties, without accomplishing adequate results.”70

On the other hand, General Jarman testified that in his conversations with General Ralph Smith on the afternoon of 23 June the division commander had been far from satisfied with the conduct of his troops. In General Jarman’s words:–

I talked to General Smith and explained the situation as I saw it and that I felt from reports from the Corps Commander that his division was not carrying its full share. He immediately replied that such was true; that he was in no way satisfied with what his regimental commanders had done during the day and that he had been with them and had pointed out to them the situation. He further indicated to me that he was going to be present tomorrow, 24 June with his division when it made its jump-off and he would personally see to it that the division went forward. ... He appreciated the situation and thanked me for coming to see him and stated that if he didn’t take his division forward tomorrow he should be relieved.71

The First Night in Death Valley

At 1925, just as darkness fell, the Japanese launched a six-tank attack down the road that ran the length of Death Valley and marked the boundary between Mizony’s and McDonough’s positions.72 Not until the column had almost reached the American outposts was it discovered, and by then the lead tank was too close to be fired upon from either side of the road without endangering the men on the other. The other five tanks, however, were taken under fire by both battalions with every weapon available. Bazookas, antitank guns, grenade launchers, and artillery went into action, and all five tanks were knocked out. The lead tank proceeded on through the lines and circled back, firing constantly. One shell landed in a Japanese ammunition dump located in the midst of the 3rd

Marines emerging from Purple Heart Ridge complex

Battalion, 106th’s, lines and set it afire. The tank then turned east and was finally knocked out in the zone of the 23rd Marines.73

Meanwhile, the ammunition dump in the middle of the 3rd Battalion, 106th, was going off in all directions. Simultaneously, the Japanese on Mount Tapotchau began to throw mortar shells and machine gun fire into the area. Company L suffered sixteen men wounded within the space of an hour. The position of the entire 3rd Battalion was now untenable. 1st Lt. George T. Johnson of I Company ordered his men to disperse as soon as the dump started to explode. He later assembled them across the road to the rear of the 165th line and dug in there for the rest of the night. The other two infantry companies withdrew about 100 yards behind the conflagration, thus canceling altogether the small gain made by the battalion during the day’s action.74

23 June: Marines on the Flanks

On the right of the 27th Division, the 4th Marine Division attacked with two regiments abreast, 24th on the right and 23rd on the left. The 24th Marines pushed

rapidly ahead along the shore of Magicienne Bay and by midafternoon had reached the O-5 line at one point just east of the village of Laulau.75 On the left the 23rd Marines made somewhat slower progress, partly because its advance was held back by the 165th Infantry. Within a short time after the jump-off, one battalion seized the top of Hill 600, which though lightly manned by the enemy was admirably suited for defense and took thirty minutes of close fighting to capture. There, the battalion was ordered to hold, pending the advance of the Army troops on the left, but since the 1st Battalion, 165th, was held up, the marines spent the rest of the afternoon in a stationary position, firing and pitching grenades at the Japanese who still occupied in force the northern face of the hill.76 That night a group of enemy tanks launched an attack against Hill 600 but was repulsed with the loss of three of its five vehicles.77

On the other side of Death Valley, the 8th Marines jumped off on schedule except on the right flank, which was held up by the late arrival of the 106th Infantry. To fill the gap between these units, the reserve battalion was ordered into position to protect the right flank and the three battalions in the assault moved forward. By midafternoon the right battalion seized the cliff that dominated the only feasible route to the top of Mount Tapotchau. On the regimental left, the marines ran into a nest of about thirty Japanese riflemen and six heavy machine guns, which held up their progress for the rest of the day.

Soon after the 6th Marines in the center of the 2nd Division’s line launched its attack, the right flank battalion was pinched out by the reduced frontage. On the left, the regiment made no advance during the day because it was already so far forward that any further move would have caused too much of a contact strain. The same was true of the 2nd Marines on the division left flank. Not until the center of the corps line made more significant progress would it be safe for the elements on the left to move ahead.78

24 June: Action of the 27th Division

General Holland Smith’s order for June 24th called for a continuation of the attack with three divisions abreast in the same order as before, commencing at 0800. Corps artillery was assigned to general support and ordered to reinforce the fires of divisional artillery.79 In the zone of the 27th Division, its own organic artillery would fire a ten-minute preparation before the jump-off and thereafter support the attack on call.80

165th Infantry Attack Against Purple Heart Ridge

At 0705 corps reminded 27th Division that the slope on the right side of Purple Heart Ridge was in the zone of action of the 165th Infantry, which would capture it with the help of fire from the 4th Marine Division on its right.81 This meant in effect that the 106th Infantry alone would

be responsible for the frontal attack up Death Valley. Simultaneously, the 2nd Battalion, 165th, would attack along the crest of Purple Heart Ridge itself and the 1st Battalion, 165th, would move up on the right (east) of the ridge.

Purple Heart Ridge was in reality a series of hills connected by a ridge line running in a northerly direction. From south to north these hills were designated Queen, Love, George-How, Xray-Yoke, Oboe, King, and Able.82 Hill Queen had already been overrun by the 4th Marine Division in its advance eastward toward Kagman Peninsula. Hill Love had been surrounded by the 1st Battalion, 165th Infantry, which had dug in the night before around its base.83

There were obvious tactical advantages to an early capture of this ridge line or any considerable part of it. It overlooked Death Valley from the east just as the higher cliffs around Mount Tapotchau did from the west. The commanders were becoming aware that any movement north through the valley could be easily interdicted by fire from the elevations on either side. If the lower of the two walls of the corridor – Purple Heart Ridge – could be seized, then fire could be brought directly to bear against the caves that dotted the west cliffs from which such effective fire was being trained on the troops trying to advance through the valley below.

At 0800 the two assault battalions of the 165th Infantry jumped off on schedule84 in the same order they were in at the end of the previous day’s fighting: On the front line from right to left were Cloyd’s Company C, O’Brien’s Company A, Chasmar’s Company G, and Leonard’s Company F. In reserve for the 1st Battalion was Gil’s B Company; for the 2nd Battalion, Ryan’s E Company. The regimental plan called for Company C on the right flank to swing well to the right and then northeast into the zone of the 23rd Marines. There it would wait until the rest of the battalion came abreast. Company B was to come up from behind Hill Love on A Company’s left, execute a turning movement, and then attack eastward across A’s front in order to enfilade the enemy positions to the north of Hill Love.85

Within a little more than an hour after the jump-off, Company C had moved to the right and gained physical contact with the marines.86 Lieutenant Cloyd stopped his advance on the northern nose of Hill 600 to await the approach of the rest of the battalion on his left. He made no further progress that day.87

On the battalion left, Companies A and B ran into immediate trouble. As A pushed off from Hill Love toward the same positions that had caused so much trouble the day before, it came under heavy fire from small arms and machine guns. Company B then moved up to the left and, as planned,

tried to execute a turning movement to the right across A Company’s front. Company B, too, met a fusillade of fire and finally withdrew after losing twelve wounded, two mortally. It was only 0930, but the 1st Battalion attempted no further movement until midafternoon.

Colonel Kelley then decided to commit his 3rd Battalion to the right of the line. The 3rd was to move to the right, following the same route used by Company C and, upon reaching the latter’s positions on the left flank of the Marine lines, pass through and launch an attack that would carry it to the top of Hill King, almost at the northern edge of Purple Heart Ridge. While this was taking place, B Company was to circle the pocket of resistance north of Hill Love and build up a line facing the pocket from the north. Thereafter, the 1st Battalion was to mop up this area of resistance and retire into regimental reserve. The change of plans was agreed upon at 0904, and orders were accordingly issued at 1015.88 The 3rd Battalion completed its move by 1335, and by that time Company B had encircled the pocket and was facing south ready to attack.

Meanwhile, the 2nd Battalion, 165th Infantry, moved off on schedule in an effort to take the ridge by a direct assault from the southwest. The night before, the battalion had occupied positions about three hundred yards to the north and west of Hill Love. G Company moved off with Company F following, echeloned to the left rear. By 1000 the lead platoon had reached the southern face of Hill Xray-Yoke, about the midpoint of the ridge. Here the men found a steep gulch directly across the path of advance. In order to get up on the hill itself, they would have to climb down the near cliff, cross the bottom of the canyon, and scale the cliff on the other side. As the first platoon attempted this feat of acrobatics it came under rifle fire from the hill ahead and was stopped in its tracks. Company G made no further progress that day.

F Company to the left rear had also run into trouble. As it came abreast of G, Company F spread out to the left where the gully in front of Hill Xray-Yoke was not quite so precipitous. Here the terrain was friendlier, but the enemy was not, and heavy mortar and machine gun fire kept the bulk of the company pinned down for two hours. Around 1130 Captain Leonard sent a patrol out to his left toward a small house located on the floor of Death Valley. His purpose was to protect his flank from a possible attack from that direction. Of the twenty men dispatched on this mission six were wounded and one was killed by machine gun fire before the patrol was withdrawn. F Company, too, now held its lines for the remainder of the day. At nightfall the whole battalion dug in just below the gulch. The day’s action represented an advance of about 150 yards.

While the stalemate was developing on the left flank of the regimental line, stubborn resistance continued on the extreme right. The 3rd Battalion had swung right behind the ridge and passed through Company C at 1335.89 Shortly after 1600 Capt. Howard Betts, who commanded Company K, made a frontal assault in column of platoons up Hill Xray-Yoke from the east. The lead platoon reached the tree line well up the hill without much trouble, but just

as it started into the undergrowth, Japanese machine guns opened fire from the left front, traversing the length of Betts’ line and wounding two men. The platoon took to earth and was pinned there by a continuous grazing fire for almost two hours. Betts immediately swung his second platoon into line on the right, but after about fifty yards further advance up the hill, it too ran into machine gun fire and was stopped. By this time darkness was coming on, and Company K was pulled down the hill to tie in with I Company for the night. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion’s effort to mop up the pocket of resistance north of Hill Love had failed, and that unit, with the exception of Company C, dug in around the same positions it had occupied the night before.

106th Infantry: Into Death Valley Again

The units, from right to left, on the front line facing the mouth of Death Valley on the morning of 24 June were: Company K, 106th Infantry, Captain Heminway; Company L, 106th Infantry, Captain Hallden; and Company G, 106th Infantry, Capt. David B. Tarrant. Company F of the 106th was still on top of the cliff, and, since its movement was geared to that of the 2nd Marine Division, its actions must be considered as separate from those of the rest of the 106th Regiment.

The 3rd Battalion jumped off on time, but immediately encountered such heavy mortar fire that many of the men fell back to the line of departure and in some cases behind it.90 By 0945 the front-line troops had advanced from 50 to 100 yards into the valley, but there was no sign of any abatement of enemy fire, especially from the cliffs of Tapotchau. Division headquarters was severely disappointed, and at 1012 General Ralph Smith radioed Colonel Ayers: “Advance of 50 yards in 1 1/2 hours is most unsatisfactory. Start moving at once.”91

In response to this pressure, Company K, supported by a platoon of medium tanks of Company B, 762nd Tank Battalion, immediately pushed forward into the valley. Captain Heminway had two platoons abreast, the 1st on the right, the 3rd on the left. He left the 2nd Platoon at the entrance to the valley to deliver covering fire to his front. He also set up his machine guns on the high ground beside the valley road and had some support from M Company’s heavy weapons. Heminway’s men advanced in a long, thin skirmish line, moving rapidly toward the center of the valley. They had pushed forward fifty yards without event when the entire cliff on the left of the valley seemed to open up. The company broke into a run toward a fold in the ground that offered some cover. Here the company commander stopped to reorganize his line. Just as he got up to wave his men forward again he was shot in the head and killed. This paralyzed the entire line until 1st Lt. Jefferson Noakes, the company executive officer, could come forward and take command.92

Meanwhile, the platoon of tanks attached to Company K had been roaming around the floor of the valley trying to silence the Japanese fire from the cliff. One of the tanks, commanded by the platoon leader, 2nd Lt. Richard Hitchner, received

Tank-infantry cooperation. Medium tank leading men of Company K, 106th Infantry, into Death Valley on 24 June

two hits from enemy shells, was knocked out, and had to be abandoned.93 Around 1100 another tank was hit, and the whole platoon withdrew.

At this juncture 3rd Battalion called the company headquarters and announced that a smoke screen would be laid down and that under its cover the men of Company K were to withdraw from their exposed positions. Some of the men did withdraw under the smoke, but one platoon failed to get the word and remained holed up until two tanks that had been supporting L Company went over and covered its withdrawal.94

Meanwhile, Company I, under Lieutenant Johnson, had been ordered into the line between the other two companies of the 3rd Battalion. Reporting at 1015,95 Johnson was told to move two platoons out into the valley in column, swing left until he made contact with L Company’s right flank, and then deploy his men to the right to close the gap that existed between Companies L and K. Immediately upon entering the pass into the valley, both platoons were subjected to brutal fire from the cliffs on the left and stayed pinned down for better than two hours. The men lay on an open slope without any means of protection, unable even to lift their heads to fire back. Seven were killed and thirteen wounded. A little before 1200, as the men still lay out on the open ground, three Japanese tanks came down the valley road from the north firing in all directions. Just as they were about to overrun the area

occupied by Company I, all three were knocked out by antitank guns from both sides of the valley.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Johnson was frantically trying to get at the source of the enemy fire that was proving so deadly to his unit. He had the antitank guns of battalion headquarters open up on the face of the western cliff with canister and set up all of M Company’s heavy machine guns to deliver covering fire in that direction. His 3rd Platoon, which was just at the entrance to the valley, took up positions and delivered supporting small arms fire all along the face of Mount Tapotchau. Johnson himself took his company headquarters and moved along the edge of the trees to the left in an effort to get at the Japanese position in front of Company L. As this group moved to the left through the undergrowth, it too was pinned down by mortar fire and discovered the woods to be full of enemy riflemen between the valley road and L Company’s right flank. Johnson was wounded.

It was at this point that the battalion commander ordered K and I Companies to withdraw under cover of smoke. In the latter unit’s zone, the screen was neither effective nor of long enough duration, and only a handful of Johnson’s men could get out. Finally, about 1225, Colonel Mizony brought every weapon he had to bear on the Japanese positions along the cliff and in Hell’s Pocket. Under cover of this fire the remainder of Company I was able to crawl and scramble back to the cover of the trees.96 Casualties in the 3rd Battalion, 106th, alone, for the day had amounted to 14 killed and 109 wounded.97

Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 106th Infantry, had been ordered up to relieve the 3rd Battalion. The relief was accomplished at 1515.98 Upon assuming its position in the line the 1st Battalion was ordered to dig in for the night since it was considered too late in the day to launch further attacks into the valley.99

While the 3rd Battalion had been engaged in trying to push out into the valley, Company G, on the left flank, had advanced no more than two hundred yards during the day. The unit had not itself encountered much enemy fire, but when Company L ran into so much trouble during the morning, Captain Tarrant held his line firm rather than push out ahead of the unit on his right.100

The attempt of the 106th Infantry to push up Death Valley by frontal assault had failed again. In the words of Colonel Ayers, “We were thrown right back on to the original line of departure.”101

Once again corps headquarters ordered the 27th Division to renew the attack into the valley next morning with the “main effort on the left.”102 General Ralph Smith, however, now decided that any further headlong rush up the valley would only result in increased casualties, and ordered his division to make the main effort on the right.103 Beginning on the morning of the 25th, the 2nd Battalion, 106th Infantry, would take up positions along the entrance to the valley and contain the Japanese there while the 165th Infantry

and the other two battalions of the 106th would circle around the east (right) flank and come out into the valley at its northern end to the rear of the Japanese positions. This, it was hoped, would put the Army division abreast of the two Marine divisions, and the encircled Japanese in Death Valley could then be mopped up at leisure.104

There is no evidence that this discrepancy between corps and division orders was ever noted at the time. In any case, before he could put this plan into execution, General Ralph Smith was relieved of his command, and it was left to his successor, General Jarman, to solve the problem of Death Valley.105

24 June: Action on the Flanks

On the right of the corps line, the 4th Marine Division was ordered to press eastward across Kagman Peninsula and secure that area before reorienting its drive toward the north of the island. The division jumped off on schedule at 0800, the 24th Marines on the right, the 23rd on the left. The 24th Regiment moved out rapidly along the coast to Kagman Peninsula against “moderate” resistance. By the end of the day the 24th Marines had advanced about 1200 yards.

On its left the 23rd Marines was initially held up by a pocket of resistance on the slopes of Hill 600 that marked the boundary line between the Marine division and the Army division. About noon the Marine regiment detoured the pocket and commenced to swing around the arc toward Kagman Peninsula, pivoting on the 24th Marines on its right. As the 23rd Regiment accelerated its swing, the gap between it and the 165th Infantry increased and toward late afternoon amounted to from 800 to 1,000 yards. By 1630 Chacha village was overrun and the advance halted for the night since the gap on the left precluded any further progress. The 1st Battalion, 23rd Marines, in division reserve, was ordered to occupy Hill 600 and assist its parent regiment in patrolling the gap. Opposition in the 4th Division’s zone on the 24th was characterized as “moderate” and “light,” although total casualties came to 380, including killed, wounded, and missing in action.106

To the west (left) of Death Valley the 2nd Marine Division was drawn up abreast, from right to left, 8th Marines (with the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, attached), 6th Marines, and 2nd Marines. On the right flank the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, was struggling along the cliff overlooking Death Valley. The ground was “a tangle of tree ferns and aerial tree-roots overgrown with a matting of vines. This formation led up to a ridge, access to which required an almost vertical climb.”107 By nightfall the battalion had succeeded in climbing the ridge, which connected with and was within machine gun range of the summit of Mount Tapotchau. The battalion’s advance for the day was about 800 yards.108

During this movement of the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, Company F of the 106th Infantry was virtually an integral

part of the Marine battalion and had been ordered by its own battalion headquarters to gear its movements to those of the marines.109 About 1230, F Company came to a halt when the marines on its left engaged in a fire fight. The company’s right flank rested along the edge of the cliff overlooking Death Valley just opposite the north rim of Hell’s Pocket. The terrain to the right consisted of a down-sloping nose of ground that broke off abruptly in the cliffs that scaled down the valley. Capt. Roderick V. Le Mieux, the company commander, ordered a patrol to probe down this nose and investigate the source of enemy rifle fire coming from that direction. The patrol soon flushed a covey of Japanese and a full-scale fire fight developed. The patrol leader, finding himself outnumbered, returned for more men. With the larger group he again went down the nose and succeeded in driving the enemy back down the hill.110

Meanwhile, Captain Le Mieux had moved ahead a short distance and observed a Japanese artillery piece in a cave in the side of the cliff about 500 yards to his front. The Japanese were playing a hide and seek game with the piece, running it out of the cliff to fire at the line of trees along the south edge of the valley below, then quickly dragging it back under cover. Le Mieux observed about a hundred of the enemy in the vicinity of this position as well as a large ammunition dump. He ordered up heavy weapons from Company H, which succeeded in catching the gun out of the cave and destroying it. In addition they blew up the ammunition dump, killing about thirty Japanese. Shortly thereafter an enemy patrol was discovered advancing toward the heavy weapons outpost. Rifle fire and grenades quickly dispersed the Japanese, but not before Captain Le Mieux received a serious fragmentation wound and had to be replaced by 1st Lt. Herbert N. Slate, the company executive officer. A few minutes later the company was ordered to pull back to the left and to tighten up the lines before digging in for the night.

In the center, the 8th Marines advanced with no particular difficulty, maintaining contact with units on both of its flanks. The battalion on the regimental left, on the other hand, after advancing a short distance, encountered heavy enemy resistance in an area honeycombed with caves and irregular coral limestone formations covered with trees and undergrowth. This was the same pocket that had retarded the battalion on the previous day. Contact with the 6th Marines on the left was temporarily broken. Shortly after noon the pocket was cleaned out and contact was restored with the regiment on the left. The advance continued until late afternoon and by the time the 8th Marines dug in for the night it had registered a day’s gain of about 700 yards.111

The advance of the 6th Marines in the division center was not so rapid, especially on the right flank where it faced cliffs and thickly wooded ravines and encountered strong enemy positions in natural cave formations. By evening the regiment had progressed from about 900 yards on the left to 500 to 600 yards on the right. The regimental lines had become too extended

In Hell’s Pocket area

for safety, and an additional company was committed to the line.112

On the division left the 2nd Marines jumped off at 0800. On its right, progress was slow against heavy fire from a hill, just southeast of Garapan, that the marines did not occupy until 1500. Shortly thereafter the Japanese counterattacked the hill, which from their side (north) was virtually a cliff. Firing with muzzles depressed against the enemy below, the marines easily repulsed the attack and dug in for the night along the ridge overlooking “Radio Road,” which ran at right angles to the line of advance. Meanwhile, the battalion on the left had quickly advanced 500 yards along the beach into the southern outskirts of Garapan itself. Around 1625, as these men were preparing their defenses along the flatlands bordering the sea, seven enemy tanks unaccompanied by infantrymen suddenly moved out from Garapan against them. Marine tanks and 75-mm. halftracks were rushed in and quickly broke up the attack, destroying six of the Japanese vehicles and routing the seventh. The 2nd Marines had now reached the O-6 line and would again have to hold up until the units on its right came abreast. Casualties for the entire 2nd Division on the 24th amounted to 31 killed, 165 wounded, and one missing in action.113

Inland of Garapan Harbor from hill position southeast of the town, 24 June

After two days of fighting on a three divisional front, the attack of Holland Smith’s corps against the center of the Japanese main line of resistance had stalled. On the right, the 4th Marine Division had overrun most of Kagman Peninsula, an area that presented no particular terrain problems but that still contained plenty of live Japanese, judging from the casualties suffered there by the marines. On the left, the 2nd Marine Division had fought its way into the outskirts of Garapan and up the craggy approaches to Mount Tapotchau, although it would take another day to reach the summit of the mountain. In the corps center, the 165th Infantry on the 27th Division’s right had captured Hill Love, but had made no further advance along the hill system called Purple Heart Ridge. Progress of the 106th Infantry into Death Valley had been negligible. Thus, in the center – the 27th Division zone – the corps line bent back as much as 1,500 yards. Total reported casualties in the 4th Marine Division for the two days were 812; for the 2nd Marine Division, 333; for the 27th Infantry Division, 277.114