Part Three: Tinian

Blank page

Chapter 13: American and Japanese Plans

Writing after the war, Admiral Spruance expressed the opinion, “The Tinian operation was probably the most brilliantly conceived and executed amphibious operation in World War II.”1 To General Holland Smith’s mind, “Tinian was the perfect amphibious operation in the Pacific war.”2 Historians have – by and large – endorsed these sentiments.3

Much of this praise is well deserved, although a close examination of the facts reveals that these, like most superlatives, are somewhat misleading. The invasion of Tinian, like other military operations, was not entirely without flaw. Various deficiencies can be charged to both plan and execution. Yet, as an exercise in amphibious skill it must be given a superior rating, and as a demonstration of ingenuity it stands as second to no other landing operation in the Pacific war.

Situated only about 3.5 miles off the southern coast of Saipan, Tinian is the smaller of the two islands. (Map IV) From Ushi Point in the north to Lalo Point in the south, it measures about 12.5 miles, and in width it never extends much more than 5 miles.4 In one respect its terrain is not as formidable for would-be attackers than that of Saipan – it is far less mountainous. In the northern part of the island Mount Lasso rises to 564 feet, or only a little more than a third of the height of Tapotchau. Another hill mass of almost the same height dominates the southern tip of the island and terminates in heavily fissured cliffs that drop steeply into the sea. Most of the rest of the island is an undulating plain, which in the summer of 1944 was planted in neat checkerboard fields of sugar cane.

It was indeed the relative flatness of Tinian’s terrain that made it such a desirable objective – that and the fact that its proximity to Saipan made its retention by the Japanese militarily inadmissible. Tinian’s sweeping plains and gentle slopes offered better sites for bomber fields than its more mountainous sister island, and of course one of the main objectives of the Marianas operation was to obtain sites for air bases for very long range bombers. To a limited extent, the Japanese had already realized this possibility and near Ushi Point had constructed an airfield that boasted a runway almost a thousand feet longer than Aslito’s. In addition, smaller fields were located just south of the Ushi Point field and at Gurguan Point, and another was under

Coastal area, northwest Tinian, showing WHITE Beach areas, checkerboard terrain inland, and Ushi Point airfield in background

construction just northeast of Tinian Town.5

But if the island was well suited by nature for the construction of airfields, its natural features were also well disposed to obstruct a landing from the sea. Tinian is really a plateau jutting up from the surrounding ocean, and most of its coast line consists of cliffs rising sharply out of the water. Only in four places is this solid cliff line interrupted. Inland of Sunharon Bay, in the area of Tinian Town on the southwest coast, the land runs gradually to the sea, offering a fairly wide expanse of beach protected by the usual reef line. South of Asiga Point on the east coast there is an indenture in the cliff wall that forms a small approachable beach about 125 yards in length. The northwest coast line offers other possible routes of ingress through the cliffs over two tiny beaches about 60 and 50 yards in length, respectively.6

The peculiar features of the coast line placed American planners in a dilemma. The beaches off Tinian Town were obviously the best suited for a landing operation, but by the same token they were the best fortified and defended. The other beaches, which were little more than dents in the cliff line, were obviously not desirable sites for an amphibious assault of corps dimensions. The risks of troops and supplies being congested to the point of immobility as they tried to pour through these narrow bottlenecks were considerable and alarming. For these reasons, which were just as apparent to the Japanese as to the Americans, defenses on the smaller

beaches were less formidable than those elsewhere.

In the end, the American planners seized the second rather than the first horn of their dilemma, chose the narrow beaches on the northwest coast, and accepted the risks that troops, equipment, and supplies might pile up in hopeless confusion at the water’s edge. Having made the choice, the planners were compelled to devise special means of overcoming the accepted risks. This involved working out novel techniques that were radical modifications of standard amphibious doctrine as it had been evolved during the war in the Pacific. Paradoxically then the invasion of Tinian was a “perfect amphibious operation” largely because it was atypical rather than typical – because of its numerous departures from, rather than its strict adherence to, accepted amphibious doctrine.

Plan for the Invasion

From the very outset of the planning for the seizure of the southern Marianas, Tinian had been considered one of the three main targets of the operation. Holland Smith’s Northern Troops and Landing Force was ordered to “land, seize, occupy and defend SAIPAN Island, and then ... be prepared for further operations to seize, occupy and defend TINIAN Island.”7 Consequently, planning for the Tinian phase commenced at the same time as that for the capture of Saipan and was continuous until the very day of the landing on Saipan. By the time Admiral Turner’s task force set sail from Pearl Harbor, maps, photographs, and charts of Tinian had been distributed and tentative arrangements had been made for loading and for resupply shipping. While at sea, Holland Smith’s staff had more leisure than earlier to concern itself with this phase of the operation, and by the time the ships reached Eniwetok a draft plan was ready for the commanding general. In devising this plan, the staff gave due consideration to the relative merits of the various landing beaches and recommended that a landing be made on northern Tinian in order to make full use of artillery emplaced on southern Saipan.8

While the fighting for Saipan was in process, the Americans were afforded ideal opportunities for scrutinizing the island to the south from every angle. Beginning on 20 June, when artillery first bombarded Tinian from southern Saipan,9 observation planes flew daily over northern Tinian. Frequent photo reconnaissance missions were flown, and many valuable documents throwing light on Tinian’s defenses were captured on Saipan.10 Opportunities for gathering intelligence were almost without limit, and it is doubtful if any single enemy island was better reconnoitered during the Pacific war.

With Saipan secured and the preparations for the next landing in mid-passage, a change in command within the Northern Troops and Landing Force was ordered. On 12 July General Holland Smith was relieved and ordered to take command of Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, a newly created headquarters for all Marine Corps combat units in the theater. The new commanding general of Northern Troops and Landing Force was General Schmidt, who

was in turn relieved of his command of the 4th Marine Division by General Cates.11 Concurrently, a shift in the naval command structure took place. Admiral Hill, who had served as Admiral Turner’s second in command, took over a reconstituted Northern Attack Force (Task Force 52) and thus became responsible, under the Commander, Joint Expeditionary Force (Admiral Turner as Commander, Task Force 51), for the capture of Tinian.12

As planning for Tinian went into high gear, it was becoming increasingly apparent to all hands that the original concept of landing the assault troops somewhere in the northern part of the island was sound. Members of the staff of the 4th Marine Division, notably Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson, the division’s planning officer, had already decided that an amphibious landing in this area was desirable. Working independently of the Marines, Admiral Hill had arrived at the same conclusion.13 All agreed that the Tinian Town area was too well defended to justify an amphibious assault there and that the advantages of heavy artillery support for landings on the northern beaches were too considerable to ignore.

All, that is, but one. Admiral Turner was still not convinced. In his mind, the Tinian Town beaches offered important advantages that should not be lightly dismissed. From the point of view of gradient and inland approaches, the Tinian Town beaches were even more favorable to the attacker than those used on Saipan and certainly far better than Tinian’s other beaches. Also, Sunharon Bay offered an excellent protected harbor for small craft and good facilities for unloading supplies, once the beachhead was secured. On the other hand, the beaches in the northern half of the island, argued the admiral, were too narrow to permit a rapid landing of a force of two divisions with full supplies and equipment, and if the weather took a turn for the worse the shore-to-shore movement of supplies in small craft from Saipan might be seriously endangered. In addition, an advance down the full length of the island would take too much time, and the troops would soon outrun their artillery support based on Saipan – an especially dangerous prospect should weather conditions forbid shifting the heavy artillery pieces from Saipan to Tinian.14

In the light of these objections and out of ordinary considerations of military caution, General Schmidt ordered a physical reconnaissance of the northern beaches. The task fell to the Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion, V Amphibious Corps, commanded by Capt. James L. Jones, USMCR, and naval Underwater Demolition Teams 5 and 7, commanded by Lt. Comdr. Draper L. Kauffman, USN, and Lt. Richard F. Burke, USN, respectively. Their job was to reconnoiter YELLOW Beach 1 on the eastern coast below Asiga Point and WHITE Beaches 1 and 2 on the northwestern coast. Under cover of darkness the three groups were to be carried part way to their destinations by the high-speed transports Gilmer and Stringham. Then, launched in rubber landing boats (LCR’s), they would be paddled to distances about 500 yards offshore and swim in the rest of the way. The men were charged with the responsibility of investigating and securing

Marianas leaders confer at Tinian

Left to right: Rear Adm. Harry Hill, Maj. Gen. Harry A. Schmidt, Admiral Spruance, General Holland Smith, Admiral Turner, Maj. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, and Maj. Gen. Clifton B. Cates.

accurate information concerning the height of surf, the height and nature of the reef shelf, depth of water, location and nature of mines and underwater obstacles, the slope of the bottom off the beaches, the height and nature of cliffs flanking and behind the beaches, exits for vehicles, and the nature of vegetation behind the beaches. The naval personnel would conduct the hydrographic reconnaissance while members of the Marine amphibious reconnaissance group were to reconnoiter the beaches themselves and the terrain inland.15

After dark on 10 July, but well before moonrise, Gilmer and Stringham got under way from Magicienne Bay on the east coast of Saipan to take their respective stations off of YELLOW Beach 1 and WHITE Beaches 1 and 2. As the rubber boats approached YELLOW Beach 1, the men heard sharp reports and thought they were being fired on, but went about their business anyway. Two of the men swam along the cliffs south of the beach and discovered them to be 20 to 25 feet high and unscalable by infantry without ladders or nets. One Marine officer, 2nd Lt. Donald Neff, left two of his men at the high-water mark and worked his way along inland for some thirty yards to investigate the possibilities for vehicle exits. Japanese sentries were apparently patrolling the entire area, but the suspected rifle shots proved to be exploding caps being used by construction workers

nearby. In any case, all hands got back to their ships without being detected.16

Meanwhile, on the other side of the island, the reconnaissance of WHITE Beaches 1 and 2 hit a snag. As the rubber boats cast off they were set rapidly to the north by a strong current that they had not been compensated for. Hence the swimmers assigned to WHITE Beach 2, the southernmost of the two, ended up on WHITE 1, while the second group destined for the latter beach were set ashore about 800 yards to the north. This left WHITE 2 unreconnoitered, and next night another group of swimmers had to return to finish the job.17

The information gathered during the two nights fully justified the valiant labor expended. YELLOW Beach 1 was clearly unsuitable for an amphibious landing. In addition to its natural disadvantages, the beach was strung with strong double-apron wire, and large, floating, contact mines were found anchored about a foot underwater off the reef.18 On the other side of the island no man-made obstacles were reported on WHITE Beaches 1 and 2. Although WHITE Beach 1 to the north was only sixty yards in length, the bluffs that flanked it for about 150 yards on either side were only from six to ten feet in height and offered enough small breaks to permit men to proceed inland in single file without the need of cargo nets or scaling ladders. From the reef to the shore line the water depth was never more than four feet and the gradient was slight. Of the hundred and fifty yards of WHITE Beach 2, only the central seventy yards were approachable by amphibian vehicles, the flanks of the beach being guarded by coral barriers jutting out from the reef. Nevertheless, the barriers offered no obstacle to infantrymen, who could scramble over them and wade the rest of the way in. At two hours before high tide the water inside the reef was nowhere more than four feet in depth.19 In short, although the WHITE Beaches were far from ideal for landing purposes, they were better than YELLOW Beach 1, and except for their narrowness offered no known natural or man-made obstacles.

With this information in hand, Admiral Turner’s objections to a landing on the northwest coast, however strong they may once have been, were overcome. At a meeting held aboard his flagship on 12 July, General Schmidt made a forceful presentation of the case for the WHITE Beaches. An amphibious assault against the strong enemy defenses in the Tinian Town area would be too costly; artillery could be more profitably employed against the northern beaches; Ushi Point airfield would be more quickly seized and made ready; tactical surprise could be obtained; the operation could more easily be conducted as a shore-to-shore movement from Saipan; and, finally, most of the supplies could be preloaded on Saipan and moved on amphibian tractors and trucks directly to inland dumps on Tinian. Admiral Hill concurred, and Admirals Turner and Spruance gave their consent to a landing on WHITE Beaches 1 and 2.20

The next day, 13 July, General Schmidt issued the operation plan that was to govern the invasion of Tinian.21 General Cates’ 4th Marine Division was assigned the task of conducting the amphibious assault

over WHITE Beaches 1 and 2 on JIG Day, which was later established as 24 July. On landing, the division was to make main effort toward Mount Lasso and, before reorganizing, seize the Force Beachhead Line, which included Faibus San Hilo Point, Mount Lasso, and Asiga Point. Once this area was captured, it was presumed that the beachhead would be safe from ground-observed enemy artillery fire. To accomplish the division’s mission General Cates ordered the 24th Marines to land in column of battalions on WHITE Beach 1 on the left, the 25th Marines with two battalions abreast on WHITE Beach 2. The 23rd Marines would remain in division reserve.22

The assault troops would be carried ashore in the customary fashion in amphibian tractors discharged fully loaded from LSTs. Of the 415 tractors assigned to carry troops, 225 were supplied by Army units – the 715th, 773rd, and 534th Amphibian Tractor Battalions. The remainder were Marine LVTs from the 2nd, 5th and 10th Amphibian Tractor Battalions. Because of the narrowness of the landing beaches, only one company of amphibian tanks could be employed in the assault, Company D, 2nd Armored Amphibian Tractor Battalion (Marine). The battalion was ordered to precede the first wave of troops, fire on the beaches after naval gunfire was lifted, and move to the flanks before reaching land. The 708th Armored Amphibian Tank Battalion (Army) was ordered to stand by off the beaches and be prepared to land and support the infantry ashore.23

As before, command of the entire operation was vested in Admiral Turner as Commander, Joint Expeditionary Force (Task Force 51), under Admiral Spruance; General Holland Smith, who still retained his position of Commander, Expeditionary Troops, continued in over-all command of troops ashore. In fact, however, both of these officers had sailed aboard Rocky Mount on 20 July to be on hand for the Guam landings, which took place the next day, and did not return to the Saipan-Tinian area until the 25th.24 During the landing then, Admiral Hill, as Commander, Northern Attack Force (Task Force 52), commanded all naval craft and supporting forces, while General Schmidt commanded the landing forces.25 Even after Admiral Turner returned, Admiral Hill retained the responsibility “for offensive and defensive surface and air action” in the area and for all practical purposes Schmidt remained in tactical control of the troops.26

Because most of the heavy artillery pieces could more profitably be employed from emplacements on Saipan, the 4th Marine Division would carry only 75-mm. pack howitzers in the initial assault. In addition to its own two battalions (1st and 2nd Battalions, 14th Marines), it was loaned the two light battalions of the 2nd Marine Division (1st and 2nd Battalions, 10th Marines). These battalions would be carried ashore in Marine DUKWs. Additional fire power was afforded the division by attaching the 2nd Division’s tank battalion. Army troops (1341st Engineer

LVT with ramp

Battalion) would make up part of the assault division’s shore party, the remainder being provided by the 2nd Battalion, 20th Marines.27

To the rest of General Watson’s 2nd Marine Division was assigned the role of landing in the rear of the assault division once the latter had cleared an initial beachhead and moved inland. Before this, the division was to conduct a demonstration landing off Tinian Town for the purpose of diverting Japanese attention from the main assault to the north.28

The 27th Infantry Division, less the 105th Infantry and less its organic artillery, was to remain in corps reserve and “be prepared to embark in landing craft on 4 hours’ notice and land on order ... on Tinian.”

One of the main justifications for the final decision to land over the unlikely beaches on the northwestern shore of the island was the feasibility of full exploitation of artillery firing from Saipan. Consequently, all of the field pieces in the area except for the four battalions of 75-mm. pack howitzers were turned over to XXIV Corps Artillery during the preliminary and landing phase. General Harper arranged his thirteen battalions, totaling 156 guns and howitzers, into three groupments, all emplaced on southern Saipan. Groupment A, commanded by Col. Raphael Griffin, USMC, consisted of five 105-mm. battalions, two each from the Marine divisions and one from V Amphibious Corps. It was to reinforce the fires of the 75-mm. pack howitzers and be ready to move to Tinian

on order. Groupment B, under the 27th Division’s artillery commander, General Kernan, was made up of all of that division’s organic artillery except the 106th Field Artillery Battalion. It was to reinforce the fires of Groupment A and also to be ready to displace to Tinian. Groupment C, commanded by General Harper himself, contained all the howitzers and guns of XXIV Corps Artillery plus the 106th Field Artillery Battalion. It was to support the attack with counterbattery, neutralization, and harassing fire before the day of the landing, deliver a half-hour preparation on the landing beaches immediately before the scheduled touchdown, and execute long-range counterbattery, harassing, and interdiction fire.29

In addition to the artillery, the troops would of course have the support of carrier-borne aircraft, aircraft based on Aslito field, and naval gunfire. Although all three supporting arms were to be employed against targets everywhere on Tinian, primary responsibility for the northern half was allocated to artillery while naval gunfire and air took over the southern half. The task of coordinating the three was vested in a XXIV Corps Artillery representative at General Schmidt’s headquarters.30

The most unique feature of the plan for Tinian was its logistical provisions. Because only slightly more than 200 yards of beach were available, it was essential that precautions be taken to avoid congestion. Hence, a supply plan was developed that allowed all supplies to cross the beach on wheels or tracks and move directly to division dumps without rehandling. This entailed devising a double shuttle system in which loaded trucks and Athey trailers traveled back and forth between the base supply dumps on Saipan and division supply dumps on Tinian, and all amphibian vehicles carrying supplies between ship and shore moved directly to division dumps. The objective was to avoid any manhandling of supplies on the beaches themselves. The solution represented a marked departure from standard amphibious practice and was made possible, of course, by the proximity of Tinian to the supply center on Saipan.31

The plan called for preloading thirty-two LSTs and two LSDs at Saipan with top-deck loads of all necessary supplies except fuel. Ten LSTs were allotted to each Marine division, eight to general reserve, and four primarily to 75-mm. artillery. All amphibian tractors and trucks available, both Army and Marine Corps, were initially assigned to the 4th Marine Division, but after the assault was over were to be distributed between the two divisions. The supplies were loaded on the LSTs in slings, and the ships carried crawler cranes on their top decks so that the slings could drop supplies into DUKWs and LVTs coming alongside. To carry out the shuttle system, the plan called for preloading eighty-eight cargo trucks and twenty-five Athey trailers on Saipan to be taken to Tinian aboard LCTs and LCMs. A special provision for fuel supply was made. Seven ponton barges loaded with drums of captured Japanese gasoline and matching lubricants were to be towed to positions off the landing beaches to act as floating supply and fueling points for LVTs and DUKWs. Other fuels for initially refueling the trucks were

placed on barges that were to be spotted off the beaches.32

One other innovation introduced in the Tinian campaign was a special portable LVT bow ramp. Ten amphibian tractors were equipped with this device so as to provide a means for extending the narrow beach area. The ramps were so constructed that an LVT could drive up to a cliff flanking the beaches, place the ramp in position along the ledge, then back down leaving the ramp to act as a sort of causeway by which other vehicles could get to shore.33

Finally, precautions were taken to supply the troops in case of unexpected bad weather after the landing. Plans were made to drop about 30 tons of supplies by parachute and to deliver 100 tons by air daily to Ushi Point airfield as soon as it had been captured.34

The Enemy

As already observed, the opportunities for gaining detailed intelligence of Tinian’s defenses were superior to those enjoyed by American forces in most Pacific operations. Proof of this superiority lies in the accuracy with which General Schmidt’s staff was able to estimate Japanese strength and dispositions. As of 13 July they predicted, on the basis of captured documents, photo reconnaissance, and other intelligence data, that the strength of the Tinian garrison came to 8,350, plus possible home guard units. The main part of this force was believed to consist of the 50th Infantry Regiment (reinforced) – about 4,000 men – and the 56th Keibitai (Naval Guard Force) – about 1,100 men – plus sundry air defense, base force, and construction personnel. The Army troops were believed to be disposed in three sectors, northern, western, and southern, which included respectively the Ushi Point–Asiga Bay region, the west coast north of Gurguan Point including WHITE Beaches 1 and 2, and the southern part of the island including Tinian Town. The northern and southern sectors were thought to be defended by at least one infantry battalion each, but the western sector where WHITE Beaches 1 and 2 were located had, it was estimated, only one company with one antitank squad. It was predicted that in each of these sectors the Japanese would first try to repulse the landing at the water’s edge and would shift two thirds of each defense force from the areas not under attack to the beaches where the actual landings were taking place. A reserve force of one battalion was believed to be located near Mount Lasso, and it too was expected to move to the specific area under amphibious attack. One artillery battalion was thought to be located in the Tinian Harbor area, one battery near Asiga Bay. These estimates, except those pertaining to artillery strength, were remarkably accurate.

The defense of Tinian was in the charge of Col. Takashi Ogata, commanding officer, 50th Infantry Regiment, which represented the bulk of the Japanese Army forces on the island. Other important units were the 1st Battalion, 135th Infantry; the Tank Company, 18th Infantry; the 56th Naval Guard Force; and two naval antiaircraft defense units. Altogether, Ogata had four Army infantry battalions, none of which were straggler units, plus additional

Table 1: Estimated strength of the Japanese garrison on Tinian

| Unit | Unit Commander | Est. Strength | |

| Grand total | 8,039 | ||

| Army – total | 3,929 | ||

|

– 50th Infantry Regiment |

Col. Takashi Ogata | ||

|

– Headquarters |

–– | 60 | |

|

– 1st Battalion |

–– | 576 | a |

|

– 2nd Battalion |

–– | 576 | |

|

– 3rd Battalion |

–– | 576 | |

|

– Artillery Battalion (12 75-mm. mountain guns) |

Maj. Katuro Kahi | 360 | |

|

– Engineer Company |

Lt. Chuichi Yano | 169 | |

|

– Antitank Platoon (6 37-mm. antitank guns) |

2nd Lt. Moto Otani | 42 | |

|

– Signal Company |

Lt. Hayashi | 141 | |

|

– Supply Company |

Lt. Kenishi Nozaki | 200 | |

|

– Medical Company |

Lt. Masaakira Narazawa | 130 | |

|

– Fortification Detachment |

Capt. Masagi Hiruma | 60 | |

|

– 1st Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment |

Capt. Isumi | 714 | b |

|

– 18th Infantry Regiment Tank Company (9 tanks and 2 amphibian trucks) |

Lt. Katsuo Shikamura | 65 | c |

|

– 264th Independent Motor Transport Company platoon |

–– | 60 | |

|

– 29th Field Hospital Detachment |

–– | 200 | |

| Navy – total | 4,110 | ||

|

– 56th Naval Guard Force |

Capt. Goichi Oya | 950 | |

|

– 82nd Antiaircraft Defense Unit (24 25-mm. antitank guns) |

Lt.(s.g.) Kichitaro Tanaka | 200 | |

|

– 83rd Antiaircraft Defense Unit (6 dual-purpose 75-mm. guns) |

Lt.(s.g.)Meiki Tanka | 250 | |

|

– 233rd Construction Unit |

–– | 600 | |

|

– Headquarters, 1st Air Fleet |

Vice Adm. Kakuji Kakuta | 200 | |

|

– Air Units (mostly 523rd TOKA) |

–– | 1,110 | |

|

– Miscellaneous construction personnel |

–– | 800 |

––. Unknown.

a. Strength figures for the three infantry regiments given here are somewhat lower than those estimated by NTLF, chiefly because the latter included attached artillery units in its infantry strength estimates. The figure 576 is the actual strength of the 2nd Battalion, 50th Infantry, as of February 1944 (Headquarters, 2nd Battalion, 50th Infantry Regiment, War Diary, February 1944, NA 27434). It is assumed that the other regiments were approximately the same.

b. Estimated on the basis of unit records for May 1944 of Headquarters, 1st and 3rd Companies, and Infantry Gun Company NA 22237, 27394, 27393).

c. Shikamura Tai War Diary, 29 April to 23 July 1944 (NA 22831).

Source: These strength figures are derived from NTLF Rpt Marianas, Phase III, Incl A, G-2 Rpt, pp. 24-30 and TF 56 Rpt FORAGER, Annex A, G-2 Rpt, p. 57.

infantry in the 56th Naval Guard Force and other naval units. For artillery, the Japanese commander had his regimental artillery battalion, the coast artillery manned by part of the 56th Naval Guard Force, and two naval antiaircraft defense units. The 18th Infantry Tank Company had nine tanks, which constituted the entire armored strength present. Total personnel strength, as indicated in Table I, came to a little more than eight thousand officers and men, Army and Navy.

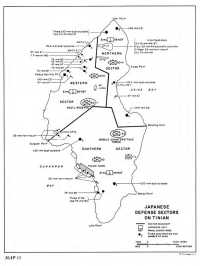

As foreseen by General Schmidt’s intelligence section, the Japanese Army plan for the defense of Tinian provided for the disposition of forces in three sectors. (Map 15.) The northern sector force guarding Ushi Point, Asiga Bay, and part of Masalog Point was the responsibility of the 2nd Battalion, 50th Infantry, and a platoon of engineers; the western sector, containing Mount Lasso and the northwest coast, was guarded only by the 3rd Company, 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry, and an antitank squad. Regimental reserve in the southern sector consisted of the 1st Battalion, 50th Infantry, less the 3rd Company and less one antitank squad and was located about 3,000 yards southeast of Faibus San Hilo Point. The 1st Battalion, 135th Infantry, was designated “mobile counterattack force,” and was in effect another reserve. Ogata’s armored strength came to only nine tanks of the Tank Company, 18th Infantry, which was located on the northeast side of Marpo Well with orders to advance either to Tinian Town or Asiga Bay, wherever the landings came. In addition, this company had two vehicles rarely found among Japanese forces, amphibious trucks similar to the American DUKW.35

Japanese naval personnel on the island were under the command of Capt. Goichi Oya, who reported to Colonel Ogata. There was another, more senior, naval officer present on the island, but he held no position in the chain of command and had nothing to do with the defense of Tinian. This was Vice Adm. Kakuji Kakuta, Commander in Chief, 1st Air Fleet, who was responsible only to Admiral Nagumo of the Central Pacific Area Fleet. After the loss of most of his planes in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Kakuta made several efforts to escape Tinian by submarine. Each time he failed, and in the end he apparently committed suicide.36

Captain Oya appears to have made some effort to integrate his command with that of the Army. The 56th Naval Guard Force was charged with the defense of the air bases, defense of harbor installations and ships in the harbor, and destruction of enemy attack forces. The force was divided into two parts. One was to man the coastal defense guns and antiaircraft weapons and the other, called the Coastal Security Force, was to maintain small coastal patrol boats and lay beach mines. No matter what the intentions of either commander, however, it would seem that there was little real coordination or even cooperation between Army and Navy forces. There may have been serious inter-service friction.37 This is at least suggested in the captured diary of one Army noncommissioned officer, who wrote:

15 June: The Naval aviators are robbers. There aren’t any planes. When they ran off to the mountains, they stole Army provisions, robbed people of their fruits and took cars. ...

25 June: Sailors have stolen our provisions. They took food off to the mountains. We must bear with such until the day of decisive battle. ...

6 July: Did Vice-Admiral Kakuta when he heard that the enemy had entered our area go to sleep with joy?38

Map 15: Japanese defense sectors on Tinian

Responsibility for coastal defense was divided about equally between Army and Navy. Because of the small number of beaches over which hostile troops could possibly land, the problem was somewhat simplified. Consequently, even with the rather limited means at hand, it was possible for the Japanese to distribute their fixed gun positions so as to place a fairly heavy guard around the only feasible approaches to the shore. The Tinian Town area boasted three British-made 6-inch coastal defense guns, two 75-mm. mountain guns,39 and six 25-mm. twin-mount antiaircraft and antitank automatic cannons. Just up the coast from Tinian Town in the area of Gurguan Point were three 120-mm. naval dual-purpose guns and nine 25-mm. twin mounts that guarded the northern approaches to Sunharon Bay as well as the Gurguan Point airfield. The northwest coast from Ushi Point to Faibus San Hilo Point, including the area of WHITE Beaches 1 and 2, was quite well fortified, especially considering that the Japanese had no real expectations of hostile amphibious landings in that area. Altogether, this stretch of coast line contained three 140-mm. coastal defense guns, two 75-mm. mountain guns, two 7.7-mm. heavy machine guns in pillboxes, one 37-mm. covered antitank gun, two 13-mm. antiaircraft and antitank machine guns, two 76.2-mm. dual-purpose guns, and three 120-mm. naval and dual-purpose guns. In addition, in the hills behind and within range of this shore line were two 47-mm. antitank guns, one 37-mm. antitank gun, and five 75-mm. mountain guns. Guarding Ushi Point airfield were six 13-mm. antiaircraft and antitank guns, fifteen 25-mm. twin mounts, four 20-mm. antiaircraft automatic cannons, and six 75-mm. antiaircraft guns. On the northeast coast, between Ushi Point and Masalog Point, were seven 140-mm. coastal defense guns, three 76.2-mm. dual-purpose guns, one 37-mm. antitank gun, and twenty-three pillboxes containing machine guns of unknown caliber. Except for the coastal defense guns, all of these weapons were concentrated in the area of YELLOW Beach 1, south of Asiga Point. Finally, inland from Marpo Point on the southeast coast there were four 120-mm. dual-purpose guns.40

The most surprising feature of the distribution of fixed positions is the relatively heavy concentration of guns within range of WHITE Beaches 1 and 2. In spite of the fact that General Ogata assigned a low priority to the infantry defenses in that region, it is quite apparent that the Japanese were by no means entirely neglectful of the area. The figures cited here of course give no indication of the damage wrought on these positions by naval gunfire, field artillery, and aerial bombardment before the landing. But had American intelligence estimates of Japanese artillery dispositions been as accurate as they were in other respects, the plan for an amphibious landing over the WHITE Beaches might not have been undertaken so optimistically.

More accurate knowledge of Japanese mining activities off of WHITE Beaches 1 and 2 might also have given the American

planners pause. The reports of the amphibious reconnaissance and underwater demolition groups to the contrary, the Japanese had set up a mine defense of sorts along the northwest coast. Off WHITE Beach 1 they had laid a dozen horned mines, though by the time of the landing these had deteriorated to the point of impotence. WHITE Beach 2 was mined in depth. Hemispherical mines were placed in two lines offshore, conical yardstick, and box mines covered the exits from the beach. Altogether, more than a hundred horned mines were laid in the area. In addition, there were many antipersonnel mines and booby traps concealed in cases of beer, watches, and souvenir items scattered inland. On the other side of the island, YELLOW Beach 1 was protected by twenty-three horned mines and by double-apron barbed wire. In the Tinian Town area a strip about thirty-five yards wide from the pier north along the water’s edge to the sugar mill was completely mined. The beach south of the pier was laid with hemispherical mines that had steel rods lashed across the horns. Behind these were conical mines placed in natural lanes of approach from the shore line.

Until the very eve of the landing, the Japanese worked furiously to improve their beach defenses, especially in the Tinian Town and Asiga Bay areas. Even the gathering rain of American shells and bombs failed to stop them entirely, for when the pressure became too great they worked at night and holed up during the day.41

Ogata was well aware that an invasion of Tinian was inevitable, and in one respect he was more fortunate than Saito.42 Unlike the commanding general of Saipan, he had no stragglers to deal with, and his Army troops were well trained, well equipped, and well integrated under a unified command. He had had his regiment since August of 1940. For almost four years before moving to Tinian the unit had been stationed in Manchuria, and, under the semi-field conditions obtaining there, Ogata was able to develop a high degree of homogeneity and esprit.43

Ogata’s plan of defense conformed to standard Japanese doctrine at this stage in the war. The enemy was to be destroyed at the water’s edge if possible and, if not, was to be harried out of his beachhead by a counterattack on the night following the landing. “But,” read the order, “in the eventuality we have been unable to expel the enemy ... we will gradually fall back on our prepared positions in the southern part of the island and defend them to the last man.”44

Whichever of the three possible beach areas was hit by the Americans, the bulk of the Japanese forces in the two other sectors was to rush to the point of attack and close arms with the invader. Tinian Town and Asiga Bay were strongly favored as the probable landing beaches, the northwest coast being relegated to third place in Ogata’s list of priorities.45 Thus, when the Americans chose this unlikely lane of approach, they achieved complete tactical surprise – a rare accomplishment in the Central Pacific theater of war.

Blank page