Chapter 17: The Fight for the Beachhead

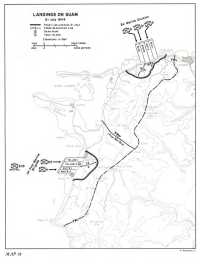

Map 18: Landings on Guam, 21 July 1944

As evening of 20 July closed in, Admiral Conolly and those around him who were responsible for the invasion of Guam looked forward with high optimism to the success of their enterprise. Reports indicated that “all known major defensive installations in position to interfere with the transports approach and the landing have been destroyed and the assault beaches cleared of obstructions and searched for mines with negative results.”1 The weather forecast for 21 July was excellent. Conolly confirmed W Day as 21 July and H Hour as 0830. To his entire task force he promised, “conditions are most favorable for a successful landing.”

Ashore, the Japanese command was not to be outmatched, at least in outward show of confidence. To the men of the 48th Independent Mixed Brigade, General Shigematsu announced encouragingly: “The enemy, overconfident because of his successful landing on Saipan, is planning a reckless and insufficiently prepared landing on Guam. We have an excellent opportunity to annihilate him upon the beaches. We are dedicated to the task of destroying this enemy, and are confident that we shall comply with the Imperial wish.”2

W-Day Preliminary Bombardment

The morning of 21 July dawned bright and clear as predicted. The wind was light, the sea calm. At 0530 came the first order to commence fire and for almost three hours the din and smoke of incessant naval salvos filled the air over the transport areas and shot up great geysers of dirt and debris ashore. From their flagships Appalachian and George Clymer, Admirals Conolly and Reifsnider directed the bombardment of the Asan and Agat beaches, respectively. (Map 18.) Ships’ fire was slow and deliberate, concentrating on the landing beaches themselves, their flanks, and the areas immediately inland. On this day alone the fire support ships would expend a total of 342 rounds of 16-inch shells, 1,152 rounds of 14-inch, 1,332 rounds of 8-inch, 2,430 rounds of 6-inch, 13,130 rounds of 5-inch, and 9,000 4.5-inch rockets.3

Twenty minutes after the opening of this tremendous naval bombardment, the first planes appeared overhead to provide cover against possible enemy air or submarine attack. At 0615 a roving patrol of twelve fighters, nine bombers, and five torpedo planes from the carrier Wasp made the day’s first strike – against tiny Cabras Island lying just off the right flank of the 3rd

First wave of landing craft heads for Agat beaches. Smoke is from preinvasion naval shelling and air bombardment

Marine Division’s zone of attack. These and all other planes from Mitscher’s Task Force 58, as well as those flown from the escort carriers of Task Force 53, were under the control of Conolly’s Commander, Support Aircraft, aboard Appalachian. Also on station was an airborne air coordinator to direct scheduled air strikes and such other attacks as might later be ordered by the Commander, Support Aircraft.4

From 0715 to 0815 planes from Mitscher’s fleet bombed and strafed the fourteen miles of coast line from Agana to Bangi Point. During this period of simultaneous attack from air and sea, naval guns were restricted to a maximum range of 8,000 yards to insure that the ordinate of their shells would be no higher than 1,200 feet. Pilots were instructed to pull out of their runs before reaching as low as 1,500 feet – a precaution taken to save American planes from being struck by friendly naval fire while at the same time rendering unnecessary the usual cessation of naval

Asan’s GREEN and BLUE beaches stretch from Asan town (left center) to Asan Point (lower right)

fire during the aerial strikes. Throughout this hour of bombardment, 312 of Mitscher’s planes pounded the northern and southern landing beaches and their flanks with a total of 124 tons of bombs.5

Over each of the two sets of beaches flew a naval observation plane equipped with parachute flares, which were released when the troop-laden landing vehicles were 1,200 yards (8 minutes) from the shore – a signal to the support ships to step up their fire. Immediately, the support ships commenced a last mighty bombardment of the beaches and maintained it until the troops were reported to be only 300 yards from the shore. Then all naval fire was shifted inland, to continue even after the first of the marines had touched land. The parachute flares were also the signal for a special H Hour strike by aircraft from Task Force 53. A flight of forty-four fighters strafed the two landing beaches until the first troops were almost ashore, then shifted their attack 1,500 to 2,500 yards inland. This strike was followed by a flight of twenty-four, whose task was to

keep the enemy down until the first wave of marines could cross the open beaches and gain cover.6

From Ship to Shore

In the midst of all this fire and smoke, the ships carrying the assault troops arrived on schedule and took station in the transport areas off the landing beaches. Amphibian tanks and amphibian tractors laden with marines eased their way into the water through the open bow doors of the LSTs, transports lowered their LCVPs over the sides, and the LSD’s let down their tail gates to permit their tank-carrying LCMs to become waterborne.

The pattern of the ship-to-shore movement was essentially the same for the northern and southern beaches – a pattern, in fact, that had been standardized in the Pacific since the invasion of the Marshalls. Ahead of the first waves of landing vehicles bound for each set of beaches went a line of nine LCI(G)’s firing 4.5-inch rockets and 40-mm. and 20-mm. guns as they came within range of the shore line. Then came a wave of amphibian tanks firing 37-mm. and 75-mm. guns to escort the marines over the reef and onto the beaches. Close astern were the successive waves of amphibian tractors carrying the assault troops, followed at intervals by LCMs embarking tanks. Reserve troops were loaded in LCVPs that would have to stand by at the edge of the reef until the first waves of tractors had debarked their troops and could return to take more men in from the reef.7

Off the northern beaches the LCI(G)’s crossed the line of departure at 0806 and commenced firing their rockets when they were about 1,000 yards off the shore line. At 0819 the first wave of troop-carrying LVTs reached a line approximately 1,200 yards offshore. Parachute flares were dropped from the observation plane overhead, and three minutes later the last flurry of intense close naval fire on the beaches began. The tempo of firing of the 5-inch guns increased from five to ten rounds per minute. About 300 yards from the shore the LCI(G)’s ceased their salvos of rockets, moved to the flanks, and, along with the destroyers, kept these areas under fire. By then mortar and artillery fire from shore was falling among the approaching tractors. In spite of the pounding they had been receiving from ships and aircraft, the Japanese were able to bring their pieces to bear on the assault waves and destroy nine of the 3rd Marine Division’s amphibian tractors.8 Nevertheless, the waves of vehicles rolled on, and at 0828 the first LVT(A) touched down, two minutes ahead of schedule.9

Off Agat, fire from the shore was even heavier. There, the Japanese greeted the invaders with a hail of small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire for the duration of their approach to the shore. In addition, several 70-mm. guns in well-placed concrete blockhouses enfiladed the beaches and fired at the LVTs as they crossed the reef. On Gaan Point, near the middle of the landing area, a 75-mm. field piece and a 37-mm. gun opened fire as did a 75-mm. field piece on Yona Island to the right. One LCI(G) was hit and thirteen

3rd Marine Division beachhead. All types of invasion craft to background; first-aid station in foreground

amphibian tractors were knocked out.10 Still the landing formation held, and the troops got ashore on schedule.11 In the zone of the 4th Marine Regiment (and there alone along the entire corps landing zone) the amphibian tractors had been ordered to move a thousand yards inland before disembarking their troops. As on Saipan, this scheme failed, and here as elsewhere during the assault on Guam, the leading waves of troops dismounted from their LVTs close to the shore line.12

The Northern Beaches

The 3rd Marine Division plan called for a landing of the assault elements of all three regiments over about 2,500 yards of beach between Asan Point and Adelup Point. From right to left, the 9th Marines was to go ashore on BLUE Beach, the 21st Marines on GREEN Beach, and the 3rd

Marines on RED Beaches 1 and 2. On hitting shore, the division was to capture the cliffs and high ground immediately inland and prepare for further operations to the east and southeast. The 9th Marines was to seize the low ridge facing its beach, protect the division right flank, and be prepared to move along the coast to take Piti Navy Yard and Cabras Island if so ordered. In the center, the 21st Marines was to capture the cliff line to its front. On the left the 3rd Marines was ordered to secure Adelup Point, Chonito Cliff, and the high ground southeast of the cliff.13 (Map VI.)

On the right, the 9th Marines, commanded by Col. Edward A. Craig, moved ahead steadily against fairly heavy machine gun and rifle fire and by the end of the day had secured a beachhead about 1,500 yards in depth.14 In the center, Col. Arthur H. Butler’s 21st Marines found the opposition only moderate, but the terrain “almost impossible.” Ahead lay low cliffs of bare rock mounting to a plateau covered with scrub growth and tangled vines. Intense heat and a shortage of water added to the day’s ordeal, but in spite of the natural obstacles as well as enemy mortar and rifle fire, two battalions had made their way to the top of the cliff and tied in with the 9th Marines on the right by nightfall.

It was on the division left that the day’s most intense and arduous fighting occurred. Northeast of RED Beach 1 was Chonito Cliff, containing a complex system of cave defenses and offering the enemy a perfect opportunity to pour mortar and artillery fire on the low ground below. Inland of RED Beach 2 lay Bundschu Ridge,15 offering the same sort of obstacles. By noon, Chonito Cliff was cleared, but two separate and costly attacks on the ridge to the south failed to make any significant headway, and by nightfall the right flank of Col. W. Carvel Hall’s 3rd Marines was still out of contact with the 21st Marines in the division center.

The day’s casualties on the northern beachhead came to 105 killed, 536 wounded, and 56 missing in action. The cost was more than had been anticipated, yet the results, if far from decisive, were at least hopeful. The beaches themselves were secured, as was Chonito Cliff on the left flank. By late afternoon General Turnage, the division commander, was ashore, and his command post was in operation; division artillery was in position and in the process of registering; division engineers had cut a road to supply the 21st Marines and were at work removing land mines and demolishing cave positions.

The Southern Beaches

According to the operation plan of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, the two Marine regimental combat teams would land in assault, and Col. Vincent J. Tanzola’s 305th Regimental Combat Team of the 77th Infantry Division would be in reserve. The 4th Marines on the right was to go over WHITE Beaches 1 and 2 north of Bangi Point, establish a beachhead, and protect the brigade right flank. On the left, the 22nd Marines was to land on YELLOW

Beaches 1 and 2, occupy the town of Agat, and then drive north to seal off Orote Peninsula at its base. The 305th Infantry, when committed to action on brigade order, would pass through the lines of the 4th Marines and protect the right sector of the beachhead.16 (Map VII.)

The terrain facing the brigade was far more favorable for the attack than that facing the 3rd Marine Division to the north. Low hills and open ground characterized most of the area immediately inland of the landing beaches. In spite of numerous pillboxes still alive with Japanese, both of the assault regiments moved forward rapidly. By early afternoon, the 4th Marines had cleared Bangi Point and Hill 40 just inland and had set up a roadblock supported by five tanks on Harmon Road, which ran east out of Agat. The 22nd Marines captured Agat, which had been mostly reduced to rubble by naval and air bombardment but still contained its share of defenders hiding in the debris. Moving out from Agat, the regiment began to receive artillery fire from the hills beyond and suffered some casualties, as well, from a misplaced American air attack. It was also handicapped by the fact that a communications failure kept the reserve battalion (the 3rd) afloat until too late to participate in the day’s fighting.17

Despite these difficulties, by the close of the first day’s fighting the brigade had established a beachhead ranging in depth approximately 1,300 to 2,300 yards at the cost of only about 350 casualties. Brig. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., came ashore before noon and his command post southeast of Gaan Point was in operation by 1350. Defenses were organized in depth against the expected Japanese night counterattack. Artillery was ashore and registered.

Landing the 305th Infantry

The operation plan for the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade had designated the 305th Regimental Combat Team as brigade reserve, to be used at General Shepherd’s discretion. Accordingly, the brigade commander had ordered one battalion team (later designated the 2nd, commanded by Lt. Col. Robert D. Adair) to be boated and ready at the line of departure by 1030 of the 21st. The other two battalion landing teams would follow the 2nd ashore when and as needed.18

Actually, the first element of the 77th Division to go ashore was a liaison party of four from the 242nd Engineer Combat Battalion, which was attached to the 305th Infantry. Two officers and two enlisted men landed shortly after 0830 on WHITE Beach 1, which they proceeded to reconnoiter. The second group, the first organized element of the division to come ashore, was the reconnaissance party of the 305th Field Artillery Battalion. At 0830 this group was boated in two DUKWs at the line of departure, where it remained for several hours. Finally, the vehicles were ordered ashore, and by midafternoon the reconnaissance party had established itself on WHITE Beach 2.19

Circling landing craft. The 2nd Battalion of the 305th Infantry waited three and a half hours for the signal to go in to the reef

Meanwhile, the infantrymen of Colonel Adair’s 2nd Battalion were climbing down cargo nets from their transports into the bobbing landing craft that were to carry them to the edge of the reef. By 1030 all boats were in position near the line of departure waiting for the signal to go in. For three and a half hours they circled impatiently. At last, at 1405, came the message to proceed to the beach and assemble in an area 300 yards inland from Gaan Point.20

Unfortunately, no amphibian tractors were on hand to transport Adair’s men over the reef and on to the shore line, and of course their LCVPs were too deep-drafted to negotiate either the reef or the shallow waters inland of it. Over the sides of their boats the men climbed, and waded the rest of the way in water at least waist deep. Some lucky few were able to pick up rides in Marine LVTs on the landward side of the reef, but most stumbled in over the rough coral bottom, cutting their shoes en route and occasionally falling into deep pot holes. Luckily, no enemy fire impeded their progress, and except for the dousing they got and the exhaustion they suffered the troops of the 2nd Battalion, 305th, completed their ship-to-shore movement without injury.21

The remaining two battalions of the 305th Infantry encountered even greater difficulties in getting ashore. At 1530 Colonel Tanzola received the message (a

full hour after it had been dispatched) to land the rest of his regiment immediately. With only enough landing craft available to embark one battalion, he ordered Lt. Col. James E. Landrum, Jr., to boat his 1st Battalion and head for the reef. However, naval officers in charge of boat traffic had not been apprised of these orders and refused to permit the landing craft to proceed beyond the line of departure. Finally, at 1730, General Shepherd settled the matter by ordering the regimental commander to land his combat team at once. Again no amphibian tractors were available and again the troops had to make their way through the water on foot. This time conditions were even more adverse. The tide was full, forcing some of the men to swim part of the way, and night was approaching. It was no easy task in view of the fact that the average infantryman was loaded down with a steel helmet and liner, gas mask, life belt, rifle, bayonet, grenade launcher, light pack, two bandoleers of ammunition, a bag full of rifle grenades hung from his neck, another pouch of hand grenades strapped to his thighs, a two-foot long pair of wire cutters tied to his pack, two canteens of water, a first aid pack, and a machete hanging from his cartridge belt. Nevertheless, the troops reached the beach safely after nightfall, although they were scattered and several hundred yards south of Gaan Point, where they were supposed to touch down. Colonel Landrum gathered the better part of his men together and led them to their designated assembly areas inland. The rest had to spend the night on the beach, since after 2130 Marine military police stopped all movement.22

The 3rd Battalion, 305th, commanded by Lt. Col. Edward Chalgren, Jr., took even longer to get to shore. Before the landing craft assigned to the 1st Battalion had returned to the transport area, the report came in that an enemy submarine had been spotted in the area, and all the ships of Transport Division 38 put to sea – including Alpine, aboard which Chalgren’s unit was embarked. Not until 2120 did the ship return, and it was 0330 of the 22nd before the bulk of the battalion completed the complicated transfer from ship to landing craft to shore. To expedite the ship-to-shore movement of his battalion, Chalgren borrowed five LVTs from the Marines. One of these acted as control boat while the other four ferried the troops across the reef in driblets. Even so, some elements failed to reach the beach until 0600, and not for another hour was the unit fully reorganized. Meanwhile, Colonel Tanzola and his staff had debarked and reached the reef line, where they, too, found no transportation waiting them. The regimental commander came upon an abandoned rubber raft, commandeered it, and paddled his way to shore while the rest of his staff waded and swam in.23

Japanese Counterattack

The American troops that dug in along their beachhead perimeters on the night of 21-22 July were well aware that the odds favored an organized enemy counterattack, probably in the early morning hours.

Japanese defensive doctrine prescribed such countermeasures and at both Saipan and Tinian the island commanders had rigidly adhered to doctrine. All along the line the troops were alerted to prepare for the expected attack and took such measures as the terrain and their own dispositions permitted. When the counterthrust did materialize, it was surprisingly feeble, at least in comparison with those that the enemy had launched against the invaders of Saipan and Tinian.

In the zone of the 3rd Marine Division, whose hold on the beachhead was the most precarious, no critical threat to the Marine lines occurred. Mortar and artillery fire falling on the beaches put a temporary end to unloading about 0230, and enemy patrols probed the front lines throughout the night, but that was all.24

Farther south, the Japanese undertook more serious measures. Against the Agat beaches, Colonel Suenaga of the 38th Infantry Regiment himself led a force consisting of at least two infantry battalions supported by tanks. The brunt of the attack, which started about 0100, fell in the zone of the 4th Marines. In two successive waves, the enemy struck the Marine perimeters around Hill 40 and succeeded in penetrating as far as the pack howitzer positions on the beaches before being destroyed or beaten off. Another force, led by four tanks followed by guns mounted on trucks, came down Harmon Road in an apparent attempt to re-establish positions in the town of Agat. Fortunately, the marines had set up a roadblock, and a platoon of Sherman tanks with the help of a single bazooka quickly disposed of the Japanese armor, after which the enemy infantrymen retreated. About the same time, another group of Japanese hit the 1st Battalion’s lines south of the road, and again succeeded in penetrating the defenders’ lines as far to the rear as the artillery positions. Fighting was so fierce in this area that one platoon of Company A was reduced to four men.25

It was here, too, that the soldiers of the 305th Infantry got their first taste of close-in combat on Guam. One finger of the Japanese penetration reached the hastily established lines of Companies A and B, and in the fighting that ensued seven Americans were killed and ten wounded in exchange for about twenty Japanese.26

On their part, the Japanese lost at least 268 men and 6 tanks during the counterattack.27 Among those killed was Colonel Suenaga who, after being wounded in the thigh by mortar fire, continued to lead the attack until he received a fatal bullet in the chest. Suenaga’s death deprived the Japanese defenders on Orote Peninsula of their commander. Command of the sector passed to Comdr. Asaichi Tamai, IJN, of the 263rd Air Unit, who took over not only the Navy forces stationed on Orote but also the 2nd Battalion, 38th Infantry, guarding the base of the peninsula.28

Consolidating the Southern Beachhead, 22-24 July

General Shepherd’s plan for 22 July contemplated an expansion of the beachhead in three directions – north, east, and south.

On the right (south), the 4th Marines was ordered to seize Mount Alifan and then push south along the ridge line toward Mount Taene. The 22nd Marines was to head in a northeasterly direction and capture an intermediate objective line that ran about 4,000 yards east of Pelagi Rock. The 305th Infantry (less 2nd Battalion) was ordered to pass through the left battalion of the 4th Marines and attack toward Maanot Pass, a cut through the mountains over which Harmon Road ran from Agat to the east. The 2nd Battalion, 305th, and 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines, were to be in brigade reserve.29

At the outset of the attack the 4th Marines ran into heavy enfilade fire from the reverse slopes of Alifan’s foothills. Once this was neutralized and the marines could approach the mountain itself, the chief deterrent to rapid progress was the terrain. Approaches to the crest were snarled with pandanus roots and led to vertical cliffs covered with thick scrub growth. Enemy resistance, however, was only nominal, and one patrol was able to reach Alifan’s summit, where it discovered no evidence of Japanese activity. The patrol then returned to the foot of the cliffs and joined the rest of the regiment.30

In the brigade center the 305th Infantry was slow in jumping off because of the many delays incurred in getting ashore the night before. Neither the 1st nor the 3rd Battalion had been able to get fully organized until about 0700; the regimental command post was not in a position to direct the attack until an hour later; the 305th Field Artillery was even longer in getting set to go into action. By 1000, however, all was in order and the regiment, with the 1st Battalion on the right, the 3rd Battalion on the left, passed through the left flank of the 4th Marines and launched its attack to capture the high ground over which Harmon Road passed to the east.31

During the morning the 305th encountered little resistance, and by 1252 the 3rd Battalion was already on the line that had been set as the day’s objective.32 That afternoon Chalgren’s men pushed ahead still farther but before night were pulled back to their 1300 positions in order to tie in with the 1st Battalion, which had made slower progress because of the dense underbrush that covered the hills over which it had had to advance. When the regiment dug in, its two forward battalions had firm contact, but a deep gully prevented physical contact with the 22nd Marines on the left.33

On the brigade left, the 22nd Marines pushed off at 0845, ahead of the other two regiments. Until late afternoon, it encountered only moderate resistance. The hill northeast of Agat that had held up the 1st Battalion the day before was easily mounted as tanks cleared the way to the next high ground. When the marines on the left reached the Ayuja River they were temporarily halted when it was discovered that the Agat road bridge across the river had been destroyed. The men were reluctant to ford the river without their supporting tanks, and the tanks could not cross because the river banks were too steep. In

4th Marines moves inland toward Mt. Alifan

the absence of engineers, amphibian tanks were called up to replace the tanks until provision could be made to get the latter across.

This substitution of armored amphibians for tanks was contrary to prevailing Marine Corps doctrine. Experience at Saipan had shown that amphibian tractors, armored or otherwise, were extremely vulnerable to enemy fire when out of the water.34 Hence, that afternoon General Shepherd sent clear orders to all the units under his command that the amphibians should not be used inland except where absolutely necessary.35

In any event, the troops made their way across Ayuja River, some of them reaching a point beyond the Old Agat Road before they were ordered back to the road itself to tie in for the night with the rest of the 22nd Regiment. Later, the 22nd Marine Tank Company, after twenty-four hours of labor, constructed a causeway across the river to enable its vehicles to cross over.

By nightfall the brigade, with the 305th Infantry attached, was drawn up along a line extending from the shore near Pelagi Rock, along the high ground northeast of Harmon Road, through Mount Alifan, southwest along the ridge line toward Mount Taene, then west to the sea at Magpo Point. The 4th Marines held this line from its coastal anchor at Magpo Point to Mount Alifan; the 305th Infantry held the area along the foothills northeast of Mount Alifan to a point about 1,200 yards from the Old Agat Road; and the 22nd Marines held the area north and northeast of Agat. Approximately 3,000

Assembly area of 305th Infantry on 22 July

yards of the Force Beachhead Line in the brigade’s zone was now in American hands.

It was clear by now that nothing was likely to impede the complete and rapid occupation of the southern beachhead, and, accordingly, General Geiger announced the second objective for the brigade – the capture of Orote Peninsula. Once the Force Beachhead Line had been fully occupied, the brigade was to be relieved by two regiments of the 77th Infantry Division, which would take over defense of the line from Inalas to Magpo Point. This task was to fall to the 305th Infantry, already ashore, and to Col. Aubrey D. Smith’s 306th Regimental Combat Team, which was still afloat. The 305th would be released from brigade control, and both regiments were to be under direct command of General Bruce. The 307th was ordered to remain afloat in corps reserve and be prepared to land anywhere on order.36

The night of 22-23 July in the brigade zone was one of relative quiet, disturbed only occasionally by Japanese patrols, whose efforts to infiltrate through the lines were uniformly unsuccessful. The next morning, and throughout the 23rd, the 4th Marines on the right (south) made no further effort to advance, but consolidated its positions and prepared to be relieved by the 306th Infantry. That these men were able to go about their preparations undisturbed was partly due to the fact that

naval guns and aircraft sealed off most of the possible routes of enemy counterattack. Early in the morning of the 23rd observers had spotted a large Japanese troop movement headed from Mount Lamlam toward Facpi Point. The call went out immediately for naval and air assistance, and in response the cruiser Honolulu, aided by carrier planes, dispersed the Japanese.37

For the other two regiments, the push toward the Force Beachhead Line was considerably facilitated by the landing of field and antiaircraft artillery. By the morning of 22 July, Brig. Gen. Pedro A. del Valle, USMC, had two thirds of the 155-mm. guns and howitzers of III Amphibious Corps Artillery ashore, and the 9th Marine Defense Battalion had succeeded in placing two dozen 40-mm. and 20-mm. guns and a dozen .50-caliber machine guns along the beach between Agat and Bangi Point.38 Late the same afternoon, Brig. Gen. Isaac Spalding, Commanding General, 77th Division Artillery, set up his command post inland of Gaan Point. By then the remainder of the 305th Field Artillery Battalion was ashore, as were two other artillery battalions, the 304th and 902nd. The 305th was ordered to continue to support the 305th Infantry; the 304th Field Artillery Battalion was assigned to close support of the 306th Infantry when it should get ashore; and the 902nd was given the mission of general support for the division. The 304th and 902nd Battalions were also ordered to be prepared to support the brigade in its forthcoming attack on Orote Peninsula.39

Meanwhile, on the 23rd the 305th Infantry had made rapid progress, hampered only by occasional enemy patrols. By 1130 the 3rd Battalion, on the left, had reached the O-2 line; the 1st was pushing from the Harmon Road along the ridge northeast of the Maanot Pass toward the O-2 line on the right of the 3rd. The 2nd Battalion moved to Maanot Pass to block the path of possible Japanese approach from the east along the Harmon Road. By early afternoon, as the 305th Infantry was digging in for the night in a deep salient along the O-2 line and the Force Beachhead Line, all of the high ground overlooking Orote Peninsula from the southeast was in American hands.40

To the left, the 22nd Marines moved more slowly in its northward thrust toward the base of Orote Peninsula. Little resistance was encountered on 23 July until midafternoon, but then, as the regiment attempted to swing across the narrow neck leading out onto the peninsula, the Japanese suddenly came to life. The southern approaches to the peninsula were guarded by marshy rice paddies interspersed with small hills that the Japanese had organized into a system of mutually supporting strongpoints. Moreover, the zone of the 22nd Marines approach was exposed to artillery and mortar fire from both Orote Peninsula on the west and Mount Tenjo to the northeast. The Japanese had not failed to make full use of these commanding positions. In spite of heavy concentration laid down by corps and division artillery, assisted by the big guns of the battleship Pennsylvania, the marines could do nothing to dislodge the enemy. After a

Smoldering Japanese tanks knocked out on Agat-Sumay Road by U.S. medium tanks

wasted, exasperating afternoon sloshing through the rice paddies, the regiment finally drew back a full 400 yards from its most advanced positions and dug in just south of the Old Agat Road.41

General Shepherd’s plan for action on the 24th contemplated a two-pronged movement, the object of which was to envelope the rice paddy area and establish a firm line across the narrow neck of Orote Peninsula. All three battalions of the 22nd Marines were to be committed to the attack. On the right, the 2nd Battalion was to jump off from its night positions south of the Old Agat Road, skirt to the right of the marshland, and push north to the town of Atantano, just inland of Apra Harbor. On the left, the other two battalions were to drive north up the coast along the Agat–Sumay Road in columns of battalions. Once the rear battalion had reached a point on the Agat–Sumay Road about 600 yards from its line of departure, it was to fan out to the right and then head north toward the south shore of Apra Harbor. The lead battalion would continue in a northeasterly direction along the Agat-Sumay Road. If this plan succeeded, nightfall would find the regiment drawn up across the neck of Orote Peninsula from the seacoast to Apra Harbor, with all three battalions abreast. Enemy defenses in the rice paddy area would be enveloped and presumably destroyed or neutralized. To relieve the 22nd Marines of the necessity of lengthening its already thinning lines, the 305th Infantry was ordered to shift left

maj. Gen. Andrew D. Bruce discussing operational plans with Col. Douglas McNair

as far as Old Agat Road, which was to be the new regimental boundary line.42

After delaying an hour to permit a longer preliminary naval bombardment, the regiment jumped off as ordered at 1000, 24 July. The battalion on the right, was counterattacked almost immediately and had to fall back to its previous night’s positions south of the Old Agat Road. By early afternoon, however, it regained the initiative and was quickly able to reach its objective at Atantano, where it established visual contact with the 305th Infantry on its right. The other two battalions found the going slower as they felt their way up the Agat–Sumay Road. The road was thickly mined with aerial bombs and subject to heavy enemy artillery fire from Pelagi Rock and Orote Peninsula. Five Japanese tanks appeared and contested the passage but were quickly disposed of by the heavier Shermans that were spearheading the drive. As planned, on reaching the point on the road where the ground to the right permitted a decent foothold, the rear battalion fanned out in that direction. Without too much difficulty it overran the strongpoints that had held up the regiment on the 23rd, but as evening approached and the battalion was compelled to dig in, it was still some 400 yards short of its objective on the south shore of Apra Harbor. Meanwhile, on the left, the lead battalion had succeeded in reaching its objective on the west coast of the narrow neck of Orote.43

Thus by the end of 24 July, General Shepherd’s major objectives had been achieved. The Force Beachhead Line had been captured and was now manned mostly by units of the 77th Division. Orote was sealed off and the time was at hand to launch the drive to capture this vital peninsula that pointed fingerlike into the ocean between the two landing beaches and would constitute a danger to each so long as it remained in enemy hands.

Landing the Reserves

General Geiger’s plan to commit the major portion of the 1st Provisional Marine

Brigade to the assault on Orote required that the 77th Division take over the duty of manning the Force Beachhead Line until the peninsula could be secured. Accordingly, he ordered the 305th Infantry to occupy the northern part of the line and the 306th to land and relieve the 4th Marines on the southern part.

Late in the afternoon of 22 July, Colonel Smith, commanding officer of the 306th, had come ashore with Col. Douglas C. McNair, 77th Division chief of staff, to reconnoiter the landing beaches and assembly areas. Next day the whole regiment made the damp journey from ship to shore. As in the case of the Army troops that had preceded them, the men had to wade in from the reef line carrying all their equipment. The 77th Division as a reserve unit had been assigned no LVTs and its DUKWs had to be reserved for cargo and light artillery. Division headquarters had tried to land the troops at low tide, but overloaded communications and other difficulties in procuring landing craft delayed the ship-to-shore movement until the tide was flooding. Vehicles had to be dragged by bulldozer from the reef to the beach, and most of them drowned out. Almost all of the radio sets, even those waterproofed, were ruined, and one tank disappeared altogether in a large shell hole.

As a result of the delays incident to this slow procedure, only the 3rd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Gordon T. Kimbrell, was ashore in time to make its way into the line that afternoon. This battalion, with Companies A and C attached, relieved the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, in its positions between Mount Alifan and Mount Taene where, after repulsing a small enemy attack, the Army battalion established its perimeters for the night. The other two battalions of the 306th stayed in their assembly areas.44

On the morning of 24 July Lt. Col. Charles F. Greene’s 2nd Battalion, 306th Infantry, completed the relief of the 4th Marines on the northern part of its line and established contact with the 305th Infantry on the left. Throughout the day Greene’s men cleaned out Japanese caves and dugouts in their area. No organized enemy appeared to contest their positions.45

General Bruce therefore requested permission to land two battalions of the 307th Infantry so that he could push the Force Beachhead Line still farther east and as far south as Facpi Point. General Geiger denied the request because he considered a further expansion unnecessary and also because he was loath at this time to part with all but one battalion of his corps reserve.46 Nevertheless, he conceded that the 307th should at least be landed in the area of the southern beachhead, although it was retained under the III Amphibious Corps command. Starting on the morning of 24 July, Col. Stephen S. Hamilton’s regiment commenced the uncomfortable trek from its transports to the beach – made even more arduous this time by an untimely storm at sea. By midafternoon, General Bruce himself was ashore at his command post and ready to take over direction of his two regiments on the line.47

Thus by the end of 24 July, after four days of fighting, the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade, with an assist from the 77th Infantry Division, had captured almost all the ground between the landing beaches and the Force Beachhead Line and had cut off from retreat and reinforcement the Japanese garrison on Orote Peninsula. The 305th and 306th Regimental Combat Teams had taken over all of the line except that section across the neck of Orote Peninsula, where the marines were poised to launch the next major assault. All of del Valle’s III Amphibious Corps Artillery was ashore, and most of the 77th Division Artillery was in position to support the advance. Beach defenses from Agat to Gaan Point were manned by the 9th Marine Defense Battalion, and from Gaan Point south to Bangi Point by the 7th Antiaircraft Artillery (Automatic Weapons) Battalion of the 77th Division. Firmly in American hands was a large irregular slice of Guam running from Magpo Point northeast to Mount Taene, north to Mount Alifan, and again northeast to Inalas, where it bent back northwestward to Atantano and then southwest across the neck of Orote Peninsula. Casualties up to the night of 24 July were 188 killed in action, 728 wounded, and 87 missing in the brigade; 24 killed in action, 63 wounded, and 1 missing in the Army division.48 This was a substantial price to pay, but the figures were not out of proportion when compared to those for most Central Pacific campaigns. Nor were the losses nearly so great as those being suffered at the same time by the 3rd Marine Division in its bitter fight for the northern beachhead.

Consolidating the Northern Beachhead, 22-24 July

Speaking of the terrain that faced the 3rd and 21st Regiments of the 3rd Marine Division just inland of their landing beaches, Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, commandant of the Marine Corps, later remarked that it was “some of the most rugged country I have ever seen.”49 Coming as it did from a veteran of Guadalcanal, this description conveys some idea of the nature of the problem facing the marines immediately upon their landing in this zone. Bundschu Ridge and Chonito Cliff were little more than a hundred feet in height, but rose precipitately from the narrow coastal plain beneath.50 Dense and tangled underbrush covered the approaches to the ridge, and the whole area was striated with deep ravines and gullies that made contact between the attacking units extremely difficult to maintain and at the same time offered ideal routes for Japanese infiltration. (See Map VI.)

On 22 July, while the 21st Marines reorganized, the 3rd Marines, on the left, assaulted Bundschu Ridge behind a heavy concentration of artillery and heavy weapons, supplemented by the 20-mm. and 40-mm. guns of the 14th Marine Defense Battalion. A few men reached the top, but only to return to their parent unit before the day’s close. By this time Colonel Hall’s 3rd Marines was a badly battered regiment. In two days fighting he had lost 615 men, and some of his companies were down to 30 or 40 men.51 On the next day he decided to pit his 1st and 2nd Battalions,

decimated as they were, against the ridge. To General Turnage he sent the message, “I am going to try and advance up that mess in front of me. What I really need is a battalion whereas I have only 160 men to use on that 500 yard slope.”52 To his great surprise, when his men finally hacked their way to the top on the morning of the 23rd, most of the Japanese had evacuated.

Still it was impossible to push on immediately. The cliffs were studded with machine guns that had to be mopped up, and contact had yet to be gained with the 21st Marines on the right. That regiment had made little progress during the day in the face of heavy opposition from enemy pillboxes. Colonel Hall asked for reinforcements from the 77th Division, whose 307th Regiment was still afloat, but General Geiger was unwilling to release his corps reserve.53

On the morning of 24 July, two battalions of the 21st Marines attacked up the ravine that lay between the 21st and the 3rd Marines to the left. From the cliffs on either side came murderous machine gun fire. On top of this, American naval pilots, called in to make an air strike, were forced to drop their bombs so close to the attacking line that seventeen marines were killed or wounded.54 That afternoon, two companies of the 3rd Marines coming up from the left were able at last to establish contact between the two regiments.

At the close of 24 July the left and center regiments of the 3rd Marine Division had, by dint of great effort and many casualties, succeeded at last in establishing a foothold on the first ridge line inland from the sea. Yet, though this victory was by no means a Pyrrhic one, neither could it be considered decisive. Ahead still lay a series of formidable ridges, running roughly parallel to the sea, each one higher than the one before, and all culminating in the mid-island mountain mass, which in this area was dominated by Mount Chachao, Mount Alutom, and Mount Tenjo.

Meanwhile, on the division right, the picture was not so discouraging. On 22 July the 9th Marines moved southwest along the ocean shore against light resistance and occupied Piti Navy Yard. Late the same afternoon a minor amphibious assault of battalion size was sent against Cabras Island. The landing was unopposed and uneventful except that one LVT hit a land mine. The next day the occupation of the island was completed. On the 24th the regiment sent out a patrol south along the Piti-Sumay Road in an attempt to establish contact with the brigade. Covered by amphibian tanks as they moved along the coastal road, the men eventually came under heavy machine gun fire from the inland cliffs, and this, coupled with the fact that they were approaching the edge of the pattern of American fire being directed against Orote, persuaded them to return. Contact between the division and the brigade would have to await another day.55

Initial Supply Over the Beaches

If the 3rd Marine Division suffered more severely than the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade from enemy fire and nightmarish terrain, it did enjoy one advantage over the troops to the south – the movement of supplies from ship to shore during the early days of the assault was more expeditious.

Pontoon barge with crane is a fueling station. Alligator is refueling from a barge inside the reef

Off the Asan beaches, the lagoon between the shore line and the reef’s edge was for the most part dry at low tide and trucks were able to drive to the edge and take on supplies directly from cargo boats and lighters. Off the Agat beaches, however, the abutting reef and the lagoon bottom were underwater at all times, and consequently all cargo had to be restaged to amphibious vehicles several hundred yards offshore. To add to the difficulty, the fringe of the reef was not pronounced, and therefore it was impossible to position cranes on the coral outcroppings as was done at Asan. As a substitute measure, the cranes at Agat were mounted on pontoon barges moored along the line where the shallow water began. Using this system, it was possible for the cargo boats to load LVTs at the rate of 25 tons an hour and DUKWs at the rate of 40 tons an hour.56 Another device employed to expedite unloading over the southern beaches was the construction of improvised pontoons made by lashing together two life rafts covered by a platform. Each attack transport of the Southern Transport Group was ordered to provide one of these “barges,” each of which had a capacity slightly in excess of one ton. LCVPs could lower their ramps over the floating platforms and transfer their supplies. The rafts could then be floated over the reef and in to shore.57

Notwithstanding these emergency measures, the brigade on 21-22 July suffered from a scarcity of supplies, especially ammunition. The main reason, aside from

the hydrographic difficulties described, was the shortage of amphibian vehicles. Thirteen of Shepherd’s LVTs had been knocked out by enemy gunfire during the ship-to-shore movement, and eleven more had been lost later on W Day. The poor roads ashore made it necessary to use a portion of the amphibian tractors to transport supplies directly to the front lines instead of just to the shore line as planned, thus reducing still further the number of amphibian vehicles available for ship-to-shore supply. The DUKWs, of course, took over part of the burden, but many of these during the first two days were occupied with the job of landing artillery pieces and could not be diverted to carrying cargo. Also, some of the DUKWs got mired in the silt that bordered the shore line and others had their tires punctured on sharp coral heads.58

Ashore, the movement of supplies inland was further impeded by the congestion resulting because of the narrow dispersal areas, especially on WHITE Beach 1. For the first two days infantrymen, artillery pieces and their crews, and the members of an LVT repair pool all crowded together in this restricted area, causing confusion and delay.

Admiral Conolly was quick to take cognizance of the shortages suffered by the brigade and ordered his transports to continue unloading throughout the night of 21–22 July and on until midnight of the 22nd.59 Thereafter, ships ceased loading from 2400 to 0530. In order to get supplies and equipment into the hands of the troops that needed them, the admiral was willing to keep his transports at anchor and partially lighted even at the risk of exposing them to enemy air and submarine attacks at night. Partly as a result of these measures, and in spite of the numerous obstacles involved, an average of about 5,000 tons a day was unloaded over the northern and southern beaches during the first eight days of the invasion.60

Blank page