Chapter 20: Guam Secured

By the evening of 4 August, General Geiger had concluded that the Japanese in northern Guam were falling back on Mount Santa Rosa, which is east of Yigo and a good six and a half miles northeast of Mount Barrigada. To deny the enemy enough time to complete his defenses in this area, Commander, III Amphibious Corps, directed his forces to chase and close with the Japanese as rapidly as possible.1

77th Division: 5-6 August

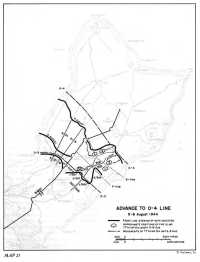

The 77th Division plan for 5 August called for the 306th Infantry to replace the 307th on the division left and the 305th Infantry to continue its push to the northeast, sending at least one battalion to the O-4 line, which crossed the island about a mile south of Yigo. The 307th Infantry was to complete the advance to positions assigned the day before and then go into division reserve until its men were sufficiently rested.2 (Map 25.)

On the division right, Colonel Tanzola’s 305th Infantry floundered ahead through the heavy jungle, the individual units having little or no idea of their actual positions. The only means the troops had of obtaining their approximate positions was by shooting flares and, by prearrangement, having their supporting artillery triangulate on the flares. Then the artillerymen would plot the position of the flares on their maps and radio the information to the infantry. The lost and weary soldiers moved slowly through the dense jungle, following thin, winding trails or hacking their way through the thick vegetation. Only an occasional Japanese was encountered, and the jungle as usual proved the great obstacle to the advance. The two forward battalions, 2nd Battalion in front of the 1st by more than 1,000 yards, moved in column through the undergrowth and quickly lost themselves in the vegetation. Unable to see more than a short distance around them, each unit was unaware of its location and could not orient itself on the relatively flat terrain nor find its position on the inadequate maps available. Even regimental headquarters was apparently ignorant of the location of subordinate units, nor could artillery spotter planes locate the troops. Late in the morning the 2nd Battalion was reported to have reached G line, an advance of about 1,100 yards, and by the middle of the afternoon the battalion thought it had reached the O-4 line, about 2,000 yards farther ahead. The 1st Battalion was thought to be 1,000 or 2,000 yards behind the 2nd. The positions

Map 25: Advance to O-4 line, 5-6 August 1944

were no more than guesses. Indeed, the 2nd Battalion began cutting a trail to the coast on a 90° azimuth in an attempt to make an exact determination of its position. At nightfall the map location of the two battalions was still in doubt. They were somewhere east-northeast of the F line, with the 2nd Battalion apparently still in the lead. Regimental headquarters and the 3rd Battalion were apparently somewhere along the eastern portion of either the O – 3 line or the F line.

Heavy rainfall during the late afternoon and evening of 5 August increased the discomfort of the troops. The downpour stopped around midnight, but the night was still dark and overcast. Shortly before 0200, men of Company A, holding the northern portion of the 1st Battalion perimeter, heard the noise of approaching tanks and infantry. American tanks were reportedly in the neighborhood, and the troops assumed that the force they heard was a friendly one moving back from the 2nd Battalion. The men in their foxholes kept careful watch, however, and as the full moon came from behind a cloud the Americans saw revealed in its light two Japanese tanks and an estimated platoon of enemy infantry setting up machine guns.

Company A opened fire at once and silenced the Japanese infantry, but the two tanks drove against the line of the perimeter. One cut to the right off the trail, the other to the left, then both drove into the perimeter away from the trail which the 1st Battalion was astraddle. Firing their weapons as they came, the Japanese tanks broke through the defenders and pushed through the perimeter. Once inside, one of the vehicles stopped and threw a stream of fire around the area while the other drove farther on. A platoon of American tanks from C Company, 706th Tank Battalion, attached to the 1st Battalion, could not fire for fear of hitting the American infantry.

The enemy infantry outside the battalion perimeter had been killed or driven off, but inside the perimeter the Japanese tanks continued to raise havoc. The tank that circled inside the area probably did the most damage as men struggled to escape from its path or threw ineffective small arms fire at its steel sides. Bazooka men were so excited that they neglected to pull the safety pins in their ammunition. Soon the two tanks rejoined and doubled back to the north again through A Company’s perimeter. As they left the area a last defiant rifle shot killed a Japanese soldier who had ridden one of the tanks through the entire action.

Behind them the tanks left a trail of ruin. Equipment was smashed or bullet-riddled; one or two jeeps were badly crushed, and the area was a shambles. All six enlisted men in an artillery observation party were either killed or wounded and the officer observer was injured. Casualties in the 1st Battalion, mainly in Company A, were heavy. A total of forty-six men were wounded, of whom thirty-three had to be evacuated; fifteen were killed. The Japanese tanks escaped unscathed, although the losses among the enemy infantry, caught in the first burst of A Company’s fire, were probably high.

On the next morning (6 August) the 305th Infantry continued in its attempt to reach the O-4 line. Its 3rd Battalion was kept in force reserve in accordance with corps and division plans for pushing the pursuit to the northeast, but the remaining two battalions were able to drive for the

O-4 line. Neither the 1st nor the 2nd Battalion knew its exact position.

The 2nd Battalion had found and was following a tiny path near the coast that led into “impenetrable jungle” so thick that “a man cannot even step off a trail without cutting.”3 To avoid following this path, the battalion attempted to work to the northwest, and General Bruce gave his permission for the unit to move out of the regimental zone and into the area of the 306th Infantry, if this proved necessary. As the battalion advanced along a narrow trail in a thin column of companies, the lead scout suddenly came face to face with an enemy soldier. The American sent back a warning to the rest of the column, while simultaneously the Japanese shouted the alert to his own unit, the same tank-infantry force that had the night before attacked the 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, with such success.

The chance meeting started a fierce fire fight. The initial advantage was with the Japanese, for the two enemy tanks were in hull defilade, their 57-mm. cannon and machine guns covering the trail, while the American infantrymen were strung out along the narrow trail in an exposed position. The advantage was ably exploited by the enemy. His machine gun fire raked the trail while shells burst in the trees and sent punishing fragments into the column of American troops. Company E, the lead unit, hastily deployed on both sides of the trail, but the same rise in ground that gave hull defilade to the enemy armor prevented the Americans from locating the Japanese riflemen supporting the two tanks.

The intense enemy fire brought down a number of Americans. Medics attempted to move forward to aid the wounded, and the supporting platoon of mediums of Company C, 706th Tank Battalion, advanced up the trail to hit the enemy. The lead American tank halted, and riflemen formed a skirmish line on either side of it. Heavy machine guns of H Company were brought up next to the tank, but sweeping Japanese fire put these guns out of action before they could fire more than a few bursts. The enemy fire, especially the tree bursts from which there seemed no defense and no protection, soon began to drive the riflemen back from around the tank. The driver of the Sherman, fearing to be left alone, reversed his course and in so doing almost precipitated a panic in the entire American line. However, the battalion executive officer, Capt. Charles T. Hillman, with the aid of a sergeant from H Company, began to rally the troops. Both men were wounded, Hillman fatally, but by their efforts troops of the 2nd Battalion were able to form a line just a few yards behind the first American position.

To the American rear, meanwhile, other soldiers were attempting to put the 81-mm. mortars into operation. Tree bursts and continued enemy machine gun fire made this dangerous and difficult, and the heavy jungle overhead made it equally dangerous to attempt to fire the mortars. One piece finally got into action, however, and began lobbing a steady barrage of shells at the Japanese position.

Once the mortar was in action the enemy was finished. Japanese fire began to slacken and then suddenly ceased. Squads of American infantry that had moved out on flanking maneuvers on either side of

the trail closed in on the enemy position without opposition. They found the two Japanese tanks deserted and three dead Japanese.

Most of the Japanese riflemen of this particular tank-infantry team had apparently been killed during the fight with the 1st Battalion the night before. The tanks and few remaining infantrymen would seem to have been attempting to regain their own lines when they encountered the 2nd Battalion. Outnumbered, and eventually outgunned, the Japanese had rendered a good account of themselves in the short battle. Casualties on the American side were not as heavy as might have been expected, for only four Americans were killed, but at least fourteen, possibly as many as thirty, were wounded.

Other than this fight, the daylight hours of 6 August witnessed no serious engagements in the 305th Infantry area. A few scattered Japanese were encountered but, as on the previous day, the main enemy force was still the jungle to the north. Both battalions continued to have difficulty threading their way through the heavy vegetation, and both were still unsure of their exact positions. The 1st Battalion, which did not have to retrace its steps, appears to have done less wandering and to have moved rapidly forward northeast in the left half of the regimental zone. Shortly after noon, advance elements were on the O-4 line and in contact with men of the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, on the left. By midafternoon the entire 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, was on the objective line. The 2nd Battalion was also moving forward with a clearer knowledge of its location and by dusk, at the latest, it too was on the O-4 line. Its wanderings had brought it to the right of the regimental sector, and it dug in on the right (southeast) of the 1st Battalion.

While the 1st and 2nd Battalions had been advancing to the O-4 line on 6 August, regimental headquarters and the 3rd Battalion, in force reserve, had moved to positions on the F line. An attached platoon of the 77th Reconnaissance Troop continued to patrol the open right flank of the 305th Infantry down to the sea. It discovered evidence of enemy patrols in the area, and in a brief encounter with a small Japanese force in midafternoon killed one soldier. One of the enemy patrols that eluded the American patrol, or perhaps some Japanese stragglers from elsewhere in the jungled 305th Infantry area, got as far as the regimental command post before two were killed and the others driven off.

On 5 and 6 August the 305th Infantry had thrashed its way through the heavy Guam jungle, across poorly mapped and unfamiliar terrain, and against sporadic, but on two occasions punishing, Japanese resistance, to positions along the O-4 line. The regiment suffered nearly a hundred men wounded on the two days, and about twenty-five killed. The regiment estimated that it had killed about a hundred Japanese and had knocked out the two enemy tanks that had invaded the regimental zone of action.4

To the left, the movement of the 306th Infantry around the right flank and in front of the 307th Infantry was impeded more by the thick vegetation and poor trails and the lack of decent maps than by the Japanese opposition. The maneuver would have been arduous under any circumstances, because of the complicated trail net that involved several 90° turns. It was so difficult to keep track of the units within the regiment that a division artillery liaison plane was called on to spot infantry positions.

Colonel Smith’s regiment began its move at 0630 on 5 August in a column of battalions, the 1st in the lead, followed by the 3rd. It advanced generally unopposed along a trail from the Barrigada area past the east side of Mount Barrigada. By noon the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, had reached the trail running east from Finegayan that had marked the 307th Infantry’s objective line the previous day. Moving eastward along the trail, the men reached another trail that led north to a juncture with the coral road that ran from Finegayan east-northeast to Yigo. As the 1st Battalion turned north toward the Finegayan–Yigo road shortly after noon, it began to run into a few scattered enemy riflemen. Lt. Col. Joseph A. Remus’ men advanced north along the trail against increasing Japanese opposition, and by the time they reached the Yigo road shortly after 1400 the resistance had become quite strong.

The enemy consisted for the most part of individual riflemen and machine gun positions. The Japanese astride the road itself were driven off without too much difficulty, but these or other enemy soldiers filtered through the jungle and struck the flank of Company A, which was leading the battalion advance. The assault, while thrust home with vigor, was not made in great force, and the Americans were able to drive off the enemy as tanks came up to help complete the job. The entire action along the Yigo road took more than two hours before the enemy was finally destroyed or driven off. Company A had been supported by the battalion’s 81-mm. mortars and by a platoon of B Company, 706th Tank Battalion, as well as by the artillery. It had killed nearly a score of Japanese while the company itself had lost one man killed and seven wounded.

It was about 1630 before the 1st Battalion could pick up the advance again. Unable to find Road Junction 363, forward elements pushed west a few hundred yards beyond where their map showed the junction to be and then fell back to night positions at a point about where the battalion had first hit Yigo road. The 3rd Battalion, meanwhile, had turned east according to plan when it reached the Yigo road in midafternoon. Encountering scattered light resistance, Colonel Kimbrell’s troops were able to move only a few hundred yards east along the road and northeast into the jungle before halting for the night.

The day’s advance was not sufficient for the 306th Infantry to make contact with the marines, who were still about 1,000 yards to the west of the 1st Battalion. That night, during a heavy rainfall, the Japanese made several attempts to infiltrate the perimeter, but all were beaten back.5

Shortly after 0700 on 6 August the 306th Infantry, according to orders, pushed off again. The 1st Battalion started west on the Finegayan–Yigo road in search of Road Junction 363 and the trail north. The battalion moved slowly, apparently against light opposition. With the aid of an artillery spotter plane it was able to locate the road junction, which it reached shortly after 0900. The trail to the north led through heavy jungle and was evidently not very wide or clear. The battalion turned north to follow it, sending a patrol of company size farther west along the Finegayan–Yigo road in an attempt to make contact with a Marine patrol pushing east along the road. Slowly northward the soldiers pushed, cutting through the thick vegetation that bordered and overgrew the trail. By about 0930 they had encountered a Japanese force about 150 to 200 yards north of Road Junction 363. Company B, leading the advance, engaged the enemy, taking a few casualties. Tanks and supporting weapons were then brought up to drive the rest of the Japanese off.

Continuing in the same direction, Remus’ battalion encountered little or no enemy opposition, but by about 1330, when the troops were still roughly half a mile from the division boundary, the trail gave out. From here on the men had to cut their way through the heavy jungle, packing coral limestone down so that vehicles could follow the advance. By 1700 the battalion had reached the division boundary on G line. When the men dug in for the night their perimeter was but 300 yards from that of the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marines, and contact, either visual or by patrol, had been established.

Meanwhile, the company of the 1st Battalion that had continued to push west along the Finegayan-Yigo road had moved easily against little or no resistance during the morning. By about 1100 the Army patrol had met a similar Marine patrol that had pushed east from Marine lines, thus establishing contact about 400 yards west of Road Junction 363.

While the 1st Battalion was pushing north and west, the 3rd Battalion drove east along the Finegayan-Yigo road. Kimbrell’s men had moved about 1,000 yards up the road from their morning position on G line when, shortly after 0800, the lead scout of I Company noticed the muzzle of an enemy 47-mm. gun in the bushes ahead of him. The infantry column halted and deployed as quietly as possible while a platoon of Shermans of B Company, 706th Tank Battalion, moved up. The enemy position was well camouflaged and the lead American tank discovered it was facing a Japanese medium tank at about the same time that the enemy vehicle opened fire. The first round flattened a bogie wheel on the American tank, but answering fire from the 75-mm. gun on the Sherman was much more effective. Three rounds set the Japanese tank aflame, and the Sherman’s machine guns and a quick rush by the American infantry took care of the enemy soldiers around the Japanese tank. Nearly a score of Japanese were killed with no American losses.

With the enemy ambush thus effectively demolished, the 3rd Battalion picked up the advance again. By about 1000 it had reached Road Junction 385, just 400 yards from the O-4 line, and within half an hour the men had crossed the objective line and were reported by an air observer to be only about 1,200 yards from Yigo itself. Since an advance up Yigo road by only the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, would have

exposed the unit to flank attack and disturbed division plans for the next day, the battalion was called back to the O-4 line. Darkness found the 3rd Battalion dug in in its assigned position and in contact with the 305th Infantry to its right (southeast).

Thus, on 6 August, the 306th Infantry completed its mission by gaining the O-4 line and establishing contact with the marines. Moreover, Yigo road was now open as far as the O-4 line. Casualties in the regiment on the 6th were two killed and fourteen wounded, mostly in the 1st Battalion. One additional casualty occurred in midafternoon when Col. Douglas McNair, chief of staff of the 77th Division, was fatally wounded by an enemy rifleman while reconnoitering for a new division command post about 600 yards east of Road Junction 363. McNair had gone forward accompanied by an officer from the Reconnaissance Troop armed with a carbine, a sergeant armed with a BAR, and an escort of two light tanks. The party suddenly came upon a small shack almost concealed in the brush and the men thought they detected movement inside. “Spray it, Sergeant,” said the Colonel, and the sergeant peppered the shack. But one shot was fired in retaliation and it caught McNair in the chest. He died almost instantly. One of the tanks then rushed forward and demolished the shack and burned it. In the ruins were the bodies of three Japanese soldiers.6

Meanwhile, on 5 August, the 307th Infantry had rested and reorganized. The regiment moved forward only a few hundred yards, and so did not reach the O-3 line. Patrols from the 1st Battalion established contact with the marines at the division boundary on the trail east of Finegayan that had been the regimental objective on 4 August. However, this point of contact was still 2,100 yards behind the 3rd Division’s right flank, which hung in the air.7

The next morning, as planned, the men of the 307th pushed off again to the rear of the 306th, with the intention of giving General Bruce a three-regiment front before nightfall. Moving slowly in a column of battalions, 3rd leading with 1st close behind it and 2nd bringing up the rear, the 307th Infantry followed the same route that the 306th had taken. The rain of the previous night had left the trail muddy and the men sank ankle-deep into the ooze. The jungle continued to hamper off-trail movement. These two factors, combined with the fact that the 307th Infantry had to wait until all elements of the 306th had passed it, made the going slow.

By noon of the 6th the 307th Infantry had reached the trail junction that gave access to the trail leading north to Yigo road. Shortly thereafter, with all 306th Infantry elements passed, Colonel Manuel’s regiment continued its advance, going

north to Yigo road and then turning east to follow the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, along this main route. By midafternoon the lead battalion of the 307th Infantry – the 3rd – had reached the O-4 line and had tied in with 306th Infantry troops already there. The other units followed, and by nightfall the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, was on the O-4 line between the 306th and 305th Infantry Regiments, with the 2nd Battalion and regimental headquarters on the Yigo road 800 yards to the rear and the 1st Battalion on the road another 800 yards farther back.8 The 77th Division now had three regiments on the line. In conformance with plans already issued for the continuation of the attack, General Bruce could throw his entire division (less 3rd Battalion, 305th Infantry, which was in force reserve) into the assault.

3rd Marine Division, 5-6 August

Meanwhile, on the corps left, the 3rd Marine Division, attacking on a three-regiment front, was groping its way through jungle just about as thick as that slowing the progress of the Army troops. On the division left and center the 3rd and 21st Marines met no organized resistance on 5 August, but on the right the 9th Marines fought hard to clear the remaining Japanese out of the Finegayan area and open Road Junction 177 to permit supplies to move north toward forward dumps at Dededo.

On the 6th the same general pattern was repeated. The two regiments on the west gained as much as 5,000 yards against only nominal opposition. The 9th Marines, pushing north from Finegayan, succeeded in keeping abreast of the rest of the division, though it continued to meet scattered resistance and had to dispose of 700 Japanese defenders in the Finegayan area in the process.9

During this movement General Turnage approached the ever worrisome problem of unit contact in much the same manner as had General Bruce. In view of the tremendous difficulties involved in maintaining continuous physical contact in the nightmarish jungles of northern Guam, Turnage ordered his regimental commanders to advance in column along the trails. Patrols were to fan out 200 yards on either side of the trails to wipe out enemy troops that might possibly be lurking in the underbrush, but physical contact was to be established only at indicated points where lateral roads or cleared spaces made it feasible.10

Capture of Mount Santa Rosa, 7-8 August

By the close of 6 August the final defensive line that General Obata had tried to set up across northern Guam had been pierced and overrun in so many places that it constituted no line at all. Only isolated pockets of Japanese remained to contest the American advance, and these were without adequate weapons, out of touch with higher headquarters, and often virtually leaderless. The Japanese, like their attackers, were harassed and obstructed by the jungle that surrounded them. As

Mt. Santa Rosa, taken by the 307th Infantry on 8 August

Colonel Takeda later reported, “They were obliged to fight in the jungle where it was very hard to cooperate and communicate with each other. Therefore they could not fight satisfactorily to show their whole strength. And as the American armored troops drove along the highways and trails in jungle to cut off the front line into several pockets, our troops were forced to be isolated.”11 So much for the supposed inherent superiority of the Japanese in jungle warfare.

With less than one third of Guam still remaining in Japanese hands, General Geiger issued orders to complete the destruction of the enemy on the island. These orders – ready since the morning of 5 August, but not made effective until the afternoon of the 6th – called for an all-out attack on the morning of 7 August. Geiger planned to put almost his entire force into the final assault, holding out only one battalion from each division as force reserve. The 77th Division would make the main effort, seizing Mount Santa Rosa and the northeastern portion of the island. On its left and supporting it, the 3rd Marine Division would drive northeast to the sea. Finally, on the far left would come the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade, protecting the 3rd Division flank and securing the northernmost tip of the island by patrols. The corps commander stressed the necessity for maintaining contact between units, since the Japanese might well mount a last desperate counterattack to spring the crushing American trap. With the Army troops making the main offensive effort, General Geiger for the first time directed that responsibility for maintaining contact would be from left to right – the 1st Brigade would be responsible for maintaining contact with the 3rd Division, and the 3rd Division would be charged with keeping touch with the 77th. Warships and aircraft – P-47’s and B-26’s from Saipan – had been softening up Mount Santa Rosa for several days, and the bombardment, reinforced by corps and division artillery fire, would continue on the day of the attack. The corps assault plan was to go into effect at 0730, 7 August.12

The corps plan of attack did not reach General Bruce until the late afternoon of 5 August, but in anticipation the 77th Division

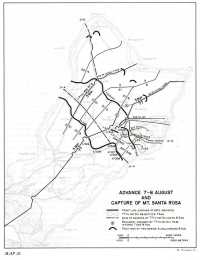

staff had already worked out a scheme of assault to be put into action once the O-4 line was secured.13 Distributed and explained to subordinate units shortly before noon of the 5th, the division plan fitted in well with the over-all corps scheme.14 (Map 26.)

General Bruce’s plan of attack – including modifications worked out up to the morning of 7 August – called for a wheeling maneuver on the part of his division, three regiments in line pivoting on their right. The object of the attack was Mount Santa Rosa, a height of nearly 900 feet, in front of the 77th Division. When the wheeling maneuver was completed, Bruce’s regiments would have surrounded the mountain on three sides – south, west, and north – pinning the Japanese defenders against the sea.

On the left of the division attack was the 306th Infantry with an attached company of Shermans of the 706th Tank Battalion. The 306th was to advance along the division’s left boundary until it had passed Mount Santa Rosa and then swing east to seize an objective area north of the mountain from the town of Lulog seaward to Anao on the coast. Patrols from this regiment would push northeast above the main body to the coast farther north. Since the 306th Infantry had to cover far more ground than either of the other two regiments, it would advance without regard to contact in order to accomplish its mission. On the right of the 306th was the 307th Infantry. For its action in the fairly open, rolling terrain around Yigo, the regiment had a company of medium tanks attached and the 706th Tank Battalion (less two companies) in support. The 307th would continue to attack up the Finegayan-Yigo road to capture Yigo and then swing east and northeast to block the western side of Mount Santa Rosa. In order to hold these gains and prevent any enemy escape, the 307th was authorized to commit all three of its battalions without maintaining a reserve. On the division right the 305th Infantry (less 3rd Battalion in force reserve) had only a short distance to cover in its move to seal the southern approaches to Mount Santa Rosa and support the 307th Infantry. In spite of this advantage the regiment was handicapped by having only two of its battalions in the assault and also in having no tanks attached.

The line of departure for the 77th Division was from 400 yards to a mile in front of the 306th and 307th Infantry positions on the O-4 line, with the shortest distance between the two lines on the left, in front of the 306th. The 305th Infantry, with only a small area to cover, would attack from the O-4 line. The 306th and 307th Regiments would begin the advance to the line of departure at 0730; the 305th would remain in position until ordered forward. The 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, would start for the line of departure half an hour early, at 0700. This battalion had not reached the O-4 line on 6 August, but had halted on the G line, a good 2,000 yards from the O-4 line. The extra half hour was apparently to enable the 1st Battalion to move abreast of the 3rd.

H Hour, the time of the general division attack from the line of departure, was set tentatively by General Bruce at

Map 26: Advance 7-8 August and capture of Mt. Santa Rosa

approximately 1200. The 77th Division assault was to be supported by a tremendously heavy air, artillery, and naval gunfire preparation. For an hour, beginning at 0900, P47’s and B-26’s would bomb and strafe Mount Santa Rosa. Twenty minutes before H Hour division artillery reinforced by corps artillery would begin a barrage lasting until the attack began. All four battalions of division artillery were to fire a round per gun per minute, all concentrations to fall in the zone of action of the 306th and 307th Infantry Regiments. At the same time that the artillery preparation began, a one-hour naval bombardment of the Mount Santa Rosa area would start, with the warships firing from south to north and moving their fire beyond the area immediately in front of the infantry by H Hour. After H Hour division artillery, supported by the corps weapons, was available on call. The immense air, artillery, and naval gunfire preparation, it was hoped, would leave the Japanese defending the Mount Santa Rosa area too weakened or dazed to put up more than a feeble resistance against the 77th Division attack.15

The turning maneuver planned for the 77th Division was a difficult one to carry out. Its execution was made even harder by a misunderstanding on the part of Bruce’s staff as to the precise location of the boundary between the Army and Marine divisions. Tentative division plans worked out before the receipt of General Geiger’s orders used the operational boundaries between the 3rd and 77th Divisions prescribed by corps on 2 August. The boundary then established ran along a road that branched off to the northeast from the main Finegayan-Yigo road at Liguan, passed Mount Mataguac, and ended at the junction with Yigo–Chaguian road about 2,000 yards north of the mountain. Since corps had not projected the boundary beyond the end of Liguan road, the 77th Division staff on its own initiative extended the boundary line to the northeast – from the road junction cross-country to Salisbury and thence along the Salisbury–Piti Point Road to the coast.16 Unless corps called for a change in operational boundaries, this line would stand. Unfortunately for those concerned, a boundary change is precisely what was directed by General Geiger.

The new operational boundary established by corps on 5 August was, beyond the town of Salisbury, exactly as 77th Division planners had assumed; along the road running from that town to the coast. While the Army was responsible for the road, it was to be used jointly by soldiers and marines. In an apparent effort to make as much of this road as possible available to the 3rd Division, however, General Geiger shifted the interdivisional boundary below Salisbury eastward to a line that ran from a crossroads southwest of Mount Mataguac to a point on Yigo–Salisbury road midway between the two towns, and from there along the road to Salisbury. Thus a large diamond-shaped area, about two miles long, between Mount Mataguac

and Salisbury was transferred from the 77th Division to the 3rd Marine Division.

That a new boundary had been drawn was made explicit in the III Amphibious Corps order that the 77th Division received on the afternoon of 5 August. “Boundary,” read the order, “between 77th and 3rd Mar Div changes ... ,” and then proceeded to describe the new boundary. The boundary was described again further on in the order when a reference was made to use of the Salisbury road. While no overlay accompanied the order, the map coordinates, repeated twice, and the use of the word “change” made it quite clear that a new boundary had been established.17

Nevertheless, when the 77th Division field order and final overlay for the 7 August attack were drawn up on the afternoon of the 6th, the original boundary line was incorporated in both the order and the overlay.18 The zone of action of the 306th Infantry, making its sweep around Mount Santa Rosa on the division left, was therefore partially within the 3rd Marine Division’s operational area.

Promptly at 0700 on 7 August the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, began advancing along the Liguan trail toward the line of departure. At 0730 the 3rd Battalion, on its right, began to advance cross-country, the 2nd Battalion remaining in its reserve position.19 In the 307th zone, in the center of the division, that regiment’s 3rd Battalion led the way along the Yigo road on schedule, with the 1st and 2nd Battalions prepared to follow.20 The two battalions of the 305th Infantry on the O-4 line stood by in position.21

By 0900 or a few minutes thereafter, just as American aircraft began pummeling Mount Santa Rosa, the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 307th, had reached the line of departure. The 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, advancing overland between them, did not reach the line until 1000.22 The 305th Infantry, meanwhile, had asked and received permission at 0905 to begin moving its 2nd Battalion forward from the O-4 line. Ten minutes later, with a bulldozer cutting the way through the thick jungle, the 2nd Battalion moved out to start the regimental advance.23

The first resistance of the day was encountered by the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, as it moved up Yigo road just before it reached the line of departure. As the battalion began fanning out to occupy a line about 800 to 1,000 yards below Yigo, it received enemy rifle and machine gun fire from concealed positions in the woods ahead. About 0840 the first Japanese fire struck Capt. William B. Cooper’s Company I, which was leading the advance. In the face of the enemy fire, it was almost 0930 before I Company could deploy along the line and begin to advance against the Japanese positions. The other companies had bunched up on the road, making it

difficult for the entire battalion to deploy and for the attached tanks of Company A, 706th Tank Battalion, to move forward. Nevertheless, once I Company had formed, it began to push back the enemy. By shortly after 1000 some of the Japanese had been killed and the rest were falling back. The Americans had suffered eleven casualties, but the 2nd Battalion was on the line and ready to push off.24

With all his attack battalions on the line of departure and the other units moving forward behind them, General Bruce was able to set H Hour definitely at 1200. Division units and corps headquarters were notified accordingly.25

The artillery preparation began promptly at 1138 – General Bruce had advanced the time by two minutes26 – with the three 105-mm. howitzer battalions of division artillery opening fire on targets in front of the 306th and 307th Infantry Regiments. At 1148 the shelling stopped for two minutes and then at 1150 all four battalions of division artillery and the three 155-mm. battalions of corps artillery delivered a heavy ten-minute preparation.27 To add to the weight of metal falling on enemy positions on the forward slope and atop Mount Santa Rosa, naval gunfire support vessels were also sending their big shells crashing inland. Meanwhile, the infantry and tanks made ready to attack.

The major opposition to the day’s advance of the 77th Division was to come in the center of the 307th Infantry zone of operations. Here, a tank-infantry assault had been planned to take advantage of the relatively open terrain around Yigo. The 706th Tank Battalion (less Companies A and B) was to spearhead this assault as soon as the artillery fire lifted at 1200. At that time the light tanks of Company D were to push up the Yigo road as fast as possible and enter the town with C Company’s mediums right behind them. The infantry was to act in close support of the armor, with the medium tanks of Company A, attached to the 307th, providing general support. Once Yigo was seized, the two companies of the 706th Tank Battalion were to occupy the high ground east-northeast of the town, thus opening the way for the 307th Infantry to swing against the western slopes of Mount Santa Rosa.28

Coordination between the 706th Tank Battalion and the 307th Infantry was something less than satisfactory. While the plan for the use of the tanks had been worked out late on 6 August, it was then too early to set the time of H Hour. At 0700 on 7 August the tank battalion (less A and B Companies) began moving from its assembly area to positions behind the 307th Infantry, prepared to move into the line as soon as H Hour was announced. At 1040 General Bruce sent word to the 706th that H Hour would be at noon, but the message never reached Colonel Stokes, the tank commander. Not until 1145 did Stokes get word to report to the 307th Infantry command post and not until his arrival, nearly ten minutes later, did he

learn the attack was scheduled to commence at 1200.29

With only a few minutes to go before H Hour, the two companies of tanks scheduled to spearhead the attack were still some distance behind the line of departure. At 1155 Stokes radioed Company D, which was to have led the drive, to move up and carry out the plan of action.30 Meanwhile, the officers of the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, poised on the line of departure to follow the tanks, had been growing anxious about the failure of the armor to appear. The battalion commander had orders to follow closely on the heels of the artillery. At 1156 the barrage was falling at a good distance from the line of departure and the infantry commander informed the regimental command post that he was about to move out. Without the tanks, then, at H Hour minus 3 minutes the 3rd Battalion crossed the line of departure and began advancing on Yigo.31

As the light tanks of Company D pushed hastily forward on Yigo road, they found their way blocked by the confusion of men and vehicles before them. Unable to move through the thick jungle on either side of the road, the tanks had to make their way between soldiers, vehicles, and the company of medium tanks attached to the 307th Infantry. It was thus 1207 before D Company reached the rear of the 3rd Battalion, and nearly 1220 before the tanks could pass through the leading infantry and begin to fan out in the more open terrain. The advance by this time had covered about 250 yards from the line of departure without resistance. However, less than 500 yards from the edge of Yigo, the Americans began to meet rifle fire from enemy troops driven south from the town by the volume of the preattack artillery preparation.32

Japanese small arms fire increased in intensity as the light tanks of D Company echeloned to the right, and the mediums of C Company moved up along the road behind them. The light tanks overran or pushed by several dugouts and pillboxes, leaving them for the infantry to clean out. Just short of the southern edge of Yigo, D Company swept across a slight rise of ground east of the road and began to receive fire of a heavier caliber from enemy positions concealed in the woods along and west of the road. It was apparent that the Japanese here had weapons too heavy for the light tanks, and a call went back for the mediums. Just as Company C reached the area, the Japanese succeeded in stopping the light tank farthest to the left. A few minutes later a second light tank was knocked out.

The enemy troops were well concealed in the woods to the left, and it was not until its mediums began to receive fire that C Company could determine the location of the Japanese positions. The mediums swung to put fire on the Japanese before following D Company on toward Yigo, but two of C Company’s tanks were also knocked out by enemy fire. As the two companies of the 706th began to push into the shell-flattened town, the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, attacked the Japanese positions along and west of the road. The infantrymen advanced cautiously into the woods, using rifles, machine guns, and

grenades. It was slow work, and at 1330 the troops still had not cleaned out the area. The tanks, with their mission to push through Yigo, had reorganized and were entering the town in force. The attached medium tanks of the 307th were still back with the rest of the regiment, and the task of destroying the enemy defenses was left to Major Lovell’s battalion.

Suddenly, unexpected assistance appeared from the west. The 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, advancing on the west flank of the 307th had heard the firing below Yigo, and Colonel Kimbrell, battalion commander, had taken a platoon of K Company to investigate. The Japanese had neglected to protect their rear and the K Company platoon caught them completely unawares, killing those enemy troops that had not been disposed of by the 3rd Battalion, 307th. Other elements of K Company, 306th Infantry, struck enemy positions in the woods farther north, and the entire area south of Yigo was soon cleared.

The Japanese position had been a strong one, built around two light tanks with a 37-mm. or 47-mm. antitank gun between them. In addition, the enemy had been equipped with two 20-mm. antitank rifles and six light and two heavy machine guns. No report on Japanese casualties is available, but undoubtedly they were heavy. There were probably a score of casualties in the 3rd Battalion,33 while the 706th Tank Battalion reported two killed, ten wounded, and one man missing.

By 1408 the leading elements of the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, were at the southern edge of Yigo, while the two companies of the 706th Tank Battalion had reached Road Junction 415, some 250 yards farther up the road at the northern edge of Yigo. A quarter of an hour later the tanks reported Yigo clear of Japanese, and the 307th Infantry commander ordered his 3rd Battalion to press through the town. By 1450 Yigo was secured, the 3rd Battalion had reached Road Junction 415, and the two tank companies had moved unopposed up to the high ground east-northeast of the village.

Now that enemy resistance had been broken, Lovell’s 3rd Battalion, 307th, moved east along the road from Road Junction 415, the men advancing about 1,000 yards during the late afternoon. The 1st Battalion, ordered up a few hours earlier, also moved through Yigo and followed the 3rd. The 2nd Battalion moved to Yigo, where Major Mackin, battalion commander, set up his command post. In the village were found fifteen abandoned Japanese trucks and other mobile equipment, as well as several ammunition and food dumps, showing that the site had recently been a major part of the Japanese defense scheme.

No Japanese resistance was encountered during the afternoon. However, the 3rd Battalion was mistakenly strafed by American planes in midafternoon though, fortunately for the infantrymen, no one was hurt. Nightfall found the 307th Infantry in control of Yigo and a large area to the northeast, east, and southeast.34

Burning U.S. medium tanks disabled by enemy fire along the road to Yigo

While the 307th Infantry fought its way through Yigo on the afternoon of 7 August, the regiments on its flanks were also advancing, although with much less difficulty. The 306th Infantry, to the left, crossed the line of departure on time at noon. With the 3rd Battalion on the right, 1st on the left, the regiment advanced against scattered light resistance. Well over a hundred Japanese were claimed killed, while only three Americans were wounded. In its rapid movement up the Yigo road, the 3rd Battalion employed a type of tank-infantry tactics peculiarly adapted to the jungles of Guam. To the lead company of infantrymen was assigned a tank platoon. One tank moved through the brush on one side of the jungle trail, a second on the other side, and the remainder followed along the trail about a hundred yards to the rear. The object of this unorthodox formation was to permit the tanks to support each other, protect the lead tanks from mines located on the trail, and widen the trail for the infantrymen who would follow. With each vehicle went four infantrymen on foot to serve as guides, spotters, and protectors. In this manner, the 3rd Battalion pushed on through Yigo and then northeast about 900 yards along the Salisbury road. There, it dug in for the night.35

The 1st Battalion advanced along the Liguan road to the crossroads southwest of

Mount Mataguac where the new corps boundary left the trail. Although General Bruce had ordered the 306th Infantry to advance some 600 yards farther up the Liguan trail, the 1st Battalion during the afternoon ran into resistance from about forty Japanese with two machine guns just below the crossroads. With the help of the attached Company B, 706th Tank Battalion, the battalion eliminated the opposition but did not advance much farther. Had the 1st Battalion continued, it would have entered what was actually Marine territory under the new boundaries. This might have caused difficulties, since the 9th Marines had moved past the crossroads along and east of the Liguan trail, in an area that the 77th Division still thought to be within the Army zone of operations. However, since the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, had not yet advanced beyond the point of the boundary change, there had been no trouble so far.36

On the division right the 305th Infantry (less the 3rd Battalion) also advanced unopposed. With bulldozers blazing a trail through the thick jungle, the 2nd Battalion covered 1800 yards during the day and by nightfall was digging in about a mile northwest of Lumuna Point. The 1st Battalion, meanwhile, remained with regimental headquarters on the O-4 line, preparing to pick up the advance on 8 August.

No opposition impeded the movement of the 2nd Battalion, 305th Infantry, on 7 August. The only untoward incident of the day occurred around 1500 when American aircraft hitting Mount Santa Rosa mistakenly dropped a bomb on F Company, causing some casualties. Presumably, these were the same planes that strafed the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, about the same time.37

The night of 7-8 August found the 77th Division dug in in positions from which it could launch a final attack on Mount Santa Rosa the next day. Despite the day’s successes, there was some apprehension among the Americans as to possible Japanese moves during the night. As early as noon on 7 August, General Bruce had requested permission to move the 3rd Battalion, 305th Infantry, then in corps reserve, to Road Junction 415 at Yigo in midafternoon in order to get set for any enemy counterattack. A counterblow at Yigo, either down the Salisbury road or from Mount Santa Rosa, would almost certainly be initially aimed at this important junction. Bruce’s request was denied, but that night General Geiger informed subordinate units that he was expecting a counterattack in force and that the 3rd Battalion,

305th Infantry, and the Marine battalion in reserve with it were on call.38

Fortunately for the Americans, the Japanese mounted no major attacks during the night. Possibly the speed of the American advance during the day, combined with the heavy artillery bombardment that continued as harassing fire during the night, prevented a major enemy counterblow. Whatever the reason, the Japanese made only a few local counterattacks and attempts to infiltrate during the night.39 The first of these came shortly before 1920 when a small group of the enemy took advantage of the rapidly gathering dusk between sunset and moonrise to attempt to infiltrate the 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, east of Yigo. Alert infantrymen spotted the Japanese, however, and nine of the enemy were killed trying to penetrate the position.40

At 0230 corps sent another warning of a possible major Japanese counterattack to the 77th Division.41 Within an hour the biggest enemy attack of the night struck the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry. In the exposed position on the Salisbury road north of Yigo, these men had already been the target of two small enemy probing attacks. The first had been beaten off about the time of the attack on the 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry; the second had come around midnight and, in the bright moonlight, had been repulsed. The final attack against the 3rd Battalion began between 0300 and 0330.

This time, the enemy force consisted of three medium tanks and riflemen estimated to be of platoon strength. First came the Japanese tanks, firing their machine guns and cannon into the battalion perimeter. The defenders were safe in their slit trenches from the flat-trajectory machine gun fire, but the high-explosive cannon shells burst in the trees above, raining fragments down on the Americans. Attempts to knock out the tanks with bazookas and flame throwers were aborted by fire from the accompanying Japanese infantry. Two machine gunners finally got the first tank by waiting until it was almost upon them and then closing in with their light machine gun to fire into the tank through an aperture. They burnt out the barrel of their gun, but they also killed all the Japanese in the tank. A rifle grenade knocked out a second tank. This apparently discouraged the occupants of the third tank, since they drove their vehicle off with one of the other tanks in tow. The enemy infantry, deprived of their support, quickly followed. The 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, had killed eighteen Japanese while itself sustaining losses of six killed and more than a dozen wounded. The enemy attack, the largest of the night, had failed to penetrate the American position guarding the northern approach to Yigo.42

While the Army and Marine troops were forging ahead on 7 August, General Geiger issued orders directing that the pursuit of the enemy be continued at 0730 on 8 August.43 Later, he added, “Admiral Nimitz arrives 10 August. Push Japs off Guam before then.”44

The 77th Division plan for 8 August called for a continuation of the drive begun on the 7th. The 306th Infantry would complete its envelopment of the northern flank of Mount Santa Rosa with its 1st and 3rd Battalions while the 2nd Battalion followed with the command post. In the center of the division line, the 307th Infantry would attack with the 1st and 3rd Battalions abreast to seize Mount Santa Rosa; the 2nd Battalion was to be prepared to execute an enveloping attack up the southern slopes to bring the assault to a successful conclusion. Finally, the 305th Infantry (less 3rd Battalion in corps reserve) would continue to close in on Mount Santa Rosa and seal it off from the south. There was no plan for a division artillery preparation, although all battalions were available for call fire. As directed by corps, the infantry would attack at 0730.45

General Bruce’s force opened the assault on schedule. In the zones of operations of the 305th and 307th Infantry Regiments, the attack proceeded rapidly and with little or no difficulty. The 305th Infantry, on the division right, encountered only slight opposition in its short advance to the regimental objective area. The 2nd Battalion pushed forward about 1,000 yards to secure the left (northwest) half of the objective area, while the 1st Battalion followed the 2nd for a while and then, in the early afternoon, swung east to secure the rest of the objective zone. The 3rd Battalion, still in corps reserve, moved forward to set up defensive positions behind the 307th Infantry at Yigo and the important Road Junction 415. Casualties in the 305th Infantry were five killed and six wounded, while the regiment claimed to have killed twenty-five of the enemy.

Like the 305th Infantry, the 307th in the center of the division experienced little difficulty in its drive on 8 August. By H Hour the 1st Battalion had pulled abreast and to the right of the 3rd, approximately 1,000 yards east of Road Junction 415. Although the forward displacement of artillery battalions and some confusion as to unit locations prevented a brief artillery preparation requested by the regiment, the two battalions stepped off on schedule unopposed. About 0800, when potential opposition was revealed by a captured document indicating an enemy gun position before the 1st Battalion, artillery fire was quickly brought to bear on the target. By about 0830, when General Bruce arrived for a check at the 307th command post, the attack was well under way. Bruce himself went forward to look over the situation and immediately ordered the regimental commander to throw his 2nd Battalion into the planned envelopment from the south. Moreover, to exploit the situation further, he directed that the attached company of medium tanks (Company A), as well as all other supporting

regimental units, be used in the attack. When the 2nd Battalion went into action, the regiment made quick arrangements with the 305th Infantry to prevent a collision between the 2nd Battalion, 307th, and the left battalion of the 305th, since the trail that the 2nd Battalion was to follow led through the objective area of the 305th Infantry.

With the 307th Infantry attack well under way, twenty minutes after the 2nd Battalion had been committed, General Bruce enlarged the regimental mission. The regiment was not only to carry out its earlier mission of seizing Mount Santa Rosa but was also to push on from that height to the sea beyond. Within an hour Bruce also directed all available tanks of the 706th Tank Battalion (less Companies B and C) to join the company of mediums already with the 307th Infantry. By pushing through as fast as possible, the division might well end the fight in short order.

By 1050 the three battalions of the 307th Infantry were on a north-south line about 2,000 yards east of the Yigo area, having covered approximately 1,000 yards from the morning’s line of departure. Each battalion was astride a trail leading up the western slopes of Mount Santa Rosa, 3rd Battalion on the left (north), 1st in the middle, and 2nd on the right. So far Japanese opposition had been negligible, but a prisoner captured by the 1st Battalion – the first taken in over a week by the division – revealed strong potential resistance ahead. Talking freely, the captured Japanese stated that there were 3,000 of his compatriots in caves on Mount Santa Rosa. If this information were correct, the 307th Infantry might be in for a tough fight. Accordingly, the regimental commander, with the immediate approval of General Bruce who was impatient for the 307th to seize Mount Santa Rosa, ordered a new maneuver to wipe out any Japanese left on that height. The 2nd Battalion was to continue with its planned envelopment from the south while the 1st and 3rd Battalions were to follow a trail to the northeast until they were due north of Mount Santa Rosa and then attack south to hit the enemy from the north. The result would be a double envelopment that, it was hoped, would crush the enemy between its two wings.

The elaborate preparations proved unnecessary, for if 3,000 Japanese had ever been on Mount Santa Rosa they were no longer there. It is little wonder. Since 3 August, Admiral Conolly’s fire support ships had been bombarding the mountain day and night. Seventh Air Force P-47’s and B-25’s, flying down regularly from Isely Field on Saipan, had intensified the destruction. The infantry and tank advance in the 307th Infantry sector was almost completely unopposed. By 1240 the northern half of Mount Santa Rosa was in American hands, and as the regiment moved to secure the rest of the mountain the 1st Battalion continued to push on to the sea. Shortly before 1400, with the entire height under regimental control, the command post of the 307th Infantry began displacing forward to the summit of Santa Rosa. By 1440 the 1st Battalion commander reported he had reached the cliffs along the sea and could look down into the water. Regimental patrols were ranging over the entire Santa Rosa area. As night fell the regiment was still mopping up small isolated groups of the enemy, patrolling, and digging in. It had not encountered any large force of Japanese. The day’s action had cost the 307th Infantry

only one man killed and a dozen wounded; less than fifty Japanese were claimed killed.46

The relatively easy time enjoyed by the 305th and 307th Infantry Regiments on 8 August was shared in part by the 306th Infantry, but the latter regiment had difficulties arising out of miscalculation as to the location of the division boundary on its left and a failure to observe the regimental boundary on the right. Colonel Smith’s regiment jumped off on time from the positions it had secured the night before: 3rd Battalion on the right, on the Salisbury road about 900 yards above Yigo; 1st Battalion on the left, in the vicinity of the crossroads southwest of Mount Mataguac marking the point where the boundary change began. The 2nd Battalion, near the regimental command post on the Finegayan-Yigo road about a mile below Yigo, was prepared to follow and join the action when necessary. The regimental advance would also be supported by Company B, 706th Tank Battalion, which at that time was still attached.

The two lead battalions of the 306th moved forward unopposed, the 3rd advancing along the Salisbury road and the 1st continuing along the Liguan road from the crossroads. The advance of the 1st Battalion led it into the Marine zone, and the fact that the 9th Marines had cleared this area on the previous day probably accounted for the lack of resistance to the Army battalion. By 0910 the 1st Battalion had advanced about 1,000 yards up the trail, and had been in contact with the marines since 0840. To the east the 3rd Battalion had made a similar gain, while the 2nd Battalion jumped off in column at 0900 to follow the 3rd.

By about 0930 the 3rd Battalion was well into its turning movement, cutting a trail east from the Salisbury road at a point about 2,400 yards above Road Junction 415. At the same time, the 1st Battalion apparently was either beginning its turn to the east to follow the 3rd or was preparing to begin its turn. It was encountering slight opposition.

About 0955, however, General Bruce, then at the 307th Infantry command post and eager to exploit that regiment’s gains, ordered a change in the mission of the 306th Infantry. One battalion was to drive all the way east to the coast, instead of halting on the north side of Mount Santa Rosa; another battalion was to push northeast on the Salisbury road all the way to Pati Point at the far northeast corner of Guam; the remaining battalion would set up a roadblock on the Salisbury road, midway between Salisbury and Yigo where another trail came down from Chaguian to the northwest. Thus the 3rd Battalion would continue its drive east; the 1st Battalion, instead of following, would advance on Pati Point; and the 2nd Battalion roadblock at the junction of the Chaguian trail and the Salisbury road would protect the rear of the other two battalions.

In its movement to the east, the 3rd Battalion and supporting tanks met no opposition. The path they were cutting, however, led the battalion southeast rather than east. A slight southeast movement was necessary,

but the troops went too far and, before they realized it, were in the 307th Infantry zone of operations. By 1110 the battalion found itself on a trail on the northwest slope of Mount Santa Rosa, nearly 1,000 yards south of the regimental boundary and blocking the planned route of advance of the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, to the northern flank of the mountain.

The trail that the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, now blocked led northeast toward the Lulog area. If the battalion could follow this trail with the same speed as the day’s earlier advance, it would soon reach its objective and be out of the way of the 307th Infantry. However, about this time the 3rd Battalion’s leading elements began to encounter light, scattered, enemy opposition, which slowed the advance. Most of the Japanese had little desire to fight. Still stunned by the terrific artillery, air, and naval bombardment, many of them simply huddled in caves or huts and waited to be killed. A few offered desultory resistance; some committed suicide. When enemy strongpoints were encountered, however, well-coordinated infantry-tank teams, with flame throwers and pole charges, quickly dealt with the resistance.

The advance of the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, was still not fast enough to suit either the 307th Infantry or General Bruce. Meanwhile, the men of the 3rd Battalion, 306th, were not too happy when tanks with the 307th accidentally began firing in their direction. This fire was stopped, but the 306th infantrymen were ordered to move out of the area, or at least off the main trail, as soon as possible. By early afternoon the 3rd Battalion had either left the trail or advanced far enough to permit the 307th Infantry to secure its operational area unhindered. Indeed, midafternoon found the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, in full possession of the Lulog area and with strong patrols between that point and the sea. By nightfall the entire Lulog–Anao Point area was in the hands of Kimbrell’s men.

While the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, struggled to keep out of the way of the 307th Infantry, Colonel Smith’s other two battalions of the 306th were having difficulties of their own. West of the Salisbury road, the 1st Battalion was moving cross-country unopposed in a general northeasterly direction in what it believed was 77th Division territory. Its aim was apparently to regain the Salisbury road and then follow the road in the direction of Pati Point. About 1030, however, the battalion reported that Marine units on the Chaguian trail – who were actually in what the marines correctly believed to be their own zone – were blocking the Army advance. Moreover, the marines on the Chaguian trail, and along another trail leading from the Chaguian trail northeast toward Salisbury that the soldiers apparently had themselves hoped to follow, claimed that they were going to Pati Point. Reporting this to corps, General Bruce said he had no objection to following the marines on up, but he asked that the 3rd Marine Division troops clear rapidly so that the soldiers could continue their mission. This was agreeable to corps headquarters. The marines were directed to move forward rapidly, and the Army troops were ordered to follow.

Shortly after 1100 General Bruce decided that if the marines were going to Pati Point in force there was no need of sending more than a small group of Army troops in that direction. By now he had

received the report that 3,000 Japanese might still be on Mount Santa Rosa, and in his desire to insure the success of the 307th Infantry’s drive he made another change in the orders for the 306th. Instead of setting up a roadblock on the Salisbury road, the 2nd Battalion, 306th Infantry, was to follow the 3rd Battalion in its advance east, prepared to support the latter or, if necessary, to move to the aid of the 307th Infantry. The 1st Battalion, meanwhile, would send only one company up the Salisbury road, and that solely to maintain contact with the marines. The rest of the 1st Battalion was to join the regimental command post group, which had moved up with the 2nd Battalion, apparently to be used as the regimental commander saw fit.

The 1st and 2nd Battalions, 306th Infantry, moved to carry out their new assignments. Shortly after noon lead elements of the 2nd Battalion moving up the Salisbury road reached the turn-off point where the 3rd Battalion had begun cutting its trail to the east that morning. A few minutes later the 1st Battalion (less one company) began moving back toward the regimental command post, just below the junction of the Chaguian trail and the Salisbury road.

Beginning about 1215 and continuing for approximately two hours, troops of the 306th Infantry in the confused area along the Salisbury road found themselves under fire from a quarter they least expected. About 1215, 2nd Battalion elements making the turn to the east began receiving rifle and machine gun fire that they thought might have been from Marine weapons. Half an hour later Company F, bringing up the rear of the battalion, was engaged at the junction of the Chaguian trail and Salisbury road by a force that the soldiers were convinced was composed of marines. Notified of this, the 3rd Marine Division replied that it had no troops in that immediate area but that the firing might have been done by some Japanese troops left over from a scrap the marines had had there that morning. By the time this information was relayed back to F Company, however, the fire fight had stopped as mysteriously as it had begun. No sooner was this over than pack howitzer fire began to fall on the regimental command post below the road junction. This time there was no mistake; fragments taken from the wounds of one soldier proved conclusively to be from a Marine weapon. Again, not long after this shelling had been stopped, an Army motor column moving up the Salisbury road came under machine gun fire, which the soldiers again blamed on the marines.

The climax of the confusion came about 1400, when a battalion of the 9th Marines began moving east off the Salisbury road on the trail that the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, had cut that morning. Earlier, Marine and Army units had conflicting overlays to show that each was in its own zone of operations, but this time there was no doubt that the Marine battalion was in the Army zone. The Marine commander, however, in the apparent belief that he was still on the Salisbury road, stated that he had permission to be where he was and refused to withdraw. Finally, the 306th Infantry commander was able to persuade a Marine staff officer of the error and the Marine commander reluctantly agreed to turn his battalion around and march it back.

By about 1500 everything appeared to have been straightened out. The shooting had stopped; there were no Army troops in the Marine area; there were no Marine

troops in the Army area. The 1st Battalion (less the company charged with maintaining contact with the marines) and the regimental command post group had moved east on the heels of the 2nd Battalion, which was now advancing against extremely light and scattered resistance behind the 3rd Battalion. Completion of the regimental mission was relatively easy, and at 1715 the 306th Infantry reported itself dug in across the northern face of Mount Santa Rosa. The 3rd Battalion had reached the sea at Anao Point; the 2nd Battalion was tied in to its west; the regimental command post was at Lulog; and the 1st Battalion was along the trail west of the command post. The day’s action had cost the regiment 11 men killed and 24 wounded, while 172 Japanese were claimed killed.47

As if the confusion between American units during the daylight hours of 8 August had not been enough, just at sunset the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, west of Lulog, and the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, to the south on Mount Santa Rosa, were involved in another tragic incident. About 1830 both battalions began receiving mortar fire. This was either Japanese fire or, more probably, fire from American weapons being zeroed in for the perimeter defense that night. Unfortunately, the fire hitting the 306th Infantry troops came from the south, where the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, was digging in, while the shells that landed in the 307th area came from the north, where 306th Infantry troops were preparing their defenses. Both battalions reported a counterattack and opened fire with small arms in the direction of the presumed assault, which only served to increase the illusion of a counterattack. Tanks of the 306th Infantry began shooting, and both battalions called down artillery fire.

Fortunately for those involved, the confusion was short lived. Within the space of a few minutes it became apparent that the troops were exchanging shots with their fellow Americans, and all firing was halted. The 902nd Field Artillery Battalion had fired a brief barrage and both infantry battalions had done considerable firing on their own. The result was at least ten casualties in the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, and a smaller number of casualties in the 1st Battalion and regimental command post of the 306th Infantry.48

The Marines: 7-8 August

On the morning of 7 August, General Geiger for the first time had all three of his units deployed abreast for the attack. The 1st Provisional Brigade, which had spent the past days resting and patrolling southern Guam, was now fed into the line to the left of the 3rd Marine Division and made responsible for securing the northwest coast of the island including Mount Machanao and Ritidian Point. The mission

Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift being greeted at Orote airfield by (from the left) Maj. Gen. Henry L. Larsen, General Geiger, and General Holland Smith on 10 August

of the 3rd Marine Division, in the center of the corps attack, was to continue to push to the north and northeast until it reached the sea in the vicinity of Tarague Point.

The 7th of August was a relatively quiet day for both Marine units. The 3rd Division came across a few antitank guns guarding a roadblock in the neighborhood of Road Junction 390 but quickly reduced it without casualties. By 1530 elements of the division reached the O-5 line along the trail that ran southeast from Road Junction 460 to the Yigo-Salisbury road. There, the entire division dug in for the night after a day’s advance of about 6,000 yards. On the left, the brigade’s 4th Regiment kept pace and succeeded in occupying a line running due west of Road Junction 460. Pausing there, General Shepherd late in the afternoon brought in the 22nd Marines to take over the western (left) half of the brigade line.49

The next day the chief obstacle facing the Marines was again jungle rather than Japanese. The only reported fighting in the zone of the 3rd Division was around a roadblock manned by nineteen enemy

soldiers. These were quickly eliminated. Nightfall found the division on a line north of Salisbury about a mile and a half from the sea. At the same time the 22nd Marines forged ahead up the west coast in the wake of a series of well-placed aerial bombing attacks. By midafternoon marines of the 22nd Regiment reached Ritidian Point, the northernmost point of Guam.50

The End on Guam

By nightfall of 8 August the end of fighting on Guam was virtually at hand. The gains of the 77th Division around Mount Santa Rosa, the advance of the 3rd Marine Division to within a mile and a half of the sea, the occupation by the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade of the entire northwest coast of the island to Ritidian Point – all spelled the doom of the remaining Japanese. That night even Radio Tokyo conceded that nine tenths of Guam had fallen to American troops.51

The capture of Mount Santa Rosa by the 77th Division marked the end of organized resistance on Guam, for this was the last Japanese stronghold on the island, and the enemy now had no important rallying spot. Only a little more than 500 Japanese dead were discovered on Santa Rosa, far less than the number of enemy troops there at the beginning of the attack, and far less than General Bruce had expected to encounter. Apparently the extremely heavy preassault bombardment forced most of the defenders to flee the area. The Japanese were denied their last major defensive area on Guam and were driven north into the jungle in a completely disorganized state.

On the evening of 8 August General Geiger ordered the pursuit to continue at 0730 the following morning.52 Accordingly, on 9 August, the 77th Division moved out on schedule to complete its mission. The 306th Infantry patrols sent northward to the sea to flush the area between Lulog and the north coast encountered only scattered and light resistance. The 307th Infantry on Mount Santa Rosa patrolled vigorously between that height and the seacoast to the east. The 305th Infantry (less 3rd Battalion) moved to an assembly area south of Barrigada. Nowhere in the division zone on 9 August was any organized resistance encountered. The same held true for the 10th.53

To the west, marines of the 3rd Division and 1st Provisional Brigade encountered only a little more difficulty. During the early morning hours of 9 August, the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, came under attack by five enemy tanks accompanied by infantrymen. The marines withdrew into the jungle without suffering any casualties and by daylight the enemy force had disappeared. That day the 3rd Marines gained another 1,500 yards, which put it roughly about the same distance from the sea. At the same time, the 9th Marines completed its particular assignment by reaching Pati Point. On the corps left, the brigade extended its control southeast from Ritidian Point as far as Mergagan Point.54

The next day, 10 August, with only a small pocket between Mergagan Point and Pati Point left to be occupied, General Geiger at 1131 announced that organized resistance on Guam had ended.55 The announcement was timed to correspond with the arrival on Guam of Admirals Nimitz and Spruance and Marine Generals Holland Smith and Vandegrift aboard Spruance’s flagship Indianapolis.

The official conclusion of the campaign did not mean it was actually over, for soldiers and marines were to spend many dreary weeks before they finally cleaned out the enemy-infested jungles and mountains of Guam. Even though all signs of Japanese organized resistance were crushed, General Obata killed (on 11 August), and the island overrun, there still remained unaccounted for a large number of Japanese who had fled into the jungles in small groups and continued to harass the American garrison, even until after the end of the war. Two officers, who were eventually captured, Colonel Takeda and Major Sato, vainly attempted to organize these survivors, but they remained for the most part isolated stragglers. Almost all were too preoccupied with the eternal search for food to think of fighting, and their weapons and ammunition were saved for hunting until they rusted for want of lubricating oil. American patrols killed a few every day; others succumbed at last to the siren song of American psychological warfare and gave themselves up.56

Eventually, the entire Japanese garrison on Guam, numbering about 18,500, was killed or captured. In exchange, American casualties as of 10 August 1944 came to 7,800, of whom 2,124 were killed in action or died of wounds. Of this total, the Army accounted for 839, the Navy for 245, while the remaining 6,716 were marines.57

Blank page