Chapter 5: Prelude to the Battle of the Driniumor

While operations at Hollandia were rapidly drawing to a successful conclusion, another action was just beginning at Aitape, 125 miles to the southeast. The PERSECUTION Task Force, with the 163rd Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Infantry Division as its combat nucleus, landed near Aitape on 22 April, D Day for Hollandia as well. The principal objective of General Doe’s PERSECUTION Task Force was the seizure and rehabilitation of the Japanese-constructed Tadji airstrips, eight miles east-southeast of Aitape. These fields were to provide bases from which Allied aircraft could support ground operations at Hollandia after the Fifth Fleet’s carriers left the latter area. General Doe’s command was also to provide ground flank protection for Hollandia by preventing westward advance of the Japanese 18th Army, assembling some ninety miles southeast of Aitape at Wewak.1 (Map 3)

Securing the Airfield Area

The Tactical Plan

Knowledge of beach conditions in the Aitape area was obtained principally from aerial photographs, and the PERSECUTION Task Force landing beach was chosen with reference to beach exits and shore objectives as they appeared on these pictures. The shore line opposite the Tadji airfields, which lay only 1,000 yards inland, was uniform and sandy for long distances. There were clear approaches to the beach, which had a medium rise. The selected landing point was located at Korako, a native village on the coast at the northeast corner of the airfield area. From this point, which was designated BLUE Beach, a track passable for wheeled vehicles ran directly inland to the Tadji strips.2 The PERSECUTION Task Force was to begin landing at 0645, high tide time in the Aitape area. In charge of the amphibious phases of the operation was Capt. Albert G. Noble (USN), whose command, the Eastern Attack Group (Task Group 77.3), was part of Admiral Barbey’s Task Force 77. Close air support operations at Aitape were primarily the responsibility of planes aboard eight CVEs and were similar to the air support activities carried out by Task Force 58 at Hollandia. Initially, last-minute beach strafing at BLUE Beach was planned to continue

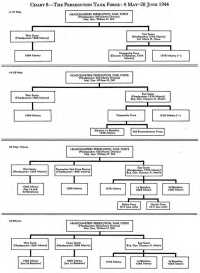

Chart 7: The PERSECUTION Task Force:, 22 April–4 May 1944

until the leading wave of landing craft was within 300 yards of the shore. But General Doe believed that such close-in strafing would endanger the troops aboard the landing craft. It was therefore decided that strafing would begin when the leading boat wave was 4,500 yards from shore (expected to be at H minus 15 minutes) and would end when that wave approached to within 1,200 yards of the shore, timed for about H minus 4 minutes.3

The Allied Air Forces also had important air support missions at Aitape. A squadron of attack bombers (A-20’s or B-25’s) was to be in the air over the landing area from 0830 to 1030 on D Day. After 1030, if no earlier calls for bombardment had been made, these planes were to drop their bombs on targets on both flanks of BLUE Beach. Two squadrons of attack bombers were to be maintained on daily alert at a field in eastern New Guinea for as long as the situation at Aitape required, and additional air support at Aitape would be provided upon request from ALAMO Force.4

Naval fire support for the landings on BLUE Beach was to be executed by 5 destroyers, 9 APDs, and 1 AK. This was the first time that APDs or AKs had been assigned fire support missions in the Southwest Pacific. Targets for the destroyers were similar to those assigned naval fire support vessels at Tanahmerah and Humboldt Bays. Six APDs were to fire on St. Anna and Tadji Plantation (west of the airstrips), on enemy defensive installations at or near Aitape town, and on the offshore islands—Tumleo, Ali, and Seleo. The AK was to aim its 5-inch fire at Tumleo and Ali Islands.

Close-in support was to be provided for the leading landing waves from 0642 to 0645 by rocket and automatic weapons fire from two submarine chasers. All destroyers, submarine chasers, and the AK were to deliver fire upon call from forces ashore after H Hour.5

At 0645 the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 163rd Infantry, were to land abreast on BLUE Beach. As soon as a beachhead had been secured the 1st Battalion was to land and, aided by the 2nd, was to initiate a drive toward the Tadji strips. After the airfields had been captured, the 2nd Battalion was to defend the task force’s western flank, the 1st was to establish defenses along the southern edge of the airfield area, and the 3rd was to defend the eastern flank. On D plus 1 the 127th Regimental Combat Team, 32nd Division, was to reach BLUE Beach. Then patrols west and east of the beachhead were to begin seeking out Japanese forces, and, as soon as possible, Aitape town was to be captured.

Field and antiaircraft artillery going ashore on D Day were to protect and support the infantry’s operations and the engineers who were to start work on the airfields immediately after they were secured. Engineers and other service troops not assigned to airfield construction tasks were to unload ships, improve roads and tracks, build or repair bridges over streams in the beachhead area, and find and clear dump and bivouac sites.6

The Capture of the Airfields

At 0500 on 22 April, after an uneventful trip from the Admiralties, the Eastern Attack Group convoy arrived in the transport area off BLUE Beach.7 The assault troops of the 163rd Infantry, Col. Francis W. Mason commanding, immediately began debarking into LCPRs from the APDs which had brought them to Aitape. Naval gunfire and aerial support was carried out almost exactly as planned, and the first wave of LCPRs hit the shore on schedule at 0645. It would have been a model landing except for one thing—it didn’t take place on BLUE Beach.

D Day had dawned dull and overcast, making for poor visibility in the landing area. Heavy smoke from fires set in Japanese supply dumps by preassault bombardments further obscured the coast line. With no landmarks to guide them, the coxswains of the leading boat wave missed BLUE Beach and the landing took place at Wapil, a small coastal village about 1,200 yards east of Karako. The accident proved a happy one, for it was soon discovered that the Wapil area was much better suited to beaching LSTs and large landing craft than any other in the Aitape region.

For the assault troops the change in beaches created little difficulty, since the Wapil area had been adequately covered by support fires and there was no opposition from the Japanese. Tactical surprise was as complete as that achieved the same day by the RECKLESS Task Force at Hollandia. Leaving breakfasts cooking and bunks unmade, the Japanese at Aitape had fled in panic when the naval support fire began.

The 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, had landed on the right, or west. The unit immediately swung west along the beach to

Map 3: Aitape Landings, 22 April 1944

Map merged onto previous page

find Karako and the trail leading inland to the Tadji strips. This task was accomplished by 0800 and the two battalions quickly expanded the beachhead to a depth of 500 yards and westward about 2,500 yards from Wapil to Waitanan Creek. This area, occupied by 1000, marked the limits of the task force’s first phase line. So far, opposition had consisted of only a few rifle shots. Three Japanese prisoners had been captured and over fifty Javanese laborers had willingly given themselves up. The two assault units now waited for the landing of the 1st Battalion and for an order from General Doe to move on the Tadji strips.

The 1st Battalion was assembled ashore by 1030 and, passing through the 3rd, started moving inland toward Tadji Bomber Strip at 1100. Simultaneously, the 2nd Battalion began advancing on Tadji Fighter Strip, north of the bomber field. The 3rd Battalion remained at the beach area.

The advance inland was slow and cautious but by 1245 the 2nd Battalion had cleared its objective and the 1st soon secured Tadji Bomber Strip against no opposition. The 2nd Battalion then moved across Waitanan Creek to Pro and Pro Mission, which were found clear of Japanese. The battalion command post was set up at Pro before dark, while the rest of the unit bivouacked along trails leading inland to the fighter strip. The 1st Battalion settled down for the night at the west end of the bomber field. During the afternoon the 3rd Battalion sent patrols east from Wapil to the coastal villages of Nor, Rilia, and Lemieng, noting no enemy activity. Three miles east of Wapil, at the mouth of the Nigia River, an outpost was set up. The bulk of the battalion bivouacked along the eastern edges of the two captured strips.

By dark on D Day the principal objectives of the PERSECUTION Task Force had been secured. Work could be started on the airfields, needed to insure land-based air support for both the Aitape and Hollandia beachheads. The strips had been secured at an amazingly low cost—two men of the 163rd Infantry had been killed and thirteen wounded.

Airfield Construction and Supporting Arms

No. 62 Works Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, had come ashore at BLUE Beach during the morning and had been able to start work on Tadji Fighter Strip at 1300. Repairs continued throughout the night under floodlights, the lack of Japanese opposition and the urgency of the task prompting General Doe to push the work. Although it had been hoped that the strip would be ready for use on D plus 1, terrain conditions were such that necessary repairs were not completed on schedule. Thus it was 0900 on 24 April before the Australian engineers, who had worked without break for almost forty-eight hours, could announce that the airstrip was ready. At 1630 twenty-five P-40’s of No. 78 Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, landed on the field, and the balance of the wing arrived the next day.8

The ground on which the fighter strip was located was so poorly drained that it was not until 28 April, after steel matting had been placed on the field, that it could be used continuously.9 The works wing then

Troops unloading supplies at Aitape. In the background are the two AKs

moved to Tadji Bomber Strip to aid the 872nd and 875th Engineer Aviation Battalions. The latter two units passed to the operational control of Wing Commander William A. C. Dale (RAAF), who, besides commanding the works wing, was PERSECUTION Task Force Engineer. Extensive repairs were necessary at the bomber strip and that field was not ready for use by fighter and transport planes until 27 May and for bombers until early July.10

Other engineer units ashore on D Day directed their energies to ship unloading, road and bridge construction, and dump and bivouac clearance. By 1930 the 593rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment (the Shore Party) and the Naval Beach Party had unloaded all D Day LSTs. The next day one AKA and seven more LSTs were discharged. Unloading of the two AKs did not proceed as rapidly as expected, for neither ship had been properly combat loaded. The AK which arrived on D Day was only 65 percent discharged when, during the night of 27–28 April, it was hit by a bomb dropped from a lone Japanese plane flying in from an unknown base in western New Guinea. The other AK, undamaged, towed the first back to Finschhafen, returning then to BLUE Beach to complete its own unloading. No other untoward incident

marred the debarkation of troops and supplies.11

American engineers constructed roads inland from BLUE Beach to the airstrips and improved the coastal roads. Light Japanese culverts and bridges in the area had collapsed under the weight of American and Australian heavy equipment or had been damaged by preassault bombardment, making repairs a pressing problem. Australian engineers bridged Waitanan Creek while American engineers threw a bridge across the Nigia River, on the east flank. Pending completion of other bridges, American engineers maintained ferry services across the main streams. On 2 May heavy rains flooded all streams in the area, wiping out much bridge construction already accomplished, damaging ferry stages, and making necessary extensive repairs or new construction. Continued rain during May made road maintenance so difficult that engineers working on airstrips or bridges had to devote much time to the roads.12

Artillery moved ashore on D Day without difficulty. The 167th Field Artillery Battalion, supporting the 163rd Infantry, was in position and registered on check points by H plus 4 hours but fired no support mission while in the Aitape area. On D plus 1 the 190th Field Artillery Group assumed command of all field artillery, and on the same day the 126th Field Artillery Battalion of the 32nd Division arrived. Antiaircraft artillery came ashore rapidly on D Day and set up positions along BLUE Beach and around Tadji Fighter Strip.13

Securing the Flanks

While engineers continued work through the night of 22–23 April, other elements of the task force made preparations to expand the perimeter.14 (Map III) About 0800 on the 23rd, the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry, started westward over inland trails to the Raihu River, six miles beyond BLUE Beach. A tank of the 603rd Tank Company, which was supporting the advance, broke through a Japanese bridge over Waitanan Creek, but the infantry continued westward and within an hour had secured incomplete Tadji West Strip. The 2nd Battalion pushed west along the coastal track and by noon reached the mouth of the Raihu. Both battalions bivouacked for the night on the east bank, the 1st at a point about 4,000 yards upstream. During the day the 3rd Battalion (which had been relieved on the east flank and at BLUE Beach by elements of the 127th Infantry) moved forward with regimental headquarters to Tadji Plantation, 1,200 yards east of the Raihu and about 2,000 yards inland. So light had Japanese opposition been that the 163rd Infantry had suffered but two casualties—one man wounded and another missing.

The next day the 1st and 2nd Battalions resumed the advance at 0730. The 1st crossed the Raihu and pushed northwest over ill-defined tracks to establish contact,

about 0930, with the 2nd Battalion at the mouth of a small creek 1,800 yards west of the Raihu. Colonel Mason now halted the 1st Battalion and ordered it to patrol the trails radiating south and west from its new position. The 2nd Battalion moved on along the coast to Aitape, securing that town and the near-by dominating height at Rohm Point by 1100. The unit had met no Japanese and was preparing to push on when, early in the afternoon, Colonel Mason ordered it to stop. The 3rd Battalion was ready to pass through the 1st and move forward over inland trails, but the regimental commander suddenly ordered both it and the 1st to retire to the east bank of the Raihu for the night. It is not clear why this withdrawal was ordered. Japanese opposition had been almost nonexistent and the 163rd Infantry had lost only one man killed during the day.

General Doe was by now dissatisfied with the pace of the westward advance, and he therefore suggested to ALAMO Force that the 163rd’s commander be relieved. This step was approved by General Krueger, although the regimental commander remained in control of his unit until 9 May, only two days before the 163rd Infantry began loading for another operation.15

For the next few days there were no major changes in the dispositions of the 163rd Infantry as patrolling inland and along the coast west of Aitape continued. Patrol bases were set up at inland and coastal villages to hunt down Japanese attempting to escape westward from the Aitape area. At the Kapoam villages, about twelve miles up the Raihu, elements of the 3rd Battalion encountered the only signs of organized Japanese resistance found in the Aitape area to 4 May. At one of these villages—Kamti—outpost troops of the 3rd Battalion were surrounded by an estimated 200 Japanese who made a number of harassing attacks on 28 and 29 April. These skirmishes cost the battalion 3 men killed and 2 wounded, while it was estimated that the Japanese lost about 90 killed. On 30 April the men at Kamti withdrew while Battery A, 126th Field Artillery Battalion, fired 240 rounds of 105mm. ammunition into the village and its environs. The next morning Company L, 163rd Infantry, moved back to Kamti against no opposition. There were few further contacts with the Japanese on the west flank and all outposts of the 163rd Infantry were relieved by 32nd Division troops early in May.

The 127th Regimental Combat Team (less the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, and Companies F and G of the same regiment) had unloaded at BLUE Beach on 23 April.16 About 0700 the same morning, after an air and naval bombardment, Companies F and G landed on Tumleo and Seleo Islands off BLUE Beach, securing them against minor opposition by 1400. On 25 April Company G occupied the third large offshore island, Ali, without difficulty. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, arrived at BLUE Beach on 26 April and established its headquarters near Korako. The 2nd Battalion relieved the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, on the east flank, and the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, established a defense line along the southern and eastern edges of Tadji Bomber and Fighter Strips.

Patrols of the 2nd Battalion moved east along the coastal track to the mouth of the Driniumor, about twelve miles beyond BLUE Beach; up the banks of the Nigia River five miles to Chinapelli; and up the west bank of the Driniumor about six miles to Afua. From Afua a trail was found running westward through dense jungle to Chinapelli by way of a village called Palauru. From Chinapelli one track ran north to the mouth of the Nigia and others wandered off in a westerly direction toward the Kapoam villages. From the Driniumor two main trails were found leading eastward—one the principal coastal track to Wewak and the other a rough inland trace originating at Afua.

The latter trail paralleled the coast line and ran along the foothills of the Torricelli Mountains. North of the trail was a flat coastal plain, generally forested with dense jungle growth and containing numerous swampy areas and a multitude of small and large streams. The plain narrowed gradually from a depth of about ten miles at the Nigia River to less than a mile at the Danmap River, flowing into the Pacific about forty-five miles east-southeast of Aitape. Beyond the Danmap, toward Wewak, was more rolling terrain where hills descended from the Torricelli Mountains down to the sea. The trail east from Afua crossed the many streams between the Driniumor and the Danmap at points three to five miles south of the coast.

It was essential to the security of the newly won Tadji strips that any Japanese movements westward from Wewak along both inland and coastal trails be discovered and watched. Therefore, it was decided to send Company C, 127th Infantry, reinforced by part of Company D, by boat to Nyaparake, a coastal village about seventeen miles east of the Nigia River. There the reinforced company, known as the Nyaparake Force, was to set up a patrol base and report and delay Japanese movements in the vicinity.

On 28 April the unit boarded small boats at BLUE Beach and sailed eastward along the coast, missing its objective and landing near the mouth of the Dandriwad River, about eight miles east of Nyaparake. This error was quickly discovered but the force remained at its position for three days, sending out patrols in all directions. Few signs of enemy activity were observed, and the five Japanese killed in the area appeared to be stragglers rather than representatives of any organized unit of the 18th Army. On 1 May the unit moved by water back to Nyaparake. Outposts were established about four miles inland at Charov and Jalup, where the principal inland trail crossed the Drindaria River, and patrols were sent to the east and west over the inland trail and in both directions along the coastal track. The Nyaparake Force noticed no signs of organized enemy activity in the areas patrolled during the next few days.

Meanwhile, patrols of the 2nd Battalion had moved along the coast from the Driniumor River to Yakamul, four miles west of Nyaparake. Elements of the 1st Battalion maintained a patrol base at Afua for four days, and 3rd Battalion patrols scouted trails from Chinapelli to the Tadji strips and the Kapoam villages. No signs of organized enemy movements were discovered, and only weary Japanese stragglers attempting to make their way inland and westward were encountered. This complete lack of organized Japanese operations in the area patrolled by the 127th Infantry to 4 May, together with the surprisingly easy seizure of the Tadji strips by the 163rd Infantry,

contradicted preassault estimates of the enemy situation in the Aitape area.

The Enemy Situation to 4 May

Prior to 22 April the Allies had estimated that 3,500 Japanese, including 1,500 combat troops of the 20th Division, were based at Aitape. The indications are that not more than 1,000 Japanese of all arms and services were actually in the Aitape area on D Day.17 These troops comprised mostly antiaircraft artillerymen and service personnel who fled inland when Allied landing operations began. No organized resistance was encountered except for the skirmishes at Kamti, and the only evidence of centralized command in the area was a captured report, dated 25 April, from the Commander, Aitape Garrison Unit, to the 18th Army. The document told of the Allied landings, described operations to 25 April, set the strength of the Aitape Garrison Unit at 240 troops, and outlined a grandiose plan of attack, which probably culminated in the action around Kamti. Unknown to the Allies, there had been a small scouting party of the 20th Division at Aitape on D Day, but after the landings this group withdrew eastward to rejoin the main body of the 18th Army. Other Japanese survivors in the Aitape area tried to make their way westward to Vanimo, a minor enemy barge hideout on the coast between Aitape and Hollandia.18

Between 22 April and 4 May, Japanese casualties in the Aitape area were estimated at 525 killed, and during the same period 25 of the enemy were captured. Allied losses were 19 killed and 40 wounded. All the Allied casualties were American, and with but two or three exceptions all were suffered by the 163rd Infantry.19

There were a few signs that the 18th Army might be initiating a movement westward from Wewak toward Aitape, since interrogations of natives and aerial reconnaissance produced indications of organized enemy activity far beyond the east flank of the PERSECUTION Task Force. The Japanese were reported to be bridging the Anumb River, about fifteen miles east of the Danmap. Motor vehicles or their tracks were observed along the beach and on the coastal trail from Wewak west to the Anumb, and aerial observers and Allied ground patrols found that enemy parties were reconnoitering the coastal track from the Danmap River west to the mouth of the Dandriwad. Natives reported that organized Japanese groups were bivouacking at various coastal villages between the Dandriwad and Danmap.

Intelligence officers of the PERSECUTION Task Force and ALAMO Force interpreted these activities as indicating that an organized westward movement by 18th Army units was under way. Whether or not this movement presaged an attack on the PERSECUTION Task Force was not yet clear, but it seemed certain that Allied troops on the east flank might soon meet strong Japanese units.20

Contact with the 18th Army on the East Flank

While the PERSECUTION Task Force was accomplishing its primary mission—seizure and repair of the Tadji strips—final plans were being made at higher headquarters for another operation in the Wakde–Sarmi area of Dutch New Guinea, 250 miles northwest of Aitape. The 163rd Regimental Combat Team and General Doe with most of his staff were to participate in the new advance, which was scheduled for mid-May. General Krueger therefore directed that the 163rd Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Division be relieved of combat in the Aitape area and concentrated at BLUE Beach by 6 May to begin staging for Wakde–Sarmi.21

Reorganization of the PERSECUTION Task Force

The 32nd Infantry Division, less two regiments, was to move from Saidor in eastern New Guinea to Aitape to relieve the 163rd Regimental Combat Team. The 127th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division had already arrived at Aitape. Initially, the 128th Infantry was to remain at Saidor as part of the ALAMO Force Reserve for Wakde–Sarmi. The remainder of the 32nd Division, consisting of the 126th Regimental Combat Team and division troops, arrived at BLUE Beach on 4 May. Maj. Gen. William H. Gill, the division commander, immediately assumed command of the PERSECUTION Task Force and two days later his division staff, after becoming acquainted with the situation in the Aitape area, began activity as Headquarters, PERSECUTION Task Force.22

Just before the Wakde–Sarmi operation began, it was decided to move the 128th Infantry from Saidor to Aitape so that the unit would be closer to its potential objective area in case of need. Noncombat ships being available, the 128th Infantry (less the 3rd Battalion) was shipped to BLUE Beach, where it arrived on 15 May. The rest of the regiment, together with rear echelons of other 32nd Division units, arrived at Aitape later in the month. Early in June the 128th Infantry was released from its ALAMO Force Reserve role for Wakde–Sarmi and reverted to the control of the 32nd Division and the PERSECUTION Task Force.23

As soon as General Gill assumed command of the PERSECUTION Task Force, defenses in the Aitape area were reorganized. The area west of Waitanan Creek, designated the West Sector, was assigned to the 126th Regimental Combat Team. To the east, the 127th Regimental Combat Team was to operate in an area named the East Sector. A series of defensive lines in front of a main line of resistance around the airstrips covered the approaches to the vital fields. Positions on the main line of resistance were to be constructed rapidly but were to be occupied only on orders from task force headquarters. Beyond the main line of resistance there were set up a local security line, an outpost line of resistance, and an outpost security patrol line. The latter,

Chart 8: The PERSECUTION Task Force:, 4 May–28 June 1944

lying about ten miles inland, was to mark the general limits of patrolling.24

The 126th Infantry completed relief of the 163rd Infantry’s outposts and patrol bases on the west flank by 8 May. Thereafter, outpost troops were rotated from time to time, and gradually many outposts were closed out, as Japanese activity on the west ceased. On 29 May, because Japanese pressure was increasing on the east flank, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 126th Infantry, were transferred to the East Sector, and responsibility for patrolling and defending the West Sector (which had been extended in mid-May to the eastern edge of Tadji Fighter Strip) passed to the 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry. Patrolling by all elements of the 126th Infantry in the West Sector accounted for a few Japanese killed, found dead along inland trails, or captured.25

On 10 June boundaries between various elements of the PERSECUTION Task Force were again changed and redispositions were effected. A new defensive area, designated the Center Sector, was established between the West and East Sectors to cover the ground between the eastern edge of the Tadji airstrips to a line running southwestward inland from Pro. The new sector became the responsibility of the 128th Infantry, while the 126th Infantry retained control in the West Sector and the 127th continued operations in the East Sector. At the same time, the main line of resistance was drawn in toward the airfields from a previous eastern extension along the Nigia River, and the earlier inland defensive lines were either abolished or withdrawn. Troops of the West and Center Sectors continued patrolling in the areas for which they were responsible. Only a few enemy stragglers were encountered, and no signs of organized Japanese activity were discovered in those sectors.26

East Sector Troops Meet the Enemy

Col. Merle H. Howe, commanding the 127th Infantry, was assigned to the command of the East Sector on 6 May. His missions were to maintain contact with the enemy on the eastern flank, to discover enemy intentions, and to delay any westward movement on the part of elements of the 18th Army. He was ordered to maintain outposts and patrol bases at Anamo and Nyaparake on the coast and at Chinapelli and Afua inland. When he took over his new command, Colonel Howe had little information concerning the Japanese on the east flank beyond the fact that elements of two of the 18th Army’s three divisions had been identified far east of the Nigia River. Troops of the 20th Division had been discovered building defensive positions on the east bank of the Danmap River and elements of the 41st Division were thought to be in the same general area. Finally, air observers had discovered concentrations of Japanese troops at coastal villages between the Danmap and Wewak. There seemed to be definite indications that large elements of the 18th Army were beginning to move westward from Wewak.27

Colonel Howe subdivided his East Sector into battalion areas. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, was to maintain a reinforced

rifle company at Nyaparake and an outpost at Babiang, to the east near the mouth of the Dandriwad River. The battalion was to patrol up the Dandriwad and along the coast east to the Danmap River. The 2nd Battalion was made responsible for inland patrols to Chinapelli, Palauru, and Afua. The 3rd Battalion was to maintain permanent outposts at Anamo, near the mouth of the Driniumor River, and at Afua, six miles up that stream. Some of these dispositions were already in effect, with the Nyaparake Force on station and 2nd Battalion units operating in the Palauru area. The other dispositions were completed by mid-May.28

The Nyaparake Force, comprising Company C and elements of Company D, and commanded by Capt. Tally D. Fulmer of Company C, 127th Infantry, started patrolling to the east and inland on 7 May.29 On that day, patrols pushed across the mouth of the Dandriwad River to Babiang and Marubian. Alter clashing with a well-organized Japanese patrol, the Nyaparake Force elements withdrew to the west bank of the Dandriwad and spent the next day patrolling up that river and questioning natives concerning enemy movements. On the 8th a rifle platoon and a light machine gun section from Company A arrived to strengthen the Nyaparake Force.

The advance eastward was resumed the next day along two routes beyond Babiang. One was the coastal trail and the other the “Old German Road,” a name presumably referring to the days of German occupation of this part of New Guinea before World War I. The Old German Road paralleled the coastal track at a distance of about 300 yards inland. Supported by Seventh Fleet PTs based at Aitape, Nyaparake Force patrols pushed almost 5,000 yards east of the Dandriwad during the day, encountering some resistance along both routes. At dusk all patrols retired to Babiang, and Captain Fulmer re-examined his situation in the light of information obtained during the day. Large enemy groups had been reported to the west of Nyaparake at Yakamul and even as far distant as the Driniumor River, over halfway back to the Tadji perimeter. To the east, Japanese opposition gave every indication of increasing. Finally, it appeared that the Nyaparake Force was being outflanked to the south. Reports had come in that enemy parties were moving along the foothills of the Torricelli Mountains immediately south of the main inland east-west trail, which crossed the Dandriwad and Drindaria Rivers about four miles upstream.

Captain Fulmer strengthened the outpost at Charov, up the Drindaria, in order to keep closer watch on the enemy reported south of that village. At the same time he requested that aircraft strafe the coastal trail and the Old German Road east of Babiang before any further attempt to advance eastward was made. Colonel Howe agreed to request the air support mission, and he ordered the Nyaparake Force to continue pushing eastward after the air strike was completed.

Eight P-40’s of No. 78 Wing, Royal Australian Air Force, bombed and strafed the two roads east of Babiang at 1130 on 10 May. Marubian, thought to be a Japanese assembly point, was also attacked. After the air strikes Captain Fulmer sent the 1st Platoon, Company C, forward from Babiang

while the 3rd Platoon moved on to take Marubian without opposition. A defensive perimeter was set up around Marubian and an ambush was established on the Old German Road south of that village. No contacts were made with the enemy during the day. The advance continued on the 11th and the two forward platoons had reached a point about two miles beyond Marubian by early afternoon when they were halted by Japanese machine gun and small arms fire. The 3rd Platoon, on the coastal trail, pulled back about six hundred yards from the point of contact and watched a party of about fifty-five well-equipped Japanese proceed southwestward off the trail and disappear inland. The 3rd Platoon dug in for the night on the beach, while the 1st Platoon, on the Old German Road, returned to Marubian.

Captain Fulmer decided to move the rest of Company C, 127th Infantry, to Marubian on 12 May. Since this would practically denude the base at Nyaparake of combat troops, the Charov outpost was ordered to return to the base village. These redispositions were accomplished during the morning of the 12th, and the advance eastward beyond Marubian was resumed about 1300 the same day.

The 3rd Platoon of Company C, in the lead, soon encountered rifle and machine gun fire from Japanese positions at a stream-crossing near which the advance had stopped the previous afternoon. In an attempt to outflank the Japanese, the 1st Platoon moved inland about 300 yards and into line south of the 3rd. This maneuver led the 1st Platoon into dense jungle where it was stopped by determined enemy small arms fire. Further probing of the enemy defenses proved fruitless and, as night was approaching, Captain Fulmer pulled the platoon out of action. The unit moved back to the beach and dug in about 600 yards west of the stream crossing, where the 3rd Platoon had already set up defenses.

About 1100 on the 13th the 2nd Platoon, with a section of 81-mm. mortars and another of .50-caliber machine guns attached, arrived in the forward area. The riflemen of the 2nd and 3rd Platoons then joined forces and pushed on down the coast through the scene of the previous afternoon’s encounter until held up at another stream by new enemy defenses. The 1st Platoon remained behind to protect the mortars and machine guns. Scouts having reported that the Japanese were firmly entrenched at the new crossing, Captain Fulmer used his heavy weapons to soften the opposition. The 81-mm. mortars and the .50-caliber machine guns fired for about twenty minutes on the enemy defenses, and a section of 60-mm. mortars joined in the last ten minutes of the barrage. Under cover of this fire the 2nd and 3rd Platoons formed along the west bank of the small stream on a front extending 300 yards inland. The 3rd Platoon was on the beach and the 2nd on the right. At 1400, as preparation fire ceased, the two platoons started eastward. The 3rd crossed the small creek near the mouth without difficulty and pushed eastward nearly 500 yards before encountering any resistance.

The situation in the 2nd Platoon’s sector was quite different. There the ground was covered with sago palms, underbrush, and heavy jungle growth which limited visibility to five or ten yards. The platoon ran into concentrated rifle and machine gun fire immediately after starting its attack and was unable to force a crossing of the small stream. The platoon leader disengaged his force and tried to cross the creek farther inland. But the enemy refused his left flank

and the maneuver failed. Because the dense rain forest masked their fires, mortars and heavy machine guns could not support further advances in the inland sector. Captain Fulmer therefore pulled the platoon out of action on the right flank, drew it back to the beach, and sent it across the stream along the route taken by the 3rd Platoon. After crossing the creek and drawing abreast of the 3rd Platoon, the 2nd Platoon again attacked in a southeasterly direction.

The unit overran a small Japanese supply dump and aid station and advanced 50–100 yards inland but was again pinned down by enemy machine gun fire. One squad attempted to find the left of the enemy’s defenses by moving 100 yards deeper into the jungle. This effort proved futile. Since the platoon’s forward elements were now being fired on from both the south and the east and because it was again impossible to support the unit with mortar or machine gun fire, no further progress could be expected. The 3rd Platoon had been forced to halt because of the danger of being cut off by the Japanese opposing the 2nd Platoon. Captain Fulmer called off the attack to set up night defenses.

The 3rd Platoon anchored its left flank on the beach at a point about 150 yards east of the small stream, extending its lines about 50 yards inland and westward another 75 yards. The 2nd Platoon tied its left into the right of the 3rd and stretched the perimeter west to the mouth of the creek. About 200 yards beyond the eastern edge of this perimeter was an outpost of eight men, including mortar observers who were in contact with the main force by sound-powered telephone. Inside the larger perimeter were 60-mm. mortars, light machine guns, .50-caliber machine guns, and an aid station. Since the 81-mm. mortars could not obtain clearance in the area chosen for the main force, they remained under the protection of the 1st Platoon in a separate perimeter about 500 yards to the west. It seemed certain that the Japanese who had been holding up the advance during the day would attack during the night, and it was considered probable that such an attack would come through the heavy jungle at the southern, or inland, side of the main perimeter, where visibility was limited to five yards even in daylight.

The expected attack was not long in coming, although not from the direction anticipated. Shortly after 0200 on 14 May, after a short preparation by grenades, light mortars, and light machine guns, 100 to 200 Japanese of the 78th Infantry, 20th Division,30 attacked from the east against the coastal sector of the perimeter. This assault was broken up by rifle and automatic weapons fire and by lobbing mortar shells to the rear of the advancing enemy group. The Japanese disappeared into the jungle south of the narrow beach. For the next hour Captain Fulmer’s mortars placed harassing fire into suspected enemy assembly points east of the small stream. Meanwhile, the eight-man outpost reported that many small parties of Japanese were moving up the beach within 300 yards of the main perimeter and then slipping southward into the jungle. Such maneuvers seemed to presage another attack.

The second assault came about 0330, this time against the eastern and southeastern third of the defenses. The Japanese were again beaten back by small arms and mortar fire, but at 0500 they made a final effort which covered the entire eastern half of the perimeter. This last attack was quickly broken up and the Japanese quieted down.

About 0730 on the 14th, elements of Company A, 127th Infantry, began moving into the forward perimeter to reinforce Captain Fulmer’s beleaguered units. The 1st Platoon of Company C and the 81-mm. mortar section also moved forward in preparation for continuing the advance.

But now questions arose at the headquarters of the East Sector and the Persecution Task Force concerning the feasibility of further advance. Captain Fulmer was willing to continue forward if he could be reinforced by a rifle platoon of Company A, another section of heavy machine guns, and another section of 81-mm. mortars. Colonel Howe and General Gill looked on the matter from a different point of view. It would be extremely difficult, they realized, to establish an overland supply system for the advancing force and they knew that there were not enough small boats available in the Aitape area to insure over-water supply. Further advance would accomplish little unless a large base for future operations could be established well beyond the Marubian area, a project for which insufficient troops and amphibious craft were available. Moreover, the principal mission of the PERSECUTION Task Force was to protect the Tadji airfields, not to undertake large-scale offensive operations. General Gill finally decided to withdraw the Nyaparake Force’s advance elements from the Marubian area and replace it with Company A, under the command of Capt. Herman Bottcher,31 who was to carry out a holding mission on the west bank of the Dandriwad.

Withdrawal from Yakamul

On 13 May the bulk of Company A arrived at Ulau Mission, just west of the Dandriwad’s mouth.32 Company C remained at Marubian temporarily. There was little action on the 13th, but events the next day prompted General Gill to change his plans again. On the 14th Japanese patrols moved between Company C and the Dandriwad River, cutting the company’s overland line of withdrawal. At the same time strong enemy patrols harassed Company A’s positions at Ulau Mission. It seemed apparent that the American outposts could not long withstand this pressure and, therefore, both the Ulau and Marubian units were picked up by small craft on the 15th and taken westward to Nyaparake, whence the advance eastward had begun a week earlier.

During the next few days the Nyaparake Force continued patrolling, making contacts with well-organized enemy units which appeared to be more aggressive and larger than those previously encountered in the East Sector. Companies C and D returned to Tadji Plantation on 19 May and were

replaced at Nyaparake by the 32nd Reconnaissance Troop. On the same day Brig. Gen. Clarence A. Martin, Assistant Division Commander, 32nd Division, was placed in command of the East Sector and charged with the missions previously assigned to Colonel Howe—to maintain contact with and delay enemy units moving westward. General Martin was directed to move all East Sector troops except the Nyaparake Force to the west bank of the Driniumor River. The Nyaparake Force, now comprising the 32nd Reconnaissance Troop and Company A, 127th Infantry, was placed under the command of Captain Bottcher, who was transferred from Company A to the command of the reconnaissance unit. To render the force more mobile, all its heavy equipment was sent back to BLUE Beach, and the unit was instructed to retire to the Driniumor River in case Japanese pressure increased.

Captain Bottcher’s patrols soon found that enemy pressure was indeed increasing. Some Japanese patrols were active to the east while others outflanked the force to the south and, about 1850 on 22 May, attacked from the west. During the following night the Nyaparake Force fought its way out of this encirclement and retired two miles along the beach to Parakovio. The next day General Martin sent most of Company A back to Tadji and that night and during the morning of the 24th the remaining elements of the Nyaparake Force withdrew along the beach to good defensive positions at the mouth of a small creek about 3,000 yards west of Yakamul. The Japanese followed closely, occupying Yakamul and sending scouting parties westward along inland trails toward Afua and the Driniumor River.

By now it was evident that the Japanese had crossed the Drindaria in some force and it appeared that the aggressive enemy patrols had missions other than merely screening movements far to the east in the Wewak area. Deeming the Japanese movements a threat to the security of the Tadji airfields, General Gill decided to make an effort to drive the enemy’s forward units back across the Drindaria. For this purpose he assigned the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, to the East Sector. The battalion was to move forward to the Nyaparake Force’s perimeter, where Company G, 127th Infantry, was to relieve Captain Bottcher’s men. The 126th Infantry’s unit was to be supported by Battery C, 126th Field Artillery Battalion, from positions at the mouth of the Driniumor and by Battery B from the perimeter of Company G, 127th Infantry.

Company G completed the relief of the now misnamed Nyaparake Force on 31 May, and about 1100 on the same day the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, reached the forward position. Lt. Col. Cladie A. Bailey’s battalion pushed rapidly onward through Yakamul, from which the enemy withdrew hurriedly, and moved on to Parakovio against little opposition. Despite the lack of determined resistance on 31 May, it was soon to become evident that one battalion was not going to be strong enough to drive the Japanese forces already west of the Drindaria back across that stream. By this time elements of the 78th and 80th Infantry Regiments, 20th Division, had been definitely identified west of the Drindaria. Although the PERSECUTION Task Force did not yet know it, large segments of both regiments were operating in the Yakamul area, where they were supported by a few weapons of the 26th Field Artillery Regiment, 20th Division. These Japanese forces now began to strike back at the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, which, on 1 June, was able

to advance only 400 yards beyond Parakovio before it was stopped by enemy machine gun and artillery fire. At 1115 General Martin ordered the unit to retire to Yakamul. Using Yakamul as a base, the battalion was to develop the enemy situation along the Harech River from the coast to the foothills of the Torricelli Mountains, five miles inland.

During the night of 1–2 June, Japanese artillery shelled the battalion command post and enemy patrols drove in outposts which had been set up just east of Yakamul. The next morning the battalion was divided into two parts. At Yakamul was stationed Company A, Headquarters Company, and part of Company D. (Map 4) This combined group, numbering about 350 men, was put under the command of Capt. Gile A. Herrick of Company A and designated Herrick Force. The rest of the battalion, now called Bailey Force, moved south down the trail from Yakamul to patrol along the Harech River.

The Japanese soon became very active around the perimeter of Herrick Force. On 3 June the enemy launched a series of minor attacks against Company A, which was separated from the rest of Herrick Force by a small, unbridged stream about four feet deep and varying in width from ten to fifty yards. Under cover of these attacks, other Japanese groups bypassed Herrick Force to the south and on the next morning appeared west of Yakamul, between Herrick Force and the two-mile distant perimeter of Company G, 127th Infantry.

Sporadic small arms fire, intensifying during the afternoon, was directed at all parts of the Herrick Force perimeter during 4 June. About 1640 this fire was augmented by mortar and artillery shells, a development which seemed to presage an imminent Japanese infantry attack. At 1830 an enemy force of more than company strength surged out of the jungle on the southeast side of the American perimeter in an apparent attempt to drive a wedge between Company A and the rest of Herrick Force. The attack was halted by automatic weapons fire and the barrier presented by the small stream. The enemy then turned northeast from the creek against Company A. Simultaneously, a small group of enemy attacked west along the beach.

Because Company A was in danger of being surrounded, Captain Herrick ordered the unit to withdraw across the small stream to Yakamul. Since the Japanese had the stream covered with small arms and at least one well-concealed machine gun, the withdrawal was a slow process and consumed over an hour. During the movement the Japanese continued to attack and, toward the end of the hour, succeeded in overrunning some of Company A’s automatic weapons positions. Deprived of this support, most of the remaining troops retreated rapidly across the stream, leaving behind radios, mortars, machine guns, and twenty to twenty-five dead or wounded men. Most of the wounded managed to get across the stream after darkness, which was approaching at the time of the enemy’s final attack.

By 1940 the Japanese were in complete possession of the Company A position, whence they could send flanking fire toward the Yakamul perimeter. Captain Herrick ordered his men to dig in deeply. He reorganized his positions and even put some of the lightly wounded on defensive posts. Japanese ground attacks kept up until 2200, and sporadic bursts of mortar, grenade, and machine gun fire continued throughout the night.

When he learned of the situation at Yakamul, General Martin ordered Bailey Force to return to the coast and relieve Herrick

Force. Radio communication difficulties prevented delivery of this order until 2000 and it was 2200 before Colonel Bailey could organize his force in the darkness and heavy jungle and start it moving north. By that time the Japanese had a strong force blocking the trail to Yakamul. Bailey Force therefore had to swing northwest toward the perimeter of Company G, 127th Infantry, two miles west of Yakamul. After an arduous overland march through trackless, heavily jungled terrain, the leading elements of Bailey Force began straggling into Company G’s perimeter about 1130 on 5 June.

General Martin then ordered Bailey Force to move east and drive the Japanese from the Yakamul area, but this order was changed when the East Sector commander learned that Bailey Force had been marching for over thirteen hours on empty stomachs and was not yet completely assembled at Company G’s perimeter. Bailey Force was thereupon fed from Company G’s limited food supply and sent west along the coastal trail to the Driniumor River. Company G and the battery of the 126th Field Artillery Battalion which it had been protecting moved back to the Driniumor late in the afternoon.

Meanwhile, the evacuation of Herrick Force from Yakamul had also been ordered, and about 1115 on 5 June small boats arrived at Yakamul from BLUE Beach to take the beleaguered troops back to the Tadji area. Insofar as time permitted, radios, ammunition, and heavy weapons for which there was no room on the boats were destroyed. As this work was under way, a few light mortars and light machine guns kept up a steady fire on the Japanese who, now surrounding the entire perimeter, had been harassing Herrick Force since dawn. At the last possible moment, just when it seemed the Japanese were about to launch a final infantry assault, Captain Herrick ordered his men to make for the small boats on the run. The move was covered by friendly rocket and machine gun fire from an LCM standing offshore, while the Japanese took the running men under fire from the old Company A positions. So fast and well organized was the sudden race for the boats that the Japanese had no time to get all their weapons into action, and only one American was wounded during the boarding. The small craft hurriedly left the area and took Herrick Force back to BLUE Beach, where the unit was re-equipped. By 1500 the troops had rejoined the rest of the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, on the Driniumor River.

Losses of the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, during its action in the Yakamul area were 18 men killed, 75 wounded, and 8 missing. The battalion estimated that it had killed 200 to 250 Japanese and wounded many more.33

Operations Along the Driniumor

While the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, had been patrolling in the Yakamul area, elements of the 127th Infantry had been operating to the west along the Driniumor River from the coast six miles upstream to Afua.34 Until the end of May little Japanese

Map 4: Yakamul area. Reproduction of original sketch, prepared in the field by S-3, 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry

Aerial photography of the same area (bottom)

Map merged onto previous page

activity had been noted in the Anamo–Afua area, but on the 31st of the month a ration train carrying supplies up the west bank of the Driniumor to two platoons of Company L, 127th Infantry, at Afua was ambushed and forced back to the coast. Later in the day a party of Japanese estimated to be of company strength was seen crossing the Driniumor River from east to west at a point about 1,000 yards north of Afua. By dusk it appeared that at least two companies of Japanese had crossed the river near Afua and had established themselves on high, thickly jungled ground north and northwest of the village.

During the next four days elements of the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, maneuvered in fruitless attempts to drive a Japanese group, 75 to 100 strong, off a low, jungled ridge about a mile and a half north of Afua. Colonel Howe, concerned about the lack of success of his troops, early on the morning of 5 June radioed to the battalion commander: “This is the third day of maneuvering to drive the enemy off that ridge. So far today we have had no report of enemy firing a shot and we are not sure they are even there. I have been besieged with questions as to why we don’t fight the enemy. Unless we can report some accomplishment today I have no alibis to offer. Push either Fulmer [Company C] or Sawyer [Company B] in there until they draw fire.”35 During the morning Companies B and C organized a final attack and occupied the ridge, which the Japanese had abandoned during the night.

Meanwhile the PERSECUTION Task Force had decided to establish an outer defensive line along the Driniumor River. Originating in the Torricelli Mountains south of Afua, the river ran almost due north through many gorges and over steep falls to a sharp bend at Afua. From Afua to its mouth, a six-mile stretch, the river had an open bed varying from 75 to 150 yards in width. Except during tropical cloudbursts, this section of the river was not much more than knee deep. Dense rain forests extended to the river’s banks at most places, although there were some areas of thinner, brush-like vegetation. Islands, or rather high points of the wide bed, were overgrown with high canebrake or grasses, limiting visibility across the stream.

The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, dug in for 3,600 yards along the west bank of the river north from Afua, while the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, covered the same bank south from the river’s mouth about 2,000 yards. A gap of some 3,000 yards which was left between the two units was covered by patrols. On 7 June, when the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, replaced the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, on the northern portion of the defense line, a company of the former unit was strung out along some 500 yards of the gap.

On the same day Japanese activity broke out anew in the Afua area, this time about 1,300 yards west of Afua on the Afua–Palauru trail, which had now become a main supply line for troops stationed in the Afua area. Two days later the Japanese had disappeared from the Afua–Palauru trail, much to the surprise of the PERSECUTION Task Force. The task force G-2 Section decided that the enemy had withdrawn when his ration and ammunition supply was depleted, and this belief was strengthened during the next day or so when, contrary to previous sightings, all Japanese patrol movements in the Driniumor River area seemed to be from west to east.

For a couple of days some thought had been given to withdrawing the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, from Afua because of the apparent threat to the Afua–Palauru supply line, but on 10 June Headquarters, PERSECUTION Task Force, decided to leave the battalion in place. On the same day the East Sector was ordered to speed development of strong defensive positions along the Driniumor. The river line was to be held as long as possible in the face of a Japanese attack and, if forced back, the East Sector troops were to delay enemy advances in successive positions—one along the line X-ray River–Koronal Creek, about halfway to the Nigia River, and the other at the Nigia itself—before retreating to the main line of resistance around the airfields. The East Sector was to patrol east of the Driniumor in order to maintain contact with the enemy.36

After 10 June Japanese patrols in the Driniumor area became less numerous and less aggressive, but more determined enemy parties were located in hilly and heavily forested terrain along the southern branches of Niumen Creek, which lay about 3,000 yards east of the Driniumor. The Japanese appeared to be forming a counter-reconnaissance screen along Niumen Creek in order to prevent East Sector troops from finding out anything about deployments farther east. So successful were the enemy efforts that few patrols of the 127th Infantry (the 3rd Battalion replaced the 1st at Afua on 22 June) managed to push beyond Niumen Creek.

In the area covered by the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, some patrols were able to move east along the coast as far as Yakamul, but about 20 June the Japanese put more forces into the Yakamul area and stopped American patrolling in the region. In an attempt to gather additional information, one patrol was carried far down the coast to Suain Plantation. There a landing was made in a veritable hornet’s nest of Japanese activity and the few men who reached the beach were hurriedly withdrawn. No more such long-range efforts to obtain information were made.

The closing days of June found the PERSECUTION Task Force still in firm possession of the Tadji airfield area. Operations on the west flank had overcome all Japanese opposition in that region, and no more enemy activity had been encountered there after early May. On the east flank, however, the situation was far different. All elements of the PERSECUTION Task Force which had moved east of the Driniumor River had been gradually forced back until, at the end of the month, even small patrols were having difficulty operating east of the river. As the month ended, the task force’s eastern defenses were along the west bank of the Driniumor, where the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, and the 3rd Battalion, 127th Infantry, were digging in, anticipating future attacks by elements of the 18th Army. Except for minor outposts, the rest of the PERSECUTION Task Force was encamped behind the Tadji airfield main line of resistance.

Support of East Sector Operations

East Sector forces were supplied by a variety of methods. Units along the coast were supported directly by small boat from BLUE Beach or by native ration trains moving along the coastal track. Supplies to the Afua area went south from the coast along the Anamo–Afua trail or, later, over the inland track from the Tadji fields through

Chinapelli and Palauru. Wheeled transport was impracticable except along short stretches of the coastal track. In early June, when the Japanese ambushed many ration parties which attempted to reach Afua, experiments were made with air supply from the Tadji strips. Breakage and loss were heavy at first, but air supply rapidly became more successful as pilots gained experience and ground troops located good dropping grounds. A dropping ground cleared on the west bank of the Driniumor about 2,200 yards north of Afua soon became the principal source of supply for troops in the Afua area.37

Communications during operations east of the Driniumor were carried out principally by radio, but between units along the river and from the stream back to higher headquarters telephone became the principal means of communication. Keeping the telephone lines in service was a task to which much time and effort had to be devoted. The Japanese continually cut the lines, or American troops and heavy equipment accidentally broke the wires. The enemy often stationed riflemen to cover breaks in the line, thus making repair work dangerous. Usually, it was found less time consuming and less hazardous to string new wire than to attempt to find and repair breaks. As a result, miles of telephone wire soon lined the ground along the trails or was strung along the trees in the Driniumor River area and back to the Tadji perimeter.38

Before mid-June most telephone messages in the East Sector were sent “in the clear,” but evidence began to indicate that the Japanese were tapping East Sector lines. On 19 June, therefore, the PERSECUTION Task Force directed that no more clear text telephone messages be used in the East Sector. As in the case of the telephone, all radio messages, of which some concerning routine matters had been previously sent in the clear, were encoded after mid-June.39

Radio communications presented no particular problems in the coastal region, but inland radio trouble was chronic and sometimes acute. Radio range was limited, especially at night, by dense jungle and atmospheric conditions, while almost daily tropical storms originating over the Torricelli Mountains hampered both transmission and reception. At times the only way radio could be employed in the Afua area was by having artillery liaison sets transmit to artillery liaison planes flying directly overhead. There were some indications that the Japanese tried to jam East Sector radio circuits, but there was never any proof that the suspected jamming was anything more than static caused by adverse atmospheric conditions.40

Principal naval support for units in the Aitape area after the end of April was provided

Tadji Fighter Strip after 28 April

by Seventh Fleet PTs. These speedy craft devoted most of their attention to Japanese barge traffic east of Aitape, sinking or damaging so many of the enemy craft that the 18th Army units were forced to limit their westward movements to poor overland trails. One of the largest single “bags” was obtained during the night of 26–27 June when fifteen Japanese barges were sunk near Wewak. In addition to their antibarge activity, the PTs also undertook many reconnaissance missions both east and west of Aitape, and, from time to time, provided escorts or fire support for East Sector units operating east of the Driniumor. PTs also carried out many daylight patrols in co-operation with Australian aircraft based on the Tadji strips. The principal targets of these air-sea operations were Japanese coastal guns and troop concentrations along the beach between the Drindaria and Danmap Rivers.41

Close air support and other air missions requested by the PERSECUTION Task Force were carried out under the direction of No. 10 Operational Group, Royal Australian Air Force. From 24 April through 12 May this group’s combat planes comprised three P-40 squadrons of No. 78 Wing. The wing moved out of the Aitape area toward the end of May and from the period 25 May to 9 June only the 110th Reconnaissance Squadron, U.S. Fifth Air Force, was stationed at Tadji. On the 9th a squadron of Beaufighters (twin-engined fighters) of the Royal Australian Air Force’s No. 71 Wing

arrived at Tadji and by the 15th two more squadrons of the same wing, both equipped with Beauforts (twin-engined fighter-bombers), had reached Aitape. On the 22nd of the month, Headquarters, No. 10 Operational Group, left Tadji and control of air operations in the Aitape area passed to Headquarters, No. 71 Wing.

In May the Australian aircraft flew over 1,600 sorties and dropped almost fifty-seven tons of bombs of all types on ground targets from Aitape to Wewak. During June the pace of air operations was stepped up and from the 7th of that month until 6 July the two Beaufort squadrons alone flew 495 sorties and dropped about 325 tons of bombs. When more bombing than the Tadji-based Beauforts could provide was needed, A-20’s and B-25’s of the Fifth Air Force, flying first from Nadzab in eastern New Guinea and later from Hollandia, swung into action. The Australian Beauforts were also occasionally pressed into service as supply aircraft, dropping rations and ammunition to American forces along the Driniumor. Most supply missions were, however, undertaken by Fifth Air Force C-47’s from Nadzab or Hollandia or sometimes employing one of the Tadji strips as a staging base. Both Fifth Air Force and Australian planes also flew many reconnaissance missions between Aitape and Wewak. These operations, together with the bombing of coastal villages occupied by the Japanese, suspected enemy bivouac areas, bridges over the many streams between the Driniumor and Wewak, and Japanese field or antiaircraft artillery emplacements, materially assisted the East Sector in the execution of its delaying and patrolling missions.42