Chapter 9: The Seizure of Wakde Island

The seizure of the Hollandia and Aitape areas had consummated one step in the Southwest Pacific’s strategic plan for the approach to the Philippines—advancing the land-based bomber and fighter line by the seizure of air-base sites along the north coast of New Guinea. Long before Allied troops had set foot ashore at Hollandia and Aitape, General MacArthur’s planners had been looking toward the Geelvink Bay region of western Dutch New Guinea as the next air-base site objective after Hollandia. From airfields constructed on islands in Geelvink Bay, operations still farther to the northwest could be supported.1

The Sarmi–Biak Plan

The Strategic Background

The 200-mile-deep indentation that Geelvink Bay makes into the land mass of New Guinea scoops out the neck of the bird-like figure of that island. Cape D’Urville, lying over 200 miles northwest of Hollandia, is the bird’s shoulder and marks the eastern limit of Geelvink Bay. From Cape D’Urville the distance westward across the bay to Manokwari on the Vogelkop Peninsula (the bird’s head) is about 250 miles. Across the northern entrance to Geelvink Bay lie many small islands and islets. Among the Schouten Group are Biak, Soepiori, Owi, and Mios Woendi; Japen, Mios Noem, and Noemfoor lie south and west of the Schoutens. Many of the bay islands are large enough to provide airdrome sites, some of which had been developed by the Japanese. Allied attention was focused on Biak. The terrain on the southeastern shore of that island is well suited for airfields, and the Japanese had begun airdrome construction there late in 1943.

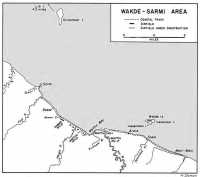

Biak Island is located about 325 miles northwest of Hollandia. On the New Guinea mainland approximately 180 miles southeast of Biak and 145 miles northwest of Hollandia lies the town of Sarmi. Prior to World War II, Sarmi was the seat of the local Netherlands East Indies government and a small commercial center. In the closing months of 1943, the Japanese began to develop in the Sarmi area supply, troop, and air bases of some importance, for the region was to be a major defensive installation on Japan’s withdrawing strategic main line of resistance. Six miles east of Sarmi the enemy constructed Sawar Drome, which was operational by 1 April 1944. (Map 9) Three miles still farther east, on the shores of Maffin Bay, the Japanese hastily began constructing another airstrip early in 1944. About twenty miles east of Sarmi and approximately two miles offshore lie the Wakde Islands, Insoemoar and Insoemanai.

Map 9: Wakde–Sarmi Area

On the former, designated throughout the operation as Wakde Island, the Japanese had completed an excellent airfield by June 1943.2

Although General MacArthur’s planners had given up thoughts of seizing Wakde Island as an adjunct to the Hollandia operation, they did not drop the Wakde–Sarmi area from consideration. First, the area was apparently capable of development into a major air base for the support of subsequent operations. Second, as more information from various intelligence sources became available at General Headquarters concerning Japanese airdrome development, troop dispositions, and supply concentrations at Wakde–Sarmi, the area began to acquire a threatening aspect. It was a base from which the enemy could not only endanger the success of the Hollandia operation, but also imperil Allied progress into the Geelvink

Bay area. Indeed, the Allied Air Forces considered that an early seizure of the Wakde–Sarmi region after the capture of Hollandia was a prerequisite to continuing the drive toward the Philippines.3

Finally, when in March 1944 the Joint Chiefs of Staff had instructed General MacArthur to provide air support for operations in the Central Pacific Area,4 occupation of both the Wakde–Sarmi area and Biak Island assumed importance in inter-theater strategy. From air bases in northwest New Guinea the Allied Air Forces could provide support for the Central Pacific’s Mariana and Palau operations by helping to neutralize enemy bases in the western Carolines and keeping under surveillance enemy shipping and fleet units in the waters north and northwest of the Vogelkop Peninsula. In addition, an early advance by Southwest Pacific forces to the Wakde–Sarmi–Biak region would keep Japanese attention diverted from impending operations in Admiral Nimitz’ area of responsibility.5

Prior to May 1944 the only good heavy bomber bases in the Southwest Pacific’s forward area were on the Admiralty Islands and at Nadzab in eastern New Guinea. Both these bases were too far south or east to permit execution of an effective bombing and reconnaissance program to support either the Central Pacific’s advances or the Southwest Pacific’s drive to the Philippines. It had been expected that the newly won Hollandia fields would furnish excellent bomber bases farther west and north, but the terrain and weather at Hollandia made it impossible to provide airfields suitable for extensive employment by heavy bombers without a great deal more engineering work than had been anticipated. The necessary air support missions therefore became contingent upon rapid development of heavy bomber fields in the Wakde–Sarmi–Biak region.6

The First Wakde–Sarmi–Biak Plan.

Even before plans for Hollandia–Aitape had been completed, General MacArthur had warned principal subordinate headquarters in the Southwest Pacific Area that the operation might soon be extended to include the seizure of the Wakde–Sarmi area. Since Admiral Nimitz had not then made any specific requests for Southwest Pacific air support of his operations, the objectives of the Wakde–Sarmi undertaking at first had principally local applications. Japanese forces at Sarmi were to be prevented from interfering with construction at Hollandia, and bases were to be developed in the Sarmi area to support subsequent Southwest Pacific operations to the northwest.7

General MacArthur’s G-2 Section expected that the Allied seizure of Hollandia and Aitape would stir the Japanese into efforts to reinforce western New Guinea. It was estimated that one enemy division was

spread between Sarmi and Biak, and it was believed that two more divisions were scheduled for early movement to New Guinea. Allowed freedom of movement, such enemy reinforcements could become a strong threat to the success of advances westward beyond Hollandia. It therefore seemed of utmost urgency that the Wakde–Sarmi area be seized and cleared of enemy forces as soon as possible.

The G-2 Section estimated that about 6,500 Japanese troops were stationed at Wakde–Sarmi. Of these, some 4,000 were considered combat elements of the 36th Division, probably including the entire 224th Infantry and possibly a battalion of the 223rd Infantry. The 222nd Infantry of the same division was thought to be on Biak Island. Within 350 miles west of Sarmi (considered easy reinforcing distance), there were estimated to be approximately 14,000 enemy troops, of whom 7,000 were believed members of combat units. These forces were thought to be concentrated at Manokwari, on Biak, and on other islands in Geelvink Bay. The exact dispositions of the Japanese at Wakde–Sarmi could not be foretold, but it was considered probable that most were concentrated at Sarmi and around the three airfields in the vicinity.8

Basing his decision on the estimated Japanese strength in the Wakde–Sarmi area and on the possibility that the enemy might reinforce the area before the Allies could land there, General MacArthur decided that a full infantry division should be sent against Wakde–Sarmi. One regimental combat team was to land near the town of Sarmi, another on the mainland opposite Wakde Island, and the third was to be in reserve. The unit landing near Wakde was to seize that island by a shore-to-shore maneuver after securing the initial mainland beachhead.

General Krueger, who was to direct the operation, planned to employ either the 6th or 31st Infantry Division. Both of these units had recently arrived in the theater, and neither had combat experience. This plan was opposed by General MacArthur, who considered it necessary to withdraw the 24th, the 32nd, or the 41st Division from its commitment to Hollandia–Aitape. The theater commander felt that it would be impossible to stage and supply the Wakde–Sarmi operation from rear areas, since all available large amphibious and cargo ships were needed to support the Hollandia–Aitape operation and build up the air and supply base at Hollandia. Thus, an early advance to Wakde–Sarmi was contingent upon combat developments at Hollandia and Aitape. If none of the divisions committed to the latter operations could be relieved, Wakde–Sarmi might have to be postponed until at least mid-June.

With this information at hand General Krueger decided to assign the 32nd Division to Wakde–Sarmi. One regimental combat team of the division was scheduled for early arrival at Aitape and the remainder of the unit was at Saidor, in eastern New Guinea. However, the unexpected weakness of Japanese opposition at Hollandia, the shortage of shipping, and the lack of adequate staging facilities at Saidor combined to prompt a change. The 41st Division, with one regimental combat team at Aitape and the remaining

units at Hollandia, was substituted for the 32nd.9

Setting D Day for Wakde–Sarmi depended not only on combat developments at Hollandia and Aitape but also upon the availability of naval and air support. Naval escort vessels and sufficient amphibious craft were expected to be on hand by 30 April. Air support was not so easily obtained. The carriers which were to support Hollandia–Aitape had to leave the Southwest Pacific within a very few days after that invasion. Wakde–Sarmi was too far from eastern New Guinea air bases to permit proper land-based air support. For these two reasons, the advance to Wakde–Sarmi had to await establishment of land-based air units on the Hollandia fields. It was expected that these fields would be operational by 12 May. To allow for unforeseen circumstances, the target date for Wakde–Sarmi was set for three days later, 15 May. This date was set by General MacArthur in operations instructions published on 27 April.10 The target date and selection of forces for Biak were left for later determination, but a move to Biak early in June was contemplated.

The Plan is Changed

By the first week in May preparations for Wakde–Sarmi were rapidly approaching completion. The 41st Division’s three combat teams had been relieved at Hollandia and Aitape and were busily loading supplies. Naval and amphibious organization had been settled, and shipping and supplies were being gathered at the two staging areas. The Allied Air Forces had begun preassault bombardments of the targets, and all units participating in the operation were putting finishing touches on their tactical plans. On 4 May, however, Admiral Barbey, who was responsible for the coordination of naval planning, started a chain of events which precipitated a broad change in the Wakde–Sarmi plan.

Admiral Barbey proposed that D Day be postponed until 21 May and gave two reasons for the postponement. First, tides would be higher in the Wakde area on the 21st than on the 15th. Second, postponement would allow orderly and complete preparations to be made. Congestion was severe at the Hollandia beaches, where the bulk of the 41st Division was to stage. Lack of lighterage and beach space, combined with an inadequate road net, hampered unloading of equipment, supplies, and troops which were pouring into the Hollandia area. The arrival of such supplies and units, some of which had to be reloaded for Wakde–Sarmi, seriously interfered with mounting the 41st Division.11

General Krueger, responsible for coordinating all planning for the Wakde–Sarmi operation, immediately called a conference of representatives of ALAMO Force, Allied Air Forces, and Allied Naval Forces to discuss Admiral Barbey’s proposal. The conferees, meeting on 6 May, decided that the operation could be started no earlier than 16 May (a day later than the date already set) but that unless important strategic considerations

dictated otherwise, 21 May would be much preferable. Such a delay would considerably ease the congestion at Hollandia and give the Allied Air Forces time for many more strikes against the target area. General Krueger immediately informed General MacArthur of the recommendations made at the conference.12

General MacArthur, who approved the proposed delay, investigated the problem more fully and on 6 May recommended that the entire concept of the Wakde–Sarmi operation be recast. Interpretation of new aerial photographs of the coastal area from Sarmi eastward to Wakde indicated that ground conditions on the mainland in that region were not suited to construction of airdromes adequate for heavy bomber operations. General MacArthur therefore decided that the Sarmi portion of the operation should be canceled. Wakde Island would be seized as planned and aircraft would be sent there as soon as possible. Within eight or ten days after the capture of Wakde, or as soon as the airfield there was repaired, Allied forces would advance to Biak, where more suitable airdrome sites were known to exist. The move to Biak would be covered by Wakde–based fighters and bombers.13

To arrange the details under this revised concept, a new planning conference was held at ALAMO Force headquarters on 9 May. Conferees included General MacArthur’s chief of staff; the commanders of ALAMO Force, Allied Air Forces, and Allied Naval Forces; and representatives of the Advanced Echelon, Fifth Air Force, and the VII Amphibious Force. After considerable discussion the conferees decided that the proposed Wakde–Biak operation could be carried out. The forces originally scheduled to take Wakde–Sarmi were believed sufficient. One regimental combat team was considered strong enough for the Wakde phase and it was expected that the rest of the 41st Division could seize the airdrome areas on Biak.

In order to assure that the Wakde field would be ready to base aircraft supporting the Biak operation, it was determined that an interval of ten days would be necessary between the two phases of the new operation. Such an interval was also dictated by logistic problems, since many of the assault ships used for Wakde would also be needed in the Biak phase, and a ten-day interval would be necessary for the turnaround and reloading of these vessels. Finally, a number of engineer and air force organizations were scheduled to arrive at Hollandia on 12 May, either for employment there or to be staged for Wakde–Sarmi. The shipping bringing these units to Hollandia was needed to support the Wakde phase of the new operation, which could not begin until the vessels were reloaded. This reloading could not be accomplished quickly, for beach congestion at Hollandia remained a major problem. It was therefore proposed that the Wakde landings be postponed still another day. On the other hand, the strategic urgency of providing the Central Pacific with land-based air support for the invasion of the Marianas was by now becoming evident and a delay in the target date for Biak might threaten the success of Admiral Nimitz’s undertakings. After consideration of all these problems, the conferees finally decided that D Day for

Wakde should be set for 17 May and Z Day for Biak for 27 May.14

The Wakde Plan

On 10 May General MacArthur approved the proposed dates for the new Wakde–Biak operation.15 All units concerned immediately began revising their Wakde–Sarmi plans—plans which proved remarkably flexible. New loading and staging schedules had to be drawn up, and some changes in organization, command, and troop assignments were found necessary. Despite the fact that some confusion inevitably resulted from the sudden change in the original concept of operations, all major headquarters were able to perfect new plans within a few days.

The Amphibious Plan

Under the revised concept the ground forces moving into the Wakde–Sarmi area were to limit operations to the occupation and defense of Wakde Island and the adjacent mainland. The ground mission was primarily defensive in nature—to prevent Japanese interference with construction activities on Wakde and air operations from it. There was one additional task. The Allied Air Forces desired that radar warning stations be established in the Wakde area. For this purpose, Liki and Niroemoar Islands, about fifteen miles off Sarmi, were to be seized.

The nucleus of the force moving to Wakde was the 163rd Regimental Combat Team of the 41st Division. For the operation the reinforced combat team was designated the TORNADO Task Force, to be commanded by Brig. Gen. Jens A. Doe who had directed the operations of the 163rd at Aitape. The TORNADO Task Force was to start landing on the mainland opposite Wakde Island at 0715 on 17 May. The seizure of Wakde Island was to be undertaken on 18 May, and the capture of Liki and Niroemoar on the 19th.16

Planners devoted much time to the selection of a landing beach for the TORNADO Task Force. Though the principal objective of the task force was Wakde, that island was too small and its beaches were too limited to permit the landing of a reinforced regimental combat team. Furthermore, a landing on Wakde might be subjected to fire from hidden enemy artillery on the mainland. Landing the task force on the mainland would largely eliminate any danger of beach congestion, and at the same time the Japanese would be denied positions from which they could shell Allied forces on Wakde. Conversely, the TORNADO Task Force could secure positions on the mainland from which its own artillery could hit Japanese defenses on Wakde.

It was decided that a landing at Toem, on the mainland directly opposite Wakde, would not be sensible. There the landing craft and cargo ships would be subjected to even small-caliber fire from Wakde. In such

restricted waters the enemy could place enfilade fire on the ships, but in more open waters to the west naval fire support ships and amphibious vessels would have freedom of movement and could maneuver to neutralize both Wakde and the Toem area while the TORNADO Task Force moved ashore and set up its artillery. After consideration of all these factors, it was finally decided that the initial beachhead would be at Arare, a native settlement on the coast about three miles west of Toem and four and one-half miles southwest of Wakde Island.17

The 163rd Infantry, in column of battalions, the 3rd Battalion leading, was to initiate the assault at Arare. LCVPs, furnished by Engineer Special Brigades and manned by Company B, 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, were to take ashore the first four waves, which were to land at five-minute intervals beginning at H Hour. The four waves were to contain 8 LCVPs each, the fifth wave 4 LCMs, and the next two waves 6 LCIs each. LSTs were to move in to the beach beginning at H plus 60 minutes.18

The 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, was to take up positions on the right (west) flank of the Arare beachhead. The 1st and 2nd Battalions, following the 3rd ashore, were to move east along the coast from Arare, 6,000 yards to Tementoe Creek and prevent Japanese interference from the east. One rifle company of the 3rd Battalion was to move west from Arare to the Tor River, another 6,000 yards distant.

As soon as the initial beachhead was secured, a reconnaissance of Insoemanai Island, about 3,500 yards offshore, was to be undertaken. If that islet proved unoccupied, a Provisional Groupment of heavy weapons was to be transported to it. The Provisional Groupment consisted of Company B, 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion (4.2-inch mortars), and all the 81-mm. mortars, .50 caliber machine guns, and .30 caliber heavy machine guns available to the 163rd Infantry. As soon as these weapons were emplaced, they would begin firing on Wakde Island.

The artillery of the TORNADO Task Force included the 167th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers), which was part of the 163rd Regimental Combat Team; the 218th Field Artillery (155-mm. howitzers); and the Cannon Company, 163rd Infantry (105-mm. howitzers, M3). These units were to operate under the control of Headquarters, 191st Field Artillery Group, the commanding officer of which, Col. George M. Williamson, Jr., was also task force artillery officer. Following the infantry ashore as rapidly as the tactical situation permitted, the artillery was to set up near Arare to provide support for the ground troops moving toward the flanks of the beachhead and for the shore-to-shore movement against Wakde Island on D plus 1.

The latter maneuver was to be undertaken by the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry. The Wakde assault was to be covered not only by the task force artillery but also by the Provisional Groupment on Insoemanai and by naval fire support ships. The landing was scheduled to begin at 0830, 18 May.19

The naval organization for the Wakde–Biak operation centered on the Naval Attack Force, commanded by Rear Adm. William M. Fechteler (USN).20 The admiral delegated responsibility for the Wakde phase of the operation to Capt. Albert G. Noble, (USN), whose command was designated the Eastern Attack Group. Captain Noble divided his fire support ships into three groups: Fire Support Group A (two heavy cruisers and four destroyers), Fire Support Group B (three light cruisers and six destroyers), and Fire Support Group C (ten destroyers). These ships were to begin firing on assigned targets at H minus 45 minutes and were to continue bombardment until H minus 3. The bulk of the D Day fire was to be aimed at Sawar and Maffin Dromes, west of the landing beach. No resistance was expected at the beach and a light bombardment to be directed on it was purely precautionary. Some fire support ships were assigned counterbattery missions and others were to aim their shells at Wakde and Insoemanai Islands.

Other ships assigned to participate in the landing phase were 3 submarine chasers, 2 destroyer-escorts, 4 mine sweepers, 2 rocket-equipped submarine chasers, and 3 rocket-equipped LCIs. Rocket fire was to begin at H minus 3 minutes and was to be directed principally against the beachhead area. At H minus 1, all fire on the beach was to cease and the landing craft were to make their final dash to the shore. After the landing, the fire support ships were to shift bombardment to targets on the beach flanks and were to be prepared to deliver call fire upon request from the troops ashore. The landing on Insoemanai was to be supported by two LCI(G)’s and two destroyers. Throughout the night of 17–18 May, cruisers and destroyers were to bombard Wakde and on the morning of the 18th they and the rocket-equipped vessels were to support the assault on that island. On the 19th a few destroyers were to support the landings on Liki and Niroemoar Islands.21

The Air Support Plan

Prior to 17 May the Allied Air Forces was to undertake intensive bombardment of the Wakde–Sarmi area and other Japanese installations along the north coast of New Guinea. Special attention was to be given enemy fields east of the Vogelkop Peninsula and on Biak Island. Japanese waterborne supply and reinforcement movements in the Geelvink Bay area were to be stopped insofar as weather, time, and the availability of aircraft permitted. The surface convoys moving toward the target were to be furnished air cover, and close support during the landings was also to be made available.

Most of these missions were assigned to the U.S. Fifth Air Force, but other elements of the Allied Air Forces had their own tasks in support of the operation. The XIII Air Task Force was to take part in the Wakde–Biak operation by assuming responsibility for many air activities in eastern New Guinea and New Britain in order to relieve Fifth Air Force units for movement forward to Hollandia and, ultimately, to Wakde Island. The XIII Air Task Force was also to bomb Japanese installations on such Caroline Islands as were within range of the unit’s new base on the Admiralties in order

to forestall enemy interference with the Wakde–Biak operation from the north. The task force’s long-range bombers were to supplement Fifth Air Force sorties against Japanese fields in western New Guinea, including those at Wakde, Sarmi, and Biak.

Australian air units also had important support missions and were to strike all Japanese airfields in northwestern New Guinea (west of and including Noemfoor Island) within range of the bomber bases at Darwin, Australia. While the Fifth Air Force was primarily responsible for the enemy fields east of Noemfoor, Fifth Air Force bombers were also to participate in the strikes on the more westerly targets. Insofar as range, weather, and time permitted, Australian bombers, aided by a Dutch squadron of B-25’s, were to neutralize enemy air bases on the Arafura Sea islands and on other islands of the Indies southwest of the Vogelkop.22

On D minus 1 Fifth Air Force bombers were to attempt detonation of possible land mines on the mainland beach and subsurfaces mines in the waters surrounding Wakde. On the morning of D Day there was to be additional bombing west of the landing area, but there was to be no bombing or strafing of the beach immediately before the assault.23 Fighters were to be on air alert, weather permitting, over the Wakde area from first light to dusk on D Day. During part of the day A-20’s would also be on alert over the area and were to strike Wakde. Such daily cover was to continue until aircraft could use the Wakde strip.24

Supply and Reinforcement

By evening on D plus 2, considered the end of the assault phase, the TORNADO Task Force on Wakde and the mainland opposite would comprise some 9,700 troops. Of this number, about 7,000 were to be landed at Arare on D Day. The ships for the D-Day echelon included 2 APAs, 12 LCIs, and 8 LSTs. The first Reinforcement Group, scheduled to arrive on D plus 1, was to bring forward engineers and other service troops aboard eight additional LSTs. After D plus 2, the task force was to be built up by air force and ground combat or service units until it numbered close to 22,500 men.25

Units moving to Arare on D Day and D plus 1 were to carry with them ten days’ supply of rations, clothing, unit equipment, fuels, and lubricants. Engineer construction matériel was to be shipped in sufficient quantities to assure a quick start on airfield repairs and preparation of roads, bivouacs, and storage areas. The amounts and types of such matériel were left to the discretion of the task force commander. Ammunition

carried by assault units was to consist of six units of fire for 4.2-inch mortars and three units of fire for all other weapons, both infantry and artillery. Additional ammunition for field artillery units and for the 4.2-inch mortars was to be shipped separately to arrive on D plus 1 and D plus 2. All troops arriving after D plus 2 were to bring with them thirty days’ supply of rations, unit equipment, clothing, fuels, lubricants, and three units of fire for all weapons.26

Initial responsibility for the transportation of troops and supplies to the Wakde area rested with the Allied Naval Forces which exercised this responsibility through the VII Amphibious Force and the Eastern Attack Group. The Services of Supply was to relieve the naval forces of this duty as quickly as possible after D Day. The target date for the transfer of responsibility was set for D plus 11, 28 May.27

ALAMO Force Reserve for Wakde–Biak was set up to support either phase of the operation, and there were two reserve units. One was the 128th Regimental Combat Team of the 32nd Division, which was to stage at Aitape should its services be required in the forward area. The other was the 158th Regimental Combat Team, an organization not part of any division. This combat team, which was built around the separate 158th Infantry, was to move from eastern New Guinea to the Wakde area on or about 23 May, ready to reinforce either the TORNADO Task Force or units on Biak.

The nucleus of the force scheduled to invade Biak was the 41st Infantry Division, less the 163rd Regimental Combat Team at Wakde. The most logical reinforcing unit for Biak would be the 163rd. Tentative plans were therefore made to have the LCIs of the Biak assault convoy return thence to Wakde, pick up the 163rd in the latter area, and move the unit forward to Biak on or about 3 June. The plan to move the 158th Regimental Combat Team to Wakde by 23 May was evolved in order to assure the availability of the 163rd for Biak.28

The TORNADO Task Force had no specific separate reserve units set aside for D Day. However, the 27th Engineer Battalion (C), scheduled to come ashore in the fifth wave at Arare, was to be prepared to assemble in task force reserve in addition to its other duties. The 1st Platoon, 603rd Tank Company, though part of the force scheduled to invade Wakde Island on D plus 1, would also be available as a reserve on D Day. Finally, the three rifle companies of the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry, were not assigned any combat missions on D Day. They were to assemble near Toem in preparation for the next day’s assault on Wakde but could also be considered an emergency reserve for mainland operations.29

Airfield Construction Problems

Even before the Wakde–Biak plans were completed, increasing importance was being given to the early capture and repair of the Wakde airstrip. The principal mission of the airdrome construction units due to arrive at Wakde on D plus 1 was to prepare rapidly facilities on that island to accommodate one fighter group. Initially it was planned that facilities would also be constructed on

Wakde to permit staging (as opposed to basing) an additional fighter group, one flight of night fighters, and a reconnaissance squadron. Such facilities were thought to be the minimum necessary to support the Biak operation.30

While these plans were being formulated, new information was received at General Headquarters indicating that the Japanese might react strongly, with both air and naval forces, to an invasion of Biak. Therefore the Allied Air Forces recommended changing the Wakde airdrome to permit one P-47 fighter group and one Navy PB4Y patrol bomber squadron31 to be permanently based on the island. General Kenney, the theater air commander, also considered it necessary to extend staging facilities on Wakde to include space for one B-25 tactical reconnaissance squadron, another fighter group, and two B-24 heavy bomber groups. Plans had to be made to improve the Wakde strip to meet the new requirements by 25 May, two days before landings were to be made on Biak.32

A few days before the Wakde operation began, Admiral Nimitz requested air support from the Southwest Pacific for his impending operations against the Mariana Islands. The mission which Admiral Nimitz desired to be initiated immediately was long-range reconnaissance from Hollandia for a distance of 800 miles over the Hollandia–Halmaheras–Yap triangle. He further requested that the Allied Air Forces undertake to neutralize enemy airdromes on the Palau, Yap, and Woleai Islands of the Caroline chain from the 9th through the 15th of June in order to cover the approach of Central Pacific convoys to the Marianas.33

Since the Hollandia area could not meet requirements for extensive operations of B-24’s and PB4Y’s, General Kenney decided that the Wakde Island strip would have to bear much of the bombing and reconnaissance load. Air operations from Wakde would have to begin not later than 2 June, in order that the missions Admiral Nimitz requested might become routine to Japanese intelligence well before Central Pacific convoys set out for the Marianas.

To fit the Wakde strip into these plans, staging facilities would have to be constructed on that island beyond the extent deemed necessary by General Kenney for the proper support of the Biak operation. Provision also had to be made for shipping forward to Wakde additional fuels and lubricants, together with bombs and other aircraft ammunition. After much discussion, the headquarters concerned with the development of an air base on Wakde decided that most of the necessary improvements could be made on the island by 2 June. A judicious juggling of ship loading and sailing schedules also made it possible to send the necessary equipment and ammunition forward to Wakde by the same date. Fulfillment of all Admiral Nimitz’ requests would, however, have to await the capture and repair of airdromes on Biak Island. In the meantime it remained of the utmost importance

that the Wakde strip be seized and repaired quickly.34

Preparations for the Capture of Wakde Island

General Doe and his TORNADO Force planning staff learned of the change from the Wakde–Sarmi plan to the Wakde–Biak concept on 10 May. The planners returned to Aitape, where the bulk of the TORNADO Task Force was to stage, on 12 May after a conference at ALAMO Force headquarters. Although the new Wakde–Biak plan delayed the date for the landings in the Wakde area from the 15th to the 17th of May, there was still scant time for perfecting new plans, revising orders and issuing new ones, and changing loading instructions and schedules.

A series of untoward circumstances hampered loading. LSTs on which TORNADO Task Force units at Aitape were to be loaded were some eight hours late reaching the staging point. When these vessels finally reached Aitape, adverse surf conditions and congestion on the shore prevented their beaching until late in the afternoon of 13 May, and loading was delayed another twelve hours. There was also some trouble about units scheduled to take part in the Wakde operation. The Shore Battalion, 533rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, an important element of the TORNADO Task Force, did not arrive at Aitape until the afternoon of 12 May. The battalion and its equipment could not be unloaded from the ships which had brought it to BLUE Beach from eastern New Guinea and be reloaded on LSTs of the Wakde convoy in time for the departure of the task force from Aitape, scheduled for no later than midnight on 14 May. In view of these logistic difficulties, General Doe recommended to ALAMO Force that the Wakde operation be delayed at least another forty-eight hours.35

Captain Noble, Eastern Attack Group commander, had wanted the Aitape vessels to depart that staging point by 1800 on 14 May. ALAMO Force had already persuaded him to postpone the departure to midnight, but would not request the further delay proposed by General Doe. The task force commander was therefore forced to drive his troops to the limit of their endurance in order to get the loading finished on time. He solved the problem of the Shore Battalion, 533rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, by substituting for that unit the Shore Battalion, 593rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, which was already stationed at Aitape.36

By working throughout the night of 13–14 May, all units of the Aitape convoy were loaded by about 2200 on the latter day. The vessels left for Hollandia at 0100 on 15 May, arriving at Humboldt Bay about 1000. At Humboldt Bay the rest of the TORNADO Task Force’s assault echelon (mostly service troops) was quickly loaded, despite chronic beach congestion in the area. About 0200 on the 16th the LSTs and their escorts left Humboldt Bay for Tanahmerah Bay, reaching their destination about daylight. The LST section spent the rest of the

day at Tanahmerah Bay and moved out for Wakde during darkness of the night 16–17 May. The APAs and LCIs with their escorts left Humboldt Bay for Wakde about 1900 on the 16th.

The cruisers and destroyers of Covering Forces A and B did not assemble with the rest of the convoy in the Hollandia area. Instead, in order to escape detection by Japanese air patrols, they rendezvoused off the Admiralty Islands on 15 May. During the night of 16–17 May the two covering forces maintained contact with the assault shipping by radar. At dawn on the 17th the fire support ships closed with the rest of the convoy and took up their firing positions off Arare and Wakde Island.37

Dawn brought with it a cold drizzle, but the fire support ships had no difficulty picking up their landmarks and the naval fire started on schedule.38 Designated targets were well covered and there was no answering fire from Japanese shore-based weapons. Troops aboard the assault ships arose early, breakfasted quickly, and by 0530 had begun loading on their assigned landing craft. The sea remained calm and the rain gave way to the sun shortly after dawn. Men of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, transferred from the APAs which had brought them from Aitape to the eight LCVPs of the first wave. The beach was clearly visible and its limits had been marked by colored smoke grenades dropped by cruiser-based seaplanes of the fire support units. Landing craft carrying the leading wave, Company I, 163rd Infantry, touched the shore near Arare on schedule at 0715. Succeeding waves formed rapidly and beached without difficulty. There was no Japanese opposition.

The mainland area of immediate concern to the TORNADO Task Force extended west from Arare about four miles to the Tor River, and east an almost equal distance to Tementoe Creek. Between these two streams is a hard, sandy beach about 250 yards deep, unbroken except by one small creek.39 Behind this coastal strand there is a low, somewhat swampy area, covered with jungle undergrowth and patches of dense rain forest. This low area extends from two and one-half to six miles inland to foothills of mountain ranges. The men of the TORNADO Task Force found a coastal track, which almost reached the dignity of a road at some points, running along the beach. There is no high ground near Arare. The main drainage system of the area is the Tor River, which, together with Tementoe Creek, offered natural obstacles to lateral movement.

Upon landing, the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, fanned out along the shore and quickly secured the Arare beachhead area. Company A of the 116th Engineer Battalion and the 27th Engineers were the next units ashore, and they were followed about 0735 by the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 163rd Infantry. The 2nd Battalion, passing through the 3rd, immediately moved eastward toward Tementoe Creek. By 0930,

brig. Gen. Jens A. Doe and his aide, 1st Lt. Rob D. Trimble, of the 41st Infantry Division, during the landing at Arare

against no opposition, Company G had secured Toem, about 4,500 yards east of Arare. At 1010 the battalion commander, Maj. Robert L. Irving, reported that his men had reached their D Day objective, the west bank of Tementoe Creek. The 1st Battalion, under Maj. Leonard A. Wing, followed the 2nd east along the coastal road to Toem. At the latter village the 1st Battalion established a bivouac and began preparing for its attack on Wakde Island the next day.

The 3rd Battalion, under Maj. Garlyn Munkres,40 dispatched Company L west to the Tor River. The company found a good foot bridge over the small creek between the Tor and Arare and, moving on against only scattered rifle fire, reached the Tor late in the morning. During the afternoon other elements of the 3rd Battalion reached the river. The bulk of Company I, however, remained at the beachhead, where the men of the unit were assigned to labor details such as unloading shipping or to local security guard duties. The heavy weapons of Company M also remained near Arare, for these weapons were part of the Provisional Groupment scheduled to support the next day’s assault on Wakde.

Within a few hours after the mainland beachhead had been secured, the TORNADO Task Force was ready to execute the second phase of the D Day plan—the capture of Insoemanai Island, a little over 3,500 yards offshore. About 1045, under cover of fire from two destroyers and two rocket-equipped LCIs, a platoon of Company E, 163rd Infantry, was transported from the mainland to Insoemanai. There was no opposition to this maneuver and the islet proved to be unoccupied. Four LCMs, an LCVP, and two LCSs immediately took the rest of the company and the Provisional Groupment of heavy weapons to Insoemanai. The landing of the force was rendered difficult only by the fact that a coral fringing reef made it necessary for the troops to wade ashore from about seventy-five yards out. The mortars and machine guns of the Provisional Groupment were quickly set up and began firing on Wakde.

Insoemanai had been easily taken and mainland opposition had been very light. Moreover, no signs of enemy activity had been observed on Wakde and information obtained prior to 17 May had indicated that the Japanese might have withdrawn their garrison from that island. Enthusiastically,

some subordinate officers within the task force suggested that Wakde could be seized immediately and with little difficulty. But General Doe and Captain Noble vetoed such suggestions. They considered it probable that the enemy still retained a strong garrison on Wakde and believed that attacking the island prior to concentrated artillery and naval bombardment would be a needless risk. General Doe decided that there would be no landing on Wakde until after intensive preparatory fire from the Provisional Groupment on Insoemanai, and from naval support ships, aircraft, and shore-based field artillery.

The 218th and 167th Field Artillery Battalions and the Cannon Company, 163rd Infantry, had come ashore near Arare in midmorning. By noon the units had set up firing positions about 2,000 yards east of Arare and had begun dropping shells on Wakde Island. This fire apparently goaded the Japanese on Wakde Island into answering, and during the afternoon the enemy began putting mortar and machine gun fire into the positions of the Provisional Groupment on Insoemanai.

The fire from Wakde was the only Japanese ground opposition worthy of the name encountered by the TORNADO Task Force on D Day. There was no naval or air reaction on the part of the enemy. The task force antiaircraft artillery, which had moved ashore before 0900 hours and had set up positions along the beach between Arare and Toem, found no targets.

Task force engineers started work on the beach track as soon as they came ashore. By 1400 the 27th Engineers had bulldozed a two-way road, capable of bearing heavy trucks, along the shore between Arare and Toem. The battalion, with Company A of the 116th Engineers attached, rapidly enlarged the scope of its activities and began clearing bivouac and dump areas and aiding the Shore Battalion, 593rd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, to unload ships. The latter unit devoted its attention principally to moving cargo ashore, but also had men working on dump areas and construction of sand jetties from the beach to LSTs. The 1st Platoon, 603rd Tank Company, came ashore at midmorning, went into bivouac near Arare, and prepared to move on call to either flank of the beachhead. The platoon’s services were not required.

The few casualties incurred on D Day from enemy action totaled one man killed and four wounded, all as a result of Japanese fire on Insoemanai from Wakde. American artillery shorts41 killed another and wounded six on Insoemanai. One man accidentally wounded himself during the landing at Arare. Total American casualties for the day were 2 killed and 11 wounded, as opposed to 21 Japanese killed or found dead on the mainland. These Japanese appeared to be stragglers rather than members of an organized defense force.

By 1800 all troops of the TORNADO Task Force were dug in for the night. At task force headquarters final details of plans for the seizure of Wakde Island on the morrow were discussed and agreed upon. Shore-based artillery, the Provisional Groupment on Insoemanai, and some of the naval fire support ships were to deliver harassing fire on Wakde throughout the night. At 0715 on 18 May, Fifth Air Force planes were to start an hour-long aerial bombardment of Wakde. At 0830 a heavy naval and artillery

barrage was to begin. Until 0857 this gunfire was to be aimed at the proposed landing beach on the southern shore of Wakde, and was then to be lifted to the northern side of the island. The Provisional Groupment on Insoemanai was to provide close support for the landings.

H Hour for the assault was set for 0900 hours, 18 May. Infantry forces consisted of four rifle companies—A, B, and C of the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry, and F of the 2nd Battalion. Four Sherman tanks (M4 mediums, armed with 75-mm. guns) of the 1st Platoon, 603rd Tank Company, were also assigned to the assault force. The force commander was Major Wing of the 1st Battalion. The troops were to be transported to Wakde in six waves of four LCVPs each, the boats to be coxswained by Company B, 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. LCMs were assigned to take the tanks from the mainland to Wakde.42

Small-Island Warfare, Southwest Pacific Style

The Target—Terrain and Defenses

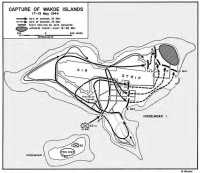

Wakde Island, roughly 3,000 yards long and 1,200 yards wide, had been a coconut plantation before the war (Map 10). The airstrip and associated installations constructed by the Japanese covered almost one half of the island’s surface, the remainder of which was left to neglected coconut trees. The island is generally flat, except for a knoll about twenty-five feet high on a small peninsula jutting out from the southeastern shore. The rest of the island is not more than fifteen feet above sea level, but even this slight elevation is enough to produce a number of small coral caves along the eastern shore. A coral reef completely surrounds the island. One of the three places at which this reef was found to be broken was in a sheltered bay west of the small peninsula, near the base of which a small jetty projected into the bay. The beach at the jetty was chosen as the landing site for the 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry.43

The nucleus of the Japanese garrison on Wakde Island was the 9th Company, 3rd Battalion, 224th Infantry. This company was reinforced by a platoon of mountain artillery (75-mm. guns) and a few mortar and both light and heavy machine gun squads from other 224th Infantry units. The strength of this combat force was about 280 men. There was also a naval guard unit of about 150 men, and a battery of the 53rd Field Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, most of whose weapons had long since been demolished. Miscellaneous airdrome engineers and other service personnel, both Army and Navy, brought the total of Japanese strength on the island to nearly 800 troops.

While most of the arms possessed by the Wakde defenders were light mortars or rifles and machine guns not over .30 caliber in size, there were a few heavier weapons. Such weapons included a few 20-mm. antiaircraft guns, and machine cannon and .50 caliber machine guns taken from damaged Japanese aircraft. Apparently, none of the Japanese 75-mm. mountain guns survived the preliminary bombardment of Wakde Island.

The Japanese had constructed many defensive positions on Wakde. There were

Map 10: Capture of Wakde Islands, 17–19 May 1944

about a hundred bunkers of various sizes and constructions. Some were made of coconut logs and dirt, others utilized cement in sacks, and a few contained concrete or lumps of coarse coral. There were many foxholes and slit trenches, and the Japanese had improved some of the bomb craters to make defensive positions. There were at least two well-constructed concrete air raid shelters and the Japanese were prepared to use the few coral caves on the eastern shore for both defense and storage.

Many of the defensive positions were well camouflaged, and some were dug deep into the ground to present a low silhouette. Coconut trees toppled by preassault bombardments added more natural camouflage and protection to the enemy’s defensive positions. The majority of the many bunkers were mutually supporting, but, on the other hand, some had been built with no apparent relationship to others. Some of the bunkers, most of the field and antiaircraft gun positions, the airstrip, and many buildings had been severely damaged or destroyed by U.S. Fifth Fleet carrier-based aircraft during

their attacks on the Wakde–Sarmi area in support of the Hollandia operation. Army aircraft had taken up the bombardment after that, and, according to Japanese reports, the Wakde strip had been damaged beyond all hope of repair (that is, with equipment available to the Japanese) by 2 May. Allied naval and air bombardment of Wakde, beginning on 17 May, added to the earlier destruction. However, the Japanese Wakde garrison was still capable of a tenacious defense.44

The First Day

Naval fire started on schedule on 18 May.45 By the time it ended, 400 rounds of 6-inch and 1,950 rounds of 5-inch ammunition had been expended against Wakde’s defenses. In addition, rocket-equipped LCIs threw 850 4.5-inch rockets on the island, and 36 A-20’s of the Fifth Air Force bombed and strafed the Japanese defenses. The 191st Field Artillery Group fired for twenty-three minutes on Wakde, and this bombardment was supplemented by 20-mm. and 40-mm. weapons aboard naval support vessels upon completion of the latters’ fire from heavier weapons. The Provisional Groupment on Insoemanai joined in.

The first wave of LCVPs, Company B aboard, began to receive Japanese rifle and machine gun fire from about 300 yards out, but pushed on toward Wakde to hit the beach a few yards to the left of the jetty at 0910. The other three rifle companies and two tanks were ashore in the same area by 0925.46 A third tank had shorted its electrical system while loading from the mainland and a fourth dropped into seven feet of water as it left its LCMs ramp. Neither got to Wakde on 18 May. All landing waves were subjected to increasing fire from Japanese machine guns and rifles in hidden positions on the flanks of the beachhead. Luckily, the Japanese, for unknown reasons, failed to bring into play .50 caliber and 20-mm. weapons. As it was, three company commanders were lost during the landing, one killed and two wounded.

Despite this opposition, the beachhead was quickly organized. Company executive officers assumed command of the leaderless

The assault on Wakde Island, against Japanese machine gun and rifle fire

units, and the two tanks, with Companies B and F, started moving west to widen the initial hold. Company C struck north toward the airstrip and Company A pushed to the southeast along the small peninsula to destroy a troublesome machine gun nest on the little knoll. Company A reached the top of the knoll about 0935. The unit’s progress was temporarily halted ten minutes later at an enemy bunker, the occupants of which were finally killed with hand grenades, but by 1045 the company, employing fire and movement, had finished clearing the peninsula and had assembled for further missions. Companies B and F, after meeting initial heavy resistance on the west flank, found that most opposition collapsed once the ruins of prewar plantation houses had been cleared by hand grenades and rifle fire. The two companies thereupon left the beach and swung north toward the airfield. Company C, meanwhile, had encountered strong resistance in its drive up the center of the island.

About 200 yards inland Company C had come upon a number of mutually supporting pillboxes. The first group of bunkers was found about 0915, and the company spent nearly an hour clearing them out with hand grenades and infantry assault. About 100 yards farther north, at 1015, a second set of pillboxes held up the advance. All these defensive positions were found to be well concealed by Japanese efforts, by underbrush of the neglected coconut plantation, or by coconut trees toppled in the preassault bombardments. Finding progress against such bunkers laborious, Company C called for tank support. The two available tanks, which had been operating on the left flank with Companies B and F, had returned to the beachhead to replenish ammunition at 1030, and were now ordered to aid C Company. Just before 1130 hours the tanks joined the infantry unit, which had now pushed halfway from the beach to the airstrip. With this added strength Company C reduced each bunker in a series of separate actions which included 75-mm. fire from the tanks, lobbing hand grenades into the bunkers’ fire ports, and killing with rifle fire all Japanese who showed themselves.

While Company C’s drive continued, Company B, about 1030, had reached the southern edge of the airfield near the center of that strip. A few minutes later Company F, less one platoon left to mop up around the plantation houses, pulled up on B’s left. The two companies had encountered only scattered opposition after leaving the plantation house area, and Company F had found the western portion of the strip clear of enemy forces. Company B pushed east along the south side of the drome, crossed Company C’s front, and helped the latter unit destroy some of the bunkers which had been slowing its advance. With Company B’s aid and the continued support of the two tanks, Company C was able to push on to the airstrip, where it arrived shortly after 1130.

The Company F platoon which was clearing out the nearly demolished remnants of the prewar coconut plantation buildings about 300 yards northwest of the initial beachhead was halted and pinned down by enemy machine gun fire. Company A was therefore withdrawn from the small peninsula and sent to the platoon’s aid, and the two tanks rumbled back from Company C’s front to assist. Shortly after noon, following about half an hour of close-in fighting with rifles, grenades, tank machine guns, and even bayonets, the plantation houses were cleared. The Company F platoon then rejoined its parent unit at the airstrip, while

Company A and the two tanks moved northwest to clear the western end of the island.

Company A pushed along the beach road and down a dispersal lane running off the southwest side of the strip. About 1245 the advance was held up by three Japanese bunkers on the right flank. Tank 75-mm. fire, delivered from as close as 20 yards, soon eliminated the Japanese defenders. Small groups of Japanese, originally hiding in foxholes behind the three pillboxes, attempted to assault the tanks with hand grenades and bayonets. Company A’s automatic riflemen quickly dispersed or killed these men, and the unit pushed on around the west end of the airstrip. Little opposition was encountered in this movement and the company reached the north shore of Wakde Island about 1330 hours.

In the northeast corner of the island the Japanese forces maintained a tenacious defense, and Companies’ B, C, and F were subjected to considerable small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire originating from positions at the eastern end of the airstrip. Movement eastward along the south side of the strip was slow, even though Companies B and F had been reinforced by Company D’s heavy machine guns, which had arrived on Wakde from Insoemanai late in the morning. To overcome the enemy opposition and secure the rest of Wakde, Major Wing planned a complicated maneuver. Company A, from the northwest corner of the island, was to move east along the northern side of the field to clear the Japanese from the area between the strip and the north shore. Company C was to cross the strip and then swing east toward the northeast corner of Wakde in co-operation with Company A’s drive, Company B was to continue pushing east along the southern edge of the airfield, clear the eastern third of the drome, and then push around the end of the strip into the northeast corner of the island. Company F was initially to follow Company B. When the latter unit reached the eastern end of the strip, Company F was to move to the island’s eastern beaches and thence north along the shore line to the northeast tip.

This attack was slow in getting under way. Several officers and key noncommissioned officers, including three company commanders, had been killed or seriously wounded during the morning’s action, and all four rifle companies faced problems of reorganization. Major Wing therefore decided to await the arrival of two more tanks from the mainland and the redisposition of Company D’s weapons before attacking what promised to be the strongest Japanese defenses on Wakde. The two additional tanks were to be used wherever opposition proved heaviest, while the heavy weapons of Company D were to be equally divided between Companies B and F. Finally, an additional delay was incurred when Company C. which had managed to move less than half its men across the airstrip, came under intense machine gun fire from the east. This fire made it impossible for more troops to cross the open airfield.

Artillery fire from the 218th and 167th Field Artillery Battalions on the mainland temporarily silenced the enemy machine guns, and more men of Company C crossed the airfield about 1545. At approximately the same time the other three companies started the drive eastward. Company A rapidly moved forward from the western end of the strip, passed through Company C at the halfway point, and pushed cautiously eastward. Movement after passing Company C was slowed by increasingly heavy machine gun and mortar fire from

the northeast section of the island. At 1800, when Major Wing ordered his men to dig in for the night, Company A had not quite reached the northeastern corner of the airfield.

Meanwhile, south of the strip Company B had scarcely started its attack when fire from hidden Japanese machine guns held up the advance. Company F was immediately pulled out of its reserve role and committed to action on B’s right flank. Two tanks were moved forward to Company B’s front at the same time. Despite their best efforts and even with the tank support, Companies B and F were unable to progress more than 300 yards east of the lines of departure. Major Wing decided that since dusk was approaching it would be useless to continue the attack. The two companies were therefore halted and instructed to take up night defensive positions.

Company A had set up its night perimeter about 100 yards short of the northeast corner of the airdrome. Company B was on the south side of the strip about 450 yards from the eastern end, and Company F was on B’s right. Company C was pulled back to the southern side of the field and extended Company F’s line to the southeast beach at the base of the small peninsula. The battalion command post was about 400 yards behind the lines of Company F. There was no connection across the strip between Companies A and B. The former was in a dangerously exposed position. However, Japanese fire against the company perimeter ceased before dark, and the Japanese did not attack.

Army casualties on Wakde during the day totaled 19 killed or died of wounds and 86 wounded, while Navy casualties were 2 killed and 8 wounded. Among the Army losses were 7 officers and 14 noncommissioned officers of the rank of staff sergeant and higher. Heaviest casualties were in Company B which lost 42 men, most of them during the later afternoon attack. No accurate count of Japanese dead could be made, but it was estimated that at least 200 had been killed and many more wounded. There were no prisoners.

Back at the beachhead, four LSTs (including one used as a front-line hospital) and numerous smaller craft had unloaded engineer construction units and equipment during the afternoon in the hope that repair work could begin on the airdrome. The stubborn Japanese defense had forestalled the attainment of this objective, and Major Wing laid careful plans to secure the rest of the island on the morrow so that the vital repair work could be started. Company C, preceded by all available tanks (there were now three in action) was to push along the east shore into the northeast pocket of Japanese resistance. Companies B and F were to continue their drives from the point at which they were halted on the 18th, cooperating with Company C in rolling up the Japanese left. Initially, Company A was to remain on the defensive to prevent any Japanese from escaping to the western portion of the island around the north side of the airfield.

A New Air Base on the Road to the Philippines

Luckily for Company A, the night of 18–19 May passed mostly without incident in the company sector.47 The battalion command

Enemy defensive positions on Wakde. Shelters made of coconut logs and dirt (top). Concrete air raid shelter (bottom)

post, which was protected by elements of Company D, was not so fortunate. About 0230 on the 19th a small group of enemy attacked the command post, and a half-hour fire fight raged in the darkness. Twelve Japanese were killed while three Americans, all of D Company, were wounded. This night battle did not delay the next day’s attack which started, after an artillery and mortar preparation of one hour’s duration, at 0915.

Company C was the first unit under way on the 19th. Two tanks were assigned to the 3rd Platoon and one to the 2nd. The 3rd Platoon was on the left, the 2nd on the right, and the 1st and Weapons Platoons were in support. The 3rd Platoon pushed eastward up a slight rise, harassed by light rifle fire from the front and left flank. Once on top of the rise the platoon met heavy Japanese fire from behind fallen coconut trees and from a number of bunkers, bomb craters, and demolished buildings to the east. The 75-mm. guns of the tanks methodically destroyed each enemy position, and the few enemy that escaped from the bunkers were cut down by 3rd Platoon riflemen. The 2nd Platoon, followed by the rest of C Company, moved on toward the eastern beaches, and was slowed only by heavy brush near the shore. Upon turning north at the beach the company found that the Japanese had converted a number of small coral caves into minor strong points. These were slowly cleared by riflemen, tank fire, and flame throwers as the company pushed on.

Meanwhile, Company B, moving east along the south edge of the airstrip, had also encountered many Japanese defensive positions. Progress was at a snail’s pace. Company F, in reserve during the early part of the drive, was thrown into the fight on B’s right flank about 1130 and two tanks were sent from Company C’s front to support Company B. The latter, with its zone of responsibility now nearly halved, was able to concentrate its forces for more effective operations. A rifle platoon was assigned to each tank and the remaining rifle platoon was in support. Some Japanese were found hidden in wrecks of aircraft, some of which covered bunkers, and others were in foxholes in heavy brush. This brush was difficult for soldiers afoot to penetrate but the tanks, spraying every likely hiding place with machine gun fire, rapidly broke paths through it. The advance, even with the tank support, was slow, because it was necessary to comb every square foot of ground for Japanese riflemen. It was not until 1400 that Company B reached the southeast corner of the strip.

On B’s right, Company F and one tank encountered similar opposition but managed to keep abreast of Companies B and C. Late in the afternoon both F and C turned north and about 1600 hours reached a line extending almost due east from the southeast corner of the strip to the east shore. Meanwhile, since the Japanese were maintaining a static defense and making no attempt to counterattack or escape to the west, Company A’s holding mission had been canceled. The unit moved away from the northeast corner of the airfield, sending part of its strength to the north shore and the rest around the eastern side of the strip to make contact with Company B. This contact was established near the northeast corner at 1640. The principal objective of the TORNADO Task Force was thereby secured.

With the clearance of the eastern end of the field, organized Japanese resistance collapsed. Companies B, C, and F pushed rapidly northward and by 1800, when the day’s action ceased, the Japanese were compressed into a small triangle, about 500

yards long on the inland leg, at the northeast corner of the island. It was estimated that 350 Japanese had been killed during the day. Major Wing made plans to mop up the remaining few on the 20th, and pulled most of his units back to the center of the island for the night for a hot meal and rest.

Action on the 20th opened with a banzai charge by 37 Japanese (who had apparently slipped through Company C’s lines during the night) against engineer units at the beachhead. Within minutes after this attack started at 0730, there were 36 dead and 1 wounded Japanese—the latter was taken prisoner. At 0900 Companies A, C, and F started patrolling in the northeast pocket. A few Japanese were killed, others were buried by demolition charges in coral caves along the northeast shore, and many committed suicide. During the afternoon Major Wing’s men moved back to the mainland and turned over control of Wakde Island to the Allied Air Forces. Two days later Company L, 163rd Infantry, was sent to Wakde to mop up a few Japanese snipers who were hindering work on the airdromes. The company returned to the mainland on 26 May, after killing 8 Japanese.

At 1500 on 19 May, even before the island was declared secure, the 836th Engineer Aviation Battalion had begun repairs on the western end of the Wakde airdrome while it was still subject to occasional enemy fire. The work was resumed the next day and, despite one or two minor interruptions from Japanese rifle fire, the strip was operational by noon on 21 May. The first planes landed on the island that afternoon, two days ahead of schedule. Within a few more days the Wakde strip was sufficiently repaired and enlarged to furnish the needed base from which bombers could support the Biak operation on 27 May and the Central Pacific’s advance to the Marianas in mid-June. Wakde–based fighters were to provide close support for continuing operations on the mainland opposite that island.

The final count of Japanese casualties on Wakde Island was 759 killed and 4 captured. An additional 50 or more of the enemy had been killed on the mainland through 20 May. In action on Wakde the U.S. Army lost 40 men killed or died of wounds and 107 wounded. Total American casualties, including naval, on Wakde, Insoemanai, Liki, Niroemoar, and the neighboring mainland through 20 May were 43 killed and 139 wounded. During the same period the Japanese lost at least 800 men. The TORNADO Task Force had secured an extremely valuable stepping stone on the road back to the Philippines at a low cost in men and matériel.48