Chapter 14: Frustration at Mokmer Drome

Reinforcements for the 186th Infantry

Japanese Reactions to the Westward Advance

During its advance west from the surveyed drome, the 186th Infantry had met little opposition after 2 June.1 While it is inconceivable that the Biak Detachment had not anticipated the possibility of an American flanking maneuver through the inland plateau, there are many possible explanations for the failure of the Japanese to oppose this movement strongly after the initial battle at the surveyed drome. Colonel Kuzume and General Numata had reason to believe that the Americans might make an amphibious attack at Mokmer Drome. Small craft of engineer and artillery units attached to the HURRICANE Task Force continuously patrolled along the coast west of Bosnek to Sorido, and Seventh Fleet fire support vessels kept up harassing fires on all known and suspected enemy installations in the airfield area. Therefore, the Biak Detachment kept the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, and most of the armed service personnel immobilized on the low ridge and terraces north of Mokmer Drome and at the West Caves. Colonel Kuzume’s principal responsibility was the defense of the airfields. While the best defense is usually a good offense and while it is often more sensible to defend an area from a distance, the Biak Detachment had strength neither to launch a large-scale offensive nor to defend every approach to the airfields. The attacks against the 162nd Infantry on 28 and 29 May had resulted in the loss of most of the Biak Detachment’s armor and had cost the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, many casualties, including its commander. Colonel Kuzume could ill afford any more such Pyrrhic victories.

The 1st Battalion, 222nd Infantry, had made no serious attempt to stop the 186th Infantry’s progress westward because the inland plateau was nearly indefensible and because the battalion would have been decimated in battle with the superior strength of the reinforced American regiment. The 1st Battalion was withdrawn from the surveyed drome area on 2 June, initially in preparation for counterattack against the Bosnek beachhead. While no such counteroffensive was mounted, the withdrawal of the 1st Battalion at least had the advantage of keeping the unit intact.

Upon the arrival of the 186th Infantry at Mokmer Drome, the 1st Battalion, 222nd Infantry, began moving back to the West

Caves area, after a long march through the jungle and rising ground north of the inland plateau. Colonel Kuzume and Headquarters, Biak Detachment, reached the West Caves during the night of 9–10 June, and the 1st Battalion began closing in the same area the next day. On the evening of 9 June, General Numata transferred the control of further operations on Biak to Colonel Kuzume. The general left next day for Korim Bay, whence he was evacuated by seaplane and returned to the 2nd Area Army’s command post at Manado, in the Celebes.

Colonel Kuzume knew that as long as he could hold the low ridge and terrace north of Mokmer Drome, he could prevent the HURRICANE Task Force from repairing and using that field or Borokoe and Sorido Dromes. To conduct his defense he had under his control north of Mokmer Drome by the evening of 10 June the remaining elements of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 222nd Infantry, totalling about 1,200 men; most of his armed service troops; the bulk of the 19th Naval Guard Unit; and most of the field and antiaircraft artillery pieces, mortars, and automatic weapons still serviceable. Some naval troops and a 222nd Infantry mortar unit manned the East Caves positions, while the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, remained isolated at the Ibdi Pocket. Even without the Ibdi Pocket and East Caves groups, the Biak Detachment was well disposed to conduct a stubborn defense of the airfields, as the HURRICANE Task Force was soon to learn.

The Decision to Reinforce the 186th Infantry

On the morning of 8 June the 186th Infantry consolidated its positions around Mokmer Drome and cleared a number of small caves on a coral shelf located along the water line.2 At 0830 the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, started to move east to rejoin its parent regiment. The battalion had marched scarcely 800 yards east of Mokmer Drome when it was pinned down by Japanese automatic weapons and mortar fire from the East Caves. Finally, the 81-mm. mortars of Company D, 186th Infantry, from emplacements near Sboeria, stopped enough of the Japanese fire to permit the 2nd Battalion to push on. Company G, 186th Infantry, was sent northeast from Mokmer Drome to find the source of the Japanese fire and to protect the left of the 162nd Infantry’s Battalion. The latter dug in for the night only a few yards east of the point where it had first halted, while the 186th Infantry’s company set up defenses on the main ridge north of the East Caves.

Japanese mortar fire fell into the area held by the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, intermittently throughout the night. Many minor casualties occurred until, toward morning, the battalion’s 81-mm. mortars succeeded in silencing most of the enemy weapons. Japanese from the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, harassed the battalion rear all night, and small parties made abortive attacks from the north. All these Japanese groups were beaten back with mortar, machine gun, and rifle fire, and during the scattered firing the new commander of the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, was killed.3

On the west flank the 3rd Battalion, 186th Infantry, also had some trouble during the night. Shortly after dark, Japanese mortar fire began falling on the elements of the battalion dug in north of the coastal road, and later this fire shifted to the battalion positions south of the road. By either accident or design, a number of native dogs, running around and barking outside the battalion perimeter, helped the Japanese locate the unit’s lines and, about 2100, as the enemy mortar fire moved eastward, troops of the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, attacked from the west and northwest. A few Japanese managed to infiltrate the battalion’s outposts and several American soldiers were bayoneted before the battalion’s 60-mm. mortars, together with machine gun and rifle fire, broke up the Japanese attack. The Japanese continued to harass the perimeter until 0530. Japanese losses were 42 counted dead, while the 3rd Battalion, 186th Infantry, lost 8 killed and 20 wounded. Total casualties for the 186th Infantry and attached units during the night were 13 men killed and 38 wounded.

On the morning of 9 June Company B, 186th Infantry, was sent from the beachhead to a point on the low ridge directly north of the center of Mokmer Drome to clear that ridge westward 1,200 yards and secure the point at which a motor road ran northwestward over the ridge. It soon became evident that the company was trying to bite off more than it could chew. Hardly had the leading platoon arrived atop the low ridge than it was pinned down by Japanese machine gun fire and then almost surrounded by Japanese infantry. When Japanese patrols threatened the rear of the company, all elements were withdrawn 400 yards south to set up a new base, from which patrols moved along the foot of the ridge in an attempt to determine the extent of the enemy’s defenses. Results were inconclusive, and at dusk the unit moved back to the beachhead. It could report only that the low ridge was strongly held. Meanwhile, another company patrolled northeast to the point at which the regiment had crossed the main ridge, and established contact there with units of the 163rd Infantry, which had pushed over the inland plateau behind the 186th. Tank-infantry patrols were sent west along the beach from Sboeria. A few bunkers and some small ammunition dumps were destroyed, but few Japanese troops were seen and there was no opposition. On the east flank, Japanese fire from the East Caves again kept the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, immobilized. Patrolling by elements of the 162nd, 163rd, and 186th Infantry Regiments in the East Caves area was productive of little information concerning the location of the principal Japanese positions.

On 10 June the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, sent two companies to the point on the low ridge where Company B had been halted the previous afternoon. Despite artillery support, the two units could make little progress and were themselves pinned down about 1030. Japanese rifle and mortar fire was silenced by the 1st Battalion’s 60-mm. mortars, but the Japanese continued to pour machine gun fire from a number of bunkers and pillboxes which proved impervious to bazooka and 75-mm. tank fire. The units withdrew while more artillery fire was placed along the low ridge. On the east flank, enemy fire from the East Caves had died down, and the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry,

was able to move on eastward. But before that battalion had gone very far, and before the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, could mount another attack against the low ridge, Headquarters, HURRICANE Task Force, had evolved a new plan of operations.

During the period 7–10 June little progress had been made in securing the Mokmer Drome area, and aviation engineers, brought forward by water from Bosnek on the 9th and 10th, had so far been unable to work on the strip because it was still exposed to Japanese fire from the low ridge and terrace north of the field. General Fuller had therefore decided to throw two infantry regiments against the enemy defenses north of the field. For this purpose the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was returned to regimental control, and the remainder of the 162nd Infantry started westward from the Parai area toward Mokmer Drome.

The 162nd Infantry Moves to Mokmer Drome

While the 186th Infantry had been driving to the airfield over the inland plateau, the 162nd Infantry, less the 2nd Battalion, and with Company A, 186th Infantry, attached, had been attempting to move westward in a coordinated drive along the coastal road.4 This attempt had not proved successful, for Japanese opposition at the Ibdi Pocket and the Parai Defile kept the 162nd Infantry tied up.5

On 7 June, when the 186th Infantry reached Mokmer Drome, it became a matter of urgency to open an overland line of communications to the airfield area. The 186th Infantry could be supplied overwater with some difficulty, but overland movement was faster and more efficient. Therefore General Fuller initially decided to outflank the enemy’s positions in the Parai Defile by a drive from west to east along the cliffs above the road through the defile. For this purpose two companies of the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, were to be transported overwater from Ibdi to the Parai Jetty, whence they were to drive east in conjunction with a westward push by the rest of the battalion.

On 7 June the proposed landing area at Parai Jetty (but not the jetty itself) was subjected to artillery and naval preparation fires. Three LVT(A)’s and eighteen LVTs picked up Companies I and K (reinforced) at the 3rd Battalion position. They moved far out in the stream to avoid enemy mortar or artillery fire and, at 1315, started moving inshore toward the jetty. The first wave was delayed when two LVTs stuck on the reef fronting Parai, and the first amphibian tractors did not reach the beach until 1420. Fifteen minutes later, both the reinforced companies were ashore. As soon as the two companies landed they came under fire from Japanese weapons in the East Caves and along the ridge between that position and the Parai Defile. They then called for reinforcements. The Cannon Company arrived at the jetty about 1610 and six tanks of the 603rd Tank Company reached the area about 1730. Patrols were then sent into the Parai Defile, meeting opposition which steadily increased as they moved eastward.

A concerted drive could not be organized before dark, and plans had to be made to continue the attack on the morrow.

Meanwhile, General Fuller had evolved his plan to move all the 162nd Infantry to the Mokmer Drome area. By this time it had become evident that the 1st Battalion had isolated the principal remaining enemy strong points in the Ibdi Pocket and the task force commander had decided to leave only one company as a holding force in that area to prevent the Japanese from cutting the coastal road. The remainder of the 1st and 3rd Battalions were to move to Parai and push west toward Mokmer Drome to establish contact with the 186th Infantry and the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry.

At 0900 on 8 June, Companies C, I, and K, supported by tanks, began moving west from Parai into the ground where the Japanese had counterattacked the 162nd Infantry on 28 and 29 May. Company C advanced along the coastal road, while Companies I and K pushed up the low cliff at the coast from Parai to Mokmer village and attacked along the terrace above Company C. By noon, when they stopped to lunch and rest, the three companies were within 500 yards of Mokmer village and in the coconut grove through which the Japanese had launched the 29 May tank attack. At 1330, just after the advance companies had resumed their attack, they were pinned down by heavy mortar fire from the East Caves. Another infantry company was requested, and Company B moved forward to the right of the units on the terrace. There were indications that the enemy was preparing a counterattack similar to the one he had launched in the same area ten days earlier, but such an offensive did not develop.

Meanwhile, it had been discovered that the Japanese had mined the main road west from Parai. Tank progress was slowed as the mines (most of them actually 6-inch naval shells) were removed or the vehicles guided around them. As the tanks approached Mokmer village, they came under mortar and automatic weapons fire from the East Caves. Since these weapons were masked by trees, the tanks were unable to deliver counterbattery fire against the enemy positions and were finally forced to seek cover. Continuing mortar and small arms fire made the forward units of the 162nd Infantry seek shelter also and they dug in for the night along a curving perimeter which began on the beach 500 yards east of Mokmer and stretched northeastward some 800 yards almost to the base of the main ridge. A gap of about 1,800 yards remained between these forward companies and the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, west of Mokmer.

On the morning of 9 June the 1st and 3rd Battalions again began pushing westward. Despite heavy concentrations by the regiment’s 81-mm. mortars, the 4.2-inch mortars of Company D, 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the 105-mm. howitzers of the 205th Field Artillery Battalion, Japanese fire from the East Caves steadily increased. The infantry could move forward only in small groups and were forced to seek cover behind every slight rise in the ground. At 1330 Company C established patrol contact with the 2nd Battalion at a point 500 yards west of Mokmer village, and at 1700 the 2nd Battalion reverted to regimental control after a week’s operations under the 186th Infantry. More than 1,000 yards still separated the main body of the 2nd Battalion from the 1st, which dug in for the night at Mokmer village. The 3rd Battalion, in reserve

Men of the 162nd Infantry seeking cover as they move westward along the shore

during the day, had not moved far beyond its bivouac of the previous night.

On 10 June Company L and rear detachments of the 3rd Battalion were moved forward by small craft to Parai. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions then began moving west along the coastal road to Mokmer Drome while the 1st Battalion was left at Parai with the mission of defending that area and clearing the remaining enemy from the Parai Defile. West from Mokmer village the coastal road was still subjected to heavy interdictory fire from the Japanese in the East Caves. Therefore, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions had to move along the beach under the protection of a low coral shelf. The march was accomplished in column of files and most of the troops waded through the edge of the surf, which was waist deep much of the way. The movement therefore progressed very slowly, and it was not until 1600 that the two battalions reached an assembly area at the eastern end of Mokmer Drome. The next day there began a new offensive which was aimed at clearing the Japanese from the ridges and terraces north and west of the airfield.

Operations North of Mokmer Drome

The Plan of Attack

The new attack to secure the Mokmer Drome area was to start at 0930 on 11 June

with two regiments abreast, the 162nd Infantry on the right, or north. The line of departure began on the beach at Menobaboe, whence it ran north-northeast through the western end of Mokmer Drome and over the low ridge. The boundary between regiments paralleled the coast and lay about 400 yards north of Mokmer Drome’s main runway. The first objective was a first phase line lying about 1,350 yards beyond the western end of the runway. A second phase line was roughly 1,000 yards farther west and included Borokoe village, on the beach some 2,300 yards west of Menobaboe. The inland end of the second phase line lay about 2,000 yards north of the coast. Occupation of the third phase line would bring the two attacking regiments into line with the eastern end of Borokoe Drome.

The 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was responsible for clearing the low ridge. The 1st Battalions of both regiments were to remain in reserve. Details of artillery support are not clear but it appears that at least initially the 121st Field Artillery Battalion was to give close support to the 186th Infantry while the 205th, from positions near Ibdi, was to support both regiments. The 205th’s fire would be directed from a floating observation post in an LCV furnished by the 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. The 947th Field Artillery Battalion was also assigned general support missions.6

While the attacks in the Mokmer Drome area were under way, the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, would continue patrolling west and south along the main ridge. One company of that battalion and Company G, 186th Infantry, were to maintain pressure on the East Caves from the north and west. The 1st Battalion, 163rd Infantry, was to patrol north, east, and west from the surveyed drome on the inland plateau behind Bosnek, while the 2nd Battalion cleared remaining Japanese from the Ibdi Pocket. Support for the operations of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 163rd Infantry, was the responsibility of the 146th Field Artillery Battalion, emplaced near Bosnek. The 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, was apparently to be supported by those artillery units supporting the attacks in the Mokmer Drome area.7

Meeting Resistance on the Low Ridge

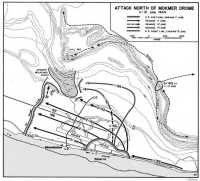

At 0830 on 11 June the two assault battalions of the 186th Infantry began moving out of their bivouacs up to the line of departure, which they reached by 0915.8 (Map 15) The 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, started moving forward from the eastern end of Mokmer Drome toward the line of departure about the same time that the 186th Infantry got underway. The 162nd Infantry met stiff resistance before it could get to the line of departure, and the 186th Infantry’s attack was therefore halted until the 162nd Infantry could move its two leading battalions up to the line. The principal Japanese forces along the low ridge were the 1st Battalion, 222nd Infantry, now reduced

Map 15: Attack North of Mokmer Drome, 11–15 June 1944

to about 120 effectives; a company or two of the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry; elements of various engineer units, fighting as infantry; and some field and antiaircraft artillery weapons and crews. All in all, there were probably some 600–700 Japanese along the ridge.

The 162nd Infantry, employing close mortar support and steady rifle fire from the leading troops, appeared to be breaking through the resistance to its front about 1330, and the 186th Infantry was thereupon ordered to renew its attack. Accordingly, at 1345, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 186th Infantry, pushed across the line of departure. The 3rd Battalion, moving along the coastal road, encountered no enemy opposition and closed along the first phase line in its zone at 1530. The 2nd Battalion met little Japanese resistance on its front but was intermittently forced to seek cover from enemy fire which came from the low

ridge on the battalion’s right. The unit therefore did not reach the first phase line until 1620.

The two 186th Infantry battalions dug in for the night about 600 yards apart, both on the east side of a trail marking the first phase line. The terrain there was solid coral with only a thin layer of topsoil covering it. In such ground three hours was the minimum time a man needed to prepare a satisfactory slit trench, and darkness arrived before all the units could dig in. Colonel Newman therefore recommended that on subsequent days forward movement cease at 1500 so that time would be available to prepare night defenses and to undertake essential evening reconnaissance. This recommendation was approved by Headquarters, HURRICANE Task Force.

For the night of 11–12 June, the headquarters of the 186th Infantry, the 1st Battalion, and an advanced command post of the HURRICANE Task Force dug in at Sboeria village, on the beach south of Mokmer Drome. Company G, 186th Infantry, came down off the ridges near the East Caves during the day and set up its bivouac at Sboeria. At the same location were the Cannon and Service Companies, 186th Infantry, and the 863rd Engineer Aviation Battalion, which was responsible for repairing Mokmer Drome.

In the 162nd Infantry’s zone of responsibility, the day’s action had been marked by stubborn Japanese resistance. The 3rd Battalion, trying to gain the top of the low ridge and to move west along that ridge to the line of departure, was halted and forced to seek cover almost the moment it started to move. Even with support from the 947th Field Artillery Battalion, it was midafternoon before the battalion’s attack really got under way. Then the unit found that the terrain along the top and southern slope of the low ridge was rough and covered by dense rain forest and thick scrub growth. Visibility and maneuver room were severely limited, and the Japanese defenders made excellent use of every advantage the terrain offered.

The 2nd Battalion had been halted about 600 yards short of the line of departure to await the outcome of the 3rd’s efforts, but about 1245 was ordered to push on. The 2nd Battalion reached the line of departure about 1320 and moved on to the first phase line, drawing abreast of the 2nd Battalion, 186th Infantry, at 1720. The 3rd Battalion fought doggedly forward during the afternoon, discovering an ever increasing number of Japanese pillboxes, bunkers, and hasty automatic weapons and rifle emplacements of all kinds. Dusk found the unit still some 100 yards short of the line of departure and about 1,300 yards east of the 2nd Battalion. The 1st Battalion, taking no part in the action during the day, moved forward to Mokmer Drome from Parai.

For 12 June, Colonel Haney planned to put his 2nd and 3rd Battalions on the low ridge, while the 1st took over the 3rd’s positions near the line of departure and patrolled west, north, and east. During the afternoon of the 11th, the 162nd Infantry had learned from Javanese slave laborers who had come into the lines that the Japanese headquarters installations were located in large caves approximately 1,000 yards northwest of the 3rd Battalion’s lines. This, apparently, was the first information obtained by the HURRICANE Task Force concerning the enemy’s West Caves stronghold. The significance of the information was not yet realized, but the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was ordered to patrol north on the 12th to attempt to confirm the Javanese reports.

In order to permit the 162nd Infantry to place more troops on the ridge, the 186th Infantry was instructed to assume responsibility for an additional 300 yards on its right flank. On the 12th that regiment was to advance as far as the second phase line, maintaining close contact with the 162nd Infantry. The latter was also expected to reach the second phase line, but no advance beyond that line was to be undertaken until Headquarters, HURRICANE Task Force, so ordered.

On the morning of the 12th, the 186th Infantry had already started moving toward the second phase line when, at 0830, it received orders to halt until the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, could reach the first phase line. Although no Japanese were to be found in the 186th Infantry’s sector, an advance by that regiment without concurrent progress by the 162nd Infantry would leave a large and dangerous gap in the lines. Through such a gap the enemy could move to outflank and cut off the 162nd Infantry. But the 162nd Infantry was able to make little progress during the day. As a result, the 186th Infantry remained on the first phase line and limited its operations to patrolling.

The 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, had started moving both toward the low ridge and westward about 0830, but it also had been halted until the 3rd Battalion could fight its way up to the first phase line. The 3rd Battalion sent Company L north of the ridge to outflank troublesome Japanese positions while the rest of the battalion continued a frontal assault. But Japanese resistance was even stronger than it had been the previous afternoon, and the battalion was again unable to make any progress. At 0940 it pulled back some 300 yards southeast of its previous night’s bivouac to allow Company M’s 81-mm. mortars to lay a concentration on enemy bunkers and foxholes at the point where the line of departure crossed the low ridge.

At 1035 the advance was resumed with Company I on the ridge, Company L on the terrace north of I, and Company K along the ridge slopes south of I. Company K moved forward 200 yards by 1100, having encountered little opposition, and then halted to wait for the other two companies to draw up. Company I, meanwhile, had found that the mortar fire had been effective but that new Japanese positions were located west of the mortar impact area. From 1100 to 1130 the company fought its way through these second defenses, but no sooner had it broken through when a third set of positions was discovered 50 yards farther west along the ridge. It was also learned that a fourth strong point was located beyond the third. Company L, north of the ridge, met few Japanese and by 1230 had passed through some minor opposition to a position north of but opposite Company K. Company L then cautiously probed southwestward and southward to locate the flanks and rear of the positions in front of Company I.

Meanwhile, Company L, 163rd Infantry, had established an observation post on Hill 320, a high point on the main ridge about 1,500 yards northwest of the lines of the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry. At 1530 this observation post reported that Japanese were occupying a number of antiaircraft gun positions along the low ridge west of the 162nd Infantry unit. Fearing immediate enemy artillery fire, the 162nd Infantry withdrew all its troops from the low ridge into defilade positions.

After American artillery had fired a short concentration on the suspected enemy gun emplacements, the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry,

returned to the low ridge. By nightfall Company L was dug in on the ridge about 300 yards west of the line of departure, and Company I was almost 100 yards to the east. In order to prevent the Japanese from reoccupying their defensive position near the line of departure—positions which had been so laboriously cleaned out during the day—two platoons of Company K moved into the vacated enemy defenses. The rest of Company K, together with 3rd Battalion headquarters and Company M, remained south of the ridge about 400 yards east of the line of departure.

During the late afternoon the 2nd Battalion had sent a number of patrols north from its position on the first phase line to the low ridge, and Company F set up night defenses on the ridge at the point where the first phase line crossed. A gap of almost 900 yards, in which were many strong Japanese defenses, separated Company F from Company L. For the next day, plans were made for the 162nd Infantry to close this gap while the 186th Infantry remained in position along the first phase line.

The 162nd Infantry resumed its attack about 0730 on 13 June when Company L started pushing east and west along the low ridge in an attempt to establish contact with both the 2nd Battalion and Company I. Contact was made with the latter unit about 1300, after a small Japanese pocket had been cleaned out. Company K, meanwhile, had been forced to mop up a few enemy stragglers near the line of departure and had sent one platoon westward to help Company I. Late in the morning, the 1st Battalion moved on to the low ridge east of the 3rd in order to protect the regiment’s right and rear and relieve 3rd Battalion troops from that duty. Though this realignment freed 3rd Battalion units for a new drive westward, by the end of the day little progress had been made in closing the 900-yard gap between that battalion and the 2nd. Not only had the 3rd Battalion been unable to move westward, but 2nd Battalion units had also been unable to make any progress eastward.

During the 13th, the 186th Infantry had limited its activities to patrolling while it again awaited the outcome of the 162d’s attack. The regiment had also provided local security for engineers who were working hard to repair Mokmer Drome. The engineers had begun steady work about 1030 hours on 12 June, and by evening of that day they expected to get the strip into shape for fighter aircraft before noon on the 13th. But work on the latter day was thrice interrupted by Japanese artillery or mortar fire, most of which originated along the ridge between the lines of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 162nd Infantry. Despite these interruptions, about 2,300 feet of the eastern end of the airfield had been repaired sufficiently for use by fighter planes by evening of 13 June. More of the strip had been cleared, filled in, and prepared for final grading by the same time. The first plane to land on the field was an artillery liaison aircraft, which came down about 1000 hours on the 13th. Because of Japanese harassing fire, the airstrip still could not safely be used by larger planes.

To the Rim of the West Caves

General Doe, assistant commander of the 41st Division, had inspected the forward combat area during the afternoon of 13 June.9 After his trip he advised the task force

commander that the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was becoming worn out and had already lost much of its effectiveness. To relieve the 3rd Battalion, General Doe recommended sweeping changes in the attack plan which had been in effect since 10 June. He proposed that the 1st Battalions of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments move around the right flank of the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, to the terrace above the low ridge. Reports from friendly natives indicated that the Japanese were guarding a water hole—the last one remaining in the area—near a Japanese encampment about midway between the positions of Company L, 162nd Infantry, on the low ridge, and those of Company L, 163rd Infantry, on Hill 320 to the north. Although the HURRICANE Task Force had not yet located the West Caves, the reported existence of the water hole and other miscellaneous bits of information prompted General Doe to believe that a major enemy strong point existed near the Japanese encampment. He felt that if the new two-battalion attack succeeded in eliminating this strong point, the remaining enemy positions along the low ridge would be untenable and the Japanese might retire. Then the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, would not have to continue its attacks and, indeed, would be pinched out by the new advance and could revert to a reserve role.

The 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was to move north over a trail which would take it through the rear of the 3rd Battalion. When the 1st Battalion had reached a point on the terrace about 500 yards north of the low ridge, it was to turn and attack to the west and southwest. The 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, was to follow a trail leading north from the eastern end of Mokmer Drome and, making a wider envelopment, was to follow an azimuth taking it east of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry. Then it was to draw up on the right of the latter, ready to attack westward.

For the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, operations on 14 June began about 0600 when Company B, at the base of the low ridge about 800 yards east of the 3rd Battalion’s lines, was attacked by about fifteen Japanese infantrymen. Within ten minutes nine Japanese were killed, but patrolling and reorganizing after the attack delayed the battalion’s movement to the line of departure for the new attack. Following the infantry assault, the Japanese began to throw antiaircraft, small arms, and mortar fire into the American unit’s positions, keeping it pinned down on the southern slopes of the low ridge until 1100. The battalion was further delayed when American artillery fire was placed on Japanese troops seen maneuvering on the terrace north of the 3rd Battalion. Meanwhile, the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, had also been delayed. The 162nd Infantry unit had to wait for the 186th’s battalion to come into line before the attack westward could begin.

With Company C leading, the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, had started its advance at 0800, crossing the low ridge at a point about 500 yards east of the 1st Battalion,

162nd Infantry. Then it moved northeast over the terrace along a rough trail leading toward the main ridge-crossing employed by the 186th Infantry on 7 June. First contact with the enemy came at 0930, when Company C killed two Japanese on the trail about 800 yards north of the low ridge. The march continued until 1030 when, as the units began to turn westward, Company C was pinned down by fire from rising ground 100 yards east of the trail. Company A patrols undertook to stop this fire, but it was two hours before the advance could be continued. Only 400 more yards had been gained by 1300 when the advance was again held up by a small group of Japanese dug in across the trail. But this opposition was broken through within half an hour, and by 1430 Company C had moved another 800 yards west and was in line with Company B, 162nd Infantry, 300 yards to the south. Both 1st Battalions now resumed the advance abreast.

The 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, continued to meet opposition on its right and front during the afternoon, and did not establish physical contact with the 186th Infantry’s battalion until 1735. The 162nd Infantry unit then dug in northeast of the West Caves and about 250 yards north of Company L, on the low ridge. The battalion’s perimeter was about 400 yards short of its objective for the day, as was that of the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, now located on a slight rise 50–75 yards to the right rear of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry. Patrols sent out before dark brought back proof that the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was on the periphery of the West Caves, now recognized by the HURRICANE Task Force as a major Japanese strong point. The task force G-2 Section estimated that the West Caves held about 1,000 Japanese, including naval and army headquarters.

Colonel Kuzume, realizing full well the value of the West Caves position as a base for counterattacks, was determined to hold that area. At 1930 on the 14th, he sent available elements of the Biak Detachment against the two forward American battalions in an attempt to drive them southward and eastward away from the caves. A combined infantry-tank attack drove Company B of the 162nd Infantry out of its semi-isolated position at the northwestern end of the 1st Battalion’s perimeter. The company withdrew in an orderly fashion into the battalion lines. The Japanese now turned their attention to the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry. Small Japanese groups, moving along a road which entered the battalion’s perimeter from the west, harassed the unit all night. No attacks were pressed home, but the Japanese maneuvers were interpreted as presaging a more determined counterattack on the morrow.

At 0730 on the 15th the expected counterattack began, just in time to disrupt plans for the 1st Battalions of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments to continue advances north and west. Three Japanese tanks started south down a road running below the western slope of Hill 320. Two tanks, each accompanied by an infantry platoon, swung onto an east-west road north of the West Caves and into the positions of the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry. The tanks opened fire with their 37-mm. guns from a range of 250 yards, but before they could move closer were driven off by .50-caliber machine guns of the 1st Battalion’s Antitank Platoon. The third tank and more infantrymen charged the lines of Company B, 162nd Infantry, then attempting to close

Disabled Japanese Tank

the gap between the two harassed battalions. In the ensuing melee, Company B suffered heavy casualties, for it had no weapons with which it could easily drive off the tank and stop its 37-mm. and machine gun fire. However, when the accompanying infantrymen were scattered by Company B’s fire, the tank maneuvered out of range. At 1400 the same day, two more tanks advanced toward the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry. The tanks again moved along the east-west road north of the caves but did not press home their attack. Apparently, no Japanese infantry accompanied these tanks.

During the day three Japanese tanks were knocked out—two by bazookas of Company C, 186th Infantry, and the other by a combination of .50-caliber and small arms fire. The 121st Field Artillery Battalion, while it had hit no tanks, had proved a real aid during the battle. It prevented Japanese infantrymen from forming for the attack and neutralized a number of enemy machine guns by firing 600 rounds into the area northwest of the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry.

In the time intervals between the various enemy attacks only local advances could be made, but the two forward battalions managed to establish one continuous line. Patrolling south was forestalled during the morning when artillery and automatic weapons fire was placed on enemy positions between the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 162nd Infantry, on the low ridge. When this fire was finished, the day’s plans were changed. The 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was ordered to move south onto the low ridge west of the

3rd Battalion. Once on the ridge, the 1st Battalion was to do an about-face and extend its left to the 2nd Battalion’s lines. The 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, was to protect the rear of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, during the latter’s displacement southward.

The new plan proved impossible of execution. Fighting in the area between the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 162nd Infantry, on the low ridge continued unabated all afternoon. Steady fire from friendly artillery and mortars, combined with Japanese automatic weapons and mortar fire from positions between the West caves and the low ridge, kept the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, pinned down much of the time and slowed its movement southward. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions continued to try to close the gap and managed to overrun or destroy a number of enemy defensive positions. They were unable to entirely clear the area, however, and by nightfall the gap was still some 500 yards wide and was apparently occupied by a strong enemy force which was well dug in.

The 15th of June, on which date forces of the Central Pacific Area landed in the Mariana Islands, had come and gone, and still no planes of the Allied Air Forces, Southwest Pacific Area, had been able to support the Central Pacific’s operations from an airfield on Biak Island. The 863rd Engineer Aviation Battalion, which had managed to repair about 2,300 feet of Mokmer Drome by evening of 13 June, had been forced to stop work on the morning of the 14th, when Japanese fire on the strip became so intense that the engineers could not stay on the field and Allied planes could not use it. The 15th had ended on a note of frustration in the Mokmer Drome area. The Japanese still held part of the low ridge, and from their positions there and on the terrace to the north, could continue to prevent the Allies from using the Biak fields.

Allied Command at Biak

Air and Naval Base Development to Mid-June

Almost from the outset of the Biak operation, delays in seizing and repairing the Biak Island airfields had worried Generals MacArthur and Krueger. After the initial reverse suffered by the 162nd Infantry, the tactical situation on Biak had made it appear to General Krueger that it might be some time before the HURRICANE Task Force would capture Mokmer Drome. Therefore, on 30 May, he instructed General Fuller to investigate the possibility of quickly constructing a fighter strip at the surveyed drome area on the inland plateau north of Bosnek. The task force completed an engineer reconnaissance of the surveyed drome the next day. General Fuller decided that an airfield could not be completed there in less than three weeks. He considered it undesirable to assign any of his few engineer units to such extended work at the surveyed drome, for he still expected that Mokmer Drome could be seized and repaired much sooner.10

The attention of air force planners then turned to the Paidado Islands, off the southeast corner of Biak. Allied Naval Forces had already planned and secured approval from General MacArthur’s headquarters to establish a PT and seaplane base in a reef-fringed lagoon on the eastern side of Mios Woendi Island, which lies about twelve miles east-southeast

of Bosnek. On 28 May ALAMO Force instructed the HURRICANE Task Force to secure not only Mios Woendi but also the entire Paidado group.11

Reconnaissance was made of Mios Woendi, Aoeki, and Owi Islands in the Paidado group by naval and engineer personnel of the HURRICANE Task Force on 1 June. The next day Company A, 163rd Infantry, secured Owi and Mios Woendi, and a more detailed engineer reconnaissance of Aoeki and Owi was made a few days later. Aoeki proved unsuitable for an airfield, but Owi was found to be an excellent site. Beginning on 3 June, engineers, together with antiaircraft and radar units, were taken to Owi. Heavy artillery (155-mm. guns) was also set up on the island to support operations on Biak.

The 860th and 864th Engineer Aviation Battalions started constructing a strip on Owi on 9 June but it was not until the 17th that enough of the field was completed to allow some P-38’s, blocked by a front of bad weather from reaching their base on Wakde Island after a strike on Sorong, to land at Owi. On 21 June two P-38 squadrons of the 8th Fighter Group, Fifth Air Force, started arriving at Owi to remain for future operations. Meanwhile, naval construction battalions (CBs) had cleared the land and beach at Mios Woendi in time for Seventh Fleet PT boats to begin operating from that base on 8 June.12

The Owi Island strip was not ready in time to support Central Pacific operations and, despite expectations to the contrary, neither was any other field at Biak. The Wakde Island airfield had to bear a larger share of such support than had been planned. Moreover, the delay in making ready the fields on Biak threatened the speed of subsequent operations within the Southwest Pacific. The HURRICANE Task Force had failed in its principal mission—rapid seizure and repair of airfields from which the Allied Air Forces could support the Mariana operation and further advances along the New Guinea axis.

Changes in Command

General Krueger had been dissatisfied with operations on Biak ever since the 162nd Infantry had been forced to withdraw from the Mokmer village area on 29 May. At first he was dissatisfied because he believed that the 162nd Infantry’s advance had been imprudently conducted without adequate reconnaissance. Later, he had expected that the reinforcement of the HURRICANE Task Force by the 163rd Regimental Combat Team would have permitted General Fuller to resume the offensive with renewed vigor and rapidly to seize the airfields. Events did not so transpire.13 On 5 June, five days after

the two battalions of the 163rd Infantry had reached Biak, General MacArthur indicated that he, too, was concerned over the continued delay in securing the Biak airfields. The theater commander asked General Krueger if he thought operations on Biak were being pushed with determination, and he requested General Krueger’s views on the situation.14

As a result of these queries, General Krueger was again prompted to inform General Fuller that progress on Biak was disturbingly slow and to instruct the task force commander to make new efforts to seize the airfields quickly.15 At the same time, the ALAMO Force commander told General MacArthur that he had for some time felt that operations on Biak were not going well and that consideration had even been given to putting in a new commander. However, said General Krueger, he had been dissuaded by his observers on Biak, who had told him that replacement of the task force commander would be unwarranted. The terrain and stubborn Japanese defense had slowed the attack, General Krueger went on, and he had therefore decided to await more complete information before taking any further action.16

On 6 June General Krueger received somewhat disturbing reports from new observers whom he had sent to Biak. These officers indicated that there had been some lack of determination in the execution of HURRICANE Task Force plans, especially at the battalion and company level. The troops striving to clear the Ibdi Pocket and the Parai Defile were reported to be “herd-bound.” The observers’ reports also indicated that reconnaissance had been ineffective; and that little definite information had been obtained concerning the Japanese strength and dispositions. Finally, the observers stated, General Fuller was not making full use of his assistant division commander (General Doe) and, moreover, so few members of the task force staff had visited the front lines that General Fuller could not possibly have obtained complete and accurate information concerning the fighting.17

Despite these unfavorable reports General Krueger, probably influenced by the fact that the 186th Infantry had established a foothold on Mokmer Drome on 7 June, again decided to take no action for a few days. But by 10 June he had received new information telling of the strong resistance the Japanese were maintaining along the low ridge north of Mokmer Drome. Three days of fighting had failed to eliminate this resistance, and General Krueger again urged upon General Fuller the importance of rapid rehabilitation of the Biak airfields, impossible as long as the Japanese held their positions on the low ridge.18 Then, on 13 June, General Fuller, on the grounds that the HURRICANE Task Force troops were suffering from fatigue and that he suspected the Japanese had landed sizable reinforcements

on the island, requested ALAMO Force to send a fresh infantry regiment to Biak.19 While at this time General Krueger placed little credence on the reports of enemy reinforcements, he decided to approve the HURRICANE Task Force’s request for additional strength. Accordingly, on 13 June, he alerted the 34th Infantry, 24th Division, then at Hollandia, for shipment to Biak, where it was to arrive on 18 June.20

By this time General Krueger had come to the conclusion that General Fuller was overburdened by his dual function of task force and division commander. He had thus far deferred taking any action, hoping that the airdromes would soon become available. But by 14 June it had become obvious that this hope would not materialize. Moreover, General Krueger was himself under pressure from General MacArthur, who had indicated to the ALAMO Force commander that the delays on Biak were seriously interfering with the execution of strategic plans and who had already publicly announced that victory had been achieved on Biak.21 Finally, on 14 June, General Krueger decided to relieve General Fuller of the command of the HURRICANE Task Force, apparently with the idea that General Fuller would remain on Biak to devote his full time and attention to the operations of the 41st Division. General Krueger took this step, he asserted, because of slowness of operations on Biak and the failure to secure the Biak airdromes at an early date.22 Lt. Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, commanding general of the U.S. I Corps (and of the RECKLESS Task Force, at Hollandia) was ordered to Biak to assume command of the HURRICANE Task Force.23

General Eichelberger arrived at Biak late on the morning of 15 June and at 1230 assumed command of the HURRICANE Task Force.24 It was an angry and unhappy General Fuller who greeted General Eichelberger at Bosnek. The division commander felt that General Krueger had been unjustifiably critical of the operations on Biak, and he believed that his relief as task force commander indicated that his services had proved unsatisfactory to his superiors. General Fuller had already requested in a letter to General Krueger that he be relieved of the division command as well as that of the task force and he asked for reassignment outside the Southwest Pacific Area.

General Eichelberger was in an embarrassing position, for he had been a classmate of General Fuller at West Point, and the two had been life-long friends. Believing that the division commander still had a good chance to receive a corps command, he tried to persuade General Fuller to change his mind. But General Fuller was adamant, and followed his letter with a radio asking for quick action on his relief from the division command. This tied General Eichelberger’s hands and left General Krueger no choice but to approve General Fuller’s request—a

step he was extremely reluctant to take—and forward it to General Headquarters, where it was also approved by General MacArthur. General Fuller left Biak on 18 June, and, after departing from the Southwest Pacific Area, became Deputy Chief of Staff at the headquarters of Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten’s Southeast Asia Command. At General Eichelberger’s suggestion, command of the 41st Division on Biak passed to General Doe.25

Upon leaving Biak, General Fuller addressed the following letter to his former command:–

To the Officers and Men of the Forty-first Infantry Division.

1. I am being relieved of command for my failure to achieve the results demanded by higher authority. This is in no way a reflection upon you or your work in this operation. I, and I alone, am to blame for this failure.

2. I have commanded the Forty-First Division for better or worse for over two years and one-half. During that period I have learned to respect you, to admire you, and to love you, individually and collectively. You are the finest body of men that it has been my privilege to be associated with in thirty nine years of service.

3. I part with you with many pangs of heart. I wish all of you the best of luck and God Bless You, for I love you all.26

Whether General Fuller’s relief as commander of the HURRICANE Task Force was entirely justifiable is a question which cannot be answered categorically. At the time of his relief, the task force had seized Mokmer Drome. Patrols sent westward to Borokoe and Sorido Dromes had found no enemy at those two fields, and General Fuller knew they could be occupied with ease. But he had not sent more troops beyond Mokmer Drome because he believed it more important to secure an overland line of communications to that field and to clear the low ridge so that repair work could continue and at least one strip could be put in service. By 14 June it was only a question of time before the West Caves area and the low ridge would be secured. Indeed, General Eichelberger, who took three and one-half days to acquaint himself with the situation at Biak, drew up new attack plans according to which the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments were to be employed in the same area and in much the same manner as General Fuller had been using them. General Eichelberger realized, as had General Fuller, that Borokoe and Sorido Dromes would be no safer than Mokmer Drome as long as the Japanese held the low ridge and West Caves positions. But, in the last analysis, the mission of the HURRICANE Task Force, quick seizure and rehabilitation of the Biak fields, had not been accomplished by 15 June. No airfield in the Biak area was yet available for use by the Allied Air Forces.27

There can be no doubt that the two forward regiments were becoming fatigued—they had been in continuous combat for eighteen days in an enervating climate—but it is doubtful that this fatigue was the only trouble. There is some evidence that

there was a lack of aggressiveness at the battalion and company levels of the command,28 and there are definite indications that General Fuller may not have put as much pressure on his regimental commanders as he might have. One regimental commander later stated:–

I was never informed that there had been a deadline set for the capture of the Biak Airfields, nor that there was any pressure being applied on Gen. Fuller from higher headquarters. I only learned of this after his relief. As far as I knew the operation was proceeding with fairly satisfactory speed. Had I known of the need for speed in supporting the Marianas attack I might have acted differently on several occasions.29

One of the reasons that the HURRICANE Task Force had had such difficulty in securing the Mokmer Drome area was that fresh Japanese troops had been arriving on Biak since 27 May and had been thrown into the action at the airfields. General Fuller, on the basis of aerial reconnaissance reports and intelligence received from ALAMO Force, had for some time suspected that Japanese reinforcements were reaching Biak. This suspicion, coupled with the growing fatigue of 41st Division troops on the island, had, on 13 June, prompted the HURRICANE Task Force commander to request ALAMO Force for an additional American regimental combat team. General Fuller’s suspicions concerning Japanese reinforcements were correct. Unknown to the HURRICANE Task Force, the Japanese had developed and partially executed ambitions plans for the reinforcement of Biak.30