Chapter 16: Biak: The Reduction of the Japanese Pockets

When General Eichelberger assumed command of the HURRICANE Task Force on 15 June, he chose to make no changes in plans General Doe had already made for an attack north of Mokmer Drome the next day. Instead, the new task force commander decided to observe operations on the 16th and await their outcome before determining what new courses of action might be necessary.1

The Reduction of the West Caves

When operations along the low ridge above Mokmer Drome had ended in frustration on the afternoon of 15 June, General Doe had decided to give the tired 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 162nd Infantry, a rest while the 2nd Battalion, 186th Infantry, made a new effort to close the 500-yard-long gap which still existed along the low ridge. The 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was to aid this effort by sending patrols southwest from its perimeter near the West Caves. The 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, located northeast of the West Caves, was to secure the lower end of the road west of Hill 320 with the aid of elements of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, from the east. The 3rd Battalion, 186th Infantry, would remain in reserve.2

The Attack Continues

The 2nd Battalion, 186th Infantry, started moving toward the low ridge at 0700 on 16 June and by 0815 had relieved the two companies of the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, which had been holding positions on the low ridge west of the point where the Japanese road crossed.3

The 186th Infantry’s unit began attacking eastward along the ridge shortly after 0900. Company E led, with the 2nd Platoon

on the ridge, the 3rd Platoon in flats 100 yards to the north, and the 1st Platoon 100 yards beyond the 3rd. The 2nd Platoon quickly found itself in a maze of Japanese positions and was halted by Japanese automatic weapons fire. The 1st Platoon of Company G thereupon moved up on Company E’s right and began advancing along the southern slope of the low ridge. Together, the two platoons continued eastward against slackening resistance. They cleared innumerable enemy slit trenches, foxholes, and bunkers, destroyed several machine guns of various calibers, and at 1050 reached the lines of the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry. The task of closing the ridge line gap was completed in less than two hours, many of the previous Japanese defenders apparently having withdrawn north into the West Caves the preceding night.

In the flat ground north of the ridge, operations had not been so successful. The 3rd Platoon, Company E, gained about 500 yards in an easterly direction but was then pinned down for almost two hours by Japanese machine gun and mortar fire originating from woods and high ground near the enemy encampment area north of the West Caves. The 1st Platoon, moving up to the 3rd’s left, was subjected to the same fire. Finally, the 2nd Platoon, Company G, was sent forward in an attempt to outflank the enemy positions north and northeast of the two Company E platoons. This maneuver was ineffective, and by 1115 all movement in the flat had bogged down. The battalion commander ordered a new attack with four rifle platoons (two each from Companies E and G) abreast with the intent of clearing the ground northeastward to the lines of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, north of the West Caves. The new advance, beginning shortly after 1200, followed a 600-round concentration by the 121st Field Artillery Battalion on the area whence the Japanese mortar and machine gun fire had originated.

The 3rd Platoon, Company G, aimed for the high ground at the Japanese encampment. Crossing the main road which ran north from Mokmer Drome through the bivouac area, the platoon secured its objective shortly after 1400, bringing to a halt most of the automatic weapons fire which had prevented the advance of the other three platoons during the morning. The 2nd Platoon, Company G, on the 3rd’s right, also crossed the road. As the platoon pushed on toward the northwest corner of the West Caves, it was halted by enemy fire, as was the 1st Platoon, Company E, 150 yards to the south. The 3rd Platoon of Company E, right of the 1st, advanced along the north side of the low ridge. There it encountered little opposition and, apparently passing south of the West Caves unmolested, established contact with the 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, about 1400.

The 1st Platoon of Company E and the 2nd Platoon, Company G, had obviously located the western side of the West Caves positions. However, they could hardly be expected to seize a strong point which the 1st Battalions of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments had been vainly trying to secure from the east for the past two days. They therefore established a line on which a new attack into the West Caves might be based, and Colonel Newman ordered the forward elements to dig in for the night, pending the arrival of the rest of the 2nd Battalion. But General Doe thought there was danger that enemy units might counterattack the left rear (northwest) of the three forwardmost platoons. Indeed, as the three had moved up to the west side of the caves

Infantrymen moving up to the attack on a ridge north of Mokmer Drome. The tank is a Sherman

at 1400, a number of Japanese infantrymen had been observed milling around up the main road to the north. Therefore, about 1420, General Doe ordered all four platoons to withdraw to the low ridge. Beginning at 1830, the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, started forward to relieve the 2nd Battalion, 186th Infantry, and by 1900 the latter was back to the bivouac area it had left at 0700.

The unit could look back on the day’s operations with a good deal of satisfaction. It had closed the gap on the low ridge; it had located the western limits of the enemy’s West Caves positions; it had discovered that more Japanese troops were located north of the enemy encampment area both along the main road and on ridges west and northwest of Hill 320; it had eliminated most of the machine gun nests and rifle pits in the encampment area and many of those on high, forested ground near that bivouac; it had destroyed many Japanese automatic weapons and rifles; and it had killed at least 65 Japanese. The 2nd Battalion itself had lost 15 men killed and 35 wounded. There had been only local patrolling by the rest of the units in the forward area during the day, for the 1st Battalions of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments had been kept in place by American artillery and mortar fire which supported the operations of the 2nd Battalion, 186th Infantry.

For the 17th General Doe planned to send the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry,

northwest to high ground at the Japanese encampment area while the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, pushed south and southwest to the West Caves. Ten tanks, two field artillery battalions, and a company of 4.2-inch mortars were to provide close support.

On the morning of 17 June the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, in order not to overlap the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, took a circuitous route toward its objective, leaving its bivouac in an easterly direction and then swinging north to approach the high ground from the northeast. The 162nd Infantry’s battalion, supported by the 1st Platoon, 603rd Tank Company, started westward about 0945 with Company A in the lead and Company B echeloned slightly to A’s right rear.

At 1045 the two leading companies were stopped by heavy automatic weapons fire from the objective of the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry. Company C, 162nd Infantry, was then sent north toward high ground which had not been included in the area patrolled by Company G, 186th Infantry, on the 16th. Company C managed to knock out several pillboxes, but about 1140 it was forced back to the south. The tank platoon now moved up toward the high ground and succeeded in destroying an artillery piece and two machine guns, enabling Company C to renew its attack about noon. Simultaneously, the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, began approaching the high ground from the east. On that side there was little resistance, and at 1330 Company A reached Company C, 162nd Infantry. The latter unit, which had been continuing its efforts from the south, had just succeeded in reducing the last important enemy position on the hill.

Companies A and B, 162nd Infantry, now resumed the attack westward but soon were subjected to scattered rifle and machine gun fire from positions southwest of Company C. These positions had been cleared on the 16th by Company G, 186th Infantry, but had been reoccupied during the night by the Japanese. Company C, 162nd Infantry, was called back from the hill it had just helped to secure and started reclearing high ground from which the new fire originated. Minor gains were achieved the rest of the afternoon, and at dark the 1st Battalion set up defenses in a long, L-shaped perimeter with Company C on the north, about 75 yards from the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, which was also digging in for the night. About 125 yards of Japanese-held territory lay between the south flank of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, and the low ridge above Mokmer Drome.

Preparations For a New Attack

The 1st Battalions of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments had gained high ground overlooking the West Caves and were in a favorable position from which to launch a concerted attack on that enemy strong point. General Doe had such a plan. He intended to send the entire 162nd Infantry to clean out the West Caves and, with the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry, to secure north-south ridge lines west of Hill 320. But this plan was canceled by General Eichelberger.

The latter had observed much of the action on the 17th from a vantage point on high ground and had not been satisfied with the results. He therefore called off all fighting for the 18th—Sunday—in favor of reorganization and redispositions in preparation for a coordinated attack by the entire 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments on the 19th. The new attack was to drive the Japanese from all terrain whence they could

fire on Mokmer Drome and was to secure favorable ground from which to launch future advances designed to eliminate the last Japanese resistance around the three airfields.4

The first area to be cleared included the West Caves, the Japanese encampment area, and all the ground north from the low ridge to Hill 320. The objective area was about 1,000 yards long southeast to northwest and some 500 yards wide. The main effort was to be made by the 186th Infantry, the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of which were to attack from the southwest and west while the 1st Battalion struck from the east. The 162nd Infantry would hold its positions. The 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, was to assemble along the northern slopes of the main ridge in the vicinity of Hill 320 to prevent the movement of enemy reinforcements from the north into the 186th Infantry’s zone. An egg-shaped terrain feature on the low ridge 1,000 yards northeast of Borokoe Drome and on the left flank of the 186th Infantry’s prospective line of advance was to be seized for flank security and as a line of departure for subsequent attacks north and northeast. The 34th Infantry of the 24th Division, scheduled to reach Biak from Hollandia on 18 June, would take over the positions west of Mokmer Drome which the 186th Infantry vacated. During the latter’s attack, the 34th Infantry was to be in reserve and would be ready to seize Borokoe and Sorido Dromes upon orders from General Eichelberger.5

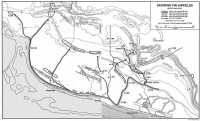

On 18 June only local patrolling was undertaken, while the bulk of the troops rested or redeployed in preparation for the attack on the 19th. (Map 16) The egg-shaped feature was secured against no opposition and a few Japanese stragglers along the low ridge in the area were mopped up. The 34th Infantry began moving into the Mokmer Drome area and the 186th Infantry drew up final plans for its attack. The regiment was to advance east from the egg-shaped protrusion of the low ridge with the 2nd Battalion leading, two companies abreast. The 3rd Battalion was to follow the 2nd, and the 1st Battalion would start moving northwestward once the other two had begun moving east. The attack, which was to begin at 0630 on the 19th, would be supported by the 121st, 167th, 205th, and 947th Field Artillery Battalions, Company D of the 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and ten tanks of the 603rd Tank Company.6

The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 186th Infantry, had assembled at the egg-shaped feature by 0900 on the 19th. The terrain in the area was rough and overgrown and the two battalions took more time than expected to get into their proper positions for the attack. At 1040, after preparation fire by the four artillery battalions had ended, the 2nd Battalion started eastward, and the 3rd Battalion went into reserve 500 yards to the rear. Redeployments had been completed. The attack had started.7

The Fall of the West Caves

Company F, followed by Company G, was on the left, and Company E was on the

Map 16: Securing the Airfields, 18–24 June 1944

Map merged onto previous page

right.8 At 1105, having encountered only scattered rifle fire, Company F reached the motor road running from the Japanese encampment area generally northwest along the base of a rugged, heavily forested coral ridge lying west of Hill 320. Company E pulled up on the road to F’s right five minutes later. The battalion objective was a long, narrow, and sharp rise which formed the first slope of the coral ridge.9 As Companies E and F began moving toward this first crested rise, fire from Japanese 90-mm. antiaircraft guns in an unlocated emplacement to the north began falling near the leading troops and along the road. But the two companies pressed on and reached their objective about 1130. The 3rd Battalion quickly pulled up on the 2nd’s left.

About noon Colonel Newman ordered the 1st Battalion to clear the southern extension of the coral ridge line and to push through the Japanese encampment area up the road to the 2nd Battalion’s position. This movement was under way by 1230, and late in the afternoon the 1st Battalion (less two rifle companies) reached the 2nd’s right flank. The other two companies, advancing over rough and heavily jungled ground below Hill 320, were unable to make contact with the rest of the regiment before dark and set up a night perimeter about 250 yards southeast of the remainder of the 1st Battalion.

Against only scattered resistance, the 186th Infantry had enveloped the rear of the Japanese in the West Caves and could prevent their reinforcement or escape. With one regiment thus athwart the enemy’s main north-south line of communication, the HURRICANE Task Force could turn its attention to securing the other airfields and clearing the West Caves. Accordingly, General Eichelberger issued a new attack order late on 19 June. The 186th Infantry was to continue its operations in the Hill 320 area and the ridges to the west, aided by the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry. The 162nd Infantry was to undertake the final reduction of the West Caves, while the 34th Infantry seized Borokoe and Sorido Dromes.10

On the morning of 20 June the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, and two tanks of the 603rd Tank Company moved to the surface area around the many caverns and sumps constituting the West Caves. It was found that the operations of the 186th Infantry had eliminated most of the Japanese from the high ground north and northwest of the

caves, and only occasional rifle shots from those directions harassed the 1st Battalion as it moved forward. But from a multitude of crevices and cracks around the caves, and from the interior of the sump holes themselves, came a great deal of rifle and light automatic weapons fire, and the battalion was unable to get any men down into the sump depressions. Drums of gasoline were rolled into many caves and then ignited in the hope that most of the Japanese would be killed. But the enemy fire continued almost unabated and the battalion withdrew to its previous positions before dark.

During the night, Japanese from the West Caves launched a number of small harassing attacks against the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, and, moving north up the main road, struck the south flank of the 186th Infantry. The enemy also dragged mortars or light artillery out of the caves and lobbed a few shells on Mokmer Drome and the road along the beach. Before daylight on the 21st, these Japanese and their weapons had disappeared back into the West Caves.

The 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, again moved up to the West Caves on 21 June and sent patrols out to clear Japanese riflemen from brush and crevices on hillocks north and northwest of the caves. The patrols, actually flame thrower teams supported by riflemen, accomplished their mission without much difficulty while the rest of the battalion, again covered by two tanks from the 603rd Tank Company, surrounded the sump depressions. The infantry and tanks concentrated on the most westerly of three large sink holes comprising the West Caves. The tanks fired into cave entrances; the infantrymen lobbed hand grenades into holes and crevices within reach; and all Japanese observed were quickly killed by rifle fire. But the battalion was unable to force its way into the main entrance to the underground caverns. Fire into this entrance was also ineffective, for the opening was shielded by stalagmites and stalactites. Engineers poured the contents of five gasoline drums into the cavern through crevices or seepage points found on the surface of the ground. Flame throwers then ignited the gasoline and the 1st Battalion withdrew to await developments. There were no immediately apparent results and, since it was believed that the West Caves were still strongly held, the battalion did not attempt to send any more men into the entrance. In the late afternoon the unit again pulled back to its bivouac area.

During the night of 21–22 June, Japanese poured out of the caves and rushed northwest up the road toward the lines of the 186th Infantry, attempting to escape to the west or north. At 2100 Japanese infantry, supported by light machine guns and light mortars, hit the southeast flank of the American regiment. When the Japanese were about fifty yards away, the 186th Infantry’s .50-caliber machine guns opened fire and broke up the attack. Undaunted, the Japanese made another break-through attempt about midnight, this time supported only by light mortars. Machine guns, both .50- and .30-caliber, aided by Company G’s 60-mm. mortars, forced the enemy to withdraw for a second time.

At 0400 on the 22nd the Japanese again attacked, now employing stealth, hand grenades, and bayonets as their principal weapons. The intensity of this final attack was such that the enemy reached the 186th Infantry’s foxholes, and hand-to-hand combat ensued all along the regiment’s south

flank. Since the enemy’s leading elements were so close, Company G’s mortars could not be used. Instead, the 60-mm. mortars of Company I, emplaced at the extreme northwestern end of the regimental perimeter, were brought into action to place their shells close to the regiment’s front lines and immediately to the rear of the leading enemy troops. This fire prevented the Japanese from sending reinforcements forward to aid their attack elements, and the battle, which was nip and tuck for about half an hour, quickly became disorganized and the enemy scattered. Individual Japanese infantrymen and small groups continued to attack in an un-coordinated fashion until daylight. Early in the morning, the 186th Infantry began mopping up southeast of the perimeter, killing a few Japanese who were hiding or playing ‘possum along the roadside. A final count revealed that 115 of the enemy had been killed, and it was believed that 109 of these had been slain during the reckless attacks beginning at 0400. The Japanese attackers had numbered about 150, according to Japanese sources. The 186th Infantry lost only 1 man killed and 5 wounded during the night.

The 162nd Infantry had by no means spent a quiet night, for other parties of Japanese from the West Caves had attacked the 1st Battalion and also Company F, which was located on the low ridge southwest of the sump holes. Most of the enemy activity was confined to the front of Company A, against which small groups of Japanese, armed only with rifles and hand grenades, moved beginning about 0200. But the Japanese did not attempt to press home their attacks, which in this area were probably only covering operations for the main assault against the 186th Infantry. The 162nd Infantry killed seventeen Japanese during the night but suffered no casualties itself.

The attacks during the night of 21–22 June had apparently resulted from a decision on the part of Colonel Kuzume, Biak Detachment commander, to acknowledge defeat. In an impressive ceremony in the West Caves, Colonel Kuzume, surrounded by his staff, burned the colors of the 222nd Infantry and, according to some American reports, disemboweled himself in the tradition of the Samurai. Japanese reports of the Biak action state that Colonel Kuzume did not die then but was killed in action or committed suicide some days later. Whatever the cause and date of his death, on the night of 21–22 June Colonel Kuzume had instructed the forces remaining in the West Caves to withdraw to the north and west. Many of the remaining troops of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 222nd Infantry, who had originally held the low ridge north of Mokmer Drome, had already been killed or had moved north, and most of the Japanese killed by the 186th Infantry during the night of 21–22 June were identified as members of the 221st Infantry, elements of which had been included in the reinforcements sent to Biak after Z Day.

While it was believed that the Japanese force which attacked the 186th Infantry represented the bulk of the enemy troops remaining in the West Caves, the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, soon found that opposition had not ended. As the battalion approached the caves early on the morning of 22 June, it managed to catch out in the open a number of Japanese who had been manning heavy weapons during the night attacks and who had not had time to move themselves and their weapons back into the caves. After killing these enemy troops the

battalion again moved up to the sink hole rims, which were found littered with enemy dead.

During the morning a number of explosions were heard inside the caves, and it was considered probable that gasoline, still burning after being poured into the caves the previous day, had reached some ammunition dumps. Again flame throwers were used, although these weapons had not proved very effective because they had a tendency to flash back on the operators from the cave walls. Finally, a demolition detail from the 116th Engineers lowered two 500-pound charges of TNT into one of the cave entrances. The explosives were fired electrically. A few Japanese, at least one of whom had been driven insane by the explosions, came running out of the caves and were quickly killed. At 1555 the 1st Battalion, having heard no signs of enemy activity from within the caves for the previous two hours, reported that the caves had been cleared out.

This report was proved optimistic during the night of 22–23 June when another small group of Japanese unsuccessfully tried to break through the lines of the 186th Infantry. The 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, itself killed seven Japanese who attempted to move from the caves to Hill 320. The next morning the battalion established a permanent bivouac around the various caves and depressions and continued to probe the area. The remaining Japanese were capable of defending themselves, hopeless though their situation was, and no troops were able to enter the caves until the afternoon of 25 June. No deep penetration was attempted, however, and it was not until 27 June that patrols of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, accompanied by members of the 41st Counter Intelligence Detachment, penetrated to the innermost recesses of the West Caves.

The stench of rotting Japanese bodies was revolting, and the sight nauseating. The entire cave area was strewn with Japanese bodies or parts of bodies. One gruesome area had apparently been used as an aid station and another possibly as a butcher shop for cannibalistically inclined survivors of the carnage since 18 June. Three more Japanese were killed in the caves during the day, and large quantities of equipment and documents were found. Because of the advanced stage of decomposition of many of the dead, a complete count of Japanese bodies could not be made, but before overpowering odors drove the patrols out of the caves 125 more or less whole bodies were counted. This was considered a minimum figure, for no estimate could be made of the numbers of Japanese represented by separated arms, legs, or torsos and it was impossible to guess how many Japanese had been sealed in smaller caves or crevices by artillery and mortar fire or by explosions of TNT and Japanese ammunition within the caves.

The number of Japanese dead left within the West Caves was not of great moment, but it was important that the last position from which the enemy could seriously threaten Mokmer Drome had been secured. Even before the West Caves had fallen, the operations of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments had so reduced Japanese fire on the airdrome that on 20 June, after six days of inaction, the 863rd Engineer Aviation Battalion was able to resume work on the field. Two days later, Fifth Air Force P-40’s began operating from the 5,000-foot-long completed section of the strip. One of the three fields on Biak was at last operational.11

Entrances to the West Caves

Securing the Western Area

Operations to drive the Japanese from positions they still held north and west of the West Caves had begun on 19 June when the 186th Infantry moved into the ridges west of Hill 320. They continued on 20 June when the 34th Infantry, supported by the 167th Field Artillery Battalion, occupied Borokoe and Sorido Dromes and Sorido village almost without opposition. To prevent more enemy reinforcements from reaching the battle area, Company I, 34th Infantry, set up a road block at a trail junction about 3,000 yards north of Sorido. The rest of the regiment outposted the road back to Sorido, trails along the southwest coast of Biak, and the low ridge west of the egg-shaped feature over which the 186th Infantry had passed on 19 June.12

Hill 320 and The Teardrop

When the 186th Infantry reached the base of the ridge west of Hill 320 on 19 June, it had blocked the road running south to the West Caves by placing on the road and along the western slopes of the ridges all three battalions, in order from south to north, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd.13 The regiment was to clear the high ground east to Hill 320 and patrol north and east to maintain contact with elements of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry. The latter unit was holding the crossing of the main ridge which the 186th Infantry had used on 7 June, maintaining an outpost on Hill 320, and patrolling north along the main ridge from the crossing and south from the same point toward the East Caves. On the morning of the 20th, for unknown reasons, the outpost on Hill 320 moved north off that terrain feature. General Eichelberger, concerned lest the Japanese occupy Hill 320 and subject the 186th and 162nd Infantry Regiments to enfilade fire, immediately ordered the hill reoccupied. Fortunately, the Japanese did not discover that the hill had been abandoned, and Company L, 163rd Infantry, restored the outpost during the afternoon.

Patrolling by the 186th Infantry and the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, on 20 June produced no traces of large concentrations of Japanese troops. However, on the western slopes of Hill 320 and on a long, forested ridge running north from the 186th Infantry’s bivouac area, a number of abandoned enemy positions were located. Off the northwest corner of Hill 320 was discovered a cul-de-sac over 300 yards long north to south, some 100 yards wide, and open only on the north. Japanese machine gun nests were located on ridges along the west side of this cul-de-sac which, because of its shape, was called “The Teardrop” by American troops. Colonel Newman proposed that on 21 June the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, move into The Teardrop from the northwest and north while the 186th Infantry maintained pressure from the south and southwest. This plan was based on erroneous information concerning the location of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, which was actually patrolling in thickly jungled

flats two or three miles due north of The Teardrop. The unit could not, therefore, mount any attack into The Teardrop and did not even establish patrol contact with the 186th Infantry from the north until 23 June.

Meanwhile, the 186th Infantry had discovered new Japanese positions northwest of its perimeter and on 22 June was harassed by fire from two or three enemy 75-mm. guns from a point some 750 yards away in that direction. Efforts to capture the guns on 22 and 23 June were unsuccessful, but on the 24th Companies L and K, 186th Infantry, supported by two tanks and the 947th Field Artillery Battalion, managed to get within a few yards of the enemy weapons. The next day Company L overran the gun positions, capturing one Japanese artillery piece and finding four others destroyed by friendly artillery fire.

Back at The Teardrop patrolling had continued at a slow pace. On 23 June new low-level aerial photographs of the area were examined at regimental headquarters. After all patrol leaders who had led men into The Teardrop during the previous days had delivered their interpretations of the new pictures, it was concluded that the principal Japanese positions in the cul-de-sac were on the west rather than the east side, as had been believed previously. Colonel Newman, who had waited in vain for three days for the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, to attack from the north and northwest, therefore proposed an attack from the west. General Doe approved this proposal and on the morning of 24 June the new attack began.

The 2nd Battalion, 186th Infantry, moved north some 500 yards up the road along which the regiment was bivouacked and sent Company E east over the ridges toward The Teardrop’s northern end. Broken terrain and heavy jungle delayed the company’s progress, and it was midafternoon before the northwest corner of the Japanese positions was located. On the same day Company K, 163rd Infantry, sealed the northern exits of The Teardrop, and Company C of the same regiment took up new positions on the east side. By nightfall, all routes in and out were closed. The stage was set for final mopping up.

Early on the 25th Company E, 186th Infantry, overran the enemy defenses on the west and northwest, while Company A pushed into The Teardrop from the south, quickly establishing contact with the 2nd Battalion unit. The entire area was carefully combed during the rest of the day, but no signs of organized resistance could be found. Most of the Japanese positions had been evacuated two or three days previously—a large and well-armed enemy force had extricated itself from an almost impossible position. Had earlier efforts of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, to block the northern exits of The Teardrop been successful, the story might have been different. As it was, only thirty-eight Japanese were killed or found dead in The Teardrop area during the day. A Japanese force probably over 200 strong had escaped.

Mopping Up in the Western Area

During operations at The Teardrop, the HURRICANE Task Force headquarters had drawn up plans for mopping up west of Mokmer. The 41st Division, less the 163rd Infantry but with the 34th Infantry attached, was to secure the entire area west of Mokmer village to Impendi, a native settlement on the coast about five miles west of Sorido village. The northern boundary of the division’s zone generally followed the

main coastal ridge from Impendi to Mokmer. The 34th Infantry (less the 1st Battalion) was to secure the area west of and including Borokoe Drome; the 186th Infantry, with the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, attached, was to clear the terrain from Hill 320 north to high ground about 2,000 yards distant; and the 162nd Infantry, assembling near Mokmer Drome, was to send one company to Hill 320 to replace 163rd Infantry units there. The 163rd Infantry was made responsible for securing the area east of Mokmer village.14

On 26 June the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, less Company C, occupied abandoned enemy positions on a long finger-like ridge running north from the northwest corner of The Teardrop. Company C, which had taken a different route north, was ambushed by a Japanese force of unknown strength and pushed back south, but rejoined the rest of the battalion the next day. From reports brought back by 1st Battalion patrols sent north on the 27th, it was concluded that a Japanese unit was preparing for a determined stand along, or a suicidal counterattack from, sharp cliffs northwest of the battalion area. General Doe therefore assigned the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 34th Infantry, the task of clearing the cliff area, the 2nd Battalion to move in from the southwest and west, while the 1st Battalion approached from the southeast.15

On 28 June the 2nd Battalion, 34th Infantry, encountered little opposition as it mopped up in flats south of the cliffs but Company A, moving west from the 1st Battalion area into terrain between the 1st and 2nd Battalions, was attacked by a group of Japanese who were apparently trying to break out of the trap the two American battalions were forming. At 1600 the company was forced back to the battalion command post area, where it dug in for the night. Most of the Japanese met in the area were probably members of the Nishihara Force of the 219th Infantry.16

General Eichelberger, who had known for some time that he was to return to Hollandia when he thought that the most important areas on Biak had been secured, decided on 27 June that he could leave and took his departure on the 28th. General Doe took over command of the HURRICANE Task Force, retaining his command of the 41st Division. On the same day, information was received from higher headquarters that the 34th Infantry would soon have to be pulled out of action and assembled as ALAMO Force Reserve for another operation. Redispositions on Biak were necessary.17

General Doe decided to give the 34th Infantry two days to complete mopping up north of the 186th Infantry, after which it would assemble on the beach south of Borokoe Drome. The 41st Division would then redispose itself along main and reserve lines of resistance to prevent further Japanese interference with the development of air and logistic bases on Biak. The main line of resistance began on the west at Sorido village,

followed the main ridge east to Hill 320, then ran east along the supply road which the 186th Infantry had constructed through the flats north of the main ridge during the first week of June, and finally curved southeastward to end on the beach at Opiaref. The reserve line of resistance followed the low ridge north of the airfields to the East Caves and then ran along the north side of the main ridge to Opiaref. The 162nd Infantry was to hold the area west of Borokoe Drome, the 186th Infantry the area east to Mokmer village, and the 163rd Infantry the ground from the East Caves to Opiaref.18

On 29 and 30 June only the 2nd Battalion, 34th Infantry, located any signs of organized resistance in the area north of the 186th Infantry, and during the two days killed or found dead about 135 Japanese, most of them poorly armed and incapable of strong resistance. On the afternoon of the 30th, all elements of the 34th Infantry began withdrawing to the beach while the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments began taking up planned positions along the main and reserve lines of resistance, from which they instituted patrolling designed to hunt down enemy stragglers and prevent scattered elements of the Biak Detachment from reorganizing for harassing raids or suicidal attacks.19

The Biak Detachment remnants had been moving north since 22 June in a withdrawal that apparently had been directed by Colonel Kuzume on his own initiative. Another mass withdrawal was begun on the 28th, the day General Eichelberger left Biak. This second withdrawal was started upon orders from the 2nd Area Army, which instructed the Biak Detachment to reorganize for guerrilla warfare.20 Whatever he hoped to accomplish by guerrilla action, General Anami was to be disappointed. The remnants of the Biak Detachment had lost most of their supplies and for the remaining Japanese it was soon to become a case of sauve qui peut. Aggressive patrolling instituted by the HURRICANE Task Force on 1 July was to prevent any reorganization for guerrilla warfare on the part of the Biak Detachment.

The Reduction of the East Caves

The fall of the West Caves on 27 June and the completion of mopping up operations by the 34th Infantry on 30 June marked the end of the most important phase of the Biak operation. The airdromes, to secure which Allied forces of the Southwest Pacific Area had landed on Biak on 27 May, were now safe, and Allied aircraft were already operating from Mokmer Drome. But the Japanese still held the East Caves and the Ibdi Pocket. True, these positions now had little more than nuisance value, and during operations in the Mokmer Drome area they had been kept fairly well neutralized by artillery and mortar fire. Until both areas could be cleared, however, the coastal road from Bosnek to the airfields would not be entirely safe, for the road could be subjected to harassing fire and raids which would impede the transportation of important supplies and equipment to the airfields.

The most significant part of the East Caves, tactically speaking, was the flat ledge about three quarters of the way to the top of the main ridge immediately north of

Mokmer village. On this ledge were located two large depressions similar to the sumps of the West Caves. Both of these depressions were at least 50 feet wide, and one of them measured roughly 75 by 200 feet. Each was honeycombed with tunnels, at least one of which led to a large opening on the seaward side of the ridge. This opening, with other unconnected caves and crevices on the seaward face, held some of the most troublesome Japanese weapons. Near the main sumps were two Japanese observation posts from which an unobstructed view of the coastal area from Parai Jetty to the eastern end of Mokmer Drome could be obtained. Behind the sumps, up the slope to the top of the ridge, were five strong pillboxes which were held by riflemen and machine gunners. In the sump holes were 81- or 90-mm. mortars, 20-mm. antiaircraft guns, heavy machine guns, and numerous light mortars. There were tents in the larger caves and tunnels, and quantities of food and clothing were stored in some tunnels.21

Information concerning the Japanese order of battle in the East Caves is contradictory and incomplete, and it appears that at the time of the landing few troops were actually stationed there. The 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, had used the area as a base of operations on 28 and 29 May, when the HURRICANE Task Force discovered the existence of the caves during the Japanese counterattacks which had driven the 162nd Infantry back to Ibdi. After that action nearly 1,000 Japanese were left in the East Caves. Included were some 300 naval troops, most of them from antiaircraft or service units. The 500-odd army troops comprised mostly airdrome engineers who were reinforced by a mortar unit of the 2nd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, and a few riflemen of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 222nd Infantry. Finally, there were about 200 Japanese civilian laborers. The forces were under the control of a Lieutenant Colonel Minami, the commander of the 17th Field Airdrome Construction Unit.22

What happened in the East Caves from 29 May to 7 June is unknown, but on the latter day, as the 186th Infantry moved over the main ridge to Mokmer Drome, the position came to life and from it mortar and machine gun fire was directed on the Americans at the airfield. As the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, tried to move east during the next two days, it was pinned down by this fire, as were elements of the same regiment attempting to move west from Parai. Companies of both the 186th Infantry and the 162nd Infantry were sent north from the Mokmer Drome area toward the East Caves during the period 9–11 June, but these units had not closed with the main Japanese positions when, on the 11th, they were called back to join their regiments at Mokmer Drome. During the same days, a company of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, patrolled south toward the East Caves from the inland flats. At the end of the period all this patrolling had succeeded in locating the west flank of the enemy’s principal positions, destroying a few machine guns and some large mortars, and killing perhaps fifty Japanese.23

Since it was more urgent to secure the Mokmer Drome area than to clear the East Caves, no large infantry force could be committed to the latter mission and, therefore, more attention was devoted to neutralizing the East Caves with artillery, mortar, and naval fire. From 7 through 10 June the 4.2-inch mortars of the 2nd Platoon, Company D, 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion, lobbed over 1,000 shells into the East Caves area. On the 9th and 10th, tanks in LCTs cruising offshore added their fire, and on the latter day the 205th and 947th Field Artillery Battalions swung into action against the East Caves.24 Bombardments by artillery, mortars, tanks (both on the ground and afloat), and destroyers continued from 11–13 June, but the Japanese still managed to deny to the HURRICANE. Task Force the use of the coastal road during much of the period. In between artillery and naval gunfire concentrations, elements of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, probed more deeply into the Japanese positions from the north and northeast and located the north flank of the main enemy defenses. By noon on the 13th, the combination of American fire and infantry action had succeeded in silencing enough of the Japanese fire so that truck convoys could safely use the coastal road without interruptions for the first time.25

Infantry patrolling and all types of bombardment continued from 14 through 23 June, but the Japanese still occasionally harassed truck convoys along the coastal road. On the 23rd or 24th (the records are contradictory) there was undertaken a series of aerial bombardment missions which are among the shortest on record. Fifth Air Force B-25’s, based on Mokmer Drome, took off from that field to skip-bomb the East Caves. Although most of the bombs missed the main sump holes, the air missions did cause many explosions and started a number of fires in the East Caves. For a few days, at least, almost all the enemy fire was silenced.26

On 27 June Company E, 542nd Engineer, Boat and Shore Regiment, started to construct a jetty near Mokmer, and in connection with this mission began working a gravel pit at the base of the ridge northwest of the village. Japanese mortar and rifle fire from the East Caves impeded the latter work and on 29 June 4.2-inch mortars and tanks had to be moved back into the area to shell the caves and protect the engineers. Within three days the mortars fired over 800 rounds into the caves. The engineer company, borrowing bazookas from an infantry unit, sent its own patrols into the caves, and Company I, 163rd Infantry, sent patrols back into the area from the north.27 On 30 June the 205th Field Artillery Battalion sent one gun of Battery C to a position near Mokmer village to place about 800 rounds of smoke and high explosive shells into the caves.

Light harassing fire continued, however, and on 3 July elements of Company E, 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment,

Entrance to the East Caves

moved into the caves under cover of tank fire from the base of the ridge. Some tunnels were sealed shut, twelve Japanese were killed, and two light machine guns were captured.28 Almost simultaneously, Company E, 163rd Infantry, pushed into the caves from Mokmer village. Neither the engineer nor the infantry unit met as much resistance as had been anticipated. Patrolling throughout the caves was continued on the 4th and 5th, and on the latter day a platoon of Company E, 163rd Infantry, entered the larger sump holes, where were found many automatic weapons, mortars, rifles, all types of ammunition, food, clothing, cooking utensils, and pioneer equipment. The next day loudspeakers and interpreters were sent into the caves to persuade the few remaining Japanese to surrender. Only ten Japanese, of whom eight were killed, were seen in the area. The Japanese who had lived uninjured through the heavy bombardments since 7 June had evacuated the East Caves.29

Japanese evacuation had started about 28 June, on which day Colonel Minami

committed suicide and outposts of the 163rd Infantry began reporting that small groups of enemy were escaping over the flats north of the main ridge, and all but about forty sick or wounded had left before 3 July. Why the Japanese evacuated is not known but, in any case, the enemy had not been making efficient use of the troops in the East Caves since 10 June. After that date the Japanese had fired principally on targets of opportunity moving along the coastal road, and this fire soon deteriorated into the light harassing type. Had the Japanese properly used their East Caves weapons, they could have denied use of the coastal road to the HURRICANE Task Force for a much greater period of time and might have made it necessary for the task force to divert large infantry units from the vital airdrome area.

The reasons for the enemy’s apparent listlessness in the East Caves are difficult to fathom. From the amount of ammunition, food, and clothing captured there, it is clear that a shortage of supply was not a major problem. It is possible that there was no unified command in the caves; perhaps the service troops did not know how to use the weapons properly; or it may be that Allied artillery, mortar, air, tank, and naval bombardment kept the enemy stunned and under cover. Whatever the reason, the Japanese chose to evacuate rather than use their weapons effectively.30

The few Japanese left alive in the East Caves after 6 July were still capable of causing some trouble. On 15 July six souvenir hunters of the Royal Australian Air Force (elements of which were staging through Biak for operations farther west) were killed near the caves. Tanks and infantry were sent into the area to mop up the remaining Japanese and recover the Australian dead. On the 16th and 17th, three badly mutilated bodies of Australian airmen were found and two Japanese machine gun nests were wiped out. On the 20th the infantry and tanks returned to the caves, found the other Australian bodies, and eliminated the last enemy resistance.31

The Reduction of the Ibdi Pocket

The fall of the East Caves left the Ibdi Pocket as the only remaining center of organized Japanese resistance on Biak.(See Map V.) Operations against the Ibdi Pocket had been started on 1 June by the 162nd Infantry in conjunction with the 186th Infantry’s inland drive to Mokmer Drome. The 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, had fought its way through the Ibdi Pocket via Young Man’s Trail on its way north to join the 186th Infantry inland, while the rest of the 162nd Infantry, with Company A, 186th Infantry, attached, had remained on the coastal road to start a drive westward along the beach. But the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, reinforced by elements of various engineer and other service units, as well as some artillery, firmly ensconced in Ibdi Pocket positions, had had other ideas, for Colonel Kuzume had ordered the unit to hold the coastal approaches to Mokmer Drome.

Operations of the 162nd Infantry at the Ibdi Pocket

When, on 1 June, the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, started north, the rest of the regiment patrolled westward from Ibdi, sent

small patrols north into the ridges to protect the rear of the 2nd Battalion, and endeavored to hold a water hole at the beach terminus of Old Man’s Trail, 1,200 yards east of Young Man’s Trail.32 At 1450 on 1 June about fifteen Japanese from the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, drove the Cannon Company, 162nd Infantry, away from the water hole and established a road block on the main coastal road. At the same time Japanese mortar and artillery fire drove off the tanks of the 3rd Platoon and Headquarters, 603rd Tank Company, initially located 300 yards west of the water point. To escape from their exposed position, the tanks moved east through the enemy road block toward Bosnek, but were unable to force the Japanese away from the water hole.

On the morning of 2 June the Cannon Company, 162nd Infantry, and Company A, 186th Infantry, cleared the road block and retook the waterhole, killing some of the Japanese in the area with rifle, mortar, and machine gun fire and driving the rest up the ridges into the Ibdi Pocket. The Antitank Company, 162nd Infantry (which, like the Cannon Company, operated as a rifle company throughout the Biak operation) set up a trail block on Young Man’s Trail atop the third of the seven ridges which constituted the main coastal ridge at Ibdi. The regimental attack westward had meanwhile been postponed until the morning of 3 June, pending the outcome of the fight at the waterhole and the 2nd Battalion’s movement over Young Man’s Trail to join the 186th Infantry.

Action on 3 June started earlier than anticipated when, before daylight, elements of the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry. pushed the Antitank Company back to the beach. Between them, the Antitank and Cannon Companies managed to secure Young Man’s Trail back to the top of the second ridge line during the day. The 3rd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, had meanwhile started westward, intending to clear the coastal road as far as the stream crossing located about halfway through the Parai Defile. By 1300, patrols of the 3rd Battalion had moved past the stream crossing to a fork in the coastal road about 900 yards east-northeast of Parai Jetty. Then enemy fire from the cliffs on the right and from high ground to the northwest pinned down the entire battalion, and Japanese infantry, infiltrating through a narrow stretch of dense woods between the road and cliff, cut off the point platoon. With the aid of two tanks, the forward platoon managed to extricate itself. During the withdrawal a Japanese soldier climbed atop one of the tanks and dropped a hand grenade into the driver’s hatch. The driver was killed and the rest of the tank crew wounded, but the assistant driver managed to get the tank out. Meanwhile, the intensity of Japanese fire on the rest of the 3rd Battalion had increased, despite artillery concentrations on the enemy cliff positions. About 1635 the battalion started to withdraw and by 1700 had come out of the defile. Back at the Ibdi Pocket area Japanese fire had also increased, and small parties of Japanese had harassed the 1st Battalion all afternoon.

The task force commander now decided that the Ibdi Pocket area would have to be

cleared before the coastal attack could be resumed. Accordingly, the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was instructed to clear all enemy from the ridge lines east of Young Men’s Trail, where the principal enemy strong points were thought to be located. The Antitank and Cannon Companies were to drive west from the trail while the 3rd Battalion remained at the eastern entrance to the Parai Defile and sent patrols to the northwest and through to the stream crossing.

The 1st Battalion started its attack at 0800 on 4 June, pushing two companies north along Young Man’s Trail. By noon one company had reached the sixth of the seven separate ridges over which the trail passed, but progress to the seventh was impossible, as was movement east toward Old Man’s Trail. During the afternoon, after pushing over extremely rough terrain, one rifle platoon finally reached Old Man’s Trail via the second ridge line. Other elements of the 1st Battalion could gain little more than 150 yards east from Young Man’s Trail over ridge lines 3 through 6. The Cannon and Antitank Companies had been unable to move west from the trail, and 3rd Battalion patrols had made little progress in the Parai Defile.

During the next morning the 1st Battalion succeeded in clearing all Young Man’s Trail and established patrol contact on the inland flats with the 186th Infantry. Little more progress could be made west of the trail or in the area between it and Old Man’s Trail. Patrols sent along the ridge lines east of the latter discovered no Japanese, but late in the afternoon a Japanese strong point in caves near the north end of Old Man’s Trail was located. Meanwhile, the 3rd Battalion had begun another effort to break through the Parai Defile, supported this time by fire from offshore destroyers, a rocket LCI, and craft of the Support Battery, 2nd Engineer Special Brigade. All this support proved unable to reduce much of the Japanese fire which was directed against the 3rd Battalion from the north, northwest, and west, and, except for outposts left near the stream crossing, all units withdrew to the battalion perimeter for the night.

On the 6th, the 1st Battalion cleared many positions on ridge lines 4 through 7 between Young and Old Man’s Trails, but was unable to dislodge the Japanese from the strong point near the north end of the latter track. Company A, 186th Infantry, and the Antitank Company, 162nd Infantry, attacked west from Young Man’s Trail and gained about 900 yards before being stopped in front of previously unlocated Japanese defensive positions. The two units held for the night along the first four ridge lines, directly north of the 3rd Battalion’s beach perimeter. The latter unit again had made no appreciable progress in the Parai Defile.

Meanwhile General Fuller had evolved his plan to move the 162nd Infantry to Mokmer Drome to reinforce the 186th Infantry and to clear the Parai Defile by simultaneous pressure from the east and west.33 On 7 and 8 June the bulk of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 162nd Infantry, moved overwater to Parai and ultimately west to Mokmer Drome. Back to the east, only Company A was left along Old Man’s Trail, where little resistance was encountered at the previous Japanese strong point after 7 June, although the position was not entirely reduced until 11 June. From 7 through 9 June the Antitank Company, 162nd Infantry, and

Company A, 186th Infantry, tried unsuccessfully to gain more ground along the ridge lines west from Young Man’s Trail. The units were pulled off the ridges on the 10th and relieved two days later by elements of the 163rd Infantry.

Generally, from 7 through 11 June, only moderate pressure was maintained against Japanese positions in the Ibdi Pocket area, major combat effort being diverted to clearing the last vestiges of Japanese resistance from the Parai Defile so that the coastal road could be employed for transportation of supplies to Mokmer Drome. The Cannon Company, 163rd Infantry, and the Antitank Company, 186th Infantry (both acting as rifle companies), began new pressure from the west against the Parai Defile on the evening of 7 June, while Company L, 162nd Infantry, continued attempts to push through from the east. By dusk on the 8th, despite the efforts of all three companies, the Japanese still maintained control of some 300 yards of ground in the defile. On the 9th, three Shermans of the 603rd Tank Company, aboard LCTs and directed from an LVT of the 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment, fired on the cliffs in the defile for an hour. This fire did not help the units on the west side of the cliffs very much, and infantry pressure was continued on the 10th. The next day a rifle company of the 1st Battalion, 162nd Infantry, attacked from the west into the defile while, simultaneously, the Antitank Company of the same regiment pushed in from the east. These attacks were finally successful, and by late afternoon on the 11th the road through the defile was clear of Japanese. Not until the 12th were the few remaining Japanese dispersed from woods north of the road, enabling truck convoys to move through the defile.

The 163rd Infantry at the Ibdi Pocket

On 12 June the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, arrived at Biak from the Wakde–Sarmi area and relieved those elements of the 162nd and 186th Infantry Regiments still holding positions at the Parai Defile and the Ibdi Pocket.34 The latter units then moved west to rejoin their parent regiments at Mokmer Drome, and responsibility for mopping up at the Ibdi–Parai area passed to the 163rd Infantry. With the clearing of the Parai Defile and the almost simultaneous reduction of Japanese fire from the East Caves, the road from Bosnek to the airfields was finally safe. At the Ibdi Pocket proper, the Japanese garrison had been generally quiet since 7 June except for a little harassing rifle and machine gun fire directed at Allied movements along the coastal road. Although the remaining Japanese were by now relegated to the status of a nuisance, the 163rd Infantry was going to find mopping up a difficult and time-consuming process.

From 12 through 20 June the 2nd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, undertook extensive patrolling in the Ibdi Pocket area to become acquainted with the terrain and situation in its new zone. The unit soon discovered that whatever positions had been held by the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, during the period of 162nd Infantry action, the remaining Japanese strong points were concentrated west

of Young Man’s Trail. Action against this pocket began on 21 June, when Company F attacked south from a point on the north side of the main ridge about 900 yards west of the trail. Japanese mortar, machine gun, and rifle fire forced Company F back and by noon it had become obvious that a single rifle company could not overrun the remaining pocket. The regimental commander decided to organize a larger infantry effort, in preparation for which extensive artillery and mortar bombardment was undertaken.

From the evening of 21 June through the night of 23–24 June the 146th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzers), the Cannon Company, 163rd Infantry, the 4.2-inch mortars of the 1st Platoon, Company D, 641st Tank Destroyer Battalion, and the heavy machine guns and 81-mm. mortars of Companies D and H, 163rd Infantry, bombarded the area steadily. Two infantry companies probed west from Young Man’s Trail on the morning of the 24th, only to find that the Japanese still held the remaining pocket in some strength. After two more days of artillery and mortar bombardment, four rifle companies were sent against the pocket. Moving slowly and painfully forward through tangled jungle undergrowth and fallen trees, and over jagged and precipitous coral spines, the four units gradually compressed the remaining resistance. By nightfall the assault companies had lost 8 men killed, 3 missing, and 32 wounded, while killing 38 Japanese.

The next day more units were brought forward until, by noon, almost all of the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 163rd Infantry, were in action against the pocket, and advances were continued over the ridge lines from both the east and west. By the end of the day, at the cost of 4 men killed and 14 wounded, the two battalions had compressed the Japanese into an area approximately 600 yards square. Attacks were continued on the 28th, but little more progress was made. By this time, steady attrition since 12 June, coupled with a lack of replacements was telling on the 2nd Battalion. Company F was now down to 42 effectives and Company G to 65.35

The 28th of June marked the end of large-scale infantry action at the Ibdi Pocket. Instead, extensive patrolling was undertaken in order to pin-point targets for artillery, mortar, and air bombardments. From 4 July to the morning of the 7th, for instance, the 146th Field Artillery fired over 5,500 rounds into the pocket and during the same period the 163rd Infantry’s 81-mm. mortars lobbed some 2,400 shells into the area. On the morning of the 7th an infantry company tried to move back into the Japanese-held area, but found the Japanese repairing old fortifications and even building new ones! Artillery and mortar bombardments were resumed, and on 9 July Allied Air Forces P-39’s and P-40’s dive-bombed and strafed the pocket area.

Companies K and L attempted to move into the pocket on the 10th and found that the Japanese defenders had thinned out. Moreover, they discovered the visibility in the pocket area had been greatly improved as a result of the long mortar and artillery bombardments. The once dense jungle and rain forest, in which visibility had previously been limited to ten yards, was now reduced to shattered stumps. From the 21st of June through the morning of 10 July the 146th Field Artillery Battalion alone had thrown

about 20,000 105-mm. shells into the Ibdi Pocket, and at least as many rounds had been fired by 4.2-inch, 60-mm. and 81-mm. mortars.

Beginning on the 11th, the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, steadily compressed the remaining Japanese into a smaller and smaller area. Bazookas and flame throwers were used to good purpose in close-in operations against bunkers, pillboxes, improved caverns, and small caves. Tanks fired their 75-mm. weapons at enemy positions now visible from the northern side of the main ridge, and on the 12th 155-mm. howitzers of Battery C, 947th Field Artillery Battalion, were brought forward to fire on the pocket. The next day about 200 Japanese, in four separate groups, sneaked through a net of ambushes and patrol bases set up by the 163rd Infantry on the flats north of the main ridge. Despite this exodus, which must have represented most of the remaining able-bodied members of the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, and its reinforcing units, American infantry moving back into the pocket on the 15th could not report that the going was much easier.

Artillery bombardment was resumed, and now the artillery could employ close-in precision fire where previously only area fire could be used because of the limited visibility. From 10 to 20 July the 146th Field Artillery Battalion threw in over 4,000 shells and Battery C of the 947th, fired 2,000 rounds into the pocket. On 22 July eight B-24’s swept over the pocket in three waves, dropping sixty-four 1,000-pound bombs. Artillery units followed with 1,000 rounds of 105-mm. and 275 rounds of 155-mm. ammunition, while the 163rd Infantry’s 81-mm. mortars threw uncounted shells into the pocket. These bombardments halted at 0945 on the 22nd and five minutes later two understrength companies of the 3rd Battalion, 163rd Infantry, started moving toward the enemy’s remaining defensive installations. The 1,000-pound bombs had paralyzed the Japanese, and the two American units encountered almost no opposition. At 1835 the 3rd Battalion commander reported that the Ibdi Pocket was cleared of all organized resistance.

The next day, final mopping up was begun, and engineer demolition experts were brought forward to seal caves and destroy the remaining bunkers and pillboxes. By dusk on the 28th, all positions had been rendered useless, enemy weapons either carried away or broken beyond use, and the last traces of resistance had disappeared. From 22 to 28 July, according to one estimate, about 300 Japanese were killed by bombardments and infantry action, or sealed in caves by the engineers. An actual count of dead bodies found during the same period came to 154 men. Whatever the correct figures, the Ibdi Pocket, initially manned by some 800 fresh, well-equipped men of the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, reinforced by about 200 troops of mortar, machine gun, artillery, and service units, was now finished.36

Upon examination after the battle the central portion of the Ibdi Pocket was found to cover a rectangle about 400 yards wide north to south and 600 yards long. In this area the Japanese had constructed defensive installations varying in type from heavily constructed pillboxes of log, coral, and concrete

to hasty trenches in the coral and brush. There were 21 major natural fortifications, including 4 large caves and 17 small ones. Caverns and crevices had been improved for defense and some were used as living quarters and aid stations. There were 75 well-constructed log and coral pillboxes, each having a capacity of 4 men, and among a few larger similar emplacements was 1 pillbox having 9 layers of logs. The minimum heavy armament, either found or estimated to have existed from scattered parts located during mopping up, was eight 90-mm. mortars, three 75-mm. mountain guns, two 37-mm. guns, two 20-mm. weapons, and three heavy machine guns. There were also several small mortars, numerous light machine guns, and over 100 rifles. These figures cannot be considered as representing the total enemy armament in the Ibdi Pocket. The 200-odd Japanese who had escaped on the 12th of July had carried many small arms with them, and other weapons had been so broken up by artillery, mortar, naval, and air bombardments that no accountable trace of them could be found. Still more were undoubtedly sealed in caves blown shut by engineer demolition experts from 22 through 25 July.

Though Colonel Kuzume’s defense of Biak was on the whole admirably executed, leaving the 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, isolated at the Ibdi Pocket after 10 June seems to have been a major mistake. By that date the bulk of the 162nd Infantry had moved on to the airfields and the value of the Ibdi Pocket as a coastal delaying position had been lost. Worse still, the 3rd Battalion did not use its available weapons and manpower to good advantage after 10 June. By placing concentrated mortar, automatic weapons, and artillery fire on Allied roads and supply dumps, the battalion and attached units could have made the coastal area from Parai east to Mandom difficult to hold and use. Instead, the troops in the Ibdi Pocket chose to conduct a passive defense. From a potentially dangerous threat, the pocket was relegated to the status of a localized nuisance which could be contained with a minimum of troops until the battle for the airdromes was over, when it could be reduced at leisure.

The tenacity of the Japanese defense of the Ibdi Pocket, though pointless and even wasteful after 10 June, was almost incredible, and it was not until the 1st Marine Division and the 81st Infantry Division met the 14th Division on Peleliu and Angaur, in the Palaus, that American troops were again to encounter such defense in similar terrain.37 The 3rd Battalion, 222nd Infantry, was both clever and fanatic on the defense. If holding the Ibdi Pocket had had any point after 10 June, its defense as executed might well have added a significant chapter to military annals.

The End of the Operation

Mopping Up

While the fall of the Ibdi Pocket marked the end of major organized resistance on Biak, there were still some 4,000 Japanese on the island who were capable of harassing American lines.38 It was obviously important

to prevent these Japanese from reorganizing for eleventh-hour suicide attacks. Operations with such an object in view had begun well before the Ibdi Pocket fell when the 186th Infantry, early in July, began patrolling far north of the main ridge toward the Sorido–Korim Bay track. A number of dispirited Japanese were chased away from or killed at native gardens far inland by both the 186th Infantry and the 162nd Infantry.

On 7 August the 2nd Battalion, 162nd Infantry, was started north along the Korim Bay–Sorido track to the Wafoerdori River, about midway between the track termini. There the battalion was to establish contact with elements of the 163rd Infantry, the 2nd Battalion of which had landed at Korim Bay from LCMs of the 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment on 2 August. Few Japanese were found in the Korim Bay area or south along the track to the Wafoerdori, where contact between the 162nd and 163rd Infantry Regiments was made on 15 August.

Apparently in a last desperate effort to delay complete Allied control over Biak, Biak Detachment headquarters, sometime in July, had ordered all remaining Japanese units to reassemble at Wardo Bay, on the west coast, by 15 August. The intent appears to have been to reorganize for a final counterattack. At least one unit still organized, comprising approximately 200 men of the 2nd Battalion. 222nd Infantry, ignored this order and continued to forage for itself in native gardens east of the Korim–Sorido track and some seven miles north of Mokmer Drome, but other enemy units attempted the trek from their scattered positions to Wardo Bay. The operations of the 2nd Battalions of the 162nd and 163rd Infantry Regiments along the Korim–Sorido trail had caught many of these units in transit and had split the remaining enemy forces.

The last hope that the Japanese might have had for reorganizing was dashed on 17 August, when the 1st Battalion, 186th Infantry (less Company B but with Company E attached), landed at Wardo Bay. Transported by LCMs of the 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment and supported by a short naval and air bombardment, the battalion moved ashore against negligible opposition. Subsequently, patrolling was undertaken north to Soepiori Island and south along the west coast of Biak. The coastal patrols and others sent inland pushed many Japanese southeast into ambushes maintained by the 162nd Infantry along the Korim–Sorido track. The Wardo Bay landing apparently broke whatever spirit the Japanese may have had left, and all enemy units rapidly split into small parties which wandered over the island in search of food.

While the three infantry regiments were directing their efforts toward breaking up real and potential enemy concentrations, other patrolling and mopping up was being undertaken on Soepiori Island by Netherlands Indies Civil Administration parties, groups from the Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service, and the 41st Reconnaissance Troop, all of which also operated in the southeast corner of Biak and along the Korim–Sorido track. Elements of the 163rd Infantry also patrolled in the southeast section of the island, where small boats manned by the 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment supported many patrolling operations. Netherlands officials brought the native population back under Dutch control as rapidly as each area was cleared of enemy troops. Some native laborers were supplied to the HURRICANE Task Force, and native

scouts proved of real help during mopping-up operations.

Medical Problems and Casualties

Medical units of the HURRICANE Task Force went ashore with the assault waves on 27 May and immediately began the work assigned to them. During the landings, wounded and injured personnel were taken aboard LSTs for treatment beyond first aid. When medical facilities were set up on the beach near Bosnek, casualties were treated ashore and then moved to LSTs for evacuation. Because of Japanese air and artillery action, evacuation hospitals and many other medical facilities were transferred to Owi when the latter island was secured. From Owi, casualties were transshipped to LSTs and later to larger ships. After the airdromes became operational air evacuation was employed.39

Within the HURRICANE Task Force there were 6,811 casualties from disease, aside from 423 hospitalized psychoneurosis cases. About 3,500 of the cases were diagnosed as “fever, undetermined origin,” and over 1,000 casualties resulted from an epidemic of scrub typhus. The first case of scrub typhus, a mite-borne disease, was diagnosed at the 92nd Evacuation Hospital on or about 1 July. From Owi Island, where the epidemic broke out, the disease spread rapidly to Biak, reaching its peak there during the last week of July. Stringent control measures designed to prevent the spread of typhus were quickly instituted. Clothing was impregnated with dimethyl-phthalate, bivouac areas were cleared of vegetation, rodents of all types were hunted down and destroyed, camp areas were kept scrupulously clean, and troops were kept out of the brush except when on combat duty.

During the first week of August, the incidence of scrub typhus began to decrease. Of the 1,000-odd cases to the 20th of the month, only 7 men died, a mortality rate of less than 1 percent. Although the death rate was extremely low, scrub typhus at Biak took a virulent form which made sufferers particularly ill. The majority of those taken sick were lost to service for four to six months, and many were expected to be relegated to a limited duty status.40

It is next to impossible to establish accurate battle casualty figures for the HURRICANE Task Force, but examination of all sources indicates that from 27 May through 20 August approximately 400 men were killed, 2,000 wounded, 150 injured in action, and 5 missing. In addition, sickness of various types accounted for 7,234 nonbattle casualties, many of whom were returned to duty. Thus, the total casualties of the task force were about 9,790 men. Of this total the three infantry regiments of the 41st Division lost 325 men killed and 1,700 wounded.41 Conflicting information provides a total of 4,700 Japanese killed and 220 captured on Biak through 20 August.

In addition, almost 600 Javanese and British Indian slave laborers were recovered, while 2 Chinese and 1 native of Guam were released from Japanese custody.42 The remaining Japanese were without hope of succor. They could choose surrender, death by combat during Allied mopping up operations, death by disease, death by suicide, or death by starvation.

Logistics and Base Development

The first operational airfield in the Biak area was that on Owi Island, which Fifth Air Force planes began using regularly on 21 June. By 12 July the 860th and 864th Engineer Aviation Battalions had extended the strip to 7,000 feet and had constructed 7,500 feet of taxiways. By 20 August the two engineer units and the 60th Naval Construction Battalion had completed a second 7,000-foot runway on Owi. In addition, there were then available on the tiny island some 20,000 feet of taxiways and 130 hardstandings.

P-40’s had begun operating from 5,000 completed feet of Mokmer Drome on Biak on 22 June. By 1 August the 863rd Engineer Aviation Battalion and the 46th Engineer Construction Battalion had extended the field to 7,000 feet and had completed 27,000 feet of taxiways and 122 hardstandings. On 1 August the 46th Engineers completed a 4,000-foot runway at Borokoe Drome, which was used principally by transport aircraft, and by the 20th had extended it to 5,500 feet. Some work was also undertaken on Sorido Drome, which by 12 August consisted of a 4,000-foot strip being used by transport planes. Terrain difficulties and a shortage of engineers made it impractical to extend Sorido, and the field was finally abandoned.43

While none of the Biak fields was ready in time to support the Central Pacific’s invasion of the Marianas in mid-June, they did prove extremely valuable in the support of subsequent operations to the west and north by forces of the Southwest Pacific Area and in the support of the Central Pacific’s landings in the Palau Islands in mid-September. The Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces also flew many missions from Biak over Japanese-held targets in the Netherlands East Indies and on Mindanao, in the southern Philippines.

As of 20 August, eight LST slots were being constructed along the south coast of Biak by the 1896th Engineers; two floating docks for Liberty Ships (one each at Owi and Biak) were completed; the Parai Jetty had been improved and extended; and two more fixed docks or jetties were under construction. On Owi Island over 12 miles of roads had been completed, while approximately 30 miles had been constructed on Biak. An additional 22 miles of roads were being improved on Biak. There was available over 1,130,000 square feet of storage space, including about 300,000 square feet under cover. Finally, one 400-bed hospital had been completed and a second was under construction. All these construction activities had been instituted under the direction of Headquarters, 1112th Engineer Combat Group, which was succeeded early in July by Headquarters, 1178th Engineer Construction Group.

Dock Area, Biak

Construction units at Biak encountered few major difficulties other than those occasioned by the enemy fire on Mokmer Drome. Wood was plentiful, although lumbering was made somewhat difficult because the best stands of timber were located at scattered points along steep ridges and precipitous hills. The prevailing coral of Biak and Owi was hard on equipment, but when processed it proved excellent material for airstrip and road paving. There were no drainage problems and ultimately enough fresh water was found to adequately supply the entire task force.44

Major supply problems of the HURRICANE Task Force were associated with unloading delays caused by enemy air raids, insufficient wheeled transportation during early phases of the operation, and an abnormally heavy expenditure of artillery ammunition. The shortage of transportation on shore was alleviated by the capture and use of about sixty enemy trucks, and additional wheeled transportation was later brought to Biak from rear bases.

Japanese air raids caused the Allied Naval Forces to permit only two LSTs to unload at a jetty at one time after Z Day. This order sometimes delayed unloading, but few LSTs left the island without being discharged in the time allotted. Until locally based fighter protection was available, no ships larger than LSTs were sent to Biak, and it was 22 June before the first big cargo

Base H and Hospital areas on Biak

ships arrived. Then, daily discharge rates began to climb from a few hundred tons daily to a peak of 4,073 tons on 12 August. A shortage of lightering craft was apparent for some time, but the arrival of the first floating dock on 22 July greatly relieved the strain on available lighterage.

The nature of the combat on Biak accounted for the abnormal expenditure of artillery ammunition—an expenditure which created a pressing problem in terms of shipping space. The shortage of shipping in the Southwest Pacific made movement of all supplies and equipment to Biak necessarily slow at times. A great deal of juggling of ship sailing schedules and hurried changes in loading plans at rear bases were necessary to keep the HURRICANE Task Force adequately supplied with artillery ammunition. Evidently there was some misunderstanding between Biak and the task force Rear Echelon at Hollandia concerning the requisitioning of ammunition, for, as the task force G-4 Section report put it:–