Chapter 9: Northern Leyte Valley: Part One

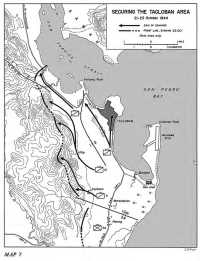

By the evening of 20 October the Tacloban airfield and Hill 522, overlooking the town of Palo at the northern entrance to Leyte Valley, were in the hands of the X Corps. The night of 20–21 October was free from enemy activity in the sector of the 1st Cavalry Division, and the exhausted troops were able to obtain an unquiet rest during their first night in the Philippines. Having secured the Tacloban airfield they were in position to march on Tacloban, the capital of Leyte, the following morning. Tacloban is situated on a peninsula at the head of San Pedro Bay. A string of low hills, stretching from Anibong Point along the base of the peninsula to the southeast, commands the approaches to the town.1 Throughout the night the 61st Field Artillery Battalion delivered harassing fires on the hills south of the town.2 (Map 7)

San Juanico Strait

Drive Toward Caibaan

General Krueger wished to push rapidly through Leyte Valley and secure its important roads and airfields before the Japanese could regroup and offer a firm line of resistance. In the north, securing San Juanico Strait would prevent any of the enemy from crossing over from Samar. Control of the road that led through the interior of northern Leyte Valley would give the possessor a firm hold on the northern part of the valley. With a successful two-pronged attack – elements of the 1st Cavalry Division driving north along San Juanico Strait and units of the 24th Infantry Division pushing along Highway 2 – the X Corps would arrive at Carigara Bay. At that point the corps would be in position to contest any Japanese amphibious movement through Carigara Bay, and at the same time elements of the corps could drive south through Ormoc Valley and secure the important port of Ormoc.

Preceded by a naval and air bombardment and a preparation by the 61st Field Artillery Battalion,3 the 1st Cavalry Division at 0800 on 21 October resumed the assault against the Japanese.4 The division was to capture Tacloban and then secure control over San Juanico Strait.5 The 7th Cavalry, 2nd Brigade, had been assigned the mission of seizing Tacloban,6 which was defended by elements of the Japanese 33rd Infantry Regiment.7

On the morning of 21 October the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry, joined the regiment’s

Map 7 Securing the Tacloban Area 21–23 October 1944

2nd Squadron in a drive on Tacloban. At 0800 the 7th Cavalry moved with squadrons abreast, the 1st Squadron on the right and the 2nd Squadron on the left, astride the highway leading to Tacloban. Although the squadrons found the terrain extremely swampy and movement difficult, by 1400 the 1st Squadron was on the outskirts of the town and the 2nd was halted at the foot of a hill overlooking Tacloban. The Japanese had dug into the hills overlooking the capital. The division artillery then shelled the hill and the high ground to the north.8 At 1500 the fire was lifted and the forward movement proceeded.

The men of the 1st Squadron entered Tacloban to conduct a house-to-house search for concealed Japanese. They received a tumultuous welcome from the Filipinos who lined the sides of the narrow streets, waving American flags and urging gifts of eggs and fruit upon the troopers.9 They were also welcomed by the governor of the province. The 2nd Squadron, on the other hand, was held up by an estimated 200 Japanese who were entrenched in pillboxes and foxholes and behind the dense vegetation that covered the hilly area. As heavy fire from the enemy pinned down the troops, Col. Walter H. Finnegan, the regiment’s commanding officer, sent the Antitank Platoon and elements of the Regimental Weapons Troop in support of the 2nd Squadron, where that unit faced the southern end of the hill mass.10

The Weapons Troop was ordered to lay aside its automatic weapons and assault the hill with rifles, but it was pinned down by intense fire from an enemy bunker to the immediate front. Pfc. Kenneth W. Grove, an ammunition carrier, volunteered to clear the Japanese from the position. He worked his way through the underbrush to the flank of the bunker, then charged in the open against its front and killed the gun crew.11 The advance then continued.

The movements of the Weapons Troop and the Antitank Platoon were successful, and by 1800 the southern half of the hill and the town of Tacloban were in American hands. Shortly after the seizure of the capital, General Mudge, the division commander, inspected the town from a medium tank. At one point, where the Japanese had turned over a truck to form a roadblock, the general personally received the surrender of forty Formosan laborers.12 The regimental command post was established in the building that had housed the Leyte Intermediate School for Girls.

The following day, after an intensive mortar, artillery, and air bombardment on a hill southwest of Tacloban, the 2nd Squadron of the 7th Cavalry moved out against the hill at 0820. Although the terrain was rugged, the position was overrun by 1100. The 1st Squadron spent the day mopping up the town in search of the enemy. At 1108 General Mudge released the 8th Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Bradley, to 2nd Brigade control.

By the end of 22 October the capital of Leyte and its hill defenses were securely in American hands. The 7th Cavalry was one day ahead of schedule, a fact partly explained by the unexpectedly light resistance of the Japanese and partly by the vigor of the 7th Cavalry’s advance.13

On the morning of 22 October the 8th Cavalry made a “victory” march through

A patrol from the 7th Cavalry moves along Avenida Rizal in Tacloban

Flag-waving Filipinos greet the American troops

Maj. Gen. Verne D. Mudge (in tank) confers with Brig. Gen. William C. Chase in Tacloban

liberated Tacloban and went into perimeter to the west of the 7th Cavalry on the hills overlooking the town. Troop C went to Anibong Point in order to guard the brigade flank from a suspected Japanese barge landing through San Juanico Strait.

Shortly after the command post was opened at 1830, the 8th Cavalry received orders for the 1st Squadron to depart at 0700 on the following day. It was to pass through the 7th Cavalry and secure the bridge crossing the Diit River so as to protect the 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry. The latter was directed to move northwest across the mountains, seize Santa Cruz, which was on Carigara Bay about sixteen miles northwest of Tacloban, and locate the remnants of the Japanese who had opposed the 7th Cavalry in its advance through the city.

The 1st Squadron, 8th Cavalry, passed through the 7th Cavalry at 0900 on the morning of 23 October. By nightfall the squadron had crossed and secured the Diit River bridge and routed small groups of the enemy. The 2nd Squadron experienced difficulty in securing Filipino carriers for the trip up the Diit River and across the unmapped and unknown mountains to Santa Cruz. It resolved the situation by driving a truck through the streets and seizing every able-bodied Filipino in sight. These “volunteers” were sufficient to get the squadron to its night bivouac on the Diit River. The “indignant carriers [then] dissolved into the

8-inch howitzers readied for action against an enemy strong point southwest of Tacloban

jungle.”14 The 2nd Squadron established its perimeter near the village of Diit.

Meanwhile, the 1st Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division had been ordered to move west on 21 October. This maneuver was designed to protect the southern flank of the 2nd Brigade and to prevent the Japanese from reinforcing their troops in Tacloban. The 1st Brigade moved out at 0800 toward Caibaan, the 12th Cavalry on the right and the 5th Cavalry on the left.15 Troop B of the 12th Cavalry advanced toward the barrio of Utap, and though it ran into enemy opposition it was able to secure the town after being reinforced by the regimental and brigade reconnaissance platoons. Swampy ground made the going very difficult. The troops captured a large Japanese supply dump which contained quantities of foodstuffs, vehicles, and equipment, and valuable documents.16

The 1st and 2nd Squadrons of the 5th Cavalry advanced abreast toward Caibaan and the high ground beyond the town. They encountered only sporadic rifle fire in Caibaan but at the foot of one of the hills they met determined opposition from about half a company of Japanese. After an

exchange of fire, the Japanese signified they wished to surrender by waving a white flag. The heavy machine guns were brought into position and the American soldiers signalled for the Japanese to disrobe in order to forestall their using concealed grenades or other weapons. The Japanese opened fire and wounded five men. The automatic weapons then returned the fire, killing thirteen of the enemy. The remaining Japanese withdrew over the hill, and contact was lost.

There was no enemy activity in the 5th Cavalry’s sector during the night of 21–22 October, and at 0645 the advance elements of the 1st Squadron began to move up the steep east slope of a hill west of Caibaan. The squadron continued its advance, and at 1200 engaged in a short skirmish between the hill and Caibaan, killing ten Japanese. The difficult terrain, rather than the Japanese, slowed the advance. Hampered by tall cogon grass, which cut off every breeze, the troops struggled up steep slopes and sharp ridges. Exposed to the hot sun and burdened with equipment and ammunition, they were soon exhausted. At 1447 the 5th Cavalry received orders to halt all forward movement until further notice. The 1st Squadron was in bad condition physically, since it had been steadily on the move for a day and a half and had consumed all its rations and water. At the end of the day, 22 October, the squadron was still at the base of the hill, but the rest of the regiment had reached Caibaan.17 On the following day elements of the 5th Cavalry were sent to Tacloban to act as a guard of honor for General MacArthur. The other units remained in position.18

Restoration of Civil Government

The guard of honor, consisting of 1st Lt. John Gregory and thirty enlisted men of the 5th Cavalry, arrived at Tacloban later on 23 October. President Osmeña of the Philippine Commonwealth was also present, having come ashore for the occasion.19 A simple but impressive ceremony was held in front of the municipal building of Tacloban, though the interior of the edifice was a shambles of broken furniture and scattered papers. A guard of honor of “dirty and tired but efficient-looking soldiers”20 was drawn up in front of the government building. General MacArthur broadcast an address announcing the establishment of the Philippine Civil Government with President Osmeña as its head. Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland then read the official proclamation. President Osmeña spoke appreciatively of American support and of the determination of the Filipinos to expel the enemy. “To the Color” was sounded on the bugle, and the national flags of the United States and the Philippines were simultaneously hoisted on the sides of the building. Colonel Kangleon of the guerrilla forces was then decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross.

Few Filipinos except representatives of the local government were present for the ceremony. Apparently the inhabitants had not heard of it, or did not know that they were permitted to attend. Information quickly spread, however, that the civil government had assumed control, and as General MacArthur and his party left town the civil population cheered them.21

General MacArthur announces the establishment of the Philippine Civil Government. Seen in the front row, left to right, are: Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney, Vice Adm. Thomas C. Kinkaid, Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, Lt. Gen. Richard K. Sutherland, General MacArthur and President Sergio Osmeña

Drive up the Strait

Though the 1st Cavalry Division had secured Tacloban and the region surrounding it, there remained the important task of seizing San Juanico Strait to prevent the Japanese from bringing in reinforcements from Samar. San Juanico Strait, connecting the Leyte Gulf with Samar Sea, forms a narrow passage between Leyte and Samar Islands. Highway 1 ends on its western shore, some fourteen miles north of Tacloban at Guintiguian, a small barrio two miles north of San Isidro. A ferry between Guintiguian and La Paz, just across the strait on Samar, links the road networks of the two islands. The 2nd Brigade’s mission was to seize Guintiguian on Leyte; La Paz on Samar (including the establishment of a bridgehead on the north bank of the Silaga River, three miles northeast of La Paz); and Babatngon on the north coast of Leyte. By shore-to-shore operations it was also to seize Basey on the island of Samar and the area north and west of it.22

General Hoffman had been warned that his 2nd Brigade would be assigned the mission of securing San Juanico Strait and possibly landing on Samar; he therefore directed an overwater reconnaissance of the

Proclamation to the People of the Philippine Islands

sector. Consequently, on 23 October the staff officers of the 8th Cavalry and of the 1st Squadron of the regiment boarded an LCI at the Tacloban dock. The landing craft made the trip through San Juanico Strait to the barrio of Babatngon on Janabatas Channel without incident. On the return trip, the officers observed some Japanese positions which overlooked the ferry crossing at the Guintiguian landing on Leyte. The party made a brief reconnaissance of the Guintiguian side of the ferry landing and of La Paz on the Samar side. There was no enemy contact.23

As a consequence General Hoffman, in issuing his orders for the next day, assigned the following missions: the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry, under Maj. Leonard E. Smith would embark at 0630 on 24 October, and move overwater to seize the town of Babatngon. This operation would seal off the western entrance into San Juanico Strait. Troop C, reinforced, of the 1st Squadron, 8th Cavalry, under Maj. F. Raymond King, was also to embark at 0630 from Tacloban and move north to seize the ferry crossing between Guintiguian and La Paz. At the same time the rest of the 1st Squadron, 8th Cavalry, under Lt. Col. Mayers Shore, would drive north along the highway and effect a juncture with C Troop at Guintiguian.24

The 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry, sailed for Babatngon at 1030 on 24 October. The trip was uneventful, and at 1330 the squadron arrived at Babatngon, sent out security patrols, and established a perimeter defense. On 25 October the Japanese launched an air attack, hitting an LCI in the Babatngon harbor. Eight men were killed and seventeen wounded, all of them Navy personnel.25 For the next few days the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry, made a series of overwater movements through Carigara Bay and exploited the lack of any strong Japanese resistance along the northeast coast of the Leyte Valley.26

Reinforced Troop C of the 1st Squadron, 8th Cavalry, was ready to sail by 0630 on 24 October but was delayed by a Japanese air attack on the shipping in Tacloban harbor and San Pedro Bay, made by about fifty medium bombers and Army fighters. Before they could reach the beachhead area, many of the Japanese planes were shot down by Navy combat air patrol fliers, who also beat off another wave of about thirty more planes. Two of the American planes crash-landed on the Tacloban airfield, while a third landed in the water.27 There was minor damage to American shipping.

One of the Japanese planes crashed less than 200 yards from elements of Troop C but the force got under way. The troopers, after running down and killing five Japanese in a canoe, arrived at La Paz, Samar, their destination, without further excitement and established a roadblock on the road leading to Basey.

The 1st Squadron of the 8th Cavalry, which was to travel overland by Highway 1 to make junction with Troop C at the ferry crossing, broke camp at 0700 on the morning of the 24th. The squadron was accompanied by a platoon of light tanks and weapons carriers with rations and ammunition. Since the passage was through enemy-held territory and over unfamiliar terrain,

Tacloban from the air

Close-up of the Tacloban dock area, showing San Juanico Strait and the island of Samar in the background

and since the strength of the Japanese forces was unknown, it was estimated that it would take the squadron a minimum of two days to cover the sixteen and a quarter miles between the two forces. The commanding officer of the squadron, however, by utilizing stream-crossing expedients to the utmost in snaking tanks and vehicles across the many intersecting streams and by driving the troops, was able to complete the difficult march to Guintiguian and go into perimeter with all his men except a rear guard at 2130 on the same day. At the end of 24 October, the 8th Cavalry, less the 2nd Squadron, was in a position from which it could defend its beachhead on Samar.28

At 2300 an estimated hundred Japanese from the 2nd Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, attacked the roadblock which had been established on the road leading to Basey. The Japanese opened up with machine gun fire and tossed several grenades against the position. The defenders repelled the attack with machine gun and mortar fire, but for the remainder of the night “confusion reigned supreme and the odds and ends were not rounded up until the next morning.”29 During the next three days the 8th Cavalry consolidated its position and extended its perimeter to include a bridgehead on the Silaga River.

By the end of 27 October the 1st Cavalry Division had seized Tacloban and gained control of San Juanico Strait. Because of supply difficulties the 2nd Brigade on 25 October had ordered the 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry, to discontinue its movement toward Santa Cruz, to remain in bivouac along the upper reaches of the Diit River and patrol that area. At this time the casualties of the 1st Cavalry Division amounted to 4 officers and 36 enlisted men killed, 14 officers and 185 enlisted men wounded, and 8 enlisted men missing in action.30 During the same period, the division reported it had killed 739 of the enemy and had taken prisoner 7 Japanese, 1 Formosan, and 1 Chinese.31

The opposition had been light – much lighter than had been expected. Elements of the division had therefore been sent south to reinforce the 24th Division, which had borne the brunt of the Japanese opposition in the X Corps sector in its drive through northern Leyte Valley toward Carigara Bay.

Leyte Valley Entrance

Defense at Pawing

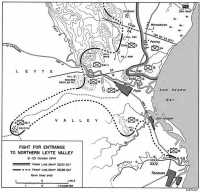

At the end of 20 October the 24th Division had established a firm beachhead near Palo, averaging a mile in depth, and had secured Hill 522 which overlooked Palo.32 (Map 8) The 24th Division was to seize Palo and drive astride the road that ran northwest through the Leyte Valley to Carigara. The 34th Infantry, in the vicinity of Pawing, had its 2nd Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. James F. Pearsall, Jr., 100 yards west of Highway 1, with the northern elements of the battalion in contact with the 5th Cavalry of the 1st Cavalry Division on the right. The 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry, was just short of the highway. The leading elements of the 19th Infantry were on Hill 522.33

Map 8 Fight for Entrance to Northern Leyte Valley 21–25 October 1944

At 0100 on 21 October three companies of Japanese,34 part of the 33rd Infantry Regiment,35 under cover of darkness and aided by heavy machine gun and mortar fire, struck from the south along Highway 1. The leading elements made a double envelopment of the American flanks while the main force came down the road and attacked the perimeter of the 2nd Platoon of Company G. By 0200 the enemy, still employing machine gun and mortar fire, had pushed to within a few yards of the American positions and had killed or wounded everyone but Pvt. Harold H. Moon, Jr., in the first two positions.

The Japanese then centered their fire upon Private Moon, who, although wounded by this fire, replied with his

sub-machine gun. An enemy officer attempted to throw grenades at Moon’s position and was killed. The Japanese then brought up a light machine gun to within twenty yards of his position. Moon called back the range correction to friendly mortars which knocked out the machine gun. For over four hours he held back the enemy. At dawn an entire platoon with fixed bayonets charged toward him. From a sitting position he fired into the Japanese, killed eighteen, and repulsed the attack. He then stood up and threw a grenade at a machine gun that had opened up on his right. He was hit and instantly killed.36 The Japanese then resumed their attack, but the remnants of Moon’s platoon fixed bayonets, charged, and succeeded in breaking through the enemy line.

In the meantime the enemy hit the perimeter of Company L. For several hours the Japanese felt out the company positions, and then, covered by three machine guns, they charged in platoon strength on the east side of the company’s perimeter. The company, supported by mortar fire, retaliated and assaulted the Japanese in front of the perimeter. Attempted movements around both the enemy flanks failed. A frontal assault, protected by fire from both flanks, was then successfully made by the company, and the Japanese force was routed. There were 105 enemy dead in the immediate area of the company.

By this time it was dawn, and Pearsall’s men began extensive countermeasures. Concentrated mortar fire was laid down, and, since Japanese artillery was shelling the American positions, artillery and air strikes were requested. At 0900 Battery A of the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion fired 150 rounds on the Japanese.37

At a point 1,500 yards south of Pawing naval flyers from the Seventh Fleet strafed the enemy and, in co-operation with the artillery fire, successfully broke the back of the offensive. The enemy scattered into the rice paddies. Members of the 2nd Battalion were then able to go down the road and mop up. More than 600 Japanese were killed during the engagement.38 Company G, which had borne the brunt of the attack, lost fourteen men killed and had twelve wounded.

The battalion had scarcely finished breakfast when at 1000 it was given the mission of seizing a hill mass immediately west of its position at Pawing. After artillery and naval gunfire had been placed upon the hill for fifteen minutes,39 E Company was to take the northern knoll of the hill mass and F Company to take the southern knoll. It was not until 1400, however, that the attack jumped off. Company E met no opposition, and within twenty-five minutes was able to occupy its objective.

Company F, commanded by Capt. Paul Austin, had more difficulty. Its objective was a steep hill, heavily covered with cogon grass ten to twelve feet high, which limited visibility to a few feet. A trail ran west from a small clump of trees to the top of the hill, and then south along the crest of the ridge where the grass was only six inches high. The company proceeded west in a column of platoons and at 1430 reached the foot of

Tank-supported infantrymen of the 34th Regiment attack a hill near Pawing

the hill. At the western edge of the group of trees, the 1st and 3rd Platoons turned left and advanced directly toward the highest point of the hill. The 2nd Platoon, with machine guns, continued up the path.

As the 2nd Squad of the 1st Platoon reached the crest and as the 1st Squad had nearly done so, an estimated 200 Japanese from the 33rd Infantry Regiment opened fire upon the troops with rifles and two machine guns that were emplaced upon a knoll overlooking the trail. Enemy riflemen also rolled grenades down upon the 1st Squad. These actions pinned down both of the squads.

Protected by the machine gun fire, other enemy riflemen worked north along the reverse slope of the ridge and began to throw grenades down upon the 2nd Platoon. The Japanese possessed a seemingly inexhaustible supply of grenades, which they rolled down upon the Americans with telling effect. Company F was unable to advance. By 1500 the 1st and 2nd Squads of the 1st Platoon were forced off the forward slope. The 2nd Platoon also had been unable to go ahead, and the company had suffered fourteen casualties. Captain Austin ordered his company to disengage for reorganization. Since the American mortars could not fire directly upon the Japanese for fear of hitting friendly troops, they were forced to fire over the enemy and gradually shorten the range as the American troops disengaged. Consequently the fire at first was not too effective. By 1600

the reorganization was complete, but Colonel Pearsall decided to delay the attack until artillery support could be obtained. Company F formed its night perimeter 500 yards from Pawing.

The following morning arrangements were made for an air strike by Navy flyers on the positions of the 33rd Infantry Regiment on the hill. It was not until afternoon, however, that the strike could be effected. At 1345 the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion marked with smoke the right and left limits for the air strike.40 At 1410 naval dive bombers bombed and strafed the hill for ten minutes with very good results, and the Japanese power to resist was broken.41 Captain Austin’s Company F, accompanied by Colonel Newman, the regimental commander, then moved out. Supported by artillery fire, Company F captured the entire ridge by 1515 without a single casualty. The Pawing area was now securely in American hands. Farther south the 19th Infantry was engaged in fulfilling its mission of capturing the town of Palo.

Capture of Palo

At the end of the first day’s fighting, C Company of the 19th Infantry had just secured the top of Hill 522 and Company B at dusk had been pinned down at the southern crest. The following morning artillery fire effectively knocked out some enemy pillboxes on the north crest. Both companies then simultaneously launched an attack down the far slope of the hill. In the sharp fight that followed fifty Japanese from the 33rd Infantry Regiment were killed and the hill was secured.42 It was not until late in the day, however, that supplies could be brought to the troops and the wounded be evacuated. The 1st Battalion spent the next few days mopping up the area and sealing off the tunnels with grenades.

On the beach the 3rd Battalion, 19th Infantry, on the morning of 21 October waited for naval gunfire to knock out positions that blocked the beach road to Palo. These defenses consisted of mutually supporting well-constructed pillboxes reinforced with logs and earth, with intercommunicating trenches and foxholes. They were designed to be used in resisting attacks from the beach and from the north. After an all-night mortar concentration, naval gunfire was directed against the positions, and at 1400 the 3rd Battalion attacked. When within 200 yards of a road bend, Company I and elements of the Antitank Company, leading the main assault, met strong resistance, which forced the company to dig in. The other companies occupied the same positions they had held the previous day.43 During the night Company C of the 85th Chemical Battalion, expending 500 rounds of ammunition, laid intermittent fire from the 4.2-inch mortars on the Japanese positions.44

At 0900 on 22 October the 3rd Battalion, with Company I in the lead, attacked with the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, which had been released from division reserve, on its left flank. This co-ordinated advance pushed past the defensive positions of the 33rd Infantry Regiment, many of which had been abandoned. The positions of the 3rd Battalion, 19th Infantry, were taken over by the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry. The latter battalion patrolled the road and eliminated

Palo, with the Palo River and the slopes of Hill 522 in the background (above), and the junction of Highways 1 and 2 (below)

scattered Japanese pockets of resistance south to the Palo River.

The 2nd Battalion, 19th Infantry, was to secure Palo, which is situated about one mile inland on the south side of the Palo River. The town is an important road junction, the meeting point of the Leyte Valley and east coast road systems. The coastal road, Highway 1, which goes through Palo, crosses a steel bridge over the Palo River on the edge of the town. Highway 2, a one-lane all-weather road for most of its length, extends west to Barugo and Carigara.45 Just outside Palo are two hills, one on each side of the highway, which guard the entrance into the interior. The Americans termed them Hills B and C. Elements of the 33rd Infantry Regiment were guarding Palo.46

Early in the morning of 21 October, the 2nd Battalion, 19th Infantry, moved west through enemy machine gun and rifle fire and bypassed the enemy defensive position that had held it up the previous day. At 1155 the battalion reached the junction of the beach road and Highway 1. During the movement two men were killed and two wounded. At the road junction, the battalion dispersed with machine gun fire a column of about thirty-five Japanese moving south on Highway 1. Artillery fire was then laid on a grove of trees, west of the road, to which the enemy had fled. As the battalion proceeded south along the highway between the road junction and the bridge, it came under artillery fire from an undetermined source. The tempo of the march into Palo was accelerated--”the troops wanted to move as rapidly as possible from that vicinity. They double timed across the bridge.”47 At 1500 they entered Palo without further opposition.48

The residents of the town were crowded into the church. As the Americans entered, the church bell rang and the Filipinos came out and greeted the troops. After the first exuberant welcome had subsided, the soldiers ordered the civilians back into the church until they could secure the town. In the house-to-house search, the troops found some booby traps made from coconuts49 and encountered Japanese entrenched under and between houses in the western sector of the town. Although the battalion had expected to outpost the entire town, the menace of the Japanese appeared so threatening that a night perimeter was established around the town square.

Defense of Palo

During the early part of the night there was continuous rifle fire from individual Japanese. The 13th Field Artillery Battalion had arrived and began to fire on the roads leading into the town, expending some 300 rounds of ammunition. At midnight some Japanese ammunition stored in a house exploded, and the ensuing fire lasted for three hours. At 0400 on 22 October elements of the 33rd Infantry Regiment counterattacked along Highway 250 but were repulsed by fire from the outposts. The enemy then struck at the juncture of the left flank of Company F and the right flank of Company G. The 81-mm. mortars of the 2nd Battalion fired on this point, expending all their ammunition. In the meantime Battery B of the 13th Field Artillery Battalion

and elements of the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion moved up to within a hundred yards of the front outposts and fired. The enemy stubbornly continued to fight, throwing “everything he had into the attack.”51 At the same time nearly a platoon of the enemy came out at the curve of the beach road and started toward the bridge on Highway 1 at Palo, but these troops were dispersed by light machine gun fire. Artillery fire forced the Japanese to withdraw, and they were thrown back on all fronts.52 Though the battalion had lost 16 men killed and 44 wounded, it had killed 91 Japanese. After the engagement, the battalion requested additional ammunition, supplies, and equipment, and transportation for the wounded.53 The requests were complied with, though not without danger since the Japanese had mined the road.

At 1330 the regimental headquarters of the 19th Infantry moved into Palo. The regiment’s 3rd Battalion relieved the 2nd Battalion at the same time, thus enabling the latter to attack Hill B at 1425.54 The 3rd Battalion spent the rest of the day and the following day mopping up in Palo and sending probing patrols southward in order to make contact with the XXIV Corps.55 A patrol in Palo killed seven Japanese dressed in civilian clothing, one of whom, a lieutenant, had his insignia pinned inside his clothes.56

On the night of 23 October Col. Tatsunosuke Suzuki, the commanding officer of the 33rd Infantry Regiment, led a raiding detachment, armed with rifles, sabres, grenades, and mines, into Palo from the southwest.57 Using Filipino civilians in front of them, the men of the detachment tricked the guards at the outpost into believing that they were guerrillas. The Japanese were thus able to capture two machine guns and a 37-mm. gun. They penetrated to the town square and charged, throwing explosives into houses, trucks, and a tank, and broke into an evacuation hospital where they killed some wounded. They then moved toward the bridge and mounted the captured machine guns on it,58 firing until their ammunition was exhausted and then abandoning the guns. The American guards on the other side of the bridge, however, were able to fire upon the bridge and its approaches so effectively that they killed fifty Japanese, according to a count made the next morning. The raid was completely broken up, and sixty Japanese, including Colonel Suzuki, were killed. The American casualties were fourteen killed and twenty wounded.

The 3rd Battalion, 19th Infantry, had sent Company K to reconnoiter to the south and if possible make contact with the XXIV Corps. On the morning of the 24th the company entered San Joaquin to the south of Palo. By 1600 the town had been secured and the company was prepared to defend it. Engineers began to repair the damaged bridge so that armored units could proceed southward along Highway 1. On the morning of 25 October Company K advanced south from San Joaquin and by 1200 had secured positions on the north bank of the Binahaan River, from which patrols were sent into Tanauan. At 1430 the patrols met a motorized unit of the 96th Division, establishing contact for the first time between the X and XXIV Corps. The rest of the

battalion moved out of Palo the same morning and was able to advance rapidly with little opposition and set up a perimeter at Castilla, 8,000 yards southwest of Palo.

Thus the northern and southern approaches to Palo and the beachhead area east of the town had now been secured. But on the western edge of Palo were the two hills athwart Highway 2 and blocking passage into Leyte Valley. Hill B on the southern side of the highway and Hill C on the northern side would have to be secured before the Americans could advance. Preliminary reconnaissance had revealed that these hills were strongly held, and since the 24th Division, contrary to expectations, had encountered considerably stronger opposition than the 1st Cavalry Division, General Sibert decided to detach the 1st Brigade from the 1st Cavalry Division and place it under X Corps control. The 2nd Squadron of the 5th Cavalry remained in position on the high ground west of Tacloban, while the regiment’s 1st Squadron moved into position in Pawing, to relieve the 2nd Battalion, 34th Infantry. The 12th Cavalry assembled in the vicinity of Marasbaras in X Corps reserve.59

Capture of Hill C

At 0800 on 23 October the 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, commanded by Maj. Edwin N. Edris, and the 1st Platoon, 603rd Tank Company, assembled 500 yards north of Hill 522 preparatory to launching an attack on Hill C.60 It was reported that 300 Japanese were in a strong defensive position between Hills C and 331, the latter located west of Pawing. Consequently, an air strike was called for and delivered on the area, after which the battalion started for Hill C. The first obstacle encountered was a small ridge known as Hill Nan, and just beyond this ridge was another hill mass known as Hill Mike. Company B advanced up Hill Nan in a skirmish line. When the company neared the crest of the ridge, a machine gun 200 yards to its front opened up, and at the same time the Japanese from dug-in positions on the reverse slope began to throw grenades over the crest. The company was halted. Three times during the afternoon it reached the crest, only to be driven back by enemy fire. Several counterattacks were repulsed, but the machine gun was not silenced.

At 1800 the company received orders to disengage so that artillery fire might be laid upon the enemy positions. The Japanese immediately counterattacked. An American lieutenant and a sergeant of the company rushed to the crest with grenades which they threw upon the advancing Japanese. This action enabled the company to disengage and return to the assembly area with only a few casualties.

During the night artillery and 4.2-inch mortar fires were placed on the ridge. As a result, on the following day, 24 October, the 1st Battalion secured it without meeting any resistance. With this ridge in American hands, the 3rd Battalion was able to pass through the 1st Battalion and secure without opposition Hill Mike, the last remaining obstacle before Hill C. During the night artillery pounded Hill C.

On the morning of 25 October the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry, moved out to attack Hill C, with Companies I and K abreast.61 Although the troops found the hill difficult to climb, elements of Company

K reached its crest without opposition. The enemy started his usual tactics of throwing grenades over the crest of the hill at Company I as it neared the top. Since the company had suffered many casualties, a platoon from Company K was sent to reinforce Company I. Finally, at 1700, the company took the crest of the hill and dug in for the night.

The 2nd Battalion, 34th Infantry, which had been relieved by the 1st Squadron, 5th Cavalry, moved out of Pawing at 0700 on 24 October. At 1030 it received orders to seize a small hill southeast of Hill C. With Company E in the lead, the battalion proceeded in single file up the hill, which was covered with cogon grass. As it had hitherto been the practice of the Japanese to withhold their main fire until the Americans neared the top of a hill, the troops expected little opposition before reaching the crest. But while the company was still a considerable distance from the top, elements of the 33rd Infantry Regiment opened up with rifles, machine guns, and grenades. This fire pinned the company down, and the men immediately sought concealment in the cogon grass. Light machine guns were brought up, but, because of the steepness of the slope, they were ineffective. Artillery and mortars fired for two hours against the entrenched Japanese positions. At 1610 Company E renewed the attack and this time secured the hill with little opposition. The 34th Infantry now occupied the hills on the north side of Highway 2.

Seizure of Hill B

On 22 October the 3rd Battalion of the 19th Infantry had relieved the 2nd Battalion of the regiment at Palo, and the regimental commander ordered the 2nd Battalion to proceed against Hill B.62 Earlier, the 2nd Battalion had sent patrols out preparatory to attacking the hill. The 13th Field Artillery Battalion laid maximum supporting fires on Hill B as naval bombers strafed it.63 The 2nd Battalion moved out to the attack at 1425, and the concentrated artillery fire enabled it to secure without resistance a ridge east of Hill B and then push on down the road toward the hill. But as Company E, the lead company, reached the foot of Hill B, it was met by a large group from the 33rd Infantry Regiment coming east down the road and around the hill. The Japanese had left riflemen dug in on the steep banks of the road and had posted others in the trees along the road. Some of these riflemen allowed part of the American troops to pass and then opened fire. A sharp fire fight broke out in which Company E killed an estimated hundred of the enemy before being forced to withdraw to the ridge, where the 2nd Battalion dug in for the night. During the night the 13th Field Artillery fired on Hill B. At 0730 the following day the 2nd Battalion sent out two patrols to scout the enemy positions. The patrol on the right flank was stopped by machine gun fire at a point 200 yards west of the ridge and was forced to return. Mortar fire was placed on the enemy machine guns, after which the 2nd Battalion advanced, reaching what was believed to be the crest of Hill B at 1530.64

As the forward progress was more difficult than had been expected, the 2nd Squadron of the 12th Cavalry was sent to relieve the 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry, which had been engaged in mopping up Hill 522.65 This

relieved battalion was given the mission of attacking Hill 85, to the south of Palo, where the 24th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop had located a strong enemy position. During the night the artillery placed concentrated fire upon Hill 85.

At 0800 on 24 October the men of the 2nd Battalion moved out, attempting to complete the capture of Hill B.66 They were held up by well-emplaced pillboxes and foxholes on the highest crest of the ridge, having discovered that the crest they had first occupied was not the true crest. Since the 33rd Infantry Regiment seemed to be well emplaced on the hill, Lt. Col. Robert B. Spragins had his battalion move to the right. It took up a position overlooking a narrow asphalt road that ran from Highway 2 to a Japanese supply dump to the south. Colonel Spragins decided to attack Hill B from this position on the following morning.

The 13th Field Artillery Battalion again pounded the enemy positions on the hill during the night. On the morning of 25 October the 2nd Battalion attacked with Companies G and E abreast. The troops moved down the slope, across the road, and up the hill, with no opposition. On reaching the crest, they were met by heavy fire that came from well-constructed emplacements. Some of these positions were six feet deep and five feet wide. Very heavy fighting broke out in which the companies were barely able to hold their positions. The 11th and 52nd Field Artillery Battalions fired in front of Hill B,67 and the enemy fire was silenced. Company E was forced back, but Company G held on.

Although the hill was in American hands, the hold was very precarious. Colonel Spragins therefore moved the rest of the battalion up to Company G and ordered the latter to move out to a far ridge in order to secure the hill firmly. This move was accomplished at twilight. The rest of the battalion moved out to join Company G.

Starting in the dark, the battalion lost its way. At midnight the troops came to the true crest of the ridge where the enemy had an observation post surrounded by prepared positions. All were empty. The Japanese had formed the habit of going to the villages for the night and returning in the morning to man their posts. The night movement of the battalion “literally caught them napping away from their defenses.”68 The battalion had not reached Company G, but it set up a defensive perimeter for the night. The hills guarding Leyte Valley were now in American hands.

During the day the 1st Battalion, 19th Infantry, secured complete control of Hill 85 without opposition. The battalion found an abandoned position, mortar ammunition, and six dead Japanese.

By the end of 25 October the X Corps had made substantial progress toward securing northern Leyte Valley. After capturing Tacloban, the 1st Cavalry Division had pushed north and secured control over San Juanico Strait. The 24th Division had secured Palo and the hill fortresses that blocked the entrance into northern Leyte Valley. The corps was now in a position to launch a drive into the interior of the valley.