Chapter 16: The Fall of Ormoc

It was a time for decision. By the first of December the two adversaries had taken the measure of each other, but neither felt satisfied with the progress of the campaign. The tide of battle was slowly turning against the Japanese. They had wagered major stakes that the battle of Leyte should be the decisive one of the Philippines. Someway, somehow, the Japanese felt, they must regain the initiative or Leyte, for which so much had been sacrificed, would be lost to them. The days had dwindled to a precious few.

Imperial General Headquarters was loath to write off the Leyte Campaign. A daring plan was conceived whereby the ground and air forces, working in close co-ordination, would attempt to wrest the initiative from General Krueger’s forces. Before the main effort, suicide aircraft carrying demolition teams were to crash-land on the Dulag and Tacloban airstrips and render them unfit for use. Thereafter, the 2nd Raiding Group of the 4th Air Army would transport two paratroop companies to the Burauen airfields. The paratroops in conjunction with elements of the 35th Army, including the 26th Division, would then seize the Burauen airfields. The time was to be the evening of 5 December. With the loss of the airfields, the U.S. Sixth Army, it was hoped, would be in a perilous situation.1

General Krueger was also making plans. By the middle of November strong elements of the Sixth Army were trying to force their way into the Ormoc Valley and others were on the eastern shore of Ormoc Bay. The plan of General Krueger was simple. He wanted to secure control of the valley and the port of Ormoc and thus force the Japanese into the mountains near the western coast, from which they could escape only by sea.

At this time the XXIV Corps was with difficulty driving west and north from the center of the island. The 96th Division was engaged in mopping up in the mountains overlooking Leyte Valley. Units of the 7th Division, far to the south, were moving westward toward Baybay on the shore of the Camotes Sea. The 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th and 32nd Infantry Divisions of the X Corps were making slow progress in driving down the Ormoc corridor from the Limon-Pinamopoan-Carigara area.

Several courses of action were now open to General Krueger. He could concentrate on the drive of the 32nd Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division south down the Ormoc corridor, or on the advance of the 7th Division north along the coast of Ormoc Bay from Baybay to Ormoc. A third course also presented itself. An amphibious overwater movement might be attempted by landing troops just below Ormoc in the midst of the enemy force, thus dividing the

Japanese strength. After landing, the troops could push north, seize Ormoc, and then drive up the Ormoc corridor and effect a juncture with elements of the X Corps. This move, though highly hazardous, would considerably shorten the Leyte Campaign if successfully carried out.

In mid-November, therefore, General Krueger proposed that an amphibious movement and a landing at a point just below Ormoc be made. At that time, however, the naval forces did not have the necessary assault and resupply shipping on hand to mount and maintain such an operation and to execute as well the Mindoro operation scheduled for 5 December. Since there was insufficient air support, the local naval commander felt that a convoy entering Ormoc Bay might be in jeopardy and that Japanese suicide bombing tactics could cause heavy losses. Unable to secure the necessary assault shipping, General Krueger temporarily set aside his plan.2

Plan for Amphibious Movement

On 30 November General MacArthur postponed for ten days the Mindoro operation.3 The postponement would make available the amphibious shipping and naval support that were necessary for a landing in the Ormoc area. From a naval point of view, however, the operation was very precarious, since the Japanese were still making aerial attacks that could seriously damage the shipping needed for the forthcoming Mindoro and Luzon operations. After careful consideration of the risks involved, Admiral Kinkaid decided to make available to General Krueger the shipping required for an amphibious movement to a point below Ormoc.4

After issuing a warning order on 1 December, General Krueger on 4 December ordered the two corps to make their “main effort,” starting 5 December, toward the defeat of the enemy forces in the Ormoc area. The X Corps was to advance “vigorously south astride Highway 2 so as to support the effort made by the ... XXIV Corps.” The commanding general of the XXIV Corps was to arrange with the commander of the naval task group for the shipping and naval gunfire support necessary to transport and land a division just below Ormoc. General Hodge, also, was to arrange with the commanding general of the Fifth Air Force for close air support for the landing and subsequent operations ashore.5 The 77th Division was selected to make the amphibious movement to the Ormoc area.

In planning for the Leyte operation the Sixth Army had designated Maj. Gen. Andrew D. Bruce’s 77th Infantry Division, then on Guam, as the second of its two reserve divisions. As a result of the successes in the first days of the campaign, however, General MacArthur thought it would not be necessary to use the division on Leyte. On 29 October, without General Krueger’s concurrence, General MacArthur transferred control of the division from General Krueger to Admiral Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Area.6 Shortly afterward the Japanese began their reinforcements of Leyte and a captured Japanese

field order revealed that an all-out offensive would be launched against the Americans in the middle of November. These developments led General MacArthur to request Admiral Nimitz to divert the 77th Division, which was on its way to New Caledonia, to the Tacloban area on Leyte.7 Admiral Nimitz acquiesced and told General MacArthur that the division was being sent to Manus. After its arrival there, operational control over it would pass to General MacArthur.8

Upon arrival of the 77th Division at Seeadler Harbor on Manus at 1330, 15 November, General MacArthur ordered it to go to Leyte and come under the control of General Krueger.9 After the ships’ stores had been replenished, the convoy sailed out of the anchorage at 1700, 17 November, and made the voyage to Leyte without incident.10 The units commenced landing on the eastern shores of Leyte in the vicinity of Tarragona and Dulag about 1800, 23 November, and came under the control of General Krueger who assigned the division to General Hodge. From 23 to 25 November it was engaged in unloading the transports and establishing bivouac areas.

On 19 November, while it was still at sea, General Krueger had ordered the 77th Division to furnish immediately after landing a ship-unloading detail of about 1,200 men for the projected operation at Mindoro.11 At 1600 on 27 November the detail, a battalion of the 306th Infantry, boarded LCIs at Tarragona Beach and departed for the staging area for the Mindoro operation.

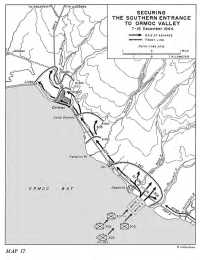

In conformity with General Krueger’s plans, General Hodge ordered the 77th Division to make preparations for the amphibious operation below Ormoc. (Map 17) It was to be assisted by the 7th Division, which was to attack and capture the high ground south of the Panilahan River. General Bruce, once ashore, was to direct and co-ordinate the attack of the 7th Division with that of the 77th Division.12 General Krueger informed General Hodge that he did not approve of this arrangement and added that such co-ordination as was necessary should be exercised by Hodge as corps commander.13

At a point about three and a half miles southeast of Ormoc was the barrio of Deposito where the 77th Division was to land. Along the eastern shore of Ormoc Bay, south from Ormoc, there were many areas which offered suitable landing beaches. These were crossed by numerous rivers and streams which discharged into Ormoc Bay. None of these would be a handicap, since all could be forded except during the monsoon season. The beach area selected, though narrow, was suitable for landing, having a surface of hard sand and gravel that could be used as a road by vehicles.

Map 17: Securing the Southern Entrance to Ormoc Valley 7–15 December 1944

The terrain was level for about a mile and a half inland from the beach, and then rose gradually to a height of twenty to thirty feet. Half a mile farther inland, the mountain slopes began. Highway 2, which was ten feet wide and composed of sand and gravel, ran along the entire length of the east coast of Ormoc Bay. Several roads ran from Highway 2 to the beach: one was about a hundred yards south of the Baod River and skirted the rice paddies in the middle of the landing beach area; another, just south of the rice paddies, extended inland about two miles from the beach.14

Naval Plans

When the naval forces were informed that the overwater movement to Ormoc would take place and that the Mindoro operation was postponed, the shipping reserved for the Mindoro operation was turned over to the Ormoc force. Rear Adm. Arthur D. Struble was given command of Task Group 78.3, which was to transport and land the 77th Division, together with its supplies and equipment, in the Ormoc Bay area and support the landing by naval gunfire.15

Admiral Struble divided his task group into six units, in addition to the destroyer which was his flagship. These consisted of: a Fast Transport Unit of eight transports; a Light Transport Unit of twenty-seven landing craft and twelve LSMs (medium landing ships); a Heavy Transport Unit of four LSTs (tank landing ships); an Escort Unit of twelve destroyers; a Mine-Sweeping Unit of nine mine sweepers and a transport; and a Control and Inshore Support Unit made up of four LCI(R)’s (infantry rocket landing craft), two submarine chasers, and one tug. The landing was to be made between the Baod and Bagonbon Rivers but clear of the Bagonbon River delta. The northern half of the beach was called WHITE I and the southern half WHITE II. Six destroyers would bombard the landing beaches.

The line of departure was fixed at 2,000 yards from the beach, but if the shore fire became heavy the line of departure would be moved back 1,000 yards. There would be five assault waves with two LCI(R)’s flanking the first wave to the beach. Each craft would fire so as to cover the sector of the beach in its area to a depth of 600 yards. After completion of the bombardment the LCI(R)’s would reload and remain on the flanks to engage targets of opportunity.

Air Support Plans16

The Fifth Air Force would provide both day and night air cover for the journey of the assault convoy to the target, for the landings, and for the return convoy. It was estimated that on 5 December, for the journey to the target, seventeen night fighter sorties and seventy-two day fighter sorties would be required. Protection would also be furnished by the bombers, and forty-six aircraft would be available on call for strikes against enemy installations and targets of opportunity, as well as for special missions.

On the day of the landings, the tempo would be accelerated. There would be nineteen

night fighter sorties and ninety-six day fighter sorties; ten flights of forty bombers to cover the beachhead; six flights of twenty-four bombers to cover the return of the assault convoy; and eleven night fighters to cover the LST and main assault convoys, the beachhead, and the return convoy. There would also be available sixteen bombers for interception or additional cover for the beachhead and convoy; twenty-four P-47’s for interception, ground support, and attacks against enemy shipping or targets of opportunity; sixteen P-40’s for ground strikes; and thirty-four F4U’s for cover or interception.

The 77th Division continued to assemble its troops on Tarragona Beach, on the east coast of Leyte, and during the night of 5 December the loading of supplies and equipment on the landing ships began. The loading was slowed by frequent air alerts. The division had previously been told that the convoy would be unable to stay in the landing area more than two hours and consequently there was no attempt to bulk load supplies, since they would take too long to unload. All supplies and equipment to support the initial assault had to be mobile-loaded, that is, loaded on the vehicles taken with the division so that the supplies could be brought ashore in the vehicles upon debarkation. There were only 289 vehicles in the initial convoy, including tanks, M8’s, and M10’s that could not carry supplies. The LVTs (tracked landing vehicles) were filled with supplies rather than troops in order that they could be discharged from the landing ships into the water and go ashore fully loaded. Furthermore, since the supplies were mobile they could be moved either by water or inland by motor.17 The 77th Division gave the highest priority to ammunition, water, and rations.

About 0700 on 6 December the assault shipping rendezvoused off Tarragona and Rizal Beaches, and one hour later the assault troops began to board the vessels. The loading was completed at 1200 and the convoy assembled offshore from Dulag to await the arrival of the twelve escorting destroyers.

The Movement Overwater

The Convoy Sails

Two mine sweepers swept the Canigao Channel between Leyte and Bohol on 27 November and again on 4 and 6 December, but they encountered no mines of any sort.18 At 1200 on 6 December the convoy’s escorting destroyers departed from San Pedro Bay and moved to the point of rendezvous offshore, near the Tarragona-Rizal area. The principal convoy was formed and got under way at 1330, having been preceded by four slower-moving LSTs escorted by two destroyers. The commander of the destroyer unit gave additional protection to the transports with four destroyers until 2300, when the destroyers departed for a prelanding raid on Ormoc Bay. They were also to intercept any Japanese surface vessels that might be attempting to bring reinforcements into Ormoc harbor.

The journey through Leyte Gulf, Surigao Strait, and the Camotes Sea was uneventful. Several unidentified planes flew over the convoy but did not launch an attack. The only alert during the voyage was about twilight on the 6th of December, when an unidentified group of eighteen bombers flew over the formation in the direction of

Troops of the 77th Division board LCIs at Tarragona

Tacloban. The convoy encountered numerous small native craft en route and checked several of these but found no Japanese.19

Throughout the night the vessels steamed toward the target. Silently they took their stations in Ormoc Bay, off the coast of Deposito, before dawn. At 0634 on 7 December an enemy shore battery opened fire, which was answered at 0640 as the destroyers commenced firing upon their assigned targets. Behind Ipil, in the vicinity of the northern fire support group, a number of enemy 3-inch gun positions were observed. The destroyers took the positions under fire and quickly silenced them. At 0655 a large number of Japanese were observed in the town of Albuera and these also were taken under fire. The destroyers covered the landing beaches until ordered to lift fire just as the first wave of the landing party was approaching the beach.20

As the American convoy steamed into position, it received word that an enemy convoy was on the way to Ormoc with reinforcements. Aircraft of the V Fighter Command flew to intercept the Japanese vessels, which comprised six transports and seven escort vessels. During the morning occurred one of the most intense aerial battles of the Leyte Campaign. Fifty-six P-47’s of the 341st and 347th Fighter Squadrons dropped ninety-four 1,000-pound and six 500-pound bombs on the enemy shipping and strafed the vessels. The Army and Marine land-based aircraft

Convoy carrying 77th Division approaches Deposito

Bombardment of enemy positions at Ipil, with stack of sugar mill visible. Village is near center of picture

destroyed two cargo vessels and two passenger transports.21 Nearly all the available American aircraft were engaged in the attack. General MacArthur in his daily communique estimated that the entire convoy was wiped out and that 4,000 enemy troops lost their lives.22

“Land the Landing Party”

The landing of the first wave, scheduled for 0630, was delayed until 0707 to take advantage of better light for the naval bombardment. There were to be five waves for each regiment.23 At 0701 the first wave of small landing craft left the line of departure and raced for the shore. The first wave was landed at 0707, co-ordinating its spacing and timing with that of the LCI(R)’s supporting the landing. There was no opposition, and the troops moved inland.

The dispatch and landing of the fourth wave of LCI(R)’s was delayed because the third wave had been unable to disembark the troops and retract according to schedule. The fifth wave of LSMs was delayed for the same reason. Since the tide was rapidly falling and the sand bar was exposed, a tug was used in several instances to pull the craft off. At 1100 the commander of the task group pulled out, leaving behind one LCI and four LSMs stranded on the beach. The tug left at the same time, and Admiral Struble ordered the grounded craft to retract at high tide and proceed back to San Pedro Bay under cover of darkness.24

With the departure of the landing waves for the shore, the destroyers turned their fire upon targets adjacent to the landing beaches. The Laffey at 0830 opened fire against some enemy troops approaching the barrio of Ipil from the north and turned them back. At 0930 the Conyngham fired upon a possible concentration south of Ipil and at 1000 this destroyer’s shore fire control party requested additional support against enemy troops that were moving into Ipil.25

At 0820 the Japanese launched a strong aerial offensive against the American vessels in Ormoc Bay. The enemy air attacks continued for nearly nine and a half hours. The Fifth Air Force, beginning at 0700, gave air cover throughout the day and “did an excellent job.”26 Upon a number of occasions, however, the enemy airplanes slipped through the antiaircraft fire and the air protection and hit the shipping. Japanese suicide aircraft struck and badly damaged five vessels. At 0945 the destroyer Mahan and the high-speed transport Ward received such damaging blows that they later had to be sunk by gunfire.27 The Japanese made

sixteen different raids on the shipping, during which an estimated forty-five to fifty enemy aircraft attacked the formation. Thirty-six of these were believed to have been shot down.28

The landing waves arrived ashore without incident and without casualties. Within thirty-five minutes the advance echelon of division headquarters, including the assistant division commander and the general staff sections, were ashore.29 Approximately 2,000 men were placed on a 1,000-yard beach every five minutes. Mobile-loading of supplies had made this speed possible. “Logistically it was a difficult operation to push that mass of troops and equipment on a beach in so short a time and had there been any considerable unexpected enemy mortar or artillery fire at any time during the period, great casualties might have resulted.”30 At 0930 General Bruce assumed command ashore.

Japanese Plans

Until the middle of November, the commander of the Japanese 35th Army had failed to put any beach obstacles along the shores of Ormoc Bay,31 since he believed that there was little likelihood of an American thrust up the bay. General Suzuki thought that the Americans would be deterred by the presence of a Japanese naval base on Cebu in front of Bohol Strait. As American naval activity increased along the coast in the last part of November, however, the Japanese finally conceded that there was “a great possibility” of an American landing at Ormoc Bay. By the middle of the month the Ormoc Defense Headquarters was organized under the command of Colonel Mitsui, the commanding officer of the Shipping Unit. The main force of the Defense Headquarters was the Shipping Unit, but the Antitank and Antiaircraft Gun Units, the Automatic Gun Company, and other units were added. In addition, all units then in Ormoc were temporarily placed under Colonel Mitsui. The enemy plan of defense was simple. At the town of Ormoc the Japanese, from their main defensive positions, were to stop the advance and then, gathering as much strength as possible, they were to counterattack.

The Japanese defenses, however, were not completed at the time of the American landings. Only individual trenches had been dug along the coast, and the field positions in the northern part of Ipil were elementary. Upon being alerted that the Americans had landed, the Shipping Unit of Colonel Mitsui took up its main defensive positions in the Ipil area. At the same time, troops of the Nonaka Battalion of the 30th Division, consisting of an infantry company and a machine gun company, were placed under the command of Colonel Mitsui. The major part of the 30th Division remained on Mindanao. The American strength was estimated to be one regiment.

Drive Toward Ormoc

Ipil

The assault elements of the 77th Division advanced inland immediately after landing. The 1st Battalion of Col. Vincent J. Tanzola’s 305th Infantry, with two companies

abreast, was to seize the crossings over the Bagonbon River in the vicinity of Highway 2.32 The 307th Infantry was to move rapidly inland and establish an initial beachhead line about 1,300 yards east near a bridge over the Baod River. The 305th Infantry landed in a column of battalions with the 1st, 3rd, and 2nd Battalions going ashore in that order. The 1st and 3rd Battalions moved rapidly inland to the objective while the 2nd Battalion remained in regimental reserve. The 307th Infantry also reached the bridge without difficulty. In the town of Deposito, enemy foxholes had been dug in the tall grass and apparently were to be used only as a protection against Allied air attacks, since they had no field of fire. Immediately upon landing, a reconnaissance patrol went to locate a trail leading from the beach to Highway 2. About 300 yards north of the Bagonbon River, the patrol found a small access road which was put to immediate use.33 The initial beachhead line was achieved within forty-five minutes after landing. Most of the Japanese 26th Division which had been in the area were either moving over the mountains to participate in a battle for the Burauen airfields or were engaging the 7th Division south of Deposito. Little besides service troops remained to oppose the 77th Division.

General Bruce originally had planned to hold the beachhead line, establish a defensive position, and await the arrival of additional supplies and reinforcements on the following day. But because of the lack of organized resistance, the speed with which the troops moved inland, and his desire to fully exploit the situation before the Japanese could counterattack, he very early decided to continue the attack northward astride the highway and extend the division’s beachhead to Ipil.34

The 307th Infantry (less the 2nd Battalion which was on Samar), under Col. Stephen S. Hamilton, together with the 2nd Battalion of Col. Aubrey D. Smith’s 306th Infantry, which was attached to the regiment after the landing, was ordered by General Bruce to move northward and take Ipil.35 At about 1045, with the 1st Battalion in the lead, the regiment moved out northward astride Highway 2 toward Ipil. At the same time the division artillery was in position to support the advance. The 306th Field Artillery Battalion had been previously placed in the 7th Division area at a position from which it could fire as far north as Ipil and 6,000 yards inland.36 At first there was little enemy opposition, but the troops observed many well-camouflaged foxholes under the houses, and many stores of Japanese food and ammunition.

Within ten minutes after starting, the 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, was 300 yards north of Deposito and by 1215 had advanced 500 yards farther north. Japanese resistance became heavier as the troops neared Ipil. The remaining troops of the Nonaka Battalion of the 30th Division, consisting of an infantry company and a machine gun company, had landed at Ormoc from junks and “fought bravely” under the command of the Shipping Unit.37 The enemy had emplaced machine guns, and in one instance a cannon, in dugouts under the

houses.38 By 1455 the 307th Infantry was on the outskirts of Ipil, but its advance was temporarily held up when the Japanese exploded one of their ammunition dumps.39 By 1740 the 1st Battalion had cleared the barrio and set up a night perimeter on its northern outskirts. The regiment had killed an estimated sixty-six Japanese and had captured one prisoner of war, a medical supply dump, a bivouac area, and numerous documents.40

The 305th Infantry during the day moved south to the Bagonbon River without serious opposition. Patrols of platoon strength were sent to scout out enemy positions and, if possible, establish contact with the 7th Division which was fighting north along the coast from Baybay. These patrols went as far south as the Panalihan River, destroying three food dumps and knocking out an enemy pillbox.41

During the afternoon enemy aircraft that were molesting the shipping dropped some bombs ashore but no appreciable damage resulted. The division artillery established a command post approximately 200 yards inland on the southern banks of the Baod River. As the beachhead line extended, the artillery moved to the northern banks of the river. This position afforded better cover and concealment. The artillery fired on enemy machine guns, mortars, and troops.42

At 1640 General Bruce issued orders for the regiments to consolidate their positions and form night perimeters. The 77th Division had established a two-mile beachhead extending from Ipil in the north to the Bagonbon River on the south and had penetrated inland nearly a mile.

General Bruce’s plan at this time was to push forward vigorously and capture Ormoc, after which he would drive north, take Valencia, and make contact with elements of the X Corps. Each day he would “roll up his rear” to form a defensive perimeter at night. Patrols would be sent east to locate enemy concentrations and destroy them by artillery fire, and at the same time other patrols would move to the east to search out routes and Japanese dispositions with a view to taking Valencia from the east.43

In planning for the amphibious landing, the Fifth Air Force had ordered the 308th Bombardment Wing to conduct bombing and strafing missions, in addition to providing cover for the movement.44 The plans for 8 December called for the 308th Bombardment Wing to be prepared on request to bomb Camp Downes – a prewar military post south of Ormoc – maintain a close vigilance over Ormoc, and continue the overhead air patrols.45 The 307th Infantry was to move north at 0800 astride Highway 2 and seize Camp Downes. The 305th Infantry was to withdraw from the south and move north in support of the attack of the 307th Infantry and at the same time protect the southern and southeastern flanks of the division. The 902nd Field Artillery Battalion and Company A of the 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion would support the attack. At

least two patrols of the 305th Infantry would be sent south to disrupt enemy communications. All other units of the division were to be prepared to move north on division order.46

Camp Downes

Immediately north of Ipil, Colonel Mitsui had constructed a few small strong points, each of which consisted of two coconut log pillboxes, several trenches, and foxhole emplacements for machine guns. Between these positions and Camp Downes were groups of enemy riflemen and machine gunners on the banks of the streams and at the ends of wooded ridges that extended from the northeast toward the highway. They had dug in at the bases of the trees and on the edges of the bamboo clumps. In the sector between Ipil and Camp Downes the highway was nine feet wide, with three-foot shoulders, and surfaced with coral or gravel. Fields of sugar cane or grassy hills lay east of the road, which was fringed with clumps of acacia or coconut trees. At least one reinforced enemy company had taken up its last defensive stand at Camp Downes. Less than a mile from Ormoc, Camp Downes had been an important Philippine Army and Constabulary camp before the war. The plateau on which it was situated lay east of the highway and commanded all approaches, most of which were open and without cover. A ravine ran along the southern side of the barrio. At Camp Downes the Japanese had placed thirteen machine guns, two 40-mm. antiaircraft guns, and three 75-mm. field pieces under the porches and in the foundations of buildings. These were well camouflaged and mutually supporting and were protected by concealed riflemen.47

As the 77th Division consolidated its positions in Ipil, the Japanese started to use reinforcements to check any further advance toward Ormoc. The 12th Independent Infantry Regiment had been assembling at Dolores, northeast of Ormoc. On the night of 7 December its commander, Colonel Imahori, ordered the newly arrived Kamijo Battalion, which consisted of two companies, to co-operate with the Shipping Unit under Colonel Mitsui in delaying the advance of the American forces until the arrival of the main body of the 12th Independent Infantry.48 By the morning of 8 December it became evident to the 77th Division that it had surprised the enemy.

At 0615 enemy planes flew over the command post area, and ten minutes later one of these was shot down by antiaircraft fire.49 At 0800 Colonel Hamilton’s 307th Infantry moved out.50 By 1000 the regiment was 200 yards north of Ipil, but it encountered more determined resistance when it reached the Panalian River at 1200. General Bruce ordered the attacking force to continue north with the objective of reaching the ravine just south of the Camp Downes plateau. The 307th Infantry was to make the assault and employ if necessary all reserves, while the 2nd Battalion of the 306th Infantry continued to be attached to the regiment in support. The 902nd Field Artillery Battalion,

A patrol of the 307th Infantry warily approaches a river crossing near Camp Downes

Company A of the 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion, and Company A of the 88th Chemical Weapons Battalion were also to continue their support. Farther south, the 305th Infantry would move north to defend the bridgehead at the Baod River and the 77th Reconnaissance Troop would move at 1330 to an area 500 yards north of the Panilahan River to clear out a position for the division command post.51

Upon receiving its mission, a platoon from Company A of the 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion moved over water toward Camp Downes to secure information on the dispositions of the Japanese. The platoon proceeded north 500 yards offshore to the vicinity of Panalian Point where it received heavy enemy artillery fire from Camp Downes. The platoon returned and reported the location of the enemy artillery.52 The 902nd Field Artillery Battalion thereupon shelled the Japanese artillery positions.53

The assault units of the 307th Infantry steadily pushed out against determined opposition in which the enemy used rifles, mortars, and small artillery from dug-in positions along finger ridges and streams. The Japanese had a prepared position 1,000 yards in depth from which they swept the rice fields which the troops had to traverse, but fire from the American automatic weapons and mortars forced the Japanese to fall back.54 An enemy company counterattacked

and hit Company A of the 88th Chemical Battalion. The Japanese were repulsed on two separate occasions – the first time at 1320 and the second at 1520, when in company strength they charged the Americans. The chemical company stopped both charges with high explosive and white phosphorus shells.55 The 307th Infantry pressed forward, capturing considerable quantities of small arms and artillery ammunition, and by nightfall had advanced some 2,000 yards. The 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, was to relieve the regiment’s 2nd Battalion, which had been attached to the 307th Infantry as an assault battalion.56

Colonel Tanzola’s 305th Infantry during the day protected the southern and southeastern flanks of the 77th Division in its advance northward. At night the regiment’s defensive perimeter centered around Ipil but extended as far south as the Baod River.57

The Japanese forces suffered greatly in the course of the day. The commander of the Kamijo Battalion was severely wounded and the battalion itself had many casualties. Consequently, the Tateishi and Maeda Battalions of the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment, which had been alerted to join the Kamijo Battalion, were ordered to take positions north of Ormoc, on the night of 9 December.58 The Japanese troops in the sector opposing the 77th Division were two companies totaling 100 men of the 1st Battalion, 12th Independent Infantry, with three machine guns and two battalion guns; three companies totaling 250 men of the 3rd Battalion of the same regiment with nine machine guns, two battalion guns, and four antitank guns; sixty men with three machine guns from the 30th Division; a paratroop unit of eighty men; a ship engineer unit of 500 men; and 750 personnel from the Navy. The total effective military strength was 1,740 men.59

At 0400 on 9 December the first resupply convoy arrived carrying with it the rest of the 306th Infantry. The 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, was placed on the eastern flank which connected the 305th Infantry on the south with the 307th Infantry on the north. Its mission was to protect the east and center of the beachhead. At 0530 the batteries of the 902nd Field Artillery Battalion fired 110 rounds on a harassing mission and at 0820 they fired 192 rounds in preparation for the attack by the infantry against Camp Downes.60 The 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, was to pass through the 2nd Battalion, 306th Infantry, and continue the attack with the 3rd Battalion, 307th Infantry, on the left. The 1st Battalion, 307th Infantry, would protect the regimental right flank.61 After the artillery concentration the 307th Infantry at 0830 moved out toward Camp Downes.

The 307th Infantry inched slowly forward. It became evident that the Japanese had regrouped and emplaced the forces on ridges and high ground which overlooked all possible approaches to Camp Downes and Ormoc. In selecting his defensive positions the enemy used “excellent judgment”62 and defended the area with at least two companies heavily reinforced with automatic weapons. The assaulting forces received intense small arms and artillery fire.63

The 902nd Field Artillery Battalion supported the attack from positions north of the Baod River. The 305th Field Artillery Battalion, which had just arrived, was sent forward to support the attack.64 At one of the Japanese strong points that had been overrun were found eleven heavy machine guns, two 40-mm. antiaircraft guns, and three 75-mm. guns. At 1700, Japanese aircraft strafed the regiment and inflicted several casualties. At 1750, however, the 307th Infantry entered Camp Downes, secured the area, and established a night perimeter. Its total advance for the day was about one thousand yards.65

At 1245 the 305th Infantry, which had been protecting the southern flank of the division, received a new assignment from General Bruce. The 2nd Battalion of the 305th Infantry was to protect the division’s rear by taking a position just south of Ipil. The 1st and 3rd Battalions were to move north of the Panilahan River and 1,000 yards to the east in order to complete an all-around defense of Camp Downes.66 At 1345 the battalions moved north. As soon as the 307th Infantry entered Camp Downes, General Bruce ordered his forward command post into that area, and the advance echelon of his headquarters moved out. Upon its arrival at the selected camp site, a coconut grove on a hill just south of Camp Downes, the advance echelon became involved in a fire fight between the 307th Infantry and the enemy forces on the hill. It dug in under fire in the new area. The Japanese defenders were driven out of the coconut grove as the rest of the command post moved in.67

During the day the 307th Infantry had advanced about 1,000 yards and captured Camp Downes. The 305th Infantry had secured the area northeast of Camp Downes and protected the northeastern flank of the 77th Division. The 306th Infantry had moved into an assembly area 600 yards north of Ipil.68

Two Sevens are Rolled in Ormoc

At 1830 General Bruce issued verbal orders for the attack on 10 December. Ormoc was the target. The 307th and 306th Infantry Regiments were to move out abreast. The 307th Infantry would attack along the highway to its front while the 306th Infantry would move to the northeast and attempt to envelop the opposing enemy force. The 305th Infantry initially was to remain in position and defend its part of the line.69

Ormoc, the largest and most important commercial center in western Leyte, possessed a concrete and pile pier at which a vessel with a sixteen-foot draft, and two smaller vessels, could anchor at the same time.70 On the route to Ormoc and in the town itself, the Japanese dug strong defensive positions. The favored sites were in bamboo thickets, on reverse slopes, along creek beds, and under buildings. Individual spider holes about six feet deep were covered with logs and earth and “beautifully camouflaged.” Against such positions, artillery and mortar fire did little more than daze the defenders.

Each position had to be searched out and destroyed.71

On 9 December the commander of the Japanese 35th Army ordered the four companies of the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment to return to their regiment from positions north of Ipil and to be prepared to help defend the Ormoc area.72

In preparation for the assault against Ormoc, the 902nd Field Artillery Battalion at 0830 established an observation post at Camp Downes. At 0920 the battalion fired 100 rounds of ammunition during a ten-minute period in front of the area which the attacking forces were to traverse. At 0930 the artillery fire was directed at enemy positions observed in Ormoc.73 General Krueger made arrangements with Admiral Kinkaid for LCMs, LCVs, and LVTs to operate along the coast at dawn and nightfall for an indefinite period.74

At 0900, Company A of the 776th Amphibian Tank Battalion with its 75-mm. howitzers moved into Ormoc – the first American troops to enter the city. The 2nd and 3rd Platoons of the company moved through the streets and sent high explosives and smoke shells into the buildings occupied by the Japanese.75 The enemy defenders were also hit from the bay. LCM(R)’s from the Navy came overwater, moved near the Ormoc pier, and fired their rockets into the center of the town. As the rockets were being fired, the crews of the LCMs engaged the enemy defenders on the pier in a small arms fight, the antiaircraft machine guns on the LCMs exchanging fire with the Japanese rifles and machine guns. After the last of the rockets were launched the LCMs withdrew, still under small arms fire.76

Colonel Smith’s 306th Infantry was to move to the northeast with the 1st and 3rd Battalions abreast and forestall any attempt to reinforce the Ormoc garrison. At 0945 the commanding officer of the 306th Infantry announced that both battalions had moved out on time.77 The 1st Battalion on the left encountered only light opposition during the day. The 3rd Battalion met light resistance in two deep ravines but was able to push through without difficulty. Throughout the day, however, the regiment received harassing fire from well-concealed riflemen, each of whom generally worked alone. By 1600 the 1st Battalion was at a bridge on Highway 2 north of Ormoc and the 3rd Battalion was within 500 yards of the 1st but was slowed by the necessity for maintaining contact with the regiment’s 2nd Battalion. This unit had been committed on the right in order to secure contact with the 305th Infantry.78

At 0930 the troops of the 307th Infantry moved out.79 They encountered little resistance until they neared the outskirts of Ormoc, where a deep ravine lay between the southern edge of the town and the front lines of the advancing troops. An enemy force, which had dug in on both sides and along the top of this ravine, had to be rooted out with bayonets, grenades, and mortars. In spite of the determined enemy resistance, American casualties were very light. Entering the western part of the city, the 307th

Aerial view of Ormoc after the bombardment. In the middle background is the Antilao River, with the mountains of western Ormoc Valley in the distance

Infantry hit the front line of the Mitsui Unit on the left flank of the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment.80

Ormoc “was a blazing inferno of bursting white phosphorus shells, burning houses, and exploding ammunition dumps, and over it all hung a pall of heavy smoke from burning dumps mixed with the gray dust of destroyed concrete buildings, blasted by ... artillery, mortar, and rocket fire.”81

The 306th and 307th Infantry Regiments squeezed the enemy like a tube of toothpaste. The 306th Infantry enveloped the northeast flank, while the drive of the 77th Division up the shore of Ormoc Bay banished any hopes that the Japanese might have entertained of escaping southeast by Highway 2. The Japanese were squeezed through Ormoc to the north.

Left behind, however, were some defenders who heroically but hopelessly fought to delay the American advance. Situated in spider holes beneath the buildings, they stubbornly fought back until overcome. Street by street, house by house, the 307th Infantry cleared Ormoc, which was a scene of gutted buildings and rubble. Many ammunition and signal supply dumps were captured, including a church that had been

filled with artillery and small arms ammunition.82

As his troops were reducing Ormoc, General Bruce made a report to the commanding general of the XXIV Corps on the status of the attack and referred to a promise that had been made by the commanding general of the Fifth Air Force: “Where is the case of Scotch that was promised by General Whitehead for the capture of Ormoc. I don’t drink but I have an assistant division commander and regimental commanders who do. ...”83

At the same time that the 77th Division was entering Ormoc, the 32nd Division was pushing southward toward Ormoc Valley, the 11th Airborne Division was working westward over the mountains toward the town, and the 7th Division was pushing northward along the eastern coast of Ormoc Bay in an attempt to make a juncture with the 77th Division. General Bruce advised General Hodge: “Have rolled two sevens in Ormoc. Come seven come eleven.”84

The 307th Infantry pushed through the town and at 1730 established a night perimeter on the banks of the Antilao River on the western edge of Ormoc where it tied in with the front line of the 306th Infantry. At long last, Ormoc was in American hands.

In its drive north the 77th Division killed an estimated 1,506 Japanese and took 7 prisoners.85 Its own casualties were 123 men killed, 329 wounded, and 13 missing in action.86

On 7 December, the 7th Division moved north from its position about seven miles south of Deposito to join the 77th Division, which had landed that day at Deposito. It advanced with two regiments abreast – the 184th Infantry on the left and the 17th Infantry on the right. The regiments made slow progress as they pushed over a series of hills and river valleys. On the night of 9–10 December the Japanese who were caught between the 7th and 77th Divisions withdrew into the mountains. At 1000 on 11 December an advance element, the 2nd Battalion, 184th Infantry, reached Ipil and established contact with the 77th Division.

The XXIV Corps was now in undisputed control of the eastern shore of Ormoc Bay and the town of Ormoc. The capture of Ormoc had very important effects. It divided the Japanese forces and isolated the remaining elements of the enemy 26th Division. It drew off and destroyed heretofore uncommitted enemy reserves, thus relieving the situation on all other fronts, and it hastened the juncture of the X Corps with the forces of the XXIV Corps. It denied to the Japanese the use of Ormoc as a port, through which so many reinforcements and supplies had been poured into the campaign. Finally, the Japanese were unable to use Highway 2 south of Ormoc and were driven north up Ormoc Valley.87 General Krueger had realized an important part of his plan for the seizure of Ormoc Valley, since sealing off the port of Ormoc would enable the Sixth Army to devote its major effort toward completion of that plan.