Chapter 19: The Entrances to Ormoc Valley

General Bruce’s quick exploitation of the surprise landing of the 77th Division just below Ormoc had resulted in the capture of Ormoc on 10 December. With each successive advance, he had displaced his entire division forward. General Bruce, as he phrased it, preferred to “drag his tail up the beach.”1

With the seizure of Ormoc, General Krueger’s Sixth Army had driven the main elements of the Japanese 35th Army into Ormoc Valley. The Japanese were caught in the jaws of a trap – the 1st Cavalry Division and the 32nd Infantry Division were closing in from the north and the 77th Infantry Division from the south. General Krueger ordered the X and XXIV Corps to close this trap upon the Japanese.

Southern Entrance to Ormoc Valley

Japanese Plans

When General Suzuki, the commander of the Japanese 35th Army, ordered the action against the Burauen airfields, his anticipations had been high. Accompanied by his chief of staff and six other staff officers, he had gone to the headquarters of the 26th Division, in the mountains near Lubi, in order to supervise the operation personally. General Tomochika, the deputy chief of staff, remained at Ormoc because of the advance of the Americans up the west coast, and took command of operations in the area.

A mixed battalion, consisting of four companies, reinforced the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment. This regiment, under Colonel Imahori, was to be prepared at a moment’s notice for action in the Ormoc sector.2 The 16th and 26th Divisions received orders to retreat westward and establish defensive positions in the Ormoc Valley. The 16th Division, which had less than 200 men, had ceased to exist as a fighting unit. The Japanese decided that henceforward their operations would be strictly defensive. The 26th Division started to withdraw through the mountains, but its orders to retreat were very hard to carry out. The Americans had blocked the road, and the 11th Airborne Division units, which had advanced west from Burauen, were attacking in the vicinity of Lubi. As a result, the staff officers of General Suzuki’s 35th Army “disbanded and scattered.” General Suzuki passed through the American lines and reached the command post at Huaton, four miles north of Ormoc, on 13 December; his chief of staff arrived there the following day. As for the 26th Division, “all contact with

the Division was lost by Army Headquarters until the early part of March.”3

In the meantime General Tomochika had prepared new plans. On 6 December he was told by a staff officer of the 1st Division, which was fighting the 32nd Division in the north, that the 1st Division had “reached the stage of collapse.”4 The mission of the 1st Division was then changed to one of defense. Colonel Imahori by the night of 7 December had sent two companies south.5 These companies, known as the Kamijo Battalion, were destroyed at Ipil by the 77th Division in its march to Ormoc. Colonel Imahori, fearful that the rest of his detachment would suffer the same fate, ordered his main force, the Tateishi and Maeda Battalions, to construct positions north of Ormoc. The remnants of the Kamijo Battalion established a position northeast of Ormoc. In his plan for the parachute attack on the Burauen airfields, General Suzuki had decided to use as a part of his attacking force the 4th Air Raiding Landing Unit. In view of the unfavorable situation that had developed, the 14th Area Army commander, General Yamashita, decided that after the 4th Air Raiding Landing Unit landed at the Valencia airfield it was to be kept in the Ormoc area. From 8 to 13 December approximately 500 men from the unit arrived in the Ormoc area, and were attached to the Imahori Detachment. They had traveled only at dawn or dusk to avoid detection.

At the same time, “in order to ease the difficult Leyte Island Operation,” General Yamashita dispatched from Luzon to assist the troops in the Ormoc sector the Takahashi Detachment, composed of the 5th Infantry Regiment of the 8th Division, an artillery battalion, a company of engineers, a transportation company, and a Special Naval Landing Force of 400 men with four light tanks and sixteen trench mortars. In order to suppress the guerrillas, who were active in the Camotes Islands off the west coast of Leyte and who were guarding the entrance to Ormoc Bay, the area army commander ordered a detachment, known as the Camotes Detachment, to those islands. This detachment was composed of one battalion (less two companies) of the 58th Independent Mixed Brigade, an artillery battery, and an engineering platoon.

The transports carrying the troops to the Ormoc area underwent a severe aerial bombardment from American aircraft. As a consequence, only the Special Naval Landing Force arrived at its target. On the same day the transports carrying the Takahashi and Camotes Detachments were forced to put in at Palompon on the west coast. The subsequent advance of these detachments toward Ormoc was greatly delayed.

On 9 December the 77th Infantry Regiment, the last of the Japanese reinforcements for Leyte, landed at Palompon and moved to Matagob. General Suzuki intended to assemble and integrate these units and to launch a counteroffensive against Ormoc starting on 17 December.6

Heavy machine guns cover crossing of the Antilao River by men of the 77th Division at Ormoc

Cogon Defenses

On 10 December General Bruce devised a new scheme of maneuver: the 77th Division was to break loose from its base and use Indian warfare or blockhouse tactics. At night each “fort” was to establish an all-round defense from any Japanese night attacks. In the daytime, an armed convoy was to go “from fort to fort.” The Filipino guerrillas were to guard the bridges and furnish intelligence.7

By nightfall of 10 December the 77th Division had cleared Ormoc. (SeeMap 17.) The front lines of the 307th Infantry were on the western outskirts of the town along the bank of the Antilao River, a stream which flows past the entire western side of Ormoc. At the city’s northern edge the river is crossed by Highway 2, which then proceeds directly north about 300 yards west of the river and parallel to it for a distance of about 1,000 yards. The 306th Infantry on the right of the 307th Infantry had come abreast of that regiment at twilight.

General Bruce’s plan for 11 December provided for a limited attack north to enable the division to straighten out its lines. The 305th Infantry in the afternoon would come between the 306th Infantry on the right and the 307th Infantry on the left. The 305th Infantry was to be prepared to attack on the morning of 12 December with battalions abreast, one on each side of the highway.8

At 0930 on 11 December the 306th and 307th Infantry Regiments jumped off with the 307th Infantry on the left. The assault battalions of the 307th Infantry and the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, attempted to cross the Antilao River but came under heavy fire and were pinned down.

The fire came from a well-fortified position of the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment on the north bank of the river at Cogon, a small barrio on Highway 2 just north of Ormoc. The enemy position was on a small elevated plateau, adjacent to Highway 2, overlooking the river to the south and rice paddies to the east and west. Innumerable spider holes had been constructed throughout the area. The principal defensive position, slightly east of Cogon, was in the vicinity of a three-story reinforced concrete building that had been converted into a blockhouse. The well-camouflaged positions, with the exception of the fortress, were so situated in the underbrush and the waist-high cogon grass that it was impossible to detect them at a distance of more than ten feet. From these positions the Japanese could command the bridge over the Antilao River and deny the U.S. troops the use of Highway 2 to the north. An estimated reinforced battalion with machine guns, antitank guns, and field pieces, together with small arms, defended the area.

The artillery fired on the enemy front lines, which were only twenty-five yards in front of the American assault troops, but failed to dislodge the Japanese. The assault battalions of the 307th Infantry and the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, thereupon delivered point-blank fire from their tank destroyer guns, amphibian tank guns, light and medium machine guns, and infantry weapons on the Japanese position but still could not overcome it. The lack of shipping had prevented the division from taking its medium tanks with it. Unable to move forward, the battalions established their front lines and perimeters for the night along a line just north of Ormoc.

On the division’s right, the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, moved forward against increasingly strong resistance from the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment. After advancing about 1,000 yards the 3rd Battalion encountered a well-entrenched position. Elements of the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment had dug in on a steep ridge in front of which was a deep ravine. Eight hundred yards of rice paddies lay between this position and the one opposing the other battalions, though both positions were part of the same defensive system. The artillery placed fire upon the ridge. Although able to utilize only a company and a half against the enemy position, the 3rd Battalion, under cover of the artillery fire, attacked and succeeded in gaining a foothold on the ridge. The 12th Independent Infantry Regiment at the same time directed two unsuccessful counterattacks against the right flank and rear of the 3rd Battalion. Since the forward elements on the ridge were vulnerable and any further advance would have exposed both flanks of the 3rd Battalion, the commanding officer of the 306th Infantry at 1600 ordered the 3rd Battalion to withdraw the forward units on the enemy-held ridge and consolidate its position.9

At 1600 the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 305th Infantry, moved north of Ormoc and took up the position held by the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, between the 307th Infantry

on the left and the 3rd Battalion, 306th Infantry, on the right. The relieved battalion was ordered to take a position to reinforce the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 306th Infantry. The 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, remained just south of Camp Downes as the extreme right flank of the 77th Division.10

In his plan for the drive of the XXIV Corps up Ormoc Valley, General Hodge ordered the 7th Division to “continue the attack as directed and coordinated” by General Bruce.11 To strengthen the Ormoc defenses, elements of the 7th Division were scheduled to be brought forward. General Bruce planned to attack daily towards Valencia, which was about six and a half miles north of Ormoc. The 77th Division would eventually cut loose from the Ormoc defenses and take up each night an all-round defense. The supply convoy, protected by strong guards, would move along Highway 2 and measure its advance by that of the assault units. The 305th Infantry was to proceed along Highway 2 and the 306th Infantry, while protecting the division right flank, was to be prepared to proceed 2,000 to 3,000 yards east of Highway 2, move north through the hills to a point due east of Valencia, and then turn west across Highway 2 and capture that town. The 307th Infantry, while protecting the division left flank, was to be prepared to relieve the 305th Infantry. The artillery of the division at the outset was to support the advance from Ormoc and eventually move with the forward element of the 77th Division when the latter cut loose from the Ormoc sector.12

Enemy Night Landings

At 2330 on 11 December the 77th Division beach defense units observed a Japanese convoy, which was transporting the Special Naval Landing Force, steaming into Ormoc Bay with the apparent intention of landing at Ormoc. The Japanese evidently thought that Ormoc was still in their hands. The first craft noticed by the U.S. forces was a landing barge with about fifty men, heading directly for the Ormoc pier. By the time the barge came within range of the shore weapons, all shore units were alert and waited with guns trained upon it. They withheld their fire until the barge was within fifty yards of the pier and then all weapons converged their fires upon the craft. The first rounds squarely hit the barge, which immediately burst into flames. The Japanese clambered atop the gunwales and are reported to have screamed, “Don’t shoot,” under the mistaken notion that their forces still occupied Ormoc.

The harbor was lit up by the burning barge and 60-mm. illuminating shells. During the night the Americans discovered that another enemy vessel, about the size of an LST, had pulled into shore northwest of the town under cover of darkness and was busily engaged in discharging troops and equipment. The tank destroyer guns of the 307th Infantry, emplaced along the beach within 1,000 yards of the vessel, opened fire on it while forward observers from the 902nd Field Artillery Battalion directed artillery fire upon the landing area and inland. The enemy vessel attempted to pull out to sea, but after proceeding less than fifty yards it burst into flames and sank. About 150 men, two tanks, a number of rifles, mortars, and machine guns, and a quantity of ammunition had been unloaded before the vessel

sank, but most of the supplies, including four ammunition trucks, had been destroyed by American fire while the vessel was unloading.

The early dawn of 12 December revealed another ship of the same type farther west near Linao. The artillery, mortars, and tank destroyer guns opened up against this vessel as it fled along the shores of Ormoc Bay, and their fire followed until it was out of range. Before the fire ceased, heavy clouds of smoke billowed from the vessel as it moved at a snail’s pace. During the night the American fire had to be closely co-ordinated, since American vessels, including a resupply convoy, were in the bay. Not a single U.S. craft was damaged.

Troops of the Special Naval Landing Force who had disembarked got in touch with Colonel Imahori, who immediately ordered them to go to Highway 2 as the reserve unit of the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment. It was impossible for them to carry out the order, since the 77th Division had advanced north from Ormoc. They thereupon decided to join a naval airfield construction unit at Valencia, but again they failed. In the latter part of December, the men of the Special Naval Landing Force were in the eastern part of the Palompon area without having taken part in the battle for the Ormoc corridor.13

Battle of the Blockhouse

Because the fighting on the previous day had been extremely intense, General Bruce on 12 December consolidated his positions and brought forward supplies and supporting artillery. The front-line units sent out strong combat and reconnaissance patrols to the front and flanks to secure information on the dispositions of the Japanese.14 Throughout the day and night the artillery battalions of the division placed harassing and interdiction fires on the enemy positions across the Antilao River.15

The 902nd and 305th Field Artillery Battalions, two batteries of the 304th Field Artillery Battalion, and one battery of 155-mm. howitzers from the 306th Field Artillery Battalion fired continuously for five minutes on the morning of 13 December at the enemy position in front of the 305th Infantry. So intense was the fire that the enemy soldiers were bewildered and streamed toward the front lines of the division where they were cut down in great numbers by machine gun and small arms fire. The Japanese in and around the concrete building, however, lay low and weathered the barrage.

General Bruce attached Col. Paul L. Freeman, an observer from the War Department General Staff, to the 305th Infantry. Colonel Freeman was made the commander of a special attack force, consisting of Companies E and L, which was to storm the blockhouse. The 305th Infantry, which was to make the main effort, had the 3rd Battalion on the right of Highway 2 and the 2nd and 1st Battalions on the left of the road. The 3rd Battalion in a column of companies moved out at 0830. In support of the 305th Infantry, the 2nd Platoon, Company A, 88th Chemical Battalion, fired on and silenced two enemy machine guns. The Japanese held their fire until the infantrymen were upon them, making it necessary for the artillery to fire at very close range. The fire from the 305th Field Artillery Battalion came to

within fifty yards of the American front lines.

After Company I, the lead company, reached the ridge at 0925, K Company moved up and attempted to consolidate the 3rd Battalion’s position by making an oblique turn to the right flank of Company I. It was hit at 1155 by the first of five counterattacks by the 12th Independent Infantry Regiment. The enemy preceded the infantry assault by artillery, mortar, and automatic weapons fire. The 3rd Battalion estimated the enemy force to be a reinforced battalion. All of the counterattacks were driven off with heavy casualties on both sides.

The 2nd Battalion, 305th Infantry, on the left of the highway, jumped off at 0830 in a column of companies, Company F leading. At 0845 the troops ran into concentrated automatic weapons fire, which pinned them down. Company G moved around the left flank of Company F and also came under heavy fire. A Japanese force estimated as two reinforced companies opposed Companies F and G. With the right flank of Company F on the blockhouse, the 2nd Battalion pivoted on this point until the line ran in a generally northern direction from the blockhouse and faced toward the east. The 1st Battalion faced north and tied in with the 307th Infantry on its left. Colonel Freeman’s special attack force was unable to move forward. The 3rd Battalion held the commanding ground east of Highway 2. The battalions of the 305th Infantry arranged co-ordinating fires that covered all open spaces.16

The 307th Infantry moved westward along the Ormoc-Linao road to forestall any enemy reinforcements and counterattacks from that direction. The troops encountered few Japanese. The 307th Infantry in its advance of 1,000 yards took the barrio of Linao and captured three artillery pieces and two antiaircraft guns, as well as ammunition for those weapons.17

The 306th Infantry, protecting the right flank of the 305th, received no opposition during the day but assisted the attack of the 305th Infantry by fire. Patrols of the 306th Infantry explored the area in the vicinity of Donghol, about two miles northeast of Ormoc, but made no contact with the enemy.18

Although the 77th Division had extended its western boundary during the day by about 1,000 yards, the front lines in the center remained generally where they had been in the morning. The 1st and 2nd Platoons of Company A, 88th Chemical Battalion, laid a continuous smoke screen in front of the troops from 0930 to 1630, enabling the aid men to remove the wounded from the front lines and carry them to the rear.19

During the night of 13–14 December the artillery of the 77th Division delivered harassing and interdiction fires to the front, the principal target being the concrete house that had withstood the onslaught of the previous two days. The 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, received enemy mortar fire during the night, and both it and the 2nd Battalion received light machine gun fire in the early morning hours. The 2nd Battalion destroyed one machine gun with mortar fire.

At 0930 on 14 December Colonel Freeman prepared his special assault force to

renew the attack. Before the jump-off, artillery and mortars laid their fire on the blockhouse and beyond. Under cover of artillery fire the troops cautiously moved out at 1030 with Company L on the right and by 1105 they had advanced 100 yards. Company L knocked out two pillboxes with flame throwers and a tank destroyer gun. Company E found every step of the way contested. The troops used hand grenades and bayonets and literally forced the enemy out of the foxholes in tough hand-to-hand fighting.20 Capt. Robert B. Nett, the commanding officer of Company E, although seriously wounded, refused to relinquish his command. He led his company forward and killed seven Japanese with his rifle and bayonet. Captain Nett was awarded theMedal of Honor.

While Company E was so engaged, Company L on its right advanced through dense foliage and burnt the Japanese out of their foxholes and the bamboo thicket with flame throwers. The company was assisted by armored bulldozers from the 302nd Engineers. For a hundred yards on all sides of the blockhouse, the enemy had dug many deep foxholes only a few yards apart. All the foxholes were covered, some with coconut logs and earth, and others with improvised lids of metal and earth. One was protected by an upturned bathtub. The armored bulldozer drove over the positions, its blades cutting off the tops of the foxholes, after which small arms fire into the holes killed the occupants. The crews of the tank destroyers not only fired point-blank at targets but opened the escape hatches and dropped grenades into the foxholes.21 At 1240 the blockhouse, or what remained of it, was secured.

In the meantime the 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, flanked the blockhouse at 1225 and wheeled 1,000 yards to the east, cutting off the enemy line of communications on Highway 2. The 3rd Battalion, 305th Infantry, remained on the high ground. By 1510 the crossroad north of Ormoc was taken. At the end of the day, the front lines of the 305th Infantry ran south to north along Highway 2 with Company L in the blockhouse sector. A large pocket of the enemy, which had been bypassed by the 1st Battalion, was centered generally in front of the 2nd Battalion. The 307th Infantry was on the left flank of the 305th, while the 1st Battalion, 184th Infantry, which had relieved the 306th Infantry, was on the right flank in Ormoc.22

During the day the 307th Infantry continued its mission of protecting the left flank of the 77th Division in its northward advance and sent patrols and a strong reconnaissance force, consisting of two reinforced rifle companies, one dismounted cannon platoon, and four tanks, west to the banks of an unnamed river near Jalubon. The reconnaissance force killed twenty-one of the enemy, also capturing and destroying great quantities of Japanese matériel and supplies. By the time the perimeter of the 307th Infantry was established in the late afternoon of 14 December, as reported by General Bruce, “the coast line from Ormoc to Jalubon was dotted with fires and the explosions of burning Japanese ammunition dumps.”23

Two other patrols, composed of volunteers from the 306th and 307th Infantry Regiments, reconnoitered approximately 3,000 yards to the west of the 307th Infantry for possible trails for a wide envelopment.24 These patrols met only scattered groups of the enemy and advanced within 2,000 yards of Valencia, returning with the information that an envelopment was feasible.25 During the day the 184th Infantry relieved the 306th Infantry of its mission of holding the coastal defenses, freeing the latter unit for an enveloping movement to the north.

On 15 December the 77th Division consolidated its lines and sent out small patrols. The enemy continued to be very active in the sector of the 305th Infantry. During the night the artillery operating in the 1st Battalion sector knocked out four 2½-ton trucks and killed seventeen of the enemy, while the 2nd Battalion beat off two Japanese counterattacks. In the 3rd Battalion sector all was quiet.

By 15 December the port of Ormoc had been sealed off. It was through this port that the Japanese had sent in a profusion of men, supplies, and equipment, thus prolonging the battle for the island beyond the time anticipated in the original American plans for the operation. The 77th Division estimated that for the period from 11 through 15 December it had taken 9 prisoners and killed 3,046 of the enemy.26 Its own casualties were 2 officers and 101 enlisted men killed, 22 officers and 296 enlisted men wounded, and 26 enlisted men missing in action.27

The Mountain Passage

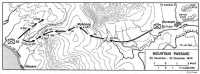

As a result of General Suzuki’s abortive attempt to seize the Burauen airfields, a number of Japanese soldiers remained in the mountains west of Burauen. Most of these were from the 26th Division and they were trying to rejoin the main part of the 35th Army in Ormoc Valley. Earlier, the 11th Airborne Division had started out over the mountains from Burauen in order to relieve enemy pressure on the eastern flank of the XXIV Corps in its drive toward Ormoc. (Map 19)

Mahonag

Just west of Burauen the central mountain range rises abruptly from Leyte Valley to peaks that are 4,000 feet or more in height. Many of the deep, precipitous gorges were impassable even for foot soldiers. No roads went through the mountains but there were short footpaths from one locality to another. Some of these trails led over boulder-strewn, swiftly running streams and frequently bridged deep gorges with a single log where a slip meant a drop of thirty to forty feet. The paths were often so steep that footholds had to be cut into the hillsides, and soldiers were forced to use their hands to avoid falling as much as forty to a hundred feet.28

Map 19: Mountain Passage 25 November-22 December 1944

On 25 November the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment moved west from Burauen for Mahonag, ten miles away. The almost impassable terrain, heavy rainfall, and pockets of lurking Japanese made passage very difficult. It was impossible for the regiment to move as a unit. In small parties, sometimes even less than a squad, the 511th moved forward. “The journey to Mahonag defies description. Sucking mud, jungle vines, and vertical inclines exhausted men before they had marched an hour. Though it rained often during any one trip, still there was no drinking water available throughout the journey.”29 The 3rd Battalion, 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, after considerable hardship entered Mahonag on 6 December.30

On 9 December the 2nd Battalion, though encountering heavy fire from enemy machine guns, mortars, and rifles, pushed steadily forward and established contact with the other units of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment at Mahonag. For several days thereafter, this regiment was busily engaged in sending out patrols. Company G, patrolling in force for two miles to the front, was cut off from the rest of the regiment, which was held down because of strong enemy action. On 13 December the 32nd Infantry pushed northeast from Ormoc Bay in an effort to make juncture with the 11th Airborne Division and assist it in moving out of the mountains.

Drive of 32nd Infantry

The 32nd Infantry also encountered very precipitous hills and its advance was bitterly contested by the Japanese. By the evening of 14 December the regiment had considerably reduced the distance between itself and the 511th Parachute Infantry.

At 0700 on 15 December, as the 3rd Battalion was moving out, a patrol of six men from Company G, 511th Parachute Infantry, entered the battalion’s lines. The rest of Company G was only 700 yards east of the ridge. The patrol reported that Company G had been cut off from the rest of the regiment for four days and was without food.

The 3rd Battalion encountered only slight resistance and at 0950 was on top of the ridge. A platoon moved out to make contact with Company G of the 511th Parachute Infantry. The platoon reached the company, and at 1855 Company G entered the lines of the 3rd Battalion, which fed and sheltered its men for the night.

In the meantime the 1st Battalion had moved out at 0800 and encountered scattered resistance. To the east and south of the 32nd Infantry was an impassable canyon, several hundred feet deep. In order to reach the 511th Parachute Infantry, it would be necessary for the regiment to go either north for an undetermined distance or down the ridge toward the coast and then up again. A third possibility involved crossing the Talisayan River in the foothills several miles to the west. With these facts in mind Colonel Finn asked his executive officer, “Are we to actually contact the 511th personally.[?] What is the purpose of the contact and are we to lead them out by hand[?]”31

At the same time, General Arnold advised the 511th Parachute Infantry of the situation and that “present orders” from General Hodge required the displacement of the 32nd Infantry from its positions in order to wipe out pockets of resistance that remained near Ormoc. The 511th Parachute Infantry was to make every effort to drive toward the position of the 32nd Infantry, since the latter would soon be withdrawn. The 511th would then have to fight it out alone. General Arnold finally decided that the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 32nd Infantry, would be withdrawn and that the 2nd Battalion, which was fresher, would move up and attempt to establish contact with the 511th Parachute Infantry.32

At 0700 on 16 December the 2nd Battalion started eastward along the south bank of the Talisayan River. For the next few days the battalion made slow progress, meeting and destroying small groups of the enemy pushing west. As the troops advanced they were confronted with steep and heavily wooded ridges which were separated by gorges several hundred feet deep. The Japanese, well concealed by the heavy foliage and entrenched in caves, were most difficult to dislodge, but the distance between the 2nd Battalion and the 511th Parachute Infantry daily diminished. On 20 December the 2nd Battalion was held up by the terrain and strong enemy opposition on two ridges to its front. For the next two days the battalion pounded at the Japanese force in attempts to dislodge it. At this time the distance between the 2nd Battalion and the 511th Parachute Infantry had narrowed down. Enemy resistance was overcome on the morning of 22 December. In the meantime the 187th Glider Infantry Regiment passed through the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment and continued the attack. At 1330 on 22 December the 2nd Battalion of the 187th Glider Infantry Regiment passed through the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Infantry, and pushed on to the coast. The difficult mountain passes had been overcome.33

The Drive South

Regrouping of Japanese Forces

When the Americans took Limon, the key point of entrance on Highway 2 into Ormoc Valley from the north, the Japanese

forces were thrown into confusion. The Americans, unknown to themselves, had successfully divided the Japanese 1st and 102nd Divisions that had been charged with the defense of northern Leyte. The Japanese were forced to regroup their various units in an attempt to correct the rapidly deteriorating situation along their front lines. The strong American infantry assaults, which had been co-ordinated with heavy mortar and artillery fire, induced General Kataoka, the commanding general of the 1st Division, to redistribute his forces along Highway 2.34

The onslaught of the X Corps had forced General Suzuki to abandon the earlier plan of advancing the 35th Army north along three widely separated routes. Instead he had to concentrate the main strength of the 1st Division along the highway to check the American advance. The plan to use the 1st Division as a strong offensive force had to be discarded in favor of using it in a strictly defensive role.

The 1st Division had suffered much: as of 2 December, 3,000 of its men had been killed or wounded. Furthermore, one third of the infantry weapons of the 1st Infantry Regiment and two thirds of those belonging to the 57th Infantry Regiment had been rendered inoperable. The infantry was short of grenades and ammunition for the 50-mm. grenade dischargers. “The men were suffering from the effect of continuous fighting, from lack of provisions, overwork, and especially from the lack of vitamins.”35

By this time communications between the 1st Division and other units had broken down. Telephonic and telegraphic communications between the division and 35th Army headquarters were out for long periods of time, and liaison between the division headquarters and front-line units was carried out by messengers moving on foot. The supply lines had also broken down. The 1st Division Transport Regiment found it virtually impossible to supply food and ammunition to the 1st and 57th Infantry Regiments and the 1st Artillery Regiment.

General Kataoka grouped his forces along Highway 2 in the Limon-Pinamopoan area in order to concentrate the maximum strength along Highway 2. The 1st Reconnaissance Regiment was to attack the left flank of the 32nd Division,36 which was already opposed by the 57th Infantry in the Limon sector; the 1st Battalion, less Company 3, and the 2nd Battalion, plus Company 11, of the 49th Infantry were to occupy the 1,900-yard sector two miles southeast of Limon in order to hold back American forces in that area; and the 1st Artillery Regiment was to defend its prepared positions south of Limon. The troops of the 1st Engineer Regiment and other noncombat units were issued small arms and ordered to take part in the defense of Highway 2.37

Drive of the 32nd Division

In order to support the amphibious landing of the 77th Division at Deposito and its subsequent movement northward, General Krueger had ordered the X Corps to make its main effort, beginning on 5 December, by advancing vigorously south astride Highway 2 from the vicinity of Limon.38 Acting on Corps orders, General Gill prepared to move out with two regiments abreast. The 32nd Division consolidated its positions on 5 December, and readied itself for a strong assault south down Highway 2.39 (SeeMap 12.)

The 127th Infantry had pushed past the 3rd Battalion, 128th Infantry, which was south of the Leyte River and west of Limon. The 127th encountered very determined resistance from the Japanese entrenched on the high ground 1,000 yards south of the Leyte River bridge. The well-camouflaged enemy defenses consisted of numerous foxholes and ten-foot-deep spider holes, many of which were connected by interlacing communication trenches.

The terrain that the troops traversed was adapted to defensive fighting, and the 1st Division took full advantage of this fact. There were deep ravines and steep hills where the enemy had dug in on both the forward and reverse slopes. The entire area was covered by heavy rain forest with dense underbrush. The nearly constant rainfall made observation difficult and the maps for the area were very inaccurate.

By 12 December the 32nd Division had “detoured” around the 1st and 57th Infantry Regiments of the 1st Division and was assaulting the Japanese artillery positions south of Limon. On this date the division straightened out its lines, established physical contact between the assault battalions, resupplied the assault units, and sent out patrols. The sector in which the greatest Japanese resistance was encountered continued to be that of the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry. Employing mortars and four tanks, this battalion was able to make only limited gains.40

During the night of 12–13 December the artillery battalions of the 32nd Division fired harassing missions near the perimeters of the 126th and 127th Infantry Regiments and southward on Highway 2 as far as the vicinity of Lonoy.

The 14th Area Army had planned to land the 39th Infantry Regiment and an artillery company from the 10th Division near Carigara on 16 December, but in view of the American 77th Division’s advance to Ormoc the plan was canceled on 11 December. On 13 December General Suzuki attached an

infantry company of about 100 men from the 102nd Division to the 1st Division in order to strengthen the latter’s lines.

On the morning of 13 December the 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, with the assistance of its tanks and heavy mortars, pushed past the Japanese who had held up its advance. In the face of most determined opposition the battalion moved south, destroying the pockets of resistance which had been bypassed. At the end of the day the 2nd Battalion had advanced 400 yards to a position 200 yards north of a roadblock set up by the 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry. The 3rd Battalion, less Company L, which was to remain on the high ground overlooking the road, was to attack south on the east side of Highway 2 and come abreast of the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry.

At 1521 the 3rd Battalion reported that six enemy tanks were coming up the highway. After heavy fighting, the Japanese tanks withdrew at nightfall and returned to the south. The 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry, the southernmost unit of the division, made plans to dislodge the enemy force between it and the 3rd Battalion. The contested ground consisted of an open space 600 to 700 yards long and 200 to 300 yards wide, at the southern end of which were two knolls. The 1st Battalion had men on both knolls but did not control the northern end of the sector where the Japanese had dug in and were using machine guns, mortars, and rifles. The 1st Battalion charged against the Japanese and rooted them out with grenades and mortar fire. Except for this action, only slight gains were registered during the day. The men of the battalion were hungry, having been without food since the previous afternoon. The commanding officer of the battalion renewed a request for additional rations and ammunition, since the one-third ration that had been received the day before was insufficient.

The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 127th Infantry received orders from the regimental commander to advance south with the 1st Battalion on the left, pinch out the 3rd Battalion, 126th Infantry, and link up with the 1st Battalion, 126th Infantry. The 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, moved out in a column of companies and had advanced 400 yards when it encountered forty to fifty Japanese on a ridge to its front, about 150 yards west of the road. The enemy threw blocks of TNT and grenades against the battalion, effectively pinning down the troops. A night perimeter was established.

The 2nd Battalion, 126th Infantry, moved abreast of the regiment’s 1st Battalion throughout the day. Its advance was bitterly contested by the Japanese, who employed machine guns, mortars, and rifles against the battalion, which dug in for the night under fire.41 At 1630 the 11th Field Artillery Battalion fired upon fifteen Japanese who were walking along the road south of Lonoy and killed twelve of them.42

The night of 13–14 December was not quiet. At 2300 an enemy force from the 1st Infantry Regiment broke into the command post of the 126th Infantry. The Japanese set up a machine gun in the area and attacked with grenades and rifles. Bitter hand-to-hand fighting ensued but by 0325 the enemy force was evicted and the area had quieted down. At 0630, with the coming of dawn, the Headquarters Company got things in order and everyone was “happy to hear sound of comrade’s voices.” Six Japanese

Camouflaged U.S. tanks are shown on Highway 2, between Limon and Lonoy

Burning Japanese tanks are checked by 127th Infantry troops north of Lonoy

were killed and two Americans and two Filipinos wounded.43

On 14 December nearly all battalions of the 127th and 126th Infantry Regiments were engaged in moving slowly forward and maintaining physical contact with each other. At 1045 the air observer of the 11th Field Artillery Battalion located what appeared to be a camouflaged four-gun position at a point 300 yards northeast of Lonoy. The battalion fired upon the site and the Japanese fled from the position. The 11th Field Artillery Battalion again fired into the same general area at 1315 and set a supply and ammunition dump and three buildings on fire. At 1530 the battalion and the corps artillery massed their fires in order to cover all of Lonoy.44 At 1730, the 127th Infantry destroyed two enemy tanks going north.

The 126th Infantry, on the same day, moved forward in a column of battalions. The 1st Battalion made a limited advance, since it was very short of ammunition and completely out of food. It did establish a roadblock, however, and made contact with the 2nd Battalion, 127th Infantry. The 2nd Battalion, the northernmost unit of the 126th Infantry, moved slowly behind the 3rd Battalion of the regiment. An interval of about 250 yards existed between the two battalions. The Japanese in front of the 32nd Division, especially in the sector of the 3rd Battalion, had strongly entrenched themselves and resisted the 3rd Battalion from both sides of the highway.

Every bend of the road was lined with ... foxholes dug into the banks of the road and spider holes dug underneath the roots of trees and under logs on the hillsides. It was bitter, close hand to hand fighting and because of the steepness of the terrain, the denseness of the tree growth, the inaccuracy of maps and nearness of adjoining units, artillery and mortar fire could not be used to its full advantage in reducing these positions.45

The main Japanese defensive line had been reached. By 14 December the 32nd Division had advanced more than two miles south of Limon. The 77th Division had crushed the Cogon defenses and was in a position to drive north and make juncture with elements of the X Corps. The northern and southern entrances to Ormoc Valley were denied to the Japanese. The jaws of the Sixth Army trap were starting to close.

Footnotes

Although the force was unable to carry back much of the equipment it captured owing to its small size and the necessity of mobility, it managed to return 1 seacoast range finder, 1 large radio transmitter and 2 20-mm. AA guns.” 77th Div Opns Rpt Leyte, p. 23.

The personnel were brave but the officers lacked sufficient training in modern warfare and it finally did not live up to the expectations of its leaders. The division commander, Lt. Gen. Kataoka worried about the loss of his troops, lacked brave command ability and did not establish any set battle policy. [He refused to commit one of his important units to the defense of Highway 2.] ... therefore the Chief of Staff, Deputy Chief of Staff and senior staff officers were dispatched from Army to Division on three different occasions to urge General Kataoka to submit to these orders. ... Regardless of how much we urged General Kataoka to change his views he would not budge. Colonel Ikeda, the Chief of Staff of the 1st Division [until 13 December] was partially deaf and further because of a former lung ailment, he was unsuited to hold his important position. (Tomochika, True Facts of Leyte Opn p. 18.)

General Tomochika was less than fair to the 1st Division. From its positions in the mountains of northern Leyte, the division contested every foot of advance of the X Corps. General Krueger said of the 1st Division: “This unit more than any other hostile unit on Leyte was responsible for the extension of the Leyte Operation.” (Sixth Army Opns Rpt Leyte, p. 41.)