Chapter 21: Westward to the Sea

The co-ordinated pressure exerted from the north and south on the Japanese forces in the Ormoc area had compelled the commander of the 35th Army to make successive changes in his plans. General Suzuki had abandoned the aerial and ground assault against the Burauen airfields, transferred the field base of the 35th Army from Ormoc to Palompon and, finally, had found it necessary to order the remaining Japanese units on Leyte to retreat to the hills behind Ormoc Valley. General Tomochika said afterward, “The best that the 35th Army could do from then on was to hold out as long as possible.”1

The northwestern mountains of Leyte west of Ormoc Bay provided a difficult barrier to any movement toward the northwest coast. The area was the last one available to the Japanese either for escaping from Leyte or for staging defensive actions. In general, the terrain was rough, increasing in altitude from broken ground and low hills in the north to steep rocky ridges and high hills in the south. The northern part was either under cultivation or covered with cogon grass. Toward the south, the cultivated fields and grasslands were gradually supplanted by dense forests.

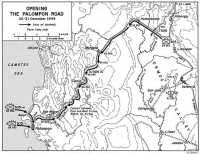

Palompon had been extensively used by the Japanese as an auxiliary port of entry to Leyte. The town was the western terminus of the road that ran north and eastward across the northwestern hills to join Highway 2 near Libongao. (Map 21) It was this road junction that the X and XXIV Corps had seized. The Palompon road, as it was called, followed the lower slopes of the hills until the flat interior valley floor was reached. The confining hills were steep-sided with many knife-edged crests.2 Such was the area into which the forces of the Sixth Army had driven remnants of the Japanese 35th Army.

When the 77th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division joined forces on 21 December just south of Kananga, Highway 2 between Ormoc and Pinamopoan was opened to the Americans. The Sixth Army, anxious to deliver the coup de grâce, arranged its troops for a four-division thrust to the west coast on a long front. In the south the 77th Division was to drive west along the Palompon road. To its right (north) there would be, from left to right, the 1st Cavalry Division and the 32nd and 24th Infantry Divisions. The Sixth Army had started the Leyte Campaign with two corps on a four-division front and was ending its part in the campaign with two corps on a four-division front.

Map 21: Opening the Palompon Road 22–31 December 1944

The 77th Division Goes West

Overwater to Palompon

Guerrillas 3 had informed General Bruce that the bridges on the road that wound through the mountains from the vicinity of Libongao to Palompon either were intact or could be quickly repaired. General Bruce decided to verify this by having an engineer patrol work with the guerrillas and by having a reconnaissance made over the area in a cub plane. On 19 December General Bruce directed that a fast-moving force be organized to operate along the road to Palompon. The engineers later informed him that because of the condition of many of the bridges it would be impossible to send an advance column along the road.4

On 21 December General Hodge, anticipating the juncture of the X and XXIV Corps, ordered the 77th Division to be prepared after that event to move rapidly west and seize the Palompon area.5 On 22 December General Krueger, acting on a recommendation that had been made by General Bruce through General Hodge,6 informed Admiral Kinkaid that it might be possible to expedite the capture of Palompon by having an infantry battalion, utilizing amphibian vehicles and LCMs, make an amphibious movement from Ormoc to the vicinity of Palompon. He therefore asked Admiral Kinkaid if naval support to escort and guide this movement could be furnished for either the night of 23–24 or that of 24–25 December. If possible, the amphibious force should have a destroyer escort.7 Admiral Kinkaid stated, in reply, that because of preparations for other operations it would be “most difficult” to provide a destroyer escort but that he could furnish a PT escort which he believed would be sufficient protection.8 This was satisfactory to General Krueger and he ordered the XXIV Corps to make plans for the amphibious movement.9 In turn General Hodge told General Bruce to prepare for the operation.

On 22 December, General Bruce put his plan into operation. The 1st Battalion, 305th Infantry, was to make the amphibious landing in the vicinity of Palompon while the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were to proceed west along the Palompon road, after moving in trucks from Valencia to the Palompon road near the Togbong River. Previously, on 21 December, Battery A of the 531st Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm. gun) was brought with a great deal of effort to a position near San Jose from which it could fire on Palompon, which the guerrillas and civilians had received instructions to evacuate.10

The 1st Battalion was to commence loading at 1400 on 23 December at Ormoc. The convoy was to be protected en route by patrol torpedo boats and close air support. Upon arriving at Palompon at 0500 on 25 December, the mortar-firing LCMs were to bombard the shore before the assault forces moved in. Beginning 23 December, the artillery of the 77th Division was to bombard Palompon and to continue as long as Lt. Col. James E. Landrum, the task force commander, desired it.11

The 1st Battalion was to move ashore on the beach about 1,500 yards north of Palompon with Companies C and B in assault, Company C on the left. Its mission was to destroy the enemy force in Palompon and then turn north.12

In support of the proposed landing, aircraft from the Fifth Air Force bombed Palompon on 23 December. The results were “hot stuff,” an overenthusiastic observer reported, claiming that “only half of two houses were left standing in the whole town.”13

On 23 December, the reinforced 1st Battalion moved to Ormoc to prepare for the amphibious landing and at 1930 on 24

Palompon after Allied Bombings. Note bomb craters in foreground

December the troops embarked.14 The convoy departed at 2000. The vessels included, in addition to the mechanized landing craft, the LVTs of the 718th and 536th Amphibian Tractor Battalions. They made the tedious ten-hour trip without incident as far as enemy action was concerned, although three of the LVTs “sank owing to mechanical failure.”

The vessels took position off the landing beaches on the morning of 25 December. After the 155-mm. guns of the 531st Field Artillery Battalion had fired from positions near San Jose, twelve and a half miles east of Palompon, the mortar boats of the 2nd Engineer Special Brigade softened up the beaches. The landing waves then started for the shore, the first wave landing at 0720 and the last one at 0755. They received no hostile fire.

“Meanwhile,” wrote General Bruce, “the Division Commander could stand it no longer and called for a plane, flew soon after daylight across the mountains and seaward, located the amphibious forces still at

sea, ... witnessed the preparatory fires by the 155-mm. guns and that from the mortar boats ... saw them going in ... and advance to the beach. (He obeyed a rather boyish impulse and flew from 25 to 50 feet above the heads of the troops in the assault boats and leaned out, giving a boxer’s victory sign with both hands.)”15

The troops quickly organized on the beach. A light fast armored column moved north to clear the road and to forestall any Japanese counterattack from that direction as the rest of the task force went rapidly south through the barrio of Look to Palompon, which fell at 1206. This closed the last main port of entrance on the island to the Japanese. Within four hours after hitting the beaches the battalion had secured the barrios of Buaya and Look as well as Palompon, and had strong patrols operating to the northeast and south. The troops met no opposition at any point. It was doubtless with great satisfaction that General Bruce sent the following message to the Commanding General, XXIV Corps: “The 77th Infantry Division’s Christmas contribution to the Leyte Campaign is the capture of Palompon, the last main port of the enemy. We are all grateful to the Almighty on this birthday of the Son and on the Season of the Feast of Lights.”16 The 1st Battalion received “warm congratulations and thanks” from General Krueger.17

The 1st Battalion occupied a defensive position in the vicinity of Look on 25 December, and rested on 26 December, which was Christmas Day back home. It spent the next five days sending out patrols and awaiting the arrival through the mountains of the rest of the 305th Infantry. On 30 December, Company C made a reconnaissance in force and an amphibious landing at Abijao, about seven miles north of Palompon. The company overcame some Japanese resistance and burned down the town to prevent its reoccupation. It then pushed 1,300 yards north and established radio contact with elements of the 1st Cavalry Division, which had pushed through the mountains to the vicinity of Villaba.18

The Palompon Road

The Palompon road wound through the mountains and crossed many rivers, over which some forty bridges would have to be built or repaired. It ran northwest two and a half miles from the Togbong River to the barrio of Humaybunay and then cut sharply to the southwest for about four miles to Matagob, at which point it went into the hills almost directly south for about 2,000 yards, and then turned south-southwest for 1,000 yards. At this point it turned and twisted to the southwest for approximately five and a half miles to the vicinity of San

Miguel, from where it arched 3,500 yards to Look, on the Camotes Sea.

The Japanese had pockmarked Matagob and the area surrounding it with foxholes and emplacements and had dug spider holes under the houses. South of Matagob, where the road climbed into the hills, the enemy had utilized natural caves, gullies, and ridges on both sides of the road and dug many deep defensive positions. Some of these were eight feet deep, two feet in diameter at the top, and widened to six feet at the bottom. The Japanese had emplaced machine guns in culverts and had constructed several well-camouflaged coconut log pillboxes on the forward slopes of the ridges. An excellent, almost invisible installation, which served as an observation post, was dug in on the forward slope of a ridge about three miles north of San Miguel. It had a concealed entrance on the reverse slope. From this post eight miles of the road to the north and east could be observed.

The Japanese 5th Infantry Regiment was the principal enemy unit in the sector, although remnants of other units retreating west from Highway 2 were in the area. The following Japanese units were identified: 1st, 3rd, and 6th Batteries of the 8th Field Artillery Regiment; elements of the 8th Division Signal Unit; the 8th Transport Regiment; and the 8th Engineer Regiment. Although intelligence officers estimated that there were between 2,000 and 3,000 enemy troops in the sector, only a force of about battalion strength opposed the 305th Infantry. The rest had scattered into the hills to the northwest.

At 0700, on 22 December, the 2nd Battalion, 305th Infantry, left Valencia followed at 1035 by the 3rd Battalion. The 2nd Battalion crossed the Togbong River, moved through the 1st Battalion, 306th Infantry, and at 1030 attacked along the Palompon road. The battalion had advanced 1,600 yards northwest by 1230 and secured the Pagsangahan River crossing. The assault continued with the 3rd Battalion coming up on the right flank of the 2nd. The battalions moved through rice paddies and through Humaybunay and established a night perimeter about one mile southwest of the barrio.

The 302nd Engineer Battalion, which followed behind the assault battalions, fought the “battle of bridges.”19 The engineers worked around the clock, frequently without any infantry protection, to restore the bridges as soon as possible. The bridges were to be sufficiently strengthened initially to support 2½-ton truck traffic for infantry supply, then they were to be reinforced to carry 20 tons in order to bring M8’s forward, and eventually to 36-ton capacity to carry the M10’s. General Bruce had hoped that sufficient Bailey bridges could be made available for important crossings to carry traffic while engineers built wooden bridges under the Bailey bridges. Only a limited number of Bailey bridges were furnished, however, and engineer progress to the west was slowed down.20

The assault battalions of the 305th Infantry that were astride the Palompon road spent a quiet night. They had before them the enemy’s strongly fortified positions at Matagob. At 0830 on 23 December, the 2nd Battalion moved out, followed at 1130 by the 3rd Battalion. The 2nd Battalion moved forward west of the road while the 3rd advanced east of the road. Intermittent enemy rifle fire fell upon the 2nd Battalion but it pushed ahead steadily. At 1500, the 2nd Battalion

was 500 yards beyond Matagob and the 3rd was 300 yards behind the 2nd. The troops came under heavy fire from two enemy 75-mm. guns on the hills west of Matagob and suffered several casualties. The mortars and artillery with the 305th Infantry silenced the Japanese guns. The regimental commander issued orders for the battalions to move out for the assault at 1000 on the following day against the regimental objective, a road bend that was 2,000 yards to its front. The 2nd Battalion set up its night perimeter in place while the 3rd Battalion withdrew to a point 1,000 yards east of Matagob. The regimental command post moved from Humaybunay to the 3rd Battalion perimeter.21

During the night the Japanese made several attempts to penetrate the American lines. The 3rd Battalion destroyed a demolition squad that entered its position, while the 2nd Battalion beat back one attack at 0245 and another one, which was accompanied by mortar fire, at 0630. The 305th Infantry killed an estimated 100 Japanese with no casualties to the regiment.22

At 1000 on 24 December the assault troops jumped off. The Japanese resistance was light and intermittent, but American progress was slow because of the rough, irregular hills in which the enemy had established positions in foxholes, spider holes, and caves. Since it was not possible to bypass these positions, the regiment had to clear each one before the advance could continue. The force received some artillery fire but a mortar platoon from Company A, 88th Chemical Weapons Battalion, silenced the enemy guns. At 1500 the battalions set up their night perimeter 500 yards short of the road bend. During the night a Japanese force of twenty men, which tried to penetrate the defenses of the 3rd Battalion, was killed.23

At 0800 on 25 December the attack was renewed, but made very slow progress. The enemy, dug in in small pockets along the road, resisted stubbornly. The 3rd Battalion advanced 200 yards and was pinned down by machine gun, mountain gun, and rifle fire. The 2nd Battalion attempted to envelop the enemy strong point on the Japanese right (south) flank but was repulsed.24

On 26 December the regiment limited its activity to patrolling. Since it was Christmas Day in the States, “All guns of the Division Artillery fired ... at ... 1200 as a salute to the nation on Christmas Day. This was followed by one minute of silent prayer for the dead and wounded of the 77th Division.”25 That night General Bruce ordered the troops to build bonfires and sing, and employ other ruses in the hope that the Japanese might believe that the troops were celebrating Christmas and might therefore try to enter the defensive perimeters. These ruses were unsuccessful in the sectors of the assault battalions, but a similar one employed in the area of the regimental command post attracted some Japanese patrols, which were either destroyed or driven off.

At dawn on 27 December the 3rd Battalion moved around the Japanese left flank toward the high ground six hundred yards from the line of departure. Despite enemy artillery and machine gun fire and the difficult terrain, the battalion reached the objective, killing 160 Japanese. The remainder fled to the hills.

When it became apparent that the Japanese resistance was strong and determined and might unduly delay the progress of the 305th Infantry, General Bruce decided to move the 2nd Battalion of the regiment overwater to the vicinity of Palompon at the western terminus of the road. The 2nd Battalion could then attack east along the road while the 3rd Battalion continued the attack west. The Japanese defenders would thus be under fire on their front and rear. This eastern attack force, which was called the Provisional Mountain Force, moved to Ormoc and thence, after arrangements had been made with the naval representatives of Krueger’s staff, overwater by LCMs to Palompon. It arrived at the latter without incident at 1500 on 28 December. On the same day the 3rd Battalion, reinforced, continued the attack westward. The Japanese resisted strongly with small arms fire from pillboxes and with artillery. The 3rd Battalion advanced approximately 1,000 yards during the day.26

At 0800 on 29 December, the 3rd Battalion moved out. The battalion had advanced 650 yards at 1000 when it encountered very determined resistance from an enemy force in very well camouflaged, dug-in positions. The troops were pinned down for the rest of the day. The Provisional Mountain Force moved out of Look at 1200 to a position from which it could launch its assault eastward along the road.

At 0930 on 30 December the 305th Infantry struck along the Palompon road, the 3rd Battalion driving west, and the Provisional Mountain Force attacking east. The Mountain Force encountered only scattered resistance until 0930, when the Japanese, from well-entrenched positions in the precipitous sides of the road at a point about four miles east of Palompon, directed strong machine gun fire along the road. The Mountain Force dug in for the night on high ground overlooking the point at which its advance had been halted. The 3rd Battalion succeeded in overcoming the opposition which had halted it the previous day, and pushed forward to a point about 1,000 yards southwest of Tipolo. The Japanese had emplaced artillery on curves in the road and could fire directly on the advancing American troops. Although the 305th Infantry lost one tank to enemy artillery fire, it was able to destroy three 75-mm. guns and capture two others intact.27

During the night, the Japanese force withdrew; only scattered troops were left to delay the advance. At 0800 on 31 December, the assault forces of the 305th Infantry resumed the attack, and encountered only sporadic rifle fire. At 1225 at a point two miles northeast of San Miguel the 3rd Battalion and the Provisional Mountain Force met. This ended all organized resistance along the Palompon road and secured an overland route from Highway 2 in the Ormoc Valley to Palompon on the west coast.28 The 77th Division made the astounding estimate that for the period from 21 through 31 December 1944, it had killed 5,779 Japanese, taken 29 prisoners, and had lost 17 men killed, 116 wounded, and 6 missing in action.29

X Corps Goes West

Meanwhile, to the north of the 77th Division, elements of the 1st Cavalry Division and the 32nd Infantry Division had turned

off Highway 2 and were pushing over the mountains to the west coast.30

The 1st Cavalry Division

With the clearing of Highway 2 and the junction of the X and XXIV Corps at a point just south of Kananga, the 1st Cavalry Division was in readiness to push toward the west coast in conjunction with assaults by the 77th Division on its left and the 32nd Division on its right. The troops were on a 2,500-yard front along Highway 2 between Kananga and Lonoy.

On the morning of 23 December the assault units of the 1st Cavalry Division moved out from the highway and started west. None encountered any resistance. The 1st Squadron, 12th Cavalry, established a night perimeter on a ridge about 1,400 yards slightly northwest of Kananga. The 1st Squadron, 5th Cavalry, set up a night perimeter 1,000 yards north of that of the 1st Squadron, 12th Cavalry, while the 1st Squadron, 7th Cavalry, dug in for the night on a line with the other two squadrons.

This first day’s march set the pattern for the next several days. The regiments pushed steadily forward, meeting only scattered resistance. The chief obstacles were waist-deep swamps in the zone of the 12th Cavalry. These were waded on 24 December. The tangled vegetation and sharp, precipitous ridges that were henceforward encountered also made the passage slow and difficult.

On 28 December, the foremost elements of the 5th and 12th Cavalry Regiments broke out of the mountains and reached the barrio of Tibur on the west coast, about 2,800 yards north of Abijao. By nightfall on the following day, the 7th Cavalry was also on the west coast but farther north. In its advance it had encountered and destroyed many small, scattered groups of the enemy, most of whom showed little desire to fight. The regiment arrived at Villaba, two and one-half miles north of Tibur, at dusk, and in securing the town killed thirty-five Japanese.

During the early morning hours of 31 December, the Japanese launched four counterattacks against the forces at Villaba. Each started with a bugle call, the first attack beginning at 0230 and the final one at dawn. An estimated 500 of the enemy, armed with mortars, machine guns, and rifles, participated in the assaults, but the American artillery stopped the Japanese and their forces scattered. On 31 December, the 77th Division began to relieve the elements of the 1st Cavalry Division, which moved back to Kananga.

On the morning of the 30th of December, the 7th Cavalry had made physical contact northeast of Villaba with the 127th Infantry, 32nd Division, which had been driving to the west coast north of the 1st Cavalry Division.

The 32nd Division

On 22 December the 127th Infantry had reached Lonoy and made contact with the 7th Cavalry. On the following day the troops rested.31 The 128th Infantry had been

engaged in sending out patrols throughout the Limon area from 11 to 18 December. These patrols were successful in wiping out pockets of resistance that had been bypassed by the advance forces of the 32nd Division in the division’s drive along Highway 2 to the south. On 20 December, the 128th received orders from General Gill to prepare for a move to the west coast.32

Both the 127th and 128th Infantry Regiments sent out patrols on 23 December to reconnoiter the terrain. At 0800 on 24 December the two regiments started for the west coast. Throughout the march to the sea, they encountered only small parties of the enemy, who put up no effective resistance, but heavy rains, dense, almost impassable forests, and steep craggy hills slowed the advance.

The commanding officer of the 127th Infantry said of the hills encountered on 24 December:–

The morning was spent in climbing to the top of a mountain ridge. The climbing was difficult but as we later found out, the descent was much worse. The trail led almost perpendicular down the side. After reaching the bottom, another ridge was encountered, this almost straight up, everyone had to use hand holds to pull themselves up. All in all there were seven ridges from the bottom of the first descent to the first possible bivouac area.33

The hills were less rugged from then on. On the morning of 25 December, the 1st Battalion, 127th Infantry, encountered and dispersed 300 to 400 Japanese. Throughout the march both regiments received supplies by airdrop, which was not completely satisfactory since none of the drops was made at the requested time and frequently there was a wide scattering of supplies.

On the afternoon of 29 December the two regiments were on their objectives: the 128th Infantry on the high ground overlooking Tabango and Campopo Bays and the 127th Infantry on the high ground overlooking Antipole Point, approximately three miles to the south. Patrols were sent out to scout the terrain and establish contact with the 1st Cavalry Division on the south and with the 24th Infantry Division on the north.34

The 24th Infantry Division35

The 24th Division, after having been relieved by the 32nd Division on Breakneck Ridge, had protected the rear areas on a trail leading from Jaro to Ormoc. Two weeks before the march to the west coast a large Japanese convoy had been attacked by U.S. aircraft and forced into San Isidro Bay on the northern part of the west coast. Although the vessels were destroyed, some of the troops were able to get ashore. On 9 December they headed toward Calubian, on Leyte Bay about six miles northeast of San Isidro. General Woodruff, who had replaced General Irving on 18 November, ordered Colonel Clifford’s 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry, which had been defending Kilay Ridge, to wipe out the part of the enemy force that had landed at San Isidro and fled northeastward to the vicinity of Calubian.

At 2300 on 21 December, Colonel Clifford notified Colonel Dahlen, the commanding officer of the 34th Infantry, that a Japanese force of about 160 men was at Tuktuk, about four miles south of Calubian. He added that at 0800 on the following morning the 1st Battalion would move out and destroy the force.

At 0300 a force consisting of a platoon from Company C and a platoon from Company A moved toward the high ground northwest of Tuktuk in preparation for the assault, but because of very poor trails the force was delayed. In the meantime four LVTs with a platoon of mortars moved over water to Tuktuk. At 0830 the attack started, with machine guns mounted on the LVTs and mortars furnishing supporting fire. The Japanese resistance was sporadic, although some mortar fire was received. As the troops of the 34th Infantry neared the barrio, the enemy defenders broke and fled, and the town was deserted as the soldiers entered. Approximately thirty enemy dead were counted in the barrio and vicinity. The fleeing enemy force was later destroyed by patrols that worked over the sector. The Japanese had obviously been looting because linens, silverware, and women’s clothing were found in their packs. One soldier had a baby’s high chair tied on the top of his pack.

On 23 December, Col. William W. Jenna, former commanding officer of the 34th Infantry, returned from sick leave in the States and assumed command of the 34th Infantry. With his arrival plans were expedited to clean up the northwestern end of the Leyte peninsula in conjunction with the assaults of other units of the Sixth Army.

From 23 to 26 December, extensive patrolling was conducted along the west coast of the Leyte peninsula. On 26 December the 34th Infantry issued orders for clearing the part of the Leyte peninsula in its zone. The 1st Battalion was to secure all trails and high ground in the interior, prevent any enemy movement to the north and to the east, and, finally, be prepared to assist the 2nd Battalion in the capture of the San Isidro Bay area.

At 2245 on 26 December the LCMs at Villalon (a barrio on Biliran Strait and about six miles northwest of Calubian) began to load Companies F and G. By 2300 the embarkation was completed and the craft moved to Gigantangan Island, arriving there fifteen minutes after midnight. The troops disembarked and slept. At 0530 they again embarked and proceeded to Taglawigan, arriving there at 0730. After strafing the shore the companies landed, meeting no resistance. At the same time Company F completed its assignment without opposition, pushing east and south and encircling Taglawigan. Before noon, some elements of the 2nd Battalion were moving overland to Daha, about two miles to the south, while others had re-embarked and were making an overwater movement toward it. By noon Taglawigan and Daha had fallen to the 2nd Battalion.

Company G, reinforced, left Company F at Daha, re-embarked on the landing craft, and headed toward the San Isidro Bay area, 6,000 yards to the south. As the convoy neared San Isidro, it came under machine gun fire from the barrio and the hills to the southwest. A frontal attack on the town was abandoned and the landing craft moved to the southwest of the jetty to make their landing. The LVTs mired in the mud about 100 to 150 yards offshore. The rest of the force, which was in the LCMs, waded ashore. Some of the troops from the LVTs met with great difficulty in trying to get

ashore but the LVTs finally succeeded in retracting and picked them up. Approximately 150 soldiers with supplies for the task force returned to Gigantangan Island. The convoy had only one casualty.

In the meantime, the 1st Battalion had received orders at 1300 to take San Isidro. The battalion moved overland from Calubian and at nightfall it dug in on the high ground overlooking San Isidro.

At 0800 on 28 December, the co-ordinated assault was made against San Isidro, with elements of the 2nd Battalion attacking from the north while the 1st Battalion attacked from the east. The troops encountered light resistance, the Japanese defenders being only partially armed. Fifty-five of the enemy were killed and one prisoner was taken. By 1230, the 1st Battalion was outposting San Isidro.

With the capture of San Isidro, the last main point on the Leyte peninsula was safely in the hands of the 34th Infantry. The troops moved south along the coast and destroyed small, poorly equipped groups of the enemy. One group of Japanese, whose only weapons were bayonets attached to bamboo poles, tried hopelessly to break through the lines.

On 1 January 1945, the 77th Division was ordered to relieve the 32nd and 24th Infantry Divisions and the 1st Cavalry Division. The relieved divisions were to move to staging areas and prepare for future operations.

The Japanese Retreat

Condition of Japanese Forces

The morale and physical condition of the Japanese Army were very low. With the juncture of the American X and XXIV Corps, the 35th Army had begun to disintegrate. Desertion became common. The wounded would not assemble with their units. The problem of the wounded became serious since there were no proper facilities for medical treatment. General Tomochika later said: “Commanders employing persuasive language frequently requested seriously wounded soldiers at the front to commit suicide; this was particularly common among personnel of the 1st Division and it was pitiful. However the majority died willingly. Only Japanese could have done a thing like this and yet I could not bear to see the sight.”36

Those of the slightly wounded that could not march with the able-bodied soldiers walked by themselves. They became separated from their units and some, although able to do so, refused to rejoin their outfits, giving their wounds as an excuse. In addition there were deserters who fled to the hills. The 35th Army began the policy of sending the slightly wounded back to the front lines. Many of the service units, such as the Mitsui Shipping Unit and the air corps ground crews, refused to fight since they were not trained as combat troops. “Even the artillery and antiaircraft units retreated without facing the enemy. Their excuse was that they were not trained to fight as infantry and were useless without their guns.”37

Doubtless, some of the unwillingness of the Japanese service troops to serve on the front lines was due to their physical condition. When the 1st Division arrived on Leyte on 1 November it brought with it enough food and ammunition for one month, and by 1 December this supply was exhausted. On 3 December an additional one-half month’s supply was brought in at Ormoc;

but this was destroyed or captured by the 77th Division in its advance. Consequently after the 1st of December all Japanese troops on Leyte “were on a starvation diet and had to live off the land.”38 The 1st and 57th Infantry Regiments were the principal sufferers. The men were forced to eat coconuts, various grasses, bamboo shoots, the heart fibers of coconut tree trunks, and whatever native fruits or vegetables they could forage. When the troops received orders to withdraw to the west coast of Leyte, “they were literally in a starved condition, ... many instances occurred in which men vomited seven to ten times a day because they could not digest some of the food due to their weakened stomachs.”39

The 1st Division abandoned much equipment, ammunition, and rations along the highway through the Ormoc Valley. Many of the stragglers and deserters clothed and fed themselves with the abandoned matériel. The chief of staff of the 35th Army stated that when the Americans captured army headquarters, he left the headquarters without any clothing. However, he picked up “a new uniform and sufficient food while on the road.”40

Withdrawal Plans

On 19 December, General Suzuki, the commander of the 35th Army on Leyte, had received word from the 14th Area Army in Manila that henceforth the 35th Army was to subsist on its own resources and what it could obtain within its operational area.41

On the same day, probably because of the information received from Manila, General Suzuki ordered a conference of the staff officers of the 1st and 102nd Divisions. At this meeting, General Suzuki ordered the 1st Division to retreat to the northern sector of the Matagob area and the 102nd Division to the southern part of the same sector. At Matagob the divisions were to reorganize for a counterattack. The order did not give any specific time for the withdrawal; each division was to take action according to the situation in its sector. On 20 December, General Suzuki moved his headquarters farther west to a point approximately three and a half miles north of Palompon.42

On 21 December, the 102nd Division, which had about 2,000 men, began to withdraw to the vicinity of Matagob. The division, having failed to get in touch with the 35th Army, moved to the west coast near Villaba, approximately ten miles north of Palompon.43 It made contact with the 1st Division at the end of December, and also with the 68th Infantry Brigade and the 5th Infantry Regiment, which were already in that sector.44 The 1st Division also began to withdraw on 21 December, making the withdrawal in two columns. The southern column consisted of about six hundred men of the 49th Infantry Regiment, 1st Division Transport Regiment, and other units. On its way west, it was met on 23 December by the 68th Brigade which, unaware of the loss of the Ormoc road, was proceeding toward the highway. The brigade joined the southern column, which reached the Bagacay

sector the following day. (The barrio of Bagacay is six miles northeast of Villaba.) The northern column also had about six hundred men and consisted of elements of the Division Headquarters, the 1st Infantry Regiment, the 57th Infantry Regiment, and other units. The detachment was forced to cut its way through dense jungle. On 25 December it was attacked by the Americans and further decimated. That night the northern and southern columns met at Bagacay and on the following day started towards Matagob. On the 28th, following orders from General Suzuki, they turned north and established defensive positions on the eastern slope of Mt. Canguipot, two and a half miles southeast of Villaba.45

As the Japanese, pursued by the forces of the X and XXIV Corps, spiritlessly retreated toward the mountains of western Leyte, Imperial General Headquarters notified the Japanese people: “Our forces are still holding the Burauen and San Pablo airfields and continue to attack the enemy positions. Our forces are fighting fiercely on the eastern mountain slopes near Ormoc and Albuera.46