Chapter 11: Protecting XIV Corps’ Rear and Flanks

The Problem and the Plan

At the end of January the speed of XIV Corps’ progress toward Manila continued to depend largely upon the pace of I Corps’ advance to the east and south. (See Map III.) On 31 January XIV Corps was preparing to send the 37th Division on toward Manila along Route 3, while the 1st Cavalry Division, recently attached to the corps, was assembled at Guimba and making ready to mount a complementary drive toward the capital down the east side of the Central Plains via Route 5.1

XIV Corps had made provision to secure its right rear and its line of communications against the threat posed by the remaining troops of the Kembu Group by directing the 40th Division to resume the westward offensive in the Clark Field area and drive the Kembu Group deeper into the Zambales Mountains. Some additional measure of protection had been given XIV Corps’ right by XI Corps, which had landed on the west coast of Luzon north of Bataan and was well inland toward the base of Bataan Peninsula by the end of January. Although XI Corps had not, as MacArthur had hoped, “completely dislocated” the resistance the Kembu Group offered, the corps had pinned down a first-class Japanese infantry regiment that might otherwise have been deployed to good advantage at Clark Field.2 Furthermore, MacArthur and Krueger hoped that opposition in front of XIV Corps, as that corps drove on toward Manila, might be at least partially dislocated by the 11th Airborne Division, which, under Eighth Army direction, had landed on 31 January along Luzon’s west coast south of Manila.3 The principal problem, then, was still the security of the XIV Corps’ left rear, security that I Corps had to provide.

Directed by General Krueger to move up in strength to the Licab–Lupao line, I Corps had set its 6th Division in motion toward the southern section of that objective line on 28 January.4 That afternoon the 6th Division had troops in Victoria and Guimba, which previously marked the unit’s limits of reconnaissance, and on the next day relieved a 37th Division outpost at Licab, five miles east of Victoria.5 Encountering no opposition, the 6th Division left sped eastward

on 29 January along a good gravel road that led through hot, dry, flat farm land and cut Route 5 in the vicinity of Talavera, almost twelve miles east of Licab. On 30 January, after a skirmish with a small Japanese force, the division secured the road junction barrio of Baloc, on Route 5 about five miles north of Talavera. Far more easily than expected, the 6th Division had severed the main line of communications between the Shobu and Shimbu Groups, two-lane, paved Route 5.

Muñoz, marking the northern end of the 6th Division’s section of the Licab–Lupao line, lay on Route 5 and the San Jose branch of the Manila Railroad some five miles north of Baloc. On 27 January the 6th Reconnaissance Troop reported the town unoccupied, but upon reinvestigation the next day discovered a strong Japanese force in and around the town. On the 30th one rifle company of the 20th Infantry, 6th Division, unsuccessfully attempted to clear the town, and the 6th Division learned that the objective was not to be taken without a stiff fight.

Meanwhile, the 6th Reconnaissance Troop had ranged far to the south of Muñoz and Talavera. On the 28th, elements of the troop reached the vicinity of Cabanatuan, about seven miles south of Talavera and nearly fifteen east of Licab. Unlike XIV Corps patrols a few days earlier, the 6th Division’s reconnaissance units reported that a strong force of Japanese held Cabanatuan, but the 6th Reconnaissance Troop found no other signs of Japanese south of Talavera and Licab. Other 6th Division patrols learned that the Japanese had established a counter-reconnaissance screen west of Muñoz and San Jose.

The 25th Division, on the 6th’s left, had not been successful in moving up to its portion of the Licab–Lupao line. Coming out of army reserve on 28 January, the 25th Division’s 35th Infantry marched east along Route 8 from Resales and by evening the next day, unopposed on its advance through hot, dry, rice-paddy country, had reached barrio Gonzales, on gravel-paved Route 8 nearly ten miles west-northwest of Lupao. In the meantime the 27th Infantry, moving overland via narrow, dusty, dirt roads south of Route 8, had driven a Japanese outpost from barrio Pemienta, on Route 8 three miles east of Gonzales.

Unknown to the 25th Division, a small tank-artillery force of the 2nd Tank Division had been trapped along the highway between Gonzales and Pemienta. From 2000 on the 29th until 0430 the next morning the force tried unsuccessfully to break through a perimeter the 27th Infantry had established at Pemienta. By the time the action had ended the American regiment had killed 125 Japanese and had destroyed 8 tanks, 8 artillery prime movers, 4 tractors, 8 105-mm. howitzers, 5 trucks, and miscellaneous other equipment. The 27th Infantry’s own losses were about 15 men killed and 45 wounded.

Meanwhile, 25th Division patrols had learned that the Japanese held Umingan, on Route 8 five miles northwest of Lupao, in some strength. On 30 January the 27th Infantry started moving into position to strike the town from the north and northwest, while the 35th Infantry began preparing a holding attack from the west and southwest. To cover these preparations, the 25th Reconnaissance Troop patrolled toward Lupao and other towns along Route 8 between

Wrecked Japanese tank-artillery column, near Pemienta

Umigan and San Jose. The troop made scattered contacts with many small groups of Japanese in the region west of the highway and south of Umingan, indicating that the Japanese had a counter-reconnaissance screen in the 25th Division’s sector as well as in the 6th Division’s area.

Although the 25th Division had not reached Lupao, the advances made by I Corps’ two right flank divisions through 30 January were of considerable importance to future Sixth Army planning. First, by severing Route 5, the 6th Division had forced the Shobu-Shimbu Group line of communications eastward to poor roads in the foothills of the Sierra Madre beyond the main highway. Even these routes would be denied the Japanese once I Corps could secure Cabanatuan and San Jose. Then, by the end of January, I Corps had gathered sufficient information from patrols, captured documents, Filipino guerrillas, prisoners of war, and aerial reconnaissance for Sixth Army to conclude that strong elements of the 2nd Tank Division were concentrated in the triangle formed by San Jose, Muñoz, and Lupao. General Krueger also had reason to believe that the 10th Division had considerable strength at or near San Jose. The 6th Division’s unopposed advances to 30 January, and its discovery that there were no Japanese west of Route 5 in the region south of Licab and Talavera, indicated to Krueger that the dangers to the XIV Corps’ left rear were not as great as he had previously feared. On the other hand, he was unwilling to discount entirely the threat presented by the 2nd Tank Division and 10th Division concentrations in the San Jose-Muñoz-Lupao area. His interpretation of available

intelligence did not lead him to believe that the Japanese forces in the area had only defensive intentions, and he therefore felt the two Japanese units had an offensive potential he could not ignore. I Corps, Krueger decided, would have to make long strides toward overcoming the threat from the San Jose-Muñoz-Lupao triangle before the XIV Corps’ advance to Manila could proceed unchecked.6

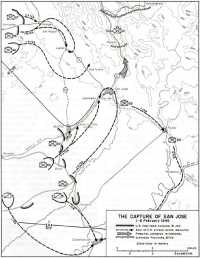

Accordingly, on 30 January, General Krueger directed I Corps to drive eastward in order to seize San Jose and secure a line extending from that town to Cabanatuan and Rizal, respectively twenty miles south and ten miles southeast of San Jose. (Map 5) Once on this line, I Corps would reconnoiter to Luzon’s east coast at Baler and Dingalen Bays. Krueger also changed the I-XIV Corps boundary from the earlier north-south line through the Central Plains, turned the line east of Licab, passed it north of Cabanatuan, and swung it thence southeast to Dingalen Bay.7

The Capture of San Jose

Japanese and American Tactical Plans

General Yamashita was vitally interested in the defense of San Jose for reasons that, as of 30 January, were of secondary importance to General Krueger. Krueger knew that with the successful accomplishment of its mission I Corps would have cut the last overland links between the Shimbu and Shobu Groups and would have gained a good base of attack against the Shobu Group concentration in northern Luzon, but Krueger’s main interest was the protection of XIV Corps’ left rear. Yamashita, on the other hand, intended to hold San Jose and its approaches until he could move all the supplies stockpiled there north into the mountains along Route 5 and until the 105th Division could pass through the town on its way north from the Shimbu Group to join the Shobu Group. Yamashita estimated that his troops could move the bulk of the supplies – mainly ammunition – still at San Jose out of town by the end of the first week in February, and he hoped that the last elements of the 105th Division would have cleared San Jose by the same time.8

Thus Yamashita viewed the defense of San Jose as a holding action of limited duration. Yet the course of future operations in northern Luzon would be determined in large measure by the nature of the defensive stand of the 2nd Tank Division and attached elements of the 10th and 105th Divisions. Upon that defense depended the quantity of supplies the Japanese could move out of San Jose and environs before losing that railhead, the strength the 2nd Tank Division would have left, and the size and composition of the forces the 105th Division could move through the town before it fell. Manifestly, if I Corps could capture San Jose quickly, Sixth Army’s ultimate task in northern Luzon would be much easier.

Map 5: The Capture of San Jose, 1-8 February 1945

The Japanese forces at and in front of San Jose were deployed in scattered detachments in an attempt to provide a defense in depth. Yamashita had intended that defenses would be concentrated at Lupao and Muñoz, but instead the 2nd Tank Division had split its available forces – including the attachments from the 10th and 105th Divisions – among eight separate strongpoints. At Umingan, for example, the garrison was built around the 3rd Battalion, 26th Independent Mixed Regiment, one of the five infantry battalions that the 105th Division had started north from the Shimbu area.9 The battalion was reinforced by a rifle company that the 10th Division had left behind as it withdrew up Route 5.

Lupao was held by a tank company each of the 7th and 10th Tank Regiments, two companies of the 2nd Mobile Infantry, a three-gun (75-mm.) artillery platoon, and 2nd Tank Division engineer and ordnance troops. San Isidro, on Route 8 midway between Lupao and San Jose, was garrisoned by the 10th Tank Regiment, less one company. The 2nd Tank Division’s headquarters, along with minor engineer and infantry units, was located on Route 5 two miles north of San Jose. A bit further north, in sharply rising ground east of the highway, there was another groupment composed of two 75-mm. batteries, two infantry companies, and a tank company.

The Ida Detachment defended Muñoz. Numbering nearly 2,000 men, this combat command included the 6th Tank Regiment, less one company; the bulk of the 356th Independent Infantry Battalion, 103rd Division;10 a battery of 105-mm. howitzers from the 2nd Mobile Artillery; and elements of the 2nd Tank Division’s Antitank Unit, which were armed with 47-mm. guns. At an agricultural school on Route 5 about a mile and a half northeast of Muñoz was a small force of infantry and antitank guns; a similar groupment held barrios Caanawan and Abar No. 2, on Route 5 two miles southwest of San Jose. Rizal was garrisoned by a company each of tanks, infantry, and antitank guns, reinforced by two or three 75-mm. weapons. There was no permanent garrison in San Jose itself, which had long been a prime target for Allied Air Force planes.

The Japanese made little provision to defend the fairly open ground adjacent to Routes 5 and 8 on the way to San Jose. They made no attempt, either, to block Route 99, a third-class road that connected Lupao and Muñoz. They had, in brief, no plan to forestall American flanking maneuvers against the isolated individual strongpoints.

All defenses were fixed. Most of the available tanks were dug in as pillboxes, and the Japanese had no plans for their withdrawal. After the war, 14th Area Army and 2nd Tank Division officers offered

many explanations for the unorthodox, static use of the armor, citing fuel shortages, Allied air superiority, terrain difficulties, and the light armament and armor of the Japanese tanks as compared to the American. No doubt all these explanations have some validity, but they also reveal that Yamashita was willing to sacrifice the 2nd Tank Division, which he would have found difficult to employ in a more normal role, in the static defense of the approaches to San Jose. He had obviously determined that the approaches would be held, whatever the cost, until the 105th Division and the ammunition stockpiled at San Jose had moved north up Route 5.

I Corps plan for the attack on San Jose was simplicity itself, as is the nature of most good plans. General Swift, the corps commander, decided upon a pincers movement. The 6th Division, to make the main effort, would attack northeast up Route 5 through Muñoz; the 25th Division would support with a drive southeast along Route 8 through Umingan and Lupao. General Swift reinforced each division for the attack. To the 25th Division he attached a 155-mm. gun battalion, an 8-inch howitzer battalion, a 4.2-inch mortar company, and a company of medium tanks. The 6th Division’s reinforcements included a 155-mm. howitzer battalion, two 105-mm. howitzer battalions, a 4.2-inch mortar company, a company of medium tanks, and two platoons of light tanks. The 6th Division would provide its own protection on its right and right rear; the 25th Division’s left rear would be protected by the 32nd Division, which had started to move into the line between the 25th and 43rd Divisions. The 43rd Division and the 158th RCT would hold the ground they had secured in the Damortis-Rosario sector.11

The Attack Begins

The drive toward San Jose began on the morning of 1 February as the 20th Infantry, 6th Division, gathered for an assault on Muñoz and the 27th Infantry, 25th Division, struck toward Umingan.12 The ground around Muñoz, flat and open, provided neither cover nor concealment for the attackers, and was broken only by a few drainage or irrigation ditches within the town and by a gentle draw opening westward from the town’s center. A few, small, scattered trees afforded the only shade in the vicinity – heat from the broiling tropical sun would become a problem for the 20th Infantry. Few houses within the town were still intact, for American air and artillery bombardment had already made a shambles of most buildings.

Japanese medium tanks, mounting 47-mm. weapons and machine guns, formed the backbone of the defense. Most of the tanks were dug in with turrets barely showing above ground. Artillery and 47-mm. antitank guns were in sand-bagged or earthen-walled emplacements that only a direct hit by American mortars or high-angle artillery fire could knock out. Japanese infantry and machine gunners held strongpoints throughout the Muñoz debris, which also provided camouflage for many artillery and tank positions.

Muñoz

On 1 February the 3rd Battalion, 20th Infantry, led the attack with an attempt to gain control of a 2,000-yard stretch of Route 99 along the western edge of Muñoz. After fifteen minutes’ preparation by a battalion of 105-mm. howitzers and two platoons of 4.2-inch mortars, the infantry struck from the southwest at 0800. About 1130, when the leading troops were still 500 yards short of Route 99, Japanese tank and artillery fire from the southern end of Muñoz stalled the attack. The 1st Battalion then came up on the right, but was able only to clear a few Japanese from a cemetery stretching along Route 5 and the Manila Railroad at the southeastern corner of town.

The 2nd of February was essentially a repetition of the 1st, and again the 20th Infantry made only slight gains. General Patrick, the 6th Division’s commander, began to lose patience. He was already dissatisfied with the 20th Infantry’s earlier performance in the Cabaruan Hills and was increasingly disturbed by what he felt was inordinately slow progress at Muñoz. He thereupon relieved the 20th’s commander, Colonel Ives, an action he later came to regret,

and replaced Ives with Lt. Col. Harold G. Maison.13

On 3 February the 2nd Battalion, 20th Infantry, moved in on the northwest, but could not reach Route 99 in its sector. The 3rd Battalion pushed across that road at the southwest corner of Muñoz, but gained only half a block into the main section of the town. The 1st Battalion, on the south side of Muñoz, made negligible progress. By dusk, the 20th Infantry had overrun a few Japanese strongpoints, but in order to hold its gains had had to destroy completely and physically occupy every position it had reached so far. Muñoz, General Patrick had begun to realize, was going to be a costly, hard, and time-consuming nut to crack. The 20th Infantry had not yet closed with the main Japanese defenses, but had spent most of the last three days pinned down by Japanese artillery, tank, and machine gun fire. Only by hugging the ground and taking advantage of the little cover even shattered tree stumps afforded had the regiment kept its casualties down to 15 men killed and 90 wounded.

The 6th Division, bogged down at Muñoz, could take some wry consolation from the fact that the 25th Division had made no better progress at Umingan, where the cover and concealment problems were much the same as at Muñoz.14 On 1 February the 25th’s 27th Infantry attacked from the north and west. Under cover of artillery and air support, troops operating along Route 8 advanced to within 250 yards of Umingan’s western edge, but Japanese machine gun and rifle fire then pinned them down. Japanese antitank weapons drove off American tanks that came up Route 8 to support the infantry, while irrigation ditches on both sides of the road prevented the tanks from executing cross-country maneuvers. The infantry sought what cover it could find in these and other irrigation ditches, and, since many of the ditches were charged with noisome excrement that flowed sluggishly through dry rice paddies, spent a thoroughly unpleasant afternoon. Meanwhile, elements of the 27th Infantry attacking from the north had also spent most of the day seeking cover from Japanese fire. Toward dusk these troops had advanced only as far as an almost-dry creek bed 500 yards north of Umingan. As night fell one company employed another creek bed to push into the northwestern corner of the town, but after that the attack stalled completely.

During the course of the day General Mullins, the 25th Division’s commander,

had decided to employ part of the 35th Infantry to bypass Umingan to the south. Moving cross-country along one-lane dirt roads, a battalion of the 35th, encountering no opposition, occupied San Roque barrio, on Route 8 nearly four miles southeast of Umingan and a little over a mile north of Lupao. Another battalion of the 35th Infantry had held during the day in open ground south of Umingan, but early on the 2nd drove up a third-class road against the southeastern corner of the town. Mullins had already directed the 35th Infantry to use its remaining battalion in an attack west into Umingan along Route 8.15

The 35th’s two battalions did not meet expected resistance on 2 February, for during the night most of the Japanese infantry had withdrawn northeast from Umingan into the grassy foothills of the Caraballo Mountains. By 1300 on the 2nd, the 35th Infantry had cleared most of Umingan, leaving two final pockets for the 27th Infantry to reduce the next day. When a summation was made at dusk on the 3rd, the 35th Infantry’s casualties in the reduction of Umingan were 3 men killed and 13 wounded, while the 27th Infantry had lost nearly 40 men killed and 130 wounded. The Japanese, who lost about 150 killed, left behind eight 47-mm. antitank guns along with large quantities of 47-mm. and 75-mm. ammunition.

The capture of Umingan had taken a day longer than General Mullins had anticipated, casualties had been high compared to those of the Japanese, and the main body of the Japanese had escaped to fight again. Hoping to make up the time lost, Mullins pushed the 35th Infantry on toward Lupao during the afternoon of 2 February, hardly giving the regiment time to regroup after its operations at Umingan.16 The regiment estimated that a company of Japanese infantry, reinforced by fifteen to twenty medium tanks, held Lupao. If so, the regiment felt, it would need only one reinforced battalion to capture the town, and it expected to clear the objective by 1800 on the 2nd.17

The 1st Battalion, 35th Infantry, leading the advance on Lupao, met no resistance during the afternoon of 2 February until its lead company was within 750 yards of town. Then, Japanese artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire stopped the attack cold. Attempts to outflank the defenses across the open ground of dry rice paddies that surrounded the town proved unavailing, and at dusk the battalion withdrew 500 yards westward to allow supporting artillery and mortars to lay concentrations into the town. Resuming frontal attacks the next morning, the 35th Infantry, still trying to advance across open ground, again made no significant progress. Like the 20th Infantry in front of Muñoz, the 35th Infantry had been stopped at Lupao.

Outflanking Maneuvers

By late afternoon of 3 February, General Patrick and General Mullins faced nearly identical situations. Stalled in front of intermediate objectives, the two division commanders had to devise some means of bypassing and containing the Japanese strongpoints at Lupao and

Muñoz while pressing the attack toward San Jose. General Patrick, although he had not expected the delay at Muñoz, had forehandedly directed the 1st Infantry to reconnoiter six miles east of Muñoz to the Talavera River with a view toward locating an overland approach to the San Jose-Rizal road at the point where that road crossed the Talavera three miles southeast of San Jose. Here, he had reasoned, the 1st Infantry might assemble for an attack toward San Jose, if necessary, to support the 20th Infantry’s drive up Route 5. Orders to the 1st Infantry to move to the Talavera crossing went out during the late afternoon of 1 February. Simultaneously, Patrick directed his 63rd Infantry to bypass Muñoz to the east and come back onto Route 5 north of the town, ready to drive on San Jose in concert with the 1st Infantry.18

General Mullins made somewhat similar arrangements to bypass Lupao. Temporarily leaving the 27th Infantry at Umingan and assigning the task of clearing Lupao to the 35th Infantry, Mullins directed the 161st Infantry to move cross-country to positions on Route 99 south of Lupao and then push on to Route 8 between San Isidro, four miles southeast of Lupao, and San Jose. The regiment would patrol toward San Jose in preparation, if the need arose, for helping the 6th Division secure that town. The 35th Infantry, in addition to capturing Lupao, would cut Route 8 between Lupao and San Isidro with a force of sufficient strength to prevent Japanese movements between the two towns, both now known to be held in some strength.19

The 3rd Battalion, 35th Infantry, moving over rising ground northeast of Lupao, established itself on Route 8 about 1,500 yards southeast of the town during the afternoon of 3 February. The next day the battalion forced its way into the southern edge of Lupao against heavy opposition, but 35th Infantry troops north and west of the town made no progress. Meanwhile, the 161st Infantry had started moving and by midafternoon on 4 February had set up roadblocks on Route 8 southeast of San Isidro. The regiment was ready to attack toward either San Isidro or San Jose, but progress made by the 35th Infantry, to the northwest, and the 6th Division, to the southeast, made further advances unnecessary for the time being.20

The 6th Division’s flanking operations began shortly after 1700 on 1 February when elements of the 1st Infantry started north along the west bank of the Talavera River. The regiment secured the Talavera crossing on the San Jose-Rizal road during the late afternoon of 2 February after a sharp skirmish with a small Japanese infantry-tank force. Meanwhile, other troops of the 1st Infantry

came up from the southeast and, bypassing Rizal to the west, turned northwest along the San Jose-Rizal road. These troops encountered only scattered opposition. By late afternoon on 3 February most of the 1st Infantry had assembled at two positions 1,000 yards south and 1,500 yards east of San Jose.21

The 63rd Infantry, also bypassing Muñoz to the east, reached the agricultural school on Route 5 a mile and a half northeast of Muñoz on the afternoon of 2 February. Leaving a reinforced company to clean out the Japanese tank-infantry groupment at the school, the bulk of the regiment pressed on up Route 5 during the next afternoon and by dusk, having encountered little opposition, was within sight of barrios Caanawan and Abar No. 2, two miles short of San Jose.22 The situation seemed to favor a two-regiment attack against San Jose on the 4th, and at 2000 on the 3rd General Patrick ordered the execution of such an attack.23

The Seizure of San Jose

The prospect of an all-out battle at San Jose turned out to be a chimera. Indeed, after the costly fighting at Lupao and Muñoz and exhausting night marches entailed in the 6th and 25th Divisions’ flanking maneuvers, the actual capture of the objective came as a pleasant anticlimax. Held up by the Japanese tank-infantry groupment in the vicinity of Abar No. 2, the 63rd Infantry took no part in the seizure of San Jose, but two companies of the 1st Infantry walked into San Jose virtually unopposed during the morning of 4 February. By 1330 the regiment had secured the objective at a cost to the 1st Infantry of 2 men killed and 25 wounded, including 1 killed and 7 wounded when Fifth Air Force B-25’s made an unscheduled strafing run across the regimental front.24

The seizure of San Jose turned out to be anticlimactic for at least two other reasons. Two days before the town fell, I Corps’ progress as far as Lupao and Muñoz, disclosing that the Japanese had committed their forces to a piecemeal, passive defense of the approaches to San Jose, had dispelled General Krueger’s remaining anxieties about counterattack from the east and the security of the XIV Corps’ left rear. The Japanese, having failed to organize a strong, mobile striking force from their available armor, had themselves removed the last vestiges of threat from the east and northeast to Sixth Army and XIV Corps.

Accordingly, on the evening of 2 February, Krueger had directed XIV Corps to resume its drive to Manila with all speed. I Corps would proceed with its mission to secure the Cabanatuan-Rizal line and reconnoiter to Luzon’s east coast, but henceforth, however heavy the actual fighting in the San Jose region, I Corps operations would evolve into mopping-up actions and would be partially aimed at securing lines of departure from which future attacks could be launched against the Shobu Group in northern Luzon.25

From one point of view, the Japanese themselves had produced the final anticlimax for the I Corps at San Jose. By 4 February the bulk of the forces the 105th Division that had so far been able to start northward from the Shimbu area had slipped through San Jose and were well on their way up Route 5 north of the town. The Tsuda Detachment, attached to the 10th Division, had by the same date evacuated its now unimportant defensive positions at Baler and Dingalen Bays and had withdrawn to Rizal. On or about the 4th, the detachment had started out of Rizal along a third-class road that led north into the mountains. Finally, the last of the supplies of the Shobu Group needed the most for its planned protracted stand in northern Luzon had been removed from San Jose during the night of 3-4 February. Since there was no longer any reason for him to hold the town General Yamashita, sometime on the 4th, directed the elements of the 2nd Tank Division (and its attachments) still holding defenses forward of San Jose to break contact and retreat up Route 5.

That I Corps had been unable to prevent the evacuation of supplies from San Jose, the displacement of the 105th Division’s troops, or the withdrawal of the Tsuda Detachment was unfortunate, but these tasks had not been among those Krueger had assigned the corps. As it was, I Corps had probably accomplished more than had been expected of it when it cut off the main body of the 2nd Tank Division in front of San Jose. The corps could now reduce the division’s isolated strongpoints at its leisure, could push its troops rapidly to the east coast to break the last overland connections between the Shimbu and Shobu Groups, and could secure positions from which to launch attacks against the Shobu Group when so directed.

Mop-up on the Approaches to San Jose

Such was the state of Japanese communications in the San Jose area that Yamashita’s orders for a general withdrawal did not reach 2nd Tank Division’s units south and west of San Jose until 6 February.26 In the meantime, the Lupao and Muñoz garrisons continued to hold out, thwarting the best efforts of the 6th and 25th Divisions to dislodge them.

By 4 February the 20th Infantry attack against Muñoz had evolved into a siege.27 During that day and on through the 6th, the regiment’s pressure produced minor gains, but the more the Japanese force was compressed the more difficult became the 20th Infantry’s task. By evening on the 6th, the 20th Infantry and its supporting forces had knocked out nearly thirty-five tanks at Muñoz, along with a few antitank guns and a number of machine guns. The Japanese still had twenty to twenty-five tanks, they still held half the town, and they still had over half of their original garrison. The 20th Infantry had so far lost 40 men killed and 175 wounded, while many

others had dropped of heat exhaustion and combat fatigue. It was clear to General Patrick that something beyond the direct assault methods employed so far would have to be tried if the 6th Division was to clear Muñoz within a reasonable time and with reasonable casualties.

A large part of 7 February, Patrick planned, would be spent pounding Muñoz with air and artillery. First, about fifty planes of the Fifth Air Force were to bomb and strafe, climaxing their effort with a napalm saturation. Then division artillery and reinforcing corps artillery battalions would thoroughly plaster the town. Finally, the ground troops would resume the assault about midafternoon behind a rolling barrage laid down by the 6th Division’s three 105-mm. howitzer battalions. The 63rd Infantry, relieved by the 1st Infantry just south of San Jose, would redeploy to the south side of Muñoz to join the final attack of the 20th Infantry.

The Japanese did not cooperate. Under cover of a minor diversionary attack against the 20th Infantry’s lines, the main body of the Ida Detachment attempted to escape up Route 5 during the predawn hours of 7 February, apparently not realizing that the road from Muñoz north to San Jose was in American hands. Running a gauntlet of roadblocks held by the 63rd Infantry, the 53rd and 80th Field Artillery Battalions, and the 2nd Battalion, 161st Infantry (which had moved down to the agricultural school from the San Isidro area prepared to reinforce the 6th Division for the attack on Muñoz), the Japanese escape column was destroyed. After daylight on the 7th the 20th Infantry moved into Muñoz almost unopposed, clearing the last resistance by noon.

The defense of Muñoz and Route 5 north to San Jose cost the 2nd Tank Division 52 tanks, 41 trucks, 16 47-mm. guns, and 4 105-mm. howitzers destroyed and 1,500 men killed. In securing the same area, the 6th Division lost 90 men killed and nearly 250 wounded, exclusive of the casualties incurred by the 1st Infantry in and around San Jose.

At Lupao, meanwhile, the battle had developed along lines similar to those at Muñoz. From 4 through 7 February the 35th Infantry, placing the emphasis of its attack against the south side of Lupao, continued to compress the garrison into a smaller and smaller space. The Japanese made a breakout attempt the night after the Ida Detachment’s flight from Muñoz. Ten or eleven tanks started out of Lupao; five of them managed to break through the 35th Infantry’s cordon and disappeared into the foothills east of town, where their crews abandoned them. The dismounted Japanese in the town melted away, and by noon on the 8th the 35th Infantry had secured Lupao against negligible opposition. The 2nd Tank Division’s losses there included over 900 troops killed and 33 tanks, 26 trucks, and 3 75-mm. guns destroyed or abandoned. The 35th Infantry and attached units lost about 95 men killed and 270 wounded.28

The Japanese garrison at San Isidro fled before the 161st Infantry could mount an attack, taking to the hills during the night of 5-6 February. The 161st occupied the town against scattered

rifle fire on the 6th, and for the next few days sought out Japanese stragglers in rising ground to the northwest, north, and northeast. The regiment destroyed or found abandoned 23 tanks, 18 trucks, 2 75-mm. artillery pieces, and a miscellany of other equipment and supplies. A hundred or more Japanese died at or near San Isidro, while the 161st Infantry lost about 15 men killed and a like number wounded in the vicinity.

The 2nd Tank Division was finished as an armored unit. In the defense of the approaches to San Jose the division had lost 180 of the 220 tanks with which it had entered combat on Luzon. The division’s troop losses – exclusive of the losses of attached units – numbered nearly 2,250 men killed of the 6,500 the unit had committed to the defense of San Jose. The survivors were either already on their way up Route 5, or slowly filtered through I Corps lines and made their way northward. Reorganized as an understrength infantry division, the 2nd Tank Division would fight again, but Japanese armor would no longer be a factor with which Sixth Army would have to reckon on Luzon.29

San Jose to the East Coast

After the seizure of San Jose and the destruction of the 2nd Tank Division as an armored force, I Corps, to finish the tasks assigned it by General Krueger, still had to move in strength up to the Cabanatuan-Rizal line and reconnoiter to Baler and Dingalen Bays on the east coast. The corps assigned these tasks to the 6th Division, which wasted no time undertaking them after the fall of Muñoz.30

The 63rd Infantry, on 7 February, captured Rizal against scattered opposition from Tsuda Detachment stragglers.31 The next day the 20th Infantry, encountering few Japanese, secured Bongabon, six miles south of Rizal, and cleared the road from Rizal through Bongabon to Cabanatuan. A combined 20th Infantry-6th Reconnaissance Troop patrol next pushed over the hills from Bongabon to Dingalen Bay along a poor gravel road and reached the bay on 11 February. The following day a 63rd Infantry-6th Reconnaissance Troop patrol, following another road out of Bongabon, reached Baler Bay. The patrols found only abandoned defenses at each objective and left the security of the bay’s shores and the roads back to Bongabon to Filipino guerrillas.

In the meantime, the 25th Division had taken over from the 6th Division at San Jose and had begun patrolling both northward up Route 5 and southeastward along the road to Rizal. The two divisions continued patrolling in the areas they held until, on 10 February, I Corps began realigning forces for operations against the Shobu Group in northern

Luzon. Before such operations could start, more urgent battles to the south had to be brought to successful conclusions, and the I Corps’ right flank units, for the time being, would hold the positions they had already attained while preparing for stiff fights they knew were in the offing.

The Destruction of the Kembu Group

Sixty miles southwest across the Central Plains from San Jose the 40th Division, fighting against the Kembu Group, took about a week longer to secure Sixth Army’s right and XIV Corps’ right rear to Krueger’s and Griswold’s satisfaction than I Corps had taken on the left. In the Kembu area, the terrain did not permit the relatively free maneuver I Corps had employed to capture San Jose. Rather, the fight at the Kembu positions continued to be a slug fest against a well-entrenched Japanese force holding rugged, dominating ground. Progress each day was often measured in terms of feet.

The Situation at Clark Field

By 1 February, when the XIV Corps started the 37th Division south toward Manila, the 37th and 40th Divisions had overrun the Kembu Group OPLR both north and south of the Bamban River. (See Map IV.) South of the stream the 129th Infantry, 37th Division, had breached the Japanese MLR at Top of the World Hill, just west of Fort Stotsenburg. West and southwest Top of the World remnants of the Eguchi and Yanagimoto Detachments, combined into a single force, held out in rough ground in front of the “last-stand” positions occupied by the Kembu Group’s naval units.

North of the Bamban the 160th Infantry, 40th Division, had pushed into the Takaya Detachment MLR positions. The regiment’s left was on high ground overlooking the river, its right and center on a 1,000-foot-high, ill-defined hill mass known as Storm King Mountain. Elements of the Takaya Detachment still maintained MLR defenses on the west side of Storm King. Although, further north, the 108th Infantry had not yet closed with the Takayama Detachment MLR, the breach the 160th Infantry had effected along the MLR’s center and right had made untenable the Japanese unit’s hold. The Takayama Detachment was faced with the choice of fighting to death in place or making an orderly withdrawal into the naval last-stand positions.

The naval defenses were composed of five combat sectors, numbered 13 through 17. The 16th Combat Sector centered on high ground two miles west-northwest of Top of the World and athwart the upper reaches of the Bamban River; the 17th lay another mile or so to the west. The 15th Combat Sector was north across a branch of the Bamban from the 16th and nearly two miles beyond the 160th Infantry’s penetration at Storm King Mountain. The 14th and 13th Combat Sectors, reading east to west, were northwest of the 15th. Each combat sector held dominating ground protected on at least two sides by sharp ravines; each varied as to area and strength.

General Tsukada, commanding the Kembu Group, still had some 25,000 men under his control. He was prepared to offer protracted resistance, although his communications were poor and, with

all chance of resupply long gone, his food and ammunition could not last forever. But he was firmly ensconced in easily defensible terrain, his defense plan was well conceived, and the bulk of his positions were mutually supporting. To overrun any strongpoint the 40th Division would have to make careful plans for the closest coordination of air, artillery, and armor. Once the approaches to an objective were cleared, the Japanese defenders would have to be flushed out of hidden foxholes, caves, and bunkers. To take any piece of dominating terrain the Americans would have to destroy a series of mutually supporting strongpoints. The whole process would be difficult, costly, time consuming, and repetitive but, in General Krueger’s opinion, would be necessary in order to secure the right rear of XIV Corps and push the Kembu Group so far back into the Zambales Mountains that it would be incapable of threatening Clark Field.

The 40th Division spent the first week of February realigning its forces, mopping up areas already secured, and patrolling to find good routes of approach to strongpoints located by ground and aerial observation. The 185th Infantry rejoined the division and replaced the 108th in the north; it took over the 129th Infantry’s positions on Top of the World on 2 February.32

It is not known when General Brush, the division commander, intended to start a general offensive westward, but if he had any idea of waiting beyond the first week in February he was undoubtedly brought up short on the 6th. That day General Krueger instructed XIV Corps to have the 40th Division “proceed more expeditiously with the destruction” of the Kembu Group, not only for the reasons of which the corps was already well aware but also because the division would soon have to be relieved for operations elsewhere.33 Griswold relayed these instructions to Brush without delay.

Brush’s plan for attack called for the 185th and 160th Infantry Regiments to drive against the Japanese center while the 108th Infantry continued the advance against the Japanese right where the 129th Infantry had left off. The division’s objective was high ground lying about seven miles west of Route 3 and extending almost an equal distance north to south.34 Once this terrain had been cleared, the 40th Division would have overrun the entire Kembu MLR and would be poised in front of the naval last-stand positions.

Turning the Kembu Flanks

Before the divisional attack began, the 160th Infantry, mopping up at Storm King Mountain, became involved in a fight that turned into preparation for the regiment’s part in the main offensive.35 The fight focused at McSevney Point, a ridge 300 yards long and 75 yards wide forming a western nose of

Storm King. Here an infantry company of the Takaya Detachment, reinforced by one 70-mm. howitzer, three 90-mm. mortars, ten 50-mm. grenade dischargers, and 27 machine guns of various calibers, blocked the 160th Infantry’s path.36 The Japanese force was holed up in caves, bunkers, and foxholes, all well concealed by natural camouflage.

The 160th Infantry’s first attack against McSevney Point took place on 6 February, and behind the close support of tanks, tank destroyers, and Fifth Air Force planes, the regiment cleared most of the point by dusk on the 8th. During the ensuing night the Japanese launched a series of banzai-type counterattacks, and it was nearly noon on the 9th before the 160th Infantry had repulsed the final Japanese assault. The next morning, 10 February, the regiment discovered that the last Japanese had withdrawn during the night. The affray cost the 160th Infantry about 20 men killed and 125 wounded, while the Japanese lost around 225 men killed.

Although the fight at McSevney Point at first appeared to have delayed the 160th Infantry’s participation in the division attack – scheduled to begin on the 8th – the action turned out quite well for the 40th Division. First, the capture of McSevney Point removed a major obstacle at the division’s center. Second, the loss of the point prompted General Tsukada to direct the Takaya Detachment to abandon its portion of the MLR and fall back to the last-stand positions. The withdrawal split the Kembu MLR, and the 40th Division could press on into a gap between the Takayama Detachment, on the north, and the combined Eguchi-Yanagimoto Detachment force on the south. The existence of the gap also permitted the 185th and 108th Infantry Regiments to deal in detail with the Kembu Group’s left and right.

On 7 February the 185th Infantry had started an attack against the Takayama MLR, on the Japanese left, its ultimate objective Snake Hill North, a height from which Japanese fire had harassed the 160th Infantry’s right flank units 2,000 yards to the southeast. In three days of stiff fighting through thick undergrowth and over rough, steeply rising terrain, the 185th Infantry gained half the ground to Snake Hill North. The regiment had not yet closed with the Japanese MLR in its zone, and opposition had come principally from mortars, light artillery, and a very few machine guns. The most the 185th Infantry could show for its operations to the morning of 10 February was that it had brought its front line abreast of the 160th’s right.

On the 40th Division left (the Japanese right), the 108th Infantry started westward from Top of the World on 8 February, its first objective a north-south line of knobs lying 1,500 to 2,000 yards west and southwest of the line of departure. The hills were honeycombed with small bunkers and foxholes; riflemen were supported by and in turn protected machine gun emplacements; defensive weapons included many 20-mm. and 25-mm. machine cannon stripped from aircraft at Clark Field; and, at least initially, the defenders boasted a plentiful supply of mortars and mortar ammunition.

From 8 through 12 February the 108th Infantry fought solely to clear approaches to the Japanese hill strongpoints. The advance was daily marked by temporary gains of terrain that the Japanese rendered untenable by heavy weapons fire or by gains along approaches where the American troops spent most of their time pinned down by Japanese fire. The 108th Infantry began to make appreciable progress only after division artillery started to lay support fires dangerously close to the front lines and after Cannon Company SPMs, 640th Tank Destroyer Battalion TD’s, and 754th Tank Battalion mediums laboriously rumbled forward over rough ground to place direct fire on Japanese emplacements.

By evening on 12 February the Eguchi-Yanagimoto Detachment, having lost over 500 men killed since the 8th, was finished as an effective fighting unit and held only one position along the Kembu Group’s right flank. Hill 7, as the position was designated, lay three-quarters of a mile westward of the group of knobs that the 108th Infantry had cleared by the 12th. It took the 108th Infantry until afternoon of the 16th to clear this last hill. The regiment had now turned the right of the Kembu MLR, and the shattered remnants of the Eguchi-Yanagimoto Detachment retreated into the last-stand positions.

By the time the 108th Infantry had turned the right flank, the 185th Infantry had already pushed in the Japanese left, and in the center the 160th Infantry had advanced into the naval last-stand area. Between 10 and 12 February the 185th Infantry had secured Snake Hill North against negligible opposition, simultaneously taking Hill 810, a little over two miles to the northeast, and Hill 1000, a mile west of Hill 810. With these gains, almost the last positions along the left of the Kembu MLR had fallen. Continuing forward, the 185th Infantry struck toward Hill 1500, located at the northwestern corner of the 14th Combat Sector area and over a mile southwest of Snake Hill North. The 185th captured Hill 1500 on the 15th, an event that, with the 108th Infantry’s seizure of Hill 7 the next day, marked the end of the Kembu Group MLR. The two American regiments engaged on the flanks had lost approximately 75 men killed and 290 wounded; the infantry alone accounted for 680 Japanese killed during the flank attacks.

The Fight in the Center

While the 108th and 185th Infantry Regiments had been turning the flanks of the Kembu MLR, the 160th Infantry had driven forward in the center, starting its attack on 10 February from a line of departure at McSevney Point.37 The 160th’s initial objectives were Snake Hill West, Scattered Trees Ridge, and Object Hill. The first, grass covered and about 1,500 feet high, lay a little short of a mile west-southwest of McSevney Point and at the northern apex of the triangularly shaped 15th Combat Sector defense area. Scattered Trees Ridge formed the base of the triangle and ran along the north bank of a Bamban River tributary. Object Hill, marking the western limits of the 15th Combat Sector area, lay

about 1,500 yards southwest of Snake Hill West. South of the Bamban tributary, and between the branch stream and the main course of the river, lay Sacobia Ridge, along which the 16th Combat Sector was dug in.

By dusk on 10 February the 160th Infantry’s two forward battalions were well up the eastern slopes of Snake Hill West and Scattered Trees Ridge but were separated by nearly a mile of Japanese-controlled terrain. Even with the close support of tanks, TD’s, and SPMs the regiment did not clear all Snake Hill West until 15 February, although the open crest of the hill fell on the 12th. The battalion on Snake Hill West then turned southwest toward Object Hill, and, Scattered Trees Ridge having proved an unprofitable route of advance, troops on that ridge struck northwestward toward Object Hill in a converging attack. Elements of the 160th Infantry reached the crest of Object Hill on 16 February, but the regiment took until the 20th to clear the last Japanese strongpoints from the hill and its approaches. By that time the 15th Combat Sector’s right, along Scattered Trees Ridge, had also collapsed, and American infantry had gained a foothold on Sacobia Ridge in the 16th Combat Sector area.

The 160th Infantry’s drive into the center of the naval last-stand positions at Object Hill completed another phase of the fight with the Kembu Group. As of 20 February, the group’s MLR no longer existed; positions on the left of the last-stand defenses, the 14th Combat Sector area, had fallen to the 185th Infantry; the 160th Infantry, attacking into the 15th and 16th Combat Sectors defenses, was well across the center of the last-stand positions. The 160th Infantry’s gains in the center, including the earlier fight at McSevney Point, had cost the regiment roughly 75 men killed and 330 wounded, while heat exhaustion and combat fatigue took an increasingly heavy toll. The regiment’s 1st Battalion had less than 400 effectives and the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were both some 300 men understrength.

Whatever the costs, the 40th Division’s advances to the 20th of February marked the end of the Kembu Group as a threat to Sixth Army and XIV Corps. Clark Field, Route 3, and the army and corps right were now secure beyond all shadow of doubt. The Kembu Group had defended its ground well since 24 January, when XIV Corps had first gained contact, and had inflicted nearly 1,500 casualties upon XIV Corps units – roughly 285 men killed and 1,180 wounded – but had itself lost around 10,000 men killed. The 20,000 troops General Tsukada still commanded were hardly in good shape. Supplies of all kinds were dwindling rapidly, morale was cracking, centralized control was breaking down. The only defenses still intact were those held by the naval 13th and 17th Combat Sectors, and those had been heavily damaged by air and artillery bombardments. Troops of the Sixth Army would continue to fight the Kembu Group, but after 20 February operations in the Kembu area were essentially mop-ups.

Epilogue

XI Corps, not XIV, would be in charge of the final mop-up operations in the Kembu area. By 20 February XIV Corps had its hands full in and around Manila, and the supervision of the separate battle against the Kembu Group placed an

intolerable administrative and operational burden on the corps headquarters. The XI Corps, on the other hand, had nearly completed its initial missions on Luzon and, commanding only one and one-third divisions when it landed, was able to take on the additional burden of controlling 40th Division operations.38

Under XI Corps direction the 40th Division resumed the offensive on 23 February but was relieved by elements of the 43rd Division between 28 February and 2 March. In its final attacks, the 40th Division overran the last organized resistance in the 13th, 14th, and 16th Combat Sectors, losing another 35 men killed and 150 wounded. By the time the 43rd had relieved the 40th Division, just one organized Japanese position remained, that of the 17th Combat Sector.39

The 43rd Division fought the Kembu Group for only ten days, and by the time it was relieved by elements of the 38th Division, beginning 10 March, it had overrun the 17th Combat Sector and had driven the Japanese back another three to four miles beyond the point at which the 40th Division left off. The 43rd Division lost 70 men killed and 195 wounded in the area, eliminating perhaps 2,000 Japanese.40

The 38th Division – to which the 169th Infantry, 43rd Division, remained attached until 22 March41 – pushed on into the untracked, ill-explored, and worse-mapped wilderness of the central Zambales Range, its progress slowed more by supply problems than Japanese resistance. In early April the division noted that the last vestiges of any controlled defensive effort had disappeared. Unknown to XI Corps General Tsukada, on 6 April, had given up and had ordered his remaining forces to disperse and continue operations, if possible, as guerrillas.42 For the Japanese remnants, it was a case of sauve qui peut. Some tried to escape to Luzon’s west coast, whence 38th Division troops were already patrolling inland; others tried to make their way north through the mountains, only to be cut down by American patrols working southward from Camp O’Donnell. The 38th Division had killed about 8,000 of the scattering Japanese by the time it was relieved by units of the 6th Division on 3 May. The losses of the 38th totaled approximately 100 men killed and 500 wounded.43

The 6th Division, elements of which remained in the Kembu area until 25 June, limited its operations to patrolling

and setting up trail blocks along Japanese routes of escape. Troops of the 38th Division ultimately returned to the region and remained there until the end of the war.44

Insofar as U.S. forces were concerned, the mop-up period under XI Corps control was even more costly than had been the XIV Corps’ offensive period. From 21 February to the end of June the various elements of XI Corps committed to action against the Kembu Group lost approximately 550 men killed and 2,200 wounded. The Kembu Group, during the same period, lost 12,500 killed or dead from starvation and disease. By the end of the war the original 30,000 troops of the Kembu Group were reduced to approximately 1,500 sorry survivors, about 1,000 of them Army personnel. Another 500 had already been taken prisoner.45