Chapter 15: The Drive Toward Intramuros

Iwabuchi Entrapped

Although patently determined at the end of January to defend Manila to the last, Admiral Iwabuchi apparently wavered in his resolution during the week or so following the arrival of the first American troops in the city.1 On the morning of 9 February, two days after the 37th Division began crossing the Pasig, the admiral decided that his position in the Manila area had deteriorated so rapidly and completely that he should devote some attention to evacuating his remaining forces. Accordingly, he moved his headquarters to Fort McKinley, evidently planning to direct a withdrawal from that relatively safe vantage point. This transfer precipitated a series of incidents that vividly illustrates the anomalies of the Japanese command structure in the metropolitan area.

About the same time that Iwabuchi moved to Fort McKinley, the first definite information about the course of the battle in Manila reached General Yokoyama’s Shimbu Group headquarters. The Shimbu commander immediately began planning a counterattack, the multiple aims and complicated preparation of which suggest that Yokoyama had so little information that he could not make up his mind quite what he wanted to, or could, accomplish.

Estimating the strength of the Americans in the Manila area at little more than a regiment, General Yokoyama apparently felt that he had a good opportunity to cut off and isolate the Allied force. Conversely, he was also interested in getting the Manila Naval Defense Force out of the city quickly, either by opening a line of retreat or by having Iwabuchi coordinate a breakthrough effort with a Shimbu Group counterattack, scheduled for the night of 16-17 February. Not knowing how far the situation in Manila had deteriorated – communications were faulty and Admiral Iwabuchi had supplied Yokoyama with little information – Yokoyama at first directed the Manila Naval Defense Force to hold fast. The question of a general withdrawal, he told Iwabuchi, would be held in abeyance pending the outcome of the counterattack.

There is no indication that the Shimbu Group commander intended to reinforce or retake Manila. Rather, his primary interest was to gain time for the Shimbu Group to strengthen its defenses north and northeast of the city and to move more supplies out of the city to its

mountain strongholds, simultaneously creating a good opportunity for the Manila Naval Defense Force to withdraw intact.

Such was the state of communications between Iwabuchi and Yokoyama that Iwabuchi had decided to return to Manila before he received any word of the counterattack plans. When Admiral Iwabuchi left Manila he had placed Colonel Noguchi, the Northern Force commander, in control of all troops remaining within the city limits. Noguchi found it impossible to exercise effective control over the naval elements of his command and asked that a senior naval officer return to the city. Iwabuchi, who now feared that Fort McKinley might fall to the Americans before the defenses within the city, himself felt compelled to return, a step he took on the morning of 11 February.

On or about 13 February, General Yokoyama, having received more information, decided that the situation in Manila was beyond repair, and directed Iwabuchi to return to Fort McKinley and start withdrawing his troops immediately, without awaiting the Shimbu Group counterattack. Two days later General Yamashita, from his Baguio command post 125 miles to the north, stepped into the picture. Censuring General Yokoyama, the 14th Area Army commander first demanded to know why Admiral Iwabuchi had been permitted to return to the city and second directed Yokoyama to get all troops out of Manila immediately.

Not until the morning of 17 February did Iwabuchi receive Yokoyama’s directive of the 13th and Yamashita’s orders of the 15th. By those dates XIV Corps had cut all Japanese routes of withdrawal, a fact that was readily apparent to Admiral Iwabuchi. As a result, he made no attempt to get any troops out of the city under the cover of the Shimbu Group’s counterattack, which was just as well, since that effort was unsuccessful.

Yokoyama had planned to counterattack with two columns. On the north, a force composed of two battalions of the 31st Infantry, 8th Division, and two provisional infantry battalions from the 105th Division was to strike across the Marikina River from the center of the Shimbu Group’s defenses, aiming at Novaliches Dam and Route 3 north of Manila.2 The southern prong, consisting of three provisional infantry battalions of the Kobayashi Force – formerly the Army’s Manila Defense Force – were to drive across the Marikina toward the Balara Water Filters and establish contact with the northern wing in the vicinity of Grace Park.

The 112th Cavalry RCT, which had replaced the 12th Cavalry along the 1st Cavalry Division’s line of communications, broke up the northern wing’s counterattack between 15 and 18 February. In the Novaliches-Novaliches Dam area, and in a series of skirmishes further west and northwest, the 112th Cavalry RCT dispatched some 300 Japanese, losing only 2 men killed and 32 wounded. Un-coordinated from the start, the northern counterattack turned into a shambles, and the northern attack

force withdrew in a disorganized manner before it accomplished anything.

The Kobayashi Force’s effort was turned back on the morning of the 16th, when American artillery caught this southern wing as it attempted to cross the Marikina River. During the next three days all Japanese attacks were piecemeal in nature and were thrown back with little difficulty by the 7th and 8th Cavalry Regiments, operating east and northeast of Manila. By 19 February, when the southern counterattack force also withdrew, the 2nd Cavalry Brigade and support artillery had killed about 650 Japanese in the area west of the Marikina from Novaliches Dam south to the Pasig. The brigade lost about 15 men killed and 50 wounded.

The fact that the counterattack was completely unsuccessful in either cutting the XIV Corps lines of communications or opening a route of withdrawal for the Manila Naval Defense Force does not seem to have greatly concerned or surprised General Yokoyama. He did not have much hope of success from the beginning, and, indeed, his ardor for the venture was undoubtedly dampened by Admiral Iwabuchi’s adamant attitude about making any further attempt to withdraw from the city, an attitude the admiral made amply clear on the morning of the 17th, the very day that the counterattack was to have reached its peak of penetration.

That morning Iwabuchi, truthfully enough, informed Yokoyama that withdrawal of the bulk of his forces from Manila was no longer possible. He went on to say that he still considered the defense of Manila to be of utmost importance and that he could not continue organized operations in the city should he attempt to move his headquarters or any other portion of his forces out. Again on 19 and 21 February Yokoyama directed Iwabuchi to withdraw. Iwabuchi was unmoved, replying that withdrawal would result in quick annihilation of the forces making the attempt, whereas continued resistance within the city would result in heavy losses to the attacking American forces. General Yokoyama suggested that Iwabuchi undertake night withdrawals by infiltrating small groups of men through the American lines. Past experience throughout the Pacific war, the Shimbu Group commander went on, had proven the feasibility of such undertakings. There was no recorded answer to this message, and on 23 February all communication between the Shimbu Group and the Manila Naval Defense Force ceased. Admiral Iwabuchi had made his bed, and he was to die in it.

Meanwhile, the fighting within Manila had raged unabated as XIV Corps compressed the Japanese into an ever decreasing area. Outside, the 11th Airborne Division had cut off the Southern Force’s Abe Battalion on high ground at Mabato Point, on the northwest shore of Laguna de Bay. There, between 14 and 18 February, a battalion-sized guerrilla force under Maj. John D. Vanderpool, a special agent sent to Luzon by GHQ SWPA in October 1944, contained the Japanese unit.3 From 18 through 23 February an 11th Airborne Division task force, composed of three infantry battalions closely supported by artillery, tank destroyers, and Marine Corps SBD’s, besieged the Abe Battalion. In this final

action the Japanese unit lost about 750 men killed; the 11th Airborne Division lost less than 10 men killed and 50 wounded – the burden of the attack had been borne principally by the artillery and air support elements. The Abe Battalion’s final stand made no tactical sense, and at least until 14 February the unit could have escaped northeastward practically unmolested.4

The 4th Naval Battalion, cut off at Fort McKinley when the 5th and 12th Cavalry Regiments pushed to Manila Bay, played the game a bit more shrewdly. From 13 through 19 February elements of the 11th Airborne Division, coming northeast from the Nichols Field area, and troops of the 1st Cavalry Brigade, moving east along the south bank of the Pasig River, cleared all the approaches to Fort McKinley in a series of patrol actions. When, on the 19th, troops of the 11th Airborne and elements of the 1st Cavalry Division completed the occupation of the Fort McKinley area, they found that the bulk of the Japanese had fled. Whether by Iwabuchi’s authority or not, the 4th Naval Battalion, together with remnants of the 3rd Naval Battalion from Nichols Field, had withdrawn eastward toward the Shimbu Group’s main defenses during the night of 17-18 February. Some 300 survivors of the 3rd Naval Battalion thus escaped, while the 4th probably managed to evacuate about 1,000 men of its original strength of nearly 1,400.5

Inside the city, as of 12 February, Admiral Iwabuchi still had under his control his Central Force ( 1st and 2nd Naval Battalions), the Headquarters Sector Unit, the 5th Naval Battalion, the Northern Force’s 3rd Provisional Infantry Battalion and service units, remnants of Colonel Noguchi’s 2nd Provisional Infantry Battalion, and, finally, the many miscellaneous naval “attached units.” The 37th Division had decimated the 1st Naval Battalion at Provisor Island and during the fighting through Paco and Pandacan Districts; the 2nd Provisional Infantry Battalion had lost heavily in action against the 1st Cavalry and 37th Divisions north of the Pasig; the 2nd Naval Battalion, originally holding the extreme southern section of the city, had lost considerable strength to the 1st Cavalry Brigade and the 11th Airborne Division; all the rest of the Japanese units had suffered losses from American artillery and mortar fire. The total strength now available to Iwabuchi within Manila probably numbered no more than 6,000 troops.

Perhaps more serious, from Iwabuchi’s point of view, were the Japanese heavy weapons losses. By 12 February XIV Corps had destroyed almost all his artillery. Carefully laid American artillery and mortar fire was rapidly knocking out his remaining mortars as well as all machine guns except for those emplaced well within fortified buildings. Soon Iwabuchi’s men would be reduced to

fighting principally with light machine guns, rifles, and hand grenades. Even so, they were to demonstrate that they were capable of conducting a most tenacious and fanatic defense.

The Battles at the Strongpoints

A Forecast

After 12 February XIV Corps troops found themselves in a steady war of attrition. Street-to-street, building-to-building, and room-to-room fighting characterized each day’s activity. Progress was sometimes measured only in feet; many days saw no progress at all. The fighting became really “dirty.” The Japanese, looking forward only to death, started committing all sorts of excesses, both against the city itself and against Filipinos unlucky enough to remain under Japanese control. As time went on, Japanese command disintegrated. Then, viciousness became uncontrolled and uncontrollable; horror mounted upon horror. The men of the 37th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division witnessed the rape, sack, pillage, and destruction of a large part of Manila and became reluctant parties to much of the destruction.

Although XIV Corps placed heavy dependence upon artillery, tank, tank destroyer, mortar, and bazooka fire for all advances, cleaning out individual buildings ultimately fell to individual riflemen. To accomplish this work, the infantry brought to fruition a system initiated north of the Pasig River. Small units worked their way from one building to the next, usually trying to secure the roof and top floor first, often by coming through the upper floors of an adjoining structure. Using stairways as axes of advance, lines of supply, and routes of evacuation, troops then began working their way down through the building. For the most part, squads broke up into small assault teams, one holding entrances and perhaps the ground floor – when that was where entrance had been gained – while the other fought through the building. In many cases, where the Japanese blocked stairways and corridors, the American troops found it necessary to chop or blow holes through walls and floors. Under such circumstances, hand grenades, flame throwers, and demolitions usually proved requisites to progress.6

Casualties were seldom high on any one day. For example, on 12 February the 129th Infantry, operating along the south bank of the Pasig in the area near Provisor Island, was held to gains of 150 yards at the cost of 5 men killed and 28 wounded. Low as these casualty figures were for a regimental attack, the attrition – over 90 percent of it occurring among the front-line riflemen – depleted the infantry companies’ effective fighting strength at an alarming rate.

Each infantry and cavalry regiment engaged south of the Pasig found a particular group of buildings to be a focal point of Japanese resistance. While by 12 February XIV Corps knew that the final Japanese stand would be made in Intramuros and the government buildings ringing the Walled City from the east around to the south, progress toward Intramuros would be held up for days as each regiment concentrated its efforts on

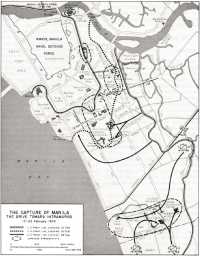

Map 6: The Capture of Manila: The Drive Toward Intramuros, 13-22 February 1945

eliminating the particular strongpoints to its front. There was, of course, fighting practically every step of the way west from Estero de Paco and north from Pasay suburb in addition to the battles at the strongpoints. This other fighting was, however, often without definite pattern – it was laborious, costly, and time consuming, and no single narrative could follow it in detail. It was also usually only incidental to the battles taking place at the more fanatically defended strongpoints. In brief, the action at the strongpoints decided the issue during the drive toward Intramuros.

Harrison Park to the Manila Hotel

When the 5th and 12th Cavalry Regiments reached Manila Bay in Pasay suburb on 12 February, completing the encirclement of Admiral Iwabuchi’s forces, they immediately turned north toward the city limits.7 (Map 6) The first known Japanese strongpoint in this area was located at Harrison Park and at Rizal Memorial Stadium and associated Olympic Games facilities near the bay front just inside the city limits. The park-stadium complex extended from the bay east 1,200 yards to Taft Avenue and north from Vito Cruz Street – marking the city limits – some 700 yards to Harrison Boulevard, the 1st Cavalry Division-37th Division boundary. On the bay front lay the Manila Yacht Club and the ruins of Fort Abad, an old Spanish structure. Harrison Park, a generally open area surrounded by tree-lined roadways, was next inland. East of the south end of the park lay a baseball stadium similar to any of the smaller “big league” parks in the United States. Due north and adjacent to the ball field was Rizal Stadium, built for Olympic track and field events and including, inter alia, a two-story, covered, concrete grandstand. Still further east, near the banks of a small stream, was an indoor coliseum, tennis court, and a swimming pool, reading south to north. Beyond the small stream and facing on Taft Avenue lay the large, three-story concrete building of La Salle University. The 2nd Naval Battalion and various attached provisional units defended all these buildings.

The 12th Cavalry and the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry, took two days to fight their way north through Pasay suburb to Vito Cruz Street, rooting out scattered groups of Japanese who had holed up in homes throughout the suburb.8 During the attack, the 2nd Squadron of the 12th Cavalry extended its right flank across Taft Avenue to Santa Escolastica College, two blocks southeast of La Salle University.

On the morning of 15 February, after an hour of preparatory fire by one battalion of 105-mm. howitzers and a second

Rizal baseball stadium

of 155-mm. howitzers, the 12th Cavalry forced its way into La Salle University and the Japanese Club, just to the south of the university on the same side of Taft Avenue. The regiment also made an unsuccessful attempt to get into Rizal Stadium. Meanwhile, the 5th Cavalry’s squadron drove north along the bay front, forcing Japanese defenders caught in the open at Harrison Park into the stadium. Late in the afternoon cavalrymen broke into both the baseball park and the stadium from the east but were forced out at dusk by Japanese machine gun, rifle, and mortar fire.

The 5th Cavalry cleared the baseball grounds on 16 February after three tanks, having blasted and battered their way through a cement wall on the east side of the park, got into the playing field to support the cavalrymen inside. Resistance came from heavy bunkers constructed all over the diamond, most of them located in left field and in left center, and from sandbagged positions under the grandstand beyond the third base-left field foul line. Flame throwers and demolitions overcame the last resistance, and by 1630 the 5th Cavalry had finished the job. Meanwhile, elements of the 12th Cavalry had cleaned out the coliseum, Rizal Stadium, and the ruins

of Fort Abad. The two units finished mopping up during the 18th.

In the fighting in the Harrison Park–Rizal Stadium–La Salle University area, the 5th and 12th Cavalry Regiments lost approximately 40 men killed and 315 wounded.9 The 2nd Naval Battalion, destroyed as an effective combat force, lost probably 750 men killed, the remnants fleeing northward to join units fighting against elements of the 37th Division. The success at the park-stadium area paved the way for further advances north along the bay front, and the 12th Cavalry had begun preparations for just such advances while it was mopping up.

On 16 February, in the midst of the fighting in the stadium area, the 1st Cavalry Brigade (less the 2nd Squadron, 12th Cavalry) passed to the control of the 37th Division. General Beightler directed the brigade to secure all the ground still in Japanese hands from Harrison Park north to Isaac Peral Street – fifteen blocks and 2,000 yards north of Harrison Boulevard – and between the bay shore and Taft Avenue. The 5th Cavalry, under this program, was to relieve the 148th Infantry, 37th Division, at another strongpoint, while the 12th Cavalry (less 2nd Squadron) was to make the attack north along the bay front. The 12th’s first objective was the prewar office and residence of the U.S. High Commissioner to the Philippines, lying on the bay at the western end of Padre Faura Street, three blocks short of Isaac Peral.10

The 1st Squadron, 12th Cavalry, began its drive northward at 1100 on 19 February, opposed by considerable rifle, machine gun, and 20-mm. machine cannon fire from the High Commissioner’s residence and from private clubs and apartment buildings north and northeast thereof. With close support of medium tanks, the squadron’s right flank reached Padre Faura Street by dusk, leaving the residence and grounds in Japanese hands. During the day a Chinese guerrilla informant – who claimed that his name was Charlie Chan – told the 12th Cavalry to expect stiff opposition at the Army-Navy and Elks Clubs, lying between Isaac Peral and the next street north, San Luis.11 The units also expected opposition from apartments and hotels across Dewey Boulevard east of the clubs. The two club buildings had originally been garrisoned by Admiral Iwabuchi’s Headquarters Sector Unit, and the Manila Naval Defense Force commander had apparently used the Army-Navy Club as his command post for some time. Apartments and hotels along the east side of Dewey Boulevard were probably defended by elements of Headquarters Battalion and some of the provisional attached units.

Behind close artillery support, the cavalry squadron attacked early on 20 February and by 0815 had overrun the last resistance in the High Commissioner’s residence and on the surrounding grounds. The impetus of the attack carried the squadron on through the Army-Navy and Elks Clubs and up to San Luis Street and also through most of the apartments, hotels, and private homes lying on the east side of Dewey Boulevard

from Padre Faura north to San Luis. Only 30 Japanese were killed in this once-important Manila Naval Defense Force command post area; the rest had fled into Intramuros or been used as reinforcements elsewhere. The 1st Squadron, 12th Cavalry, lost 3 men killed and 19 wounded during the day, almost the exact ratio of casualties being incurred by other U.S. units fighting throughout Manila.

Now facing the cavalrymen across San Luis Street were the wide, open park areas of New Luneta, Burnham Green, Old Luneta, and the western portion of Wallace Field, reading from the bay inland. About 500 yards north across Burnham Green loomed the five-story concrete bulk of the Manila Hotel, and north of Old Luneta and Wallace Field lay Intramuros. The South Port Area lay just northwest of the Manila Hotel, the next objective. In preparation for the attack on the hotel, the 82nd Field Artillery Battalion intermittently shelled the building and surrounding grounds throughout the night. A patrol of Troop B dug in along the north edge of Burnham Green to prevent Japanese in the hotel from breaking out to reoccupy abandoned bunkers in the open park area.

With artillery support and the aid of two 105-mm. self-propelled mounts and a platoon of medium tanks, the 1st Squadron dashed into the hotel on the morning of 21 February. As was the case in other large buildings throughout the city, the hotel contained a series of interior strongpoints, the basement and underground passages being especially strongly held. Nevertheless, the hotel’s eastern, or old, wing was secured practically intact by midafternoon. Some Japanese still defended the basement and the new (west) wing, but the cavalrymen cleaned them out the next day. The new wing, including a penthouse where General MacArthur had made his prewar home, was gutted during the fight, and the general’s penthouse was demolished.12

The New Police Station

Just as one Japanese strongpoint was located on the left (west) of the American forces fighting in Manila, so there was another blocking the road to Intramuros on the American right, in the sector of the 129th Infantry, which had completed the reduction of Provisor Island on 12 February. The 129th’s particular bête noire was a block of buildings bounded on the north by an unnamed east-west extension of the Estero Provisor, on the east by Marques de Comillas Street, on the south by Isaac Peral Street (here the boundary between the 129th and 148th Infantry Regiments), and on the west by San Marcelino Street – the whole area being about 200 yards wide east to west and 400 yards long. The focal point of Japanese resistance in this area was the New Police Station, located on the northwest corner of San Marcelino and Isaac Peral Streets. At the northeast corner was a three-story concrete shoe factory, north of which, covering the block between San Marcelino and Marques de Comillas, was the Manila Club. North of the club were the buildings of Santa Teresita College, and west of the college, across

Manila Hotel in Ruins

San Marcelino, lay San Pablo Church and attached convent. All approaches to these buildings lay across open ground and were covered by grazing machine gun fire. The Japanese had strong defenses both inside and outside each building and covered each with mutually supporting fire. The New Police Station, two stories of reinforced concrete and a large basement, featured inside and outside bunkers, in both of which machine gunners and riflemen holed up. The 129th Infantry, which had previously seen action at Bougainville and against the Kembu Group, and which subsequently had a rough time against the Shobu Group in northern Luzon, later characterized the combined collection of obstacles in the New Police Station area as the most formidable the regiment encountered during the war.13 The realization that the strongpoint was well defended was no comfort to the 129th Infantry, since until the regiment cleared the area neither its left nor the 148th Infantry’s right could make any progress. The 37th Division, moreover,

could not simply contain and bypass the strongpoint, for to do so would produce a deep and dangerous salient in the division lines as the drive toward Intramuros progressed.

While the 129th Infantry’s right – the 2nd Battalion – had been completing the reduction of Japanese defenses on Provisor Island, the left and center, on 10 and 11 February, had moved westward in the area between Isaac Peral Street and Provisor Island generally up to the line of Marques de Comillas Street. During the 12th the 2nd Battalion crossed to the mainland from the west shore of Provisor Island but despite close and plentiful artillery support could make scarcely 150 yards westward along the south bank of the Pasig. On the same day the rest of the regiment did little more than straighten out its lines along Marques de Comillas. Attacks on the New Police Station and the Manila Club on 13 February were unsuccessful. Shells of supporting 155-mm. howitzers had little effect on the two buildings, and even point-blank fire from a tank destroyer’s high-velocity 76-mm. gun and 105-mm. high-explosive shells from Cannon Company’s self-propelled mounts did little to reduce the volume of Japanese fire.

On the morning of the 14th, Company A, 754th Tank Battalion, came up to reinforce the 129th Infantry.14 Behind close support from the tanks, Company B, 129th Infantry, gained access to the Manila Club; Company A, 129th Infantry, entered windows on the first floor of the New Police Station; and a platoon of Company C made its way into the police station’s basement. Having attacked at first light, Company A had surprised the Japanese before they had reoccupied positions vacated during the American preassault artillery and tank bombardment, but the Japanese soon recovered and put up a strong fight through the corridors and rooms of the police station’s first floor. Some extent of the strength and nature of the defenses is indicated by the fact that the 129th Infantry destroyed three sandbagged machine gun positions in one room alone.

Progress through the basement and first floor was slow but satisfactory until the Japanese started dropping hand grenades through holes chopped in the second story’s floor. With stairways destroyed or too well defended to permit infantry assault, Company A found no way to counter the Japanese tactics – a good example of why the troops usually tried to secure the top story of a defended building first. Evacuation proved necessary, and by dusk the Company A and C elements were back along Marques de Comillas Street, Company B holding within the Manila Club.

On 15 and 16 February only probing attacks were made at the New Police Station, the shoe factory, and Santa Teresita College, while tanks, TD’s, M7 SPMs, and 105-mm. artillery kept up a steady fire against all buildings still in Japanese hands. Even these probing actions cost the 1st Battalion, 129th Infantry, 16 men killed and 58 wounded. During the morning of the 17th the battalion secured the shattered shoe factory and entered Santa Teresita College, but its hold at the college, tenuous from the beginning, was given up as the 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, moved into the area to relieve the 129th. The New Police

Station, still the major stronghold, was still firmly in Japanese hands when the 129th Infantry left.

The 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, took up the attack about 1015 on the 18th behind hundreds of rounds of preparatory fire from tanks and M7’s.15 The battalion cleared the shoe factory and Santa Teresita College for good, and once more gained a foothold inside the New Police Station. Nevertheless, opposition remained strong all through the interior of the police station, while every movement of men past holes blown in the northwest walls by supporting artillery brought down Japanese machine gun and rifle fire from San Pablo Church, two blocks to the north. The 145th Infantry, like the 129th before it, found its grip on the New Police Station untenable and withdrew during the afternoon.

Throughout the morning of 19 February the police station and the church were bombarded by the 75-mm. guns of a platoon of Sherman M3 tanks, a platoon of M4 tanks mounting 105-mm. howitzers, a platoon of 105-mm. SPMs, and most of a 105-mm. field artillery battalion. During the afternoon Company B, 145th Infantry, fought its way into the east wing of the police station, while other troops cleaned out San Pablo Church and the adjoining convent against suddenly diminished opposition. The hold on the New Police Station – the Japanese still defended the west wing – again proved untenable and again the troops had to withdraw. Finally, after more artillery and tank fire had almost demolished the building, Company C, 145th Infantry, secured the ruins on 20 February.

The reduction of the New Police Station strongpoint and the nearby defended buildings had consumed eight full days of heavy fighting. The seizure of the police station building alone had cost the 37th Division approximately 25 men killed and 80 wounded, while the 754th Tank Battalion lost three mediums in front of the structure. The 37th Division could make no accurate estimate of Japanese casualties since the Japanese, who still controlled the ground to the west, had been able to reinforce and evacuate at will. During the fight the 37th Division and its supporting units had demolished the New Police Station, virtually destroyed the shoe factory, and damaged severely San Pablo Church and the Manila Club. Having reduced the strongpoint, the 37th Division’s center was now able to resume its advance toward Intramuros. Meanwhile, its right and its left had been engaged at other centers of resistance blocking the approaches to the final objective.

The City Hall and the General Post Office

Each strongpoint of the Japanese defenses and each building within each strongpoint presented peculiar problems, and the attacking infantry, while operating within a general pattern, had to devise special offensive variations for each. Such was the case at the General Post Office, located near the south end of Jones Bridge, and at the City Hall, a few blocks south along Padre Burgos Street

New Police Station

from the post office and across Padre Burgos from the filled moat along the east side of Intramuros. The 129th Infantry had cleared buildings along the south bank of the Pasig from Provisor Island to within 300 yards of Quezon Bridge and north of the New Police Station strongpoint to positions a block from the City Hall. The 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, relieved units of the 129th along the Pasig on 17 February, while the 3rd Battalion, 145th, took over in the vicinity of the City Hall on the 19th.

The 81-mm. mortars of the 129th Infantry had once set afire the four-story concrete City Hall, but the fire had done little damage and had failed to drive out the Japanese defenders who numbered, as of 20 February, approximately 200 men. On the 20th the 105-mm. SPMs of Cannon Company, 145th Infantry, aided by a single 155-mm. howitzer, blew a hole in the building’s east wall through which a platoon of the 145th Infantry, covered by machine gun and rifle fire as it dashed across intervening open ground, gained access. Japanese fire forced the platoon out almost as fast as it had entered. The next day all of Company I, 145th Infantry, got into the City Hall after SPMs and TD’s had knocked down the outer walls of the east wing. Again the hold proved untenable. On the morning of 22 February tanks, TD’s, SPMs, and 155-mm. howitzers laid point-blank fire against the east wing, pulverizing it, while 105-mm. howitzers, 4.2-inch mortars, and 81-mm. mortars plastered the roof and upper floors with indirect fire.

Company I re-entered the City Hall about 0900 on the 22nd. Using submachine guns, bazookas, flame throwers, demolitions, and hand grenades, the company fought its way through the

sound part of the structure room by room and overcame most of the resistance by 1500, but 20-odd Japanese held out in a first floor room. Since they showed no inclination to surrender – although invited to do so – Company I blew holes through the ceiling from above and, sticking the business end of flame throwers through the holes, summarily ended the fight. Removing 206 Japanese bodies from the City Hall, the 145th Infantry also quickly cleared the rubble from the west wing, where it set up machine gun positions in windows to support the assault on Intramuros.16

The fight for the General Post Office, conducted simultaneously with that for the City Hall, was especially difficult because of the construction of the building and the nature of the interior defenses. A large, five-story structure of earthquake-proof, heavily reinforced concrete, the Post Office was practically impervious to direct artillery, tank, and tank destroyer fire. The interior was so compartmented by strong partitions that even a 155-mm. shell going directly through a window did relatively little damage inside. The Japanese had heavily barricaded all rooms and corridors, had protected their machine gunners and riflemen with fortifications seven feet high and ten sandbags thick, had strung barbed wire throughout, and even had hauled a 105-mm. artillery piece up to the second floor. The building was practically impregnable to anything except prolonged, heavy air and artillery bombardment, and why the Japanese made no greater effort to hold the structure is a mystery, especially since it blocked the northeastern approaches to Intramuros and was connected to the Walled City by a trench and tunnel system. Despite these connections, the original garrison of the Post Office received few reinforcements during the fighting and, manifestly under orders to hold out to the death, was gradually whittled away by American artillery bombardment and infantry assaults.

For three days XIV Corps and 37th Division Artillery pounded the Post Office, but each time troops of the 1st Battalion, 145th Infantry, attempted to enter the Japanese drove them out. Finally, on the morning of 22 February, elements of the 1st Battalion gained a secure foothold, entering through a second story window. The Japanese who were still alive soon retreated into the large, dark basement, where the 145th Infantry’s troops finished off organized resistance on the 23rd. Nothing spectacular occurred – the action was just another dirty job of gradually overcoming fanatic resistance, a process with which the infantry of the 37th Division was by now all too thoroughly accustomed.17

The Hospital and the University

The focal point of Japanese resistance in the 148th Infantry’s zone was the area covered by the Philippine General Hospital and the University of the Philippines.18 The hospital-university complex

stretched about 1,000 yards south from Isaac Peral Street along the west side of Taft Avenue to Herran Street. The hospital and associated buildings extended west along the north side of Herran about 550 yards to Dakota Avenue while, about midway between Isaac Peral and Herran, Padre Faura Street separated the hospital and the university grounds.

Fortified in violation of the Geneva Convention – Japan, like the United States, was not a signatory power, but both had agreed to abide by the convention’s rules – the hospital buildings, all of reinforced concrete, were clearly marked by large red crosses on their roofs, and they contained many Filipino patients who were, in effect, held hostage by the Japanese. XIV Corps had initially prohibited artillery fire on the buildings, but lifted the restriction on 12 February when the 148th Infantry discovered that the hospital was defended. The presence of the civilian patients did not become known for another two or three days.

On 13 February the 148th Infantry, having fought every step of the way from the Estero de Paco, began to reach Taft Avenue and get into position for an attack on the hospital. On that day the left flank extended along Taft from Herran south four blocks to Harrison Boulevard, the 148th Infantry-12th Cavalry boundary. The infantry’s extreme right was held up about three blocks short of Taft Avenue, unable to advance until the 129th and 145th Infantry overran the New Police Station strongpoint. By evening the center and most of the right flank elements had learned the hard way that the Japanese had all the east-west streets east of Taft Avenue covered by automatic weapons emplaced in the hospital and university buildings. The 148th could not employ these streets as approaches to the objectives, and the regiment accordingly prepared to assault via the buildings and back yards on the east side of Taft.

On 14 February the 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, trying to push across Taft Avenue, found that the Japanese had so arranged their defenses that cross fires covered all approaches to the hospital and university buildings. The defenders had dug well-constructed machine gun emplacements into the foundations of most of the buildings; inside they had sandbagged positions on the first floors; lastly, Japanese riflemen and machine gunners were stationed at the windows of upper stories to good advantage. The Japanese, in brief, stopped the American battalion with mortar, machine gun, and rifle fire from the Science Building and adjacent structures at the northwest corner of Taft and Herran, from the main hospital buildings on the west side of Taft between California and Oregon, and from the Nurses’ Dormitory at the northwest corner of Taft and Isaac Peral. On the left the 3rd Battalion, pushing west across Taft Avenue south of Herran Street, had intended to advance on to Manila Bay, but halted, lest it become cut off, when the rest of the regiment stopped.

On the 14th, at the cost of 22 killed and 29 wounded, the 148th Infantry again could make only negligible gains. Indeed, the progress the regiment made during the 14th had depended largely upon heavy artillery and mortar support. The 140th Field Artillery fired 2,091 rounds of high-explosive 105-mm. ammunition, and 4.2-inch mortars of

the 82nd Chemical Mortar Battalion expended 1,101 rounds of high explosive and 264 rounds of white phosphorus.19 The white phosphorus, setting some fires in a residential district south of the hospital, helped the advance of the 3rd Battalion, but neither this nor the high-explosive shells appreciably decreased the scale of Japanese fire from the hospital and university.

On 15 February the 3rd Battalion reached Manila Bay via Herran Street – before the 12th Cavalry was that far north – and then wheeled right to assault the hospital from the south. That day the 2nd Battalion, in the center, was again unable to make any gains westward across Taft Avenue, but on the 16th had limited success in a general assault against the main hospital buildings, the Science Building (at the northwest corner of Taft and Herran), the Medical School (just west of the Science Building), and the Nurses’ Dormitory. The Nurses’ Dormitory, dominating the northern approaches to the university buildings, actually lay in the 129th Infantry’s zone, but the 148th attacked the dormitory because the 129th was still held up at the New Police Station.

By afternoon of the 16th the 148th Infantry had learned that some Filipino civilians were in the hospital. Making every possible effort to protect the civilian patients, the 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, which had to direct the fire of tanks, tank destroyers, and self-propelled mounts against every structure in its path in order to gain any ground at all, limited its support fires at the hospital to the foundation defenses insofar as practicable. With the aid of the close support fires, the battalion grabbed and held a foothold in the Nurses’ Dormitory after bitter room-to-room fighting. Further south, other troops, still unable to reach the Medical School, had to give up a tenuous hold in the Science Building when most of the 2nd Battalion withdrew to the east side of Taft Avenue for the night. The cost of the disappointing gains was 5 men killed and 40 wounded – the attrition continued.

During 17 February, with the aid of support fires from the 1st Battalion, now on the south side of Herran Street, the 2nd Battalion smashed its way into the two most easterly of the hospital’s four wings and overran the last resistance in the Nurses’ Dormitory and the Science Building. The advance might have gone faster had it not been necessary to evacuate patients and other Filipino civilians from the hospital. By dusk over 2,000 civilians had come out of the buildings; the 148th Infantry conducted 5,000 more to safety that night. At the end of the 17th the 148th had overcome almost all opposition except that at the Medical School and in a small group of buildings facing Padre Faura Street at the northwestern corner of the hospital grounds.

Throughout the 18th the 148th Infantry mopped up and consolidated gains, and on the morning of the 19th the 5th Cavalry relieved the infantry regiment. The cavalrymen were to complete the occupation of the hospital buildings, destroy the Japanese at the university, and clear Assumption College, lying west of the Medical School. The 148th Infantry relinquished its hold on the Medical School before the 5th Cavalry completed

its relief,20 and the cavalry regiment started its fighting with a new assault there, moving in behind point-blank fire from supporting medium tanks. Troop G, 5th Cavalry, gained access by dashing along an 8-foot-high wall connecting the Medical School to the Science Building. Employing flame throwers and bazookas as its principal assault weapons, the troop cleared the Medical School by dark on the 19th, claiming to have killed 150 Japanese in the action.21 The cavalry also secured Assumption College and a few small buildings on the hospital grounds that the 148th Infantry had not cleared. The 5th’s first day of action at the hospital-university strongpoint cost the regiment 1 killed and 11 wounded.

The 5th Cavalry, leaving elements behind to complete the mop-up at the hospital, turned its attention to Rizal Hall, the largest building on the university campus. Centrally located and constructed of reinforced concrete, Rizal Hall faced south on the north side of Padre Faura Street. The Japanese had strongly fortified the building, cutting slits for machine guns through the portion of the foundations lying just above ground, barricading doors and windows, emplacing machine guns on the flat roof, and setting up the ubiquitous sandbagged machine gun nests inside.

After a two-hour tank and tank destroyer bombardment, a Troop B platoon entered from the east about 1130 on 20 February. During the shelling most of the Japanese had taken refuge in the basement, but reoccupied defenses on the three upper floors before the cavalry could gain control of the stairways. Nevertheless, the platoon cleared the first floor and secured a foothold on the second after two hours of fighting. The small force then stalled, but the squadron commander declined to send reinforcements into the building. First, the interior was so compartmented that only two or three men could actually be engaged at any one point; more would only get in each other’s way. Second, he feared that the Japanese might blow the building at any moment.

Accordingly, the Troop B platoon resumed its lonely fight and, without losing a single man, reached the top floor about 1700. Half an hour later the squadron commander’s fear of demolitions proved well founded, for Japanese hidden in the basement set off a terrific explosion that tore out the entire center of Rizal Hall, killing 1 cavalryman and wounding 4 others. The platoon withdrew for the night.

A similar experience had been the lot of Troop G in the Administration Building at the southwest corner of the university campus. The troop had cleared about half its building by 1700, when explosions on the Japanese-held third floor forced it out. Action at Rizal Hall, the Administration Building, and other structures in the university-hospital area cost the 5th Cavalry another 9 men killed and 47 wounded on the 20th.

The regiment took the Administration Building against little opposition on 21 February, but did not secure Rizal Hall,

Rizal Hall

which it left in a shambles, until the 24th. The Japanese garrison at Rizal Hall alone had numbered at least 250 men, the last 75 of whom committed suicide during the night of 23-24 February.

The 5th Cavalry cleared other buildings on the campus during 22 and 23 February, and ran into some new defensive installations at University Hall, between Rizal Hall and the Administration Building. Here Troop E found caves dug through the walls of the basement and could not dislodge the Japanese even with flame throwers. Thereupon engineers poured a mixture of gasoline and oil into the various caves and ignited it. That appeared to take care of the situation neatly, but through a misunderstanding of orders Troop E withdrew for the night. Immediately, Japanese from buildings to the west reoccupied University Hall, which the cavalrymen had to recapture the next morning in a bitter fight. After that, only a little mopping up was necessary to complete the job at the university.

The battle for the hospital-university strongpoint had occupied the time and energies of the 148th Infantry and the 5th Cavalry for ten days. Success here played a major part in clearing the way for further advances toward Intramuros and the government buildings, but the success had been costly. The total American battle casualties were roughly 60 men killed and 445 wounded, while the 148th Infantry alone suffered 105 nonbattle casualties as the result of sickness,

heat exhaustion, and combat fatigue.22 The rifle companies of the 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, which had borne the brunt of the fighting at the hospital, were each nearly 75 men understrength when they came out of the lines on 19 February.23

For the Japanese the battle at the hospital-university strongpoint marked the virtual destruction of the Central Force as an organized fighting unit. The 5th Naval Battalion and the “attached units” also suffered staggering losses. The remnants – and a sorry few they were – of all these Japanese units withdrew to the government buildings and Intramuros.

With the capture of the university and hospital buildings, the New Police Station and associated structures, the Manila Hotel, the City Hall, the General Post Office, and the stadium area, the battles of the strongpoints were over. In their wake the 37th Infantry Division and the 1st Cavalry Division had left, inevitably and unavoidably, a series of destroyed and damaged public and private buildings. But whatever the cost in blood and buildings, the American units had successfully concluded the drive toward Intramuros. The last organized survivors of the Manila Naval Defense Force were confined in the Walled City, the South Port Area, and the Philippine Commonwealth Government buildings off the southeastern corner of Intramuros. The 37th Division was now ready to begin the reduction of this last resistance and planned an assault against Intramuros for 23 February, the very day that the last of the university strongpoint buildings fell.