Chapter 19: Manila Bay – Minor Operations

The clearing of Bataan and the capture of Corregidor concluded the major operations involved in the opening of Manila Bay. The task of securing the bay area was not, however, completed until XIV Corps cleaned out the southern shore from Cavite to Ternate and XI Corps cleared the small islands between Corregidor and the south shore. (See Map VII.)

The South Shore

XIV Corps cleared the southern shore of Manila Bay while XI Corps was making its drive to secure Bataan.1 In fact, elements of the 511th Parachute Infantry, 11th Airborne Division, occupied Cavite Peninsula and adjacent mainland areas on the same day that the 151st Infantry, 38th Division, landed at Mariveles, Bataan.

Important as the Cavite area was to the security of Manila Bay, the 11th Airborne Division had bypassed the prewar naval base during its drive to Manila because guerrilla reports and aerial reconnaissance had indicated no Japanese were in the Cavite region. From 15 through 20 February troops of the 511th Infantry, thoroughly combing the Cavite Peninsula and the nearby mainland, found only a few Japanese stragglers. The regiment seized a large quantity of Japanese equipment on the peninsula, for the Manila Naval Defense Force’s 5th Naval Battalion, together with Japanese antiaircraft units once stationed at Cavite, had left supplies and heavy weapons behind when they hurriedly withdrew northward into Manila on 2 February.2

Affairs at Ternate, about twenty miles southwest of Cavite, moved in a different fashion. Here was located a Japanese garrison of about 1,000 men built around the 111th Surface Raiding Base Battalion and attached units, including a few pieces of artillery. In addition, around 350 naval personnel who had recently evacuated Carabao Island in Manila Bay also holed up at Ternate.

A small guerrilla force under the control of the 11th Airborne Division began probing into the Japanese defenses at Ternate on 19 February, but found the Japanese positions too strong to attack without artillery support. The 188th Glider Infantry, 11th Airborne Division, started moving into the Ternate area on 27 February and launched an assault on 1 March behind the close

support of Fifth Air Force A-20’s, a medium tank company, and 75-mm. and 105-mm. artillery battalions. Hard fighting took place on 2 March, but the 188th and attached guerrillas secured the entire Ternate area by midafternoon the next day. The regiment ultimately discovered that most of the Japanese once dug in at Ternate had escaped into rough, rising ground to the south and southeast. At Ternate the 188th Infantry killed about 350 Japanese, captured or destroyed the bulk of the artillery the Japanese had manned in the area, and seized intact some 30 Japanese Army suicide boats. The casualties of the reinforced 188th Infantry are unknown.3

The capture of Ternate marked the completion of XIV Corps’ share in operations to secure Manila Bay, for on the same day the corps’ troops had overcome the last organized resistance within Manila. XI Corps had already reduced all Japanese opposition along other points on the bay’s shores and had secured Corregidor. All that remained was to clear the small islands between Corregidor and the south shore.

The Small Islands

The small islands that XI Corps had to secure were Caballo, a mile south of Corregidor; Carabao, hugging the Ternate shore; and El Fraile, about midway between the other two. The Japanese on those islands posed no threat to Allied shipping – their ordnance was too light – but, like other bypassed Japanese garrisons, they had to be taken sometime. Although the islands had little or no military significance, the operations to secure them offer interesting examples of military ingenuity and unorthodox tactics.

Caballo Island

There was no great hurry to launch attacks against the three minor objectives and it was, indeed, past mid-March before XI Corps could spare any troops for the job. On the 18th General Chase, the 38th Division commander, requested and received permission from XI Corps to reconnoiter Caballo Island.4 The next day a platoon of the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry, took off from Corregidor by LCM and landed unopposed at the eastern end of Caballo. Patrolling inland, the platoon discovered strong Japanese defense on high ground in the center of the island, which was only a mile long, east to west, and 500 yards wide.

Withdrawing the platoon, General Chase scheduled an assault with the reinforced 2nd Battalion for 27 March. In preparation Fifth Air Force planes, which had been using Caballo for a practice bombing range, bombed and strafed while Allied Naval Forces destroyers shelled Japanese positions along Caballo’s beaches. On the morning of the 27th, B-25’s and P-51’s bombed, strafed, and dropped napalm; destroyers

and rocket-equipped PTs bombarded for twenty minutes; artillery on Corregidor and Bataan joined in; and 151st Infantry 81-mm. mortars lobbed shells over from Corregidor. At 0900 LCMs of the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment began putting the assault infantry ashore.

At first there was no opposition. The Japanese garrison of some 400 Army and Navy troops was stunned or was hiding in defenses centering around three small knolls that, varying from 150 to 250 feet in height, lay near the middle of the island.5 Within fifteen minutes the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry had secured Hill 1, the most easterly, and had begun an advance toward Hill 2. At Hill 2 concentrated machine gun, mortar, and rifle fire as well as the hill’s rough, steep slopes slowed the attack. Nevertheless, the battalion captured the crest by the end of the day. Within another day it cleared all Caballo except for a group of approximately 200 Japanese who had retired to prewar mortar pits and tunnels near the base of Hill 2’s eastern slopes.

The Japanese in the pits and tunnels created an almost insoluble problem for the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry. The Japanese had so emplaced their weapons, which included machine guns and mortars, that they controlled all approaches to the mortar pits but could not be reached by American artillery or mortar fire. When the 151st Infantry concentrated its mortar fire against the pits’ entrances, the Japanese simply withdrew into the tunnels. When the American fire ceased – at the last possible moment before an infantry assault – the Japanese rushed out of the tunnels to man their weapons. Tanks were of no help to the American troops. From positions near the rim of the pits the tanks were unable to depress their guns sufficiently to do much damage to the Japanese. If the tanks tried to approach from above, they started sliding down Hill 2’s slopes into the pits. No combination of tank, artillery, and infantry action proved of any avail, and the 151st Infantry had to give up its attempts to take the Japanese positions by assault.

On 31 March engineers tried to pour diesel oil into one of the tunnels connecting the mortar pits, employing for this purpose a single ventilator shaft that was accessible to the 151st Infantry. Nothing came of the effort since it was impossible to get enough oil up the steep slopes of the hill to create a conflagration of significant proportions within the tunnels. Nevertheless, burning the Japanese out seemed to promise the only method of attack that would not risk the unduly heavy casualties of a direct infantry assault. No one, of course, wanted to throw away the lives of experienced troops on such an insignificant objective.

Finally, the commander of the 113th Engineers, 38th Division, suggested pumping oil up the hill from the beach through a pipeline from a ship or landing craft anchored at the shore line. The Allied Naval Forces happily fell in with this idea and supplied the 151st Infantry with two oil-filled ponton cubes; the Allied Air Forces provided a 110-horsepower pump and necessary lengths of pipeline and flexible hosing; and the 592nd Engineer Boat and Shore

Caballo Island

Regiment came through with an LCM to carry the pump and the ponton cubes.6

On 5 April over 2,500 gallons of diesel fuel were pumped into the pits and tunnels through the ventilator and were then ignited by white phosphorus mortar shells. “Results,” the 38th Division reported, “were most gratifying.”7 A huge flash fire ensued, followed by a general conflagration and several explosions. The engineers repeated the process on 6 and 7 April, and on the latter day carefully lowered two large demolition charges through the ventilator shaft and placed another at an accessible tunnel entrance. Set off simultaneously, the three charges caused an enormous volume of flames and several terrific explosions.

For the next few days the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry, tried to persuade a few Japanese who had lived through the holocausts to surrender and also executed a few infantry probing attacks. On 13 April a patrol entered the pits and tunnels, killed the lone surviving Japanese, and reported the positions cleared and secured.

Fort Drum

El Fraile

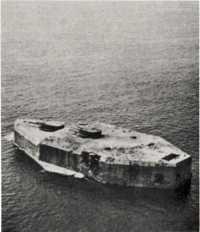

The next small island target was El Fraile, about five miles south of Caballo and a little over two miles off Ternate. Basically a reef, El Fraile had been turned into a formidable fortress long before World War II by U.S. Army engineers, who had constructed atop the reef a concrete, battleship-shaped citadel known as Fort Drum. The fortress walls were 25 to 36 feet thick, the top was 20 feet thick; the battleship was about 350 feet long and 145 feet wide, and it rose 40 feet above mean low water. The fort’s four 14-inch guns and four 6-inch guns had been knocked out by Japanese fire or American demolitions in 1942 and had never been repaired by the Japanese.8

Manifestly, some special method of attack had to be devised for Fort Drum, especially since Japanese machine guns covered the only feasible entrance, a sally port at the east end. The existence of a Japanese garrison had been discovered in late February when the crew of an Allied Naval Forces PT boat, having decided that the fortress was abandoned, made an unscheduled reconnaissance. The Japanese garrison of seventy naval troops permitted seven of the Americans to make their way into a sally port and about a third of the way through Fort Drum’s corridors. Suddenly, a Japanese machine gun opened up, killing one American naval officer and wounding another. The landing party made a hurried withdrawal, and it was the second week of April before an attempt to clear the fortress was undertaken.9

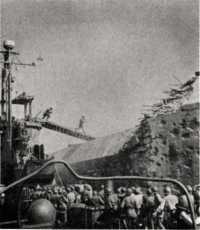

The 38th Division, responsible for the capture of Fort Drum, developed a plan of attack that followed naturally from the one employed successfully at Caballo Island – get troops atop Fort Drum and then feed oil and demolitions down ventilator shafts.10 Since the fortress walls were unscalable, the 113th Engineers, 38th Division, rigged a drawbridge-like ramp to the conning tower of an Allied Naval Forces LSM, and Company F, 151st Infantry, on the morning of 13 April, dashed across the

Boarding Fort Drum from LSM

bridge to the top of Fort Drum. While the infantry covered all openings, engineers followed across the ramp with an oil line and 600 pounds of TNT. The LCM employed at Caballo Island then began pumping oil into an open vent and engineers lowered TNT into another opening. After the engineers lit a 30-minute fuze, all hands withdrew and the LCM kept pumping. Suddenly, rough seas broke the oil line. Maj. Paul R. Lemasters, commanding the 2nd Battalion, 151st Infantry, together with a few enlisted men, dashed back over the ramp to cut the demolition fuze with only minutes to spare. Engineers then repaired the oil line and resumed pumping.

The Japanese inside Fort Drum were strangely quiet throughout all this activity, although a few rifle shots from an old gun port wounded a seaman aboard the LSM. Pumping continued without incident, and shortly after 1020 the LSM, the LCM, and a few LCVPs that had kept the LSM alongside the fort, pulled off to a respectful distance. By that time nearly 3,000 gallons of oil had been pumped into the ventilator.

The initial explosion, occurring about 1035, proved a disappointing, weak, and scarcely noisy failure. But while the commanders concerned were gathering aboard Admiral Barbey’s flagship to discuss the failure, burning oil seeped through openings created by the first explosion and reached the fort’s magazines, most of them containing ammunition from 1942 that the Japanese had never hauled away. At approximately 1045 there was a deafening roar from the fort. Great clouds of smoke and flame shot skyward; a series of violent explosions threw steel plates and chunks of concrete hundreds of feet into the air and a thousand yards out to sea; smoke and flames poured from every vent, gun port, shell hole, and sally port. The holocaust exceeded all expectations.

Fires and explosions of some magnitude continued until late afternoon, while smoke, heat, and minor explosions made reconnaissance of the fort’s interior impossible until 18 April. On that day infantry patrols penetrated Fort Drum’s innermost recesses and found 69 Japanese bodies. The entire Japanese garrison of a seemingly impregnable stronghold had been wiped out at the cost to the attackers of one man wounded.

Carabao Island

Troops of the 1st Battalion, 151st Infantry, on 16 April assaulted Carabao Island, which, lying a mile off the Ternate

Carabao Under Fire

shore, was the last objective in Manila Bay.11 Two days of air and naval bombardment preceded the attack. The 1st Battalion encountered no opposition, and the only living being it found on the island was one very badly shaken pig. The 350 Japanese naval troops who had once garrisoned Carabao had withdrawn to the mainland at Ternate.12 The disposition of the pig they left behind is not noted in the records, but it would not be unreasonable to assume that some of the men of the 1st Battalion, 151st Infantry, had fresh pork chops for supper on 16 April 1945.

With the seizure of Carabao Island, XI Corps brought to a successful conclusion its campaign to secure the entrance to Manila Bay. The bay had actually been safe for Allied shipping since 16 February, the day of the assault on Corregidor, and Allied vessels began using the great harbor of Manila well before the seizure of Carabao. The capture of Carabao, El Fraile, and Caballo was but a minor side show in the Luzon Campaign, and the operations to take the three islands had diverted only a miniscule portion of XI Corps’ energies – its main strength had long since moved against the Shimbu Group on the mainland.

Blank page