Part Six: The Conquest of Northern Luzon

Blank page

Chapter 24: Northern Luzon: The Situation and the Plans

Almost from the hour of the assault at Lingayen Gulf, Sixth Army’s task on Luzon was complicated by the fact that the army was compelled to fight many battles simultaneously on widely separated fronts. In late February General Krueger’s Forces were in action at Manila, on Bataan and Corregidor, against the Kembu Group west of Clark Field, and against the Shimbu Group in the mountains east of Manila. Krueger had already ordered XIV Corps to project some of its strength into southern Luzon. I Corps, having captured San Jose and seized control over the junction of Routes 3 and 11 near Rosario, had but recently completed operations to secure the Sixth Army’s base area and flanks and to provide protection to XIV Corps’ rear. Now General Krueger was preparing to launch still another offensive, and had alerted I Corps to make ready to strike into northern Luzon against the Shobu Group.

The Terrain and the Defenses in Northern Luzon

The General Situation

By the beginning of February I Corps had attained excellent positions from which to strike north against the Shobu Group, the strongest concentration of Japanese strength on Luzon, but General Krueger had had to postpone a concerted offensive in northern Luzon. General MacArthur’s redeployment and operational directives of early February had restricted the Sixth Army’s freedom of maneuver, concomitantly reducing its strength. General Krueger had therefore found it impossible to concentrate adequate forces for an immediate, major thrust against the Shobu Group. At least until XI and XIV Corps could assure the successful outcome of operations to secure the Manila Bay area, Krueger decided, he could not start I Corps northward in a determined drive against the Shobu Group. The strength left to the corps – three divisions instead of the five or more Krueger had expected to be able to employ in northern Luzon – was not enough.1

Krueger realized only too well that any delay in starting an attack north against the Shobu Group would inevitably redound to the advantage of the Japanese. By mid-February, at least, the Sixth Army commander had sufficient information at his disposal to conclude that the Shobu Group was beginning to realign its forces for a protracted stand

in the mountains of north Luzon, and he hoped the Japanese would not have too much time to dig in. What Krueger did not know was that General Yamashita had long had plans to move the Shobu Group into the triangular redoubt in northern Luzon, that Yamashita’s troops had been readying defenses in the mountains since late December, and that Yamashita had initiated a general withdrawal into the mountains before the end of January.2

Among Yamashita’s major concerns through February were the reorganization and rehabilitation of units Sixth Army had battered during January, and the problem of deploying these units, as well as others not yet committed, in the most effective positions for the defense of the triangular redoubt. The Shobu Group also had to move to centrally located depots the supplies shipped north from Manila and Central Plains dumps during December and January. The Japanese would likewise have to gather food from the rich Cagayan Valley and distribute it to troops throughout northern Luzon’s mountains. Time was of the essence in all the Shobu Group preparations. No relationship of time to defensive plans was more important than that involved in retaining control over the resources of the Cagayan Valley, for the group had been cut off from all outside sources of supply.

Heartland and rice bowl of northern Luzon, the Cagayan Valley averages 40 miles in width and extends from Aparri on Luzon’s northern coast south nearly 200 miles to Bambang on the Magat River.3 On the east the rugged and partially unexplored northern portion of the Sierra Madre, a 35-mile-wide barrier, separates the Cagayan Valley from the Pacific Ocean. West of the valley lies the equally rough Cordillera Central, which with the coastal Ilocos Mountains – also known as the Malaya Range – forms a 70-mile-wide barrier between the Cagayan Valley and the South China Sea. The complex Caraballo Mountains, forming a link between the southern reaches of the Cordillera Central and the Sierra Madre, block access to the Cagayan Valley from the Central Plains. (Map 19)

Except across the Aparri beaches, the entrances to the Cagayan Valley follow winding, ill-paved roads and trails through tortuous mountain passes. Coming north from San Jose, gravel-paved Route 5, scarcely two lanes wide, twists over the Caraballo Mountains into the Magat Valley via Balete Pass. Route 11, the other main road from the south, leads northeast from Baguio fifty miles to Bontoc, the northern apex of the Shobu Group’s defensive triangle. Traversing spectacularly beautiful but rough mountain country, Route 11 in 1945 was gravel and rock paved and varied between one and two lanes in width. From Bontoc Route 11, hardly more than a horse trail, follows the rugged, deep gorge of the Chico River northeast to the northern section of the Cagayan Valley.

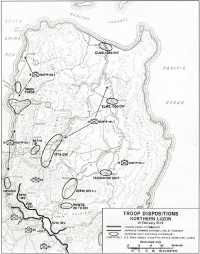

Map 19: Troop Dispositions, Northern Luzon, 21 February 1945

Bontoc, The Northern Apex

Baguio is reached by coming up the Bued River gorge from the Routes 3-11 junction near Rosario, following an asphalt-paved, two-lane section of Route 11. Route 9, another paved road, leads to Baguio from the South China Sea coast at Bauang, 20-odd miles north of Damortis. From Libtong, 55 miles north of Damortis, narrow, gravel-paved Route 4 leads through unbelievably precipitous terrain to a junction with Route 11 at Sabangan, a few miles southwest of Bontoc. Joining Route 11 as far as Bontoc, Route 4 then turns southeast to the Magat River and a junction with Route 5 at Bagabag, 30 miles northeast of Bambang.

The easiest entrance to the Cagayan Valley is at Aparri. The next best, since it provides direct access to the southern portion of the Cagayan Valley, is Route 5 via Balete Pass. Route 11 northeast from Baguio is a poor third choice, and, like all other entrances except Route 5 and Aparri, is so tortuous as to preclude its employment for major military operations.

Japanese Defense Plans

The military problems presented by the topography of northern Luzon impose upon attacker and defender alike a peculiar combination of concentration and dispersion of forces.4 Yamashita’s problem was further complicated by his plan to establish a triangular redoubt and simultaneously retain control of the Cagayan Valley for as long as possible. He would have to concentrate strength at the three apexes (Baguio, Bontoc, and Bambang) of his defensive triangle, but he would also have to deploy forces to defend all possible approaches to the Cagayan Valley.

Yamashita based his defensive deployment upon the assumption that Sixth Army would make its main efforts on the Baguio and Bambang fronts. He did not, however, ignore the other approaches to his triangular redoubt and the Cagayan Valley, and he took into consideration the possibility that Sixth Army might stage an airborne assault into the valley. He held at Aparri about two regiments of infantry and two battalions of artillery, all under the control of Headquarters, 103rd Division. On Luzon’s northwest coast – in the Vigan-Laoag area – he stationed the Araki Force, the equivalent of a regimental combat team and formed from various 103rd Division and provisional units. Initially, an understrength independent infantry battalion of the 103rd Division held Route 4 inland from Libtong.

The 19th Division was originally responsible for holding the coast south from Libtong and for blocking Route 9 from Bauang to Baguio. During January Filipino guerrillas became so active along Route 4 and on Route 11 between Bontoc and Baguio that Yamashita began to fear an amphibious assault in the vicinity of Libtong and a subsequent American drive inland to Bontoc. Accordingly, he decided to move the bulk of the 19th Division north to hold Bontoc, clear Route 4 west to Libtong, and

drive the guerrillas off the Baguio-Bontoc section of Route 11. The movement started late in February.

The transfer of the 19th Division necessitated realignment of forces on the Baguio front, and Yamashita had begun reshuffling troops there before the end of February. The 58th IMB started pulling north to defend Route 9 and to block some mountain trails leading toward Baguio between Route 9 and the section of Route 11 south of Baguio. The Hayashi Detachment, a regiment-sized provisional unit that held the region from Bauang to San Fernando, passed to the control of the 58th IMB. Simultaneously, the 23rd Division began establishing a new main line of resistance across Route 11 at Camp 3, between Rosario and Baguio. The division’s right was to extend northwest to connect with the 58th IMB left; the division’s left would stretch southeast almost fifteen miles across the Arodogat River valley to the upper reaches of the Agno River. The Arodogat provided an axis along which American troops might outflank Route 11 defenses on the east, while the gorge of the upper Agno led to roads running into Baguio from the southeast. The Agno’s canyon also provided a route to the Baguio–Aritao supply road that Yamashita was constructing as a link between his Baguio and Bambang apexes.

The net effect of these realignments on the west was to strengthen the defenses in front of Baguio. The Japanese forces regrouped along a narrower front, permitting them to employ their dwindling strength to the best advantage; they provided for protection along all flanking routes; and they moved into terrain even more favorable for defense than that the 23rd Division and 58th IMB had held during the fight for the Routes 3-11 junction.

To guard the northern Cagayan Valley against airborne assault, the 103rd Division stationed a reinforced infantry battalion at Tuguegarao. Here, 50 miles south of Aparri, were located airfields that the Japanese Naval Air Service had employed since the early months of the war in the Pacific. For the same purpose the Takachiho Unit, a provisional infantry regiment formed from 4th Air Army ground troops, some antiaircraft units, and a few paratroopers, held various 4th Air Army fields at Echague, 65 miles south of Tuguegarao and 30 miles northeast of Bagabag.

As of early February 5,000 to 7,000 men of the 105th Division – the rest of the division was with the Shimbu Group east of Manila – held Bagabag and Bambang. This force included a regiment, less one battalion, of the 10th Division. Initially stationed in the Bambang area to stamp out guerrilla activity, the 10th Division regiment redeployed southward late in the month.

The defense of the approaches to Bambang from San Jose was anchored on an MLR crossing the Caraballo Mountains and Route 5 about midway between the two towns.5 The key area along the San Jose-Bambang stretch of Route 5 was the Balete Pass–Sante Fe region, nearly twenty-five miles into the

Baguio

Caraballo Mountains from San Jose. Lying three miles north of the pass, Santa Fe is the terminus of the Villa Verde Trail, which winds northeast from the Central Plains over a spur of the Caraballo range west of Route 5. Balete Pass is located at the northern exits of the most tortuous terrain Route 5 traverses on its way north.

Responsibility for the defense of the Route 5 approach to Bambang was vested in the 10th Division. Although the Japanese estimated that the main effort of any Sixth Army attack toward Bambang would come up Route 5, the 10th Division was instructed to guard all flanking approaches carefully. The Villa Verde Trail provided a route for outflanking the Route 5 defenses at least as far north as Santa Fe, and near its eastern end provided access to the river valleys by means of which a flanking force could move north, west of Route 5, almost to Bambang, cutting the supply road to Baguio on the way. East of Route 5 lay Route 100, a third-class road that, beginning in the foothills ten miles southeast of San Jose, swung to the northwest through Carranglan and came into Route 5 at Digdig, midway between San Jose and Balete Pass. From Carranglan a rough trace known as the Old Spanish Trail – of which there were dozens in the Philippines – ran north through the Sierra Madre to Route 5 at Aritao, eastern terminus of the new supply road to Baguio and over halfway from Balete Pass to Bambang. Finally, lying between the Villa Verde Trail and the Agno Valley is the valley of the Ambayabang River. By trail connection to the Agno,

the Ambayabang Valley offered a possible route of access to Baguio from the southeast and along its own length, as well as by the Agno connection, provided other routes by which Sixth Army troops might push north to cut the Baguio–Aritao supply road. The front assigned to the 10th Division stretched from the upper Ambayabang southeast over twenty-five miles to Carranglan. It is presumed that some tie-in with the 23rd Division on the Baguio front was to be made along either the Agno or the Ambayabang Rivers.

In providing for defense of the various flanking routes, the Japanese expected that the Old Spanish Trail-Route 100 approach might well be the location of a secondary attack. The Japanese considered the terrain on that approach less formidable than that along the Villa Verde Trail, which, the Japanese thought, Sixth Army might use only for a very minor diversionary attack. Thus, of the three understrength RCTs or equivalent available to the 10th Division as of early February – troops that included organic units, attached regularly organized regiments and battalions, and provisional units of all sorts – one RCT was posted to hold the Route 100-Old Spanish Trail junction at Carranglan and that section of Route 100 lying between Carranglan and Route 5. A force roughly equivalent to an infantry battalion held the southwestern section of the Villa Verde Trail and another battalion, plus a battery of artillery, was stationed on the central section of the trail. One provisional infantry battalion was scheduled to move into the Ambayabang Valley.

Originally, the rest of the 10th Division was to hold an MLR across Route 5 near barrio Minuli, roughly five miles south of Balete Pass. However, by early February, when the fall of San Jose to the U.S. I Corps presaged an immediate attack north along Route 5, defenses in the Minuli area were by no means in shape to withstand a sudden onslaught. Therefore, seeking to gain time for defense construction along the MLR, the 10th Division deployed an RCT-sized delaying force across Route 5 at Puncan, a barrio lying about ten miles north of San Jose and the same distance south of Minuli. The remainder of the division worked feverishly on the defenses of the MLR.

One other unit was available on the Bambang front – the shattered 2nd Tank Division, which had been destroyed as an armored force in the defense of the approaches to San Jose during January. Less a 250-man group operating on the Villa Verde Trail and in the Ambayabang River valley, the 2nd Tank Division reassembled at Dupax, just off Route 5 near Aritao. There, early in February, the division started reorganizing, re-equipping, and retraining as an understrength infantry division, weaving into its depleted ranks casuals, replacements, and provisional units of all sorts.

A description of Yamashita’s special command arrangements completes the outline of Japanese defensive preparations in northern Luzon. As held true throughout the course of the Luzon Campaign, Yamashita was plagued by inadequate communications in northern Luzon, posing for him major problems of command and control. For the Bambang area he therefore set up what amounted to a corps headquarters under Maj. Gen. Haruo Konuma, a vice chief of staff of the 14th Area Army. As commander

of the Bambang Branch, 14th Area Army, General Konuma was to control the operations of the 10th and 105th Divisions and the 2nd Tank Division, as well as independent units in the area, within the framework of broad directives issued by Yamashita. Yamashita himself kept his headquarters at Baguio, retaining direct control over operations on the Baguio and Bontoc fronts.

The Sixth Army’s Plan

Sixth Army’s plans for operations against the Shobu Group did not spring full grown into being with I Corps’ arrival on the Damortis-San Jose-Baler Bay line.6 Indeed such plans as existed at the beginning of February had to be discarded for the most part as the original allocations of divisions to Sixth Army were cut back and more information was accumulated concerning Japanese strength, dispositions, and intentions in northern Luzon. There was no “set piece” plan of operations such as that of the Shobu Group. Instead, Sixth Army’s plan was evolutionary in character.

Early Plans

It was General Krueger’s first intention to concentrate his forces first on the Baguio front and Luzon’s west coast from Damortis north to San Fernando. The early capture of Baguio would produce certain obvious tactical advantages and would also have propaganda value since the city was the site of Yamashita’s combined 14th Area Army-Shobu Group headquarters. The development of the port at San Fernando would ease the burden upon overtaxed Lingayen Gulf facilities and would provide an additional base area from which operations in northern Luzon could be supported.7

Krueger originally planned to use two divisions in the Baguio-San Fernando area – the 43rd, already on the ground, and the 33rd, which reached Luzon on 10 February. While these two were making the main effort, the 25th and 32nd Divisions would operate on the Bambang front in what at first was expected to be a holding attack.8 Lack of resources made it impossible for Sixth Army to plan an airborne invasion of the Cagayan Valley, but General Krueger, through February and March, did hope to mount attacks in northern Luzon in addition to those contemplated for the Baguio and Bambang fronts. He planned that one division (the 37th) would undertake a series of shore-to-shore operations along the west coast north from Damortis, presumably as far

as Libtong and Vigan, the operations to begin in late March or early April. Krueger also considered the possibility of mounting an amphibious operation against Aparri by late May.9

Thus, Krueger’s early plans for operations in northern Luzon called for the employment of four divisions on the Baguio and Bambang fronts in simultaneous attacks that would start after mid-February. He would commit a fifth division along the west coast by April and would possibly employ a sixth at Aparri during May. The plans never came to fruition.

Factors Affecting the Plan

General MacArthur’s redeployment and operational directives of early February not only made it impossible for Krueger to concentrate forces for a major offensive against the Shobu Group but also forced Krueger to make sweeping changes in all existing or tentative plans for operations in northern Luzon. The most immediate effect of MacArthur’s directives was the relief of the 43rd Division and the 158th RCT in the Damortis-Rosario area and the replacement of those units with the 33rd Division. The next move was the redeployment of the 6th Division south to Bataan and the Shimbu front. In a week, I Corps lost one and one-third divisions.

Even though the redeployment of the 43rd Division and the 158th RCT left only one division available for the Baguio front, Krueger still wanted to make his main effort on that front. The 32nd Division, which had moved into a sector between the 25th and 43rd Divisions in late January, could be made to substitute for the 43rd Division. The 32nd could swing northwest up the Ambayabang, Agno, and Arodogat River valleys from the south and southeast, while the 33rd Division could drive north toward Baguio via Route 11.10 Under this concept, any effort by the 25th Division, left alone on the Bambang front by the redeployment of the 6th Division, would certainly be relegated to the status of a holding attack.

Before Sixth Army could work out the details of such a plan, the results of I Corps operations during February prompted new changes. The corps’ primary missions after the advance to San Jose were to protect Sixth Army’s left rear and block any attempts by the Japanese to move south out of the mountains. Krueger also directed the corps to reconnoiter northward and gave it permission to stage local attacks to improve positions and feel out Japanese strength in anticipation of a later all-out offensive on either the Baguio or the Bambang front.11

In accordance with these concepts, I Corps ordered the 43rd Division – which was not relieved until 15 February – to secure the terrain gained by the end of January, locate and develop Japanese positions north of the Damortis-Rosario section of Route 3, and maintain pressure against Japanese units holding out along the Hill 600-Hill 1500 ridge line east of the Rosario-Pozorrubio section of Route 3. The division, to which the 158th RCT remained attached, was also instructed to avoid involvement in a battle of such proportions that it might have to commit the bulk of its strength.

Following these instructions, the 158th RCT found unmistakable signs of a general Japanese withdrawal in the area north of the Damortis-Rosario road and discovered that the coast line was clear of Japanese for at least fifteen miles north of Damortis.12 The 43rd Division, on the other hand, found the Japanese determined to hold Route 11 northeast from Rosario, and every attempt to penetrate Japanese defenses along the Hills 600-1500 ridge line brought about an immediate Japanese counterattack. Moreover, 43rd Division patrols, including many the attached guerrillas conducted, were unable to move up the Arodogat River valley in the face of a strong Japanese counter-reconnaissance screen.

When the 33rd Division took over from the 43rd Division and the 158th RCT on 15 February, the 33rd had orders to concentrate for a drive up the coast to San Fernando – Sixth Army was still contemplating the idea of swinging the 32nd Division back northwest toward Baguio. Accordingly, I Corps directed the 33rd Division to clear the Hills 600 – 1500 ridge line in order to secure the division’s right (east) flank before moving to the coast. The division would also continue reconnaissance northward to develop Japanese positions and seek avenues of approach toward Baguio other than Route 11.13

The 33rd Division’s left (west) flank units, probing north after 15 February, learned that the 58th IMB withdrawal was well under way.14 In the center, division units patrolling northward along both sides of Route 11 found, as had the 43rd Division, that Japanese delaying positions and counter-reconnaissance operations blocked the road. Finally, I Corps’ instructions to clear the Hills 600-1500 ridge line involved the 33rd Division in a battle of larger scale than had been anticipated. From 19 through 22 February troops of the 130th and 136th Infantry Regiments, at the cost of approximately 35 men killed and 75 wounded, fought successfully to clear the last Japanese from the north-central section of the ridge line. Some 400 Japanese, most of them from the 1st Battalion of the 71st Infantry, 23rd Division, were killed in the area. The few Japanese who did not hold out to the death

withdrew southward to join compatriots on the Hill 600 complex.

As of the beginning of the last week of February, the Japanese had rebuffed all 33rd Division efforts to secure Hill 600 and to push into the Arodogat Valley to the east. It appeared that the division would have to spend so much time and effort securing the valley and the Hills 600-1500 ridge line that the proposed concentration on the coast for a move on San Fernando would be delayed unduly. The effort that could be expended on patrolling northward would also be circumscribed. Moreover, the 33rd Division’s patrolling had disclosed to Sixth Army the very significant fact that the Japanese withdrawals on the Baguio front had resulted in considerable strengthening of the defenses in front of that city. Manifestly, the 33rd Division was not strong enough to hold a defensive line, clear the Hills 600-1500 ridge line, secure the Arodogat Valley, advance toward San Fernando, patrol northward throughout its area of responsibility, and still mount an attack against the strengthened Japanese defenses around Baguio.

From the first Sixth Army had known that two divisions would be needed to achieve decisive results on the Baguio front, and the operations of the 33rd Division confirmed that opinion. But even as Sixth Army was obtaining this confirmation, Krueger had to reassess the idea that the 32nd Division might be swung northwest against Baguio while the 33rd moved on San Fernando.

The southern boundary of the sector that the 32nd Division began taking over on 27 January ran from Urdaneta, on Route 3, across a spur of the Caraballo Mountains to Route 5 at barrio Digdig, extending thence along Route 100 to Carranglan.15 On the northwest, the 32nd-43rd (and later 33rd) Division boundary ran east from Pozorrubio to the Arboredo River valley and then northeast to Malatorre, on the Agno some eight miles north of San Manuel. From Malatorre the boundary swung north to Sapit, near the headwaters of the Arboredo and about four miles southeast of Camp 3, the Route 11 strongpoint on the 23rd Division’s new MLR.

In the southern part of the 32nd Division’s sector the terrain rose slowly to the east. The most important town in the sector was Tayug, on the east side of the Agno and at the junction of roads from Urdaneta, San Manuel, and San Quintin. From Tayug, Route 277 runs northwest five miles to the Cabalisiaan River at Santa Maria, where the Villa Verde Trail begins its steep ascent into the Caraballo Mountains. Another road runs east-northeast five miles from Tayug to Batchelor, when a rough trace swings northeast to Valdes, six miles into the Caraballo spur. Valdes was a trail center from which foot patrols could strike north through the spur toward the Villa Verde Trail, northeast toward Santa Fe, and east to Route 5.

For the first five miles or so of its length north from Santa Maria, the Villa Verda Trail twists up the east side of a rough, bare, mile-wide ridge bounded on the east by the Cabalisiaan River and on the west by the Ambayabang. This portion of the trail was negotiable

for jeeps in 1945, but beyond that there was a fifteen-mile stretch – counting the various twists and turns – over which even foot troops would have trouble making their way and over which supply movements would be extremely difficult. At the northeast end of the trail there was a five-mile stretch, between Imugan and Santa Fe, that light trucks could negotiate.

The 32nd Division’s first mission was to move in strength north, northeast, east, and southeast roughly five miles beyond Tayug, simultaneously patrolling up the river valleys and east across the Caraballo spur. The division reached its new line by 1 February without opposition and during the next two days pushed its center on to Santa Maria, at the same time starting on its reconnaissance missions. Division patrols operating west of the Villa Verde Trail soon ran into counter-reconnaissance screens in the Arboredo and Agno River valleys. The Japanese strengthened the Ambayabang Valley, undefended in early February, after the middle of the month, and the 32nd Division quickly learned that the Japanese were preparing to defend all three valleys.

From the beginning the chief value of the valleys had been the possibility that movements along them would achieve tactical surprise. When it was learned that chances to gain surprise had passed, the logistical problems involved in supporting any attack through the valleys began to outweigh whatever tactical advantages might redound from operations along those routes of approach. The idea that the 32nd Division might be able to swing northwest toward Baguio through the valleys began to look less attractive.

To the east, meanwhile, the 32nd Division had sent a battalion up the Villa Verde Trail in a reconnaissance-in-force. By the evening of 7 February, having been opposed every step of the way from Santa Maria, the battalion had broken through a series of minor outpost positions and, about two and a half miles north-northeast of Santa Maria, had reached the principal Japanese OPLR defenses on the Villa Verde Trail. Since a major effort would be required to dislodge these Japanese, the 32nd Division held what it had, having been instructed to avoid a large-scale battle. As it was, by discovering that about a battalion of Japanese defended the southern section of the Villa Verde Trail, the division had successfully accomplished its initial reconnaissance mission in that sector.

Small groups from the 32nd Division had been patrolling across the Caraballo spur while the division was moving units up the Villa Verde Trail and the river valleys, and the reports brought back by patrols operating in the mountains were of considerable importance to future Sixth Army plans. First, the patrols discovered that most of the trails through the spur seemed to have been used before February 1945 by wild pigs rather than human beings. The ground proved to be so rough that the logistical support of any large force attempting to use the trails as a means of outflanking Japanese defenses on either Route 5 or the Villa Verde Trail would be virtually impossible.

Next, the few patrols that had managed to reach the northeast section of the Villa Verde Trail in the vicinity of Imugan reported that the Japanese were sending reinforcements west along the trail. This route of approach to

Villa Verde trail near San Nicolas

Bambang, it appeared, was going to be more strongly defended than anticipated. If so, the 32nd Division was going to be hard put to divert any effort at all toward Baguio. Furthermore, 32nd Division patrols penetrating as far as Route 5 learned that the stretch of highway north of Digdig was obviously going to be the scene of a major Japanese defensive effort. As events turned out, the results of this patrolling would prove of more importance to the 25th Division than to the 32nd, but the possibility that the 25th rather than the 32nd might become responsible for securing Route 5 north of Digdig was not, apparently, even a dream when, in early February, the 25th Division started patrolling north from San Jose.

Like the 32nd, the 25th Division had both reconnaissance and holding missions until late February.16 The line that the division was required to hold lay east and west of Rosaldo, a tiny

barrio on Route 5 about five miles northeast of San Jose. West of Route 5 the “secure line” lay about a mile into the Caraballo spur and paralleled Route 8, running northwest from San Jose to Umingan. East of Rosaldo the line extended three miles to Mt. Bolokbok, whence it swung generally south along the Pampanga River to Rizal, at the southern end of Route 100 and ten miles southeast of San Jose. The division would reconnoiter north of this line to the 25th-32nd Division boundary, crossing Route 5 at Digdig.

Patrols of the 25th Division operating in the southern section of the Caraballo spur found the terrain even worse than that in the Valdes region to the north. More important, division units that managed to traverse the spur discovered that the Puncan area was strongly defended, providing Sixth Army with the first indication of the 10th Division’s intention of stationing a delaying force of one RCT across Route 5 at that point.

In the center, along Route 5, the 25th Division sent a battalion-sized reconnaissance-in-force up the highway just as the 32nd Division had pushed a battalion up the Villa Verde Trail. The results were nearly identical. The 25th Division’s battalion reached Rosaldo on 14 February and a week later, having probed cautiously northward, was in contact with an organized Japanese delaying position another five miles up the highway. Any further effort would obviously involve major operations. Therefore, its reconnaissance mission accomplished, the 25th Division halted its battalion just as the 32nd Division had stopped its unit on the Villa Verde Trail.

To the east other 25th Division patrols, their reports augmented by information acquired from guerrillas, found substantial indications that the Japanese were going to defend both Route 100 and the Old Spanish Trail. By 21 February it was clear that the Japanese were not missing any more defensive bets on the 25th Division front than they were in the zones of the 32nd and 33rd Divisions.

Thus, I Corps operations on the Baguio and Bambang fronts during the first three weeks of February made it obvious that the Japanese were going to defend every avenue of approach to the north, with the possible exception of Route 3 on the west coast. There, 33rd Division reconnaissance had not carried sufficiently far northward to draw any conclusions about Japanese defenses. The Japanese withdrawal in front of Baguio, Sixth Army had learned, did not indicate weakness but actually foreshadowed a tightening and strengthening of defensive lines. Sixth Army had expected to find strong defenses on Route 5, but it now appeared that the Japanese were willing and able to devote greater effort to the defense of the river valleys, the Villa Verde Trail, Route 100, and the Old Spanish Trail than Sixth Army’s G-2 Section had at first estimated.

From the beginning of planning, General Krueger had realized that I Corps would need at least two divisions to achieve decisive results on the Baguio front. Now it was also obvious that the corps would require two divisions on the Bambang front in order to mount even a limited-objective holding attack. But I Corps had only three divisions available. It was time to reassess plans with a view toward deciding along which front the more decisive results could be achieved.

Bagabag

Guerrillas and Additional Intelligence

While I Corps was busy gathering important information through ground reconnaissance, other intelligence poured into Sixth Army headquarters from aerial reconnaissance, guerrilla reports, captured documents, and, presumably, radio intercepts. Through a combination of these sources Sixth Army, during the first weeks of February, learned of the Shobu Group’s plan for the triangular defensive redoubt. Of perhaps greater importance for future planning was the discovery of the Baguio–Aritao supply road. Sixth Army had previously considered the Baguio and Bambang defensive sectors to be more or less isolated from one another, but the existence of the supply road made it apparent that the Japanese could rapidly move troops from one front to the other. If that link in the Japanese defensive system could be severed, Sixth Army would achieve a significant tactical success. A decision had to be made selecting the front on which to put the effort necessary to close one end of the supply road.

The distance from the 33rd Division’s front lines on Route 11 to the Baguio end of the supply road was shorter than

that from the 25th Division’s advanced position on Route 5 to Aritao. But on the Baguio side the approach ran all the way through easily defensible terrain, whereas north of Santa Fe the terrain to Aritao was fairly open. Other factors favored the Route 5 approach. Having learned of Yamashita’s triangular defense concept, Krueger foresaw that a I Corps advance up Route 5 would not only threaten the Aritao terminus of the supply road but would also pose a direct threat to the Bambang anchor of the triangle. Moreover, not too far beyond Bambang lay the junction of Routes 4 and 5 at Bagabag. If I Corps seized that junction, it would cut the triangular redoubt off from supplies in the Cagayan Valley except for what the Japanese could move over Route 11 from Tuguegarao, a stretch of miserable road that guerrillas constantly blocked. The capture of both the Routes 4-5 junction and the Aritao entrance to the supply road would not only open two additional routes over which Sixth Army troops could advance into the Shobu Group redoubt but would also open the way into the Cagayan Valley, an eventuality that promised to cut off strong Japanese forces from the rest of the Shobu Group. All in all, it appeared that if the Sixth Army could push to and beyond Aritao the Shobu Group would face disaster. Such decisive results could not be achieved on the Baguio front, for from Baguio the Shobu Group forces could make a fighting withdrawal along easily defensible Route 11, retiring even further into the mountains while continuing to receive supplies from the Cagayan Valley. Finally, by the third week in February, Krueger had decided it would be unsound to reorient the 32nd Division from the firm contact the unit had established along the Villa Verde Trail, such an obvious route to outflank the Shobu Group’s Route 5 defenses. Krueger’s decision would have to favor the Bambang front.

Before the end of February, then, Krueger had had to reorient Sixth Army’s plans completely. The 25th and 32nd Divisions would make the major effort against the Shobu Group, striking north on the Bambang front. The Baguio front Krueger relegated to a holding status. There, until the 37th Division could move north from Manila, the 33rd Division would have a supporting, secondary role.

While making these decisions, Krueger still had to worry about the Japanese 19th Division, which, he knew by mid-February, had withdrawn from the Baguio region. He learned that the division was moving north toward the hitherto undefended Bontoc area, northern apex of Yamashita’s triangular redoubt. For obvious reasons, Krueger wanted to contain the 19th Division in the Bontoc area, but with all available American divisions committed to definite courses of action on the Baguio or Bambang fronts, he could spare no troops for the job of pinning the 19th Division in place. There was, however, a force upon which he could depend for help – the United States Army Forces in the Philippines, Northern Luzon.

Usually known as the USAFIP(NL), this organized guerrilla force was led by Col. Russell W. Volckmann, a U.S. Army regular who, at the risk of sudden death at the hands of the Japanese (if not ultimate court-martial by the U.S. Army for disobeying surrender orders) had taken to the hills upon the fall of the Philippines

in 1942.17 When Sixth Army reached Luzon on 9 January Colonel Volckmann’s force had numbered about 8,000 men, of whom only 2,000 were well armed. After the invasion Sixth Army started running supplies to the USAFIP(NL), first by small craft that put into various guerrilla-held beaches on the west coast and later by C-47 aircraft that flew to guerrilla-held dropping grounds and airstrips. Within two months after the landing at Lingayen Gulf, Filipino enthusiasm had brought Volckmann’s strength up to 18,000 men, while the supply of arms increased not only because of Sixth Army’s efforts but also because their own new strength enabled the guerrillas to capture equipment from isolated Japanese outposts and patrols.

Volckmann divided his organization into command, combat, and service echelons, respectively numbering 1,400, 15,000, and 2,700 troops. The combat echelon was in turn broken down into five infantry regiments – the 11th, 14th, 15th, 66th, and 121st – each with an “authorized” strength of 2,900 officers and men, and each subdivided into three rifle battalions of four rifle companies apiece. The combat echelon was soon strengthened by the addition of a battalion of mixed field artillery, equipped with captured Japanese ordnance.

At the beginning of February Volckmann’s headquarters was at Darigayos Cove, on the coast about fifteen miles north of San Fernando. His missions as assigned by Sixth Army, which assumed control of USAFIP(NL) on 13 January, were to gather intelligence, ambush Japanese patrols, seize or destroy Japanese supplies, disrupt Japanese lines of communication, and block Japanese routes of withdrawal into and exit from the Cagayan Valley.18 It was not, apparently, initially intended that Volckmann’s force would engage in sustained efforts against major Japanese units, and there seems to have been little hope that Volckmann’s, or any other guerrilla unit, would ever become effective combat organizations. The most help GHQ SWPA and Sixth Army probably expected was in the form of harassing raids, sabotage, and intelligence.

But Volckmann – and other guerrilla leaders on Luzon as well – interpreted his missions as broadly as his strength and armament permitted. By the end of February USAFIP(NL) had cleared much of the west coast of Luzon north of San Fernando and also controlled the north coast west of Aparri. Volckmann had rendered Route 11 between Baguio and Tuguegarao and Route 4 from Libtong to Bagabag virtually impassable to the Japanese. Indeed, as has been shown, one of the main reasons that Yamashita moved the 19th Division north had been to regain control over the two vital highways so that supplies could continue moving into the final redoubt. While USAFIP(NL) did not possess sufficient strength to attack major Japanese concentrations or to hold out against large-scale punitive expeditions, it had diverted and pinned down Japanese forces that could undoubtedly have been used to better advantage elsewhere. It would appear that by mid-February

USAFIP(NL) had accomplished far more than GHQ SWPA or Sixth Army had either expected or hoped.

While Sixth Army had probably not planned to use guerrillas extensively, it seems that the loss of the 40th and 41st Divisions, coupled with the other difficulties involved in securing sufficient regular troops for operations in northern Luzon, prompted General Krueger to reassess the role guerrillas could and would play.19 During February more and more guerrilla units were outfitted with weapons and clothes, some of them relieving regular forces in guard duties and mopping-up actions while others were sent to the front for direct attachment to and reinforcement of combat units. In the case of USAFIP(NL), supply efforts were redoubled, a broad program of air support was set up and air support parties were sent to Volckmann, and, as time passed, Volckmann’s missions were enlarged. Indeed, Volckmann’s forces came to substitute for a full division, taking the place of the regular division that Krueger had planned to send up the west coast in a series of shore-to-shore operations, an undertaking that, by mid-February, USAFIP(NL) successes had rendered unnecessary.

The Plan in Late February

Thus, as of late February General Krueger had available for operations in northern Luzon the 25th, 32nd, and 33rd Divisions and the USAFIP(NL) as a substitute for a fourth division. He expected the 37th Division to become available, one RCT at a time, beginning in late March.

With these forces, Sixth Army’s plan called for the first main effort in northern Luzon to be made on the Bambang front by the 25th and 32nd Divisions. Meanwhile, the 33rd Division would mount holding attacks on the Baguio front, which would explode into decisive action once the 37th Division, released from its garrison duties at Manila, moved north. Initially, USAFIP(NL) would continue its harassing missions and provide such help in the San Fernando and Baguio areas as was feasible. (Two of its battalions had been fighting under 43rd and then 33rd Division control since late January and other units were already moving toward San Fernando.) When the 37th Division began moving into position on the Baguio front, USAFIP(NL) would undertake a drive inland along Route 4 toward the junction of Routes 4 and 11 at Bontoc.

These plans had not emerged all of a piece from the G-3 Section of Sixth Army headquarters. The concept of making the main effort along the Bambang approaches developed during the first three weeks of February; the final plans for the employment of the 37th Division and USAFIP(NL) did not develop much before mid-March; the idea that the 33rd Division would have a holding mission until the 37th Division reached the Baguio front was clear well before the end of February.