Chapter 25: The Collapse of the Baguio Front

The 33rd Division’s Holding Mission

The Situation in Late February

The decision to relegate the 33rd Division to a holding mission on the Baguio front did not affect the tasks the division had already assumed.1 First, the unit had to clear the remaining Japanese from the bare-sloped, sharp-crested Hills 600-1500 ridge line dominating Route 3 from Pozorrubio north to the junction of Routes 3 and 11 near Rosario. Simultaneously, the division was to secure the terrain east of the ridge to include the Arodogat River valley. It would also reconnoiter up the coast to Agoo, six miles north of Damortis; from Rosario northward seven miles to Pugo; and from the Routes 3-11 junction northeastward along Route 11 six miles to Camp 2. The reconnaissance line ran eastward from Camp 2 almost five miles across the rugged southern reaches of the Cordillera Central to the 32nd-33rd Division boundary at Sapit.

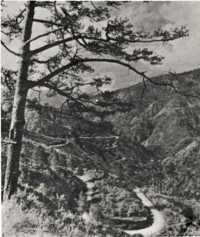

Route 11, the 33rd Division would soon learn, was the most strongly defended and most easily defensible approach to Baguio. Running northeast and then north into Baguio from its junction with Route 3 near Rosario, Route 11 lies deep in the gorge of the Bued River, the headwaters of which rise within the Baguio city limits. Noses of steep-sided ridges rise sharply from the gorge in every direction, tower to a height of 3,500 to 4,000 feet within half a mile of the highway, and then ascend to mountain crests of 6,000 feet. So sharp is the gorge of the Bued that much of Route 11 can lie in deep shadow cast by the dominating ridges, while one or two thousand feet up the slopes the sun brightly illuminates the terrain.

A few sharp, short ravines leading into the mountains from the Bued Gorge have a rich verdure of dense jungle undergrowth, and some of the ridge slopes towering above the gorge have respectable, although rather thin, stands of timber. For the most part, however, the steep ridges’ sides are covered by short grasses interspersed with scattered trees; rock outcroppings are not uncommon. Asphalt-paved Route 11, the best road in northern Luzon, is easily blocked and broken. Between the Routes 3-11 junction and Baguio, Route 11 crosses the Bued River five times and bridges the deep ravines of tributary

Route 11 winding south from Baguio

streams at another fourteen points. At most of the nineteen crossing sites along the twenty miles between the junction and Baguio the bridges are 50 to 100 feet above the rocky bed of the Bued or the various steep-sided ravine bottoms. Without the bridges, it is virtually impossible to move heavy equipment up the highway. As of late February 1945 the Allied Air Forces and guerrillas had already destroyed several of the spans; those remaining intact troops of the Japanese 23rd Division would knock out as they retreated northward under pressure from the 33rd Division. A rapid advance up Route 11, the 33rd Division quickly realized, would present as many engineering as tactical problems.

Tactically, the terrain along Route 11 gave every advantage to the defenders, who were well entrenched on dominating ground from which they had excellent observation. The 33rd Division would clear one side of a ridge nose, round the nose, and find the Japanese just as strong on the opposite side. Attack along the highway promised only an arduous, time-consuming, and costly process of clearing the adjacent terrain inch by inch. With a relatively small force, the Japanese could hold up the entire 33rd Division almost indefinitely.

A second approach to Baguio in which the 33rd Division became interested began at Pugo, seven miles north of Rosario along a fairly good gravel road that traverses easy terrain. From Pugo, a narrow, rocky trace known as the Tuba Trail winds its way tortuously north and northeast through sometimes forested and sometimes semi-barren mountains to barrio Tuba, two and a half miles southwest of Baguio. A fairly good gravel road led from Tuba to Route 11 at the southern edge of Baguio.2 Along the Tuba trail the terrain would again give the defenders all the advantages.

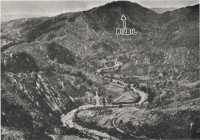

A third approach to Baguio began at Caba, on the coast eight miles north of Agoo. A good, one-lane gravel road ran east three miles from Caba and then connected with an abandoned railroad bed. With some breaks, the railroad grade continued eastward another five miles over rough mountains to Galiano, about nine miles west of Baguio and site of a small hydroelectric plant that served the city of Baguio. At Galiano another all-weather gravel road, following the

Galiano Valley Approach To Baguio

old railroad bed, ran uphill through Asin – site of another small hydroelectric plant and a hot salt bath resort – to Route 9 at the western edge of Baguio.3 Between the end of the gravel road from Caba and the beginning of the gravel road at Galiano this approach runs through fairly low but rugged, broken hill country. The road from Galiano to Asin, a distance of almost four miles, is easy enough, but Asin sits in a deep bowl surrounded by partially wooded mountains that rise sharply to a height of over 2,000 feet. Just east of Asin the road passes through two short, narrow tunnels, from which it is a steady uphill climb through fairly open country to the junction with Route 9. Asin is the key area along this approach, for further progress toward Baguio demands a breakthrough across the dominating terrain at the bowl and the two tunnels.

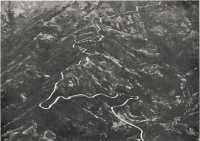

The fourth approach to Baguio in the 33rd Division’s zone was Route 9, originating at Bauang, on the coast seven miles north of Caba. From Bauang

Route 9 near Burgos, looking eastward

this two-lane, macadam highway runs generally southeast twenty miles – straight-line distance – into Baguio. Much of the terrain along Route 9 is less forbidding than that along the other three approaches, and the highway usually runs over and along ridges rather than through gorges and valleys. Altogether the easiest approach to Baguio, Route 9 still passes many points where a determined defending force could dig in and hold back a much superior attacking group.

As of 21 February 1945, when it began patrolling along or toward the approaches to Baguio, the 33rd Division had divided its zone into three regimental sectors. One regiment was responsible for the entire area from the coast east almost as far as Route 11; the second was to reconnoiter up Route 11; the third would clear the Hills 600-1500 ridge line and the Arodogat Valley, patrolling as far as Sapit.

The Japanese had divided the ground in much the same manner. One regiment covered the ground east of Route 11, including the Agno Valley; a second regiment was astride Route 11; a third had troops along the Tuba Trail approach. The 58th IMB defended both Route 9 and the Galiano-Asin approach to Baguio. As of the last week of February, the bulk of the 58th IMB and the 23rd Division was established along an MLR; the 23rd Division still maintained

outposts on the Hills 600-1500 ridge line and in the Arodogat Valley.

The Japanese believed that Sixth Army would make its main effort on the Baguio front along Route 11. They thought Sixth Army might launch secondary attacks up the Agno and Ambayabang River valleys, and they also estimated that some American forces might strike toward Baguio along the Tuba Trail. This early in the battle for Baguio, the Japanese were little worried about American advances over the Galiano–Asin road or along Route 9. However, the Japanese deployment indicates that the 58th IMB was prepared to defend these two approaches should the necessity arise.

Probing Operations to Mid-March

During the last week of February and the first few days of March the 33rd Division met with considerable and, in some areas, unexpected success in accomplishing its missions.4 On the east, behind precisely adjusted fire of two artillery battalions, 33rd Division troops overran the last Japanese positions on the Hills 600-1500 ridge line without suffering a single casualty. Then, after a sharp fight at a hill dominating the entrance, the American troops had no trouble clearing a few Japanese stragglers from the Arodogat Valley. (Map 20)

Along Route 11, however, the story was different. Here the 71st Infantry of the 23rd Division conducted a fighting withdrawal, and by the middle of the first week in March 33rd Division patrols were still a mile and a half short of their reconnaissance objective, Camp 2. Meanwhile, units patrolled up the road from Rosario to Pugo against little opposition, but then found the first stretches of the Tuba Trail defended by elements of the 64th Infantry, 23rd Division, holding positions on high ground. Farther north, other patrols reached barrio San Jose, midway between Caba and Galiano, finding no signs of Japanese. The most startling development of the period was the unopposed occupation of Agoo and the concomitant discovery that no Japanese defended Route 3 from Agoo five miles north along the coast to the Aringay River.

As a result of its patrol successes, the 33rd Division became ambitious. It had uncovered a general pattern of Japanese withdrawal all along its front, and, although the withdrawal was of a fighting nature along Route 11, the division believed it could push on much faster toward Baguio. Maj. Gen. Percy W. Clarkson, the 33d’s commander, had from the start been unhappy at having been assigned a holding mission, and saw in the Japanese withdrawal on his front a welcome chance to drive on toward Baguio immediately. He proposed to General Swift, the I Corps commander, that the 33rd Division strike for a new “secure line” extending from Aringay southeast through Pugo to Route 11 at Twin Peaks, a mile short of Camp 2, and then extend its reconnaissance northward accordingly.

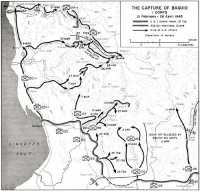

Map 20: The Capture of Baguio, I Corps, 21 February-26 April 1945

Swift approved Clarkson’s plan and set a new reconnaissance line that stretched from the coast at Caba east through Galiano to Baguio and thence southeast about seven miles to the 33rd-32nd Division boundary at Balinguay, ten miles north of the previous reconnaissance limit point of Sapit. The 33rd Division’s displacement northward, Swift continued, would start on 7 March.5

The pattern of operations for the next week or so followed almost precisely that of the previous week and a half. On the west 33rd Division patrols secured Aringay

and Caba against no opposition and started east along the trail to Galiano. Other troops cleared the Japanese from hills at the entrance to the Tuba Trail, and before the end of the second week of March patrols were three winding miles northeast along the trail from Pugo. As before, there were no significant gains on the east, where even small patrols found it difficult, in the face of Japanese counter-reconnaissance operations, to penetrate along Route 11 as far as Twin Peaks.

The almost complete lack of opposition along the coast as far as Caba was certainly surprising, and still more surprising was the fact that guerrilla and 33rd Division patrols reported virtually no Japanese strength at Bauang where, seven miles north of Caba, Route 9 began at its junction with Route 3. And again, as far as patrols had penetrated, Japanese defenses along the Tuba Trail and the trails to Galiano did not seem strong. Moreover, terrain reconnaissance parties reported that no inordinate engineer effort would be required to bulldoze roads that trucks and artillery could use at least in dry weather along the Tuba Trail and the Galiano road. All in all, the situation on the west seemed to General Clarkson to invite immediate exploitation, and, in mid-March, he had a plan of exploitation ready.

Limited Objective Attacks to Late March

Clarkson proposed sending battalion combat teams toward Baguio along Route 11, the Galiano road, and the Tuba Trail. He wanted to concentrate the rest of the division – two RCTs less one battalion held in reserve – along Route 9 for a quick dash into the city. If he could get forces in position for such a coordinated effort by 1 April, Clarkson believed, he would have an excellent chance to seize Baguio before 15 May. The plan required that strong guerrilla forces, already operating in the San Fernando area only seven miles north of Bauang, hold in place to secure the division’s northern flank.6

Like Clarkson, Swift was no man to let opportunity go by without being at least touched, if not seized. Also like Clarkson, the I Corps commander had concluded by mid-March that the western approaches to Baguio promised more decisive results than those along Route 11 or the river valleys to the east. There was no logic in permitting the Japanese to redeploy forces for the defense of Route 9 unmolested, and it made sense to take advantage of apparent Japanese weakness in the Bauang region. On the other hand, Swift thought, it would be advantageous to keep the Japanese thinking that the main effort toward Baguio would come along Route 11 and to promote a belief that no attacks would be launched over the Galiano road and Tuba Trail approaches.

Thus, it appears that General Swift was of a mind to approve Clarkson’s proposals, and Clarkson’s plan might well have worked. The 33rd Division, however, never got the chance to find out. Sixth Army had already drawn up plans to open the third front in northern Luzon, plans that required redeployment of USAFIP(NL) troops from

the San Fernando area. In addition, Swift had certain reservations about the 33rd Division’s proposals. He saw a possibility that a strong, sudden Japanese counterattack might force him to redeploy elements of the 25th or 32nd Divisions from the Bambang front in order to pull 33rd Division chestnuts out of the fire should Clarkson’s somewhat ambitious plans result in overextension. As a result, Swift would not give blanket approval to Clarkson’s suggestions. On the other hand, the corps commander was willing to let the 33rd Division mount limited objective attacks. First, he instructed Clarkson to push one regiment (less a battalion) up Route 11 as far as Camp 4, about six miles north of Twin Peaks. In mounting the attack the 33rd Division was to avoid becoming so involved that it would be forced to commit too much strength on its diversionary front. Second, Swift directed the division to temporarily halt strong attacks along the Tuba Trail and the Galiano road and cease its engineer work along the Tuba Trail, lest the Japanese send strong reinforcements to that approach. Finally, I Corps directed the 33rd Division to send a battalion-sized reconnaissance-in-force into Bauang and thence inland four miles along Route 9 to Naguilian. The force was to withdraw quickly if it encountered strong opposition or if the Japanese showed signs of counterattacking.7

The I Corps orders, unsatisfying as they were to Clarkson, established the pattern of the 33rd Division’s operations for the latter half of March. On the east, moving slowly so as to avoid pitched battle, troops on Route 11 took a week to secure the Camp 3 area. Since the 23rd Division MLR lay just north of Camp 3 and since the Japanese blocked all trails on both sides of Route 11, the 33rd Division’s force on the highway halted. It was evident that any attempt to go on would involve the division in just the sort of fight General Swift had ordered it to avoid. In the center patrols encountered no opposition as they moved to within a mile of Galiano, but other patrols found increasing evidence that the Japanese were prepared to defend the Tuba Trail tenaciously.

Again the key action took place on the division’s left. On 19 March troops seized intact the Route 3 bridge across the Bauang River and secured the town of Bauang against negligible resistance. Patrols quickly started east along Route 9 to Naguilian and occupied that town against minor opposition on 23 March. Four days later reconnaissance elements were almost as far as Burgos, four miles east of Naguilian and approximately the same distance short of 58th IMB MLR defenses on Route 9.

Without definite information about Japanese defenses east of Naguilian, General Clarkson had begun to think that Route 9 might be wide open as far as Baguio. He felt that he needed only a little protection on his left rear before he could launch a major attack down Route 9 to Baguio and, with his division fretting under the restrictions of its holding mission, again proposed to Swift an immediate drive to Baguio. For a few days, at least, Clarkson could also suggest to Swift that the 33rd Division’s left rear had adequate protection. USAFIP(NL) forces at San Fernando, with whom the 33rd Division had made

contact on 20 March, reported that San Fernando was clear of Japanese, that the coast from Bauang to San Fernando was secure, and that the Japanese forces formerly holding the San Fernando region had withdrawn into Baguio.

The USAFIP(NL) at San Fernando

With one battalion of its 121st Infantry, the USAFIP(NL) had begun operations against San Fernando in early January, just before Sixth Army had started ashore at Lingayen Gulf.8 That battalion – its mission was to gather intelligence – was reinforced by a second during February, and a concerted attack on San Fernando began late in the month when Marine Corps SBD’s from the Mangaldan strip at Lingayen Gulf started providing the USAFIP(NL) close support. The guerrilla regiment was moving against the 3,000-man Hayashi Detachment – three infantry battalions and some artillery – which had become responsible for the defense of San Fernando after the 19th Division left the region.9

Recognizing that San Fernando was an indefensible cul-de-sac, the Hayashi Detachment placed its main defenses in hills north, east, and southeast of the town and, for lack of strength, withdrew most of the troops it once had at Bauang, leaving the vital Routes 3-9 junction virtually wide open. Since San Fernando was not a road junction town, the only explanation for the decision to defend there rather than at Bauang must have been the hope that supplies and reinforcements might yet be brought into Luzon through the San Fernando port.

During late February and early March the two USAFIP(NL) battalions attacked with only limited success. About mid-March another of the 121st’s battalions, released from attachment to the 33rd Division, came north to join in the action, while about the same time the Hayashi Detachment lost one of its battalions, which the 58th IMB pulled back to Baguio as a reserve. The Hayashi Detachment then abandoned its last outposts within San Fernando, and on 14 March guerrillas entered the town unopposed, simultaneously continuing the attack against the Japanese in the surrounding hills.

When troops of the 33rd Division reached Bauang, the 58th IMB ordered the Hayashi Detachment to withdraw, directing it to reinforce the MLR positions at Sablan, about eight miles beyond Naguilian. Most of the Japanese unit then moved southeast over back country trails, guerrillas in pursuit, while one group, some 250 strong, attempted to withdraw south along Route 3 to Bauang

and thence east along Route 9. This group obviously did not know that the 33rd Division had occupied Bauang, with the result that it lost almost 200 men killed. During the Japanese withdrawal USAFIP(NL) units mopped up at San Fernando and by 23 March had secured the entire area.

Transition on the Baguio Front

On the same day Sixth Army directed USAFIP(NL) to institute a drive inland along Route 4 from Libtong, opening the third front in northern Luzon.10 All hope that the 33rd Division had of guerrilla aid and protection on its left rear was now gone, for on 25 March I Corps ordered Clarkson to relieve USAFIP(NL) units in the San Fernando region.11 A few days later Clarkson’s latest plans for mounting a quick drive into Baguio received the coup de grâce.12 The 32nd Division was encountering unexpected difficulty along the Villa Verde Trail and sorely needed the troops it had deployed in the Arboredo, Agno, and Ambayabang River valleys on the 33rd Division’s right. Therefore, Swift directed the 33rd Division to extend its zone east to include the Ambayabang Valley.13 With its forces now too scattered for a concerted attack toward Baguio, the 33rd Division again received orders to hold and limit its activities to patrolling – orders that were beginning to have a morale-shattering effect upon a division that was still itching to move and believed it could capture Baguio in short order.

Even as the 33rd Division was reluctantly settling back on its haunches, events were afoot that would speed the pace of operations against Baguio. General Krueger, who had been short of troops for his campaign in northern Luzon ever since late February, in late March prevailed upon GHQ SWPA to release the 129th RCT of the 37th Division from its Manila garrison duties. Krueger planned to move the RCT up to Route 9, permitting the 33rd Division to concentrate its strength on the southwestern and southern approaches to Baguio. As soon as the rest of the 37th Division could reach the Baguio front, an event Krueger expected in early April, I Corps could mount a two-division drive on Baguio. In the meanwhile the 129th RCT, attached to the 33rd Division, would help reconnoiter toward Baguio in preparation for the all-out attack.

Clarkson now planned to have the 129th RCT send a battalion reconnaissance-in-force east along Route 9. The 123rd Infantry, 33rd Division, would continue patrolling toward Baguio over the Galiano road and the Tuba Trail, while the 136th Infantry, on Route 11, would strike north toward Camp 4, almost five miles beyond Camp 2. The 130th Infantry would cover the ground on the east flank just acquired from the 32nd Division.

The Japanese opposing the reinforced 33rd Division were no longer in the shape they had been at the end of February. The 58th IMB and the 23rd Division had

both suffered heavy losses during March, losses that probably stemmed largely from lack of food and medical supplies rather than from combat action. By mid-March Japanese supply problems on the Baguio front had progressed from bad through worse to impossible. First, supplies had moved westward over the new Baguio-Aritao supply road far more slowly than anticipated, a development attributable in large measure to Allied Air Forces strikes on that road and along Route 5 north and south of Aritao. Second, operations of the 66th Infantry, USAFIP(NL), along Route 11 north from Baguio, and the activities of the 11th Infantry, USAFIP(NL), in the Cagayan Valley, had made it virtually impossible for the Japanese to bring any food into the Baguio area from the north. Third, the Japanese tried to do too much with the limited amount of supplies available on the Baguio front. They were attempting to supply 23rd Division and 58th IMB troops along the MLR; send certain military supplies north up Route 11 for the 19th Division; feed 14th Area Army headquarters and a large civilian population in Baguio; and establish supply dumps north and east of the city against the time of eventual withdrawal.14

Almost inevitably the principal sufferers were the front-line troops. By mid-March the best-fed Japanese combat troops on the Baguio front were getting less than half a pound of rice per day as opposed to a minimum daily requirement of nearly two and a half pounds. Before the end of the month the troops on the MLR were down to less than a quarter of a pound of rice a day. Starvation and diet-associated diseases filled hospitals and sapped the strength of the combat units. Generally, effective frontline strength was far lower than reported ration strength indicated. Medical supplies were consumed rapidly, and by the end of March, for example, there was virtually no malaria phophylaxis left in Baguio area hospitals.

Looking upon the situation on the Baguio front with frank pessimism, Yamashita in mid-March directed inspection of terrain north, northeast, and east of the city with a view toward preparing a new defense line. His attitude became even plainer when, on or about 30 March, he ordered Japanese civilians and the Filipino puppet government to evacuate Baguio. Indeed, the future on the Baguio front was so bleak by the end of March that almost any other army would have withdrawn to new defenses forthwith, thereby saving troops for future battle. But not so the Japanese. Yamashita decided that the existing MLR would be held until the situation became hopeless.

At the end of March that portion of the MLR held by the 23rd Division was still intact, and the 58th IMB was busy deploying additional strength along its section of the line. One independent infantry battalion was on high ground north of Route 9 at Sablan; and another held defenses at Sablan. A reinforced company was at Burgos and, less

that company, another independent infantry battalion held reserve positions at Calot, a mile and a half southeast of Sablan. One understrength battalion was responsible for defending the rough terrain from Sablan six miles south to Mt. Apni, where a tie-in was made with the right flank of the 23rd Division.

Maj. Gen. Bunzo Sato, commanding the 58th IMB, expected that the emphasis of any Allied drive in his sector would come along Route 9, but he did not neglect the other approach in his area, the Galiano road. Since the understrength battalion stationed astride the road was not strong enough to withstand a concerted attack, he directed his main reserve force, the 1st Battalion of the 75th Infantry, 19th Division, to move west out of Baguio to defenses at Asin. This step left in Baguio a reserve force of roughly three provisional infantry “battalions,” which together probably could not muster over 750 effectives.

Patrolling with limited seizures of new territory marked 33rd Division operations the last few days of March and the first week or so of April, and there were no significant changes in position in the new area taken over from the 32nd Division and on Route 11. On the Tuba Trail patrols advanced another three miles in a northeasterly direction, reporting increasingly heavy Japanese resistance and increasingly rough terrain. The story was much the same on the Galiano road, where one battalion, after reaching a point a mile east of Galiano by 30 March, was slowed by scattered but determined opposition.

As was routine by this time, the key action for the period took place on the far left, or north. Here the 129th RCT occupied Burgos on 28 March after a sharp skirmish, and by 1 April was at Salat, less than a mile short of the Japanese MLR position at Sablan. The 58th IMB hurriedly reinforced an outpost at Salat, but by 9 April the 129th RCT had broken through this position and had started to maneuver against the Japanese defenses at Sablan. In general, Japanese defenses along Route 9, the Galiano road, and the Tuba Trail still seemed unexpectedly weak and invited immediate exploitation. All that was needed to start a final drive was more strength, and that strength was forthcoming.

The Drive to Baguio

The Plans for Exploitation

By 7 April General Krueger had persuaded GHQ SWPA to release the rest of the 37th Division, less the 145th RCT, from Manila.15 He directed I Corps to go ahead with a two-division drive on Baguio as soon as the 37th Division could concentrate along Route 9. I Corps, in turn, ordered an all-out attack to begin on 12 April.

The main effort was to be made on Route 9 by the 37th Division. The 33rd Division would advance along all three approaches to Baguio in its area, placing emphasis on the Galiano road since an attack there would support the 37th Division’s action and the terrain on the Galiano approach, at least east from Asin, appeared the easiest in the 33rd

Division’s zone. The 33rd Division made its 136th Infantry, reinforced by the 33rd Reconnaissance Troop and the 2nd Battalion of the 66th Infantry, USAFIP(NL), responsible for continuing pressure along Route 11 and up the three river valleys to the east. The 123rd Infantry would push northeast over the Tuba Trail. The 130th Infantry would concentrate on the Galiano road. The 129th Infantry was to lead the 37th Division attack down Route 9, with the 148th Infantry initially held in reserve.

Despite the already evident pressure on Route 9, the Japanese, as of the second week in April, still felt that I Corps’ main effort would come along Route 11. As a result, they did not redeploy strength to counter the growing threat on their right, but instead seemed content to sit back and wait, nursing a strangely uncharacteristic defeatist attitude. Such an attitude was certainly not helped by redoubled efforts on the part of 14th Area Army headquarters to move civilians and supplies out of Baguio. What Yamashita thought about the situation was made amply clear by his personal preparations to depart for the Bambang front, an event that took place on 19 April.

As he had done earlier for the Bambang area, Yamashita set up an independent command for the Baguio front, leaving Maj. Gen. Naokata Utsunomiya, one of his assistant chiefs of staff, in charge.16 Utsunomiya also had nominal command over the 19th Division north of Baguio, a control that he was unable to exercise because of communications difficulties. The first step Utsunomiya took seems to have been to remove the 58th IMB from the control of the 23rd Division. Next, directed by Yamashita to hold Baguio as long as possible before withdrawing to a new defense line, Utsunomiya issued a tongue-in-cheek order for all troops along the existing MLR to hold out to the last man.

Getting Under Way

For the period from 12 April through the seizure of Baguio, it is possible to omit detail in tracing the operations of 33rd Division units in the Arboredo, Agno, and Ambayabang River valleys, along Route 11, and on the Tuba Trail, since these units played a relatively minor, indirect part in the capture of Baguio.17 The best the units on the east could do was defend against possible surprise counterattacks and maintain pressure by patrol action, thereby helping to pin down Japanese forces that might have otherwise been used against the main drives. On the Tuba Trail troops spent most of their time bogged down by rain, fog, incredibly bad terrain, and steady, determined Japanese resistance. Thus, neither of the 33rd Division’s two right flank regiments was able to make a direct contribution to the success of the drive on Baguio; subsequent events proved that the units on Route 11 did not even keep in place the

Japanese forces that faced them as of 12 April. Therefore, the description of the drive to Baguio of necessity centers on the operations along Route 9 and the Galiano road.

Although the two-division attack was not to start until 12 April, the 37th Division, in order to maintain momentum and contact, moved on 11 April against the Japanese known to be entrenched at and near Sablan. During the period 11-14 April the 129th Infantry broke through the Japanese defenses at Sablan in a battle marked by extremely close artillery and medium tank fire support.18 On the 14th the 148th Infantry took over and by the end of the next day had secured Route 9 through Calot. During those two days the regiment also captured many ammunition and other supply dumps that the 19th Division had left behind when it had redeployed through Baguio to the north. The Japanese had had neither the time nor the means to move these supplies north, and their loss would ultimately prove serious. Equally serious was the fact that from 11 through 15 April the 37th Division’s artillery, supporting aircraft, and attached tank units had destroyed nearly all the artillery pieces available to the 58th IMB.

Thoroughly alarmed at the unexpected speed of the 37th Division’s advance, General Sato, on 15 April, began attempts to reinforce defenses along Route 9 southeast of Calot. That day he ordered two infantry companies of his reserve forward to a barrio two miles southeast of Calot, but before the troops could reach their destination, the 148th Infantry had passed this point and moved on through Yagyagan, another mile to the southeast.

The seizure of Yagyagan was to assume considerable importance, for from that barrio a trail led southwest down steep slopes to Asin on the Galiano road. The 130th Infantry, 33rd Division, had been stalled by determined Japanese resistance west of Asin.19 If the 37th Division could secure the Yagyagan trail entrance, part of the 130th Infantry could move around to Route 9 and fall upon the Asin defenses in a neat envelopment.

To secure the trail entrance and to assure its own progress along Route 9, the 37th Division had to break through known Japanese defenses where, just a mile southeast of Yagyagan, the highway dipped across the gorge of the Irisan River. The six-day battle that ensued at the Irisan Gorge proved to be the critical action of the entire drive to Baguio. It was, indeed, one of the few cohesive actions on the Baguio front after the capture of the Routes 3-11 road junction by the 43rd Division in late January, and it serves as an example of much of the fighting on the Baguio front from late February on.

The Battle at the Irisan River

The Irisan Gorge was the best natural defensive position along Route 9 between

Irisan Gorge

Bauang and Baguio, but was only belatedly recognized as such by General Sato. Beginning on 16 April he frantically sent reinforcements to the Irisan, apparently acting under Utsunomiya’s orders to make a last desperate stand at the river. Practically every able-bodied soldier in Baguio was sent forward, troops were removed from outposts along the Arboredo, Agno, and Ambayabang Valleys, and about half the strength was taken from defenses along Route 11. All in all, the Japanese may have dispatched more than 1,500 men to the Irisan, although probably no more than one-third of that total was actually present on the battleground at one time.

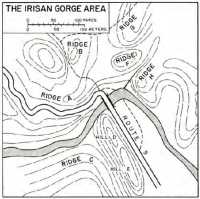

Route 9 ran generally southeast from Yagyagan and took a sharp turn eastward some 200 yards short of a destroyed bridge over the Irisan.20 Here the highway slithered around the side of the gorge under the southern and eastern slopes of a steep ridge known to the 148th Infantry as Ridge A. At the bridge site the highway took a right-angle turn to the south-southeast, crossed the river, and proceeded toward Baguio under the east side of 200-yard-long Ridge D-E. Immediately east of the bridge site the Irisan took a sharp turn corresponding to that of Route 9, both twists dominated on the northeast by steep, bare-sloped Ridge H. Along the south bank of the river – across the stream from Ridge A – lay wooded Ridge C, which was west of and at right angles to Ridge D-E. (Map 21)

Running north and northwest from the Route 9 turn at the destroyed bridge was a trail that, crossing the eastern slopes of Ridge A, passed through a slight draw about 150 yards northwest of the river. The draw was bounded on the east by Ridge B and on the west by an unnamed hill forming a northwestern high point on Ridge A. Another 150 yards east across a broad saddle from Ridge B lay Ridge G, separated from Ridge F, immediately to the south, by a sharp gully. Ridge H lay across another draw southeast of Ridge F. The trail branched just northwest of Ridge B, the west fork leading back to Route 9 a mile or so northwest of the Irisan crossing, the other striking northeast along the north side of Ridge G and ending six miles from the fork at Trinidad, a town on Route 11 about the same distance north of Baguio.

Map 21: The Irisan Gorge Area

The Japanese defenses were set up to meet a power drive along Route 9. Positions on Ridge A dominated the east-west stretch of the highway; those on Ridges F and H controlled the right-angle turn in the road at the river, as well as the bridge site; Ridge B positions overlooked the trail forking northwest of the bridge; Ridge G controlled the trail to Trinidad. Few troops were on Ridge C, since the Japanese apparently considered the terrain there too rough and wooded to be used as a route of attack toward Ridge D-E, which was well defended. The D-E position served as a backstop for defenses on other ridges, as a means to help maintain control over the crossing site, and, finally, for securing Route 9 south of the Irisan as an axis of reinforcement or withdrawal. In general, all Japanese positions in the area were of a hasty nature, with the possible exception of some caves in which antitank guns were emplaced to control the east-west stretch of Route 9. But most emplacements, especially those for machine guns, the Japanese had chosen with an excellent eye for terrain, and installations on every ridge were mutually supporting when the terrain permitted.

The 148th Infantry did not play the game according to the rules the Japanese had laid down, at least not after the morning of 17 April. That morning two companies of the 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, reinforced by medium tanks, 105-mm. self-propelled mounts, and 76-mm. tank destroyers, were bloodily repulsed in an attempt to attack along the east-west section of Route 9 just west of the bridge site. Japanese antitank fire knocked out two American tanks as they came around a nose of Ridge A at the bridge, while well-directed Japanese machine gun and small arms fire from Ridges F and H and the eastern part of Ridge A turned back the 148th Infantry’s troops. During the engagement the Japanese lost two light tanks.

In the afternoon the 148th began a series of enveloping maneuvers. First, one platoon struck directly north up the steep western slope of Ridge A from a point near that where Route 9 turned east. Under cover of this frontal assault the rest of Company F, infiltrating to the rear of Japanese positions, came in from the northwest; elements of the 1st Battalion, also driving southeast, secured the unnamed hill marking the high point of Ridge A. By dusk most of the ridge was in 148th Infantry hands, and the troops held on despite strong Japanese counterattacks during the night.

The day’s work cost the 148th Infantry about 10 men killed and 75 wounded; the Japanese lost over 100 killed. In

return for its casualties, the 148th had secured terrain from which it could control most of the east-west section of Route 9 and from which it could strike toward Ridges B, G, and F. Plans for the morrow called for the 2nd Battalion, supported by 1st Battalion fire, to seize Ridge B. The 3rd Battalion, under cover of the 2nd’s attack, would mount a wide envelopment, crossing the Irisan about 500 yards west-southwest of the bridge site and then, turning east along wooded Ridge C, ultimately fall upon Ridge D-E from the west.

Stiff resistance greeted the 2nd Battalion on 18 April, and by dusk forward elements had barely secured a foothold on the open southern slopes of Ridge B, once again demonstrating the futility of frontal attacks on Japanese positions at the Irisan Gorge. Moreover, the battalion discovered during the day that Japanese weapons on Ridge F could (and did) provide excellent support for the Japanese on Ridge B. Until the Ridge F emplacements could be neutralized, at least, the 2nd Battalion would probably get nowhere.

Operations south of the Irisan met with more success. Supported by 105-mm. self-propelled mounts and tank destroyers emplaced along Route 9 north of the river, the 3rd Battalion surprised the few Japanese who were in position along Ridge C. While mopping up along that ridge, the battalion made preparations to move on against Ridge D-E the next day.

On the morning of 19 April a heavy air strike and one artillery concentration knocked out most of the Japanese weapons on Ridge F, and another artillery concentration softened up Ridge B for two companies of the 2nd Battalion. However, progress was virtually nil until a machine gun squad, infiltrating through heavy woods, suddenly found itself in a position on the east side of Ridge B whence it could take under fire most of the Japanese defenses and defenders. This small-scale envelopment so worried the Japanese and so diverted their attention that a renewed attack from the south was successful, and the 2nd Battalion secured Ridge B before dark.

During the same morning the 3rd Battalion encountered surprisingly light opposition as it moved against Hill D, at the north end of Ridge D-E. Under cover of fire from Ridge C and Hill D, elements of Company L, moving east from Ridge C, penetrated almost to the middle of Japanese defenses on Hill E before being discovered. Apparently expecting an attack from the north, the Japanese on Hill E were so surprised by the infiltration that most of them fled southeastward along Route 9 with little attempt to hold.

With the seizure of Ridge D-E the 3rd Battalion, 148th Infantry, had overrun the Japanese backstop and had gained control of the main Japanese route of withdrawal and reinforcement. To the north the 2nd Battalion’s capture of Ridge B had equally important results. The battalion now controlled the fork in the trail just northwest of Ridge B, and could, therefore, prevent the Japanese from using the trail from Trinidad to move reinforcements to the Irisan Gorge. By this time the Japanese held only Ridges G, F, and H; Ridge F had been so worked over by air and artillery that it was no longer a strong position.

Company C took Ridge F with ease on the morning of 20 April, but Company A, trying a frontal assault on Ridge

G, was stopped on the steep western slopes. Company C then turned against the south flank of the Japanese on Ridge G, and, with this support, Company A gained the crest before noon. The rest of the day the two companies mopped up and beat off the usual determined but small-scale and un-coordinated counterattacks that followed the capture of most Japanese positions at the Irisan Gorge.

At dusk on the 20th most of the remaining Japanese in the gorge region withdrew to Ridge H, which received the full treatment from air and artillery the next morning. After the bombardment, the 1st Battalion swung against Ridge H, coming in on the north flank of the remaining defenses. The battalion cleared the ridge during the afternoon and with this action completed the breakthrough at Irisan Gorge. The surviving Japanese fled east toward Baguio or north toward Trinidad. The battle had cost the 148th Infantry approximately 40 men killed and 160 wounded; the Japanese had lost nearly 500 men killed.

Into Baguio

The final events of the drive to Baguio came rapidly. Under cover of the 148th Infantry’s operations at the Irisan, the 130th Infantry, 33rd Division, had redeployed two battalions from the Galiano road to the Yagyagan trail junction on Route 9. Attacking on the 22nd, the two battalions, coordinating their efforts with a battalion left west of Asin, opened the Galiano road by afternoon of 23 April. The 1st Battalion, 75th Infantry, was virtually annihilated during the action. The Japanese unit had taken position at Asin less than 500 strong, and it lost over 350 men killed in the defense. The 130th Infantry’s casualties were approximately 15 killed and 60 wounded.

Back on Route 9, on 22 April, the 129th Infantry relieved the 148th and that day advanced against scattered resistance as far southeast as the junction of the highway and the Galiano road. The speed and ease of this advance gave pause to I Corps and 37th Division. It seemed impossible that Route 9 could be as wide open as it appeared, and, moreover, a threat seemed to be developing on the 37th Division’s left (north) flank. The Japanese survivors of the Irisan Gorge were evidently concentrating in the Trinidad area, and from available information it also appeared that the uncommitted 379th Independent Infantry Battalion was in the same region. With a long and ill-protected line of communications back to Bauang, the 37th Division felt that it needed reinforcements to safeguard its left before it could risk sending strong forces into Baguio.

I Corps could provide no reinforcements and, on the 22nd, directed the 37th Division to hold in place. Before moving on, the 37th Division was to clear the high ground for at least a mile north of Route 9 in the area between Sablan and Irisan and set up strong blocks along the trail to Trinidad. The 33rd Division, also directed to halt, was to finish mopping up in the Asin area and then, patrolling eastward, ascertain if there were any threat to the 37th Division’s right (south) flank. Both divisions were ordered to get troops into position to launch an attack on Mt. Mirador, at the western outskirts of Baguio. Japanese thought to be holding Mt. Mirador

could not be bypassed, for they could dominate the junction of the Galiano road and Route 9 and cover much of Baguio proper with fire.21

I Corps’ precautions were unnecessary. When on 16 April General Sato had begun reinforcing his Irisan Gorge defenses, General Utsunomiya had decided to move the MLR closer to Baguio, employing the Irisan position as the northern anchor of a new line. From the Irisan the new MLR stretched south-southwest four miles to Mt. Calugong, which, controlling the Tuba Trail, was already being contested by the 123rd Infantry, 33rd Division, and the 64th Infantry, 23rd Division. The new line ran southeast from Mt. Calugong across Mt. Santo Tomas and on to Route 11 at Camp 4, two miles northeast of the earlier MLR strongpoint at Camp 3. The MLR continued east to the Ambayabang Valley from Camp 4.

Utsunomiya never established his new MLR. By evening on 22 April the Irisan anchor was gone, defenses at Asin were about to fall, and the 123rd Infantry was making tactically important gains at Mt. Calugong. It was obvious to Utsunomiya that there was no longer any sense in trying to hold, and the next morning he ordered a general withdrawal north and northeast from Baguio. A delaying force would be left near the city to cover the withdrawal, and another such force would temporarily dig in near Trinidad lest the 37th Division, driving up the Irisan-Trinidad trail, reach Route 11 north of Baguio before the general withdrawal was complete.

Once under way, the Japanese retreat was rapid. A patrol of the 129th Infantry, 37th Division, entered Baguio on 24 April, and two days later the regiment secured most of the city against negligible opposition. The Japanese holding force on Mt. Mirador was virtually wiped out between 24 and 26 April by elements of the 123rd and 130th Infantry Regiments, 33rd Division. The 123rd Infantry reached Tuba on 24 April after an unopposed march southwest from Mt. Mirador; a battalion left in the Mt. Calugong area straggled into Tuba from the west during the next two days. On 27 April patrols of the 33rd Division moved into Baguio proper from the south and southwest, making contact with the 129th Infantry and thus marking the end of the drive to Baguio.

Results of the Capture of Baguio

As a campaign to destroy Japanese, the drive to Baguio was only partially successful, because the halt I Corps ordered on 22 April had permitted General Utsunomiya to extricate some 10,000 troops from his defenses in front of Baguio and from the city proper. Given the information available to it, I Corps was undoubtedly justified in its decision to halt, although the 33rd Division, again disappointed at being forced to hold, could not but take a dim view of the order. The 33rd Division did not know that General Swift was planning to redeploy the 37th Division to the Bambang front and that he therefore could not risk involving General Beightler’s command in a major fight.

The I Corps halt order may have stemmed in part from inadequate reconnaissance by the 33rd and 37th Divisions.

A case might be made that faster, deeper, and more aggressive patrolling should have disclosed the general pattern of Japanese withdrawal at least by evening on 23 April. As events turned out, it was not until the 26th that corps and division intelligence officers were able to conclude that a Japanese retreat was definitely under way. It is also possible that the redeployment of elements of the 66th Infantry, USAFIP(NL), from the area north of Baguio to join in the attack from the south and west contributed to the delay in learning of the Japanese withdrawal. On the other hand, the guerrilla regiment had proved of great aid, especially to the 33rd Division, along the approaches to Baguio. The unit could not be every place at once.

South of Baguio the 136th Infantry, 33rd Division, did not learn until well after the event that fully half the 23rd Division forces stationed along Route 11 had redeployed to the Irisan Gorge during the period 16-22 April. Nor did the American regiment discover that the remaining 23rd Division troops on Route 11 had withdrawn through Baguio until the withdrawal was practically complete. But again, operating in the deep gorge of the Bued River, the 136th Infantry was hard put at any point in the campaign to make more than an educated guess at the strength of Japanese forces along Route 11, and the terrain was such that it was often as difficult for the regiment to knock out one Japanese machine gun nest as it would have been to destroy an entire Japanese infantry battalion.

It had, indeed, been largely the terrain problems along the routes over which it was advancing toward Baguio that had prevented the 33rd Division from making more direct contributions to the capture of Baguio during the period 12-26 April. In that fortnight the 136th Infantry had made virtually no progress. On the Tuba Trail the 123rd Infantry, whose terrain difficulties were compounded by fog and torrential tropical cloudbursts, had fought doggedly up and down knife-crested ridges where a markedly inferior Japanese force had all the advantages the terrain could provide.22 Likewise the terrain advantages enabled the 1st Battalion, 75th Infantry, to hold up the 130th Infantry in the bare-sided bowl at Asin. Ultimately, the 123rd and 130th Regiments had to complete their missions by envelopment over roads secured by the 37th Division.

However, the 33rd Division had made significant indirect contributions to the capture of Baguio. On the ground since mid-February, the division, pressing relentlessly forward whenever Sixth Army and I Corps orders permitted it to do so, had seriously weakened the 58th IMB and the 23rd Division. Moreover between 16 and 22 April the 33rd Division had kept pinned down considerable Japanese strength that might otherwise have been redeployed against the 37th Division. Certainly, it is impossible to conceive that the 37th Division’s drive could have succeeded when and as it did had not the 33rd Division also been striving for Baguio.

Since the Japanese had retired in fairly good order to new defenses in front of the Route 11 terminus of the Baguio-Aritao supply road, north of Baguio, the campaign on the Baguio front had not achieved its strategic goal, and many of the advantages accruing to Sixth Army from the seizure of the city were psychological in nature. Nevertheless, there were also important military results. Sixth Army had overrun the first of the three original anchors of the Shobu Group’s defensive triangle. Troops of the 33rd and 37th Divisions had seized tons of supplies the Japanese could ill afford to lose, had driven the Japanese farther into mountain fastnesses from which there could be no escape, and, finally, had torn holes in the ranks of the 58th IMB and the 23rd Division that the Japanese could not fill.

From late February through 27 April the 23rd Division had lost over 2,000 men killed in combat; nonbattle deaths had been much higher. When the division reassembled in new lines northeast of Baguio, it could muster no more than 7,000 troops, of whom less than half could be considered combat effectives. The first-line infantry strength of the 58th IMB was reduced to a battalion of no more than 350 troops, while the brigade’s total strength probably did not exceed 3,250, including miscellaneous attachments. The 58th IMB had lost all its artillery; the 23rd Division had only three or four guns left.

The Baguio Front, to the End of May

Between 27 April and 5 May the 37th Division secured the Trinidad area, mopped up isolated pockets of Japanese in the high ground north of Route 9, cleared Route 11 from Baguio north to Trinidad, and patrolled northeast three miles on Route 11 from Trinidad to Acop’s Place. The division encountered organized resistance only near Trinidad.23 The 33rd Division, until 5 May, mopped up along Tuba Trail and Route 11 north to Baguio, then moved on to occupy the crest of high ground two to three miles east and southeast of the city.24 The 130th Infantry, advancing by company-sized combat patrols, began marching over secondary roads to Balinguay, 7 miles east-southeast of Baguio; to Itogon, about 2 miles south of Balinguay; and to Pitican, on the Agno River 4 miles southeast of Itogon, seeking to make contact with other 33rd Division troops operating in the Agno and Ambayabang River valleys. On 5 May the last elements of the 37th Division left the Baguio area for the Bambang front, the 33rd Division taking over the areas west and north of Baguio.

With the departure of the 37th Division, the 33rd Division, much to its disappointment, again found itself with a holding mission, this one designed to secure the Baguio-Bauang-San Fernando area. The division was also responsible for establishing firm contact between its forces at Baguio and those in the Ambayabang and Agno Valleys, for patrolling ten miles northeast along Route 11 from Baguio, and for reconnoitering eastward along the Baguio-Aritao supply road from Route 11 at Kilometer

Post (KP) 21, the highway and supply road junction.25

As of 5 May the Japanese on the Baguio front, despite their losses of men and matériel during the previous two and a half months, were almost better off than they had been when fighting in front of Baguio – or they soon would be if the 33rd Division did not mount an immediate pursuit north from Baguio.26 For the time being, at least, the Japanese combat troops had more supplies than they had had for many weeks, since they could now draw on large supply dumps around KP 21 and on lesser stockpiles north up Route 11 and east along the Baguio-Aritao supply road. Moreover, because there was no immediate pursuit, the 58th IMB and the 23rd Division had some leisure to dig in across Route 11 at KP 21. The Japanese sources make it clear that had there been a pursuit before the end of the first week in May, American forces could have cut the two Japanese units to ribbons, opening wide the roads further into northern Luzon.

The 33rd Division was more than willing and, in its own opinion, quite able to go. It appears that General Swift, the I Corps commander, would have been amenable to an immediate pursuit operation, but Sixth Army had other ideas. The 33rd Division had a vast area to secure, it still had some mopping up to complete in its zone, some of its units badly needed rest and time for rebuilding, it had an enormous reconnaissance responsibility, and the possibility existed that the division might become involved in a major fight for which it had insufficient strength. Sixth Army planned to employ the 33rd Division in the invasion of Japan and therefore wanted to withdraw the unit from active combat as soon as possible. Finally, Sixth Army as yet had little information about the Japanese situation north and northeast from Baguio – the first job on the Baguio front would be to regain the contact lost with the Japanese after 23 April. Whatever the case, Sixth Army made no provision to secure the most important military objective on the Baguio front, the Route 11 terminus of the Baguio- Aritao supply road. This was unfortunate, for although Sixth Army did not know it, Route 11 on 5 May was clear from Baguio to Acop’s Place, about four miles short of KP 21, and the Japanese holding at KP 21 were by no means prepared to withstand a sudden, strong attack.

As events turned out, the 33rd Division’s operations to late May were limited to minor local gains and long-range reconnaissance. The only action of significant proportions occurred along a trail connecting Santa Rosa, in the Ambayabang Valley, to Tebbo, on the Agno five miles south of Pitican. There, the 33rd Division directed its energies toward clearing Japanese off high ground between the main trail and the upper reaches of the Ambayabang. A battalion of the 130th Infantry, coming south from Baguio via Pitican, reached Tebbo on 9 May, finding the barrio abandoned. On 5 May the 136th Infantry had begun an advance up the Ambayabang and, three miles south of Tebbo, became involved in a ten-day fight that led only

to the killing of a couple of hundred Japanese who constituted no threat to the 33rd Division and whose principal mission was to block the Ambayabang Valley against any American attack toward the Baguio-Aritao supply road from the south.

With the rainy season coming on, I Corps and the 33rd Division had long since abandoned plans to employ the valley as a route of advance toward the Japanese supply link, and the 136th Infantry gave up the terrain it had gained along the valley and the trail to Tebbo almost as soon as it had won the ground. On 15 May all 33rd Division troops began withdrawing. Extricating the men, supplies, and equipment proved no mean feat, for by the time the withdrawal was well under way rains had turned the Pitican–Tebbo trail and trails in the Ambayabang Valley into quagmires. The final destruction of the Japanese blocking force in the valley had no bearing upon I Corps or Shobu Group plans or dispositions, and the Japanese soon replaced their outposts.

For the rest, by the end of May the 33rd Division was executing its reconnaissance missions without significant contacts or major advances. Restively holding, the division was forced to await developments on the Bontoc and Bambang fronts before Sixth Army would permit it to launch a new drive deeper into the mountains of northern Luzon.