Chapter 31: The Central Visayan Islands

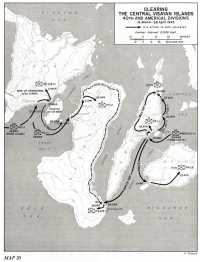

Well before organized Japanese resistance in the Zamboanga-Sulu region had collapsed, Eighth Army had initiated operations to secure the central Visayan Islands. In fact, 41st Division troops had scarcely crossed the Zamboanga coastal plain when, on 18 March, the 40th Infantry Division landed on Panay Island to begin a campaign to secure Panay, smaller offshore Guimaras Island, and the northern section of Negros Island, east across Guimaras Strait from Panay. (See map, p. 20.)

Panay and Guimaras

The reinforced 40th Division (less the 108th RCT, which moved to Leyte) staged at Lingayen Gulf for the Panay–Guimaras–northern Negros operation.1 The forces for Panay included 40th Division headquarters, the 185th RCT, the 2nd Battalion of the 160th Infantry, most of division artillery, and normal combat and service attachments. The groupment left Lingayen Gulf on 15 March aboard vessels of Task Group 78.3, Admiral Struble commanding, and reached Mindoro the next day. There, a group of 542nd Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment landing craft (mostly LCMs) from Leyte joined. Taking the engineer craft in tow, Task Group 78.3 made an uneventful voyage to Panay and was in position off selected landing beaches on the southeast coast before dawn on 18 March.

Following a brief destroyer bombardment, the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 185th Infantry, landed unopposed about twelve miles west of Iloilo, principal city of Panay and third largest commercial center in the Philippines. The beach bombardment was unnecessary – the first assault wave was greeted on shore by troops of Colonel Peralta’s guerrilla forces, drawn up in parade formation and “resplendent in starched khaki and shining ornaments.”2 Numbering over 22,500 men, about half of them armed, the Panay guerrillas controlled much of their island. GHQ SWPA had sent supplies to Peralta by submarine, had relayed some by small craft through Fertig’s guerrillas on Mindanao, and, after the landing on Leyte, had flown supplies to guerrilla-held airfields on Panay. Engaged primarily in intelligence work until the invasion of Leyte, the guerrillas had expanded their control

in late 1944, when over half the original Japanese garrison went to Leyte.

In March 1945 about 2,750 Japanese were on Panay, including 1,500 combat troops and some 400 civilians. The principal combat units were the 170th Independent Infantry Battalion of the 102nd Division and a company each from the 171st and 354th IIB’s, same division. The remainder of the garrison consisted of Air Force service personnel.

Most of the Japanese, commanded by Lt. Col. Ryoichi Totsuka, who was also commander of the 170th IIB, were stationed at or near Iloilo. Totsuka planned to defend the Iloilo area and its excellent harbor and airfield facilities for as long as possible, but he had no intention of presiding over the annihilation of his force in a battle he knew he could not win. Therefore he decided to withdraw to the rough mountains of south-central Panay as soon as he felt his Iloilo defenses were no longer tenable. Avoiding contact with U.S. forces, he would attempt to become self-sufficient in the mountains, where he anticipated he could hold out almost indefinitely. Whether Totsuka knew it or not, his plan was strikingly similar to that executed by Col. Albert F. Christie’s Panay Force in April 1942. The Fil-American garrison on Panay in 1942 had withdrawn troops and equipment into the mountains and successfully held out until directed to surrender.3

The 185th Infantry rapidly expanded its beachhead on 18 March 1945 against light, scattered resistance, and during the afternoon started along the coastal road toward Iloilo. By dusk the next day Colonel Totsuka had concluded that further resistance would be pointless and accordingly directed his forces to begin their withdrawal that night. Breaking through an arc of roadblocks that guerrillas and the 40th Reconnaissance Troop had established, the Japanese made good their escape, and by 1300 on 20 March the 185th Infantry was in complete control of Iloilo. (Map 30)

The Japanese withdrawal decided the issue on Panay. The 40th Division, estimating that only 500 Japanese in disorganized small groups remained on Panay, mounted no immediate pursuit, and it was not until April and May that Fil-American forces launched even minor attacks against the Japanese concentrations. The guerrillas and the 2nd Battalion, 160th Infantry, which assumed garrison duties on Panay on 25 March, never closed with Totsuka’s main body, and at the end of the war Totsuka came down out of the mountains to surrender approximately 1,560 men, over half his original garrison. U.S. Army casualties on Panay to late June, when control passed to Colonel Peralta, numbered about 20 men killed and 50 wounded.

Operations to clear Guimaras Island began as soon as the 185th Infantry secured Iloilo, and on 20 March 40th Division patrols found no signs of Japanese on the island. Next, men of the 185th took tiny Inampulugan Island, off the southeastern tip of Guimaras. The Japanese on Inampulugan, who manned a control station for electric mines in Guimaras Strait, fled without offering resistance when the Americans landed.

Map 30: Clearing the Central Visayan Islands, 40th and Americal Divisions, 18 March-28 April 1945

Panay coastal plain opposite Guimaras Island. Iloilo City, upper left; airstrip in foreground

Base development on Panay was rather limited. Engineers repaired an existing airfield at Iloilo for supply and evacuation planes, but kept additional construction to that required in order to mount a reinforced division for the invasion of Japan. The 40th Division was to mount at Panay for the initial assault on the Japanese home islands, and the 5th Infantry Division, upon redeployment from Europe, was to stage at Iloilo for subsequent operations in Japan.4

Northern Negros

On 24 March General Eichelberger, the Eighth Army’s commander, decided that operations on Panay had proceeded to the point where the 40th Division could move against northern Negros and set 29 March as the date for the new attack.5 The 185th RCT would make the assault; the 160th RCT (less the 2nd

Battalion, 160th Infantry) would follow on 30 March.6 The 503rd Parachute RCT, staging at Mindoro, would jump to reinforce the 40th Division upon orders from Eighth Army. Eighth Army reserve for the operation was the 164th RCT, Americal Division, on Leyte. The 40th Division could expect help from Negros guerrillas under Colonel Abcede since, with about 14,000 troops, over half of them armed, Abcede controlled two-thirds of the island.

Lt. Gen. Takeshi Kono, commander of the 77th Infantry Brigade, 102nd Division, had around 13,500 men in northern Negros.7 Another 1,300 Japanese were concentrated at the southeast corner of the island but, tactically unrelated to Kono’s force, reported to a headquarters on Cebu. Kono commanded about 5,500 men of the 102nd Division, 7,500 troops of the 4th Air Army’s 2nd Air Division, and 500 naval personnel. The trained combat effectives, about 4,000 in all, were from the 102nd Division.8

Kono’s troops lacked many essential items of supply. For example, less than two-thirds of his men were armed – he had only 8,000 rifles. Small arms ammunition was far from adequate; food, assuming no losses, could last for little more than two months. On the other hand, in some respects the Japanese were very well armed. Home of the 2nd Air Division, northern Negros had bristled with antiaircraft weapons, which Kono could use for ground operations. Kono’s troops had also remounted numerous automatic weapons taken from 2nd Air Division planes destroyed or damaged on the northern Negros fields.

Like Japanese commanders elsewhere in the Philippines, Kono did not plan to defend the most important ground under his control, the airfield area of the northwestern Negros coastal plain. He intended to withdraw into the mountains of north-central Negros for a long stand, leaving only token forces behind in the coastal plain to delay American penetrations and to destroy bridges and supplies. In late March, accordingly, the bulk of his forces were on their way to inland positions, but unfortunately for Kono he was unable to take many of the larger antiaircraft guns with him.9 Kono’s first defense, an outpost line of resistance, extended along the foothills of the mountains generally seven miles inland (east) from Bacolod, twenty-five miles east across Guimaras Strait from Iloilo. His main defenses lay five to six miles deeper into the mountains.

90-mm. antiaircraft gun firing ground support, northern Negros

The 40th Division’s first landing on Negros took place about 0500 on 29 March when a reinforced platoon of Company F, 185th Infantry, went ashore unopposed in the vicinity of Pulupandan, fifteen miles south of Bacolod. The platoon moved directly inland about three miles to secure a bridge over the Bago River, a bridge that provided the best and closest means of egress from the Pulupandan area to the Bacolod region. Clashing sharply with Japanese bridge guards, the platoon seized the Bago span before the guards, caught by surprise, could set off prepared demolitions. The platoon then held the bridge against minor counterattacks until relieved about 0930 by the main body of the 185th Infantry. The 185th had begun landing at Pulupandan about 0900. There was no preliminary naval bombardment and there was no Japanese resistance.

Spreading northward and eastward the 185th Infantry, which the 160th followed, secured almost the entire coastal plain of northwestern Negros by noon on 2 April at the cost of approximately 5 men killed and 10 wounded. By evening on the 8th the two regiments had

overrun the Japanese OPLR and were readying an attack toward Kono’s inner fortress. Meanwhile, no need for the 503rd Parachute Infantry to jump on Negros having developed, the regiment had flown from Mindoro to Panay and moved to Negros aboard small craft. Assembling to the left of the 185th Infantry (the 160th was now on the 185th’s right), the parachute regiment prepared to participate in the attack against Kono’s main defenses.

Launching a general offensive on 9 April, the three regiments drove slowly into rugged terrain where the Japanese had every defensive advantage. Kono’s men had prepared cave and bunker positions, most of them mutually supporting and many connected by tunnels or trenches. The Japanese had dug tank traps along all roads and trails in the mountains, and had also laid mine fields using aerial bombs. Kono’s men had excellent observation, for most of the hills in their last-stand area were open, grass covered, and steep sided. During daylight, the Japanese were content to conduct a static defense, but they undertook harassing attacks almost every night.

Little purpose can be served by describing in detail the mountain fighting in northern Negros. The battle soon degenerated into mountain warfare of the roughest sort involving all the problems, frustrations, delays, failures, and successes that American troops were encountering in the mountains of Luzon. The 40th Division employed air and artillery support liberally,10 but in the end, as on Luzon, had to close with each individual Japanese position with flame throwers and the rifle-carrying infantrymen. As the campaign wore on, weather also became a factor with which the 40th Division had to reckon, for dense fogs and heavy rains slowed all operations.

By 2 June the 40th Division had overrun almost the last strong, organized Japanese resistance in northern Negros. On the 4th General Kono, realizing that his remaining forces were incapable of further sustained effort, directed a general withdrawal deep into the mountains behind his broken defensive lines. The surviving Japanese dispersed into small groups seeking food and hideouts and trying to avoid contact with Abcede’s guerrillas who, under the direction of the 503rd Parachute RCT, took over responsibility for the pursuit of Kono’s men. On 9 June the 503rd relieved all elements of the 40th Division in northern Negros. By that date the Japanese had lost over 4,000 men killed. Kono lost another 3,350 troops, mainly from starvation and disease, before the end of the war. After the general surrender in August 1945, over 6,150 Japanese came down from the mountains to turn themselves in, joining about 350 others who had been captured earlier. In all, about 7,100 Japanese lost their lives in northern Negros, pinning down the equivalent of an American infantry division for

over two months. The 40th Division’s casualties for the operation, including those of the attached 503rd Parachute RCT, totaled approximately 370 men killed and 1,035 wounded.

Cebu

The Plan and the Japanese

The 40th Division had not begun the third phase of its campaign to secure Panay, Guimaras, and northern Negros when, on 26 March, the Americal Division launched a three-part operation of its own to clear Cebu Island, east of Negros; Bohol Island, southeast of Cebu; and the southern section of Negros Island.

While primarily designed to clear Filipino real estate and liberate Filipinos from the Japanese yoke, the Cebu operation was also executed to secure an additional staging base for the assault on Japan. Cebu City, on the east-central shore of the 150-mile-long island, is the second largest city of the Philippines and boasts port facilities second only to those of Manila. GHQ SWPA planned to develop at Cebu staging facilities adequate to mount a corps of three reinforced divisions: the Americal Division, and, upon their redeployment from Europe, the 44th and 97th Infantry Divisions.11 Airfield development on Cebu would be limited to that required to provide a small base for transport and evacuation aircraft.

For the assault on Cebu the Americal Division (less the 164th RCT, held out as Eighth Army Reserve) staged at Leyte and moved to the objective aboard vessels of Task Group 78.2, Capt. Albert T. Sprague commanding.12 With normal combat and service unit attachments, the Americal Division numbered nearly 14,900 men. The division proper was understrength, and, having recently moved down out of the mountains of northwestern Leyte, received few if any replacements before staging for Cebu. Already tired from arduous mopping-up operations on Leyte, the division received only the rest its hurried loading operations afforded.

Maj. Gen. William H. Arnold, commanding the Americal, expected considerable help from Cebu guerrillas under Colonel Cushing, who had about 8,500 men in his group. Before the Americal Division landed, Cushing was to attempt to secure the Cebu City water sources, located in rough hills three miles west-northwest of the city. After the assault, the Americal would provide Cushing with arms and other military equipment and employ the guerrillas to the maximum.

There was good reason for Arnold to hope for guerrilla aid. Lacking one RCT of his division, Arnold expected to encounter around 12,250 Japanese on Cebu, an estimate quite close to the actual strength – 14,500 – of the Japanese

garrison.13 Roughly 12,500 Japanese were deployed in and near Cebu City, while another 2,000 held positions in far northern Cebu. Trained ground combat strength was low. At Cebu City there were less than 1,500 Army ground combat troops, most of them members of the reinforced 173rd IIB, 102nd Division.14 Naval ground combat strength at Cebu City totaled 300 men, all from the 36th Naval Guard Unit, 33rd Naval Special Base Force. In northern Cebu the combat element numbered about 750 men of the 1st Division, who had recently arrived from Leyte. Finally, the 14,500 Japanese on Cebu included about 1,700 noncombatant civilians.

In late March 1945, the Japanese command structure on Cebu was in a somewhat confused state. Lt. Gen. Shimpei Fukue, commander of the 102nd Division, was present but had been relieved of his command by General Sosaku Suzuki, the 35th Army commander, for leaving Leyte without permission. Until 24 March, only two days before the Americal Division landed, all Japanese in the Cebu City region had nominally been under control of Rear Adm. Kaku Harada, commanding officer of the 33rd Naval Special Base Force. Harada chose not to exercise all his authority and left defensive preparations largely in the hands of Maj. Gen. Takeo Manjome, commander of the 78th Infantry Brigade, 102nd Division. The northern Cebu groupment, independent of both Harada and Manjome, was under Lt. Gen. Tadasu Kataoka, Commanding General, 1st Division.

General Suzuki, when he reached Cebu from Leyte on 24 March, immediately took steps to centralize the command. Assuming control of all forces on Cebu, Suzuki made General Manjome de jure commander in the Cebu City region and left Kataoka in control in northern Cebu. At the end of the month Suzuki went north to prepare for his ill-fated attempt to escape to Mindanao,15 leaving Manjome complete discretion in the Cebu City sector. Manjome’s command also embraced Japanese forces on Bohol Island and southern Negros.

Manjome designed his defenses so as to control – not hold – the coastal plains around Cebu City, and for this purpose set up defenses in depth north and northwest of the city. A forward line, constituting an outpost line of resistance, stretched across the first rising ground behind the city, hills two and a half to four miles inland.16 A stronger and shorter second line, the main line of resistance, lay about a mile farther inland and generally 350 feet higher into the hills. Back of this MLR were Manjome’s last-stand defenses, centering in

rough, broken hills five miles or so north of the city. Anticipating that American forces would attempt to mount wide envelopments of his defensive lines, Manjome set up one flank protective strongpoint in rugged, bare hills about three and a half miles north of barrio Talisay, on the coast about six miles southwest of Cebu City, to block the valley of the Mananga River, a natural axis of advance for forces enveloping from the south and west. Similarly, he established strongpoints on his left to block the valley of the Butuanoan River, roughly four miles northeast of Cebu City. Against the eventuality that the American invading forces might land north of Cebu City and strike into the Butuanoan Valley, Manjome set up another flank protective position in low hills overlooking the beach at Liloan, ten miles northeast of Cebu City.

General Manjome did not intend to hold the beaches, but at both Talisay and Liloan, the best landing points in the Cebu City region, he thoroughly mined all logical landing areas. The Japanese also constructed tank barriers along the shore line and planted tank traps and mine fields along all roads leading inland and toward Cebu City. The inner defense lines were a system of mutually supporting machine gun positions in caves, pillboxes, and bunkers. Many of these positions had been completed for months and had acquired natural camouflage. Manjome’s troops had an ample supply of machine guns and machine cannon and, like the Japanese on Negros, employed remounted aircraft and antiaircraft weapons. Manjome had some light and heavy mortars, but only a few pieces of light (70-mm. and 75-mm.) artillery. For the rest, however, Manjome’s forces were far better supplied than Kono’s troops in northern Negros.

The Cebu City Coastal Plain

The Americal Division encountered some problems at Cebu that merit special attention, meeting the first at Talisay, site of the assault beaches. Following an hour’s bombardment by three light cruisers and six destroyers of Admiral Berkey’s Task Force 74, leading waves of the 132nd and 182nd Infantry Regiments, aboard LVTs, landed unopposed on beaches just north of Talisay at 0830 on 26 March. (Map 31) Within minutes confusion began to pervade what had started out to resemble an administrative landing. Japanese mines, only a few yards beyond the surf line, knocked out ten of the leading fifteen LVTs. Troops in the first two waves halted after about 5 men were killed and 15 wounded from mine explosions, and as subsequent waves came ashore men and vehicles began jamming the beaches.

Colonel Cushing had reported the existence of mine fields at Talisay, and the Americal Division had sent engineer mine disposal teams ashore with the first waves. The mine fields proved much more extensive than anticipated and the mines themselves quite a problem. The Japanese had placed 50-kilogram (111-pound) aerial bombs under most of the mines and when these blew they tore LVTs apart and left huge holes in the beach. Appalled by the nature of the explosions, the leading troops were also surprised at how thickly the Japanese had sown the mines, as well as by the fact that the preassault naval bombardment had not detonated the bulk of them. The effect was the more serious

Map 31: Clearing the Cebu City Area, Americal Division. 26 March-18 April 1945

Landing at Cebu

because the troops had had no previous experience with an extensive and closely planted mine field. Another element of surprise that helped, paradoxically, to halt the troops on the beaches was the complete absence of Japanese resistance. Had a single Japanese machine gun opened fire, it is probable that the leading troops would have struck inland immediately, mines or no mines.

Brig. Gen. Eugene W. Ridings, Assistant Division Commander, found movement at a complete standstill when he came ashore with the second wave. Feeling that commanders already ashore had failed to employ the means available to them to clear the mine fields or to find a way through them, General Ridings set men of the 132nd Infantry to work probing for and taping routes through the obstacles. This work was under way by the time the last boats of the third wave reached the beach, but it was nearly 1000 before beach traffic was completely unjammed and the advance inland had fully developed.

The air and naval preassault bombardments had not destroyed all the Japanese defensive installations in the Talisay area. Had Japanese manned the positions that remained intact, Americal Division casualties, given the stoppage on the beaches, might well have been disastrous. Luckily for the division, Japanese tactical doctrine at this stage of the war called for withdrawal from the beaches to inland defenses. The few outposts left in the Talisay area evidenced

Cebu City

no stomach for sitting through the naval bombardment and had fled when Task Force 74 opened fire. The Japanese had missed an almost unparalleled opportunity to throw an American invasion force back into the sea.

Once past the beach mine fields, the Americal Division’s leading units probed cautiously through abandoned defenses as they advanced inland to the main highway to Cebu City. Encountering only one delaying force during the day, the main bodies of the 132nd and 182nd Infantry Regiments nevertheless halted for the night about a mile and a half south of the city. Patrols entered the city before dark but did not remain for the night. The next day the infantry secured Cebu City against no opposition and on the 28th moved to clear Lahug Airfield, two miles to the northeast.

While maneuvering to take the airfield, the Americal Division encountered its first strong, organized resistance. Initially, this took the form of machine gun and mortar fire directed against the left of troops moving toward the airfield, but during the afternoon forward elements discovered that Hill 30 and Go Chan Hill, close together a mile north of Cebu City, were infested with Japanese. The 182nd Infantry seized Hill 30 after a sharp fight on 28 March and on the next morning launched an attack to clear Go Chan Hill, half a mile to the east. The regiment made some progress during the morning of 29 March, but Japanese machine gun and rifle fire continued

to pour down, unabated, along all slopes of the hill. The assault battalion prepared to withdraw from Go Chan to permit air and artillery to give the objective a thorough going-over, but at this juncture the Japanese, by remote control, blew an ammunition dump located in caves along an eastern spur of the hill. In the resulting explosions Company A, 182nd Infantry, lost 20 men killed and 30 wounded; Company B, 716th Tank Battalion, lost one tank and crew and suffered damage to two more tanks. The infantry company, already understrength as the result of long service on Leyte, ceased to exist, and the regiment distributed its survivors among Companies B and C.

In a revengeful mood almost the entire 182nd Infantry returned to the attack on 30 March. All available tanks, artillery, and mortars provided support, and the 40-mm. weapons of the 478th Antiaircraft Automatic Weapons Battalion joined in. By dusk the 182nd had cleared all Go Chan Hill.

Meanwhile, the 132nd Infantry had cleared the coastal plains area north to the Butuanoan River. West of Cebu City, since Cushing’s guerrillas had failed to clear the terrain, the 132nd moved to secure the city’s water supply sources. The fighting for four days was bitter, and it was not until 2 April that the 132nd had made the water supply facilities safe. Unopposed, troops of the 132nd Infantry had meanwhile landed on Mactan Island, two miles east across Cebu Harbor from Cebu City.17 Japanese fire from the hills overlooking Lahug Airfield on the Cebu mainland had made it impossible for engineers to work at the Lahug site, and Eighth Army had accordingly directed the Americal Division to seize a strip on Mactan. The strip was operational for transport planes by 2 April, meeting the immediate airfield requirements for the Cebu operation.

The Main Defenses

By the end of March the Americal Division had acquired a good idea of the nature and extent of General Manjome’s principal defenses, and had learned that it had already overrun some of the strongpoints along the Japanese OPLR. On the other hand, the division had not been able to pinpoint the Japanese flanks. With the enemy firmly entrenched and having all the advantages of observation, General Arnold knew that the process of reducing Manjome’s positions would be slow and costly no matter what type of maneuver the Americal Division employed. Lacking the strength required for wide envelopments and specific information about the Japanese flanks, Arnold hoped he might achieve decisive results with a single sledgehammer blow against the Japanese center. He therefore decided to use the bulk of his strength in a frontal assault into the hills due north of Cebu City.

This attack the 182nd Infantry launched on 1 April, and by the 11th the regiment had reduced almost all the important defensive installations along the center of Manjome’s second line. Meanwhile, General Arnold had moved most of the 132nd Infantry against the Japanese left. Striking up the west bank of the Butuanoan River and then west from that stream, the 132nd, by 11 April, actually turned the Japanese left and

reached a point on the extreme left of Manjome’s last-stand positions. But the Americal Division, still lacking information on Japanese dispositions in the hinterland, did not recognize the significance of the 132nd Infantry’s gains and made no immediate provision to exploit the success.

Casualties during the attacks between 1 and 12 April were quite heavy, and as early as the 3rd General Arnold had concluded that he was not going to realize his hopes for quick breakthrough in the Japanese center. He decided that success at a reasonable cost and within a reasonable time required a wide envelopment – as opposed to the 132nd Infantry’s more or less frontal attack on the Japanese left – and for this purpose he asked General Eichelberger to release the 164th RCT from Eighth Army Reserve and dispatch it to Cebu. Arnold planned to have the 164th Infantry envelop the Japanese right and right rear via the Mananga River valley. Guerrillas would screen the regiment’s movement with operations off the east bank of the Mananga while the 132nd and 182nd Infantry Regiments would concentrate on the Japanese left, undertaking maneuvers the Japanese would interpret as presaging a major attack from the Butuanoan River. (The 132nd Infantry’s attack up that river had in large measure been tied to this deception plan.) Finally, Arnold directed the 182nd Infantry to employ part of its strength in a holding attack against the Japanese center.

The 164th Infantry, less one battalion, reached Cebu on the 9th and started up the Mananga Valley during the night of 11-12 April. Halting throughout the 12th, the regiment then swung northeast and during the night of 12-13 April moved into position about a mile northwest of the major strongpoint on the right rear of Manjome’s last-stand area. Hoping to achieve surprise, the 164th attacked on the morning of 13 April without preliminary artillery bombardment. The Japanese, however, reacted quickly and strongly. The American unit soon lost the element of surprise, and by the end of the day found its outflanking thrust evolving into another frontal assault.

Meanwhile, the 132nd and 182nd Infantry Regiments had resumed their attacks. The 182nd succeeded in overrunning the last strongpoint along the Japanese second line, but the 132nd Infantry had made no significant gains by 13 April. All three regiments of the Americal Division now settled down to a series of costly, small unit attacks during which they gained ground painfully, yard by yard, behind close artillery and air support. Finally, on 17 April, organized resistance in the Japanese last-stand area began to collapse, and by evening that day the division had reduced all of Manjome’s major strongpoints. The end of organized resistance in the hills north of Cebu City came on the 18th.

On 16 April the Americal Division had estimated that Manjome could hold out in his last-stand area for at least another two weeks, and the sudden collapse of organized opposition came as something of a surprise. Unknown to the Americal Division, Manjome had decided about 12 April that further resistance would be futile and had directed a general withdrawal northward to begin during the night of 16-17 April. By the morning of the 17th the withdrawal was well under way, and some 7,500 men managed to extricate themselves in fairly

good order. Manjome left behind large stores of ammunition, weapons, and food and also lost a good many troops as they ran through a gantlet of 132nd Infantry outposts.

After the war one Japanese survivor of the fighting on Cebu, Col. Satoshi Wada, the 102nd Division’s chief of staff, ventured the opinion that the Americal Division had been inordinately slow in mounting envelopments. He believed the frontal attack in the center had been wasteful of time and lives and that the Americal would have done better to execute an early, strong envelopment of the Japanese left via the Butuanoan Valley. He felt that the Mananga River envelopment, on the Japanese right, had started too late and had been too weak to achieve much significance. It appears, indeed, that the Mananga Valley maneuver accomplished little more than to speed Japanese preparations for withdrawal in accordance with plans Manjome had made before the Americal Division ever reached Cebu.

Colonel Wada’s hindsight analysis leaves at least three important factors out of consideration. First, until 9 April General Arnold had only two RCTs on Cebu. With these he not only had to execute an attack but also had to protect and secure the Cebu City coastal area, clear Mactan Island, and guard against the possibility of a Japanese counterattack. Arnold, accordingly, did not feel he had sufficient strength to mount wide envelopments. Second, the Americal Division had not undertaken an envelopment of the Japanese left via the Butuanoan Valley because, until almost mid-April, it had not been able to ascertain just where the Japanese left was anchored – which may reflect adversely on the depth of 132nd Infantry reconnaissance. In any case, the terrain on the Japanese left hardly invited concerted attack. Finally, the Americal Division had feared that the Japanese at Liloan (a force actually comprising some 1,500 ill-armed service troops) might strike the exposed right flank of units pushing up the Butuanoan Valley. It is true, however, that the envelopment via the Mananga Valley did not turn out as successfully as anticipated and that failure to push the attack via the Butuanoan Valley allowed a large Japanese force to escape relatively intact into northern Cebu.

Mop-up on Cebu

Following the collapse of Japanese resistance in the hills north of Cebu City, the Americal Division quickly set up a pursuit operation, but had a difficult time finding out where Manjome’s forces had gone. Moving over mountain trails and through unmapped terrain, Manjome at first hoped that he might somehow evacuate the bulk of his troops to northern Negros. Quickly realizing this hope futile, he endeavored to join forces with 1st Division remnants in northern Cebu. Here again Manjome’s hopes were frustrated, for the Americal Division cut his line of march.

The division’s pursuit began on 20 April when elements of the 132nd Infantry, moving by small craft, landed on the east coast seventeen miles north of Cebu City. Eight days later the regiment had cleared the coastal highway for thirty-five miles north of the city. The 182nd Infantry, meanwhile, had marched overland to Cebu’s west coast, swung back east over an east-west road crossing the

northern section of the island, and made contact with the 132nd on 28 April. The two regiments had thus split the 1st and 102nd Division forces.

At the end of the first week of May the 132nd Infantry began a drive to break up organized resistance on the part of the 1st Division groupment and, with guerrilla aid, largely accomplished its task in a campaign lasting to the end of the month. During early June the bulk of the 132nd and 182nd Infantry Regiments, reinforced by two newly equipped guerrilla regiments, turned south against the 102nd Division’s groupment, which had holed up in wild, mountainous country in the north-central portion of the island. In two weeks’ time the Fil-American units destroyed the last effective Japanese resistance, and the remaining Japanese broke up into small groups seeking only to survive. By 20 June most of the Americal Division, withdrawing from action to prepare for the invasion of Japan, left further patrolling to Cushing’s guerrillas.

The Americal Division estimated that it killed nearly 9,000 Japanese on Cebu from 26 March to 20 June. This figure seems exaggerated, for after the surrender in August 1945 over 8,500 Japanese turned up alive on Cebu.18 It therefore appears that roughly 5,500 Japanese lost their lives on Cebu from 26 March to the end of the war. The Americal Division, defeating a military force of approximately its own size – the division was considerably outnumbered by the Japanese until the 164th RCT reached Cebu on 9 April – had suffered battle casualties totaling roughly 410 men killed and 1,700 wounded. In addition, the division had incurred over 8,000 nonbattle casualties, most resulting from an epidemic of infectious hepatitis. Other tropical diseases also took a toll, and toward the end of the operation, according to the Eighth Army’s surgeon, relaxed discipline on Cebu led to an increase in malaria and venereal diseases.19

Bohol and Southern Negros

A week before Japanese resistance collapsed north of Cebu City, the Americal Division, pressed by General Eichelberger to speed its three-phase campaign to clear Cebu, Bohol, and southern Negros, had sent a battalion combat team of the 164th RCT to Bohol Island.20 On 11 April the battalion landed unopposed over beaches already controlled by guerrillas under Major Ingeniero. Patrols of the 164th Infantry on 15 April discovered the main body of the Japanese along low hills seven or eight miles inland from the center of Bohol’s south coast. The Japanese force, built around a company of the 174th IIB, 102nd Division, numbered about 330 men in all. In a series of attacks lasting from 17

through 20 April the 164th Infantry’s battalion broke the back of Japanese resistance; it overran the last organized opposition by the 23rd. Most American forces withdrew from the island on 7 May, leaving the mop-up to Major Ingeniero’s guerrillas and a detachment of the 21st Reconnaissance Troop, Americal Division. As of that date about 105 Japanese on the island had been killed; the 164th Infantry had lost 7 killed and 14 wounded. About 50 men of the Japanese garrison, harried and hunted, survived to surrender at the end of the war.

While one battalion of the 164th was securing Bohol, the rest of the regiment moved to southern Negros, where it landed unopposed on 26 April. Almost immediately after landing the 164th Infantry made contact with elements of the 40th Division’s 40th Reconnaissance Troop, which had rounded the north coast of the island and had sped down the east coast without encountering any Japanese. The 164th Infantry then turned to the task of locating and dispersing the small Japanese garrison of southern Negros. Totaling about 1,300 men, this garrison was built around the 174th IIB, less three rifle companies, and included ground service troops of the 2nd Air Division as well as about 150 seamen from ships sunk in the Mindanao Sea during late 1944.

By 28 April the 164th Infantry had located the main force of Japanese in rough, partially jungled hills about ten miles inland. The Japanese repelled the first attacks, which one battalion of the 164th launched, and on 6 May all available strength, including a guerrilla regiment, began a new, concerted offensive. By 17 May the Japanese were withdrawing from their best defenses, but it was the 28th before the 164th Infantry and attached guerrillas overran the last organized resistance at the Japanese stronghold. The regiment reduced a final pocket of Japanese opposition between 7 and 12 June, and by the 14th could find no further signs of organized resistance.

On 20 June the last elements of the 164th Infantry left southern Negros, and a company of the 503rd Parachute Infantry came down from northwestern Negros to control the guerrillas and help hunt the remaining Japanese. The southern Negros operation cost the 164th Infantry roughly 35 men killed and 180 wounded, while the Japanese, to 20 June, lost about 530 men killed and 15 captured. As it left Negros, the 164th Infantry estimated that not more than 300 Japanese were left alive in the southern part of the island, but after the war about 880 Japanese came out of the southern hills to surrender.

Conclusions

The end of organized Japanese resistance in southern Negros marked the completion of Eighth Army’s campaign to recapture the central Visayan Islands. During that campaign the reinforced Americal and 40th Divisions (the latter less its own 108th RCT but with the 503rd Parachute RCT attached) had faced approximately 32,350 Japanese, of whom 8,500 can be counted as trained combat effectives. By 20 June the two U.S. divisions had lost some 835 men killed and 2,300 wounded; as of the same date Japanese losses were approximately 10,250 killed and 500 captured. Perhaps another 4,000 Japanese were

killed or died of starvation and disease from 20 June to 15 August 1945, but almost 17,500 of the original 32,350 survived and surrendered after the end of the war.

The collapse of organized opposition on Panay, Cebu, Bohol, and Negros did not complete Eighth Army’s job in the southern Philippines. In fact, even as the Americal and 40th Divisions were finishing up their tasks on the central Visayans, other units of Eighth Army were heavily engaged against the strongest and most effective Japanese concentration in the southern islands, that holding eastern Mindanao.