Part 3: Objective: Schmidt

The story of the 112th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division in the battle for Schmidt, Germany.

by Charles B. MacDonald

Blank page

Chapter 1: Attack on Vossenack (2 November)

By October 1944, the First United States Army in Western Europe had ripped two big holes in the Siegfried Line, at Aachen and east of Roetgen.1 (Map V) Having captured Aachen, the army was next scheduled to cross the Roer River and reach the Rhine. It planned to make its main effort toward Düren in the zone of VII Corps south and east of Aachen and thence toward Bonn on the Rhine. But east of Roetgen, where the 9th Infantry Division had breached the Siegfried Line and parts of a forest mass known generally as the Hürtgen Forest,2 V Corps was first to launch a limited flank operation. The 28th Infantry Division, under the command of Maj. Gen. Norman D. Cota, was ordered to make the V Corps attack; its initial objective was to be the crossroads town of Schmidt.

Schmidt was an important objective. Lying on a ridge overlooking the upper Roer River, it also afforded a view of the Schwammenauel Dam, an important link in a series of Roer dams which the Germans might blow at any time. The rush of floodwaters thus unleashed would isolate any attack which had crossed the Roer in the Aachen vicinity. Located in rear of the main Siegfried Line defenses in the area, Schmidt was an important road center for supply of enemy forces. The capture of Schmidt would enable the 28th Division to advance to the southwest and attack from the rear the enemy’s fortified line facing Monschau, while a combat command of the 5th Armored Division hit the line frontally. Thus V Corps could complete the mission assigned by First Army—clearing the enemy from its area south to the Roer River on a line Monschau-Roer River dams. In enemy hands the Roer dams remained a constant threat to any major drive across the Roer downstream to the north.

The Schmidt operation was expected to accomplish four things: gain maneuver space and additional supply routes for the VII Corps attack to the north; protect VII Corps’ right flank from counterattack; prepare the ground for a later attack to seize the Roer River dams;3 and

attract enemy reserves from VII Corps, thus preventing their employment against First Army’s main effort.

Because the permanent boundary between V Corps and VII Corps intersected the planned zone of operations, First Army on 25 October designated a temporary boundary to run just south of Kleinhau and north of Hürtgen. This would keep the Schmidt operation entirely within the bounds of V Corps. Between the northernmost positions of the 28th Division and the new corps boundary, the defensive line was being held with a series of road blocks in the Hürtgen Forest by the 294th Engineer Combat Battalion; south of the planned zone of operations the line was being held by the 4th Cavalry Group.

Taking over the 9th Infantry Division’s sector on 26 October, the 28th Division found itself facing roller-coaster terrain that was to play an even more vital role than usual in the attack on Schmidt. (Map VI) Its front lines extended generally along the Hürtgen–Germeter–Rollesbroich road from Germeter through Richelskaul to the vicinity of a forester’s house, Raffelsbrand. To the north and south lay dense forests, the southern forests hiding numerous enemy pillboxes and the town of Simonskall. To the east from Germeter ran a ridge topped by the town of Vossenack, surrounded on three sides by deep, densely wooded draws with wooded fingers stretching up toward the town itself. To the northeast was the Hürtgen–Brandenberg–Bergstein ridge, dominating the Vossenack ridge. (In 9th Division operations in this area, one battalion had attacked between these two ridges and secured positions in the woods north of Vossenack, but a violent enemy counterattack in the woods southwest of Hürtgen had forced the advance battalion’s withdrawal.) Through a precipitous wooded gorge to the east and southeast of Vossenack ran the Kall River, a small, swift-flowing stream emptying into the Roer near Nideggen. Although a river road ran generally north-south alongside the Kall, only a small woods trail, very difficult to locate on the available maps and aerial photographs, crossed the river in the direction of the 28th Division’s attack. That trail led across the river and up another ridge on which were seated the towns of Kommerscheidt and Schmidt. This ridge also dominated the Vossenack ridge, and Schmidt in turn commanded Kommerscheidt. The Brandenberg–Bergstein ridge line, northeast of Vossenack and north of Kommerscheidt, was lower than the highest point of the Schmidt–Kommerscheidt ridge but overlooked its lower slopes where the towns of Schmidt and Kommerscheidt were situated. Schmidt

and Kommerscheidt were also surrounded by dense woods and deep draws.

Two important considerations influenced the planners of the Schmidt operation. First, air support could isolate the battlefield from large-scale intervention of enemy reserves, especially armored reserves. Thus the Schmidt action would remain an infantry action inasmuch as crossing tanks over the Kall River was a doubtful possibility. The air task, extremely formidable because it involved neutralization of a number of Roer River bridges—and bridges are a difficult target for air—was assigned to the IX Tactical Air Command of the Ninth Air Force. Second, artillery support could deny the enemy the advantages of the dominating Brandenberg–Bergstein ridge. While the planners displayed great concern about enemy observation from this ridge, V Corps had too few troops to assign the ridge as a ground objective. Neutralization of the ridge by artillery would require almost constant smoking of approximately five miles and still could not be expected to eliminate the most forward enemy observation. But neutralization by artillery was apparently the only available solution.

The 28th Division was strongly reinforced for the operation. Major attachments included the following units: the 707th Tank Battalion (Medium); the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (Self Propelled) (minus one company); the 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Towed); the 86th Chemical Battalion (4.2-inch mortars); and the 1171st Engineer Combat Group. The 1171st consisted of the 20th, 146th (minus one company), and 1340th Engineer Combat Battalions.4 Artillery in direct support was to include the 28th Division’s organic artillery (the 107th, 109th, and 229th Field Artillery Battalions of 105-mm. howitzers and the 108th Field Artillery Battalion of 155mm. howitzers); Battery A, 987th Field Artillery Battalion of 155-mm. self-propelled guns; 76th Field Artillery Battalion of 105-mm. howitzers; 447th Antiaircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion; and the attached tank destroyers and tanks. Two 155-mm. howitzer battalions of the 187th Field Artillery Group of V Corps were later assigned in direct support and a battalion of 4.5-inch guns in general support. Also to furnish general support were the 190th Field Artillery Group of V Corps, consisting of one 155-mm. gun battalion and one 8-inch howitzer battalion, and the 188th Field Artillery Group of VII Corps, consisting of one 155-mm. gun battalion and one battalion (less one battery) of 4.5-inch guns.

The 28th Division’s employment of its regiments was virtually dictated by V Corps.5 The 109th Infantry was to attack north toward Hürtgen in order to prevent repetition of the enemy counterattack that had hit the 9th Division from that direction. It was also to carry out a secondary mission of securing a line of departure overlooking Hürtgen from which another division might later capture

the town. This later attack on Hürtgen was to be a part of the main First Army attack by VII Corps, and the securing of a line of departure for the later attack was specifically assigned by First Army. The 110th Infantry was to attack through the dense woods to the southeast to secure a road from Schmidt to Strauch that would ease the problem of the tenuous supply route from Vossenack to Schmidt. The road could be used also in the later phase of the operation, the planned coordinated attack to roll up enemy defenses facing Monschau. One battalion of the 110th Infantry was to be held out initially as the division’s only infantry reserve. The 112th Infantry was to make the division’s main effort toward the east and southeast to Schmidt. Two major factors influenced this deviation from the tactical doctrine of a convergent attack: (1) the lack of troops available for the operation and (2) the necessity for performing the three initial missions: (a) protecting the north flank against counterattack and securing a line of departure overlooking Hürtgen, (b) clearing the main route south toward Strauch in preparation for the latter phase of the attack, and (c) capturing the initial division objective, the town of Schmidt.

Attached to the 112th Infantry in the main effort to capture Schmidt were: Company C, 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion (organic); Companies B and D, 86th Chemical Battalion (4.2-inch mortars); and Company C, 103rd Medical Battalion (organic). In direct support were: the 229th Field Artillery Battalion, reinforced by Company C, 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion (Towed); the 20th Engineer Combat Battalion; and Company C, 707th Tank Battalion (Medium). The 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion (Self-Propelled) and the remainder of the 707th Tank Battalion (minus Company D, which was to assist the 28th Reconnaissance Troop in maintaining contact with the 4th Cavalry Group in defensive positions to the south) were to reinforce fires of the general support artillery.

The artillery plan called for conventional fires on known and suspected enemy locations, installations, and sensitive points, the bulk of them in the Hürtgen area to the north. The preparation was to begin at H minus 60 minutes all along the V Corps front and the southern portion of the VII Corps front to conceal as long as possible the specific location of the attack. At H minus 15 minutes, fires were to shift to local preparation, and after H Hour fires were to be supporting, chiefly prepared fires on call from the infantry. Since weather limited air observation before the attack, counterbattery fires were based primarily on sound and flash recordings, which could not be considered accurate because of unfavorable weather and wooded, compartmented terrain. Ammunition was limited but considered adequate, and antitank defense was also included in the artillery plan. Artillery units were located in the general area Zweifall–Roett–Roetgen, from which all expected targets would be within effective range.

The engineer plan revolved around the attached 1171st Engineer Combat Group. One battalion of this group was to support the 110th Infantry and one was to work on rear area roads. The 20th Engineer Combat Battalion, in support of the 112th Infantry, was assigned the primary engineer mission of opening the trail from Vossenack across the Kall River to Kommerscheidt and Schmidt. In the

planning phases, engineer responsibility for security of the Kall River crossing was emphasized, but the engineer plan as issued by the 1171st Group on 30 October did not charge any engineer unit with security of the crossing. The plan stated only that, because of the disposition of friendly troops, local security would be required. The written engineer plan, including this statement, was nevertheless approved by the 28th Division commander, the division engineer, and the corps engineer.6

The 28th Division, whose men wore the red Keystone shoulder patch that revealed the division’s Pennsylvania National Guard background, had participated in the latter stages of the Normandy battle and had pursued the enemy across France and Belgium. Rested after almost a month along a relatively inactive sector of the Siegfried Line to the south, the division was nearly at full strength, although there had been many replacements after an unsuccessful effort to penetrate the Siegfried Line opposite Pruem at the close of the pursuit across Belgium. The major supply shortage was in all types of artillery ammunition, chronic throughout First Army since September when the Siegfried Line battles had begun. The supply of arctic overshoes was also far under requirements; only about ten to fifteen men per infantry company were equipped with them. There was little patrolling before D Day, partially because of the proximity of enemy lines and partially because of the limitations of the densely wooded terrain; but intelligence information obtained in the area by the 9th Division was turned over to the 28th. Maps to be used were primarily the standard 1:25,000 (Germany, revised), which could be considered generally accurate, but aerial photographs were usually not available in lower echelons.

When the 28th Division moved into the area on 26 October, the men found themselves in a dank, dense forest of the type immortalized in old German folk tales. All about them they saw emergency rations containers, artillery-destroyed trees, loose mines along poor, muddy roads and trails, and shell and mine craters by the hundreds. The troops relieved by the 28th Division were tired, unshaven, dirty, and nervous. They bore the telltale signs of a tough fight—signs that made a strong impression on the incoming soldiers and their commanders. After the operation the 28th Division commander himself, General Cota, recalled that at the time he felt that the 28th’s attack had only “a gambler’s chance” of succeeding.7

The 28th Division G-2 estimated that to the immediate front the enemy had approximately 3,350 men, to the north 1,940, and to the south 1,850, all of whom were fighting as infantry. Enemy reserves capable of rapid intervention were estimated at 2,000 not yet committed and 3,000 capable of moving quickly from less active fronts. The G-2 estimate did not mention that holding Schmidt and the Roer River dams was an important fundamental in the German scheme for preventing an Allied break-through to the Rhine.

The Schwammenauel Dam located southeast of Schmidt. The holders of this dam controlled the flow of water along the Roer River and could flood a wide area along its path.

Although the 28th’s attack was originally scheduled to be launched on 31 October, rain, fog, and poor visibility necessitated postponement. Despite continued bad weather, the attack was ordered for 2 November to avoid the possibility of delaying the subsequent VII Corps attack. The 109th Infantry was to initiate the action by launching its northerly thrust at 0900.8 While the 110th Infantry and two battalions of the 112th were not to attack until H plus 3 hours (1200), the 2nd Battalion, 112th, was to join the 109th in the H Hour jump-off—0900, 2 November.9

Facing the planned American attack was an enemy determined to hold the Hürtgen–Vossenack area for several

reasons now apparent: the threat to the Roer dams; the dominating terrain of the ridges in the area; the importance of Düren as a road and communications center; the threat to plans already made for an Ardennes counteroffensive; and the neutralizing effect of the Hürtgen Forest against American superiority in air, tanks, and artillery. The unit charged with the defense was the 275th Infantry Division of the LXXIV Corps of the Seventh Army of Army Group B.

That an attack was imminent was already known from obviously preplanned American artillery fires and from reports and observation of American troop movement in the rear of Roetgen. It was also known that the new American unit in the area was the 28th Infantry Division, although the Germans thought the division a part of VII Corps instead of V Corps.

North of the 275th Infantry Division the line was held by the 12th Volks Grenadier Division, and to the south by the 89th Infantry Division, which was scheduled to be relieved soon by the 272nd Volks Grenadier Division so that the 89th could be re-equipped. To the north, in Army Group B reserve in the München-Gladbach area, was the 116th Panzer Division. Although the Germans believed an American attack imminent in the Vossenack area, no specific precautions had been taken in movement of troops, because timing and direction of attack were still unknown.10

The 112th Makes the Main Effort

In the center of the 28th Division zone the 112th Infantry, making the division’s main effort, was assigned the capture of Kommerscheidt and Schmidt. It had the secondary mission of protecting its own north flank by the capture and defense of Vossenack and the Vossenack ridge. After the planned artillery preparation beginning at H minus 60 minutes, the 2nd Battalion, 112th, was to attack at H Hour (0900) to capture Vossenack and the forward (northeastern and eastern) nose of the ridge. The 1st Battalion, 112th, attacking at H plus 3 hours, was to move in a column of companies through defensive positions occupied by the same regiment’s Company A at Richelskaul. Then it was to attack southeast through the wooded draw south of Vossenack, crossing the Kall River in a cross-country move and taking Kommerscheidt. The 3rd Battalion, 112th, was to follow the 1st Battalion on order and capture the final objective, the town of Schmidt.11

The 2nd Battalion’s plan for seizing Vossenack and the Vossenack ridge called for an attack with two companies abreast (Company G on the left, Company F on the right) from the line Germeter–Richelskaul east through Vossenack. Company G was to move along the open northern slope of the ridge to the nose

northeast of Vossenack; Company F was to take the town itself and the eastern nose of the ridge; and Company E was to follow and complete mopping up of the town. One platoon from Company F was to protect the battalion’s right flank by advancing along the open southern slope of the ridge and was to be followed by one platoon of Company E.12

This 2nd Battalion attack was to be assisted by a company of medium tanks, Company C, 707th Tank Battalion. The five tanks of Company C’s 1st Platoon, plus two tanks from its 2nd Platoon, were to attack with Company G, 112th, on the left; the three other tanks of the 2nd Platoon were to attack with Company F, 112th, on the right. The remaining tank platoon was to assist Company E in its mop-up operations. Two towed guns of Company B, 630th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and five 57-mm. antitank guns of the Antitank Company, 112th, all in position around Richelskaul, were to be prepared to assist the attack by fire. Company B, 86th Chemical Battalion, equipped to fire high explosive shells, was to support the attack from positions along the Weisser Weh Creek in the wooded draw west of Germeter. The night before the attack Company C, 103rd Engineers, was to clear paths through friendly mine fields to the east of Germeter.13

The regiment’s eighteen 81-mm. mortars were grouped under Company H for preparation and supporting fires against Vossenack. After capture of the town, they were to revert to their respective battalions. The Company D mortars were to concentrate their fire on the draw south of Vossenack, Company H on the houses in the town, and Company M on the wooded area north of the town, firing to begin twelve minutes before H Hour. The Company H machine guns were attached to the three rifle companies, the entire 2nd Platoon going to Company G on the left, the 1st Section of the 1st Platoon to Company F on the right, and the 2nd Section of the 1st Platoon to Company E for the mop-up.14

Before the attack Company E, 112th Infantry, was outposting the town of Germeter, while the remainder of the 2nd Battalion was in an assembly area in the woods approximately 300 yards southwest of Germeter. (Map VII) On the left (north) the 3rd Battalion, 109th Infantry, held Wittscheidt on the Hürtgen road and was to attack almost due north at H Hour. On the right (south) Company A, 112th, held the Richelskaul road junction and was to be passed through at noon (H plus 3 hours) by other elements of the 1st Battalion, 112th, and the 3rd Battalion, 112th, in the attack southeast toward Kommerscheidt and Schmidt. The 112th’s Cannon Company was to

provide supporting fires from positions in the woods some 2,000 yards west of Germeter. The 112th Infantry command post was in a captured pillbox along the Weisser Weh Creek west of Germeter.15

The 2nd Battalion Attacks

The morning of 2 November dawned cold and misty, not quite freezing, but damp and uncomfortable. At 0800, an hour before H Hour, artillery along the entire V Corps front and the southern portion of the VII Corps front roared into action. Fifteen minutes before jump-off time direct support artillery shifted to targets in the immediate sector and was joined by heavy weapons of the 112th Infantry. By 0900 V Corps and VII Corps artillery had fired over 4,000 rounds, and 28th Division artillery had fired 7,313 rounds. Artillery liaison officers watched the preparation from the 112th Infantry observation post in an attic in Germeter, where the 112th regimental commander, Lt. Col. Carl L. Peterson, prepared to watch the attack.16

At 0900 the riflemen of Companies G and F, accompanied by the tanks of Company C, 707th, began to pass through the outpost positions in Germeter. Almost as soon as the preparatory American artillery fire shifted to more distant targets, the Germans replied with a heavy artillery concentration of their own upon the line of departure, and the attacking companies sustained a number of casualties. Nevertheless the attack continued, and the men and tanks moved out into the shell-pocked open fields leading east to the objective, plainly marked in the morning mist by the shell-scarred tower of the Vossenack church. With the tanks taking the lead, the infantrymen fell in close behind, stepping in the tank tracks as a precaution against antipersonnel mines. Scattered small arms fire from Vossenack sprayed the tanks, and the Germans fired light mortar concentrations; but neither stopped the advance.17

Company G on the Left

On the left in its attack along the open slopes north of Vossenack toward the northeastern nose of the ridge, Company G started out with its 3rd Platoon on the left, its 1st Platoon on the right, and its 2nd, which was considerably understrength, in support. Its seven attached tanks initiated the movement by swinging into a line formation and firing four rounds each at the Vossenack church steeple, presumably to discourage any enemy observation from the steeple.

Two gaps had been cleared in the friendly mine field in the Company G sector. Although the southernmost gap near the center of Germeter was poorly marked and difficult to locate initially, it was used because it was more directly

Vossenack. The damaged tower of the Vossenack church could be seen by men approaching from the northwest across the shell pocked open fields.

along the proposed route of advance. The assault platoons moved through the gap close in the wake of the seven tanks, about a squad of infantry following each tank. The advance had only just begun when the driver of the lead tank on the left, that of the tank platoon sergeant, T. Sgt. Audney S. Brown, misread the mine-field markings and blundered out of the cleared gap. The tank hit a mine and blew a track. When the assault platoons and their six remaining tanks again moved forward, the platoon leader’s tank mired in a muddy patch of ground in the north-south draw which creased the ridge between Germeter and Vossenack, again halting the advance. The tank company commander, Capt. George S. West, Jr., seeing the difficulty, came forward in his command tank, picked up the platoon leader, 2nd Lt. William D. Quarrie, and took position on the right of the formation. Again the attack moved forward.18

With infantrymen following close in their tracks, the tanks fired as they advanced. A provisional platoon of .50-caliber machine guns supported the advance from Germeter, its fire clipping the edge of the woods north of Vossenack; fire from supporting 81-mm. mortars was well coordinated and fell about a hundred yards in front of the attack formation.

Even as the tanks were having their difficulties, the company headquarters of Company G and the attached machine guns from Company H ran into trouble. Either the light enemy mortar fire or harassing small arms fire from Vossenack wounded the machine gun platoon leader shortly after the machine gunners left Germeter, and the platoon sergeant took over. A few minutes later the last man in Company G’s headquarters group stepped on a booby trap or a mine. When a man from the machine gun platoon moved up to see if he could help, he stepped on still another booby trap or mine and was killed. The explosion set off about five antipersonnel mines simultaneously. Of the twenty-seven men who had been in this group, twelve were injured or killed in the mine field. Only two noncommissioned officers, both corporals, remained out of the machine gun platoon’s leaders. Although slightly wounded, they reorganized the platoon and continued forward.19

The assault rifle platoons also suffered casualties, both the 1st and 3rd Platoon leaders being hit within approximately 400 yards of the line of departure. That the leaders should be wounded seemed ironic, for as the advance continued the only enemy opposition came from light mortar fire. The supporting tanks fired as they moved, and many of the Germans in Vossenack, already weakened by long days and nights of American artillery fire and now faced with a coordinated tank-infantry assault, fled north, east, and southeast. Past outlying farms and through the open fields north of Vossenack the Company G assault pushed on quickly and soon reached its objective, the nose to the northeast of the town. In an attack for which the planners had allowed three hours, Company G and its supporting tanks and machine gun platoon had taken only one hour and five

minutes, gaining the objective shortly after 1000 hours.20

Having reached the nose of the ridge, the company began to reorganize and to dig in against counterattack. Its assigned zone included a trail—actually an extension of Vossenack’s main street—northeast of the town. The trail was in the defensive sector of the 3rd Platoon, which planned to tie in later with Company F on the right. The 1st Platoon took up positions on the left of the 3rd; the 2nd Platoon, which had been in support in the attack, came up almost an hour later and extended the semicircular perimeter to the left and left rear. The two light machine guns went into position with the 1st Platoon to cover the company’s front with cross fire. When the platoon of heavy machine guns came forward, it was placed in position with the 3rd Platoon on the right to fire across the company front in the other direction, thus forming a final protective line. The 60-mm. mortars were moved up during the afternoon and placed in slight defilade about 200 yards behind the company. All defenses except the 60-mm. mortars were on the exposed forward nose of the ridge, in accordance with the battalion order; despite this exposed terrain, the men were virtually ignored by the enemy for the rest of the day. The six supporting tanks churned around on the forward slope of the ridge and fired to the northeast toward Brandenberg–Bergstein, as if the attack were going to continue in that direction. Company G’s advance had been surprisingly easy; its principal casualties had been incurred in a mine field; only minor casualties had resulted from the artillery shelling at the line of departure, light mortar fire, and the occasional harassing small arms fire.

Company F on the Right

While Company G was launching its successful attack on the left, Company F had also moved out at H Hour in a column of platoons preceded by its three supporting tanks. The lead platoon, the 3rd, under 1st Lt. Eugene S. Carlson, was to advance along the open southern slope of the Vossenack ridge as the battalion’s right flank protection. Since the area south of the Richelskaul–Vossenack road was deemed too exposed to suspected enemy positions in the southern woods in front of Richelskaul, the 3rd Platoon and its three tanks planned to advance north of the road initially, then turn south on the outskirts of Vossenack, cross the road, and resume their movement to the east. Company F’s 1st Platoon was to follow the lead platoon closely until it turned south. The 1st Platoon was to continue east through the town itself. The 2nd Platoon was to remain in Germeter as support to move forward on call. The section of light machine guns and two 60-mm. mortars were attached to the leading 3rd Platoon; the other mortar was attached to the 1st Platoon. Also with the company was a section of heavy machine guns from Company H. The three supporting tanks were under the command of 1st Lt. James J. Leming, the 2nd Tank Platoon leader and acting company executive officer.

The assault force moved out at H Hour, the infantry platoon following so closely behind its column of spearheading tanks that for the first 500 yards the infantry platoon leader, Lieutenant Carlson, had his hand on the rear of Lieutenant

Leming’s tank. There was no resistance except from light enemy mortar fire. When the tanks and the lead riflemen passed the Germeter–Vossenack–Richelskaul road fork, the column veered to the south across the main Vossenack road as planned. Beyond the road the third tank in the column continued too far to the south before turning east again and ran into surprise German opposition from the wooded draw to the south. A Panzerfaust at the edge of the woods knocked it out. The two remaining tanks and the accompanying infantry platoon continued to the east, the tanks firing toward the southern woods line at possible enemy positions. They had gone approximately 300 yards past the first wooded finger pointing toward Vossenack from the south when the 75-mm. gun on Lieutenant Leming’s tank jammed. The tank’s coaxial machine guns and bow guns incurred stoppages that “immediate action” would not clear, and the antiaircraft gun also failed when its bolt jammed from overheating. The advance stopped. Lieutenant Leming radioed for 2nd Lt. Joseph S. Novak, platoon leader of the 3rd Tank Platoon with Company E in reserve, to come forward in his tank and lead Leming’s one remaining tank forward.21

Back nearer the line of departure, Company F’s 1st Platoon had followed about 200 yards behind the lead platoon and its tanks. In an approach march formation with the 2nd and 1st Squads forward and the 3rd in close support, the 1st Platoon passed through the gap in the mine field and neared the Germeter–Richelskaul–Vossenack road fork. At this point, a sudden burst of fire came from two or three hitherto undetected German machine guns emplaced near a group of buildings at the road fork. The Germans had evidently held their fire when the preceding tanks and infantry had passed.

This first burst of enemy fire hit the 1st Squad heavily, wounding or killing all but three men. Although the 2nd Squad and the remnants of the 1st built up a base of fire, the Germans continued to resist. To break the deadlock, the infantry platoon leader, 2nd Lt. John B. Wine, crawled to within twenty-five yards of the position and knocked out at least one machine gun with a hand grenade. At the lieutenant’s signal the two advance squads assaulted the position, overcame the German gunners, and captured four or five prisoners.

Reorganizing his platoon quickly, Lieutenant Wine continued without opposition into the outskirts of Vossenack. One squad began to operate on each side of the main street. The men sprayed the entrances of the houses with fire, tossed in hand grenades, and assaulted each building in the wake of the grenade explosions. At least one Company F man was wounded and another killed as the enemy threw in scattered artillery fire.22

The Company F commander, 1st Lt. Eldeen Kauffman, had followed the 3rd Platoon to a point just past the gap in the mine field. He waited there for the 1st Platoon and then followed it through the action at the road fork and on into Vossenack. When he heard over his intracompany SCR 536 that the 2nd

Platoon, in support at the line of departure in Germeter, was receiving intense enemy artillery fire, he ordered the platoon to join him in Vossenack.

Lieutenant Wine’s 1st Platoon, continuing its advance, had almost reached the main crossroads marked by the church in the center of Vossenack. (Map VIII) At this point it was held up by small arms fire from the house on the left just short of the crossroads. Supported by fire from the rest of the platoon, half of one squad assaulted the house and netted between thirty and fifty prisoners. The town of Vossenack as far east as the crossroads was then in American hands.

Upon the arrival of the 2nd (support) Platoon, Lieutenant Kauffman, the company commander, ordered it to pass through Lieutenant Wine’s unit, which had become disorganized in its fight at the crossroads. Except for three men lost to artillery fire in Germeter, the 2nd Platoon was at full strength. The exchange in assault platoons was made about 1030 at the crossroads, approximately an hour and a half after the jump-off. Though the advance had been rapid, the leading elements of Company F had covered only a little more than half the distance to their objective, whereas elements of Company G had already reached the northeastern nose of the Vossenack ridge.23

The 3rd Platoon was still waiting on the exposed slope south of the town for Lieutenant Novak to come forward with his tank from Germeter to assist the one remaining operational tank of Lieutenant Leming’s platoon. When the assistance arrived, it developed that Lieutenant Novak had evidently misunderstood the request and, instead of coming forward himself, had sent S. Sgt. Paul F. Jenkins with the 3rd Tank Platoon’s 2nd Section, two tanks instead of one.

The advance continued and the three tanks came abreast of the town’s main crossroads. Seeing what they suspected to be an enemy mine field ahead, the tankers changed their route of advance and moved north with their accompanying infantry through the center of Vossenack. They followed the open northern slope over which the tanks with Company G had passed earlier. Without opposition the three tanks and Company F’s 3rd Platoon moved just to the right of Company G on the eastern nose of the ridge. There the infantrymen began to dig in on their objective.24

While the 3rd Platoon was taking its roundabout route forward, the 2nd Platoon under 1st Lt. George E. Scott continued its advance past the crossroads in Vossenack. From a house on the left, two or three houses east of the crossroads, a German “Burp gun” (machine pistol) opened fire and halted the Americans with its first burst. As Lieutenant Scott moved up to one of his squads to meet the situation, another burst killed him instantly. The platoon sergeant then tried to organize a flanking force, but he too was hit and seriously wounded. A squad leader was killed and his second in command seriously wounded in an attempt to shift their squad to where it could flank the position from the north.

Back at the Germeter line of departure, the remaining three tanks of Lieutenant Novak’s 3rd Tank Platoon had started forward shortly after Sergeant Jenkins left with the platoon’s 2nd Section.

Novak’s tanks, scheduled to assist Company E in the Vossenack mop-up, moved too quickly for the infantry to keep pace and reached the crossroads ahead of the reserve company. There Lieutenant Kauffman seized the opportunity and commandeered one of the tanks to help in demolishing the burp gun resistance. The tanker fired two rounds at the building indicated by Lieutenant Kauffman, and the F Company commander and his runner, Pfc. Bud Kern, charged the house close behind the tank fire. Inside they found seven men and two German officers, one of whom was already wounded. Kauffman and Kern killed the other officer, and the German enlisted men promptly surrendered.

Lieutenant Novak, meanwhile, had turned south with his tank, apparently intending either to use the southern slope and so avoid the town as he moved eastward or to help knock out the burp gun by firing on the house from another direction. As he neared the southern edge of the town, his tank struck a mine and was immobilized. Since it could still be used as a stationary firing point, Lieutenant Novak stayed with his vehicle, while his two remaining tanks went on with Lieutenant Kauffman and Company F.

With the German burp gun resistance now out of the way, the advance continued. Lieutenant Kauffman tossed a grenade into the basement of the next house as a routine precaution, with the result that a group of Germans, who proved to be staff members of the battalion charged with the defense of Vossenack, came out in surrender. When questioned, one of the German officers pointed out the town’s defensive positions on a map. There had been five thirty-man companies in Vossenack, he said, and despite high losses another company had the mission of counterattacking to retake the town.

Lieutenant Kauffman shifted Company F’s 1st Platoon, now reorganized, back into the attack echelon and returned the 2nd Platoon to its original support role. Accompanied by the two tanks of Lieutenant Novak’s tank platoon, Lieutenant Wine’s men continued down the main street, charging each building close behind assault fire from the tanks. The Germans fired only a few desultory shots in return, and by 1230 the 1st and 2nd Platoons had joined the 3rd Platoon on the final objective, the bald eastern nose of Vossenack ridge.25

Lieutenant Kauffman set up his Company F command post in the last house on the right (south) side of Vossenack’s main street. The 2nd Platoon began to dig in on the left next to Company G’s right flank. On the 2nd’s right was the 1st Platoon, its depleted 1st and 2nd Squads combined into one and designated to defend a wooded draw that stretched up toward the town from the Kall River valley. The 3rd Platoon dug in on the 1st’s right on a little exposed nose projecting east between two draws. The section of light machine guns dug in with the 2nd Platoon on the left, the 1st (machine gun) Platoon from Company H with the right platoon, and the provisional .50-caliber machine gun platoon alone on the ridge farther to the southwest. One section of Company H 81-mm. mortars had moved up to firing positions to the north of Vossenack as soon as Company G had reached its

objective; after Company F completed its advance, the other sections displaced to the vicinity of the church. Through this day and the next, forward observers from the mortar platoon were with all three rifle companies. Later, because of enemy shelling, observers were pulled back to a central observation post in a house near the eastern end of the town.26

Company E Mops Up

The mission of Company E was to follow Company F at an interval of approximately 300 yards to Vossenack. There it would complete the mopping up of German resistance in the town. One platoon was to move along the edge of the woods on the south behind the right platoon of Company F in order to assist in protecting the battalion’s right flank. The 3rd Tank Platoon under Lieutenant Novak was to precede Company E into Vossenack and assist in mopping up. One section of machine guns from Company H was also attached.

When the acting company commander of Company E, 1st Lt. James A. Condon, saw Company F moving out at 0830 in preparation for its attack, he began to assemble his men. Lieutenant Condon assumed that Company E was to wait until all of Company F had gone forward, and as time passed Company F’s support platoon still did not advance. Company E’s premature assembly had brought the men out of their holes and buildings ready to move forward, and thus they fell easy prey to the German artillery and mortar fire which centered on the line of departure. The company suffered a number of casualties.27

Company E’s 1st platoon, assigned the right flank security mission, preceded the forward movement of the company’s main body, following behind the right flank platoon of Company F about 0920. (See Map VII) The platoon leader, S. Sgt. Edward J. Beck, employed two squads forward and one back with the assault squads in skirmish line and the support squad in squad column echeloned to the right rear.

Evidently not aware of the previous decision to use the more defiladed route north of the Richelskaul–Vossenack road instead of the southern route, Sergeant Beck’s men had gone only about 300 yards past the line of departure when two enemy machine guns located in the edge of the woods to the south opened fire. The Company E platoon was pinned to the ground. Although Beck directed his men to work forward by individual rushes, the enemy stopped even that forward movement by plastering mortar fire on the exposed position. One man was killed and several were wounded, including Sergeant Beck.

Several men, one of whom was hysterical and obviously suffering from shock, made their way back individually to the acting company commander in Germeter with varying accounts of what had happened. Finally, as Lieutenant London was starting the remainder of his company toward Vossenack, an assistant squad leader, Sgt. Henry Bart, returned from the hard-pressed platoon and said he was now senior noncommissioned officer in the platoon and in command.

When Sergeant Bart said there were only a few of his men left, Lieutenant Condon told him to “pick up the remnants,” evacuate the wounded, and follow the tail of the company through Vossenack. Bart returned to his men, but the enemy fire blocked evacuation. Not until about noon, when the 1st Battalion attacked southeast from Richelskaul and thus relieved the pressure against Company E’s 1st Platoon, did two men, Sergeant Bart and Pfc. Clyde Wallace, manage to work around behind the German machine guns and take them from the rear. Private Wallace went back to the battalion command post in Germeter with two prisoners, and the remainder of the platoon, reduced now to about thirteen men, continued into Vossenack.28

While the 1st Platoon was still pinned down in the open field, the remainder of Company E and its attached machine gun section continued on the mission to mop up in Vossenack. (See Map VIII.) In a column of twos on either side of the main road, the men advanced cautiously, checking all buildings and cellars and taking occasional prisoners. Only one man was wounded, a 2nd Platoon rifleman, hit in the arm by a shell fragment.29

Lieutenant Novak’s three tanks, which were supposed to accompany Company E in the mop-up, soon outdistanced the riflemen and instead assisted Company F in clearing the eastern portion of Vossenack. About 1040, shortly after Company E must have first entered the outskirts of the town, Captain West, the tank company commander, who had moved with Company G to the northeastern nose of the ridge, received a radio message asking for tank support for Company E. On his way back via the southern route to help out, his command tank hit a mine just south of the church, probably in the mine field which Lieutenant Leming’s tanks had previously suspected and avoided. Captain West dismounted and found that his battalion headquarters tank had come up. It was near by performing forward observation for the tank battalion’s assault gun platoon. West took over the headquarters tank to assist Company E in completing its mop-up. Back on the northeastern nose of the ridge, the tanks that had reached the objective maneuvered around in rear of the infantry positions. There Lieutenant Quarrie’s tank threw a track, and the crew could not replace it.30

About 1530 Company E finished its attack mission in Vossenack and began to prepare for the defense. Lieutenant Condon placed his 3rd Platoon on the left (north) of town, generally along the line of houses on the northern side of the street, and his 2nd Platoon similarly on the right (south) side of town. The remaining men of the 1st Platoon faced to the west in a defense within the town itself, denying the battalion rear. Light enemy artillery fire fell as the company was going into position, and two men were killed, one of them Private Wallace, who had assisted Sergeant Bart in overcoming the German resistance southeast of Germeter and had returned after taking two prisoners to the battalion CP.31

During the afternoon a tank retriever that was sent into Vossenack to tow out

Lieutenant Novak’s damaged tank near the church was itself damaged by a direct hit from enemy artillery. With his own tank Lieutenant Leming tried to tow out Lieutenant Quarrie’s tank, but his efforts were unsuccessful. The tank company received permission about 1600 to draw back to bivouac positions in the western edge of Vossenack and there went into a circle defense for the night and effected gasoline and ammunition resupply.32

The forward battalion command group had followed the attack closely and by 1630 had established a command post in a house approximately 300 yards east of the church in Vossenack on the south side of the main street. The rear battalion command post moved up after dark, every available man being pressed into service to carry an extra load of ammunition for resupplying the companies.33

Artillery in the Vossenack Attack

The 229th Field Artillery Battalion in direct support of the 112th Infantry fired a total of 1,346 rounds from 0800 to 1200 on 2 November, thus providing continuous artillery support on call during the entire Vossenack attack. In addition to the preparation fires, missions were harassing, counterbattery, and targets of opportunity. Company B, 86th Chemical Battalion, fired 274 high explosive and 225 white phosphorous rounds with its 4.2 mortars, and at various times during the day Vossenack was reported burning and covered with a haze of smoke. Company D, 86th Chemical Battalion, did not fire, having pulled out of firing position to be prepared to follow the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 112th Infantry, to Schmidt.34

The 1st Battalion Attacks at H Plus 3 Hours

When the 28th Division moved into the Vossenack–Schmidt area, the 1st Battalion, 112th Infantry, had initially been in regimental reserve, but on 1 November Company A had relieved elements of the 110th Infantry in defense of the junction of the Richelskaul–Rollesbroich road with the Simonskall road to the south. The rest of the battalion had remained in an assembly area a few hundred yards west of Richelskaul. (See Map VII.)

The 112th Infantry’s attack plan for 2 November designated the 1st and 3rd Battalions to attack cross country at H plus 3 hours (1200) in a column of battalions, the 1st leading. They were to move generally through the wooded part of the southern slope of Vossenack ridge, cross the Kall River, and seize Kommerscheidt. The 3rd Battalion was then to take Schmidt, and both were to to be prepared to continue the attack toward the southwest and Steckenborn. This was the division’s main effort.35

The 1st Battalion, under the command of Maj. Robert T. Hazlett, was to lead the attack in a column of companies, Company B leading and passing through

Company A’s Richelskaul defenses. Company C was to follow Company B on order, and, after Company C had passed through, Company A was then to leave its defenses to follow. Attached to Company B for spearheading the attack was the 1st (machine gun) Platoon of Company D. The 2nd (machine gun) Platoon was to support the attack by firing up the wooded draw to the east from positions with Company A at Richelskaul. The 81-mm. mortars were to support on call from a position in a draw in the woods 900 yards behind the line of departure.36

No preparatory artillery barrage preceded the men of Company B as they passed through the Richelskaul defenses shortly after noon in a column of platoons—1st, 3rd, 2nd, Weapons. The first phase line had been designated as a generally north-south trail, some 400 yards east of Richelskaul, which ambled, south from Vossenack’s western outskirts to a juncture in the southern woods with the road to Simonskall. As the 1st Platoon advanced toward that trail, it was fired upon from woods in the vicinity of the trail and pinned to the ground by intense enemy fire from small arms and entrenched automatic weapons. The 1st Platoon leader, 1st Lt. Ralph Spalin, acting as point for his platoon, was instantly killed.

Capt. Clifford T. Hackard, the Company B commander, committed his 3rd Platoon to assist the 1st, but in the attempted advance the 3rd Platoon leader, 2nd Lt. Gerald M. Burril, was hit by the enemy fire. Despite a broken leg, Lieutenant Burril dragged himself into a hole from which he directed mortar fire with his SCR 536. He was not evacuated until after dark when one of the men of his platoon and an aid man brought him out on a litter. Either the loss of its platoon leader or the enemy small arms fire, or both, kept the 3rd Platoon from advancing farther.

About one and one-half hours after the jump-off, Captain Hackard committed his 2nd Platoon to the action. One squad from the 2nd Platoon managed to work its way far enough forward to cross the trail; there it too was stopped by the intense small arms fire. Despite heavy supporting fire from Company D’s 81-mm. mortars, the attack was stalemated. At 1510 one concentration of twenty-four rounds was fired by the 229th Field Artillery Battalion at enemy machine guns along the trail just south of Company B’s attack route. This was seen by a forward observer and reported as “excellent,” but no further mission was recorded as having been fired in this area during the day. Company B still could not advance.37

The 1st Battalion commander, Major Hazlett, went to the regimental command post about 1500 and talked with Colonel Peterson, the regimental commander. On his return, Major Hazlett announced that most of the gain of the day would be held. Because of plans he had received

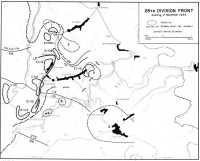

Map 20 28th Division Front Evening, 2 November 1944

for the next day, however, he did not want to leave Company B “stuck so far out front.”38 When Captain Hackard made his way back about dusk, Major Hazlett told him to pull back his advance elements (evidently the 2nd Platoon) to the remainder of the company, which now was in a small patch of woods about 200 to 250 yards in front of the line of departure, and to dig in there for the night. This move was accomplished after nightfall.39

Thus, the 28th Division’s main effort had been halted after its one attacking company had hit stiff German resistance. Except for one mission, artillery support had not been utilized, and neither the other two rifle companies of the 1st Battalion nor any part of the 3rd Battalion had been committed. The battalion and regimental commanders apparently decided that, in view of the stiff opposition encountered by Company B and the comparative ease with which the 2nd Battalion had taken Vossenack, the attack should be shifted to pass through Vossenack and avoid the resistance facing Richelskaul. At any rate, those were the plans for the next day.40

109th and 110th Infantry Regiments Attack

To the north of the 112th Infantry’s divisional main effort, the 109th Infantry had jumped off at H Hour in its attack to protect the division’s left flank and secure a line of departure overlooking Hürtgen. (Map 20) By 1400 the 1st

Battalion, on the left, had two companies on its objective, the woods line west of the Germeter–Hürtgen road. The 3rd Battalion had attacked generally up the Hürtgen road and committed all three rifle companies. They gained only about 300 to 500 yards before being stopped by a wide enemy mine field. After two companies of the regiment’s 2nd Battalion had moved up to a close reserve position a few hundred yards behind the 1st Battalion, ostensibly to cover a gap between the 1st and 3rd Battalions, the regiment buttoned up for the night.41

The 110th Infantry in the woods to the south had attacked at 1200, its 3rd Battalion moving generally southeast in the cross-country direction of Simonskall and its 2nd Battalion aiming for eight or ten pillboxes astride the main road south toward Rollesbroich. These pillbox defenses later became known as the Raffelsbrand strong point. Both battalions were stopped after almost no gain by determined resistance and heavily fortified pillboxes. The 1st Battalion, 110th Infantry, was the division’s infantry reserve and was not committed. The 110th’s attack to reach the Strauch–Schmidt road and thus open the way for the latter phase of the Schmidt operation (the capture of the Strauch–Steckenborn area) had made virtually no progress.42

Air Support

A vital mission in the Schmidt operation, that of isolating the Vossenack–Schmidt battlefield from large-scale intervention of enemy armor, had been assigned to the aircraft of the IX Tactical Air Command. Although the IX TAC was to continue its usual large-scale offensive against enemy transportation and communications, its main single effort was to be support of the 28th Division. The air plan involved use of five fighter bomber groups—the 365th, 366th, and 368th (P-47’s), and 370th and 474th (P-38’s)—and the 422nd Night Fighter Group (P-61’s).

On the first day of the 28th Division attack, a third of the IX TAC aircraft were to perform armed reconnaissance on all roads leading out of Schmidt to a limit of 25 miles, and another third were to attack special targets and drop leaflet bombs in support of the division. But weather conditions prevented the first planes from taking off from their base at Verviers, Belgium, until 1234. Two of five group missions were canceled and two others were vectored far afield in search of targets of opportunity. One mission did succeed: twelve P-38’s of the 474th Fighter Bomber Group attacked Bergstein at 1445 and continued on to hit barges on the Roer River, a Roer bridge at Heimbach, and two factories east of Nideggen. The 28th Division air control officer reported that one squadron mistakenly bombed an American artillery

Objective: pillboxes. Troops of the 110th Infantry, on 2 November, moving through the woods.

Objective: pillboxes. One of the heavily fortified pillboxes near Rollesbroich.

position near Roetgen and caused twenty-four American casualties (including seven killed) before attacking Schmidt.43

The Enemy Situation

On 2 November staff officers of Army Group B, the Fifth Panzer and Seventh Armies, and several corps and divisions, including the 116th Panzer Division, were meeting with Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model, Army Group B commander, at Schlenderhan Castle, near Quadrath, west of Cologne, for a map study. The subject of the study was a theoretical American attack along the boundary of the two armies in the Hürtgen area. Not long after the meeting began, a telephone call from the chief of staff of the LXXIV Corps told of actual American attacks north of Germeter and in the direction of Vossenack. The message said the situation was critical and asked for reserve troops from Seventh Army because LXXIV Corps did not have the men available to close the gaps already opened up by the American attacks. Field Marshal Model directed the LXXIV Corps commander to return to his command and ordered the other officers to continue the map study with the actual situation as subject.

As the map study continued, reports of the 28th Division’s attack continued to come in, and it was decided to commit immediately a Kampfgruppe of the 116th Panzer Division to assist local reserves in a counterattack against the 109th Infantry’s penetration north of Germeter. The remainder of the 116th Panzer Division was to follow later from its rest area near Muenchen-Gladbach. The chance presence of the various major commanders at the map conference facilitated preparations for this counterattack. It was designed to hit at dawn on 3 November to eliminate the 109th Infantry’s northern penetration and to push farther south so as to cut off the Vossenack penetration of the 112th Infantry. This was virtually the same type of counterattack which had threatened the 9th Infantry Division when it had held this area.44

Summary for 2 November and Night of 2-3 November

Beginning with a heavy artillery barrage at 0800 on 2 November, the 28th Division attack on Schmidt had met varying degrees of success. The 2nd Battalion, 112th Infantry, had made one of the more notable advances of the day in seizing Vossenack and the Vossenack ridge. Although the 1st Battalion, 112th Infantry, had attempted an attack southeast from Richelskaul toward Kommerscheidt and Schmidt, its one committed company had been held up by small arms fire and the attack not pursued, although the remainder of that battalion, plus the entire 3rd Battalion and a company of medium tanks, had been available. During the night plans were issued for a new attack the next morning to take the same objectives via a different route.

To the north one battalion of the 109th

Infantry had reached the woods line overlooking Hürtgen, while another had been held up by a previously unlocated mine field. To the south the 110th Infantry in a two-battalion attack had gained nothing except comparatively heavy casualties and the knowledge that its opposition was much stiffer than had been expected.

Although artillery support had been excellent, except in the attack of the 1st Battalion, 112th Infantry, where it was not requested, air support had been negligible. Attached engineers had concerned themselves primarily with maintenance of roads in rear areas, although Company C, 103rd Engineers, had cleared mines east of Germeter and had gone into Vossenack after dark for road clearance.

After dark all three regiments buttoned up for the night, evidently confining themselves to resupply, for there was no record of any patrolling. Meanwhile, the Germans, their defense facilitated by a chance map conference at Army Group B headquarters, were planning a dawn counterattack to eliminate both the 109th and 112th Infantry penetrations.

The 28th Division’s main effort for Kommerscheidt and Schmidt had on 2 November been pushed with a surprising lack of vigor, presumably because a decision was made somewhere in command channels that the original attack plan would not be followed. Although this decision was probably based on success in Vossenack as compared with stiff opposition on the original route of advance, it had nevertheless set back considerably the hour by which Schmidt might be taken. But on 3 November the 112th Infantry would make another attempt to capture the objective.