Chapter 8: Conclusion (9–20 November)

Before the dawn of 9 November weather conditions, already bad, became worse. The cold rain that fell on the litter patients outside the combined 1st–3rd Battalion aid station in the Kall gorge changed to snow, which continued after daylight. No relief vehicles had managed to get through, and the medical officers therefore decided to attempt their own evacuation.

About 200 yards up the trail they found two two-and-one-half-ton trucks which had been abandoned the night of 6-7 November by Lieutenant George, 3rd Battalion motor officer, when he could not get them past a road block of felled trees. The trail was too precarious to permit backing these trucks down to the log dugout for loading, but patients could be hand-carried to them. Then the vehicles would have to take their chances in running the gantlet of open ridge southeast of Vossenack. Not far from the trucks the medics found also a weasel that, despite several holes in its gasoline tank, could be used if someone continually poured gasoline into the tank. They located five cans of gasoline and loaded the weasel as well as the trucks with patients, finding space for all but about ten of the litter cases.1

Back at the regimental rear command post Major Berndt, the 112th Infantry surgeon, was unaware that the wounded had been withdrawn from the Kommerscheidt woods line the night before. Telephoning G-4, he volunteered to go under a white flag into the German lines to arrange a truce in order to evacuate any wounded still at the woods line. The offer was turned down. Berndt was told instead to determine the attitude of the enemy toward such a truce and to leave details and official confirmation for later.2

With T/4 Wheeler W. Wolters acting as flagbearer and interpreter, Major Berndt left Vossenack about 0950 and arrived at the aid station without having been fired upon. (Map 32) He found the medical personnel loading the wounded onto the two trucks and the weasel. Major Berndt did not know it but division had meanwhile changed its mind and authorized a truce.3

Leaving the aid station, the medical major and T/4 Wolters continued to the river, where they found that the bridge had been destroyed. As they stood on the broken abutment debating the possibility and advisability of fording the river, a German rifleman stood up in a foxhole a short

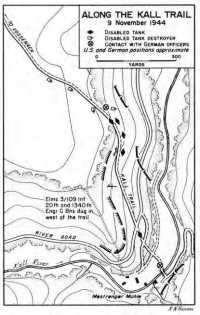

Map 32 Along the Kall Trail 9 November 1944

distance beyond the bridge site on the east bank and called to them. Wolters shouted back the purpose of their visit, whereupon the enemy soldier jumped from his foxhole, ran south along the river bank, and disappeared into the woods. Several minutes later approximately six Germans, including a lieutenant, ran toward the two Americans from the stream’s west bank. They asked if the Americans were armed and accepted their word that they were not. Through his interpreter, Major Berndt began to explain his mission when he heard another hail from across the river. This time it was an American soldier leaning against a tree and obviously wounded; a slit in his right trouser leg revealed a large field dressing on his thigh. “Hey, Major,” he called, appearing to be crying, “come over and get me.” Major Berndt replied that he could not come just then. A few minutes later two American aid men, each carrying a five-gallon water can, walked nonchalantly down the Kall trail and asked the major if they could fill their water cans at the river. He told them to go ahead and, if possible, to get the wounded American from the east bank.

When Berndt asked the German lieutenant for a truce to evacuate the wounded from the woods line and from Kommerscheidt, the lieutenant replied that all American wounded had been evacuated. There remained, however, the problem of the wounded in the log aid station. The German offered to evacuate these men, but Major Berndt declined, for fear of giving the enemy an opportunity to capture the American medical personnel. The lieutenant then said that evacuation vehicles could pass without interference from his men, but he could not vouch for his artillery fire because at the time the Germans were having communication difficulties with their artillery. With this arrangement, the two officers exchanged salutes, and Major Berndt and T/4 Wolters retraced their steps up the Kall trail, stopping at the aid station to report the results of their conference.

The two American medics who had gone to fill their water cans at the river succeeded in getting the wounded soldier from the east bank. When they reached the west bank again, some of the Germans who had been present at Major

Berndt’s conference assisted them in carrying the wounded man toward the aid station. The engineers dug in north of the trail saw this mixed group of Americans and Germans and opened fire. A shout from one of the medics—“Hold your –––– fire! We’re bringing in a wounded man”—stopped the shooting.4

Evacuation

While the truce arrangements were being conducted, the weasel and trucks with their load of American wounded farther up the trail to the west began their journey toward the rear. They moved without undue difficulty to the crest of the hill where the trail emerged from the western edge of the Kall Woods. Beyond this point the route was blocked by abandoned American vehicles. The weasel could get by, but the trucks could not. While the trucks waited, Lieutenant Morrison, 1st Battalion medical administrative officer, passed through with the weasel and five patients and reached Vossenack.

Major Berndt and T/4 Wolters returned from the Kall gorge on foot, reaching Vossenack well past noon. Lieutenant Johnson, the ambulance platoon leader, was waiting in the town with one ambulance and had others available in Germeter. Learning about the partial truce from Major Berndt, Johnson was concerned about the German artillery, which had been the principal reason for the failure of evacuation across the brow of the Vossenack ridge. His concern was tempered, however, by a realization that the continuing snowfall was steadily decreasing visibility—to American advantage. The lieutenant obtained a volunteer driver for his ambulance and made a test run out across the open ridge. The enemy-held hills were shrouded in a haze of falling snow, and Johnson knew then that his mission would succeed.

New difficulties had arisen at the western edge of the Kall woods where the loaded trucks waited on the blocked trail. A German captain and about ten German enlisted men had arrived on the scene.5 The enemy officer wanted to see the medical officer in charge aad talked at length with Captain DeMarco, 3rd Battalion surgeon. It was obvious that this German officer knew nothing of Major Berndt’s previous truce arrangements, and he insisted that only seriously wounded and medical personnel could be evacuated. He said that slightly wounded and nonmedical personnel (probably those men who had been retained as litter bearers after the withdrawal from the east bank) would be taken prisoner.

Lieutenant Johnson arrived with his ambulance, evidently while this discussion was taking place. The Germans gave him no difficulty as he loaded his ambulance with wounded. Returning to Germeter, he secured eight ambulances for completion of the task and led them back to the blocked trucks, arriving there about 1615.

As the eight ambulances were loaded, the Germans checked the seriousness of the patients’ wounds and the validity of the medics’ Red Cross cards. They allowed Lieutenant Muglia, 3rd Battalion

Evacuation of wounded over the muddy ground of the Hürtgen Forest.

medical administrative officer, to accompany the ambulances, but not the two battalion surgeons, Captains DeMarco and Linguiti, nor Chaplains Alan P. Madden and Ralph E. Maness. They were being held, the Germans said, because a large group of Americans whom the Germans had surrounded might need attention from both medics and chaplains.6 The German captain did agree that an ambulance might return about noon the next day for the four American officers. As the ambulances pulled away with the last of the American wounded from the aid station, men in the rear ambulance heard Chaplain Madden shout, “Come back for us tomorrow.”7

The surgeons and chaplains returned to the log dugout. Heavy shelling and occasional small arms fire in the area wounded still more Americans and increased the number of patients who gathered at the aid station. By the next day there were twelve casualties in need of evacuation.

The next day, 10 November, the officers went back to the top of the hill and again talked to the German captain. Now the German officer insisted he would not release them unless the Americans returned all the slightly wounded Germans whom they had evacuated and unless all the Americans in the area surrendered. As the parties conferred, they were shelled. The Germans ran for their foxholes and ordered the Americans back to the aid station.

That same morning the Germans sent Chaplain Madden into the 3rd Battalion, 109th Infantry, positions south of the Kall trail with a surrender ultimatum; it was refused. The next day they again sent the chaplain with an ultimatum; it too was refused.

The day of the second surrender demand, 11 November, a German medical officer at the bottom of the Kall gorge requested a truce in order that the Germans might collect their dead. Having had no contact with the German captain near the exit of the main supply route from the woods, this officer told the Americans that they could evacuate their wounded at the same time. Several litter teams that had reached the aid station on foot took advantage of the unexpected opportunity and evacuated their wounded via a roundabout route through the woods to the south. They thus avoided the hostile German captain and his men. Despite continued American and German artillery fire—for the truce was only between medics—the last casualties as well as the two surgeons and two chaplains finally reached the safety of the rear.8

Map 33 Plan for Closing Action 10 November 1944

Summary of Closing Action

On 9 November the troops of the 146th Engineers, who had gone into an assembly area after their infantry role in recapturing the eastern half of Vossenack, resumed work on rear-area roads and laid a mine field for the 109th Infantry on the eastern nose of the Vossenack ridge. The remainder of the 1171st Engineer Combat Group stayed in the Kall gorge as riflemen until 10 November when they also withdrew and began rear-area road maintenance.

The 112th Infantry Regiment was reorganized on 8 November with the addition of 515 replacements and was alerted to attack due north from Vossenack to seize the woods overlooking Hürtgen. When G-1 intervened because the 112th had such a large number of replacements, the 1st Battalion, 109th Infantry, was ordered to attack instead. (Map 33) Both the 1st Battalion, 109th, and the 12th Infantry (4th Division) attacked on 10 November to close up on the Hürtgen woods line. The 1st Battalion, 109th, succeeded partially after costly and determined enemy resistance. The 3rd Battalion, 109th, remained in the Kall gorge while the regiment’s 2nd Battalion held in Vossenack. Both units did occasional patrolling. To the south the 110th Infantry tried through 12 November to improve its positions and reduce the Raffelsbrand strong point, but its companies were so depleted and its attacks such feeble, piecemeal efforts that virtually no change in the line was effected. All these actions were the result of a directive issued orally by V Corps on 9 November and given written confirmation the next day. They were apparently designed to secure a line of departure

overlooking Hürtgen and to improve the 28th Division positions in general.9

The Enemy Situation

On 9 November the Germans changed their counterattack plans against the 28th Division. They returned to their original idea of cutting off the Vossenack penetration at its base by means of a drive against the penetration southwest of Hürtgen. On the same date the 89th Division and elements of the 275th Division relieved almost all of the 116th Panzer Division in the Kommerscheidt–Vossenack area, and the panzer division began to assemble in the vicinity of Hürtgen. During the night of 9-10 November a new boundary between the 89th and 275th Divisions was designated to run northeast just north of Bosselbach Farm. The 89th Division was charged with responsibility for the area from just north of Strauch up to the new boundary, although some elements of the 275th Division remained in the Raffelsbrand area. The 275th Division’s sector ran from the new boundary near Bosselbach Farm north and northwest to its original right boundary, but those elements in the Hürtgen area where the 116th Panzer Division was to attack were attached temporarily to the panzer division. German artillery was regrouped to support the 116th’s impending attack.

For three days, from 10 through 12 November, a Kampfgruppe of the 116th Panzer Division, seriously depleted by the Schmidt–Vossenack battles, attacked southwest of Hürtgen against the 12th Infantry but with only limited success. The 89th Division meanwhile reacted with stiff counterattacks against the 1st Battalion, 109th Infantry, in the woods north of Vossenack. To the 89th Division elimination of this American advance became “a point of honor.” Although the Germans did surround elements of the American battalion, a relief patrol broke through on 15 November to foil the German attempt at annihilation. This was the last major enemy development before the 28th Division was relieved and passed to control of VIII Corps.10

Relief of the 28th Division

When the 2nd Ranger Battalion was attached to the 109th Infantry and moved to the Germeter vicinity on 14 November, all elements of the 112th Infantry were relieved, and the regiment moved south into defensive positions in VIII Corps’ Luxembourg sector. The 110th Infantry was relieved by elements of the 8th Infantry and moved south on 17 November. Relief of the 109th Infantry was completed by the 8th Division on 19 November, and the entire 28th Division was relieved of responsibility for the Vossenack–Schmidt area.11

The Schmidt operation had developed into one of the most costly division actions in the whole of World War II and represented a major repulse to American arms. Exact casualty figures are difficult to determine because casualties were reported

by the month and the Schmidt operation covered only a portion of a month. However, after leaving this area, the 28th Division went to a relatively inactive sector of the VIII Corps line where casualties for the rest of November were admittedly few. The majority of the month’s casualties, therefore, can be considered to have occurred in the Schmidt operation.

Hardest hit of the three infantry regiments was the one that made the main effort, the 112th Infantry. It had 232 men captured, 431 missing, 719 wounded, 167 killed, and 544 nonbattle casualties—2,093 officers and men lost in all. Troops attached to the 28th Division suffered, at a conservative estimate, more than 500 casualties, while losses in the division itself for November were 5,684. The one-division assault, therefore, had claimed a toll in killed, wounded, missing, captured, and nonbattle casualties of more than 6,184 Americans.12

No accurate comparison between German and American casualties can be made because German casualties are purely an estimate and for a shorter period. From 2 November through 8 November, 913 German prisoners were captured and an estimated 2,000 enemy casualties of all types were inflicted. On the basis of these figures it is apparent that American losses were much higher, approximately 3,000 more than the German.13

American matériel losses in the Schmidt action included sixteen out of twenty-four M-10 tank destroyers of the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion and thirty-one out of fifty medium tanks of the 707th Tank Battalion. Other victims of both enemy fire and the treacherous terrain included bulldozers, trucks, weasels, 57-mm. antitank guns, machine guns, mortars, and individual weapons.14 Figures on expenditure of artillery ammunition are available only for the period 2 November through 8 November. Counting tank and tank destroyer ammunition fired

indirectly and 4.2 chemical mortar ammunition, 92,747 rounds were expended.15

The original primary mission of the 28th Division had been to capture Schmidt and be prepared to advance to the southwest to assist the 5th Armored Division in taking the Strauch–Steckenborn area. The division was also to guard against counterattack from the north, secure a line of departure for a later attack by another division against Hürtgen, and secure another supply route to the south for the later attack on the Strauch–Steckenborn area. Although the 109th Infantry, assigned the mission on the north, did guard against counterattack, before it was called out to assist the 112th Infantry it had not succeeded completely in securing the desired line of departure for the proposed Hürtgen attack. The 110th Infantry to the south, attempting to secure the Schmidt–Strauch road in preparation for a later division advance to the Strauch–Steckenborn area, experienced a bloody, costly action that netted little except the capture of Simonskall. The 112th Infantry, making the division’s main effort, captured Schmidt but failed to hold it. The regiment’s only final accomplishment in terms of territory gained was the capture and defense of Vossenack, and in that action the unit had assistance from the 146th Engineers acting as riflemen. The 109th Infantry, in this same sector, did later establish itself in the woods north of Vossenack and along the trail in the wooded Kall gorge.

The mission of drawing enemy reserves to the area and away from a planned major First Army attack in the VII Corps zone to the north had been accomplished—all too well. Because of weather conditions, the VII Corps attack failed to get off on time, and air support failed to keep enemy armored reserves from the Schmidt area. Thus the 28th Division, making the only attack in progress on both the First and Ninth Army fronts, was left to the wrath of enemy reserves. By the time the VII Corps attack was launched, the 116th Panzer Division had returned to reserve and the 89th Division had taken over defense of Kleinhau–Brandenberg–Bergstein.

A group of V Corps officers, designated by the corps commander to study the action soon after the battle, concluded that, despite the divergent nature of the Schmidt operation, tactical planning was sound under the existing circumstances. Many of the successes won by American arms from the Normandy landings onward had begun as gambles. Schmidt was a gamble that failed. A number of factors had combined to bring failure, not the least of which were the violent German reaction, adverse weather conditions, an inadequate and unprotected main supply route, lack of regimental and divisional reserves, the wide frontage and divergent missions, and the inability to neutralize the Brandenberg–Bergstein ridge. In the opinion of the V Corps commander, Lt. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, few if any infantry divisions could have achieved more against these obstacles than did the 28th.16

The town of Schmidt remained in German hands until the 78th Infantry

Division captured it in February, 1945—after the Brandenberg–Bergstein ridge had been captured. The 78th Division’s attack came down the Strauch–Schmidt road and was assisted by a simultaneous attack from the direction of Brandenberg–Bergstein.17

As for the 28th Division, from Schmidt it moved south into Luxembourg along the grand duchy’s border with Germany. For more than two months this relatively inactive sector of the Western Front had been used for the orientation of new divisions and the recuperation of old. In December, less than a month after arrival of the battered division for rest and reorganization, the Germans wrote a sequel to the Schmidt battle, casting the 28th once again in a tragic role. This time the division lay directly in the path of the enemy’s counteroffensive in the Ardennes.