Part Four: The Bomb

Blank page

Chapter 24: The Los Alamos Weapon Program

The ultimate focus of the Manhattan Project’s manifold activities – production of fissionable materials; procurement of raw materials, manpower, and process support; establishment of security, health, and safety programs; and construction of atomic communities – was the Los Alamos Laboratory weapon program. Actively under way by the spring of 1943, its major objectives, as General Groves succinctly summarized them, were “to carry on research and experiment[s] necessary to the final purification of the production material, its fabrication into suitable active components, the combination of these components into a fully developed usable weapon, and to complete the above in time to make effective use of the weapon as soon as the necessary amount of basic material has been manufactured.”1

Planning Phase

Whether the Army could attain the objectives of the Los Alamos weapon program greatly depended on its ability to build and operate a major scientific and engineering organization at the isolated New Mexico site. Because the technical problems corollary to bomb development were in many respects unique, few precedents existed to guide Manhattan’s military and civilian scientific leaders in organizing and staffing the bomb laboratory. Hence, in carrying out these first steps of the weapon program, they adopted a generally pragmatic and ad hoc approach.

Efforts of Groves and Oppenheimer

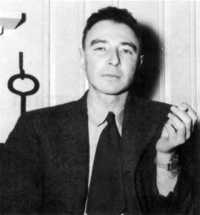

Because of the need for maximum security, the atomic leaders concluded that a normal Corps of Engineers administrative organization – district engineer supervision and control, area engineer liaison and support – was not feasible at Los Alamos. For this reason, Groves himself assumed many functions of both offices. Working closely with the civilian head of the bomb laboratory, J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Manhattan commander not only exercised broad policy control over the weapon program but also regularly intervened in day-to-day operations, using telephone and teletype means of communications and frequent personal visits to maintain

J. Robert Oppenheimer

surprisingly close supervision. Though his most important contact was through Oppenheimer, he also acted through the facilities of the Albuquerque District and the Los Alamos military organization, as well as through certain individual Army and Navy liaison officers assigned to the weapon program. With this administrative arrangement in effect, the role of the prime contractor, the University of California, was narrowly confined to the details of business management and procurement for the laboratory.2

The personal leadership of Groves and Oppenheimer was particularly evident in some of their early administrative actions. In late January 1943, Groves selected Lt. Col. John M. Harman, a Corps of Engineers officer with a degree in civil engineering, as the first commanding officer of the Los Alamos post. At the same time, he requested the War Department’s Services of Supply to furnish and train military personnel for the post, specifying allotment of military police, engineer, and medical troops in time for activation of Los Alamos as a Class IV installation on 1 April 1943. In consultation with James B. Conant, he drew up a statement on the organization, function, and responsibilities of the various elements that would be located at Los Alamos, clearly delineating the division of local responsibilities between Oppenheimer, the scientific director, and Colonel Harman, the post commander. In meetings with University of California officials during February and March, Groves worked out business and procurement arrangements for Los Alamos, including establishment, for reasons of security, of the laboratory’s main procurement office in Los Angeles.3

Meanwhile, Oppenheimer was visiting various universities and institutions to enlist a cadre of scientists for his laboratory. But the shortage of scientific manpower, caused by the special needs of other war projects, and certain misgivings about the restrictive military character of the new laboratory hindered his initial efforts. To alleviate the scientists’ doubts on this score, Oppenheimer reassured prospective recruits with a promise from Conant and Groves that, for at least the first phase of the program, the laboratory would function on a strictly civilian basis and that the staff would not be militarized until actual fabrication of a weapon began.

This approach improved Oppenheimer’s recruiting efforts, especially among scientists already engaged in some aspect of atomic research. Starting with members of Manhattan’s fast-neutron team – it included university scientists from California (Berkeley), Minnesota, Wisconsin, Stanford, and Purdue – Oppenheimer added other scientists from the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory, among them the Hungarian-refugee physicist Edward Teller, and from Princeton University’s now discontinued program for isotopic separation of uranium. In addition, he attracted a scattering of scientists from other universities – Rochester, Illinois, Columbia, and Iowa State – and from other research organizations, including the Geophysics Laboratory at the Carnegie Institution, the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), the Army’s Ballistic Research Laboratory at Aberdeen, Maryland, the National Bureau of Standards, and the Westinghouse Research Laboratories in Pittsburgh.4

Oppenheimer and a skeleton staff of scientists arrived at Los Alamos in mid-March, despite the unfinished state of the community and technical facilities. In the ensuing months, however, there was a rapid increase in the influx of personnel, both military and civilian. By early June, Los Alamos had more than 300 officer and enlisted personnel and almost 460 civilians (160 civil service employees and 300 scientists and technicians on the University of California payroll). Finally, with sufficient personnel on hand, both the new post commander, Lt. Col. Whitney Ashbridge – Groves had relieved Colonel Harman in May because of his inability to get along with some of the scientific leaders – and Oppenheimer turned to the many problems of completing their respective organizations, especially those relating to establishment of essential coordination between the laboratory and post administrations. To guide them in this task, they had at least the initial outlines of the unfolding weapon program.5

The April Conferences

Basic planning for developing and testing an atomic weapon was the responsibility of a formal steering board, set up by Oppenheimer in late March. The board began its work in early April and conducted a series of orientation and planning conferences throughout the month. During the orientation conferences, held in the first half of the month, the board provided the newly arriving laboratory staff members with state-of-the-art information on atomic energy as a weapon of war. During the planning conferences, held in the last half of the month, the board and a group of scientific professionals reviewed the nuclear physics background and established research objectives for the weapon program. Taking part is these meetings were selected laboratory staff members, visiting consultants (Isidor I. Rabi from MIT’s Radiation Laboratory and Samuel K. Allison and Enrico Fermi from the Metallurgical Laboratory), and members of a special reviewing committee.6

The April conferences made it very clear that what was known about the explosibility of uranium and plutonium and the design of an atomic weapon was still highly theoretical. The one area in which nuclear research had progressed significantly beyond the theoretical was in the chemistry and metallurgy of uranium and plutonium, and this had occurred only because project scientists had had to conduct extensive research into this aspect of the two elements to provide the necessary developmental data for the fissionable materials production processes at Clinton and Hanford. In virtually every other aspect essential to bomb development – the experimental physics research; the design, engineering, and fabrication of bomb components; and the assembly and testing of a weapon – the essential work remained to be accomplished. What then precisely was known in April 1943?7

Theoretical research had established that a single kilogram of U-235 has a potential energy release of up to 17,000 tons of TNT. To achieve this release of energy there had to be a fast-neutron chain reaction, which was theoretically possible in uranium, plutonium, and certain other elements, but most feasible in active material composed largely of the isotopes U-235 or Pu-239. A fast chain reaction could occur only with the assembly of a sufficient quantity of active material in a configuration in which natural leakage of neutrons did not occur at so high a level that the chain reaction was quenched. An important step was to design a mechanism that would provide the proper configuration for attaining criticality upon detonation. Theoretical research had already given considerable attention to weapon design, but the major problem still to be solved was how to avoid prefissioning, or predetonation.

Addressing this problem, the conferees reviewed and discussed several

weapon assembly methods as possible solutions. They immediately discounted those methods that required either too much active material (as in the autocatalytic, or self-assembling, method) or employment of an atomic explosion to trigger fusion (as in a thermonuclear bomb using a mass of deuterium as the source of its energy). In their estimation the most feasible design was the gun-assembly method, comprised of a cannon in which an explosive-propelled projectile containing one portion of active material is shot through a second target containing another portion of material – thus achieving criticality.

The conferees were confident that the gun-assembly method, if properly engineered, would work with the isotope U-235, because of its properties; however, they were considerably less certain about its feasibility for Pu239, partly because the continued scarcity of this isotope had limited the amount of study that could be made of its chemical and metallurgical properties. Realizing the pile method of producing Pu-239 made that substance most likely to be the active material available in the largest quantities, the conferees were especially anxious to find a design suitable for its employment. Continued discussions indicated that the implosion concept offered the best promise of success for plutonium. In a weapon of this design, a quantity of active material in a subcritical shape would be surrounded with layers of ordinary explosive in such a way that, upon detonation, the active material would be compressed into a critical configuration and the fast chain reaction would take place. Later research revealed that the implosion design would produce an effective atomic explosion using considerably less active material than the gun method – a fact especially appealing to Manhattan leaders.

The April conferences provided Groves, Oppenheimer, and other Manhattan leaders with new insight into what the immediate emphasis and direction of the weapon program must be by identifying the specific research objectives that would produce the necessary data not only for timely design and fabrication of an atomic weapon but also for an understanding of its destructive effect. First, because information on the amount of damage that would result from an atomic blast was almost totally lacking, the conferees prescribed the collection of systematic data on the likely physical, psychological, and mechanical effects of an explosion of the magnitude of an atomic bomb – realizing, of course, that part of that data would have to await an actual test of an atomic device. Second, they outlined a schedule of theoretical studies, experimental physics, and research in chemistry and metallurgy that hopefully would furnish the data needed to substantiate what was already known concerning the explosive potential of U-235 and Pu-239, to measure precisely the critical mass of each, and to prepare the fissionable and other materials to be used in an atomic weapon.

Reliable estimates by the scientists in the uranium and plutonium production programs at Clinton and Hanford indicated that sufficient fissionable material for an atomic weapon would be available in about two years. Would the Los Alamos Laboratory be able to fabricate a

weapon within that time? Because the April conferences had failed to provide, except in very limited terms, concrete proposals for the organization and work of an ordnance program to carry out the actual design and fabrication of the weapon, it was to this subject that the special reviewing committee particularly addressed itself.8

Groves had established this committee in late March to ensure that the program and organization of Los Alamos were sound. Conant, acting as Groves’ scientific adviser in organizing the bomb project, had persuaded the Manhattan chief of its appropriateness by pointing out that scientists were accustomed to having such committees at universities and research institutions to help plan and evaluate research projects. Conant and Richard C. Tolman, vice chairman of the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), had helped Groves select the committee members: as chairman, chemist Warren K. Lewis of MIT; engineer Edwin L. Rose, who was director of research for the Jones and Lamson Machine Company; theoretical physicist John H. Van Vleck and chemist E. Bright Wilson, Jr., both from Harvard; and Tolman, who had agreed to serve as secretary. It was an experienced group, with all members except Rose already well informed on the atomic project. Lewis earlier had served as chairman of both the heavy water and DSM reassessment reviewing committees; Wilson and Tolman had been members of the heavy water group; and Van Vleck had participated as far back as 1941 in reviews of the uranium program.9

In its report issued on 10 May, the special reviewing committee endorsed most of the program discussed in the April conferences, outlining what it believed must be done in the way of theoretical and experimental work on the critical mass, efficiency of an explosion, and damage potentialities. Placing primary emphasis on the ordnance and engineering aspects of bomb development, the committee recommended that the laboratory expand the personnel and facilities needed to design and fabricate a weapon; it foresaw that the engineering program would more than double the personnel of the laboratory and require extensive facilities to test weapon components, and also that arrangements would have to be made with the Army Air Forces for assistance in bomb design and tests. The committee further recommended that the purification of Pu-239 “be made a responsibility of the Los Alamos group, not only because they must be responsible for the correct functioning of the ultimate weapon, but also because repurification will be a necessary consequence of experimental work done at the site.” This activity, hitherto centered at the Metallurgical Laboratory, would require a substantial

increase in personnel and facilities.

Consistent with its recommendations for expansion of the program, the reviewing committee also proposed appropriate organizational and administrative changes. While it was highly commendatory of Oppenheimer, it recommended that he should be provided with more administrative assistance in his immediate staff. It suggested appointing an associate director, capable of taking over direction of the project when Oppenheimer was absent, and establishing an administrative office, headed by a civilian who could maintain good working relations with the military administration.

The only aspect of the program’s administrative arrangements receiving severe criticism was procurement. While the Los Alamos procurement office appeared to be functioning reasonably efficiently, the key office in Los Angeles, under Army direction but manned largely by University of California personnel, was following procedures that were “unduly slow and cumbersome.” The delays could not be allowed to continue, because “not only the satisfactory progress of the work, but also the morale of the organization is dependent on an efficiently functioning procurement system.” A partial solution, the committee suggested, would be to establish a procurement office in New York for obtaining supplies and equipment from firms in the eastern part of the United States.10

Laboratory Administration

The recommendations of the April conferences and the special reviewing committee did not alter the basic plan for operation of Los Alamos, as worked out by Groves, Conant, and Oppenheimer in early 1943, but entailed a considerable expansion of the weapon program and support personnel. With these new guidelines, Groves and Oppenheimer set about to complete the organization of the laboratory and its administrative and technical staffs.

Administrative Organization

A number of factors complicated Oppenheimer’s task of forming a laboratory administration capable of maintaining the required liaison with the post administration, the necessary communication with other Manhattan District organizations, and effective control over the increasingly complex engineering activities of the bomb development program. One was security, particularly the requirement for compartmentalization, which placed severe limitations on communication within the laboratory, between the scientific and military organizations and between the laboratory and outside agencies. Another was the acute shortage of professional personnel experienced in dealing with the broad administrative problems of a research laboratory. A third factor was the lack of precedents to follow in organizing a laboratory staff for a program that ran the gamut from pure scientific research to the actual performance of

ordnance manufacturing operations. The combined effect of these factors was to place an unusually heavy administrative burden on the laboratory director and his immediate supervisory staff.11

Both Groves and Oppenheimer had been aware of the need for a strong administrative group in the director’s office, but their efforts in that direction had not been very successful. Their first choice for associate director was physicist Edward U. Condon from Westinghouse. Condon came in April 1943, but left almost immediately when he found himself in complete disagreement with security arrangements. As an experienced scientific administrator, he perceived the fundamental difficulty of trying to maintain essential liaison within the laboratory and with outside agencies under the project’s security system.12

With the strongly worded recommendations of the reviewing committee still very much on his mind, Oppenheimer immediately sought to replace Condon, as well as to fill the other key positions on his administrative staff. He was generally frustrated, however, in his efforts to recruit professionally trained, experienced scientific administrators. They simply were not available. He appointed a staff assistant to carry on the absolutely essential day-to-day liaison with the post administration, pending recruitment of a new associate director, but this position as originally conceived was destined never to be filled. In other key positions, he had to be satisfied with either scientists with little previous administrative experience or administrators with appropriate experience in nonscientific fields (for example, construction or business administration). Two of his appointees were physicists Dana P. Mitchell and Arthur L. Hughes, both of whom had no administrative experience in industry. Mitchell, selected to be procurement director, had been in charge of procurement for the physics department at Columbia University; Hughes, selected to be personnel director, previously served as chairman of the physics department at Washington University in St. Louis.

To assist Hughes with the ever-constant manpower problem, Oppenheimer enlisted the services of Brown University Dean Samuel T. Arnold, who was serving as a technical personnel consultant for the project, to recruit senior scientists and M. H. Trytten of the National Roster of Scientific and Specialized Personnel to recruit junior scientists and technicians. But the very nature of Los Alamos personnel requirements seemed to resist all attempts at a satisfactory solution, and Groves became convinced by the summer of 1944 that Hughes was not capable of solving the problem. The Manhattan commander took immediate action: He offered the position of personnel chief to Dean Arnold. Arnold demurred but agreed to go on a temporary basis until a replacement could be found. Eventually, on the basis of Arnold’s recommendation, Hughes was replaced with astronomer Charles

D. Shane, who had been working at the Radiation Laboratory in Berkeley.

It was mid-1944 before Oppenheimer had found suitable personnel for all positions – an administrative officer; heads of personnel, procurement, business, and patent offices, as well as of a health group, a maintenance section, and a library-documents room; and also an editor. He finally rounded out his administrative staff with appointment of a shops section chief in late 1944 and a safety group head in early 1945.13

Technical Organization

The technical organization of the laboratory took shape along the lines of the expanded program of research and development, as recommended in the April conferences and reviewing committee report. There were separate divisions for theoretical physics, experimental physics, chemistry and metallurgy, and ordnance. Within each division were a number of working groups or teams, each devoted to a particular aspect of bomb research or development. For example, the theoretical division had a diffusion problems group; the ordnance division had an implosion experimentation group; and the chemistry and metallurgy division had a uranium and plutonium purification group. Leaders of the groups reported to their division leaders and the division heads reported directly to Oppenheimer. As the work of the laboratory progressed, groups completed their projects and disbanded, and new groups formed to take up investigation of new problems.14

To direct the complex activities of the laboratory’s technical divisions, Oppenheimer relied chiefly upon the assistance and advice of a governing board and a coordinating council. The governing board, comprised of seven to ten administrative and technical staff heads, began as an advisory group but gradually evolved as a policy and decision-making body, its primary function being to assist Oppenheimer in coordinating the various scientific and engineering facets of the weapon program. Unlike the governing board, the coordinating council did not ordinarily concern itself with policy. Comprised of scientists and technicians who were group leaders or higher, the council provided a channel of communication between the second-level staff and the governing board and primarily functioned as a forum for interchange of information and opinion on current developments in the various divisions.15

Keeping the staff scientists abreast of the work going on in the various technical divisions, in Oppenheimer’s opinion, was indispensable to the success of the weapon program. To facilitate this situation, Oppenheimer, with approval of the governing board, established in May 1943 a weekly colloquium

for all laboratory staff members. General Groves had accepted the coordinating council as a necessary risk to security, but when he heard of the colloquium, he immediately protested to Oppenheimer that he considered it to be a “major hazard.” Oppenheimer defended the colloquium as an effective tool: Giving the scientific staff adequate information, he believed, would actually enhance security, for the scientists would achieve a better understanding of the necessity for secrecy. Groves decided to defer to Oppenheimer’s wishes and let the colloquium continue, having concluded that the most important reason Oppenheimer wanted a colloquium was not to provide information but “to maintain morale and a feeling of common purpose” in his scientific staff.16

The Military Policy Committee supported Groves’ views concerning the potential security risk of the Los Alamos colloquium. Seeking a solution to the broader issue of which the colloquium was symptomatic – how to bolster the morale of all project scientists by getting them to accept the necessity for security restrictions – the committee decided that the problem was sufficiently serious to warrant using its trump card, a letter from the President himself to the scientists. In late June, OSRD Chairman Vannevar Bush took advantage of an appointment with Roosevelt to secure his approval for the proposed letter. The President agreed enthusiastically, and Conant drafted an appropriate communication for Roosevelt’s signature.17

At the July meeting of the colloquium, Oppenheimer read the President’s letter to the assembled scientists. The scientists, as a staff member subsequently recalled, seemed much encouraged by the President’s expression of satisfaction with their “excellent work” thus far, his assurance that the atomic project was of great significance to the war effort, and his indication of confidence in their “continued wholehearted and unselfish labors” toward successful completion of the project. They also appeared to listen attentively to the President’s explanation of why “every precaution [must] be taken to insure the security of your project,” and his assumption that they were “fully aware of the reasons why their endeavors must be circumscribed by very special restrictions.” Although the presidential letter undoubtedly achieved its twofold purpose, Oppenheimer chose not to regard it as a directive to discontinue the colloquium. But he did carefully screen those permitted to attend it and otherwise tightened security arrangements for its sessions.18

Manhattan’s original concept that Los Alamos should function in complete isolation obviated the laboratory’s

having any regularly established channels of communication with other Manhattan District or outside organizations. Consequently, whenever the laboratory required technical information from these sources, it had to obtain special permission from General Groves’ Washington office. This ad hoc system remained the basic policy throughout the war, although Groves had to grant some limited exceptions to it. For example, in June 1943, he allowed Los Alamos scientists not only to correspond but also to visit certain members of the Metallurgical Laboratory to secure specified data on fissionable materials and other chemicals. And again in November, he consented to let Oppenheimer make a one-time visit to the Clinton plants after the governing board at Los Alamos had indicated repeatedly that there were going to be serious delays if someone at the laboratory did not secure information on the production schedules for fissionable materials.19

The project’s security system was again severely tested in early 1944, when a reorientation of the weapon program from theoretical and experimental research to ordnance and engineering problems necessitated increased liaison between Los Alamos and outside agencies. With strict compartmentalization still in effect, many of the laboratory staff members who required liaison with civilian agencies resorted to a variety of clandestine devices, such as using blind addresses and NDRC identifications and requesting technical reports through Tolman’s NDRC office in Washington, D.C. Security barriers were less formidable with other military elements, including the Army’s Ordnance Department, the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance, and the Army Air Forces.20

The weapon program reorientation provided Oppenheimer with an opportunity to form a more effective laboratory administration and organization in mid-1944. Aware of Groves’ general dissatisfaction with the existing organization, Oppenheimer realigned the administrative and technical components of the laboratory to reflect the new emphasis on engineering and ordnance development of atomic devices and, more particularly, on solution of the still formidable problems of implosion.21

One goal of the reorganization was to realign the scientific leadership of the laboratory so that its efforts were brought to bear on the most urgent phases of bomb development. By abolishing the governing board and dividing its functions between an administrative and a technical board, Oppenheimer eliminated unnecessary diversion of scientific leadership into housekeeping activities. A series of special conferences and committees to supervise particular aspects of bomb fabrication and testing ensured concentration of effort on key problems. The intermediate scheduling conference, which began meeting in August 1944, coordinated work of

those laboratory groups primarily concerned with the implosion bomb. The technical and scheduling conference, organized in December, undertook responsibility for programing experiments, use of shop time, and employment of active materials. The cowpuncher committee, so designated by laboratory officials because it was established to “ride herd” on implosion, met for the first time in March 1945. Other committees supervised weapon testing, procurement of detonators, scheduling of experiments with U-235, and development of initiators for implosion devices.

Both Conant and Groves realized that Oppenheimer was faced with complex industrial problems, yet he lacked an industrial expert on his staff to advise him on these problems. Consequently, in November 1944, Groves recruited the services of Hartley Rowe of the United Fruit Company, an outstanding industrial engineer who also had served with the NDRC and as a technical adviser to General Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. Rowe spent considerable time at Los Alamos in late 1944 and early 1945, guiding the technical divisions in the development of the procedures by which laboratory models could be converted into production units – the final phase in the weapon program.22

Oppenheimer’s reorganization directly impacted on the makeup and character of the laboratory’s technical divisions, transforming their focus from problems of research and experimentation to those relating to engineering and fabrication of the bomb. When measurement of the fission rate of plutonium indicated it could not be used in a gun-type bomb, technical activities shifted to development of an implosion-type bomb. Oppenheimer created new divisions and reduced the size of several of the older divisions. The theoretical and research divisions were retained, but most personnel and facilities were funneled into the ordnance, weapon physics, explosives, and chemistry and metallurgy divisions. In the spring of 1945, with fabrication of atomic devices proceeding apace, Oppenheimer established new off-site testing divisions: Project Alberta, to carry out all activities related to combat delivery of both the gun assembly and implosion bombs; and Project Trinity, to test-fire the first implosion bomb. While the new divisions comprised integral parts of the laboratory organization, division field teams from Los Alamos assembled and tested the various components of the weapons at other sites.23

Post Administration

The wartime character of the Los Alamos post administration – its organization and personnel composition – directly reflected the course of the bomb development program. Thus,

when Colonel Harman began to organize the post in the spring of 1943, he was guided by the then existing plans for a small technical laboratory with a supporting community of no more than a few hundred civilian and military personnel, but requiring an extraordinary degree of protective security and self-sufficiency. The modest organization he formed for this purpose was comprised of three major divisions. The Administrative Division looked after civilian personnel matters, provided various means for internal and external communications, maintained essential records, and audited post accounts. The Protective Security Division furnished post security and administered the military units assigned to Los Alamos, including Military Police (MP) and Provisional Engineer Detachments (PED). The Operations Division provided and maintained most of the community services – housing, utilities, commissary, and education and recreation facilities – in cooperation with the laboratory’s community council. Finally, a small, semiautonomous procurement group performed quartermaster functions; monitored contracts; and supervised property and warehouse operations, including the important Santa Fe receiving facility for laboratory shipments from the Los Angeles procurement office.24

Personnel for the original post organization began arriving on the Hill in late April 1943. By early June, Colonel Ashbridge, who had just replaced Harman as post commander, had a staff of 18 officers (including 1 WAAC officer). This staff directed the activities of slightly over 450 military and civilian personnel. There were more than 200 enlisted men in the MP unit, including attached medical and veterinary personnel; 85 enlisted men in the PED unit; 7 WAAC enlisted women; and somewhat fewer than 160 civil service employees. To meet increased demands for post services and support in the ensuing months, Ashbridge obtained additional PED and MP personnel from the 8th Service Command headquarters in Dallas. And with General Groves’ assistance, additional civil service and military personnel were procured through Corps of Engineers and other channels – for example, the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which furnished enlisted men with scientific and technical skills.25

Military personnel with scientific and technical training were assigned to the Manhattan District’s Special Engineer Detachment (SED), 9812th Technical Service Unit; the latter unit was a special engineer organization formed at District headquarters to retain scientific and technical employees subject to the draft and to recruit additional technically trained personnel for the project. Los Alamos began

receiving SED personnel in August 1943 and, because of Groves’ personal intervention, periodically thereafter. SED members worked at technical jobs for the laboratory, but were assigned to the post administration for rations and quarters.

By the end of the year, total personnel assigned to the post administration approached 1,100. The largest numerical increase was in civil service employees, nearly 450 as compared with some 160 in June. Increases in the military complement were more moderate. The number of MP’s grew from 190 to 300 and that of PED’s from 85 to around 200. With the establishment of a regular WAC Detachment at Los Alamos, the number of enlisted women was increased from 7 to 90. And because of the assignment of recent ASTP graduates to Los Alamos, SED strength figures increased from 300 to about 475.

Even with expansion of bomb development activities and its concomitant increases in post personnel, the basic structure of the post administration remained essentially the same, with only the Operations Division undergoing a moderate reorganization. In early 1944, when Manhattan assumed responsibility for all further construction and maintenance activities at Los Alamos, Colonel Ash-bridge strengthened the operating capability of the Operations Division by reorganizing it into two major sections – one for community construction and maintenance, the other for technical area work – and by recruiting more carpenters, bricklayers, plumbers, painters, electricians, and common laborers.

Increased demands for new technical-type construction soon outran the capabilities of the division, so Manhattan engaged another professional construction contractor, Robert E. McKee of El Paso. In spite of this major change, Colonel Ashbridge decided to retain the dual organization of the division, which had the security advantage of limiting access to the sensitive technical area to one group of workmen. But in early 1945, with the decision to retain McKee on a permanent basis to perform construction services at Los Alamos, the new post commander, Col. Gerald R. Tyler, rejected the dual organization and reverted to a unified structure. In this reorganization, which remained in effect until after completion of the wartime program, Tyler set up separate sections for contractor construction and administration, post construction and maintenance, and post engineer services.26

The Army’s principal role at Los Alamos, as well as elsewhere in the Manhattan Project, was ensuring effective administration and operational efficiency. In the main, this was achieved through the personal cognizance and direct action of the post commander. As the military administrator, the post commander played a key role in arranging military deferments for technical employees of the University of California, which included most of the scientists and technicians, and in monitoring the shipments of fissionable materials to Los

Alamos and the transmission of documents containing technical information from other parts of the Manhattan District. Coincident with his general supervision of post procurement and construction and maintenance activities, he consulted with key members of the laboratory administration, especially Oppenheimer and Capt. William S. Parsons, the naval gunnery officer in charge of the laboratory’s ordnance group. These consultations increased in frequency as program emphasis shifted from theoretical and experimental research to ordnance and engineering problems and requirements expanded for construction of new technical facilities and procurement of additional materials and equipment.27 Factors endemic to the atomic project, however, presented major obstacles to achievement of an efficient procurement system at Los Alamos. Among these were the atomic reservation’s location, more than a thousand miles from any major market and distribution center; security requirements that necessitated time-consuming, roundabout routing of the bulk of procurement through Los Angeles and elsewhere; and the highly technical and often unique character of many of the items to be procured. Another factor was the University of California’s insistence that all matters of purchasing and payments must be administered directly by members of the university business staff. But because the Army would not permit university employees at Los Alamos, the project located its main purchasing office in Los Angeles.28

In the face of these obstacles, Groves, Lt. Col. Stanley L. Stewart of the Los Angeles procurement office, and Army procurement personnel at Los Alamos worked with University of California officials to increase procurement efficiency. Groves maintained direct and frequent contact with the Los Angeles Area Engineers Office, established in early 1943 to supervise University of California procurement personnel. He sanctioned the opening of branch purchasing offices in New York and Chicago to provide the laboratory with direct access to eastern markets, saving time and reducing paperwork for the Los Angeles office. Army and laboratory procurement officials at Los Alamos worked out an arrangement for requisition of certain available items locally through the post supply organization.

As the volume of required materials increased dramatically in late 1944, Groves authorized a request by the laboratory’s ordnance division to set up a separate procurement group. The Army officer supervising this new procurement channel maintained an office in Detroit, which was an important source for many of the bomb components. He also made frequent use of the California Institute of Technology’s experienced procurement personnel at its Project Camel site. In spite of all these efforts, the flood of last-minute requisitions for the implosion weapon test in the spring of 1945 created threatening delays. Oppenheimer convened an

emergency meeting of project procurement officials at Los Alamos, and they agreed to increase procurement personnel and salaries, to establish direct communications between the New York and Chicago offices, and to require improved drawings and specifications in requisitions from the laboratory.29

The reorientation and expansion of bomb development activities eventually created more and more opportunities for a surprisingly large number of the military personnel assigned to the post administration to contribute directly to the technical side of the weapon program. A number of WAC enlisted personnel, for example, moved from strictly clerical jobs in the laboratory to technical work, when scientists found they had the requisite skills or training. Similarly, several officers on the post commander’s staff came to devote most of their time to essentially scientific and technical work. The post legal officer in the Administrative Division, Capt. Ralph C. Smith, found that his principal assignment was solution of patent problems, and several engineer officers who happened to have the necessary training or background in chemistry, metallurgy, or physics worked extensively with scientists and technicians in the laboratory. Other post staff officers worked full time in the development and administration of outlying test areas. Maj. Wilber A. Stevens, for example, who began in 1943 as head of the Operations Division, eventually was spending all his time supervising projects at outlying sites; acting as a liaison officer between technical and military personnel; and assisting in coordinating the work of group leaders in the laboratory. Stevens’s subordinate, Captain Davalos, the post engineer heading the division’s Technical Area Section, also became deeply involved in the complexities of the technical program in the course of helping to plan and carry out construction and maintenance for the laboratory.30

The post commander, too, tended to be drawn into more and more direct concern with technical problems. In the earliest period, lack of adequate liaison and General Groves’ policy of dealing personally with the technical program had excluded the post commander from knowledge or participation. Gradually, however, Colonel Ashbridge and members of the laboratory staff developed avenues for more effective liaison. Oppenheimer’s May 1943 appointment of a special assistant on his staff to take responsibility for liaison with the post administration had opened one avenue of communication, and Ashbridge’s assignment to membership on the laboratory’s administrative board in July 1944 provided further opportunity for the post commander to keep informed of developments in the technical program.

General Groves, with the support of his Washington staff, continued throughout the war to be perhaps the single most effective liaison channel

Lt. Col. Curtis A. Nelson

between the laboratory and post administrations at Los Alamos. By frequent telephone calls to Oppenheimer. Ashbridge (later Tyler), and Parsons, as well as to Colonel Stewart in Los Angeles, the Manhattan commander kept in close touch with both community and technical developments. As with other key installations of the Manhattan Project, Groves supplemented his telephone calls with teletype messages, memorandums, and, about once every two or three months, an inspection and consultation visit lasting two or three days. In addition, Parsons visited Groves in his Washington office about once a month and Oppenheimer, Ashbridge, and Stewart less frequently.31

To facilitate overall administration and operation of the weapon program, Groves took special interest in matters of security, construction, and materials and manpower procurement. Of note are his personal efforts to expedite manpower recruitment for Los Alamos. In October, for example, following Conant’s expression of alarm at the continuing deficiencies in the senior scientific staff, Groves worked out with a reluctant Compton for the transfer of about fifty Metallurgical Project physicists. At the same time, he brought pressure upon the District’s Personnel Division chief, Lt. Col. Curtis A. Nelson, to maintain a flow of junior scientists for the laboratory’s SED unit. His prodding of Nelson proved effective, for by early 1945 nearly half the working personnel on the Hill was in uniform. Groves’ frequent pleas to manpower authorities in Washington to supply the New Mexico installation with more skilled workmen, especially machinists, were less productive. Hence, when Oppenheimer uncovered an opportunity in late 1944 to establish a liaison with the California Institute of Technology’s well-manned Navy rocket development group in Pasadena, Groves personally intervened to expedite an arrangement with the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance that made, under a newly created Project Camel, both skilled workers and surplus facilities available to the laboratory.32

Although manpower conditions remained less than satisfactory throughout the war, the Manhattan commander’s efforts directly contributed in some measure to relieving personnel deficiencies at Los Alamos. Thus in the summer of 1945, the number of post personnel continued to increase, though not at a significant rate. The SED unit had about 1,400 enlisted personnel by July. Others in the post administration numbered 1,260 8th Service Command troops (500 MP’s, 500 PED’s, 260 WAC’s) and more than 2,000 civilian employees. This total of more than 4,900 – with 1,300 scientists and technicians at the laboratory and some 500 construction contractor personnel – gave Los Alamos a total working population of approximately 6,700. At this juncture, as the bomb development program moved rapidly toward the actual test of an atomic device, all at Los Alamos were concentrating their efforts on the technical preparations for this climactic event.33