Chapter 10: The Civilian Defense Mission

One of the first steps taken by Hon. Fiorello H. La Guardia as Director of the Office of Civilian Defense, after that office had been set up, was to request specifically that the War Department provide for the training of ten successive classes of civilians to be selected by his office.1 The Secretary of War approved La Guardia’s request to set up schools for the training of civilians, and on 21 May 1941 directed the activation of the first of these schools.2

CWS Prewar Interest in Civilian Defense

CWS interest in civilian defense had extended back for some years. As early as 1930, Col. Charles R. Alley, a CWS officer who had spent some time on military attaché duty and who was impressed by the importance being accorded gas defense in European programs for civilian protection, made a detailed study of measures for protection of American civilians against enemy attack. Colonel Alley’s proposals were the first of a number of recommendations presented to the War Department General Staff during the 1930s covering aspects of civilian protection over which the CWS felt concern. During this period the developing threat of aerial warfare against civilian populations was closely observed, particularly any means being perfected overseas to counteract the effects of the two types of agents which the CWS was charged by law with developing and producing—war gases and incendiaries. It was the view of the Chemical Warfare Service that the Military Establishment had an inescapable responsibility to the civilian in

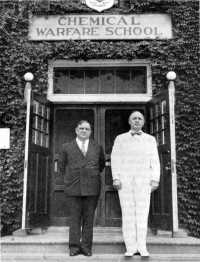

Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, New York City, first Director of Civilian Defense, left, and Maj. Gen. William N. Porter, Chief of Chemical Warfare Service, at graduation of first civilian defense class. Chemical Warfare School, Edgewood, Maryland, 12 July 1941.

the matter of protection against air attack and that this responsibility should be defined.3

The reaction of the General Staff to the several proposals submitted by the CWS during this period was mixed. The dominant staff view was that nothing should be done that would unduly alarm the general public on the hazards attending strategic bombardment.4 Americans were known to be sensitive to the implications of gas warfare; for this reason the War Department determined not to incur the charge of jingoism by emphasizing the danger of gas attacks. At the same time Colonel Sherman Miles of War Plans Division (WPD) felt that the matter should not be entirely neglected.5 The Chief, CWS, was accordingly directed in 1936 to prepare a pamphlet containing information that would be useful to military authorities responsible for carrying out measures of passive protection against aerial attacks.6 The Chemical Warfare Service was chosen for the task because its concern with both gas and incendiaries brought it more prominently into this field than other technical agencies of the War Department. In the preparation of this publication, the CWS was directed to confer with the Ordnance Department on the effects of explosive bombs, with the Corps of Engineers on the design of bombproof shelters, and with the Medical Department on related health measures. Coordination of views of all War Department bureaus that could contribute technical assistance to civilian defense was thus assured.

This document was duly prepared in the Office of the Chief, CWS, with the assistance of other branches. It was approved by the War Department and was reproduced by multilith process at the Chemical Warfare School in 1936 under the title, Passive Defense Against Air Attack.7 Only 200 numbered copies, bound in red covers and classified “secret,” were published. By War Department direction, copies of this 43-page pamphlet were transmitted to each corps area commander and to overseas departments where they were filed for use when needed.

With the publication of the passive defense pamphlet the General Staff dismissed, for the time being, further consideration of civilian defense. Yet during the next two years steady deterioration of the political situation in Europe led foreign governments to give increasing attention to problems of civilian protection. Full reports of these developments were obtained by the CWS through military attaches like Colonel Alley and from other sources. Early in 1939 Maj. Gen. Walter C. Baker again brought this matter officially to the attention of the War Department, proposing that military responsibility for the protection of U.S. citizens from aerial attack be more sharply determined. Among matters of concern to the CWS at this time were arrangements for production of gas masks for civilian use, agreement on channels for release of authoritative information that would allay undue alarm over war gases and incendiaries, and procedure for instruction of selected civilians in technical phases of air raid precautions. General Baker pointed out that “until a general plan has been adopted the chemical plan cannot be developed.”8 The recommendations he presented in this letter provided the basis for an outline plan for the Army’s approach to civilian defense, a plan prepared by the War Plans Division after the German invasion of Poland.9 This staff study represented the first frank recognition by the War Department of responsibility in the matter of civilian defense and provided the groundwork for a realistic approach to problems that were to loom large during the next four years.

In reviewing the WPD study after it had been referred to the Chemical Warfare Service for comment, General Baker recommended particularly that the development of civilian instructors and the specialized training of selected civilians be undertaken by the War Department.10 This proved to be the precise direction in which extensive training activities of the CWS were to tend less than two years later.

Preparation of Instructional Material

In June 1940 the New York City Fire Commissioner, John J. McElligott, sent a representative to Washington to confer with the Chief, CWS on the problem of familiarizing fire fighters with methods of combating gas and

incendiary attacks. This and similar requests from responsible municipal authorities for technical assistance on civilian defense problems were duly reported by the CWS to the War Department and were instrumental in getting the department to initiate the compilation of needed instructional and training literature.11 The CWS was directed to prepare a pamphlet “to furnish the local Civil Defense organization with information as to the methods employed in Chemical Warfare and the means of combating them.”12 This manuscript, eventually published by the Office of Civilian Defense as Protection Against Gas (GPO, 1941), served as a wartime guide for this type of civilian training.

Behind the comprehensive group of textbooks, handbooks, and planning guides eventually published by the OCD is the story of the peacetime interest of a senior CWS officer in civilian defense matters. For several years preceding World War II, Col. Adelno Gibson had collected standard manuals and other writings on civilian defense from most of the countries of Europe. Colonel Gibson communicated his enthusiasm for the subject to others. In 1938, as Second Corps Area Chemical Officer, he presented to senior Reserve officers in the New York area a problem then being studied by the CWS. This involved the provision of authentic information for the general public on the effects of gas and incendiary bombing.13

One of these officers, Lt. Col. Walter P. Burn, an advertising executive, became interested in this problem and decided to make it the subject of a thesis which he was about to write in preparation for promotion. The thoroughness with which Burn developed this subject and his novel approach to the popularizing of instructional material impressed CWS officers who had the matter under study. Burn’s thesis was available at the time the Office of Civilian Defense was created and it was accordingly supplied to that Office for study. As a result, the OCD requested the services of Colonel Burn and made him chief of the Training Division. It was largely due to Colonel Burn’s ability and initiative that the impressive schedule of OCD training publications was launched so promptly. As chief of the Training Division, OCD, Burn was responsible for the preparation of training

Gas defense training for civilians at the Chemical Warfare School, Edgewood, Maryland, 1941.

literature, manuals and films; the design of insignia and special uniforms; the recruitment of skilled writers and artists who served on a voluntary basis; and the enlistment for special missions of national organizations such as the American Legion, the Boy Scouts, and the Red Cross.14

The incendiary bombing of British urban centers, which had become extremely ominous by the late summer of 1940, was viewed with special apprehension by the U.S. citizens on the Altantic seaboard. New York City sent technical observers to England to obtain first-hand information on combating incendiary fires. Increasingly urgent calls upon the War Department for technical data on which to base defensive planning finally forced it to direct that, pending completion of official instructional literature, the best information available should be issued to civilian authorities.15 The War Department was moving cautiously but steadily toward full cooperation

with civilian agencies charged with protection of U.S. citizens against aerial attack.

In line with this approach, the CWS, at the request of representatives of the National Board of Fire Underwriters, conducted a demonstration at Edgewood Arsenal on 9 October 1940, at which magnesium and oil incendiary bombs were ignited and extinguished.16 This demonstration was the first of hundreds staged by the CWS during the war to inform civilians about the character of incendiary bombs and the methods of handling them.

As another important step in preparation for more active participation in the civilian protection program, the Chief, CWS, was directed in February 1941 to prepare a short course of instruction to be given on a volunteer basis to representatives of fire departments of large cities.17 An outline for a three-day course was prepared by the Chemical Warfare School in which instructional time was evenly divided between the handling of incendiaries and protection against war gases.

The school staff then proceeded to develop a more extensive instructor-training course intended to qualify selected civilians for the task of teaching volunteer workers at local levels. In a sense, the Army had to provide such a course as a measure of self-defense. It was clear that civilian officials would look to the military for technical instructions upon which to base the more general training of civilians in connection with the national air raid precaution program that the United States would doubtless be obliged to adopt. It was equally clear that the Army, even at the beginning of 1941, was much too busily employed in military training to embark on an extended scheme for the training of civilians. A two-week course for a limited number of carefully selected top echelon civilians appeared to provide a solution which was within the ability of the War Department and which at the same time would enable it substantially to satisfy the need for disseminating authentic doctrine on the more technical aspect of civilian defense.

The Chemical Warfare School made a careful study of this subject and early in 1941 developed a course of instruction which promised to meet these requirements. As originally developed at the school this course included:

a. Incendiaries (22 hours) : To afford technical instruction in characteristics of and in methods of coping with incendiary bombs.

b. Gas defense (26 hours) : To acquaint students with war gases likely

to be used against noncombatants and with methods of protection against such agents.

c. High explosive bombs (17 hours) : To afford familiarity with the action of HE bombs and with practical measures of protection from their effects.

d. Training methods (10 hours) : To provide practical and theoretical instruction in training of local civilians in air raid precautions.

School Training at Edgewood Arsenal

The Office of Civilian Defense took such an interest in the course set up at Edgewood in June 1941 that it sent steno-typists to record the lectures. OCD had to coordinate these lectures with the texts and illustrations which it prepared. For that reason, and also because the OCD was getting numerous requests to visit Edgewood from governors, mayors, and other officials, as well as from writers interested in Civilian Defense, General Gasser on 21 July 1941 requested the Secretary of War to designate a liaison officer between Edgewood Arsenal and the Office of Civilian Defense.18 After consultation between Maj. Gen. William Bryden, Deputy Chief of Staff and General Porter, Chief, CWS, 1st Lt. John N. Dick, a CWS Reserve officer called to active duty in 1940, was appointed to this post.19 Dick had formerly been Mayor La Guardia’s personal representative in Washington and was consequently no stranger to the Director of the Office of Civilian Defense.20 At the same time Dick was named liaison officer he was made chief of a new activated Civilian Protection Division, OC CWS. In July 1942 this division was redesignated a branch.21 That same month Lieutenant Dick was succeeded by Col. George J. B. Fisher as chief of the branch and in July 1943 Colonel Fisher was succeeded by Lt. Col. Willard A. Johnston. In the May 1943 reorganization of the Chief’s Office the Civilian Protection Division became a branch of the Training Division.22 Late in 1943 the branch

was deactivated, because by that time the CWS civilian protection mission had been accomplished.

The accommodation of civilian classes at the Chemical Warfare School during the summer and fall of 1941 did not impose an undue strain on school facilities. As has been indicated, the school at that particular period was not being fully utilized in the training of CWS personnel. However, the Chief, CWS, was convinced that all existing capacity of the school, and much more, would soon be needed for military training. While civilian defense training was accepted as a necessary contribution to an aspect of national defense in which the CWS had long been interested, it was clear that arrangement would have to be made for eventually carrying forward this work at other locations. General Porter in August 1941 accordingly sent two officers to survey sites where similar schools of instruction could be established. As a result of this survey, four additional locations for the future conduct of civilian defense training were tentatively selected in Texas, California, and Illinois.

In the eleven classes conducted at Edgewood Arsenal prior to 7 December 1941, 466 students from thirty-seven states were graduated. Out of this relatively small group came many leaders to head civilian defense bodies in every section of the country after war was declared. At the same time these prewar classes provided invaluable experience in working out solutions to problems that were without precedent in American experience.

Instead of merely instructing in a few essentially military techniques, the school faculty soon found itself confronted with the task of expounding a new thesis—how civilians might survive in modern war. It was fundamental that civilian protection was self-protection; that civilians themselves must organize and operate their own defense setup. This doctrine had to be rationalized and to some extent it had to be qualified. Overlapping of military and civilian authority needed clarification, and areas where one superseded the other had to be defined. For example, military control of the air raid warning system, of handling unexploded bombs, and of area smoke screening all was mandatory—for reasons which had to be made clear. On the other hand, development of the warden system, of rescue parties, and of fire-fighting services were all matters within civilian jurisdiction.

These and similar procedures that fell under OCD control obviously had to be elucidated before groups such as were attending the classes. The school undertook, whenever possible, to have nonmilitary subjects taught by civilians. For this purpose, members of the OCD staff and other qualified speakers came frequently to Edgewood to lay before succeeding classes

Demonstration in decontamination procedures for civilians. Men in protective clothing and gas masks mark off gassed area. Chemical Warfare School, Edgewood Arsenal, Md.

matters of important civilian defense procedure. Yet there was never any question, either of this stage or later, that here was a U.S. Army school following military instructional procedures but adapting itself to the training of civilians.

The fact that the students were on a military reservation attending an Army school gave prestige to the instruction at a time when this was most needed. It was frequently noted that a young officer wearing a second lieutenant’s uniform would be listened to more respectfully than a speaker in civilian garb discussing a subject on which he was a nationally recognized authority. The confidence with which instruction was accepted was one of the rewarding features of this early training activity. Even though pedagogically the course may not have rated high at the beginning, this fact was

incidental since the students who had volunteered for this training were at Edgewood Arsenal to learn; and that is what they proceeded to do. To some extent it was a case of student and instructor learning at the same time and of each recognizing the other as pioneering in a new field. There was at first a great deal of lecturing and not enough group discussion and applied work. The tendency of the school was to emphasize, it may be unduly, those subjects which for years had been its specialty. Yet there was much praise and little criticism from the students who derived a feeling of direct and personal participation in preparation for war which they could have gotten in no other way.

For these early classes at the Chemical Warfare School, sessions began on a Monday morning and ended at noon on the second succeeding Saturday. A charge of $23.00 per student was made for meals during the twelve-day period. This and other incidental costs were usually paid by the municipality or corporation by which the student was employed although often these expenses were borne by the patriotic volunteer. A prorated charge of $60.00 per student covered cost of ammunition and other outright expenses incurred in connection with this instruction. Army appropriations were reimbursed to this extent by emergency funds made available to OCD, thus satisfying a legal restriction that military appropriations should not be expended in the training of civilians.

During the fall of 1941, in response to insistent demands, the Chemical Warfare School extended its civilian defense instruction into nearby areas. This step was taken as an aid in the protection of industrial plants against aerial attack, a matter of utmost concern at the time. The work involved demonstrations and seminars at Boston, Princeton, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. The course at Princeton consisted of a two-day session conducted for the special benefit of CWS Reserve officers who were preparing for active participation in the New Jersey state civil defense program.

Reserve officers contributed materially to the development of civilian defense at this early stage, especially in the East. Notable in this connection was the work of Col. J. Enrique Zanetti, a CWS Reserve officer and Columbia University professor, who wrote and lectured extensively on this subject and demonstrated the burning of incendiaries before many interested groups.23 Local officials charged with developing civilian defense

organizations very often pressed into service CWS officers who were acquainted with technical features of air raid protection.

The twelfth civilian defense class was enjoying its mid-course week end when the Japanese struck at Pearl Harbor. The final week of instruction for this class had to be conducted by a skeletonized staff because on 8 December the Chief, CWS (General Porter) , directed the school to provide a group of experienced instructors for an urgent training mission on the Pacific Coast. As the details of the Pearl Harbor disaster became known, fear grew that other shattering blows might be imminent. The Office of Civilian Defense was especially concerned over reactions in west coast metropolitan centers. The Chemical Warfare Service had at that moment the only organized staff of instructors qualified to direct the type of training that would quickly develop competent leadership in civilian defense at local levels. Accordingly the War Department was asked by the OCD to dispatch a group of officers to California for the purpose of undertaking the instruction of local leaders in civilian defense operations.

This request was immediately granted. A group of nine CWS officers, headed by Lt. Col. George J. B. Fisher, reached San Francisco on 13 December and after hurried consultation with the Commanding General, Western Defense Command, and the regional director of civilian defense, was prepared to commence its training mission. Employing blitz tactics and a condensation of the course developed at Edgewood Arsenal, simultaneous three-day classes of instruction were conducted at San Francisco and Oakland. One instructional party moved quickly north to Portland, Seattle, and Spokane, while the other proceeded south to Los Angeles, Long Beach, and San Diego.

Public interest ran high; enrollment constantly exceeded the 250 students each class was intended to accommodate. Large groups witnessed the demonstrations and control center exercises. College auditoriums, public academies, and civic buildings were made available for instructional purposes. War had found the west coast with civilian protection programs still inadequate and incomplete—a situation which citizens of all ranks now undertook to correct. Hearty cooperation was afforded each training party. The doctrine stressed was that knowledge plus proper organization would enable American citizens to withstand anything the Japanese could bring to bear against them. This philosophy had a tonic effect. When the CWS contingent returned east in mid-January it was with the feeling that a measurable contribution had been made toward relieving the shock of the initial impact of war upon the Western states.

War Department Civilian Protection Schools

The early desire of General Porter to relocate civilian training was influenced by two considerations. First, he wished to free facilities at Edge-wood Arsenal for strictly military usage. Secondly, the eastern location of the school was manifestly a handicap to students from the Far West. The latter circumstance was particularly disturbing to the Office of Civilian Defense. After the series of ten classes originally requested was completed on 28 November 1941 the OCD then asked that six more classes be conducted at Edgewood Arsenal, at the same time hoping that a number of additional schools would be established.

Already the Commission on Colleges and Civilian Defense had offered the cooperation of the nation’s colleges in the civilian defense program. OCD decided that the use of college facilities for civilian defense schools was desirable and accordingly arranged for a meeting between Dr. Francis J. Brown, executive secretary of the Commission, and a group of Army officers, to study this possibility. This meeting, held in Washington on 5 December 1941, made a number of proposals which OCD adopted and laid before the War Department. Among these were recommendations;

(1) that six branch schools, each with a capacity for fifty students, be established,

(2) that these schools be located in colleges well distributed geographically,

(3) that all schools be controlled and operated by the War Department, and

(4) that necessary funds be made available by OCD and U.S. Office of Education.24

The Chief, CWS, was in due time directed by the War Department to establish and operate these schools at locations selected by him.25

The two schools first established were opened on 15 February 1942 at Leland Stanford Jr. University (California) and at Texas Agricultural and Mechanical College—two of the four sites that had been selected tentatively by the CWS the preceding August. The next month a third school was ready to open at Amherst College in Massachusetts. Conduct of civilian instruction at the Chemical Warfare School terminated on 31 March 1942, by which time a fourth school was in operation at University of Maryland.26 The opening in June of schools at the University of Florida, Purdue University (Indiana), and finally at the University of Washington (Seattle) completed the original program as proposed by the OCD.

It was necessary to make a few changes in the locations initially selected. The school established at the University of Florida was not well attended so it was decided in August 1942 to transfer its staff and faculty to southern California where insistent demand for this training had developed. Thus a school at Occidental College, Los Angeles, opened on 1 September 1942 and continued in successful operation until the training program was terminated. Another adjustment made in November 1942 was the transfer of the Texas A. & M. school to Loyola University, New Orleans. The University of Maryland school was closed in September 1942, primarily in order to provide personnel for another training activity.

Each of these facilities, designated as War Department Civilian Protection Schools, was organized under a common pattern which followed experience gained at Edgewood Arsenal. A staff of six officer-instructors and an enlisted detachment of twenty-five men plus several clerical assistants were provided for each school, the senior officer in each instance being designated as school director. Cost of housing and meals, usually supplied by the university, was borne by the individual student. Outdoor instructional areas, including stage setting for a night incendiary demonstration, were set up by military personnel. Under their contract with the War Department, universities where schools were located were reimbursed only for actual expenses incurred. This sum scarcely compensated the institutions for extensive use made of their facilities, the value of which had to be written off as a contribution to the national defense.

With the opening of the first branch schools in February 1942 the original twelve-day course developed at the Chemical Warfare School was shortened to nine days (sixty-six hours) of scheduled instruction. This change was occasioned in part by the fact that certain instruction given at Edgewood Arsenal could not be duplicated elsewhere. By streamlining the course and eliminating interesting but nonessential periods it was found that a satisfactory program of basic training in civilian defense could be completed by the end of the second Wednesday.

As finally organized, the general Civilian Defense Course included nine subcourses as follows:

Aerial Attack (7 hours) : To acquaint the student with the general features of aerial action, including hostile operations and military countermeasures thereto—thus leading to a clearer conception of the factors in modern war which necessitate development of civilian protection.

Civilian Defense Organization (3 hours) : To insure familiarity with the general outlines of organization on national, regional, state, and local

levels by which civilian defense is integrated to meet the problems presented by aerial attack.

Bomb Disposal (4½ hours) : Presenting characteristics of explosive bombs and the general problem of disposing of unexploded bombs; definition of respective responsibilities of civilian agencies and military agencies in handling unexploded bomb situations.27

Incendiary Protection (9 hours) : To impart understanding of the essential features of incendiary munitions, and of means and methods by which they can be controlled without recourse to organized fire-fighting units.

Gas Protection (11 hours): Consideration of the nature and characteristics of gases that may be employed against civilian targets; methods of protection against them; civilian organization of gas defense.

Plant Protection (5 hours): Problems of organization and technical preparation of industrial plants, hospitals, and other large facilities as distinct from community protection.

Citizens Defense Corps (17½ hours): To induce appreciation of the corps as an integrated team capable of coping with the various types of incidents, through review of functions of each unit and through exercises involving their combined employment under the control center.

Local Training (3½ hours) : To prepare students to actively and effectively participate in local programs of civilian defense training.

General Subjects (5½ hours): Miscellaneous exercises and conferences not otherwise included.

By instructional directives, each of these subcourses was broken down into a suitable number of lectures, conferences, demonstrations, and exercises to insure the most effective approach to the designated objective. An instructor’s period guide was provided by the Civilian Protection Branch, OC CWS, for each lesson phase. A standardized schedule indicated the sequence of instruction to be followed, text references, and academic procedure. Although each school director was authorized to make modifications to meet local conditions or to emphasize local problems, such variations were incidental. The school authorities realized that only within a firm overall pattern was it possible to reflect instructionally the frequent changes being made in the technique of protection against air attack.

Teaching procedure at the schools was based on FM 21-5 , Military Training, and TM 21-250, Army Instruction. The texts employed were publications of the U.S. Office of Civilian Defense, supplemented

occasionally by military manuals. Pertinent OCD publications were usually supplied in sufficient quantities to provide one for each student to be used at school and retained after graduation. Much of the resident instruction was explanation, demonstration, and application of matter contained in these texts. The atmosphere of the schools reflected the precision and thoroughness associated with the military service. Behind the immediate purpose of quickly imparting needed knowledge was the implicit responsibility of imbuing each graduate with a sense of confidence in the armed forces of the United States.28

The immediate and continued success of those schools was due in large measure to the experience and capability of the instructors who were assigned to these faculties. These Reserve officers were in many instances professional college and university teachers who fitted readily into this new type of semimilitary training conducted in an academic environment.

A reorganization of the teaching program of War Department Civilian Protection Schools was undertaken in December 1942. By this time civilian defense organization at local levels had been completed, the Citizens’ Defense Corps was well established, and there was diminished need for the general course as originally developed at the Chemical Warfare School. However, definite requirement was now felt for more specialized instruction than was possible in the standardized course. A group of four shorter courses was accordingly worked out by the Civilian Protection Branch, OC CWS, including:

Basic Protection Course (6 days) : Thorough grounding in technique applicable to community protection—handling of incendiaries, unexploded bombs, and gas situations; air raid wardens duties; blackouts; panic prevention; training the general public; and similar basic problems with which all were concerned.

Plant Protection Course (6 days) : To specialize in training of selected plant personnel in problems of organization and technical preparation of industrial plants, hospitals, and other large institutions or facilities as distinct from community protection. This course was generally similar to the basic course except that the point of view was .that of the plant or institution rather than the municipality.

Staff Course (5 days) : Embraced command organization for control of combined units in air raid action; strategy of civilian protection; integration of military and civilian security agencies; planning and execution of local

programs; organization and direction of the Citizens’ Defense Corps; control center exercises.

Gas Specialists Course (5 days) : To qualify senior (local) gas officers and gas reconnaissance agents for performance of their duties; instruction of the general public, and equipment and training of Citizens’ Defense Corps enrollees.

With the concurrence of the OCD, these shorter courses replaced the original basic course after 1942. During the first six months of 1943 approximately twenty of them were conducted at each WDCP school, scheduled in accordance with the training requirements of regional OCD authorities.

Miscellaneous Activities

Each WDCP school was called upon for considerable service over and above the resident instruction of civilian students. At colleges where these schools were located, the college laboratories served as practical substitutes for chemical field laboratories. The prospect of Japan delivering at least a token gas attack against the United States was by no means fantastic; should such attack be made, it was important to identify accurately the agents used.29 For this reason, qualified instructors in analytical chemistry on the faculties of these colleges were given special instruction at Edgewood Arsenal in detection of war gases and arrangements were made with service commands to have samples of any enemy chemical agents dropped within the zone of the interior dispatched to the nearest school for analysis and positive identification.

The number of Negroes trained at WDCP schools was relatively small. This no doubt was due to the limited employment of Negroes as instructors and as executives in local civilian defense organizations. Three classes of all-Negro students were conducted in the fall of 1942 at the Prairie View (Texas) Normal and Industrial College by the faculty of the Texas A. & M. school. One hundred and fifty-one men and women from several southern states were trained in these classes. The instructional staff was altogether satisfied with the caliber of these students and would have welcomed the opportunity to train additional Negroes had they been needed.

An important feature of extracurricular work of the schools was conducting plant protection seminars. These were held in every section of the country, an outgrowth of the work originally undertaken in this field by the Chemical Warfare School in the autumn of 1941. Word of such exercises held in the Southwest was carried home by Mexican graduates of the Texas school and led the Mexican Government formally to write the Americans to stage a plant protection exercise at Monterrey, Nuevo Leon. This exercise was successfully accomplished in September 1942 and occasioned a request from the Republic of Mexico for a more elaborate civilian defense program to be conducted in Mexico City.30 The project was arranged through the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. With concurrence of the State Department, a party headed by the U.S. Director of Civilian Defense (James M. Landis) and including experienced CWS instructors flew to the Mexican capital in May 1943 for a three-day series of conferences to acquaint local and national authorities with U.S. civil defense procedures.

The most spectacular training activity of CWS in World War II was an outgrowth of the biweekly incendiary demonstration conducted by the University of Maryland WDCP school. This exercise constantly attracted large groups of spectators from Washington, military as well as civilian, a fact which influenced the school director, Col. Joseph D. Sears, to develop the demonstration into an outstanding spectacle. After observing the popular interest thus awakened and appreciating the desirability of carrying to a larger audience the lessons taught in the exercise, the OCD requested the War Department to make this a traveling unit. The War Department was unwilling to increase the personnel then allotted to civilian defense training but countered with the proposal that the Maryland school be closed and its staff utilized for this purpose. Under this arrangement a mobile unit named ACTION OVERHEAD was organized.

This undertaking put the CWS squarely into the show business. It required building up a staff with theatrical experience, including stage managers, lighting and sound effects men, and narrators. Personnel of the unit included nine officers and thirty-five enlisted men, more than the normal WDCP school complement, yet certainly small for the task at hand. The 15,000-word script followed in the show was developed principally by Colonel Sears and was finally approved by the Office of the Chief, CWS, and OCD on 31 August 1942, by which time ACTION OVERHEAD, in a caravan of fourteen trucks, was ready for the road.

Throughout the performance the Army’s instructional sequence of explanation, demonstration, and application was steadily followed. The hour and a half demonstration was divided into two sections. In the first section the various types of bombs used in air attack were displayed, explained, and detonated. Then followed demonstrations of correct methods of counteraction, usually undertaken by local units of the Citizens’ Defense Corps. Stressed throughout this part of the exercises were practical knowledge, foresight, and calmness in the face of air attack. The second section opened with display of a typical control center, manned insofar as possible by local civilian defense volunteers. After explanation of the setup and operation of the control center, the demonstration field was blacked out for a simulated air attack. When possible, a flight of planes from a nearby Army Air Force base was employed, the dropping of live bombs being represented by static detonation of high explosives and incendiaries. In cities where the AAF was unable to cooperate in providing aircraft, sound strips were used to simulate their approach.

During 1942 and 1943 ACTION OVERHEAD was presented before 21/4 million people in more than one hundred American cities, giving a realistic interpretation of air attack and of civilian defense in action.

Supervision of War Department Civilian Protection Schools

Prior to the reorganization of the War Department in March 1942, civilian defense matters were handled by the Civil Defense Branch, Office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3. After the creation of the Services of Supply, these functions were transferred to the Civil Defense Section of the Office of Chief of Administrative Services (SOS).31 The latter organization thereafter coordinated all War Department activities in this field, including conduct of schools. Since the training was essentially technical in nature, its supervision was left with the CWS—the principal concern of the Services of Supply being that the schools met the requirements of OCD and that they were efficiently conducted.

Close liaison had to be maintained between the Office of the Chief, CWS, and the Office of Civilian Defense in training and related activities. The general operating procedure was for the OCD to indicate what teaching was desirable, the War Department then determining how the instructional aim would be attained. Army relations with the OCD were handled through the

Board of Civilian Protection. The OCD Training Division was an important agency of the Board of Civilian Protection and its activities were directed by the Army member of that board. In addition to continuous development of the curriculum, which was a joint CWS-OCD project, the Training Division was solely responsible for the allotting to regional directors of quotas for civilian students.

At the end of a year of wartime operation, the OCD formally requested that the WDCP schools be continued. In approving this proposal, the U.S. Director of Civilian Defense was advised:

The War Department is agreeable to the continuation of these schools during the calendar year 1943, provided it is your judgment they are serving an essential purpose.

The Chief, Chemical Warfare Service, has been informed accordingly, and he is being directed to continue, as long as these schools are conducted by the War Department, to operate them in such a manner as will most effectively aid you in meeting the important responsibilities of your office.32

The question of how far these schools were “serving an essential purpose” began to present itself in the spring of 1943. For understandable reasons the active concern of the War Department with the civilian defense program gradually lessened as the war progressed. In the course of two years the Office of Civilian Defense, starting from scratch, had developed a nationwide scheme of civilian self-protection against air raids that was reasonably adequate, so that need for advanced training in this field was beginning to lack urgency. The doubt and unrest that arose after the shocking events of December 1941 had been supplanted by a sense of national confidence inspired by victories that began with the Battle of Midway. The gradual build-up of United Nations strength finally forced the Axis powers to assume the strategic defensive, which left them impotent to undertake serious action against the U.S. mainland. At the same time shortages of manpower at home obliged the Army by 1943 to curtail every activity that did not contribute directly to military victory overseas.

Early in 1943 the prospects of enemy attack were reviewed by the Combined Chemical Warfare Committee for study of the Policy for Gas Defense of the U.S. A study prepared by this group on 20 May 1943 reported the following conclusions:

(1) At present the enemy does not possess the means to deliver sustained gas attacks against the United States.

(2) The enemy probably does possess the means to deliver surprise and sporadic gas attacks against vital coastal installations in the United States.

(3) The enemy is not now capable of delivering any attacks against inland installations.

(4) Ample warning will be given before the enemy can get into a position which will enable him to deliver regular and sustained gas attacks against the United States.33

Although this report was made primarily with a view to determining policy as to protection of military installations in the zone of interior, its application to civilian defense was clear. The hazard of enemy gas attack against American cities had diminished to the point of negligibility.

Nor was this situation the result solely of the deterioration of enemy capabilities. U.S. defensive measures had progressively advanced until they promised to deny important advantage to the attacker. The American public had become acquainted with the characteristics of air raids and had developed more confidence in its ability to withstand their effects. The likelihood of creating panic in heavily populated areas by a show of air power had greatly diminished.

The gas protection phase of the civilian defense program, developed under CWS guidance, took into account certain psychological or morale-sustaining ends as well as the physical protection of the individual. It involved protective matériel plus organization, with the two blended into a functional entity. Civilian gas masks had been procured by the CWS and were stored by the OCD in quantities sufficient to permit issuance of one to every civilian whose duty required him to remain in a gassed area.34 The civilian gas protection organization insured echelonment of responsibility and technical competence where this was needed. It provided for the execution of antigas measures by civilians themselves under procedures authenticated by military experience and training. Although fortunately the defensive scheme was never subjected to the test of combat, it did provide ground for assurance that the threat of poison gas could be countered successfully.

What had been accomplished in the field of gas defense was paralleled in other fields of air raid protection. Large industrial plants had developed operational procedures which promised to avert serious disruption of production in consequence of aerial attack. Fire-fighting organizations had become acquainted with the characteristics of incendiary bombing, against which defensive measures were introduced. State and municipal plans for evacuation,

rescue, medical assistance, and other aspects of passive defense were developed. The ability of U.S. citizens to withstand assault by air was increasing rapidly at the same time that enemy capability of initiating such assault was on the wane. This fact, recognized by Congress as well as by the general public, resulted in decision to terminate the WDCP school program. The schools accordingly were discontinued effective 21 July 1943.35

During their operation a total of 274 classes were conducted with an average attendance of 37.7 trainees. Graduates included men and women from every state in the Union as well as from Canada and Mexico. Over one fifth of the 10,328 enrolled students were Army and Navy officers, some of whom were trained for civilian protection duty in the zone of interior, others in the theaters of operation.

Although it now appears that the operation of WDCP schools after midsummer of 1943 was not justified, the War Department willingly agreed to continue aid to OCD in its training operations by providing CWS instructors as needed for technical training in state civilian defense schools.36 It further agreed to maintain two educational facilities, one on each coast, where Army training of civilians could be undertaken again if occasion demanded. This commitment lead to the activation of the West Coast Chemical Warfare School at Camp Beale, California, in the fall of 1943, while plans were made for resuming civilian training at the CW School if necessary. However, OCD training activities virtually ceased with the closing of WDCP schools.

At the same time that it was diminishing within the zone of interior, the need for training in air raid precaution was being emphasized abroad as the extent Of occupied territory increased. Civilian protection in occupied areas was a function of Military Government, although few officers designated for such duty had received any training in this specialty. The Chemical Warfare School was directed in September 1943 to prepare an air raid protection course to qualify CWS personnel to function as staff air raid protection officers in each theater of operations and for the training of officers of other branches for this type of duty within their units.37 Well-qualified instructors released by the closing of WDCP schools were available for this purpose. A series of seven 1-week classes, each averaging 43 students, was completed at the Chemical Warfare School by the end of 1943. This brought to a close an interesting if somewhat unusual CWS training activity.