Chapter 2: The CWS in the European Theater

Planning and Organization: 1940–43

Erecting the Framework for an Overseas Command

CWS officers in the United States followed the initiation of World War II in Europe with keen interest as a chance to test predictions that gas would become a major weapon of the war. There was no indication that gas was used in Hitler’s attack on Poland, but the British Government had begun issuing gas masks to military and civilians alike even before the declaration of war. Lt. Col. Charles E. Loucks, CWS, in June 1940 arrived in France to fill the position of assistant military attaché in the American Embassy and to serve as CWS observer. With the fall of France shortly thereafter, Loucks was transferred to England in the same capacity. The most interesting development early in the European war from the CWS point of view was the German incendiary bombing of England. Loucks reported extensively on bomb types and effects of bombing.1

Loucks did not become a member of the American Special Observer Group (SPOBS) , which was organized in England prior to the United States entry into the war, but in February 1942 his successor as military attaché, Col. Carl L. Marriott, was also designated Chemical Officer, United States Army Forces in the British Isles (USAFBI) , the first official American command in Europe, in fact a redesignation of SPOBS.2 Marriott thus assumed the duties of reporting, still principally

reporting on incendiary bombings, and he began to oversee the chemical warfare protection and training of American troops. Lt. Col. Lewis F. Acker established a chemical section in the headquarters of U.S. Army V Corps, the first U.S. ground forces organization to arrive in the British Isles.3

On 2 May 1942 Colonel Marriott was forced by ill health to return to the United States, and Col. Charles S. Shadle assumed the dual role. By the time of Shadle’s appointment, the duties of Chemical Officer, USAFBI, were demanding full time: there was not only the necessity of seeing to the equipment and training of increasing numbers of American troops but also the requirement for participating in and initiating administrative, supply, and operational planning for what was clearly to become a major overseas command. At that time, a little more than a month before the President’s first pronouncement on gas warfare, neither national nor international policy on gas warfare was clear. CWS officers always assumed, in absence of definite information to the contrary, that their first duty was to make as many defensive and offensive gas warfare preparations as possible. In June Col. J. Enrique Zanetti, CWS incendiary expert and World War I liaison officer on Fries’s staff, arrived to relieve Shadle of the attaché position.4 Also in June Col. Crawford M. Kellogg, six officers, and nine enlisted men of the Chemical Section, Eighth Air Force, arrived in England. The Eighth Air Force Chemical Section had been activated along with the Eighth Air Force headquarters at Bolling Field in April.5

While the chemical sections in the British Isles were organizing and embarking on their planning and supply duties, other organizational developments were taking place in the United States. The President and his military advisers in consultation with the British had decided to establish a theater of operations headquarters in England. A manual describing theater headquarters organization existed, but the manual had been written before the War Department reorganization into three commands with the attendant revision of organizational policy. Furthermore, United Nations strategists had not yet decided upon launching a ground offensive, so that the first mission of the American

theater headquarters would be cooperation with the British and supervision of a matériel build-up in anticipation of a combined assault upon the European continent at some future date. The second mission would be the support of Eighth Air Force operations and the support of ground and service troop training and equipment. Emphasis upon logistics organization was clearly indicated. The War Department tricommand organization was not prescribed for a theater in the regulations which antedated this organization, but neither was it proscribed. General Marshall set about organizing a tripartite theater command, and, since the air element in the form of Eighth Air Force already existed and the ground element would not be important for the time being, he concentrated on that service element. Generals Marshall and Somervell picked Maj. Gen. John C. H. Lee to be the European theater SOS commander. They oversaw the organization of Lee’s headquarters in the United States, and they instructed Lee on Marshall’s desires concerning theater organization.6

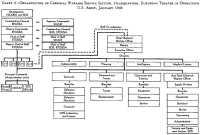

Marshall’s, Somervell’s, and Lee’s organization and organizational concepts proved important to the CWS. The manual provided that a theater chief chemical officer would restrict himself and his immediate staff to the formulation of broad policy. He would operate his service through technical control of subordinates. Subordinates for combat matters, as in the CWS AEF, were to be army, corps, and division chemical officers. Subordinates for service and supply matters were to be on the staffs of the communications zone, regulating station, and advance, intermediate, and base section commanders.7 (Chart 3) With such decentralization of operations, the immediate office of the theater chief chemical officer was to have only one operating division for research, development, and intelligence and a small staff. General Fries, working under a highly centralized policy, had needed a large staff and six operating divisions. The problem in the case of the European theater organization was that neither the World War I type of organization nor the manual organization seemed to apply.

General Somervell’s ASF instructed the chiefs of the services in the United States to provide top-quality officers to join Lee’s staff before it

Chart 3: Planned Distribution of Staff and Service Agencies, Chemical Warfare Service, Theater of Operations

Source: Adapted from: FM 3-15, 17 Feb 41 and C2, 6 May 43.

left to go overseas. General Porter, under the assumption that he was appointing a theater chief chemical officer, chose Col. Edward Montgomery, one of the four Regular Army colonels in the appropriate age group within the CWS, to head the group. Montgomery’s deputy, Col. Lowell A. Elliott, and three of his division chiefs, Cols. Hugh W. Rowan, John C. MacArthur, and Edwin C. Maling, were top-ranking Regular Army lieutenant colonels then recently promoted to temporary colonel. These officers, several junior officers, and a number of enlisted men joined Lee’s headquarters at Indiantown Gap Military Reservation to await transportation to England.8

General Lee and a small advance echelon of his headquarters arrived in London on 24 May 1942 and immediately set to work activating the SOS USAFBI. Lee just as immediately ran into a storm. The USAFBI staff was adamantly opposed to Lee’s planned subordination of the theater service chiefs to the SOS commander since that subordination implied exactly what the War Department intended—SOS control of theater service and supply policy. After much discussion and reviewing of directives, the first of many compromises on theater organization was reached in June closely following the redesignation of USAFBI as the European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) . In this compromise the chemical warfare and ten other theater special staff sections were given over to the control of Lee’s SOS while retaining their titles as theater special staff sections. Colonel Montgomery, who arrived in June, was designated chief chemical warfare officer and a member of the theater special staff. The SOS headquarters and the offices of the theater service chiefs were moved from London ninety miles to Cheltenham. The theater headquarters, now commanded by Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, remained in London. Shadle was named CWS representative at Headquarters, ETOUSA, and given two officer assistants. Shadle’s position, reminiscent of the position of CWS AEF representative at GHQ, was established in accordance with the basic theater organizational directive which provided for a service representative when the theater chief of service was not located at theater headquarters.9

Still, from the CWS point of view, the situation was not a happy one. If Montgomery was to be represented in, rather than resident in, theater

headquarters, the CWS preparedness and advisory mission could only be properly performed if he had a large, strong operational staff such as Fries had had at Tours. The prospects of getting such a staff at Cheltenham were dim since Cheltenham was intended to be a service and supply headquarters only. Montgomery consequently spent much of his time in the London echelon of SOS while Elliott proceeded to Cheltenham in the dual role of deputy and temporary chief of the Supply Division. In Cheltenham, Capt. Warren S. LeRoy, Acting Chief, Storage and Issue Section, Supply Division, at once resumed work on storage and issue procedures for chemical supplies which he and the OCCWS (Office of the Chief, Chemical Warfare Service) staff had begun in the United States. Maj. Maurice H. Wright activated the Procurement Section, Supply Division, while Maj. John J. Hayes set up a Requirements Division. Rowan and MacArthur reported to Cheltenham early in July. Rowan set up the Technical Division while MacArthur established the Operations and Training Division, but for several weeks both officers were confined to planning and background work since their activities were inappropriate to the work of the Cheltenham command and since they had no assistants and very little equipment.10

By the end of July Montgomery was able to bring about some improvement in the maladjusted organizational distribution. He secured the transfer of Rowan’s Technical Division and Wright’s Procurement Section to the London echelon of SOS. The Technical Division was charged with liaison concerning all technical matters both with the British and with headquarters other than the SOS, and Wright was given the additional duty of liaison with the British on lend-lease matters. In both cases, location in Cheltenham would have greatly complicated communications and the discharge of normal functions.11 Rowan set up his London office at the end of the first week in August with two officer assistants. Wright was allotted one assistant. Approximately two weeks later Shadle was designated Chief Chemical Officer, Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) , a position at least in theory superior to that of theater chemical officer. AFHQ, a combined supreme headquarters, was preparing for the North African invasion.

MacArthur moved in as his replacement and took over supervision of the chemical warfare exercises for which planning, in coordination with British chemical warfare authorities, was virtually complete. Since MacArthur was Montgomery’s planning officer and his training policy chief, MacArthur’s move to London completed the physical transfer of all chemical warfare policy, technical, advisory, and liaison functions to theater headquarters while organizationally all but MacArthur remained in the SOS.12

Also in August 1942 the operating elements of the CWS began to sort themselves out. Col. Leonard M. Johnson arrived in Cheltenham to become Chief, Supply Division. Although few CWS supplies were arriving in England, the Supply Division was already working on storage and distribution measures. At about the same time, Colonel Maling, his four officers and five enlisted men, began the establishment of the CWS training operations within the newly authorized American School Center at Shrivenham. The CWS had hoped and planned to establish its own school but had been obliged to participate in the centralization of theater training activities. Centralization did offer advantages of better facilities and equipment and better handling of admissions than a single service could manage.13 Kellogg, meanwhile, had distributed his ten Eighth Air Force chemical officers among three chemical sections—one, to control supply and training branches in the Eighth Air Force headquarters, another, to direct supply operations in the VIII Air Force Service Command (AFSC) , and a third, to supervise ground service and training in the VIII Bomber Command. While these sections were in the process of organization, Kellogg and his staff worked on a revision of the war gas supply plan which had been formulated by his section in the United States. Since, even in this early period, both the War Department and the forces in the theater had accepted the policy that any gas warfare retaliatory or offensive effort would be the operating responsibility of the air forces, the Eighth Air Force toxic supply plan was crucial to the gas warfare potential of the CWS ET0.14 It then appeared that the CWS ETO pattern was set, and the pattern followed neither the World War I precedent nor the prescriptions of regulations. Whether the CWS ETO could accomplish its

mission through the use of this pattern remained to be seen. The first test soon came when England became a base for the North African invasion (TORCH operation) for which the European theater provided logistical support. Largely as a result of providing officers and men for TORCH, CWS ETO experienced sweeping staff changes.

Colonel Montgomery was recalled to the United States for special duty in September 1942. Elliott was appointed to establish a chemical section for the forming Twelfth Air Force headquarters, destined for North Africa, and Maling was attached to the AFHQ planning staff in a nonchemical capacity. One lieutenant colonel, six majors, and three captains from the London and Cheltenham CWS elements soon joined the North African forces. Kellogg was the senior CWS officer remaining with European theater forces, but Rowan, senior CWS officer in the SOS, succeeded Montgomery in acting capacity.15 Elliott’s duties as deputy were divided between Johnson in Cheltenham and MacArthur in London. Maling’s post at Shrivenham went to a succession of junior officers.16

By mid-September TORCH was not only creating a constant drain on manpower, but it was also demanding materiel, support for operational planning, and readiness inspection. At the same time, the base sections, local supply and service organizations, were organizing in the United Kingdom,, and supply and service installations were being activated as rapidly as possible. Furthermore, although the materiel and troop build-up in England had been brought virtually to a standstill in deference to the North African venture, operational and informational demands in the theater were growing apace. Theater officers regarded the strategic hiatus with respect to ETOUSA as only temporary, and they continued to believe that the prime task in the United Kingdom was to prepare for eventual assault on the Continent. To meet an important CWS need for intelligence information, the CWS arranged for Colonel Zanetti, assistant military attaché, to become in effect chief of an intelligence division. Capt. Philip R. Tarr and two other officers were transferred from Cheltenham to London on 19 September 1942 to assist Zanetti. One of Maling’s successors at the American School

Center and a Supply Division section chief moved out to establish chemical sections in two newly activated base sections. Maj. Frederick E. Powell, another section chief, and seven company-grade officers went from Supply Division to establish chemical sections in general depots and chemical branch depots. Since three other Supply Division section chiefs had gone to the TORCH forces, newly arrived lieutenants filled most supply division staff positions.17

First Reorganization

On 9 November 1942 the War Department notified the theater headquarters that Colonel Montgomery, who had been appointed chemical officer in the War Department Air Forces Headquarters, would not be returning to the European theater. The theater commander appointed Colonel Rowan chief chemical warfare officer and assigned him to theater headquarters in London. Thus, Rowan officially became resident at theater headquarters and the position of CWS representative was automatically abolished. Rowan appointed MacArthur his deputy and executive officer.18 While General Porter had not had a hand in Rowan’s appointment, he was well satisfied with it.19 Rowan’s qualifications were good. At 48, he was a year younger than the average age of the ETO technical services chiefs. He held the same permanent rank, lieutenant colonel, as all but one of his peers. At the time of his appointment he held the same temporary rank as three of the service chiefs—the four others having attained general officer rank. Like most other senior CWS officers, Rowan had World War I experience, as assistant gas officer and gas officer of the division in which General Lee had been chief of staff. He was a chemist, a graduate of Yale University, the Chemical Warfare School, and the Army Industrial College. Early in his Army career, Rowan had been marked as an expert on industrial mobilization in the chemical field, and he had served several tours, including one in the Office of the Assistant Secretary of War, in positions relating to that specialty. He had also had assignments in war planning, in chemical technical work, and in troop training, and

he had served a 4-year tour as assistant military attaché in Berlin at the beginning of the Nazi period.20

A week after Rowan’s appointment ETOUSA clarified and regularized the status of the theater CWS. ETOUSA assigned specific duties and functions to the CWS office at Cheltenham under the control of SOS. These included supervision of all CWS supply activities across the board from requirements, purchasing, and manufacture through storage and issue and maintenance and repair to transportation and shipping as well as supervision of CW training for SOS troops, and CWS administration within SOS.21 The specification of duties at Cheltenham and the additional provision that he could transfer personnel needed in his theater headquarters office to provide planning, policy, training, technical, and intelligence services from Cheltenham or the London SOS offices, left Rowan free to organize his office as the situated dictated. On 18 November he submitted his proposals to G-3, ETOUSA, and on 23 November published the approved pattern in Office of the Chief Chemical Warfare Officer, ETOUSA, Office Order No. 1. MacArthur officially resumed the post of Chief, Operations and Training Division, which in fact he had never left, in addition to his duties as executive officer and deputy. Lt. Col. Walter M. Scott’s position as Chief, Technical Division, was affirmed, and he was given supervision of a liaison officer who had been stationed at the British chemical warfare experimental center at Porton. Rowan named Maj. Roy LeCraw to head a new Administrative Division. Captain Tarr, officer, and 2 civilian clerks were to form an Intelligence Section, primarily an office of record since Colonel Zanetti continued to handle intelligence, within the Administrative Division. The total complement of Rowan’s theater headquarters office, besides himself, was 12 officers, 5 enlisted men, and 5 civilians.22

The November 1942 reorganization of the CWS ETOUSA produced an organization similar to the one suggested in the manual for the office of a theater chemical officer. The situation of the CWS and the theater itself was not a “book” situation. The theater was active logistically but its strategic destination was more in doubt than it had

been before the North African invasion. The lines of the theater commands were not clear and no chief of service could be positive about the precise character and scope of his service’s mission. In Rowan’s case, one element of his office, his Supply Division, was located ninety miles away from him under the jurisdiction of a command which might be considered an SOS field organization. A “book” solution to these problems of communications, relationships, and supervision within the CWS ETO would have been to designate the Supply Division as a communications zone chemical section, but when the SOS command at Cheltenham decided upon this action it served only to further confuse the issue of mission and supervision. Neither Rowan’s London office nor the Cheltenham branch was prepared to operate as a separate entity under the prevailing theater pattern.

On 18 October 1942 when Supply Division absorbed Requirements Division, Colonel Johnson supervised eleven CWS officers and twenty-two enlisted men in Cheltenham. He also supervised the procurement and reverse lend-lease activities of Major Wright and his assistant in London. Support of the North African operation and activation of a logistics system in the United Kingdom kept this staff fully occupied.23 After the reorganization of Rowan’s London office and just before Johnson’s transfer to the North African forces, the Cheltenham SOS headquarters designated Johnson as Montgomery’s successor as Chief Chemical Warfare Officer, SOS, and renamed the CWS Supply Division as the SOS Chemical Warfare Section.24 Johnson took the position that the SOS order was meaningless. Rowan was clearly Montgomery’s successor, and he considered himself as Rowan’s assistant. He furthermore lacked the staff and the authority in the field to establish a communications zone (SOS) chemical section. While his office had the operating functions of determining matériel requirements, preparing requisitions on the United States, and directing distribution of chemical supplies within the theater, its functions were more nearly those of a supply policy division in the office of a theater chief chemical officer than they were the functions of a theater supply and distribution command chemical section. Also, if Johnson had attempted to establish a communications zone chemical section, he would have deprived Rowan of the direct control of chemical supply

since Rowan had no supply policy element in his London office.25 The only outcome of the SOS order was the establishment of the largely inactive Cheltenham element of the CWS Operations and Training Division as the Training Branch, Supply Division. A lieutenant was assigned to head the Training Branch and he was allotted one part-time adviser and one part-time assistant. The branch was assigned the function of supervising chemical training within SOS ETOUSA.26

Major LeRoy, who succeeded to the position of SOS chemical warfare officer when Johnson was designated Chemical Officer, Mediterranean Base Section, North African Theater of Operations (NATO) , in December, made no change in policy. Indeed, LeRoy experienced enough difficulty in staffing Supply Division without trying to extend the scope of his activities. He was the only field-grade CWS officer left in Cheltenham, and he had no captains on his immediate staff of fourteen officers. His executive officer, Lt. Arthur T. Hingle, also served as Chief, Statistical Section. Lt. Ingalls S. Bradley headed both the Operations and Service Sections while another lieutenant was Chief, Processing Section, and assistant in the Service Section. LeRoy did not staff prescribed subsections for salvage, maintenance, impregnating, and filling plants in order to concentrate manpower in the requirements, control, transportation, and issue areas.27 Such concentration of effort was demanded in order to meet the needs of the North African forces, but late in 1942 and early in 1943 when chemical supply requirements for North Africa were increasingly met by direct shipment from the United States, the need for concentration in the same areas did not lessen because now the task of top priority was preparing the European theater for gas warfare. The first question raised in connection with theater gas warfare preparedness was that of the requirement for chemical offensive and defensive materials and service troops. Once requirements had been estimated, it was necessary to plan storage and distribution within the theater.

Gas Warfare Planning

Rowan’s staff had completed most of the basic work on a comprehensive gas warfare plan for the European theater before the War Department letter requiring such a plan was received.28 Kellogg and his staff had prepared air force supply and storage estimates for the offensive portion of the plan. Late in 1942 LeRoy took a draft of the ETO plan to Washington where he discussed it in detail with General Porter’s staff and exchanged information on theater and stateside preparations. Later OCCWS referred the draft plan to the chemical liaison officer on the OPD staff.29 But since the ETO plan was predicated on the vast expansion of the theater for a continental invasion, as yet uncertain, it could only be brought to an indefinite conclusion.

Policy and strategy were in the making. The Allied leaders decided at the January Casablanca Conference to revive the build-up in the United Kingdom and took a number of actions during 1943 to flesh out that decision.30 In November 1942 the Combined Chiefs of Staff had briefly turned their attention to gas warfare and now an Allied as well as a United States policy was emerging. This policy required: () a cooperative American and British effort aimed at arranging the defensive preparedness of all United Nations troops; and (2) the accumulation of sufficient toxic munitions to make immediate retaliation possible should the enemy initiate gas warfare anywhere in the world.31

The Second Reorganization

In connection with the determination of Allied policy on chemical warfare and in order to evaluate the status of chemical warfare preparedness among American troops, General Porter and Brig. Gen. Charles E. Loucks of his staff journeyed to England in March of 1943, and from there went on to North Africa. Loucks, writing his own

General Porter and top-ranking chemical officers in London, 1943. (Left to right) General Porter, General Loucks, Colonel Kellogg, Colonel Rowan, Colonel MacArthur, and Colonel Zanetti.

and Porter’s impressions, advised OCCWS on several European theater problems and developments. The two officers found that the ETO had enough supplies for the force then in the theater, but they considered some of the items from the United States poor in quality.32 The theater organization situation, they believed, was unsatisfactory. It appeared to them that “the Commanding General, Army Service Forces in Great Britain [sic] is entirely independent of the Commanding General, European Theater of Operations. The latter is dependent on the former for the supply but does not function as his superior.”33 Officially the theater commander, now Lt. Gen. Frank M. Andrews, certainly functioned as General Lee’s superior, but Loucks’s words were probably intended to describe the de facto rather than the de jure

situation with respect to the CWS. The import of these remarks was that Rowan, despite his official status as theater chief chemical warfare officer, could in fact work only through Lee under whose jurisdiction his office fell. Consequently, he had no direct channel of communication and authority through which he might, in the words of the manual, exercise “general technical supervision over his service as a whole.”34 Such supervision was vital. Although the European theater was active at the time only in the air war, the greatest threat of gas warfare initiation was posed by the known German industrial chemical potential. The heavy concentration of American and British strength in the United Kingdom and the proposed build-up of men and materials there presented to the Germans excellent targets for vesicant gases. Germany was unlikely to launch a gas attack on the United Kingdom since she had not done so in the great blitz bombings of 1940–41 and since she would fear retaliation. But no chances should be taken, from the CWS point of view, by failing to build up a retaliatory potential. Developing such a potential, laying the defensive and offensive plans, and coordinating CWS operations in the theater demanded that Rowan have some direct channel through which to operate.

Porter’s solution for the organizational impasse was to suggest that “the officer occupying the position of chemical officer for the theater commander” take the initiative in securing the cooperation and coordination of all the principal chemical officers in the theater. In other words, he proposed using the informal channels of personal and technical correspondence and communication among officers of the same service, known as technical channels, in place of formal command channels. Porter further suggested that he would personally elicit such cooperation. It is interesting to note that Loucks did not refer to the theater chief chemical warfare officer nor to the chief of service. In a listing of personnel, he cited Rowan as “Chemical Officer, Army Service Forces” and “for the present ... also the staff chemical officer for the European Theater of Operations.”35

Clearly, while Porter and Loucks accepted Rowan as theater chief chemical officer, they were not prepared to acknowledge that there was a theater chief of the CWS. Rowan was, as he had been from the previous November, Chief Chemical Warfare Officer, ETOUSA. In

the same month of Porter’s visit, the theater commander ordered SOS headquarters back from Cheltenham. He relocated the service chiefs in SOS.36 The fiction of a separate chemical section in Cheltenham was thereby dropped, and Rowan officially became Chemical Officer, SOS ETOUSA. Neither of these positions fitted the manual definition of the chief of service nor did they compare to the positions which Fries had held. Rowan, accepting Porter’s advice, decided to make his position as theater chief chemical officer equivalent to that of chief salesman for such services and supplies as the CWS could contribute to the war effort in the theater. He found it necessary to employ his own prestige and ability to persuade commanders that it was in their best interest to be prepared against gas warfare, and to use smoke, flame, and chemical mortars. Porter was right in his observation that Rowan did not have the usual channels of a theater staff officer; Rowan could seldom speak with the authority of the theater commander as Fries had done.37 Indeed, he could sometimes not speak with the authority of his other and more immediate commander, General Lee. Lee, for example did not authorize his chiefs of service to operate within his field commands, the base sections, chiefly because base section commanders complained that the service chiefs interfered in their command procedures.38 The service chiefs did most of their volume business, supply, through the base sections and were therefore required to control a part of the operation. Rowan solved this problem by using technical channels to base section chemical officers and by frequently meeting with these officers to resolve CWS difficulties.39

The looseness of control within the theater organization and within the SOS which created so many problems for the technical services and particularly for the CWS was by no means peculiar to the European theater. Under the principle of “unity of command” General Marshall advocated placing theater and supreme commanders in a position of controlling all forces in their area. Probably as an extension of this principle he gave the theater and supreme commanders broad

discretionary powers.40 Perhaps as an extension of the delegation concept or perhaps as simply a reaffirmation of the normal staff and command doctrine propounded in the period between the wars, theater and subordinate commanders tended to de-emphasize the operating and coordinating functions that members of their special staffs could perform for their own services. Dual exercise of staff and command functions, as permitted by regulations,41 became virtually unknown, at least in the CWS. As logical and necessary as was the emphasis on command authority and control, it did not make any easier the operation and control of a service which fitted neither into staff nor command lines. Fries had found it necessary to be a salesman in 1918, but, since he controlled CWS staff officers down to the division level, he had a better means than Rowan, two decades later, of conducting his sales campaign.42 Rowan perforce substituted liaison between his office and the chemical and command elements of the various theater commands for control of his chemical subordinates as a means of selling chemical warfare munitions and services.43

Rowan’s problems were many in molding his staff to constant liaison with the British, with the ground and air forces, and with the zone of interior. In addition he possessed SOS supply and liaison duties which would normally have devolved upon a communications zone chemical officer. He still lacked officers in sufficient numbers and with sufficient rank to handle all liaison and operating duties.

The April Reorganization

When General Porter left the theater, Rowan asked him to carry back to Washington a list of proposals for less hurried consideration.

These proposals related to Rowan’s desire to increase the strength and prestige of his immediate office in order better to perform both liaison and operating functions. Foremost on this list was a request for the return of Colonel Johnson from the North African theater or the dispatch of a well-qualified lieutenant colonel to head his Supply Division. Rowan also asked for four or five majors, high-ranking captains, or low-ranking lieutenant colonels with staff experience and training. He further asked that Col. James H. Defandorf and an officer assistant, who had recently been assigned to his office to work on medical liaison and the new, and then secret, work on defense against biological warfare, not be charged against his allotment since their work was on a special project basis and since he desperately needed the spaces.44 The request for Johnson or a substitute was not intended to disparage Major LeRoy whom Rowan later called “my very best supply officer,” but it was intended to point up the fact that LeRoy was still the only field-grade supply officer available and that the important supply operation needed more rank and prestige.45 The request for majors, captains, or lieutenant colonels was necessary because the CWS needed field-grade officers for staff positions, but the space allotment was such that Rowan could not risk taking a full colonel or a lieutenant colonel about to be promoted.46

Porter’s reply to Rowan’s requests demonstrates that Rowan did not yet realize how weak the ties between the theater CWS and its parent service had become with the growing strength of ASF, OPD, and the theater organizations. Porter pointed out that the matter of Johnson’s transfer from the North African to the European theater was out of his hands: it could only be handled officially by intertheater request. Porter could and did attempt to smooth this process by asking a chemical officer in North Africa to intercede in favor of the transfer, but nothing came of this attempt. On the matter of Colonel Defandorf’s status and on that of securing additional staff officers for Rowan, Porter’s hands were equally tied since the status of officers within the theater as well as requests for additional personnel were considered to be within the province of the theater commander. Porter agreed to evaluate qualifications of officers to be sent upon receipt of the official

request, but even in this there was a strictly limiting factor—officers with staff experience were hard to find in 1943.47 It began to appear that the solutions for staffing and prestige problems must be found in the European theater.

In April 1943 Rowan reorganized his own office to reflect the expanding responsibilities of the CWS ETO and for better liaison. He took the Intelligence Section from the Administration Division and made it a division with Maj. Philip R. Tarr, recently promoted, as chief. The creation of a new division was no duplication of Colonel Zanetti’s efforts. Zanetti specialized in strategic intelligence and intelligence liaison with the British and with the continental United States while Tarr assumed the growing burden of chemical tactical intelligence, which also involved liaison with the British but at a different level. The Intelligence Division continued to process attaché reports for Colonel Zanetti.48 Lt. Col. Maurice H. ‘Wright, also recently promoted, headed a new Supply Liaison Division whose chief function was to effect coordination between London, where broad supply policy was determined in the Operations and Training Division, and Cheltenham, where direction of all requirements and supply operations remained. Wright’s procurement and reciprocal-aid duties were delegated to an assistant with the title of branch chief. The Administration Division, now headed by Lt. Col. Chester O. Blackburn, included three office service branches and one branch to handle personnel for the CWS as a whole. The Technical Division, with its important liaison functions, was assigned more higher ranking officers than the other divisions: Colonel Scott remained as chief; Colonel Defandorf headed the Special Projects Branch; Lt. Col. Melville F. Perkins handled liaison with Porton, the British chemical research establishment, and the CWS Laboratory, for which a chemical laboratory company had not yet been received; Lt. Col. Thomas H. Magness, Jr., was in charge of Offensive Munitions Branch while a captain headed the Defensive Munitions Branch. In Operations and Training Branch, Colonel MacArthur had a Training Branch headed by a lieutenant colonel, who was also his executive officer, an Equipment Branch, and a Plans Branch.49

LeRoy, now a lieutenant colonel, had 20 officers in his Supply Division, but he still lacked field-grade assistants. His Executive Officer and Chief, Statistical (requirements and control) Branch, and his Operations Branch chief had been promoted to captain along with the Transportation and Issue Section chief. The Processing (formerly Impregnating) and Training Branches were still one-man branches while the Service Branch had a chief and an assistant. One-man branches were common in the London office where five branches were wholly unstaffed. The London office was assigned 22 officers, three of whom were on duty with the Administrative Branch of the Administration Division at Cheltenham. In all, Rowan had 41 officers, 28 enlisted men, and 16 civilians.50 While 14 officers had been added since the previous fall and while section prestige had increased, mostly through promotions, both members and prestige were still low in relation to the tremendous expansion in theater activities contemplated in the year before the D-day target, which was established in May. Rowan had a personal prestige problem in that the other technical service chiefs had all been advanced to general officer grade.

The First Gas Warfare Plan

An example of the contemplated expansion of theater activities was the issuance, also in April 1943, of the first theater gas warfare plan. Enough strategic information had become available by that time to complete the draft plan of the previous December. The final plan, personally signed by General Andrews, called for an eight months’ supply of aircraft gas munitions and a four months’ supply of ground gas munitions. The theater requested, in the event of gas warfare, at least 2 chemical combat battalions per corps, 40 air chemical service and supply units, 30 ground chemical service and supply units plus 5 smoke generator companies for ground service, and 23 SOS service and supply units plus 5 smoke generator companies for the communications zone. It also requested 3 base section staffs totaling 9 officers and 30 enlisted men, 75 officers and 150 enlisted men for depot administration, and an SOS headquarters staff of 93 officers and 339 enlisted men. Pointed out in the plan was the fact that the theater was then

capable only of passive defense and individual protection against gas warfare.51

The theater and air forces chemical sections modified the plan’s supply and troop build-up schedule to make it accord with the current theater build-up level and the nongas warfare situation. They then submitted requisitions against the modified schedule, but while cargo flow began to increase, needed supplies, especially toxic munitions, were not forthcoming. A month after the submission of the theater plan, Maj. Gen. Ira C. Eaker, Commanding General, Eighth Air Force, forwarded a strong plea for an interim toxic munitions supply plan.52 By the end of July, General Eaker’s plan had been approved for munitions shipment. But long before the approval was received—in fact, before the original Eighth Air Force interim plan had been dispatched—Rowan had become concerned about War Department slowness in handling theater requests and particularly about the burden placed upon the theater by the necessity of planning and replanning. Rowan expounded the theater point of view to General Waitt, Assistant Chief, CWS, for Field Operations, early in May 1943. He considered it to be the function of the War Department “to assist overseas Commands, and not to attempt to sit in judgment upon their actions and requisitions.” He further indicated that he believed the policy of requiring theater commanders to disclose detailed plans of contemplated operations in justification for requisitions of an unusual nature to be an unsound one.53 Waitt replied that he, personally, agreed completely, and he gave assurance that his own office would not attempt to “sit in judgment on theater requests or actions.” He asked only that the theater keep his office well enough informed so that the War Department CWS might “go to bat for you.” He pointed out that the War Department higher echelons had to know enough about plans of contemplated operations to act intelligently on requests.54

The higher echelons which Waitt defended were not always as reasonable as he was in considering theater requests. Porter, Waitt,

and Rowan were satisfied that the CWS in the United States was doing everything in its power to assist the theater CWS in meeting its obligations as to organization, planning, and supply.55 Waitt placed the blame for delays and for modification of theater plans on ASF.56 While approximately ten weeks was not an extraordinary amount of time for War Department action on the Eighth Air Force request, this request was only one of a stream of Eighth Air Force schedules and plans which had followed from the original plan made in April 1942 when Kellogg’s section was still in the United States. In many other cases, such as the projects for continental operations begun in mid-1943, the processing delays seemed longer than final results warranted. The theater CWS found itself in a frustrating position: the theater staff was to plan in detail within the framework of the basic plans laid down in Washington because the War Department would not invade the theater prerogative by doing detailed planning; but the War Department apparently felt no compunctions about redoing the theater’s detailed planning. A like difficulty existed in organization. The prewar theory of theater organization, under which the theater commander channeled authority through his technical services chiefs as well as his tactical commanders, had been discarded in the ETO under War Department pressure so that the planned channels of authority no longer remained, yet the War Department did not consider the provision of a new authority channel as being within its province.

The June Organization Plan

In June the ETO SOS chief of administration asked Rowan to submit his plans for handling the theater build-up load. Rowan’s plan reflected his desire to meet both problems. If he could have direct control of the theater CWS organization, he wanted enough officers of sufficient rank to control it by persuasion. If he must do the planning which, according to the manual, should have been done in the United States, and if he must perform the operation normally the responsibility of the communications zone, he wanted the staff to handle planning and operating functions. Rowan replied by submitting a comprehensive organizational and functional justification for a staff of 100 officers.

He asked for a deputy and two assistant chiefs but suggested that the position of deputy and one of the assistant chief positions could be held by one officer. While MacArthur had in fact been deputy since August of 1942, he had in title been Executive Officer and Chief, Operations and Training Division. Rowan proposed that he should officially be deputy and assistant chief for plans and training. As mentioned above, Rowan had become “outside man” for his organization, so that he needed a deputy who could function in his absence. He also needed an additional executive officer who would be “inside man” and function in his or his deputy’s stead when both were absent. The second assistant chief was to be the operating supervisor of supply and service functions. Since half of Rowan’s staff was to be occupied with these functions and since this portion of the staff was located at Cheltenham, he felt that the position warranted the assignment of a general officer. Considering the growth of the technical services within the theater and considering that the CWS ETO was destined to become fourth ranking among the seven technical services in the operation of general storage space and second ranking in the operation of ammunition storage and shop space, and further considering that the Cheltenham echelon was charged with the chemical warfare training of about 375,000 SOS troops, the establishment of an assistant chief position in the general-officer grade was not unreasonable.57

Since Rowan planned for his deputy to hold the position of assistant chief for plans and training, there seems to have been little reason for establishment of the second position of assistant chief except the psychological factor of acknowledging the unique position of the CWS chief as tactical adviser in chemical warfare to the theater commander and to all theater forces. A subsidiary reason for establishing the second position could have been to parallel the OCCWS organization which had recently been revised to provide assistant chiefs for matériel and for field operations.58 In effect, the two assistant chiefs in the ETO would perform comparable functions to the two in OCCWS. Only one officer, a lieutenant colonel, to act in an executive capacity, was to be assigned directly to the assistant chief for plans and training.59

Six of the nine divisions proposed were to be organized on the pattern already established in the Technical Division—colonels and lieutenant colonels would primarily perform liaison and inspection functions outside the Office of the Chief Chemical Warfare Officer. These divisions were: Technical; Plans and Training; Intelligence; Medical Liaison; Supply Liaison and CWS Representative to AC of S, G-5, ETOUSA; and SOS Training (at Cheltenham) . The liaison divisions were to contain branches or sections staffed by lower ranking officers and enlisted men to perform planning, supervisory, and reporting duties. Colonel Wright had already been appointed CWS representative to ACofS, G-5, ETOUSA, in addition to his duties as Chief, Supply Liaison Division. His duty as representative consisted of liaison with the Allied forces planning command (Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander [Designate] COSSAC) . The SOS CWS Training Division, to be headed by a major, was to operate under the assistant chief for supply.60 The SOS CWS Training Division was not to duplicate the training policy role of the training element in London, but was to provide staff supervision for chemical training within SOS.

Rowan meant for two of the remaining three divisions to handle internal administrative functions, but both of these divisions, Administration in London and Supply Administration in Cheltenham, were also to have advisory roles with respect to the assignment of CWS personnel in the theater and in SOS, respectively. Rowan and LeRoy redesigned Supply Division to re-emphasize the position that this division had always held as an independent CWS supply and service agency which LeRoy operated, on a small scale, under Somervell’s and Lee’s principle of centralized control and decentralized operation. Supply liaison at levels coordinate with and above SOS was to remain in Wright’s hands in both of his capacities. Liaison at SOS level was to be accomplished by the division itself. To supplement the division liaison at subordinate levels, Rowan and LeRoy wished to create an Inspection Branch headed by a lieutenant colonel who would be a troubleshooter for field problems and carry on technical inspection of field installations. The pattern of liaison, and indeed the organizational plan of the whole division, demonstrated how free a hand the CWS had in determining its own supply concepts and procedures. The division was to have, and in most cases already had, branches or

sections to determine requirements, to control matériel, to ordain storage, issue, and transportation procedures, and to regulate maintenance and services such as processing.61 In sharp contrast to the practice in the Pacific areas, policy could originate within the division or with the chief chemical warfare officer; higher level direction was minimal.

As far as his own office was concerned, Rowan had already implemented a part of the organization of the June plan, since that plan did not differ greatly in pattern from the reorganization of April. Some features of the new plan, such as the official designation of Colonel MacArthur as deputy and the appointment of an executive officer, were implemented piecemeal. The post of assistant chief chemical warfare officer for supply was established, but Rowan could find no one to fill it. Several colonels arrived in the theater during 1943, but they were either already assigned to the staffs of field organizations or were needed in the rapidly proliferating field headquarters. Rowan was forced to use captains, majors, and some lieutenant colonels in positions he had intended to fill with lieutenant colonels and colonels. For liaison and inspection he sometimes sought the assistance of field chemical officers. He was still short of manpower. At the end of 1943 his officer allotment totaled forty-six. In Cheltenham he lost Colonel LeRoy who was returned to the United States under a policy of rotating officers with field experience. Major Powell, who had filled assignments both in Cheltenham and in the SOS depot system, became LeRoy’s replacement.62

The importance of the June plan does not lie in its implementation, although it was implemented at about half strength and became the basic pattern for the remainder of the war. Its importance lies in the fact that its concept and scope demonstrate the changed character of the overseas CWS in World War II. It represents the anomaly of World War II: the technician and the specialist were taking a back seat in the war which was being touted as the technicians’ and specialists’ war. The technician, the specialist, and the logistician, had achieved positions of great importance in the warfare of World War I. In the period between the wars most CWS technicians, specialists, and

logisticians had been led to believe that they would work with bureau-like unity. Strategy, plans, matériel, and personnel would emanate from OCCWS to be translated into the theater commander’s policy by the theater chief chemical officer who would supervise execution at subordinate levels. More than a year’s experience in the theater proved that the interposition of theater headquarters, OPD, and ASF between the theater CWS and OCCWS prevented OCCWS from accomplishing its planned direction. Theater emphasis on the discretion of the individual commander, plus the organizational setup, in effect demoted the special staff officer to the role of supply administrator whose control even in the supply field depended on his ability to institute and maintain decentralizing procedures. In the supply role Rowan and his staff fared very well despite the failure to acquire the personnel specified in the June plan. In the liaison role the failure to acquire the staff and rank indicated in the June plan threw the entire burden on Rowan and a few members of his staff. The Technical Division very successfully maintained liaison with the British in the research and development areas.63 CWS officials also found the British very helpful in arranging reverse lend-lease for service and supply, areas in which Rowan and many members of his staff performed liaison.64 In matters of policy, liaison with the British was excellent since Rowan was Porter’s representative to the British policy group, the Inter-Service Chemical Warfare Committee.65 It was in liaison with the American ground forces that difficulties arose. So small a staff with such varied duties could not maintain a regular ground forces liaison program. The partial solution for this problem was to emerge later during operations on the Continent.

Planning and Organization: 1944–45

By the end of 1943 the build-up in the ETO had reached a furious pace. All the CWS ETO supply installations and sections in the United Kingdom were firmly established and supplies, even the long-awaited toxic munitions, were coming in. In the SOS the base sections, the ports of debarkation, and selected general depots had working-strength chemical sections, and scarce chemical service units or detachments

were attached where necessary for operation. Arriving ground force organizations usually brought their own chemical sections.

Staff and Organization Changes

Many staff changes were made—some the result of organization and unit activations and some arising from a desire to have officers with theater experience in the United States. As noted above, Colonel LeRoy had for the latter reason returned to the United States in the fall of 1943. Colonel Kellogg had returned to the United States in July 1943 and his position as Chemical Officer, Eighth Air Force, had been assumed by Col. Harold J. Baum who subsequently became Chemical Officer, United States Strategic Air Forces in Europe (USSTAF).66 One lieutenant colonel from Rowan’s London staff also returned to the United States, while Colonel Blackburn left the Administration Division to become Chemical Officer, Ground Forces Replacement Command, in the theater.67 Three field-grade officers arrived from the United States for duty in the London office.68

With the organization of several ground commands late in 1943, the build-up reached the point where defensive gas warfare planning for specific forces had to be undertaken with a probable cross-Channel mission in mind. The requirements portion of such specific planning depended upon the ground forces elements themselves, but Rowan’s staff would be called on to coordinate planning and, more importantly, to translate plans and estimates into actual supply. The fact that supply lead time was running at about 180 days impressed Rowan’s staff with the necessity of anticipating the requirements of ground forces planners as far ahead as possible. Just before leaving for an extensive briefing and conference tour in the United States late in December 1943, Rowan designated a transitional Planning Group within the Operations and Training Division to work under the direct supervision of the deputy chief chemical warfare officer, Colonel MacArthur. This group was, in addition to its planning duties, to absorb the functions of the Supply Liaison Division.69 A few days later, MacArthur, acting chief chemical warfare officer, brought about

Chart 4: Organization of Chemical Warfare Service Section, Headquarters, European Theater of Operations

Source: Adapted front: Ruppenthal, I, 191-201, CWS SOS ETOUSA, Office Orders No. 23, 4 Jan 44, No. 25, 25 Jan 44. ETO Ad.” 544.

a realignment of the theater office. (Chart 4) The Planning Group became the Planning Division under Lt. Col. Albert C. Bilicke, with Maj. Arthur T. Hingle, who was moved up from Cheltenham, and another field-grade officer as his principal assistants. This division was given the task of determining broad troop and supply requirements for future operations. The parent Operations and Training Division had like responsibilities for current operations as well as for training supervision.70

The other divisions remained as indicated in the modified plan of June 1943, but a sign of the times was the appointment of Maj. Alexander Leggin, Executive Officer, OCCWO, ETO, to the added role of liaison officer to First United States Army Group (FUSAG) Leggin’s verbal instructions were to initiate the formation of a chemical section and to start chemical planning for FUSAG, then organizing in the United Kingdom as the principal American ground forces headquarters.71 Also, Maj. William Foley came from the American School Center to Cheltenham to head an SOS Training and Equipment Section, an upgrading of the Training Branch, Supply Division.72 By the end of January it had become apparent that the Operations and Training Division could not handle all the detailed transactions concerning troops. A new Personnel Division was therefore established, and to it were assigned the personnel records functions of Administration Division.73

The Personnel Division had a number of individual changes to record. Col. Marshall Stubbs in January had moved from Ninth Air Force to establish the chemical section for and become the deputy assistant chief of staff, G-4, of Advance Section, Communications Zone (ADSEC) , the mobile base section scheduled to operate directly behind the combat forces. ADSEC, as an important distribution agency and link between combat and SOS forces, was of considerable interest to the CWS ETO. The ability to discover ground forces chemical supply requirements and to meet them could well depend on the successful operation of the ADSEC Chemical Section. Maj. Ingalls S. Bradley of Supply Division soon joined Stubbs as his

assistant.74 Leggin left his executive officer post in February formally to activate the FUSAG Chemical Section.75 In March, after Rowan’s return from the United States, MacArthur became FUSAG chemical officer with Leggin serving as his deputy. Col. Alfred C. Day, a Reserve officer and veteran of World War I’s 1st Gas Regiment, who had been on temporary duty as chemical officer of the assault and amphibious training center in England, became Rowan’s deputy.76 Col. Roy C. Charron, another Reserve officer with World War I experience, arrived from the United States to assume, after briefly filling the long-vacant position of assistant chief at Cheltenham, the post of Chemical Officer, Forward Echelon, Communications Zone (FECOMZ) . The Forward Echelon was essentially a planning headquarters, a smaller version of SOS itself, which was to plan for and provide logistical support to the combat forces on the Continent from D-day plus 41 to D plus 90 when the main headquarters of SOS, renamed Communications Zone (COMZ) , was expected to be in operation on the Continent.77 The CWS SOS—COMZ complement was filled in May by the arrival of Col. Hubert B. Bramlet, a Regular Army officer who had been commissioned in the CWS during World War I, to fill the position of assistant chief at Cheltenham.78 (Chart 5)

The change in staff assignments and the addition of the ADSEC and FECOMZ Chemical Sections enabled the CWS ETO to operate more effectively within the theater. Officers entirely familiar with the theater CWS system, such as MacArthur, were now in key positions while the new chemical sections were created in new organizations designed within the theater to serve theater purposes. These organizations therefore had channels of communication, authority, and operations specially suited to theater needs. Thus FECOMZ was a planning headquarters with “built-in” liaison to the parent SOS.79 ADSEC was

Chart 5: Actual Distribution of Service Agencies and Combat Units Chemical Warfare Service, European Theater of Operations, 1944–1945

a. Position abolished, October 1944.

b. January 1944 reorganization. Allied Expeditionary Air Forces abolished 15 Oct 44.

e. First and Ninth Armies attached to the Northern Group for periods in 1944-1945. Fifteenth Army added to 12th Army Group in 1945. Chemical Officer, 12th Army Group, conducted liaison with chemical officer (British), 21 Army Group.

d. As of December 1944.

e. Theater and Communications Zone (then Services of Supply) Headquarters combined, January 1944.

f. Base Air Depot Area supported Eighth and Ninth Air Force Service Commands in some functional areas.

e. Fifteenth Air Force under USSTAF operational control. Under administrative control Mediterranean Allied Air Forces.

Source: Pogue, Supreme Command, pp. 159, 262, 379, 428, 455. Ruppenthal, Logistical Support of the Armies Vol. I p. 199.: Craven and Cate, Europe—TORCH to POINTBLANK pp. 145, 753, 039; Craven and Cate, Europe—ARGUMENT to V-E Day pp, 111, 398, 576,

a planning headquarters with “built-in” liaison to First Army (FUSA) and Third Army (TUSA) , whose basic logistics planning it was handling and extending, as well as to SOS–COMZ, of which it was an organizational subordinate echelon.80 The ground forces–CWS ties were therefore good.

First Army, whose chemical section was headed by Col. Joseph D. Coughlan, was to direct all American operations on the Continent in the beachhead period. FUSAG coordinated all ground planning, and a successor army group headquarters, as yet unannounced, was to take over control of First Army and Third Army when the “secret” Third became operational. Third Army chemical officer was Col. Edward C. Wallington.81

Air Forces liaison was more tenuous. Air Forces officers, probably as part of their bidding for a status independent of the Army, took the position that the theater and SOS headquarters had a ground forces jurisdiction only, even in logistics matters. Since Rowan and his staff were firmly identified with theater and SOS headquarters, they were doubly handicapped in approaching the Air Forces. The CWS situation in the Air Forces became worse when USSTAF combined its Ordnance and Chemical Sections under the ordnance officer, but Colonel Baum in USSTAF, Col. Joseph Triner, chemical officer in the Ninth Air Force, and Maj. Leonard C. Miller of Allied Expeditionary Air Forces (AEAF) managed to keep Rowan informed of their more important plans through their personal channels to the chief chemical warfare officer and his assistants.82 After January 1944 the planning channel for the Air Forces was through the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces (SHAEF) , rather than through theater headquarters. In January theater and SOS headquarters were combined with the staff serving in a dual capacity. While General Lee became deputy theater commander, the staff carefully defined their theater functions which they performed in General Eisenhower’s name and their SOS functions which they carried out in General Lee’s. Despite the careful definition, the activation of other operational and planning commands restricted the combined headquarters to administrative and

supply matters and ultimately resulted in the predominance of logistic function.83

In March Col. Adrian St. John arrived in the theater and became the chemical representative on the SHAEF staff. Although Colonel Wright, as liaison officer to COSSAC, the SHAEF predecessor, had been on Rowan’s staff, Colonel St. John did not report to Rowan. The air forces chemical officers coordinated their gas warfare planning with St. John. Organizational confusion resulted.84 Even General Porter believed that Rowan was no longer the principal chemical officer in the theater. He was under the impression that St. John, who was at the time senior to Rowan, had been appointed “Chief Chemical Officer, SHAEF,” and he asked Brig. Gen. Augustin M. Prentiss, who was on an observer mission to the theater, to indicate proper communications channels.85 Prentiss replied that the confusion in the United States was understandable since many individuals in the theater were also confused, but he affirmed Rowan’s position as theater chief of service, and St. John’s as chemical adviser to G-3, SHAEF, and indicated that communications should be channeled through Rowan.86 Rowan’s status became more clearly defined upon his advancement to brigadier general on 25 May 1944.

During the three months of his European duty before the continental invasion, St. John assumed some of the gas warfare readiness planning responsibilities as appropriate to his assignment to the highest planning headquarters. He approved and staffed air forces operational readiness plans which included stocking toxics available for immediate retaliatory missions at operational airfields. He also secured the issuance of a SHAEF directive which required all commanders to make both offensive and defensive plans. Again, Porter was apparently under the impression that this directive had greater significance than it actually did.87 The SHAEF directive was in fact only a slightly stronger restatement of a number of theater directives which had preceded it,

and the real key to readiness lay in the supply planning which was being handled by Rowan’s office, the air forces chemical sections, and the chemical sections in FECOMZ, ADSEC, FUSAG, FUSA, and TUSA.

The liaison method of planning and the organizational confusion in the theater made chemical planning difficult at times and occasionally resulted in personal differences which normally occur in any organization, but both Rowan and St. John could informally handle problems as they arose. One problem was that Coughlan was reluctant to submit to direction and coordination by the FUSAG Chemical Section or by Rowan’s staff. St. John managed to bring this matter to the attention of the FUSAG commander and planning coordination thereupon became effective. On the whole, both planning and actual preparations in the field proceeded apace.88

When Porter indicated to Prentiss that, according to the reports, unspecified, which he had received, something was amiss in ETO chemical activities Prentiss replied that he could find nothing wrong. Plans were complete, the staff was competent, the supply situation, at least for immediate needs, was good, and the chemical officers seemed to enjoy the confidence of higher authority.89 In fact, Rowan felt that he had done precisely as Porter had recommended—he had “sold” his services to the theater forces.

General Porter got the same impression that Prentiss did when he arrived in the European theater shortly before the cross-Channel attack. He inspected gas warfare readiness in both ground and service commands. He found no reluctance to acknowledge Rowan as the theater chief chemical officer and he found theater forces well prepared, from a CWS point of view, for the operation they were about to undertake.90

On the Continent

American commanders and staff officers knew that the assault on the Normandy beaches provided the enemy with an ideal opportunity to inaugurate gas warfare. General Omar N. Bradley, then First Army commander and principal United States ground commander for the assault, later wrote that “even a light sprinkling of persistent gas on

Omaha Beach could have cost us our footing there.”91 American intelligence experts believed that the German forces had the logistic capability to launch a gas attack although it was a comfort to know that their lack of aerial superiority made it unlikely that such an attack could be launched by aircraft. All assault forces wore antigas protective clothing and carried gas masks and other protective articles. While the adequacy of such protection was assured against known gases in a situation in which warning could be given, the danger of a high casualty rate was great in the event of surprise attack or the introduction of an unknown gas. Further, the adequacy of the warning, service, and retaliatory offensive systems could only be estimated.

First Army requested 3 chemical mortar battalions for retaliation and 4 chemical service companies to meet possible gas warfare. The 3 battalions, 1 chemical depot company, 1 chemical maintenance company, I smoke generator battalion headquarters and 4 companies, and 1 small detachment from a chemical laboratory company were assigned or attached to FUSA and scheduled for the assault echelons. The laboratory detachment and 3 chemical decontamination companies assigned to engineer special brigades joined the earliest assault waves with the mission of determining if gas was being used. These units were to identify the gas and take immediate protective measures.92

The first chemical staff sections ashore in Normandy were those in the headquarters of the engineer special brigades, the V and VII Corps, and the 1st, 29th, 4th, and 30th Divisions. Three officers of FUSA Chemical Section landed on 9 June, three days after D-day. They found the chemical supply situation adequate and the 30th Chemical Decontamination Company ready to provide artificial smoke protection if needed. The fear of enemy gas attack was still lively as demonstrated by several “gas scares,” reports that the enemy had employed war gases. All such reports proved false.93

Since First Army was responsible for all logistics arrangements on the Continent in the early period, the first job was to establish dumps, especially dumps at which the chemical mortar battalions could draw ammunition. The initial supply of several chemical items, including

ammunition, was being expended faster than anticipated. The FUSA Chemical Section and the assigned chemical service units handled these problems. Officers of the ADSEC Chemical Section, who had arrived a day after Coughlan and his assistants, assisted the FUSA section in these tasks.94

The ADSEC Chemical Section gradually assumed direction of the distribution functions in the areas nearest the beaches. The FUSA Chemical Section retained its direct interest in all chemical supply since FUSA did not relinquish supply control to ADSEC.95 During July the FECOMZ, TUSA, and 12th Army Group Chemical Sections were established on the Continent as the headquarters of which they were part became established. FECOMZ never assumed operating responsibility and the members of its chemical section, like those of Third Army and 12th Army Group, acted as observers and reporters on the combat, supply, and service situations until early August when the main COMZ (formerly SOS) headquarters began to arrive and absorb FECOMZ. Members of the chemical section then assumed their planned operating roles. Third Army and 12th Army Group became operational on I August 1944 and MacArthur’s chemical section became the senior chemical policy organization on the Continent pending the arrival of the remainder of Rowan’s office.96

Rowan, Day, and St. John visited on the Continent during the beachhead and breakout period (June—August 1944) , as did General Porter.97 They found little evidence of any enemy intention to initiate gas warfare, but, as insurance the CWS sections and units ashore were striving to increase and improve the level of gas warfare protection by collecting and refurbishing discarded gas masks, by distributing decontaminating equipment and supplies, and by setting up antigas clothing processing plants. The chemical mortar battalions were fully occupied and highly prized in their nongas warfare role, an intended one, of firing high explosive and smoke missions in direct combat support of the infantry. Artificial smoke, other than that produced

by white phosphorus shell, had not been used in expected quantities, and expensive fog oil, the smoke agent used in mechanical smoke generators, was being used to oil emergency aircraft landing strips. The smoke generator units were used as service units. The chemical supply situation was satisfactory at the moment, but Rowan and St. John predicted growing supply problems as the mortar battalions became more extensively used and the distribution area for smoke, flame, and gas warfare supplies became larger. From Rowan’s point of view the most immediate problem was the supply and allotment of CWS officers and enlisted men, particularly those for the chemical mortar battalions.98

While Rowan had organized a Personnel Division and expanded it into a Personnel and Troops Division, he did not control the assignment of CWS-trained men. All assignments in the European theater were made under the supervision of the ETO SOS assistant chief of staff, G-1, by the theater adjutant general or a command adjutant general or by the Ground Forces Reinforcement System. The assigning agency commonly considered all CWS officers and men as service troops and indiscriminately assigned individuals to any CWS vacancy. While such indiscriminate assignment produced some problems in service units, such as the assignment of decontamination specialists to maintenance units, the real difficulty arose in connection with CWS combat assignment. Mortar battalion commanders found they were receiving service specialists or clerks while CWS-trained combat soldiers were assigned to service units. Chemical mortar battalion commanders consequently requested infantry- or artillery-trained men in preference to those trained by the CWS. It was easier to retrain men who could be counted upon to have received basic combat training than it was to retrain CWS men who had no combat training at all.99

Rowan immediately began to tackle this problem both from the field end and from the theater staff end until he persuaded the theater adjutant general to consult the CWS in the allotment of both men and units. While it was still necessary to work through the theater

system, and while the preference of individual commanders could still outweigh OCCWO planning, this concession gave Rowan a much larger hand in the solution. Rowan and his subordinates were thereafter able to correct many inequities in chemical assignments.100

On moving to the Continent in September, Rowan began consolidating his offices. FECOMZ, its operational period having been curtailed on the one end by the extension of First Army’s control and on the other by the early arrival on the Continent of the main echelon, was absorbed into the COMZ headquarters. Little change was made in the theater chemical section organization when the section was established in Paris. The Supply Division carried on its day and night job much as it had in Cheltenham. The Technical Division remained in the United Kingdom with a liaison section in Paris. Colonel Bramlet remained in England to become Chemical Officer, United Kingdom Base Section, which was in fact a rear echelon of COMZ. The one significant change was the recombination, just after the arrival in Paris, of the Planning and the Operations and Training Divisions into a Planning and Training Division. Since there were no gas warfare operations, the concept of an Operations and Training Division as a successor to General Fries’ “military” offensive and defensive divisions faded completely, and toward the end of the war the division devoted itself to demobilization and redeployment planning.101 Since Colonel St. John had also primarily been employed in planning, his position was abolished in the fall of 1944. He, too, turned to demobilization work, mostly outside the CWS sphere.102

Rowan gave much of his personal attention to the problems of operating in a nongas warfare situation. The chemical mortar battalions were in considerable demand for close infantry support from the time of their debut on the Continent, but since their extensive use in a nonchemical role had not been envisioned before the war, there was no well-established body of doctrine relating to their employment. In the resultant controversy over infantry or artillery fire

direction, Rowan aligned himself firmly with the proponents of infantry control.103 Lacking the means to establish doctrine as a representative of the theater commander, Rowan chose to visit combat commanders to persuade them to use attached chemical mortar battalion elements under infantry control. Though he was sometimes frustrated in this attempt, Rowan usually found personal persuasion effective.104

The theater chief chemical officer also used personal persuasion in an attempt to secure the proper employment of smoke generator units. Since many commanders were unaware of the new techniques in use of smoke which had been developed in the Mediterranean theater, they were unprepared and unwilling to initiate the employment of smoke. As a result, many smoke generator troops made their way across France engaged in such miscellaneous activities as service and transportation troops. General Rowan tried to persuade field commanders to maintain the integrity of these units, to keep up their equipment and to employ them on their primary mission wherever possible. Smoke came into great demand for concealment in Germany when the river-crossing operations began. At that time many smoke units were recalled to their primary mission, but re-equipping and retraining was no easy task. Some units and their equipment had been so dispersed that they were never called back to their primary mission.105

Rowan’s activities on the Continent, such as those in connection with the mortar battalions and the smoke generator units, raise the question of the proper role, in the absence of gas warfare, of the Chemical Warfare Service and of the various staff chemical officers. Neither Porter nor Rowan felt that the absence of gas warfare significantly altered the basic mission of the CWS or of CWS staff officers. Both believed that Fries’s concept of a service in which “research was linked with the closest possible ties to the firing line” still applied.106 Although toxics had not been used and although the likelihood of their use became more remote with each succeeding month of the war, there was always the possibility that the Germans might use gas to cap the offensive which had created the “bulge” in the Ardennes, or to prevent the crossing of the Rhine, or in last-ditch defense of the