Chapter 10: Reorganization for Global War

The accelerated mobilization which followed the Japanese attack dominated military activities for many months. At the end of 1942 most of the Army was still in the United States and most of its weapons were still to be produced. By the summer of that year, however, the armed forces had begun to turn their eyes overseas. The landings in North Africa in November marked the end of a period of transition. The build-up continued, but it was ever more intimately related to specific military operations.

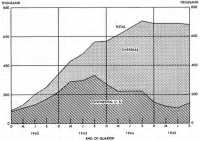

During the remaining years of the war, engineer troops increased not only numerically, as did most other services, but also in proportion to the Army as a whole. Only the Transportation Corps showed a similar trend, but the Transportation Corps was only about one third as large as the Corps of Engineers. In December 1943, with a strength of 561,066, the Engineers made up 7.5 percent of the Army. By May 1945, when the Army reached its peak, the Corps of Engineers with a strength of 688,182 constituted 8.3 percent of the Army. (Chart 5) Greater in numbers and proportionate strength than any other of the seven technical services the Engineers accounted for about 25 percent of the strength of this group. The Engineer procurement program reached its peak in December 1944 with the delivery in that month of over $190,000,000 worth of supplies. Dwarfed only by the programs of the Ordnance Department and the Quartermaster Corps, the value of Engineer procurement passed the billion mark in 1943 and the billion and three-quarters mark in 1944. While demands for the organization, training, and equipping of engineer troops continued unabated during the years of 1943 and 1944, the military construction program reached its peak in the summer of 1942. The value of construction work put in place in 1943 was $1,893,569,000 as against $5,565,975,000 in 1942. In 1944 the program shrank to less than half a billion.1

This decline in the military construction program left the Engineers relatively free to concentrate upon the task of preparing troops and supplies for action overseas. At the same time the acceleration of troop movements in the latter part of 1943 in anticipation of major offensives both in Europe and in the Pacific brought pressure upon OCE for greater flexibility and speed in training and equipping troops. On 1 December 1943, OCE was reorganized to conform with this shift in emphasis. (Chart 6} Its structure was to remain essentially unchanged until the war in Europe had been won.

At the top, the organization retained a

Chart 5—Total Number of Engineer Troops, Continental United States and Overseas: 1942–45

Source: Statistical and Accounting Br, Adm Sv Div, TAGO.

Control Branch for administrative management which reported to the Executive Officer, OCE. The rest of the organization reported to a newly created Deputy Chief of Engineers in the person of General Robins who had been Assistant Chief of Engineers for Construction. The Offices of the Assistant Chiefs of Engineers for Construction and for Administration were abolished and all divisions and branches formerly under them were placed under Robins. Supervision of the remaining functions was divided between two assistant chiefs of Engineers. Fowler continued as Assistant Chief of Engineers for Supply, in charge of the Procurement, Supply, Maintenance, and International Divisions, until July 1944 when he was replaced by Brig. Gen. Rudolph C. Kuldell. Sturdevant’s title changed from Assistant Chief of Engineers for Troops to Assistant Chief of Engineers for War Planning, symbolizing the shift of focus to the theaters of war. The War Plans (formerly Operations and Training Branch), Military Intelligence, and Engineering and Development Divisions were

Chart 6: Organization of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, December 1943

grouped under the Assistant Chief of Engineers for War Planning. In May 1944, Brig. Gen. Ludson D. Worsham succeeded Sturdevant in this position.2

On 12 March 1943 the command under which the Corps of Engineers had been administratively placed, the Services of Supply, became the Army Service Forces (ASF). Somervell had become aware during the previous year that there was indeed something in a name. “Services of Supply” was not descriptive of many of the organizations contained therein, he wrote the Chief of Staff. It had, moreover, “an unhappy association with the last war.” The title “Army Service Forces” would, he felt, “not only ... be more descriptive of the work assigned to us, but ... would remove stigma which has had an actual retarding effect in attaining the high state of morale which we must have if we are to accomplish our job properly.”3 Under the ASF the supply services became technical services. Although this title was more palatable to the Corps of Engineers, the dropping of the word “supply” did not gainsay the fact that ASF saw its main job as the procurement and distribution of matériel. It was in this area that ASF could and did make its greatest contribution. With the wartime demand for goods placing an ever-increasing strain upon the nation’s productive capacity, the ASF as a fighter for the Army’s share and as an allocator of that share within the Army could not but demand the respect even of those who would have wished to curb its power.4

For the Engineers, however, procurement and distribution of supplies were subordinate to their primary logistical task, which was construction. The Corps felt little need for guidance from ASF in the organization and training of troops to perform construction duties which had been part and parcel of the Engineer mission for many years. Insofar as the Engineers felt that ASF was inclined to slight this function, or worse still, to move in upon it in ignorance, the Corps was restive. In the late summer and the fall of 1943, moreover, the Engineers, and indeed all of the technical services with the possible exception of the newcomer, the Transportation Corps, had cause for extreme resentment against ASF.

From the outset Somervell had looked upon the organizational structure of ASF with disapproval. By the summer of 1943, thinking the time ripe for a change, Somervell and his advisers in his Control Division began to express alarm at overlapping functions and the resulting waste of manpower which inevitably accompanied them. For example, the Corps of Engineers was only one of seven technical services having procurement offices in Washington and in the field. Supervising them was Headquarters, ASF, and ASF’s field agencies, the service commands. This same type of overlapping was present to some degree in the performance of all the functions for which ASF was responsible. It could be eliminated, Somervell argued, by replacing the specialized, commodity type of organization represented

Brig. Gen. Clarence L. Sturdevant, Assistant Chief of Engineers, Troop Division (War Planning)., January 1942 until May 1944

by the technical services with a functional organization. In plain words the technical services were to be abolished.5

If the plan were carried out the Corps of Engineers would no longer be responsible for military construction; this job would be supervised by a director of utilities. Similarly, a director of personnel would take over the supervision of organization and training; a director of procurement, the purchase of engineer equipment; and a director of supply, its distribution. The Chief of Engineers was to be given, it was subsequently understood, a responsible position in the headquarters organization. The personnel of OCE and its field officers, insofar as they were needed, would be scattered throughout Headquarters, ASF, and its service commands. This goal was to be achieved in four steps beginning in October 1943 and ending in the spring of 1944.

Aware of the tremendous opposition that would develop if the ultimate aims of the reorganization were known to those who would be most affected, ASF planners confined their discussion of the plan to higher officials of the War Department. Marshall indicated his approval, but Secretary of War Stimson sought the views of Under Secretary of War Patterson, who displayed little liking for most of the changes. Unexpectedly, in late September 1943 the outlines of the proposal—somewhat embellished by avowed enemies of the New Deal—broke into the newspapers. In a story published on 25 September, it was stated that five ranking “conservative” officers, Reybold among them, were “slated to go.”6 In Somervell’s absence, Maj. Gen. Wilhelm D. Styer, his chief of staff, worked hard to overcome the hostility that Stimson and Patterson now unmistakably showed. Stimson and Patterson pointed to the fact, which no one in ASF attempted to deny, that the present organization had proved workable. While acknowledging that the proposed organization might be more efficient in theory, they feared its practical result would be the creation of bad feeling and loss of morale.

Upon learning that Stimson wished to talk over with those concerned the consolidation of training which was included as part of the first step in the reorganization, Styer called Reybold in for a conference. The Chief of Engineers was opposed to the loss of training functions, Styer reported to

Somervell afterward, but was not expected to “indicate any strong opposition.”7

The Engineers, meanwhile, had without fanfare made some organizational changes of their own as a reaction, it was later claimed, to the rumor that ASF intended to absorb the procurement organization. If the rivers and harbors divisions and districts were tied more closely to the procurement districts, it was suggested, ASF might be blocked. After all, the Commanding General, ASF, had nothing to say about civil works; for such matters the Chief of Engineers reported directly to the Secretary of War. On 1 September 1943 the Engineers brought all their civil works divisions and districts into their procurement organization. Whether this step, whatever its motivation, would have proved helpful in blocking the ASF reorganization was never put to the test. Secretary of War Stimson killed the scheme early in October.8

By 1944 passions had subsided. Perhaps indicative of the general feeling toward ASF at that time was Worsham’s statement in May, shortly after he became Assistant Chief of Engineers for War Planning: “While in your own mind,” he told his staff, “you may not approve of the organization of the Army, ASF does the best it can and they are the people with whom we have to work. Criticism gets back to them and consequently makes the situation even more difficult. The thing to do is to accept the facts and get the work accomplished even though there may be some obstacles that exist because of the magnitude of the organization of which we are a part.”9

In the organization and training of troops it was not simply the magnitude of the ASF organization that created obstacles. It was more explicitly the fact that engineer troops, like those of the six other technical services, were entering Army Ground Forces and Army Air Forces as well as Army Service Forces. Questions as to which of the three commands would control various types of units arose frequently. On the face of it the assignment of responsibility might appear simple: combat units to AGF; service units to ASF and AAF. The trouble was that service units were destined to be employed both in the combat and in the communications zones and AGF operated on the maxim that troops should be trained and become accustomed to working with units with which they would be associated overseas.

The reorganization of March 1942 had little immediate effect upon the responsibilities of the Chief of Engineers for the formulation of doctrine and the organization and equipping of troops. Except in the case of aviation units the Chief of Engineers retained his primary position in these matters, albeit under the direction of ASF. As before, he was expected to coordinate plans and recommendations with other services in case of overlapping interests. The complication arose originally between AGF and ASF in the training of units. Organizations such as maintenance companies, depot companies, and general service regiments, which functioned both in direct support of ground combat troops and in the communications zone, were subjected to dual control. Some were assigned to AGF for training, others to ASF.

The situation was further confused when it came to the troop basis. On 28 August 1942, the War Department directed AGF

Control of Engineer Units, January 1943

| Army Ground Forces | Army Service Forces |

| Special (amphibian) brigades a | General and special service regiments b |

| Combat regiments and battalions b | Separate battalions |

| Armored battalions c | Dump truck companies |

| Heavy ponton battalions | Forestry companies |

| Light ponton companies | Petroleum distribution companies b |

| Camouflage battalions and companies | Port construction and repair groups b |

| Topographic battalions (Army) and topographic companies | Topographic battalions (GHQ) |

| Water supply battalions | Equipment companies |

| Depot companies | Base shop battalions |

| Maintenance companies | Heavy shop companies |

a ASF was responsible for training and controlled T/O’s except for the period January-March 1943.

b Combat regiments, special service regiments, petroleum distribution companies, and port construction and repair groups are missing from the list of units contained in the 5 January 1943 document but are included here for the purpose of clarity.

c Also listed as AGF’s responsibility were: motorized battalions, airborne battalions, and mountain battalions.

to determine the number and types of service units required for direct support of ground combat units. The determination of units needed for service of supply functions was left to ASF. During the fall of 1942 the possibility of doing away with dual control was discussed and a compromise reached. Responsibility for service units (except those peculiar to AAF) was divided between AGF and ASF on the basis of so-called primary interest. For the most part this meant that units needed for direct support of combat troops would be under AGF’s control.10

The decision left some questions unanswered. Units of the technical services were not easily classified. In December 1942 the War Department laid down, for statistical purposes, broad definitions of combat and service troops. Engineer combat battalions, along with ponton and treadway bridge units, were classified as combat troops at that time. By the end of 1944, however, only divisional engineer units remained in the category of combat troops. Non-divisional combat battalions, ponton and treadway bridge units, amphibian brigades, engineer aviation regiments and battalions, and light equipment companies were designated combat support units. In 1944 the War Department also distinguished between two types of service units: combat service support units which would usually be employed in the combat zone, and service

support units which would usually be employed in the communications zone.11 It was substantially this 1944 line between the combat service support category and the service support category that the War Department tried to draw between AGF and ASF types of units in January 1943, when control of the organization as well as the training of engineer units was specifically divided as in table opposite.12

Changes in AGF Units

The redivision of responsibility for service units that occurred at the beginning of 1943 was a prelude to further reorganization of the Army’s tactical units. The generosity in the allocation of manpower and equipment which characterized the 1942 T/O’s lasted only a few months. The War Department soon discovered it did not have the inexhaustible supply of manpower and materials it had originally expected and was compelled to alter its strategy and redistribute its strength. Early in October the shortage of rubber and of cargo ships forced a review of all T/O’s with the purpose of cutting the number of vehicles 20 percent and the number of men 15 percent.13 At the end of that month the War Department warned that the great bottleneck in shipping “may dictate a considerable change in our strategic concept with a consequent change in the basic structure of our Army. Since ... it appears that early employment of a mass Army, which must be transported by water, is not practicable, it follows that the trend must be toward light, easily transportable units.” After the hope for a cross-Channel invasion during 1942 had faded, the War Department began to concentrate upon developing air power with the full knowledge that this step would “reduce the number of men available for the ground forces” as well as “complicate, if not curtail, the procurement of heavy equipment for other than the Air Forces.”14 In November the War Department cut from 140 to 100 the number of divisions that were to be ready by the end of 1943, and in February 1943 reduced the number still further to 90.

The 1943 reorganization of ground combat and service units was guided by all these considerations and by still others—not the least of which was the need to build a flexible Army that could fight a war under such diverse conditions as existed in Europe, the Mediterranean, the Southwest Pacific, and in India and other Far Eastern countries. Another factor of great consequence was the presence of Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair as commanding general of AGF. McNair upheld with great determination the principles for which he had fought during the reorganization of the thirties and specifically the belief that the most effective use of manpower lay in a concentration of maximum strength in fighting units, not service units. As a specialist on organization, McNair took a personal interest in almost every AGF unit which came up for review. This was not true of the other two commands. The AAF, which got preferential treatment in recruitment and matériel, did not face as much pressure to make economies in organization.

In ASF headquarters the organization of troops was of less interest than the execution of supply functions. Moreover AGF was better able to concentrate upon organization and training. AGF had no other tasks and a unity of approach was possible because the organization of AGF units could be tied to the functions and capabilities of the infantry division.

So far as AGF was concerned, the 1943 reorganization, like previous ones, began with the infantry division itself. The engineer combat battalion, sharing in the general cut, was pared from 745 to 647 officers and men—a reduction from 4.66 to 4.5 percent of the division’s strength. Trucks, antitank weapons, infantry support rafts, and the motorized shop, all of which had been added in 1942, were now removed. For the duration of the war the strength and structure of the combat battalion remained much the same as fixed by the 1943 tables.15

When the armored division came under McNair’s critical eye, it suffered a more drastic overhauling. The successful employment of antitank guns and mines against American armor in North Africa caused the Army to press for more infantry support in armored units. The 1943 T/O for the armored division cut tank personnel by 55 percent and increased infantry troops by about 20 percent. This step, taken in conjunction with the policy of economies in manpower, made radical cuts in other elements of the division inevitable. McNair personally insisted that the engineer battalion be cut more than 40 percent, to about the size of the combat battalion of the infantry division. It was inconsistent, he pointed out, to argue on the one hand that tracked vehicles could move easily cross-country and on the other to demand a large complement of engineers to repair roads. Armored engineers had never fallen back on road repair to defend their presence in the armored division. But the proponents of armor had indeed stressed the mobility of tanks to such an extent that they laid the Engineers open to McNair’s thrust. The wishes of everyone were fulfilled when the treadway bridge company was made a nondivisional unit. Thus detached, treadway bridge companies served all elements of the Army, since overseas commanders employed the treadway almost to the exclusion of all other ponton bridges. Under the table approved in September 1943 the engineer armored battalion—once again consisting of three lettered companies—numbered 693 officers and men. This represented a cut from 8 to 6.3 percent of the division’s strength.16

The number of divisional engineers had been reduced but their situation was far different from what it was in the thirties when McNair had wanted to limit them to a company. In July 1943 he wrote:

There is no lack of appreciation of the number of engineering functions or of the considerable overall strength of engineers needed. However, a division of whatever type is supposedly a mobile unit and [the] nature and extent of engineer operations under such conditions necessarily must be

limited. If and when operations do not move so rapidly, it is readily possible to introduce engineers from the corps and army, reinforcing or relieving the division engineers of functions which are beyond their capabilities.17

During the thirties there had been some discussion of establishing pools of troop units which could be drawn upon to augment divisional forces as needed for specific operations. To achieve this end the Army had relied for planning purposes on the concept of type corps and type armies which served as a means of determining how many nondivisional units would usually be required to support a given number of divisions. Prescribed T/O’s permitted the determination of troop requirements when the enemy and theater of operations were unknown. But even though used only for planning, type corps and type armies set up a rigid system comparable to that which would have existed had all equipment been assigned organically to units and none held in reserve for issue on demand. During the summer of 1942 McNair sought to eliminate this rigid system and to establish a more flexible means of providing the requisite supporting elements.

In his attempt to eliminate type corps and type armies, McNair had the Engineers’ wholehearted support. In August 1942 the Corps presented a plan, concurred in by Col. John B. Hughes, the Ground Engineer, to remove all assigned engineer units from type armies and type corps. “The use of task forces of various strengths in all types of terrain demands a flexible organization that cannot be provided by the present Type Army Corps and Type Army,” commented the executive officer of O&T. All engineer units in support of the division were to be placed in GHQ reserve. Combat regiments, to be made up of three battalions instead of two, were to be used for combat support. The separate battalion was to be eliminated and the general service regiment was to become solely a service unit, leaving one type of general unit, the combat regiment, in AGF, and one type, the general service regiment, in ASF. Finally the Engineers recommended the creation of a light equipment company to transport and operate the construction machinery that would be eliminated when combat regiments replaced general service regiments and separate battalions.18

To provide the desired pool of supporting elements once the type corps and type army were eliminated, AGF proposed the creation of a group headquarters organization to which a variety of units might be temporarily attached. Early in September 1942, Reybold agreed to go along with AGF’s desire to organize corps and army combat engineers on the basis of groups rather than regiments provided there were sufficient group headquarters commanded by colonels so that from two to six combat battalions could be assigned to them.19

It was substantially on this basis that combat engineer troops in corps and armies were reorganized. On 19 January 1943 the War Department directed that the battalion-group system replace the regiment. As AGF conceived of the group about this time, it could be a combination of three combat battalions, an equipment company, and a maintenance company, or some combination of combat, ponton, and other units. The general service regiment and the separate

battalion were eliminated from the combat echelon. This meant that construction in the combat zone would be performed by combat battalions and that there would be a greater depth in combat engineers. When operations slowed down, heavier reinforcements could be brought forward.

With the over-all framework for handling corps and army troops established, AGF turned its attention to removing what it considered fat from the special engineer units under its control. First to go was the light equipment platoon from the heavy ponton battalion. The AGF Reduction Board commented: “The light equipment was included in the battalion probably because a certain amount of overhead already existed to care for it, but the net result was to increase the service personnel of the unit and to bog it down with considerable transportation used to carry equipment that could be kept in depots when not in use. The battalion should not be a roving depot, but a tactical unit able to construct a heavy bridge.”20 Under the T/O issued in July the strength of the heavy ponton battalion was reduced from 501 to 369 enlisted men. Despite the fact that another raft section was added to the light ponton company to compensate for rafts removed from the infantry division, the new T/O effected a 5.5 percent cut in personnel without essential change of function. During the rest of the war ponton units operated with comparatively little change in organization.21

In the water supply battalion AGF found still another unit to trim. McNair questioned especially the necessity for the special tank truck. “Why cannot the water be delivered in five-gallon cans, since it must be transferred to such cans sooner or later? ... Why cannot this unit be made semimobile—that is the headquarters company be provided with a transportation section or platoon which would move the water supply companies as required? ... If delivery were by trucks and cans, these same vehicles could be used to move the units when necessary.”22 His deputy chief of staff, Col. James G. Christiansen, labeling the battalion a “fancy” unit, recommended that it be changed to a company with facilities for water purification and storage only. Water would be delivered in cans by trucks provided by the army commander. Over the protests of Hughes and of OCE, Christiansen’s recommendations were carried out in August 1943.23

The Engineers admitted there was no need for the water supply battalion in theaters amply supplied with water but insisted that in areas where water was scarce and in semipermanent camps a definite need for bulk transportation existed. As proof of their contention they cited the usefulness of the battalion in North Africa and Italy as attested to by high-ranking officers. But repeated efforts to restore transportation to the water supply company met with little encouragement until the 405th Water Supply Battalion, which had served in both of these theaters, submitted a report in the summer of 1944 that impressed McNair. Six months later the distribution platoon,

equipped with tank trucks, was restored, but the unit remained a company.24

Supply and Maintenance Units

The consequences of the division of engineer units between AGF and ASF are nowhere more strikingly illustrated than in the organization of supply and maintenance units. The park battalion, which had been provisionally organized in the prewar period to test the possibility of coordinating engineer supply and maintenance functions, never materialized. In its stead the Engineer Board had proposed an engineer maintenance and supply regiment, but Fowler had joined Sturdevant in disapproving such a large unit and had advocated instead a headquarters and service company to handle supply and administration for small units. Fowler’s idea seems to have been the genesis of the engineer depot group headquarters and headquarters company, the T/O for which was formally submitted to ASF on 16 November 1942 and approved the following June for a complement of 11 officers and 62 enlisted men. The Engineers expected to use this unit near a port of embarkation or at a fixed base. As with the park battalion, they contemplated attaching depot, shop, equipment, and various other units to the new organization.25

The study of the maintenance and supply regiment led in still another direction. In the 1941 maneuvers it became evident that the Engineers would require a separate organization to take care of spare parts. The Engineer Board stressed this fact in its report on the maintenance and supply regiment, and during the summer of 1942 OCE had taken up the proposition. Under Smith’s direction a depot company was experimentally organized into a parts supply company at the Columbus depot. On the basis of this experience the Engineers in November 1942 perfected a T/O for a parts supply company of 7 officers and 191 enlisted men which would function as part of a depot group. This ASF unit was designed to handle a stock of 100,000 to 300,000 spare parts in first, second, third, and fourth echelon maintenance sets on all of which accurate records would have to be kept.26

When the T/O of the parts supply company was referred to AGF for comment, Hughes expressed the view that “the parts supply company is an essential part of equipment maintenance. ... Unlike many new tables, this has been built up by trial, and is believed to be about right for the purpose intended. There might be four or five such organizations in the world.”27 The official AGF view was entirely different.

Christiansen, though an Engineer himself, indulged in an acid comment which revealed the limitations of the single-minded AGF approach of concentrating upon combat units.

In our present stage in which we are cutting down organizations, no reason is seen for approving such a unit. We would do this if we commented on the set-up without indicating that we can see no reason for the proposal.

This is just another case of adding overhead to the SOS, however, it is probably none of our business to tell them that; that being a WD function. Therefore rather than comment on the small points of the proposed organization, it is believed better to file the paper.28

In time, AGF would recognize the need for men specially trained to handle spare parts. Meanwhile, in April 1943, the War Department approved a company of 6 officers and 176 enlisted men organized into warehouse, procurement, and headquarters platoons.29

Differences of opinion between Hughes and his colleagues in AGF headquarters also arose when it came to the organization of maintenance units under the control of AGF itself. In May 1943, after consulting the Engineer Board and the Maintenance Section, OCE, Hughes submitted a new T/O for the maintenance company which added personnel to distribute spare parts and trucks so that nearly all repairs could be made at the job site. Although the number of enlisted men was raised from 175 to 194, Hughes believed that an over-all saving of 15 percent could be made by having two instead of three maintenance companies for every nine divisions. McNair grumbled that he did “wish that the Corps of Engineers would have a conscience in the matter of vehicles,” but he went along with the T/O “largely because I know too little about the matter.”30 McNair had been led to abandon his opposition to increases in supply units by the illusory prospect, as it turned out, of having fewer total engineer maintenance troops. At this point major opposition to the T/O developed from G-4 of AGF who objected to a supposed duplication of facilities by ordnance maintenance companies, to the concept of sending platoons off on independent operations, and to the fabrication of parts on the site of the construction job. Suggesting that the G-4 concentrate on other matters “rather than hammer at this poor little company,” Hughes jumped to its defense:

Last January, at his [G-4’s] insistence, the general purpose shop truck was removed from the engineer battalion. In other words, the organic means of fabricating local materials for construction was taken away from the combat elements on the theory that it would be more efficiently massed in the maintenance organizations. Now it is insisted that the use of maintenance equipment to augment construction ... is not permissible, as maintenance will suffer thereby. ...

There is a steadfast refusal to understand jobsite maintenance and the necessity to disperse engineers to work. ... Combat troops employed massed and with rapid movement cover wide terrain through which we must keep communications open clear back into the army area, regardless of the space covered or the damage done. ... All construction has indicated that the only economical way to repair heavy plant is to bring the shop and spare parts to the plant. ... only real existing difficulty with the company in the field is that it lacks the means of handling spare parts, ... which the new provides for. Our maintenance in the field is

suffering badly from this deficiency and the blocking we receive from G-4, AGF in organizing both the Equipment and Maintenance Companies is having a detrimental and serious effect on engineer field operations.31

Hughes was right; the Engineers were sorely deficient in maintenance troops. In September, despite continued objections from its G-4, AGF began to process the T/O. In December 1943 it was approved.32

An interesting feature of the War Department’s attempt to divide primary responsibility for service units between AGF and ASF was the complexity it added to the Army’s structure. In place of one equipment company and one depot company the Army ended up with two of each. Hughes persuaded McNair that a new unit was necessary to supply divisional combat battalions with extra construction machinery. In January 1943 AGF began working on a T/O for the unit and six months later received authority to organize a light equipment company. For ASF the Engineers developed the base equipment company to supply operators for heavier and more specialized machinery withdrawn from depots. In the spring of 1943, shortly after AGF became responsible for depot companies, OCE submitted a T/O for a base depot company. As first set up the company could not be readily broken down into smaller units needed for assignment to the many depots in Britain, but in May 1944 changes were made which corrected this defect. In October 1943, meanwhile, the old depot company had been expanded to include a parts supply platoon. Thus after several unhappy months of trying to handle spare parts with men who had no knowledge of the work, AGF had tempered its former hostile attitude toward a special unit, although it still denied the need for an organization as large as a company.33

Changes in ASF Units

Perhaps the most significant difference between the AGF and ASF approach to the organization of troops was that there was no central core or body of doctrine to which ASF units could be tied. AGF had a theory of tactics based on the structure of the division, corps, and army. ASF units had a host of miscellaneous and sometimes unrelated jobs to perform. The main one for the Engineers was construction, but growing out of this general mission was a variety of other tasks which required specialized personnel and equipment in specialized organizations such as the petroleum distribution company, the port construction and repair group, forestry companies, base equipment companies, base depot companies, and heavy shop companies.

The many-sidedness of the ASF engineers’ job can best be seen in the development of T/O 5-500. Before Pearl Harbor, maintenance of searchlights was the only engineer task which called for a small independent unit. Shortly after the outbreak of war a demand developed for sundry others. Requests for utilities personnel came in from the Caribbean, Iceland, and the Middle East where the Engineers were expected to take over the operation of utilities plants from civilians and from Quartermaster units. The first contingents were organized according

to the demands for each particular job, but in April 1943 the War Department published a T/O for utilities detachments for establishments varying in size from 1,000 to 4,000 men. Meanwhile, in June 1942 the Engineers were asked to form gas generating units to operate and maintain plants producing, oxygen, acetylene, and nitrogen. A month later OPD authorized the Engineers to activate firefighting detachments. When the water supply battalion was converted to a company, its well drilling section was left to ASF.34

With this increasing diversity in tasks requiring small teams or detachments the War Department decided late in the spring of 1943 to organize “flexible ‘cell type’ T/O’s ... within which teams or units of skilled specialists can be provided—in varying strengths—to satisfy special requirements.”35 Col. Herbert B. Loper, wartime chief of OCE’s Intelligence Branch, was eager to see the innovation applied to topographic units. “We have concluded here,” he wrote the Chief Engineer of the Southwest Pacific Area in July 1943, “that the ... battalions seldom meet actual theater requirements. Accordingly, we have devised a number of typical reinforcements on the cellular basis, and have submitted Tables for W.D. approval. Further, we have submitted our recommendation to the effect that the major part of the topo troop augmentation to correspond with the new troop basis shall be made up of these independent reinforcing units, rather than of complete battalions.”36

T/O 5-500, published in July 1943, carried columns labeled platoon headquarters, battalion headquarters, mess team, supply team, map depot detachment, utilities detachment, fire fighting section, well drilling section, mobile searchlight maintenance section, dump truck section, and others. In a few cases there were several different teams of the same type. If a theater had requirements which standard engineer organizations could not fill because they were either too large or too small or because they lacked the specialists and equipment, the theater commander could use these cellular units to form platoons, companies, or battalions, using whatever combinations he deemed necessary either to supplement a standard organization or to form a service unit for a base installation. The cellular idea caught on quickly. The 26 July 1944 revision of T/O 5-500 was divided into eight categories—administrative, supply, water supply and transportation, maintenance and special equipment, utilities, firefighting, topographic, and marine. The published document was seventy-eight pages long and—most remarkable of all—contained an index.37

Akin to the cellular idea was the group concept which AGF had applied to the

engineers in the combat zone. The War Department tried to apply this principle to ASF engineers as well. As outlined above, the Engineers had themselves proposed a depot group headquarters to which various companies might be attached, but most of the demand for group organization came from higher echelons and was resisted by the Engineers. The War Department insisted on its use in the case of port reconstruction and repair.38

Still more irritating to the Engineers was the attempt to organize general construction units on a group basis. It will be recalled that the War Department had agreed to begin conversion of separate battalions to general service regiments in January 1943 and that the general service regiment became solely an Army Service Forces unit.39 Shortly thereafter, on the 12th of that month, the War Department directed ASF to review all T/O’s with the group concept in mind and suggested that general service regiments might be reorganized as battalions. A week later the War Department directed ASF not to convert separate battalions to general service regiments but to consider retaining them as labor units or organizing them as general service battalions. Sturdevant objected to the retention of labor units in the face of demands from the theaters for highly skilled troops equipped with construction machinery and argued that the Quartermaster Corps and the Transportation Corps were the proper sources of laborers at depots and ports. He further questioned whether the substitution of the group organization for the general service regiment would save manpower or be as efficient as was claimed. ASF supported the Engineers in opposition to labor units but directed more study of the battalion-group organization.40

In March OCE submitted T/O’s for both a battalion-group setup and a general service regiment with 145 fewer men. Over Sturdevant’s continuing objections ASF decided that the service group would supersede the general service regiment. On 1 May Sturdevant asked for a reconsideration and launched an all-out assault on the battalion-group idea. Let ASF cite an example to prove the battalion-group adopted by AGF was superior to the regimental organization, he challenged. Granted it might be suitable for the control of small units such as equipment, maintenance, and depot companies, where was the desired saving in overhead? He pointed out that the group commander seemed to duplicate the functions of the corps commander who had to rely on the group for all his information. ASF was fooling itself: “The gain in flexibility resulting from the formation of Corps Combat Battalions is believed more theoretical than real since, if additional battalions are to be attached to divisions, they could be detached from a regiment as well as a Group.” If attachment was normal then the divisional engineer element was too small. “On the whole the present Ground Force organization is considered cumbersome, wasteful and probably unworkable. It is anticipated that it will not be retained by Theaters involved in combat,” Sturdevant went on. Grouping might conceivably work in the combat zone where there would be little

construction anyway. But the group-battalion system had no place in the communications zone where large-scale construction projects were the rule and changes in location infrequent.41

A few days after receiving Sturdevant’s communication ASF changed its mind. After all, a reduction of 145 men in the general service regiment would satisfy the demand for economy even better than the group-battalion. AGF did not give in so easily. Although conceding that the regimental organization was generally acceptable for operations in the communications zone, AGF pointed out that some of these units might have to move into the combat zone. It would be better therefore to have the regiments broken up into independent battalions, paralleling the organization of the engineer combat battalions with which they would work. Both types of units would operate best under a flexible grouping. The large number of engineer units required by the modern army might lead to the organization of brigades to command engineer groups, AGF held, but it would be ridiculous to provide a brigade setup for two or three regiments. AGF’s arguments failed to convince the General Staff. The general service regiment was retained.

To complicate the situation, early in 1943 the Engineers became alarmed over the Navy’s aggressive policy of recruiting skilled men for numerous construction battalions, commonly known as Seabees. The Corps of Engineers was sufficiently practical to realize that the best way to prevent the Navy from encroaching upon engineer construction functions was to be prepared to do as much work as possible. Early in 1943 Reybold asked that a total of thirty additional construction units be activated that year and that he be authorized to recruit experienced construction men to fill them. ASF refused to authorize additional units at that time but in March the Joint Army and Navy Personnel Board permitted the Engineers to begin recruiting 9,000 construction workers a month. The Navy was allowed a similar quota.42

Still, the Engineers found themselves at a disadvantage because the Seabee units contained higher grades and ratings than those in Army engineer units. In an effort to establish themselves on an equal plane with the Navy the Engineers sought permission to organize a construction regiment containing higher ratings. This unit would replace the special service regiment and the white general service regiment. The Negro general service regiment was to be retained for reinforcing construction regiments on heavy routine jobs such as roads or airfields. The construction regiment was to be used on more complicated jobs.

With this seemingly mild proposal, the Engineers had in fact stirred up a hornet’s nest. The Operations Division, General Staff, questioned the need for such a unit, much less the need for one with such attractive ratings. The general service regiments were doing a good job overseas. Under the new joint procedure for procurement of personnel the Army was receiving from four to five thousand skilled workers a month and the Engineers should have no trouble getting their share. Noting that nearly all engineer units contained some skilled construction

men, OPD balked at singling out one unit for higher ratings. The initial reaction to such a step would be a lowering of morale followed, in all probability, by efforts to transfer to the unit with higher ratings. The ultimate result would be an upward revision of all ratings.43

At the beginning of July representatives of OPD, G-1, G-3, and G-4 decided to defer approval of the construction regiment pending consideration of a flexible cell-type unit. G-3 passed this suggestion on to ASF in the form of a directive to include in T/O 5-500 “a section or sections of specialized construction personnel ... capable of organization into small groupments or companies to work with General Service Regiments or other units which are primarily labor.”44

The General Staff’s solution found little favor with either ASF or the Corps of Engineers. Brig. Gen. Frank A. Heileman, Deputy Director of Operations, ASF, and formerly an Engineer officer, was convinced of the need for a unit composed of men experienced in construction. “It appears to me,” he commented in July 1943, “that the plan of the Chief of Engineers to differentiate between a highly trained white regiment, whether it be called a special regiment or a construction regiment, and a lesser trained colored regiment which might be called a general service regiment, is a more efficient setup than the proposed cellular organization.” Just because composite organizations had worked well for small units and installations was no reason to apply the principle universally.45 OCE prepared a T/O for a construction specialist company in conformity with the desires of the General Staff, Reybold at the same time entering a vigorous dissent. The construction regiment desired by the Engineers, he wrote, was not a special purpose unit but a means of inducing better qualified personnel to enlist. The construction company slated for inclusion in T/O 5-500 added 205 officers and men to the basic strength of a regiment. There was no way to tell how many such companies would be needed. The patience of the Chief of Engineers was well-nigh exhausted:

It is the view of this office that all regiments require the skills provided. A contrary view assumes that regiments not so reinforced are classified as “units which are primarily labor.” ... This misconception is apparently basis of the current proposal and is not shared by ... any ... responsible commander in active operations so far as known to this office. Although General Service Regiments have been used as stevedores and for similar labor jobs in emergency, they are not set up for such purposes. ... Speed of requires the use of machinery almost to the exclusion of common labor equipped with hand tools. The demand from theaters is for more and heavier equipment and a larger proportion of skilled construction men for three shift operation by every regiment.

The Engineers held that men in a specialist company should be a permanent part of a construction unit in order to give the commander a better knowledge of their abilities, to insure teamwork, and to avoid the lowered morale that would result from discrepancies in ratings. The specialist company could not be a balanced organization since it was a special group.46

Shortly after receipt of this communication, ASF decided to take matters into its own hands. Up to now, so it seemed to Maj. Maurice L. Hiller, head of the T/O Section of the Troop Units Branch, “the type, size, structural organization and need for highly specialized Engineer units has been ‘buck passed’ back and forth between the Chief of Engineers and the Secretary of War, with the Commanding General, Army Service Forces acting as intermediary.” “The result,” according to Hiller, “is that today we are saddled with an Engineer General Service Regiment that does not have sufficiently high grades to perform its functions; a table of organization for an Engineer Port Construction and Repair Group, and a proposed Engineer Construction Specialist Company ... which we have been directed to prepare to replace the proposed Engineer Construction Regiment.” These did not, to be sure, exhaust the list of construction units. Separate battalions under the control of ASF and engineer aviation battalions under the control of AAF brought the types of construction units to five. Hiller was convinced he had a solution—so convinced in fact that he, an Engineer officer, was “willing to stake both my professional and military reputation” on it, even though it ran counter to the opinion of the Chief of Engineers. Hiller proposed that the five construction units be replaced by an engineer construction group and a separate engineer construction battalion. The group would operate much like the offices of District Engineers in the United States. It would be made up of planners and supervisors, and, in case a definite need existed, of divers and ship salvage crews for port reconstruction. The construction battalion would be modeled on the Seabees.47

Perhaps the most ingenious aspect of Hiller’s plan was to wrap up engineer aviation units in the same package with those construction troops that had given rise to the original discussion. That ASF should have control of construction units in the AAF had been maintained in ASF headquarters for some time. In the Southwest Pacific theater where construction projects threatened to outrun the total supply of engineer troops, it had been found necessary to pool all available manpower. In February 1943 MacArthur’s headquarters denied the Fifth Air Force control of engineer aviation battalions. The theater SOS was made responsible for the disposition of all construction forces on projects in the communications zone. In combat areas, the task force commander had control until conditions became stabilized when control would pass to SOS. In the European Theater of Operations, the SOS had succeeded in the summer of 1942 in borrowing engineer aviation battalions for the construction of airfields in the United Kingdom. The agreement was that they be returned to AAF for a period of training prior to the invasion of the Continent and remain under AAF control thereafter. In North Africa, which was from the outset a “combat” theater, engineer aviation units remained under the control of AAF. Even here, however, the SOS displayed dissatisfaction with this arrangement. When General Styer visited the Mediterranean and European theaters in the summer of 1943 he looked into the matter and found the commanding generals of the SOS as well as the Chief Engineer, ETO, in agreement with him that general service regiments should replace aviation

battalions. The ETO was also suffering from a shortage of construction workers. Only fifteen general service regiments—half the number asked for—were slated to arrive in the theater by the end of August 1943. In June the Chief Engineer, ETO, had asked for as many combat regiments and aviation battalions as he could get. Putting all construction troops into one organization would render the manpower more accessible.48 “General Service Regiments can do everything that Aviation Engineers can do, and perhaps a great deal more,” Styer wrote Somervell from abroad. “General Service Regiments can be attached to the Air Forces whenever necessary, but it is a mistake to make them part of the Air Forces.”49

ASF’s view that general service regiments under ASF control should replace aviation battalions was shared by OCE but encountered stiff opposition from the AAF which insisted that only Air Forces control would permit first priority to be given Air Forces tasks. But Hiller’s plan in respect to aviation battalions appealed to ASF and this together with the rest of his proposal plus a recommendation to convert the base equipment company to a cellular type of unit went up to the General Staff in September.50

The road up through the channels for comment was easier than the road down. While everyone found some merit in the plan, everyone found some aspects of it extremely distasteful. Army Ground Forces applauded the basic idea of reorganizing construction units into a group-battalion system, but frowned upon the application of the cellular idea to construction units. The policy was to reduce the types of units; the cellular organization made for infinite variety. In any case, AGF thought it “desirable in considering subjects of this nature to have available the professional views of the responsible technical agency, in this case, the Chief of Engineers.”51 Army Air Forces echoed AGF views on cellular organization as well as on the failure to consult the Chief of Engineers, and called attention to the lack of supporting evidence from the theaters. Most of all, AAF was adamant about retaining engineer aviation units. Aviation engineers had been shaped for the particular needs of the Air Forces and the magnitude of airdrome construction justified the existence of special units under its control, the AAF maintained. This opposition from AAF and AGF led the General Staff to approve only the replacement of general service regiments, special service regiments, and separate battalions by

the construction group and battalion. The General Staff also agreed to place such teams as marine divers in composite units but did not rescind the port construction and repair group.

In line with ASF’s suggestion to keep the Seabees in mind when drawing up a table for the construction battalion, the Engineers provided higher grades and ratings for foremen and equipment operators, increased the amount and size of power machinery, and added sufficient personnel to provide for two-shift operation. As finally approved, the table of organization called for 29 officers, 2 warrant officers, and 913 enlisted men.52

In January 1944 ASF prepared a memorandum which informed the theaters that the construction battalion was comparable to the engineer aviation battalion in earthmoving capacity and to the Seabees in equipment and grades for skilled personnel. General service regiments, separate battalions, and special service regiments were to be converted to construction battalions on a one-to-one ratio. In a most caustic letter, delivered in person to ASF headquarters, Robins, acting for Reybold, challenged what he termed “several incorrect or inconsistent statements” contained in the memorandum:

“The battalion is comparable ... to the Navy Sea Bee battalion in ... grades for skilled personnel.” The construction battalion cannot be considered comparable in that respect . ... The directive to this office requiring preparation of tables contained the statement that it was desired that grades be comparable, but, in fact, the table submitted carried fewer high grades and final changes by War Department General Staff involved substantial cuts. The statement is in gross error.

The proposal to substitute one construction battalion for one general service regiment is based on no known recommendation of this office. Informal recommendation was made for a conversion ratio of one group of three battalions to two regiments. This would practically absorb all personnel.

The idea expressed ... that excess will be available as a result of this conversion shows complete ignorance of the conditions now existing in the theaters. Almost without exception engineer general service units ... are using equipment from stocks (Class IV) in amounts at least comparable with that included in the new organization. These new tables, in effect, merely establish higher grades and ratings for men now doing the work under inadequate ratings, and authorize, in equipment tables, items now drawn from depot stocks on loan. The idea that the adoption of this unit will increase the capabilities of engineer personnel in active theaters is fallacious.

…

Many General Service Regiments, reinforced with additional heavy equipment, have made notable construction records and are considered equivalent or superior to Navy Construction Battalions for Army work and superior to Aviation Battalions in production capacity. These regiments will not relish a formal statement by the War Department that they are to be reorganized to bring them up to the standard of their competitors. ... importance of unit esprit and morale should be recognized and fostered. The necessity for this invidious comparison is not apparent.

General Service Regiments with authorized equipment only are definitely inferior to CB’s in construction capacity and theater experience has shown that the prescribed equipment of General Service Regiments is inadequate for earth moving and some other jobs. This has been recognized by this office for two years but efforts to improve the situation have frequently met with War Department disapproval. In particular, this office some months ago proposed a Construction Regiment comparable in equipment to the recently approved

Construction Group and much more nearly approaching the CB standard in grades and ratings. This proposal was quickly disapproved but is now approved, in general, under another name apparently on the basis that it would conserve personnel.

This matter emphasizes again that little attention is paid by higher echelons to the advice of the agency best prepared to advise on engineer matters: the Chief of Engineers. It is believed that utilization of such advice will contribute to the war effort.53

Backing up their arguments with facts and figures the Engineers pointed out that in the 913-man construction battalion only 232 men were grade four (sergeant) or better; in the Seabee battalion of 1,081 men, 741 were equal to grade four or better. Conversion on a one-to-one ratio, explained Sturdevant in a follow-up memorandum, would cut construction troops in theaters by one third when the percentage of engineers in the troop basis was already too small and had recently been further reduced by the inactivation of a number of aviation battalions. There was no necessity to require the formation of group headquarters and headquarters companies in the communications zone because in most cases adequate administrative staffs already existed in base, intermediate, and advance sections. Groups should be organized only upon request of the theater. The Engineers’ protest achieved immediate and favorable results. ASF’s controversial memorandum was withdrawn and conversion to new units arranged for on a man-to-man basis.

Meanwhile a new aspect of the problem had arisen. In June 1943 the Engineers had resisted a proposal to convert white general service regiments to Negro. Although the Army as a whole contained approximately 8.6 percent Negro troops the Engineers had 19.3 percent. In their effort to secure technical specialists by voluntary induction the Engineers had been unable to secure even 10 percent who were Negroes. As a result ASF had agreed to amend the troop basis to include an augmentation of six white general service regiments so that volunteer white specialists could be absorbed. The revised troop basis was to provide for a total of 87 regiments, 44 to be white and 43 to be Negro.

Following the decision to do away with the general service regiment, 32 construction battalions—6 white and 26 Negro—were projected in the 1944 troop basis. The Engineers in March declared themselves powerless to fill so many construction battalions with Negroes. They cited a number of arguments. Because the background of Negro soldiers currently being inducted was mainly agricultural they were not qualified to operate all the mechanical equipment. Negroes, it was stated, lacked the sense of responsibility necessary for the care of this equipment. The majority of Negro soldiers were in AGCT Classes IV and V. Great numbers were poorly qualified physically, and with their lack of interest and leadership were making “very undependable soldiers.” Since they proved slow to absorb instruction, their training had to be lengthened from 17 to 27 weeks. The Engineers recommended the troop basis be changed to 20 white units and 12 Negro units. To avoid charges of discrimination, two of the twelve Negro units were to be construction battalions, the rest general service regiments.54

Having received ASF’s assent to the broad outlines of this plan and having learned that the Central Pacific theater

wanted battalions, not regiments, OCE submitted tables for a three-battalion general service regiment consisting of 87 officers and 1,710 enlisted men and a general service battalion of 41 officers and 801 enlisted men. These units were especially designed for Negro personnel who fell into Classes IV and V on the AGCT tests, but the Engineers did not consider them labor units. They still had more construction machinery and higher grades and ratings than the old general service regiment.55

For all the extensive and prolonged discussion over the organization of ASF construction units, the desired simplification was not achieved. In addition to distinctions arising from the differentiation of Negro and white units, the freedom given to overseas commanders in forming and administering their commands helped to defeat the program of organizational experts in the United States. The ETO requested permission to retain the old organization of construction units and the War Department acquiesced. As of 30 June 1945 the following ASF construction units were active:56

| Units | Total | White | Negro |

| Total | 337 | 92 | 174 |

| General service regiments | 79 | 29 | 50 |

| Special service regiments | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Construction battalions | 36 | 33 | 3 |

| General service battalions | 8 | 2 | 6 |

| Separate battalions | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Dump truck companies | 135 | 23 | 112 |

| Petroleum distribution companies | 59 | * | * |

| Port construction and repair groups | 12 | * | * |

* Not available.

Distribution of Engineer Troops

The most notable feature of the reorganization of engineer troops that followed the outbreak of war was its concentration upon construction, supply, and maintenance units. In part this situation resulted from the prewar Army’s preoccupation with the structure and tactics of its fighting elements. But the shift in emphasis resulted equally as much from the added importance of logistics in global warfare. The Army could not concentrate as many men in divisional units as it had originally intended.

It became necessary to expand the proportion of service troops because of the Army’s motorization and mechanization, its reliance on air power, and its use of power machinery—all of which required extensive maintenance and supply operations. More important for the Corps of Engineers was the fact that the United States fought with greatly extended lines of communication at the ends of which facilities had to be built in order that men and matériel could be massed preparatory to battle. In June 1945 approximately 40 percent of the Engineer officers and enlisted men mobilized in troop units were serving with AGF, another 40 percent with ASF, and the remaining 20 percent with AAF. (Table 10)

The distinctions between AGF, ASF, and AAF engineers more or less broke down in the theaters. Whatever troops were available were used for the work to be done. It seemed to the Engineers, as it probably did to all arms and services, that they needed more men. In terms of function, front-line engineers had to clear and construct obstacles, lay mine fields, ferry troops in river crossings, build bridges and, as the necessity arose, act as infantry. Those in the rear were more concerned with building shelters, roads, ports, or airfields and with

Table 10—Number and Strength of Engineer Table of Organization Units: 30 June 1945*

| Type of Unit | Number | Strength |

| Total | 2,126 | 596,567 |

| Ground Force type—total | 805 | 253,966 |

| Divisional—Total | 89 | 56,357† |

| Infantry division combat battalions | 66 | 42,042† |

| Mountain division combat battalions | 1 | 807† |

| Cavalry division engineer squadrons | 1 | 674† |

| Armored division engineer battalions | 16 | 10,784† |

| Airborne division engineer battalions | 5 | 2,050† |

| Non-divisional | 716 | 197,609 |

| Combat battalions | 204 | 127,270 |

| Heavy ponton battalions | 15 | 5,652 |

| Combat companies (separate) | 7 | 1,129 |

| Depot companies | 54 | 10,599 |

| Light equipment companies | 38 | 4,567 |

| Light ponton companies | 44 | 9,027 |

| Maintenance companies | 83 | 15,334 |

| Treadway bridge companies | 33 | 4,446 |

| Other engineer ground force type | 238 | 19,585 |

| Service Force type total | 1,060 | 236,400 |

| Port construction and repair headquarters companies | 12 | 3,026 |

| Special brigades | 3 | 17,927 |

| General service regiments | 79 | 94,429 |

| Special service regiments | 5 | 6,405 |

| Construction battalions | 36 | 29,539 |

| General service battalions (separate) | 8 | 5,283 |

| Special shop battalions | 4 | 3,435 |

| Base depot companies | 24 | 3,786 |

| Base equipment companies | 31 | 5,195 |

| Dump truck companies | 135 | 14,200 |

| Forestry companies | 23 | 2,505 |

| Heavy shop companies | 27 | 4,422 |

| Parts supply companies | 16 | 2,763 |

| Petroleum distribution companies | 59 | 12,323 |

| Firefighting platoons | 92 | 2,547 |

| Utility detachments | 85 | 3,857 |

| Other engineer service force type | 421 | 24,758 |

| Air Force type total | 261 | 106,201 |

| Engineer aviation regiments | 11 | 4,568 |

| Engineer aviation battalions | 124 | 88,555 |

| Engineer aviation camouflage, topographic and utilities battalions | 6 | 2,444 |

| Other engineer air force type | 120 | 10,634 |

* Excludes engineers with all communications zone and zone of interior overhead, such as European theater headquarters, service command station complement, replacement training centers, and schools.

† Strength allowed by War Department actions as shown in 1 July 1945 War Department Troop Basis, published by Strength Accounting and Reporting Office, Office, Chief of Staff, U. S. Army.

Source: Statistics, Trp Units Sec, U. S. Army in World War II. MS in OCMH.

performing supply functions. The important fact here is that the engineers were needed both in forward and in rear areas. Wherever they found themselves, however, their most important job was the logistical task of construction –whether of roads or bridges under small arms fire or of hospitals and airfields under the threat of bombing. The great bulk of engineer troops was concentrated in a few large units which were capable of undertaking such construction projects. By June 1945, 89 divisional combat battalions, 204 nondivisional combat battalions, 124 aviation battalions, 79 general service regiments, and 36 construction battalions had been mobilized. Although the idea persisted in certain segments of the Army that the Engineers could absorb a

large number of unskilled labor troops, the Engineers had in fact become more and more dependent on skilled and semiskilled men. The Army would have needed many more such units had the engineers been merely labor troops. Under the conditions of modern war the Engineers relied increasingly on machine power and the trend was toward more and heavier machinery. The demands of global warfare made the Corps of Engineers in World War II a corps of specialists.