Chapter 13: Toward a Four-Million-Man Army

Events of 1941 changed the preparedness goal from defense to victory. Japan’s encroachment into Southeast Asia, the German invasion of Russia, and the sinkings of American ships in the Atlantic increased the likelihood that the United States would enter the conflict. Lend-lease, the freezing of Axis assets in this country, the embargo on shipments of oil to Japan, and the decision to use American warships to escort British merchant convoys were milestones on the road to war. The Munitions Program of 30 June 1940, which contemplated a mobilization force of 4 million men by the spring of 1942, had primarily a protective purpose—hemisphere defense. The Victory Program of 11 September 1941, which envisaged an ultimate force of nearly 9 million, had another end in view—“to defeat our potential enemies.”1 As the crisis deepened, as sterner tasks impended, the Army struggled toward its mobilization goal, a goal it had to attain before it could pursue the larger war objective.

Once again construction set the pace. A 4-million-man army would require many new facilities—a second wave of munitions plants, more training camps, more airfields, and more schools and hospitals. Because the President, in order to affix a bargain price tag to the 1940 program, had deferred most such projects, warehousing, depots, docks, and wharves carried a high priority. Still other requirements—not the least of which was additional office space for the War Department—were evident. Although the Corps of Engineers carried part of the burden, the Construction Division continued to do the bulk of the work. Quartermaster officers played leading roles in launching the new program and charting its course.

Budgetary Politics

The program took shape slowly. In his annual budget message on 3 January 1941, the President spoke of “carrying out the mandate of the people ... for the total defense of our democracy.”2 Yet the construction funds he requested for the new fiscal year were relatively meager: $160 million for military posts; $95 million for maintenance and repair; $5 million for hospitals; and $118 million for seacoast defenses, of which possibly one-third would go to the Engineers for fortifications. The President also put in for $500 million to expedite production, but $300 million of this amount would go to liquidate contract authorizations carried over from the previous fiscal year.

The low total for construction was in part due to the Bureau of the Budget, which continued to slash War Department requests, and, in part, to the public expectation that National Guardsmen and selectees would begin going home in the fall.3

To obtain large additional sums would require adroit strategy. General Gregory got things moving. Since the fall of 1940 he had pressed for a start on the $200-million ports and storage program deferred by the President. Gregory remembered his experience in World War I as a Quartermaster officer at Jeffersonville Depot. “We had thousands of tons of supplies,” he recalled, “right out in the open in the corn field, where to get to them with trucks, you had to go through mud. I determined that we would never face that if I ever had anything to do with another war.”4 In 1940 he was particularly concerned about the lack of facilities along the Pacific coast, and late in October he sent Groves west to size up the situation. The outlook was not encouraging. At the Oakland Port and General Depot the only room for expansion was an area of formerly submerged tideland filled with bay mud; to provide firm ground, it would be necessary to do hydraulic filling and to truck dirt from the surrounding hills. Oakland was but one of many big and difficult future projects.5 Sensing that speed was imperative, Gregory kept after Marshall. “The General Staff,” he afterward complained, “was very slow in recognizing the necessity for additional depots and port facilities.”6 He doggedly persisted. In mid-January 1941, when he learned that the War Department would request a fifth supplemental appropriation for 1941, he promptly asked for $175 million.7

On 25 February, just before Gregory’s estimate went to the Bureau of the Budget, Leavey telephoned Groves: “We have a chance, I think, of getting some supplemental estimates tacked onto a bill being rushed up to Congress and if you have any items you think have to be put in –– .” “Fifty million,” Groves interjected. He was thinking of contingencies, of needed repairs, of a lumber stockpile, of unfinished work at almost every camp. Leavey hesitated—then agreed: “It may get kicked out, but we can try it.”8 Try they did, but with little success. The Budget estimate sent to Congress gave the Construction Division $ 115 million for ports and storage, $15 million for a lumber stockpile, and not one cent for anything else.9

At House hearings on the fifth supplemental early in March, Somervell kicked over the traces. Defying the unwritten law that bound officers to uphold administration measures, he termed the current estimate for storage mere guesswork—a figure “just pulled out of the air” and “not fastened to the ground in any way.” He recalled the deficit for

camp construction, a sore point with some Congressmen, and predicted that a second overrun would follow the granting of the present low request. Testifying before the Senate subcommittee on 27 March, he brought up the matter of a contingency fund. Defining a contingency as “something that a man could not think of in the first place,” he told one Senator, “There may be some people who are smart enough to think of everything. They just might exist. ... They are not in the Army, anyway.” When Somervell finished, the legislators were calling for “a statement showing just what it is going to cost.” Not yet ready to make such a statement, Somervell promised to come back. “And when I come back,” he said, “I will come back with definite figures.”10

The new appropriation act approved on 5 April provided for a good deal of construction but signaled no real breakthrough. For military posts, ports, and depots, there was $304,821,000; for maintenance and repairs, $2,366,000; for sea-coast fortifications, $3,536,000; and for expediting industrial production, $867,286,000. There was also $98,250,000 for airfield construction tacked onto the bill at the President’s request. Welcome though it was, the act was hardly more than an accommodation. Of the construction total, half was in contract authorizations. Moreover, many of the items in the bill had merely advanced from the regular appropriation for 1942.11

With passage of this act, Congress completed the round of military appropriations for the fiscal year. Since June 1940, more than $2.3 billion for construction, maintenance, and real estate had become available to the Quartermaster Corps—part by direct appropriation and part by transfer from other agencies. Roughly half a billion of this sum had gone to the Engineers for Air Corps projects. The balance, $1.8 billion, was approximately three times the total expended by the Construction Division from 1921 to 1940. Although the division had let contracts and spent money with record speed during eleven months of defense construction, on 31 May 1941 some $382 million—most of it from appropriations voted in March and April—was still unobligated.12

On orders from the President, Patterson early in June directed General Gregory to obligate these funds before the month was out. On the 5th Colonel Leavey wired the zones to advertise at once. Two days later Groves, who had not seen the telegram before it went out, wrote an “amplifying letter,” instructing the field to negotiate if plans and specifications were incomplete or if bids were excessive.13 Meantime, in Washington, the Contract Board under Chairman Loving set to work. They cut the advertising period to five days and wrapped up negotiations rather quickly. In some cases they went to letter contracts—preliminary agreements which sealed bargains in advance of formal contract signings. CQMs started many projects by purchase and hire. Haste had its usual

effect. “The contractors are in,” Colonel Alfonte telephoned Groves from Fort Benning, “and they say they haven’t got time to figure the things, and they are adding a hell of an ante on it.” There was nothing Groves could do. “I’m very much disturbed about ... the mad rush,” he told Alfonte, “but it was ordered from the White House and that ends it.”14 By dint of long hours and hard work, the Loving board and the zones completed the job, 100 percent, by 30 June. Among the projects gotten under way were ordnance depots, storage depots, port facilities, and hundreds of new buildings—chapels, service clubs, theaters, motor repair shops, radio shelters, and warehouses—at dozens of existing stations.15 Early in July Somervell commended his organization for giving him “results, not alibis.”16 The President expressed his satisfaction but kept the pressure on, indicating that he wished to see the funds for the new fiscal year obligated in the same manner and with the same speed.17

If haste was becoming more imperative, the Bureau of the Budget took scant notice of the fact. Presented with the revised construction estimates for 1942, it performed the usual thoroughgoing surgery. Where Somervell asked $5 per square foot for storage, it gave him $4. Where he asked for 17,000 maintenance men, it gave him 12,000. Where he recommended a maintenance fund amounting to 5 percent of the total property investment, it approved a sum equivalent to 2.5 percent. The request for a contingency fund met another rebuff. Even more discouraging was the outlook for new projects. With reductions in the strength of the Army slated for the fall of 1941, there could be no request for more troop shelter. What was worse, the Budget made no provision for additional munitions plants. The estimate included approximately $391 million in expediting production funds, but this entire amount was for payment of contracts authorized for 1941.18

Somervell. decided to fight for larger appropriations. Complaining that his organization was “behind the eight ball,” he set himself for a difficult bank shot.19 He prepared to get around the Budget by appealing directly to Congress. As the date of the hearings drew near, arguments were tested and witnesses were rehearsed. On 6 May 1941, the day before the House subcommittee took up the Quartermaster estimates, Groves told a member of G-4: “The big mistake is to be too modest. ... I’m in favor of asking for a lot and letting them turn you down if they have the nerve—they won’t have the nerve.”20 Early next morning the officers who would testify

met in Somervell’s office to “go over the thing” one last time, before starting out for the Capitol.21

Everything went as planned. Setting the tone for the hearing, Chairman J. Buell Snyder began: “We are very glad indeed, General Somervell, that you are here ... and we want you to know that you are welcome and that we wish to cooperate with you and help you in any way that we can.” Other members of the subcommittee affirmed their confidence in Somervell and praised his organization. Abetted by friendly questioners, the witnesses demolished the Budget’s position. They explained that men who were ignorant of construction had slashed their estimates. They demonstrated the need for larger sums than those the Budget had requested. They predicted overruns, delays, and increased costs if the Budget’s policies prevailed. Their testimony had the desired effect. Stating that he was “getting tired of seeing deficiencies,” Representative D. Lane Powers told Somervell: “I think our committee should take into consideration what you think is necessary ... and not what the Budget arbitrarily gives you, not having technical knowledge as to a matter of this sort.” Mr. Snyder observed that the Budget’s recommendations were “merely advisory.” Representative Joe Starnes proposed to obviate the need for a deficiency appropriation by voting enough money in the first place.22 The Construction Division had won its case. Back at his desk, Groves exulted: “They’ll give us anything we ask for.”23

And they did. Satisfied that the Budget estimates were inadequate, the House group urged the Army to state how much it really needed. “If the Budget has anything to say about it,” Snyder told General Moore, “you refer them to us.” Somervell was free to present his own figures to Congress, and on 20 May he went back to ask the House subcommittee for $157 million in addition to the $280 million originally approved by the Budget. His estimate provided an extra dollar per square foot for storage, an adequate maintenance fund, money for deferred buildings, sums for additional depots and additional tracts of land, and a $25-million contingency fund. Thanks largely to Major Boeckh, Somervell was able to present his estimates as “scientific.”24 The House accepted them as such and its bill granted all Somervell’s requests.

Somervell could not request funds for new munitions plants: that was up to the Under Secretary. But, though the Budget estimate for expediting production was woefully inadequate (the sum requested would do no more than liquidate half the unpaid contract authorizations carried over from 1941), Patterson did not appeal to the House subcommittee. Instead he sought $500 million for the second-wave munitions plants from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. At a meeting on 9 June in the office of Commerce Secretary Jesse Jones,

discussion centered on the possibility of a loan. Among those present were General Burns, representing Patterson, General Harris, representing Ordnance, and Colonels Styer and Jones of the Construction Division. Secretary Jones agreed to advance the money but only on condition that the Defense Plant Corporation (DPC), an RFC subsidiary, do the construction. The Army men accepted the loan on the Secretary’s terms.25 The next day Leavey’s executive officer, Colonel Covell, informed Casey: “A decision was reached yesterday with the RFC through its Defense Plants Corporation that they would construct the new Ordnance manufacturing plants. ...

This means that these projects will be handled entirely between the Ordnance Department and the Defense Plants Corporation and that this Division will have no part in their construction.”26

Neither Somervell nor Campbell was willing to accept this decision. Both appealed to Patterson. On 12 June, with the Under Secretary’s permission, Somervell recommended to the Commerce Department that, in “the best interests of the entire defense program,”

DPC put up the money and leave construction to the Construction Division.

“By dint of experience,” he emphasized, “... many of the obstacles which presented themselves during the first program have been overcome and can be avoided in the second if the same organizations and relationships can prevail.”27 When it became apparent that Somervell had failed, Patterson went to Secretary Jones, who agreed to advance half the money if Somervell did the work.

It was not enough. Somervell made a furtive appeal to the Senate subcommittee on military appropriations.28 When Patterson came before this group on 20 June to testify on another matter, Chairman Elmer Thomas urged him to “make any recommendation you see fit, without regard to the budget.” Senators Hayden, Truman, and Chavez also encouraged the Under Secretary to speak up. “So the lid is off,” Thomas declared, “and you can make any recommendation you see fit.” Patterson recommended inclusion in the bill of $500 million for the second-wave plants.29 That afternoon he wrote to Secretary Jones, thanking him for his offer and stating that it seemed probable that the War Department would be able to finance the plants itself.30

For a time it appeared that Somervellian tactics might be the right generalship for obtaining camp and cantonment funds. Testifying off the record before the Senate subcommittee on the morning of 18 June, General Marshall recommended strengthening the army within the continental limits by 100,000 miscellaneous troops and two armored divisions and substantially increasing the garrisons in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Panama. That afternoon, Somervell wrote to General Moore:–

It is essential that this office be given

directives on the increased construction necessary for this work at the earliest practicable date so that proper plans may be prepared leading to adequate estimates for construction. These estimates must be based on plans if the Army is to conform to the promises made to the House Appropriations Committee. It would be extremely unfortunate if the Army had to go back before this Committee and confess another lack of plans on these garrisons. I should like to urge with all the earnestness at my command the necessity for our being given complete orders on these increases if we are not to fall down on the job we are trying to do for you.31

Supporting Somervell, Moore pointed out to Marshall that additional camp construction ought to start soon, “if we expect to avoid the difficulties in winter construction, which caused so much comment this past year.” But an appeal to Congress for camp construction funds would anticipate approval for extending the draft and retaining the National Guard in federal service. Marshall let sleeping dogs lie.32 Although Congress seemed willing to vote whatever sums the Army asked, the Army once again felt constrained to ask for less than it needed. The regular appropriation for 1942, approved on 30 June 1941, granted all requests but contained nothing for additional camps.33

July was a time of fresh beginnings. Among the dozens of projects launched during this first month of the new fiscal year, the most important were eleven second-wave munitions plants and five advance planned camps. The Volunteer Ordnance Works, a $35-million TNT plant at Chattanooga, Tennessee, and a $25-million Chemical Warfare arsenal at Huntsville, Alabama, were the largest industrial undertakings. There were also sizable plants for producing anhydrous ammonia and small arms ammunition and smaller ones for making detonators and ammonium picrate, bagging powder, and loading shells. With the funds recently appropriated for expediting production, industrial construction could proceed full steam ahead. There was no appropriation to implement directives issued by General Marshall early in July for two armored division cantonments, a triangular division camp, a replacement training center, and a barrage balloon training center. This construction had to start on a shoestring—$10 million from the Chief of Staff’s contingency fund. Having a total estimated cost of nearly $73 million, these five projects could not get far unless Congress provided more money.34

The Chief of Staff’s biennial report, published on 3 July 1941, implied that the Army would soon request additional funds for troop housing. Expressing “grave concern” over “the hazards of the present crisis,” General Marshall “urgently recommended that the War Department be given authority to extend the period of service of the selective-service men, the officers of the Reserve Corps, and the units of the National Guard.”35 The widespread opposition to this proposal, the public

controversy it engendered, and the fierce debate it provoked in Congress formed an interesting chapter in the history of this period. Even before the climactic vote of 12 August, when the House agreed by the narrowest of margins to extend the draft, the War Department was proceeding on the assumption that Congress would act in the best interests of national security. During July, it rushed supplemental estimates to the Hill. Included were requests for $84 million for ammunition storage and $90 million for camps and cantonments.36

Thanks largely to Somervell’s initiative, the House Appropriations Committee inserted another construction item in the bill—$35 million for a mammoth new War Department building. Since the start of the defense program, the shortage of office space in Washington had been growing more acute. The government had taken over apartment houses, warehouses, residences, and garages for its expanding forces. By the summer of 1941, 24,000 War Department employees occupied seventeen buildings in the District of Columbia and others in Virginia. Conditions everywhere were crowded, and The Adjutant General’s office had only 45 square feet per person. In May, the Public Buildings Administration had proposed erecting temporary structures for various agencies on the outskirts of the city. The Bureau of the Budget included $6.5 million for this purpose in the estimate submitted to Congress early in July. Somervell had a better idea, a scheme for housing the entire War Department under one roof. He talked to General Moore about it. Then he talked to Representative Woodrum. When the estimate for temporary buildings came before the House committee, the Virginia Congressman proposed that the War Department work out an overall solution to its space problem.37 The result was the Pentagon project, a story in itself.38

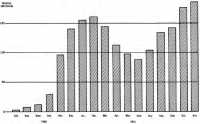

The supplemental appropriation, the last War Department money bill enacted before Pearl Harbor, received Roosevelt’s signature on 25 August 1941. The fight for funds had been partially successful. The Army had asked Congress to underwrite programs to mobilize 1,727,000 men and to provide equipment for a force of 3 million. And Congress had done so.39 But the 4-million-man goal was still inaccessible and the distance to the ultimate victory goal seemed impossibly vast. The War Department could do no more than expedite the work at hand and hope that the Army would be ready when the challenge came. An accelerated construction program lent substance to this hope. Beginning in July 1941 the monthly value of work placed at Quartermaster projects shot upward. (Chart 12) In October, when

Chart 12: Value of work placed by month on Quartermaster Construction Program, 1 July 1940 to 30 November 1941

Source: Constr Div PR 41, 16 Dec 41, p. 29.

Table 12: Summary of quartermaster projects completed and under way, 5 December 1941

| Projects | Completed* | Under Way | Value of Work In Place |

| Total | 375 | 220 | $1,828,268,053 |

| Camps and Cantonments | 61 | 10 | 623,532,764 |

| Reception Centers | 47 | — | 8,640,794 |

| Replacement Tng Centers | 25 | 4 | 110,665,861 |

| Harbor Defenses | 37 | 8 | 26,549,331 |

| Misc Troop Facilities | 113 | 87 | 148,009,863 |

| General Hospitals | 19 | 6 | 24,716,258 |

| Ordnance Plants | 20 | 40 | 663,865,631 |

| Ordnance Ammo Storage Depots | 2 | 7 | 72,859,862 |

| Misc Ordnance Facilities | 6 | 20 | 38,327,548 |

| CWS Plants | 7 | 4 | 26,815,370 |

| Storage Depots (excl. Ammo) | 9 | 23 | 76,512,266 |

| Misc Projects | 29 | 11 | 7,772,505 |

* Includes projects more than 95% completed.

Source : Constr PR 41, 16 Dec 41, pp. 40-43.

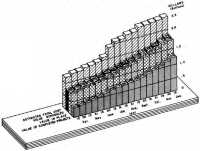

more than 150 million dollars’ worth of construction went into place, Somervell beat his previous record set in February. He set a new high in November, when the total passed the $175-million mark. Although individual projects lagged, the program as a whole went ahead on schedule. (Chart 13) The Quartermaster organization took additions to the work load in stride. For example, the transfer of $18 million from the Federal Works Agency to the Construction Division for 200 USO buildings on 30 September was followed three weeks later by the announcement that 51 buildings had been started. Before the end of November, 191 were under way.40 Of 220 major projects under construction early in December, 52 were more than one-quarter complete, 42 were more than half, and 84 were more than three-quarters.41

In the five months before Pearl Harbor, the Construction Division accomplished a great deal. On 28 June 1941, the Quartermaster program included 100 defense projects complete or essentially complete and 324 under way; the value of work in place was $1,043,737,019.42 On 5 December the number of completed projects stood at 375; the number of going projects, at 220; and the total value of work in place, at $1,828,268,053. (Table 12) Of the 171 projects started during this period, only one was highly exceptional—the Pentagon. Most of the methods and procedures employed were by now familiar. Only in contracting and contract administration were there striking innovations.

Chart 13: Comparison of costs—Quartermaster Construction Program, 1 April to 15 December 1941

Source: Constr Div, PR 41, 16 Dec 41, p. 29.

Contractual Refinements and Reforms

Of all the criticisms directed at Army construction, the harshest and most persistent had to do with contracts. The fixed-fee agreement—the keystone of Hartman’s system and of Somervell’s as well—was a popular target. The general public and the press displayed a deep-rooted prejudice against it. Politicians identified it with high costs, profiteering, favoritism, and collusion. Specialty firms damned it. Equipment renters chafed at recapture. Material-men, forced by the slowness of audit-reimbursement to wait for money due them, voiced bitter complaints. Comptroller General Lindsay C. Warren, seeking to guard against dishonest contracting officers and rapacious contractors, viewed the arrangement with distrust. Some War Department officials believed that the fixed-fee method, if not inherently evil, was impractical for public work. Those responsible for construction had to consider every objection, valid or not.

The most vulnerable part of the fixed-fee system was the audit-reimbursement machinery. At times it hamstrung contractors, at times it led to abuses, and it was nearly always slow. Terming it “the most expensive and progress-impeding feature of a cost-plus-fixed-fee job,” Madigan described how it might work under strict administration:–

After the job has been operating a short time, the contractor is confronted with his first argument with the contracting officer and auditors in charge concerning whether or not a certain expenditure which he may have deemed necessary is reimbursable. His attention is called to the fact that the particular expenditure, which everybody admits was probably necessary, was not authorized and therefore is against the rules and regulations governing the operation of a fixed-fee contract, which states that the contracting officer has to authorize all expenditures. The contractor, therefore, in order to protect his own financial interests insists that every purchase, large or small, must be approved by the contracting officer before the purchase is made by any of his employees.43

Under an easy-going CQM, the story was likely to be different. On a visit to Camp Polk in April 1941, Mitchell discovered that the contractor was paying ten employees yearly salaries of more than $6,000. He cited two cases:–

One employee, bearing the imposing title of “Assistant General Superintendent” is apparently in actuality a chief material clerk, responsible for the receipt, custody, and distribution of materials and equipment. This employee receives $6500 per annum, to which I offer the single comment that “It’s nice work if you can get it.”

Another employee acts as Assistant General Superintendent in charge of operation and maintenance of automotive equipment, again for the sum of $6500 per annum. This figure occurs so frequently that I am beginning to believe it has some mystic significance. This job is purely that of a master mechanic, and again the salary seems to me out of line.

Proposing a full-scale investigation, Mitchell quipped, “When folk go to Polk they should poke around a little mo’.”44 Bottlenecks in field auditors’ offices not only tied up contractors’ funds and forced them to borrow but also worked injustice on suppliers. One lumber dealer, calling his trade with fixed-fee contractors “the most highhanded piece of monkey business I have gotten into in a long time,” wrote to

the Construction Division in the spring of 1941: “By what right or token have you, the contractor, or any other department the privilege of taking my lumber, using it, and not paying when the invoices are due under the terms of sale set up by yourselves? Yes, gentlemen, I am mad and getting madder every day. I want my money.”45 Madigan’s solution to these problems was to scrap the contract. “I question,” he said, “whether the cost-plus-fixed-fee form ..., for which I have the greatest personal respect, is workable on government projects.”46 Unable to dispense with fixed-fee contracts, the Construction Division could only try to increase their workability.

Started during Hartman’s administration, efforts to streamline auditing procedures continued under Somervell.47 In late December 1940, the chief of the Accounts Branch, Colonel Pashley, asked most field auditors to cut their staffs to 20 percent of current size, which would leave the government with one timekeeper or materials checker for every five on contractors’ staffs.48 When Constructing Quartermasters tried “to stick to that 20 percent right down to the gnats’ eyebrow,” he told the field to go as high as 30 percent but to get away from “absolute duplication.”49

Meanwhile, he continued testing the method used in World War I. At Camp Meade and at the Ravenna Ordnance Plant field auditors took over all timekeeping and inspection work from contractors. At Edgewood Arsenal the government took over the contractor’s payroll as well. Pashley believed that time would tell which of the two methods produced better results.50 Meanwhile, Pashley endeavored to strengthen the field organization. He began in December to form an auditors pool but made slow progress. Somervell complained that the auditing force was “not being built up and overhauled ... with anything like the speed which should be secured.”51 Moreover, he insisted that Pashley make doubly sure of the honesty of every field auditor. “Integrity,” Somervell sermonized, “is what has made the Corps of Engineers successful in its affairs and the record made in this present construction program in the Quartermaster Corps must be equally outstanding in this respect.” Any malfeasance would bring “prompt and ruthless action.”52 Firing people was one thing; replacing them was another. Pashley’s efforts to recruit auditors continued to have limited success. Some of the men he persuaded to take jobs in the field left after a short time. “Personality upsets and dislike of military type direction by higher grade civilians” lay behind many resignations.53 Even with the odds against him, Pashley kept trying. By April he had secured enough auditors to keep abreast of the

job, though some positions were still vacant. Schemes to offer larger salaries and to set up a school for auditors and accountants held some hope for the future, but as long as the nationwide shortage of professionally trained men continued, Pashley could expect to have fewer than he needed.54

Colonel Pashley had no say in choosing a new auditing procedure. Early in March Judge Patterson brought in Arthur H. Carter, senior partner of Haskins and Sells of New York City, one of the country’s top accounting firms, to review the fixed-fee audit system.55 military background (a West Point education and over ten years’ service as a Coast Artillery officer) enhanced Carter’s qualifications for the job. After visiting a number of construction projects, Carter on 29 April recommended that the War Department assume “responsibility in the first instance for certain functions now administered by contractors and, to a great extent, duplicated by Government auditors.” He suggested that field auditors take over all the work of checking time, preparing payrolls, inspecting materials, and auditing vendors’ invoices.56 He thus set his seal of approval on the procedure used in World War I.

When General Schulz forwarded Carter’s report to the Accounts Branch, Pashley turned it over to his deputy, Oliver A. Gottschalk, recently of the New York WPA, and to Thomas A. Pace, head of the Accounting and Auditing Section. Gottschalk in a favorable report maintained that Carter’s method offered greater initial protection to the government and speedier reimbursement to the contractor. Pace, reacting adversely, pointed out that the proposed procedure did not constitute an audit, since it provided no check of original records. He argued that changing the setup at going projects would save little or no money and emphasized the advantages of having contractors keep their own records. Besides, he held, big corporations like DuPont would probably refuse to turn their bookkeeping over to the government. Colonel Pashley, agreeing with Pace, recommended that the Construction Division oppose the change. General Somervell sided with Gottschalk. On 15 May Patterson adopted Carter’s system. The task of instituting the new procedure fell to Gottschalk, who succeeded Pashley as chief of the Accounts Branch in mid-May.57

Because Constructing Quartermasters no longer checked contractors’ books but compiled the original records themselves, there was a need for some sort of supervision. Patterson therefore directed Gregory to establish a force of supervisory auditors, who would be independent of the project offices. This force was to see that auditing procedures adequately protected the government,

that field auditors’ offices were properly organized and capably staffed, that there was no unnecessary duplication, and that the Quartermaster organization caused no delays in reimbursement. The Under Secretary’s directive was easy to carry out. In the zone Accounts Branches, Somervell had a ready-made supervisory force. The transition to the new system went forward with little disruption to the work. At new projects and at older jobs where the Constructing Quartermaster and the contractor were able to reach an agreement, field auditors, working under the watchful eyes of the zones, now performed an important management function, the keeping of original accounts.58

Although, as Pashley had predicted, some contractors balked at letting the government keep their records,59 the new system enjoyed wide use, and most rated it a success. To be sure, Comptroller General Warren looked with some disfavor upon a system which, strictly speaking, was not an audit, but others praised the system highly.60 Patterson was enthusiastic. On 25 August he advised Secretary of Labor Perkins: “It is estimated that since this procedure was put into effect on June 7, 1941, it has resulted in a saving of approximately $15,000,000.”61 Such news was welcome in Congress, where the Thomason committee commended Carter for eliminating duplication, increasing efficiency, and saving money.62

The War Department Insurance Rating Plan made possible further economies. Patterson took the first step toward developing this plan early in January, when he appointed a board of experts to review the insurance provisions of the fixed-fee contract. Somervell gave the project his full support.63 “This move should not be allowed to die of inanition,” he told Leavey and ordered him to “follow through.”64 How far Somervell influenced the board’s findings was hard to tell, but his enthusiasm for its work was unmistakable. The plan adopted on 3 May was a boon to the Construction Division. Under it the government obtained reduced rates from insurance carriers. Fixed-fee constructors, architect-engineers, and subcontractors whose premiums totaled $5,000 or more could insure at these reduced rates or “self-insure ... in a manner satisfactory to the War Department.” Contractors paying less than $5,000 in premiums had to obtain competitive bids on insurance rates.65 Six months after the introduction of the plan, Somervell

reported that insurance costs on fixed-fee jobs had dropped 20 percent.66

Much of the controversy over emergency contracts revolved around fees. By comparing defense profits with previous earnings by the same firms, the Truman committee attempted to prove that fees were unconscionably high. An analysis of constructors’ fees at twenty-two camps showed profits averaging more than 450 percent of the contractors’ mean annual earnings for 1936 through 1939. A check of twenty-five architect-engineers showed an average increase of more than 300 percent over peacetime profits. Rare instances of contractors whose income had jumped 1,600 and 1,700 percent strengthened the impression that the Army was playing Santa Claus to the building industry.67 Somervell believed such comparisons were unfair. Appearing before the committee on 25 April, he emphasized that the construction industry had just emerged from a severe depression and that most defense projects were larger and more difficult than the jobs previously handled by the same firms. In his opinion the fees originally set by Hartman and Loving were “about right.”68

By early 1941, new fee schedules were already under consideration. Colonel Jones and his staff in the Legal and Contracting Section had begun in January to study the possibility of using the old ANMB schedule not as a minimum curve for constructors’ fees, as Hartman had done, but as a maximum. Similar investigations were soon under way in Patterson’s office.69 The ANMB’s Hogan committee took a dim view of these proceedings, asserting that fees were “already too low.”70 Industry agreed. A prominent constructor, one of a number who protested, told Patterson that “the fees proposed would be much too low, unless the contractor is to act as a mere broker and sublet everything, and if that is contemplated why have any contractor?”71 But protests were unavailing.

In June 1941, Patterson, with the advice of Madigan, Harrison, and a board of distinguished officers and civilians headed by General Robins, revised the fee schedules for both constructors and architect-engineers. (Table 13) The new scales were markedly lower. Where the War Department had previously paid at least $300,000 for a $10,000,000 construction job, it would now pay at most $250,000. Where the old schedule for architect-engineers had listed $48,000 as the average fee for a $5,000,000 project, the new one set $45,000 as the top figure. The industry, which was witnessing a marked decrease in public works construction, accepted the reduced rates, though not without grumbling. Appearing before the Truman committee on 15 July Patterson pointed out that fees on construction contracts had so far averaged 3.3 percent and those on architect-engineer contracts I percent of original estimated costs—well below the limit set by Congress. New schedules,

Table 13: Revised Schedule of Fees for Architect-Engineer and Construction Services, 23 June 1941

| Estimated Cost of Construction Work | Maximum Fixed Fee for Architect-Engineer Services | Fixed Fee for Construction Services |

| $ 100,000 | $ 4,000 | $ 6,000 |

| 500,000 | 12,500 | 17,778 |

| 1,000,000 | 20,000 | 32,500 |

| 5,000,000 | 45,000 | 130,000 |

| 10,000,000 | 75,000 | 250,000 |

| 25,000,000 | 165,000 | 500,000 |

| 40,000,000 | 246,000 | 700,000 |

| 50,000,000 | 300,000 | 800,000 |

| 65,000,000 | 360,000 | 905,000 |

| 75,000,000 | 400,000 | 950,000 |

| 80,000,000 | 420,000 | 970,000 |

| 85,000,000 | 440,000 | 980,000 |

| 95,000,000 | 480,000 | 995,000 |

| 100,000,000 | 500,000 | 1,000,000 |

Source: Memo, Dir P&C, OUSW, for TQMG, 23 Jun 41. OCE Legal Div Lib, Instructions re FF Contracts, Bk I.

he assured the Senators, would reduce fees even further.72

At the same time that he adopted lower schedules of fees, Patterson approved a revised version of the fixed-fee construction contract. Although most of the changes were minor ones, two new clauses were of major importance. The first gave the contracting officer the right “to decide which functions of checking and auditing are to be performed exclusively by the Government and to prescribe procedures to be followed by the Constructor in such accounting, checking, and auditing functions as he may continue to perform.” The second, the so-called 25-percent clause, attempted to set a standard for defining a material change and thus for deciding when a fee adjustment was in order. The clause ruled out any change unless there was a net increase or decrease of 25 percent in the number of “units” covered by the contract. Adjustment would take place at the time of final settlement and would turn upon the number of units “exceeding the said 25 percent.”73 If, for example, the original contract called for 400,000 square feet of storage space and the government ordered 100,000 more, the contractor would not receive a higher fee. But, if change orders brought the total to 650,000, he could claim an additional fee based on 150,000 square feet. Complicated and cumbersome, and designed

primarily for storage and housing projects, the 25-percent clause eventually fell by the way. Nevertheless, after June 1941 the Construction Division generally defined a material change as one involving roughly 25 percent of the scope of the original contract.74 Although the revised agreement alleviated some of the administrative difficulties connected with fixed-fee work, it failed to satisfy fixed-fee critics.

Among the most determined foes of the Army’s fixed-fee system were specialty contractors. Dissatisfied with the amount of work that came their way during the early months of defense construction, the specialty groups renewed their demand for a contractual clause forcing fixed-fee contractors to sublet mechanical items. Attorney O. R. McGuire, representing a number of specialty associations, hurled a barrage of protests at the War Department. His clients reinforced this opposition by invoking restrictive agreements with unions and suppliers to put the screws on contractors.75

Even in the face of these tactics, the War Department refused to alter its policy of leaving the decision when to subcontract up to principal contractors. Writing to McGuire in April 1941, Secretary Stimson summed up his position:–

It is not in conformity with public policy or in the interest of national defense to prevent a substantial general contractor from undertaking to do an entire job himself in any manner he sees fit; and besides, ... any effort to restrict a contractor in this respect would throw an unwarranted burden upon the appropriations involved by preventing ... a substantial saving through the elimination of a portion of the subcontractors’ profits from the cost of the work.76

Somervell scoffed at the subcontractors’ complaints, maintaining that the protesting associations were in fact performing “a very large portion” of construction.77

The specialty associations refused to take “no” for an answer. On 1 May 1941, they asked Congress to require the subletting of all specialty work. General Somervell hastened to point out the disadvantages of such legislation:– first, it would give principal contractors no alternative but to accept unreasonable bids for mechanical items; second, it would in the form presented give specialty firms control of items for which their finances, equipment, and organizations were inadequate; third, it would increase the need for skilled mechanics and possibly result in demands for higher wages.78 “Considered from any angle,” Somervell told Congressman May, “this amendment will result in increased cost, delay in time of completion, and confusion due to lack of coordination and divided responsibilities.”79

Although the specialty contractors failed to get their measure passed, they succeeded with the help of their employees’ unions in bringing about a change in War Department policy.

During talks leading up to the building trades agreement of 22 July 1941 the specialty trades unions asked that the government require principal contractors to sublet items usually subcontracted and to make any contractor who elected to handle such items himself “show affirmatively that such work is ordinarily performed by him and that his existing organization includes capable personnel and suitable equipment for the work.” Expressing the Navy’s attitude toward this proposal, Admiral Moreell informed Hillman: “The article as written ... establishes a procedure with such ... rigidity as to seriously encroach upon the duty and responsibility of the contracting officer to see that the work is performed in a manner such as to safeguard the interests of the Government.”80 Under the building trades agreement, the government accepted the unions’ provision, but reserved the right to waive the requirement to sublet when performance of specialty work by subcontractors would “result in materially increased costs or inordinate delays.”81 This agreement, while falling short of the subcontractors’ original demands, gave them stronger grounds on which to appeal for work. In August 1941, Patterson made further concessions. He adopted a new method of setting fees, whereby the principal contractor took a flat deduction for subcontracting regardless of whether he wished to sublet. Somervell revised the fee schedule for construction contracts accordingly.82 Specialty firms seemed assured of a larger share of defense profits.

While the specialty “subs” were winning these concessions, general contractors and third-party renters were intensifying their efforts to do away with recapture clauses. As lend-lease drained supplies of new machinery and obsolescence, wear and tear, and government capture depleted stocks in private hands, resistance to recapture stiffened. With an increasing amount of work available for remaining stocks, owners could ill afford to lose irreplaceable machinery needed for continuation of their businesses. The Army encountered more and more difficulty in renting. Third-parties were reluctant to bid, and those who did asked prices sufficiently high to insure against the risk of losing their stock in trade. Representatives of the construction industry joined with equipment dealers in recommending that recapture be discontinued.83 Managing Director Herbert E. Foreman of the AGC complained that recapture was putting “the contractor out of a job.”84 By the spring of 1941 Patterson was considering a change.

On 19 June he gave Generals Schley and Gregory permission to waive recapture. Two months later he took up a proposal to strike the recapture clause from the contract. Anticipating lower rents, the Engineers favored the move. Somervell opposed it, arguing that the government should retain the right to

acquire any piece of rented equipment. Despite Somervell’s objections, Patterson on 6 September banned the recapture provision from all future fixed-fee contracts. He made no changes in the third-party agreement. Although the Construction Division occasionally forwent recapture on third-party equipment during the latter half of 1941, field officers did not receive authority to waive the provision until mid-1942, a time when the shortage of equipment was most acute.85

Streamlined procedures, economy measures, and new contractual clauses failed to pacify congressional critics of the fixed-fee method. The Truman committee recommended curtailment of fixed-fee contracting. Congressman Engel went so far as to offer an amendment outlawing the contract on camp projects.86 In commenting on the Engel rider, General Somervell made his position clear. “I can say without reservation,” he told Representative Snyder, “that the amendment will do more to delay the War Department’s construction program than any other device which could be adopted without actually ordering the program stopped. It will delay the completion of the work on an average of six months.” Somervell conceded that fixed-fee contracts had certain disadvantages, but, he pointed out: “The cure proposed is worse than the disease. In fact, it will kill the patient.”87

Fear that fixed-fee contracts might be outlawed prompted consideration of changes which would “appease Congress, but do as little damage to the system as possible.”88 Somervell weighed the advisability of adopting several suggestions made by congressional committees—competitive bids on fees and bonus and penalty clauses. Some of his advisers believed that competition in regard to fees might forestall prohibitory legislation until most of the larger jobs were under contract or until fixed-fee agreements were no longer necessary. Others argued that while competition would reduce fees but slightly, bidding could easily result in awards to inferior contractors whose mismanagement would increase costs and cause delays. Advocates of the bonus and penalty clause maintained that by penalizing builders who ran over their estimates and rewarding those who made savings the Quartermaster Corps would give its contractors an incentive to hold down costs. Opponents of the clause entered a strong plea against its adoption. They pointed out that the British had used a similar provision early in the war with unsatisfactory results. They argued that bonus and penalty clauses smacked of percentage contracting. Finally, they said, where the War Department had sufficient information to draw the sound estimates necessary for a bonus and penalty provision, it could award a lump sum contract. After long and careful study Somervell decided

not to experiment. Leaning heavily upon advice from General Connor and Colonel Jones, he declined to risk popular but dangerous innovations.89

One criticism by the Truman committee cited the Army’s failure to take advantage of land-grant freight rates. The government had first obtained these special rates during the great period of railway expansion after the Civil War, when it had granted huge tracts of public land to the railroads on condition that charges for hauling troops and property of the United States would be very much lower than commercial rates.90 The Transportation Act of 1940 had restricted land-grant reductions “to the transportation of military or naval property of the United States moving for military or naval purposes and not for civil use.”91 Although there was little doubt that shipments to the Army’s construction projects came within the letter of the law, the Quartermaster Corps had been unable to benefit, for under the fixed-fee contract the United States did not take title to materials until after government inspectors had passed them and inspectors, for reasons of economy, had their offices at job sites rather than at shipping points throughout the country. Spurred on by Truman, Somervell at length found the answer—a contractual clause permitting the government to take title to shipments at points of origin and reserving to the contracting officer the right of “final inspection and acceptance or rejection ... at the site of the work or an approved storage site.”92 On Somervell’s recommendation Patterson incorporated this clause into the standard fixed-fee contract.93 Savings were reckoned in the millions.

If the Truman committee offered helpful suggestions, it also reached some debatable conclusions. The investigators supported their indictment of the fixed-fee method with questionable statistics. Analyzing 17 fixed-price and 29 fixed-fee camp projects, they found that the former had an average cost per man of $380, the latter of $684. These figures told an incomplete story. A majority of the contracts in the fixed-price sample were for additions to active posts or rehabilitation of abandoned World War I camps, where grading and utilities presented little difficulty. The fixed-fee projects were generally larger and more often in out-of-the-way places; and many were new installations. Most of the fixed-price jobs had started in the late summer and early fall of 1940; a majority of the fixed-fee contractors had begun work later and so had run into expensive winter construction. The committee had oversimplified the problem. Nevertheless, its well-publicized findings served to link fixed-fee contracts inextricably with high construction costs.94

In an effort to set the record straight, Somervell ran his own studies of variations in costs per man. At his request, Major Boeckh investigated 7 fixed-fee

cantonment projects and 2 lump sum. His computations showed that climate, weather, site conditions, levels of wages and prices, speed of construction, and other factors unrelated to the type of contract all affected costs.95 Gavin Hadden of Groves’ staff undertook a second, more thoroughgoing study. After analyzing 48 projects, 41 fixed-fee and 7 lump sum, Hadden came up with the following average costs per man:– $758 for fixed-fee cantonments against $399 for lump sum; and $751 for fixed-fee tent camps against $355 for lump sum. Warning that these figures were deceptive, Hadden wrote:–

Every one of the lump sum projects is located at a station previously existing and provided with utilities. The existence of roads on the sites of these projects had a double advantage, in reducing the cost of construction of the roads themselves and in reducing the costs of buildings and other utilities by providing for efficient handling of materials and labor during construction. Every one of the lump sum projects had been started before the first of the fixed-fee projects was started. This had a material effect in lowering costs because the bidders could not foresee the effects of the program as a whole on the labor, materials and equipment markets—effects which had a marked influence in raising the costs of the fixed-fee projects. This factor is not likely to be to the Government’s advantage again on any future lump sum projects.

To conclude ... that future projects could be constructed under lump sum contracts at costs per man as low as those for these past projects would therefore be erroneous.96

There was no simple answer to the Truman committee’s statements concerning costs of fixed-fee work.

Even as he attempted to counter attacks against the fixed-fee method, Somervell looked for ways to step up fixed-price contracting. In July 1941, when directives came through for the first advance planned camps, he asked Groves and Leavey to confer with representatives of the Associated General Contractors on the possibility of doing the work by lump sum contract. Among those present at the conference, held on 24 July, were Managing Director Foreman of the AGC and heads of six large contracting firms which had recently completed camp projects. The consensus was that only eight combinations of contractors in the United States could bid on a $20-million camp and that any bids offered on projects of this size would include a contingency item of about $5 million.97 The Construction Advisory Committee also questioned if lump sum contracts were feasible on these projects. Somervell was considering whether to abandon the attempt, when Patterson stepped in.98

Concerned by congressional criticism of fixed-fee contracts, the Under Secretary on 1 August called for an all-out effort “to place construction work on a competitive basis.”99 A few days later Somervell advertised for bids on two armored division camps, Chaffee, at Fort Smith, Arkansas, and Cooke, at Santa Maria-Lompoc, California.

Pessimistic, he predicted that attempts to let these contracts would serve as a “further demonstration” of the difficulty of using open bidding on such jobs.100 But contrary to his expectations, qualified contractors submitted reasonable bids. Contracts amounting to $17,380,670 for Camp Cooke and $15,512,780 for Camp Chaffee were awarded around 1 September. The low bid for Cooke exceeded the cost estimate by little more than $600,000. Although the experiment had been successful, Somervell did not repeat it during 1941. Because plans were incomplete, the three additional advance planned camps begun before Pearl Harbor were fixed-fee projects.101

In the fall of 1941, Patterson considered adopting a lump sum agreement as the standard form for architect-engineer contracts. Because the national engineering and architectural societies had declared competition among members to be unethical, and because low bids might come from poorly qualified firms, attempts to advertise were out of the question. For some years the Corps of Engineers had negotiated lump sum contracts for professional services; however, they had done so only when they had preliminary plans and definite information as to the character and scope of work.102 The Quartermaster Corps had let very few architect-engineer contracts on a lump sum basis. After an investigation of one such contract by the Construction Advisory Committee, General Connor characterized the results as “most unsatisfactory.”103

On 29 September Patterson approved a form for lump sum architect-engineer contracts. A week later he directed The Quartermaster General and the Chief of Engineers to use this form wherever possible. By 14 November the Construction Division had succeeded in negotiating 9 of the new agreements, 1 for an Ordnance plant, and 8 for troop housing projects. Efforts to let lump sum contracts for additional munitions projects failed. In light of this experience, Somervell recommended using the new form only when time was available for preparing accurate estimates. Pointing out that architect-engineers would not accept these contracts at a price advantageous to the government unless preliminary data were at hand, he continued to use fixed-fee agreements for design and supervision at most urgent projects.104 Perfected late in the defense period, the lump sum architect-engineer contract came into wide use only after the declaration of war.

For the Quartermaster Corps, defense construction had been largely a fixed-fee proposition. Between 1 July 1940 and 10 December 1941, the Construction Division negotiated 512 lump sum contracts amounting to $88,170,000, or approximately 5 percent of the total value of all its agreements. During the same period,

the division let 1,671 advertised lump sum contracts. The value of these competitive agreements was $240,132,000, or roughly 15 percent of the total. Fixed-fee contracts, though comparatively few in number, dwarfed the others in importance. Agreements with 154 construction firms and 149 architect-engineers amounted to $1,347,991,000 or 80 percent of the total.105 To most construction experts, the fixed-fee method was the logical one to use on high-speed emergency programs. They believed with General Schley that it was “hard to argue against it.”106 But political realities would militate against its use in the years ahead.

The Pentagon Project

On the evening of Thursday, 17 July 1941, Somervell summoned Casey and Bergstrom to his office. That day, at hearings before the House subcommittee on appropriations, Representative Woodrum had suggested that the War Department find an overall solution to its space problem. Somervell wanted basic plans and architectural perspectives for an office building to house 40,000 persons on his desk by 9 o’clock Monday morning. He envisaged a modern 4-story, air-conditioned structure, with no elevators, on the site of the old Washington-Hoover Airport, on the Virginia side of the Potomac. Designed to accommodate all War Department activities, the new structure would be the largest office building in the world. Casey and Bergstrom faced “a very busy weekend.”107

Hardly had they set to work before the plan changed. Looking over the airport site in the flood plain of the river, General Reybold concluded that construction there might not be feasible. On his advice, Somervell moved the location some distance to the north and west, to a 67-acre tract in the former Department of Agriculture experimental station, Arlington Farms, now a military reservation. So that the building would harmonize with its new surroundings—it would be just east of Arlington Cemetery and opposite the Lincoln Memorial—he reduced the height to three stories.108

The plans were in Somervell’s hands on Monday morning. A reinforced concrete structure, the building would have 5,100,000 square feet of floor space, twice as much as the Empire State. Fitted to its site, which was bounded by five roads, it would have five sides, hence the name Pentagon. Most of the interior space would be open, with temporary partitions. Only top officials would have private offices. An area of 300,000 square feet in the basement was for record storage. The layout included parking lots for 10,000 cars. Approved by Marshall, Moore, and Patterson that afternoon, the plan went to Secretary Stimson the following morning.109 “Skeptical” at first, Stimson at length concurred. “Of course,” he noted in his diary, “it will cost a lot of money, but it will solve not only our

Pentagon Building. Architect’s rendering of main entrance

problem, ... it will solve a lot of other problems, including the Navy and a lot of other people all around.” Having approved the plan, Stimson took it to the White House and obtained Roosevelt’s O.K.110

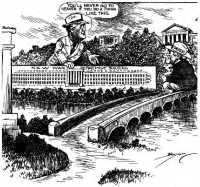

Presenting the plan to the House subcommittee on 22 July, Reybold and Somervell stressed its advantages. It would relieve congestion in other agencies which could occupy government buildings vacated by the War Department. It would save about $3 million a year in rentals. It would obviate the need for a $22-million building proposed for the Navy, which could take over the Munitions Building instead. It would release apartments for residential use again. It would increase the War Department’s efficiency by 25 to 40 percent. It would also be more convenient to the public which would no longer have to chase all over town to find the right man. The subcommittee members were favorably impressed. Their main concern was how much the building would cost. Somervell assured them that $35 million would cover everything except the parking area, which might come to about $1 million.111

The legislative machinery moved smoothly at first and then suddenly stalled. On the 23rd the House Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds met and, after hearing Somervell’s testimony, gave its unanimous approval to the project, agreeing to ignore the fact that Congress had voted no authorization.112 On the 24th the Appropriations Committee reported out the bill, recommending $35 million “for the construction of an office building on the site of the former Department of Agriculture Experiment Farm across the Potomac River to house all of the activities of the War Department.”113 But when the House took up the bill that afternoon, a hitch developed. Representative Merlin Hull, after expressing astonishment at the sheer size of the project, raised a point of order: the proposal

“to carpet 67 acres of Virginia farmland with brick and concrete” was unauthorized legislation.114 Woodrum and other supporters of the project tried to overcome Hull’s objections, but he stood pat. Decision on the bill hung fire until the following week.115

Unperturbed by this contretemps, Somervell went ahead to select a contractor and a Constructing Quartermaster. To erect the building the Construction Advisory Committee nominated three combinations of three firms each. Its first choice was John McShain, Inc., of Philadelphia, with the Turner Construction Company and George A. Fuller Company, both of New York City. The Fuller and Turner companies were among the giants of the industry, and Turner had pioneered in building concrete structures. McShain had built the Jefferson Memorial, the National Airport, and the Naval Medical Center and had recently completed the first unit of the New War Department Building in downtown Washington. Somervell was happy with the selection of McShain, but he rejected the two big New York concerns in favor of two Virginia firms, the Wise Contracting Company, Inc., and Doyle and Russell, both of Richmond.116 To direct the work of these contractors, he named Capt. Clarence Renshaw, one of Groves’ assistants. A West Point careerist, Renshaw had served as Assistant Constructing Quartermaster in charge of building the approaches to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier and restoring the Robert E. Lee Mansion.

Friday editions of the Washington newspapers played up the War Department’s “$35 million cubbyhole.” In a feature article, the Daily News reported:–

Not even a castle in the air Wednesday night, “Defense City, Va.,—Pop. 40,000” was on the congressional conveyor belt and the motor was humming. ... The House was ready yesterday to rubber-stamp the grandiose proposal ... but there may be some trouble in the Senate where Maryland has a highly vocal representative in Millard Tydings.117

The Post quoted the “dazed” manager of hard up Arlington County, who despaired of handling the influx without massive federal aid.118 An editorial in the Evening Star, which envisioned a project “so staggering in its proportions as to be difficult to grasp on short notice,” deplored the fact that no one had consulted the Commission on Fine Arts and the National Capital Park and Planning Commission.119 “Just to keep the record straight,” Representative Woodrum issued a press release that day, declaring that “the project was wholly and entirely the idea of the War Department,” and naming all those up through the President who had approved it.120

The following Monday, when the House resumed debate, Representative Hull claimed credit for having given “Congress and at least some of the press an opportunity to consider what was being brought in here under the guise of

national defense.” Several of his colleagues joined him in objecting to the project, which, said Hull, might cost twice $35 million “before the Federal Treasury gets through paying the bill.” Moreover, its opponents held, the building would consume labor and materials already in short supply, increase existing traffic problems, and be a white elephant after the war. Woodrum and his forces fought back. Three times that day Hull and his confederates tried to kill the proposal; three times they met defeat. The House passed the bill with the provision intact.121

As the Senate began hearings on the measure, opposition was stiffening. Time reported “a sizzling row over the War Department’s scheme to move to Virginia and build itself the ‘largest office building in the world’.”122 Protests came from the D.C. Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, the National Association of Building Owners and Managers, outraged Washingtonians, and others. In a letter to the Senate Appropriations Committee, Chairman Gilmore D. Clarke of the Commission on Fine Arts objected to the “flagrant disregard” of the policy to reserve the Arlington area for burial of the honored dead and to the “introduction of 35 acres of ugly flat roofs into the very foreground of the most majestic view of the National Capitol.” In a similar vein, Frederic A. Delano, chairman of the National Capital and Park Planning Commission and a cousin of the President, wrote: “No other emergency except war would justify such permanent injury to the dignity and character of the area” near the cemetery. Delano concentrated on the “single question of the practicability of the project as a whole,” that is, on the problems of utilities and of transportation in relation to the probable residences of employees. His investigations indicated that extending water and sewer lines would pose no special difficulties, but transportation was a different matter, since a mere 12 percent of War Department employees lived in Virginia. He questioned putting the entire War Department staff in one place and recommended scaling down the building to accommodate only 20,000. Delano and Budget Director Harold D. Smith went to the White House to protest the project on 30 July. The next day the President wrote Chairman Alva B. Adams of the Senate Subcommittee on Deficiencies that he had “no objection to the use of the Arlington Farm site” but agreed with Delano that the size of the building should be reduced by half.123

When Senator Adams’ group took up the matter on 8 August, its primary concern was with the site. Many alternatives lay open, most of them in the District. A last-minute entry was an area earmarked for a Quartermaster depot, three-quarters of a mile southeast of the disputed Arlington Farms location: a switch to this site would surmount aesthetic objections to the project though it would not solve the transportation problem. Somervell held out for Arlington Farms, arguing that

a change of location would mean scrapping plans already drawn, cause a month’s delay in getting started, and add materially to the cost of the building. He saw nothing inappropriate in having Arlington Cemetery overlook the home of the War Department.124

After the hearings ended, Somervell persisted in trying to sway the subcommittee. At his urging, Patterson wrote to Senator Adams, expressing concern that the War Department might have to accept the depot site, which, with its warehouses, railroad yards, and unsightly shanties, was “unworthy of the dignity of the Department.”125 Somervell also had Bergstrom prepare a memorandum extolling the advantages of Arlington Farms as “superbly located” and terming the depot site “as inappropriate for a building for the War Department as could be found.”126 After inspecting both sites, the Adams subcommittee agreed unanimously on the War Department’s choice, and the full Appropriations Committee overwhelmingly endorsed it. There was little opposition on the floor of the Senate. The bill passed.127 To get everything in order so that work could start as soon as the President signed the measure, Somervell on 19 August called in Groves, Leavey, Casey, Renshaw, Bergstrom, and McShain. Flourishing a tentative directive, he announced these goals: 500,000 square feet of floor space available on 1 March 1942 and the entire building completed by 1 September. Bergstrom would serve as architect-engineer. Renshaw would report directly to Groves. For an hour and a half, the conferees looked over contour maps, tentative layouts, excavation plans, foundation drawings, structural blueprints, and bills of materials. The meeting broke up on a euphoric note—the project was set and ready to go.128

Events of the next few days knocked Somervell’s plans into a cocked hat. On the 20th the New York Times intimated that the President would veto the $7-billion defense appropriation bill in order to block the Arlington Farms site. As Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1917, Roosevelt had helped talk President Wilson into putting up temporary buildings on the Mall along Constitution Avenue. Those eyesores were still there. Roosevelt, reportedly, was trying to atone for this early blunder by preventing another, more serious one.129 The story proved to have substance. Summoning Somervell and McCloy to the White House, the President turned down Arlington Farms. When Somervell objected that a move would cost money, Roosevelt was unresponsive.130 On 25 August he signed the bill, reserving the right to pick the location. At a press conference the following day, he explained what sort of structure he had in mind. It would be at the depot site and half the size originally contemplated. After the war, he hoped to see the War

Cartoonist’s view of controversy over Arlington Farms site for Pentagon

Department housed in the Northwest Triangle and this building used for storing records.131

Pulling down a curtain of secrecy over the project, Somervell followed an independent course. Losing no time in breaking ground at the depot site, he pushed work on designs and blueprints. By early October Bergstrom had completed the basic drawings. These plans depicted a three-story edifice of reinforced concrete in the shape of a regular pentagon. With 4 million square feet of floor space, the structure would be the largest office building in the world. Set in a 320-acre landscaped park, it would overlook plazas and terraces leading up from a lagoon created by an enlargement of the Boundary Channel. A six-acre inner court, numerous ramps and escalators, a large shopping concourse on the first floor, cabstands and bus lanes in the basement, parking lots for 8,000 cars, and an elaborate system of roads were among its distinctive features.132 Functional, commodious, and, as one general put it, “so right” for the War Department, the building seemed unlikely ever to serve as a records depository.133

Taking the plans to the White House on 10 October, Somervell presented Roosevelt with an accomplished fact. Construction had been under way for nearly a month, a thousand men were at work, and hundreds of 30-foot concrete piles were in place. Part of the foundation had been poured and forms for a section of the first story were ready. Predicting completion in 14 months, Somervell put the cost at about $33 million. Falling in with the scheme, the President imposed but one restriction—that there be no marble in the building. When Somervell suggested facing the outer walls with limestone, Roosevelt raised no objection. If it lacked the elegance of the Capital’s classic architecture, the new structure would, nonetheless, be handsome and imposing.134

Interest in the choice of materials ran high, as competing industries and rival states vied with one another for a share in the prestigious project. Typical of the many letters received by Renshaw was one from a Georgia Congressman, complaining that specifications for granite steps at the entrance limited the choice to North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Maine. Also typical was the CQMs reply: although Georgia granite would not harmonize with the color of the façade, it might find a place elsewhere in the structure.135 By far the loudest uproar was over the building’s 9,000 windows. When invitations went out late in October for alternate bids on steel and wood sash, manufacturers of wood sash promptly cried “foul,” claiming that the specifications gave steel an edge. A flood of letters and telegrams inundated the War Department. Somervell and McShain wished to ignore the clamor, but OPM would not agree; and by 10 November new invitations were in the mail. At an opening on the 18th, steel won out. Although the

question was settled, protests continued for weeks.136

Bothersome though they were, outside pressures did not present anything like the trouble raised by shortages of materials. Proceeding under the watchful eye of defense production officials, architect Bergstrom took steps to conserve critically needed metals. His design for concrete structural framework made possible a saving of 43,000 tons of steel, more than enough to build a battleship. His use of concrete ramps instead of elevators reduced steel requirements still further. Drainage pipes were concrete; ducts were fiber; interior doors were wood. An unusual wall design—concrete spandrels carried to window sill level—eliminated many miles of through-wall copper flashings. When OPM called for still more drastic reductions, Somervell agreed to “strip-tease” the entire structure. Bronze doors, copper ornamentation, and metal partitions in toilets were among the first to go, but the stripping process continued throughout the life of the project.137

As work progressed on the foundation, an important decision loomed: would walls on the interior courts be of brick or concrete. Groves, who favored brick, afterward explained: “Despite all our past troubles with bricklayers, I thought it would be better to have the exterior of brick. ... It would put pressure on the bricklayers throughout the country to have this work under the close observation of Congress. The result would have been an overall increase in their production.”138 Moreover, he agreed with McShain that brickwork would be cheaper and faster. But Bergstrom held out for architectural concrete. He planned to leave a gap between the form boards so that the mixture would ooze and form a ridge, thus simulating limestone. At Groves’ suggestion, workmen built sample walls, and, on 14 October, McShain telephoned disturbing news—honeycombs had developed in the concrete.139 Even so, Somervell went along with Bergstrom. Although the concrete walls added $650,000 to the cost of the building, they greatly enhanced the structure’s architectural coherence.140

Plans were the principal bottleneck. Ordinarily, the architect for a large permanent building had many months start on the contractor. Bergstrom and David J. Witmer, a prominent Los Angeles architect who came in to assist him, had virtually no lead time. In late October McShain reported that if design information were available he could triple his present force. On the 28th Renshaw, McShain, and Bergstrom reviewed the problem but found it unsolvable.141 Pressure on the architect for delivery of drawings became more and more intense. At times, construction ran ahead of planning, so far ahead, in fact, that Leisenring, who had charge of specifications, referred to his group as the “historical records” section; by the time “specs” were completed, a

different material was already in the building.142

An unusually high accident rate was an added worry. At a meeting on 5 November the executive committee of the Building Trades Council voted to probe into the “alarming” number of mishaps at the project. In a statement to the press, a committee spokesman referred to several deaths and many severe injuries, including broken backs, and he put the blame on the War Department’s failure to enforce its own safety regulations.143 An investigation by Blanchard and other members of Groves’ Safety Section showed that the report was exaggerated. There had been 40 lost-time accidents, with some simple fractures, and one fatality, but no broken backs. Blanchard agreed the accident rate was high—about four times that of the Army program as a whole. Acting on his advice, Groves instructed Renshaw to see that the contractor employed a full-time safety engineer and followed War Department safety regulations to the letter. Although McShain complied, the accident rate did not measurably decline. Perhaps, as he asserted, mishaps were an unavoidable byproduct of speed.144

By 1 December 1941, 4,000 men were working three shifts a day on the huge edifice. At night the project blazed with light. Between 2 and 3 percent complete, construction was far enough along so that the pentagonal shape of the building was apparent. The contractors had relocated one mile of railroad line, lowered the water table of the old airport eight feet, started work on the power plant, and graded more than 100 acres of land. Barges were delivering sand and gravel to the Boundary Channel shore. The job was making headway, but the bulk of the work remained. At the rate of progress so far, a little more than 1 percent per month, it would take more than eight years to complete the building.145