Chapter 2: The Engineers Cross the Atlantic 1941–1942

In the late spring of 1941 a few American officers in civilian clothes slipped into London and established a small headquarters in a building near the American embassy on Grosvenor Square. They might have been attaches of the embassy, as far as the general public could tell. Their name, Special Observer Group (SPOBS), like their attire, concealed rather than expressed their functions, for they had much more urgent business than to act as neutral observers of the military effort of a friendly nation at war. They were organized as a military staff complete with G-1 (personnel), G-2 (intelligence), G-3 (plans and operations), and G-4 (logistics and supply), together with a full complement of special staff officers. The group was located in England so that close liaison with the British High Command would be in effect should American quasi-neutrality suddenly shift into active belligerence. The group’s mission was to coordinate plans, so far as circumstances permitted, for American participation in the war, and to receive, house, and equip American forces.

The engineer officer of the Special Observer Group was Lt. Col. Donald A. Davison, who had been the General Headquarters (GHQ) Air Force staff engineer in Washington.1 Barely a year had passed since Colonel Davison had organized the 21st Engineer Aviation Regiment, the Army’s first engineer aviation unit. He was an obvious choice for the SPOBS staff, for the group was to be concerned first of all with planning facilities for future air operations and air defense. The emphasis on air power was apparent also in the choice of Maj. Gen. James E. Chaney, AC, to head the group, and of Brig. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, AC, as General Chaney’s chief of staff.

The Special Observer Group at first numbered eighteen officers and eleven enlisted men. While the task of planning the transportation of U.S. Army troops, their location in the United Kingdom, and their shelter involved the entire SPOBS staff and their opposites in the British Army, much of the work fell to the engineer officer. Construction planning for the U.S. Army in the British Isles was the responsibility of five officers: General McNarney; Lt. Col. George W. Griner, Jr., ACofS, G-4; Lt. Col. John E. Dahlquist, ACofS,

G-1; Lt. Col. Charles L. Bolte, ACofS for Plans; and Colonel Davison. In November 1941 Colonel Davison also began to function as a member of a new technical committee, which represented an expansion of the duties of the Special Observer Group and a step toward closer liaison with the British.2

Reconnaissance

For many weeks in 1941, Davison and officers of the group toured those areas to which American forces would be sent if the United States entered the war. SPOBS activities were guided by the basic American war plan, RAINBOW-5, and an agreement designated ABC-1, which resulted from meetings held early in 1941 by representatives of the British Chiefs of Staff, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, and the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations. Features of ABC-l relating specifically to initial American activities in the European theater included provisions for the defense of bases in Scotland and Northern Ireland to be used by U.S. naval forces, the establishment of a U.S. bomber command to operate from England, the dispatch of a U.S. token force for the defense of Britain, and American relief of the British garrison in Iceland.

Between 27 May and 21 November 1941, representatives of the Special Observer Group attended eight meetings of the Operational Planning Section of the British Joint Planning Staff; the group had its first meeting with the British Air Ministry on 6 June. These meetings promoted practical cooperation between the SPOBS staff and British officers. Soon after the 27 May meeting the British War Office submitted a list of questions to General Chaney concerning accommodations for U.S. troops. This questionnaire brought up many points considered in detail by officers who in the summer and fall of 1941 inspected areas in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Kent where the token force probably would be located. The British had already undertaken much of the construction necessary for the accommodation of American troops in those areas, but much more needed to be done to extend and improve roads and to provide housing and other necessary structures for the troops.

The rush of events following Pearl Harbor outdated the recommendations and detailed planning that resulted from these tours. Colonel Davison and the other SPOBS officers nevertheless obtained valuable information concerning resources, equipment, housing, and British methods. Most important, the inspection tours promoted the practical teamwork with the British that was later so essential to the war effort. After the inspection tour of Northern Ireland in July 1941, the surveyors reported to the War Department that the chief engineering problem in Ulster was to provide housing for the approximately 27,000 troops envisaged in RAINBOW-5. The British would be able to supply all the Nissen huts required, and crushed rock and cement could be

obtained in England.3 Lumber and quarrying machinery were scarce, however, and hardware would have to come from the United States. One engineer aviation battalion and a general service or combat engineer regiment would be needed to do general construction and airfield maintenance.4

The plans for Northern Ireland were eventually carried out with minor deviations, but this was not the case for most of the other areas surveyed in the United Kingdom. After American entry into the war the bases in Northern Ireland became more important than those in Scotland as a new war strategy gave less relative weight to air defense and offense and more to preparations for invasion of the Continent.

The SPOBS officers surveyed three widely separated sites for prospective Army installations in Scotland: Gare Loch, Loch Ryan, and Ayr Airdrome. SPOBS estimated that new construction would be necessary to support some 6,000 troops: about 860 Nissens for housing; a hospital at Ayr; and 27 storage Nissens distributed among the three areas. An American contractor was then at work on U.S. Navy installations at Gare Loch and Loch Ryan at opposite ends of the Firth of Clyde. In view of the serious labor problem in the United Kingdom, the officers suggested three alternatives: concluding an agreement with the Navy to extend its contracts to cover the Army construction; letting new Army contracts with the same companies; or shipping one engineer general service regiment to Scotland ahead of the first convoy to put up the hospital and troop barracks using British Nissen huts.5

The proposed token force area in England lay southeast of London, near Wrotham in Kent. SPOBS officers checked the site during late August and early September, recommending that an engineer unit, with a planned strength of 543 men of the 7,600 in the token force, bring all TOE equipment. Engineers in this district would support an infantry regiment in the field, build many new roads, and maintain or widen the narrow, winding roads in the area. The SPOBS report pointed out that supplies for the building of field fortifications and obstacles should be sent from the United States!6

SPOBS officers also inspected a contemplated supply or base area near Birmingham and a proposed bomber command site in Huntingdonshire, both in the Midlands. General Chaney sent to the War Department in the summer and fall of 1941 a series of reports, based largely on studies and estimates prepared by Colonel Davison, that summed up the surveys from an engineering standpoint. A report of 17 December 1941 summarized Colonel Davison’s recommendations for construction. Although dated ten days after Pearl Harbor, the report was based on the earlier concept of air strategy that had governed all SPOBS activity in the United Kingdom in 1941.

Unlike the earlier ones, the 17 December report took for granted the arrival of American troops in Britain. Britain’s limited material and labor resources were already severely strained, and it was obvious that supplemental American labor and materials would be needed. Starting construction before the troops arrived was essential, but the threat of enemy submarines and a shipping shortage dictated moving only a minimum of materials from the United States. Since troop labor was desirable only if civilian labor was not available, the final report pointed out that the War Department would have to determine policy, proportions of skilled and unskilled civilian and troop labor, and many details relating to materials, contracts, and transportation. Matters relating to sites, construction details, and utilities would have to be handled in the United Kingdom.7

The report provided figures on housing already available together with estimates of housing that would have to be built. Somewhat more than 11,000 standard 16-by-36-foot quartering huts were needed, as well as nearly 500 40-by-100 foot storage and shop buildings, and 442 ordnance igloos. Buildings for 10,000 hospital beds would also have to be built. Hard-surface paving construction for airfield access roads and for aircraft hardstandings added up to 182 miles.

Colonel Davison was better acquainted than anyone else with the engineering problems that the Army had to face in Britain and had studied all the proposed sites in detail. He knew the views of the SPOBS staff and those of the British War Office. Accordingly, on General Chaney’s recommendation, he went to Washington in January 1942 to help plan the movement of troops and their accommodation in Britain.8

Iceland

In June 1941 SPOBS engineers also undertook a survey of locations in Iceland, where an American occupation was imminent. Construction of facilities began before Pearl Harbor as Americans moved in July 1941 to replace the British on the island.9

Iceland had great strategic importance. The British occupied the island in May 1940 to prevent its seizure by the Germans, in whose hands it would have formed a base for attack on English soil and on the British shipping lifeline. Britain had acted quickly to develop air and naval bases in Iceland to protect the North Atlantic convoy routes. Yet by the summer of 1941 British reverses in the western Sahara prompted plans to withdraw the Iceland garrison for use in the desert and elsewhere. Talks begun in February 1941 during the British-American ABC-1 meeting set the stage for a timely invitation from the Icelandic Althing (Parliament) for American troops to replace the British. Thus, belligerent Britain proposed to leave the defense of neutral Iceland to the quasi-neutral United States.10

On 11 June 1941, Colonel Davison and seven officers arrived on the island and by 18 June could report that from an engineering standpoint Iceland had little to offer. Without trees there was no lumber. Practically all supplies had to move through the poorly equipped port of Reykjavik. Ships exceeding 470 feet in length and 21 feet in draft could not moor alongside the two quays that served the harbor. The climate offered a mean winter temperature of 30°F and a summer mean of 52°F, but rainfall of nearly fifty inches a year and midwinter winds of eighty miles per hour made working and living conditions severe. Only volcanic rock, gravel, and sand were abundant on the bleak island. Two airdromes built by the British were usable immediately but required work to conform to American standards and expansion to accommodate heavier American traffic. Added to Reykjavik Field in the city itself and the Kaldadharnes Airdrome, some thirty-five miles southeast of the capital, were other rudimentary fields such as Keflavik, on a windswept point of land twenty-five miles southwest of Reykjavik. A grass field with a runway 1,000 yards long and 50 yards wide, it was suitable for emergency use only. The SPOBS officers believed that another site sixty miles southeast of the capital, known as the Oddi Airdrome, gave promise of immediate development. Two other fields were too remote even to be visited on the hasty tour: Melgerdhi in the north, 13½ miles from Akureyri, and another emergency field at Hoefn in the southeast.

Voluminous, if spotty, collections of similar data reached Washington from military and naval teams scanning the island’s facilities. A Navy party came over from Greenland looking for likely naval air patrol bases, and another Army-Marine Corps party arrived after Colonel Davison’s departure. General Chaney sent the SPOBS report to Washington with Lt. Col. George W. Griner, Jr., the SPOBS G-4 who had accompanied Davison. War Department planners compiled the information for the projected occupation of Iceland under the code name INDIGO.11

After some changes in planning and a revision in the concept of the operation that committed American troops to the reinforcement and not to the relief of the British 49th Infantry Division on the island, a convoy with the 4,400 officers and enlisted men of the 1st Provisional Brigade (Marines) under Brig. Gen. John Marston, USMC, arrived at Reykjavik on 7 July 1941. Army engineer troops reached that port on 6 August 1941 as part of the first echelon of Task Force 4 (92 officers and

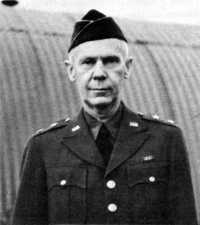

General Bonesteel

1,125 enlisted men), the first U.S. Army contingent to reach Iceland. The force consisted of the 33rd Pursuit Squadron, which flew in from the USS Wasp offshore; an air base squadron; and a number of special service detachments to contribute to the air defense of Iceland. Engineer elements were two companies of the 21st Engineer Aviation Regiment, soon to be redesignated the 824th Engineer Aviation Battalion. On 16 September 1941, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Engineer Combat Regiment, arrived with the second echelon of Task Force 4; the entire American force in Iceland became the Iceland Base Command on the same day. The command, under Maj. Gen. Charles H. Bonesteel, remained directly subordinate to the field force commander in Washington, General George C. Marshall. Because of British strategic responsibility for Iceland, General Chaney continued to argue for the inclusion of the American garrison in Iceland under his control, but his viewpoint did not prevail until the summer of the following year.12

During the first days in Iceland, the engineer troops lived in tents previously erected by the Marines, and other units moved into Nissen huts provided by the British. For a few days after the landing of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Engineer Combat Regiment, there was considerable confusion. The base engineer, Lt. Col. Clarence N. Iry, who had come with the Marine brigade, reported much equipment broken by careless loading and handling. The material and specialized equipment for an entire refrigerated warehouse were damaged beyond recovery. Navy pressure for quick unloading did not improve matters since there was no covered storage space in Reykjavik waterfront areas and too little dump space elsewhere. In the confusion the property of various units went widely astray; several weeks passed before the engineer battalion located all its belongings and assembled them in one place.13

The engineers took up a building, repair, and maintenance program well begun by the British. At first their work supplemented that of the Royal Engineers, and not until late in 1942 did they replace their British counterparts

Construction supplies at Reykjavik harbor, October 1941

entirely. But the main construction activities of the war years were already evident: building airdromes, improving communications and supply facilities, and constructing adequate camp and hospital accommodations. The program, originally limited to the more settled part of Iceland in the vicinity of Reykjavik, extended gradually to remote regions along the northern and eastern coasts.

The principal problems of construction lay in the forbidding terrain, high winds, poor communications, and the consequent difficulties of supply. Outside the southwestern corner of the country, the roads—or the lack of them—made long-distance hauling of bulk supplies impossible. Iceland had no railroads. Though most shipments funneled through Reykjavik and then moved on to these outposts by smaller craft, vessels from the United States occasionally touched at Akureyri, Seydhisfjordhur and Budhareyri, ports that had remained ice free year-round since 1918. Other than the rock, sand, and gravel obtained locally, all engineer supplies came from the United States and Britain. Nissen hutting, coal, and coke were the principal supplies from Britain; the Boston Port, of Embarkation handled the remainder of the Iceland garrison’s needs including the interior fittings for the huts and any necessary equipment.14

Engineer troops dumping fill at Meeks Field, Keflavik

For storage and quarters the engineers followed the British example and used Nissen huts that could withstand the wind. Standard warehouse and barracks construction could not stand up to the elements, and even the huts suffered when gales ripped the metal sheeting from the frames. The men banked earth and stone against the sides of the structures to anchor and insulate them and slung sandbags on cables across the arched roofs for stability. Any loose material outside in open storage had to be staked.15

During the first weeks after Task Force 4 arrived, the engineers rushed to complete troop housing and covered storage and pushed to extend the docks in Reykjavik harbor. Nearly everywhere they struggled with a subsoil of soggy peat covered with lava rock. As autumn drew on, they moved ahead with expanding airdromes on the island.

By late 1941 American engineers had gradually taken over airfield construction from the British. Reykjavik Field was under development by a force of 2,500 British engineers and Icelandic workmen when the 21st Engineer Aviation Regiment arrived with its heavier construction equipment. The Americans

took over the western side of the field, their first responsibility being a foundation for a British prefabricated hangar. In November the British pulled out of all work at the site except for some road work on their side of the airdrome. At the end of the year, the 21st was in full control of the operation and supervised the contracted Icelandic labor on the perimeter roads surrounding the base. The departure of the Royal Engineers in November and December 1941 also brought the 21st to the Kaldadharnes site, and survey parties began laying out what became the largest airfield in Iceland at Keflavik.16

The last of the Marine contingent left Iceland in March, and by mid-1942 the Iceland Base Command numbered 35,000 Army officers and enlisted men, with the requirement for engineer support growing steadily. With the 824th Engineer Aviation Battalion—an offshoot of the former 21st Engineer Aviation Regiment—engaged in airfield work, the 5th Engineer Combat Regiment built most of the troop quarters, laundries, kitchens, refrigeration and ice plants, and hospitals for the garrison until the arrival of the 7th Engineer Combat Battalion in May 1942. Work on roads to connect the outposts established by or taken over from the British on the northern and eastern coasts developed in stride with housing and airdrome construction. (Map 1)17

The limited stretches of hard-topped roads in the Reykjavik area remained serviceable, but the gravel tracks elsewhere took a constant beating from heavy Army traffic. The 5th Engineer Combat Regiment regraded and metalized surfaces where necessary and applied a top course of red lava rock mixed with a finer crushed grade of the lava, a composite also used for the hardstandings, taxi strips, and service access roads around the airfields.18

The 824th Engineer Aviation Battalion still employed hundreds of Icelanders on the perimeter roads and hangar aprons at the Reykjavik Field but gradually centered its efforts on the huge complex at Keflavik. On the wind-swept peninsula, two separate fields—Meeks Field for bombers and Patterson Field for fighter aircraft—took shape, both ready for operation in early 1943. Work here was carried on by the 824th in early 1942 and then taken over by a U.S. Navy contractor. Navy Seabees also arrived to work under Army engineer supervision after the civilian contractor returned to the United States. Beset by high winds that scoured the featureless landscape, the engineers devised expedients in the final phases of runway construction. When the wind churned the powdery top surfaces of newly graded runway beds into dust storms, they laid on liquid asphalt. But with September frosts, the asphalt cooled

Map 1: Iceland 1943

and coagulated before it could penetrate the lava deeply enough to stabilize it. Later experiments with a porous-mix base produced a runway rugged enough to take heavy Navy patrol craft and Army bombers on the ferry run to England.19

The Iceland Base Command converted Iceland into a great protective bastion for the convoy routes to Europe. Engineer-constructed facilities on the island housed American defense forces that guaranteed one outpost on the way to the embattled United Kingdom, which became the principal focus of American interest in the Atlantic area after Pearl Harbor.

Magnet Force

With the United States an active belligerent, on 2 January 1942, the U.S. Army replaced SPOBS with U.S. Army Forces, British Isles (USAFBI), a more formal headquarters that was initially only SPOBS in uniform. But creation of the headquarters made the American officers full partners of their opposites on the British staff.

On 5 January 1942, the War Department placed the engineers in charge of all overseas construction, but it was February

before Colonel Davison, still in Washington, got Army approval for a USAFBI construction program. Pressures to bolster home defenses and desperate attempts to stop the Japanese in the Pacific were absorbing the energies of Washington officials, and still another month went by before Colonel Davison could obtain facts and figures from the Office of the Chief of Engineers (OCE) concerning labor, materials, and shipping requirements. This was hardly accomplished before the War Department called upon USAFBI to reduce estimated construction to the minimum, despite General Chaney’s repeated warnings that more construction, especially housing, would be required than had been planned in December.20

ABC-1 and RAINBOW-5 provided for sending an American token force to England, but America’s new belligerent status and British needs brought some changes. New plans called for the earliest possible dispatch of 105,000 men (the MAGNET Force) to Northern Ireland. For tactical purposes, the force was to be organized as V Corps, made up of the 1st Armored and the 32nd, 34th, and 37th Infantry Divisions, with supply and service troops as well as air units. Of the total, 13,310 were to be engineers. Engineer plans for MAGNET Force gave detailed instructions on landing, administration, depot operations, and supply levels, with heavy reliance on the British for accommodations and supplies. From January to June 1942 engineers in the United Kingdom concentrated on installing the MAGNET Force in Northern Ireland.21

American troops and aircraft went to Northern Ireland to defend Ulster from air raid or invasion, to lift morale in the United States and in the United Kingdom, and to release British troops for action in the threatened areas of the Near East and Africa.22 But carrying out deployments to Northern Ireland on the scale envisaged in MAGNET Force proved inexpedient because of the initial deployments of shipping to meet the Japanese onslaught in the Pacific. Decisions concerning the size and makeup of the final MAGNET Force changed from time to time during the early part of 1942. On 2 January the War Department set the first contingent at 14,000; a week later the figure was increased to 17,300, but on 12 January it was reduced to 4,100 in order to speed troop movements to the Pacific.23

This American strategic uncertainty after Pearl Harbor led to contradictions in events in the British Isles. Though the decision to defeat Germany first remained unquestioned, the implied troop buildup in Britain did not necessarily flow from that decision. Rather, as American leaders attempted to meet the demands of a two-front global war, engineer work in Northern Ireland was determined by the exigencies of the moment and not by a comprehensive

General Chaney, ambassador John G. Winant, and General Hartle inspect American installations in Ulster, Northern Ireland, February 1942

construction program supporting a strategic plan.24

MAGNET Force started with little notice. An advance party under Col. Edward H. Heavey left New York secretly on 6 January 1942; with it was Lt. Col. Donald B. Adams, the V Corps engineer. The party sailed from Halifax on a Norwegian ship and reached Scotland on the nineteenth. Colonel Adams and the other officers went to London for a week of briefing, and the rest of the party moved on to Belfast. A brigadier of the Royal Engineers guided Adams almost from the day he reached Northern Ireland, acquainting him with British Army methods and with the type of work demanded of him in Northern Ireland.25

On 24 January the U.S. Army Northern Ireland Forces formally came into existence. The first troop contingent, under Maj. Gen. Russell P. Hartle of the 34th Infantry Division, arrived on the twenty-sixth. The troop strength of 4,100 set for 12 January was not reached; a USAFBI report of 15 February showed 3,904 troops and 12 civilians in Ulster. By mid-March, after the second increment had arrived, U.S. Army Northern Ireland Forces totaled 11,039 officers and enlisted men. This force included two engineer combat

battalions and three separate companies of engineers.

The third and fourth increments arrived on 12 and 18 May respectively. The fourth, 10,000 troops aboard the Queen Mary, had to go ashore in lighters, for the great vessel was too large for Belfast harbor. Meanwhile, the 32nd and 37th Infantry Divisions had been diverted to the Pacific, and at the end of May V Corps consisted of the 34th Infantry Division, the 1st Armored Division, and some corps units. No engineer construction units were in the theater. The final engineer component consisted of a combat regiment, two combat battalions, and four service companies. During May, MAGNET Force reached its peak of 30,000 U.S. Army troops in Northern Ireland, some 70,000 fewer than called for originally.26

U.S. Army engineers had to undertake relatively little construction, for nearly all the American troops brought to Northern Ireland moved into camps British units had vacated. British engineer officers made the arrangements and furnished moveable equipment and supplies such as furniture, light bulbs, and coal. Each camp commander appointed an American utility officer to be responsible for camp maintenance and to provide fuel, equipment, and waste disposal service. Arrangements were made to have American soldiers admitted to hospitals serving British and Canadian units.27

The Americans depended on the British for additional construction necessary to house U.S. troops. In fact, the British did most of the planning as well as the building. The first U.S. Army engineer organizations, which settled in Walworth Camp in County Londonderry on Lough Foyle, did not receive their organic equipment, including vehicles, until weeks after the troops arrived. With the “force mark” system, each unit’s equipment was coded before shipment overseas; men and supplies went on different ships, the equipment usually on slower moving vessels. This system plagued almost all engineer units arriving in the United Kingdom during 1942. Yet almost as soon as the first engineer troops landed, the War Department called for a complete construction program for U.S. Army forces scheduled to arrive in Northern Ireland. March was over before Colonel Adams could submit a detailed study, for he had little more than a skeleton engineering staff.28

At first, the most essential projects were building and enlarging engineer depots. The V Corps commanders established a new depot at Desertmartin in the southern part of County Londonderry and decided to enlarge an existing depot at Ballyclare in Antrim north of Belfast, adapting it to American use. Once a site was picked, the engineers were to design the depot—type of building construction, layout of buildings and access roads, railroad service, and

concrete hardstandings. They undertook little actual construction, however.29

Work on enlarging the depot at Bally-dare and force headquarters near Wilmont, south of Belfast, began early in February. After the Ballyclare construction was finished, a company of the 107th Engineer Battalion (Combat) remained there to operate the depot, aided by work and guard details from the 467th Engineer Maintenance Company. From 1 March to 31 August the 112th Engineers (originally a combat battalion and in June enlarged and redesignated a combat regiment) worked at Desertmartin except for three weeks in late March and early April when it furnished troops to make repairs at force headquarters. Such units as the 112th Engineer Combat Regiment, Company A of the 109th Engineer Combat Battalion, the 467th Engineer Shop Company, the 427th Engineer Dump Truck Company, and the 397th Engineer Depot Company chiefly enlarged existing facilities to meet American standards and needs.30

By May the supply situation, except for organizational equipment, was comparatively satisfactory. As early as 20 February, engineer items were sixth on the shipping priority list (below post exchange supplies) and using units, upon their arrival from America, requisitioned engineer supplies almost immediately. Day-by-day requirements determined the use of supplies, for the engineers had no experience and no directives to guide them. Yet by May, Colonel Adams could report that engineer supplies were generally adequate. Originally, a system was established to maintain a sixty- to ninety-day level of supplies, taking into account not only those troops already in Northern Ireland, but also those due to arrive within the next sixty days. Some of these supplies came from the United States without requisition, others by specific requisition, still others by requisition of British military supplies, and a certain amount by local purchase. Incoming supplies went to the engineer depots at Desertmartin and Ballyclare, and some equipment went to Money-more General Depot, a British depository taken over for U.S. Army use in County Londonderry west of Lough Neagh.31

Shortages of organizational equipment persisted, in part because of the delays caused by the force mark system; at the end of March organizations in the theater had only 25 percent of their equipment. Five months later, 85 percent was on hand, but by this time Northern Ireland had declined in significance. Some of the equipment was entirely too light for the construction demands made on it.32

On the whole, the engineers sent to Northern Ireland had had scanty training in the United States except in basic military subjects, and overseas they had little chance to learn their jobs. The

112th Engineers, a combat battalion redesignated a regiment in August 1942, was constantly engaged in construction and was able to give only 10 percent of its time to training outside of that received on the job. Though valuable, such work did not train the unit for the many other missions of a combat regiment in which it had had no real instruction since September 1941. Thirty percent of the men in one battalion had recently transferred from the infantry, and many of the enlisted men in the unit had never learned any engineer specialties.33 The men of the 107th Engineer Battalion (Combat) at Bally-dare were supposed to be undergoing training, but they were called on so often to enlarge force headquarters and rehabilitate the Quartermaster Depot at Antrim that little time remained.34

Even when time was available, the lack of space hindered training. Agricultural land could not easily be withdrawn from production to provide room for military training. Engineer organizations were unfamiliar with British Army procedures even though after February 1942 Royal Engineer schools were open to American troops. The first attempt to teach British ways was limited, but eventually such instruction became an essential part of U.S. Army engineer training.35

On 1 June 1942, the Northern Ireland Base Command (Provisional) was formed to relieve V Corps of supply and administrative problems so that it could, as the highest ground force command in the United Kingdom, devote its full time to tactical preparations. The arrangement was short-lived; the command soon became part of a Services of Supply in the newly formed European Theater of Operations under the more normal designation of a base section. The decisions that led to the formation of the theater presaged the decline in importance of Northern Ireland as a base. By the summer of 1942 the main combat forces in the MAGNET Force (the 1st Armored and 34th Infantry Divisions) had been earmarked for an invasion of North Africa, and U.S. construction in Ulster ceased completely.36

Limited though they were in scope, the engineering tasks in Northern Ireland were often difficult to accomplish. The damp, cold weather depressed troops fresh from camps in the southern states, and the men complained about British food. Equally telling were the insufficient, inadequate, and frequently unfamiliar tools. The early period in Northern Ireland was, for the engineers, a time of stumbling forward. Yet worthwhile lessons were learned, especially in planning construction and in establishing a supply system. As valuable

as anything was the day-by-day cooperation with the British.37

The Bolero Plan

Outside of Northern Ireland, the entire engineer force in the British Isles on 1 April 1942 consisted of Maj. Charles H. Bonesteel III, the officer in charge; a lieutenant detailed from the British Army; and two enlisted men on loan from the American embassy. Colonel Davison was still in the United States. A larger engineer buildup awaited fundamental decisions on strategy that would determine troop and support requirements. In April these decisions came, though they were to be changed again in August.

In mid-April 1942, General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, and Harry Hopkins, President Roosevelt’s personal representative, on a special mission in London won British approval of an American plan for a cross-Channel invasion in 1943. Under the original code name BOLERO, the operation was to have three phases—a preparatory buildup in the British Isles, a cross-Channel movement and seizure of beachheads, and finally a general advance into German-occupied Europe. The plan also provided for an emergency invasion of Europe in 1942 if the Germans were critically weakened or if a Soviet collapse seemed imminent. By early July the code name BOLERO had come to designate only the buildup or preparatory phase; the emergency operation in 1942 was designated SLEDGEHAMMER, and the full-scale 1943 invasion was designated ROUNDUP.

BOLERO envisaged the development of the United Kingdom as a massive American base for a future invasion and for an immediate air offensive. It changed the dimensions of the American task in the British Isles and shifted emphasis from Northern Ireland to England. Between April and August 1942 it gave the American buildup purpose and direction, but the original BOLERO concept did not last long enough to permit buildup plans to take final form. In the end neither ROUNDUP nor SLEDGEHAMMER proved feasible. In late July a new strategic decision for an invasion of North Africa (TORCH) made any cross-Channel invasion in 1942 or 1943 all but impossible and placed the BOLERO buildup in limbo. The engineer story in England during spring and summer of 1942 is inextricably tied to the changes in direction that resulted from these strategic decisions.38

At the very least, the BOLERO plan gave impetus to the development of an American planning and support organization in the British Isles and laid the groundwork for the massive buildup for an invasion in 1943-44. As a first step, combined BOLERO committees were established in Washington and London, the task of the London committee being to “prepare plans and make administrative preparations for the reception, accommodation and maintenance of United States forces in the United Kingdom and for the development

of the United Kingdom in accordance with the requirements of the ROUNDUP plan.” During 1942 the committee produced three separate BOLERO troop bases—referred to as key plans—which provided general guides for the buildup, including U.S. Army engineers. The first BOLERO Key Plan appeared on 31 May 1942; a comprehensive revision based on much more detailed studies followed on 25 July; and a third plan was published in late November reflecting the adjustments required by the TORCH decision.39

Each of the plans was based on forecasts of American troops to be sent to the United Kingdom and included estimates of personnel and hospital accommodations, depot storage, and special structures they would require, together with British advice on where the facilities would be found or built. All these plans suffered from the lack of a firm invasion troop basis, a target date, or a specific landing zone, but they did represent tentative bases on which buildup operations could proceed. The original plan brought to London by General Marshall called for thirty U.S. divisions included within a total of about one million men, all to be in the United Kingdom in time for the spring 1943 invasion. The BOLERO Key Plan of 31 May called for 1,049,000 U.S. troops in Britain, but for not nearly so many divisions on account of the need for air and service troops. The second BOLERO Plan of July provided a troop basis of 1,147,000. The third plan in November, reflecting the abandonment of hope for a 1943 invasion, set the short-term goal for April 1943 at 427,000 men, although it optimistically retained the long-term goal of the first plan-1,049,000. As 1942 ended, however, in the face of a continuing drain for the operation in North Africa and an acute shipping shortage, neither the long- nor the short-term goal seemed attainable. BOLERO thus proceeded with uncertainty in 1942 and was subject to constant changes.40

As the central planning agency in the United Kingdom, the BOLERO Combined Committee in London was concerned with high-level policy only. Subcommittees took care of intergovernmental planning for specific tasks such as troop housing, hospitals, and depots. Various permanent British and American agencies in direct cooperation undertook the day-to-day work, and these agencies set up special machinery that dealt with specific problems. To the U.S. Army engineers, the most important British official at this stage of the war was Maj. Gen. Richard M. Wooten, Deputy Quartermaster General (Liaison) of the War Office. Under his command were two sections: a planning group concerned with receiving and housing troops and another dealing with entertainment and morale.41

Most American ground troops were to be stationed in southern England and

were assigned positions in that area (the British Southern Command) west of the principal British forces, for the Continental invasion plan provided that the Americans were to be on the right, the British on the left, when they went ashore in France. This meant that thousands of British troops already on the right would have to move east to new areas. Immediately after publication of the first BOLERO Plan, representatives of the two armies met to plan the necessary transfers.42

But other problems were not so easily settled. Housing standards included such matters as the size, shape, and equipment of structures, materials to be used, and sewage facilities. These difficulties were the product of two different standards of living; Americans were reluctant to accept many standards that seemed to the British entirely adequate. Another problem concerned airfield specifications and materials. These differences surfaced when the British turned over their own accommodations to American forces and drew up plans for new structures. The British view was understandable, for one of BOLERO’S chief aims was to limit new construction and expansion to the barest minimum. Moreover, all the BOLERO installations were to be returned to the British after they had served their purpose for the Americans.

Creation of the Services of Supply BOLERO required a large American military organization to handle the proposed massive buildup in the United Kingdom. On 2 May General Chaney cabled the War Department outlining his own ideas on a Services of Supply (SOS) to be organized for this purpose and requested personnel to man it. He indicated that General Davison was his choice as SOS commander. To head a construction division under Davison, he suggested Col. Thomas B. Larkin or Col. Stanley L. Scott, and his choice for Davison’s successor as chief engineer was Col. William F. Tompkins. But the War Department had its own ideas. General Marshall had already chosen another engineer officer, Maj. Gen. John C. H. Lee, to head the theater SOS, and by 5 May Lee was busily engaged in recruiting an SOS staff in Washington. On 14 May Marshall sent a directive to Chaney stipulating that the organization of the theater SOS was to parallel that of the SOS recently formed under Lt. Gen. Brehon B. Somervell in the United States and was to be given far broader powers than Chaney proposed. The theater headquarters was to retain “a minimum of supply and administrative services” under the SOS.43

General Lee, a strong-minded, even controversial man, entered the theater on 24 May like a whirlwind, determined to carry out the Marshall directive. His approach provoked spirited resistance among General Chaney’s staff, most of whom believed that the theater chiefs of technical services could function properly only if they were directly under the theater commander. Chaney had already established an SOS command

General Lee

in anticipation of General Lee’s arrival. The two officers appeared to have reached agreement on the command during transatlantic telephone conversations in which General Davison took part as well. But after Lee began operations in London on 24 May, it developed that his conception of the scope of his command far exceeded what General Chaney had vaguely staked out for him. As dynamic an organizer as he was a forceful personality, General Lee eventually acquired a special train, which he called “Alive,” to enable him to make quick trips to solve knotty problems and to hold command-level conferences in complete privacy.44

For all his determination and dynamism, General Lee was not to have his way entirely. On 8 June 1942, the War Department formally established the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army (ETOUSA), to succeed the USA-FBI command. General Chaney retained command temporarily but on 24 June was succeeded by Maj. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, also General Marshall’s personal choice. Before Eisenhower’s arrival Chaney had already tried to resolve the jurisdiction of the SOS by a compromise arrangement reflected in ETOUSA Circular 2 of 13 June 1942. Eleven of eighteen theater special staff sections, including all the technical services, were placed under the SOS commander, but he was to carry out his functions “under directives issued

by the theater commander,” and there were other clauses to assure that the theater command retained control of theater-wide functions. The theater staff sections under the SOS were to maintain liaison offices at theater headquarters. The broad grant of authority to General Lee was thus diluted by the dual nature of the relationship of his technical service chiefs to the SOS and to the theater command. The result was a division of supply and administrative functions between the SOS and Headquarters, ETOUSA.

On assuming command, General Eisenhower made only small changes in the arrangement. ETOUSA General Order 19 of 20 July 1942 actually reduced the number of staff sections directly under SOS control, probably the result of the removal of SOS headquarters from London to Cheltenham, physically separating it from ETOUSA headquarters. The engineers, as well as the other technical services, remained under the SOS with their headquarters, in effect, divided between London and Cheltenham. It was, in the words of the theater’s logistical historian, “a compromise solution which ... resulted in the creation of overlapping agencies and much duplication of effort.” If Eisenhower had an impulse to change the arrangement, he was soon absorbed in planning for TORCH, an operation of which he was to be Allied commander, and General Order 19 was to govern SOS-ETOUSA relationships for another year.45

The Engineer Pyramid

Within this framework, the Engineer Service in the ETOUSA finally took shape. When General Lee first began assembling his SOS staff in the United States, he asked General Davison to be his chief engineer. The office Davison was to head really had had its start earlier. In March 1942, while Davison was still in the United States, eight engineer officers and twenty-one enlisted men sailed for Britain to add some flesh to the skeleton force then under Major Bonesteel. Additional personnel came with General Davison when he returned to England in April, and others soon followed. In early June their distribution was uncertain; no one knew how many engineers were to make up the total force in the chiefs office, nor, indeed, whether there was to be one chief engineer.46

Officially, the Engineer Service, SOS, ETOUSA, came into existence on 1 July 1942. The various divisions were set up the next day: Supply, Administration and Personnel, Construction, Quartering, Intelligence, and Operations and Training. (Chart 1) General Davison’s tenure as head of the service ended late in July when General Lee, carrying out a plan to decentralize his command, organized base sections in the United Kingdom and made Davison commanding officer of Western Base Section. Brig. Gen. Thomas B. Larkin (promoted 23 May 1942) then became chief engineer, but was called away in September to plan for TORCH and then to command the SOS to be established in North Africa. Larkin was titular chief

Chart 1 Office of the Chief Engineer, ETOUSA, 1 July 1942

engineer until 2 November, but, in fact, he was replaced on 15 September by Col. (later Maj. Gen.) Cecil R. Moore as acting chief engineer, ETOUSA. With the landings in North Africa, Moore became chief engineer, ETOUSA, on 9 November, and was named to the same job for SOS on 23 November 1942.47

Colonel Moore, widely known as “Dinty,” served as chief engineer until the end of the war in Europe. Born 3 July 1894, Moore entered the Army from Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1917 and served overseas in World War I. The period between the two wars found him active on various dam projects, primarily in the Pacific Northwest where, for a time, he served as the Portland district engineer under General Lee, then chief of the North Pacific Engineer Division. In 1940 he was in charge of the building of camps, depots, and hospitals in the Pacific Northwest, and he left this task to go to the European theater. Arriving in the United Kingdom in July 1942, for some time he did double duty in OCE and as commander of Eastern Base Section.48

During its hectic first months, the Engineer Service, SOS, ETOUSA, was plagued by these rapid changes in leadership, uncertainties about its functions, division of its staff between London and Cheltenham, and continuous personnel shortages. When General Davison took over, he found that an SOS directive placed the engineers, along with the other technical services, under the supervision of G-4, SOS, and that the Requirements Branch of G-4 had responsibility to “prepare policies, plans and directives for the formulation and execution of supply and construction projects in terms of type, quantities, and time schedules.” This function, as far as construction was concerned, seemed to belong rightfully to the chief engineer; but only in December was it officially transferred, although the engineers had long before assumed it in practice.49

The move of SOS to Cheltenham, a famous watering spot in the Gloucestershire countryside some ninety miles west of London, accentuated the difficulties of coordination between theater and SOS engineer sections. The chief engineer and his division chiefs were perforce commuters between Cheltenham and London in their efforts to coordinate work between the two complementary but often overlapping engineer sections. Maintaining two staffs worsened the manpower shortages of the engineer force in the United Kingdom, a force that did not have all its authorized officers until 15 May 1943 and enlisted men until mid-September.50

The shortages affected the progress of all the engineer command’s work. Besides construction, for which American engineers relied so heavily upon the British, the SOS command as of 13 June 1942 was responsible for railroad operations, quartering and utilities, and

General Larkin

for all the boats and landing craft scheduled to arrive with incoming amphibian engineer units. In August the new Transportation Corps (TC) took over the railroads, but the engineers still had too few men to procure fire-fighting equipment for the transportation service, acquire cranes, lumber, and real estate, and build fuel pumping installations. Col. Arthur W. Pence, who had arrived with General Lee to be the deputy chief engineer of SOS ETOUSA found the personnel situation highly confused. He could only commiserate for the moment with General Davison that the twenty officers available for the Office of the Chief Engineer in the Services of Supply command were not enough to do the job.51

Despite personnel and organizational problems during 1942 the engineer parts were gradually building into a working machine, as the development of the “static force,” or regional organization, demonstrated. The need for district organization such as existed in the United States was appreciated by engineer officers—Colonel Pence, for example—even before General Lee had decided to set up such a system. On 9 June General Lee asked the War Department for personnel to make up twelve engineer district offices, and the engineers began to establish such an organization on 3 July. This engineer machinery was absorbed on 20 July by General Lee’s reorganization of the entire SOS. He established four base sections, roughly paralleling a British military division of the United Kingdom. (Map 2) These jurisdictions—the Northern Ireland, Eastern, Western, and Southern Base Sections—were divided into districts which, in turn, were divided into areas. Each organization, from the base section down, had its own engineer.52

General Lee’s aim was to employ the base sections and their subdivisions as instruments of the parent SOS to secure centralized control and decentralized operation of the whole field organization. The base sections became the

Organization of SOS in the United Kingdom, July 1942

offices of record, while the districts were primarily offices of supervision. The base section, district, and area staffs were known as the static force, and each worked in close liaison with its local counterpart in the British Army. Two of the four base section commanders first appointed by General Lee–General Davison and Colonel Moore—were engineers.53

The base section engineer was not only a member of the base section commander’s special staff but was also the representative with the base section of the chief engineer, SOS. This created a difficult problem: the division of authority between the chief engineer and the base section commander. When the field system came into being, “technical control” was reserved to the chief of each service, but the concept was so vague that it satisfied no one. For months, the matter troubled the entire SOS organization, and it was never completely settled. In August Headquarters, SOS, attempted to clarify the situation for the engineers. New construction and base repair shops were removed from the base section commanders’ jurisdiction, and Colonel Moore, chief engineer, obtained authority to deal directly with his representatives in the base sections on these matters. Nevertheless, the engineers were told to keep the base section commanders informed concerning progress. Although on paper Colonel Moore had direct authority over new construction, in practice both he and the base section commanders expected the base section engineers to assume responsibility; leaving a large measure of authority to these subordinate officers made it possible to avoid controversy.54

Roundup Planning

In addition to organizing a base in the United Kingdom for an Allied invasion of the Continent, it was necessary to plan for the operation itself. A ROUNDUP Administrative Planning Staff was set up for joint planning, holding its first meeting on 29 May 1942. Of the forty original sections, several were of special concern to the engineers: port salvage and repair, development of communication lines, shops and utilities, water supply, bridging, and construction and maintenance of airfields. A U.S. Joint Staff Planners decision on the jurisdiction over landing craft also made the engineers in the theater responsible for training boat crews for amphibious operations in Europe.55

As deputy chief engineer at Headquarters, ETOUSA, Col. Elmer E. Barnes headed the engineer planners for ROUNDUP; it was July before he obtained even a limited number of officers for his staff. While chiefly concerned with ROUNDUP planning, Barnes’ organization also maintained contact with the British on all engineer matters, prepared studies on construction requirements for the Construction Division of OCE, SOS, and maintained

liaison with the Operations and Training and Supply Divisions of OCE, SOS. Finally, Barnes’ office coordinated engineer activities with other arms and services represented at ETOUSA headquarters in London.56

Colonel Barnes and his subordinates faced a chronic shortage of officers and the lack of a basic operational plan for ROUNDUP in 1942. The engineer section at Headquarters, ETOUSA, unavoidably lost time and wasted effort because everything had to be referred for approval to OCE, SOS, at Cheltenham. For example, the officer dealing with expected construction requirements on the Continent after the invasion would have to send his plan and estimates to Cheltenham for approval and suggestions, wait for the revision, and then return his second draft for final approval.57

When TORCH preparations went into full swing, ROUNDUP planning was virtually shelved, to be taken up again as circumstances permitted. Key personnel were assigned to the North African invasion, and a Pentagon directive of 18 November that prohibited stockpiling of supplies and equipment for ROUNDUP beyond that required for the 427,000-man force further handicapped Barnes. The British, who insisted on going on with their ROUNDUP planning, wanted to continue stockpiling standardized supplies to be used by British and American forces. In one case they tried to obtain a particular item of petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL) equipment from the United States, but because of the new American policy they had to continue manufacturing and using their own product.58

G-4, ETOUSA, continued a semblance of planning by requiring from each of the services a maintenance program for a theoretical Continental operation. The engineers also prepared their part of an invasion plan, an exercise that eventually proved its value in helping to determine the necessary engineer nonstandard heavy construction—Class IV—supplies and the adequacy of the engineer troop basis.59

As important as any aspect of this work was the experience gained in working with the British. Estimating requirements, for example, led to the establishment of a joint stockpile which cut down duplication and made supply facilities more flexible. The tremendous tonnages involved and the long periods required for production made the importance of the joint stockpile apparent. Close liaison also promoted standardization of equipment. For example, the U.S. Army in December 1942 requisitioned from the British ROUNDUP stocks 20,000 standard 16-foot-wide

Nissen huts, 6 million square feet of 24-foot-wide Nissen hutting, 2,000 Bailey bridges, 25 million sandbags, large quantities of barbed wire, and other supplies. These requisitions were “on paper” for future delivery and represented a part of planning for the actual invasion. In road and general construction, where the problems were more or less peculiar to each force, joint action extended only to the standardization of materials. In addition to its other benefits, standardization in any form tends to reduce costs. The good relations established at planning meetings were of incalculable importance for the future.60

In connection with POL distribution, port reconstruction, and beach and port operations, the engineers in the various ROUNDUP administrative planning sections in 1942 accomplished worthwhile planning. Less was achieved in regard to water supply and amphibious operations, little on bridging problems, and almost nothing on airfield construction and maintenance.61

When OCE, ETOUSA, conducted a drastic self-examination in the fall and winter of 1942, it discovered that SOS personnel concerned themselves too much with matters in which they should not have been involved beyond coordinating details after receiving broad operational plans from London. The ETOUSA section was further embarrassed by difficulty in securing well-qualified personnel, probably because current needs, especially for construction, seemed much more important than rather indefinite planning for ROUNDUP. These were not the criticisms of Barnes alone, but also of other important officials at SOS headquarters.62

In the meantime, through the last few months of 1942, Colonel Barnes’ group broadened its field, not only in planning for the future, but also in presenting the SOS and ETOUSA engineer view on any new procedures adopted in the theater. Finally, in November, Col. Royal B. Lord, then chief of the Operations and Training Division, declared that “the time has arrived to put all planning under Colonel Barnes.”63

Near the end of 1942, most officers in OCE could agree that the rather artificial separation of ETOUSA and SOS headquarters impeded efficient operations.64 Yet despite the problem of the drain that TORCH imposed on engineer personnel and resources in the United Kingdom, by the end of the year very real progress had been made in building an organization that would play an important role in preparing for the cross-Channel invasion in 1943 and 1944. Although many problems were left unsolved, the machinery for the buildup to come was put together in

the spring and slimmer of 1942. Repeated changes in SOS and engineer troop allotments upset planning, but the organization, hurriedly assembled in a strange land under the stress of war, worked reasonably well in carrying out a quartering and construction program across the British Isles.