Chapter 9: The Winter Line and the Anzio Beachhead

The region of Fifth Army operations during the winter of 1943-44 was admirably suited for stubborn defense. Its topography included the narrow valleys of rivers rising in the Apennines and emptying into the Tyrrhenian Sea, irregular mountain and hill systems, and a narrow coastal plain. The divide between the Volturno–Calore and the Garigliano–Rapido valleys consisted of mountains extending from the crest of the Apennines southward about forty miles, averaging some 3,000 feet above sea level and traversed by few roads or trails. The slopes rising from the river valleys were often precipitous and forested, and all the rivers were swollen by winter rains and melting snow. In these mountains and valleys north and west of the Volturno, German delaying tactics slowed and finally halted Fifth Army’s progress. The engineers had to fight enemy mines and demolitions as well as mountains and flooded streams.

Before the Allies launched an attack on the Winter Line on 1 December 1943, the U.S. II Corps took its place in the Fifth Army center near Mignano. The British 10 Corps and U.S. VI Corps occupied the left and right flanks, respectively. Early in January VI Corps withdrew from the Fifth Army front to prepare for the Anzio operation, and the French Expeditionary Corps (FEC), initially consisting of two divisions from North Africa, took its place. A number of Italian units, including engineers, also joined Fifth Army. But these additions did not assure rapid progress. The army pushed slowly and painfully through the mountains until it came to a halt in mid-January at the enemy’s next prepared defenses, the Gustav Line, which followed the courses of the Rapido and Garigliano Rivers for most of its length. Opposing Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army was the German Tenth Army.1

In January Fifth Army attacked on two fronts. VI Corps’ surprise flank attack in the Anzio landing (SHINGLE) of 22 January penetrated inland an average of ten miles, but then the German Fourteenth Army contained the beachhead, and for the remainder of the winter VI Corps was on the defensive. In the mountains to the south Fifth Army could gain little ground. When an attack began on 17 January, II Corps held the Fifth Army center along the Rapido and tried repeatedly to smash through the Gustav Line. By the thirty-first II Corps had penetrated some German lines but failed to capture Cassino, key to enemy defenses. The opening of the second front at Anzio had reduced the

length of the inland front Fifth Army could hold; hence, in February three divisions moved from Eighth Army to take over the Cassino-Rapido front while Fifth Army units concentrated in the southern half of the line, along the Garigliano. Despite heavy casualties, the gains in the winter campaign were negligible, and a stalemate existed until the offensive resumed in the spring.

Minefields in the Mountains

Approaching the Volturno, the Allies had run into increasingly dense and systematic minefields which included unfamiliar varieties of mines and booby traps. The German mine arsenal in Italy contained the “S” (or “Bouncing Betty”) and Teller plus many new types including the Schu and the Stock, mines with detonations delayed up to twenty-one days, and mines with improvised charges. Nonmetallic materials such as wood and concrete in many of the newer mines made detection more difficult and more dangerous.

Allied troops dreaded the Schu mine especially. Approximately 6-by-4-by-2 inches, this mine consisted of a ½- to 2-pound block of explosive and a simple detonating device enclosed in lightweight pressed board or impregnated plywood. It could be carried by any foot soldier and planted easily in great numbers; it was most effective placed flush with the ground and covered with a light layer of dirt, grass, and leaves. The Schu did not kill, but as little as five pounds of pressure would set it off to shatter foot, ankle, and shin bones.

At the Volturno the enemy had recovered from the confusion of retreat, and to the end of the Italian campaign each successive German fortified line had its elaborate mine defenses. The Germans frequently sowed mines without pattern and used many confusing methods. Distances, depths, and types varied. A mine might be planted above another of the same or different type in case a mine-lifting party cleared only the top layer.

The scale of antipersonnel mining increased as the campaign progressed. Booby traps were planted in bunches of grapes, in fruit and olive trees, in haystacks, at roadblocks, among felled trees, along hedges and walls, in ravines, valleys, hillsides, and terraces, along the beds and banks of streams, in tire or cart tracks along any likely avenue of approach, in possible bivouac areas, in buildings that troops might be expected to enter, and in shell or bomb craters where soldiers might take refuge. The Germans placed mines in ballast under railroad tracks, in tunnels, at fords, on bridges, on road shoulders, in pits, in repaired pot holes, and-in debris. Field glasses, Luger pistols, wallets, and pencils were booby-trapped, as were chocolate bars, soap, windows, doors, furniture, toilets, demolished German equipment, even bodies of Allied and German civilians and soldiers.2

In areas sown with S-mines bulldozer operators wore body armor, and each combat battalion had four “flak” suits. More than fifty bulldozers struck mines during the campaign. In many cases the operators were thrown from their seats, but none was killed. Some had broken legs, but had they been in cabs with roofs many would have had their necks broken or skulls fractured.3

Although detecting and clearing mines was not exclusively an engineer function, the engineers were primarily responsible. But they were not adequately trained. As late as September 1944 engineers in the field complained that no organization or procedure had been established for collecting enemy mines for training.4

Infantrymen retained the dread of mines that had been so marked in North Africa. To ease that dread and to pass on proper procedures for lifting mines, the engineers emphasized that mines were one of the normal risks of war; only one man should deal with a mine; skilled help should be called in when needed; ground should be checked carefully in a mined area; all roads and shoulders should be cleared and accurate records made of such work, with roads and lanes not cleared being blocked off and so reported; and large minefields should not be cleared except on direct orders.5

The engineers often found that infantrymen did not comprehend the time required to check an area. Checking and clearing mines were slow and careful processes, requiring many men and involving great risks even when there was no enemy fire. For example, the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion in the Formia–Gaeta area, north of Naples, suffered fifty-seven casualties, including fifteen deaths, in clearing 20,000 mines of all types during a period of sixteen days. Often a large area contained only a few mines, but the number found bore little relation to the time that had to be spent checking and clearing. Furthermore, much of the work had to be done under artillery, machine gun, and mortar fire. Ordinarily the infantry attacked with engineers in support to clear mine paths, and engineer casualties were inevitable.6

New problems in mine detection arose during the Italian campaign. With the increasing number of nonmetallic enemy mines, the SCR-625 detector became less dependable and the prod more important. Italian soil contained heavy mineral deposits and large concentrations of artifacts buried over the ages.7 A detector valuable in one spot might be useless a mile away, where the metallic content of the soil itself produced in the instrument a hum indistinguishable from that caused by mines. Shell fragments and other scraps of metal scattered in many areas caused the same confusion.

The wooden Schu mine was difficult for the SCR-625 to spot. Since the fuse was the only metal in the mine, the detector had to be carefully tuned and the operator particularly alert. The prod was a surer instrument than the detector in this work, but it had to be held carefully at a thirty-degree angle to avoid activating the mine. The Schu charges were too small to damage bulldozers seriously, but ordinarily the Germans placed these mines in areas inaccessible to bulldozers. However, Schu mines in open fields or along paths were often interspersed with S-mines, which could be costly to bulldozers and operators. One solution was to send sheep or goats into the minefield to hit trip wires and detonate the mines.8

The fact that the SCR-625s were not waterproof continued to limit their usefulness. They had difficulty finding mines buried in snow, and any lengthy rain usually rendered them useless. However, covering the detector with a gas cape protected it somewhat against rain and snow. The 10th Engineer Combat Battalion (3rd Division) had as many as ninety detectors on hand at one time, but at times most were unserviceable. Its use was limited near the front, because the enemy often could hear the detector’s hum, especially at night when much of the work was done and when the front lines were comparatively quiet.9

The engineers tried out new types of detectors at various times. The Fifth Army received the AN/PRS–1 (Dinah) detector in August 1944. It was less sensitive than the SCR-625 and in a seven-day test proved not worthwhile. A vehicular detector, the AN/VRS–1, mounted in a jeep, was also tested and rejected as undependable.

Of numerous other countermine devices and procedures tried, a few proved useful. The best of these were primacord ropes and cables. The 48th Engineer Combat Battalion developed a simple device for clearing antipersonnel mines—a rifle grenade that propelled a length of primacord across a minefield. The exploded primacord left a well-defined path about eighteen inches wide, cutting nearly all taut trip wires and sometimes detonating Schu mines. In all cases the engineers cleared the ground of any growth or underbrush to reveal mines or trip wires.

On the Cisterna front, fifteen miles northeast of Anzio, the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion used six Snakes to advantage when the Allies broke out of their perimeter. Segments of explosive-filled pipe that could be assembled into lengths up to 400 feet, the Snakes threw the enemy into momentary panic and permitted Combat Command A (CCA), 1st Armored Division to advance; Combat Command B, which did not use the devices lost a number of tanks in its breakout. In practice, the Snakes were effective only over flat, heavily mined ground. They were susceptible to rain and mud, slow to build, difficult to transport and vulnerable to artillery fire and mine detonations.10

Other devices and methods for finding and removing mines in Italy included aerial detection—especially valuable along the Garigliano River and at Anzio—D-7 bulldozers with rollers, bazooka shells, bangalore torpedoes, and grappling hooks that activated antipersonnel mine trip wires.11

Bridge Building and Road Work

In the winter campaign, the steel treadway and the Bailey (fixed and floating) were the tactical bridges the engineers used most, and the Bailey proved the more valuable. In the opinion of the Fifth Army engineer, it was “the most useful all-purpose fixed bridge in existence.” Its capacity and length could be increased speedily by adding trusses and piers. It could be used where other bridges could not, particularly over mountain streams where flash floods quickly washed out other temporary bridges. There were never enough

Baileys. An early attempt to supplement the British supply with Baileys manufactured in America failed. The engineering gauges sent from England to American factories were improperly calibrated, and the sections that came to Italy from the United States were incompatible with the British-manufactured parts in use; bridges assembled from American parts would not slide as well as the British bridges. Upon discovering the discrepancies, General Bowman outlawed the American bridge sets in the Fifth Army area.12 Tread-ways, both floating and trestle, were almost as well suited to Italian conditions as Baileys, but the constant shortage of Brockway trucks needed to haul them limited their usefulness. The tread-ways were too narrow to accommodate large equipment carriers such as tank transporters and heavy tanks.13

The engineers of Fifth Army erected many timber bridges, usually as replacements for Baileys or treadways. The timber structures could carry loads of over seventy tons. Made not to standard dimensions but to the needs of the moment, they consisted ordinarily of a series of steel or timber stringer spans with piers of single or double pile bents. The acquisition of the Ilva Steel Works at Bagnoli, after Naples fell, increased the use of steel stringers. Timber floor beams or steel channels rested on the stringers and supported wood decking of two layers, the upper laid diagonally to decrease wear. From the Ilva steel mill also came a light, steel-riveted lattice-type girder, suitable for semi-permanent bridges, which became standard equipment.14

When Fifth Army engineers had to build abutments, they usually spiked logs together to make hollow cribs and then filled the cribs with stone. They had learned through experience that a dirt-fill abutment that extended into the channel restricted normal stream flow, which, in turn, scoured the abutment. Abutments needed to be well cribbed, and timber was the best expedient.

During the winter campaign the engineers devised new methods and new uses for equipment in bridge building. The 16th Armored Engineer Battalion claimed credit for first putting cranes on the fronts of tanks or tank-recovery vehicles to get various types of treadway bridges across small streams or dry creek beds; the cranes enabled engineers to install bridges under heavy enemy fire. When a treadway across the Volturno at Dragoni almost washed away in November 1943, a company of the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment anchored it with half-track winches. On the night of 15 November the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion used the winches of Brockway trucks as hold-fasts to save another bridge at Dragoni. Engineers saved time by building Baileys with raised ramps on each end to put the bridge roadway two to three feet above the normal elevation. They could then build a more permanent bridge directly under the Bailey without closing the bridge to traffic and could quickly lay the flooring and wearing surface of the new bridge after they removed the Bailey.15

Bridge companies were in short supply throughout the Italian campaign, and for a time the treadway company of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion was the only bridge company in Fifth Army. The companies were needed not only to construct, maintain, and dismantle bridges but also to carry bridge components. The treadway company of the 16th served as a bridge train from the first but could not meet the demand. As a stop-gap measure two companies of the 175th Engineer General Service Regiment were equipped with enough trucks (2½-ton and Brockway) to form bridge trains, and later two more bridge train companies were organized from the disbanded bridge train of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion. In addition, Fifth Army from time to time employed bridge companies of 10 Corps for bridge trains. Elements of the 1554th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion and Companies A and C of the 387th Engineer Battalion (Separate) also served as bridge train units. The main problem all units converting to bridge trains faced was to find experienced, reliable drivers for their trucks.

Such was not the case for the 85th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion, which could unload its ponton equipment and, by carefully reloading, handle Bailey bridge components. One company of the 85th could carry two standard Baileys, and the ponton trailers also hauled piling and steel beams to engineer units replacing temporary bridging. One problem remained—the large, ungainly trailers could not traverse many Italian roads.

Since the speed with which wrecked bridges were rebuilt or replaced often determined the Fifth Army’s rate of advance, much of the bridge equipment had to be kept on wheels. Some equipment, such as Brockway trucks, was always in short supply. In the latter part of October 1943 the 85th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion established a bridge depot near Triflisco, operating directly under the Fifth Army engineer and sending bridging to the corps on bridge trains. It was a tactical depot, with stocks kept to a minimum for quick movement. The depot stocked fixed and floating Baileys, steel treadways, infantry support and heavy ponton bridges, and other stream-crossing equipment. Tactical Bailey and tread-way bridges replaced with fixed bridges were returned to the army bridge depot, where they were reconditioned and put back in stock.16

In reconnoitering for bridge sites, an important engineer function, experienced photo interpreters, studying aerial photographs of the front lines, were able to save much time. During the stalemate before Cassino, Lt. Col. John G. Todd, chief of the Mapping and Intelligence Section; Col. Harry 0. Paxson, deputy Fifth Army engineer; and Capt. A. Colvocoresses worked out a plan to use aerial photos for engineer reconnaissance. One officer and one enlisted man specially trained in photo interpretation remained at the airfield where the photos were processed, and they could obtain copies of all aerial photos taken in front of the American lines. Those covering the front to a depth of ten miles went forward immediately to the Engineer Section, Fifth Army, and there Captain Colvocoresses recorded on a map everything that might help or hinder Fifth Army’s advance:

locations, characteristics, and dimensions of all bridges; possible bridge or crossing sites; places along roads where enemy demolitions could cause serious delays; locations of enemy dumps; and marshy ground that could prohibit tanks. This information Colvocoresses sent to the army G-3 and the army engineer’s operations and supply sections. Meanwhile, the officer and the enlisted man at the airfield did the same type of work for the area beyond the ten miles in front of the lines, though in much less detail. As another result of the photo-interpretation process, Colonel Paxson represented the Fifth Army engineer on the target selection board for heavy artillery.

Aerial photographs helped planners to estimate the material, equipment, and troops needed for bridge work. Information on blown bridges went back to the engineer supply section at army headquarters and forward to the frontline troops, who could prepare for necessary repairs. Engineers could then have the bridging on hand when an attack went forward. Aerial photographs were especially important where enemy fire forestalled close ground reconnaissance.

Building bridges under fire was difficult at best—sometimes impossible. But engineers did build bridges under withering fire. In December 1943 Company H, 36th Engineer Combat Regiment, put a Bailey across a tributary of the Volturno, a few miles to the west of Colli al Volturno, and in February 1944 the 109th Engineer Combat Battalion bridged the Rapido in two hours.

Some engineers built bridges at night to escape enemy fire. Insofar as possible they put material together somewhat to the rear and brought forward partially prefabricated bridges in the dark. Others, trusting to Allied air superiority, preferred to build bridges by daylight under the protection of counterbattery fire that aerial reconnaissance directed. Another protective device was a dummy bridge to draw fire away from the real site.17

Winds and floods caused havoc. On 30 December a company of the 344th Engineer General Service Regiment was building a Bailey across the Volturno near Raviscanina. While the engineers were putting concrete caps on the stone piers of the demolished span, a high wall of water plunged down the river, quickly washing away concrete and equipment. On the thirty-first high winds and subfreezing temperatures ended all work for several days. The gale ripped down company tents and blew away, buried, or destroyed personal equipment.18

During the winter campaign divisional engineers worked rapidly to clear rubble-clogged village streets, remove roadblocks and abatis, and fill cratered roadways to take one-way traffic. Sometimes they built roads over demolitions instead of clearing them. On several occasions they used railbeds cleared of ties and rails as emergency roads. In December 1943 the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion built one such road at the Cassino front under artillery fire. The battalion suffered many casualties while extending the road for six miles from Mignano to the flank of Monte Lungo and on to a point 200 yards in advance of infantry outposts.19

Corps engineers normally followed divisional engineers to widen one-lane roads and bypasses for a freer flow of traffic, finish clearing rubble, remove debris from road shoulders, eliminate one-way bottlenecks, check each side of the road for mines, post caution and directional signs, and open lateral roads. Fifth Army engineers finished filling craters and resurfaced and widened roads to take two-way traffic.

The policy was for divisional engineers to concentrate on the immediate front; they could ask corps engineers to take over any other necessary work in the division area. Similarly, as corps engineers took over work in the divisional areas they could ask army engineers to take over work in the corps areas. These requests were never turned down, although there were some complaints of work unfinished in the army area. The system worked better than retaining specified boundaries and continually shifting engineer units among division, corps, and army as the work load varied.

Much road repair and construction—especially that undertaken by division and corps engineers—was done under heavy enemy artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire. At times, engineer troops had to slow or even stop work because of enemy fire or had to abandon one route for another. Such experiences gave rise to engineer complaints of lack of infantry support, and frequently the engineers provided their own protection, especially for dozer operators. Avoiding enemy fire by working at night had serious drawbacks, especially in the mountains. Only the most skilled graders and dozer operators could feel their way in the dark. Also, the noise of the equipment often drew enemy fire, even through the smoke screens that provided protection. The engineers set smoke screens for themselves, with varying success, and on numerous occasions Chemical Warfare Service units furnished excellent screens.

The engineers had to contend not only with the enemy but also with heavy snows, mountain streams that rains turned into raging torrents, water pouring into drainage ditches from innumerable gullies and gorges, and tons of mud clogging ditches and covering road surfaces. At times, engineers worked waist deep in mud. Army vehicles hauled huge quantities from side roads and bivouacs. The only answer was “rock, plenty of rock.”20

For proper drainage crushed rock or gravel, or both, had to cover the whole surface of a road, and the crown had to be maintained. When engineer units assumed responsibility for a new area one of the first things they did was to find a ready and reliable source of rock and gravel. In most parts of Italy supplies were plentiful. Rubble from demolished stone houses—even Carrara marble quarried from the mountainsides—supplemented rock.

Quarries sometimes operated day and night. In December 1943 a 235th Engineer Combat Battalion quarry on Highway 6 east of Cassino worked twenty-two hours a day, lit at night by giant torches “after the fashion of a Roman festival in Caesar’s time,” though “the torches attracted a not inconsiderable amount of attention from German planes and artillery.”21 The engineers dumped and roughly spread rock; then Italian laborers used sledges or small

portable rock crushers to break up the larger stones.22

Engineers drained water from the wide shoulders along secondary roads by digging ditches across the shoulders at intervals or by using various types of culverts. Steel pipe culverts of twelve-inch diameter worked effectively, and the engineers had little difficulty finding local pipe for them. Curved sheets of corrugated iron made excellent forms for masonry culverts. During the fighting at the Winter Line, Lt. Col. Frank J. Polich of the 235th Engineer Combat Battalion designed a prefabricated hexagonal culvert. Sixteen feet long with two-foot sides and steel reinforcements, it was intended for emergency jobs but proved so successful that Fifth Army adopted it as a standard engineer item. The culvert could be thrown into gaps in the road at the site of a blown bridge, over a bomb crater, or at assault stream crossings to make a passable one-way road. The culvert sustained the weight of 32-ton medium tanks without any earth covering yet could be loaded and transported comparatively easily; it weighed two to three thousand pounds depending upon the kind of wood used in its construction. Other engineer units built similar culverts of varying lengths.23

Of the roads leading forward to the area of the Winter Line campaign, only three were first-class: Highways 7, 6, and 85. As a result, Fifth Army had to depend on unsurfaced secondary roads and on tracks and trails. While the engineers’ main problem during this period was maintenance (the VI Corps engineer, for instance, reported that the 36th and 39th Engineer Combat Regiments devoted almost all their time in December to revetments and drainage control), they built numerous jeep and foot trails through the mountains to supplement the inadequate road system.24

A very large part of VI Corps’ traffic passed through Venafro, a bottleneck through which an average of 4,000 vehicles moved every day during December 1943. To lighten the load on Highway 85 and a narrow road to Pozzilli, the 120th Engineer Combat Battalion, 45th Division, built two additional roads from Venafro to Pozzilli. The engineers eventually extended these roads beyond Pozzilli well into the mountains, where mules or men with pack-boards had to take over.25

Engineers in Combat

In the midst of helping combat troops move over difficult terrain in winter weather, engineers sometimes fought as infantry during the drive on Rome. Perhaps the most spectacular instance was the commitment of II Corps’ 48th Engineer Combat Battalion at Monte Porchia during the first week of January 1944.

Although Monte Porchia was not a primary objective for II Corps, it was needed to protect 10 Corps’ right flank in a projected operation to cross the Garigliano. A small elevation compared with the mountainous terrain generally typical of central Italy, Monte Porchia’s isolated position commanded low ground lying between the Monte Maggiore—Camino hill mass to the south

Engineer rock quarry near Mignano

and Monte Trocchio to the northwest. From this observation point the enemy could survey the Allied line along the Garigliano. The British 10 Corps held the Allied left, while the U.S. 34th Division was in the mountains to the right. In the center, astride the only two roads into Cassino, the U.S. 1st Armored Division had massed Task Force Allen and its attached units. Enemy observation posts on Monte Porchia were able to direct punishing fire on all Allied installations in the valley. It was vitally important to take this hill, and at 1930 on 4 January the attack began.

The weather was cold, wet, and windy. The 6th Armored Infantry Regiment led off, but German mortar and artillery fire was so concentrated that by daylight the 2nd Battalion of the 6th Armored was back at its starting point. More wind-driven snow fell on 5 January as the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion was attached to Task Force Allen, placed in reserve, and told to be ready to go into the line. During 7-9 January, in three days and two nights, when a gap developed on the left flank of the task force, Companies A, B, and C of the 48th went forward. They helped secure the flank and drive the enemy off. For its work in this action the 48th received a Presidential Unit Citation, as did the 235th Engineer Combat Battalion, which also took part in the engagement. Individual awards to men

of the 48th included 3 Distinguished Service Crosses, 21 Silver Stars, and 2 Bronze Stars. The highest award, the Congressional Medal of Honor, was awarded posthumously to Sgt. Joseph C. Specker, Company C, for his bravery on 7 January in wiping out an enemy machine-gun nest single handedly despite severe wounds.26

The 235th Battalion was to open and maintain axial supply routes for Task Force Allen. The work of the battalion, often under heavy fire, enabled armor to move forward in support of the infantry. The 235th also fought as infantry, twice driving the enemy from strongly fortified positions to clear routes for the armor.27

At Cassino: 20-29 January 1944

In mid-January Fifth Army reached the enemy’s Rapido-Garigliano defenses. The removal of VI Corps from the Allied line left II Corps as the only U.S. Army corps on this front. For the assault against the Gustav Line, II Corps was in the center, opposite the Germans’ strong position at Cassino. Plans for the attack called first for the 36th Division to cross the Rapido south of Cassino.

The 36th began the operation late on 20 January. The enemy’s defenses were formidable and his position very strong. Along that part of its course in the division’s sector the Rapido was a narrow stream flowing swiftly between steep banks, in places no more than twenty-five feet wide and elsewhere about fifty. The Sant’ Angelo bluff or promontory, from which the enemy could survey the immediate area, rose forty feet above the river’s west bank, but there were no comparable vantage points east of the river. Between 20 and 22 January the 36th Division made two attempts to establish a bridgehead but suffered a costly defeat. The 36th then went on the defensive while the 34th Division between 26 and 29 January pushed across the Rapido north of Cassino and made a slight but important breach in the Gustav Line.28

During these attacks engineers were to clear mines at crossing sites, build and maintain bridges and bridge approaches, and find and maintain tank routes. They also were to maintain roads and clear mines in seized bridgeheads. The 36th Division’s 143rd Infantry was to attack south of Sant’ Angelo, and its 141st was to cross north of the bluff. The 111th Engineer Combat Battalion, reinforced by two companies of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, was to clear enemy mines before the crossings. During the night of 19 January the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 19th Engineer Combat Regiment, a II Corps unit, were to spot footbridge equipment and assault boats for the attack. The 1st Battalion, during the night of 20 January, was to build an eight-ton infantry support bridge in the area of the 143rd and the 2nd Battalion a similar structure in the attack zone of the 141st.29

The Gustav Line was heavily mined, with box mines notably more numerous. At the Rapido the Fifth Army encountered a mine belt a mile in length, chiefly of the S, Teller, and wooden box types. German patrols interrupted mine clearing, and they crossed the

river and emplaced more mines so that markers indicating the safe passage meant little. Poor reconnaissance resulted partly from the position of the infantry which was 500 yards from the river. When the 141st began to advance, the lanes were difficult or impossible to follow because of heavy fog or because much of the white tape had been destroyed, some by German fire.30

The enemy met the several attempted crossings with intense and continuous artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire, which destroyed assault boats and frustrated the engineers in their attempts to build floating footbridges. The engineers had no standard floating bridge equipment and had to improvise all footbridges over the Rapido. In the 141st Infantry zone artillery fire tore to shreds several footbridges made from sections of catwalk placed over pneumatic boats, while floating mines destroyed another. Most of Companies A and B of the 141st got across on one intact footbridge that the 19th Engineers had managed to put together from the remnants of others. This bridge, although almost totally submerged, remained usable for a time because the engineers strung four ropes across the Rapido to form a suspension cable that supported the punctured boats.31

Dense fog hampered the whole operation, but the 1st Battalion, 19th Engineers, was able to guide troops of the 1st Battalion of the 143rd Infantry through the minefields. By 0500 on 21 January, the 19th Engineers had installed two footbridges in the 143rd’s area south of Sant’ Angelo, but one was soon destroyed and the other damaged. The infantry battalion nevertheless crossed in boats or over the bridges but suffered heavy casualties, and its remnants had to return to the east bank to escape annihilation. Fog confused troops of the 19th Engineers who led the boat group of the 3rd Battalion of the 143rd Infantry. The engineers and infantry stumbled into a minefield, where their rubber boats were destroyed. Enemy fire completed the disorganization of the infantry battalion and defeated its attempt to make a crossing.

During the 36th Division’s second attempt to break through the enemy line the 19th Engineers succeeded in installing several footbridges, but the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion, in the face of artillery and mortar fire, could make no headway with the installation of a Bailey. The action ended in defeat.32

Reviewing the failure to build the Rapido bridges as planned, Colonel Bowman pointed out that the near shore of the river was never entirely under Fifth Army control, so reconnaissance, mine clearance, and approach preparation were incomplete. He concluded that the attempt to build and use a Bailey as an assault bridge was unjustified. Some engineer officers on the scene blamed a shortage in bridge equipment, bad timing, and one infantry regiment’s lack of training with the engineers supporting it. Others claimed that the terrible raking fire from well-placed artillery and small arms directly on the sites made bridge construction all but impossible.

The success of the 34th Division’s Rapido crossing north of Cassino depended

greatly on getting tanks over narrow muddy roads and then across the river. The crossing itself was less a problem than that to the south because terrain and other factors were more favorable. The Germans had diverted the Rapido and flooded the small valley; now the American engineers prepared the dry riverbed for a tank crossing. On the morning of 27 January, after artillery preparation, tanks of the 756th Tank Battalion led the attack. Some of them slipped off the flooded trail and others stuck in the mud, but a few got across the river.33

Engineers of the 1108th Engineer Combat Group and two companies of the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion started building a corduroy route south of the tank trail. On that day and the twenty-eighth the infantry was able to hold some ground west of the Rapido. Meanwhile, the engineers worked to improve the tank routes. The attack against enemy strongpoints resumed on the morning of the twenty-ninth. By that time the engineers had tank routes ready for the advance, and the infantry, aided by armor, captured two strong-points on 30 January. Next day the infantrymen took Cairo village, headquarters of an enemy regiment. After the 34th Division had broken through the enemy’s outpost line and occupied a hill mass north of Cassino, the 109th Engineer Combat Battalion improved a main supply route by constructing two one-way roads that led across the Rapido from San Pietro to Cairo.34

Anzio

To the north, the landing at Anzio (SHINGLE) was under way. Planning and training were compressed into little more than two months. In mid-November 1943 a planning group with three engineer representatives assembled at Fifth Army headquarters in Caserta. Here Colonel Bowman, having reviewed the findings of engineer aerial photo interpreters and having studied harbors from Gaeta to Civitavecchia, recommended Anzio for the projected landing of an Allied flanking force. Col. Harry O. Paxson, the Fifth Army Engineer Section’s expert on evaluating topographic intelligence, also had a part in choosing Anzio. As General Eisenhower’s topographic intelligence officer at AFHQ in 1942 he had learned from the British a method of analyzing offshore terrain that enabled him and others to find an opening in the submerged sandbars off the coast at Anzio.

AFHQ based the final decision to land at Anzio on the existence of suitable beach exits and good roads leading twenty miles to the Alban Hills, a mountain mass rising across the approaches from the south to Rome and affording access to the upper end of the Liri valley. Here was a possibility of cutting off German forces concentrated on the Cassino front. At the very least, AFHQ hoped that a flanking operation at this point, as part of a great pincer movement, would force an enemy withdrawal northward and that Rome would fall quickly into Allied hands.35

Beginning on 4 January near Naples, VI Corps underwent intensive amphibious training which culminated in a practice landing below Salerno. Early on 21 January over 250 ships carrying nearly 50,000 men moved out of Naples.

To keep the enemy from suspecting its destination and to avoid minefields, the convoy veered to the south on a wide sweep around Capri. After dark it turned toward Anzio and dropped anchor just past midnight. The enemy was caught almost completely off guard, and the Allies met only token coast defenses. The Germans had been aware of Anzio’s possibilities as a landing beach but had weakened defenses there in order to hold the Cassino front.36

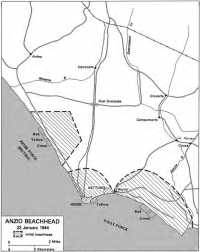

Good weather and a calm sea favored the operation. The landings began promptly at H-hour, 0200, 22 January, and went rapidly and efficiently. (Map 9) U.S. troops’(X-Ray Force) went ashore over beaches south of Nettuno, a few miles southeast of Anzio, and over Yellow Beach, near Anzio. The port fell quickly. Meanwhile, the British (Peter Force) landed six miles north of Anzio. The smoothness and dispatch that marked the U.S. 3rd Division landing and the rapid organization of the beaches was helped by the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment’s experience in beach operations. By daylight the beaches were ready to receive vehicles. In addition to the 540th, beach troops included the 1st Naval Beach Battalion, the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment at the port, and the British 3rd Beach Group on the Peter beaches. All were under Col. William N. Thomas, Jr., VI Corps engineer.37

All assault troops from LCVPs and LCTs debarked on the beaches on schedule. The port of Anzio was taken almost intact, and by early afternoon the 36th Engineers had cleared it sufficiently to receive landing craft. Except for a brief period on D-day, the beaches were never congested. Excellent 1:10,000 scale beach maps, distributed at the beachhead by the 1710th Engineer Map Depot Detachment, helped avoid confusion. Beach crews with attached service units reported directly to assigned areas and began organizing their respective dumps. After midafternoon American supplies could move on 2½-ton trucks or DUKWs directly to corps dumps, which were accessible to the gravel-surfaced roads inland. All beach dumps except ammunition were “sold out” or moved to corps dumps inland. On D plus 1 the 540th found the two best beaching channels and favorable exit roads and consolidated unloading at two American beaches. The regiment eliminated the British Peter beaches by D plus 3, and British supply rolled in over the American beaches as well.38

One obstacle to hasty unloading was shallow water, which made it necessary to anchor the Liberty ships two miles offshore. Cargoes therefore came in on LCTs or DUKWs. The average load of all LCTs was 151 long tons; of DUKWs, three tons. Cargo from Liberty ships began to reach the beaches on the afternoon of D plus 1, and the VI Corps dumps (one mile beyond the beach) opened at 2300 the same day. All the D-day convoys of LCTs and LSTs were completely unloaded by 0800 on 24 January, D plus 2. But even their rapid discharge could not obviate the fact that the scarce LSTs supplying the Anzio beachhead had to remain on the scene until spring, long past the time allotted. Their continued stay in the Mediterranean to serve shallow-water ports denied

Map 9: Anzio Beachhead, 22 January 1944

them to the BOLERO planners in England, who were bent on accumulating at least half the assault shipping required for the invasion of the Continent by the beginning of 1944.39

The 540th owed its performance at Anzio to several factors. The men of the unit had been able to plan for SHINGLE at Caserta with the 3rd Division, and they had practiced landings with the division and its attached units. During 17-19 January the final exercise, WEBFOOT, involved the 3rd U.S. and 1st British Divisions, a Ranger force, and attached supply troops. The rehearsal was not full scale; LSTs did not carry vehicles and LCTs were only token loaded, but the assault units did get some training in passing beach obstacles, unloading personnel and equipment, combat firing, and general orientation.40

The 540th had been able to obtain extra ¼- and ¾-ton trucks, D-7 angledozers, sixteen- and six-ton prime movers, cranes, mine detectors, beach markers, and lights. The D-7s proved especially valuable on D plus 1 in pulling out 100 vehicles mired down in the de-waterproofing area. Compared with previous landings, the 540th Engineers had a better system of recording the numbers of vehicles and personnel and quantities of supplies by class. These advantages helped to nullify mistakes in planning and deficiencies in training. Not until the 540th was about to leave Naples for Anzio did its attached units report—after loading plans were complete. Since the 540th had to plan for the embarkation on the basis of TOEs rather than actual unit strengths, it was difficult to load units properly. The loading plan was faulty in that beach groups went aboard by units instead of by teams.41

Supplies landed late at the port of Anzio on D-day, when LSTs did not enter from the outer harbor until eight hours after naval units had signaled that the harbor had been swept for mines. The Navy beachmaster would not take the responsibility of acting on the signal, and the deadlock was broken only when two Army officers appealed personally to Admiral Hewitt.

Officers of the 540th Engineers sometimes found working with the British easier than working with the U.S. Navy, possibly because there were more opportunities for friction with the U.S. Navy. Its responsibility for unloading extended to the beaches, whereas the Royal Navy’s jurisdiction ended when the craft hit the beaches. Teamwork was often poor between floating and shore U.S. Navy echelons. Furthermore, the commanding officers of the naval beach battalion had been reluctant to train and live with the Army. The naval beach group did not have enough bulldozers and needed Army help for salvage work. The Navy also needed bulldozer spare parts, but these the Army could not provide because the Navy used Allis-Chalmers bulldozers, which the Army did not have.42

At the beach the principal engineer work was to improve exit roads over soft, boggy clay soil. Engineers had to

36th Engineer Combat Regiment troops remove German charges from buildings in Anzio

use corduroy because they did not have enough rock, even after taking as much as possible from the rubble-strewn towns of Anzio and Nettuno. They used Sommerfeld matting, which the 540th Engineers modified for beach roads, to some extent. They made the rolls lighter and the footing better by removing four out of every five lateral rods and using the extra rods as pickets to hold down the matting. The engineers tried brush on the roads, but corduroy proved the best substitute for rock.43

On 7 February the enemy began a series of assaults that threatened to split the bridgehead within a fortnight. Engineers went into the line as infantry, holding down both extreme flanks of the Anzio enclave, the 39th Engineer Combat Regiment on the right and the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment, a corps unit, taking over the British 56th Infantry Division’s responsibility in a sector about nine miles northwest of Anzio on the extreme left. In the line for forty-five days through February and March, the 36th held 5,600 yards of front along the Moletta River with 2,150 men, its reserve almost constantly employed. The engineers spent 1½ days training mortar men and considerable time

afterward gathering necessary sniper rifles, automatic weapons, and 37- and 57-mm. antitank guns.44

Though the 39th performed well, the hard-pressed 36th quickly showed its inadequate infantry training. Conspicuous was its failure to seize prisoners during night patrolling in the early commitment to the line. Upon a corps order to send out one patrol each night from each battalion on the front, the engineers blackened their faces and reversed their clothing to camouflage themselves and left their helmets behind to avoid making noise in the shrubbery. When they sallied out into the darkness, however, they lost two men to the Germans and captured no prisoners in return. One observer remembered that the men were not “prepared to kill” and seemed afraid to fire their rifles in fear of drawing the attention of the whole German Army to themselves. The regiment’s inexperience also showed in casualty figures, which reached 16 percent. Seventy-four men were killed in action, 336 wounded, and 277 hospitalized.45

During the fighting at Anzio destroying bridges was more important to the engineers than building them. A bridge VI Corps engineers blew up at Carroceto on the afternoon of 8 February kept twelve German tanks from breaking through to the sea. On the tenth the engineers staved off a possible German breakthrough by destroying a bridge over Spaccasassi Creek.46

When the Allies were forced on the defensive at Anzio the engineers laid extensive minefields for the first time in the Italian campaign. They planted mines haphazardly and made inaccurate and incomplete records. They laid many mines, both antipersonnel and antitank, at night in places with no distinct natural features. Some of this haste and inefficiency was attributed to insufficiently trained men, including some who were not engineers and who were not qualified for mine-sowing. Troops disregarded instructions 15th Army Group issued early in the campaign on recording friendly minefields. The result was a marked increase in casualties.

As the Anzio beachhead stabilized, haphazard methods became more deliberate and careful. Fields were marked and recorded before mines were actually laid. After 10 February VI Corps insisted that antipersonnel mines be placed in front of protective wire and that antitank mines be laid behind the final protective line, both in order to guard against night-lifting by the enemy. At regular intervals the VI Corps engineers issued a map overlay numbering and locating each antipersonnel and antitank minefield on the beachhead.47

No standard method of planting mines existed, but the system developed by the 109th Engineer Combat Battalion was representative. The battalion used four men to a row, with teams made up of a pacer who measured the distance, a driver who placed the mines, and two armers who activated the mines. At Anzio in April 1944 a platoon of the 109th in one day devoted 240 man-hours to planting 2,444 antitank mines

Soldier from the 39th Engineer Combat Regiment assembles M1A1 antitank mines at Anzio

and 199 antipersonnel mines. A separate squad took ninety-six man-hours to mark these minefields.

One of the most serious mistakes in planting mines was laying them too close together. For example, the 39th Engineer Combat Regiment laid a large minefield that a single mortar shell detonated. The experience of many units proved that a density of 1½ antitank mines per yard of front was the optimum for regularly laid out fields to avoid sympathetic detonation. The engineers obtained this density by laying several staggered rows of mines, an approximation of the German pattern. The AFHQ engineer specified wider spacing for antipersonnel mines, a rule of thumb that established one mine per three to five yards of front, assuming the use of trip wires.48

Once the Germans stopped trying to eliminate VI Corps’ beachhead, the Anzio front settled down into stalemate. The 39th Engineers, with assistance from the 540th, then had an opportunity to improve all roads within the beachhead. Good macadam roads ran through the area in wagon-spoke style, and a few smaller gravel roads branched off. Engineers bulldozed additional dirt roads across the open fields, but trucks using them had to drop into very low

gear to plow through the mud. The engineers maintained only about thirty-one miles of road at the beachhead, but constant enemy bombing and shelling compelled continuous inspections and surface repair. Engineers built a considerable number of bridges in the beachhead area; the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion, for instance, built 2 Baileys, 9 treadways, and 19 footbridges.49

During the breakout from the Anzio beachhead, the 34th Division’s 109th Engineer Combat Battalion had the task of opening and maintaining roads to the front lines, clearing lanes through Allied minefields up to the front, and opening gaps in Allied wire on the front to ensure the safe and uninterrupted passage of another infantry division, the 1st Armored Division, and the 1st Special Service Force through the 34th Division’s sector. Work started during the night of 14 May; enemy observation forced the engineer units to work only after dark. Many of the minefields had been under heavy enemy fire from small arms, machine guns, and artillery. The mines became extremely sensitive and were likely to detonate under the slightest pressure. The engineers completed most of the mine clearing during the night of 20 May, but they had to wait to remove wire and to mark gaps which would disclose the direction of the corps attack. On the night of 22 May the engineers removed the wire from the gaps and marked each lane with tracing tape and luminous markers. The breakout was a complete success.50

On 31 May Peninsular Base Section took over the Anzio port after four months and twenty-five days of operation by the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment. Supply had been slow through much of February and March because of bad weather and enemy air raids. The shallow offshore gradients and the small beaches hampered the use of regular cargo ships and coasters. Such vessels were excellent targets for German aircraft, so shallow-draft craft were used as much as possible. The whole process of delivering supplies speeded up in March with the use of preloaded trucks, which discharged from the LSTs and other vessels directly onto Anzio harbor’s seawalls and pier and moved directly to the dumps. Liberty ships carrying supplies unloaded onto LCTs or DUKWs. In turn, the LCTs unloaded onto DUKWs offshore or directly onto wharves in Anzio harbor; the DUKWs went directly to the dumps. Between 6 and 29 February, 73,251 tons were discharged at Anzio; between 1 and 31 March, 158,274 tons. The 7,828 tons that came in on 29 March made Anzio port the “fourth largest in the world.”51