Chapter 10: The Advance to the Alps

By the time the Allied armies collided with the German Winter Line defenses in late 1943, the American theater command had changed considerably. In the aftermath of the North African invasion the need to reorganize had been clear; the issue of new command arrangements was a lively one at the American headquarters, but the demands of combat kept it pending until the downfall of Axis forces in Tunisia and Sicily.

The chief defect still lay in the overlapping and sometimes contradictory authorities in the administrative and supply chain. A new theater engineer, Brig. Gen. Dabney O. Elliott, continued to exercise his advisory and staff functions in three separate commands—AFHQ; NATOUSA; and COMZ, NATOUSA—an arrangement that bypassed the Services of Supply command. No formal controls of the engineering function existed between SOS, NATOUSA, and the chief engineer of the theater as they did in General Lee’s SOS, ETOUSA, jurisdiction in the United Kingdom. Maj. Gen. Thomas B. Larkin as chief of the SOS, NATOUSA, command had only nominal control over the base sections then existing in the theater and virtually no say in the flow of supply once materiel moved out of the bases for the front lines. Larkin’s relationship with the AFHQ G-4 was unclear and in many ways duplicative through the period of operations in North Africa; it improved only after his concerted efforts to revise the command situation met with some success.1

Reorganization

In March 1943, one month after the formation of the theater, General Larkin began a campaign to eliminate the anomalies and duplications that weakened or destroyed his effectiveness as supposed chief of all American supply operations in the theater. He made small headway against the resistance of the staff officers at NATOUSA and AFHQ who insisted upon retaining their acquired authority, citing in their own behalf the dangers of repeating the bitter disputes over the SOS, ETOUSA, empire under General Lee. In hopes of reducing the manpower drains in theater-level headquarters, the War Department sent an Inspector General’s survey team to North Africa and to England in late spring 1943. The team’s report, in effect, recommended a 50 percent reduction in the number of overhead personnel in the theater staffs in NATOUSA, a solid impetus for reorganization and economy in manpower.

Various plans originating at AFHQ and NATOUSA undertook to eliminate the command discrepancies and to reduce the manpower surpluses in headquarters’ staffs. Their authors usually proceeded on the assumption that vast changes were necessary in any staff element but their own. After a summer and fall of conflicting suggestions in 1943, the SOS, NATOUSA, command had no increased authority to deal with its increased responsibilities, which now spanned the Mediterranean and extended to a new base section in Italy. Headquarters, NATOUSA, insisted upon the continued control of personnel in the base sections, denying to Larkin efficient use of manpower and timely use of specialty units when he needed them.

The arrival of a new theater commander broke the impasse and presaged the decline of Headquarters, NATOUSA, and the disappearance of COMZ, NATOUSA, in early 1944. On 31 December 1943, Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers relieved General Eisenhower, who returned to ETOUSA. When Devers arrived in North Africa On 8 January 1944, the War Department had imposed a deadline of 1 March for the revision of the NATOUSA command structure. Devers’ arrival also roughly coincided with another exchange between SOS, NATOUSA, and Headquarters, NATOUSA, about more men for the burgeoning supply responsibilities in the theater. Within a week in late January General Larkin received two contradictory orders from NATO-USA. The first instructed him to tap the existing base sections for manpower, a course he was reluctant to take since it would rob already shorthanded organizations in his nominal chain of command; the second canceled the authority to secure manpower from even that source and removed manpower allocations authority for base sections entirely to the NATOUSA level.

On 14 February Devers called the conference that restructured the theaters. (Chart 2) His NATOUSA General Order Number 12, effective 24 February, transferred all duties and responsibilities of COMZ, NATOUSA, originally set up only as a rationale to support the position of deputy theater commander, to SOS, NATOUSA. In-the month after the meeting the NATOUSA staff took much of the theater reduction in manpower.2 While the staff did not disappear altogether, its functions became almost entirely identified with the American side of AFHQ. Headquarters, NATOUSA, concerned itself with matters of broad policy at the theater level, and General. Larkin formally assumed command of all base sections in the theater and the service and supply functions between them and the combat zones.

Consistent with this general transfer and with a subsequent NATOUSA staff memorandum, the AFHQ-NATOUSA engineer retained only policy and planning responsibility. He could initiate broad directives, recommend theater-wide engineer stock levels, write training directives and standards, recommend troop allocations in the communications zone, maintain technical data on Allied or enemy engineer equipment or doctrine, and provide analyses of operations plans and American engineer commitments in the theater. The

Chart 2: Theater Structure, AFHQ and NATOUSA, 8 February 1944

broader engineer aspects of Allied military government also fell within his purview.3

In General Larkin’s SOS, NATO-USA, executive agency, the SOS engineer had unfettered jurisdiction over operational engineer matters in the theater COMZ. He controlled engineer units assigned to that command, governed the issue of nonstandard equipment to all American engineer troops, ruled on all requests to exceed accommodation scales, and handled all American real estate questions. He also controlled the issue of engineer supply to Allied forces, coordinating with AFHQ only on British requests. He was responsible for taking general operational directives emanating from AFHQ and preparing supply requisitions and bills of materials to support stated theater programs and policies.4

When the Fifth Army Base Section at Naples became the Peninsular Base Section (PBS) on 25 October 1943, it passed from Fifth Army control to the still divided American theater command in North Africa. Until February 1944 the base section in the Mediterranean came under NATOUSA headquarters for command and administration but answered to General Larkin’s SOS, NATOUSA, organization for supply. General Pence’s PBS command also had some responsibilities to the 15th Army Group in administrative areas, especially those affecting the Italian population.

As Fifth Army moved north, base section jurisdiction grew: the army rear boundary was always the PBS forward boundary. The base section engineer, Col. Donald S. Burns, submitted his first consolidated estimates for the supply requirements of the Fifth Army engineers, the III Air Service Area Command, and various other branches of the PBS Engineer Service and the Petroleum Branch on 15 October 1943, but the Fifth Army G-4 continued to prepare engineer requisitions until December, when the responsibility shifted entirely to PBS for Fifth Army and base section engineer supply. Requisitions then went directly from PBS to SOS, NATOUSA, and its successor command, designated Communications Zone, NATOUSA, on 1 October 1944. Exactly one month later the theater command changed from NATOUSA to Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTOUSA). On 20 November the COMZ structure was eliminated and its functions passed to the G-4 and the special staff of the MTOUSA headquarters, which then handled engineer requisitions and other supply for the theater. (Chart 3)5

While the theater reorganization was bringing order to the higher echelons on the American side of AFHQ and its immediately subordinate commands, several important changes also occurred in Fifth Army’s command and administration of its engineers and other service troops. Col. Frank 0. Bowman, the Fifth Army engineer, promoted to brigadier general on 22 February, became convinced by early spring

Chart3: Office of the Chief Engineer, MTOUSA, 28 January 1945

of 1944 of the necessity of obtaining direct command of all Fifth Army engineer troops. Other technical service staff officers shared this idea, particularly General Clark’s ordnance officer, Col. Urban Niblo.6

On 26 March 1944, all corps and army engineer units were assigned to a new Fifth Army Engineer Command. Corps engineer units, however, remained attached to their respective corps. Accordingly, though General Bowman obtained administrative and supply control over all engineer units except those organic to divisions, he did not have operational control over those attached to corps. His headquarters, designated a major command of the Fifth Army, had an operational and administrative status similar to a general staff division, and he had the authority he considered necessary to meet his responsibilities. He could move army engineer troops from point to point on his own authority and could transfer Fifth Army engineers from American to British sectors and back.7

Below General Bowman in the Fifth Army engineer organization were corps engineer sections, each with a TOE calling for only six officers and fourteen enlisted men. Some attempt was made to obtain approval for corps-level engineer commands patterned after General Bowman’s, but the corps commanders preferred that the corps engineer remain a staff officer only.8

The engineer combat regiment was the mainstay of corps-level engineer strength at the start of the Italian campaign, but in December 1942 War Department planning revised the formal and rigid structure of Army units, eliminating the “type army” and “type corps” conceptions. The re-division of forces that followed placed engineer units by functions, under Army Ground Forces control if they supported combat units or under Army Service Forces control if they had primarily service support assignments in base sections or the communications zone. Engineer units were frequently hard to classify since the nature of their assignments and training carried them across the boundaries established in Army Ground Forces Commander Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair’s reorganization.

Further revision of the unit classification continued through 1944; at the end of the year only divisional engineers were listed as combat troops, with nondivisional engineers supporting fighting units being listed as combat support. At the same time General McNair pushed for economies in service forces and in staff overheads in field commands. He strove to separate nondivisional service regiments, including engineers, into their component battalions and to impose a group headquarters capable of handling four battalions at once in place of the formal and traditional regimental headquarters in the field.9 The group headquarters had no units assigned organically but controlled the movements and work assignments of each battalion as an attached unit.

In the summer of 1943, McNair outlined his new organizational precepts

in a letter to all training commands under his control. He recommended that to manage troops engaged in combat the higher level headquarters divide the administrative load, making the corps solely a tactical headquarters and limiting field army headquarters to overall tactical supervision with responsibility for supply and all other administrative functions. The new program did make for marked economies in manpower, and at the end of the war the revisions had contributed to far more efficient combat units. But General McNair’s innovations were not received with favor everywhere, nor were they applied consistently. The technical services, notably the engineers, had already anticipated some aspects of the reform, but as the distance from Washington increased the revision tended to become watered down or compromised with proven local practice.10

Resistance to the group concept began at the top of the Fifth Army Engineer Command in Italy. When the War Department authorized the establishment of group headquarters for all service units in October 1943, the rate of conversion was left to the theater command. General Bowman, with the concurrence of General Elliott, the AFHQ engineer, slowed down the adoption of groups, keeping “the correspondence about the change bouncing between Italy and Washington.” Bowman believed that the group organization hurt morale because the attachment of single battalions to larger units lasted for only brief periods. Some engineer regiments continued to operate as such until 1945.11

Even after all the combat engineer regiments had converted, arguments continued over the value of the change. General Bowman also believed that the various group headquarters added to administrative overhead and reduced even further the amount of construction equipment available, thereby aggravating an already critical problem. The II Corps engineer, Col. Leonard B. Gallagher, held that the group operated less efficiently than the regiment. Lt. Col. William P. Jones, Jr., commander of an engineer battalion attached to II Corps’ 1108th Engineer Combat Group, contended that the group wasted scarce trained engineer officers and specialists. There were, however, strong defenders of group organization who stressed the gain in flexibility and pointed out that a group headquarters could control more battalions than could a regimental headquarters. The 1108th Combat Group in 1945, for example, had under it as many as seven units at one time and for a period supported five divisions. The quality of the group or regimental commander and the experience of his men were the keys to the effectiveness of both organizations. In any case, the self-contained battalion became a workable organization.12

The divisional engineers had both staff and command responsibilities. Unlike the G-3, who thought mainly in terms of objectives, a division engineer was largely concerned with such matters as routes of approach, crossing sites, and covered assembly areas for

General Elliott

equipment. Since building and maintaining roads in the division area as well as supporting three regimental combat teams were necessary, the three companies of each divisional engineer battalion had to be divided among four missions. This dispersion made the battalion less efficient and overburdened the men. Consequently, from the very beginning of the campaign, corps engineer units answered constant requests to move forward into divisional areas.13

General Bowman believed that those in command needed convincing that tactical boundaries between divisions and corps could not apply to engineer work. The division engineer could—and did—ask the corps engineer to take over work in division areas that the division could not do with its own forces. In fact, army engineers sometimes worked well into divisional sections. The belief was quite common that the divisional combat battalion was simply too small to do all the work required of it.

Throughout the long campaign the engineers of Fifth Army, especially those in the divisions, resisted attachment to combat teams. In the 313th Engineer Combat Battalion, 88th Division, the line companies normally supported the same infantry regiment all the time, with the engineer company commander becoming practically a member of the regimental staff. The companies never waited for the engineer battalion to direct them to perform their normal mission, so infantry regimental commanders rarely insisted on having the engineer companies attached to them. But by the end of the war attachment was rare in other divisions because the infantry commanders finally became convinced that engineer support would be where they wanted it when they needed it.14

Most engineer officers favored a daily support system in the belief that once engineer troops became attached to a forward echelon they could not easily be transferred again. They believed it impossible to forecast accurately the amount of engineer work required in the areas that lay ahead; any specific number of engineers attached would be either too large or too small. Additionally, improvised task forces and

regimental combat teams in general did not have the staff organization to control engineer work, so lost motion and confusion became common. The engineers also maintained that subordinate commanders retained engineer units after their specific task was done.

The nature of engineer tasks often splintered engineer units—regiments, battalions, and detachments alike. Depot, camouflage, maintenance, and dump truck companies were more susceptible than others. In June 1944 the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion came together for the first time in more than four months. Such dispersion inevitably affected performance, discipline, and morale, caused duplication of effort, and made administration more difficult.15

The Offensive Resumed

When the Allied offensive resumed in May 1944, the main Fifth Army line south of Anzio was to drive north up the coast to meet VI Corps troops breaking out of the static bridgehead. North of Anzio, other VI Corps units were to strike for Rome. Preparations for the renewed offensive began in March with a shift of British Eighth Army units westward to take over the Cassino and Rapido fronts, leaving in their place a garrison force on the eastern Italian coast. Thus relieved, and with replacements arriving to bring its divisions up to strength, Fifth Army consisted of the American II Corps and the French Expeditionary Corps concentrated on a thirteen-mile front between the Italian west coast and the Liri River, with II Corps holding the left flank of the line. Two fresh but inexperienced American divisions, the 85th and the 88th, would bear the brunt of the drive along Highway 7 to effect a junction with the forces at Anzio, now reinforced to a strength of 5½ divisions.16

A devastating artillery bombardment commencing at 2300 on 11 May sparked the offensive on the southern front, and at dawn the Mediterranean Allied Air Forces rained destruction on the enemy rear. The Anzio breakout began on 23 May, and on the twenty-fifth VI Corps was advancing toward the Alban Hills. The same day, after II Corps had driven sixty miles through the mountains, the beachhead and the Fifth Army main line were linked for the first time when men of the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion, II Corps, shook hands with the engineers of the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment, VI Corps, outside the demolished village of Borgo Grappa. The linkup was part of the campaign that smashed the German Gustav Line and the less formidable Hitler Line, which the enemy had thrown across the Liri valley and the mountain ranges flanking it.

The nature of the terrain and the scarcity of roads made the Fifth Army’s offensive on the southern front largely mountain warfare, in which the experienced French corps bore a major share of the burden. The only good road available to Fifth Army, Highway 7, crossed the Garigliano near its mouth

and followed the coast to Formia. From there it bent northwest and passed through mountains to Itri and Fondi, then along the coastal marshes to Terracina, where it turned again to the northwest, proceeding on a level and nearly straight course through the Pontine marshes to Cisterna. Beyond Cisterna the road led toward Rome by way of Velletri, skirting the Alban Hills to the south.

Highway 7 lay at the extreme left of the line of advance, but it was II Corps’ sole supply route. Apart from this highway Fifth Army had the use of two or three lateral roads, a few second- and third-class mountain roads in the French corps’ area, and some mountain trails. Insufficient as the roadnet was, it was spared the sort of destruction that the enemy might have been able to visit upon it in a less hasty withdrawal.

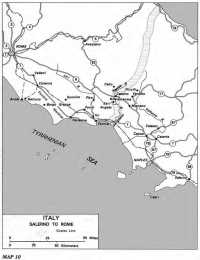

After the breakout began, the engineers labored night and day to open the roads and keep them in shape under the heavy pounding of military traffic. At first the engineers’ chief concerns were to erect three additional Class 40 bridges over the Garigliano, two for the French and one for II Corps; to strengthen to Class 30 a bridge in the French Expeditionary Corps zone; and to build several assault bridges for troops and mules. Then engineers began improving trails into roads for jeeps, tanks, and 2½-ton trucks, often under artillery fire. Starting about the middle of May the principal engineer Work was clearing and repairing Highway 7 and a road leading across the northern slopes of the Aurunci Mountains to Pico on lateral Highway 82. (Map 10)17

The 313th Engineer Combat Battalion, 88th Division, undertook swift construction to outflank the Formia corridor on Highway 7. In one day the men of this battalion opened a mountain road that the Germans had spent two weeks preparing for demolition. This road connected with a trail two miles long that the 313th built in nine hours over steep hills that vehicles had never before traversed. A few men working angledozers through farmland and brick terraces and along mountain slopes did the work. A German engineer colonel, captured a few hours after the battle and evacuated over the road, was amazed, for no road had been there twenty-four hours earlier.18

At Itri on Highway 7 a platoon of Company A of the 310th Engineer Combat Battalion, 85th Division, built a 100-foot Bailey and turned over its maintenance to the 19th Engineer Combat Regiment. The 235th Engineer Combat Battalion, a II Corps unit that normally supported the 310th, followed up the 310th’s repair and clearance work along Highway 7. The Germans had destroyed many bridges between Fondi and Terracina, and the American engineers had to build bypasses and culverts. At a narrow pass between the mountains and the sea east of Terracina, tank traps and roadblocks, covered by German fire from nearby hills, slowed the advance along the highway. When a blown bridge along this stretch halted American tanks, armored bulldozers of the 235th and 310th Engineer Battalions and the 19th Engineer Regiment, all under fire, built a bypass that made it possible to resume the advance. Lt. Col. Allen F. Clark, Jr.,

Map 10: Italy, Salerno to Rome

commanding the 235th, operated one of the bulldozers.19

When the advance slowed at Terracina the 310th Engineer Combat Battalion immediately started on an alternate route to connect the highway with Sonnino. A road capable of carrying the traffic of an entire division had to be cut into the rocky slopes of the Ausonia Mountains. The engineers’ road-building machinery had done remarkable things in the mountain chain during the drive from the Garigliano, but this job required much hand work and many demolitions, explosives for which had to be carried by hand up rugged mountain slopes. The engineers had cut six miles of the new road, with only one mile left, when a breakthrough at Terracina made it unnecessary to finish the alternate route. The work was not entirely lost, for the road reduced the need for pack .mules and made it possible to move division artillery farther forward to interdict the road junction at Sonnino.20

Beyond Terracina the highway ran thirty miles straight through the Pontine marshes to Cisterna. All the engineers available worked around the clock repairing and maintaining three routes through the marshy flats. The Germans had attempted to flood much of this region but were only partially successful; the water was low in the streams and canals. Nevertheless, the engineers had to do considerable filling along the main routes as well as some bypassing and bridging. When Highway 7 and the supplementary routes were open to the Anzio beachhead, troops and supplies.

The Arno

During the summer advance to the Arno, about 150 miles, the Fifth Army front reached inland approximately 45 miles. Two main national highways ran northward in the army zone. Highway 1 ran northwest up the coast through a succession of important towns, including Civitavecchia and Leghorn, to Pisa, near the mouth of the Arno. For most of its length the highway ran along a comparatively flat coastal plain, nowhere more than ten miles wide, but between Cecina and Leghorn, Highway 1 twisted over mountains that reached down to the sea. The other main road, Highway 2, wound through hills, mountains, and river valleys along a route that led from Rome through Siena to Florence. There were five good two-way lateral roads in the area between Rome and the Arno; numerous smaller roads were, for the most part, narrow and unpaved.

During the advance to the Arno the army had to cross only two rivers of any size, the Ombrone and the Cecina, both at low water. The port of Leghorn fell to the 34th Division, II Corps, on 19 July. Beyond Leghorn lay numerous canals, but engineers quickly bridged them. Four days later the 34th Division reached Pisa. The march in the dry summer weather took place in clouds of dust that drew artillery fire and choked the troops. Soldiers wore goggles over their eyes and handkerchiefs

across their noses and mouths. Some of the roads, surfaces ground through by military traffic, were six to eight inches deep in dust. Sprinkling the roads with water was the best way to lay the dust, but water tanks were so scarce that only the most important roads could be sprinkled. Sometimes the engineers applied calcium chloride, but it was also scarce and its value questionable. Engineers had some success with used oil, but even that was in short supply.21

During the June and July drive to the Arno much of Fifth Army’s forces departed to prepare for ANVIL, the invasion of southern France. The army lost VI Corps and the French Corps. That loss amounted to seven full divisions, and the loss of separate combat units amounted to another division. The nondivisional engineer units splitting away at that time included the 36th and 540th Engineer Combat Regiments, the 48th Engineer Combat Battalion, and the 343rd and 344th Engineer General Service Regiments. On 1 June Fifth Army’s assigned strength had been approximately 250,000; on 1 August it was little more than 150,000. Making up the losses were the Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team (which arrived in May but left for France in late September); two new and inexperienced U.S. Army infantry divisions, the 91st and 92nd; and the first elements, about a regimental combat team, of the untried Brazilian Expeditionary Force, which was to grow to the size of a division. In August General Clark gained control over the veteran British 13 Corps consisting of four divisions.

From mid-July to mid-August Fifth Army made little forward progress; it paused to rest, to build up supplies, and to prepare for the ordeal ahead. The II and IV Corps held the 35-mile sector along the Arno, IV Corps occupying the greater part of the line while the major portion of II Corps was in the rear preparing for the coming offensive. The troops received special instruction in river crossing and mountain warfare. Engineer detachments gave instruction in handling footbridges and boats, in scaling steep banks with grappling hooks and ladders, and in detecting and clearing mines.

The Italian campaign resumed in earnest on 24 August with an Eighth Army attack on the Adriatic front. The Fifth Army crossed the Arno on 1 September, and on 9 and 10 September II Corps launched an offensive north of Florence. With 13 Corps beside it, II Corps battled through the mountains, capturing strongpoint after strong-point, and on the eighteenth reached the Santerno valley by way of II Giogo Pass. The 88th Division outflanked Futa Pass, key to the enemy’s Gothic Line defenses, and on the twenty-second a battalion of the 91st Division secured the pass. Fifth Army had breached one of the strongest defense lines the enemy had constructed in Italy. The attack had been well timed, for the Germans had diverted part of their strength to the Adriatic front to ward off an Eighth Army blow. With Futa Pass in the hands of Fifth Army troops, the way was clear to send supplies forward by way of Highway 65 and to prepare for an attack northward to Bologna.

Rain, mud, and many miles of mountain

The rising Arno river threatens a treadway bridge in the 1st Armored Division area, September 1944

terrain combined to aid the enemy. Highway 65 was the only completely paved road available to II Corps, and off that highway 2½-ton trucks mired deep in mud. Such conditions made a mockery of mechanized warfare. Mules and men had to carry food and ammunition to the front. Nevertheless, II Corps troops pushed steadily on and brought the front to a point two miles from Bologna by mid-October. By 23 October the forward troops were within nine miles of Highway 9 and could look down upon their objective in the Po valley. But here the fall offensive faltered. Exhaustion and heavy rains forced a halt, and II Corps dug in.

The fall rains had given the engineers an enormous task. In September the Arno west of Florence in IV Corps’ zone flooded its banks and on one occasion rose six to eight feet at the rate of eighteen inches an hour. Late in the month the Serchio also overflowed its banks north of Lucca, at Lucca itself, and at Vecchiano. So much bridge equipment was lost that the IV Corps engineer had to divert engineers from bridge construction and road work to salvage operations.22 Mountain streams that had dwindled to a trickle in the summer

Bailey Bridge construction over the Arno near Florence

changed in a few hours to raging torrents. Through most of October the rain continued unabated, becoming a torrential downpour by the end of the month. Cross-country movement virtually ceased, and great quantities of mud were tracked onto the main roads from secondary roads and bivouac areas. Culverts and fills washed out, fords were impassable, and roads softened until they could not withstand heavy military traffic.

Engineer vehicles and equipment deteriorated from constant hauling through deep mud over very rough roads. Breakdowns were so numerous and the supply of spare parts so low that at times some engineer units had to operate with only half of their organic equipment. Because divisional engineers had to devote all their efforts to supporting frontline troops, corps engineers had to maintain supply routes in the divisional zones.23

More floods came in November, and at one time or another during that month all the principal highways were blocked with high water. The 39th Engineer Combat Regiment reported fourteen major road breaks along a six-mile stretch of Highway 6 northwest of Florence, making necessary the construction of four Bailey and three timber trestle bridges. The autostrada, a four-lane superhighway that carved an arc through the Arno valley, connecting Florence with Pistoia, Lucca, and the coastal road north from Pisa, was covered for miles with water as deep as two feet. As the campaign ground to a halt, the whole Italian front settled down into mud.24

The Winter Stalemate

The stalemate continued throughout the winter of 1944-45. To permit supplies to be brought forward, the engineers had to work unceasingly on the roads. On Highway 65—the direct road to Bologna from the south, the main supply route for the Fifth Army’s central sector, and the only fully paved road in the II Corps zone—jeeps, trucks tanks, and prime movers rolled along almost without letup day and night. Already in bad condition and cut in places by the enemy, Highway 65 suffered serious damage from rain, snow, and the constant pounding of thousands of vehicles, many of them equipped with tire chains. Army, corps, and

divisional engineer units had constantly to maintain the whole length of the road, especially north of Futa Pass, where the pavement virtually disappeared. The main inland supply route for IV Corps, Highway 64, running from Pistoia to Bologna, carried less traffic than Highway 65 and therefore remained in somewhat better condition.25

In preparation for winter, the engineers placed snow fences and stockpiled sand. They speeded clearance after snowfalls to prevent ice formation and during thaws to prevent drainage problems. Foreseeing that the greatest difficulty with snow would come in the passes leading to the Po valley, AFHQ developed a plan involving joint transportation and engineer operations to clear the roads. The plan included control posts, road patrols, and a special communications system to report conditions throughout each day. The Engineer Section, Fifth Army, prepared a map that indicated the areas where trouble could be expected, including areas the Germans held. The engineer and transportation units involved piled sand along the roads where the most snow could be expected and parked snow-removal equipment at strategic points along the roads.

The plan worked in the II Corps area, where winter conditions were the most severe. In addition to American and British troops, hundreds of Italians, both civilian and military, worked to keep the roads open. Large rotary snowplows augmented jeeps, graders, bulldozers, and wooden and conventional snowplow attachments fitted to 2½- and 4-ton trucks. Some German and Italian equipment the enemy had left behind also proved useful. Unfortunately, the plan did not develop successfully all along the front. IV Corps was not able to set up a system comparable to the one II Corps employed because IV Corps did not have anything like the snow-removal equipment of II Corps. Instead, IV Corps units had to drop whatever they were doing when snow began to fall and clear the roads with whatever equipment was available. Only a few roads in IV Corps’ area were seriously menaced by snow, however, and most lay in the coastal plain.26

During the fall and winter the engineers were able to open mountain trails. Soft banks and shoulders gave way readily before bulldozers, which widened roads, provided turnouts on one-lane sections, and improved sharp curves and turns. Huge quantities of rock were required to keep these roads open to a volume of traffic never before contemplated. The 19th Engineers used 25,000 cubic yards of rock to rebuild a 10½-mile stretch of secondary road adjacent to Highway 65 in the Idice valley. Keeping the improved trails open as roads necessitated unending work, including draining, graveling, revetting soft shoulders, removing slides, and building rock retaining walls. The greatest problem was drainage maintenance, for the mountain creeks, gullies, gorges, and cascades, when not properly channeled, poured floods upon the roads. Two months of constant work by thousands of civilians and soldiers using

both hand labor and machinery not only kept the roads open but improved them. In forward areas infantry units took over the maintenance of some of the lateral roads leading to their dispersed forces.27

The first of the units reorganized according to the new group concept began operations in December 1944. To improve control over miscellaneous engineer units operating under the Fifth Army engineer, General Bowman organized the 1168th Engineer Combat Group, with Lt. Col. Salvatore A. Armogida in command. The cadre for the new command came from an antiaircraft headquarters, and under it were such engineer units as a map detachment, dump truck companies, a heavy equipment company, a maintenance company, a fire-fighting detachment, a camouflage company, a topographic company, and a water supply company. Also attached were some Italian engineer battalions and a number of other units under an Italian engineer group.28

The Final Drive

Exceptionally mild weather beginning in mid-February enabled engineers to make substantial progress in repairing and rehabilitating the road-nets and improving and extending bridges. With snow rapidly receding from the highlands, a company of the 126th Engineer Mountain Battalion, organic to the 10th Mountain Division, built a 1,700-foot aerial tramway over Monte Serrasiccia (located 18 miles northwest of Pistoia) on 19 February.

Built at an average slope of 18 to 20 degrees, the tramway was finished in ten hours despite enemy fire. Casualties could come down the mountainside in three minutes instead of six to eight hours. The tramway hauled blood plasma, barbed wire, emergency K rations, water, and ammunition up the mountain. Another timesaver the battalion contributed was a 2,100-foot cableway constructed on 10 March, when the 10th Mountain Division was attacking over rugged terrain. Supported by two A-frames and built in six hours, the cableway saved a six-mile trip for ambulances and supply trucks.29

Lt. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., became commander of the Fifth Army in December when General Clark moved up to command the 15th Army Group. Before the spring offensive began, the Fifth Army received reinforcements of infantry, artillery, and reserves. Its divisions were over-strength and its morale high as the troops looked forward to a quick triumph over the sagging enemy. The British 13 Corps had returned to Eighth Army, but Fifth Army’s reinforcements helped balance that loss.

In April the two Allied armies, carefully guarding the secrecy of the movement, went forward into positions from which they could strike a sudden, devastating blow against the enemy. The Fifth Army front was nearly ninety miles long, reaching from the Ligurian Sea to Monte Grande, ten miles southeast of Bologna. The IV Corps held the left of this line—indeed, the greater part of it—stretching from the sea and through the mountains as far as the Reno River, a distance of about seventy miles. The II Corps crowded

General Bowman

into a twenty-mile sector, and to its right the Eighth Army, with four corps, extended the line to the Adriatic.

Formidable mine defenses lay ahead. Typical was a minefield just west of Highway 65 that consisted of six to eight rows of antitank mines laid in an almost continuous band for two miles. Before the final Allied offensive could begin it was necessary—after passing through the Allies’ own defensive minefields—to cut through or bypass such defenses, clearing German wooden box, Schu, and other mines that were difficult to detect, notably the Topf, with its glass-enclosed chemical igniter.30

The final battle of the campaigns in Italy began early in April with a 92nd Division diversionary attack on the extreme left, followed by an Eighth Army blow on the extreme right. Reeling, the enemy began to fall back, and troops of the Fifth and Eighth Armies captured Bologna on 21 April. The two armies moved into the Po valley behind armored spearheads and once across the river spread out swiftly in pursuit of the disorganized enemy.

In the broad valley the roadnet was good, in some places excellent, with many paved highways connecting the cities, towns, and villages scattered over the plain, a rich and thriving region in normal times. Most of the secondary roads were graveled and well kept, affording alternate routes to almost any point. Roughly parallel main arteries ran from east to west across the valley, while others ran north and south. With such a large, spreading roadnet and with secondary routes sometimes offering shortcuts for the pursuing forces, the fleeing enemy could do little to impede the Allies’ progress. As the campaign drew swiftly to its close, little road maintenance was necessary and was mostly confined to primary routes. The principal engineer task was crossing the Po, and that had to be done quickly to keep up the tempo of the pursuit and cut off enemy escape routes.31

The Po is a rather slow stream with many bars and islands and is generally too wide for footbridges. In front of Fifth Army its bed varied in width from 330 to 1,315 yards, the actual water gap

extending from 130 to 490 yards. Allied air strikes had destroyed the permanent high-level and floating highway bridges. The Germans maintained communication across the river by ferries and by floating bridges, many of which they assembled from remnants of permanent floating bridges after dark and dismantled before daylight.

The engineers knew that a huge amount of bridging would be necessary to cross the Po. Treadway bridging was in limited supply. The 25-ton pontons of the 1554th Engineer Heavy Ponton Battalion would be essential, as would many floating Baileys, which Fifth Army could borrow from the British. The width of the Po required storm boats as well as assault boats, heavy rafts, infantry-support rafts, and Quonset barges assembled from naval cubical steel pontons and powered by marine motors.

Fifth Army engineers were confident that they could build bridges on piles eighty feet deep or more despite the soft mud of considerable depth that formed the Po’s bed. Such piles came from U.S. engineer forestry units working in southern Italy, and the long trailers of the 1554th Heavy Ponton Battalion brought them to the front.

On 22 September 1944, Fifth Army engineers distributed a special engineer report on the Po throughout the army. The report consolidated all available information, and revised editions came out from then until the actual crossing. The 1168th Engineer Combat Group controlled camouflage, maintenance, depot, and equipment units and provided administrative service for some engineer units not under its operational control. The 46th South African Survey Company carried its triangulation net into the Po valley, while early in 1945 the 66th Engineer Topographic Company issued 1:12,500 photo-mosaic sheets covering the area and special 1:10,000 mosaics of possible crossing sites. The 1621st Engineer Model Making Detachment produced a number of terrain models of the Po valley.32

Special river-crossing training concentrated mainly on II Corps engineer units, but close to the actual crossing day Fifth Army switched bridging to IV Corps.33 The engineer units had thoroughgoing drills, and a group of II Corps’ combat engineers got special instruction in all the assault and bridging equipment the army stockpiled during the winter. This group was to operate with the troops ready to make the main movement across the Po, whether of II or IV Corps. Fifth Army had estimated that a floating Bailey would be required in both II Corps and IV Corps areas; the 1338th Engineer Combat Group’s 169th Engineer Combat Battalion was to build the II Corps bridge and the 1108th Engineer Combat Group’s 235th Engineer Combat Battalion, the IV Corps bridge. During March and April the 169th Engineer Combat Battalion sent several of its men to the British Floating Bailey Bridge School at Capua, and in April the entire battalion moved to a site on the Arno west of Pisa for training in building the bridges. The 235th Combat Battalion got only a few days of training—and even that for only part of the battalion.34

Estimating that the Germans would expect II Corps to make the main attack

Engineers bridging the wide but placid Po river

along the axis of Highway 65, Fifth Army determined to surprise them by having IV Corps deliver the first heavy attack along Highway 64. To avoid warning the enemy General Bowman decided to keep major bridging equipment at Florence and Leghorn, approximately 125 miles from the Po, rather than establish a forward bridge dump. Moreover, no suitable areas for bridge dumps existed along the parts of Highways 64 and 65 that Fifth Army held. To make dumps would have required a great deal of earth moving in the middle of winter, would have diverted engineers from other important jobs, and might have given away the plans for the attack. Because he expected the Germans to make a stand at the Po, Bowman believed he would have plenty of time to bring bridging to a place in the valley where it would be available for either corps.35

The German retreat was so precipitous that much of the planning proved a handicap rather than an advantage. The three leading divisions of IV Corps were at the river on 23 April, in advance of any II Corps units. Enemy resistance had become so weak that each division tried to get across the Po as fast as possible to keep up the chase without interruption. Engineers had to work feverishly to push the troops across by all means available.36

The II Corps engineers diverted to IV Corps during the crossing operation included operators for storm boats and Quonset barges, a company of the 39th Engineer Combat Group’s 404th Engineer Combat Battalion to operate floating equipment, the 19th Engineer Combat Group’s 401st Engineer Combat Battalion, and the 1554th Heavy Ponton Battalion.37 During the morning of the twenty-third all II Corps’ bridging that was readily available, including an M1 treadway bridge, 60 DUKWs, 4 infantry support rafts, and 24 storm boats with motors, moved in convoy to IV Corps. At Anzola fifty assault boats belonging to IV Corps joined the convoy, which went forward to the 10th Mountain Division and arrived at San Benedetto on the morning of 24 April. On the night of the twenty-second, fifty other IV Corps assault boats had also reached the 10th Mountain Division.38

The crossing began at noon on 23 April, when troops of the 10th Mountain Division ferried over the Po in IV Corps assault boats operated by divisional engineers of the 126th Engineer Mountain Battalion. Some of the men of the 126th made as many as twenty-three trips across that day. Starting at noon the engineers used the only equipment available to them—fifty sixteen-man wooden assault boats. By 2000 the 126th had ferried across the 86th and 87th Mountain Infantry Regiments plus medical detachments and two battalions of divisional light artillery (75-mm. pack). Only twelve boats were left, most of the rest having been destroyed by heavy German fire. The engineers suffered twenty-four casualties, including two killed.39

The 85th Division followed close behind. All assault river-crossing equipment the divisional engineers (the 310th Engineer Combat Battalion) had held had been turned over to IV Corps engineers in April before the Po crossing. When the division reached the Po its engineers had only nine two-man rubber boats and had to use local materials to build four infantry support rafts and three improvised rafts. On these, with the help of the 255th Engineer Combat Battalion of the 1108th Engineer Combat Group, the 310th crossed all reconnaissance and combat units of the division except medium artillery. The crossing took forty-eight hours, but in spite of enemy artillery fire the engineers suffered no casualties.40

The IV Corps engineers had not expected to be in the vanguard crossing the Po and had to cope with problems for which they were not prepared. During the afternoon of 24 April the 401st Engineer Combat Battalion, a II Corps organization on loan to IV Corps, started building a treadway bridge near San Benedetto. Working all night, with the help of the 235th Engineer Combat Battalion, the 401st completed the 950-foot span at 1030.41

Late on the afternoon of 24 April the 1554th Heavy Ponton Battalion (II Corps) started work three miles upstream on a heavy ponton bridge even though much of the equipment did not arrive until after the bridge had been completed with improvised equipment. When finished on the afternoon of the twenty-fifth the bridge was 840 feet long and consisted of 56 pontons, 49 floats, and 4 trestles. A ferry of Navy Quonset barges, which could haul two 2½-ton trucks, had operated all during the night of 24 April. Day and night, for forty-eight hours after the completion of these first two bridges over the Po, two IV Corps divisions and part of a II Corps division went over the river; within the first twenty-four hours some 3,400 vehicles crossed the bridges.42

Meanwhile, II Corps’ engineers seriously felt the diversion of men and equipment to IV Corps, which left them with no floating bridges or assault equipment. Much equipment supposedly still available to II Corps was lost, misplaced, defective, or still in crates. During the night of the twenty-third bridging equipment began to arrive, but treadway equipage was loaded on quartermaster semitrailers instead of Brockway trucks. On the morning of the twenty-fourth the II Corps engineer, Col. Joseph 0. Killian, reported to General Bowman that he had no bridging available and that he had no idea when it would be available since treadway construction depended upon Brockways with their special facilities for unloading. The Brockways had gone to IV Corps, and Colonel Killian had to depend upon Fifth Army engineers for other equipment. Also, many motors for Quonset barges that reached the river were defective. These conditions held up operations for almost a day. The confusion appreciably reduced II Corps engineer support to division engineers and led to last-minute changes in plans and hasty improvisations. The M2 treadway and ferries remained the chief means for crossing the Po in the II Corps area until missing parts for the Quonsets arrived from Leghorn.

After the Po the hard-pressed II Corps engineers had two more major streams to cross, the Adige and the Brenta, and again bridging equipment was late getting to them. An almost intact bridge II Corps troops seized near Verona proved sufficient until other bridges could be erected. At the Brenta River bridging arrived with the advance guard of the 91st Division. One of the first elements across a temporary trestle treadway at the Brenta was a section of the bridge train moving ahead with forward elements of the 91st Division to the next crossing. In the IV Corps sector German defenders of a bridge across the Mincio at Governola held up the forward drive on the twenty-fourth only momentarily. Although damaged, the bridge proved usable, and the 37th Engineer Combat Battalion, which for more than two days and nights had been working with little or no rest, had it open for traffic in a few hours.43

The drive rolled on, led by the 88th Division. The 10th Mountain Division and the 85th Infantry Division pushed

Raft ferries a tank destroyer across the Po

on to Verona, and the 1st Armored Division helped to seal off all escape routes to the north with an enveloping sweep to the west. These moves, in conjunction with those of the Eighth Army, brought about the capitulation of the enemy and an end to the Italian campaign.

The Shortage of Engineers

From the landings at Salerno to the end of the war in Italy, a shortage of personnel affected practically all engineer work in Fifth Army and Peninsular Base Section areas. Experienced men were constantly drained off as the war progressed: too few engineers were allocated to the theater at the start; War

Department policies worked to the detriment of engineer strengths; units went to Seventh Army and the invasion of southern France; and the engineer contingent in Italy suffered casualties. The effect showed up not only in numbers but also in fluctuating training levels, varying proficiency in standard engineer functions, and problems of supply common to the theater. Not the least important for the engineers was the loss of experienced leaders.

In its search for skilled manpower, the War Department imposed strictures on the theaters in addition to the organizational one of the group concept. To build new engineer units around sound cadres the department often ordered experienced engineer officers home to

form a reserve pool of knowledgeable men for new units but did not replace them in overseas units with men of equal ability. Replacements in Italy were usually deficient in engineer backgrounds, and some had no technical knowledge at all. Between 6 October 1943 and 11 May 1944, forty-eight officers of company and field grade went back to the United States as cadre, General Bowman agreeing that they could be replaced by first and second lieutenants from training schools at home. Only some 50 percent arrived during that period, and the replacement system never made up the shortage. In the fall of 1944 the War Department stopped shipping individual engineer replacements, and the engineers turned to hastily trained elements such as antiaircraft gun crews left in rear areas, usually ports, to protect traffic there from nonexistent Axis air raids. From September 1944 to April 1945, new engineer units formed from nonengineer organizations included three combat battalions, one light equipment company, one depot company, one maintenance company, two engineer combat group headquarters, and two general service regiments. One general service regiment and two combat engineer regiments already existing became group organizations, and another two general service regiments were reorganized under new tables of organization and equipment. But with the exception of some separate companies, none of the new units ever attained its authorized strength. The constant rotation of officers to the United States reduced some of the existing units to 85 percent of their usual strength.

The number of engineer units drawn off by the Seventh Army in the spring of 1944 was somewhat counterbalanced by the reduction of Fifth Army’s responsibilities when the British Eighth Army took over a major part of the front. But the units lost at the time were what remained of the best, for General Clark allowed Seventh Army to take any engineer unit it wanted.

Casualties also took an expected toll. Of the peak engineer strength of 27,000 in June 1944, 3,540 officers and men were lost. Of the 831 who died, 597 were killed in action, 140 died from wounds received in action, and 94 died from other causes. Of the 2,646 wounded in action, 786 were wounded seriously and 1,860 only slightly. Some thirty-six were taken prisoner, and thirty remained missing in action. The numbers varied from unit to unit depending on proximity to the front line and the type of work performed. In forty-five days of combat at Anzio, the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment lost 74 men killed and 336 wounded. On the same front, where it was difficult to distinguish front lines from rear, the 383rd Battalion (Separate) in five months sustained casualties of four officers and eleven enlisted men killed and three officers and fifty-eight men wounded. Enemy artillery brought down the most engineers. For example, the 109th Combat Battalion between 20 September 1943 and 11 May 1944 had seventy-one battle casualties, 90 percent from artillery blasts or shell fragments, and 10 percent from mine blasts and small-arms fire. At other times the losses from artillery were fewer, as low as 61 percent, but artillery always remained the chief culprit.44

Training

To offset inexperience, the engineers concentrated on training troops coming into the North African theater. Units had no choice but to accept troops without engineer training, and they took men with only basic military training. They had to be satisfied, in fact, with only a small percentage of Class II personnel (categorized as rapid learners in induction tests), with the remainder Class III (average learners) and Class IV (slow learners). New officers were assigned to four to six weeks of duty with rear area general service engineer units before being thrust into work with combat engineers.

Each engineer unit tried to maintain a reserve of trained specialists to fill any vacancies that occurred and to keep up job training. Even so, engineer units in the Fifth Army did not have enough trained operators and mechanics, especially for heavy equipment. A good operator could do three to five times the work of a poor one.

Training in bridging, river crossing, mine techniques, heavy equipment, motor maintenance, surveying, intelligence techniques, mapping, photography, scouting and patrolling, mountain climbing, driving, marksmanship, and the use of flame throwers and grenade launchers went on throughout the campaign, most of it within the engineer groups, regiments, battalions, or companies. Many units trained at night. For example, the 19th Engineer Combat Regiment, before the spring offensive of May 1944, spent a third of its training time on night practices. One company of a battalion might perform assigned missions while the rest of the battalion trained.45

When the time was available, almost every unit practiced bridge construction. The 235th Engineer Combat Battalion spent five days at the Arno building floating treadways. Experienced units trained the inexperienced: the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion instructed the 36th and 39th Engineer Combat Regiments and the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion in building steel treadways, and the 1755th Treadway Bridge Company trained a number of units, including the 19th Engineer Combat Regiment. In August and September 1944 the 175th Engineer General Service Regiment conducted a school for the British in building timber bridges. In April 1944 each company of the 310th Engineer Combat Battalion, 85th Division, built and dismantled a 100-foot double-single Bailey.

As early as November 1943 Fifth Army established a school in river crossing at Limatola, near the Volturno, and here a number of units practiced for the Rapido crossing. During a fortnight in January 1944 the 16th Armored Engineer Battalion practiced assault crossings with the 6th Armored Infantry Regiment, 1st Armored Division. Four companies of the 19th Engineer Combat Regiment practiced between 10 and 15 January 1944 with elements of the 36th Division at Pietravairano, sixteen miles north of Capua, instructing the infantry in the use of river-crossing equipment during both daylight and darkness. The engineers conducted similar training in preparation for the Arno and Po crossings.

Engineers also learned by attachment. Units just arriving in the Fifth Army zone sent officers and enlisted men—or whole units—to work with, observe, and learn from engineers who were more experienced. Elements of the 310th Engineer Combat Battalion were attached to the 313th Combat Battalion, elements of the 316th Combat Battalion to the 10th and 111th Combat Battalions, and elements of the 48th Combat Battalion to the 120th Combat Battalion.

The engineers also instructed nonengineer units in a number of other skills, most notably recognizing, laying, detecting, and removing mines. Two Fifth Army engineer mine-training teams supplemented the instruction that divisional engineer battalions gave to the infantry. The 16th Armored Engineer Battalion subjected the 92nd Division to rigorous drill, requiring the whole division to go through a live minefield.

Early in the campaign the British established a Bailey bridge school, open to Americans, at Capua, where some units felt the instruction was better than that provided at the American school.46 Americans gave some supplementary instruction at the British School of Military Engineering at Capua. Most of the American schools in the theater were subordinate to the Replacement and Training Command, MTOUSA. In the summer of 1944 MTOUSA established an American Engineer Mines and Bridge School along the Volturno in the vicinity of Maddaloni. As the Fifth Army moved northward and out of touch, the school shifted its emphasis to converting American antiaircraft artillery (AAA) troops into engineers and to training the Brazilian Expeditionary Force and the 92nd Division.47

Lacking engineer troops, Fifth Army employed thousands of Italians. Some Italian engineer troops participated in the campaign, but most of the laborers were civilians who bolstered almost all the U.S. Army engineer units, especially those at army and corps level. Each unit recruited its own civilian force with help from Allied military government detachments. At one time the 310th Engineer Combat Battalion had more than three times its own strength in civilian laborers. The work of the Italians, while not always up to the standard desired by the American engineers, released thousands of engineers and infantrymen for other tasks. Some three thousand manual laborers worked for the engineers during the winter of 1944-45; in April 1945 army and corps engineer units had employed 4,437 Italian civilians, most of them on road work. The Italians loaded, broke, and spread rock; worked at quarries; cleared ditches and culverts for use of mule pack trains; and hand-placed rock to build up firm shoulders and form gutters. Those more skilled rebuilt retaining walls and masonry ditches along road shoulders.48

A specialized Italian civilian group, the Cantonieri, was the equivalent of U.S. county or local road workers. These

workers became available as the front lines moved forward and were especially valuable in rapidly moving situations when engineer road responsibilities increased by leaps and bounds. The chief of the Cantonieri of a given area did the same tasks on his section of road (about twelve miles) that he had done for his government. Truckloads of crushed rock and asphalt were unloaded along the road as required, and the Cantonieri patched pavements and did drainage and other repair jobs.49

Engineer Supply

Fifth Army was not in Italy long before defects in the engineer supply system became evident. The engineers acted rapidly on the invasion plans that called for them to make the most use possible of locally procured material. Soon after Naples fell, reconnaissance parties scoured the area for supplies, making detailed inventories of plumbing and electrical fixtures, hardware, nails, glass, and other small standard items. Italian military stocks, especially those at the Fontanelle caves, were valuable sources of needed materiel, and prefabricated Italian barracks served as hospital wards until American huts arrived. Though American engineers sequestered and classified over a hundred different types of stock and placed orders on Italian industry through the Allied military government that spurred the local economy and saved critical shipping space, control of requisition and issue of supply suffered from too few qualified men.50

The strain was particularly manifest closer to the combat elements. No organization existed at Fifth Army corps or division levels to allocate engineer supply, and the individual units drew directly from army engineer depots. Though the Fifth Army engineer tried to keep the dumps as far forward as possible, the using units had to send their own trucks back to collect supplies since the depots frequently did not have the transportation to make deliveries. The time needed for supply runs varied with the distances involved, the road conditions, and the frequent necessity for traveling blacked out. The average was one day, but the 313th Engineer Combat Battalion reported that trips of up to 250 miles required two days for the round trip.51

Many engineer units could ill afford either the time or the transportation required for frequent trips back to army dumps, so they began to maintain small dumps of their own, stocking them with supplies from army engineer dumps and with material captured or procured locally. The only condition Fifth Army imposed on these dumps was that all stocks be movable. It was common practice for each company of a divisional engineer combat battalion to set up a forward dump in the infantry regimental sector, and such dumps often leapfrogged forward as the division moved. In the 45th Division, the 120th Engineer Combat Battalion in a mobile situation always kept its dump about 1½ miles behind its own command post.52

There were never enough depot troops to operate army engineer supply dumps. Before the breakout in May 1944 Fifth Army had only one platoon (one officer and forty enlisted men) of the 451st Engineer Depot Company, while the rest of the company remained with PBS. The platoon had to move often to stay close to the front but still managed to fill an average of seventy-five requisitions every twenty-four hours. Frequently, the platoon operated more than one depot simultaneously—three in May 1944. When the 451st concentrated at Civitavecchia in June, it took 500 trucks, enough for seven full-strength infantry regiments, to move the unit’s stock and equipment north. Help in depot operations came from other engineers as well as from British, French, and Italian military units. Several companies of Italian soldiers were regularly attached to the 1st Platoon as mechanics, welders, carpenters, and laborers. Italian salvage crews repaired tools and equipment, manufactured bridge pins, and mended rubber boats.53

The shortage of engineer depot units made it impossible to open new engineer dumps as often or as rapidly as desirable, particularly after the May 1944 breakout. As a result the supply furnished to engineer units deteriorated, and in June one platoon of the 450th Engineer Depot Company had to be made available to Fifth Army. In August, however, the platoon reverted to Seventh Army, and for the next few months Fifth Army again had only one platoon for engineer depot support. Finally, in December 1944, MTOUSA formed the 383rd Engineer Depot Company from the 1st Platoon, 451st, and men from disbanded antiaircraft units. Through the rest of the campaign Fifth Army engineer units could count on supply support from this company, aided by Italian Army troops trained in engineer supply procedures.54

Mapping and Intelligence

Planners had estimated that Fifth Army would need a full topographic battalion, plus one topographic company per corps, to reproduce and revise maps; yet there were never more than two topographical companies available at any one time. The 66th Engineer Topographic Company served for nineteen months; the 661st served only eight months, mainly with VI Corps. Both, from time to time, had to get help from South African and British survey companies.55

The 66th Topographic Company was the American unit on which Fifth Army placed its chief reliance. Upon arrival in Italy in early October 1943, the men of this unit went to work revising material derived chiefly from aerial photographs. Photo mosaics and detailed defense studies covering the projected attacks along the Volturno and Sacco–Liri Rivers were made and reproduced.

In November the 66th was assigned to II Corps but continued to revise and reproduce maps for the Fifth Army Engineer Section. This company consisted of four platoons: a headquarters or service platoon; a survey platoon, which as a field unit performed the sur-

vey and control work; a photomapping platoon responsible for drafting as well as planning and revising maps; and a reproduction platoon responsible for the lithographic production of the printed sheet. In January 1944 the company furnished men for two provisional engineer map depot detachments, one at Anzio and the other on the main front. When the two fronts merged in May it was possible to establish forward and rear map depots, and NATOUSA formally activated the 1710th and 1712th Engineer Map Depot Detachments.

The 66th Topographic Company moved twelve times between 5 October 1943 and the fall of Rome in June 1944. Between those dates the company processed an average of a half million impressions a month. In addition to 866 different maps, the 66th printed field orders, overlays showing engineer responsibilities, road network overlays, defense overprints, German plans for Cassino defense, a monthly history of II Corps’ operations, the disposition of German troops in the II Corps area, special maps for the commanding general of II Corps, special terrain studies, photomaps, and various posters and booklets. It produced a major portion of all the 1:100,000, 1:50,000, and 1:25,000 maps Fifth Army units used. In April 1945, for the Po operation, the 66th produced 4,900,000 operational maps, working around the clock and using cub planes to speed distribution to units.56

After the fall of Rome the 66th Topographic Company, then the only such unit with Fifth Army, could not produce the required amount of work with its authorized personnel and equipment. The company procured additional equipment and employed Italian technicians and guards, virtually becoming a topographic battalion. Using the Italian technicians, the company was able to work two shifts reproducing maps but could not get enough people for two shifts on other jobs. The company trained its men for several different specialties, but the multiple responsibilities overtaxed them.

The 1712th Detachment issued 1,331,000 maps for the drive against the Gustav Line in May 1944. For the entire Italian campaign Fifth Army handled and distributed over 29,606,000 maps. Ordinarily the corps maintained a stock of 500 each of all 1:25,000 and 1:50,000 sheets of an area and fewer 1:100,000 and smaller scale sheets. When new units arrived or large orders came in, the maps were drawn from the army map depot; such orders could normally be filled within a day. Periods of relatively static warfare in the Italian campaign called for large-scale maps. Unfortunately, not enough 1:25,000-scale maps were available to meet the need, and some of those in stock were of dubious quality. The 1:50,000-scale maps provided complete coverage, but many panels were considerably out-of-date and in some cases illegible.

The combined sections of mapping and intelligence collected data on weather, crossing sites, defense works, observation points, and fields of fire. When Lt. Col. William L. Jones joined Bowman’s staff in January 1944, intelligence became divorced from mapping, and Jones became chief of the Plans, Intelligence, and Training Section. This arrangement continued until September

1944 when Colonel Jones left to take command of the 235th Engineer Combat Battalion; then mapping and intelligence reconsolidated under Lt. Col. John G. Ladd.57

Information came to the section from many sources, including the Army Map Service and other agencies in the United States and Britain. The Intelligence Branch, OCE, WD, supplied a ten-volume work on Italy’s beaches and ports covering such subjects as meteorological conditions and water supply. Many studies dealing with Italy’s highway bridges, railroad bridges, and tunnels originated in the Research Office, a subdivision of the Intelligence Branch. A valuable source from which the engineers derived information was a sixteen-volume Rockefeller Foundation work on malaria in Italy with specific information concerning the regions where malaria prevailed. Lessons, hints, and tips came from two series of publications issued frequently during the campaign: Fifth Army Engineer Notes and AFHQ Intelligence Summaries.58

Although the Fifth Army G-2 was technically the agency for collecting and disseminating topographic information, the Fifth Army staff relied on the engineer to evaluate all topographic intelligence required for planning. This system worked well, for by the nature of his work and training the engineer was best equipped to provide advice concerning terrain and communication routes. Corps and division staffs generally expected less terrain information from their engineers because no adequate photo-interpretation organization existed below the army level. Engineer intelligence data seldom covered terrain more than one hundred miles in advance of the front lines. On the whole intelligence was adequate, for the rate of advance in Italy was not rapid enough to require greater coverage. The timing of engineer intelligence was important; information conveyed to the lower units too far in advance might be filed away and forgotten.59

Skilled interpretation of aerial photographs was an important phase-of engineer intelligence. Use of such photographs, begun in the stalemate before Cassino, proved so valuable that by February 1944 a squadron of USAAF P-38s made four to ten sorties (about 350 pictures) daily. Two engineers at the photo center sent all photographs within ten miles of the front forward and kept the rest for their own study. Periodically they also sent forward reports on roads, bridges, streams, and other features.60

The engineers used long-range terrain reports of the AFHQ Engineer Intelligence Section to plan the forward movement of engineer bridge supplies and the deployment of engineer units. The reports were rich sources of information on roads and rivers. Road information included width, nature of surface, embankments, demolitions, and suitability for mules, jeeps, or other transportation. River information included bed width, wet gap, width measured from the tops of banks, nature and height of banks, levees, potential crossing places, approaches, needed

bridging equipment, fords, and practicability of bypasses. The error was seldom more than ten feet for estimated bridge lengths or 20 percent for bridge heights. Sometimes the terrain reports were useful in selecting bombing targets such as a dam in the Liri valley. They could be used not only to estimate long-range bridging requirements but also to anticipate floods, pinpoint tank obstacles and minefields, and locate potential main supply routes, airfield sites, strategic points for demolition, and possible traffic blocks. General Bowman was so impressed by the value of the reports that he tried repeatedly to have the AFHQ Engineer Photo Interpretation Section made part of his office, but AFHQ retained control of the section.61

Camouflage

At no time during the entire Italian campaign were there more than two companies of the 84th Engineer Camouflage Battalion available, and after the middle of 1944 only one company remained with Fifth Army. Moreover, since in the United States camouflage troops had been considered noncombatant, the unit, responsible for camouflage supervision and inspection, consisted of limited service and older-than-average personnel. This policy impaired efficiency in view of the fact that frontline units had the greatest need for deception and disguise. In addition, the camouflage companies had neither enough training in tactical camouflage nor enough transportation to move the large amount of materials and equipment required.62

In spite of these handicaps engineers did some excellent work with dummies, paint, nets, and other materials. Sometimes road screens and dummies confused and diverted enemy artillery posted in the hills. For example, early in the campaign, troops of the 337th Engineer General Service Regiment erected a series of structures made from nine 30-by-30-foot nets, along a 220-foot stretch of road near the Volturno. This section had been subject to observation and shelling, but after the erection of the road screen the shelling stopped.63

Road screens were the main device in camouflage operations. As a rule the engineers used a double thickness of garnished net, but the best type of net for all purposes remained an unsettled question. Engineers of the 84th Battalion preferred shrimp nets to garnished twine, yet the 15th Army Group engineer concluded at the close of hostilities that the shrimp nets had not been dense enough to obscure properly. Pre-garnished fish nets had the same defect. None of the nets was sufficiently durable or fire resistant. And as snow fell in December 1944, no white camouflage materials were available.64

The most ambitious operational camouflage programs of the Italian campaign took place during preparations to attack the Gothic Line. Engineers

made every effort to conceal the II Corps buildup in the Empoli–Florence area and to simulate strength on the left flank in IV Corps’ Pontedera sector. Among the devices employed were dummy bridges over canals and streams and smoke to make the enemy believe that heavy traffic was moving over the dummy bridges. One dummy bridge at a canal southwest of Pisa drew heavy fire for two hours.65 In October 1944 in the IV Corps area, engineers raised a screen to enable them to build a 120-foot floating treadway across the Serchio during the daytime. During the same month Company D of the 84th Camouflage Battalion erected a screen 300 feet long to conceal all movement across a ponton bridge that lay under direct enemy observation. The engineers put up a forty-foot tripod on each bank of the river, used holdfasts to secure cables, and raised the screen with a ¾-ton weapons carrier winch and block and tackle. In November a bridge over the Reno River at Silla, also exposed to enemy observation, was screened in a similar fashion. Here the engineers used houses on the two riverbanks as holdfasts.66

Engineers set up dummy targets at bridge sites, river crossings, airstrips, and at various other locations, building them in such shapes as artillery pieces, tanks, bridges, and aircraft. They were used to draw enemy fire to evaluate its volume and origin. They also served to conceal weakness at certain points, to permit the withdrawal of strong elements, and to conceal buildups. When a shortage of dummy material developed in January 1945, planners looked upon it as a serious handicap to tactical operations.67

Dummies and disguises took many forms. Large oil storage tanks became houses. Company D used spun glass to blend corps and division artillery with surrounding snow. The engineers used painted shelter halfs and nets with bleached garlands to disguise gun positions, ammunition pits, parapets, and other emplacements. Camouflage proved valuable enough in many instances to indicate that its wider application could have resulted in lower casualties and easier troop movements.68

Behind Fifth Army in Italy, a massive work of reconstruction continued as divisions moved forward against a slowly retreating enemy. In the zones around the major ports on the western side of the peninsula and on the routes of supply to the army’s rear area, the base section made its own contribution to the war. Suffering many of the same strictures and shortages as Fifth Army engineers, the Peninsular Base Section Engineer Service carried its own responsibilities, guaranteeing the smooth transfer of men and material from dockside to fighting front. A host of supporting functions also fell to the engineer in the base section, often taxing strength and ingenuity to the same degree as among the combat elements.