Chapter 12: Reviving BOLERO in the United Kingdom

The decisions at the TRIDENT Conference in May 1943—to undertake a strategic bombing campaign leading up to a cross-Channel invasion with a target date of 1 May 1944 while continuing operations in the Mediterranean—rescued BOLERO from the doldrums into which it had fallen as a result of the diversions to North Africa. To be sure, the drain of the continuing campaigns in the Mediterranean and the British seeming reluctance to sacrifice those campaigns to a cross-Channel operation left some doubt in American. minds that the operations would be executed in a timely manner. Accordingly, for some months after TRIDENT the buildup proceeded haltingly and under relatively low priority. The appearance in July of an outline plan for the operation, now designated OVERLORD, and the acceptance of that plan at the Quebec Conference (QUADRANT) in August produced new momentum in the fall of 1943. But only the final resolution of all doubts at the meetings at Cairo-Tehran (SEXTANT) at the very end of the year gave BOLERO the top priority that would reawaken the buildup in the United Kingdom.1

ETOUSA engineers were essential to the buildup. They had to construct depots and camps to house the flood of incoming men and supplies, build the airfields from which preinvasion air strikes would be launched, and prepare plans and stockpile supplies for the engineer role in the invasion itself.2

The bases for planning the construction program during 1943 remained the BOLERO Key Plans, and they changed as the OVERLORD concept developed. Engineer planning late in 1942 was based on the third BOLERO Key Plan, which held preparations for a full-scale invasion in abeyance although it prescribed a vague goal of 1,049,000 men in England with no firm target date. As early as January 1943 Col. Cecil R. Moore, the ETOUSA chief engineer, directed base section engineers to return to the second BOLERO Key Plan as a guide and to use its troop basis of 1,118,000 men with a completion date of 31 December 1943.3 The TRIDENT decisions produced firmer data to work

Except where otherwise indicated the account that follows is based on this volume.

with, and on 12 July 1943, a fourth BOLERO Key Plan set the troop basis at 1,340,000 men to be in Britain by 1 May 1944. On the basis of decisions at the Quebec Conference in August the British War Office (with the advice of the American staff) on 30 October 1943 issued an amended version of the fourth plan, setting the goal at 1,446,000 U.S. officers and enlisted men to be in the United Kingdom by 30 April 1944. This was the last of the key plans within which the engineer supply and construction programs proceeded.

The Continuing Problem of Organization

The organizational framework within which the engineers operated—specifically the division of function between the theater headquarters and the SOS—continued to cause problems during 1943. As Commanding General, SOS, Maj. Gen. John C. H. Lee continued the drive he had begun in 1942 to bring all supply and administration in the theater under his control. He continued to meet determined resistance from those who insisted that the theater staff must remain responsible for theater-wide policy and planning for future operations and that the chiefs of services in particular must serve the theater commander directly in these areas even if their services were part of the SOS. Until the very end of the year compromise arrangements prevailed, but none of them were entirely satisfactory for the performance of engineer functions.

The duplication of functions created by moving SOS headquarters to Cheltenham in May 1942 persisted after Lt.

Gen. Frank M. Andrews replaced General Eisenhower as theater commander on 6 February 1943, and to a lesser degree after Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers replaced Andrews, who died in a plane crash on 3 May 1943.4 In early March of that year Lee proposed to Andrews that he, Lee, be designated deputy theater commander for supply and administration as well as commanding general, SOS, with the theater G-4 and all the chiefs of the technical and administrative services serving under him in his dual capacity. The solution was not unlike that adopted eventually, but at the time Andrews rejected the scheme. He insisted that planning for future operations, a function of the theater headquarters, should remain separate from administration and supply of troops in the British 1sles, a function of the SOS. Although he granted Lee more control over the chiefs of services, he also specified that they be ready to serve the theater commander immediately if needed. At the same time, he moved the whole SOS headquarters back to London close to ETOUSA.5 While SOS planning came to be centered in London, an SOS deputy commander handled operations at Cheltenham. The operating echelons of the technical services remained at Cheltenham, and chiefs still had to spend some time there.

General Devers lent a more willing ear to Lee’s arguments and vested the commanding general, SOS, with the office of the G-4 on the theater staff.

An ETOUSA order of 27 May 1943 gave Lee in this dual role jurisdiction over all supply concerns of the theater and divided his SOS command between

two equal chiefs of theater service functions, one for administration and one for services. The seven technical services, including the engineers, lumped together with a purchasing service and a new theater area petroleum service, then had a chain of access to the theater commander running through Col. Royal B. Lord as chief of services, SOS, and General Lee himself as surrogate theater G-4.6 Except for the limited consolidation involved in the G-4 position, ETOUSA and SOS staffs continued as separate entities, and the chiefs of services continued in dual roles in the two headquarters. Even this limited consolidation suffered a setback when the G-4 position on the ETOUSA staff was removed from the SOS commander and given to Maj. Gen. Robert W. Crawford between 8 October and 1 December 1943.7

On 1 December General Crawford moved to the Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), a provisional Allied staff planning the invasion pending the establishment of a command for that purpose. General Lee then assumed the position of G-4, ETOUSA, again. Another month brought the realization of his proposals of early 1943. The expansion of the COSSAC role in England and the establishment of active field, army, and army group commands in England reduced the ETOUSA administrative and long-range planning function to little more than that of the SOS, ETOUSA, command. In effect, the two separate headquarters existed for the same reason and shared the same special staff, which included the engineers. When General Eisenhower resumed command of the American theater and of the new Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), which succeeded COSSAC on 15 January 1944, the ETOUSA and SOS staffs were consolidated. At the same time, General Lee assumed the formal title of deputy theater commander, in which capacity he was to act for General Eisenhower in all theater administrative and service matters.8

The consolidation reduced the duplication and inconsistencies and relieved the confusion that had characterized supply and administrative channels in 1943. It provided the basis for organizing an American Communications Zone command for operations on the Continent. But the organizational picture was still complicated and command relationships confusing. Theoretically General Lee’s ETOUSA-COMZ staff served General Eisenhower in his role as American theater commander while his Allied staff served him in his role as supreme commander, Allied Expeditionary Force. Senior American field commanders tended to regard Lee’s headquarters as strictly an SOS or Communications Zone headquarters, equal to but not above their own headquarters and equally subject to Eisenhower’s directions as supreme Allied commander. They never accepted Lee’s role as deputy theater commander and succeeded in having it abolished in August 1944.

In a sense the ETOUSA-SOS relationship with the Allied SHAEF command created some of the same problems that had characterized the relationship of SOS and ETOUSA because

General Moore (photograph taken in 1945)

Eisenhower sometimes used the American component of the SHAEF staff as an American theater staff. General Moore’s misgivings about the command on the eve of the invasion were common among his fellow technical service chiefs. The continued assignment of the Engineer Service under the SOS made the other elements in the theater regard the chief engineer as part of a “co-ordinate command and not one that had authority or supervision over their commands.”9

The command arrangements in the theater thus remained unsatisfactory to the Engineer Service throughout the buildup and preparation for the invasion. In manpower problems alone, Moore’s headaches in bidding against other services for skilled men and in allocating work forces increased since he could not always exercise the weight and the rank of a theater commander’s name in his own behalf. Equally difficult was engineer supply in the theater.

New Supply Procedures

When the buildup in England was expressed in terms of troop ceilings in the high-level international conferences of spring and summer 1943, the figures automatically implied demands for increased shipments of engineer supply and equipment. General Moore’s SOS Engineer Service would have to plan not only for accommodations for the incoming men but also for protection and depot warehousing for both current operating supply and invasion materiel. The early part of 1943 saw the influx of comparatively small numbers of troops, primarily Air Corps reinforcements for the stepped-up aerial offensive. Later arrivals would require coordination of construction and supply functions, but the OCE Construction and Quartering Division had moved back to London in General Andrews’ separation of planning and operating staffs in March 1943, leaving the Supply Division at SOS headquarters, ninety miles away. The division nevertheless contributed to some attempts at improving the supply flow to the United Kingdom, among them a program of preshipping unit equipment and new methods of marking shipments for destinations in England.

Until the summer of 1943, engineer

units arriving from the United States brought their organic equipment with them. After 1 July they turned in all their equipment except necessary housekeeping supplies at their port of embarkation and upon reaching the United Kingdom drew new equipment, including supplemental maintenance supplies, from stocks previously shipped from the United States. The preshipment program took into account the probability that larger numbers of troops would arrive in England in late 1943 and early 1944 and sought to avoid overtaxing British port capacity and inland transportation nets with both troops and cargo by shipping the cargo beforehand. It also would permit British and American dock crews to take advantage of the long summer days for unloading.

But the limitations of the preshipment program immediately made themselves felt. Interpretations of the supply flow differed from the start. The European theater command perceived the system as a guarantee that bulk stocks would arrive before using troops docked in Great Britain, where they would immediately pick up TBA material and draw other needed supply, but not necessarily the same items they surrendered before leaving the United States. War Department interpretations relied at first on force-marking, under which units were to recover the same equipment they had turned in at home. Begun under constraints arising from little excess supply in American inventories and training schedules that prevented units from giving up equipment until just before they sailed, preshipment from May to August 1943 was primarily a vain struggle to fill available shipping space.

The priority system established for supplying Army Ground Forces in England also hobbled the program, with ETO supply occupying eighth place in the order of shipping importance in the United States. Until after SEXTANT the War Department was reluctant to change the priority for a theater that had no clear-cut and overriding strategic precedence. By the time Army Service Forces arguments produced a higher priority in November 1943, troop sailings rivaled those of preshipped cargo and shipping space went to troops and their personal gear.

The advance flow of heavier equipment for engineer work suffered from the uncertain supply policy in effect throughout 1943.10 During July and August of that year General Moore complained that bulk-shipped TBA items arrived in the United Kingdom long after engineer units. In that period 75,000 engineer troops reached the theater to find that only 5 percent of their organizational equipment was waiting for them. As a result, most of the units could not contribute to the general construction program or even train effectively.11 Receipt of bulk TBA equipment improved enough in September 1943 to take care of the units arriving that month but was not sufficient to replenish reserve stocks depleted during the two previous months. Eventually, engineer troops received standard equipment within seven to ten days after they arrived instead of the sixty to ninety days common under the old system.12

Many engineer items shipped from the United States were poorly marked; some even lacked service identification marks. Of 3,920 items of prefabricated hutting more than 300 could not be used, largely because so many parts had been mixed together.13 Supply processes improved for the engineers—and for other troops in the ETO—when SOS changed the UGLY marking system evolved in 1942. Under that system the first element in cargo identification, the code word UGLY, indicated the ETO; the second element indicated the supply service making the shipment; and the third indicated the class of supplies. Thus, engineer Class II supplied going to the ETO were marked UGLYENGRSII.

Early in 1943, SOS and the British refined this system with the aim of eliminating long rail hauls from the ports. They divided the United Kingdom into three zones: Zone I, Northern England, identified by the code word Soxo; Zone II, Bristol and London, called GLUE; and Zone III., Northern Ireland, called BANG. Thereafter, most cargo bore the shipping destination SOXO, GLUE, or BANG; UGLY indicated cargo not intended for any particular port in the United Kingdom. This system cut down reshipment from port to port, brought supplies to the correct depot sooner, relieved pressure on the already overloaded British rail system, and enabled supplies to be moved out of ports sooner—a necessity with German air raids an ever present danger. Manifests also improved, and the new ISS (Identification of Separate Shipments to Overseas Destinations) forms completely identified, in the third element of the UGLY address, separate shipments made against particular requisitions.

No amount of new markings could revise the shortages in large items of engineer equipment throughout 1943. One of the most important items was the dump truck; at late as September the engineers had 1,000 fewer than the standard tables of allocations called for. Heavy construction equipment, general-purpose vehicles, and cranes were in critically short supply well into 1944. Augers, semi-trailers, graders, shop equipment, tractors with angledozers, generators, various hand tools, asphalt paving equipment, and spare parts of all types fell into this category. On 30 April 1943, the backlog of engineer supply alone due in from the United States stood at 79,832 ship tons; by the end of August, it had increased to 124,224 tons.14

Construction

At the beginning of 1943 American engineers in the United Kingdom could not look back on an impressive construction record. They had built no hospitals, and although they had undertaken fourteen camp projects they had not completed any. They had worked on twelve airfields but none was more than 25 percent complete, and they had begun ten depots but none was finished. In one respect, however, the engineers had made considerable progress—they had learned, of necessity, how to work closely with the British.

Because all facilities would ultimately go back to the British, many plans and specifications the engineers used were British, and the British had to approve deviations. British materials also had to be used. Influencing construction standards and specifications were the small area available for military use; a shortage of lumber and a consequent reliance on steel, cement, and brick; and wet weather that produced continuous mud. Plans and procedures were affected by differences in diction, custom, and nomenclature; slow delivery of supplies; red tape and British centralization; and heavy reliance on civilians.15

Every project the engineers worked on had to be approved in the War Office by the Directorate of Quartering, the Directorate of Fortifications and Works, and by Works Finance which was made up entirely of civilians. The Construction Division, OCE, ETOUSA, had a liaison officer from the Directorate of Fortifications and Works; another, for a time, from the Directorate of Quartering; and a third from the Air Ministry Works Directorate. In turn, the division kept a liaison officer on duty with the Directorate of Fortifications and Works in the War Office.16

Getting standards for quarters and airfields approved was a problem, for in many cases American standards were higher than British. The increased cost per capita for U.S. forces was incomprehensible to the British Works Finance. Many projects were delayed fifteen to forty-five days while the British investigated the need for the work. Another cause for delay was failure to receive British supplies promptly. That tardiness and shortages, the engineers estimated, cut the effectiveness of American troop labor by 30 percent. Fortunately, matters improved in the later stages of the buildup.17

When General Moore directed the base section engineers to go back to the second Key Plan in February 1943, the BOLERO construction program was 29 percent complete. Priorities were air projects and depots, shops, and special projects, to be finished by 1 August 1943; accommodations previously planned, to be finished by 15 October 1943; and the hospital program, to be finished by 1 November 1943. Any additional accommodations were to be completed by the end of the year.18

The more rapid buildup under the fourth BOLERO Key Plan in July 1943 and its amendment in October stepped up all types of construction in the United Kingdom. New troop ceilings set at the international conferences raised the demand for construction far above that established for the 1,118,000-man limit in the second Key Plan without changing the basic construction priorities favoring airfields. The QUADRANT decisions, in anticipating OVERLORD, moved the staging areas for much of the invasion force from southern to southwestern England. Compared with the earlier construction demands, the work described in the fourth Key Plan expanded upon all previous work loads.

The July version of the plan specified 970,000 accommodations for incoming ground troops; the revised plan of October considered 1,060,000. Closed or covered storage and workshop space expanded from 15 million square feet in the third Key Plan to 18 million in the fourth plan and then to over 18 million in the amended fourth plan. Open storage, set at 26 million square feet in the third plan, rose to 34 million in the fourth but declined to 29,736,000 in the amended version. Petroleum products requirements rose from 130,000 tons in July to 234,000 tons in October; ammunition from 244,000 tons to 432,000 tons and then to 452,000 tons in the amended fourth plan, all requiring special handling and storage.19

To meet deadlines under the new programs, the engineers had to limit construction to the bare necessities. Safety factors were at the minimum for the importance of the structure, while durability, cost, and appearance became minor considerations.20 The new construction largely ignored camouflage. Camps frequently went up in parade ground style, in open spaces and straight lines, adjacent to prominent landmarks. Bulldozer tracks and construction materials, supplies, and equipment left in open fields attracted German bombers.21

The English winter created its own set of construction problems. There were only eight hours of light each day, and using searchlights at night risked drawing German aircraft. Many men were stricken with colds, respiratory diseases, and other ailments in the damp weather. Every site had to be well drained, or the engineers and their equipment soon bogged down in mud.22

Determining when a construction project was finished became perplexing. Two interpretations were possible—when the contract was fulfilled or when the using service declared the job complete. The first criterion was complicated by extras that might or might not affect the usefulness of the particular facility. Some items such as work ramps, added after an original contract, upset completion schedules yet did not materially delay when a facility could be used. At the insistence of the chief engineer, progress reports reflected physical completion, including extra work authorized during construction, rather than availability of facilities.23

By the end of May 1944 the construction program was 97.5 percent complete except for hospitals and continuous maintenance (especially at airfields). Depots were 99.6 percent complete; accommodations, 98 percent; and hospitals, 93.9 percent. The estimated value of installations provided by American forces in the United Kingdom as of 31 May was $991,441,000. New British construction cost an estimated $668,000,000. Of this total

Petroleum, Oil, and Lubricants depot, Lancashire

$502,000,000 ($262,000,000 acquired, $240,000,000 constructed) involved air forces installations; $166,800,000 involved hospitals ($151,200,000 for new construction and $15,600,000 for acquired). Some $41,174,000 went to depots, all but $4,374,000 to new construction. The entire construction program encompassed 150,000 buildings and 50,000 tents.24

Depots

In November and December 1942 and January 1943 the chief engineer had cut back the depot program in ETOUSA and deferred work on some depots and shops. In February 1943, after the Casablanca Conference, General Moore called upon the base section engineers to produce firth building plans. The fourth Key Plan called for the completion of the depot program by 31 March 1944, and its 18 million square feet of covered storage space was 20 percent more than in the second Key Plan.25 By the time the fourth plan was announced in July

1943, 13,398,000 square feet were ready. Open storage, which was to total 34 million square feet, then amounted to 27 million. In addition, space was to be provided for 432,000 long tons of ammunition and 215,000 long tons of POL.

Until well into 1943, the various services requiring depot space changed their requests from day to day. The British might move out of a selected depot site only to have the asking service turn down the site after all. In some such instances British civilian concerns had been put out of business in order to make facilities available.26 But much of the work and storage space the British provided was hard to adapt to modern American methods. Many of the depots were too low and doors too narrow; many multistoried buildings had either very small elevators or none at all. Some of the depots were far inland and had only tenuous access to the ports from which the OVERLORD operation was to be mounted. To make requisitions coming from other technical services more orderly and consistent, Colonel Lord required them to designate liaison officers to the engineers managing the depot construction and acquisition program, but requirements continued to change and some difficulties with site selection persisted.27

As one answer to the time, labor, and construction materials problems, the chief engineer planned to use open fields for storage space whenever practicable. In most cases roads and rail lines had to be brought to the site and the ground conditioned to provide rapid drainage. The damp English climate was hard on the poorly packed supplies coming from the United States. These factors and difficulties in using British facilities made it necessary to raise estimates for covered storage.

The depot program was not finished by the end of 1943. However, by 1 May 1944, only 29,673 square feet of covered storage in Southern Base Section (SBS) and 1,200,000 square feet of open storage in Western Base Section (WBS) were lacking. At the end of that month all but 7 percent of the work had been completed.28

Within the depots the American forces used several types of buildings. One of the first they tried was the Iris, a 35-foot-wide Nissen hut. The Nissen, a British development, was an igloo-like half cylinder made of steel. More successful was the Romney hut, similar to the Nissen but with a heavier frame. With special bolting the Romney proved to be an exceptionally tight structure. The Romney huts often had set-in windows, twelve on each side. The end walls were of brick, concrete, or, preferably, sheeting, which permitted the use of sliding doors as well as a small access door. The foundation was continuous plain concrete footing, with an eight-inch brick foundation extending a minimum of four inches aboveground. The floor was five inches of concrete on four inches of gravel fill. The concrete apron that joined the building to a railroad siding was customarily six inches thick.

The largest warehouses were of Marston shedding which could provide rectangular buildings as large as 45-by-250 feet.

These consisted of structural steel frames, corrugated iron roofs, corrugated asbestos siding, and six-inch concrete floors. Large sliding doors were at each end. The higher ceiling in the Marstons made it possible to install two ten-ton overhead cranes. A railroad spur ran into one end of the buildings. Sometimes made of wood from packing boxes and composite board panels, the Marston structures were ordinarily 60 feet long with an 18½-foot span. The wooden buildings were cheap and easy to knock down and transport but were so light that they had to be repaired frequently. To save steel and wood, structures of curved asbestos and corrugated cement sheets with end walls of brick were also built. Some attempts were made to use precast concrete.29

About twenty-nine depots (each with an average of one hundred buildings) constituted the U.S. Army depot program in the United Kingdom. The construction of new covered storage and the expansion of existing facilities accounted for about one-fourth of the total space, while about one-half of the open storage and hardstandings was derived from new facilities and expansion. The estimated value of acquired depots was $4,374,000; that of new depots $36,800,000. Of covered storage and shop space the British turned over 67 percent and constructed 20 percent; American engineers built 13 percent. Of open storage and hard-standings the British turned over 51 percent and built 13 percent while U.S. Army engineers provided 36 percent. For storing ammunition the British turned over facilities to handle 33 percent of the job and constructed 27 percent; American engineers constructed 40 percent. Providing depot space for POL was largely an engineer job, with the British contributing only 5 percent (3 percent in space turned over and 2 percent in new construction).30

Accommodations

The first Key Plan did not provide for camp construction, for the British were to make available the necessary 845,200 winterized accommodations. The second Key Plan did not break down the number of hut and tent camps that would have to be erected but mentioned a total of 845,000. In January 1943 ETOUSA announced that all small camp expansions that were 50 percent or more complete could be finished; work on all others was to stop, at least temporarily.31 At the end of January some 65,000 spaces of the 137,000 to be provided by camp expansions and new hutted camps were ready for use. More than 543,000 spaces already were available, for a total of slightly more than 600,000. The following month ETOUSA directed that accommodations be completed by 15 October 1943, and any needed thereafter by 1 December 1943.32

In January 1943 the British and Americans designated G-3, ETOUSA, to supervise the preparation of a monthly priority list showing the units

to arrive in the ETO within the next month or within a longer period if such data were available. Called long-term forecast, the lists were derived from information the War Department provided and from a convoy program the British quartermaster general prepared. At the same time the Allies agreed that each British military command would provide holding areas for American units whose final locations had not been determined and for units that arrived unexpectedly. The Air Forces did not have to determine destinations for units in these long-term forecasts but coordinated its needs with the Air Ministry, not with the American base sections or the War Office.

Early in February 1943 the Construction and Quartering Division of the theater engineer’s office drew up plans for quartering U.S. troops expected in the United Kingdom by the end of the year. These forces would be located with a view to their future operational roles and available facilities and training areas. They would be quartered in tents between 15 March and 15 October.

The quartering program did not make great strides in early 1943. Though the engineers were using overall estimates of 1,118,000 arrivals listed in the second Key Plan, they were still working against the total of 427,000 men established in the third Key Plan of November 1942 as a basis for calculating accommodations. Even this figure caused no sense of urgency; troops other than Air Forces were not arriving in any great numbers. Of the 5,244 men for whom quarters were found in April 1943, 4,873 were air personnel. Southern Base Section had at that time 380,000 covered accommodations. Army engineers constructed space for 60,000 and expanded existing structures to take 60,000 more. In July 1943 they widened the program to provide 82,000 spaces: 52,000 for air forces personnel, 27,000 for SOS troops, and 2,435 for ground forces increments. As of March 1943, no troops were housed under canvas.

The first of a series of joint monthly forecasts concerning the arrival of American troops in the United Kingdom appeared on 14 July 1943. From these engineers received word on units alerted in the United States for shipment to Europe but not always on sizes of convoys or timing of movements. News of a unit’s scheduled arrival sometimes reached England while the unit was at sea. As late as September General Moore could not get accurate information on unit destinations. In mid-October, when the amended fourth Key Plan had raised estimates for accommodations to 1,060,000, Moore finally could announce that he had a construction program for the phased arrival of the growing swell of ground force units.

By April 1944 the camp construction program had provided 1,296,890 accommodations in huts, tents, or billets. Of this figure, the British had turned over 40 percent and constructed for American use another 30 percent, leaving the remainder for American military construction crews. At the end of May 1944 the camps were 99.5 percent finished. A heavy concentration of tent cities, all in Southern Base Section, included 123,664 permanent tent accommodations and 49,302 temporary.33

Essential to providing quarters was determining living standards, which dictated space requirements. At first,

the U.S. Army accepted for its ground and air forces the respective British standards. This practice made for two scales, with the USAAF’s the higher.34 The accommodations provided officers under both standards were about the same, but the British provided thirty square feet per enlisted man and seventy-five per sergeant while the Americans provided thirty-five square feet per enlisted man regardless of grade. Taking over facilities from the British and making them meet U.S. Army standards usually involved renovations and minor alterations. In July 1943 Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, ETOUSA commander, concluded that the scale of accommodations for U.S. forces could be reduced to the British scale or its equivalent. The chief engineer and chief surgeon agreed that the best scheme was sixteen men per hut, or thirty-five square feet per noncom or enlisted man, and seventy-two square feet per officer. This “austerity scale” lay between the British and American standards.

The Construction and Quartering Division, OCE, ETOUSA, had a number of problems in carrying out its assignment. Frequently, units were unwilling to accept facilities the British offered, preferring newly constructed accommodations. Occasionally the services failed to turn in complete plans for quartering requirements, tending instead to submit their needs bit by bit. In addition, each time the staff of the using service changed, revised requirements arose, for each new section chief had his own ideas on the subject.35

American officers added to the confusion by not following prescribed channels in requesting facilities.

Two varieties of billets were common outside the camps: furnished lodgings, which included the use of toilet facilities, water, and lighting; and furnished lodgings in which the U.S. Army provided beds and the British water and lights. Although a British law required civilian householders to provide shelter for troops at a fixed rate, private billeting was on an entirely voluntary basis until the end of 1943. With the fourth Key Plan billeting became systematized, and some forced billeting occurred.

Hospitals

In early 1942 the American forces used British and Canadian hospital services and operated a few British hospitals themselves. Members of the British Directorate of Fortifications and Works, the Ministry of Works and Planning, the U.S. Medical Department, and the Engineer Service drew up plans for new construction as well as for alterations to existing buildings. To speed matters the engineers, the Medical Department, and the British agreed on certain standard designs for new hospitals and for converting existing facilities, subject to changes on advice of the chief surgeon. He frequently made adjustments because of location, terrain, and special needs.36

Hospital floors gave the engineers trouble. Because concrete floors created considerable dust, they were covered with pitch mastic, but the black covering

showed dust and always looked dirty. A covering of oil and wax solved the problem in the wards but not in the psychiatric and operating wings, where static electricity could cause anesthetic gases to explode. Finally, a cement finish treated with sodium silicate was substituted for pitch mastic in operating rooms.37

All through 1943 and early 1944, hospital construction lagged considerably. Because arable land was at a premium, the British Ministry of Agriculture refused to approve many suggested sites, and locations became limited mostly to parks and estates of the “landed gentry.” Inadequate transportation to haul materials to the sites also slowed work. Since labor and materials came through different agencies, one or the other often was not available when needed. Labor shortages held up all construction, especially for the hospital program.38 The lag in hospital construction was not too serious, for the full capacity of hospitals would not be needed until casualties started coming back from the Continent. On 31 May 1944, just one week before the invasion, the hospital program was 94 percent complete.

The Manpower Shortage

Personnel became General Moore’s most abiding concern in 1943. As the year began, only 21,601 U.S. Army engineers were in the United Kingdom, with jtist 9,727 allotted to the Services of Supply. Many SOS engineer troops were still in the labor pool that manned depots supporting the North African invasion. General Moore explored all avenues to solve manpower problems. Some aid came from tactical units, including USAAF organizations, and, on the hospital program, from Medical Department personnel and even convalescent patients. Considerable reliance also had to be placed on British civilian labor.39

British Labor

Civilian labor was an important aspect of Reverse Lend-Lease. In December 1942 British and U.S. Army officials established procedures for employing British civilians. Pooling their limited civilian labor force, the British allocated civilians according to priorities the War Cabinet set, while contracts and contractual changes were made to fit existing priorities. For ground projects the order of priority was depots, camps, and hospitals.40

In April 1943 approximately half of the 120,000 British civilians assigned to the BOLERO program were working on American engineer projects-30,000 on air force and 28,000 on ground force projects. Complaining that the shortage of British labor was delaying completion of BOLERO, engineers at SOS, ETOUSA, constantly demanded more civilian help. The British government did what it could, but the supply was limited; indeed, the British had to cut the civilian work force in the spring and summer of 1943 to meet domestic demands for agriculture and industry.

By 1 September 1943, more American engineers than British civilians were working on U.S. Army projects, and the differential grew larger as more American engineer troops arrived in the United Kingdom.41

The British civilian labor force was the product of a nation already drained by three years of war. Consisting of older men and boys below draft age, the work crews were neither well trained nor effective without close supervision. They worked an average of seven hours a day, less than troop labor. British habit dictated a 28-day work month, with alternate Sundays off; frequent holidays cut into the work schedules. British workers also had many absences due to colds and influenza.

British insistence on semi-permanent rather than temporary structures slowed the construction program. The Ministry of Works continued to justify more sturdy buildings since they were to be used after the war. There was an eight-month difference in the time needed to complete contracted airfield construction jobs. U.S. Army engineers took 13½ months to construct a heavy bomber base while British civilian contractors needed two years to finish the same type of project with their limited work force and lighter equipment.42 On the other hand, not all American engineer units coming into England lived up to expectations.

Field Force Units on Construction Jobs

Engineer combat battalions were available for construction work from late July until 11 December 1943, when they were to be released for invasion training. By the end of July the number of field force engineers on construction tasks had risen to 11,233—more than twice the number available in June.43

Although SOS, ETOUSA, which for months had been calling for the highest shipping priority for its units, had succeeded in obtaining a very high priority for engineer construction units in November 1943, the buildup of SOS engineer units was slow, complicated by uncertainty over the ultimate size of the invasion forces and changes in the troop basis. The shipment of service units began to improve in September 1943, but not enough to meet the deadline for the release of field force engineers. In October engineer combat battalions were extended on construction jobs until 31 January 1944. Combat group headquarters as well as light equipment, maintenance, and dump truck companies were also pressed into service. At the end of the year the deadline date was extended again; some units were assigned to construction indefinitely. In the spring of 1944 several engineer camouflage battalions were added to the construction force.44

In December 1943 five of eight nondivisional engineer combat battalions, one combat regiment, and one light equipment company—all from the field forces—were still attached to SOS for construction. Two months later nine combat battalions, a maintenance company, and a light equipment company were still assigned to construction tasks. In late March the numbers dropped sharply. Only a few field force engineers remained on construction jobs, and most ground force engineer units turned to training for the invasion.45

U.S. Army engineers on construction jobs numbered 40,436 on 1 September 1943; 49,000 at the end of October (28,000 on ground projects, 21,000 on air force projects); 55,027 at the end of the following month; and 56,000 at the close of the year. Peak strength came in March 1944 with 61,000 engineers working on construction projects (35,500 men on ground and 25,500 on air force jobs). At the end of May, a week before the invasion, 13,794 engineers were still engaged in construction.46

The effectiveness of field force, SOS, and aviation engineers on construction jobs decreased—and motor maintenance increased—because units were split to work on widely scattered jobs. The 1323rd Engineer General Service Regiment at one time was scattered over an area 200 miles long and 80 miles wide. Elements of the 346th Engineer General Service Regiment were separated for nineteen months, assembling as a complete unit only in April 1944. The 342nd Engineer General Service Regiment had no unit larger than a battalion in the same area between 12 July 1942 and 31 December 1943.47

The quality of engineer units working at construction jobs ranged from very good to marginally effective. The absence of planning by officers and noncoms caused inefficiency. Some engineer units on construction jobs lacked specialists in steel, brick, and electrical work, and men had to be trained in these skills. Many officers lacked either administrative ability or technical knowledge.48

The shortage of officers with construction and engineering experience persisted throughout the war in almost every type of unit. In the summer of 1943 a civilian consultant from the United States found a greater need for training among officers than enlisted men. “Civilian experience of the officers,” he remarked, “in many cases does not exist.”49 General Moore felt that, considering the large number of people who had engineering education, “a very poor job was done” in getting the proper personnel into the engineers.50

Engineers at the Depots

In January 1943 ETOUSA had only one engineer depot company split among three depots to process engineer supplies for units in the United Kingdom and for TORCH organizations.

Three companies of an engineer aviation battalion, the 347th Engineer General Service Regiment, and several separate engineer battalions provided temporary help at the depots.51 As the number and size of depots grew, decentralization became necessary. In February 1943 operational control of the depots passed from the Supply Division, OCE, ETOUSA, to the base sections.

Depot operations improved markedly as the base sections assumed more control over supply. By August 1943 the base sections were exercising internal management of all previously exempted depot activities and were free of the limitations of Class II and IV supply levels imposed on their counterparts in the United States. The new authority made the engineer representatives in the United Kingdom base sections responsible to their base section commanders rather than to General Moore, though he still retained limited technical supervision.52

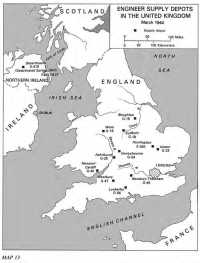

The engineers stocked their supplies in three types of depots. (Map 13) Reserve depots stocked an assortment of items, in large enough quantities for overseas use, that were issued to units in the United Kingdom only when the British could not provide them. Key depots stored and issued selected items for specific purposes. Distribution depots stored and issued all types of supplies and equipment. By 1944 twelve engineer depots, both solely engineer and engineer subdepots at general depots, had been set up—one in Northern Ireland Base Section, three in Eastern Base Section, and four each in Southern Base Section and Western Base Section. By 31 March 1944, these twelve had provided a total of 17,143,914 square feet of storage space, of which 1,161,452 was covered storage space, 15,909,694 square feet was open, and 72,768 square feet was shop space.53

The number and type of units performing engineer supply operations varied from depot to depot. The largest engineer section was at Newbury in Southern Base Section. With little covered storage, the section handled mainly heavy and bulky stores. The engineer section at Ashchurch handled a. variety of heavy and bulky supplies, small parts, tools, and spare parts. Another depot held Class IV supply, most of it reserved for Continental operations, in open storage. This practice involved considerable risk, especially in winter, since iron and steel items with machined or unpainted surfaces left in the open rusted.54

The troops at engineer depots fell into two categories, engineer depot operating units—companies and group headquarters—and quartermaster labor, referred to as “touch labor.” In July 1943, with only two depot companies and two base depot companies on hand,

Map 13: Engineer supply depots in the United Kingdom

the shortage of depot personnel was critical. By mid-September the U.S. engineers were running seven depots (soon to be eight) with five depot and base depot companies. Three of these units had been in the theater less than eighty days and were of limited value—a depot company needed ninety days of experience in the United Kingdom before it could be expected to carry its full share of work. Neither officers nor enlisted men had had much practical experience before going overseas because civilians ran U.S. depots. For many of the engineers, training in the United States consisted of only six weeks in the field or on maneuvers, during which time the depot units had only one or two transactions to handle. Approximately 30 percent of the engineer supplies handled in the United Kingdom were of British manufacture, and their nomenclature could be learned only in the United Kingdom.55

Since only a small portion of engineer supplies could be manhandled, a large number of crane operators and riggers was needed. Men with such skills were not often available in the small quartermaster labor force or in the engineer depot companies. The 445th Engineer Base Depot Company, as an example, arrived in August 1943 and immediately began operating the engineer section of a major depot at Sudbury. The men often spent eighteen to twenty hours at a stretch trying to learn their tasks. The unit was constantly short of labor and equipment, especially of material-handling equipment, which had to be overworked and ultimately broke down completely.56

The engineers employed various expedients to overcome the personnel shortage. The few well-trained depot companies (such as the 397th) were split, usually three ways, and dispersed so that all engineer depots would have at least some trained personnel. Depots used men from dump truck, heavy equipment, and general service organizations, a last-ditch expedient since identification of various items of engineer equipment and supplies was a difficult job requiring alertness and training.

The number of engineers at depots increased slowly to 5,400 at the end of January 1944, 6,200 by the end of February, 6,500 the next month, and 7,500 by the end of April. Then nondivisional engineer field units had to be called in to help.57 The shortage of depot personnel, especially crane operators, riggers, and trained clerical help, hindered engineer depot work all through 1943 and well into 1944. Trained crane operators were as scarce as cranes, and the fumbling efforts of untrained operators added to spare part and repair problems.58

Equipment Maintenance

Engineers in the United Kingdom

sorely needed more third echelon maintenance companies equipped with mobile shop trailers to make field repairs and replace major unit assemblies at construction sites, depots, or wherever the engineers needed more extensive equipment maintenance than they could accomplish with their own second echelon tools and parts. In his first monthly report to the United States in April 1943 General Moore emphasized this shortage. In May 10 percent of all engineer equipment was deadlined for third echelon maintenance repairs with an additional 5 percent deadlined for fourth echelon repairs. Fourth and fifth echelon maintenance repair was the responsibility of heavy shop companies which provided base shop facilities and, when necessary, manufactured equipment either at mobile heavy duty shops or at large, centrally located fixed shops. Mobile shops provided emergency and general-purpose repair and welding service.59

The absence of heavy shop companies at some base sections placed an additional burden on third echelon companies, and their efforts to undertake major repairs for which they were not equipped often resulted in delay or unsatisfactory work. To improve matters General Moore assigned special maintenance officers to each base section to coordinate the work of the maintenance and heavy shop companies and the spare parts depots. But the shortage of maintenance companies persisted, and at the end of November 1943 there were only seven such units in the European Theater of Operations. At that time the Supply Division, OCE, WD, felt that maintenance in the United Kingdom was not more than 75 percent adequate.60

When preventive maintenance such as lubrication and cleaning by equipment operators was inadequate, the maintenance companies’ work load increased. Often the equipment operator received neither proper tools nor supervision, nor were sufficient periodic inspections made. Careless handling of equipment by inexperienced operators added to the problem. Frequently, equipment was turned into the engineer maintenance companies for third and higher echelon repair in a “partially dismantled condition,” short many parts.61

Spare Parts

Obtaining first echelon spare parts such as spark plugs, fan belts, bolts, nuts, cotter pins, and lock washers and second echelon carburetors, fuel oil and water pumps, distributors, gaskets, and various clutch, brake, and chassis parts was a constant problem, partly because of poor procurement procedures—too few short-lived parts and too many long-lived ones. The engineers’ problem was aggravated by the large number of nonstandard pieces of equipment –

British-made or U.S. items made to British specifications—for which parts were often unavailable.62

The first engineer spare parts depot began operating at Ashchurch in the spring of 1943. In June the first of the specialized spare parts companies to arrive in the theater, the 752nd Engineer Parts Supply Company, took over the depot. Several similar companies arrived from the United States during the summer and fall, enabling the theater engineer to set up spare parts sub-depots at Conington, Sudbury, and Histon and to establish an effective daily courier system between the subdepots and the general depot at Ashchurch.63

The spare parts companies did excellent work, constructing most of their own bins and, despite the handicap imposed by a lack of training and proper equipment, reducing substantially the large backlog. In conjunction with the engineer heavy shop companies, the parts supply units salvaged or reclaimed many parts that might otherwise have been lost. In early 1944, as the days grew longer, the companies worked two and even three shifts. Despite these efforts the shortage of spare parts, particularly such vital items as cranes, continued to be a serious concern to engineer planners as preparations accelerated for the invasion of Europe.64

The Continent assumed an ever-larger share of the attention of the Allied and theater planning staffs in England in the latter part of 1943. Across the Channel lay a host of engineering problems associated with the projected invasion of German-occupied territory and the maintenance of armies there for the final phases of the war.