Chapter 19: Breaching Germany’s Barriers

Rolling into Eupen behind tanks on the afternoon of 11 September 1944, the engineers saw that “the ‘fun’ the boys had had in liberating all those towns and cities in France and Belgium was over.”1 They were greeted not with wild cheers but with hostile stares. Eupen was in Belgium, but it was only some five miles from the German border. All the signs were in German. From some windows hung Belgian flags, but from others were suspended white bed-sheets signifying surrender. The engineers belonged to Company B of the 23rd Armored Engineer Battalion and were supporting Combat Command B of VII Corps’ 3rd Armored Division, the spearhead tankers who, on 12 September, would be the first Americans to capture a German town.

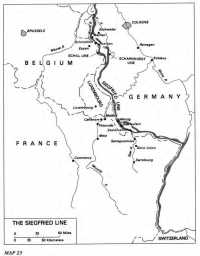

General Eisenhower had long planned that as soon as enemy forces in France were destroyed the American armies would advance rapidly to the Rhine, First Army through the Aachen Gap on the north to Cologne and Third Army through the Metz Gap south of Koblenz.2 On the northern battlefront in France artificial and natural barriers blocked the routes to the Rhine. The attackers would have to clear a path through the concrete fortifications that formed the Siegfried Line. They would also have to penetrate dense woods and forests, overcome fortifications protecting Aachen and Metz, and cross many rivers, some of them in flood. In the two months between the first breaching of the Siegfried Line and the start of the German counteroffensive in mid-December the deepest advance into Germany was only twenty-two miles.3

The Siegfried Line

Begun in 1938, the Siegfried Line was a system of mutually supporting pillboxes, about ten per mile, extending along the German border from a point above Aachen south and southeast to the Rhine and thence along the German bank of the Rhine to the Swiss border. North of Aachen the line consisted of a single belt of fortifications, while south of that city it split into two belts, about five miles apart, known as the Scharnhorst Line and the Schill Line. Farther southeast, in the rugged terrain of the Eifel, the line was again one belt until it reached the region of

the Saar, where it split once more. (Map 23)

The pillboxes were set at least halfway into the earth. Walls and roofs were of reinforced concrete three to eight feet thick, sometimes covered with earth, grass, and trees and sometimes disguised as farmhouses or barns. Concealed steel doors led to rooms for quartering troops and storing arms and ammunition. The firing ports could usually accommodate only light machine guns and the 37-mm. antitank guns standard in 1938. Most heavier fire had to come from mobile artillery and tanks stationed near the fixed fortifications.

For protection against tanks the pillboxes often depended on natural barriers such as watercourses, forests, and defiles. In more open country the pillboxes had a shield of 45-foot-wide bands of “dragon’s teeth”—small concrete pyramids, usually painted green to blend in with the fields. The pyramids had been cast in one piece on a concrete base, with steel reinforcing rods tied into the base’s reinforcing rods. The teeth in the first two rows were about 2½ feet high, those in the following rows successively higher until the last stood almost 5 feet tall. Between the rows were iron pickets imbedded in the bases, designed to take barbed wire. Wherever a road ran through the bank, the Germans blocked access with obstacles such as steel gates.4

In late August 1944 Hitler rushed in a “people’s” labor force to strengthen the line. This effort bore fruit in the Saar, where the Third Army did not arrive at the Siegfried Line until early

December; but in the First Army’s Aachen and Eifel sectors, where VII Corps and V Corps reached the line almost simultaneously on 12 and 13 September, the Germans did not have time to accomplish much.5 They had begun to dig antitank ditches in front of the dragon’s teeth but had to abandon them, leaving picks and shovels behind; nor had they had time to string barbed wire on the iron pickets. In general, second-rate troops manned the pillboxes and other defensive works.

VII Corps South of Aachen

By nightfall on 11 September two task forces of CCB—Task Force 1 commanded by Lt. Col. Wiliam B. Lovelady and Task Force 2 commanded by Lt. Col. Roswell H. King—and 3rd Armored Division had passed through Eupen and encamped for the night east and northeast of the town. At 0800 next morning a reconnaissance force of infantry, tanks, and engineers of Task Force Lovelady began to move toward the German border, but the tanks bogged down on a forest trail. A second group set out along the main highway shortly before noon. Capturing some German machine gunners who surrendered without firing, the reconnaissance elements crossed the border shortly before 1500; the main body of Task Force Lovelady joined them about an hour later. The task force passed through the German town of Roetgen without opposition.

Beyond Roetgen, on a highway leading north, Task Force Lovelady ran into

Map 23: The Siegfried Line

Men of the 23rd Armored Engineer Battalion rig charges to demolish dragon’s teeth in the Siegfried Line

the first defenses of the Siegfried Line. Ahead was a crater the Germans had created by blowing a bridge over a dry stream bed, and behind the crater was a gate made of steel pipes. Left of the gate lay a band of dragon’s teeth, extending for about a hundred yards and ending at a hill on which stood a pillbox. On the right rose a steep, almost perpendicular hill. Embedded in slots in this hill, just behind the gate, were steel I-beams that protruded across the road. This hill also boasted a pillbox.

Heavy fire from the two pillboxes stopped the advance about 1800. Darkness was falling, and the task force, whose vehicles stretched back beyond Roetgen, camped for the night. Dur ing the night the infantry began working its way behind the pillboxes, and after a fire fight early on 13 September both pillboxes surrendered. Then the engineers went to work. They filled in the road crater using a tankdozer, blew the gate with ten pounds of TNT, and removed the I-beams from the hill by hand. The attack columns began moving forward. After about three hundred yards they ran into another steel gate, which the engineers blew out about 1000. Task Force Lovelady was through the Scharnhorst Line.6

During the afternoon of 12 September Task Force King bypassed Roetgen and headed toward the village of Schmidthof, about four miles to the north. King’s unit encountered the same types of obstacles as Task Force Lovelady had faced. A crater, steel gates and I-beams, and dominating pillboxes in hilly, wooded terrain barred Task Force King’s way. On the morning of 13 September tanks nosed out the first steel gate. A second gate was more formidable. In front of it lay a huge water-filled crater; behind it were I-beams embedded in concrete blocks. Moreover, the roadblock was under fire from 88-mm. artillery and the guns of tanks at Schmidthof. The shelling delayed the attack for hours. Unable to work on the roadblock under such fire, the engineers constructed bypasses wide enough to accommodate tanks. Tanks and artillery ultimately knocked out the guns at Schmidthof, and by the afternoon of 14 September Combat Command B’s Task Force King had penetrated the line.7

Combat Command A of the 3rd Armored Division, advancing on the north nearer Aachen where the countryside was open and rolling, ran into a belt of dragon’s teeth extending from the edge of a forest on the Belgian border to the German town of Oberforstbach, a distance of about a thousand yards. Task Force X, commanded by Col. Leander LaC. Doan, began the advance about 1000 on 13 September. Doan sent infantry through the dragon’s teeth; engineers of Company C, 23rd Armored Engineer Battalion, followed with trip wires and demolition materials. Initially holding at the line of departure, the tanks were to move out as soon as the engineers had cleared a path for them. But the infantry and engineers ran into fire from a pillbox as well as heavy machine-gun and mortar fire from open emplacements that forced the forward troops to take shelter behind the dragon’s teeth. Some way had to be found to get the tanks forward. At midafternoon reconnaissance discovered a passageway over the dragon’s teeth—apparently, local farmers had filled in the spaces between the teeth with stones and earth. About a foot of each tooth was exposed, but engineers cut off these obstacles with explosives, and the tanks went through, neutralizing pillboxes at point-blank range.8

Having broken through the Scharnhorst Line, the 3rd Armored Division pressed north toward Eschweiler, northeast of Aachen, and by 15 September came up against the dragon’s teeth and pillboxes of the Schill Line. In this more thickly settled area pillboxes were often disguised as houses, ice plants, or power stations.

By the time VII Corps reached the Schill Line, the corps’ units had learned that the best way to take out the pillboxes was to bring up tanks, tank destroyers, and self-propelled 155-mm. guns for point-blank fire. Even with a concrete-piercing fuse, high-explosive (HE) projectiles could seldom penetrate the thick walls; however, penetration was usually not necessary. The occupants of the pillboxes, suffering from concussion

Bulldozer seals bunkers in the fortified line outside Aachen

shock and choking on powdered concrete, would in most cases readily surrender.

Then the engineers’ task began. In the VII Corps sector and farther south in the Schnee Eifel, where the V Corps had broken through the Siegfried Line in several places by mid-September, the Americans had learned that if a pillbox was not rendered unusable enemy patrols were likely to infiltrate the lines at night and reoccupy it. Although the simplest method was to blow up pillboxes, in many cases it was expensive—destruction of the larger pillboxes in VII Corps area required up to 1,000 pounds of TNT. In forward areas the noise and smoke of the explosions also attracted enemy fire. The VII Corps engineers preferred to seal the pillboxes. Using a bulldozer, they would cover all openings with eight to ten feet of earth. In places where a bulldozer could not be employed, the engineers welded steel doors and embrasures shut. Between 11 September and 16 October in the VII Corps area only 36 pillboxes were completely destroyed with explosives as compared to 239 covered with earth and 12 closed by welding.

Most of this work was completed before the end of September. By October First Army had outrun supply lines, gas and ammunition were running low, the troops were exhausted, and their equipment was depleted. Bad weather prevented close air support. In addition,

German tanks and antitank guns, well positioned along the second band of the Siegfried Line, were inflicting heavy losses on American armor. At the end of September the advances of V and VII Corps halted, and both corps went on the defensive.

XIX Corps North of Aachen

North of Aachen the Wurm River protected Siegfried Line pillboxes. The river rendered dragon’s teeth superfluous except at a few points, and XIX Corps encountered none when attacking across a mile-wide front about nine miles north of Aachen. There the Wurm was about thirty feet wide and only three feet deep. The infantry could cross the stream easily, using duckboard footbridges or even logs thrown into the stream. But the Wurm was a real obstacle to tanks, for its banks were steep and marshy.9

The 30th Infantry Division was to spearhead the attack, followed by the 2nd Armored Division. The infantry was in position on 19 September. The original plan was to push through the Siegfried Line next day and move south to relieve pressure on VII Corps near Aachen. But the weather did not permit an air strike deemed essential before the jump-off. To allow time for the bombing and for the arrival of supplies and reinforcements, the attack was postponed until 2 October.

During the fortnight’s delay, the 105th Engineer Combat Battalion, organic to the 30th Division, reconnoitered the Wurm River for the best crossing sites, and one of its companies constructed bridges for infantry and tanks. The tank bridges, which the engineers called culverts, were ingenious contraptions made of thirty-inch steel pipe, reinforced on the inside with smaller pipe and on the outside with a layer of six-inch logs bound with cable. The engineers constructed ten, to be divided equally between the two assault regiments. The method of emplacing the bridges, designed to protect the troops from small-arms fire, was also inventive. The culverts, laid lengthwise on improvised wood and steel sleds, were to be pulled to the crossing site by a tank moving parallel to the stream with a tankdozer following. At the site the tankdozer was to push the culverts into place and then cover them with dirt.

Two companies of the 105th Engineer Battalion were in direct support of the division’s two assault regiments, with an engineer platoon attached to each infantry assault battalion and a three-man engineer demolition team, armed with bangalore torpedoes and satchel charges, moving out with each infantry platoon. The engineers supervised training of the infantry in the use of flame throwers, demolition charges, bazookas, and other weapons to be used against pillboxes.

D-day for the XIX Corps’ attack on the Siegfried Line was 2 October. An air strike preceded the jump-off at 1100 but did little good. Nor did preparatory artillery and mortar barrages accomplish much beyond driving Germans holding outlying emplacements into pillboxes. Tank and tank-destroyer support was lacking, and wet weather proved too much for the culvert bridges. One of them became stuck in mud;

another could not be emplaced because its bulldozer became mired. The engineers abandoned the culverts and began constructing treadway bridges with the help of the 1104th Engineer Combat Group’s 247th Engineer Combat Battalion. This work went forward under heavy enemy artillery fire, and after a treadway was ready at one regimental crossing half the tanks, as well as their recovery vehicles, bogged down in mud. In the other regimental sector the tread-way was not in place until 1830—too late to permit a crossing.

Thus, the first day’s assault on the pillboxes became entirely an infantry and engineer undertaking. The infantry had considerable success firing small arms and bazooka shells into apertures. Little use was made of flame throwers, pole charges, or satchel charges. When the pillboxes were small, located on flat or gently sloping ground, and lightly defended, the engineers preferred to seal them, bringing up a jeep-towed arc welder to weld shut the entrances and then bulldozing earth over the embrasures. When observed enemy fire was present, or when terrain or the tactical situation prevented the use of dozers, the engineers destroyed the pillboxes, placing TNT on the weaker portion of the walls and firing the charge electrically. The engineers found that a 400-pound TNT charge could destroy the average pillbox at this point in the line. Learning that a single explosion in the forward areas would bring down an accurate German artillery concentration, the engineers blew several pillboxes simultaneously.

When tanks arrived at the fortifications they assisted the infantry and engineers with covering fire. By blasting pillbox apertures and entrances with armor-piercing ammunition, the tanks sometimes could induce the occupants to surrender, but tank fire was effective only in knocking camouflage from the thick concrete. This was also true of most artillery fire. The only weapon that could achieve any significant penetration was the self-propelled 155-mm. gun.

The Siege of Aachen

By 7 October XIX Corps had breached the West Wall in its sector and was ready to join VII Corps in attacking Aachen. As the two corps moved to encircle the city, engineers served as infantry on the flanks, and when the assault commenced on 8 October both engineer groups sent battalions to the front lines. The XIX Corps wanted to free one regiment of the 29th Division to help the 30th Division in a drive south on 13 October to close the Aachen Gap. Thus, three days before the attack the 1104th Engineer Combat Group entered the line to contain the pillboxes near Kerkrade, west of the Wurm River. Corps headquarters attached to the group a company of tank destroyers and two batteries of self-propelled automatic weapons, actually half-tracks mounting .50-caliber machine guns. Lt. Col. Hugh W. Colton, commanding the group, combed his light ponton, light equipment, and treadway bridge companies to form an infantry reserve for the operation.10

Stiffening German resistance slowed the XIX Corps’ advance south down both banks of the Wurm River. Not

until late in the afternoon of 16 October was the corps able to link up with VII Corps elements north of Aachen. During the advance the 1104th Engineer Group patrolled its flanks and dispatched aggressive reconnaissance patrols in front of its position. On 17 October, after an artillery and mortar concentration, Colonel Colton sent the 172nd and 247th Engineer Combat Battalions forward toward Aachen. Destroying pillboxes that blocked the way, the engineers, reinforced by a platoon of tanks, fought their way to the outskirts of the city but stopped as the town fell.11

Under VII Corps the 1106th Engineer Group during the last week of September moved to relieve the 18th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division, in positions on the heights south of Aachen so that the infantry could move north to link with XIX Corps. The group commander, Col. Thomas DeF. Rogers, began training his two combat battalions, the 237th and the 238th, in the use of 81-mm. mortars and organized a reserve of 150 men drawn from his light ponton and treadway bridge companies. As soon as the attachment to the 18th Infantry became effective on 29 September, Colonel Rogers sent his two combat battalions to occupy positions with the infantry battalions; the action proved so valuable in familiarizing the engineers with the operation that he strongly recommended an overlap period during any similar mission in the future.12

After the infantry began withdrawing on 2 October, the 1106th Engineer Group “became a real ‘doughboy’ outfit standing on its own feet in a front line fight.” Supported by an armed field artillery battalion, the engineers laid booby traps and antipersonnel mines along the barbed wire protecting their front and sent out combat patrols to maintain contact with the enemy. Colonel Rogers learned that his group’s tactical operations would act as a diversion for the 18th Infantry’s assault on the city from the north.

The group’s 238th Engineer Combat Battalion made an ingenious contribution to this mission on 8 October. Discovering several streetcars standing on tracks leading down a grade into Aachen, they loaded one of the cars with captured German shells and ammunition, a case of American explosives, and several time fuses. On its side they painted “V-13,” inspired by a

German V-bomb that had recently passed over the area. Then they sent their missile careening downhill toward Aachen. About 200 yards beyond a battalion outpost the car struck some debris on the track and exploded with a fine display of tracer shells. Next day the engineers tried again, loading a second streetcar with enemy shells and sending it down the track, but it hit the wreckage of the first and exploded. Clearing the wreckage from the track, the engineers sent a third car downhill on 16 October. It reached the city, but it could not be determined whether it did any damage. In any case, “Secret Weapon V-13” attracted swarms of newspaper correspondents. Colonel Rogers concluded that the greatest value of the V-13 was “in giving GI Joe

something amusing and bizarre to talk about.”13

An all-out attack on Aachen began 11 October after the Germans refused to surrender. By that time, the 26th Infantry of the 1st Division was in position to attack from the east, its left wing tied in with the position of the 1106th Engineer Combat Group. The infantry began moving into the city in small assault teams that attacked block by block, building by building, even room by room; the engineers also sent patrols into the city.

Two men of the 238th Engineer Combat Battalion patrol, S/Sgt. Ewart M. Padgett and Pfc. James B. Haswell, were to play an important role in the surrender of Aachen. The Germans captured the two on 17 October in a clearing outside the city. After passing through several command posts the two Americans arrived on the third day at the garrison command post, a pillbox where the Germans held about thirty American prisoners. There, on the morning of 21 October, the German intelligence officer informed the American prisoners that the fort had tried to surrender but that two Germans carrying a white flag outside had been killed. He asked for a volunteer among the Americans to carry the flag. Haswell volunteered and Padgett insisted on going along.

Padgett took the flag, and the two men, followed by two German officers, ran out into the middle of the street and began waving it. Braving small-arms and mortar fire, they managed to reach an American officer who told them to bring out the entire German garrison. The two led out the Germans, including the commander of Aachen, Col. Gerhard Wilck. Before leaving the pillbox, the engineers asked Wilck for his pistol. He laid it on a table, smiled, and left the room. Thus they secured a prize souvenir of the occasion. Later, after surrender formalities were completed, Wilck shook hands with the two engineers, saluted, and thanked them for their “gallant bravery” in carrying out the surrender flag.14

From the Moselle to the Saar

On 22 September General Bradley had stopped the Third Army advance to give priority to First Army’s drive to the Ruhr in support of the 21 Army Group effort to capture Antwerp. At that time General Patton had been preparing to push through the Metz Gap to the Rhine. When Aachen fell on 21 October, Bradley lifted the restrictions on Third Army.

In the army’s path lay some of the most formidable fortifications in Europe. West of Metz lay a chain of old forts, some dating from 1870, situated on ridge-tops that gave every advantage to defenders. Next was the Moselle River, on whose east bank most of the city of Metz was located. The river had a swift current and steep gradients and was subject to autumnal flooding. Beyond the Moselle on the Lorraine plain, a region extending thirty miles to the Saar River, was the Maginot Line. At the Saar around Saarbrücken the main Lorraine gateway opened to the Rhine. There, on the east side of the Saar, was

the strongest portion of the Siegfried Line.15

The plan was for XII Corps, in the area of Nancy thirty miles south of Metz, to start pushing north on 8 November. The XX Corps would follow the next day, advancing eastward north and south of Metz. About ten miles to the south, XX Corps’ 5th Infantry Division already had a bridgehead over the Moselle at Arnaville. While that division turned north for a close envelopment of Metz, the 90th Infantry and 10th Armored Divisions were to make a wider encirclement, bypassing the forts around Metz by crossing the Moselle six miles northeast of the village of Thionville, about twenty miles north of Metz. At the same time, the 95th Infantry Division was to make a limited-objective crossing as a feint at a point about three miles south of Thionville.

The Moselle Crossings at Mailing and Cattenom

The bulk of the effort to get Third Army troops over the Moselle during the November attack fell to the engineers supporting the 90th Division. In rubber assault boats of the 1139th Engineer Combat Group, troops of the 359th Infantry were to cross near the village of Mailing on the left (north) flank, supported by the 206th Engineer Combat Battalion. On the right, battalions of the 358th Infantry were to cross simultaneously near Cattenom, with the 179th Engineer Combat Battalion in support. At both crossings, where the water gaps were estimated to be 360 and 300 feet wide, respectively, the engineers also were to construct an infantry support bridge, a treadway bridge, and a floating Bailey bridge, while the 90th Division’s organic 315th Engineer Combat Battalion was to build a footbridge, operate ferries, and undertake far-shore work. As soon as the expanding bridgehead had cleared the far shore of Germans, the 160th Engineer Combat Battalion was to construct a double-triple fixed Bailey bridge at Rettel, northeast of Malling.16

By the night of 8 November the engineers had trained with the infantry in preparation for the crossing, demonstrating the proper way to carry and load an assault boat. For each boat the crew consisted of three engineers, one a guide. That night the river began to rise, and by the time the boats of the attack wave shoved off in drizzling rain at 0330 on 9 November, the infantry had to load in waist-deep water. In spite of a strong current the two leading infantry battalions were on the east bank of the Moselle by 0500. As they reached their destination the troops found that the high water had actually helped the crossings: extensive minefields the Germans had prepared on the far shore were flooded, and the boats passed over without danger. Also, the enemy had abandoned water-filled foxholes and rifle pits dug into the east bank.17

After daybreak, as succeeding infantry battalions crossed the racing yellow Moselle, enemy artillery fire fell so heavily on the east bank that many

crews abandoned their boats after debarking the troops, allowing the craft to swirl downstream to be lost. But the infantrymen made swift progress. At Malling, where they achieved complete surprise, troops of the 359th Infantry captured the town by noon. The 358th Infantry, after crossing from Cattenom, faced a more formidable objective—Fort Koenigsmacker, which had to be reduced before further progress could be made. There too the 90th Division achieved surprise. Assault teams of infantry and engineers (from the 315th Engineer Combat Battalion) ripped through bands of barbed wire and reached the trenches around the fort before an alarm was sounded. Braving mortar and machine-gun fire from the fort’s superstructure, the teams reduced the fort, blowing steel doors open with satchel charges and blasting ventilating ports with thermite grenades or TNT.

By the end of November the 90th Division had eight battalions, including reserves from the 357th Infantry, across the Moselle. The division had advanced two miles beyond the river, overrun seven towns, and penetrated Fort Königsmacker.18 Next day, as German resistance stiffened, little progress was made, but by midnight, 11 November, the 90th Division’s leading units held a defensible position on a ridge topped with the Maginot Line fortifications. The division had knocked out or bypassed many of the line’s weakly held pillboxes and had forced the surrender of Fort Koenigsmacker with hand-carried weapons and explosives, a few 57-mm. antitank guns ferried across the Moselle, and artillery fire from the west bank. No tanks or trucks had yet been able to cross the river, and supply parties had to use rickety farm wagons and even abandoned baby buggies.

Attempts to bridge the flooding river, beginning early on 9 November, came to naught for two days. Before Fort Königsmacker surrendered, shellfire from the bastion had made the bridge site at Cattenom untenable and destroyed the bridging equipment. At Mailing, harassing enemy machine-gun and mortar fire forced the 206th Engineer Combat Battalion to abandon its first attempt to build a footbridge. At 0600 on 9 November the engineers began constructing another and simultaneously put two ferries into operation. One, using boats lashed together and powered by outboard motors, carried ammunition and rations and evacuated the wounded around the clock. The other, using infantry support rafts to carry 57-mm. antitank guns, jeeps, and weapons carriers, was short-lived. A few antitank guns got across, but at 1100 a raft carrying a jeep ran into the infantry footbridge, broke its cable, and put the bridge out of action. The infantry support bridge, then about three-quarters finished, was carried downstream and lost.

Recovering some of the equipment, the engineers decided to build a tread-way bridge at the site, and the 991st Engineer Treadway Bridge Company managed to complete the new span by dusk on 10 November. But the river’s continued rise had now put the road leading to the bridge under nearly five feet of water. No vehicles could get through until the following afternoon when the floodwaters, having crested at noon on 11 November, began to recede. At 1500 the crossings began

Troops float footbridge sections into place on the flooded Moselle River in the 90th Division area

again. Ten supply-laden Brockway trucks, some jeeps, and a few light tanks and tank destroyers reached the far shore. Shortly after dawn next morning German artillery fire repeatedly hit the treadway, so weakening it that it could no longer bear the weight of a tank destroyer. It broke loose and went off downstream.

While waiting for more equipment to come up so they could rebuild the bridge, the men of the 991st Engineer Treadway Bridge Company used bridge fragments to construct a tank ferry. Employing a heavy raft made of pontons and treads and tying powerboats to the raft, the engineers manned the ferry, crossing a company each of medium tanks and tank destroyers by dark. This work earned the 991st Engineer Treadway Bridge Company the Distinguished Unit Citation.19

Late on 12 November, the engineers were repairing the Mailing bridge and building a bridge at the Cattenom site. But by now the XX Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Walton H. Walker, had decided on another site for heavy bridging to move his armored division across the Moselle.

The Bridge at Thionville

The place was Thionville, where high

retaining walls constricted the flood waters of the Moselle and where the Germans had built a timber bridge, long since down. On the near side two spans of the German bridge were usable, while on the far side part of an old stone-arch bridge, which the French had blown in 1940, was still standing. Third Army held the part of Thionville west of the river, but the Germans were on the other side; there, a canal paralleling the riverbank formed a secondary obstacle. Beyond the canal lay Fort Yutz, an old star-shaped stone fortification. On the west bank the 1306th Engineer General Service Regiment, which had been acting as an engineer combat group because no group headquarters was available, was preparing on 9 November to build a Bailey bridge as soon as the east bank was clear of enemy. Meanwhile, they could do nothing, for any movement near the river drew rifle and machine-gun fire from Germans on the far bank. In his pressing need to get his armor across the Moselle, General Walker gave the commanding officer of the 1306th Engineers, Col. William C. Hall, a hard assignment, changing “the routine job of constructing a support bridge into a weird operation of major importance to the advance of an entire corps.”20

The first tactical task, to clear the east bank, General Walker gave to the 95th Division, which on 8 and 9 November had established a very small bridgehead across the Moselle at Uckange, a few miles south of Thionville. The commander of the 95th Division sent to Thionville two companies of the 378th

Infantry, supported by two companies of the 135th Engineer Combat Battalion. On the morning of 11 November the troops began to cross the Moselle at Thionville in powerboats. Enemy small-arms and mortar fire poured down on them. The engineer captain in charge of the boats was killed, as were a number of the crewmen, and all but one of the boats were lost. Nevertheless, by the morning of 12 November two platoons had crossed and cleared the south end of the island and had begun pushing north.

At 1030 that morning General Walker ordered the construction of the bridge, emphasizing that the success of the whole Third Army attack depended upon it. The 1306th General Service Regiment had already begun planning and from aerial photographs had determined that the gap to be bridged was about 165 feet long. The regiment decided upon a double-triple Bailey bridge, which could carry tanks. The 1306th had never built such a bridge, but one of its companies, Company C of the 1st Battalion, which had built a 100-foot double-single Bailey, took on the job. On the night of 10-11 November the regiment brought materials and equipment up to the bridge site and unloaded under blackout.

When the word came on 12 November to build the bridge, the engineers went into action. A party crossed the river in a powerboat, cleared the far span of mines, and prepared the far shore abutment. Then they discovered “a shocking fact”—the span to be bridged was 206 feet long instead of 165. The longest double-triple Bailey was 180 feet, and any lighter structure could not carry tanks. Engineers solved the problem by extending the near abutment

Heavy ponton bridge at Uckange, Moselle river

about ten feet, moving the far bridge seat almost to the edge of the stone arch, and building a double-triple Bailey 190 feet long. It was a calculated risk that had to be taken.

Cranes began lifting the panels into place, and the launching nose moved out over the water. Then, at 1700, the bridge came under concentrated mortar fire. A direct hit killed one engineer and wounded six; within two minutes the Germans inflicted more than twenty casualties, and the entire company had to take cover. After dark work resumed, continuing all night with a second company relieving Company C. At dawn on 13 November a smoke generating company gave the men the protection of a smoke screen. Mortar fire soon ceased as the infantry cleared the strip between the riverbank and the canal and advanced into Fort Yutz. Although 150-mm. guns began firing, the bridge escaped a direct hit, and no casualties occurred among the engineers climbing the superstructure clad in flak suits. Late that afternoon the engineers seated the far end of the bridge without difficulty.

About that time the near end ran into trouble, for one of six jacks failed to function. The bridge swayed and fell into the cribbing, and jacking up the near end took all night. A fresh company of engineers came up to the site. Despite heavy 150-mm. shelling which hit one man and ignited the remains of the German timber bridge, creating a glare

that drew further artillery fire, they completed the bridge at 0930 on 14 November. The engineers believed it to be the longest single-span bridge ever launched as a unit.

On the afternoon of 14 November the tanks of Combat Command B, 10th Armored Division, began to roll over the Bailey bridge at Thionville, and by daylight next day all had crossed. Combat Command A used the treadway bridge at Mailing and by dark on 15 November had two companies across. General Patton, who visited both sites, inspecting the Bailey bridge while it was still under enemy fire and crossing the treadway under a protecting smoke screen, later pronounced the 90th Division passage of the Moselle “an epic river crossing done under terrific difficulties.”21

Advance to the Saar

After envelopment to the north and south, coupled with a containing action west of the Moselle, Metz fell to XX Corps on 22 November. The lesser German forts in the area were left to “wither on the vine” (the last surrendering on 13 December) because scarce U.S. artillery ammunition had to be conserved to support the corps’ advance to the Saar River.

The XX Corps was to make the main thrust, heading toward a crossing at Saarlautern, about thirty miles northeast of Metz at the strongest section of the Siegfried Line.22 The XII Corps, coming up from the south, was to drive with the bulk of its forces to Sarreguemines, about forty miles due east of Metz, where the Saar swung south out of the Siegfried Line and into the Maginot Line. One of the corps’ two armored divisions, the 4th, was to cross south of Sarreguemines near Sarre-Union. The XX Corps’ 95th Division was to cross the Saar at Saarlautern, followed by the 90th. Flank protection on the north would be provided by Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division, which was to move toward Merzig, about ten miles north of Saarlautern. Ten miles north of Merzig, Combat Command A of the 10th Armored Division was to seize a bridgehead over the Saar at Sarrebourg, an important move because it pointed toward the ultimate axis of the Third Army effort—a Rhine crossing between Worms and Mainz. The 1139th Engineer Combat Group was to support the 10th Armored and 90th Infantry Divisions; the 95th Division was to have the support of the 1103rd Engineer Combat Group.

In the path of XX Corps the Germans had demolished almost all the bridges over streams and culverts. Abutments, however, were seldom destroyed, making the use of fixed Bailey bridges or short fixed treadway sections both feasible and relatively easy.23 Mud, rain, fog, and mines slowed the infantry more than did the Maginot Line, which was not very formidable. Crossing it, General Patton was “impressed by its lack of impressiveness.”24 Only in the path of the armor moving north

did effective field fortifications block the way.

On the night of 21 November Combat Command A of the 10th Armored Division came up against a strong line of fieldworks—a bank of antitank ditches, dragon’s teeth, concrete pillboxes, and bunkers. American intelligence had provided little or no information about this formidable barrier. It was the Orscholz Switch Line (known to the Americans as the “Siegfried Switch”), constructed at right angles to the Siegfried Line and located at the base of the triangle formed by the confluence of the Saar and Moselle Rivers. The nineteen-mile-long triangle, ten miles wide at its base, was of vital concern to the Germans because at its apex lay the city of Trier, guarding the Moselle corridor, an important pathway to Koblenz on the Rhine.25

The Orscholz Line provided a bulwark for enemy forces withdrawing under pressure from XX Corps. The Germans manning its defenses poured artillery and mortar fire on the tankers and on engineers attempting to bridge the line’s antitank ditches and deep craters. The 10th Armored Division was unable to drive through the fortifications, and an infantry regiment of the 90th Division had to reinforce the attack.

In three days of fighting the infantry suffered very heavy casualties, not only from enemy fire but also from exposure to cold, mud, and rain. Moreover, the bad weather forestalled American bomber support. At the end of November General Walker abandoned the attempt to penetrate the Orscholz Switch Line and to attack toward Sarrebourg. He sent the infantry regiment to the rear and directed Combat Command A of the 10th Armored Division to join Combat Command B near Merzig to protect the north flank of the XX Corps’ drive on Saarlautern. By 2 December the armor had overcome all resistance in the Merzig sector.

On 1 December the weather had begun to clear—a good omen for the 95th Division’s attack on Saarlautern—and on the morning of 2 December bombers blasted in and around the city. Shortly before noon the bombing lifted. The 2nd Battalion of the 379th Infantry, the 95th Division regiment chosen to seize a bridgehead across the Saar, advanced into the city. By 1500 the troops had captured an enemy barracks on the western edge of Saarlautern, but as they converged on the center of the city they met heavy resistance. The Germans were fighting viciously, house by house and block by block.26 To break through the strongly defended city and force a river crossing too seemed impossible, but fortune favored the attackers.

The Capture of the Saarlautern Bridge

That evening Col. Robert L. Bacon, commanding the 379th Infantry, was handed a photograph taken from an artillery observation plane late in the afternoon. The picture showed a bridge, intact, spanning the Saar between the center of the city and a northern suburb. Colonel Bacon decided on a daring maneuver to capture the bridge

before the Germans could blow it. He planned to send his 1st Battalion in boats across the Saar northwest of the city, where the river makes a loop, to seize the far end of the bridge while the 2nd Battalion attacked toward the near (south) side.

Under cover of darkness, rain, and fog and with all sounds drowned out by the roar of American artillery, assault boats moved up to the crossing site, where the river was only 125 feet wide; the first wave of the commando-type operation was across at 0545. Led by an infantry battalion commander, Lt. Col. Tobias R. Philbin, the assault wave included a platoon from the 320th Engineer Combat Battalion under 2nd Lt. Edward Herbert. On the far bank the column hurried down the road to the bridge, encountering only one German, an unarmed telephone operator. At the bridge was an armored car with a radio operator in it and a German soldier alongside. A company commander bayonetted the radio operator, and Colonel Philbin shot the other when he made a dash for the bridge to trip the switch that would blow it.27

Philbin’s troops first cut all the wires they could find. Following closely behind the infantrymen, the engineers checked the bridge for mines and explosives. About halfway across they found four 500-pound American bombs, without fuses, laid end to end across the bridge. Without stopping, Herbert led his men to check the south end of the bridge. There they encountered a German officer and four enlisted men who refused an order to halt. All were shot.

A few minutes later the engineers saw a second party of several Germans coming toward the bridge dragging a rubber boat. They also refused to surrender and were shot. This gunfire brought on such a heavy concentration of German machine-gun fire that the engineers had to retreat to the north end of the bridge, where machine-gun and artillery fire pinned them down for hours. Not until 1600 were they able to return to the bridge and hoist the American bombs over the side and into the river. The engineers also managed to restore enough flooring to enable some tank destroyers and supply trucks to pass over the north side. After dark the Germans dispatched to the bridge some tanks loaded with explosives, but after the lead tank was hit they abandoned the attempt.

Next day the enemy resumed shelling and made determined efforts to retake or destroy the bridge. A party of German engineers came forward to blow it by hand because the 95th Division’s artillery had knocked out the generators needed to blow the bridge electrically. The Germans were captured, and under questioning one of them revealed that the bridge was virtually a powder keg—channels bored in the piers were filled with dynamite and TNT. Herbert’s platoon eventually removed three tons of the explosives.28

Assaulting Pillboxes on the Far Bank

While the engineers were still trying to clear the bridge, fighting was already under way across the river in the suburbs of Saarlautern: Saarlautern-Roden and Fraulautern to the north and Ensdorf to the east.

Each regiment of the 95th Division had the support of a company of the 320th Engineer Combat Battalion. These suburbs boasted one of the strongest sectors of the entire Siegfried Line. Pillboxes of reinforced concrete were built into the streets and between houses, many extending two or three levels below ground, some with roofs and walls ten feet thick or steel turrets housing 88-mm. guns. The Germans had cleverly camouflaged the pillboxes. Some resembled manure piles or mounds of earth, others ordinary structures. One had been constructed inside a barn, and another was disguised as a suburban railroad station, complete with ticket windows. Ordinary buildings had been fortified with sandbags, wire, and concrete. “Every house was a fort,” reported an officer from Saarlautern-Roden.29

The engineers who had the job of assaulting the pillboxes came under fire not only from the pillboxes themselves but from heavy German artillery emplaced on heights behind the three suburbs, outranging American artillery on the near bank of the river. Rain and overcast prevented air support. German tanks roamed the streets, and protection against them was available only in the two northern suburbs, where the Saarlautern bridge brought across American tanks and tank destroyers. The U.S. position in the southern suburb, Ensdorf, had to depend on bridges the engineers constructed, and German artillery knocked them out almost as soon as they were built. On 8 December artillery fire cost the 320th Engineer Combat Battalion more than $300,000 worth of bridging equipment. To add to the hardships, the Saar River was rising rapidly. By 9 December, when assault boats were still supporting the Ensdorf attack, the river had swollen to a width of between 400 and 500 feet.

It became evident very early that the advance through the suburbs would be slow. Five German pillboxes, mutually supporting on each flank, held up an infantry battalion for two days at Saarlautern-Roden. Tank destroyers came up to fire directly at the pillboxes but without effect. On the afternoon of the third day, 7 December, T/5 Henry E. Barth of the 320th Engineer Combat Battalion’s C Company volunteered to attack the first pillbox. Carrying a heavy beehive charge, he was unarmed but had the covering fire of eighteen infantrymen. Fifty yards from the target the infantrymen, who had suffered several casualties during the approach, took cover in a small building from which they kept up fire on the pillbox’s machine-gun ports until Barth was close enough to rush forward, place his charge on a gun port, and detonate it. The Germans surrendered immediately. Another engineer, Pfc. William E. Farthing, captured a second pillbox singlehanded. Slipping out alone, Farthing crawled toward the pillbox and shoved an explosive charge into its gun port until it touched the gun muzzle, then detonated it.

Engineers advancing under infantry covering fire became the general pattern for taking out the pillboxes in the Saarlautern suburbs. Sometimes after a pillbox had fallen and the engineers and infantrymen inside were waiting for darkness to resume their advance, the Germans would counterattack and have to be driven off. The advance was

costly to the engineers. During December the 320th Engineer Combat Battalion had ten men killed in action and fifty-nine wounded, two so severely that they died in the hospital.30 The pillbox-by-pillbox, street-by-street, house-by-house fighting in early December was so costly to the already depleted 95th Division that by mid-December XX Corps began withdrawing the unit to the west bank of the Saar, replacing it with the relatively fresh 5th Infantry Division.

The plan was for the 5th Division to drive north and ultimately advance alongside XX Corps’ 90th Infantry Division. The latter had not been able to follow the 95th Division over the river but had had to cross some miles to the north. Its main objective was Dillingen, on the east bank of the Saar and covering the right flank of the Saarlautern defenses. Two battalions of the 1139th Engineer Combat Group were to ferry the 90th Division across the Saar. Since no bridge existed, the division selected two sites for assault boat crossings. The 179th Engineer Combat Battalion was to ferry the 357th Infantry over the river on the left (north) flank; the 206th Engineer Combat Battalion was to cross the 358th Infantry on the right. The engineers were to operate the assault boats for the infantry and, after the landings, to bring over supplies and evacuate the wounded. The 179th Battalion also had to construct an infantry support bridge, an M2 treadway for tanks, other vehicles, or both, depending on the outcome of the assault. Late on 5 December the engineers brought the boats down to the riverbank as a ninety-minute artillery barrage drowned the noise of the deployment.

The first boats shoved off at 0415. Darkness protected them from enemy fire, but they had to buck a strong current in the river, which had begun rising the day before. Almost half of the boats the 179th Engineer Combat Battalion operated swamped on the way over or back and went off downstream, smashing into the debris of a blown railroad bridge. Most of the first infantry wave got across without mishap, but for succeeding waves the crossings were progressively more difficult. At daybreak the enemy spotted the boats, and smoke seemed only to attract heavier fire. When the engineers attempted to put down footbridges that first day, the Germans knocked out the spans almost as soon as work started.31

On the far bank of the Saar a strong band of pillboxes barred the way eastward. The 357th Infantry made some progress on the north, but to the south the 358th was unable to cross railroad tracks separating the riverside village of Pachten from Dillingen. At Pachten one of the engineers of the 315th Engineer Combat Battalion, Sgt. Joseph E. Williams, won the Distinguished Service Cross for gallantry in action. Volunteering to breach a pillbox, he was wounded before he could reach it but crawled on and fired his charge. He refused to be evacuated, advanced on another pillbox, and although wounded for the second time succeeded in taking sixteen prisoners.32 However, this

and other acts of heroism by engineers and infantry were not enough to overcome the pillboxes. The only field gun the 90th Division had east of the river was a captured German 75-mm. piece. Frantic calls went back to the near bank for tanks and antitank guns.

To get the tanks and guns across the river the engineers tried to build M2 treadway bridges, but German artillery knocked them out. So intense was the enemy fire that the powerboats used to ferry supplies and evacuate the wounded could be employed only at night; at times ferry operations had to be suspended entirely. Not until 9 December were the engineers able to get heavy rafts into operation. That day the 179th Engineer Combat Battalion crossed tanks and antitank guns on an M2 steel treadway raft, and the 206th Battalion got some jeeps, antitank guns, and tank destroyers across. Later, the 206th had sole charge of the crossing operation.33

During the following week, despite chilling rain and snow, the engineers kept the vehicular ferry running, repeatedly repairing damage from heavy German artillery fire. As the river began to recede the engineers also built a corduroy road of logs on the far shore to keep the tanks from miring down when they rolled off the rafts.34 By 15 December, after the tanks as well as the 359th Infantry had crossed the Saar, the 90th Division was penetrating fortifications protecting Dillingen. Then the attack halted for several days to give the 5th Division time to relieve the 95th in the Saarlautern bridgehead and come abreast of the 90th. The advance resumed on 18 December. Resistance proved surprisingly light, and in three hours most of Dillingen was captured.

The Withdrawal

Next afternoon, on 19 December, General Patton ordered the 90th Division to give up its hard-won Dillingen bridgehead and withdraw west of the Saar. By that time German attacks in the Ardennes, beginning on 16 December, had been recognized as a full-scale offensive. After a conference with Eisenhower and Bradley at Verdun on the morning of 19 December, Patton committed to the American defenses the bulk of Third Army, including the 90th and 5th Infantry Divisions, leaving the 95th Division to hold the Saarlautern bridgehead—the only foothold left east of the Saar.

For the withdrawal the engineers had to depend on assault boats and the M2 treadway ferries because a heavy ponton bridge they had planned to erect was not yet in place. The first tanks and trucks went back west on the night of 19 December After artillery fire knocked out one of the ferries during daylight operations, the crossings continued only at night. The 206th Engineer Combat Battalion was in charge of the withdrawal. By noon of 22 December the 90th Division had recrossed the Saar and was headed north to take its place in the hasty defense against the last great German counteroffensive in the west.35

South of Third Army’s withdrawing elements, American and French forces also steeled themselves for the German

blow. From mid-September on, Patton had been fighting with a new Allied army group on his flank in the south. Another seaborne thrust into German-occupied France on 15 August had rapidly cleared the southern tier of the country and linked with the 12th Army

Group to form a continuous line from the Mediterranean to the English Channel. Mounted from the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, the assault and the subsequent advance north relied heavily on engineer elements for success.