Chapter 21: The Ardennes: Engineers as Infantry

A cold rain was turning to snow on the afternoon of 8 December 1944, when the lead trucks of the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion pulled into the Schnee Eifel, a wooded ridge just inside the German border east of the Ardennes and southeast of Liege. The 81st Battalion had landed in France only a few days before with VIII Corps’ 106th Infantry Division. The division, the newest on the Western Front and the youngest (the first containing a large number of eighteen-year-old draftees), had moved forward immediately after landing to take over a sector from the 2nd Division, which was redeploying northward to reinforce a First Army attack on the Roer River dam.1

The Schnee Eifel landscape looked like a Christmas card, with snow-tipped fir trees dark against white hills. In the folds of the hills lay small villages set in hollows for protection against blizzards. Here the engineers found billets. The 81st Engineer Combat Battalion settled in at Heuem, on the road leading east toward the German border from St.-Vith, Belgium, an important road center and site of division headquarters. The battalion’s Company B, supporting the 423rd Infantry, bivouacked about 1½ miles east at Schoenberg. Crossing the border into Germany, Company A found billets at Auw, only three miles as the crow flies behind the most forward position on the VIII Corps front, a six-mile stretch of the Schnee Eifel containing Siegfried Line pillboxes.

The first 20 miles of the 85-mile-long Ardennes front, beginning at Monschau, were held by V Corps’ 99th Infantry Division. Also new to the theater, the division had arrived on the Continent during November 1944. The southern two miles of its portion of the front lay along a narrow, seven-mile-long valley known as the Losheim Gap. There the V Corps sector ended and that of the VIII Corps began. The next five miles of the Losheim Gap were held by the 14th Cavalry Group, a light reconnaissance unit that the 106th Division had inherited when the 2nd Division moved north.

The 106th Division sector ended about five miles below the Schnee Eifel salient, at the village of Luetzkampen, and there the 28th Infantry Division area began. Near this point, where the nar-

row, swift Our River began to define the border between Belgium and Germany, the American positions swung southwest to the Belgian side of the river along a high bluff carrying a road (Route 16) known as the “Skyline Drive,” which continued south through Luxembourg. Responsible for about twenty-three miles of the front in Belgium and Luxembourg, the veteran 28th Division was resting and training replacements for the more than 6,000 casualties it had suffered during the battle of the Hürtgen Forest, more casualties than any other division in that action.2

Beginning on 10 December, elements of the 9th Armored Division, another newcomer to ETOUSA, took over the next six miles south along the front. The bulk of the armored division, however, was in reserve fifty miles north. Near the point where the Schwarz Erntz River flowed into the Sauer River the 4th Infantry Division portion of the front began. This division had also been badly battered in the Hürtgen Forest, having suffered more than 4,000 casualties, second in losses only to the 28th.3 The 4th Division held the VIII Corps front along the Sauer and the Moselle to the border between Luxembourg and France, where the First Army sector ended and that of Third Army began.

The long front, manned by troops weary from combat or not yet tested in battle, was very lightly held in some places. Along two miles of the Losheim Gap, through which German armies had poured westward in 1870, 1914, and 1940, the Americans patrolled so lightly that Germans on leave often walked across to visit friends and relatives behind the American lines. For two months the front had been quiet except for sporadic mortar and artillery fire. Across the narrow rivers or from Siegfried Line positions American and German outposts watched each other.4

The Storm Breaks in the Schnee Eifel

It was snowing on the evening of 11 December when the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion relieved the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion in the Schnee Eifel. The 81st Battalion’s foremost task was road maintenance—removing snow and filling shell holes. Behind the front road maintenance was the responsibility of the 168th Engineer Combat Battalion, attached to VIII Corps. Operating quarries to provide crushed rock was part of the road repair job, but engineers also manned sawmills to provide lumber for a First Army winterization program, which called for wooden huts and shelters.5

The crossroads village of Auw marked the line dividing the 14th Cavalry Group sector from that of the 422nd Infantry, 106th Division. There Company A of the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion had comfortable billets, with headquarters men in one house and the three platoons in three others. Before dawn on 16 December heavy artillery fire awakened the men. They found to their surprise that the villagers were up,

dressed, and huddled in their cellars. Then they remembered that the evening before a young woman had been observed going from house to house, evidently carrying a warning. But there was no reason to suppose that this was more than a local attack, and when the artillery fire died away the company commander, Capt. Harold M. Harmon, sent out his platoons on road work as usual at 0800. The 1st Platoon under Lt. William J. Coughlin went to the 422nd Infantry headquarters at Schlausenbach, about a mile away, the 3rd Platoon under Lt. David M. Woerner to the 422d’s 3rd Battalion in the pillbox area, and the 2nd Platoon under Lt. William E. Purteil to work in and near Auw. Captain Harmon then left for Heuem for the usual morning conference of company commanders.6

The engineers at Auw—the only troops in the town—heard rifle and machine-gun fire about 0930. It seemed close, but because the day was cloudy with drizzle and patches of heavy fog, nobody could find out what was happening. As soon as the engineers recognized the white-clad enemy, the 2nd Platoon and the headquarters men took up positions in two buildings and began firing. At that point, the 1st Platoon, having heard the sound of battle from the direction of Auw, returned under heavy fire, dashed into the house where it was billeted, and began returning enemy fire coming from a barn across the road, using tracer ammunition to set the barn afire. Ten German infantrymen ran out and were cut down by Company A cooks.

About 1000 Captain Harmon returned from Heuem, where he had learned that Lt. Col. Thomas J. Riggs, Jr., the battalion commander, had orders to employ the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion as infantry. The plan finally adopted was to commit the engineers with their respective regimental combat teams. Unable to find his men in Auw, Harmon started for the 422nd Infantry area to locate his 1st Platoon. On the way he learned that the enemy had broken through the cavalry group defenses in the Losheim Gap and was attacking in great force. Returning to Auw, he was fired on by an enemy column but made a dash for it; although his jeep was riddled he managed to reach his 2nd Platoon, which German tanks were about to encircle. He got the men on trucks and on the road back to Heuem.

Four German Tiger tanks came up the main street of Auw. Infantry was riding on the tanks, and most of the turrets were open; the tankers evidently expected little opposition. The engineers in their strongpoints opened up with rifles and machine guns, claiming “considerable” casualties before the Germans realized what was happening. The German infantry dropped to the ground, the tank turrets clattered shut, and the tanks opened fire with 88-mm. guns on the two houses that the engineers occupied. The headquarters men managed to escape, but then the full tank attack fell on Lieutenant Coughlin and his 1st Platoon. Eight rounds of point-blank 88-mm. fire burst in the building but miraculously caused no casualties, though small-arms fire wounded several men. Desperate,

Coughlin decided to risk a dash across an open field behind the house. At 1500 he gave the order to withdraw. T/5 Edward S. Withee insisted on remaining behind to cover the withdrawal with his submachine gun. Captured after his heroic stand, Withee later was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

That afternoon in a sudden snowstorm Captain Harmon became involved in a 422nd Infantry attempt to retake Auw. He moved thirty engineers to a point about a mile west of the town, but by that time American artillery was falling on Auw. Before the 422nd could halt the American fire German artillery fire became so heavy that Harmon’s party, having suffered ten casualties, had to withdraw to Heuem.

By the evening of 16 December it had become plain that the German attack, which the 106th Division had at first considered only an attempt to retake Siegfried Line pillboxes, was in fact an offensive on a grand scale all along the Ardennes front from Monschau to the Luxembourg border. In the Schnee Eifel the Germans committed the entire LXVI Corps of General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Panzer Army. One of its divisions was to encircle and cut off the 422nd and 423rd Infantry regiments in the pillbox area and take St.-Vith. The other was to attack the 424th Infantry south of the pillbox positions, blocking the western and southern exits from St.- Vith.

The German pincer movement around the pillbox positions, successfully begun on the north with the capture of Auw, continued during the early morning hours of 17 December with the taking of Bleialf in the 423rd Infantry’s area to the south. The two German divisions rejoined at Schoenberg later that morning. At Heuem, only 1½ miles to the west, the engineers on orders from the 106th Division withdrew at 0930 to a point about five miles west of St.-Vith. There they were fed and issued cigarettes, socks, galoshes, and ammunition. But they were to have little rest. At noon Colonel Riggs received orders to round up all the available men of the 81st and 168th Engineer Combat Battalions to halt a German attack on St.-Vith.

On a wooded ridge about a mile east of the town, astride the road from Schoenberg, Colonel Riggs assembled his little force, which had only a few bazookas and machine guns. In his 81st Engineer Combat Battalion, Company A, after losses on 16 December, had only sixty-five men; Headquarters and Service Company had only fifty, some of them clerks and cooks. The 168th Engineer Combat Battalion had the remnants of two companies and the bulk of a third. The men, with few tools, had hardly finished digging their foxholes when at 1600 three German self-propelled 88-mm. assault guns, supported by infantry, came down the road from Schoenberg. The Germans knocked out a divisional antitank gun in their path, forced a tank destroyer to withdraw, then turned their 88-mm. guns on engineers of the 168th Battalion in the most forward position, inflicting heavy casualties. Meantime, a forward divisional observer directed a P-47 fighter-bomber to the spot. After a number of passes the plane set one of the German gun carriages afire.

The defenders succeeded in delaying the enemy until dusk, when tanks of the U.S. 7th Armored Division began coming through the snow and mist

Engineers drop barbed-wire rolls to prepare defensive positions

down the road from St.-Vith. By that time one of the German assault guns had broken through the 168th Battalion defenses and reached the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion’s position. Jumping out of their foxholes, the engineers stopped the gun by pulling a chain of mines across the road. One of the 7th Armored Division tanks finally knocked the gun out.

Next morning, Company A, 81st Engineer Combat Battalion, and the tankers continued to hold against strong German attacks. In the afternoon a group under Colonel Riggs counterattacked, driving some German infantrymen out of hillside positions. The defenders could then consolidate their lines, but shortly after dark a message came from division headquarters that signaled the beginning of the end. Threatened by German tanks that were outflanking the defenders on the Schoenberg road to the east, the 106th Division headquarters was withdrawing from St.-Vith ten miles west to Vielsalm.

The next two days, 19 and 20 December, were fairly quiet on the Schoenberg road, with German activity limited to patrol actions and intermittent shelling. During the night of the nineteenth the engineers laid hasty minefields along possible avenues of tank approach and covered foxholes with logs for protection from tree bursts. Patrols went into St.-Vith to salvage anything useful—food, blankets, clothing. From their foxholes on the Schoenberg

road that night the engineers could see flashes in the distant sky—to the north where V Corps was trying to hold the Sixth Panzer Army; to the east beyond Schoenberg where the 422nd and 423rd Infantry regiments, hopelessly cut off, were making their last stand; to the south where the 424th Infantry, bolstered by a combat command of the 9th Armored Division, was successfully covering its withdrawal to Vielsalm. Far to the southwest flashes showed where the battle for Bastogne was raging.

By the morning of 20 December German successes in the Bastogne area had isolated the St.-Vith forces from the rest of VIII Corps. During the afternoon the 7th Armored Division commander received word that the 82nd Airborne Division was on its way to help, but it was already too late. The Germans were impressed by the intensity of American artillery fire east of St.-Vith and by the number of American tanks—“tanks were everywhere,” reported the 18th Volksgrenadier Division on 20 December—and they assumed that the force blocking the Schoenberg road was stronger than it actually was. Nevertheless, the Germans were determined to break through the defenses as soon as they could extract their own artillery and tanks from a traffic jam that had built up around Schoenberg.

This the Germans accomplished by midafternoon on 21 December. Commencing at 1500 and continuing until well after dark, the enemy directed on the tankers and engineers a concentrated barrage of artillery, rocket, and mortar fire, inflicting heavy casualties. Company A, 81st Engineer Combat Battalion, for example, lost forty of its sixty-five men.

The engineers had not mined the road because of a promised 7th Armored Division counterattack. Without warning—the German barrage had knocked out all communications—shortly before midnight four Mark VI (Tiger) and two Mark IV tanks, with supporting infantry, came over a rise in the road, close to where some Sherman tanks were positioned at the American foxhole line. Firing a volley of illuminating flares that silhouetted the Shermans and blinded their crews, the German tanks picked off three of the Shermans and overran the foxholes. Colonel Riggs attempted to organize a defense at a ridge farther back, but it was hopeless. The Americans broke up into small parties. Wandering about in the heavy snow and darkness, most of the men, including Colonel Riggs, were captured. Only eight officers and enlisted men from Company A, 81st Engineer Combat Battalion, and thirty-three officers and men from the Headquarters and Service Company were able to reach Vielsalm.

Company C, with the 424th Infantry south of St.-Vith, protected the approaches to the town by guarding and blowing bridges; when 9th Armored Division tanks arrived on 20 December the company acted as infantry in support of the tanks. The bulk of Company B of the engineer battalion was lost when the enemy captured most of the 422nd and 423rd Infantry regiments.

For its first engagement the 81st Engineer Combat Battalion won the Distinguished Unit Citation. At St.-Vith from 16 to 23 December 1944, the battalion “distinguished itself in battle with such extraordinary heroism, gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in overcoming unusually difficult and hazardous conditions in the face of a numerically

superior enemy, as to set this battalion apart and above units participating in the same engagements.”7

Blocking Sixth Panzer Army’s Drive to the Meuse

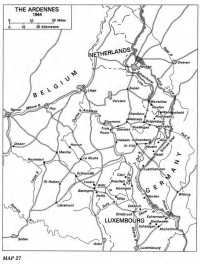

On the night of 16 December a heavy concentration of enemy artillery fire pounded and shook the eastern and southern flanks of V Corps’ 99th Division. (Map 27) Under cover of this barrage, tanks of the German Sixth Panzer Army were advancing west toward the Meuse, creating the major threat in the northern sector of the Ardennes. At the extreme north, infantry of /XVII Corps attacked the Siegfried Line towns of Monschau and Hoefen on the morning of 16 December. These attacks failed, but in the Losheim Gap region (the central and southern portions of the northern sector) the Germans threw in considerable armor, and the tank columns broke through.8

Around midnight on 16 December a message came to V Corps’ 254th Engineer Combat Battalion, which was repairing roads in support of the 2nd and 99th Divisions. The unit was bivouacked in the woods near Büllingen at the southern end of the corridor along which the 2nd Division was attacking through the 99th toward the Roer River. The engineers were on a two-hour alert to act as infantry. But in the darkness the roads around the bivouac became so jammed with American tanks and other traffic that the battalion’s commanding officer was not able to reach 99th Division headquarters and return with orders until 0230. Engineer Companies A, B, and C were to form a defensive line south and east of Büllingen to protect American tanks and tank destroyers withdrawing under pressure from German forces coming up the road from Honsfeld, three miles to the southeast.

At 0600 the engineers of Company B, stationed on the road to Honsfeld, saw white and red flares about eight hundred yards away and heard tracked vehicles approaching. When they heard shouts in German, the engineers opened fire with rifles, rifle grenades, and machine guns. The German infantry riding on the lead tank and in six half-tracks jumped down and attacked, but they were driven back. The vehicles withdrew. Twenty minutes later the German infantry reappeared, followed by tanks. The tank fire was ineffective against the dug-in engineers, and the attackers were again repulsed. Ten minutes later, as the sky was getting light, a third force came up the road. This time tanks were in the lead, and they overran Company B’s position, crushing two machine guns. They also passed over foxholes where engineers were crouching, but injured only three Americans.

The engineers continued to fire on the German infantry, but the 254th Engineer Combat Battalion’s position was now hopeless. The men were ordered to fall back on Butgenbach while fighting a delaying action through Büllingen.9 Many of the men were cut off, and the situation at Büllingen was so confusing because communications were out that when the commanding

Map 27: The Ardennes, 1944

officer of the 254th arrived at Butgenbach he reported to Maj. Gen. Walter E. Lauer, commanding the 99th Division, that his battalion had been destroyed. According to Lauer, “It was a dramatic moment at my C.P. at about noon that day when the details of the action were reported. I awarded the battalion commander then and there the Bronze Star Medal, and gave him my lunch to eat.”10 Later the engineer officer discovered that he had not lost his entire battalion. Although many men had been killed or captured, others, in groups of two or three, made their way back to Butgenbach or Wirtzfeld.11

The tanks that came up on the Honsfeld road early on 17 December belonged to Obersturmbannführer Joachim Peiper’s Kampfgruppe Peiper, the armored spearhead of I SS Panzer Corps, the strongest fighting unit of Sixth Panzer Army, which had broken through at the Losheim Gap. By 1030 on 17 December Peiper’s tanks were rolling into Büllingen, but instead of continuing northwest to Butgenbach as the Americans expected, most turned southwest out of the town. Although Büllingen was a target of the 12th SS Panzer Division, Peiper had detoured through the town to avoid a stretch of muddy road between Honsfeld and Schoppen, his next objective to the west. He had also learned that there were gasoline dumps in Büllingen, and he filled his tanks from American dumps, using American prisoners as labor.12

Büllingen was an important supply area, with dumps and service troops. Headquarters Company and Company B of the 2,1 Engineer Combat Battalion, part of the 2nd Infantry Division, were billeted there. Ordered to hold the town at all costs, Company B put up a determined defense, but once in the town German tanks took up positions at intersections and cut all traffic. The engineer company split into platoons, fought until its ammunition was gone, and then had to withdraw. Four officers and fifty-seven enlisted men of Headquarters Company were surrounded. From the basement of their billet they fired at all the enemy infantry that came in view, but they had no bazookas to use against tanks. Nevertheless they were still reported to be holding out on the night of 18 December, when advance elements of the 12th SS Panzer Division began arriving in the town to direct a coming fight at Butgenbach. After that, nothing more was heard from Headquarters Company, and the men were assumed to be either killed or captured.13

The arrival of Peiper’s tanks at Büllingen on the morning of 17 December brought the first realization of the scale of the German offensive, because communications had gone out when the Germans hit the 99th Division regiments stationed along the West Wall on 16 December. On the morning of the seventeenth Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, commanding V Corps, decided to pull his corps back to a defensive position on the Elsenborn ridge northwest of Büllingen. Two infantry regiments of his 2nd Division were attacking West Wall positions about five miles to the northeast near Wahlerscheid, sup-

ported by a regimental combat team composed mainly of the 99th Division’s 395th Infantry. The withdrawal route of these forces ran south from Wahlerscheid to the twin villages of Krinkelt and Rocherath, then northwest of Elsenborn through Wirtzfeld. Infantry of the collapsing 99th Division was also passing through the twin villages on the way to Elsenborn. The Germans had made deep penetrations along the roads leading west and could be expected to attack Krinkelt and Rocherath.

During the dangerous withdrawal the engineers supporting both divisions played an important part. The 99th Division’s 324th Engineer Combat Battalion was with the 395th Regimental Combat Team in woods east of Wahlerscheid. When the combat team received the task of covering the 2nd Division’s move south, the engineers assumed defensive positions as infantry. At one time on 17 December the battalion was cut off and surrounded by the enemy, but managed to escape and join the forces at Elsenborn.14

At dusk on 17 December Company C of the 2nd Engineer Combat Battalion, organic to the 2nd Infantry Division, was working behind the infantry to block the road to the east. The infantry felled trees and created abatis, which the engineers mined and booby-trapped. By the time the company reached the twin villages enemy riflemen were close behind, but thick fog that lay close to the snow-covered ground concealed the unit. When Company C reached Rocherath the village was burning, and traffic on the road was completely blocked. The company turned off the main road and moved west along forest trails to Elsenborn, on the way clearing from the trails abandoned trucks and guns and putting down matting, brush, and even abandoned bed rolls to get the unit’s vehicles through to Elsenborn. Next day, 18 December, the engineers worked on the Elsenborn defenses, placing mines and wire, but that night part of the company had to return to Krinkelt. Under heavy pressure the last U.S. unit in the town, the 38th Infantry, was getting ready to pull out, and engineers were needed to set up roadblocks behind the regiment to protect its withdrawal.

The road to Krinkelt was under heavy artillery fire. More than once the engineers had to jump from their trucks and run; several trucks were damaged. They arrived at Krinkelt in the blackness, discovering next day, 19 December, that the enemy was edging closer, obviously preparing for a final night attack. At 1730, in darkness and fog, the 38th Infantry began to pull out. The engineers, who could not set up their roadblocks until all the tanks of the covering force had withdrawn, were the last Americans left in the town. “Under the very noses of the pressing SS troopers,” they went to work installing roadblocks at all important corners. Enemy tank, artillery, and small-arms fire killed a number of men, but the survivors managed to finish the job and withdraw to Elsenborn.15

By 20 December a regiment of the 1st Infantry Division had reinforced the 2nd and 99th Divisions at Elsenborn. On the north, the 9th Division took over the Monschau–Hoefen sector. These two positions held. At the Elsenborn ridge, which the Germans called the

“door posts,” the 12th SS Panzer Division gave up the fight on 23 December when the unit ran into a fresh 1st Division regiment.16 Thereafter the Germans would not risk at Elsenborn anything better than second-line troops capable only of defensive action.

About the time the 12th SS Panzer Division was moving against Krinkelt and Rocherath, Peiper’s Kampfgruppe swung west toward its objective, a Meuse crossing at Huy, about fifteen miles upriver from Liege. At dusk on 17 December Peiper’s lead tanks were approaching Stavelot, on the northern bank of the Amblève River forty-two miles short of Huy. Peiper was already deep into the area where First Army’s service troops were working behind the combat zone. A few miles west of Stavelot at Trois Ponts on N-23, Peiper’s route to the Meuse, was the headquarters of the 1111th Engineer Combat Group, whose battalions were supporting First Army’s winterization program. The 291st Engineer Combat Battalion was operating a sawmill just west of Trois Ponts and a company of the 202nd Engineer Combat Battalion another at Stavelot.

The first news of the enemy breakthrough came to the 1111th Group commander, Col. H. W. Anderson, at 1005 on 17 December, when he learned that the Germans were near Butgenbach. This posed a serious threat to Malmédy, five miles northeast of Stave-lot. At Malmédy Anderson had about two hundred men of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion, aided by the 962nd Engineer Maintenance Company, building a landing strip for liaison planes near First Army headquarters at Spa. He sent the commanding officer of the 291st, Lt. Col. David E. Pergrin, to Malmédy to take charge of the group’s units there. Later in that day they were augmented by the 629th Engineer Light Equipment Company, which had been doing road work near Butgenbach but had managed to extricate itself ahead of the German advance.17

Anderson ordered his engineers at Malmédy to prepare to defend the town. Prospects for defense looked bright soon after Pergrin’s arrival, especially when elements of the 7th Armored Division rumbled into the town. But the armor was only passing through on its way to St.-Vith, and as the vehicles disappeared down the road most of the First Army rear units, according to an engineer account, fled in panic, leaving behind food, liquor, documents, footlockers, clothing, and all sorts of equipment. The engineers, armed only with mines and a few bazookas, stayed.18 When Colonel Pergrin was asked later why his men did not leave with the other units, he said the reason was “psychology.” Combat units moving up to the front had taunted the road builders they passed, “You engineer so-and-sos! Why don’t you come on up there and fight?”19

By noon of 17 December the engineers had set up roadblocks on the edge of town. An hour later, patrols reported seeing sixty-eight enemy armored vehicles including thirty tanks on a road a few miles to the southeast. About 1430 Colonel Pergrin was standing on a hill

near town when he heard “an awful lot of noise” in the valley below; then four American soldiers ran toward him, screaming.20 They were survivors of the “Malmédy massacre” in which Peiper’s men shot up a convoy of field artillery observers that crossed their path, then rounded up about eighty-five prisoners, marched them into a field, and at a signal shot them down with machine-gun and machine-pistol fire. Pergrin brought the four survivors back to Malmédy in his jeep. Their story did not shake the determination of his engineers to defend Malmédy “to the last man.”21

On the chance that Peiper would bypass Malmédy (as he did) and head for Stavelot, Pergrin sent a squad of his engineers equipped with twenty mines and one bazooka south to set up a roadblock at Stavelot. They emplaced a hasty minefield at the approach to a stone bridge leading into the town and waited. At 1900 three Mark IV tanks came toward the bridge. The first struck a mine that blew off its treads; the others withdrew. Two of the engineers, Pfc. Lorenzo A. Liparulo and Pvt. Bernard Goldstein, tried to follow the tanks in a jeep. They were wounded by German fire, Liparulo fatally, but the Germans did not attack again until early next morning. By that time a company of the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion, towing 3-inch antitank guns, had reinforced the engineer roadblock. The armored infantry managed to repulse a German infantry attack but was no match for the 88-mm. guns on German tanks that began rumbling over the bridge into the town about 0800.22

While the fighting was still going on inside Stavelot, Peiper turned some of his tanks west toward Trois Ponts, the next town on his route to the Meuse. In his own words, “We proceeded at top speed towards Trois Ponts in an effort to seize the bridge there. ... If we had captured the bridge at Trois Ponts intact and had had enough fuel, it would have been a simple matter to drive through to the Meuse River early that day.”23

Trois Ponts, as its name suggests, boasted three bridges—one over the Amblève that provided entry to the town; another over the Salm within the town, carrying the main highway west; and a third over the Salm southeast of town. By the time Peiper turned his lead tanks toward Trois Ponts the 1111th Engineer Combat Group had prepared all three bridges for demolition. Company C of the group’s 51st Engineer Combat Battalion, ordered the night before to defend the town, had placed charges on two of the bridges, and a detachment of the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion had prepared the third. The engineers were armed only with bazookas and machine guns, but during the morning a 57-mm. antitank gun with its crew, somehow separated from the 526th Armored Infantry Battalion, turned up in the town and was used to block the road from Stavelot.

At 1115 on 18 December, when the first enemy tank came into sight, the engineers blew the bridge over the Amblève. Half an hour later the lead tank ran into the roadblock. The 57-mm. gun immobilized it, but fire from other tanks knocked out the gun and killed four of the crew. Finding the bridge

blown, Peiper’s men hesitated for about forty-five minutes. Though the tanks could not cross, the narrow, shallow Amblève offered no obstacle to infantry. The defenders expected an infantry attack, and Company C spread out for 500 yards along the steep far bank. The Germans apparently decided not to risk an infantry crossing at that point, but they did attempt to cross at the bridge southeast of town, which the 291st Engineer Combat Battalion blew while two German soldiers were on the span.

Peiper’s lead tanks then turned north, seemingly probing for a way to outflank the town. Colonel Anderson had the bridge over the Salm within Trois Ponts destroyed. In midafternoon he departed for First Army headquarters, leaving the defense of Trois Ponts in the hands of a new arrival on the scene, Maj. Robert B. Yates, the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion’s executive officer.

As darkness fell at 1700, Major Yates drew his men back to the center of Trois Ponts where they could hear the sound of enemy armor and vehicles all night. Yates employed several ruses to hide his weakness in men and weapons from the enemy. He moved small groups of riflemen, firing, from point to point; he had a heavy truck driven noisily around the streets to mimic the sound of arriving artillery; and to create the impression that reinforcements were coming in from the west, all night he ran his five trucks out of town with lights out and back in town with lights on. Also, he received an unexpected assist from a tank destroyer that his men had set afire to keep it out of enemy hands—the 105-mm. shells within the burning vehicle continued exploding for some time. These deceptions apparently worked, for the Germans did not attack. Just before midnight their tanks moved north up the road toward Stoumont.24

That day, 18 December, infantry of the 30th Division arrived to man the defenses at Malmédy and Stavelot. One of the division’s regimental combat teams went into position to interrupt Peiper’s tanks at Stoumont, but the engineers were the sole defenders of Trois Ponts all that day and the next.25 Late on 19 December a small advance party of paratroopers arrived from the west. They were from the 82nd Airborne Division, elements of which Maj. Gen. Matthew B. Ridgway, commanding general of the XVIII Airborne Corps, had rushed forward to help stop Peiper. The newcomers did not know that the critical bridgehead of Trois Ponts was in friendly hands, much less that it was held by a single engineer company. Greeting the paratroopers, Major Yates joked, “I’ll bet you guys are glad we’re here.”26

Next afternoon, following an enemy artillery barrage that killed one engineer and wounded another, a company of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment arrived at Trois Ponts with a platoon of airborne engineers. But when the infantrymen took up a position on a hill east of town they were surrounded, and troops of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion had to provide covering fire to extricate the airborne

force. Not until dusk on 21 December were Yates’ men able to withdraw from the defensive positions they had held for five days and journey to their battalion headquarters at Marche, far to the west. Exhausted and numb from the bitter cold (the temperature had dropped to 20° F.), they had been “spurred to almost superhuman effort” by the “heroic example and leadership of Major Yates.”27

Combined elements of the 82nd Airborne, 30th Infantry, and 3rd Armored Divisions stopped Peiper on the Amblève near Stoumont. The deepest penetration in the Battle of the Bulge was to be made not by the Sixth Panzer Army but by the Fifth Panzer Army to the south.

Delaying Fifth Panzer Army from the Our to the Meuse

On the Skyline Drive in Luxembourg it had been snowing or raining off and on throughout the first two weeks in December. Clearing away accumulations of snow and icy slush was the principal task of Company B of the 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion, quartered at Hosingen. The company was supporting the 28th Division’s 110th Infantry, located in the center of the division’s frontline positions. Other companies of the same engineer battalion were supporting the 112th Infantry on the north and the 109th Infantry on the south.

Because the 28th Division could not hope to defend every mile of its 23-mile-long front, the division commander had set up a series of strongpoints; Hosingen was one. Garrisoned by Company K of the 3rd Battalion, 110th Infantry, Hosingen overlooked two roads from Germany that crossed the Our River, wound over the Skyline Drive, descended to the Clerf River, and then continued west for fourteen miles to the important road center of Bastogne. One road, crossing the Skyline Drive about two miles north of Hosingen, was a paved highway, the best east-west route in the sector. About two miles west of the drive the road ran through the castle town of Clerf on the Clerf River, where the 110th Infantry had its headquarters. The other road, muddy and winding, crossed the Skyline Drive just south of the outskirts of Hosingen. The engineers knew this secondary road well. They had accompanied infantry over it on several small raids into Germany, using rubber boats to cross the Our, and on it they had emplaced an abatis and planted a minefield.

At 0530 on 16 December, a German barrage of massed guns and rockets reverberated over the Skyline Drive for about half an hour. As dawn broke, cloudy and cold with patches of ground fog, infantry of the 26th Volksgrenadier Division came up the muddy road. Some troops bypassed Hosingen, but one battalion entered the town. Company K, 110th Infantry, and Company B, 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion, put up a strong defense. House-to-house fighting continued all day, but no German tanks appeared until the morning of the seventeenth—German engineers had failed to erect heavy bridging at the nearest Our River crossing. When the tanks reached Hosingen they set the town afire, but the defenders held out until the evening of the seventeenth, after Clerf had surrendered.

Placing charges to drop trees across roadways

Communications had been out since the heavy opening barrage on the sixteenth, so the headquarters of the 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion at Eschdorf, twelve miles to the southwest, had no word from this last bastion until 0050 on 18 December. Then an officer got through to report that the evening before, the troops at Hosingen had still been fighting. Out of ammunition and beyond the range of American artillery, they were withdrawing from house to house, using hand grenades. After that nothing more was heard.28

During the night of 17 December the Germans, having secured two bridges over the Clerf River at Clerf and farther south at Drauffelt, moved swiftly west in several columns. One turned south toward the 28th Division command post at Wiltz, twelve miles east of Bastogne.

The defenders of Wiltz included 600 men of the 44th Engineer Combat Battalion. This unit, along with the 168th, the 159th, and the 35th Engineer Combat Battalions and Combat Command Reserve of the 9th Armored Division, made up General Middleton’s VIII Corps reserve. Until noon of 17 December the 44th Battalion had been working in the corps area as part of the 1107th Engineer Combat Group, maintaining roads and operating two sawmills, a rock quarry, and a water point. Then General Middleton sent the battalion to Wiltz and attached it to the 29th Infantry Division, whose commander, Maj. Gen. Norman D. Cota, gave the engineers the mission of defending the town. Cota’s plan called for securing Wiltz and covering all approaches to the town. Supporting the engineers were remnants of the 707th Tank Battalion with six crippled tanks and five assault guns; four towed 3-inch guns from a tank destroyer battalion; a depleted battalion of 105-mm. divisional artillery; and a provisional battalion of infantry organized from headquarters troops. The 105-mm. howitzers went into battery along a road leading southeast from Wiltz, while the rest of the defense force manned a perimeter north and northeast of town, north of the Wiltz River.

About noon on 18 December tanks and assault guns of the Panzer Lehr Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion struck the forward outposts, overrunning a section of tank destroyers. The engineers held their fire until the German infantry arrived behind the tanks and then cut it down. But the weight of armor

proved too strong, and the engineers had to withdraw to a second line of defense.

During the night activity on both sides was limited to intense patrolling and harassing fire. Next morning the defenders were able to dig in and generally improve their positions, but in the middle of the afternoon the Germans attacked strongly from the north, northeast, and east with tanks accompanied by infantry armed with machine pistols. The three-hour attack cut the engineers’ Company B to pieces. At dusk the 44th Engineer Combat Battalion was forced to withdraw into Wiltz, having suffered heavy casualties.

The engineers still felt confident, believing that the attack had cost the Germans dearly and gained them little ground. They also felt safer after they blew the bridge over the Wiltz. But about 1800 a new German column was reported approaching from the southeast, on the same side of the river as the town. A few hours later the enemy had cut all roads to Wiltz, and ammunition was running low. At 2130 the defense force received orders to pull back toward American lines to the rear. It was a grueling and bloody withdrawal through German roadblocks and a gauntlet of fire. The 44th Engineer Combat Battalion suffered heavily during the evacuation, losing 18 officers and 160 enlisted men.29

While the 44th Engineer Combat Battalion was defending Wiltz, two of the VIII Corps’ reserve engineer battalions were engaged elsewhere. On the north the 168th, supporting the 106th Division, was astride the road from Schoenberg to St.-Vith; on the south the 159th, attached to the 4th Division, was preparing to bar the way to Luxembourg City. Thus, by 1600 on 17 December, General Middleton had only one reserve engineer battalion, the 35th. Relieving the battalion of attachment to the 1102nd Engineer Combat Group, he assigned it to the defense of Bastogne.30

By then Bastogne was in great danger. In midafternoon the commander of Combat Command Reserve of the 9th Armored Division (spread out along the paved road leading into the city from Clerf) reported that the Germans were overrunning his most advanced roadblock. The enemy was then less than nine miles from Bastogne. General Middleton was expecting reinforcements—the 101st Airborne Division from SHAEF reserve and Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division from Third Army—but these units could not arrive until 18 December. In the meantime, the engineers would have to guard the approaches to Bastogne. At the suggestion of the VIII Corps engineer, a second engineer combat battalion was committed. It was the 158th, not a part of Middleton’s formal reserve but part of First Army’s 1128th Engineer Combat Group, which was working in his area and could be called upon “in dire circumstances.”31

The 158th Engineer Combat Battalion received orders at 1730 on 17 December to take over the 35th Engineer Combat Battalion’s 3,900-yard left flank extending from Foy, a town on the main paved road (N-15) leading into Bastogne from the north to Neffe, a

Road maintenance outside Wiltz, Belgium

town just south of the main paved road (N-28) from the east—the most likely direction of the German advance. The VIII Corps engineer advised that a takeover in the blackness of the winter night would be too difficult, and the commander of the 158th, Lt. Col. Sam Tabet, postponed the arrival of his battalion at the perimeter until daybreak at 18 December. Company A began to dig in on the left near Foy, Company B near Neffe, and Company C near Luzery, just north of Bastogne. To help hold his line of defense astride the roads along which the Germans were advancing, Tabet obtained 4 tank destroyers mounting 105-mm. howitzers, 8 light tanks, and 2 Shermans, all taken from ordnance shops and manned by ordnance mechanics. The battalion also managed to round up 950 antitank mines.32

During the daylight hours of 18 December the engineers sent out reconnaissance parties and set up roadblocks, using chains of mines, bazookas, .50-caliber machine guns, and rifle grenades. Late that evening they were attached to the 10th Armored Division, whose Combat Command B was expected to arrive momentarily. Around midnight they heard rifle and automatic weapons fire to the east, and Germans overran one of the engineer roadblocks a

few miles down the road from the command post.

At 0600 next morning tanks of the Panzer Lehr Division hit the engineer roadblock at Neffe, manned by Company B’s 2nd Platoon under a young lieutenant, William C. Cochran. Cochran could not tell in the darkness and fog whether the approaching tanks were German or American, so he went forward to get a better look. He was quite close to the first tank when he called back to his men, “These are Germans.” From the tank someone replied in English, “Yes, we are supermen” and fired. Cochran fired back, killing two men riding on the tank.33

Pvt. Bernard Michin, waiting at the roadblock with a bazooka, peered at the advancing tank. Never having fired the weapon before, he let the vehicle come within ten yards of him to be sure of his target. At that range the explosion seared Michin’s face and totally blinded him. He rolled into a ditch, stung with pain. A German machine gun stuttered nearby, and he tossed a hand grenade in the direction of the firing, which stopped abruptly. Still blind, he ran toward American lines where willing hands among the platoon guided him to the rear. His sight returned only after another eight hours, but his heroism had earned him the Distinguished Service Cross.34

By the evening of 19 December, infantry of the 101st Airborne Division had relieved the 158th Engineer Combat Battalion, and the battalion was back in a bivouac area well to the west. But the engineers were to be allowed only the briefest respite. Beginning at 2200 the 158th was alerted to defend a Bailey bridge at Ortheuville, about ten miles west of Bastogne. This bridge, which carried the VIII Corps’ main supply route (N-4, from Namur via Marche) over the western branch of the Ourthe River, was threatened by reconnaissance tanks of the 2nd Panzer Division. Advancing southwest along Route N26, which intersected N-4 about seven miles west of Bastogne, they were probing for a route west to bypass that city.35

The 299th Engineer Combat Battalion had prepared the Bailey bridge at Ortheuville for demolition and with detachments of the 1278th Engineer Combat Battalion had been setting up roadblocks and mining bridges in a wide arc behind Bastogne to bar the way to Germans bypassing the city to the north or south. Because the Ortheuville bridge was vital to the supply route the engineers had not yet demolished it. As the Germans began to attack toward the bridge during the early hours of 20 December, defenses consisted of not more than a platoon of the 299th Engineer Combat Battalion, reinforced by eight tank destroyers the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion had left behind on its way to Bastogne.36

Arriving in Ortheuville at daybreak on 20 December, the 2nd Platoon of the 158th’s Company B found that German machine-gun and rifle fire had driven the 299th Battalion’s platoon off the Bailey bridge and that the Germans had seized it. The 158th’s platoon separated into squads, crossed the Ourthe on a

small wooden bridge, and attacked the Germans’ right and left flanks. The engineers pushed the plunger to blow up the bridge, but nothing happened; presumably German fire had cut the wiring. Tank destroyers stopped an enemy tank column attempting to cross the bridge, and at noon the Germans withdrew.37 With the arrival of the 1st and 3rd Platoons, Company B, 158th Engineer Combat Battalion, advanced down Route N-4 to the intersection with N-26, clearing the road and setting up roadblocks. Elements of Companies A and C joined later in the afternoon, bringing forward four 105-mm. tank destroyers. By the end of the day the 158th had made Route N-4 safe for convoys of gasoline and ammunition to roll into Bastogne from depots at Marche.

At 1800, Company B, which had done most of the battalion’s fighting for the past two days, withdrew to a bivouac area, but an hour later it was alerted again. The Bailey bridge at Ortheuville was under heavy artillery fire, and at 2000 German armor overran the roadblock at the intersection of Routes N-4 and N-26, continuing up, N-4. As soon as the 2nd Platoon of Company B arrived on the scene some of the men crossed to the enemy side of the bridge and planted antitank mines across the road, but they failed to stop the Germans and had to withdraw across the wooden bridge.

In three attacks, one involving a party of four Germans dressed as civilians or U.S. soldiers, the enemy tried to seize the wooden bridge but was repulsed. Then; after a second attempt to blow the bridge failed, a fourth German attack was successful. The enemy infantry forded the river and picked off the defenders silhouetted against the glare of the burning houses beyond. At midnight German armor began clanking across the Bailey bridge. After a parting shot from one of their four tank destroyers caused a gratifying (but inconclusive) explosion, the engineers withdrew about eight miles southwest to St. Hubert, where in the early afternoon they were ordered to take over the defense of Libramont, another eight miles to the south.

The German armored column crossing the Bailey bridge at Ortheuville ran into roadblocks established by the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion, sent down from Marche. This was the battalion that had contributed its Company C to the defense of Trois Ponts. On 21 December the other two companies were guarding a barrier line along the eastern branch of the Ourthe River from Hot-ton, about six miles northeast of Marche, to La Roche, nine miles southeast of Hotton, and were manning roadblocks south of Marche on Route N-4 and southwest of Marche as far as Rochefort.38

The defense of Hotton, at the western end of an important Class 70 bridge over the Ourthe, was in the hands of a squad from Company B and half a squad from Company A. The 116th Panzer Division, attacking from the northeast in an attempt to get to the Meuse north of Bastogne, shelled Hotton at daybreak on 21 December and then struck with about five tanks and some armored infantry—the spearhead of an

armored brigade. In the ensuing fire-fight the American defenders included half a squad of Company A, the squad of Company B, ten men of the battalion’s Headquarters and Service Company, and two 40-mm. gun sections from the battalion’s attached antiaircraft battery. They were joined by several bazooka teams, a few 3rd Armored Division engineers with a 37-mm. gun, and a Sherman tank with a 76-mm. gun that the engineers discovered in an ordnance shop on the edge of the town and had commandeered along with its crew. This scratch force, under the command of Capt. Preston C. Hodges of Company B, managed to hold the town until shortly after noon, when a platoon of tanks of the 84th Infantry Division arrived from Marche and a task force of the 3rd Armored Division came in from the east.39

Stopping the German Seventh Army

At the southernmost portion of the VIII Corps front the Our flowed into the Sauer and the Sauer formed the boundary between Luxembourg and Germany. There General der Panzertruppen Erich Brandenberger’s Seventh Army, composed of two infantry corps, attacked on 16 December. This army was the “stepchild of the Ardennes offensive,” lacking the heavy support accorded the two powerful panzer armies on the north.40 Its mission was to guard the flank of the Fifth Panzer Army. Its northernmost corps (the LXXXV), with the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division, was to cross the Our north of its juncture with the Sauer and advance on a westward axis parallel to the Fifth Panzer Army. The southernmost corps, the LXXX, with the 276th and 212th Volksgrenadier Divisions, was to establish a bridgehead at the town of Echternach on the Sauer and make a limited advance to the southwest in the direction of Luxembourg City.

Guarding the line of the Our on the north was the 28th Division’s 109th Infantry. It was attacked by the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division and the Fifth Panzer Army 5th Parachute Division, which was driving a wedge between the 109th and the 110th Infantry regiments to the north. Most of the 28th Division’s meager reserves had gone to the hard-pressed 110th Infantry, in the path of the powerful Fifth Panzer Army. Among the few reserves allotted to the 109th Infantry was Company A of the 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion, which was attached to the 109th on the evening of 16 December.41

By the end of the sixteenth elements of the German parachute division on the extreme north had crossed the Our at Vianden (about thirteen miles southeast of Wiltz) on a prefabricated bridge emplaced in about an hour, broken through to the Skyline Drive, and cut off several 109th Infantry outposts. The rapidity of this advance, threatening Wiltz, caused the 28th Division commander to request some of the 109th Infantry’s reserves. A platoon of tanks with an infantry platoon aboard and a few engineers started north, but could neither stop nor penetrate the northern wing of the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division;

they joined the withdrawal westward toward Wiltz. The southern wing of the 352nd, on the other hand, encountered Americans dug in on heights in a triangle formed by the confluence of the Our and the Sauer. On the night of 17 December the Volksgrenadier Division received some bridging equipment and, with its increasing strength in heavy weapons including Tiger tanks, was able to break through the defenders’ roadblocks and take Diekirch, six miles southwest of the Our crossing, on 20 December. That night the division advanced nearly three miles farther to take Ettelbruck, a German objective for 16 December. By delaying the German division four days, the outnumbered defenders had disrupted enemy plans. The engineers who established roadblocks and manned outposts had made a considerable contribution. One platoon patrolling roads in the forward area captured twelve Germans before it was forced to withdraw.42

Just to the south, where the LXXX Corps was attacking, the 60th Armored Infantry Battalion of the 9th Armored Division, an untried unit sent to this quiet sector for combat indoctrination, held about six miles of front. When the 276th Volksgrenadier Division attacked the armored battalion, the 9th Armored Division commander sent forward reinforcements of tanks, tank destroyers, and artillery; the infantry reinforcements consisted of a company of divisional engineers. The new strength enabled the armored infantry battalion to fight as a combat command and to put up strong resistance to the 276th. Least effective of the three Seventh Army divisions committed to the battle, the 276th had no tanks, and American shelling effectively interfered with its attempts to get heavy weapons over the Sauer. The division had to pay heavily for the three or four miles it was able to advance from the Sauer—a more limited penetration than that of any other Seventh Army division.

General Brandenberger sent his best division, the 212th Volksgrenadier, across the Sauer about twelve miles southeast of Vianden into a hilly area around the town of Echternach known as “Little Switzerland.” This was the northern portion of the 35-mile-long front, bordered by the Sauer and the Moselle, and held by Maj. Gen. Raymond O. Barton’s depleted 4th Infantry Division.

Crossing the narrow, swift Sauer at several points in rubber boats, the German troops quickly overcame forward elements of the 12th Infantry, the only troops in the Echternach area. Here, as in other sectors, the preliminary German artillery barrage cut wire communications; in this sector, held by a regiment battered in Hürtgen Forest, radios were scarce and had very limited range in the broken terrain. Thus, it was around noon before General Barton, at division headquarters near Luxembourg City about twenty miles southwest of Echternach, had a clear picture of what was happening. From the meager stocks of his 70th Tank Battalion he allotted the 12th Infantry eight medium and ten light tanks, making possible the formation of tank-infantry teams to aid the hard-pressed infantry companies at the front. With one of these teams, Task Force Luckett, the 4th Engineer Combat Battalion went forward to hold high ground near Breidweiler, about five miles southwest of Echternach, but when no enemy appeared

part of the battalion returned to engineer work.43

On the afternoon of 16 December General Barton telephoned General Middleton, the VIII Corps commander, to ask for reinforcements. All Middleton could offer was the 159th Engineer Combat Battalion, which was working on roads throughout the corps area as far north as Wiltz and Clerf. Middleton told Barton that “if he could find the engineers he could use them.”44

Barton found the headquarters of the 159th in Luxembourg City. The engineers were ready for orders to move to the front, for two of their trucks on a routine run to pick up rock at Diekirch in the 28th Division area had returned with the news that the rock quarry was under German fire. On 17 December the battalion was attached to Task Force Riley from Combat Command A of the 10th Armored Division, whose objective was the village of Scheidgen, some four miles south of the Sauer on the Echternach–Luxembourg City road. The Germans had already overrun Scheidgen, bypassing roadbound U.S. tanks by going through the woods.45

On the morning of 18 December, wet and cold with heavy, low-hanging clouds, the engineer battalion drew ammunition and grenades and moved forward from Luxembourg City. Company B remained in reserve several miles to the rear. Accompanied by light tanks and tank destroyers, Companies A and C advanced toward Scheidgen, the engineers through woods south of the town and the tanks on a road from the west. They took the town without much opposition, though part of Company C received heavy small-arms fire from Hill 313, about a mile north. After a night in Scheidgen under heavy German shelling the two engineer companies secured Hill 313, which overlooked the Echternach—Luxembourg City road. They dug foxholes and waited. They could see Germans moving around at the foot of the hill, and next morning, 20 December, they received a barrage of enemy artillery, mortar, and rocket fire. Then two parties of Germans tried to come up the hill, but were repulsed. That day, Company B (minus one platoon) came up, assuming positions on high ground about 800 yards west of Hill 313, while Companies A and C took turns going into Scheidgen for hot food and a little rest. The engineers kept hearing reports that infantry was coming up to relieve them, but none arrived.

On the morning of 21 December the Germans attacked again. Some charged up Hill 313 screaming and firing automatic weapons, but the main force hit Company B on the left, drove a wedge between two platoons, killed the company commander, and occupied the company’s positions. The tactical value of Hill 313 was lost, and Scheidgen had become a shambles from heavy pounding by German artillery. Companies A and C withdrew to positions slightly southeast of Scheidgen toward Michelshof, while the remnants of Company B went to the rear.

Michelshof, a crossroads town on the road to Luxembourg City, formed part of the main line of resistance. The two engineer companies, accompanied by

two medium tanks and a tank destroyer and commanded by Capt. Arthur T. Surkamp, the battalion S-3, dug in there on 22 December. Nothing lay between them and the enemy on the north but a badly mauled company from the 12th Infantry, a patch of woods, and some open fields. During the day they came under rocket and artillery fire, but supporting artillery of the 10th Armored Division put a stop to most of it.

About 1700, as dusk was falling, enemy troops moved out of the woods in V formation and advanced across the fields toward the engineers. Captain Surkamp, alerting the artillery to “drop them in close” when signaled, ordered the engineers to hold their fire. When the leading soldiers were 150 yards away, the engineers, the tankers, and the artillery opened fire. Most of the enemy in the formation were killed or wounded.

On the morning of 23 December the engineers woke to find that the heavy clouds were gone. Soon they heard the drone of motors, and American fighter and bomber planes passed over. “This was the thing we had sweated out for days and there they were, you then knew that the jig for Herr Hitler was up.”46

The next morning, Christmas Eve, Third Army infantry relieved the men of the 159th Engineer Combat Battalion. General Patton was swinging the bulk of his troops north to pound the German southern flank, relieve Bastogne, and help end the Battle of the Ardennes.

General Middleton credited the engineers with doing a “magnificent job” as infantry in repulsing the Germans in the Ardennes. On the other hand, the VIII Corps engineer and various engineer group commanders believed that the engineer combat battalions could have done more to impede the German advance had they been employed not in the front line but in a tactically unified second line of defense in the rear. Going a step further, the official Army historian of the Battle of the Ardennes states that “the use of engineers in their capacity as trained technicians often paid greater dividends than their use as infantry” and points out that Field Marshal Walter Model issued an order on 18 December forbidding the use of the German pioneer troops as infantry.47

Yet on the defensive in the Ardennes General Middleton had to depend on the engineers. At crucial points on the front, such as Auw, divisional engineers were the only troops on the scene when the Germans struck. Because there was thought to be little danger of an attack in this quiet sector, aside from a single armored combat command General Middleton’s only reserves consisted of four engineer combat battalions—the 44th, 35th, 168th, and 150th. They fought in defense of Wiltz, Bastogne, St.-Vith, and Michelshof. Several First Army engineer combat battalions which were operating sawmills in the area—the 291st, 51st, and 158th—distinguished themselves at Malmédy, at Trois Ponts and Hotton, and at Bastogne and Ortheuville. The engineers were able to upset the German timetable, delaying the onrushing columns long enough for American reinforcements to be brought to the five main pillars of

resistance—Elsenborn ridge, the fortified “goose egg” area around St.-Vith, Bastogne, Echternach, and Marche.48

Engineers in NORDWIND

When the German Ardennes offensive fell on 12th Army Group in full fury in mid-December 1944, General Devers estimated that it was only a matter of time before German forces would strike 6th Army Group to prevent its advancing to aid the 12th Army Group to its immediate north. At the end of the month the Seventh Army held a broad salient, eighty-four miles of front that wound into the northeastern corner of Alsace from Saarbrücken to the Rhine River, with limited bridgeheads across the German border. The right flank of the Seventh Army line ran south along the Rhine to a point below Strasbourg. There, the First French Army zone began, running farther south and including a vise closed on the pocket of German divisions pinned in their positions around Colmar. A German plan, Operation NORDWIND, developed by Christmas Day, called for a massive double envelopment to catch the entire Seventh Army. Converging German attacks, one to the north out of the Colmar Pocket, would join another arm driving south near the Maginot Line town of Bitche. They would meet around Sarrebourg, twenty to thirty miles behind the Seventh Army lines. The offensive was set for 31 December 1944.

By 28 December, General Devers had ordered a phased withdrawal through three defensive lines, the first along the Maginot Line and the others marking a progressive pullout to strong positions in the Low Vosges Mountains. These orders changed repeatedly as the German thrusts failed and as French protests about the surrender of Alsatian territory reached SHAEF headquarters, but regardless of the changes, the construction of the defenses fell to the engineers.

In the last two weeks of December the three veteran engineer combat regiments, the 540th, the 40th, and the 36th, began extensive work in the VI Corps area, the most exposed northeastern corner of Alsace, which the Germans now proposed to isolate. Basing much of the fortification on the Maginot structures assigned as the first defense line, the engineers supplemented their construction with roadblocks, usually employing concealed 57-mm. antitank gun positions. Across the rear of the corps and the army area they prepared all bridges for demolition.

The 1st Battalion, 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, extracted itself from a precarious position at the start of the German drive. Assigned to VI Corps, the regiment was alerted as early as 18 December against German attacks expected over the Rhine, but no serious threats had developed by Christmas Day on the regimental front, and the engineers spent a peaceful holiday. The unit was busy through the end of 1944 extending Maginot Line positions, laying mines, and constructing bridges around Baerenthal, fifteen miles south of Bitche.

In the early morning hours of New Year’s Day 1945, the 1st Battalion of the 540th Engineer Combat Regiment assembled at Baerenthal, organizing as infantry to help meet the enemy advance

into the unit’s general area. Small units joined counterattacks or rescue attempts through the morning. Company B stood with the 117th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron in the line. Before sunup, two platoons of Company A assaulted German positions to open a path for isolated elements of the 125th Armored Engineer Battalion. Two platoons of Company C went into the main line, flanking elements of the 62nd Armored Infantry Battalion.

By midmorning the rescued 125th Armored Engineer Battalion took positions in the main line with Company C, 540th Engineer Regiment, in the face of the rapidly developing German onslaught. The hastily collected defenses of widely disparate units sagged under the weight of the German drive and finally broke at noon, sending Company C retreating upon the 1st Battalion headquarters. Just as the headquarters detachment finished burning its unit records, the Germans overran the area, and the engineers joined the general withdrawal.

By mid-January, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 540th Engineer Combat Regiment, were again in the line as infantry in 45th Division positions around Wimmenau and Wingen, twenty-five miles south of Bitche and twenty miles southeast of 1st Battalion’s former positions around Baerenthal. The regiment’s major concern other than combat was the construction of works near the towns of Haguenau and Vosges, a defensive line intended to contain other German thrusts across the Rhine.49

On VI Corps’ left the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment relieved the 179th Infantry, 45th Division, on 1 January 1945 and continued to operate as infantry until 7 February. The regiment began withdrawing from positions north of Wissembourg on the Franco-German border to the main line of resistance in the Maginot bunkers and trenches and sent aggressive patrols through inhabited points well forward of this line to prevent a solid enemy front from taking shape.50

When the German drives on the whole Seventh Army front had spent themselves by mid-January, the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment moved to relieve the 275th Infantry. The engineers occupied the right flank position of the 157th Infantry in the 45th Division line while the infantry regiment led the division’s counterattack on the enemy salient from Bitche toward the south on 14 January. In this case the 36th Engineer Combat Regiment witnessed a disaster.

As part of a double envelopment to clear the enemy from the Mouterhouse–Baerenthal valley, the 157th Infantry had advanced one battalion against the positions of the 6th SS Mountain Division in the valley and the woods around it, but the unit was pinned down and then surrounded. In eight days of heavy fighting, the regiment attacked with its remaining battalions to extricate the surrounded unit. On the fifteenth two more companies drove their way into the encirclement, only to find themselves trapped with the surrounded battalion. After five concerted assaults on the German lines, the 157th had to abandon the effort, and the regiment

Seventh Army engineers install a bridge on the Ill river

left the line on 21 January; breakout attempts from within the pocket gained the freedom of only 2 men of the original 750 engulfed in the German net. Engineer attacks to relieve the pressure on the 157th’s right were of no avail. The five companies were annihilated.51

The beginning of January found the 40th Engineer Combat Regiment spread out on VI Corps’ right flank, supporting the three infantry divisions facing a German thrust across the Rhine River in the vicinity of Gambsheim, fifteen miles north of Strasbourg. The bulk of the regiment was with the 79th Infantry Division, with one battalion supporting the 3rd Division. By early February the 40th Engineer Combat Regiment, reinforced with the 111th Engineer Combat Battalion, fell in behind the 36th Infantry Division, involved in clearing the west bank of the Rhine.52

While this clearing operation was being completed, Seventh Army was already moving to reverse the tide of Operation NORDWIND and to straighten its front in preparation for its own assault on the Siegfried Line and for crossing the Rhine. The first of these operations was the elimination of the Colmar Pocket, which had held out all winter despite determined French assaults. General Devers gave the XXI Corps, under Maj. Gen. Frank W. Millburn,

to the operational control of the First French Army for the mop-up. The 3rd, the 28th, and the 75th Infantry Divisions, the 12th Armored, and the 2nd French Armored Divisions had their own organic engineers, supplemented by numerous attached special units whose services were needed to keep open main supply routes for the troops cleaning out the remnants of German resistance around Colmar. The 1145th Engineer Combat Group, attached to XXI Corps, was the parent organization for these units. The lack of treadway bridge units in the 6th Army Group area was partially alleviated by the attachment of the 998th Treadway Bridge Company from 12th Army Group and a detachment of the 196th Engineer Dump Truck Company, converted into a bridge unit.

American engineers repeatedly went into the line as infantry during the Colmar action. The 290th Engineer Combat Battalion spent the whole period of its assignment to XXI Corps in direct contact with the enemy and aggressively pursued retreating German units in maneuvers with the 112th Infantry, 28th Infantry Division.53

The elimination of the Colmar Pocket in mid-February released the XXI Corps for action on the left flank and center of the Seventh Army line. The attached engineer units reverted to Seventh Army control for use in a series of limited objective assaults which eventually brought French and American divisions to the Siegfried Line. After crossing the Saar and the Blies Rivers, Allied forces were on German soil and in front of the city of Saarbrücken. The 6th Army Group troops did not reach the Siegfried Line until mid-March, long after the Allies to the north had overcome that obstacle in the late fall of 1944.

Seventh Army Through the Siegfried Line

The 6th Army Group engineer, General Wolfe, had the benefit of engineer intelligence gathered on the famous Siegfried Line defenses farther north in the 12th Army Group zones. By early December, Seventh Army engineers had detailed studies of the nature of the defenses and the best means of breaching them. Farther to the north, along the traditional east-west invasion corridors, the West Wall defenses ran in thicker bands, presenting layers of fortifications sometimes twelve miles deep. In the 6th Army Group sector the line was formidable but generally less deep than in the 12th Army Group’s zone. The 6th Army Group planners in fact developed designs to break through it and to jump the Rhine River, using the troops that had trained for that eventuality through the previous autumn.54

General Patch’s Seventh Army opened an assault on the line on 15 March. Central in the drive was the XV Corps which, because of the planned approach to the Rhine behind the German

defenses, had the 540th and the 40th Engineer Combat Regiments attached. Both units now had a 35-mile train of vehicles and trailers with river-crossing equipment retrieved from the forests and factories of Luneville. To keep the main arteries clear for combat elements, the long lines of laden engineer vehicles moved mainly on secondary roads, a feat for the accompanying pile-driving equipment and cranes.

Engineer troops set the pace of the attack in many places. Each regiment of the 63rd Division, whose men were the first to reach the far side of the Siegfried defenses in the XXI Corps area, had one company of the 263rd Engineer Combat Battalion attached. In a performance repeated all along the assaulting line, these engineers used primacord explosive rope and the heavier tank-launched “Snake” to clear paths through minefields. Hastily erected treadway bridges carried assaulting Shermans over the antitank trenches, while engineer satchel charges extracted dragon’s teeth to make paths for vehicles. Engineers moved with infantry teams to demolish concrete casemates, forestalling the enemy’s attempts to return and use pillboxes again. Many of the bunker entrances were simply sealed with bulldozed earth. The 263rd Engineer Combat Battalion alone used fifty tons of explosive on the German fortifications. The Seventh Army had four full divisions through the vaunted line on 23 March.

After the Ardennes

During the Allied offensive that began 3 January, following the German repulse in the Ardennes, engineer units were generally released from their infantry role and reverted to the task of helping the combat troops to move forward. The weather turned bitter cold, and snow or ice covered the roads. Working sometimes in blinding snowstorms, the engineers scattered cinders and gravel on the roads, aided in some areas by German civilian laborers. Frozen ground and deep snow made mine removal all but impossible. At one time in the XIX Corps sector, for example, thirteen bulldozers were lost to mines buried deep in snow. Since normally fordable streams were too icy for wading, the engineers had to build footbridges or use assault boats. At the little Sure River, during XII Corps’ advance in late January, the engineers turned the frozen riverbank to advantage by loading men into assault boats at the top of the bank and shoving the boats downhill like toboggans.55

A thaw during the first week of February, far more extensive than usual, presented worse problems than the cold. Roads disintegrated into deep mud. The engineers laid down crushed stone, sometimes on a bed of dry hay, and when this did not work they corduroyed the roads with logs, using prisoner of war labor. The engineers had to build highway bridges strong enough to withstand the rushing streams flooded by melting ice and snow.56

By mid-February engineer units were again being drawn from their normal duties to train for the major engineer effort on the European continent—the crossing of the Rhine.