The Corps of Engineers: The War Against Japan

Blank page

Chapter 1: Strengthening the Defense Triangle: Panama, Hawaii, and Alaska

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 found the Corps of Engineers, like the rest of the Military Establishment, in the midst of feverish defense preparations. The Corps had been assigned the task of building up defenses in Panama, Alaska, Hawaii, and other Pacific outposts; in areas ranging from the Arctic to the tropics, engineer units were engaged in a wide variety of urgent projects. Plagued by shortages of men and materials and difficult working conditions, these defense preparations were still far from finished when the nation was plunged into war. Along with these desperate efforts to build a bulwark on many fronts, the engineers were engaged in the vital mission of creating an organization and developing equipment that would enable them to carry out their many duties on the battlefronts and behind the lines in case war broke out. By the time of Pearl Harbor much progress had been made in the relatively short time since the defense buildup began. The story of the pre-Pearl Harbor defense preparations is one of an effort gradually getting under way from small beginnings and destined eventually to assume tremendous proportions.

Early War Plans and the Corps of Engineers

The United States Army had been concerned with the possibility of war with Japan for many years before Pearl Harbor. Soon after World War I, American military leaders began to frame a strategy to be followed if war broke out. The first strategic plan, War Plan ORANGE, adopted in 1924, envisaged mainly a naval struggle, with the Army to seize the Japanese mandated islands in the central Pacific, reinforce the Philippines, and then prepare for an attack on Japan itself.

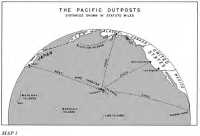

During the 1930s, in view of Japan’s growing power and the low state of American armaments, and with the independence of the Philippines scheduled for 1946, the War Department General Staff concluded that the United States should not attempt to hold initially in the western Pacific. Alaska, Hawaii, and Panama, often referred to as the “strategic triangle,” should form the main line of defense. (Map I) The last version of War Plan ORANGE, issued in 1938, embodied these views. It was assumed that after a period of strained relations, Japan would attack without

Map 1: The Pacific Outposts

notice. The Japanese would in all likelihood seize Guam and the Philippines. Enemy forces could be expected to make raids on Hawaii, Alaska, and the west coast of the United States. The Panama Canal might be wrecked by sabotage or by naval and air raids. Initially, the United States would mobilize one million men. Two armies would defend the Pacific coast, Alaska, Hawaii, and the Canal, while two more would be in reserve. Since it was assumed the Philippines would soon be lost, no plans were made for reinforcing them. Eventually, the Navy, with Army support, would fight its way across the central Pacific toward Japan. Once bases had been established in the western Pacific, the time

would be at hand to begin the attack on the Japanese home islands.1

A seemingly modest Engineer force was contemplated for a conflict of such magnitude. The Army’s strategic plan for a war with Japan, prepared in 1936, called for the mobilization of 46 engineer units on the outbreak of hostilities.

Five engineer combat regiments would support the infantry and 3 squadrons the cavalry.2 In addition, 4 heavy ponton battalions and 13 light ponton companies would serve with the combat forces. Two general service regiments, 7 separate labor battalions, 4 dump truck companies, 2 depot companies, 2 water supply battalions, a topographic battalion, 5 railway battalions, and a railway shop battalion would be needed in the rear areas. An engineer section would serve with General Headquarters. As the war progressed more engineer units would be formed.3

Had war broken out in 1938, the Corps of Engineers, like the rest of the Army, would not have been able to meet the requirements of War Plan ORANGE. Engineer officers numbered 739 and enlisted men 5,786 in an Army totaling 183,455. There were but ten engineer units—7 combat regiments, 2 of them at full strength, parts of 2 squadrons, and a topographic battalion. These units were for the most part undermanned and poorly equipped. This small force could be augmented. The 23 engineer units of the National Guard—18 combat regiments, 4 squadrons, and a general service regiment, in various stages of organization and totaling 8,768 officers and men in 1938—could be called into federal service. There were besides, 8,057 Engineer Reserve officers available for duty.4

This engineer force was wholly inadequate to deal with the manifold responsibilities which the Corps of Engineers, both a combat arm and a supply service, would have to discharge in the course of a bitter and probably prolonged struggle in the Pacific. On far-flung battlefronts of that enormous area engineer units would be called upon to remove mines, cut through barbed wire entanglements, reduce fortifications, and build and repair roads to enable the infantry to advance. Units trained in bridging would have to put troops across streams. During enemy offensives, engineers would have to try to slow the advance by placing mines, destroying roads, wrecking bridges, blowing up supplies, and at times fighting as infantry. Behind the fighting fronts the Corps could expect to have its traditional wartime logistical missions—to build fortifications, construct airfields, camps, hospitals, warehouses, roads, and ports; operate light, power, and water systems; repair and operate railroads:5 camouflage important installations; make maps for the Army; and at the same time procure the necessary supplies.6

While the Engineers would do extensive construction for the Army overseas

in time of war, their responsibility for military construction in the United States and its possessions in peacetime was limited. They were responsible only for building fortifications, which, since the United States no longer had to defend its land frontiers, meant almost exclusively seacoast defenses. In the 1920s the term seacoast defenses signified coastal batteries, access roads, and storage space for ammunition. With the growing danger of air attack in the early 1930s, the term came to include searchlight positions and antiaircraft emplacements and, by the late 1930s, aircraft warning stations. All construction for the Army in peacetime other than fortifications was charged to The Quartermaster General.

With a relatively small engineer force at his disposal, it is hardly surprising that Maj. Gen. Julian L. Schley, the Chief of Engineers, had a staff of but 21 officers in Washington in 1938. One of his principal tasks was to organize and train engineer units and develop new types of engineer equipment. This mission was the responsibility of Brig. Gen. John J. Kingman, head of the Military Division of the Office of the Chief of Engineers. The troops, for the most part, received only on-the-job training in the 1930s. At Fort Belvoir, Virginia, some seventeen miles southwest of Washington, was the Engineer School, which provided specialized instruction to officers and specially chosen enlisted men. Also at Fort Belvoir was the Engineer Board, which developed and tested equipment.

General Schley’s second major task was construction. This, however, included not merely the building of fortifications. Congress had charged the Corps with two important civil responsibilities—improvement of rivers and harbors and flood control. To perform this civil work and to build fortifications, the Corps had developed a nationwide organization of divisions with 48 districts, staffed in 1938 by 206 engineer officers and some 56,000 civilians, all under the general direction of the Chief of Engineers and directly responsible to Brig. Gen. Max C. Tyler, head of the Civil Works Division of General Schley’s office. At that time the Corps was at work on about 1,000 rivers and harbors projects and about 400 flood control projects in the United States, Puerto Rico, Alaska, and the Hawaiian Islands, for which Congress had appropriated $234,465,300 for the fiscal year 1938.7 The general belief was that the divisions and districts afforded Engineer officers valuable experience which would stand them in good stead in time of war. What is more, a construction organization was already at hand to participate in any defense effort which might be launched.

First Steps in Building up the Pacific Outposts

Rearmament Begins

The Corps of Engineers began building up the defenses of the United States against possible attack from the Pacific about eighteen months before Pearl Harbor.

The kind of construction to be done and its location depended largely on the policies of the administration in Washington, the strategic planning of the War Department, and the appropriations voted by Congress. It was to be assumed that by far the larger share of the money for a defense buildup would go to The Quartermaster General.

a period of strained relations likely to precede the outbreak of war with Japan, it could be expected that one of the first tasks assigned the Corps would be the strengthening of seacoast defenses bordering on the Pacific.

The mounting international tension in the late 1930s in Europe and in the Far East indicated that a major defense buildup was probably close at hand. Late in 1938, President Roosevelt advocated that the United States, hitherto concerned only with defending its own territories, protect all of the western hemisphere. Addressing Congress in January 1939, he stressed the need for strong armed forces and asked for $525 million for armaments, half of it to be spent by 30 June 1940. Three hundred million dollars of the total would go for airplanes to bolster the air defenses of the continental United States, Alaska, Puerto Rico, and the Canal Zone. The President wanted some $8 million to improve seacoast defenses in the Canal Zone, Hawaii, and the continental United States.8

The General Staff began to work out a strategy of hemisphere defense along the lines suggested by the President. Despite the enlarged scope of responsibilities, the War Department concentrated almost entirely on strengthening the United States and its outlying territories. The latter, especially, needed attention, and Puerto Rico and the strategic triangle figured prominently in the early planning. In the words of Brig. Gen. George V. Strong, chief of the War Plans Division of the General Staff, “Panama, Hawaii, Puerto Rico and Alaska,” were “vital links in our defensive chain.”9 Appearing before the Committee on Military Affairs of the House of Representatives on 17 January 1939 during a hearing on a request for funds, Secretary of War Harry H. Woodring and General Malin Craig, Chief of Staff, outlined their defense program. Like the President, they stressed the need for air power. Of the outlying territories, they considered the Canal Zone by far the most important. General Craig wanted $23 million for work on airfields there. He asked for $6.5 million to strengthen coastal defenses in the United States, the Canal Zone, and Hawaii and $4 million to build the first air base in Alaska. An unspecified but modest sum would be needed to build technical facilities and temporary housing for the Air Corps in Puerto Rico. No money was requested for the Philippines.10

Existing Defenses

The strength of the existing defenses of Panama, Hawaii, and Alaska varied. The Canal Zone, with possibly the strongest defenses of the three outposts, had two military airfields, France, near the Atlantic entrance, and Albrook, near the Pacific. There were 6 major Army posts, 3 on the Atlantic side, and 3 on the Pacific. Coast artillery and antiaircraft batteries, searchlight positions, and supply depots were numerous. The sole defense installation outside the Canal Zone was Rio Hato airfield in Panama, on the Pacific coast, 50 air miles southwest of the Pacific entrance to the Canal. Rio Hato had originally been a private landing strip, the property of the owner of a nearby resort. The owner gradually improved the strip, and U.S. airmen began using it more and more frequently while on training flights. In 1935 the United States leased it for a dollar a year and, in 1938, for $200 a month. By 1939 Rio Hato had become so important for defense that Air Corps commanders in the Canal Zone urged the War Department to buy it or lease it on a long-term basis. In the Hawaiian chain, almost all military installations were on the island of Oahu. Here were the two major Army airfields, Wheeler, on the central plateau, and Hickam, on the southern shore northwest of Honolulu. The island was protected by numerous seacoast batteries near Honolulu and Pearl Harbor. Alaska had no military defenses, the only Army installation in the Territory being Chilkoot Barracks, some 15 miles south of Skagway. Army and Navy planners believed that Alaska might be subjected to air attack, but thought it unlikely that an enemy would attempt a major campaign in Alaska’s frigid wastes. The Navy would be primarily responsible for keeping hostile forces away.11

The defenses of Hawaii and the Panama Canal, though elaborate, were outmoded. Most of them had been designed and built in the days before the airplane became an important weapon. For many years it had been apparent that the islands and the Canal were more vulnerable to air attack than to naval bombardment. Maj. Gen. David L. Stone, Commanding General, Panama Canal Department, expressed a widely held view when he wrote on 15 November 1939 that “the first threat against the Canal will come from either land based or carrier based aviation.”12 Despite its more remote location, Panama, like Hawaii, feared attack mainly from Japan. To the east was a protective screen of islands extending from Florida to South America. There was no such barrier in the Pacific. The only islands on which defenses could be built were the Galapagos, Cocos, and Clipperton.13

Appropriations

On 26 April 1939 Congress made its regular appropriation for the War Department

for the fiscal year 1940. By far the greater share of the money for defense construction requested by the War Department went to The Quartermaster General, who received $24,387,987 for construction in the United States and its outlying territories. The Chief of Engineers got $2,721,960 to improve seacoast defenses, of which $1,146,000 was to be spent in Panama and $268,746 in Hawaii. During the following months Congress made supplemental appropriations. In May it gave the Engineers an additional $1,059,705 to improve seacoast defenses, $828,805 of it for Panama and $230,900 for Hawaii. In July the Quartermaster Corps got $90,349,459 more for military construction in the United States and its outlying possessions, including $3,600,000 to build an airfield near Fairbanks, Alaska, the first money to be allotted to the War Department for defense in that Territory. In August Congress gave the Quartermaster Corps an additional $400,000 for the Alaskan airfield and the Engineers $1,500,000 to improve the road from the Canal Zone to Rio Hato airfield. By September 1939 the Quartermaster General had received a total of $132,466,746 for military construction, about half of it for strengthening the defense triangle. The Engineers had received $6,526,196, of which they were to spend $3,924,451 to strengthen the Canal Zone and Hawaii.14

The outbreak of the war in Europe on September had little effect on defense appropriations. Until well into 1940 Congress took no further action. On 12 February it made its last appropriation for the fiscal year 1940, giving The Quartermaster General $11,661,800 in construction funds, of which $112,800 was earmarked for Panama. Nothing was given to the Engineers. This was the period of the “phony war.” The conflict in Europe aroused little alarm; many members of Congress, well attuned to public opinion, were strongly disposed to slash the War Department’s request for funds. On 23 February, the Subcommittee of the House Committee on Appropriations began hearings on the War Department’s requests for funds for the fiscal year 1941. The War Department had asked for $29,461,748 to improve and enlarge military posts—$18,535,560 of this sum to be spent on installations in the triangle. Over $12 million was to go for a second air base in Alaska at Anchorage and for the storage of gasoline and bombs in the Territory. In the report made by the Appropriations Committee to the House on 3 April, the War Department’s requests for the triangle were drastically curtailed. In the bill sent by the House to the Senate, the $18,535,560 asked for had been cut to $4,305,675. The funds requested for Panama were only slightly curtailed, but those for Hawaii were cut approximately in half and those for Alaska eliminated completely.15

War Plans

During the months of mounting world tension, the War Department began to revise its war plans. War Plan ORANGE had presupposed a conflict involving only the United States and Japan. After Munich, the view gained ground that the United States might find itself at war not only with Japan but also with Germany and Italy. The Joint Army and Navy Board began a study of various strategies which might be followed if the United States became involved in a struggle with several countries. In April 1939, the Board’s Joint Planning Committee reported that it was of the opinion that if Japan should join the European axis in hostilities, the United States could not go on the offensive in the Pacific, but would have to withdraw its forces to the east of 180 degrees longitude. The War Department’s immediate task in the Pacific, therefore, was to strengthen Hawaii, the Canal Zone, and Alaska. In May the Joint Board, approving the report, instructed the committee to prepare five strategic plans for a number of possible war situations. These plans were given the code name RAINBOW. The committee completed the first plan—RAINBOW I—in August 1939. According to this plan, the United States would protect all of its territory and that part of the Western Hemisphere north of 10 degrees south latitude. No reinforcements would be sent to the Philippines. The outbreak of war in Europe led to further studies. The subsequent RAINBOW plans outlined, in general, more extensive commitments of the United States in the defense of its territories and the Western Hemisphere.16

Engineer Organizations

Both the Canal Zone and Hawaii had going engineer organizations which could take on new defense work. On General Stone’s staff was Col. Earl North, the department engineer, with offices at the post of Corozal, near the Canal’s Pacific entrance. Colonel North had a force of about 200 civilians, made up of supervisors from the United States and laborers from the Canal Zone and Panama. Under General Stone’s command was the 11th Engineer Combat Regiment, headed by Lt. Col. Gordon R. Young. The main job of the combat engineers was to train with the Canal Zone’s defense forces, but they also were available to Colonel North on a part-time basis to help with construction. Hawaii had two engineer organizations. At Fort Shafter, just northwest of Honolulu, was the office of the department engineer, Col. John N. Hodges, a member of the staff of Maj. Gen. Charles D. Herron, Commanding General, Hawaiian Department. Colonel Hodges also commanded the Hawaiian Division’s 3rd Engineer Combat Regiment, stationed at Schofield Barracks on the central plateau, the only Army engineer unit in the Islands. The other organization was the Honolulu Engineer District, which, like district organizations of the Corps

elsewhere, was responsible for building fortifications, improving rivers and harbors, and constructing works for flood control. In late 1939 Maj. Peter E. Bermel was district engineer, serving under the Pacific Division engineer in San Francisco, who in turn was responsible to the Chief of Engineers.

There was no engineer organization in Alaska. Responsibility for such rivers and harbors and flood control work as was done rested on the Seattle Engineer District headed by Col. Beverly C. Dunn, who was under Col. John C. H. Lee, North Pacific Division Engineer. The defense of the Territory was the responsibility of Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, commander of the Fourth Army, with headquarters in San Francisco.17

An expanding construction effort in the outlying territories would pose difficulties. There were few resources in manpower or materials in the triangle. The Hawaiian chain, about 2,400 miles southwest of San Francisco, with an area of some 6,200 square miles, had a population of 425,000, almost all of it concentrated on the five major islands. Oahu, with the capital city of Honolulu, was the center of the Territory’s economy, which was based mainly on the production of pineapples and sugar cane. There was little manufacturing. Almost all of the supplies and the great number of workmen required for an extensive construction program would have to come from the United States.

The Canal Zone, a strip of land 10 miles wide through which ran the vital waterway, was 3,350 miles from Los Angeles. Panama, which the Canal Zone bisected, had no industry to speak of, almost no construction equipment, and few skilled workmen. The only manufactured items the engineers could count upon getting locally were structural clay products, principally brick and tile. Of the three outlying territories, Alaska would offer the greatest obstacles to large-scale military construction. About one-fifth the size of the continental United States, the Territory had a scant 75,000 inhabitants. The almost complete absence of industry, public utilities, and highways, and the remote location of the areas of strategic importance, presented a dreary prospect.

Work Begins

During 1939 and the first months of 1940, the engineers began the task of improving the defenses of Panama. Colonel North’s organization casemated a few guns, built additional bombproof storage for ammunition, and put in a small number of access roads. In late 1939 the 11th Engineers began to improve Rio Hato airfield.18 On the whole, the expanded program provided for by the Congressional appropriations remained in the planning stages. Much of the money which Congress did make available for the fiscal year 1940 had to be spent for equipment. “Our dry season,” Colonel North wrote on 27 December, “is about here and we were all

set for a big push. ... Most of our new equipment is here ... but we must have a lot more money which I understand ... is in the War Department Act for 1941.”19

In January Lt. Gen. Daniel Van Voorhis replaced General Stone. Van Voorhis’ staff continued work on the program of modernizing the defenses of the Canal. In mid-February North reported that plans were completed to make all antiaircraft batteries mobile, except ten on the Atlantic side and nine on the Pacific. But up to this time, the War Department had authorized no additional construction at the batteries except the building of more gun blocks at fifteen of the fixed sites. Soon after his arrival, Van Voorhis and his staff began to devote more time to preparing plans for building defense installations in the Panamanian Republic. If the Canal were to be adequately protected, defenses would have to be built far beyond the limits of the Canal Zone.20

In Hawaii, the department engineer continued to work on plans to bombproof more coastal guns, install additional searchlights, and build aircraft warning stations. In view of the great amount of work local commanders thought necessary, it appeared that funds available in the near future would not be adequate. Merely to bombproof the more important installations, including seacoast defenses, communication centers, command posts, and storage facilities for critical supplies, would, it was estimated in June 1939, cost approximately $4.5 million. The Honolulu District, with its force of hired labor, was engaged in a modest program of strengthening seacoast defenses and improving the ports at Honolulu, Pearl Harbor, and Midway Island.21

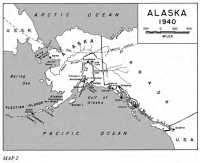

In 1939 and early 1940 the Engineers had little to do with Alaska. The Navy and the Quartermaster Corps undertook the first construction for defense in the Territory. With funds appropriated by Congress in April 1939, the Navy began work on its new air bases at Kodiak and Sitka in September and at Dutch Harbor in the following spring. Late in 1939 the Quartermaster Corps made preparations to enable work to get under way by spring on the air base at Fairbanks, to be called Ladd Field. (Map 2) In August a board of officers proposed that the War Department build several operating and emergency airfields in Alaska. The Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) was then embarking on a program of building and improving airfields in the Territory. Of those CAA planned to build, the Secretary of War was especially interested in the one on Annette Island at the southern tip of the Alaska panhandle and the one near the village of Yakutat at the northern end. With fields at these two places, planes would be able to make the 1,500-mile trip from the United States to Ladd in relative safety. Early in 1940 the Engineers became engaged in” defense work in the

Map 2: Alaska, 1940

Territory for the first time. They were directed to make surveys for the staging fields to be built by CAA or the Quartermaster Corps in the panhandle. In February, under engineer supervision, men of the Department of the Interior began to survey the site at Annette. No final decision had as yet been made with regard to Yakutat.22

A Sudden Upsurge

The spring of 1940 saw the end of the “phony war.” In April Germany seized Denmark and Norway and in May invaded the Low Countries and France. On 25 June France surrendered. There was a violent reaction in the United States, and President Roosevelt and Congress

rushed plans and preparations for building up armaments. On 13 June, Congress, in its regular appropriation for the fiscal year 1941, restored the items for the triangle that it had cut out a few months earlier. The Quartermaster received funds for modernizing and enlarging Fort Shafter and Schofield Barracks in Hawaii, improving Albrook Field and the post of Corozal in Panama, and constructing a second air base, Elmendorf, together with an Army post, Fort Richardson, near Anchorage in Alaska. The Engineers got $8,722,718 for seacoast defenses; $2,896,813 of this sum was to be spent for installations in Panama and $599,686 for those in Hawaii. Of the sum for Panama, $212,193 was to be used to improve fortifications, $328,100 to complete work on the 16 inch guns at Fort Kobbe and on minor batteries, $236,520 to build storage for ammunition, $1,120,000 to buy and install searchlights, and $1,000,000 to put in access roads.23

During the summer Congress enacted additional measures to strengthen defenses. On 19 July it passed the “Two Ocean Navy Act,” which authorized expansion of the fleet by 70 percent. In August it authorized the President to call the National Guard into federal service. On 9 September it passed the second supplemental defense appropriations act, which increased the authorized program by $5.4 billion. A week later it enacted legislation authorizing the draft. The strength of the Army was to be increased to 1,400,000 men.

The Joint Board accelerated work on the RAINBOW plans. The fall of France had caused a decided shift in emphasis from the Pacific to the Atlantic. During the late spring, Army and Navy planners had concentrated on RAINBOW 4, which presupposed possible operations in the Atlantic and South America and a defensive stand in the Pacific. President Roosevelt approved this plan on 14 August. Thereafter, the planners concentrated on RAINBOW 5, which presupposed operations in Europe and Africa, while, as under RAINBOW 4, the United States would remain on the defensive in the Pacific.24

Faced with the threat of a two-ocean conflict, War Department planners regarded the strengthening of the Canal Zone as more urgent than ever. North and his engineers expanded their construction efforts. They got started on the job of making the antiaircraft batteries mobile. A new type of project, assigned in June, was the building of the joint command post tunnel for the department headquarters at Quarry Heights on the Pacific side. For this job, North used men from his regular hired labor force trained in fortifications work. Construction was speeded up at Rio Hato. During the summer part of the 11th Engineers, about 600 men from the Air Corps, and some men loaned by the quartermaster were at work there. A dock was built to unload materials and heavy equipment, which had to be shipped by sea, since the road from the Canal Zone, constructed as part of the Pan American Highway, would not hold

up under military traffic.25 A hampering factor was the rainy season, which prevailed from May till December. “One of the major difficulties ... was the climate,” North wrote later. “During the rainy season, the clayey earth became a soft sticky gumbo and ... construction which involved earth excavation and moving was difficult and slow.”26 Construction was not North’s only interest. Because military maps of the Canal Zone, made back in 1915, were almost obsolete, North wanted to remap certain areas by using aerial photography. In September, much-needed equipment began to arrive to make possible a start on the aero-cartographic program.

By the summer of 1940 General Van Voorhis and his staff were greatly concerned with making defenses more mobile. But mobility of itself would be of little value unless numerous defense installations were built in the Republic of Panama. Some of the 153 searchlights and most of the aircraft warning stations which Van Voorhis wanted would have to be located there. New defense installations in the Republic would necessitate building many additional roads. A big stumbling block was securing land from Panama. By a treaty negotiated in 1936 and ratified in 1939, any tracts of land which the United States authorities wanted in the Republic were to be secured by negotiations with the Panamanian Government, and procedures for leasing had not yet been worked out. The War Department and the State Department were making little progress in persuading the Panamanian Government to lease land for 999 years, as American commanders in the Canal Zone wished. How long it would be before Panama would consent to lease land was a question impossible to answer in the summer of 1940.27

In only slightly less emphatic fashion, the engineers in Hawaii felt the impact of the growing defense effort. Between April 1939 and July 1940 Congress had appropriated $1,197,332 for improving seacoast defenses in the islands. General Herron, convinced that the program for peacetime defense construction as outlined in mid-1939 would have to be expanded, continued to insist on more funds for fortifications, and in this he was wholeheartedly supported by Col. Albert K. B. Lyman, who became department engineer in July 1940. Herron wanted more airfields and seacoast batteries, more antiaircraft guns and searchlights. He was particularly anxious to bombproof vital installations on Oahu. He insisted on more underground storage for ammunition, which he planned to distribute on Oahu as a protection against bombing and to relieve congestion at Aliamanu Crater, the main storage area, about one mile east of Pearl Harbor. On 5 July he appointed a board of officers to consider all aspects of defense against aerial and naval bombardment. With construction on new military installations about to begin, the need for more roads and trails was pressing. They would have to be put in to

provide access to the new observation posts, antiaircraft batteries, seacoast batteries, and searchlight positions. Additional roads would be needed for military operations. The conflict in Europe had demonstrated that, in the new mobile type of warfare, troops, in order to move forward or withdraw rapidly, required a variety of roads and trails. Lyman doubted that many additional roads could be built if war were imminent or under way; if built at all, they would have to be put in in peacetime. To bolster the defenses of the Islands, General Herron and Colonel Lyman wanted more engineer troops. On 23 August, Herron “strongly recommended” to the War Department that a regiment of aviation engineers, less one battalion—a new type of engineer unit trained to build airfields—be sent. The reply from Washington was that there were so few engineer troops none could be spared.28

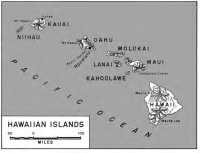

Especially critical in Hawaii was the need for aircraft warning stations. Early in 1940, a local board of officers had made a study of the need for such stations. The members spent ten weeks surveying the five principal islands from the air and on the ground. It was apparent that the configuration of the archipelago limited construction to a line extending generally northwest and southeast from Oahu. It would be difficult to detect planes approaching from the

north, northeast, south, or southwest until they were quite close. The members of the board emphasized the need of providing protection to the westward as this was the direction from which an attack would most likely come. Their report, made in April 1940, called for three fixed and six mobile stations on the four largest islands and an information center at Fort Shafter. The fixed stations were to be built at the most crucial points. The westernmost one would be at Kokee on Kauai. (Map 3) On Oahu, the station would be put on steep and craggy 4,000-foot high Mount Kaala, west of Schofield Barracks, while the station on Maui would be atop 10,000-foot high Haleakala. On 27 June the War Department authorized construction, and in July Lyman conferred with Lt. Col. Theodore Wyman, Jr., the newly appointed district engineer, to acquaint him with the project. Building these stations would not be easy, for the sites were remote and inaccessible. The station on Mount Kaala would require a cableway to the summit to bring up supplies. To get construction started in the summer, Lyman planned to have the 3rd Engineers begin surveying for an access road to the lower terminal of the cableway to be built to the top of Mount Kaala.29

The Engineers in the summer of 1940 somewhat unexpectedly became in part responsible for defense construction in Alaska. On 10 May the War Plans Division had informed General George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff since July 1939,

Map 3: Hawaiian Islands

that strengthening the Anchorage–Seward area and the Navy bases under construction at Kodiak and Dutch Harbor was imperative.30 It recommended that an infantry battalion and a battery of field artillery be sent to the Territory. On 17 June, the War Department set up the Alaska Defense Force, with headquarters at Anchorage, under Col. Simon B. Buckner, Jr. Buckner was responsible to DeWitt. The first echelon of the garrison, numbering 751, reached Anchorage on 27 June and included the 32nd Engineer Combat Company (Separate) of 91 officers and men, the first engineer unit to reach the Territory. The 32nd engineers went to Elmendorf Field, where they began to build facilities for their camp and engage in combat training. In August the Joint Army and Navy Board, after a month-long study of Alaska’s strategic position, advocated a still greater defense build-up so that the Territory could be held even without naval protection. The board advised stronger defenses for the naval

stations, and also recommended that the contractors being employed to build the naval bases be used to build posts for Army garrisons. The Secretaries of War and Navy approved these recommendations, which became the basis of Army and Navy policies with regard to Alaskan defenses.31

Since Alaska in time of war would be especially liable to air attack, much thought was given to the construction of aircraft warning stations. Late in May DeWitt was directed to make a study of the network of stations which the War Plans Division proposed for the Territory. Included was an information center at Anchorage and four detector stations, three of them to be near the naval bases and one near Anchorage. If possible, the stations were to be mobile. Should General DeWitt judge that more stations were needed, he was to decide where they were to be located. Colonel Lee, as North Pacific Division Engineer, would be responsible for making surveys, preparing estimates, and constructing the buildings for housing the equipment. After studies had been made by a board of officers, DeWitt proposed construction of an information center at Anchorage, one mobile station at Fairbanks, and 7 fixed stations along the coast from Sitka to Norton Sound, just south of Bering Strait. He believed the number of detector stations should eventually be increased to 13. In August General Marshall approved plans for the information center and for 8 of the detector stations.

He was in favor of the locations for the installations at Kodiak, Sitka, Fairbanks, and Anchorage, but wanted the 5 other sites resurveyed. He suggested that efforts be made to reduce costs, especially for access roads.32

General DeWitt was anxious to improve communications in the almost uninhabited territory. Of vital importance was the government-owned Alaskan Railroad running northward from the port of Seward through Anchorage and on to Fairbanks. From the standpoint of defense, the weakest point in the line was the 100-mile section from Seward to Anchorage, where the railway passed through deep gorges and over high trestles, thus providing attractive targets for saboteurs and hostile aircraft. The railroad’s management was considering building a 14-mile cutoff at a point sixty-six miles north of Seward eastward to Passage Canal, an inlet on Prince William Sound. DeWitt suggested to the War Department that it exert every influence to have this project carried out, preferably by the Engineers. On 13 July the War Department authorized Colonel Lee to investigate and consider three choices: improving the line from Seward to Anchorage, constructing the cutoff, and developing Anchorage itself as a port for oceangoing vessels. Two engineers sent out by Colonel Dunn to explore the possibilities recommended that the Alaskan Railroad be authorized to build the cutoff. While this shortened route would require some three and one-half miles

of tunneling, it would be easier to defend against aerial attack than the existing line south to Seward and would considerably shorten the haul to Anchorage and Fairbanks. Moreover, Passage Canal had an advantage over Anchorage in that it was ice free the year round. On 31 July DeWitt repeated his earlier recommendation that the job be given to the Corps of Engineers.33

More important than any of these projects was the building of airfields. Since the Quartermaster Corps had started work at Ladd and Elmendorf, it was highly important to get work under way on the two staging fields in the Alaska panhandle. In mid-1940 the Civil Aeronautics Authority was planning to build both fields, but DeWitt thought CAA would take too long. Convinced that Annette, especially, should be started at once, he recommended on 9 July—despite the fact that airfield construction was properly the province of the Quartermaster—that the Engineers build the field. Late that month the War Department assigned the job to Maj. George J. Nold, commander of the 28th Engineer Aviation Regiment, in order to give the unit training in building airfields. The Seattle District would supervise work on the field, the site of which was on the reservation of the Metlakatla Indians. On 6 August the Department of the Interior granted temporary use of the land needed, with the understanding that consideration would be given to the Indians with regard to employment and the purchase of supplies. The field was to be extensive, with two asphalt runways 5,000 feet long, concrete aprons and taxiways, a hangar, a dock, a seaplane ramp, roads, housing, and storage for supplies, gasoline, and oil. On 20 August Major Nold, with two battalions of the 28th Engineers, two companies of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) from Oregon and California, and thirty-five civilian technicians sailed from Seattle. They arrived at Annette three days later and immediately went to work on a camp and a dock.34

Last Months of 1940

As the international situation continued to deteriorate, Congress voted additional funds for armaments. On 8 October, it passed the Third Supplemental Defense Appropriation Act for the fiscal year 1941, in the amount of $1.7 billion, making a total of over $12 billion appropriated for defense since the previous June. It now appeared more likely that the United States would be involved in a war with Germany, Italy, and Japan. Insofar as the Pacific was concerned, the United States initially would continue to maintain a defensive position and concentrate on strengthening Alaska, Hawaii, and Panama. The RAINBOW 5 plan, which presupposed such a turn of events, had by fall been worked out in broad outlines.35

By this time, there was a declining emphasis in Washington on civil works. The President, while requesting greater sums for military construction, was asking that rivers and harbors work be held to a minimum. Largely for this reason, the Chief of Engineers made a bid for a substantial role in the building of defense projects.36 The commanders in the triangle were very much in favor of transferring military construction from the Quartermaster Corps to the Engineers. The centralized system whereby local constructing quartermasters were under the direct control of The Quartermaster General in Washington had caused a great deal of dissatisfaction. In the Canal Zone, for example, the department engineer, a member of General Van Voorhis’ staff, handled fortifications work, but all other military construction was the responsibility of the constructing quartermaster, who reported directly to The Quartermaster General’s office. In Hawaii, the Honolulu District Engineer had broad authority and could, in line with General Herron’s suggestions, make decisions on the spot, while the local constructing quartermaster had to refer most design and contractual matters to his superiors in Washington. General DeWitt was of the opinion that The Quartermaster Corps, although it did excellent work, was inclined to carry on construction at a leisurely peacetime pace, while the Engineers, prepared to build in war, put great emphasis on speed. All three department commanders had great confidence in the Corps of Engineers’ technical ability.37

A change in construction responsibilities was soon forthcoming, for on 9 September the President signed a bill which authorized the Secretary of War at his discretion to transfer to the Engineers any part of military construction then assigned to the Quartermaster Corps. This authority was to expire on 30 June 1942. For the time being, the Secretary did not invoke this power.38

In view of the increasingly serious international situation, defense work in the outlying territories seemed exasperatingly slow to the local commanders. There were many reasons for the delays. It took time for the enactments of Congress to be translated into construction. The War Department had to put detailed plans for building into final form. Workmen had to be hired and organized into effective construction forces. In recruiting workers, the Engineers were confronted with increasing competition from the Quartermaster Corps and the Navy. Materials had to be ordered and shipped as prescribed by government regulations. In Panama and Alaska, climatic conditions were a hampering factor. In many cases, work was held up because of strong differences of opinion over sites for installations. To many in the War Department, the possibility of an attack on the triangle seemed remote, with the need for fast action not apparent.

In the Canal Zone, the rains continued to be a major hindrance. Insofar as

possible, the engineers worked on searchlight emplacements, antiaircraft batteries, storage for ammunition, and access roads. They made some progress on Rio Hato. When the 9th Bombardment Group arrived from the United States in November, the 11th Engineers put up a 2,000-man camp for them. The Public Roads Administration, with funds supplied by the Engineers, began to improve the highway from the Canal Zone to the airfield. In November Colonel North set up a Soils Laboratory whose main job was to test the soils of the Canal Zone’s generally swampy terrain and recommend methods of compaction and stabilization for roads and airfields.39

Van Voorhis was especially anxious to get work started on the aircraft warning stations, and in October the War Department approved his plans for nine. Besides the two at the entrances to the Canal, where experimental facilities were already in place, Van Voorhis wanted seven in the Panamanian Republic. He prepared plans for two coast artillery and forty-six searchlight positions, some of the latter to be set up in Panama. In addition, he wanted the quartermaster to build a number of auxiliary airdromes and landing fields in the Republic. On

October he gave a list of the desired sites to the Panamanian Government. Little progress was being made on the leasing question. Dr. Arnulfo Arias, who took office as President of Panama on 2 October 1940, raised many objections to the views of the Government of

the United States about acquiring land in Panama. Instead of a 999-year lease—or even a 99-year lease as some suggested—he wished to limit U.S. tenure to the duration of the emergency. The War Department wanted jurisdiction over acquired real estate; President Arias insisted that Panama should retain full sovereignty.40

Early in December, Arias proposed that a joint U.S.-Panamanian commission be appointed to investigate the sites. A commission of five—three Panamanians and two Americans, one of them Colonel North—was established. After the commission’s first meeting, North informed Van Voorhis that it would take at least four months to inspect the sites and locate the owners. On 30 December Van Voorhis forwarded a list of the most urgently needed tracts to the Panamanian Government, suggesting that, pending final agreement, the United States should be permitted to occupy the lands. By the end of the year, no appreciable progress had been made toward a settlement of the land acquisition problem.41

In Alaska the engineers continued to be mainly concerned with the airfields in the panhandle. The aviation engineers at Annette were gaining experience on their first job. Work went ahead on the camp and dock and, late in the fall, the men began clearing the runway sites. Such problems as Major Nold had were mainly with people. A few weeks after

work started, the Council of the Metlakatla Indians called upon Governor Ernest Gruening of Alaska to inform him that their tribesmen were not being given jobs or an opportunity to sell supplies and that Nold had exceeded his authority by getting water for his camp from a lake outside the area set aside for the airfield.42 Agreeing that the Indians were partly justified, Nold was prepared to meet some of their demands. He hired some fifty Indians as laborers, and placed them in their own camp, situated at some distance from the soldiers’ bivouac to lessen chances of friction. “The scheme,” Nold wrote, “worked pretty well and satisfied the Indians.”43 The lake was the only adequate source of water and, in accordance with Nold’s recommendation, the amount of land under lease was extended to include the lake.

There were difficulties not only with the Indians but also with the CCC. Under that organization’s regulations, the workday included the time spent in travel between camp and job. Because the soldiers resented seeing the civilians arrive at work later and leave earlier, Nold set out to have the CCC regulations changed, but without success, at least not then. There were bitter complaints from both the CCC men and the civilian technicians about the inadequate rations for the cold, damp climate. In December more adequate supplies of food began to arrive. By the end of the year the dock had been finished and the camp was nearing completion. Clearing for the runways was continuing.44

To get work started at Yakutat, Nold sent part of his slender force to that site. On 23 October Capt. Benjamin B. Talley with Company B of the 28th Engineers and a few civilians arrived from Annette. No CCC labor was desired and none was sent. As this was the off-season for fish canning, a local company leased its buildings, wharf, and narrow-gauge railroad, and some of the troops were housed in the canneries. By the end of the year, clearing for the runways was about to begin. By using engineer troops, DeWitt had gotten a head start on the airfields in the Alaska panhandle.45

Other Alaskan projects remained in the planning stages. In late October, G-4 directed the Chief of Engineers to make preparations to start work in the spring on the cutoff for the Alaska Railroad. General Schley assigned the job to Colonel Dunn, who planned to have hired labor and contractors’ organizations do the clearing, grading, and tunneling and employees of the Alaskan Railroad lay the track. On 9 December the War Plans Division ordered construction of aircraft warning stations at Kodiak, Sitka, and Fairbanks and an information center at Anchorage. DeWitt now recommended that one or more stations be built north of Cape Prince of Wales, which would extend the line of protection almost to the Arctic Circle,

and the War Plans Division took the suggestion under study. Preparations were being made to photomap many of the little-known areas of the Territory now vitally important for defense. DeWitt planned to send a photo-reconnaissance flight and Company D of the 29th Engineer Topographic Battalion to Alaska in the spring.46 There was much discussion over how many defenses Alaska needed and where they should be located. “Generally speaking,” Talley subsequently recalled, “through 1940 an atmosphere of peacetime life prevailed, only those who remembered 1914-1917 furnished the spark of urgency.47

In Hawaii, some work was started in late 1940. Construction began on a few roads and trails, since Congress had allotted $70,200 for such work in the Islands in the third supplemental appropriation, made in September. But this was only a small beginning in bettering communications. In Lyman’s opinion, improving the rail net was just as important as building new roads. Urgently needed was a connecting link between Wahiawa on the Central Plateau and the island’s north shore to keep supplies moving to the coastal defenses. Also of great benefit would be double-tracking part of the line from Honolulu to Schofield Barracks and providing bypasses where the railroad crossed over on high bridges. But the chances were slim that money would be forthcoming for such projects. In September the 3rd Engineers began work on the access road for the aircraft warning station on Mount Kaala. There were indications that building this station and the others as well might take considerable time. The site atop Haleakala was in Hawaii National Park. Park officials agreed to give the War Department temporary use of the land, but they were opposed to having structures erected which would “materially alter the natural appearance of the reservation.” They insisted on first seeing “the preliminary building plans showing the architecture and general appearance” of the structures. The Honolulu District was finding it difficult to recruit workmen because the Navy and the Quartermaster Corps had already absorbed a large part of the labor force in the Islands. By late 1940, various military units, such as the Hawaiian Separate Coast Artillery Brigade and the Hawaiian Division, were forced to use their own men to build and maintain the roads and trails they needed.48

Wyman had planned to do the additional defense work with hired labor, but by fall it was doubtful if enough workers could be found. Using hired labor was a method best suited for small jobs, as a rule, and not practical for larger projects,

especially if speed was a primary consideration, because of the time and effort required to recruit, organize, and administer a large number of workmen. There were alternative ways of getting the work done. Wyman could employ construction firms under lump-sum contracts. This would mean advertising the work, receiving bids from contractors, and giving the contract to the lowest responsible bidder. Once an agreement was signed, it would be up to the contractor to finish the job within the specified time. Another method—new to the Engineers—was to give a job to a construction firm under a cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contract. This type of contract had been designed for emergency conditions, and was to be used especially when there was little or no time for preparing plans and specifications. Congress had first authorized its use in August 1939 for construction in Panama and Alaska. In July 1940 Congress approved its use without restrictions as to time or place. Under the new arrangement, the War Department selected a firm it considered qualified and negotiated an agreement. Advertising, receiving bids, and awarding the job to the lowest responsible bidder—standard procedure under the lump-sum arrangement—were eliminated. To qualify for the new type of contract a firm had to have a good reputation and the financial resources to do the work. Every cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contract had to be approved by the Under Secretary of War. If it amounted to more than $500,000, it had to be approved, in addition, by the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense. The contractor furnished his organization and his know-how and supplied materials and equipment. The government was expected to provide him, if necessary, with additional equipment, which it would rent from suppliers of such machinery. Under the terms of the agreement the government reimbursed the contractor for nearly all expenditures and paid him a fee, the amount of which was limited by law. The haste with which such contracts had to be let meant that cost estimates were often not much more than guesses of the most general kind. Cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contracts were frequently used by big construction firms. The government had entered into such contracts in World War I, but had not used them in peacetime. In 1940 few Army officers outside the Quartermaster Corps were conversant with them, or with the difficulties which might ensue from their use.49

In October 1940 Colonel Wyman discussed ways and means of accomplishing construction with Col. Warren T. Hannum, the South Pacific Division Engineer, at that time on an inspection trip to the Islands. Like engineer officers in general, Hannum preferred having work done by purchase and hire and was opposed to using cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contracts. But in view of the fact that the Navy was using this type of agreement extensively in the Islands and since there was little time to prepare plans and specifications, negotiating a cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contract appeared to be the best solution. In a letter to Hannum on 4 November, the Office of the Chief of

Engineers approved using the new type of contract. Looking about for reliable contractors, Wyman could find none in Hawaii not already heavily engaged in defense work. Hannum suggested to Wyman that he come to the mainland to look for suitable firms. Interviewing contractors in Los Angeles, Wyman was able to line up three well-known firms, the Rohl-Connolly Company, the W. E. Callahan Construction Company, and Gunther & Shirley Company. Rohl-Connolly had completed several large projects for the Corps of Engineers and other agencies of the federal government, among them the Los Angeles–Long Beach breakwater and Headgate Dam at Parker, Arizona.

On 20 December 1940 Wyman, with the approval of the Chief of Engineers, the Under Secretary of War, and the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense, signed a cost-plus-a-fixed-fee contract in Washington, D.C., with the three firms, who formed a joint venture known as the Hawaiian Constructors. The contract called for building fortifications, aircraft warning stations, and storage for ammunition; laying additional railway track; and making additions to the radio station at Fort Shafter. The work was to cost $1,097,673 and the fixed fee was $52,220. The Hawaiian Constructors would receive all plans and specifications from the district as they became ready and would be responsible for detailed construction planning to meet the approval of the engineer in charge of the field area in which the project was located. They would be responsible for transporting materials and equipment from the engineer supply yards in Honolulu to the job sites, for organizing and directing the work crews, and for administering their organization. One of their first tasks would be to recruit workers in the United States to build up a construction organization in the islands.50

After Congress had empowered the Secretary of War to transfer any part of construction for the Army from the Quartermaster Corps to the Corps of Engineers, discussions began in the War Department about what changes, if any, should be made in the construction setup. On 19 November, a partial transfer was made. All construction for the Air Corps was transferred to the Engineers, except in the Canal Zone, where many contracts included work for both Air Corps and ground forces and a division of responsibility would have been impractical. In the United States, the first fields were transferred in December, while in the triangle, the first ones were scheduled for transfer early in 1941. Military commanders in Hawaii and Alaska believed the transfer did not go far enough. On 16 December, General DeWitt wrote to Maj. Gen. Richard C. Moore, Deputy Chief of Staff, that “the two parts of the Anchorage construction ... are so closely tied together that an efficient and expeditious job cannot be done, if both the Quartermaster Corps and the Corps of Engineers are involved.” DeWitt wanted the work given to the Engineers, and the General Staff

took his suggestions under study. Herron wanted all military construction in the Islands transferred to the Engineers, radioing the War Department on 6 December 1940 that most of the work was for the Air Corps. In Herron’s opinion, two agencies engaged in the same type of work would mean duplication of organization and competition for workmen and materials. He wanted the constructing quartermaster’s entire organization, plant, and equipment transferred. The General Staff did not agree. On 31 December, General Herron was informed that the transfer of all construction in Hawaii was “not favorably considered.”51 In any case, with work for the Air Corps added to their responsibilities in part of the triangle, the Engineers could look forward to expanded activities in 1941.